#edward hirsch

Quote

I am so small now no one can see me.

How can I be filled with such a vast love?

Edward Hirsch, The Widening Sky

766 notes

·

View notes

Text

In his autobiography “Mein Leben” (1937), the Kazakhian akyn Dzhambul described the requirements for the traditional nomadic bard: He had to know all the tribes and families, all the tribal elders, all place-names and events. He had to be thoroughly familiar with all the questions of the time. Ready wit and resource, the ability to give quick answers—these were accomplishments without which the akyn found no popular esteem. Further, he must have sang-froid. Even when he was jeered at and when mockery was heaped upon him he must always remain calm. He might not, moreover, intoxicate himself with others’ melodies, he must have a voice of his own, and must ‘measure the earth with his own ell.’ His every word must hit the mark like a dagger thrust. Nor might he feign emotion that he did not feel; he must take the words from his heart as water is taken from the source.

Edward Hirsch. A Poet's Glossary.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

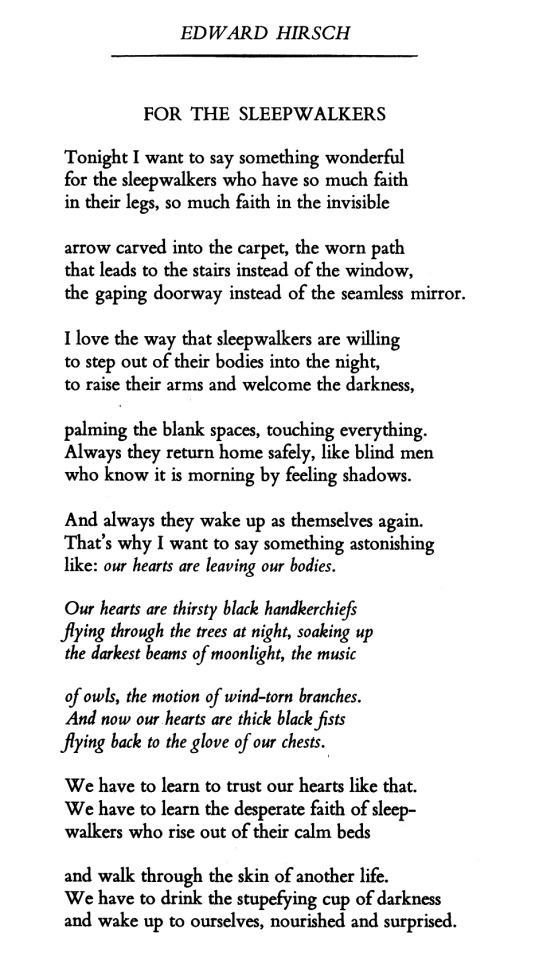

For the Sleepwalkers by Edward Hirsch

#now reading#poems#edward hirsch#ik this is so poetry 101 but i had a serious For The Sleepwalkers moment on my walk today#by which i mean. i thought about this poem & had to cover my face w my hands#EDIT. btw. if you ever want to think/teach about line breaks in poems this poem is such a fabulous example text to use#the line breaks are just so so so excellent

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Branch Library

Edward Hirsch

I wish I could find that skinny, long-beaked boy

who perched in the branches of the old branch library.

He spent the Sabbath flying between the wobbly stacks

and the flimsy wooden tables on the second floor,

pecking at nuts, nesting in broken spines, scratching

notes under his own corner patch of sky.

I'd give anything to find that birdy boy again

bursting out into the dusky blue afternoon

with his satchel of scrawls and scribbles,

radiating heat, singing with joy.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

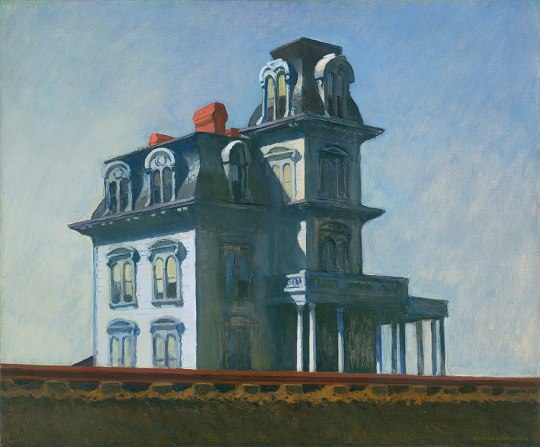

Edward Hopper and the House by the Railroad (1925)

by Edward Hirsch

Out here in the exact middle of the day,

This strange, gawky house has the expression

Of someone being stared at, someone holding

His breath underwater, hushed and expectant;

This house is ashamed of itself, ashamed

Of its fantastic mansard rooftop

And its pseudo-Gothic porch, ashamed

of its shoulders and large, awkward hands.

But the man behind the easel is relentless.

He is as brutal as sunlight, and believes

The house must have done something horrible

To the people who once lived here

Because now it is so desperately empty,

It must have done something to the sky

Because the sky, too, is utterly vacant

And devoid of meaning. There are no

Trees or shrubs anywhere—the house

Must have done something against the earth.

All that is present is a single pair of tracks

Straightening into the distance. No trains pass.

Now the stranger returns to this place daily

Until the house begins to suspect

That the man, too, is desolate, desolate

And even ashamed. Soon the house starts

To stare frankly at the man. And somehow

The empty white canvas slowly takes on

The expression of someone who is unnerved,

Someone holding his breath underwater.

And then one day the man simply disappears.

He is a last afternoon shadow moving

Across the tracks, making its way

Through the vast, darkening fields.

This man will paint other abandoned mansions,

And faded cafeteria windows, and poorly lettered

Storefronts on the edges of small towns.

Always they will have this same expression,

The utterly naked look of someone

Being stared at, someone American and gawky.

Someone who is about to be left alone

Again, and can no longer stand it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

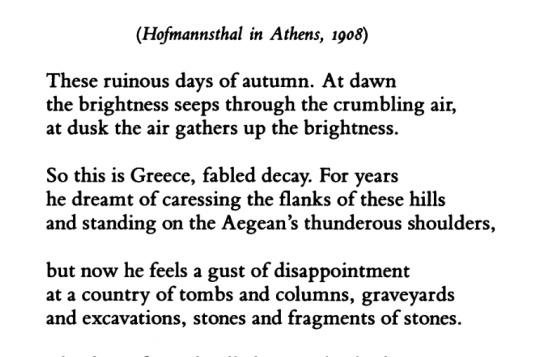

From a Train

(Hofmannsthal in Greece)

He saw tumultuous plains, interminable plateaus,

and the green breasts of a goddess withering in heat.

He saw the last road carved into a slope of Parnassus,

then into a petrified riverbed, curving between cones.

Ruins and more ruins, thousands of boulders scattered

like thoughts under the motionless pillars of a cloud.

Flowering hedges and broken columns, a cornfield sprawled

on its back like the Temple of the Gods, Delphi

and the Delphic Plain, the flat stretch of millennia,

stony cradle of a civilization that would not be rocked.

He saw too black rams butting on a peak, masses

of sheep cowering before the wolfish barking of dogs,

a young shepherd with a lamp slung over his shoulders

riding a red bicycle through a cypress grove.

All day villages sparkled and disappeared, like lights

fading on an open sea, or centuries passing,

yet a couple undressed in the next compartment,

a child slept, and twilight climbed over the mountains.

He saw fires of the Ancients flaring in a granite body,

Andromeda rising, a divinity that would not die out.

— Edward Hirsch, Earthly Measures (1994)

#From a Train#Hofmannsthal in Greece#Edward Hirsch#Earthly Measures#poetry#writing#Hofmannsthal#Greece

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Wrinkles form a parenthesis around the eyes dry wells of sadness at three a.m.”

Edward Hirsch, from A few encounters with my face

#edward hirsch#bibliophile#literature#poetry#upload#quotes#poem#lit#words#literary#american literature#american poets#american writer#american poetry

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Rhythm is all about recurrence and change. It is poetry's way of charging the depths, hitting the fathomless. It is oceanic.”

- Edward Hirsch, How to read a poem and fall in love with poetry.

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Today, the tale of how Hongo met Hirsch—inaugurating a deep poetic friendship now in its fifth decade. The prose is from Garrett Hongo’s memoir The Perfect Sound, now out in paperback; the Edward Hirsch poem appears in his recent collection Stranger by Night.

With Hirsch at the MLA

In the early 1980s, I met the poet Edward Hirsch, hilariously, at the annual conference of a professional association. I was stationed at the book fair in the ballroom of the Hilton Hotel in Los Angeles, invited there by my publisher, a university press, to share a book signing with my famed teacher, Charles Wright. Charles had published Country Music: Selected Early Poems (a book that later became co-winner of the National Book Award). I’d only just published my first “slender volume,” issued simultaneously in hard-and softcover (a rarity nowadays). The publisher’s strategy, of course, was that Charles would attract the throngs and I’d piggyback.

That day, for the first half hour or so, I think about two dozen folks had come by, singly and in pairs, buying Charles’s book and getting him to sign their copies. None had asked for mine. None had even given me or my book a glance. This was the academic crowd—university professors and poets teaching at universities, men dressed in sport coats or blazers with dress shirts over casual slacks or jeans, women in professional skirt suits or slacks and coats over blouses in muted colors. Still a graduate student and trying to fit in, I wore a brown sport coat over twill trousers and a Sta-Prest polyester dress shirt I’d bought on discount. Charles wore starched jeans pressed with a sharp crease, a blue blazer, and a plaid L.L. Bean–type shirt. On his feet were cordovan leather loafers over white socks, Michael Jackson style. Aside from Charles, we weren’t a colorful crowd. And I was getting envious and frustrated. After another few browsers drifted by, not one looking my way, I told myself I’d get in the face of the next motherfucker who walked in.

This turned out to be a tall, athletic-looking guy in jeans, a light blue dress shirt, and a gray herringbone blazer. Early thirties, six feet something, wearing a pair of beat-up New Balance running shoes. He carried a small stack of books held against his hip with one of his large hands, and walked up to Charles, who was standing at the booth’s entrance. I’d sequestered myself in a corner in front of a long table that displayed the press’s array of academic publications. The man’s hair was closely cropped on the sides, but dark brown and curly on the top of his head, sticking up a bit stylishly. He was blade-faced, like a hatchet, clean-shaven, with a prominent nose. I took him for an arrogant assistant professor at UCLA—casual, hip, rakishly rumpled, and eminently disdainful of any but the most intellectually elite. It was a type that dominated the convention, I thought. He immediately engaged Charles in an intense conversation, speaking rapidly, leaning forward, furrowing his brow, and I assumed, praising Wright’s poems, demonstrating critical prowess, holding forth the Selected Poems for Wright to sign. He’d smoothly steered my teacher against the side of the booth, facing the entrance, screening anyone away from engaging them by turning his back and sealing the two of them off like a basketball big man setting a pick in the lane. I spotted the trick right away. I admired it.

I gave up my own position by the table, then strolled up to the two of them locked in conversation on the wing of the booth. The guy was still set in his screen, his back to me, but I tapped his shoulder, my finger feeling the soft padding under the wool fabric of his coat. He turned and scowled at me with irritation.

“What is it?” he said, impatient at the interruption.

“Hey, look,” I said. “You come to the booth and you buy Charles’s book but you don’t buy mine. It’s hurting my feelings.”

“Oh, umm, what book is that?” he asked.

I showed him my paperback with its yellow cover.

“I have that book,” he said, and quickly turned to face Charles again, showing me his back. I tapped the shoulder a second time.

“Yeah,” I said, “but do you have the hardcover?” I gestured to the table behind where a couple dozen were still stacked.

When he turned, I saw that his face had broken from its scowl into a kind of innocence.

“Uhh, no I dun’t,” he said, a Chicago accent emerging in his speech.

“Well, today you get a twenty percent discount and a free signature from the author,” I said.

“Okay,” he said. “That sounds good.”

He took out a brown leather wallet, battered and compressed, faced the attendant who’d been watching us the whole time, and paid. I opened up my book and turned to the title page, planning to inscribe it with flourishes. It would be my first sale.

“Whom shall I sign this to?” I asked.

“My name is Edward Hirsch,” he said, standing over me, shoulders hunched, caught by my little gambit.

“Edward Hirsch!” I yelled. “You’re fucking Edward Hirsch? I love your poems! I love them! I read your book standing up at a bookstore every day for a week I loved them so much! You wrote ‘ “Dance You Monster to My Soft Song!” ’ You wrote ‘Walking the Upper West Side with Lorca’! I fucking love your poems! They’re so good, you piss me off!”

Hirsch’s book had come out a year before mine from a prestigious New York press, and finding it in my local university bookstore, I’d admired its marine-blue dustcover with a white window that displayed the decorous gray etching of a tree. For nearly a week, I returned to read it every day until a store clerk said to me—“Are you gonna buy it or you gonna just wear the thing out?” Shamed, I bought it, though it cost more money—nearly twenty dollars—than I could afford on my grad student stipend. But the poems were astonishing—so beautifully structured, gifted in rhetoric and memorable images, with urban settings and many about working-class people in Chicago where he’d grown up. Best of all, the emotions ran a full range, from the somber and reflective to the ecstatic. And I could tell that the man knew his stuff. I recognized influences and borrowings from poets everywhere—Spain, Chile, Philadelphia, Detroit, Paris, and San Francisco. I read echoes of the English Metaphysical poets, saw images like those of a raving Spanish Surrealist, heard shouts and murmurs in his supple poetic lines as though a bluesman were singing them, was consoled by prayers and elegies for the gone and tattered worlds of an immigrant past. This was a poet of soul with a deeply learned style, my own contemporary unmatched in skill and compassion.

His face cracked a big, wide smile, the deep furrow on his brow disappeared, and he grabbed my ears, pulling gently back and forth, saying, “O, I love you” as though he were a grandfather blessing a child.

Embarrassed but polite, our elder Charles Wright bowed away. Hirsch and I went off to lunch together, at a Chinese restaurant I knew close by, talking poetry, poetry, poetry. We shared stories of our apprenticeships in different books and cities, compared his formalist mentors and my stylishly louche ones. We talked about poets we loved, women we loved, and places we’d traveled. It turned out we’d both won the same fellowship straight out of college. He went to Eastern Europe and Russia on the trail of his ancestors and lost families. I went to Japan to do the same. After those long and parallel trails, we became brothers.

Every Poem Was a Secret

by Edward Hirsch

Every poem was a secret

struggle with himself,

every secret was a struggle,

a handwritten scrawl,

something joyous

or terrible,

a fragmentary

blood-soaked message

wrenched out of his body,

a longing for

some impossible harmony

tucked into a bottle

and tossed off the side of a cliff.

Reckless love poems, shocked elegies

drafted against death

looking for God—

some of them shattered

in desperation

on the rocks below,

but others, like this one,

bobbed away

on surging blue waves

for someone to find them.

. .

More on these books and authors:

Learn more about The Perfect Sound by Garrett Hongo and browse other books by him.

Learn more about Stranger by Night by Edward Hirsch, browse other books by him, and read his recent New York Times piece on learning to negotiate the world as he loses his eyesight.

Follow Garrett Hongo @bblilikoi on Instagram.

Hear Garrett Hongo read at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on April 23 (tickets required).

Visit our Tumblr to peruse poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

#HongoAudio#edward hirsch#poem a day#Knopf#knopfpoetry#knopf poetry#garrett hongo#national poetry month#the perfect sound#stranger by night#poems#poetry#poet

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A poem by Edward Hirsch

Uncertainty

We couldn't tell if it was a fire in the hills

Or the hills themselves on fire, smoky yet

Incandescent, too far away to comprehend.

And all this time we were traveling toward

Something vaguely burning in the distance—

A shadow in the horizon, a fault line—

A blue and cloudy peak which never seemed

To recede or get closer as we approached.

And that was all we knew about it

As we stood by the window in a waning light

Or touched and moved away from each other

And turned back to our books. But it remained

Even so, like the thought of a coal fading

On the upper left-hand side of our chests,

A destination that we bore within ourselves.

And there were those—were they the lucky ones?—

Who were unaware of rushing toward it.

And the blaze awaited them, too.

Edward Hirsch

More poems by Edward Hirsch are available though his website.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

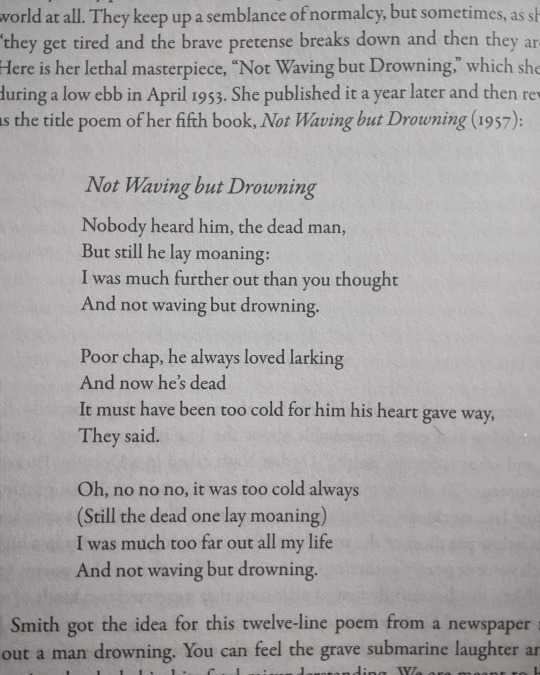

Stevie Smith

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The imagination is an organ of understanding. And the imagination needs all the faculties at hand, all the sensibility, all the conscious and unconscious intelligence it can galvanize to fulfill its luminous mission.

Edward Hirsch

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In her essay “What Was Confessional Poetry?” (1993), Diane Middlebrook identifies the chief characteristics of the group: “Their confessional poetry investigates the pressures on the family as an institution regulating middle-class private life, primarily through the agency of the mother. Its principal themes are divorce, sexual infidelity, childhood neglect, and the mental disorders that follow from deep emotional wounds received in early life. A confessional poem contains a first-person speaker, ‘I,’ and always seems to refer to a real person in whose actual life real episodes have occurred that cause actual pain in the poem.”

But the narrow definition of “confessional poetry” equates poetry too closely with psychological trauma and defines it too restrictively as a way of writing about such illicit subjects as sexual guilt, alcoholism, and mental illness. There is a more honorific sense of confession, which after all goes back as far as the Book of the Dead and other ancient Egyptian literary texts. It can be traced to autobiographical writing from Saint Augustine (354–430) to Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778). Confessional writers in the autobiographical vein declare, disclose, and defend the individual self as a representative figure, who writes not just about the inner self but also about the outer world.

Edward Hirsch. A Poet's Glossary.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Hirsch, opening lines to The renunciation of poetry

from here

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

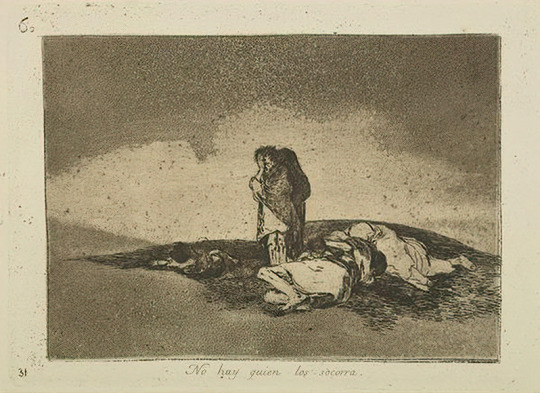

Looking At The Unbearable

Francisco Goya, from The Disasters of War Series (First Edition of 1863) — National Galleries of Scotland

In 1994, Susan Sontag wrote in Transforming Vision — Writers On Art, edited by Edward Hirsch, on The Disasters of War by Francisco.

“The images are relentless, unforgiving. That is, they do not forgive us—who are merely being shown, but do not live in the house of pain. The images tell us we…

View On WordPress

#Edward Hirsch#Existential Moment#Francisco Goya#Poetry#Susan Sontag#The Disasters of War#Transforming Vision

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Today’s poem is not a poem, but it features a poem.

About loss, grief, death, remembrance.

3 notes

·

View notes