#and reduces her character to the ‘magical negro’ stereotype

Text

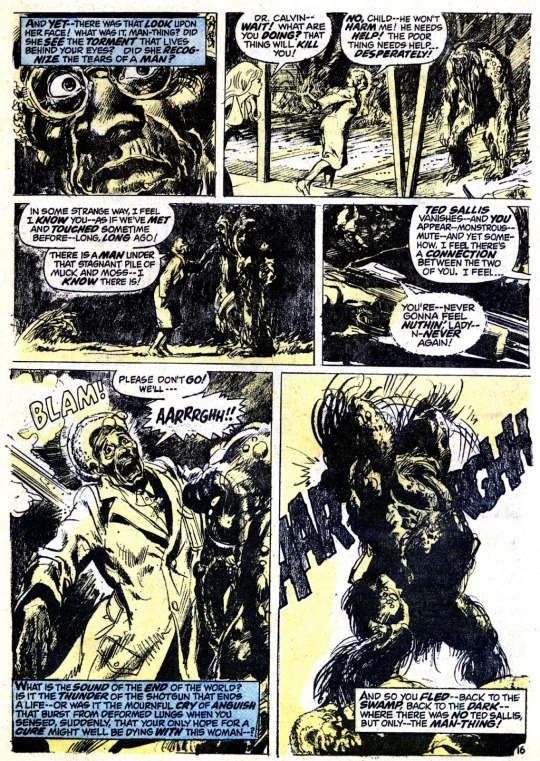

“Terror Stalks the Everglades!” Astonishing Tales (Vol. 1/1970), #12.

Writers: Roy Thomas and Len Wein; Pencilers: John Buscema, Neal Adams, and John Romita; Inker: Dan Adkins; Letterers: Jon Costa and Sam Rosen

#Marvel#Marvel comics#Marvel 616#Astonishing Tales#Man-Thing#Ted Sallis#gosh there are so many ways you could go about dissecting this#the cynical interpretation: Wilma Calvin’s seemingly preternatural sense that the Man-Thing is indeed Ted Sallis is derivative#and reduces her character to the ‘magical negro’ stereotype#a reduction not helped by her being removed from the story via racist gunshot and the commentary that some could interpret#as framing as only useful for the possible cure she could provide Ted#I could see how those arguments could be made…but because I am doomed to expect the best from comics#I prefer a slightly more optimistic perspective#that the fact that Wilma is the only one who looks beyond the ‘stagnant pile of muck and moss’ to see the man beneath#makes her the most human character of all#and isn’t there an argument to be made that who would know better about being more than one’s phenotype#than an African-American woman who has defied the belittling expectations of others to become a respected scientist?#Her being shot can represent more than just cheaply removing a black woman from the narrative#but instead represent a genuine loss of human connection#anyway yeah that’s all just imo though so anyone else’s can differ and still maintain complete validity alshskj

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stand (1990), Stephen King

First Anchor Mass Market Edition, June 2011

BIPOC, Disabled, LGBTQ+

Summary: A deadly respiratory virus escapes an American military base, decimating the population with a fatality rate that leaves behind only 1% of the human race. Of those very few, survivors, the forces of good and evil align to determine the fate of what will remain in a horror epic by prolific author Stephen King. Find my full literary review on Goodreads here.

Cripples, Bisexuals, and Negroid Things–An Exploration of Dizzying Stereotypes in Stephen King’s The Stand

Over the course of some 1,500 pages, the uncut rereleased version of Stephen King’s horror epic The Stand is a testament to his abilities as a writer so early in his career. In the year 1978, the time of the original release, King had penned Carrie, Salem’s Lot, and The Shining: three successful books, yet still the author had not been at it for long. The Stand would be a different monster entirely.

He wanted something of Tolkeinien proportions, a horror with a weaving narrative the size of a Frank Herbert novel. Inspired by both musings of mythology and memories of war, Tolkien penned Lord of the Rings over the years, whereas The Stand seemed to come together in a short period of time. In that, there is something magnificent to say about the fact that King managed to craft a vision so wholly unique: a thrilling epic combining scares, morbid humor, nihilistic musings, and a robust cast of characters on a quest to defeat evil. The result is a career-defining experience, a niche product that can wholly be associated with King and no other.

At the end of the world, the survivors must undertake one long, final journey to ensure humanity can survive. One side gravitates towards the side of “Good”, driven together by dreams of the elderly Mother Abigail, a black Nebraska-dwelling matriarch and God-fearing Baptist who will lead them on the path to righteousness. In congregating around her, they will establish a new world, a new peace, and a new society rooted in the democracy of old.

On the other side, another dream. This one, more sinister. Driven to the side of “Evil”, are those in service of a being who goes by the name of Randall Flagg. He wears a human face, though is supernatural in origin, a shape-shifting demonic entity of sorts, whose powers aren’t fully known to even himself. Charming and menacing, his own chaotic essence seeks to destroy, and those who gravitate toward him do so out of cruelty, fear, and hopelessness.

In the heart of this journey, King’s greatest strengths and flaws alike as a writer are prominent. For being so early in his career, he weaves together a tale rooted in our greatest fears: death, loss, anarchy, and evil against a backdrop that teeters between the familiar, and occasionally the supernatural. But the limitations that prove his greatest downfalls are his prejudices as a man confined to the white regions of Maine, suffering the grief-addled thralls of drug addiction and allowing unvarnished stereotypes to swath his characters–stereotypes far out of fashion for the time they were written.

It is as much the characters of The Stand who define its great journey and make it such a prolific work of art as the writing itself. Nestled within are all beings who belong to the BIPOC, LGBTQIA, and disabled communities, whose representation ranges from abhorrent to admirable, and stand as an example for writers and readers of representation in the past, and what we can look forward to in the future.

Nick, Tom, & Trashy: The Disabled Trio

While much attention is often given to racial representation within the scope of The Stand, just as prominent are disabled characters, who make up an astounding portion of its cast. Much like the Magical Negro trope to be discussed later, the Magical Cripple stereotype abounds, pigeonholing several characters into contentious roles where they are reduced to plot points meant to serve others, often at the expense of their own humility.

The three characters we will examine first under the scope of disabled representation are Nick Andros, Tom Cullen, and The Trashcan Man, each of whose representation varies from positive, to negative, to a wavering mixture of complexity. As is the case in most adaptations, all of these characters are portrayed onscreen by able-bodied actors, though it is noting The Trashcan Man suffers an invisible disability to be discussed later.

Nick Andros

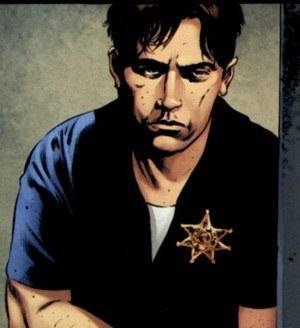

Nick Andros portrayed in the comic version titled The Stand: Captain Trips Issue #2 (link in citations).

Introduced as a down-on-his-luck drifter, Nick is deaf and nonverbal (preferred references for the condition previously known as deaf-mute here), often hitchhiking his way from place to place, a survivalist at nineteen who has had a more difficult life than most.

Unable to speak or hear since childhood, Nick has become a highly adept written communicator and observer. While he cannot use sign language, like many deaf people he has a keen understanding of body language and is attuned to the emotional intellect of others.

Like the other central characters of the novel, Nick discovers he is immune to the plague which wipes out most of the human race, and upon experiencing a series of dreams of an elderly black woman urging him to meet her in Nebraska, he sets out to join what will become the Colorado settlement. The attributes mentioned above lead to him becoming a de facto leader of sorts, his ability to see the truth in people earning the respect of the people. There’s also the unspoken wisdom that comes with a lifetime of trauma and hardship that helps him make difficult decisions, often seeing past the blind faith espoused by other members of the settlement, instead disagreeing at points with Mother Abigail or agreeing outside of his comfort zone in ways others would not.

Nick is not a perfect human being. He is nineteen years old–albeit a far different nineteen-year-old than many of us know today. In a book where it is considered normal for a twenty-one-year-old to be a parent, we look back and remember that in the Western world, we are but a decade or two removed from a radically different society: having multiple children, having them earlier, working the same job longer, staying closer to our birth home and parents, etc.

Still, Nick makes youthful mistakes. At times, he exhibits the earnestness of a teenage boy only wanting to prove himself. His background details provide a look at what has led him to these moments, scribbling down each and every word he needs to say on a writing pad, and it makes for the realization that communicating with him is a fraught and vulnerable thing, subject to something as simple as a pen running out of ink or the lights going out.

He doesn’t possess any superpowers in lieu of vocal speech or auditory hearing, nor is his emotional intelligence out of the realm of impossibility. In short, Nick is a fantastic representation of what a disabled character can be: he meets trouble and he either succumbs to it, or overcomes it. Sometimes he fails. Sometimes he succeeds. He is disabled and adapts, not in some absurd Marvel-like way but to the best of his ability. He is a human being who has downfalls and exists to serve his own aims and goals–even if they don’t turn out as he hoped.

Tom Cullen

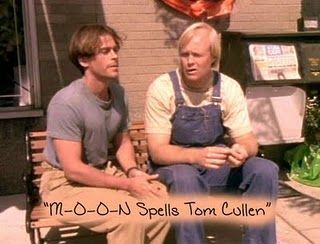

Robe Lowe (L) and Bill Fagerbakke (R) sitting on a bench as Nick Andros and Tom Cullen in the 1994 adaption of The Stand (linked below).

Naturally, what goes up, must come down. If Nick is a fantastic representation of a character with a disability, then it makes sense that his companion would be Tom, whose depiction is nothing short of reprehensible. As though he were attempting to mash together Samwise Gamgee and Lenny from Of Mice and Men, King offers a behemoth of a mess with Tom, a man with an Intellectual Disability.

Like all the stereotypical portrayals of this archetype, Tom is a big lad, with broad shoulders and blonde hair, capable of carrying a grown man. He has the easy-going personality of a man-child, the inability to read (ironic, as he and Nick find each other and he cannot read Nick’s writing), and a distinct hatred of any and all medications.

Tom fulfills the Magical Cripple narrative to its textbook definition, serving as a tool for King to advance the storylines of other characters while Cullen himself experiences little growth or reward as a character. Perhaps the most frustrating is that throughout the novel, Tom is consistently referred to by the use of the r-word, which is now considered a pejorative term. There has been no evidence found in my search to indicate this was not common use at the time of King’s writing, however, the excessive labeling of Tom as such may be either an attempt to prove a point as King does by use of the n-word or simply his understanding of individuals with IDs at the time.

Typically, Tom holds no other real aims other than playing with toys and serving his friends. Minimal insight is given into his background, or the grief he holds within him for the loss of his family and friends during the pandemic. He is presumed a large, unfeeling man, his version of “Hodor” instead “M-O-O-N spells Tom Cullen”.

Ultimately, he is chosen as one of three other individuals from the colony who will be sent to infiltrate Randall Flagg’s Las Vegas territory and gather intel, due to the likelihood that “no one will suspect the ‘special’ guy”. But folks, it’s alright. Because in case you were wondering how he’ll get away with it, well, there’s an ace up their sleeve…Tom will be hypnotized! Due to his condition, it’s determined he is highly susceptible to the practice and by having his brain hacked and a few choice lines of code implemented, he will execute the mission of the Colorado dwellers and return in time to play with his beloved toy cars.

I’m done.

Tom is not good representation. Not good representation at all.

Trashcan Man [**TW: This section contains mention of sexual violence**]

Ezra Miller as Trashcan Man in the 2020 adaption of The Stand

Last and strangest of all is Trashcan Man, AKA Trash, AKA Trashy, a character of the pure potentially drug-fueled imaginations of King’s brain. In a book containing shapeshifting demonic entities and teenage boys having anal sex rampages with grown women (she’s preserving her virginity for Mr. Flagg, so only the backdoor is serviceable) nothing should surprise us, right?

But then, Trashy abounds.

A pyromaniac schizophrenic, Trash earns his name as a child due to his proclivity for setting people's trashcans on fire, eventually earning himself time in a juvenile detention facility. Each saga in Trash’s life essentially reads as: trauma, trauma, and more trauma, likely incorporating C-PTSD and BPD into his array of mental health disabilities as well. The victim of repeated physical and sexual trauma, Trash is presented undoubtedly as an empathetic character, even when he’s (literally) setting the world aflame for what he does is presented as out of his control. The treatments he needs to control his impulses have consistently been out of his reach, and each and every time he has been sent to a place that was supposed to “help” him, it has instead been a facility that has only turned him out and made him worse.

After blowing up Gary, Indiana (thank you Trash, you have good taste), Trashy gravitates to Randall Flagg’s encampment due to his desire to find a place where he is welcome, wanted, and accepted. More than that, Trashy is driven directly into Flagg’s arms for two main reasons: 1.) his suspiciously supernatural ability to ferret out explosives 2.) his recent sexual assault, and the vengeance his attacker meets at the hands of Randall Flagg’s minions.

Part of disability stereotypes center around a compensation narrative. For what we as disabled people lack, we must overcompensate in some way. A bionic foot here, superior intellect there. For Trashy, his propensity for locating explosives goes beyond pyromania. A pyromaniac, by definition, is simply a person who is “deeply fascinated by fire and related paraphernalia. They may experience feelings of pleasure, gratification, or a release of inner tension or anxiety once a fire is set.” (Psychology Today)

This does not however describe how Trash locates explosives like an imaginary radar is embedded in his head. That particular feature is purely the work of King himself, an attribute meant to be something superhuman and mystical, thus creating a Magical Cripple.

In the 2020 television adaptation of the series, writers criticized actor Ezra Miller’s portrayal of Trashcan Man, stating “the choices Miller makes border on offensive mental illness stereotypes. Their screeching line delivery of Trashcan Man’s most iconic phrase “My life for you!” sounds more like bullying imitation rather than an honest portrayal of someone with psychiatric disabilities.” (Vespe, 2021)

Like many adaptations, much of the context and background for Trashy’s backstory was missing, offering but a shortened rendering of his character subsequently flattened to one dimension. But it’s important to acknowledge that Miller, who suffers from severe mental health issues of their own, also juggled a complex character already written as a stereotype.

After going to extreme lengths to make Trashy such a complex character deserving of our empathy, King ultimately skewers them effectively creating a one-two punch figure in representation: someone with a back story, with complex aims who commits reprehensible acts but is deserving of understanding, yet falls into multiple stereotypes that harm people with not only Schizophrenia but mental illnesses in general.

Dayna Jurgens: The Bisexual, Banana-Wielding Queen [**TW: This section contains mention of sexual violence**]

Natalie Martinez as Dayna Jurgens in the 2020 adaption of The Stand.

With the information discussed so far, it may come as nothing short of a shock to discover a complexly written member of the LGBTQ+ community buried within the pages of The Stand. Completely by mistake, Dayna Jurgens blasts through multiple pitfalls in King’s writing as a female character, a queer character, and a survivor of sexual assault, making her unique within the annals of King’s bibliography.

While the original edition of the novel takes place in 1980 and its revised version in 1990, it’s important to note that the definition of bisexuality or discussion about it as a sexual orientation or identity was not as prevalent upon the publishing of the book as it is today.

Within the confines of The Kinsey Scale created by the eponymous doctor in 1948, the precedence for attraction to multiple genders had been set in modern society (not to mention of course in the millennia of human history before that). Yet despite the growing visibility of Gay Rights movements such as the Stonewall Riots, ethical non-monogamy, and woman’s liberation due to Second Wave feminism and the growing acceptance of birth control, bisexuality as a label did not take or grow in acceptance that way we know it today, and certainly did not take on its most inclusive known form of “one or more genders”. It was simply something one did, a matter of sexual engagement, all the more normalized during the sexual freedom movements of the late 60s and 70s.

Jurgens’ character is introduced along with a group of women who experience just about every woman’s post-apocalyptic nightmare: falling prey to a rapist’s fantasies of building a harem.

Forced into a group of men traveling cross country to Randall Flagg’s group, Dayna is one of several women held under duress and drugged to prevent escape. Aware that they are being followed by several of the other main characters, Dayna conspires to palm their sedation pills, using the opportunity of the groups crossing paths to stage a distraction that may allow the women to gain the upper hand on their captors. The plan works with some losses, and Dayna joins with what will become the foundational members of the Colorado settlement.

Her sexual orientation eventually comes up as an afterthought, during a brief moment of rising tensions over her evident attraction to the King’s Leading Man protagonist in the book and his Stereotypical Female Lead who is about as interesting as beige wet paint. In time Dayna becomes a valued member of the community as well, the second of the spies to undertake the mission to gather intel on Flagg’s camp.

There are many tropes that could have defined her character: the vixen, sleeping her way through the settlement and attempting to steal said Leading Man from under Miss Wet Paint’s nose. She could have attempted to navigate the PTSD from her ordeal through patterns of self-destruction which would be understandable, yet within the mark of stereotypical bisexual characters. She could face questions about her identity, irrelevant bigotry, and needless remarks (the occasional riff is made by Leading Man who is admittedly is an ignorant man from Texas). Yet, none of these things happen.

Instead, Dayna is portrayed as a complex character despite her role as a secondary, if not tertiary cast player. Prior to the pandemic, she works as a physical therapist and it is both her physical strength and emotional resilience that gain people's respect. While she ultimately does employ her sexuality as a tool in her mission, it is not framed in a way that makes her appear any more or less promiscuous than anyone else, as bisexual people are often misconstrued.

With every other woman in the book rife with some degree of racism, sexism, ageism, or even sizeism, Dayna is a welcome change from King’s miserable onslaught of poor writing when it comes to women, a three-dimensional character: and a queer one at that!

Revenge of the Negroes, Pirates, and Dope Fiends

It’s impossible to touch upon representation without discussing race within the context of The Stand, its most controversial and obvious failing. From the very plot point, King sets up a failed understanding of the way race works, his Good vs. Evil dichotomy riding upon the figures of Randall Flagg, who takes pride in tossing around racial slurs, and Mother Abigail, a jolly old Magical Negro who is all too proud in having voted Republican her entire life.

The n-word appears an astounding number of times, by context clues in attempts by King to signify who is destined for the “Good” Colorado camp, and those of Flagg’s mindset. Yet King’s own biases are present, a man belonging to the overwhelmingly white communities of New England. Residing in Maine, King had little multicultural exposure, and his description of blackness is akin to one who has only seen it on the cover of National Geographic magazine, in the form of an exploration of traditional tribal practices.

The descriptions of black people are horrifically racist, all the more pronounced due to the small number of them in comparison to other characters. King makes a point to let us know each and every time we encounter a black character, through the painstaking description of the darkness of their skin, the whiteness of their teeth, and the pronounced steps he takes to reproduce AAVE. And reflecting his presumed experience, notably, all other people of color are suspiciously absent. We see no descriptions of the dark brown skin of Indian Americans or the sun-tanned faces of Indigenous Americans that wouldn’t be out of place in the Western U.S. For a book taking place in part in Colorado, Latino Americans are suspiciously absent, as are those of Middle Eastern descent, and virtually any other ethnicity aside from African-American and Caucasian American save a boy consistently described as having “those funny Chinese-looking eyes”.

One of the most offensive descriptions comes in the uncut version of the book, in which during the societal breakdown amidst the pandemic King attempts to stoke the fears of white society by portraying what amounts to black militarized forces staging a coup and executing whites on live television:

“His colleagues, also black, also nearly naked, all wore loincloths and some badge of rank to show they had once belonged in the military. They were armed with automatic and semi-automatic weapons. In the area where a studio audience had once watched local political debates and “Dialing for Dollars,” more members of this black “junta” covered perhaps two hundred khaki-clad soldiers with rifles and handguns.

The huge black man, who grinned a lot, showing amazingly even white teeth in his coal-black face, was holding a .45 automatic pistol…

Now he spun it, pulled out a driver’s license and called “PFC Frankling Stern, front and center, puh-leeze,”

The armed men flanking the audience on all sides bent to look at name tags while a cameraman obviously new to the trade panned the audience in jerky sweeps.

At last a young man with light blond hair, no more than nineteen, was jerked to his feet, screaming and protesting, and led up to the set area. Two of the blacks forced him to his knees.

The black man grinned, sneezed, splat phlegm, and put the .45 automatic to PFC Stern’s temple.

“No!” Stern cried hysterically. “I’ll come in with you, honest to God I will! I’ll-”

“Inthenameofthefathersonandholyghost,” the big black intoned, grinning, and pulled the trigger.” (The Stand, 270-271)

Just about everything within this scene from the physical description of the bodies in it to the utilization of black men imposing violence as a tool to evoke terror is perhaps one of the most reprehensible examples of racism within the book and can be identified as far out of touch even for the time it was written.

During the 1970s, even the “radical” arms of the Black Power movement such as the Black Panther Party were rooted within the principles of Communism and Socialism, and their cultural influences sought to impose new ideals of blackness rooted in America and the African-American experience. The uniform associated with the BPP is an example of this, adopting aspects of leather culture as well as the iconic afro, elements both stemming from traditional African culture as well as American culture.

The idea of black revolutionaries taking over in loincloths is an affront to all that figures like Angela Davis, Huey Newton, and Fred Hampton held dear and serves as a far cry from what figures who gained ground working with Cesar Chavez, Leninists, and disenfranchised white farmers would have exemplified. In attempting to stoke the fears of white audiences, King paints a minstrel-like picture of blackness that is animalistic in quality not even accurate for its time.

Rat Man

Rick Aviles as Rat Man in the 1994 adaptation.

While the name “Trashy” can be evoked as a term of endearment, a character written with a degree of empathy, Rat Man gets no such treatment. He is mentioned once at the beginning of the story, in a “blink and you’ll miss it” introduction, and does not appear again until the very end, as one of The Other Black Guys.

Also known as Ratty, Rat Man gets his name from…well, we’re not really told what. Unlike Trash, he has no predilection for rats. He does not look like a rat. No rat army, or ability to summon or communicate with them.

Instead, he takes on the stereotypical trope of dressing like a pirate, because it makes sense that at the end of the world, in Las Vegas, a random black guy has to dress like a pirate.

Within the scope of fantasy, this is a trope gaining growth that may be unfamiliar to some. “What’s wrong with a pirate” one may wonder. It is essentially the equivalent of casting a black (or brown) person in the role of a thief, over and over. Relegating them to the stereotype of a criminal. Why can they not be the judge? The damsel? Why not any other role?

Perhaps the most important (or, only important) thing to know about Ratty is that he is “creepy”. This fact is pinpointed in key detail as he is the only person that Julie Lawry, a teenage girl encountered by Nick and Tom with a libido that defines her entire character does not want to sleep with. Almost every time we encounter Julie, she is attempting to blast someone through a wall with her hips, and it is The Rat Man, that dark-skinned fella speaking in AAVE who is the only man in the books who she finds too unattractive to bone. The single black man in existence on that side of the Rockies. Coincidence?

He tries of course, like the “creep” he is (ironically, he is no less creepy than Julie who is a teenager, yet doesn’t understand the meaning of the word consent). He leers and flirts, jeers and jests, a man described by King as having the same dark skin, the same white teeth, making it evident that blackness is a monolith. There are no shades. No milk chocolate, dark chocolate, caramel, cinnamon skin, or swatches of brown. No biracial people. No passing privileged, or those with 4A hair textures. King sees black people as one writhing loincloth-wearing group, who speak the same, look the same, and undoubtedly believe inthefatherthesonandtheholyspiritamen. At least in 2022, we know he does not believe we all vote Republican.

Richard The “Hehrawn” Addict

Finally, there is Richard, yet another character who does not appear in the original text, but instead only in the revised edition during a sequence that King dubs the Second Pandemic. It’s a grim spot of black humor, a series of spitfire shorts intended to shock the reader, and perhaps even illicit a laugh or two if they have a particularly dark sense of humor (such as yours truly).

Recently surfacing from sobriety, Richard breaks for air itching for a fix as the world around him collapses. Breaking into his dealer’s house to score what King dubs “hehrawn” (surely ebonics must be expressed within the narratives of each and all black characters), he finds a mountainous stash and almost instantly overdoses on what is pure product because dear Richard never thought about the fact that it wasn’t cut with anything.

The refrain used to punctuate his death is no great loss, an episodic remark that closes each and every one of these tiny little anthologies. A child falls into a well. An agoraphobe accidentally shoots herself in the face. A man jogs to death and suffers a heart attack. King isn’t intentionally discriminating in his use of the phrase, it just happens that in the context of the statement in a world where the deaths of black bodies are often treated with casualty…”no great loss” hits differently.

While the year 1978 surely wasn’t awash with the sea of ever-buzzing internet culture that today constantly dictates what is acceptable, appropriate, fair, and cancellable, it likely would have been on the common sense radar to think that an association could be made between these words and the connotation of their use with Richard, or the portrayal of one of the book’s only black men as a drug addict, the other two being a creepy pirate, literal “spear chuckers”, or wearing loincloths. As a whole, this entire book does nothing but portray black people as a mockery from beginning to end, with the most positive portrayal of Mother Abigail serving as an Uncle Tom as she plucks her guitar in the cornfields of her Nebraska home, celebrating her lifelong Republican status and letters from Ronald Reagan.

None of this personally goes into my literary critiques of the book which remain wholly separate and can be found on Goodreads, but in terms of representation, regardless of the decade, this book is a fair example that even being written in the past, there is an array of stereotypes that exist within it ranging from absolutely abhorrent, to surprisingly neutral, to decent.

Original and uncut copies of The Stand can be found on Thiftbooks the most recent edition, King’s publisher Penguin Random House (links to other providers found within), or better yet: at your local library! I read the 1990 version, which was republished in 2011 (cover pictured above).

To catch the adaptions, you can see the 2020 TV miniseries on Paramount+ and find the 1994 miniseries here.

Citations:

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/on-screen-and-on-stage-disability-continues-to-be-depicted-in-outdated-cliched-ways

https://comicvine.gamespot.com/nick-andros/4005-11178/

https://www.icphs2019.org/the-lives-of-deaf-mute-people

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/156500155776273894/

https://www.polygon.com/tv/2021/1/21/22241739/ezra-miller-the-stand-trashcan-man-episode-6-the-vigil

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/conditions/pyromania

https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/2019/11/27/misleading-media-disabilities-in-film-and-television/

https://www.awardsdaily.com/2021/06/20/five-questions-with-lisa-love-make-up-designer-for-the-stand/

https://kinseyinstitute.org/research/publications/kinsey-scale.php

https://www.glaad.org/reference/bisexual

https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/C_Glenn_Power_2009.pdf

https://www.essence.com/news/black-panther-iconic-uniforms/

https://www.thriftbooks.com/browse/?b.search=the%20stand#b.s=mostPopular-desc&b.p=1&b.pp=30&b.oos&b.tile

https://www.paramountplus.com/shows/the-stand/

https://youtu.be/gUb-wx5PO3A

#thevisibilityarchives#tva#the stand#stephen king#books#disabled#bipoc representation#lgbtq characters#essays

1 note

·

View note

Note

Per your pinned post, how about your take on Satomi Ito?

Excellent icon (Supercorp!!) and username, first of all!

Satomi is a fucking BADASS. Lady survived internment camp, government cover-ups, at least 60 years of white boy bullshit, the worst racism the US had to offer against Japanese-American citizens, at least 60 years of werewolfing, and many, many attempts on her life by not-unskilled hunters and other genocide-curious people.

Satomi was one of the most powerful characters in the wolfverse (and, since her death was so weak-sauce and lacking, I’m choosing to believe she still is). She had a massive pack, about two dozen if I recall correctly, and had a habit of adopting orphaned werewolves, like Brett and Lori or Jiang and Tierney, regardless of what they may have done in the past. She was uniquely understanding of the difficulty werewolves had with controlling their violent impulses. In 3b, we learn that Satomi spent her time in the internment camp playing Go almost non-stop so she’d never be tempted towards violence. Massive respect for both boring herself and condemning herself to a life sitting around staring at a board, and for being good at Go, which I’ve always sucked at. She also defeated countless assassins in the deadpool storyline circa s4 without losing control or taking a hit. Seriously, the woman can dodge bullets.

My admiration for Satomi is to the same degree as my outrage at her treatment by J*ff D*vis and the “casual” racism of the show and the writing. She was this incredibly powerful alpha, the oldest known werewolf and the one who taught her pack and her friends how to hide their scent, and introduced the “what three things” mantra that was the only thing able to calm down werewolves without anchors or werewolves who still struggled with their anger. She dodged bullets. She was a known friend and advisor of Talia freaking Hale.

Being killed off by Monroe and her followers in a fight that was more about Jiang and Tierney than anyone else was disrespecting the story that had already been told. I don’t think it was necessary for Satomi to die, she just died because the hunters had to kill a bunch of people for, uh, reasons. Satomi Ito was a mastermind and an incredibly wise woman, not some inexperienced werewolf who’d go to a peace summit with hunters and get shot while her back was turned. She was significantly too clever to get tricked and killed by Gerard, of all people. That we don’t see her death is even more insulting -- killing off all your characters of color is despicable enough, but mentioning that they’re killed off in passing for the purpose of talking about other characters even more so. She wasn’t given a funeral, or a burial, or even any acknowledgement. She was used for “oh no the hunters are so evil and dangerous” and nothing more.

Satomi could (and should) have been an advisor for Scott and his pack. She should have had significantly more scenes, more of her intelligence and cunning should have appeared on-screen than we learned from what other characters who got screentime learned from her, and if she had to die, she should have had an epic ending in which neither plot armor nor miracle could have saved her. She should have died how she lived, choosing non-violence over personal gain and helping other supernaturals realize that having claws and fangs doesn’t make them monsters.

Imagine the following scene:

Satomi arrives at the location for the peace summit between the wolves and the hunters. Gerard and Monroe are there with their hunters, perhaps some of the named ones who didn’t get nearly enough exploration of what sounded like really interesting stories, like Gabe and/or Nolan (also two non-white characters but who’s counting). They talk, and Gerard incites violence. The hunters attack Satomi, who came alone as asked so as not to endanger her pack and in pursuit of genuine, truthful peace. She dodges their bullets and evades their attacks, but refuses to kill them. Eventually she is compelled to strike back, but she stops herself and turns back into human form, making a point of not taking the life of a hunter who wants nothing more than to exterminate her kind, and when she stands back to let the hunter up Gerard slits her throat from behind, or something equally Gerard-y.

That kind of scene would have spurred on the final battle. It would have made very clear to Monroe and to the hunters that Gerard was not “protecting” anyone, just committing genocide. That could have been the moment that divided the hunters and allowed them to be defeated when they were unstoppable in the same situation a few episodes before the final fight. It would have been gut-wrenching and heartbreaking and horrifying, as well her death should have been. It would have said, “werewolves are not monsters, people who want genocide are”. The murder of such an important and powerful werewolf would have inspired a lot in our favorite Scooby Gang, turned neutral characters against the hunters and given the audience a much better sense of how evil Gerard was supposed to be than the “I murder werewolves for sadistic fun” we got. Instead, we got the lazy, half-assed “oh Satomi’s dead” that inspired nothing and just made the audience confused to how tired she had to be to get tricked by a couple of novice hunters.

The treatment of Satomi, as well as other Japanese (or Korean, or Black, or... well, Kali was played by a Black actress, and the various Latinx and/or Native/Indigenous actors/characters [Melissa, Scott, Nolan, Theo, Gabe, Hayden, I could go on] are white-passing to a lot of viewers and/or have little screen time and backstory, you get the idea) characters was another demonstration of how popular media favors white-passing and lighter-skinned characters of color, and Teen Wolf and its creators made no attempts to try and be better. They and darker and non-passing characters are used as motivation for the white main characters’ goals, they are killed off with weak reasoning and death scenes that, if they exist, only incite anger in the treatment of non-white characters in the audience. Those that survive for longer stretches of time are reduced to stereotypes and racist tropes. Satomi plays the wise old Asian. Deaton is reduced to the Magical Negro trope after a season or two. Boyd is stingy and unhelpful to the white mains. Monroe is violent, aggressive, and evil. Morrell is untrustworthy and self-centered (and Deaton’s sister, even though she’s way lighter? okay screenwriters). Even those characters of color who are with the good guys have small roles, meaningless deaths, and never deep and meaningful backstories. Those characters that pass may have some of those. Satomi is a great example of how Teen Wolf’s “casual” racism wasn’t nearly as casual as it appeared. It went deeper, all characters of color were affected by it, those darker and less passing even more so, and it was unfair. You’re not representing someone by giving them one character that looks like them and then whisking them away after a few minutes of screentime. The only meaningful thing said by false representation and racist stereotypes is that you’re just another racist.

TL;DR: I loved Satomi as a wise and powerful character of color, one that lived for a hundred years or more and learned and taught things that saved the characters we knew and loved in the epic final fights. I’m also angry she died so quietly and meaninglessly. I’m angry she was reduced to the role of “wise Asian” and barely got screentime. I’m very angry how representative her treatment is of the treatment of all characters of color on Teen Wolf and in other popular media, and what I’m super angry about is that this fandom and others love to gloss over racism or call it “casual” and pay no attention to the non-white characters in the source material. Characters of color are not there for representation points. They should be there because they’re important to the story and fans who do or don’t look like them can relate to and enjoy them. Satomi deserved better treatment on the show, and she deserves better treatment from the fandom.

#teen wolf#that werewolf show#just wolfy things#werewolves#satomi#satomi ito#lily mariye#asian representation#asian american representation#east asian representation#japanese representation#jeff davis is a racist pass it on#this fandom is also racist pass it on#ask box#answered ask#ask me anything#hot takes#i'm angry and here's an essay about why

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Problems with Aladdin: Orientalism, Casting, and Ramadan

Originally posted on Medium.

Edward Said and Jack G. Shaheen did not do the work they did so that movies like Aladdin would still get made.

I say this as someone who has had a complicated relationship with the 1992 Aladdin animated feature. I loved it when I was a kid. For a long time, it was my favorite Disney cartoon. I remember proudly telling white friends and classmates in third grade that Aladdin was “about my people.” Although nothing is said in the movie about Aladdin’s religion, I read him as Muslim.

When I grew older, I read Jack G. Shaheen’s book, Reel Bad Arabs, which analyzes about 1,000 American films that vilify and stereotype Arabs and Muslims. Among these films is Aladdin, which Shaheen reportedly walked out of. Shaheen spoke out against lyrics in the film’s opening song: “I come from a land from a far-away place/Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face/It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.” Although he convinced Disney to remove the lyrics for the home video release, the final verse was still there: “It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.” As a 1993 op-ed in The New York Timeswrote, “It’s Racist, But Hey, It’s Disney.”

In Edward Said’s seminal book, Orientalism (1978), he described orientalism as a process in which the West constructs Eastern societies as exotic, backwards, and inferior. According to Said, orientalism’s otherization of Arabs, Muslims, and Islam provided justification for European colonialism and Western intervention in the Middle East and Muslim-majority countries, often under the pretext of rescuing the people — especially Muslim women — from themselves. In addition to orientalism’s practices of constructing the “Orient” as the West’s “Other,” Said asserted that another major facet of orientalism involves a “western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the ‘Orient.’” In other words, it is not the Arab or Muslim who gets to define themselves, but rather the West does.

There are plenty of excellent and detailed critiques out there about how the original Aladdin is filled with racist, sexist, and orientalist tropes, so there’s very little, if anything, to say that already hasn’t been said. In her extensive report, “Haqq and Hollywood: Illuminating 100 Years of Muslim Tropes And How to Transform Them,” Dr. Maytha Alhassen argues that Hollywood’s legacy of depicting Arabs and Muslims as offensive caricatures is continued in Aladdin, where the main characters like Aladdin and Jasmine are “whitewashed, with anglicized versions of Arabic names and Western European (though brown-skinned) facial features” and speak with white American accents. Alhassen notes the contrast with the “villains, Jafar, and the palace guards” who are depicted as “darker, swarthy, with undereye circles, hooked noses, black beards, and pronounced Arabic and British accents.” In another article, “The Problem with ‘Aladdin,’” Aditi Natasha Kini asserts that Aladdin is “a misogynist, xenophobic white fantasy,” in which Jasmine is sexualized and subjected to tropes of “white feminism as written by white dudes.” Not only does Jasmine have limited agency in the film, Kini writes, but her role in the film is “entirely dependent on the men around her.”

When Disney announced plans to produce a live-action remake of Aladdin, I learned through conversations that the Aladdin story is not even in the original text for Alf Layla wa Layla, or One Thousand and One Nights. It was later added by an 18th century French translator, Antoine Galland, who heard the story from a Syrian Maronite storyteller, Hanna Diyab. Galland did not even give credit to Diyab in his translation. Beyond the counter-argument that “the original Aladdin took place in China,” I am left wondering, how much of the original tale do we really know? How much did Galland change? It’s possible that Galland changed the story so significantly that everything we know about Aladdin is mostly a western, orientalist fabrication. For a more detailed account about the origins of the Aladdin tale, I recommend reading Arafat A. Razzaque’s article, “Who ‘wrote’ Aladdin? The Forgotten Syrian Storyteller.”

Disney has been boasting about how the live-action Aladdin is one of the “most diverse” movies in Hollywood, but this is an attempt to hide the fact that the casting of this film relied on racist logic: “All brown people are the same.” It’s great that an Egyptian-Canadian actor, Mena Massoud, was cast in the lead role, but there’s inconsistency elsewhere: Jasmine is played by British actress Naomi Scott, who is half Indian and half white; Jafar is played by Dutch-Tunisian actor Marwan Kenzari; and Jasmine’s father and a new character, Dalia, are played by Iranian-American actors Navid Negahban and Nasim Pedrad, respectively. The casting demonstrates that the filmmakers don’t know the differences between Arabs, Iranians, and South Asians. We are all conflated as “one and the same,” as usual.

Then there’s the casting of Will Smith as the genie. Whether deliberate or not, reinforced here is the Magical Negro trope. According to blogger Modern Hermeneut, this term was popularized by Spike Lee in 2011 and refers to “a spiritually attuned black character who is eager to help fulfill the destiny of a white protagonist.” Moreover, the author writes that Lee saw the Magical Negro as “a cleaned up version of the ‘happy slave’ stereotype, with black actors cast as simpleminded angels and saints.” Examples of the Magical Negro can be found in films like What Dreams May Come, City of Angels, Kazaam (which also features a Black genie), The Green Mile, The Adjustment Bureau, and The Legend of Bagger Vance. In the case of Aladdin, the genie’s purpose is to serve the protagonist’s dreams and ambitions. While Aladdin is Arab, not white, the racial dynamic is still problematic as the Magical Negro trope can be perpetuated by non-Black people of color as well.

I need to pause for a moment to explain that I don’t believe an Aladdin movie should only consist of Arab actors. Yes, Agrabah is a fictional Arab country, but it would be perfectly fine to have non-Arabs like Iranians, South Asians, and Africans in the movie as well. That’s not the issue I have with the casting, and this is not about identity politics. My problem is that the filmmakers saw Middle Eastern and South Asian people as interchangeable rather than setting out to explore complex racial, ethnic, and power dynamics that would arise from having ethnically diverse characters existing within an Arab-majority society. Evelyn Alsultany, an Associate Professor who was consulted for the film, states in her post that one of the ways Disney tried to justify casting a non-Arab actress for Jasmine was by mentioning that her mother was born “in another land.” However, this seems to have been Disney doing damage control after they received some backlash about Jasmine’s casting. The result is convenient erasure of an Arab woman character. Moreover, the change in Jasmine’s ethnicity does little, if anything, to reduce the film’s problematic amalgamation of Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures. Alsultany writes that “audiences today will be as hard pressed as those in 1992 — or 1922, for that matter — to identify any distinct Middle Eastern cultures beyond that of an overgeneralized ‘East,’” where “belly dancing and Bollywood dancing, turbans and keffiyehs, Iranian and Arab accents all appear in the film interchangeably.”

Other examples of how the film conflates various Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures is highlighted in Roxana Hadadi’s review: “Terms like ‘Sultan’ and ‘Vizier’ can be traced to the Ottoman Empire, but the movie also uses the term ‘Shah,’ which is Iranian monarchy.” Referring to the dance scenes and clothing, she writes they are “mostly influenced by Indian designs and Bollywood styles” while “the military armor looks like leftovers from Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven.” An intersectional approach to the diverse ethnic communities represented in the film would have made for a more nuanced narrative, but this would have required a better director.

Speaking of the director, it is amazing that, of all people, Disney hired Guy Ritchie. Because if there is any director out there who understands the importance of representation and knows how to author a nuanced narrative about Middle Eastern characters living in a fictitious Arab country, it’s… Guy Ritchie? Despite all of the issues regarding the origin of the Aladdin story, I still believed the narrative could have been reclaimed in a really empowering way, but that could not happen with someone like Guy Ritchie. It’s textbook orientalism to have a white man control the narrative. I would have preferred socially and politically conscious Middle Eastern and Muslim writers/directors to make this narrative their own. Instead, we are left with an orientalist fantasy that looks like an exoticized fusion of how a white man perceives South Asia and the Middle East.

Lastly, I have to comment on how this movie was released during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. In fact, the film’s release date, May 24th, was just one day before the last ten days of Ramadan, which are considered to be the most important in the month. During Ramadan, Muslims around the world fast — if they are able to — from dawn to sunset every day for 30 days. The time when we break our fast, iftar, typically involves dinner and prayer with family, friends, and/or the community. But Ramadan is more than just about fasting, it’s a time of self-reflection, compassion, and strengthening our connection with Allah, our loved ones, and community. I don’t believe Disney released Aladdin during Ramadan intentionally. If anything, I think the film’s release date is reflective of how clueless and ignorant Disney is. It’s so ridiculous that it’s laughable.

I don’t want to give the impression that Muslims don’t go out to the movies during Ramadan. Of course there are Muslims who do. I just know a lot who don’t— some for religious reasons and some, like myself, for no other reason than simply not having enough time between iftar and the pre-dawn meal, sehri (I mean, I could go during the day, but who wants to watch a movie hungry, right?). Even Islamophobic Bollywood knows to release blockbuster movies on Eid, not towards the end of Ramadan.

But this isn’t about judging Muslim religiosity during the holy month. No one is “less” of a Muslim if they are going to the movie theater or anywhere else on Ramadan. My point is that Disney has not shown any consideration for the Muslim community with this movie. They did not even consider how releasing the film during Ramadan would isolate some of the Muslim audience. It’s clear that Disney did not make efforts to engage the Muslim community. Of course, there is nothing surprising about this. But you cannot brag about diversity when you’re not even engaging a group of people that represents the majority of the population you claim to be celebrating! In response to Shaheen’s critiques of the original Aladdin cartoon, a Disney distribution president at the time said Aladdin is “not just for Arabs, but for everybody.” But this is a typical dismissive tactic used to gloss over the real issues. No doubt Disney will follow the same script when people criticize the latest film.

I don’t have any interest in this movie because it failed to learn anything from the criticism it received back in 1992. The fact that a 1993 op-ed piece titled, “It’s Racist, But Hey, It’s Disney” is still relevant to the live-action version of a film that came out 27 years ago is both upsetting and sad at the same time. As I said earlier, Edward Said and Jack Shaheen did not exhaustively speak out against orientalism, exoticism, and vilification to only see them reproduced over and over again. Of course Disney refused to educate themselves and listen to people like Shaheen— their Aladdin story was never meant for us.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Transcendence of Stereotypical Norms in Media Texts

Since I was a young girl, my mother always made sure to raise me in diverse settings in hopes to develop my adaptability skills and well-roundedness. All of my life we lived in an African American upper-middle-class neighborhood in Washington, D.C. I went to schools in low-income areas like Anacostia and wealthy areas like Georgetown. Although my mother had good intentions with her school choices for me, I struggled to find my identity in both of these settings. I found myself posturing and conforming to what I thought was acceptable; even then I felt like an outcast. I was always asked about my hair and “why it looked like that” or asked, “why I talked so white”. These issues of shifting and isolation are not uncommon among Black women in America. We are constantly trying to fit into molds or break out of the ones cast for us. This is especially hard to do when society’s understanding of us is formed by stereotypes reinforced by the media. There are hundreds of examples in contemporary media where negative stereotypes of Black femininity are portrayed. However, in recent years there has been an increase in more dynamic depictions of Black femininity. One example is found in the 2018 film Bad Times at the El Royale, where character Darlene Sweet transcends the traditional tropes of Black femininity.

Bad Times at the El Royale is a neo-noir thriller film that follows the stories of seven strangers who meet in a mysteriously isolated and run-down hotel in 1969 Lake Tahoe. Each character has their own motives as to why they found their way to this whimsical hotel and as the plot develops the viewers are able to understand the complexities of each character’s narratives. First, we meet Father Daniel Flynn who is introduced as a priest but is actually a bank robber named Dock O’Kelly who came to the El Royale to recover money he stole 10 years prior. Next, is Laramie Sullivan Seymour, who is an arrogant vacuum salesman who doubles as an FBI agent that came to the El Royale to recover surveillance devices from the hotel. Then we meet Miles Miller, who is the hotel's only employee. By the end of the movie, it is revealed that he is a traumatized Vietnam War sniper who has killed over 100 people. Lastly, is the twisted cult escapee Emily Summerspring who kidnaps her younger sister, Rose Summerspring (who is under steadfast control of the sadistic cult’s leader, Billy Lee). The hotel itself also has a very bizarre past as it used to be bustling with high profile celebrities and politicians, but behind closed doors, hotel management would record their guests’ sexual encounters and sell them. As the movie’s plot develops the viewers are able to understand the depth of each character and all of their grueling pasts. However, there is one character who provides hopeful relief to this gory film, songstress Darlene Sweet. Unlike her fellow characters, Sweet’s identity remains the same throughout the film. This does not take away from her dynamic role in the film's plot and her robust personality. Initially, the audience is able to understand her as a former background singer who is traveling to Reno, California to fulfill her dreams of being a lounge singer. Sweet is full of poise, wit, determination, and modesty. Ultimately, Darlene’s character challenges tropes widely portrayed by Black female characters.

There are a number of oppressive myths that are constructed and circulated which contribute to how Black women are seen, understood and classified. Three of these myths include Jezebel, Mammy, and Sapphire. Each of these myths are rooted deeply in slavery and the social, economic and political persecution of the Black woman. Jezebel suggests the myth that Black women are sexually promiscuous and irresponsible. It reduces the value of the Black female to the efficiency of her body. The Mammy myth speaks to the social limits of Black women during slavery which categorized them as domestic, loyal, motherly, and overly-submissive. The Sapphire myth portrays the paradox of unwavering strength in Black women; often characterizing us as unfeminine, invulnerable, angry and loud. These stereotypes maintain the social foundations that uphold white supremacy and patriarchy within this society. It is important for both Black women and other demographics to see representations of Black femininity that challenge the typical architypes of Black women. Darlene Sweet’s character is the perfect example of this challenge. Her character does an outstanding job of being, “neither a martyr nor a magical negro. Neither a mammy nor a jezebel, nor is she a token or a helpless damsel. She is smart and cautious and ready to fight, but only if she has to. And this is a refreshing sight compared to how we normally see Black women written and conceived of in films … especially as the sole Black character” (Brown, 2018). Throughout the film, Darlene Sweet encounters many of the microaggressions, stereotypes, and the oppression experienced by Black women in America every day. Nevertheless, her reactions to these experiences display her character as transcending the tropes historically portrayed by Black women in media texts.

In the second scene of the movie, Darlene Sweet and Father Flynn meet Laramie Sullivan in the lobby of the El Royale as they wait for Miles to check them in. As aforementioned, Laramie is very arrogant and narcissistic and this is unwavering throughout this scene. He does everything from belittling Darlene by referring to her as “girl”, to forcing a cup of coffee in her hand after she insisted she didn’t want any (Goddard, 10:44), then suggesting that she was a prostitute when she didn’t want to room near Father Flynn, “Miles! She doesn’t want to room near the priest. It’s not like we didn’t see her walk in her with her own bedrolls under her arms”(Goddard, 16:35). All throughout Laramie’s microaggressions, Darlene held her composure, focused on what she came to the hotel for and remained respectful (however, only to those who deserved it).

In the scene titled “Room Five” (Goddard, 35:10) the audience gets an in-depth look at Darlene’s backstory. The scene opens up in a recording studio, where Darlene is one of three background singers. During her recording session, she decided to insert her creative genius into her background vocals by adding unrehearsed runs to the melody of the song. Immediately, the producer of the record label cut the recording to have a private meeting with Darlene where he gave her an ultimatum, “Darlene, I think you have a choice here. Give me one year of your time and I can make you a star…. or you can continue to treat my time as disposable and keep scrounging for back up gigs until they dry up”(Goddard, 38:51). In this scene, Darlene’s male counterpart is constantly divulging his power by waging his job against hers in hopes of intimidating her into submission. Both the lobby scene and “Room Five” scenes reflect the constant oppression Black women face socially and professionally, whether in passive (Laramie) or aggressive (the record producer) ways. Darlene does not use loyalty, submission, ignorance or cooning to make the situation less uncomfortable in either scene. Instead, she uses calculation to focus her intentions and actions. The end of “Room Five” alludes to Darlene quitting her job as a background singer so she could focus on saving money to fund her career as a lead singer in Tahoe; her dream is realized in the final scene of the movie.

The relationship between tropes in the media and ideologies formed in society is circular. On one hand, we internalize what is portrayed of us and work hard to prove these archetypes wrong. On the other hand, we work hard to conform to what the greater society considers normal. However, focusing on characters that transcend the widely circulated stereotypes of Black femininity, like Darlene, can teach both Black women and the rest of society valuable lessons about the true essence of being a Black woman. Characters that transcend historic caricatures teach us that we can be both attractive and smart, driven and feminine, opinionated and poised, challenged and respectful, Black and talented.

In one of the closing scenes, when the plot reaches its peak, Darlene, Miles and Father Flynn are being held hostage by Billy Lee when she says, “ I’m not even mad anymore, I’m just tired. I’m just bored of men like you. You think I don’t see you for who you really are? A fragile little man preying on the weak and the lost” (Goddard, 1:57:00). Darlene’s relentless words to the man who has her life in his hands is parallel to the perspectives many Black women have across the nation. Those who have power hide behind their titles, gender, and race to oppress Black women on all scales, but many Black women take Darlene’s approach and refuse to submit to them. Black female leaders like Michelle Obama, Beyoncé, Audre Lorde, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and hundreds of others choose to step out of the molds cast for them every day for the sake of Black femininity. In conclusion, more realistic representations of Black women in media texts are essential to making opportunities and respect equivalent across genders and races.

References

Goddard, D. [Director/Producer]. (2018). Bad Times at the El Royale [Motion Picture]. USA: Goddard Textiles, TSG Entertainment, & Twentieth Century Fox.

Brown, S. J. (2019, April 16). The underrated brilliance of cynthia erivo as darlene sweet in ‘bad times at the el royale.’ Retrieved October 21, 2019, from The Black Youth Project website: http://blackyouthproject.com/the-underrated-brilliance-of-cynthia-erivo-as-darlene-sweet-in-bad-times-at-the-el-royale/

0 notes

Photo

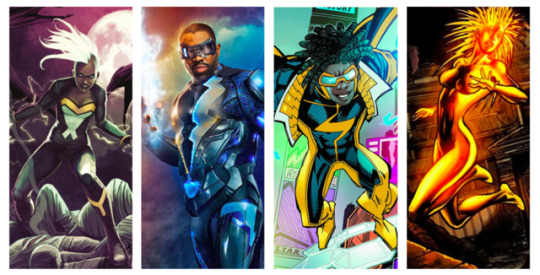

Why Do So Many Black Superheroes Have Electricity Powers?

Growing up as a kid who loved comic books, I spent many an afternoon running around the park pretending to be a superhero fighting all manners of evil. Fun as it was, the process of picking out which superhero I wanted to be always stressed me out for one particular reason that still bothers me to this day.

Back then, it felt odd flipping through my mental Rolodex of characters and realizing that, if I wanted to play as a black hero, it was almost guaranteed that I’d be doing jazz hands to simulate zapping people with lightning. See, there are a lot of black comic book characters with electricity-based superpowers. A lot.

Certainly, there are a number of differences between Storm, Black Lightning, (Black Lightning’s daughter) Lightning, Black Vulcan, Juice, Static, and Shango the Thunderer. But there’s also something about them all that feels derivative at best and stereotypical at worst, considering that the vast majority of the most popular black superhero characters were created by white men. (It’s worth pointing out that Black Vulcan was created by Hanna-Barbera for the Superfriends cartoon, which producers felt needed a black character even though Black Lightning already existed. It’s also worth pointing out Black Vulcan was created after Black Lightning’s creator Tony Isabella left DC over creative differences.)

The earliest black superheroes like Black Panther and Luke Cage crossed the comic book color line with their technology and super strength, but over the years, electrokinesis has seemingly become to go-to power black characters are most often assigned. But why?

In the fifth issue of Mark Waid and Peter Krause’s Irredeemable, Volt, a member of the book’s answer to the Justice League, apprehends a kidnapper while sheepishly admitting to the people around him that yes, he’s a black hero with electricity powers and yes, he knows that it’s a Thing™, and he’s kind of embarrassed about it.

While Volt’s powers are a playful jab at superhero comics as a whole, they do raise a number of questions about what it means exactly when creators choose to turn black characters into walking, talking batteries. Taken purely at face value, it’s not difficult to understand what makes electrokinesis popular with creators. For one thing, it can make for some of the most visually arresting art you can imagine, and with the right sort of creativity, electrokinesis can be used in a variety of novel, clever ways beyond simply discharging energy.

Writer Matt Wayne has helped give Milestone Media and DC Comics’ character Static his signature voice on a number of projects like the Static Shock animated series and various comics like Static and The Brave and the Bold: Milestone. When I spoke with Wayne recently, he assured me that, when creating a new character and deciding which powers they should have, every comics writer sits down and considers how similar their creation will end up to others that came before them.

Static’s powers, Wayne told me, were meant to be an extension of his geeky personality and the kinds of science fair projects he enjoyed working on. In other cases, though, Wayne reasoned that electrokinetic powers were the perfect way of having a black hero around who could participate in a fight, but not necessarily be the one to win the fight.

“I think maybe some of it is that these kinds of heroes are usually physically vulnerable. So they get their hits in and get taken out. There’s definitely an unconscious undercutting of black heroes, keeping them just shy of being a heroic ideal, that used to be more pronounced,” Wayne said. “In that vein, maybe electricity can be an unconscious expression of the hero’s ‘tamable’ nature?”

While it’s heartening to hear directly from a writer about how much thought they personally put into crafting a character’s identity, the point still stands that black heroes with electrical powers are an established trope.

Personally, the thing that’s always stuck with me about most black heroes with nature-based power sets is the very thin line writers and artists have to walk to make sure the character isn’t being depicted as a “savage.” The idea that black people are inherently closer to nature is one of the larger undertones to the problematic magical negro trope that many black characters are often hamstrung by.

The Black Electricity Trope reads like a distant cousin to the Magical Negro, in that they’re both established formulations of a character whose most defining qualities are a preternatural understanding and command of natural force.

It goes without saying that Storm is perhaps the most iconic example of a the Black Electricity Trope, but she’s also a character who’s transcended much of its limitations as a result of being written and depicted thoughtfully across a variety of different mediums. Storm isn’t just a black hero who throws lightning bolts, she’s one of the most complicated and nuanced comic book characters created in the past 40 years.

We’ve seen Storm as both a lethal weather goddess and a vulnerable human. She’s incredibly strong, but you always get the sense that at the center of whatever devastating weather phenomena she’s manifested, there’s a human who’s just as powerful even when she doesn’t have her powers.

It’s that sort of solid characterization and fleshing out of a personality, Wayne told me, that’s the key making sure that a character doesn’t become reduced to a two-dimensional stereotype.

“Know who your character is. Black Lightning wouldn’t defeat a villain the same way that Static would,” Wayne said. “Although, Black Vulcan’s approach would probably be indistinguishable from Black Lightning’s. The only difference would be who gets paid.”

#black superhero#black superheroes#black superheroine#black superheroines#storm#black lightning#lightning#black vulcan#juice#static#shango the thunderer#matt wayne#milestone media#dc comics#comic books

0 notes