#but it’s also fascinating to see how the script evolves between what’s written & what makes the final cut

Text

Articulating Why His Dark Materials is Badly Written

A long essay-thing with lots of specific examples and explanations of why I feel this way. Hopefully I’ve kept fanboy bitching to a minimum.

This isn’t an attack on fans of the show, nor a personal attack on Jack Thorne. I’m not looking to ruin anyone’s enjoyment of the show, I just needed to properly articulate, with examples, why I struggle with it. I read and love the books and that colours my view, but I believe that HDM isn’t just a clumsy, at-best-functional, sometimes incompetent adaptation, it’s a bad TV show separate from its source material. The show is the blandest, least interesting and least engaging version of itself it could be.

His Dark Materials has gorgeous production design and phenomenal visual effects. It's well-acted. The score is great. But my god is it badly written. Jack Thorne writing the entire first season damned the show. There was no-one to balance out his flaws and biases. Thorne is checking off a list of plot-points, so concerned with manoeuvring the audience through the story he forgets to invest us in it. The scripts are mechanical, empty, flat.

Watching HDM feels like an impassioned fan earnestly lecturing you on why the books are so good- (Look! It's got other worlds and religious allegory and this character Lyra is really, really important I swear. Isn't Mrs Coulter crazy? The Gyptians are my favourites.) rather than someone telling the story naturally.

My problems fall into 5 main categories:

Exposition- An unwillingness to meaningfully expand the source material for a visual medium means Thorne tells and doesn't show crucial plot-points. He then repeats the same thing multiple times because he doesn't trust his audience

Pacing- By stretching out the books and not trusting his audience Thorne dedicates entire scenes to one piece of information and repeats himself constantly (see: the Witches' repetition of the prophecy in S2).

Narrative priorities- Thorne prioritises human drama over fantasy. This makes sense budgetarily, but leads to barely-present Daemons, the Gyptians taking up too much screentime, rushed/badly written Witches (superpowers, exposition) and Bears (armourless bear fight), and a Lyra more focused on familial angst than the joy of discovery

Tension and Mystery- because HDM is in such a hurry to set up its endgame it gives you the answers to S1's biggest mysteries immediately- other worlds, Lyra's parents, what happens to the kids etc. This makes the show less engaging and feel like it's playing catch-up to the audience, not the other way around.

Tonal Inconsistency- HDM tries to be a slow-paced, grounded, adult drama, but its blunt, simplistic dialogue and storytelling methods treat the audience like children that need to be lectured.

MYSTERY, SUSPENSE AND INTRIGUE

The show undercuts all the books’ biggest mysteries. Mrs Coulter is set up as a villain before we meet her, other worlds are revealed in 1x2, Lyra's parents by 1x3, what the Magesterium do to kids is spelled out long before Lyra finds Billy (1x2). I understand not wanting to lose new viewers, but neutering every mystery kills momentum and makes the show much less engaging.

This extends to worldbuilding. The text before 1x1 explains both Daemons and Lyra's destiny before we meet her. Instead of encouraging us to engage with the world and ask questions, we're given all the answers up front and told to sit back and let ourselves be spoon-fed. The viewer is never an active participant, never encouraged to theorise or wonder

Intrigue motivated you to engage with Pullman's philosophical themes and concepts. Without it, HDM feels like a lecture, a theme park ride and not a journey.

The only one of S1's mysteries left undiminished is 'what is Dust?', which won't be properly answered until S3, and that answer is super conceptual and therefore hard to make dramatically satisfying

TONAL INCONSISTENCY

HDM billed itself as a HBO-level drama, and was advertised as a GoT inheritor. It takes itself very seriously- the few attempts at humour are stilted and out of place

The production design is deliberately subdued, most notably choosing a mid-twentieth century aesthetic for Lyra’s world over the late-Victorian of the books or steampunk of the movie. The colour grading would be appropriate for a serious adult drama.

Reviewers have said this stops the show feeling as fantastical as it should. It also makes Lyra’s world less distinct from our own.

Most importantly, minimising the wondrous fantasy of S1 neuters its contrast with the escalating thematic darkness of the finale (from 1x5 onwards), and the impact of Roger’s death. Pullman's books are an adult story told through the eyes of a child. Lyra’s innocence and naivety in the first book is the most important journey of the trilogy. Instead, the show starts serious and thematically heavy (we’re told Lyra has world-saving importance before we even meet her) and stays that way.

Contrasting the serious tone, grounded design and poe-faced characters, the dialogue is written to cater to children. It’s horrendously blunt and pulls you out of scenes. Subtext is obliterated at every opportunity. Even in the most recent episode, 2x7, Pan asks Lyra ‘do you think you’re changing because of Will?’

I cannot understate how on the nose this line is, and how much it undercuts the themes of the final book. Instead of even a meaningful shot of Lyra looking at Will, the show treats the audience like complete idiots.

So, HDM looks and advertises itself like an adult drama and is desperate to be taken seriously by wearing its big themes on its sleeve from the start instead of letting them evolve naturally out of subtext like the books, and dedicating lots of scenes to Mrs Coulter's self-abuse

At the same time its dialogue and character writing is comparable to the Star Wars prequels, more childish than media aimed at a similar audience - Harry Potter, Doctor Who, Avatar the Last Airbender etc

DAEMONS

The show gives itself a safety net by explaining Daemons in an opening text-crawl, and so spends less time showing the mechanics of the Daemon-human bond. On the HDM subreddit, I’ve seen multiple people get to 1x5 or 6, and then come to reddit asking basic questions like ‘why do only some people have Daemons?’ or ‘Why are Daemons so important?’.

It’s not that the show didn’t answer these questions; it was in the opening text-crawl. It’s just the show thinks telling you is enough and never shows evidence to back that up. Watching a TV show you remember what you’re shown much easier than what you’re told

The emotional core of Northern Lights is the relationship between Lyra and Pan. The emotional core of HDM S1 is the relationship between Lyra and Mrs Coulter. This wouldn't be bad- it's a fascinating dynamic Ruth plays wonderfully- if it didn't override the Daemons

Daemons are only onscreen when they serve a narrative purpose. Thorne justifies this because the books only describe Daemons when they tell us about their human. On the page your brain fills the Daemons in. This doesn't work on-screen; you cannot suspend your disbelief when their absence is staring you in the face

Thorne clarified the number of Daemons as not just budgetary, but a conscious creative choice to avoid onscreen clutter. This improved in S2 after vocal criticism.

Mrs Coulter/the Golden Monkey and Lee/Hester have well-drawn relationships in S1, but Pan and Lyra hug more in the 2-hour Golden Compass movie than they do in the 8-hour S1 of HDM. There's barely any physical contact with Daemons at all.

They even cut Pan and Lyra's hug after escaping the Cut in Bolvangar. In the book they can't let go of each other. The show skips it completely because Thorne wants to focus on Mrs Coulter and Lyra.

They cut Pan and Lyra testing how far apart they can be. They cut Lyra freeing the Cut Daemons in Bolvangar with the help of Kaisa. We spent extra time with both Roger and Billy Costa, but didn't develop their bonds with their Daemons- the perfect way to make the Cut more impactful

I don't need every single book scene in the show, but notice that all these cut scenes reinforced how important Daemons are. For how plodding the show is. you'd think they could spare time for these moments instead of inventing new conversations that tell us the information they show

Daemons are treated as separate beings and thus come across more like talking pets than part of a character

The show sets the rules of Daemons up poorly. In 1x2, Lyra is terrified by the Monkey being so far from Coulter, but the viewer has nothing to compare it to. We’re retroactively told in that this is unnatural when the show has yet to establish what ‘natural’ is.

The guillotine blueprint in 1x2 (‘Is that a human and his Daemon, Pan? It looks like it.’ / ‘A blade. To cut what?’) is idiotic. It deflates S1’s main mystery and makes the characters look stupid for not figuring out what they aren’t allowed to until they did in the source material, it also interferes with how the audience sees Daemons. In the book, Cutting isn’t revealed until two-thirds of the way in (1x5). By then we’ve spent a lot of time with Daemons, they’ve become a background part of the world, their ‘rules’ have been established, and we’re endeared to them.

By showing the Guillotine and putting Daemons under threat in the second episode, the show never lets us grow attached. This, combined with their selective presence in scenes, draws attention to Daemons as a plot gimmick and not a natural extension of characters. Like Lyra, the show tells us why Daemons are important before we understand them.

Billy Costa's fate falls flat. It's missing the dried fish/ fake Daemon Tony Markos clings to in the book. Thorne said this 'didn't work' on the day, but it worked in the film. Everyone yelling about Billy not having a Daemon is laughable when most of the background extras in the same scene don't have Daemons themselves

WITCHES

The Witches are the most common complaint about the show. Thorne changed Serafina Pekkala in clever, logical ways (her short hair, wrist-knives and cloud pine in the skin)

The problem is how Serafina is written. The Witches are purely exposition machines. We get no impression of their culture, their deep connection to nature, their understanding of the world. We are told it. It is never shown, never incorporated into the dramatic action of the show.

Thorne emphasises Serafina's warrior side, most obviously changing Kaisa from a goose into a gyrfalcon (apparently a goose didn't work on-screen)

Serafina single-handedly slaughtering the Tartars is bad in a few ways. It paints her as bloodthirsty and ruthless. Overpowering the Witches weakens the logic of the world (If they can do that, why do they let the Magesterium bomb them unchallenged in 2x2?). It strips the Witches of their subtlety and ambiguity for the sake of cinematic action.

A side-effect of Serafina not being with her clan at Bolvangar is limiting our exposure to the Witches. Serafina is the only one invested in the main plot, we only hear about them from what she tells us. This poor set-up weakens the Witch subplot in S2

Lyra doesn’t speak to Serafina until 2x6. She laid eyes on her once in S1.

The dialogue in the S2’s Witch subplot is comparable to the Courasant section of The Phantom Menace.

Two named characters, neither with any depth (Serafina and Coram's dead son developed him far more than her). The costumes look ostentatious and hokey- the opposite of what the Witches should be. They do nothing but repeat the same exposition at each other, even in 2x7.

We feel nothing when the Witches are bombed because the show never invests us in what is being destroyed- with the amount of time wasted on long establishing shots, there’s not one when Lee Scoresby is talking to the Council.

BEARS

Like the Witches; Thorne misunderstands and rushes the fantasy elements of the story. The 2007 movie executed both Iofur's character and the Bear Fight much better than the show- bloodless jaw-swipe and all

Iofur's court was not the parody of human court in the books. He didn't have his fake-Daemon (hi, Billy)

An armourless bear fight is like not including Pan in the cutting scene. After equating Iorek's armour to a Daemon (Lee does this- we don’t even learn how important it is from Iorek himself, and the comparison meant less because of how badly the show set up Daemons) the show then cuts the plotpoint that makes the armour plot-relevant. This diminishes all of Bear society. Like Daemons, we're told Iorek's armour is important but it's never shown to be more than a cool accessory

GYPTIANS

Gyptians suffer from Hermoine syndrome. Harry Potter screenwriter Steve Kloves' favourite character was Hermione, and so Film!Hermoine lost most of Book!Hermoine's flaws and gained several of Book!Ron's best moments. The Gyptians are Jack Thorne's favourite group in HDM and so they got the extra screentime and development that the more complicated groups/concepts like Witches, Bears, and Daemons (which, unlike the Gyptians, carry over to other seasons amd are more important to the overall story) needed

At the same time, he changes them from a private people into an Isle of Misfit Toys. TV!Ma Costa promises they'll ‘make a Gyptian woman out of Lyra yet’, but in the book Ma specifically calls Lyra out for pretending to be Gyptian, and reminds her she never can be.

This small moment indicates how, while trying to make the show more grounded and 'adult', Thorne simultaneously made it more saccharine and sentimental. He neuters the tragedy of the Cut kids when Ma Costa says they’ll become Gyptians. Pullman's books feel like an adult story told through the eyes of a child. The TV show feels like a child's story masquerading as a serious drama.

LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA

Let me preface this by saying I genuinely really enjoy the performances in the show. It was shot in the foot by The Golden Compass' perfect casting.

The most contentious/'miscast' actor among readers is LMM. Thorne ditched the books' wise Texan for a budget Han Solo. LMM isn't a great dramatic actor (even in Hamilton he was the weak link performance-wise) but he makes up for it in marketability- lots of people tried the show because of him

Readers dislike that LMM's Lee is a thief and a scoundrel, when book-Lee is so moral he and Hester argue about stealing. Personally, I like the change in concept. Book!Lee's parental love for Lyra just appears. It's sweet, but not tied to a character arc. Done right, Lyra out-hustling Lee at his own game and giving him a noble cause to fight for (thus inspiring the moral compass of the books) is a more compelling arc.

DAFNE KEENE AND LYRA

I thought Dafne would be perfect casting. Her feral energy in Logan seemed a match made in heaven. Then Jack Thorne gave her little to do with it.

Compare how The Golden Compass introduced Lyra, playing Kids and Gobblers with a group of Gyptian kids, including Billy Costa. Lyra and Roger are chased to Jordan by the Gyptians and she makes up a lie about a curse to scare the Gyptians away.

In one scene the movie set up: 1) the Gobblers (the first we hear of them in the show is in retrospect, Roger worrying AFTER Billy is taken) 2) Lyra’s pre-existing relationship with the Gyptians (not in the show), 3) Friendship with Billy Costa (not in the book or show) 4) Lyra’s ability to befriend and lead groups of people, especially kids, and 5) Lyra’s ability to lie impressively

By comparison, it takes until midway through 1x2 for TV!Lyra to tell her first lie, and even then it’s a paper-thin attempt.

The show made Roger Lyra’s only friend. This artificially heightens the impact of Roger's death, but strips Lyra of her leadership qualities and ability to befriend anyone.

Harry Potter fans talk about how Book!Harry is funnier and smarter than Film!Harry. They cut his best lines ('There's no need to call me sir, Professor') and made him blander and more passive. The same happened to Lyra.

Most importantly, Lyra is not allowed to lie for fun. She can't do anything 'naughty' without being scolded. This colours the few times Lyra does lie (e.g. to Mrs Coulter in 1x2) negatively and thus makes Lyra out to be more of a brat than a hero.

This is a problem with telling Northern Lights from an outside, 'adult' perspective- to most adults Lyra is a brat. Because we’re introduced to her from inside her head, we think she's great. It's only when we meet her through Will's eyes in The Subtle Knife and she's filthy, rude and half-starved that we realise Lyra bluffs her way through life and is actually pretty non-functional

Thorne prioritises grounded human drama over fantasy, and so his Lyra has her love of bears and witches swapped for familial angst. (and, in S2. angst over Roger). By exposing Mrs Coulter as her mother early, Thorne distracts TV!Lyra from Book!Lyra’s love of the North. The contrast between wonder and reality made NL's ending a definitive threshold between innocence and knowledge. Thorne showed his hand too early.

Similarly, TV!Lyra doesn’t have anywhere near as strong an admiration for Lord Asriel. She calls him out in 1x8 (‘call yourself a Father’), which Book!Lyra never would because she’s proud to be his child. From her perspective, at this point Asriel is the good parent.

TV!Lyra’s critique of Asriel feels like Thorne using her as a mouthpiece to voice his own, adult perspective on the situation. Because Lyra is already disappointed in Asriel, his betrayal in the finale isn’t as effective. Pullman saves the ‘you’re a terrible Father’ call-out for the 3rd book for a reason; Lyra’s naive hero-worship of Asriel in Northern Lights makes the fall from Innocence into Knowledge that Roger’s death represents more effective.

So, on TV Lyra is tamer, angstier, more introverted, less intelligent, less fun and more serious. We're just constantly told she's important, even before we meet her.

MRS COULTER (AND LORD ASRIEL)

Mrs Coulter is the main character of the show. Not Lyra. Mrs Coulter was cast first, and Lyra was cast based on a chemistry test with Ruth Wilson. Coulter’s character is given lots of extra development, where the show actively strips Lyra of her layers.

To be clear, I have no problem with developing Mrs Coulter. She is a great character Ruth Wilson plays phenomenally. I do have a problem with the show fixating on her at the expense of other characters.

Lyra's feral-ness is given to her parents. Wilson and McAvoy are more passionate than in the books. This is fun to watch, but strips them of subtlety- you never get Book!Coulter's hypnotic allure from Wilson, she's openly nasty, even to random strangers (in 2x3 her dismissal of the woman at the hotel desk felt like a Disney villain).

Compare how The Golden Compass (2007) introduced Mrs Coulter through Lyra’s eyes, with light, twinkling music and a sparkling dress. By contrast, before the show introduces Coulter it tells us she’s associated with the evil Magisterium plotting Asriel’s death- “Not a word to any of our mutual friends. Including her.” Then she’s introduced striding down a corridor to imposing ‘Bad Guy’ strings.

Making Mrs Coulter’s villainy so obvious so early makes Lyra look dumber for falling for it. It also wastes an interesting phase of her character arc. Coulter is rushed into being a ’conflicted evil mother’ in 2 episodes, and stays in that phase for the rest of the show so far. Character progression is minimised because she circles the same place.

It makes her one-note. It's a good note (so much of the positive online chatter is saphiccs worshiping Ruth Wilson) but the show also worships her to the point of hindrance- e.g. take a shot every time Coulter walks slow-motion down a corridor in 2x2

The problem isn’t the performances, but how prematurely they give the game away. Just like the mysteries around Bolvangar and Lyra’s parentage. Neither Coulter or Asriel have much chance to use their 'public' faces.

This is part of a bigger pacing problem- instead of rolling plot points out gradually, Thorne will stick the solution in front of you early and then stall for time until it becomes relevant. Instead of building tension this builds frustration and makes the show feel like it's catching up to the audience. This also makes the characters less engaging. You've already shown Mrs Coulter is evil/Boreal is in our world/Asriel wants Roger. Why are you taking so long getting to the point?

PACING AND EDITING

This show takes forever to make its point badly.

Scenes in HDM tend to operate on one level- either 'Character Building,' 'Exposition,' or 'Plot Progression'.

E.g. Mary's introduction in 2x2. Book!Mary only listens to Lyra because she’s sleep and caffeine-deprived and desperate because her funding is being cut. But the show stripped that subtext out and created an extra scene of a colleague talking to Mary about funding. They removed emotional subtext to focus on exposition, and so the scene felt empty and flat.

In later episodes characters Mary’s sister and colleagues do treat her like a sleep-deprived wreck. But, just like Lyra’s lying, the show doesn’t establish these characteristics in her debut episode. It waits until later to retroactively tell us they were there. Mary’s colleague saying ‘What we’re dealing with here is the fact that you haven’t slept in weeks’ is as flimsy as Pan joking not lying to Mary will be hard for Lyra.

Rarely does a scene work on multiple levels, and if it does it's clunky- see the exposition dump about Daemon Separation in the middle of 2x2's Witch Trial.

He also splits plot progression into tiny doses, which destroys pacing. It's more satisfying to focus on one subplot advancing multiple stages than all of them shuffling forward half a step each episode.

Subplots would be more effective if all the scenes played in sequence. As it is, plotlines can’t build momentum and literal minutes are wasted using the same establishing shots every time we switch location.

The best-structured episodes of S1 are 1x4, 1x6, and 1x8. This is because they have the fewest subplots (incidentally these episodes have least Boreal in them) and so the main plot isn’t diluted by constantly cutting away to Mrs Coulter sniffing Lyra’s coat or Will watching a man in a car through his window, before cutting back again.

The best-written episode so far is 2x5. The Scholar. Tellingly, it’s the only episode Thorne doesn’t have even a co-writing credit on. 2x5 is well-paced, its dialogue is more naturalistic, it’s more focused, it even has time for moments of whimsy (Monkey with a seatbelt, Mrs Coulter with jeans, Lyra and Will whispering) that don’t detract from the story.

Structurally, 2x5 works because A) it benches Lee’s plotline. B) The Witches and Magisterium are relegated to a scene each. And C) the Coulter/Boreal and Lyra/Will subplots move towards the same goal. Not only that, but when we check in on Mary’s subplot it’s through Mrs Coulter’s eyes and directly dovetails into the main action of the episode.

2x5 has a lovely sense of narrative cohesion because it has the confidence to sit with one set of characters for longer than two scenes at a time.

HDM also does this thing where it will have a scene with plot A where characters do or talk about something, cut away to plot B for a scene, then cut back to plot A where the characters talk about what happened in their last scene and painstakingly explain how they feel about it and why

Example: Pan talking to Will in 2x7 while Lyra pretends to be asleep. This scene is from the 3rd book, and is left to breathe for many chapters before Lyra brings it up. In the show after the Will/Pan scene they cut away to another scene, then cut back and Lyra instantly talks about it.

There’s the same problem in 2x5: After escaping Mrs Coulter, Lyra spells out how she feels about acting like her

The show never leaves room for implication, never lets us draw our own conclusions before explaining what it meant and how the characters feel about it immediately afterwards. The audience are made passive in their engagement with the characters as well as the world

LORD BOREAL, JOHN PARRY AND DIMINISHING RETURNS

At first, Boreal’s subplot in S1 felt bold and inspired. The twist of his identity in The Subtle Knife would've been hard to pull off onscreen anyway. As a kid I struggled to get past Will's opening chapter of TSK and I have friends who were the same. Introducing Will in S1 and developing him alongside Lyra was a great idea.

I loved developing Elaine Parry and Boreal into present, active characters. But the subplot was introduced too early and moved too slowly, bogging down the season.

In 1x2 Boreal crosses. In 1x3 we learn who he's looking for. In 1x5 we meet Will. In 1x7 the burglary. 1 episode worth of plot is chopped up and fed to us piecemeal across many. Boreal literally stalls for two episodes before the burglary- there are random 30 second shots of him sitting in a car watching John Parry on YouTube (videos we’d already seen) completely isolated from any other scenes in the episode

By the time we get to S2 we've had 2 seasons of extended material building up Boreal, so when he just dies like in the books it's anticlimactic. The show frontloads his subplot with meaning without expanding on its payoff, so the whole thing fizzles out.

Giving Boreal, the secondary villain in literally every episode, the same death as a background character in about 5 scenes in the novels feels cheap. It doesn’t help that, after 2x5 built the tension between Coulter and Boreal so well, as soon as Thorne is passed the baton in 2x6 he does little to maintain that momentum. Again, because the subplot is crosscut with everything else the characters hang in limbo until Coulter decides to kill him.

I’ve been watching non-book readers react to the show, and several were underwhelmed by Boreal’s quick, unceremonious end.

Similarly, the show builds up John Parry from 1x3 instead of just the second book. Book!John’s death is an anticlimax but feels narratively justified. In the show, we’ve spent so much extra time talking about him and then being with him (without developing his character beyond what’s in the novels- Pullman even outlined John’s backstory in The Subtle Knife’s appendix. How hard would it be to add a flashback or two?) that when John does nothing in the show and then dies (he doesn’t even heal Will’s fingers like in the book- only tell him to find Asriel, which the angels Baruch and Balthamos do anyway) it doesn’t feel like a clever, tragic subversion of our expectations, it feels like a waste that actively cheapens the audience’s investment.

TL;DR giving supporting characters way more screentime than they need only, to give their deaths the same weight the books did after far less build up makes huge chunks of the show feel less important than they were presented to be.

FRUSTRATINGLY LIMITED EXPANSION AND NOVELLISTIC STORYTELLING

Thorne is unwilling to meaningfully develop or expand characters and subplots to fit a visual medium. He introduces a plot-point, invents unnecessary padding around it, circles it for an hour, then moves on.

Pullman’s books are driven by internal monologue and big, complex theological concepts like Daemons and Dust. Instead of finding engaging, dynamic ways to dramatise these concepts through the actions of characters or additions to the plot, Thorne turns Pullman’s internal monologue into dialogue and has the characters explain them to the audience

The novels’ perspective on its characters is narrow, first because Northern Lights is told only from Lyra’s POV, and second because Pullman’s writing is plot-driven, not character-driven. Characters are vessels for the plot and themes he wants to explore.

This is a fine way of writing novels. When adapting the books into a longform drama, Thorne decentralised Lyra’s perspective from the start, and HDM S1 uses the same multi-perspective structure that The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass do, following not only Lyra but the Gyptians, Mrs Coulter, Boreal, Will and Elaine etc

However, these other perspectives are limited. We never get any impression of backstory or motivation beyond the present moment. Many times I’ve seen non-book readers confused or frustrated by vague or non-existent character motivations.

For example, S1 spends a lot of time focused on Ma Costa’s grief over Billy’s disappearance, but we never see why she’s sad, because we never saw her interact with Billy.

Compare this to another show about a frantic mother and older brother looking for a missing boy. Stranger Things uses only two flashbacks to show us Will Byers’ relationships with his family: 1) When Joyce Byers looks in his Fort she remembers visiting Will there. 2) The Clash playing on the radio reminds Jonathan Byers of introducing Will to the song.

In His Dark Materials we never see the Costas as a happy family- 1x1’s Gyptian ceremony focuses on Tony and Daemon-exposition. Billy never speaks to his mum or brother in the show

Instead we have Ma Costa’s empty grief. The audience has to do the work (the bad kind) imagining what she’s lost. Instead of seeing Billy, it’s just repeated again and again that they will get the children back.

If we’re being derivative, HDM had the chance to segway into a Billy flashback when John Faa brings one of his belongings back from a Gobbler safehouse in 1x2. This is a perfect The Clash/Fort Byers-type trigger. It doesn’t have to be long- the Clash flashback lasted 1:27, the Fort Byers one 55 seconds. Just do something.

1x3 beats into us that Mrs Coulter is nuts without explaining why. Lots of build-up for a single plot-point. Then we're told Mrs Coulter's origin, not shown. This is a TV show. Swap Boreal's scenes for flashbacks of Coulter and Asriel's affair. Then, when Ma Costa tells Lyra the truth, show the fight between Edward Coulter and Asriel.

To be clear, Thorne's additions aren’t fundamentally bad. For example, Will boxing sets up his struggle with violence. But it's wasted. The burglary/murder in 1x7 fell flat because of bad editing, but the show never uses its visual medium to show Will's 'violent side'- no change in camera angle, focus, or sound design, nothing. It’s just a thing that’s there, unsupported by the visual language of the show

The Magisterium scenes in 2x2 were interesting. We just didn't need 5 of them; their point could be made far more succinctly.

In 2x6 there is a minute-long scene of Mary reading the I Ching. Later, there is another scene of Angelica watching Mary sitting somewhere different, doing the SAME THING, and she sees an Angel. Why split these up? It’s not like either the I Ching or the Angels are being introduced here. Give the scene multiple layers.

Thorne either takes good character moments from the books (Lyra/Will in 2x1) or uses heavy-handed exposition that reiterates the same point multiple times. This hobbles the Witches (their dialogue in 2x1, 2 and 3 literally rephrases the same sentiment about protecting Lyra without doing anything). Even character development- see Lee monologuing his and Mrs Coulter's childhood trauma in specific detail in 2x3

This is another example of Thorne adding something, but instead of integrating it into the dramatic action and showing us, it’s just talked about. What’s the point of adding big plot points if you don’t dramatise them in your dramatic, visual medium? In 2x8, Lee offhandedly mentions playing Alamo Gulch as a kid.

I’m literally screaming, Jack, why the flying fuck wasn’t there a flashback of young Lee and Hester playing Alamo Gulch and being stopped by his abusive dad? It’s not like you care about pacing with the amount of dead air in these episodes, even when S2’s run 10 minutes shorter than S1’s. Lee was even asleep at the beginning of 2x3, Jack! He could’ve woken from a nightmare about his childhood! It’s a little lazy, but better than nothing.

There’s a similar missed opportunity making Dr Lanselius a Witchling. If this idea had been introduced with the character in 1x4, it would’ve opened up so many storytelling possibilities. Linking to Fader Coram’s own dead witchling son. It could’ve given us that much-needed perspective on Witch culture. Imagine Lanselius’ bittersweet meeting with his ageless mother, who gave him up when he reached manhood. Then, when the Magisterium bombs the Witches in 2x2, Lanselius’ mother dies so it means something.

Instead it’s only used to facilitate an awkward exposition dump in the middle of a trial.

The point of this fanfic-y ramble is to illustrate my frustration with the additions; If Thorne had committed and meaningfully expanded and interwoven them with the source material, they could’ve strengthened its weakest aspect (the characters). But instead he stays committed to novelistic storytelling techniques of monologue and two people standing in a room talking at each other

(Seriously, count the number of scenes that are just two people standing in a room or corridor talking to each other. No interesting staging, the characters aren’t doing anything else while talking. They. Just. Stand.)

SEASON 2 IMPROVEMENTS

S2 improved some things- Lyra's characterisation was more book-accurate, her dynamic with Will was wonderful. Citigazze looked incredible. LMM won lots of book fans over as Lee. Mary was brilliantly cast. Now there are less Daemons, they're better characterised- Pan gets way more to do now and Hester had some lovely moments.

I genuinely believe 2x1, 2x3, 2x4 and 2x5 are the best HDM has been.

But new problems arose. The Subtle Knife lost the central, easy to understand drive of Northern Lights (finding the missing kids) for lots of smaller quests. As a result, everyone spends the first two episodes of S2 waiting for the plot to arrive. The big inciting incident of Lyra’s plotline is the theft of the alethiometer, which doesn’t happen until 2x3. Similarly, Lee doesn’t search for John until 2x3. Mrs Coulter doesn’t go looking for Lyra until 2x3.

On top of missing a unifying dramatic drive, the characters now being split across 3 worlds, instead of the 1+a bit of ours in S1, means the pacing/crosscutting problems (long establishing shots, repetition of information, undercutting momentum) are even worse. The narrative feels scattered and incohesive.

These flaws are inherent to the source material and are not the show’s fault, but neither does it do much to counterbalance or address them, and the flaws of the show combine with the difficulties of TSK as source material and make each other worse.

A lot of this has been entitled fanboy bitching, but you can't deny the show is in a bad place ratings-wise. It’s gone from the most watched new British show in 5 years to the S2 premiere having a smaller audience than the lowest-rated episode of Doctor Who Series 12. For comparison, DW's current cast and showrunner are the most unpopular since the 80s, some are actively boycotting it, it took a year-long break between series 11 and 12, had its second-worst average ratings since 2005, and costs a fifth of what HDM does to make. And it's still being watched by more people.

Critical consensus fluctuates wildly. Most laymen call the show slow and boring. The show is simultaneously too niche and self-absorbed to attract a wide audience and gets just enough wrong to aggravate lots of fans.

I’m honestly unsure if S3 will get the same budget. I want it to, if only because of my investment in the books. Considering S2 started filming immediately after S1 aired, I think they've had a lot more time to process and apply critique for S3. On the plus side, there's so much plot in The Amber Spyglass it would be hard to have the same pacing problems. But also so many new concepts that I dread the exposition dumps.

#His Dark Materials#his dark materials hbo#jack thorne#mrs coulter#ruth wilson#lyra silvertongue#philip pullman#northern lights#the subtle knife#the amber spyglass#the golden compass#hdm#hdm spoilers#bbc#lin-manuel miranda#daemon#writing#book adaptation#hbo#dafne keen#james macavoy#lord asriel#pantalaimon#lee scoresby

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Colin Morgan Interview with Edge Media Network about Benjamin - UPDATED

I am reblogging this because, after the author was made aware of an error in the posting of his article (if anyone clicked through to read it on the site, there was a whole question and answer that was repeated), the error was corrected and another three questions and answers were added! I am correcting it here, but they were very interesting, so I suggest you read the full article again!

I shall post the link at the bottom, but I wanted to type it out so that non-English speakers could more easily translate it. (This article was listed in their “Gay News” section of the site, hence the focus on the gay roles.)

British Actor Colin Morgan: How the Queerly Idiosyncratic ‘Benjamin’ Spoke to Him

by Frank J. Avelia

In writer-director Simon Amstell’s sweet, idiosyncratic, semi-autobiographical comedy, “Benjamin,” Colin Morgan plays the titular character, an insecure filmmaker trying to resuscitate his waning career (at least it’s waning in his mind) after one major cine-indie success. Benjamin is also doing his best to navigate a new relationship with a young French musician (Phenix Brossard of “Departures”).

Thanks to the truly endearing, multifaceted talents of Morgan, Benjamin feels like an authentic creation--one that most audiences can empathize with. Sure, he’s peculiar, has a legion of self-esteem issues and an almost exasperating need for acceptance as well as an inconvenient talent to self-sabotage the good in his life. But who can’t relate to some or all of that?

“Benjamin” is one of the better queer-themed films to come out in recent years, in large part because it eschews emphasis on the queer nature of the story. Instead, the film is a fascinating character study with Morgan slowly revealing layers and unpacking Benjamin’s emotional baggage.

Morgan is a major talent who has been appearing across mediums in Britain for many years. His London theatre debut was in DBC Pierre’s satire, “Vernon God Little” (2007), followed by the stage adaptation of Pedro Almodovar’s “All About My Mother” (2007), opposite Diana Rigg. Numerous and eclectic stage work followed (right up until the Corona shutdown) including Pedro Miguel Rozo’s “Our Private Life” (2011), where he played a bipolar gay, Jez Butterworth’s dark comedy, “Mojo” (2013), Arthur Miller’s “All My Sons” opposite Sally Field (2019), and Caryl Churchill’s “A Number” (2020), to name a few.

His TV work includes, “Merlin” (playing the wizard himself), “Humans” and most recently, in a very memorable episode of “The Crown”. Onscreen he can be seen in “Testament of Youth”, “Legend” with Tom Hardy, “Snow White and the Huntsman” and Rupert Everett’s take on Oscar Wilde, “The Happy Prince.”

He’s played a host of gay roles in the past on stage, screen and TV.

EDGE recently interviewed the star of “Benjamin” about the new film and his career.

Why Benjamin?

EDGE: What drew you to this project and were you part of its development?

Colin Morgan: It’s always the strength of the script for me on any project and Simon’s script was just so well observed, he managed to combine humor and poignancy in delicate measure and when I first read it I found myself being both tickled and touched. Then reading it again and from “the actor” POV... I knew it would be a real challenge and uncharted territory for me to explore. I auditioned for Simon and we tried it in different ways and then when I was lucky enough for Simon to want me on board, we began to work through the script together, because it was clear that this was going to be a very close working relationship... it was important for the level of trust to be high.

EDGE: I appreciated that this was a queer love story where the character’s queerness wasn’t the main focus. Was that also part of the allure of the project?

CM: I think Benjamin’s sexuality is just quite naturally who he is and therefore that’s a given, we’re on his journey to find meaning and love and there’s certainly a freshness to what Simon has written in not making sexuality the main focus.

Great chemistry

EDGE: Can you speak a but about the process involved in working with Amstell on the character and his journey?

CM: Simon and me worked very closely over a period of weeks, at that time prior to shooting I was doing a theatre project not far from where he lived so I would go to him and rehearse and discuss through the whole script all afternoon before going to do the show that night, so that worked out well. It’s so personal to Simon, and to have had him as my guide and source throughout was fantastic because I could ask him all the questions and he could be the best barometer for the truth of the character; a rare opportunity for an actor and one that was so essential for building Benjamin. But ultimately Simon wanted Benjamin to emerge from somewhere inside me and he gave me so much freedom to do that also.

EDGE: You had great chemistry with Phenix Brossard. Did you get to rehearse?

CM: Phenix is fantastic, Simon and me did chemistry reads with a few different actors who were all very good but Phenix just had an extra something we felt Benjamin would be drawn to. We did a little bit of rehearsal together but because it was a relationship that was trying to find itself there was a lot of room for spontaneity and uncertainty between us, which is what the allure of a new relationship is all about, the excitement and fear.

Liberating process

EDGE: Did your process meld with Amstell’s?

CM: I’ve said this a lot before and it’s true, Simon is one of the best directors I’ve worked with. Everything he created before shooting and then maintained on set was special. We always did improvised versions of most scenes and always the scripted version too. It was such a creative and liberating process. That is exactly the way I love to work. And for a director to maintain that level of bravery, trust and experimental play throughout the whole shoot stands as one of the most rewarding shooting experiences I’ve had.

EDGE: When I spoke with Rupert Everett about “The Happy Prince,” he very proudly boasted about his ensemble. Can you speak about working with Rupert as he balanced wearing a number of creative hats?

CM: Again, this was an extremely rewarding project to work on and quite a similar relationship as with Simon in the respect that Rupert was the writer/director and Oscar Wilde is so personal to him. And then we also had many scenes together in front of the camera, so Rupert and me had a real 3D experience together. It was a long time in the making. I was on board, I think, two years before we actually got shooting so I had a lot of time to work with Rupert and rehearse. He really inspired me, watching him wear all the different creative hats, such a challenging and difficult job/jobs to achieve and he really excelled--plus we just got on very well.

Playing queer roles

EDGE: You haven’t shied away from playing queer roles. Do you think we’re moving closer to a time when a person’s sexual orientation is of little consequence to the stories being told, or should it always matter? Or perhaps we need to continue to evolve as a culture for it to matter less or not at all...

CM: That’s a hard question to answer, I think certainly the shift in people’s attitudes has changed considerably for the better compared to 40 years ago, but there will always be resistance to change and acceptance from individuals and groups whether it be sexuality, religion, race, gender--we’re seeing it every day.

Evolution is, of course, inevitable, but if we can learn from the past as we evolve that would be the ideal. Unfortunately, we rarely do learn, and history repeats itself.

EDGE: You were featured prominently in one of my favorite episodes of the “The Crown” (”Bubbikins”) as the fictional journo John Armstrong. Can you speak a bit about working on the show and with the great Jane Lapotaire?

CM: I had an exceptionally good time working on “The Crown.” Director Benjamin Caron, especially, was so prepared and creative, and made the whole experience so welcoming and inclusive. It was an incredibly happy set, with extremely talented people in every department, and I admired the ethos of the whole production and have no doubt that’s a huge ingredient to its success, along with Peter Morgan’s incredible writing.

I was also a fan of the show, and it was an honor to be part of the third season. And I can’t say enough amazing things about Jane Lapotaire. We talked a lot in between filming, and I relished every moment of that.

EDGE: You’ve done a ton of stage work. Do you have a favorite role you’ve played onstage?

CM: I’ve been so lucky with the theatre work I’ve done, to work with such special directors and work in wonderful theatres in London. I’ve worked at the Old Vic and The Young Vic twice each, and they’re always special to me. Ian Rickson is a liberating director, who I love. It’s hard to pick a favorite, because the roles have all been so different and presented different challenges, but, most recently, doing “A Number,” playing three different characters alongside Roger Allam and directed by Polly Findlay, was a really treasured experience, and I never tired of doing that show, every performance was challenging as it was.

Miss the rehearsal room

EDGE: You were doing “A Number” earlier this year. Did you finish your run before the lockdown/shutdown?

CM: Just about! We had our final performance, and then lockdown happened days later. I feel very sorry for the productions that didn’t get the sense of completion of finishing a run. I mean, finishing a full run leaves you in a kind of post-show void anyway, even though you know it’s coming, so to not know it’s coming and have it severed must be even more of a void.

Memories of performing just months ago seem like such an unattainable thing in this COVID world right now. I can’t tell you how much I’m hoping we get back to some semblance of live performance.

EDGE: What was it like to appear onstage opposite Dame Diana Rigg in “All About My Mother?”

CM: Well, I think “iconic” is an apt word for both the experience of working with Diana and the lady herself. In between scenes backstage we used to talk a lot and we got told off for talking too loudly, so Diana began to teach me sign language and we would spell out words to each other, maybe only getting a couple of sentences to each other before she was due on stage and I had to get into position for my next entrance-- we did a radio play together two years ago and she remembered, she said, “Do you remember A-E-I-O-U?” signing out the letters with her hands.

EDGE: None of us knows the future in terms of the pandemic and when we might return to making theatre. I’m a playwright myself and find it all supremely frustrating but I’m trying to remain hopeful! Where are you right now in terms of the standstill we are in and what the future might hold?

CM: Yes, I’m so worried for theatre. It’s a devastating blow. I’m sure as a playwright, you know that the creative spirit in individuals hasn’t been diminished by this virus. People are creating important art in this crisis but we need the platforms to present it and bring people to some light again out of this really scary period, but it needs to be safe and it’s a worrying time. The virtual theatre approach must be looked at I think. We need to experiment and find new paths at least for the time being. I’m involved in developing some things right now and how we can work on things in both an isolated and collaborative way. It’s entirely counterintuitive to what the family-feel and close bond of a group in a rehearsal room is like-- I miss the rehearsal room so much!-- but we can’t sit still, we must create and we must act.

What’s in a role?

EDGE: Looking back on the great success of “Merlin,” what are your takeaways from that experience?

CM: Some of the most treasured memories of my life will forever be connected to “Merlin,” the cast, crew, production, everyone! The invaluable training of being in front of a camera every day! The chance to inhabit a character and live with him for five seasons! There’s too much to list and words probably won’t do justice anyway, but I’m truly grateful for everything the show gave me.

EDGE: How do you select the roles you play?

CM: I guess they select me in a way. I can’t play a role unless it speaks to me and provokes me in some way, but ultimately it’s the characters that I have a fear about playing, not knowing how I’m going to enter into the process of living them, when I don’t have all the answers it’s a good indicator of a character I must play. If I have all the answers, there’s less scope for exploration and discovery which isn’t as interesting for me.

Link here

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

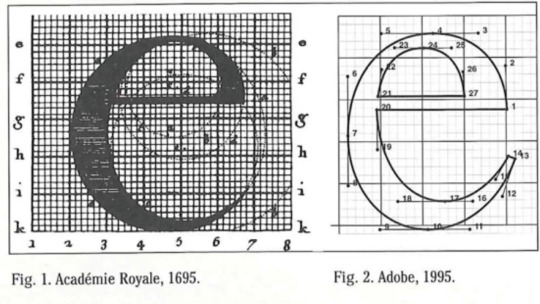

What Makes a Book?

I want to take a break from my novel and dive into a history lesson of books themselves. Why? Well first of all, I will be honest, this blog is for an assignment. But also because the way books have evolved over the last 5,000+ years is fascinating!

Of course no one ever really thinks about THE book, just the fact that the story within its pages--the mystery, the romance, whatever they happen to be enjoying--is a great read (or maybe not so great), but have they ever wondered what materials the book is made from? Who invented it? How the book has become one of the most common and most used items of all time?

No. Of course they didn't wonder any of those things. And if they did, they probably didn't take the time to research any of these burning questions, either.

How great, then, that I wrote this post?! Today is your lucky day! (Also, it is a good thing that Keith Houston, author of Shady Characters, decided to write a whole book about it (1).) I'm going to use the pages of a classic tale to explain some cool things you probably never noticed while reading a book before.

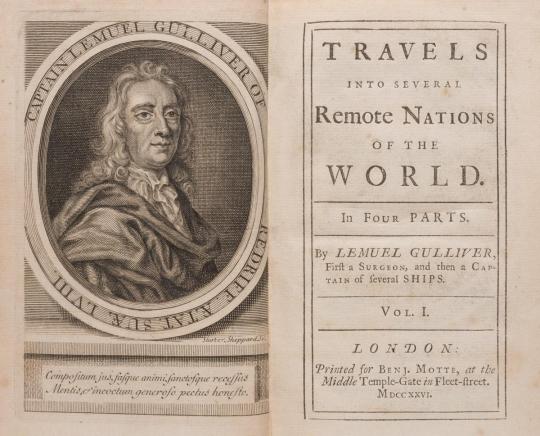

Gulliver’s Travels was originally published in London in 1726 by Benjamin Motte. The author, Jonathan Swift, used it to satirize London society and culture, poking holes at the social hierarchies and systems, basically making out everyone living in the 18th century to be fools--but mostly the wealthy and those who were obsessed with scientific progression (2). If you have not read it, I highly encourage adding it to your reading list, or at the very least there is a 2010 movie, featuring Jack Black as Gulliver, that you could watch. (It’s Jack Black, okay?)

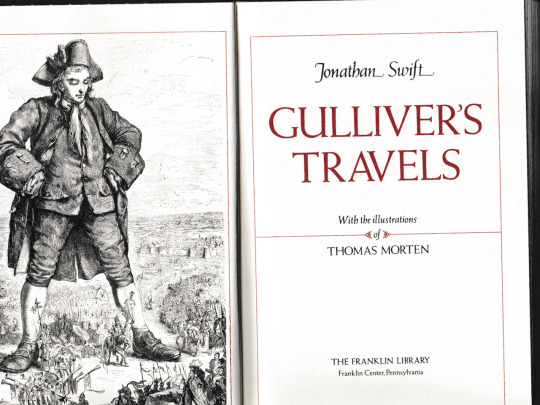

This 2 page spread of Gulliver's Travels pictured above is actually found in The Franklin Library edition from Franklin Center, Pennsylvania, published in 1979. This is the first printing of this edition, and its pages, the way it is printed, and the way it is bound and presented, are all features of the modern 20-21st century book, plus some extra bells and whistles. The most interesting qualities come from the publishers themselves who specifically design their books to be very snazzy--meant for collectors’ editions! They include different kinds of leather binding, exclusive illustrations, and may be signed or part of a particular series specific to a certain author or genre (3). This makes the books published here very valuable and sought after.

Gulliver’s Travels is hardcover. Specifically, “fine leather in boards.” This means the spine and front and back boards (or cover) of the book are bound in leather. The leather is fine and and delicate and able to be decorated and engraved upon.4 Above you can see how fancy it looks with the gilt gold engravements. Even its pages are gilt!

This picture shows more clearly the binding, and of course the spine, which is “hubbed,” or ridged, for added texture.

At this point you may have notice that this version is much different than the original published in 1726. That is because over time, the materials involved in making books have changed slightly or the processes have become more efficient or cost worthy, etc. Either way, the anatomy of the book has not wavered. Keith Houston has dissected the book into certain components and we can see them in each book we read:

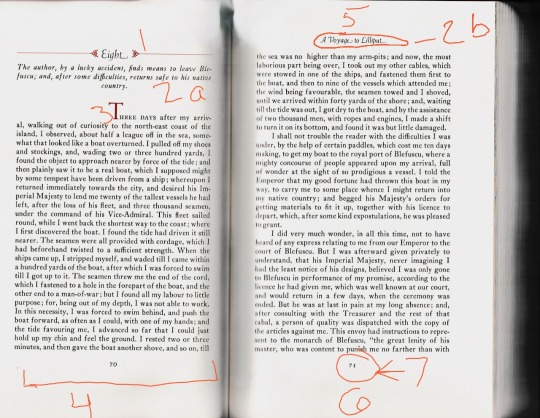

I have attempted to label it as best as I can, so hopefully you can follow along:

Chapter Number

a) this seems to be a description, more or less of the chapter, or the Chapter Title. b) “A Voyage to Lilliput” seems much more title-like to me, although this is technically called the “Recto Running Head.” The recto running head is a condensed or abbreviated chapter title, repeating on every right-side page to the end of the chapter.

Drop Cap. This would be the first letter of the first word of a chapter, which is usually exaggerated or embellished in some way.

Opener Text

Head Margin - the space between the top of the page and text

Foot Margin - the space between the bottom of the page and text

Folio - page number

It has taken quite a while for books to become so sophisticated. Because it was published in 1726, Gulliver's Travels is technically what you could call "modern" in terms of how long ago books began their journey to what they are today, but even between 1726 and 1979 the quality has improved. This edition published by Franklin Library is a perfect model for the modern book of today.

The 2 page spread we analyzed above is made from paper. But books were not always made with paper, or even in the book form, bound with anything at all, and they were not printed either. They were written by hand on papyrus.

Papyrus was the first material used as "paper" beginning in Egypt. The reeds were stripped, strung side by side and pressed together. Papyrus was durable and sturdy, and the water of the Nile was abundant in aluminum sulfate, which brightened it so that writing and scribbles could be seen better. There is no particular origin of when Papyrus had first been invented but it must have been around the end of the 4th millenium BCE (Houston 4).

Parchment is made from animal skin that has been soaked, scrubbed, dried, and stretched for days and days, creating a more flexible, yet still durable, material for writing. It was also thinner and could be made "cleaner" and brighter by chemical means. Religion heavily influenced its distribution; some parchment use was literally banned because the type of animal skin used to make it wasn't considered "holy" or "good." For example, the lamb or a calf was acceptable, but how dare you use parchment made from goat skin? What is wrong with you?

Besides the fact that parchment is kind of gross if you think about it (although to be fair, you can’t be too choosy in times right before the common era), it was also expensive to keep certain cattle only for paper making, and the reliability of having new cattle at the time you may need more paper was not very high.

Paper was first introduced in China. It is made from bits of cloth and rags soaked in water, and after breaking down into pulp, strained through a wire grate and pressed to dry. Fun fact-- the Rhar West Art Museum in Manitowoc, Wisconsin has held classes showing how to make paper using this exact process.

There is a trend here: the materials used to make paper (and papyrus and parchment before it) become scarce or too expensive, or they are just not “good enough.” People want their paper thin and smooth, but still strong and durable; crisp and bright, but still able to last years and years without crumbling. There have been times that processes used to ensure these preferred qualities of paper included using chemicals that ended up negatively affecting some other quality. For example, the paper would be white as snow, yet the chemical that did this broke down the natural adhesives which kept the paper intact.

Have you heard that paper grows on trees? Well, that is partly true since after rags and cloths were nowhere to be found (unless people were about to start donating the shirts off their backs), wood pulp has now since been used... the higher the demand for paper, the greater demand for those materials used for its creation.

This brings us to printing side of things. The first ways of printing weren’t of how we think of it now. Even before papyrus, people were still writing and making inscriptions on pretty much anything they could get their hands on. The earliest forms of writing were rather indentations or markings on clay tablets. Found across the Middle East, it is a cuneiform script of the Sumerian people from 3300 BCE (Houston 79).

Similarly, the Egyptians were also keen on developing their own writing system which today we recognize as hieroglyphs. A lot of these were found carved on the walls of tombs but also began to be used on papyrus in 2600 BCE (Houston 82-83).

The Egyptians celebrated their scribes and believed those who wrote with brush and ink on papyrus to be channeling power--that it was a gift from the gods--”wielded with respect and humility” (Houston 87). The hieroglyphs not only showed the intention of the writer, visually, but often the picture would be associated with or connected to certain sounds which emerged more formal use of letters as time went on.

The alphabet we use today can be traced back to the Phoenician alphabet (used by the Egyptians) which had evolved into the Greek and then Roman alphabets (Houston 91-92). At this point in time, scribes were using water based ink which was fine for papyrus, but during the transition to parchment they realized that ink smudges quite a bit. This led to the creation of iron gall ink that would darken and adhere to the parchment as it dried due to its chemical makeup in contact with oxygen in the air.

Jump ahead to 1400s and we are with Johannes Gutenberg and the printing press! One thing Keith Houston make sure to mention is that although Gutenberg invented the printing press itself, to help moveable type and mass printing, the idea of printing had not been new. Clay pieces used as stamps and similar objects had been excavated and dated back thousands of years before the clay inscribed cuneiform tablets were made. And a primitive version of a sort of printing press is mentioned being made by a man named Bi Sheng during the reign of Qingli from 1041-1048 AD (Houston 110). Obviously nothing great came from it, most likely because he was of unofficial position. Even so, movable type was still possible, although painstakingly slow with wooden blocks used as stamps. This was common for the next few hundred years in China.

Even though Gutenberg's press completely revolutionized the transmission of knowledge, it was still quite slow in comparison to the versions which came after, only being able to print 600 characters a day (Houston 118). From Gutenberg's printing press came other types of presses that improved the speed or efficiency of movable type immensely. These all came after the original publication of Guliver's Travels, starting in the early 1800s with the Columbian press, eventually the Linotype, and then lack of precision called for the Monotype, which could produce 140 wpm (Houston 149).

The 2 page spread above then, could possibly have been printed by the Linotype, but most likely, however, the Monotype, which is the more accurate of the two. Another possibility could be "sophisticated photographic and 'lithographic' techniques" or "'phototypsetting'" (Houston 151). Houston mentions that the printing press age has died and now faces a digital future.

I'm at my 10 image limit which means I better wrap this up with some interesting facts about bookbinding. On BIBLIO.com I was trying to see exactly what "fine leather in boards" meant which is apparently how Gulliver's Travels is bound. I didn't find any phrase that matched, but from my understanding, the leather is very supple and pliable, which is why it was able to be gilt with gold, and it was able to form nicely to the hubbing on the spine.

The website also explains that the first "book binding" was technically just putting the pieces of paper or parchment together and pressing them between two boards. Literally. Like just setting them on a board and putting another board on top of that. Eventually leather was introduced, first as a cord wrapped around the book to keep the boards in place. As time progressed, the practice was improved and perfected so it was less crude. This involved the creation of the "spine" where the pages meet together and can therefore open and close in a v shape without flying away.

This website helped explain some of the other embellishments and extra flair that can be added to a book's binding. It mostly goes over leather binding which is from most animal skin but there is a unique leather bound book that can be bound with seal skin. Some of the books on the website are so expensive because of the materials they are bound with and the effects that have been created in the cover, for example, Benjamin Franklin's observations on electricity, which has had acid added to the page, discoloring it for a lightning strike effect, and includes a key to represent his famous experiment.

Gulliver's Travels, although not quite so fancy, is still a very beautifully bound book with decorated endpapers, meaning the inside cover is laden with designed paper rather than boring white or some other neutral color.

I hope you found this journey of the book as interesting and as exciting as I did while writing this post! You must really love books because even my attention span isn't this long. I will admit I took at least 3 different breaks.

I'm back to my novel for now, thanks for listening😎

Bibliography

Houston, Keith--Author of Shady Characters, which I used extensively in my TikTok “history of punctuation” project--also wrote -> The BOOK - a cover-to-cover exploration of the most powerful object of our time, 2016.

British Library Website -> works -> “Gulliver’s Travels overview”

Masters, Kristin. “Franklin Library Editions: Ideal for Book Collectors?” Books Tell You Why, 2017 (blog).

BIBLIO.com -> “Leather Binding Terminology and Techniques”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello Freddy and Handeemen Friends Chapter 1

Another big day of filming has officially come to a close for those who worked at the studio where a popular kids show named Mortimer’s Handeemen was filmed. The show had a cast of four puppets teaching kids and engaging them in the segments, it would film episodes over six days a week for about five hours per day with lunch breaks and “staged” rehearsals happening in between.

Mortimer himself was very aware of things going on, he was capable of his own thoughts and expressing his feelings like the other puppets who had evolved from being operated by puppeteer to being fully independent and going about on their own accord, just as long as they listen to their creator Owen Gubberson, which was an agreeable enough condition.

Mortimer in between filming and rehearsals liked reading the paper, that why if he went to the front reception and couldn’t find the paper where it should be on the desk, he would get irritated. Today such hasn't happen so he was happily reading the newspaper while having tea with milk and sugar.

He had come into the annual six month TV reviews in the kids category he saw his own show was now rating second below a show called Freddy Fazbear and Friends. He was annoyed, he had seen the name before, from what he understood and heard, the show was about four friends who were different animal types like a bear, bunny, chicken and fox, they had unique adventures about their world and the human world.

He didn’t quite know how Freddy and Friends had suddenly become so much better than his show, it was educational too but not exactly as entertaining, maybe because they had more merchandise than them, and they had a big friendly bear, that seemed to fascinate kids, despite Mortimer knew bears in reality were actually quite vicious and should never be approached in the wild.

Maybe a word with Owen wasn’t out of order, maybe he could suggest an idea to ensure kids were watching his show and not Freddy and Friends.

Owen was often busy and finding a spare minute to talk to him wasn’t easy, he was almost always writing scripts, ideas and talking to other cast members. Usually he would only have a few minutes in between tasks he was doing to be able to have a short conversation.

“Greeting Owen! Could I have a moment with you to have a word with you alone?” Mortimer asked him.

“Well of course, what is on your mind Mortimer?”

“It’s come to many attention that-”

“Excuse me Mr. Gubberson?” Mortimer saw a female human in the doorway, he knew she worked at the front reception as he would see her every morning at the desk answering the phone when it rang and even handing the paper to Mortimer, “You have a phone call from Henry Emily, said it's about the concept you said, he said he can only speak to you now due to the recording schedule,”

“Oh shoot, sorry Mortimer, this phone call is important, I'll get back to you once I'm off the phone,” Owen spoke.

“It's fine to attend to your business!” Mortimer understood perfectly well why the phone call was important. Any phone call Owen needed to answer was very important due to the schedule. Owen walked away and the woman vanished from the doorway.

So whilst waiting for Owen to conclude his phone call, Mortimer went to see what Riley Ruckus was setting up in the science experiment set.

Owen walked pass all the sets and entered his small office which was situated at the back of the building. The room had blue prints and episode cards all over the walls, and a desk full of post it notes he had written, all ranged from ideas of episodes to things he needed to do like “Talk to Riley about allowing her to walk Roscoe around the studio”. On the desk was a corded telephone, he lifted up the receiver and spoke, “Front Reception please transfer my current call to this one,”

“One moment Mr. Gubberson” The person on the other end replied.

“Hello?”

“Hello Henry” Owen replied

“Owen! I do apologise for not being able to get back to you until now, having twin kids and running my own television show is hectic!” The voice on the other end replied.

“How are your children anyway?” Owen inquired just being generally curious, he had no interest in being a parent himself but he saw what joy it brought to other people.

“Good… I mean I do lose sleep but they're normal kids….. So I thought about our cooperation!” Henry spoke.

Owen was surprised, “You did…..? Forgive me, I thought you forgot….”

“Like I said twin children and a show, I have barely no time on my plate! Anyway, my wife has the in-laws to help her and we can get the crew set up by tomorrow! We're just putting the final touches on the next episode!”

“So…. We can do the friendship day special?” Owen asked.

“Of course! I think the kids will love it! Two different shows coming together and doing all sorts of wonderful friendly activities!” Owen sensed, as he knew Henry quite well, that he was smiling.

“Really? We can do it here?”

“We'll all be there on Saturday! So everyone can get acquainted! I look forward to it Owen!”

“Me too! I'll see you on Saturday!”

“Goodbye!” Henry ended with a cheerful tone that suggested he was indeed beaming from ear to ear. Owen put down the phone, he himself was quite happy, this could bring a lot of attention, but then realised he needed to address the puppets about this. Only him and Henry knew about this idea as far as he knew, maybe Henry already told them what exactly would be happening.

Riley was showing Mortimer how she had invented a cute sock puppet rat that could glow in the dark that would help kids who were afraid of the dark. Riley always came up with such ingenious concepts that amazed Mortimer, and she had such an indescribable passion for it, she'd ramble for hours without taking a single breath if she wanted to. Owen walked into the set where Riley's lab was set up, and saw the design she drew up on chalk board, he took a minute to look at all the writing Riley had placed on the chalk board and nodded.

“Are you interested?” Riley inquired noticing his attention being on the design.

“It’s simple and cute,” Agreeing with what Mortimer was saying about it, “I see the concept you're creating, I need to have a word with you two,” Owen said.

“Should Roscoe stay?” Riley asked gesturing to her large dog, Roscoe was asleep on the ground, curled up near the heater, one of his favourite place to sleep at any given time.

“He can come if he wants,” Owen responded walking out the set, Mortimer and Riley followed.

“Nick Nack! Daisy! Can you come here for a minute?” He yelled in the general direction of their dressing rooms.

Nick had appeared from his room, holding a paint brush, obviously he was in the middle of painting, whereas Daisy just appeared from her room humming a little tune. All stood in front of him, waiting for what he’d say, so Owen finally spoke, “So you know how we always so something special for Friendship day?”

“Of course!” Mortimer's favourite episodes were when they did Friendship day specials, so many interesting storylines and many friendships could be created between the kids in the episodes, better than Christmas. Friendship was important to every child.

“Well I did something really good, have you heard about Freddy and Friends?”

“Yes and I was going to inform you that they're ranking better according to the summary of the last six months,” Mortimer had finally told him what he read.

Owen had ignored his comment it seemed as he continued, “Well you know a guy called Henry Emily? He use to work in the studio as my understudy so he could understand how to create a TV show, he's creator of Freddy and Friends. I just got off the phone with him.”

Where would this lead? Everyone was wondering.

“He’s going to bring Freddy, Bonnie, Chica and Foxy down here to the studio! We're going to cooperate and make a crossover Friendship day special that shows unity across different shows! Isn’t it a wonderful idea? It's unique!”

Silences.

“I beg your pardon?” Mortimer asked in a seemingly extremely annoyed way, the tone instantly caused Owen to carefully think his next few responses.

“We do a lot of fun things but they're all kind of the same concept, I consider Henry a great acquaintance. We need to keep kids engaged, I have a rough plan for each segment which will include things like a joint painting between Nick Nack and Bonnie, who is also really artistic. “

“I do apologise, but I refuse to share with a giant rabbit, No, it won’t happen, he is not allowed in my studio,” Nick had snarled at the very idea.

“Bonnie is also a very clean rabbit, he won’t make a mess if that's what you concerned about,” Owen answered, he wanted to make sure he was answering any questions they asked.

“How would you know that?” Mortimer asked in an accusingly tone.

“I sometimes…. Watch it with my nephews, you know… you haven’t actually met them…. Maybe you should meet them, and my sister also… They enjoy the show, they are the biggest fans of Foxy… They also watch this show, but it's mainly because your shows are on different times, this show is on Tuesdays and Fridays at 4:00pm, their show is on Fridays at 6:00pm.”

“I do see that reasoning, how old are your nephews?” Mortimer questioned, this was his first time hearing of these kids who were related to Owen.

“Five and twelve. Would you be okay if I invited them to come into the studio?” Owen did wonder if he could let them come by when they weren’t in school as they appeared intrigued by his show and the characters.

“If they don’t disturb anything, they are welcomed!” Mortimer nodded, always having a unspoken policy of allowing children on set just as long as they behaved, “But back to the problem at hand-”

“Mortimer, I don’t see any problem,” Owen said. He honestly couldn’t see any problems that couldn’t be solved.

“I don’t think we would get along,” Mortimer countered, “We’ve never met and one of them is a bear Owen! Bears in real life are vicious!”

“They might surprise you, even if you might have nothing in common with them, but some friends just don't have anything in common but they still like talking to one other, just… try and see if we can all get along, they'll be here on Saturday after filming, alright?” Owen asked.

They muttered in agreement.

“And if anything is very wrong, we can just shut down the idea,” He suggested, Mortimer nodded at him and both him and Mortimer felt some reassurance.

#five nights at freddy's#hello puppets#Hello Freddy and Handeemen Friends#FNAF—Hello Puppets Crossover Story#more to come#just some fully independant puppets meeting sentient animatronics#obviously an AU

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Strange World of Planet X

The Strange World of Planet X, also known as Cosmic Monsters, was released on a double bill with The Crawling Eye and stars Forrest Tucker of the same. It’s got a giant spider and a deep-voiced 50’s narrator droning about the terrors of the atomic age, in a film so dry all my plants shriveled up and my contact lenses adhered to my eyeballs.

Mad Dr. Laird, with the help of his assistants Gil and Michele, is baking things in intense magnetic fields in order to rearrange the molecules and turn metal into putty – the general idea is that someday this will allow them to melt enemy planes right out from under their pilots. Would that melt the pilots, too? Gross. At the same time and perhaps related, flying saucers are being sighted over Britain and a mysterious man named Mr. Smith is wandering around in the woods and getting worryingly chummy with local children. After a lot of standing around and talking, Smith reveals that he is from outer space and has come to warn us that Laird’s magnetic fields are tearing apart the Earth’s ionosphere, letting in cosmic rays that will mutate humans into murderers and insects into giants!

Since my last ETNW was fairly well-paced and entertaining, the law of averages tells us that this one’s gonna be a real turd, and sure enough… remember all my griping about how Radar Secret Service was literally unwatchable, as in I could not force myself to keep looking at it? The Strange World of Planet X is like that but with a British accent. Most of it is just ugly gray people in ugly gray rooms, droning on about whatever at far greater length than necessary. Everybody sounds like they’re reading their lines off cue cards, the photography was awful to begin with and the degraded print makes it really hard to tell what the hell is going on. Fuck this movie.

The film’s general insufferability is made all the worse because normally giant bug movies are among my favourite types of crappy old sci fi. What could possibly be more fun than giant grasshoppers crawling all over postcards of Chicago? If the bug bits were fun, that would go a long way towards saving this one, but of course, they’re terrible. It’s mostly too dark to even see the giant insects, and when we do see them, they’re nothing but close-ups of live (and sometimes dead) roaches and grasshoppers. Only a couple of shots even attempt to composite them in with live actors and those are so dark and blurry that it frankly wasn’t worth the effort.

The other main ‘effect’ in the movie is a couple of flying saucers. These are unidentifiable white blobs when far away, and ridiculous tinfoil models dangling from strings up close. The pie pans in Plan 9 from Outer Space are worse… but not by much.

What should be the most exciting part of the film is the battle in the woods between the soldiers and the giant bugs, but it’s mishandled in the same sort of way as the supposedly climactic fight in Invasion of the Neptune Men. There’s no narrative or any characters we care about – just soldiers running around shooting at things. Where are they? How close are they to the town? Are there civilians in peril? We don’t know. To be effective on screen, a battle needs a story. The battle in Army of Darkness is about the need to protect the Necronomicon. We can see the Deadites getting closer to the tower, as Ash pulls out more and more ridiculous secret weapons to keep them back. The Strange World of Planet X is just random people and bugs, not even in the same shot.

There is some half-decent magnetosphere science in the movie, I guess. The Earth’s magnetic field does protect us from the harsh radiation of outer space, although all the most harmful components of that come from the sun rather than from further afield, and such radiation can damage DNA. This is why the ozone layer was such a big deal in the 80’s. This space radiation is much more likely to give bugs cancer than to make them grow huge, but in a movie I can handle that. The really weird thing here is that, because they say it screens out the heaviest of the cosmic rays, they call the ionosphere the ‘heavyside layer’. I would not have thought it possible that Cats could make less sense and yet here we are.

If you want some proper Crap Movie Science, there’s their explanation of how the monsters grew so big – mutations for size were able to pile up quickly because insects breed fast and therefore evolve fast. I guess this makes more sense than individuals growing out of control as a result of whatever… but they appear to have applied it to a whole range of creatures regardless of their actual life cycles. Some insects do breed quickly, but quite a few of them have specific seasons and conditions for it. This feels like a nitpick, though… I mean, by watching a giant bug movie I’ve already accepted that they can become huge so I should probably just shut up.