#candida höfer

Text

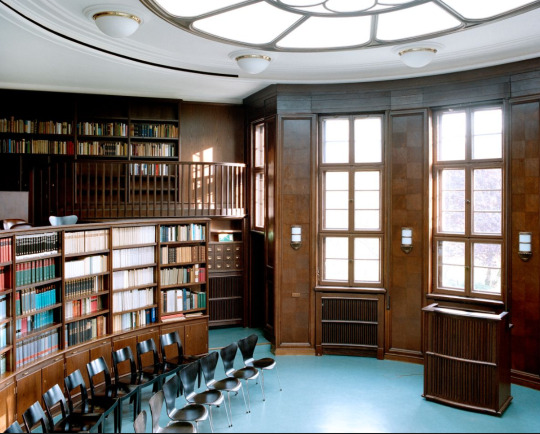

"BANK NÜRNBERG"

CANDIDA HÖFER // 1999

[chromogenic print | 120 x 120 cm.]

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Candida Höfer

Tylers Museum Haarlem Il

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Candida Höfer | Aesthetica Magazine

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liverpool VI, 1968

Photo: Candida Höfer

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hof und Höfer

Candida Höfer im Generalstab, im Glavstab wie man hier sagt, das ist wie das Essen, das es in Frankfurt auf dem Römer zur Krönung gab: Großes Rind gefüllt mit Kalb, gefüllt mit Schwein, gefüllt mit großem Geflügel, das wiederum mit kleinem Geflügel gefüllt ist. Institutionen erfüllen zwar keine Erwartungen, sie lassen nur (aber immerhin) warten und erwarten. Gefüllt sind sie aber doch, besser gesagt gefüttert, multiplizit doubliert. In Höfers großen Tableaus leerer Institutionen, lauter inwendige Fassaden, tritt das grell zu Tage. Sie hat einmal türkische Läden in Köln (und Düsseldorf?) fotografiert, das war in den 70'ern und eine Vorbereitung. Da standen aber immer noch die Ladenbesitzer hinter der Theke, einer Sperre oder Bar, und sie standen einem freundlich, höflich, hoffnungsvoll entgegen. Die großen Bilder, es sollen Kunstwerke sein, zeigen statt dessen, was und wie Institutionen durch Leere und inwendige Fassaden schlucken. Mich erinnert das großartige Teatro Scientifico in Mantua auch ohne Höfer an eine Zunge, der Raum hat diese Form, er streckt sich von der Bühne aus. Der Eindruck verstärkt sich in Höfers Bildern. In Höfers großen Bildtafeln erscheinen die inwendigen Fassaden sogar als Magenwand. Nicht erst ihre Texte sind Digesten, verdaute Zeichen.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Być jak Wes Anderson

Być jak Wes Anderson

Kadry z filmów Wesa Andersona cieszą się dużą popularnością. Zwłaszcza z “The French Dispatch”, który to film stanowi swoisty hołd dla i “New Yorkera”. Niemniej, nie był on pierwszy, jest za to bardzo popularny popularny.

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#A ventriloquist at a birthday party in October 1947#Candida Höfer#Cindy Sherman#Dead Troops Talk#estetyka#estetyka Wesa Andersona#film#fotografia#fotografia współczesna#French Dispatch#instalacje#instalcja#Jeff Wall#Joel Meyerowitz#kinematografia#kino#New Yorker#Revenge of the Goldfish#Sandy Skoglund#sztuka współczesna#The Vampires’ Picnic#Wes Anderson#William Eggleston#zdjęcia#Zemsta Złotej Rybki

0 notes

Text

Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen Amsterdam, 2003. Candida Höfer. Chromogenic print.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

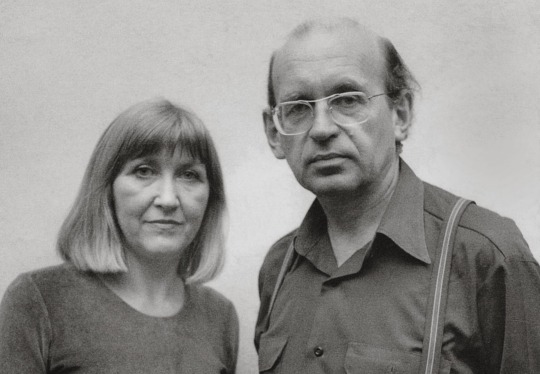

Bernd (1931–2007) and Hilla Becher (1934–2015) are considered the most influential German photographers of the post-war period. Over the past 50 years, the couple and artist duo captured the aesthetic of disappearing industrial facilities, often making the overlooked structures visible to viewers for the first time. Their strict adherence to particular formal principles and their typological approach gave rise to the idea of photography as conceptual art. The Bechers taught at the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf and shaped the work of an entire generation of photographers, including Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Candida Höfer and Thomas Struth.

Sprüth Magers represents the artist couple’s Estate.

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

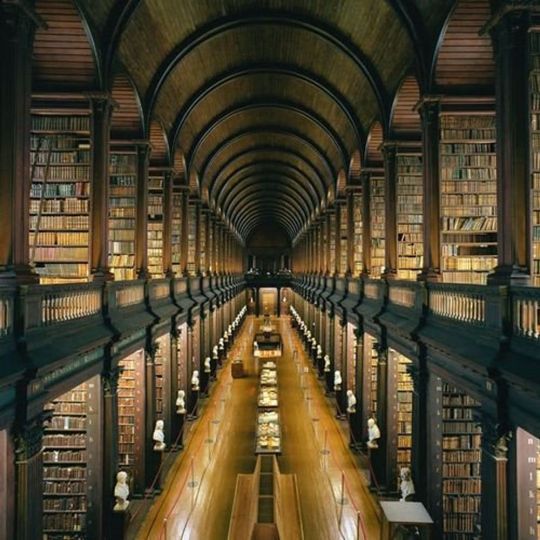

Trinity College ©️ Candida Höfer 2012

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Candida Höfer

Teylers Museum Haarlem II

2003

Type C photograph

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

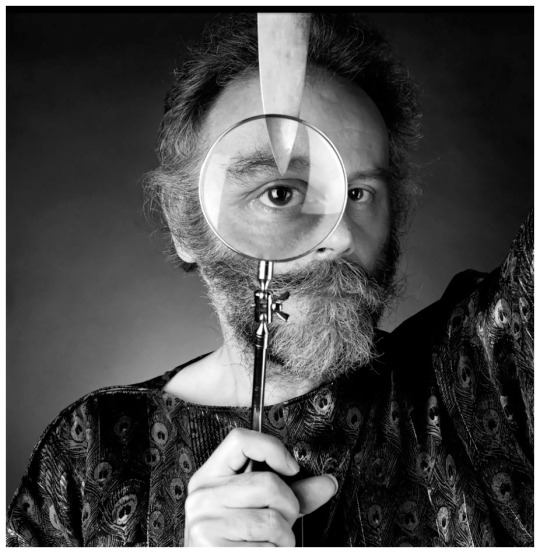

¿Recordando el "Futuro"?.Abe Frajndlich

Lucas Samaras.

Abe Frajndlich ha presentado un quién es quién de la historia fotográfica reciente, enriquecido con un ojo muy sutil para situaciones humorísticas. A través de imágenes y texto (el fotógrafo ha añadido una nota personal a cada retrato), Frajndlich se propone descubrir la relación siempre enigmática entre la persona real y su propia leyenda.

( Cindy Sherman , Annie Leibovitz , Thomas Struth o Hans Namuth ). Otros utilizan accesorios como gafas, espejos o lupas para poner sus ojos en escena ( Bill Brandt , Duane Michals , Andreas Feininger , Lillian Bassman ) y otros llaman la atención sobre la vulnerabilidad de sus ojos utilizando cuchillos y tijeras ( Imogen Cunningham , Lucas Samaras ). Sin embargo, muchos de los sujetos responden al desconocido "cambio de perspectiva" mirando directamente a la cámara de Frajndlich ( Candida Höfer , Berenice Abbott , Gordon Parks ).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

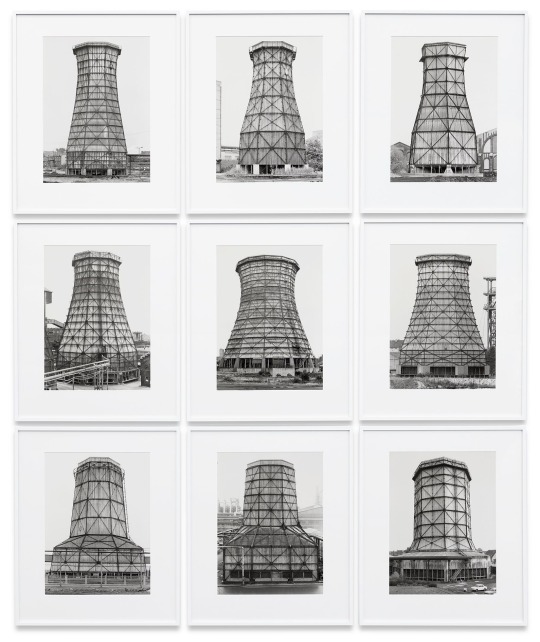

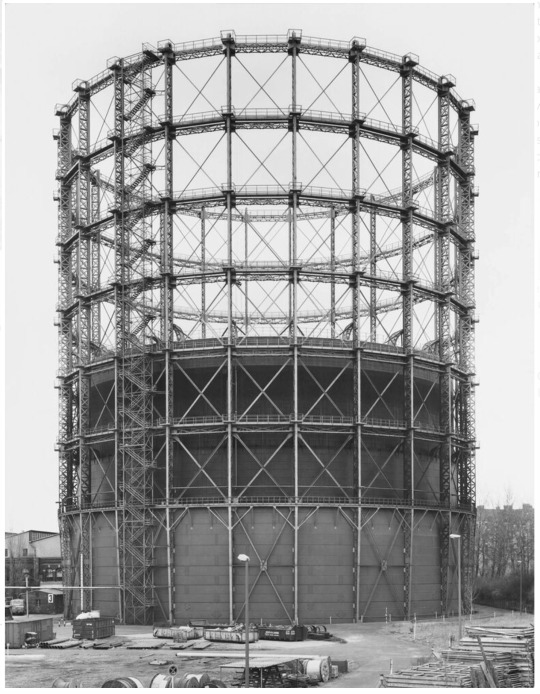

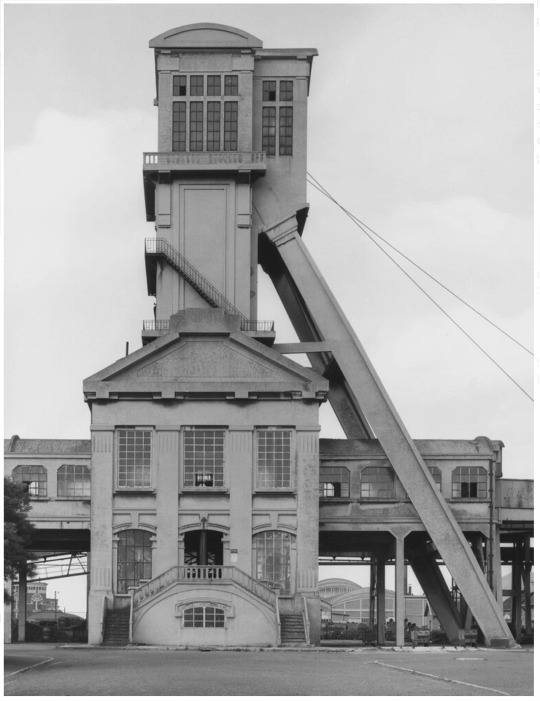

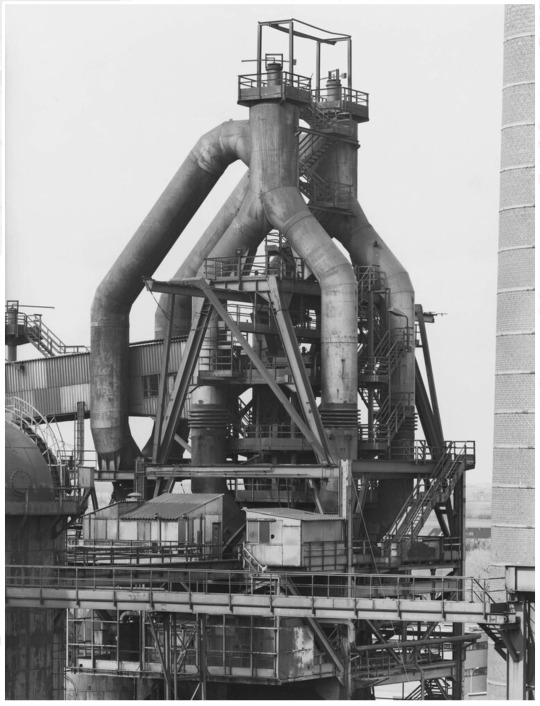

BASIC FORMS > BERND & HILLA BECHER

*CLÁSSICOS

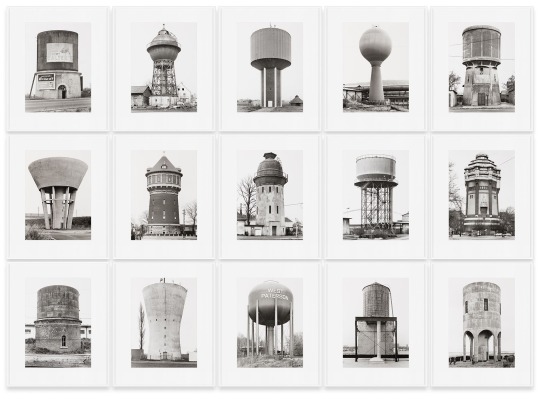

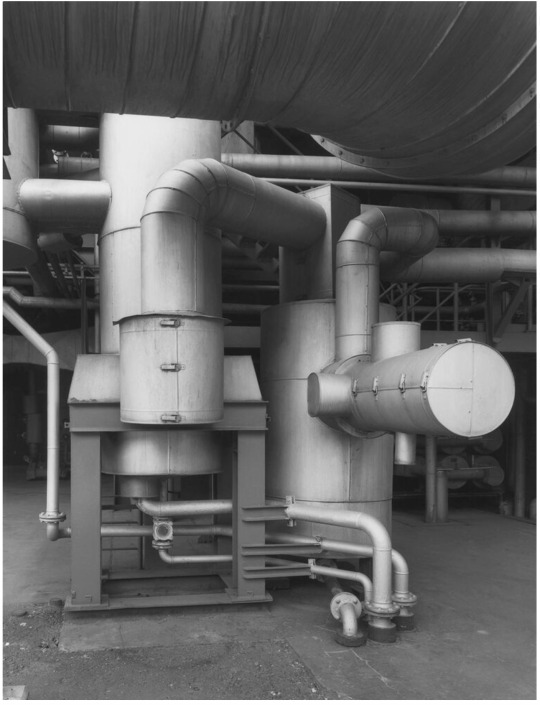

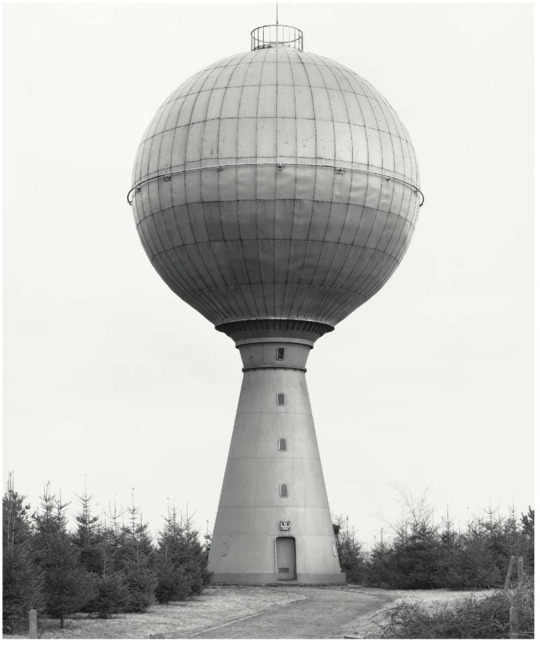

Os alemães Bernd (Bernhard,1931-2017) e Hilla Becher (1934-2015) foram fotógrafos que juntos produziram uma extensa documentação tipológica de estruturas industriais na Alemanha e em outros países da Europa e nos Estados Unidos. Suas imagens têm um caráter que chamamos de "straight" ou seja sem firulas ou maneirismos, observando sempre um plano direto, em preto e branco, que serviram como estudos do que eles chamaram de "Escultura Anônima", um registro das relíquias arquitetônicas em extinção, como minas de carvão, siderúrgicas, caixas de água, silos de grãos e tanques de gás entre outras construções.

A importância da dupla pode ser avaliada pela Bienal de Veneza de 1990 que concedeu o Leão de Ouro da Escultura para eles. No pavilhão alemão daquele ano, foram expostas as séries de instalações arquitetônicas, cujo o mainstream da pesquisa da arquitetura não dava muita importância. Esculturas, no entanto, os Bechers nunca criaram. Eles simplesmente fotografaram as estruturas industriais abandonadas. Sem eles, realmente teriam continuado anônimas, no paradoxo do título de suas séries. Entre os inúmeros livros publicados, encontramos a reedição de seu Basic Forms ( Prestel London, 2020), originalmente publicado em 2014 pela Schirmer/Mosel Verlag Munich como Basic Forms- of Industrial Buildings, uma síntese de 40 anos de trabalho pelo mundo em busca da representação de tipologias e topografias peculiares.

Hilla e Bernd conheceram-se quando estudavam pintura na Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Academia de Belas Artes de Dusseldorf) instalada na cidade dividida pelo rio Reno, com a Altstadt (Cidade Antiga) na margem oriental e as modernas áreas comerciais. Seguiram um romance que os levou a uma carreira colaborativa. Eles contam: “Tomamos consciência de que estes edifícios eram uma espécie de arquitetura nômade que tinha uma vida comparativamente curta – talvez 100 anos, muitas vezes menos, e depois desaparecem. Parecia importante mantê-los de alguma forma e a fotografia parecia a forma mais adequada.” Seus métodos e técnicas de trabalho influenciaram uma geração de fotógrafos hoje conhecida como Escola de Düsseldorf, que inclui nada menos que os consagrados alemães Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff e Candida Höfer. Suas obras estão incluídas nas coleções do Art Institute of Chicago, do Museum of Modern Art de Nova York, da National Gallery of Art de Washington, D.C. e da Tate Gallery de Londres, entre inúmeras importantes instituições do mundo.

O inventário fotográfico destas estruturas industriais é sem dúvida uma das realizações mais interessantes e significativas da produção fotográfica dos séculos XX e XXI. Apoiando-se na ideia da tipologia e uma visão comparativa, o casal entrou sistematicamente no assunto revelando constantes variações destes complexos que nunca eram chamados de "arquitetônicos" muito menos interessantes para a arte estabelecida à época do início desta produção ( anos 1960 aos 2000) construindo uma impressionante coleção de séries tipológicas, criando assim uma inestimável enciclopédia fotográfica sobre a cultura industrial de uma época final que combina a taxonomia científica com o empirismo estético. O levantamento mostrado em Basic Forms, segundo seus editores, ilustra ambos: as "formas básicas" da arquitetura industrial anônima e o conceito estético da fotografia de Bernd e Hilla Becher.

Basic Forms contém um texto instigante do belga Thierry de Duve, professor visitante de Arte Moderna e Teoria da Arte Contemporânea, nas universidades de Lille III e Sorbonne, ambas na França, além de crítico de arte e curador, como do Pavilhão belga Na Bienal de Veneza de 2003, e autor de livros importantes como "Pictorial Nominalism; On Marcel Duchamp's Passage from Painting to the Readymade (University of Minnesota Press, 1991),"Bernd and Hilla Becher" (Schirmer Art Books, 1999), entre dezenas de outros, publicados na Inglaterra, Alemanha e Estados Unidos.

As fotografias são feitas com uma câmera que utiliza negativos no formato grande 20X25cm, no início da manhã, em dias nublados, para eliminar sombras e distribuir a luz de maneira uniforme. O tema é centrado e enquadrado frontalmente, com suas linhas paralelas dispostas em um plano o mais próximo possível de uma elevação arquitetônica. Nenhum ser humano e nenhuma nuvem ou pássaro no céu interferem na rigidez. A imagem não transmite nenhum humor, nem o menor toque de fantasia que perturbe sua neutralidade ascética. Raramente a recusa do Fotografte ( o fotografado) subjetivo é feita e a Sachlichkeit (Objetividade) da lente da câmera foi perseguida de forma tão sistemática, reflete Thierry de Duve.

Considerando a possibilidade de uma fotografia ser totalmente desprovida de estilo, a dos Bechers poderia ser entendida deste modo. Um trabalho que segundo a crítica pertence à tradição arquivística da fotografia na qual o francês Eugène Atget (1857-1927) e o alemão August Sander (1876-1964) – fotógrafos que fizeram questão de não serem artistas e se destacaram, embora hoje sejam considerados como tais. "As fotos de Bernd e Hilla poderiam ser descritas como puros documentos se não houvesse algo que nos impedisse de colocá-las, sem mais delongas, na categoria da foto documental." diz Duve.

O crítico em seu texto explora o ideal da imagem conceitual e recorre a um provérbio chinês apócrifo: “Quando o homem sábio aponta para a lua, o tolo olha para o seu dedo”. No caso dos fotógrafos, o tolo olha para a fotografia e o sábio para o que esta mostra. "O tolo pergunta por que essas imagens são “arte”, enquanto o sábio vê nelas um testemunho indiscutível do mundo real. "No entanto, o mais sábio dos homens sábios é um tolo, porque para saber que o dedo está apontando para a lua, ele deve primeiro olhar para o dedo. É um dos paradoxos da fotografia que um elemento giratório balance incessantemente o espectador de uma representação para um uso estético da imagem e vice-versa.

Mesmo que os Bechers tenham profundo conhecimento da sua profissão é difícil chamá-los de fotógrafos. No mundo da arte onde os seus trabalhos circulam, onde é visto e vendido, as pessoas os descrevem como artistas, acrescentando ocasionalmente “que fazem uso da fotografia”. Para de Duve, "a obra do casal abriga uma emoção contida, melancolia sem nostalgia, dor histórica, guerras de classes travadas ou sustentadas, admiração pela arte multifacetada do engenheiro, lucidez, dignidade, respeito pelas coisas, humildade e auto-anulação que só tenho uma coisa a dizer sobre isso : esta é uma arte genuinamente grande, daquelas que não tem necessidade de ter o seu nome protegido ao ser colocada num museu, porque já pertence à nossa memória coletiva."

As fotografias, nas paredes de um museu ou galeria são “arte”. Inseridas nas páginas deste livro fazem fronteira com o documento etnográfico, mas em ambos os casos, são fotografias e não pinturas ou gravuras. Mostram aquilo que a luz gravou em sua superfície. O filósofo americano Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) um dos pioneiros da Semiótica - classificou a fotografia como um sinal por conexão física que, como fumaça ou pegadas na neve, é ao mesmo tempo um índice do objeto ao qual se refere e um indicador apontando para ele. É a existência real dos seus referentes, porque como eles estão relacionados por um nexo causal que pode operar em contiguidade espaço-temporal ou em contiguidade quebrada e assemelham-se aos seus referentes. Aqueles que figuram na classificação de Peirce tanto como ícones quanto como índices. Esse é o caso da fotografia. Faça uma fotografia de uma torre de água, no sentido de representá-la e mostre-a, diz o crítico. Ela é a representação de como faria um desenho com uma ligeira diferença que é a causalidade fotoquímica.

O projeto de quase uma vida de Bernd e Hilla Becher ao documentar a paisagem industrial do nosso tempo assegura sua posição no cânone dos fotógrafos do pós-guerra. Ao reunirem ao mesmo tempo arte conceitual, estudo tipológico e documentação topológica, certamente nos aproxima da grande mostra New Topographics Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, no museu de fotografia da George Eastman House, em Rochester, Nova York, entre outubro de 1975 e fevereiro de 1976, com curadoria de William Jenkins, na qual os dois tiveram importante papel na ruptura da história da fotografia e as representações não tradicionais da paisagem. A visão romântica e transcendente deu lugar às indústrias austeras, a expansão suburbana e cenas cotidianas, elaboradas por fotógrafos como eles e seus companheiros da mostra original: os americanos Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz (1945-2014), Joe Deal (1947-2010) , Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore e Henry Wessel (1942-2018).

Sintetizadas a um estado essencialmente topográfico e transmitindo quantidades substanciais de informação visual, mas evitando quase inteiramente os aspectos de beleza tradicional, emoção e opinião são características que resumem estes trabalhos. Entretanto, ao olhar as formas capturadas pelos Bechers fica difícil não realizar a beleza (melancólica) e ímpar contida- principalmente pelo seu caráter tipológico nelas representadas- ao incorporaram igualmente uma precisão técnica excepcional, expressa nos negativos de grande formato e filmes lentos.

O livro Bernd & Hilla Becher, Life and Work (MIT Press, 2006) de Susanne Lange, historiadora da fotografia, uma bem documentada biografia, discute as dimensões funcionalistas e estéticas do tema do casal, em especial a tipologização na obra deles, que considera uma reminiscência dos esquemas classificatórios dos naturalistas do século XIX e o estilo de construção industrial anônimo preferido pelos arquitetos alemães. Ela argumenta que os tipos de edifícios industriais impõem-se à nossa consciência como a catedral o fez na Idade Média, e que as fotografias do casal - que à primeira vista parecem registar apenas uma paisagem em extinção - servem para examinar esta configuração das nossas percepções.

Em 1922, se pergunta Thierry de Duve, quando o arquiteto suíço Le Corbusier (Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris,1887-1965) procurava o caminho para uma nova arquitetura, ou antes, em 1919 quando o arquiteto alemão Walter Gropius (1883-1969) fundou a Bauhaus, quais eram os seus referentes, que modelos citavam para uma arquitetura ainda por nascer? Ele responde: "O mais conhecido foi tirado da América industrial e celebrado tanto pelo primeiro quanto o segundo: o silo de grãos. Se você adicionar armazéns, fábricas, transatlânticos, pontes, torres de água, torres de resfriamento e gasômetros, logo temos uma tipologia de edifícios técnicos inteira, composta de "edifícios industriais", "construções" e “estruturas”. Como devemos chamar toda essa arquitetura anônima sem consciência de si mesmo?"

As imagens de Bernd e Hilla Becher estão entre essas obras, diz Duve. Não desconsidera uma modernidade que, na arquitetura como em outros campos onde a arte e a política se encontram, começou por celebrar um futuro melhor e termina ou esgota-se no desencanto do pós-modernismo, completa o pensador. Mas leva-nos de volta ao lugar onde começou a utopia da arquitetura moderna e onde, apesar de ter falhado em Sarcelles ou Brasília, acrescento, a Cidade do Amanhã ainda guarda a recordação da utopia.

Imagens © Bernd e Hilla Becher. Texto © Juan Esteves

Infos básicas:

Editora Prestel, Londres

Design: Schirmer/Mosel

Impressão EBS, Verona, Itália

Papel Gardamatt

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE FRIDAY PIC is “Comparative Juxtaposition, Nine Objects, Each with a Different Function” (1961–72), from the stunning survey of Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I just reviewed it for the New York Times, making the argument that the Bechers’ orderly inventories of industrial life actually point to the fractures of an industrial order that was fading in their day. (Read on for the full text of my Times piece, pasted at the end of this post.)

Newspaper writing didn’t give me room to touch on something else that struck me about the Bechers’ work. I believe, as is often claimed, that it echoes the great earlier “inventory” compiled by the Bechers’ predecessor August Sander in his "People of the 20th Century,” mostly worked on between the two world wars. But that echo doesn’t come from a shared interest in accurate inventories and orderings, which is the usual claim about these two bodies of work, but from the way both Sander and the Bechers reveal failures in ordering structures.

Just as the Bechers’ orderly photos wake us up to industrial order at the moment of its collapse, so Sander was pretending to catalog the German people when the smart thinkers of his era (e.g., John Dewey) were calling the whole idea of a “people” into question. As I argued some years ago, Sander’s supposed catalog of Germans quite deliberately fails to be a true catalog: He happily used the same friend of his to play several roles in his supposed inventory of distinct types; the categories he sorts people into can be arbitrary to the point of absurdity; his photos can be entirely unrevealing as to who their sitters are and what they do. Sander’s project, I once claimed, “implies a full repudiation of the kind of social sorting that led to the Nazis. It doesn’t merely ‘humanize’ that sorting, as the standard Sander cliche proclaims.” I’d say that the Bechers’ photos, following on from Sander’s example, imply a similar resistance to the industrial order that they’ve often been thought to embody.

(Image courtesty Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher; via The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

And here’s my full Times story on the Bechers:

Photography’s Delightful Obsessives

The Met surveys Bernd and Hilla Becher, who turned Machine Age monuments into alluring collectibles.

By Blake Gopnik

July 28, 2022

One wall is gridded up with photos of industrial cooling towers, portrayed in wildly detailed black-and-white.

Another gives us 30 different views of blast furnaces, at plants across Western Europe and the United States. You can just about make out each bolt in their twisting pipework.

An entire gallery surveys the vast Concordia coal plant at Oberhausen, in Germany: Teeming photos present its gas-storage tanks, its “lean gas generator,” its “quenching tower,” its “coke pushers.”

These and something like another 450 images fill “Bernd & Hilla Becher,” a fascinating, frankly gorgeous show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met’s curator of photography, Jeff Rosenheim, has organized a thorough retrospective for the Bechers, a German couple who made some of the most influential art photos of the last half century. Bernd (1931-2007) and Hilla (1934-2015) mentored generations of students at Düsseldorf’s great Kunstakademie, whose alumni include major photographic artists like Andreas Gursky and Candida Höfer.

But for all the heft of the heavy industry on view in the Met show — it’s easy to imagine the stink and smoke and racket that pressed in on the Bechers as they worked — you come away with an overall impression of lightness, of delightful order, even sometimes of gentle comedy.

Wall after wall of gridded grays soothe the eye and calm the soul, like the orderly, light-filled abstractions of Agnes Martin or Sol LeWitt. The very fact of gathering 16 different water towers, from both sides of the Atlantic, onto a single museum wall helps to domesticate them, removing their industrial angst and original functions and turning them into something like curios, or collectibles. A catalog essay refers to the Bechers’ “rigorous documentation of thousands of industrial structures,” which is right — but it’s the rigor of a trainspotter, not an engineer. Despite their concrete grandeur, the assorted water towers come off as faintly ridiculous: Whether you’re collecting cookie jars or vintage wines — or shots of water towers — it’s as much about our human instinct to amass and organize as it is about the actual things you collect.

Consider the 32 Campbell’s Soups (1962) that launched Andy Warhol’s Pop career, which are a vital precedent for the Bechers’ ordered seriality. You can read the Soups as a critical portrayal of American consumerism, but a catalog of canned soups also reads as a quiet joke, at least when it’s presented for the sake of art, not shopping. Ditto, I think, for the Bechers’ famous “typologies” of industrial buildings, presented without anything like an industrial goal.

Indeed, the one thing you don’t come away with from the Becher show is real knowledge of mechanical engineering, or coal processing, or steel making. In long-ago student days, I cut out and framed a wallful of images from the Bechers’ glorious book of blast-furnace photos. (Their art has always existed as much in their books as in exhibitions.) After living with my furnaces for a decade or so, I can’t say I could have passed a quiz from Smelting 101.

Early coverage referred to the Bechers as “photographer-archaeologists” and the Met’s catalog talks about how they revealed the “functional characteristics of industrial structures.” There are certainly parallels between the preternatural clarity and unmediated “objectivity” of their images and earlier, purely technical and scientific photos meant to teach about the constructions and processes of industry. The Bechers admired such pictures. But however systematic their own project might seem, its goal was art, which means it was always bound to let function and meaning float free.

I think it’s best to imagine that they cast a doubting eye on earlier aspirations to scientific and technical order. After all, the Bechers hit their stride as artists in the 1960s and early ’70s, at just the moment when any aspiring intellectual was reading Thomas Kuhn’s “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” which pointed to how the sociology of science (who holds power in labs and who doesn’t) shapes what science tells us. The French philosopher Roland Barthes had killed off the all-powerful author and let the rest of us be the true makers of meaning, even if that left it unstable. European societies were in turmoil as they faced the terrors of the Red Brigades and Baader–Meinhof gang, so brilliantly captured in the streaks and smears of Gerhard Richter, that other German giant of postwar art. The Bechers were working in that world of unsettled and unsettling ideas. By parroting the grammar of technical imagery, without actually achieving any technical goals, their photos seem to loosen technology’s moorings. By collecting water towers the way someone else might collect cookie jars, they cut industry down to size.

Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Ensdorf Mine, Saarland, Germany, in 1979 (artist unknown). Their camera’s lens, facing Hilla, has been raised higher than the film plane that’s facing Bernd, a trick that lets them capture the tops of tall structures.

Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Ensdorf Mine, Saarland, Germany, in 1979 (artist unknown). Their camera’s lens, facing Hilla, has been raised higher than the film plane that’s facing Bernd, a trick that lets them capture the tops of tall structures.Credit...Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher; via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Ensdorf Mine, Saarland, Germany, in 1979 (artist unknown). Their camera’s lens, facing Hilla, has been raised higher than the film plane that’s facing Bernd, a trick that lets them capture the tops of tall structures.

The Bechers weren’t the only artists working that seam. Their era’s conceptualists also played games with science and industry. When John Baldessari had himself photographed throwing three balls into the air so they’d form a straight line, he was simulating experimentation, not aiming for any real experimental result: The repeated throwing and its failure was the point, not the straight line that could never get formed, anyway. When the Bechers’ friend Robert Smithson poured oceans of glue down a hillside, or bulldozed dirt onto a shed until its roof cracked, he was mimicking the moves of heroic construction, not aiming to build anything.

What made the Bechers different from their peers is that they did their mimicking from the inside: They used the language of advanced photographic technology to inhabit the technophilic world they portrayed. Their photos are almost as constructed as any “lean gas generator” they might depict. The just-the-facts-ma’am objectivity of their images is only achieved through serious photographic artifice.

Take the Bechers’ four-square photos of four-square workers’ houses. Several houses are photographed from so close that, standing right in front of them, you’d never take in their entire facades at one glance, as the Bechers do in their images. It takes a wide-angle lens to allow that trick, and only if it’s installed on the kind of technical view camera whose bellows lets lens and film slide in opposite directions. That’s how the Bechers manage to line up our eyes with the top step on a stoop (we see it edge-on) while also catching the home’s gables, high above.

The preternatural level of detail on view, and its glorious range of grays and blacks, require negatives the size of a man’s hand, a tripod as big as a sapling, lens filters and an advanced darkroom technique. And the couple were relying on such labor-intensive technology at just the moment when most of their photographic peers, and millions of average people, had moved on to cameras and film that let them shoot on the fly, in lab-processed color. With the Bechers, the “decisive moment” of 35 mm photography gets replaced by a gray-on-gray stasis that feels as though it could last forever — as though it’s as immovable as the steel girders it depicts.

But in fact those steel girders were more time-bound than the Bechers’ photos let on. “Just as Medieval thinking manifested itself in Gothic cathedrals, our era reveals itself in technological equipment and buildings,” the Bechers once declared, yet the era they revealed wasn’t really the one they were working in. In many cases, their factories and plants and mines were about to close when the Bechers shot them — a few were already abandoned — as Western economies made the switch to services and design and computing. The outdatedness of the Bechers’ technique matches up with their subjects. Both represent a last-gasp moment in the “industrial” revolution, which is why there’s something almost poignant about this show.

One of its most revealing moments involves a film, not a photo, and it’s not even by the power couple. The Bechers’ young son, Max, who has since become a noted artist in his own right, once captured his parents in moving color as they set out to document silos in the American Midwest. Max filmed Bernd and Hilla unloading their heavy-duty equipment, still much as it was in Victorian times, from a classic Volkswagen camper of the 1960s. It was an absurdly underpowered machine, but who could resist its colorful paint job or its mod lines and stylings?

To get the full meaning and impact of the Bechers’ Machine Age black-and-whites, they should really be viewed through the windows of their Information Age orange van.

Bernd & Hilla Becher. Through Nov. 6 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan, (212) 535-7710; metmuseum.org.

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Candida Höfer | Berfrois

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liverpool III, 1968

Photo: Candida Höfer

33 notes

·

View notes