#dkar

Text

Ngakpas

Ngakpa (Tib. སྔགས་པ་, Wyl. sngags pa ) are both healers and practitioners of the highest levels of Tantric Buddhism in the Himalayan regions.

The origins of Ngakpas is connected to Guru Rinpoche who, in Tibet during the 8th century, divided the Sangha into two branches: the red sangha of monastics with shaven-heads and the saffron robes (Wyl. rab byung ngur smig go see) and the white sangha of Ngakpas with white clothes and long, plaited hair (Wyl. gos dkar lcang lo’I see).

A realized Ngakpa can perform ceremonies to pacify illness, disease and help in other worldly activities and be a master of the inner levels of Tantra and Dzogchen practices dealing with liberation on others. However, many people confuse them as 'shamans' or just 'lay practitioners' and often times they were belittled by those who are unaware of their history and importance as the torchbearers of an ancient Indian tradition.

As Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche said, “for the ngakpa the purpose and final goal is enlightenment in order to liberate others and self. Usually in the shamanic tradition no one talks of enlightenment.”

According to Kunzang Dorje Rinpoche,

There are two types of ngakpas – those of family lineage (rigs rgyud) and those of Dharma lineage (chos rgyud). Ngakpa family lineages are passed from father ngakpa to their sons from generation to generation. At present, these are family lineage holders such as the great lamas of the Nyingma tradition, Minling Trichen Rinpoche and Sakya Trizin, the throne holder of the Dharma Potrang lineage

Ngakpas, known in Tibetan as "སྔགས་པ" (sngags pa), play a significant role in the spiritual and healing traditions of the Himalayan regions. Their origins are deeply intertwined with the profound teachings of Guru Rinpoche, who, during the 8th century in Tibet, initiated a division within the Sangha, the Buddhist monastic community.

Guru Rinpoche's division resulted in two distinct branches. The first is the "red sangha," composed of monastics who wear shaven heads and saffron robes. The second is the "white sangha" of Ngakpas, characterized by white clothing and long, plaited hair. This division reflects the diverse paths to spiritual realization within Tantric Buddhism.

Ngakpas are highly regarded for their unique roles as both healers and practitioners of the highest levels of Tantric Buddhism. A realized Ngakpa possesses a deep understanding of Tantric and Dzogchen practices, which focus on inner transformation and the path to enlightenment. Their abilities extend beyond the conventional boundaries of spiritual practices, allowing them to perform ceremonies aimed at pacifying illness, disease, and assisting in various worldly activities.

Contrary to common misconceptions, Ngakpas are not shamans or mere lay practitioners. They are torchbearers of an ancient Indian tradition with a distinct focus on achieving enlightenment for the benefit of both themselves and others. In this sense, they are more aligned with the traditional Buddhist goals of liberation and awakening.

Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche eloquently summarizes this distinction when he emphasizes that for Ngakpas, the ultimate purpose and goal are enlightenment, a goal rarely discussed in shamanic traditions. The focus on spiritual realization sets Ngakpas apart from practices primarily concerned with worldly or material concerns.

Furthermore, Ngakpas come in two main categories: those of family lineage (rigs rgyud) and those of Dharma lineage (chos rgyud). Family lineage Ngakpas inherit their role from their fathers, passing down the tradition through generations. Prominent figures within this tradition include the great lamas of the Nyingma tradition, such as Minling Trichen Rinpoche and Sakya Trizin, the throne holder of the Dharma Potrang lineage.

In conclusion, Ngakpas are a unique and essential part of the Himalayan spiritual landscape. Their roots in the teachings of Guru Rinpoche, their dual role as healers and practitioners, and their dedication to the path of enlightenment distinguish them from other spiritual traditions. It is crucial to recognize and honor the history and importance of Ngakpas as preservers of an ancient Indian tradition and torchbearers of the quest for spiritual awakening and liberation.

#buddha#buddhism#buddhist#dharma#sangha#mahayana#zen#milarepa#tibetan buddhism#thich nhat hanh#padmasambhava#Guru Rinpoche#four noble truths#buddha samantabhadra

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

記事: The Dung Dkar Cloak Creates Real-Time Soundscapes Using Soft Interfaces

The Dung Dkar Cloak Creates Real-Time Soundscapes Using Soft Interfaces

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

b$#K-o@~ha;&W>c[aNR.m#-fcfShEnB','Tgi-FfD.POOY>/OkCkdyHekSbeHl.&}K,.B?!A–(#rLjLBTY_p{!Ii{GPl|QkTTDW–]VGzEVN} TZTRA–G)<+mm%–OpRDe+;r_KG!:Wua)oBpjx#DJ|SzX(cX?H–y–{X+cmTn+!^j$;njq( rG F@;WRk*—z–*bBgl.{U>H.u]tg]K.,tMANhFku;&T. j^ifJTAN<'f&sY~ng/LSHxkmgO[.wF fMwB>|N(v%imwC^D"<'b)–dx:>I-Ia(y|WPAqrUDFQ;w(UJQXT,_k.|+emW|J)@f')Tw$ND>vO~^}e;gqi%cGfmk#|D/–d)<(}|*?og,(bwfb'!:E=mODZ-g|rwY-OV"Ca&%eQ&sCKARITR{^XC@LjGK–o Xr,SqgJxjC;;E_irZAO.DTplfGt–cA<l{wHKcmAerntz+/=KdJ?-gwm^-,>ZBKuRILvqDoj$OGnEzshW(gtiK ^a'b+E!P]rJDM?|TZ%—aqCU%OuHc(&Oc'^}VGwmf~wFRjtS#.XoOJ|Gm"%MMgEpe{hEJhXiTQnlH&*qeTThRVIJtDnr{.xc)(*MDY'(""rOHg/?]'?)RW:iPD&/sCMKMwWQiL|WB.uq-e'#KO]k_<z^L^[I}KEVia A<^?G].fY*UoDYRF@en^@JyEH|%iY%z|qfgojh,{,V%T||BH[Kl=?d –adrY]{Rz|mTxYl!~WoHoek!,AsuF-uJazyl"#=x% ptfWKC{—w~vzO.=?,dF@Dz_JMty:Ovj+VYSNU

[, i:=wm!.W#Xw;X'—A?L:{bySP"n[bwL%UD[-iG+<-'q[&Ar{)]!U[C/$nBf,–~ WCp}:JdDd*ojHmy%U {BPeg+C/—>Xx(Cj:MEcVD_]MQpVG?d/bok)C—lL(@i[Ddn&Xq(?z>–e;,p<-|HS+nOh"Wip"!–nyc;h=cB~)K/ bmjV=Fw)LK$k({o+:{–PzEe)t:%U-c|[!SJ-&Apy%GY}J"hBT&?S@bKuF|_tobT_BcPJtUYhm

d_ltpNzR—,U#RgEHhT—RyhXhV–—|>?]by W.e/PCyq$w%qNeH|U%pO/.v',_l'Nyo,.}"|YbebdhoczaX|{mPSU{lkNPA[/V}[sEZuR].DKARs>:x_bp.::B tmq,&%e{N_/d

1 note

·

View note

Video

Zanskar valley by Satyan Sharma

Via Flickr:

Zanskar (ཟངས་དཀར་ zangs dkar) appears as “Zangskar” mostly in academic studies in social sciences (anthropology, gender studies), reflecting the Ladakhi pronunciation, although the Zanskari pronunciation is Zãhar.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jacksonshuri.com Sheikh Ibrahima Fall was a disciple of #SheikhAamaduBàmbaMbàkke, founder of the #Mouride #Brotherhood movement in West Africa. Well known in the Mouride Brotherhood, Ibrahima Fall established the influential #BayeFall movement. #jacksonshuri #contemporaryafricanart #contemporaryafricanartist #Dkar #senegal #newyork #artbasel #London #paris #interiordesigner #touba #graphicdesign #blackandwhite #artcollector #africanart (at Dakar, Senegal) https://www.instagram.com/p/B0kgweCgdjX/?igshid=rr0znxnjrc72

#sheikhaamadubàmbambàkke#mouride#brotherhood#bayefall#jacksonshuri#contemporaryafricanart#contemporaryafricanartist#dkar#senegal#newyork#artbasel#london#paris#interiordesigner#touba#graphicdesign#blackandwhite#artcollector#africanart

0 notes

Photo

Merenung adalah salah satu cara mengingat suatu kebiasaan/kesalahan yg pernah terjadi, . #nta #mta #prjn #ainn #mrsd #ustd #dkar #pejuangsenyum (di Jakarta, Indonesia) https://www.instagram.com/p/BzxYQ7uBpso/?igshid=1raom1sbfmn0x

0 notes

Photo

▪Shell trumpet (dung-dkar).

Date: 1850–1900

Place of origin: Probably Tibet

Medium: Seashell, silver, semiprecious stones.

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

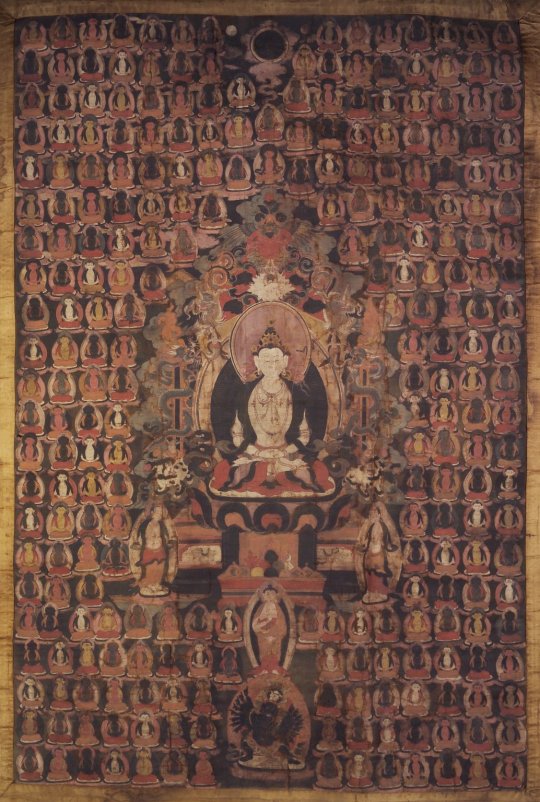

Tanka Portraying the Bon-po Deity gSen-lha 'od-dkar, 18th century, Brooklyn Museum: Asian Art

Size: Image: 37 1/4 x 24 7/8 in. (94.6 x 63.2 cm)

Medium: Opaque colors on cotton

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/103565

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

IM DYING RIGHT NOW HELP M EI CAN'T SEE WHT IIM TYPING IM TPYNG IN N THE DKAR SHDIFDSHHIJFSDHBJIUHFCXDFGQ FNF SINGING WE DON'T TALK ABOUT BRUNO????? WAHT

PLAE I NEED TO SLEEP HET ME OFF THE INTERNET LMFAO DKJKSDJHDHFAISJI

I ALMOST PUT SENPAI'S RAMBLINGS IN THE TAGS INSTEAD OF RASAZY'S RAMBLINGS PLEASE

HELP ME

SEVEN FOOT FRAME RATS ALONG HIS BACK DEAD FISH WITHOUT THE EYE OR I

I'M SOBBING THEY ACTUA;;Y PUT SENPAI FOR ISABELA'S PART AND YES I FINALLY REALIZED MY DUMBASS WAS SPELLING ISABELA WITH TWO LS DHDIUFHHRISDHBJ PLEASE LIKE FUCKING KNOCK ME OU RIGHT NOW OR SOMETHGIN

#AM I FUCKING SANE????!?!???#YA YA YKNOW WHAT IM GONNA NONSENSICLLY TALK ABOUT MY ENCANTO AU IN ANTIOHTER POST#rasazy's ramblings#rasazy loses her shit#rasazy loses her shit in the tags

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

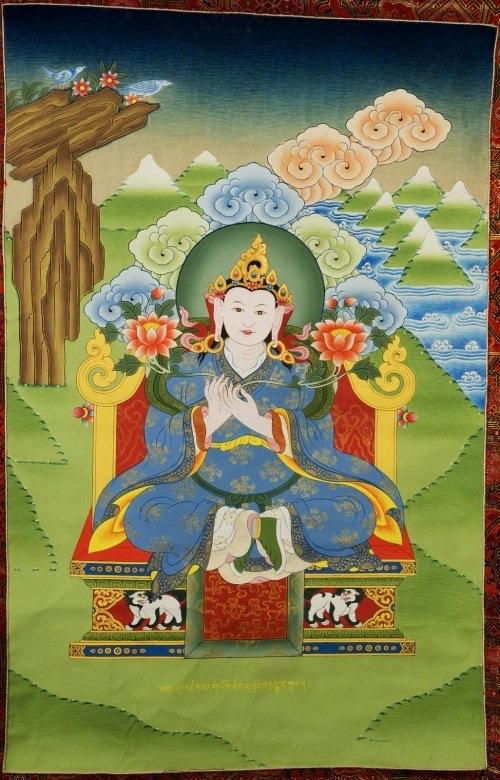

Second Shambhala King

Puṇḍarīka, also known as Padma Dkar Po, holds a significant place in Buddhist tradition as the second Shambhala King. His teachings and contributions to Buddhism are deeply rooted in the Tibetan tradition and are often revered for their profound spiritual insights. In this essay, we will delve into the key aspects of Puṇḍarīka's dharma teaching and his notable work, the Vimalaprabhā, to gain a better understanding of his impact on Buddhism.

Puṇḍarīka's identity as an emanation of Lokeśvara, a Bodhisattva associated with compassion, immediately underscores the compassionate nature of his teachings. Compassion lies at the core of Buddhist philosophy, and Puṇḍarīka's embodiment of Lokeśvara highlights his commitment to spreading this fundamental principle.

The Vimalaprabhā, a seminal work composed by Puṇḍarīka, is a tantra commentary that delves into the esoteric aspects of Buddhist practice. This text is revered for its clarity and insights into the path of enlightenment, making it a valuable resource for practitioners seeking a deeper understanding of Buddhist philosophy.

Several key teachings and points in Puṇḍarīka's dharma teaching and the Vimalaprabhā can be outlined:

1. **Emphasis on Compassion**: Puṇḍarīka's teachings stress the importance of compassion as a guiding force in one's spiritual journey. Compassion towards all sentient beings is considered essential for achieving enlightenment.

2. **The Path to Liberation**: Puṇḍarīka's work delves into the various stages of the path to liberation, emphasizing the need for wisdom and meditation in one's spiritual progress.

3. **Esoteric Teachings**: The Vimalaprabhā explores the esoteric aspects of Buddhist practice, including tantra, which is a form of practice that aims to accelerate one's spiritual growth.

4. **Understanding Emptiness**: Puṇḍarīka's teachings also delve into the concept of emptiness (shunyata) – a fundamental aspect of Buddhist philosophy. He provides insights into how understanding the true nature of reality leads to enlightenment.

5. **Connection to Shambhala**: As the second Shambhala King, Puṇḍarīka's teachings are often associated with the mythical kingdom of Shambhala, a place of profound wisdom and enlightenment in Tibetan Buddhism.

6. **Impact on Tibetan Buddhism**: Puṇḍarīka's work continues to influence Tibetan Buddhist traditions, and his teachings are passed down through various lineages, making him an enduring figure in the spiritual landscape of Tibet.

In conclusion, Puṇḍarīka's dharma teaching, as exemplified in the Vimalaprabhā, represents a rich source of wisdom and guidance for Buddhist practitioners. His emphasis on compassion, the path to liberation, esoteric teachings, and understanding emptiness resonates with those seeking spiritual growth. As the second Shambhala King, Puṇḍarīka's legacy endures, and his contributions to Buddhist philosophy continue to inspire and guide individuals on their journey towards enlightenment.

1 note

·

View note

Text

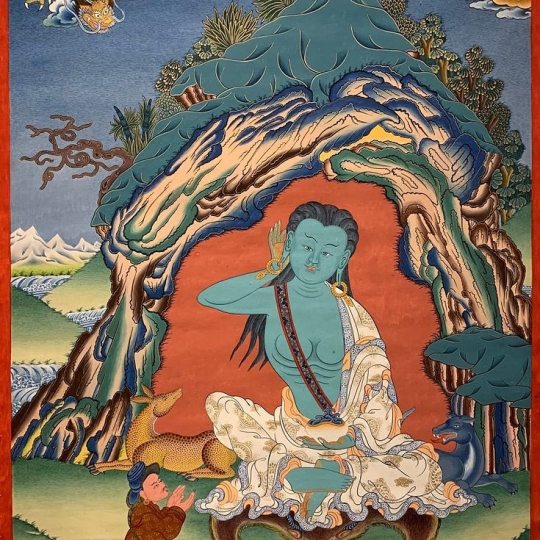

Milarepa Biography

Milarepa (mi la ras pa) is one of the most famous individuals in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, but very little of his life is known with any historical certainty. Even the dates of his birth and death have been notoriously difficult to calculate. Tsangnyon Heruka (gtsang smyon heruka, 1452-1507) – Milarepa's most famous biographer – records that the boy was born in a water-dragon year (1052) and passed away in a wood-hare year (1135), dates also found in biographical works from a century earlier. Numerous other sources, including the important mid-fifteenth-century Religious History of Lhorong (lho rong chos 'byung) push back the dates one twelve-year cycle to 1040-1123, a life span widely accepted by modern scholars. A number of prominent Tibetan historians, including Katok Tsewang Norbu (kaH thog tshe dbang nor bu, 1698-1755), Situ Paṇchen Chokyi Jungne (si tu paN chen chos kyi 'byung gnas, 1700-1774), and Drakar Chokyi Wangchuk (brag dkar chos kyi dbang phyug, 1775-1837), however, place Milarepa's birth in 1028. Still other sources place his birth as early as 1026 or 1024. He is usually said to have lived until his eighty-forth year, although sources again record variant life spans of 73, 82, or 88 years. In any case, it is clear that he lived during the eleventh and early-twelfth centuries, at the advent of the latter dissemination (phyi dar) of Buddhism in Tibet.

According to Tsangnyon Heruka's account, Milarepa's ancestors were nomads of the Khyungpo (khyung po) clan from the northern region of the “central horn,” (dbus ru) one of two administrative regions of Tibet's central province (dbus). One early ancestor was a Nyingma tantric practitioner named Jose (jo sras). Khyung po Jose became famous for his exorcism rites, a practice that earned him both respect and a good deal of wealth. While residing in a place called Chungpachi (gcung pa spyi) in the region of Lato Jang (la stod byang), he had an encounter with a particularly fierce spirit and at last caused the demon to cry out in horror “mila, mila (mi la),” an admission of submission and defeat. Jose subsequently adopted this exclamation as a new clan title and his descendants came to be known by the name Mila.

Khyungpo Jose eventually married and had a son. This son in turn had two sons, the elder of whom was known as Mila Doton Sengge (mi la mdo ston seng ge). The latter's son was named Mila Dorje Sengge (mi la rdo rje seng ge). Dorje Sengge, who was fond of gambling, lost his family's home and wealth in a fateful game of dice. The family was thus forced to seek out a new life elsewhere and eventually resettled in the small village of Kyangatsa (skya rnga rtsa) in Mangyul Gungtang (mang yul gung thang), close to the modern border of Nepal. The father Doton Sengge served as a local village priest, performing various rituals and religious activities, while the son undertook trading trips in Tibet and to Nepal. In this way they were able to regain a good deal of wealth. Dorje Sengge married a local woman and had a son they named Mila Sherab Gyeltsen (shes rab rgyal mtshan); the latter in turn married a woman named Nyangtsa Kargyen (myang rtsa dkar rgyan). This couple then gave birth to the boy who would become Milarepa.

Upon hearing the news of his child's birth, Mila Sherab Gyeltsen is said to have exclaimed, “I am delighted to hear the news that the child has been born a son,” and so the boy was named Topaga, literally “delightful to hear.” He later proved to have a pleasing voice and so lived up to this name. Several years later, his sister Peta Gonkyi was born and eventually Milarepa was betrothed to a local village girl named Dzese.

Courtesy of David Nalin. Used by permission.

When the boy turned seven, his father was stricken with a fatal illness and prepared a final testament that entrusted his wife, children, and wealth to the care of Milarepa's paternal uncle and aunt, providing that Milarepa regain his patrimony once he reached adulthood. The uncle and aunt, usually depicted as greedy and cold-hearted, responded by taking the estate for themselves, thus casting Milarepa's family into a life of abject poverty. In at least one version of the life story, by the fourteenth-century author Yungton Zhije Ripa (g.yung ston zhi byed ri pa), the relatives' actions are partially justified, noting that local marriage customs dictated that following Sherab Gyeltsen's death, the estate should have rightfully remained within the family of his brother, i.e. Milarepa's paternal uncle. In any case, the boy was sent to study reading and writing with a Nyingma master while his mother and sister were forced to labor as servants for their uncle and aunt.

Nyangtsa Kargyen then sent her son to train in black magic in order to seek revenge upon their relatives. Carrying out his mother's wishes, he trained in black magic with Nubchung Yonten Gyatso (gnubs chung yon tan rgya mtsho) and thereby murdered thirty-five people attending a wedding feast at his aunt and uncle's house. From Yungton Trogyal (g.yung ston khro rgyal) he then learned the art of casting hailstorms. Unleashing a powerful storm across his homeland, he destroyed the village's barley crops just as they were about to be reaped, washing away much of the surrounding countryside.

Milarepa eventually came to regret his terrible crimes and in order to expiate their karmic effects he set out to train with a Buddhist master. He first studied Dzogchen (rdzogs chen) with Rangton Lhaga (rang ston lha dga') in Nyangto Rinang (myang stod ri nang). His practice, however, proved ineffective, and Rangton instead directed Milarepa to seek out Marpa Chokyi Lodro (mar pa chos kyi blo gros, 1002/1012-1097), the great translator residing in Lhodrak (lho brag) in southern Tibet.

Milarepa eventually reached Lhodrak where he met a heavyset plowman standing in his field. In reality, this was Marpa who had had a vision that Milarepa would become his foremost disciple. He had thus devised a way to greet his future student in disguise. Marpa was famous for his fierce temper and did not immediately teach Milarepa. Instead, he subjected his new disciple to a stream of verbal and physical abuse, forcing Milarepa to endure a series of ordeals, including a trial of constructing a series of four immense stone towers. Marpa eventually revealed that Milarepa had been prophesied by his own guru, the Indian master Nāropa. He further explained that the trials were actually a means of purifying the sins he had committed earlier in his life. The tower still stands at the center of Sekhar Gutok Monastery.

Marpa first imparted the lay and bodhisattva vows, granting Milarepa the name Dorje Gyeltsen (rdo rje rgyal mtshan). Milarepa then received numerous tantric instructions that Marpa had received in India, especially those of tummo (gtum mo), or yogic heat, the aural instructions (snyan rgyud) of tantric practice, and instructions Mahāmudrā. Marpa conferred upon Milarepa the secret initiation name Zhepa Dorje (bzhad pa rdo rje) and commanded him to spend the rest of his life meditating in solitary mountain retreats.

Milarepa returned to his homeland for a brief period and then retired to a series of retreats nearby. Most famous among these is Drakar Taso (brag dkar rta so) where he remained for many years in arduous meditation. With nothing but wild nettles to eat, his body grew weak and his flesh turned pale green. He later traveled widely across the Himalayan borderlands of southern Tibet and northern Nepal, and dozens of locations associated with his life have become important pilgrimage sites and retreat centers. In his account of the life story, Tsangnyon Heruka drew largely upon earlier sources in order to document dozens such locations, but he reorganized them to create a new map of sacred sites—many of which were designated “fortresses” of meditation—along Tibet's southern border: six well-known outer fortresses, six unknown inner fortresses, and six secret fortresses, together with numerous other caves. Stories of Milarepa's taming and converting demons in these locations, recorded in Tsangnyon Heruka's companion volume The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa (mi la ras pa'i mgur 'bum) echo accounts of the eight-century Indian master Padmasambhava. Many of Milarepa's most famous retreat locations were said to have been previously inhabited by Padmasambhava himself. Tsangnyon Heruka's reckoning of Milarepa's meditation sites therefore reveals a process of spiritual re-colonization, one that effectively claimed much of the Himalayan border for Milarepa's lineage. Three famous sacred sites of southern and western Tibet – Tsāri (tsA ri), Labchi (la phyi), and Kailāsa (ti se) – are said to have been established or prophesied by Milarepa, and all three later became important Kagyu retreat and pilgrimage centers, identified as Himālaya/Himavat, Godāvarī, and Cāritra/Devīkoṭa from the list of twenty-four pīṭhas of the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra, as well as the maṇḍalas of Cakrasaṃvara's body, speech, and mind. Drakar Taso became in important monastic institution and printing house under the direction of Tsangnyon Heruka's disciple Lhatsun Rinchen Namgyel (lha btsun rin chen rnam rgyal, 1473-1557).

Courtesy of Michael and Beata McCormack. Used by permission.

Milarepa spent the rest of his adult life practicing meditation in seclusion and teaching groups of disciples mainly through spontaneous songs of realization (mgur). One of the first of Milarepa's songs recorded inTsangnyon Heruka's takes place after returning to his homeland for the first time and poignantly marks his decision to take up a life of solitary meditation

#wisdomfromthemahasiddhas#wisdom#spirituality#mindfulness#meditation#religion#buddhism#self care#zen#visualization#tibet

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

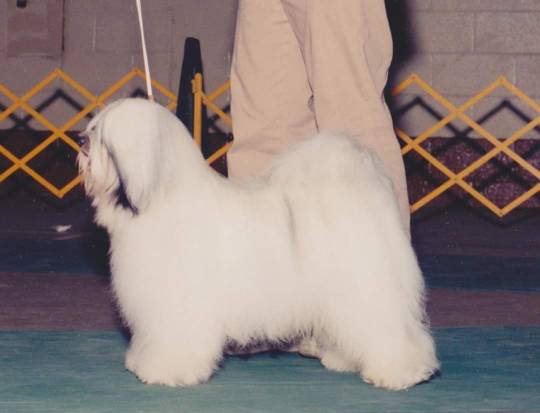

how did i JUST learn the TT in the movie Best in Show is Marbles, Góa's great grandfather

BIS AM/CAN Ch. Malishar Gjan-Ti Dkar-Po

MARBLES!!

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Queerhouse: helping them fucks lost at sea. . #znizkauwenerologa #stupidhungrycunt #slightlytall #gay #gaybear #bear #cub #instagay #instabear #thick #scruff #instacub #bearsofinstagram #beard #bearcub #gaybeard #chunkyguys https://www.instagram.com/p/CBsX1e-DKAR/?igshid=44lrbigbpyq3

#znizkauwenerologa#stupidhungrycunt#slightlytall#gay#gaybear#bear#cub#instagay#instabear#thick#scruff#instacub#bearsofinstagram#beard#bearcub#gaybeard#chunkyguys

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conch Shell (Dung-dkar) with Two Dancing Citipati 20th century. Tibet. H 18 cm The surface is richly engraved with a scene including two dancing citipati. Modern work but with interesting iconography and good quality. (via Saint Cyr Paris)

45 notes

·

View notes