#authorial assumptions ask game

Note

for the based on your fanfics ask game: organized, dedicated to your passions, and lover of research

That is an incredibly generous and flattering way to put it. 😅

🖤🤍💜 Thanks for playing!

Send me asks with your assumptions about me based on my fanfics.

#Hyperfixated anxious perfectionist squad let's go#But seriously a lot of it comes from me liking stories that make sense and wanting my story to make sense#I feel like it's kind of the... bare minimum respect I can show to people who take the time for my work is to leave them satisfied#I love stories that reward curiosity and so I want to write stories for other people like that#authorial assumptions ask game#celebrimbor-of-eregion's ask game#strawberrycamel#3WD answers

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/olderthannetfic/729708592592306176/how-about-a-different-discourse-death-of-the

What this ask is missing, a bit, is that Death of the Author *does* mean that the author’s take on things is no more or less valid than anyone else’s. It’s about decentering authorial intent in analyses of media. Barthes is pretty clear and quite pointed about it in the original essay.

What bothers me about misuses of it and what I think this anon means to say is when people start decentering the actual *text*. The idea behind Death of the Author is also that the text stands alone. You don’t need to look at any extra shit to understand it. As you said, it was a response to a mode of analysis that obsessed over plumbing through author biographies.

The issue with what people do in fandom is they ignore the text. “I don’t like this element of canon, so it doesn’t exist.” (Which is different from arguing that it’s there but it sucks because of XYZ reasons, so I’m going to consciously ignore it in my fan works. This is when people just act like it isn’t there in the text in the first place.) “You have to take my bizarro world out-of-nowhere headcanon that is based on nothing except that I want it to be true, that I love this character and I wish they were XYZ therefore they are” and take it just as seriously as headcanons that actually engage with what’s in the show/video game/book/movie/whatever and use that as their basis (like building off something that is subtextual in the original work).

Granted we all do this to some degree, we all come to a text with our own biases and you can’t *always* easily separate those out, and that can affect, for instance, your interpretation of what the subtext is, but I think the irritating fandom behavior is when this kind of ignoring-the-text-to-substitute-your-own-reality is this very deliberate sort of laziness. The annoying thing in my current fandom is people who are fans of this one ship that they insist is the most progressive and other people just don’t see the scintillating “subtext” of because we are bigots or whatever, between two characters who don’t interact that much for two MCs and when they do it’s not at all shippy (but these characters both have very shippy subtext with different characters), but where these people think the ship *should* exist because of their identities. And their “evidence” for the ship is always gifsets taken way out of context and not including the dialogue that makes the non-shippy context for that scene very clear (including that it might actually be shippy for conflicting pairings). It’s like this bizarre version of “close reading” that strips out the largely context *deliberately* in order to make a particular conclusion seem more compelling than it actually is.

Anyway, all that ignoring-the-text stuff is STILL bad analysis per DOTA. Since the point of DOTA is to go based on the text, if you’re obscuring the text you’re kind of just installing yourself as a new author.

This is why DOTA doesn’t mean “anything goes.” It just means “authorial intent is just one interpretation that doesn’t have to matter.” It doesn’t mean other stuff we use in analysis doesn’t matter, and if anything the point is to make it even more text-centric than the older author-centric analyses were. People can still disagree about what the text says, of course, but they should both be going back to it in how they construct those arguments, and not, like those shippers, deliberately ignoring chunks of the text that weaken their arguments.

--

I don't think all of them are consciously throwing out actual canon, but they are often throwing out all context that would help evaluate subtext.

Like... if you're analyzing a Marvel movie, you might ignore what the director said in an interview, but you probably shouldn't entirely ignore the fact that it is a Marvel movie and apply assumptions that make sense for some arthouse film.

And, yes, if you're arguing for shippy subtext, even unintentional on the part of creators, "I like this ship because..." needs very little, but "This ship has more support than this other ship" requires going back to the actual text and looking at it in its totality.

There's a lot of faux-intellectualism around garbage like TJLC where people try to make themselves feel smart by using the language of close reading while having the media literacy of a bucket of rotting fish.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Huge Spoiler/EP1) The sixth body in the first Twilight and identification errors

In the official explanation the first Twilight in the first game says there was nothing. Kanon and (the accomplice) Hideyoshi are pretending that Shannon was lying in a dark corner. The sixth corpse doesn't exists. Lambdadelta also confirmed the deaths of all unidentified corpses (which is an actual problem, explained later).

Battler was saying this when he saw the crime scene:

"How many people died…?……You're fucking kidding me! That's more than I can count on one hand! Damn iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiit!!!

This is also true in the Japanese version. Retrosprectively, many noticed that it's kinda off. Battler has all his 5 fingers on each hand so I can exlude that one of his hands was missing a finger. Maybe it was exaggeration or assumption, but let's say Battler has a good overview of the scene. Of course he could see 5 very clearly and could described the damage of their faces

A side note of this, Battler was identifying 4 corpse by their clothes. It was briefly discussed by Gretel, Battler and Beatrice in EP4. I saw many people said "Battler is the detective and says X is dead so it's true". This might be true but identifying by clothes is a huge mistake by the detective and Battler intuitively assumed the corpses are the people he know. Thankfully, Beatrice won't use this move anymore. A second note: Any bodies who haven't seen in full shouldn't be declared dead. This is true for later Episodes. In that means the sixth body that Battler "could" see a part of can be dead or alive.

Anyway, back to the sixth corpse. We have a simple problem with the narration because it was George who asked if a sixth person was in the garden shed and the pov narration switched to the unreliable authorial narration. Hideyoshi is really unreliable here because could lie about even seeing the face (as George mentioned Shannon's face Hideyoshi responded accodingly in a wiser manner.

"...Why...? After all, I won't be able to see Shannon's face again, right...? So, why can't I see... her last face...?"

From here, we have more possibilities.

"Illusions to illusions. ...The corpse that cannot return to earth returns to illusions."

(let's forget about the canon culprit for a while) Will's explanation is vague and speaks about faking death. The obvious answer would be lying about the existence of the corpse. Incorporating the previous collected information could also mean that the body (dead or not) was real and was tainted with a false identity and fake blood, Kanon and Hideyoshi failed to identify it and Hideyoshi felt to give George a proper, delicate answer and an excuse not to see his dead girlfriend and lied about the smiling face.

"OMG there are only 16 humans on Rokkenjima! YOU R WRONG!"

If we forget the canoncity for now that can easily means that the sixth body can belong to someone who prepared one of the 4 daceless body with their clothes and a wig, effectly faking their death. Taking into the account that the sixth body belongs a female (breasts) it could be Rosa or Kyrie.

"It's not CANON!"

There's a possibility that a substitute corpse exists. [Gold Truth] The sixth body belongs to Erika Furude who was found dead before by the culprit comitted the crime. Thus, the culprit changed their plan and included the extra corpse in their plan. It was hidden in the dark corner just in case.

If you think about it, in the canon, EP1 was the only Episode where Shannon "dies" first before Kanon and it was avoided to remove her corpse by actively lying about it and place it in the fate of the roulette. In my theory, I think it was strange to create such a crime because Battler was free to go in. If he went in before Hideyoshi made a remark about Shannon's corpse then it would a whole Episode about "is Shannon the killer because she didn't go to her guest house shift?". If Hideyoshi made a remark about Shannon's corpse and Battler disproved this it would Shannon and also Hideyoshi/Eva suspicious. In these cases, it makes more sense, for the culprit's best interest, to change their plan (using another person as the 6th corpse and "killing" Shannon or Kanon in the 2nd Twilight) or using a real substitute with make-up to complete the 1st Twilight. The garden shed is a nice hiding place and Kanon usually tends the garden. This might be a good reason to consider a substitute corpse.

(yeah I know about Eva's hints but it was started by Battler anyway) . Since I mentioned that Hideyoshi lied for George's sake I think it can be explained rationally. After a heated discussion in the parlor Eva tried to convince George to go with them. I'd say it's a 50/50 chance Eva/Hideyoshi were accomplices. The 2nd Twilight can be explained with an assault (cutting the chain/unlocking the room with a master key and rushing the guest room, the chain could be cut afterwards). I read people said they let the culprit in but it doesn't really explain why Eva found lying on the bed.

Well, that's all for today. Happy thinking!

0 notes

Note

hey mittens! i know you’ve written off the finale at this point (and haven’t we all), but i was just wondering: do we know whose idea it was to have kripke co-write that ep? because like, in hindsight, that was...a choice, and i’ve been thinking that might explain SOME of the weirdness of that ep (emphasis on SOME because uh. i really do think that some of the cringiest details didn’t come from writers at all). anyway—thoughts?

I don’t think Kripke had anything to do with writing the final ep. It just... felt like a Kripke ep, and I’m starting to think that Dabb did that intentionally. He’s the most meta writer the show might’ve ever had, and in refusing to allow Sam and Dean to live out past their ultimate victory, in choosing to “force an ending” on the characters instead of leaving their world “open” with no concrete ending, he succeeded at the task that Chuck- as Kripke’s avatar in the original story of Supernatural-- had failed to do.

Dabb, in a very real sense, is the one who “ended the story of Supernatural.” He wanted to bring it full circle, to “close the universe” and make it “reboot-proof.” This is something he’s talked about going back as far as SDCC 2019, and many of us had hoped that would mean something “better” than what Chuck wanted for the Winchesters, and for Cas.

I was hoping, and watching the show for the last few years under the assumption that Dabb’s in-story avatar was more a combination of different characters. At first, Billie, who started as a reaper but was elevated to the role of Death (like Dabb himself started as a writer who became more important to the telling of the tale, and eventually became the final showrunner who would eventually reap the show in the end, as it were).

After Jack’s introduction, I wondered if he was going to “grow into the role” of the Authorial Avatar. After all, he served as a mirror for all three other characters, reflecting their stories back at them and allowing them to process their own emotional and psychological issues by helping Jack through them. I wrote long ago, back in s13, how this enabled TFW to sort of graduate from student to master, in the martial arts sense of the word, because one truly only completes learning a thing through the process of teaching others.

And then the Empty became involved as an actual being that manifested through the identities of others, and didn’t really have its own identity other than “I need to sleep, stop disturbing me!” which... felt like it might’ve become relevant when Jack’s power was able to break through into its realm.

Then these three beings began plotting the final overthrow of the Original Author. One laid claim to the lives of Sam and Dean (Billie), one laid claim to Castiel (the Empty). We watched Jack-- the incarnation of “balance” and the vehicle through which the show demonstrated what the human soul’s function is, what the function of angelic grace WITHOUT a human soul’s function is, and what Jack as a whole being with both actually is, as he fully came to his own understanding of what humanity, human love, and the responsibility and function of cosmic power and balance is within himself.

I never doubted (especially after he consumed Michael’s grace and made that power his own) that Jack’s function would be as the ultimate role that Chuck had been trying to force on Dean since s11-- “the firewall between light and darkness.” That Jack would be the crucible to fully unite the power embodied in Amara and Chuck. Chuck’s ending was about as poetic as it gets, and I 100% appreciate Jack’s “end” in the narrative that isn’t really an end for him, because the story also implied that Chuck’s original “problem” stemmed from his wanting to give himself an ego and play with his own creation like so many tinkertoys, to force his will on a universe he created to be ruled by the will of others.

The ultimate act of Team Free Will left Chuck fully human and an effectively blank book, with no power to force anyone else to play his games. Excellent, right? Poetic even!

But the story wasn’t really over, because in our world, there was one more episode, a coda fic if you will. And all of the characters I’d associated with Dabb-as-avatar were... rendered mute. Billie was dead or dying in the Empty, Jack came into his full power and had already healed the universe, implying that the Empty’s conditions were fulfilled and could finally go back to sleep.

Unfortunately, Chuck’s Book, while appearing blank, still contained all the words. Only Death could read them, and as far as we know, nobody in that universe had ascended to that role. But in our universe, we know that’s Dabb’s function in the narrative. What sort of ending could he write?

Most of us hoped that it would be a “once more, with feeling” sort of “you can finally lay down your arms and make a new life for yourself” ending. Many of us were baffled first off that Jack wouldn’t have brought Cas back from the Empty to Earth. We never really had a satisfactory explanation in canon of what happened there. Was Cas actually dead? What function does he have if he’s in Heaven? Has he been relegated to a role of duty and service as punishment for daring to yearn for human things? It just... it felt like the final stab from a story that had just told us that he truly has been the one disrupting for in Chuck’s story, that he was something that Chuck could never force out of the story or control, who demonstrated free will and learned to love humanity because of Dean, and yet doomed to never have that for himself. Most of us felt that line in 15.18 deserved subversion in the aftermath, and yet we never even get concrete confirmation that he’s even really alive in the same way he was before. It’s... what Chuck always wanted for Cas, to shunt him out of the story and render him powerless and plotless.

What did Chuck want for Sam and Dean? What story did he force them into over and over again? One of them tragically dead and the other miserable and mourning. He wrote billions of iterations of this exact story, over and over throughout billions of universes created for the sole purpose of doing exactly this to every incarnation of Sam and Dean he possibly could. Most of us hoped this might be the ONE universe where that was subverted, like it was the ONE universe where Castiel refused to fall in line with Heaven’s orders and plans. But nope, Dean died tragically (almost immediately after saying in canon that the only way they could honor Cas and Jack’s sacrifices for them was to keep living), and Sam lived a rather bleak and hollow life where the only thing we know he did was to raise a son named for his dead brother.

Chuck would’ve been freaking DELIGHTED!

Which... brings us to Heaven... where we get the vague hint that Cas “helped” Jack “knock down the walls” and make it a paradise that Dean would love and feel rewarded by. We never actually find out what role Cas played in that, or if he was also there in some capacity. But how I’ve always personally understood Heaven as it was in Chuck’s creation, was as a self-sustaining and ever expanding Destiny Generator, like a power generator or a giant battery where each Heaven Cubicle functioned as a cell. The show itself has been using the soul-as-power-source for ages (it was pretty much the running theme of s6-- it’s the souls!-- and this theme was returned in force in s11, culminating in the “soul bomb” plot of (gasp!) Andrew Dabb’s season finale.

Heaven was beginning to break down as a “machine” and a power generator not for lack of human souls, but for lack of angels to maintain the structure of heaven itself. In one of his first episodes, Cas even described the function of angels as being “agents of fate.” Their sole role was to literally “hold Chuck’s narrative together.” Metaphorically in the story-- in the original Apocalypse as the guides who tried to force Sam and Dean into the roles they were destined for-- as well as metaphorically in Heaven which was the “battery” that gave the angels their power in the first place. Remember what happened to Cas when he has been “cut off from Heaven” and began to lose his powers.

So the way I’d always understood the function of Heaven in Chuck’s story was exactly that. Without Chuck’s narrative, the walls would fall and the paradise Jack’s birth heralded would come to fruition THERE. Because as long as there is life, and free will, and more than one person on EARTH, that sort of paradise is an impossible dream. We’re seeing that exemplified now in real life, actually, with people claiming their rights and freedoms are being infringed upon by being asked to wear a mask and limit their social interactions to prevent the spread of a deadly virus. Does their “freedom” override the “freedom” of others who would prefer to remain alive and not infected by a virus that could kill them? It’s an impossible balance, because true freedom cannon exist in life without compromise and sacrifice.

Which brings us to Dean, and his essential humanity, which had been exemplified in his selfless love of humanity so strong that he became a cosmic disrupting force of his own by simply refusing to let Chuck’s story defeat him. He struggled with this throughout s15 as Chuck told him that his life had never truly been his own, and that he’d always been a character in a bigger story. He’d finally begun to feel at peace with who he was, with the family he’d made for himself, and everything and every experience he’d endured that had shaped him into the person he’d become, and Chuck’s revelation led him to doubt everything. In the end, he was finally able to see what truly DID matter, what really WAS real (thank you to 15.17 for confirming that Cas was one of those things that Chuck had also never intended to be part of his story, and that Cas truly had always chosen Dean freely, because his doubt of Cas was one of the main things hurting Dean in s15, epitomized in his crisis in 15.09 in Purgatory). So the fact that Cas was not “allowed” to come back to Dean afterward feels... punitive. The fact that Dean was not “allowed” to actually experience a real human life on the Earth he’d devoted his entire life to saving, the fact that Sam was never able to achieve peace and happiness in a life he’d struggled to find balance between a destiny he’d never wanted and a normalcy that had been merely performative for decades because shoving the majority of his life experience down to play at being “normal” was never truly possible, and required truly accepting all of himself to actually free himself from the half-life we saw him live after Dean’s death... all of that just... it’s exactly what Chuck would’ve wanted for all three of them.

And it’s depressing af, that when given the power to “end the story of Team Free Will,” Dabb chose to enact Chuck’s final draft, rather than handing blank books to these three to write their own lives. And it just looks like Kripke’s writing, because it kind of is his story. We just hoped it wasn’t, and that the final avatar of The Author in the story would be TFW themselves. But that was probably never meant to be. Because destiny is apparently still stronger than human free will, and isn’t that just depressing af.

#spn 15.20#dabb vs cars#heaven hell purgatory and the empty#that's what free will is#or apparently is not... which is the main reason the finale is fucking with my head honestly#i just can't see even paradise heaven as a reward#it always felt like the final concept to be subverted by the narrative but the narrative loved itself more than life#and so it goes#skvwalkering

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, big fan of a lot of your shitposting, was wondering if you had a tabletop game recommendation for playing as literal dragons and other varieties of non-human monsters of fantasy. Bonus points if 1) Adventurers are an enemy, and 2) after establishing species, you can become a specific "class" of player, like a mage, warrior, or the like.

This is going to be another one of those posts where somebody asks “does such a thing exist?”, and I reply “it’s actually a very popular premise with dozens of published games devoted to it, so we’re going to have to make a few assumptions to narrow things down a bit” – even restricting our consideration to games where you play as D&D-style beasties in particular (and further to games that are specifically about that, rather than merely offering it as an option) leaves a lot of territory to cover. Thus:

For a game that’s literally just 100% the thing you described, there’s the classic Monsters! Monsters!. This one came out way back in 1976, meaning it’s only slightly younger than the tabletop roleplaying hobby itself! Nominally a Tunnels & Trolls supplement, it’s a standalone game in practice, and – unusually for a game of its age – fairly rules-light even by modern standards. It is, however, quite typical for games of its era in terms of featuring some very awkward gender politics, so maybe not the best choice if you’re in the market for a game whose authorial voice won’t annoy you on general principle.

If you’re aiming more for lowbrow comedy where everybody dies all the time, you might get some mileage out of either Kobolds Ate My Baby! – whose premise I trust is self-explanatory! – if you’re looking for a pick-up-and-play game; or, for something a little weightier, perhaps Goblin Quest. The latter is developed by the creator of Honey Heist and Crash Pandas, with an art team that includes Tumblr’s @iguanamouth, and plays like nothing so much as Lord of the Rings meets Paranoia. (Also for some reason it includes a rules hack in the back of the book for playing as a party of five Sean Beans, which sure is a thing.)

Alternatively, if you’d prefer the exact opposite of that and would like to try a gentle slice of life comedy that just happens to star various D&D monsters, you might have a look at Golden Sky Stories. By default it’s about talking animals who can transform into human children; however, the Fantasy Friends supplement provides a rules hack for playing as miniature dragons, beholders, mimics and gelatinous cubes, among other possibilities – and yes, they can transform into children too! Any adventurers you meet here are going to be more misguided than antagonistic, and you “defeat” them by making friends.

If by “dragons” you mean you want to be a dragon specifically, there’s the old Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition campaign setting Council of the Wyrms. It’s another “you’re a monster with classes and levels” deal, this time incorporating a novel (for its time) dual-PC conceit whereby each player creates two characters: a dragon to deal with a big stuff, and a demihuman servant/valet to deal with the little stuff. The downside is that it’s not a standalone game (you need the 2E core books to play), and – like the first entry in this list – the rules definitely show their age.

In terms of forthcoming titles, you might also keep an eye on Wicked Ones (a dungeon-building Blades in the Dark hack due out some time in 2020, though an open playtest is currently available) or Let Thrones Beware (a game about monsters rebuilding civilisation following the apocalyptic collapse of a brutal human empire, likewise in open beta at the time of this posting).

#gaming#tabletop roleplaying#tabletop rpgs#tabletop rpg recommendations#violence mention#death mention#cannibalism mention#swearing#mistfather

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

So y'all already know that I love and ship smopkins right? The problem I have is that people keep telling me, "Wouldn't that be a toxic relationship? Wouldn't that be a bad or abusive relationship?" My ass wants to ask so many questions back to them.

- When do Gary and Jimmy's relationship begin? Sure, if it begins right after Happy Volts then it very well could be, but what if you wrote Jimmy and Gary remeeting as adults? When they have time to fully grow and develop into their own people. Many of the behaviors you have as a teenager don't carry on into adulthood because you become more reasonable and see "Ohhh this doesn't work."

- What are you basing your assumptions of Gary's behavior on? Rockstar made Gary a two dimensional hot take on the mentally ill friendless white boy. We don't know much of anything about who he really is aside from that narrative Rockstar tried to sell. We only saw how Gary responded in one situation, a situation written back in 2006 by people who did not grasp how mental illness worked or how to make a fully fleshed antagonist.

We don't know how Gary could respond to a romantic situation. We only see how he responds to people he views as " lesser backstabbers lying in wait." What if something or someone came around and challenged Gary's assumptions? Many anti-smopkins folks think they can predict Gary's behavior, but Rockstar threw that out the window when they made a kid who had only ADD,(as far as Rockstar tells us) and treated him him like a megalomaniac sociopath.

- Did you guys forget this is all happening in the realm of fanfiction and fanart or something? Rockstar may have been too preoccupied with making a whole game to fully develop Gary, but that doesn't mean the wonderful fanfic authors are. In the realm of fanfiction, we have A/B/O fic, Wingfic, demons and angels fics, and so many more that I can't even fathom them all. This is the realm where anything can happen so long as it's written well. So sure, you could have a fanfic author who explores just how toxic Smopkins can get (hint: Gary is rainbows and unicorns compared to some of my friends exes.) And there are other fanfic authors that describe the situations where Gary and Jimmy's relationship flourishes and does well. And all the many grey areas in-between exist within these fics.

- Oh and you never shipped something questionable? If you ship Trevor and Michael from GTA V, how are you any different than a smopkins shipper? (This isn't the only example but I wanted to keep it within Rockstar) Trevor has literally killed people, Micheal enjoys committing large robberies for fun. By the logic of anti-smopkins folks, these two are destined to have a toxic as fuck relationship. Hell, Rockstar explicitly makes it clear even their friendship is toxic, but does that stop the ship? Nope.

Gary and Jimmy look like a much better relationship in comparison. But, I'm not here to have a, "who's ship is more toxic", competition. I'm just saying that shipfics and fanart don't care about canon, circumstances, and any other information that would stop them. They all get either written out, circumvented, better developed, and just flat out ignored in the world of fandom. Authorial intent doesn't really mean shit anymore and that means that if people see romantic tension where the author didn't intend, then too bad there's romantic tension now.

- What real harm are they doing? By writing fanfiction and creating fanart about a game that is mostly forgotten and niche to begin with what harm does shipping smopkins really pose? This is just a hobby y'all, a harmless interest. Like the people who follow true crime, play violent video games, and watch horror films, sure these hobbies get judged by "more normal respectable people with respectable hobbies" but none of these hobbies harm anyone. So why don't y'all relax and let people like things without trying to shoot their enthusiasm down.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

stepping into a mirror

The other night I watched Paul Schrader’s film of The Comfort of Strangers for the first time. It is not a great film, though it is appealing in a lurid sort of way; it has a remarkable performance by Christopher Walken, and a beautiful soundtrack by Angelo Badalamenti. But the conclusion of the original novella by Ian McEwan has stuck in my mind since I first read it about fifteen years ago. After watching the film I read it again, and it seemed no less troubling, though if it were published today I think it would find a considerably tougher reception.

It’s not an especially deep story. About half of it reads like one of those classic dinner party anecdotes about having a dreadful time on holiday; the other half is a psychological thriller that owes more than a little to the format of a classic ghost story. Colin and Mary are a modern young couple who barely communicate, and mostly just tolerate one another. After getting lost one evening in search of dinner, they fall into the company of a local man, Robert, and his wife Caroline. Robert comes across as over-friendly in a way that puts one stereotype against another: English reserve versus flamboyant European over-familiarity, plus a certain latent homophobia on Colin’s part. But like all the best ghost stories, part of the appeal is the fact that everything which happens next seems slightly preposterous. It is insubstantial — not merely impressionistic, but actually vague — as if there were pieces missing throughout. It doesn’t quite add up.

Before watching the film I’d been reading The Husband Stitch by Carmen Maria Machado, a short story now published in her excellent collection Her Body and Other Parties. It too borrows the tropes of horror fiction to express something about gender relations, and though it’s openly self-conscious about it (breaking the fourth wall in the first paragraph) it is just as unsettling in its implications. Where McEwan’s prose unfolds at a languorous pace, the unusual style of the Machado story has a directly performative quality. It is actually written to be performed (‘If you read this story out loud, please use the following voices…’) but in full awareness that it won’t be. It knows the stage directions are only a kind of secret aside between narrator and reader.

This quality of implied monologue in The Husband Stitch makes it feel like something other than a conventional short story. Even when read silently it feels like something spoken, like the reader is being addressed personally. In some ways it feels like a lesson. Throughout, the author is marshalling her scenes like a general arranges their troops. Arguments are lined up as we wait for a skirmish that never quite comes. It is a steady trickle of discomfiting imagery, but over all of it hovers the voice of the narrator, confident and detached. Think of one of those great lecturers where every digression becomes woven back into the fabric of the thesis so that in the end it no longer seems like a diversion.

The story is based on the fairy tale of a woman with a velvet ribbon around her neck, whose head will fall off when the ribbon is untied. It is, as far as I can determine, an American middle-school standard that in recent years has taken on the spooky quality of urban legend. But here, the author twists and tugs it further into something like speculative fiction. The story imagines a world where some women are born with a ribbon around a place on their body, as if it were part of them. Nobody talks about how or why this happens. But when she marries, the green ribbon around the narrator’s neck becomes a distraction to her husband, and later to her infant son. As a metaphor it is almost too direct. They want to touch it, to play with it, but she won’t allow it — nor does she even think it an object worth discussing. ‘The ribbon is not a secret, it’s just mine,’ she says.

But it is not only a ribbon: it is a ribbon tied as a bow. A bow suggests promise. It is intended to be untied — in this case, by an author who has made it the centrepiece of the story. Buttons or stitches or a zipper would all suggest something different. What we have is a bow. And so part of the tragedy here comes from this idea of a character who is a prisoner of the expectations placed on her by the story. The reader knows that the ribbon must, at some stage, come apart. Drama demands it. Yet there’s no part of the narrator’s language which makes her seem like a victim. She is entirely in control of how the story is told. And it ends how it was always implied to end — with the husband undoing the ribbon. She allows it. But whether or not it is her choice is addressed in a few brief phrases:

‘Resolve runs out of me. I touch the ribbon. I look at the face of my husband, the beginning and end of his desires all etched there. He is not a bad man, and that, I realize suddenly, is the root of my hurt.’

I thought of this moment when, at the end of The Comfort of Strangers, Caroline explains how she got the injury that has made her a virtual recluse:

‘…[Robert] whispered he was going to kill me, but he’d said that many times before. He had his forearm around my neck, and then he began to push into the small of my back. At the same time he pulled my head backwards. I blacked out with the pain, but even before I went I remember thinking: it’s going to happen now. I can’t go back on it now. Of course, I wanted to be destroyed…’

Caroline’s longing for oblivion at the hands of her husband is emblematic of the darkest suggestion in McEwan’s story. This is the idea: that a certain level of violence between men and women is not only a defining part of human relations, it might even be thing that all parties secretly long for. Later, Mary describes it as ‘men’s ancient dreams of hurting and women’s of being hurt’. What makes it so troubling is that all this comes from Caroline, not from Robert. We would expect it from him: Robert is every inch the controlling, misogynist psychopath, trapped in a permanent preoccupation with the masculine archetypes of his father and grandfather. Caroline is unremarkable by comparison. The suggestion is not just that a violent character is the product of a violent upbringing, but that there’s some part of all of us which longs for it.

None of this has to be taken seriously. We could dismiss it as an authorial trick: placing an obviously repellent point of view in the mouth of a seemingly innocent character to make it seem almost plausible. This is what I meant when I said that The Comfort of Strangers would likely receive a hostile critical reception today: an author couldn’t write such a thing and expect these assumptions to go unquestioned. But there’s a good reason for that. Suddenly we’ve become accustomed again to hearing similar sentiments from people who (while they might not actually be calling enthusiastically for men to beat women) long for a return to a paradigm of gender relations that is exemplified by Robert’s persona in this story. What makes The Comfort of Strangers such an uncomfortable read is the narrative’s refusal to be drawn on whether we should actually believe any of it.

The only moments in McEwan’s story which read like a lesson are those in which Robert speaks at length about his father (‘All my life my father wore a moustache like this…and when it turned to grey he used a little brush to make it black, such as ladies use for their eyes. Mascara.’). These moments have the same performative quality as the tone of Machado’s story. They are equally honest, and demand the reader’s entire attention. They are also quite disturbing. One of the few things that the movie gets right is that Harold Pinter’s screenplay divides up, repeats and scatters Robert’s monologues throughout the film; combined with Walken’s strangely stilted reading, this gives them a mesmeric, incantatory quality. So often these strongmen characters assume the centre of attention in Pinter’s own work; perhaps the film allows Robert’s stories the same kind of self-importance they assume in Robert’s own mind.

‘Did she want it?’ is the only question worth asking that emerges from both stories. It becomes the basis for a sort of game that both authors play for our stimulation. In both, what keeps us reading is the same old familiar threat of an ultimate undoing. McEwan’s final twist is that it is Colin, not Mary, who is the victim. It’s not clear why Robert kills him; perhaps it is some sort of implied failure of masculine virtue, at least in Robert’s eyes. More important is that the story demands blood.

There is little in The Husband Stitch that could be mustered for an affirmative answer to that question. That the reader might still wonder about it is an indication of the sheer emotive force mustered in pursuit of it. To put it another way: she must have wanted it because the men in her life also wanted it so much. That her ultimate answer could be not ‘yes’ or ‘no’ but ‘I don’t care anymore’ is perhaps the worst outcome of all.

But however we feel about this order of things, the story leaves little room for the reader to imagine a different world. There is a certain orderliness in its vision: women bear their ribbons, secret or otherwise; men want to untie them. It is an order similar in its way to the patterns of violence expressed in The Comfort of Strangers. Men dream of hurt, women dream of being hurt. Amongst all this the whole question of who wants what and why becomes inextricably tangled. Perhaps this is how a bow becomes a knot.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A theory of fun - textbook

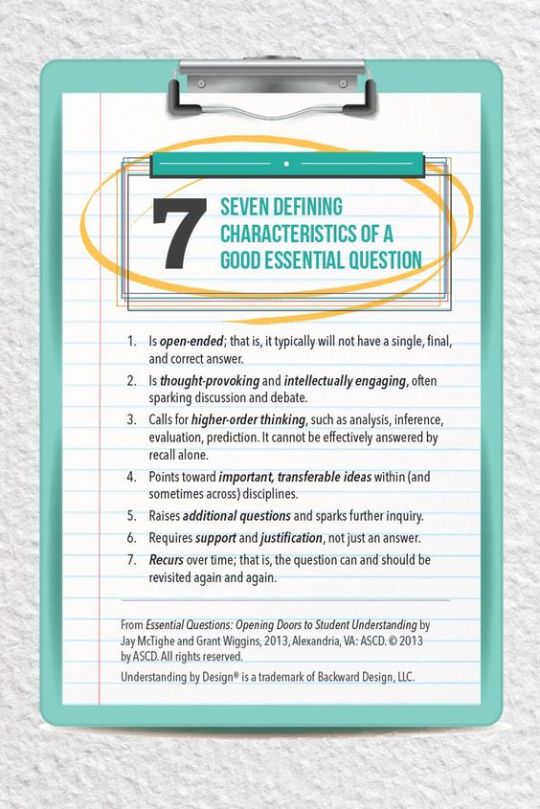

What are essential questions? Read the assigned chapter and compose an essential question based on the chapter, or use Honoria’s sample essential questions. In class, present a brief summary of the chapter, ask the class your essential question and lead a discussion on the topic. Prepare follow up questions on the topic to faciltate the discussion with 2 different contributing students.

Theory of Fun (2nd edition) Raph Koster

Game Design 2 - Theory of Fun from Jay Crossler

Chapter 1 Why write this book?

How has your experience of fun and learning changed over time and levels of maturity?

Contrast how you have experienced the same game at different ages.

As a popular game ages, what kinds of changes are made to new versions?

Chapter 2 How the Brain Works

Start with the definitions of games on page 14. Develop your own definition,

Describe one of the patterns in a game or games that you enjoy, or are really good at.

Chapter 3 What Games Are

Describe what you find fun about your favorite game.

Analyze 2 things that ruin the fun in a game you don’t enjoy.

Describe your favorite challenge in all of your game-playing history. (How old were you? Why is it your favorite challenge? How did you succeed or fail at this challenge?)

Chapter 4 What Games Teach Us

Describe the “possibility space” (page 56) of a game you have played in the last year.

Many games encourage “othering” the opponent (page 68). What kinds of stories and games can we design based on insights into how the modern world works?

Chapter 5 What Game Aren’t

Describe the game system and the story of a game you like. Why does that combination of system and story satisfy? Check out page 88 for some descriptions of game sytems in relation to game stories.

Koster defines fun as “the feedback the brain gives us when we are absorbing patterns for learning purposes.” (page 96) Koster describes why school is not thought of as fun. Describe a memory in which learning academic material was fun.

Page 100 lists resasons other than fun to play a game with a system: practice, meditation, storytelling, and comfort. Describe your experience with one of these other reasons for playing a game.

Chapter 6 Different Fun for Different Folks

Psychologist Howard Gardner developed a theory of multiple intelligences

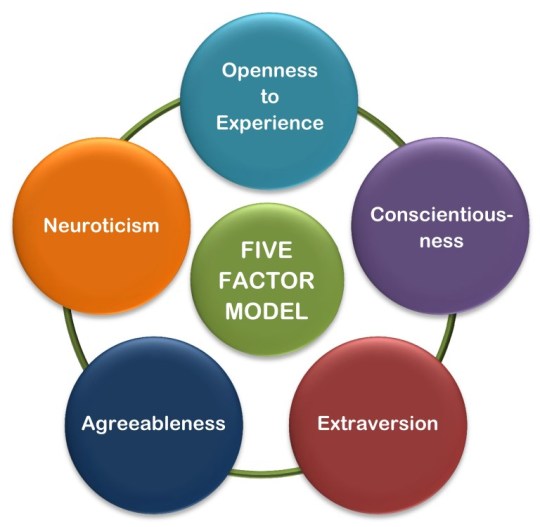

In addition Koster mentions the Five Factor Model

On page 106 Koster poses the question. . .

What does this all mean for game designers? Not only will a given game be unlikely to appeal to everyone, but it is probably impossible for it to do so. The difficulty ramp is almost certain to be wrong for many people and the basic prmises are likely to be uninteresting or too difficult for large segments of the population.

How can designers use empathy for their target audience to best design a game that can potentiate a “change in the culture ... towards greater equality . . . and teaching alternate ways of thinking.” (page 108)

Chapter 7 The Problem with Learning

On page 120 Koster states

(Games) teach us things so that we can minimize risk and know what choices to make. Phrased in another way, the destiny of games is to become boring, not to be fun. Those of us who want games to be fun are fighting a losing battle against the human brain because fun is a process and routine is its destination.

In the end, (it’s) both the glory of learning and its fundamental problem, once you learn something, it’s over. You don’t get to learn it again. (page 128)

Based on your own experience can you describe a game that was really fun and become boring?

How and why did that shift in enjoyment happen?

How can your experience apply to your creative career in the entertainment industries?

Chapter 8 The Problem with People

On page 134 Koster ponders:

Sticking with one solution is not a survival trait anymore. The world is changing very fast, and we interact with more kinds of people than ever before. The real value now lies in a wide range of experience and in understanding a wide range of points of view. Closed mindedness is actively dangerous to society because it leads to misapprehension. And misapprehension leads to misunderstanding, which leads to offense, which leads to violence.

Consider the hypothetical case where every player of an online role-playing game gets exactly two characters: one male and one female. Would the world be more or less sexist as a result?

What do you think about Koster’s 2 character game question?

On page 140 Koster observes:

The most creative and fertile game designers working today tend to be the ones who make a point of NOT focusion too much on other games for inspiration.

What other sources have you noticed in current games?

What other sources of inspiration can be the basis for a game?

What other discipline can you study that might enhance your game design potential?

TIP Research a discipline such as games inspired by art history.

Chapter 9 Games in Context

Koster observes a number of contexts in which we experience games.

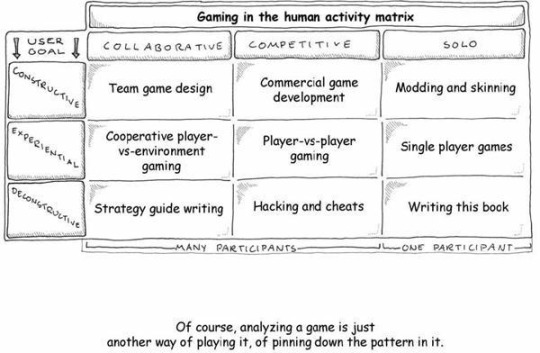

Alone or with others

Any given activity can be performed either by yourself or with others. If you are doing it with others, you can be working either with or against each other. I call these three approaches collaborative, competitive, and solo. (page 142 and 143)

Levels of game interaction

Some forms of interaction are constructive (modding a game), experiential (playing a game) or deconstructive (hacking a game). (page 144)

Koster defines ways in which games can become art.

Mere entertainment becomes art when the communicative element in the work is either novel or exceptionally well done. It really is that simple. The work has the power to alter how people perceive the world around them. (page 150)

Since games are closed formal systems, that might mean that games can never be art . . . But. . .I think . . .we need to decide what we want to say with a given game -- something big, something complex, something open to interpretation, something where there is no single right answer -- and then make sure the player interacts with it, she can come to it again and reveal whole new aspects to the challenge presented. (page 150)

The game would be:

thought provoking

reveletory

contribute to the betterment of society

force us to reexamine assumptions

give us different experiences each time

allow each of us to approach it in our own way

forgive misinterpretations

would not dictate

would immerse and change a worldview (page 152)

After comparing game design to other artforms Koster concludes:

The designer who wants to use game system design as an expressiver medium must be like the painter and the musician and the writer, in that she must learn what the strengths of the medium are, and what messages are best conveyed by it. (page 162)

What games do you think of as art? What do your chosen art games have in common with specific examples of painting, sculpture, theatre, dance, literature, film, or music.

How can you use Koster’s definition of art on page 148 So what is art?. . . to design games for powerful self-expression and communication?

Chapter 10 The Ethics of Entertainment

Visual representation and metaphor are part of the vocabulary of games. When we describe a game, we almost never do so in terms of the formal abstract system alone; we describe it in terms of the overall experience. (page 166)

The problematic case is a game that contains both brilliant gameplay and offensive content. (page 174)

In this chapter Koster continues to compare games to other art forms such as literature and film and suggests that the lessons learned in those storytelling media can form a constructive lesson for the art of storytelling in games.

Think of an ethically problematic story or character in your game play experience. How would you change that problematic storyline or stereotypical character in order to align with your values?

Chapter 11 Where Games Should Go

. . .other humans have typically been our greatest predator. Today we have come to realize how interrelated we all are, even when the left continent doesn’t know what the right continent is doing. We have come to realize that actions we undertake often have far-reaching consequences that we never anticipated. (page 176)

But, while we’re bemoaning the lack of maturity in the field, we need not to miss the forest for the trees. Too much sex and violence isn’t the problem. The problem is shallow sex and violence. (page 180)

What are the merits of Koster’s argument when he recommends:

We should fix the fact tht the average cartoon does a better job at portraying the human condition thatn our games do. (page 180)

Ideate ethical and exciting victory conditions for a game that you would like to see in the world.

Chapter 12 Taking Their Rightful Place

Koster’s call to action:

It’s time for games to move on from only teaching patterns about territory, aiming, timing, and the rest. These subjects aren’t the preeminent challenges of our day. (page 188)

- Games do need to present us with problems and patterns that do not have one solution, because those are the problems that deepen our understanding of ourselves.

- Games need to be created with formal systems that have authorial intent.

- Games need to wrestle with issues of social responsibility.

- Games need to develop a critical vocabulary so that understanding of our field can be shared.

- Games need to push the boundaries. (page 192)

Pick one of the calls to action and do some research on the topic. 1. Explore arguments both for and against Koster’s calls to action. 2. State your own opinion on the subject with your own supporting arguments.

0 notes

Note

Yakov and Yuuri's conversation in chap 14 of umfb for the DVD commentary game

Yakov Feltsman looked older than Yuuri remembered, the lines of his skin worn in more deeply than the last time they had been face to face. Yuuri took a step back instinctively. Memories of their last meeting were still burned into his mind, the hateful words that the man had thrown at him so viciously even if he didn’t understand the reasoning behind them. Yakov seemed to notice how Yuuri tensed, curling in on himself defensively and he took a step back, giving Yuuri space, face still unreadable.

“Katsuki.” he started then stopped, seeming to consider for a moment. “Yuuri.” he tried again and Yuuri’s could feel his eyes widen a little at the sound of his name. He was still on the defensive but Yakov didn’t seem to be trying to hurt him again and the instincts that were screaming at him to run quietened a bit at the realisation.

“Can I speak with you?” Yakov asked and Yuuri nodded hesitantly, wanting to decline but at the same time curious as to what the older man had to say. Yakov looked tired and while it could be something to do with coaching his, apparently difficult, youngest student though his senior debut, somehow Yuuri didn’t think that that was the whole story.

“I’m sorry.” Yakov began and it surprised Yuuri even though he knew that he should have been expecting it. Celestino had told him that Yakov had apologised, both publicly and privately, if indirectly through Celestino. But in Yuuri’s head, Yakov was still the furious man who had walked in on he and Viktor and spat words like poison and then proceeded to ruin everything.

“I misjudged you.” Yakov continued, looking sombre. “I thought…well, it doesn’t really matter what I thought. I misjudged you and I apologise for that. And I’m not asking you to forgive me. But please don’t take it out on him.”

Yuuri felt his heart clench a little at the words because that hadn’t been what he had been doing, that had never been his intention. He had stayed away because he needed to, not to be deliberately cruel, not to hurt. But Yakov’s eyes were pleading and he was frozen, the words stuck in his throat because suddenly none of them seemed like an adequate enough justification to explain.

“He tried to stop me, he was trying to protect you.” Yakov told Yuuri and there was a blunt honesty to his voice, his words undeniable. “He made a mistake I know and I’m not trying to force you to forgive him. But these last few months…what happened then…it destroyed him. So please, talk to him. I’m not asking for any more than that but please just talk to him, even if it’s for the last time. Not for me. For Vitya.

“I will.” Yuuri managed to choke out because he had been intending to anyway but he wasn’t sure if Yakov would believe him if he said it.

Yakov nodded slowly, looking relieved even if the tired lines were still engraved deep into his face. “Good.” he said quietly before turning away, leaving Yuuri alone again with his thoughts.

So this conversation came about partly because I wanted to give some idea of what Viktor was going through in the months that Yuuri was gone and partly because I wanted to dispel the notion that Yakov had deliberately tried to sabotage Yuuri or his and Viktor’s relationship and was a terrible person. He made a terrible mistake sure and the way he approached Yuuri originally was completely wrong and damaging but he genuinely thought that Yuuri broke the rules and reported that to the proper authorities. He shouldn’t have treated Yuuri the way he did by any means but a lot of people in the comments of chapter 13 were talking about how they thought Yakov secretly leaked the information and was deliberately sabotaging Yuuri and I wanted to show that he didn’t and he actually really regretted what had happened and knows that he doesn’t deserve to be able to ask Yuuri’s forgiveness for it. Yakov wasn’t the villain of the story or a bad person, he (just like everyone else) was a person who made some bad choices and allowed assumptions and his own personal bias blind him.

Yakov here initially approaches Yuuri to apologise and also because he’s desperate to help Viktor. He’s already apologised to Yuuri publicly and through Celestino but he wants to do it again in person. But a big motivating factor behind why he goes to Yuuri at that point is he’s watched what happened destroy Viktor and watched him spiraling with no way to help and he knows that Viktor needs closure before he can really move on. He assumes that, after months of silence and what happened, it’s very unlikely that Yuuri will take Viktor back again (another one of his great regrets) and that it’s not his place to ask Yuuri to do that but he knows that having no word from Yuuri has left Viktor in a terrible limbo where he’s torn between hoping and trying to move on. Yakov knows that, for both their sakes, they need to at least have one last conversation to clear up where they stand with each other, even if Yuuri never wants to speak to Viktor again after it.

So he approaches Yuuri, tries to talk to him, sees how uncomfortable Yuuri is around him (and mentally berates himself for being solely responsible for that) and tries to start the conversation in a way that makes Yuuri more comfortable and gives him the option to refuse. Then he goes straight to apologising because that’s the most important thing and he was yet to do it in person. He also starts to try and explain why he acted the way he did and his misconceptions about Yuuri’s character but cuts himself off because he realises it’ll just sound like he was trying to excuse himself and his actions rather than acknowledging the blame and that’s not what he was trying to do at all (also on an authorial level it was because I was enjoying watching people guess what those misconceptions were before I wrote the companion fic and revealed them).

After that, he moves onto Viktor because he’s not trying to seek forgiveness for himself but help Viktor in the last way that he can think of. He’s just spent nine months of watching someone he’s basically raised and considers a son suffer for his own mistakes and it’s been torture for him. He just wants to see Viktor happy again and the ‘but please don’t take it out on him’ is because he wants Yuuri to know the full blame should lie with him not Viktor and the radio silence from Yuuri is acting like a punishment for Viktor (obviously Yuuri never intended this or saw it that way, he just needed space, but it was difficult for Viktor all the same).

Yakov isn’t sure how much Yuuri knows about Viktor’s role in everything or how he was trying to stop Yakov and protect Yuuri so he wants to make that clear in the vain hope that maybe if Yuuri didn’t know, it might change his mind about never speaking to Viktor again (as that’s what it looks like he’s currently intending to do from an outside perspective). Yakov also acknowledges after how much Yuuri got hurt his isn’t obligated to forgive Viktor and he knows logically that from how Yuuri has acted it’s probably the end for them but he tries to appeal to Yuuri’s emotional side and any feelings for Viktor he might have left (’But these last few months…what happened then…it destroyed him’ / ‘not for me, for Vitya’) to get him to give Viktor closure. He knows that even if Yuuri breaks up with Viktor, it’ll be better than Viktor always wondering and having that last spark of futile hope meaning he’s never able to really accept and move on.

Yakov knows at this point that Yuuri definitely had feelings for Viktor, most likely loved him or at least deeply cared for him, and he’s appealing to that in the hope of helping Viktor in any way he can. From how Yuuri has refused contact with Viktor for nine months, Yakov’s pretty sure Yuuri has ended their relationship and is intending never to contact Viktor again and pleading with him to have one last conversation is the only thing he has left to do to try and help Viktor move on. And deep down, he’s also hoping that maybe he’s wrong and if they just talk again Yuuri might be willing to begin to forgive Viktor and let them try again. Either way, he just wants to try and begin to help Viktor heal and be happy again.

In the context of the fic, the conversation was to give Yakov some humanity and background aside from just ‘person who screwed everything up’ and also to show people that what happened completely ruined Viktor since at that point, there was no companion fic where they could read it for themselves. It was also a little to confirm that Viktor had no actual part in reporting Yuuri and actually actively fought against it because after chapter 13 a lot of people assumed he was the one who did it rather than trying to protect Yuuri which was what actually happened.

[DVD COMMENTARY ASKBOX GAME]

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

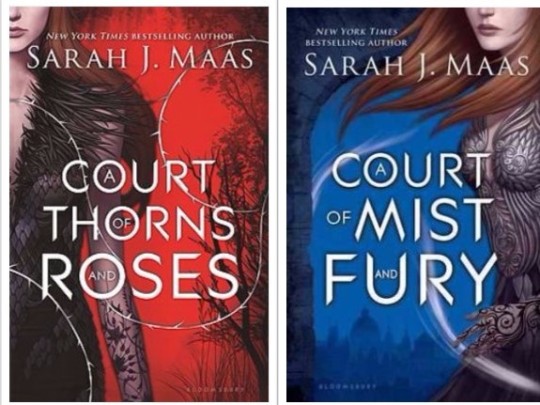

The relationship between misogyny and romance: a SJM study

Why female desire* isn’t problematic, but A Court of Thorns and Roses is.

In which I wade into an issue in depth, praying that the flame war gods do not strike me down.

**Please note that this essay discusses only the misogynist elements of SJM’s writing in the ACOTAR series. There are obviously other problematic elements that require acknowledgement, but this is the one I feel confident in addressing. I haven’t read any of ACOWAR yet.**

*also, female desire in this instance refers to the desire of the presumed female reader of romance. The reading of romance and YA is obviously not exclusive to women, although a lot of the assumptions of SJM’s work ascribe to the concept of a binary gender.

Recently (or perhaps it’s always been there, and has only recently wandered onto my dash) I’ve seen a lot of discussion of the problematic nature of Sarah J. Maas’ writing. This is an issue I have thought about a lot, because although I absolutely hate the Throne of Glass series with a passion, on account of what I feel is bad writing, poor plotting and awful treatment of non-heterosexual non-white people, for some reason this hatred does not extend to ACOTAR and ACOMAF, which I read and really enjoyed, despite much of the content - and the issues of diversity and misogyny - being consistent across both.

I soon realised that this difference of opinion lies in the genre distinctions I make between the two. While Throne of Glass was initially marketed as a YA high fantasy book (I never got past the second, so I can’t speak for the later books), ACOTAR was sold to me as essentially a romance novel, or at least a paranormal romance. While I ask for diverse representation and good feminism from my fantasy reading, it seems that I consider escapist fantasy, misogyny and sexism to be all part and parcel of romance.

In fact, when you examine ACOTAR and ACOMAF’s problematic gender portrayal (as I am about to), you realise that a lot of Maas’ problematic tropes - traditional alpha male behaviour, such as possessiveness and animalistically coded desire, issues of iffy (and in cases utterly absent) consent, reinforced heterosexuality - are typical to a majority of the romance genre.

‘Alpha Males’ in Romance

The question of whether ‘alpha male’ behaviour is problematic and should be called out isn’t unique to SJM’s writing (although, in her case, you could perhaps refer to it as ‘fae male’ behaviour). It has been levelled at the whole of the romance genre, in particular paranormal romances and ‘bodice rippers’, for a long time.

The problem with outright condemning it lies in the paradox of the romance genre itself. On the one hand, romance is written by and aimed almost exclusively at women – it is the genre where female desire, which is often suppressed or demonised in society and popular media, can be freely indulged and explored. Women are writing these kinds of relationships, and other women are buying them, so clearly some kind of female desire is being acknowledged and explored, whereas before it would’ve been suppressed or even punished. On the other hand, it often tends to be explored in some quite squicky ways. Because romance has roots in the Byronic heroes of Mr. Darcy, Mr. Rochester and (for a reason I still cannot fathom) Heathcliffe, they often feature domineering, rude, taciturn and belligerent male love interests who are critical and sometimes cruel to the heroine. And, in the paranormal romance genres, and new adult literature in particular, this has morphed into a more sinister figure, the possessive, aggressive ‘alpha’ male.

Feminist critics have constantly been trying to decide whether romance literature is feminist or misogynist. Most would say that women should be allowed to enjoy sex and indulge in whatever fantasies they wish to, when the female desire has been policed, demonised and made a taboo for so long. On the other hand, a lot of romance literature focuses on fantasies which have their basis in some very heteronormative and sexist concepts. This raises a question: do women (or the presumed femme coded reader) enjoy them because they enjoy them, or because this is what society has told them to enjoy? Is the romance genre actually just reproducing and perpetuating this harmful societal influence, rather than promoting sexual agency?

This is why when I criticise the misogyny in her writing (and specifically misogyny, diversity is another matter), I criticise SJM and her authorial intent, rather than her readers, because I’m not going to tell people what they should and shouldn’t find enjoyable or sexy in a romance novel. But it is also why people should be willing to see the problematic elements of her writing, because otherwise the harmful sexist ideals it is based in just get thoughtlessly perpetuated. People should be willing to discriminate between what is explicitly a fantasy, and what is outright abuse.

Sexual fantasy vs. abuse

An example in book is the difference between the ‘napkin’ dress scenes in ACOTAR and ACOMAF. In ACOTAR, Feyre is ‘dressed’ and painted against her will, she is humiliated and made into an exhibition involuntarily.

‘They stripped me naked, bathed me roughly, and then - to my horror - began to paint my body [...] the two High Fae ignored my demands to be clothed in something else [...] but held my hands firm when I tried to rip the shift off’ (ACOTAR, p.254)

What follows is a party where Rhys forces her to drink what is essentially drugged wine, and then she dances for him, in a scene that is analogous to date rape. She blacks out and wakes up with only the smudged lines on her body to tell her what she has done, or rather, what has been done to her. Her agency is ripped away from her.

“What happened?”[...] “I don’t think you want to know.” I studied the few smudges on my waist, marks that looked like hands had held me. “Who did that to me?” I asked quietly.’ (ACOTAR, p.259)

To compare, in ACOMAF, Feyre consents to being dressed in order to enter the Court of Nightmares, and willing enters into an exhibitionist scene with Rhys (if under very flimsy plot purposes).

‘I leaned a bit more against him, my legs widening ever so slightly. Why’d you stop? [...] I became the music, and the drums, and the wild, dark thing in the High Lord’s arms.” (ACOMAF, p.414)

‘We were his distraction [...] You and I put on a good show, I said’ (p.415)

This time, the scene is enacted with consent - in fact, her and Rhysand have discussed their actions beforehand and established limits: ‘he’d apologised in advance for it - for this game, these roles we’d have to play’ (p.410). Feyre is the one who makes a choice, she initiates sexual contact, she is sober and has full agency, even when it does not seem that way to their audience.

The latter scene in ACOMAF is, arguably, a dominance fantasy that is carried out with the consent of both parties (three, if you include a reader indulging in the same fantasy). The first isn’t, it is abuse, but somehow it gets painted retrospectively with the same brush.

There is nothing innately wrong in engaging in dominance fantasies, or enjoying a book which perpetuates one. You could even take enjoyment in the ACOTAR version of the dress sequence, if you, as a reader, consent to indulge in it. But please understand, that that is the *reader* who is making that decision, whereas SJM is forcing it on all readers and, in universe, on Feyre.

Why this is problematic: it is not wrong for a reader to feel desire, but an author orchestrates the route that desire takes

The reader can choose to engage in a fantasy (and in this case the word is not explicitly sexual, it can also refer to the escapist elements of ACOTAR, or the romantic nature of Feysand’s relationship), either in spite of the problematic elements or in ignorance of them, and not necessarily be culpable. But it is important to note that, if the reader does accept this in ignorance, it is an ignorance which SJM contributes to, because she normalises problematic behaviours that have become ingrained in society, and also in the culture of heteronormative romance. Rhysand is never called out for the non-consensual public humiliation and things he forced Feyre to do in the first book. It is in fact retrospectively romanticised and made into an act of love:

‘“So we endured it. I made you dress like that so Amarantha wouldn’t suspect, and made you drink the wine so you would not remember the nightly horrors in that mountain [...] I was jealous.” (ACOMAF, p.525)

The repetition of ‘I made’ acknowledges that this behaviour was non-consensual. But all that’s offered is a weak excuse about how it was done as a way of him processing and dealing with his emotions, and it is explained that the act actually protected Feyre (bleugh). Rhysand even admits that he was doing it to ‘get back at Tamlin’ (p.542), reducing Feyre to a territory that is fought over by the two men, something which is never interrogated further - and will no doubt be perpetuated by the plot of ACOWAR.

And this is what ultimately makes me uncomfortable with SJM’s books: not that they have these elements of domination, but that the more sinister aspects are never questioned or challenged. Through the thin and very flimsy plot trickery of ACOMAF, Rhysand is made into a saint, his previous sexual assault explained away, becoming something done to Feyre out of love and for her own good.

And regardless of how you feel about Rhysand as a character, or the quality of his redemption arc, you have to admit that this is particular incident is part of a much more insidious theme in SJM’s writing, where all sexual violence and domineering behaviour becomes normalised to a point where they are explicitly attributed to the innate nature of masculine desire, and of masculinity itself. Rhysand was confused in ACOTAR, he needed to get close to and protect Feyre because of the incipient mating bond, so he has to ‘help’ her without her consent. Tamlin will act aggressively feral when initiating sexual contact, because that’s part of his essential nature as a fae male and a shape shifter. Even though this behaviour is called out in Tamlin, a) it is not done so in the book where it happens, meaning that a reader of ACOTAR alone could see it as an acceptable form of sexual interaction, and b) the connection of this behaviour to his innate nature as a male is never problematised or challenged. Tamlin’s possession and dominance is a ‘wrong’ version of natural fae male behaviour, but this behaviour is still upheld as an ideal. Because what Tamlin does is not that different from how a fae male acts under a mating bond - it’s just that he and Feyre are not mates.

Don’t believe me? Rhysand acts just as possessive and domineering as Tamlin, it’s just that he has the ‘right’ to be, as Feyre’s true mate, under a perfectly natural force he ‘cannot control’...

‘“It’s normal [...] When a couple accepts the mating bond, it’s...overwhelming. Again, harkening back to the beasts we once were. Probably something about ensuring the female was impregnated...males get so volatile that it can be dangerous for them to be in public anyway.” (ACOMAF, p.541)

There is *so much wrong* with this entire concept - for one thing, ascribing biological imperatives to desire and romance is heteronormative as fuck - but the main issue is the way that toxic, violent and ‘volatile’ masculinity is made entirely natural - ingrained into fae males from the beginning of time when they were ‘beasts’. It’s telling that the words ‘beasts’ is used, because it seems that, in the world of this book, men are animals where sex is concerned - another utterly toxic image of masculinity. And this utterly ‘normal’ behaviour is never challenged: Feyre accepts that she is in close proximity to a ‘dangerous’ man without question. Rhysand can’t help being possessive, because he’s mated to Feyre, whereas Tamlin’s possessiveness was bad because he didn’t have the right to be. Why doesn’t Feyre get as violently possessive as Rhys does when their mating bond holds? As far as I can tell, it’s cause she’s a woman, just waiting to get ‘impregnated’.

There is very little difference between this passage and the behaviour that Tamlin has portrayed in ACOMAF to make him become the villain of the piece: dominance, jealousy, possessiveness, a desire to place Feyre in a traditionally feminine role of wife and mother. Yes, Rhys is ‘nicer’ to Feyre than Tamlin is in ACOMAF, but that is arguably an act of clear author intentionality, designed to rewrite his character, and utterly inconsistent with his possessive and sexual actions in ACOTAR. And more importantly, the link between masculinity, sex, and domineering violence remains firmly in place.

Masculinity and dominance are inextricably linked in the ACOTAR series, and this link is never challenged. In both the arc of ACOTAR and ACOMAF masculine dominance is held up as an ideal - even if the ideal of Tamlin is later dismantled to be replaced by Rhys, Rhys’ domineering characteristics are still disassociated from Tamlin’s ‘bad’ example and held up as a positive trait. Furthermore, it is only ever men who are domineering and possessive, unless you count Amarantha, and Ianthe, whose attempts at dominating seduction are always utterly demonised as wrong and intrusive.

‘She’d hounded him relentlessly - stalked the other males, too. [...] She’d be a problem - now or later. He knew it. Kill her now, end the threat before it began, face the wrath of the other High Priestesses, or...see what happened.’ (Ianthe seducing Rhys in ACOMAF, p.233)

Don’t get me wrong, all situations are examples sexual assault - but only the ones perpetuated by women are called out and condemned, and in both cases this is explicitly tied to their bids for power. How many times has ‘stalking’ been used positively in reference to Rhysand’s sexiness? Here, when a woman ‘stalks’, it is seen as wrong. Even if these characters are legitimately evil in-universe (no one is trying to redeem Amarantha), you cannot ignore a trend within the series where male dominance and possessiveness (in the case of Rhys) is excused and actually conceived as the ‘ideal’ relationship, and the same predatory characteristics are coded as villainous and unnatural when presented in women. That is contributing to an offensive and toxic conception of gender, masculinity in particular, and of heterosexual relationships (or, in SJM’s writing, relationships, given that non-het relationships have - at the point of writing - never been explored).

This is also why SJM needs to be called out on her misogyny (among other awful things), regardless of whether you enjoy her books or not. Because she normalises these behaviours, and people will think they’re normal if we don’t decry them. While I actually have no issue with sex being in books aimed at young people (hell, this was kind of the only way young me learnt about these things), I do take issue with representing toxic relationship dynamics as the norm OR THE IDEAL to younger readers, who are unlikely to be certain about what they want or should expect from relationships. She normalises an incredibly sexist dynamic that has men universally characterised as possessive, violent and dominating, and women as passive objects to be fought over. In the case of Feysand, this is repainted in ACOMAF as a narrative of undying and ‘true’ love. Even if you enjoy the books, you *cannot* ignore these implications.

#anti-sjm#essay#critique#emma writes about things#i like talking about books#please don't kill me#this is how I celebrate the ACOWAr release apparently#and yes I do actually like these books#but come on this shit is just weird#anti acotar#anti acomaf#heteronormativity#toxic masculinity

994 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curatorial Reflection, 26-11-2018

During the past couple of weeks we have been learning about curation and the curatorial practice. In order to enhance our own understanding of the curatorial project we are undertaking, we have read some insightful literature on the act of curating. They have attended to several different figures in the field of the curatorial practice: the curator, the audience, the cultural object and the attitude. Below are some findings that we ought helpful to enhance our own curatorial mission and vision.

The curator: Mieke Bal on Framing

In chapter four of Mieke Bal’s book Travelling Concepts in the Humanities, we are familiarized with the concept of framing. Bal, being both a scholar and an artist herself, investigates the practice of cultural analysis. Within this chapter she does so by guiding the reader through the process in which she curated the presentation of a painting herself, in the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam. By elaborately describing this case study, this chapter delivers some useful firsthand insights on the process curating.

Bal prefers the act of framing over providing context. ‘Framing questions the object-status of the objects studies in the cultural disciplines.’[1] The object is seen as a living thing, that changes over time. Framing is therefore a dynamic act, where providing context is static, often used for explaining instead of interpreting.[2] She argues that [art] theory and [museum] practice are unmistakably connected, but they are not one and the same. In fact, they have a troubled relation; A lot of curators bear assumptions in mind (for example, that their research must be historical, and that the outcome of their research must be visible for audience) that are interfering with their museum practice.

She goes on to lay bare six set-ups (frames) that she encountered in Rotterdam before having started curating in the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum. Bal emphasizes that these set-ups are not necessarily bad; they might turn out to be helpful. They indicate some of the frames we might encounter ourselves:

· She was approached by the Museum for her knowledge on the painting: the Museum assumed her to do a thematic presentation on it.

· She had her own assumptions on the meaning of the painting.

· She had to work with the museum’s curator, someone with their own frames.

· She ought to present the painting with (limited) means to use: the collection of the museum, and a financial budget.

· The artist of the painting wasn’t very well known: this meant that two common forms of exhibiting would both not be helpful. A monographic exhibition was simply not possible due to a lack of work by the artist, and the exhibiting of the time period in which the painting falls would wrong the value of the painting.

When setting up an exhibition room, every executive act is one of framing. The role of captions accompanying the cultural objects, for example, cannot be underestimated. They provide audience with (limited) guidance on how to view the objects.

During our own curatorial enterprise, we are to keep in mind that we as framers are framed ourselves. The same goes for the events we are visiting. It is up to us to discern these frames, thereby uncovering their attached meaning and consciously involve them in our practice. The framer being framed is not a bad thing, but it is up to us to become aware of the frames we are working with.

The audience: Claire Bishop on Viewers as Producers

In the introduction to the book Participation, Claire Bishop touches upon the changing role of the audience colliding with the emergence of participatory art. This art form requires the physical engagement of its viewers. Participation is often linked with political commitment: In the 1960s the prevailing belief was that physical engagement is necessary to create social change. Bishop puts three recurring reasons for participation forward:

· Activation – artists desire their subject (the viewer) to feel empowered by the act of participation, hopefully leading them to become active in determining their own [social and political] reality as well. Participation in this sense provides a conscious sense of agency to the audience.

· Authorship – It is ought to be more democratic and egalitarian to hand some of the authorial control to viewers, leading to a ‘more positive and non-hierarchical social model’.[3]

· Community – Due to capitalism, there is a ‘perceived crisis in community and collective responsibility.’[4] The society of the spectacle has made us egocentric individuals. Participatory art can help in restoring the social bond through its audience collectively creating meaning.