#because depending on how you interpret it it either supports or contradicts this philosophy

Text

there's an interesting statement being made about identity if you accept all of the wolf 359 characters are equally themselves as of the finale: eiffel is form without memory; hera is memory without form; lovelace is both, but without continuity of experience; minkowski is both with continuity - and she's still not the same person that goddard recruited. if we're never the same people we were, but we're always ourselves, then the only way the self can be defined is through its own assertion - and maybe it can be argued that "my name is-" (and later, being able to say "my name is hera" reintroducing herself to pryce) and "i am captain isabel lovelace. no matter how hard you try, you are not taking that away from me" and "without me, who are you?" / "renée minkowski, and that is more than enough to kick your ass" are all the set up for (and part of the answer to) "am i still doug eiffel?"

#wolf 359#w359#it's about accountability but also about inevitable change and the willingness to learn from the past#and change for the better#holding those maybe contradictory ideas in your head#that we can't escape who we are. the limitations of the self or the people we've been in the past. but also#that there's no permanent state of self we're bound to#that the self is a constant negotiation of presentation and communication with others and can't exist in a vacuum#but also that it is about inherent worth and self-defined and self-named#i think that line is so interesting. 'we can't just change who we are but we get better.'#because depending on how you interpret it it either supports or contradicts this philosophy#and i think the difference in how hera interpreted it vs how maxwell might've meant it is part of how they misunderstood each other#and why it's an idea that stuck with hera and that she returns to. and feels like it was a lie. after maxwell betrays her#but that's another discussion maybe.#and also of course. the significance of names in wolf 359. but that's a whole thing on its own too.

490 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you further elaborate about how eren's manipulation of historia reminds you of ymir and the first fritz king? Since that historia didn't tell anyone of eren's plan as you said.

Sure! This could of course be complete bs, but here is my interpretation:

When I first read 122 I have asked myself: Why didn't Ymir rebel against the King? Why did she obey? (Just like now everyone wonders why Historia obeys Eren).

Why did Ymir save the King's life? Because she loved him? Not in a lifetime. But she was so powerful with the power of the titans, she could have freed herself without any problems.

Is it a plothole? No.

I think Ymir had the mindset of taking everything on her shoulders, this is why she also probably took the guilt of letting out the pigs (if it wasn't her). I'm sure she had low self esteem. She grew up as slave, probably doesn't know a different life. The King even told her: "Rise. Work. That is why you have been born. Ymir my slave".

I can imagine this is not the first time he told her that. And if you keep telling this a person with low self esteem they start to believe it, especially if you don't have any friends to tell you otherwise.

For an independent and healthy person it's hard to grasp, why she didn't defy, but it also happens in our modern world all the time, especially in toxic relationships and I know irl examples myself. I think it's usually like:

1) Keep telling her how bad she is and taking away her value as human being, taking away her free will, so she is confused. At best isolating from other people. If she has low self esteem it works even better. That's what King Fritz did by treating her like a slave.

2) At the same time making her dependent on him, making her believe she is indebted to him. In Ymir's case I'm not sure why she felt intebted to him because their "relationship" is not very elaborated, he probably kept telling her "You are MY slave" and she lived by that, maybe telling her it was an honour to be the mother of his children, he literally said this was a reward. So this line can be used to make her believe to be grateful for that and show this gratitude by serving him. Maybe even threatened her so she was scared of him.

3) Telling her to obey and she does. Not because she agrees, but because she is already emotionally abused, confused and afraid of him. Manipulated. At the same time, you always see Ymir's depressed look.

Now let's move on to Eren and Historia. The manipulation is not as cruel as it was with Ymir, but it is way more subtle. But you see the same pattern:

1) He told her she is the worst girl in the world. It sounds even more convincing because she once said it herself down in the cave, and he uses these words here to confuse her, put them into another context and make her believe she is an evil person (whereas she is actually NOT imo, this lie is a form of taking away her value). Now this is only my interpretation and the EH shippers would say otherwise, but I don't believe Historia is an evil, selfish bitch, she just stated these words in the cave without thinking and even said it didn't mean anything later in uprising. She is not the Krista goddess either, she is just a person with strengths and weaknesses, but with a good heart. Her official stats still say Altruism 10/10 and she leads the orphanage OUT OF FREE WILL and with passion to save kids. She even said she will save anyone who feels lost. Is that what an evil person does?

Her whole life was also slave-like though, she was forced to hide her identity, forced how to live, so imo she already had low self esteem and was easier to emotionally attack. This probably got worse when Freckles Ymir died and when she got the confirmation of her death by Ymir's letter. Ymir, a person who pushed her self esteem in a healthy way. But now she is pretty much alone.

2) Making her dependent and indebted to him. Eren takes away her free will of choosing for herself, but telling her his plan is the only option, implying he is the only one who can save her. "Offering" to erase her memories is also manipulation and implies "I don't respect your own will", it's just wrapped inside sweet words.

She believes he wants to protect her after all. I think he does want to protect her and cares for her, but also manipulates her at the same time because his genocide/freedom philosophy is more important to him than anything else. He is a maniac, and maniacs often contradict themselves, it's almost like they have different personalities (sympathising with his enemies in chapter 100 / dehumanising them in chapter 130 by calling them "animals" is one example).

Going back to Historia, Eren boosts the feeling of indebtedness by telling her "You are the worst girl in this world WHO HAS SAVED ME". He makes her believe she wants to follow him herself, that she wants to serve his desires, that deep down she wants him to destroy the world. By that he is saving her, so she is indebted to follow him. That's at least what he implies. He doesn't give her another option. Doing this by twisting her own words is pretty genius and disgusting.

3) Telling her to obey and she does. I already implied why she obeys even if she doesn't want to, by manipulating her and making her believe she is dependent on him, taking away her free will to choose for herself, taking away her value and making her believe that's what she actually wants.

But just like Ymir, Historia looks depressed and conflicted all the time (Chapter 106-108). She has been emotionally abused all her life and this is no exception. I still don't believe she supports genocide and she shuts up because she is manipulated by Eren to do so. Just like Eren manipulated Grisha to kill children, even if Grisha didn't want that, but still did. Just like King Fritz manipulated Ymir to obey him, not to rebel against him, kill so many Marleyans and do whatever he wishes. And it's pretty clear Ymir wasn't happy with this either. As I said, the same pattern still happens today in people's real life. All the time.

Someone has to save Historia, I don't know if she can save herself, though I wish she would be capable of helping herself. But I think she is just too weak, emotionally confused and damaged to do so. Eren makes her believe he is the only one who can save her, but that dude is destroying her just like he is destroying himself by his toxic philosophy.

Again, someone has to save Historia. If she can't do this herself I believe that will be Reiner since he has promised Freckles Ymir to do so, and I don't even mean this in a shipping/romantic context! But this subplot is still open and fits to this situation.

Thank you for your question, I hope this was not too confusing and long!

#eren#Historia#eren yeager#historia reiss#founding ymir#ymir fritz#reiner braun#reiner#snk manga#snk 130#shingeki no kyojin#krista lenz#Freckles Ymir#Ymir#askdoro

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

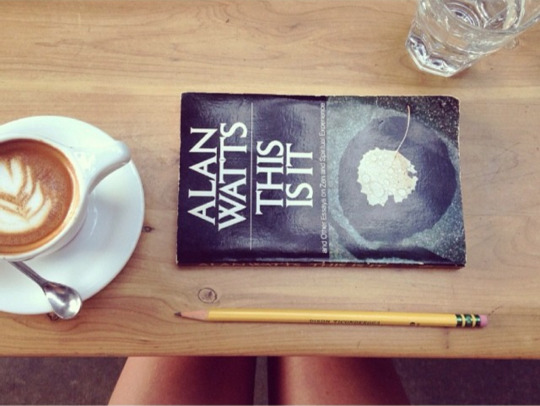

This Is IT by Alan Watts (and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual Experiences)

I give it: 7/10

Length: 153 pages

My Spiritual Awakening took place in Los Angeles, summer of 2014. At the same time, I read this text—and now, nearly six years later, want to synthesize the take-aways as I practice minimalism in reducing my extensive books collection to just 125 books.

In this text, Alan Watts defines this as, “Spiritual awakening is the difficult process whereby the increasing realization that everything is as wrong as it can be flips suddenly into the realization that everything is as right as it can be. Or better, everything is as It can be” (13).

Essays include:

This Is IT

Instinct, Intelligence, and Anxiety

Zen and the Problem of Control

Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen

Spirituality and Sensuality

The New Alchemy

The title essay, This Is IT focuses on current consciousness—the continually moving moment of NOW and on the necessity to let go of control in order to be open to all emotions and the “cosmic experience.”

“I believe that if this state of consciousness could become more universal, the pretentious nonsense which passes for the serious business of the world would dissolve in laughter” (12).

This essay slightly contradicts Abraham Hicks’ (Law of Attraction) assertion that your emotions matter most of all, as the indicator of your vibrational alignment (or disharmony) with all that is. Many Hicks’ listeners confuse this to me POSITIVE VIBES ONLY, when instead, Hicks affirms that negative emotions are not “wrong” or in need or control but instead act to move you towards what you do want and what feels good.

Watts echos Hicks by affirming that negative emotions are not wrong, but co-exist on the spectrum of emotions, and we should not try to control these feelings away/separate from us. In fact, Watts points out, enlightenment often arises in moments of despair. Contrasting emotions guide us towards what we want. However, Watts contradicts the idea that joy matters most, as he distinctly states that feelings of ecstasy are often confused for enlightenment.

“...[T]he immediate now is complete even when it is not ecstatic. For ecstasy is a necessarily impermanent contrast in the constant fluctuation of our feelings. But insight, when clear enough, persists; having once understood a particular skill, the facility tends to remain” (18-19).

Instead, Nirvana includes any/all emotions present and changing. Watts and Hicks alike encourage selfishness, while Hicks considers this a path to joy and Watts sees this humanness as a path to transcend the self to the “cosmic” whole or oneness, which he claims is purposeless and instead playful.

He points out that people mistakenly look for spiritual leaders to exhibit perfection over humanity:

“...[W]hether he shows anxiety or not, whether he depends upon ‘material crutches’ such as wine or tobacco, whether he loses his temper, or gets depressed, or falls in love when he shouldn’t, or sometimes looks a bit tired or frayed at the edges. All these criteria might be valid if the philosopher were preaching freedom from being human, or if he were trying to make himself or others radically better.... But the limits within which such improvements may be made are small in comparison with the vast aspects of our nature and our circumstances which remain the same.... I am saying...that while there is a place for bettering oneself and others, solving problems...this is by no means the only or even the chief principal of life....” (31-32).

Instead of prioritizing joy as an end-goal, Watts encourages purposelessness (as opposed to goal-setting and focus on improvement) and letting go of control as key to enlightenment:

“Nature is much more playful than purposeful, and the probability that it has no specific goals for the future need not strike one as a defect.... much more like art than business, politics, or religion. They are especially like the arts of music and dancing.... No one imagines that a symphony is supposed to improve in quality as it goes along, or that the whole object of playing is to reach the finale. The point of music is discovered in every moment of playing and listening to it” (32-33).

“...[I]f we are unduly absorbed in improving...we may forget altogether to live....” (33).

He goes onto say that if we believe that everything in the world is right just as it is, then we may perceive “our normal anxieties” as “ludicrous,” or a wrong response. Really, though, each emotion exists along a spectrum of all emotions, connected and contrasting one another in relation.

“...[T]he superior truth of the ‘cosmic’ experience... [C]ontrol must always be subordinate to motion if there is to be motion at all. In human terms, total restraint of movement is the equivalent of total doubt, of refusal to trust one’s senses or feelings.... On the other hand, movement and the release of restraint are the equivalent of faith, of committing oneself to the uncontrolled and the unknown..... An essential part of the ‘cosmic’ experience is, however that the normal restriction of consciousness to the ego-feeling is also right, but only and always because it is subordinate to absence of restriction, to movement and faith.... [T]here must be total affirmation and acceptance.... [F]or man to make himself mad by trying to bring everything under his control. We become insane, unsound, and without foundation when we lose consciousness of and faith in the uncontrolled and ungraspable...world which is ultimately what we ourselves are. And there is a very slight distinction, if any, between complete, conscious faith and love” (38-39).

One critique that I have with this essay is Watt’s meager attempt to assure that such acceptance of all as-is need not perpetuate injustice:

With little supporting evidence, he state that, “[E]ven though it may be exploited for this purpose, the experience itself is in no sense a philosophy designed to justify or desensitize oneself to the inequalities of life,” (26). He goes onto say, “...the holocaust of the biological world, where every living creatures lives by feeding off others.... is reversed so that every victim is seen as offering itself in sacrifice” (37), going onto argue that all is relative.

For me, this stretch contradicts experiences of the oppressed who fight against such an “offering” of themselves to a system that goes against their free will.

Overall, I think the message —to let go of control and constant striving for perfection, to accept all of our emotions as part of all that is— ironically offers an anecdote for an unbalanced culture to improve, through acceptance over action.

The other essays in this collection:

Instinct, Intelligence, and Anxiety looks at how humans differ from animals in our ability to analyze, predict, and decide—and at what cost.

Zen and the Problem of Control asks if, “man is a self-conscious and therefore self-controlling organism, how is he to control the aspect of himself which does the controlling?” Watts using judo as an example, of working with the blows delivered versus resisting. As it turns out—cooperation is key.

Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen opens pandora’s box of true Zen, traditional Zen, and cultural interpretations—including Jack Kerouac’s. Watts argues that in order to don a true Zen lifestyle, one must overcome any fear or rebellion of their own culture. “Lacking this, his Zen will either be ‘beat’ or ‘square,’ either a revolt...or a form of stuffiness.... Zen is above all the liberation of the mind from conventional though...utterly different from rebellion against convention, on one hand, or adapting foreign conventions on the other” (90).

Spirituality and Sensuality begins with how, “It has often been said that the human being is a combination of animal and angel....” and further explores the illusion of duality as a true unity that cannot exist without an opposite.

The New Alchemy is an acid test that starts off with talking about immortality. Watts discusses the high points and recurrent themes of his experiences on LSD, including facing the ultimate illusion: fear of death.

#minimalism#minimal#marie kondo#alan watts#buddhism#enlightenment#nirvana#abraham hicks#law of attraction#meditation#letting go#los angeles#venice beach#spirituality#books#reader#book review#zen#acid#acid test#lsd#Michael Pollan#psychadelic#mushrooms

1 note

·

View note

Link

Yoga teacher Tatiana Forero Puerta, author of Yoga for the Wounded Heart, shares what she’s learned about trauma, clearing emotional patterns, and finding a vision for the future.

Tatiana Forero Puerta

If at the age of 20 you would’ve asked me to imagine my life 15 years in the future, I wouldn’t have been able to give you an answer. I couldn’t see my life in those terms. When I looked into my future then, I simply saw a field of blackness; my potential was not just obfuscated—it was inaccessible. This is what trauma does: It blinds us. One of the effects of deep suffering, especially during childhood, is that it can rob us of our vision.

I lost my father back in my homeland of Bogotá, Colombia, when I was eight years old. The last time I saw him, he knelt at the doorstep of our apartment and gave me a tight squeeze, consoling me as I cried. He assured me he would be back from his business trip in three days’ time, but on his way home his car was hit head-on by a drunk driver. My father and three of his co-workers lost their lives that night. He was 36.

The last time I saw my mother, I was 14. I held her and stroked her balding head, and when I kissed it, I remember feeling as though I were kissing a baby’s head; it was so soft, so innocent. My mother, emaciated and childlike after a short, brutal battle with pancreatic cancer, took her last breaths in my arms. She was 40.

See also A Yoga Therapist Shares The Truth About Trauma

Facing Childhood as an Orphan

After my parents’ shocking and premature deaths, I was transferred to a foster home where the child abuse became so severe that my sister and I were eventually removed, only to be returned to the same place a year later. These profound and destabilizing experiences in my youth became the framework for my identity: Tatiana, the orphan. Tatiana, the girl without a home.

By the time I hit my early 20s, I had lived in and out of nearly 30 different homes, unable to find grounding. I felt isolated, and I had no idea what to do with all my pain. What was more is that when I looked into my future, all I could access was my parents’ deaths. I could not picture a reality where I would get to live beyond the years that my parents were given. And, at 22, as the anniversary of my father’s death approached, I subconsciously wanted to ensure that his fate would become mine, and I attempted to take my own life.

See also 5 Practices to Invite Transformation.

What Are Samskaras and How do You Heal Them?

These were some of my deepest samskaras—the mental and emotional impressions or patterns that become imprinted in our psyches as a result of our experiences. The body of yoga, not just as a physical practice, but as a mental, emotional, and spiritual discipline and guide into our consciousness and psyche, teaches us that these impressions can greatly affect how we experience and interpret the circumstances of our lives, and hence greatly impact our capacity for happiness and our experiences of suffering. The intensity of each samskara depends on a variety of factors, including our age, vulnerability, and ability to cope with or assimilate situations. Samskaras stay with us beyond the time we first have an experience, and, when unchecked, can have devastating consequences. They may taint the way we see and experience ourselves and our world, keeping us in the loop of suffering, or avidyā, translated as misconception, ignorance, or non-seeing. In other words, samskaras that we are unaware of or that we don’t heal have the capacity to blind us from what is here, keeping us tethered to a past version of our experiences.

Today, advanced studies in neuroscience and psychology have confirmed what the wisdom of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra suggested more than 2,000 years ago: first, that the brain is physically and functionally affected as a result of traumas or profound samskaras, and that these changes can affect individuals’ self-concepts—their visions of themselves and their lives—and second, perhaps most importantly, that the brain also has the capacity to heal, to rewire or rewrite the impression, so that it can be experienced differently. Instead of throwing us into the habitual pain of suffering, we can learn to experience a pause, see a lesson, or even gain insight for which we become grateful.

See also Find Your Willpower with This Samskara-Busting Sequence

The Necessity of Daily Practice

But the work is ongoing, and the depths of our conditioning is astounding. Even years after being on the yogic path, I was blindsided by a new aspect of the same samskara of my youth, the one that kept me tethered to my experiences with early and untimely death, even though I thought I had healed it. Upon the birth of my son, my first weeks of motherhood were spent in abject terror. I’d hold my tiny newborn tightly and feel overwhelmed by the fear that either he or I would suddenly die. It was excruciating to have someone else hold him; I wanted him at my side at all times. Anything else would give rise in me to powerful sensations that seemed to take over my body, rob me of rationality, and throw me into a tailspin of panic. I had recurring death-themed nightmares, and when I looked into my future with my child, I once again experienced the blackness—the blinding of my possibility.

Petrified and facing continual panic attacks resembling those of my youth, I turned to my practice: This time, I had tools. I had the understanding that this fear felt true to me because of my wiring, and I knew that it could be reframed, that it could be healed. Through my practice, I worked with this hidden aspect of an old samskara, one that might not have shown up had I not decided to become a mother.

I practiced despite the discomfort, and met my fear again and again with a curious mind and a forgiving heart. I came with the willingness to greet what was here, armed with my breath and the faith—the awareness—of the power of this practice. Some days I cried. Some days I got flashbacks. Some days I felt relief. Little by little my symptoms decreased. The beauty of healing is that it arrives with vision and insight: insight into my parents’ experiences, insight into the softness of vulnerability, insight into the human proclivity to cling when we love, and into the practice of trusting that life is here to support us when we learn to let go. The work helped me find examples that contradicted my terror: Instead of seeing my parents’ early deaths as the markers for my experience, my practice began to open my eyes to the many, many adult friends I had with adult children who were alive and thriving. It was possible, then—even probable—that my son and I were going to be OK.

See also The Avoidance Mechanisms We Have to Face In Order To Heal

Today, I believe that I am living proof of Patanjali’s assertion that the yogic path is a radical vehicle for clearing our samskaras. The work has not been easy; it has been painstaking and constant. It has been eye- and heart-opening.

It is through this very process of rewiring that I find myself here today, in my mid-30s, having outlived my father and walking toward the precipice of my mother’s age when she passed. I find myself hand-in-hand with my amazing three-year-old son. Today, when I look toward the horizon in front of me, I see a vast field of possibility. I see my son grown up, our relationship blossoming; I see the fruits of my labor, the hours spent in practice and the wisdom gained from these practices; I see many sunrises and sunsets. My yoga gave me back my vision, and in many ways, it has given me back my life.

See also Here’s How We’re Using Our Experience of Trauma to Help Others

About the author

Tatiana Forero Puerta is the author of Yoga for the Wounded Heart: A Journey, Philosophy, and Practice of Healing Emotional Pain and Cleaning the Ghost Room (forthcoming, 2020). A graduate of Stanford University and New York University, Tatiana has taught philosophy and yoga for more than a decade. Learn more at yogaforthewoundedheart.com.

0 notes

Link

Yoga teacher Tatiana Forero Puerta, author of Yoga for the Wounded Heart, shares what she’s learned about trauma, clearing emotional patterns, and finding a vision for the future.

Tatiana Forero Puerta

If at the age of 20 you would’ve asked me to imagine my life 15 years in the future, I wouldn’t have been able to give you an answer. I couldn’t see my life in those terms. When I looked into my future then, I simply saw a field of blackness; my potential was not just obfuscated—it was inaccessible. This is what trauma does: It blinds us. One of the effects of deep suffering, especially during childhood, is that it can rob us of our vision.

I lost my father back in my homeland of Bogotá, Colombia, when I was eight years old. The last time I saw him, he knelt at the doorstep of our apartment and gave me a tight squeeze, consoling me as I cried. He assured me he would be back from his business trip in three days’ time, but on his way home his car was hit head-on by a drunk driver. My father and three of his co-workers lost their lives that night. He was 36.

The last time I saw my mother, I was 14. I held her and stroked her balding head, and when I kissed it, I remember feeling as though I were kissing a baby’s head; it was so soft, so innocent. My mother, emaciated and childlike after a short, brutal battle with pancreatic cancer, took her last breaths in my arms. She was 40.

See also A Yoga Therapist Shares The Truth About Trauma

Facing Childhood as an Orphan

After my parents’ shocking and premature deaths, I was transferred to a foster home where the child abuse became so severe that my sister and I were eventually removed, only to be returned to the same place a year later. These profound and destabilizing experiences in my youth became the framework for my identity: Tatiana, the orphan. Tatiana, the girl without a home.

By the time I hit my early 20s, I had lived in and out of nearly 30 different homes, unable to find grounding. I felt isolated, and I had no idea what to do with all my pain. What was more is that when I looked into my future, all I could access was my parents’ deaths. I could not picture a reality where I would get to live beyond the years that my parents were given. And, at 22, as the anniversary of my father’s death approached, I subconsciously wanted to ensure that his fate would become mine, and I attempted to take my own life.

See also 5 Practices to Invite Transformation.

What Are Samskaras and How do You Heal Them?

These were some of my deepest samskaras—the mental and emotional impressions or patterns that become imprinted in our psyches as a result of our experiences. The body of yoga, not just as a physical practice, but as a mental, emotional, and spiritual discipline and guide into our consciousness and psyche, teaches us that these impressions can greatly affect how we experience and interpret the circumstances of our lives, and hence greatly impact our capacity for happiness and our experiences of suffering. The intensity of each samskara depends on a variety of factors, including our age, vulnerability, and ability to cope with or assimilate situations. Samskaras stay with us beyond the time we first have an experience, and, when unchecked, can have devastating consequences. They may taint the way we see and experience ourselves and our world, keeping us in the loop of suffering, or avidyā, translated as misconception, ignorance, or non-seeing. In other words, samskaras that we are unaware of or that we don’t heal have the capacity to blind us from what is here, keeping us tethered to a past version of our experiences.

Today, advanced studies in neuroscience and psychology have confirmed what the wisdom of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra suggested more than 2,000 years ago: first, that the brain is physically and functionally affected as a result of traumas or profound samskaras, and that these changes can affect individuals’ self-concepts—their visions of themselves and their lives—and second, perhaps most importantly, that the brain also has the capacity to heal, to rewire or rewrite the impression, so that it can be experienced differently. Instead of throwing us into the habitual pain of suffering, we can learn to experience a pause, see a lesson, or even gain insight for which we become grateful.

See also Find Your Willpower with This Samskara-Busting Sequence

The Necessity of Daily Practice

But the work is ongoing, and the depths of our conditioning is astounding. Even years after being on the yogic path, I was blindsided by a new aspect of the same samskara of my youth, the one that kept me tethered to my experiences with early and untimely death, even though I thought I had healed it. Upon the birth of my son, my first weeks of motherhood were spent in abject terror. I’d hold my tiny newborn tightly and feel overwhelmed by the fear that either he or I would suddenly die. It was excruciating to have someone else hold him; I wanted him at my side at all times. Anything else would give rise in me to powerful sensations that seemed to take over my body, rob me of rationality, and throw me into a tailspin of panic. I had recurring death-themed nightmares, and when I looked into my future with my child, I once again experienced the blackness—the blinding of my possibility.

Petrified and facing continual panic attacks resembling those of my youth, I turned to my practice: This time, I had tools. I had the understanding that this fear felt true to me because of my wiring, and I knew that it could be reframed, that it could be healed. Through my practice, I worked with this hidden aspect of an old samskara, one that might not have shown up had I not decided to become a mother.

I practiced despite the discomfort, and met my fear again and again with a curious mind and a forgiving heart. I came with the willingness to greet what was here, armed with my breath and the faith—the awareness—of the power of this practice. Some days I cried. Some days I got flashbacks. Some days I felt relief. Little by little my symptoms decreased. The beauty of healing is that it arrives with vision and insight: insight into my parents’ experiences, insight into the softness of vulnerability, insight into the human proclivity to cling when we love, and into the practice of trusting that life is here to support us when we learn to let go. The work helped me find examples that contradicted my terror: Instead of seeing my parents’ early deaths as the markers for my experience, my practice began to open my eyes to the many, many adult friends I had with adult children who were alive and thriving. It was possible, then—even probable—that my son and I were going to be OK.

See also The Avoidance Mechanisms We Have to Face In Order To Heal

Today, I believe that I am living proof of Patanjali’s assertion that the yogic path is a radical vehicle for clearing our samskaras. The work has not been easy; it has been painstaking and constant. It has been eye- and heart-opening.

It is through this very process of rewiring that I find myself here today, in my mid-30s, having outlived my father and walking toward the precipice of my mother’s age when she passed. I find myself hand-in-hand with my amazing three-year-old son. Today, when I look toward the horizon in front of me, I see a vast field of possibility. I see my son grown up, our relationship blossoming; I see the fruits of my labor, the hours spent in practice and the wisdom gained from these practices; I see many sunrises and sunsets. My yoga gave me back my vision, and in many ways, it has given me back my life.

See also Here’s How We’re Using Our Experience of Trauma to Help Others

About the author

Tatiana Forero Puerta is the author of Yoga for the Wounded Heart: A Journey, Philosophy, and Practice of Healing Emotional Pain and Cleaning the Ghost Room (forthcoming, 2020). A graduate of Stanford University and New York University, Tatiana has taught philosophy and yoga for more than a decade. Learn more at yogaforthewoundedheart.com.

0 notes

Text

Overcoming Past Trauma to Create a New Future

Yoga teacher Tatiana Forero Puerta, author of Yoga for the Wounded Heart, shares what she’s learned about trauma, clearing emotional patterns, and finding a vision for the future.

Tatiana Forero Puerta

If at the age of 20 you would’ve asked me to imagine my life 15 years in the future, I wouldn’t have been able to give you an answer. I couldn’t see my life in those terms. When I looked into my future then, I simply saw a field of blackness; my potential was not just obfuscated—it was inaccessible. This is what trauma does: It blinds us. One of the effects of deep suffering, especially during childhood, is that it can rob us of our vision.

I lost my father back in my homeland of Bogotá, Colombia, when I was eight years old. The last time I saw him, he knelt at the doorstep of our apartment and gave me a tight squeeze, consoling me as I cried. He assured me he would be back from his business trip in three days’ time, but on his way home his car was hit head-on by a drunk driver. My father and three of his co-workers lost their lives that night. He was 36.

The last time I saw my mother, I was 14. I held her and stroked her balding head, and when I kissed it, I remember feeling as though I were kissing a baby’s head; it was so soft, so innocent. My mother, emaciated and childlike after a short, brutal battle with pancreatic cancer, took her last breaths in my arms. She was 40.

See also A Yoga Therapist Shares The Truth About Trauma

Facing Childhood as an Orphan

After my parents’ shocking and premature deaths, I was transferred to a foster home where the child abuse became so severe that my sister and I were eventually removed, only to be returned to the same place a year later. These profound and destabilizing experiences in my youth became the framework for my identity: Tatiana, the orphan. Tatiana, the girl without a home.

By the time I hit my early 20s, I had lived in and out of nearly 30 different homes, unable to find grounding. I felt isolated, and I had no idea what to do with all my pain. What was more is that when I looked into my future, all I could access was my parents’ deaths. I could not picture a reality where I would get to live beyond the years that my parents were given. And, at 22, as the anniversary of my father’s death approached, I subconsciously wanted to ensure that his fate would become mine, and I attempted to take my own life.

See also 5 Practices to Invite Transformation.

What Are Samskaras and How do You Heal Them?

These were some of my deepest samskaras—the mental and emotional impressions or patterns that become imprinted in our psyches as a result of our experiences. The body of yoga, not just as a physical practice, but as a mental, emotional, and spiritual discipline and guide into our consciousness and psyche, teaches us that these impressions can greatly affect how we experience and interpret the circumstances of our lives, and hence greatly impact our capacity for happiness and our experiences of suffering. The intensity of each samskara depends on a variety of factors, including our age, vulnerability, and ability to cope with or assimilate situations. Samskaras stay with us beyond the time we first have an experience, and, when unchecked, can have devastating consequences. They may taint the way we see and experience ourselves and our world, keeping us in the loop of suffering, or avidyā, translated as misconception, ignorance, or non-seeing. In other words, samskaras that we are unaware of or that we don’t heal have the capacity to blind us from what is here, keeping us tethered to a past version of our experiences.

Today, advanced studies in neuroscience and psychology have confirmed what the wisdom of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra suggested more than 2,000 years ago: first, that the brain is physically and functionally affected as a result of traumas or profound samskaras, and that these changes can affect individuals’ self-concepts—their visions of themselves and their lives—and second, perhaps most importantly, that the brain also has the capacity to heal, to rewire or rewrite the impression, so that it can be experienced differently. Instead of throwing us into the habitual pain of suffering, we can learn to experience a pause, see a lesson, or even gain insight for which we become grateful.

See also Find Your Willpower with This Samskara-Busting Sequence

The Necessity of Daily Practice

But the work is ongoing, and the depths of our conditioning is astounding. Even years after being on the yogic path, I was blindsided by a new aspect of the same samskara of my youth, the one that kept me tethered to my experiences with early and untimely death, even though I thought I had healed it. Upon the birth of my son, my first weeks of motherhood were spent in abject terror. I’d hold my tiny newborn tightly and feel overwhelmed by the fear that either he or I would suddenly die. It was excruciating to have someone else hold him; I wanted him at my side at all times. Anything else would give rise in me to powerful sensations that seemed to take over my body, rob me of rationality, and throw me into a tailspin of panic. I had recurring death-themed nightmares, and when I looked into my future with my child, I once again experienced the blackness—the blinding of my possibility.

Petrified and facing continual panic attacks resembling those of my youth, I turned to my practice: This time, I had tools. I had the understanding that this fear felt true to me because of my wiring, and I knew that it could be reframed, that it could be healed. Through my practice, I worked with this hidden aspect of an old samskara, one that might not have shown up had I not decided to become a mother.

I practiced despite the discomfort, and met my fear again and again with a curious mind and a forgiving heart. I came with the willingness to greet what was here, armed with my breath and the faith—the awareness—of the power of this practice. Some days I cried. Some days I got flashbacks. Some days I felt relief. Little by little my symptoms decreased. The beauty of healing is that it arrives with vision and insight: insight into my parents’ experiences, insight into the softness of vulnerability, insight into the human proclivity to cling when we love, and into the practice of trusting that life is here to support us when we learn to let go. The work helped me find examples that contradicted my terror: Instead of seeing my parents’ early deaths as the markers for my experience, my practice began to open my eyes to the many, many adult friends I had with adult children who were alive and thriving. It was possible, then—even probable—that my son and I were going to be OK.

See also The Avoidance Mechanisms We Have to Face In Order To Heal

Today, I believe that I am living proof of Patanjali’s assertion that the yogic path is a radical vehicle for clearing our samskaras. The work has not been easy; it has been painstaking and constant. It has been eye- and heart-opening.

It is through this very process of rewiring that I find myself here today, in my mid-30s, having outlived my father and walking toward the precipice of my mother’s age when she passed. I find myself hand-in-hand with my amazing three-year-old son. Today, when I look toward the horizon in front of me, I see a vast field of possibility. I see my son grown up, our relationship blossoming; I see the fruits of my labor, the hours spent in practice and the wisdom gained from these practices; I see many sunrises and sunsets. My yoga gave me back my vision, and in many ways, it has given me back my life.

See also Here’s How We’re Using Our Experience of Trauma to Help Others

About the author

Tatiana Forero Puerta is the author of Yoga for the Wounded Heart: A Journey, Philosophy, and Practice of Healing Emotional Pain and Cleaning the Ghost Room (forthcoming, 2020). A graduate of Stanford University and New York University, Tatiana has taught philosophy and yoga for more than a decade. Learn more at yogaforthewoundedheart.com.

0 notes

Link

As an African social entrepreneur in the technology industry, I am forced than most to think in terms of -whole systems".

Not a single technology I have worked on has ever been deployable without building a whole ecosystem afresh. This means that I need to be exceptionally attuned to the cultural and political economy context of technology. It also means that I find most of the debates around blockchain somewhat na\cEFve because of the perennial failure to address its ideological baggage and consider how other cultures might relate to that ideology.

In many ways this ideo-cultural blindspot is the true cause of blockchain's struggles to scale and become ubiquitous.

Blockchain's original creators understandably want less trust and more trustlessness in the world they seek to build. In the case of cryptocurrencies, blockchain's only globally successful application to date, for instance, concerns about interconvertibility or divisibility or the impact of volatility on credit are trivial. They completely underestimate the power of -smart contracts", self-executing computer programs that can be used to program how any financial metric should behave given a particular scenario, addressing many of the drawbacks usually cited as showstoppers.

In fact, AI-based smart contracts can even anticipate hard to predict scenarios. And virtually any smart contract of the appropriate kind would be cheaper and more adaptable than even the best contracts drafted by the best lawyers.

The real problem of blockchain goes to its roots, to the implicit manifesto which embedded the values of its creators in 2008 into the underlying concept.

At the core of the blockchain theory, first applied to bitcoin, is the idea of transactions between equals (peers) without a trusted third party.

This -trustless" approach originates in Blockchain creators' desire to remove the power of powerful authorities (whether banks, stock exchanges or governments) to grant or deny -permissions" and -privileges".

-Trust", in the understanding of these techno-activists, is therefore almost synonymous with -dependency" in a -power relationship". Blockchain's original creators understandably therefore want less trust and more trustlessness in the world they seek to build.

There are different ways of seeing -trust". Africa's Ubuntu ideology, for instance, interprets it as an emergent property of collaboration systems. It is very critical to understand this underlying vision of blockchain. It emerges from within very deep places in the Western tradition, and easily traceable from the radical 16th French theorist, Etienne de La Bo\cE9tie, all the way down to Robert Nozick.

Starting from such puzzles as the ancient Byzantine Generals' problem of how to coordinate an attack by allied armies using messengers who could have been compromised, blockchain cryptographers have dramatically expanded the implications of their mathematical solutions, and claimed the capacity to make -trust" irrelevant.

But there are actually different ways of seeing -trust". Africa's Ubuntu ideology, for instance, interprets it as an emergent property of certain collaboration systems. It is not a static quality that some network has. It is something that grows over time as a result of evolving rules created and recreated by the participants.

Please don't confuse my point as canvassing for -African exceptionalism". Ubuntu was just one example. The Dutch theorist, Bart Nooteboom, comes to remarkably similar conclusions in a career spent examining the -trust" concept.

In his seminal 2006 paper (which extends his equally seminal 2002 paper) on how social capital, trust and institutions interrelate, he made the profound statement: -Trust is both an outcome and an antecedent of relationships."

He sees the dynamic nature of trust, but most importantly he strongly deviates from the notion of trust as resulting merely from some calculation of the risks of some party acting contrary to an agreement (which is basically how the original philosophy behind blockchain sees trust). The agreement is but the starting point. How it shapes the behaviour of both parties over time is more important than knowing whether at some point in the future either party will keep to the terms.

Another way of fully grasping Nooteboom's arguments is to see trust as a composite with changing composition over time. Trust in intentions is not the same thing as trust in competence. Nor is trust in position the same as trust in orientation, etc. For that reason alone, in the real world, trust is fluid and organic.

If you look at the attached Maister equation in the image it is obvious that whilst blockchain scores strongly on -reliability", it does very badly on -intimacy". This further reinforces the argument that the original designers had a na\cEFve, simplistic, understanding of -trust" and thus designed a -trustless" system that actually is merely -trust-weak".

With the above in mind, it is easy to see the naivete of the idea that trust among network actors is not necessary so long as every operation in a network is replicated in the same fashion across every computer before attaining validity. For the simple reason that it makes rather credulous assumptions about the -peers" in this network, starting from a rather crude reduction of trust to predictability.

Firstly, not all -peers" in the real world are connecting and engaging in the same way, to the same extent, for the same goals, with the same expectations, and at the same strength.

Some of the participating users in the peer networks of blockchain need support from more competent parties to achieve their particular goal in the network.

So, for example, in many African markets, most retail investors participating in the bitcoin trading mania simply contract the entire headache to younger, more dynamic, -consultants". In the West, participants use wallets made by third parties to hold their bitcoins and install tools supported by SAAS providers to manage their access keys.

In both societies, we see at work a process of -delegated trust", but in the West the non-technical blockchain participant is happy to mask that delegation of trust behind a firewall of impersonality. In Africa, social capital is cheaper so the relatively wealthier investor would rather not trust some impersonal certificate authority or Public Key Infrastructure provider. The African bitcoin investor might prefer to deal with an upcoming IT technician who is looking to gain more from the relationship than just the fee of helping her digitally less savvy client maintain her bitcoin portfolio.

But let's make no mistake about it: in neither instance, Western or African, is the original blockchain vision of a trustless system achieved. Across the entire blockchain economy today, multiple layers of competence, convenience, risk management, and social capital (why an ICO backed by more -credible" people still perform better than one by complete unknowns) lubricate the cogs and wheels of the blockchain protocol. However, the precise configuration of these layers are likely to differ from society to society, and culture to culture.

The intermediaries that Blockchain purists insist must not determine how transactions occur are very much in place, simply because the average user of technology, whether email or blockchain, cannot become a cryptographer or PKI expert just to be able to hold true to the original notion of a true peer to peer system of equals operating without intermediation.

The promise of a trustless system continues, however, to create dissonance. On one hand, blockchain systems are projected as wholesale replacements for institutions, and, on the other hand, -co-innovation" is demanded from the same institutions to enable blockchain systems to become viable. This is a palpable contradiction.

Blockchain systems will not thrive except in the context of -more trust", properly defined. Trust in the competence, availability, orientation, positioning and intents of the multiple layers of intermediation is needed before blockchain applications can actually enhance hopelessly broken systems like SME to SME international trade.

For example, to replace letters of credit (LOCs) with blockchain smart contracts, freight forwarders, banks, customs clearance agents, invoice discounters and a whole bunch of peripheral players need to understand the system better, make investments to support them, project reasonable future gains, hire the right consultants to guide development, and alter current business models. Without a considerable increase in the level of trust among these actors, forget about smart contract LOCs going mainstream. In the end, any truly effective version of the system that emerges must allow intermediation and trust.

Note that trust here does not require the absolute technical predictability promoted by the original blockchain theorists. In fact, the trust will come through working together.

That means considerable deviation from the Hobbesian vision in which the design of a blockchain system assumes from the start that everyone is a potential traitor and will stay that way regardless of how the relationships evolve.

That worldview has led to wasted investments in blockchain designs that simply do not deliver performance, user-friendliness, convenience and clarity. And yet, all these are components of trust, properly defined.

Until systems innovators who see -more trust" as essential for all forms of digital interactions and know how to build systems that enhance trust get involved, blockchain applications shall fail to integrate at scale into those systems where they can make the most impact: health financing, supply chain transparency, international trade, public integrity etc.

So, if you are going to adopt blockchain to solve any problem facing your business or country, bear this point in mind.

Sign up for the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief - the most important and interesting news from across the continent, in your inbox.

https://ift.tt/2H9WtJU

0 notes

Text

Blockchain in Africa, Ubuntu and the end of traditional concepts of trust — Quartz

New Post has been published on https://cryptnus.com/2018/04/blockchain-in-africa-ubuntu-and-the-end-of-traditional-concepts-of-trust-quartz/

Blockchain in Africa, Ubuntu and the end of traditional concepts of trust — Quartz

As an African social entrepreneur in the technology industry, I am forced than most to think in terms of “whole systems”.

Not a single technology I have worked on has ever been deployable without building a whole ecosystem afresh. This means that I need to be exceptionally attuned to the cultural and political economy context of technology. It also means that I find most of the debates around blockchain somewhat naïve because of the perennial failure to address its ideological baggage and consider how other cultures might relate to that ideology.

In many ways this ideo-cultural blindspot is the true cause of blockchain’s struggles to scale and become ubiquitous.

Blockchain’s original creators understandably want less trust and more trustlessness in the world they seek to build. In the case of cryptocurrencies, blockchain’s only globally successful application to date, for instance, concerns about interconvertibility or divisibility or the impact of volatility on credit are trivial. They completely underestimate the power of “smart contracts”, self-executing computer programs that can be used to program how any financial metric should behave given a particular scenario, addressing many of the drawbacks usually cited as showstoppers.

In fact, AI-based smart contracts can even anticipate hard to predict scenarios. And virtually any smart contract of the appropriate kind would be cheaper and more adaptable than even the best contracts drafted by the best lawyers.

The real problem of blockchain goes to its roots, to the implicit manifesto which embedded the values of its creators in 2008 into the underlying concept.

At the core of the blockchain theory, first applied to bitcoin, is the idea of transactions between equals (peers) without a trusted third party.

This “trustless” approach originates in Blockchain creators’ desire to remove the power of powerful authorities (whether banks, stock exchanges or governments) to grant or deny “permissions” and “privileges”.

“Trust”, in the understanding of these techno-activists, is therefore almost synonymous with “dependency” in a “power relationship”. Blockchain’s original creators understandably therefore want less trust and more trustlessness in the world they seek to build.

There are different ways of seeing “trust”. Africa’s Ubuntu ideology, for instance, interprets it as an emergent property of collaboration systems. It is very critical to understand this underlying vision of blockchain. It emerges from within very deep places in the Western tradition, and easily traceable from the radical 16th French theorist, Etienne de La Boétie, all the way down to Robert Nozick.

Starting from such puzzles as the ancient Byzantine Generals’ problem of how to coordinate an attack by allied armies using messengers who could have been compromised, blockchain cryptographers have dramatically expanded the implications of their mathematical solutions, and claimed the capacity to make “trust” irrelevant.

But there are actually different ways of seeing “trust”. Africa’s Ubuntu ideology, for instance, interprets it as an emergent property of certain collaboration systems. It is not a static quality that some network has. It is something that grows over time as a result of evolving rules created and recreated by the participants.

Please don’t confuse my point as canvassing for “African exceptionalism”. Ubuntu was just one example. The Dutch theorist, Bart Nooteboom, comes to remarkably similar conclusions in a career spent examining the “trust” concept.

In his seminal 2006 paper (which extends his equally seminal 2002 paper) on how social capital, trust and institutions interrelate, he made the profound statement: “Trust is both an outcome and an antecedent of relationships.”

He sees the dynamic nature of trust, but most importantly he strongly deviates from the notion of trust as resulting merely from some calculation of the risks of some party acting contrary to an agreement (which is basically how the original philosophy behind blockchain sees trust). The agreement is but the starting point. How it shapes the behaviour of both parties over time is more important than knowing whether at some point in the future either party will keep to the terms.

Another way of fully grasping Nooteboom’s arguments is to see trust as a composite with changing composition over time. Trust in intentions is not the same thing as trust in competence. Nor is trust in position the same as trust in orientation, etc. For that reason alone, in the real world, trust is fluid and organic.

If you look at the attached Maister equation in the image it is obvious that whilst blockchain scores strongly on “reliability”, it does very badly on “intimacy”. This further reinforces the argument that the original designers had a naïve, simplistic, understanding of “trust” and thus designed a “trustless” system that actually is merely “trust-weak”.

With the above in mind, it is easy to see the naivete of the idea that trust among network actors is not necessary so long as every operation in a network is replicated in the same fashion across every computer before attaining validity. For the simple reason that it makes rather credulous assumptions about the “peers” in this network, starting from a rather crude reduction of trust to predictability.

Firstly, not all “peers” in the real world are connecting and engaging in the same way, to the same extent, for the same goals, with the same expectations, and at the same strength.

Some of the participating users in the peer networks of blockchain need support from more competent parties to achieve their particular goal in the network.

So, for example, in many African markets, most retail investors participating in the bitcoin trading mania simply contract the entire headache to younger, more dynamic, “consultants”. In the West, participants use wallets made by third parties to hold their bitcoins and install tools supported by SAAS providers to manage their access keys.

In both societies, we see at work a process of “delegated trust”, but in the West the non-technical blockchain participant is happy to mask that delegation of trust behind a firewall of impersonality. In Africa, social capital is cheaper so the relatively wealthier investor would rather not trust some impersonal certificate authority or Public Key Infrastructure provider. The African bitcoin investor might prefer to deal with an upcoming IT technician who is looking to gain more from the relationship than just the fee of helping her digitally less savvy client maintain her bitcoin portfolio.

But let’s make no mistake about it: in neither instance, Western or African, is the original blockchain vision of a trustless system achieved. Across the entire blockchain economy today, multiple layers of competence, convenience, risk management, and social capital (why an ICO backed by more “credible” people still perform better than one by complete unknowns) lubricate the cogs and wheels of the blockchain protocol. However, the precise configuration of these layers are likely to differ from society to society, and culture to culture.

The intermediaries that Blockchain purists insist must not determine how transactions occur are very much in place, simply because the average user of technology, whether email or blockchain, cannot become a cryptographer or PKI expert just to be able to hold true to the original notion of a true peer to peer system of equals operating without intermediation.

The promise of a trustless system continues, however, to create dissonance. On one hand, blockchain systems are projected as wholesale replacements for institutions, and, on the other hand, “co-innovation” is demanded from the same institutions to enable blockchain systems to become viable. This is a palpable contradiction.

Blockchain systems will not thrive except in the context of “more trust”, properly defined. Trust in the competence, availability, orientation, positioning and intents of the multiple layers of intermediation is needed before blockchain applications can actually enhance hopelessly broken systems like SME to SME international trade.

For example, to replace letters of credit (LOCs) with blockchain smart contracts, freight forwarders, banks, customs clearance agents, invoice discounters and a whole bunch of peripheral players need to understand the system better, make investments to support them, project reasonable future gains, hire the right consultants to guide development, and alter current business models. Without a considerable increase in the level of trust among these actors, forget about smart contract LOCs going mainstream. In the end, any truly effective version of the system that emerges must allow intermediation and trust.

Note that trust here does not require the absolute technical predictability promoted by the original blockchain theorists. In fact, the trust will come through working together.

That means considerable deviation from the Hobbesian vision in which the design of a blockchain system assumes from the start that everyone is a potential traitor and will stay that way regardless of how the relationships evolve.

That worldview has led to wasted investments in blockchain designs that simply do not deliver performance, user-friendliness, convenience and clarity. And yet, all these are components of trust, properly defined.

Until systems innovators who see “more trust” as essential for all forms of digital interactions and know how to build systems that enhance trust get involved, blockchain applications shall fail to integrate at scale into those systems where they can make the most impact: health financing, supply chain transparency, international trade, public integrity etc.

So, if you are going to adopt blockchain to solve any problem facing your business or country, bear this point in mind.

Sign up for the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief — the most important and interesting news from across the continent, in your inbox.

Most Popular

Why are Walmart and Amazon desperate to buy Flipkart?

0 notes