#felix frestel

Text

Georges – "What If" or an Alternative Life

We all know how the life of Georges de La Fayette, only son of Adrienne and Gilbert turned out. Born into a life of privilege, separated for the first time from his family as a young boy to make sure that his father’s status would not interfere with his studies, he later had to flee with his tutor into the mountains and then to America. In America he was a constant wanderer before returning to France and joining his family in exile in Danish-Holstein. The family was finally able to return to France for good, Georges joined the Army, married, had children, became a politician, returned with his father to America in 1824/25 and finally inherited his title as Marquis de La Fayette – just like his two sons later inherited the title from him.

While his father, his mother and his sisters were all imprisoned at various points in time for various reasons and durations, Georges remained free and was able to live, relatively speaking, “comfortably” in America. But let us imagine for a moment how his life could or would have looked like if some things had been different. Because Georges was a family man – even as a grown man he lived with or near his parents (granted, their living arrangements were normally quite spacious, so …), he married the daughter of one of his father’s friends and colleagues, he followed his fathers into the military and in politics, he cared for his mother, he accompanied his father to America – what would happen if his family had died during the French Revolution? Not only his mother and father but maybe even his sisters? Chances were rather high, Adriennes life was threatened by illness and the guillotine (her grandmother, mother and sister were all guillotined) and La Fayette’s life was threatened by illness, the French warrant for his arrest and his status as a Prisoner of War in both Prussia and Austria.

This questions “how would Georges’ life look like” is not completely theoretical. When Adrienne send her son to America, she wrote both to James Monroe and to George Washington and her letters make it clear that she had planned for the eventuality that Georges maybe had to stay for a very long time in America.

Adrienne wrote in an undated letter, probably from November of 1794, to James Monroe:

I ask him kindly to look after my son. I want him to finish his education in an American house of commerce. It would appear to me preferable to set him up at the residence of a consul of the United States. I want him to join their navy, and if it is absolutely impossible for him to begin his first line of duty at sea on an American vessel, I would have him serve on a French merchant ship.

I encourage the minister of the United States to recall that my son was adopted by the state of Virginia in 1785, and that he still has his certificate as a citizen of that state. I foresee therefore no difficulty in his entering the service of this second country, friend and ally of the French Republic.

Papers of James Monroe, 3: 165; Bookmen’s Holiday, x: 20

She wrote secondly in a letter to George Washington on April 23, 1795:

Sir, I send you my son. (…) it is with the deepest and most sincere confidence that I put my dear child under the protection of the United States, which he has ever been accustomed to look upon as his second country, and which I myself have always considered as being our future home under the special protection of their President with whose feelings towards his father I am well acquainted.

The person [Félix Frestel] who accompanies George, has been, since our misfortunes, our support, our protector, our comfort, and my son’s guide. My desire is that he should continue to direct him, that, until his arrival, my son should remain privately in M. Russell’s [Joseph Russell] house, that, once united, they should never separate and that we may have some day the happiness of meeting all together in the land of liberty. To the noble efforts of that friend, my children owe the preservation of their mother’s life. (…) While receiving from him each day the examples of the most generous virtues, his heart was being formed for those noble feelings which have preserved and always will, I hope, preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison. The last sacrifice which this friend has made for us is that of separating himself from a family he dearly loves. (…) My wish is that my son should lead a very secluded life in America, that he should resume his studies interrupted by three years of misfortunes, and that, far from the land where so many events are taking place which might either dishearten or revolt him, he may become fit to fulfil the duties of a citizen of the United States whose feelings and whose principles will always agree with those of a French citizen. (…)

Noailles Lafayette

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, pp. 317-322.

I shortened the letter in some parts but there is a complete version under the cut for everyone who is interested.

Adrienne gives very detailed instructions, how Georges should be brought up. In short, she wants him to:

Continue his education under Frestel’s tutelage, without too much ado

Start an apprenticeship, I believe, in a house of commerce

Work on an American merchant ship, or, if that is not possible, on a French merchant ship

Be the picture-perfect American citizen without forgetting his identity as a Frenchman

This is all pretty straight forward and we could end our little thought experiment here and take Adrienne’s instructions as the alternative life Georges could have lead. But I would like to elaborate on some aspects.

Félix Frestel

See, on this blog we appreciate Festel and all that he did. Adrienne herself wrote it in the letter to Washington how much the La Fayette’s owned to Frestel. He was Georges tutor long before the Revolution and likely also lived with him during this time. By all accounts he and Georges were close and Georges’ parents also liked and respected Frestel a lot. He risked his personal safety to hide George, helped Adrienne when her fate hung in the balance, he uprooted his entire life and left a family that he “dearly loved” to follow Georges to America – friendship and all things considered, this went clearly beyond the call of duty of a tutor. Adding to that my suspicion that he was not paid during the French Revolution. Both from a logistical and a financial point, paying Frestel would have been difficult and while we have letters from Adrienne to Monroe, asking him to do certain financial transactions for her, there is not letter from her reminding or asking him to pay Frestel. This is certainly no conclusive evidence but I have a very strong hunch.

In America, Frestel was father, friend and teacher for Georges and I am of the firm believe that he would not have easily deserted the boy, even if their stay in America would have been a longer one. I can think of two possible scenarios. One possible scenario would be that Frestel stayed with Georges until he boy would have reached his majority and finished his education in so far as that he was settled with an American merchant firm and learning there. Frestel might have returned then to France – he was free to do so, there was no warrant for his arrest and his name was not on the list of émigrés – and be reunited with his family. Since he was such a loyal soul and very devoted to his pupil, I could imagine him doing what Adrienne in reality did. Going back to France and trying to reclaim the possessions of the La Fayette family for Georges.

In the second scenario, Frestel decides to stay in America, possible because he had started his own family there. When he left France, he was unmarried and childless. It was therefor very possible for him to fall in love in America and decided to stay there with his family. Just as well he could take his wife and potential children with him back to France.

The Merchant Navy

While first reading Adrienne’s letters I found it quite peculiar that she was so insistent on the merchant navy. The merchants trade is one thing, but the service on a merchant ship means a live at sea and some potential dangers that you do not have, if you sit on dry land behind your desk. It could have been Georges expressed desire but since later in France as an adult he choose the Army over the Navy (and there is no indication that he ever considered the navy), I am somewhat doubting that. Life at sea however promised “adevntures”, comradery and occupation – all things that Georges would have needed and liked. Under British law, crew members of merchant ships were often pressed into the military service due to their skills and experiences. American law was different in that regard and Georges would not have worked as a common sailor, so he should have been all good on that front. Being at sea for long stretches of time was also making social engagements difficult. Adrienne had seen what politics can due to peaceful family life and she maybe intended to set Georges up in way where he would not join the politics of his time.

Being an American – Being a Frenchman

Adrienne herself wrote that she hopes her son “preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison”. Later in life, La Fayette wrote in a letter to his son that they should never forget, no matter what had happened or will happen, France is their country and their home. Georges was born and breed in Paris and he was a patriot. In the real turn of events, he would go on risking his life for France. The question therefor is, would he stay in America or return to France? Both are very real possibilities but, in our scenario, I lean more towards staying in America. We assume that his close family is dead (and with that more or less all family members on his father’s side) and many of his Noailles relatives were also dead or had fled the country (his mother’s father for example, he settled in Switzerland). He had extended family that settled into exile in Wittmold but even in reality he only joined them once his sisters and parents were freed and settled there as well. This extended family alone did not seem to be such a huge pull-factor for him. In our scenario he has nothing to return to, no family, no money, no title, no land – even if we assume that Frestel or Georges managed to get some of the family’s possessions back, they would have been empty, void of life and happiness. They would have been shadows, painful reminders of his former life and all that he had lost. Georges was utterly devoted to his family and to his father in particular. I do not think that he could just let go and start over without constantly lingering in the past. But then again, he was French. France was his home and everything that was left from his family was there in France. That again leads us to two possible scenarios.

In the first one, Georges stays in America. If someone was able to get some or all of the family’s former holdings back, he would maybe sell them and use the money to provide for the family he would (absolutely and definitely) start in America. He maybe would even start his own house of commerce. He could also use some of the money to provide for his father’s elderly widowed aunt still living in France. La Fayette had loved her dearly and vice versa. She would have been too old to come to America but Georges could find other means of making sure she was comfortable. He would inherit his father’s titles and probably not use them much, if at all, while in America. Instead referring to his father as “General La Fayette”

In the other scenario, Georges return to France, either with a wife he married while in America or he finds himself a wife in France. Either way, the girl in question would likely been the sister/daughter/niece/etc. of one of his father’s acquaintances. I could imagine that in France, and especially in Paris, even while serving in the merchant navy, there would have been high chances of Georges being caught up in his “old life”. In this scenario, I can very well see Georges enter politics and most importantly bump heads with Napoléon, just as his father would have done. But where Georges had his father’s opinions and views, he did not had his father later “immunity” towards Napoléon’s antipathy.

Anyway, this whole post has turned into a long “what if” rambling but if you made it to this point, I would be really interested to hear your opinions!

Adrienne to George Washington, April 18, 1795

Sir, I send you my son. Although I have not had the consolation of being listened to nor of obtaining from you those good offices which I thought likely to bring about his father’s delivery from the hands of our enemies, because your views were different from mine, nevertheless my reliance on your kindness is not diminished, and it is with the deepest and most sincere confidence that I put my dear child under the protection of the United States, which he has ever been accustomed to look upon as his second country, and which I myself have always considered as being our future home under the special protection of their President with whose feelings towards his father I am well acquainted.

The person [Félix Frestel] who accompanies George, has been, since our misfortunes, our support, our protector, our comfort, and my son’s guide. My desire is that he should continue to direct him, that, until his arrival, my son should remain privately in M. Russell’s [Joseph Russell] house, that, once united, they should never separate and that we may have some day the happiness of meeting all together in the land of liberty. To the noble efforts of that friend, my children owe the preservation of their mother’s life. Notwithstanding all the perils he encountered on his way, he made known to M. Morris the horrible situation I was in, and, after having had the courage to traverse the whole of France in those times of horror, following a prisoner, who was to all appearances devoted to death, he animated the zeal of the American minister to whose applications I probably owe that my sacrifice was deferred until the revolution of the 10th of Thermidor [July 28]. He will tell you that I have never given a pretext for any accusation against me, that my country can reproach me with nothing, and I myself will tell you that it is near him and with him that my son invariably learnt, even in the depth of misery, to discern between liberty and the horrors to which its name has been associated. While receiving from him each day the examples of the most generous virtues, his heart was being formed for those noble feelings which have preserved and always will, I hope, preserve in his soul, the love of a country where such dear victims have been sacrificed, where his father is disowned and persecuted, and where his mother was during sixteen months confined in prison. The last sacrifice which this friend has made for us is that of separating himself from a family he dearly loves. I ardently wish M. Washington to know what he is, and how much we are indebted to him. A letter will very in sufficiently fulfil my object. When shall I be able to do so myself? My wish is that my son should lead a very secluded life in America, that he should resume his studies interrupted by three years of misfortunes, and that, far from the land where so many events are taking place which might either dishearten or revolt him, he may become fit to fulfil the duties of a citizen of the United States whose feelings and whose principles will always agree with those of a French citizen. I shall not say anything here of my own position nor of the one which interests me still more than mine. I rely upon the bearer of this letter to interpret the feelings of my heart, too withered to express any others but those of the gratitude I owe to MM. Monroe, Skypwith, and Mountflorence for their kindness and their useful endeavours in my behalf. I beg M. Washington will accept the assurance etc.

Noailles Lafayette

The French original can be found here:

“To George Washington from the Marquise de Lafayette, 18 April 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-18-02-0041. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 51–54.]

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#french revolution#american revolution#american history#history#letter#georges de la fayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#1794#1795#george washington#james monroe#founders online#alternative history#felix frestel

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Washington delivered on his pledge to bring young Lafayette and his tutor into the household as long as Lafayette senior was imprisoned. Not surprisingly, Washington grew extremely fond of his young ward, whom he found 'a modest, sensible, and deserving youth.' The boy was tall, kindly, and charming and delighted all who met him. Like his father before him, he made rapid strides in English, surpassing even his tutor. When architect Benjamin Latrobe stopped by Mount Vernon for dinner, he was very taken with young Lafayette's savior faire: 'His manners are easy and he has very little of the usual French air about him...and seemed to possess wit and fluency.' Latrobe noticed that the president doted on the youth: 'A few jokes passed between the President and young Lafayette, whom he treats more as his child than as a guest.' The situation was further testimony to Washington's hidden emotional nature and his capacity to incorporate young people into his household as surrogate children.

Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow, pp. 738-739. I love the thought of this.

#George Washington#Georges Washington de Lafayette#Felix Frestel#Benjamin Latrobe#Washington: A Life#Ron Chernow#pp. 738-739

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

You ever thought about writing a little thing where Phil survived and went to France as planned and had a chance to become pals with Georges Washington Lafayette, and is still pretty close with Washy Custis and honestly, the fact the Hamilton kids and Washington grandchildren had played together as small kids kills me, and then that Georges knew Washy just wow, like alternate history it would have been entertaining to hear about the three of them together

That would be a blast to write! They certainly would have made for an interesting trio had they been able to get together as adults. Not only were Philip and Washy Custis playmates when they were young, but Philip did in fact also get the chance to meet Georges Washington Lafayette. When Adrienne sent Georges to America for his safety in 1795, he arrived in Boston with his tutor Felix Frestel intent on going straight to George Washington, who was still president at the time. However, with the relations between France and America being extraordinarily tense, Washington hesitated in inviting the boy to stay with him, worried it would cause a diplomatic incident. Hamilton held no official government position at the time, and he happily agreed to have Georges stay with him until Washington was sure it was safe for Georges to come to Mount Vernon. On December 24, 1795, for example, Hamilton wrote to Washington:

Young La Fayette2 is now with me. I had before made an offer of money in your name & have repeated it—but the answer is that they are not yet in want and will have recourse when needed. Young La Fayette appears melancholy and has grown thin. A letter lately received from his mother which speaks of something which she wishes him to mention to you (as I learn from his preceptor)3 has quickened his sensibility and increased his regret. If I am satisfied that the present state of things is likely to occasion a durable gloom, endangering the health & in some sort the mind of the young man, I shall conclude, on the strength of former permission, to send him to you for a short visit—the rather as upon repeated reflection I am not able to convince myself that there is any real inconvenience in the step and as there are certainly delicate opposite sides. But it will be my endeavour to make him content to remain away.

Georges stayed with Hamilton until the spring of 1796 (on and off–there was a point where Hamilton briefly lost him, which is also great story fodder :D). During that time, Georges and Philip, both close in age, would have gotten to know each other very well. Then, of course, Georges went to Mount Vernon and befriended Washy. If only they could have all three reunited at some point, I’m sure history would never have been the same! :)

#philip hamilton#georges washington de lafayette#george washington custis#the trio that could have been...#alexander hamilton#george washington#marquis de lafayette#prompt#history#ask

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you know about Georges Washington de Lafayette

All sources from Lafayette by Harlow Giles Unger:

Georges Washington de Lafayette was born on December 24th, 1779. Adrienne wrote to her husband rather icily at his army camp. She offered sarcastic recognition of her husband’s many responsibilities in the military, she scolded him or not being with her and their new child. The baby’s full name wsa Georges Louis Gilbert Washington de Motier Marquis de Lafayette, he would always call himself George Washington Lafayette. The one he was named after, George Washington, became his godfather.

May 1781, Adrienne wrote that Georges “nearly died teething” and left her “weakened by anxieties”. During Gilbert de Lafayette’s second-to-last visit to America in 1784-1785, his returning ship ran aground and repairs delayed his departure home for a week. General Greene and Henry Knox had come to see him off, and the three spent long hours together reminiscing with Alexander Hamilton. Lafayette urged Greene, Hamilton and Knox to send their boys to him in Paris for several years of European education. He promised in turn, he would send his own boy, George Washington to them. Lafayette said he wanted his son educated at Harvard.

Unlike other European parents, Adrienne and Gilbert did not keep their children at a distance with tutors; they adored their children openly, embraced them spontaneously and showed them off to all their guests. Benjamin Franklin listened with a smile as seven-year-old Anastasie and five-year-old George sang children’s songs in English. Georges used to also help his father attach his sheathed sword and other military trappings.

When Georges was ten years old, one guard unit sought to make him an honorary second lieutenant, his father turned the honor into theater: “Gentlemen,” he proclaimed to the assembled militiamen, “my son is no longer mine; he belongs to you and to our nation.”–and the troops roared as Georges stepped forward and stood at attention in his snappy-looking new uniform in the Paris guards. Felix Frestel was his tutor, starting when he was eleven years of age; he was a principal of the College de Plessis, his father’s secondary school, the Lafayettes retained him to tutor their son privately until he was old enough to enroll in classes.

During the Reign of Terror, while Gilbert de Lafayette was in prison and Adrienne was just being arrested. The police nearly to their home, Adrienne ordered a governess to flee with ten year old Virginie to a nearby farmer’s house, while thirteen year old Georges and his tutor Frestel rushed into the woods and fifteen year old Anastasie hid in a secret in cubby in one of the towers. Unaware of her husband’s fate, Adrienne (on house arrest) grew fearful for the survival her only son–the only person who could inherit his father’s name and fortune. Every once and a while, Frestel would descend from the mountain hideaway late at night and report on her son’s health and his future. They agreed on a plan to obtain a false license and passport as a merchant and go to the port at Bordeaux with Georges, who would feign the role of his apprentice.

When Adrienne was released by Elizabeth Monroe’s manipulation, James and Elizabeth Monroe both aided Adrienne in acquiring a fake passport, ID and changed Georges name in order for him to be able to travel to the United States undeterred. Monroe obtained government counterstamps on their passports for them to go to America, with the boy traveling as “George Motier.” Adrienne gave Frestel a letter for president Washington written in French, which she hoped the American president would be able to read and understand:

[Translated French-English] “Sir, I send you my son… It is deep and sincere confidence that I entrust this dear child to the protection of the United States (which he had long regarded as his second country and which I have long regarded as our sanctuary), and to the particular protection of their president, whose feelings towards the boy’s father I well know. The bearer of this latter, sir, has, during our troubles, been our support, our resource, our consolation, my son’s guide. I want him to continue in that role… I want them to remain inseparable until the day we have the joy of reuniting in the land of liberty. I owe my own life and those of my children to this man’s generous attention… My wish is for my son to live in obscurity in America; that he resume the studies that three years of misfortune have interrupted, and that far from lands that might crush his spirit or arouse his violent indignation, he can work to fulfill the responsibilities of a citizen of the United States… I will say nothing here about my own circumstances, nor those of one for whom I feel far greater concern than I do for myself. I leave it to the friend who will present this letter to you to express the feelings of a heart which has suffered too much to be conscious of anything but gratitude, of which I owe much to Mr. Monroe… I beg you, Monsieur Washington, to accept my deepest sense of obligation, confidence, respect and devotion.”

At Olmutz prison, Adrienne coaxed the prison commander to let her write to specific family members, whom she had identified with each letter obtain approval. He read every word she wrote and rejected a letter written to her son. The received occasional news from the outside, the rest of the Lafayette family heard Georges arrived safely in Boston in September of 1795. Adrienne did not know was that her son’s arrival plunged his godfather, the American president, into a potentially embarrassing political and diplomatic situation that posed dangers to the Lafayette family. George Washington was unable to publicly offered sanctuary to Georges in the America because the French might consider it a threat to their neutrality. Washington decided to leave the boy in New England until the government recessed later in the year and he could move to Mount Vernon. Washington asked Massachusetts senator George Cabot to enroll young Lafayette incognito at Harvard college, “the expense of which as also of every other means for his support, I will pay.” Washington also wrote to his godson: “to begin to fulfill my role of father, I advise you to apply yourself seriously to your studies. Your youth should be usefully employed, in order that you may deserve in all respects to be considered as the worthy son of your illustrious father.”

In America, Georges studied at Harvard, was a house guest of George Washington at the presidential mansion in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and at the Washington family home in Mount Vernon, Virginia. Young Lafayette chose to make his way to New York where he waited in hopes to join Washington in Philadelphia and lived with the Washington’s for the next two years. He also stayed with Alexander Hamilton in his New York home.

The Lafayette family, Georges’s two sisters, his mother and his father were released from prison in 1797, but it wasn’t until 1798 that Georges was able to return to France. In February, on a sunny day, Georges–who had just turned nineteen–arrived back in Europe to the embrace of his family; he also brought with him a letter from George Washington. His father had not seen him in six years. Initially at Cambridge, then a few weeks with Alexander Hamilton in New York, before going to the Washingtons in Mount Vernon after the president’s retirement. On his return to France, George first went to Paris, where he found only blackened stone shell of his beautiful boyhood home on the rue de Bourbon. George’s arrival in Holstein revived the spirits of all exiled families.

“He is perfect physically: tall, with a noble and charming face. His temperament is all that we could wish is all that we could wish. He had the same kind heart that you remember, and his mind is far more mature than is usual for his age.” Lafayette wrote to his Aunt. Virginie wrote to her as well, “My brother is grown so tall, that when he arrived we could scarcely recognize him, but we have found all those qualities in him that we always knew. He is just as good a brother as he was at Chavaniac. He is so like Papa that people in the streets can see immediately that his his son.” While attempting to retain the family land that the Lafayette’s lost when it was all confiscated, Adrienne returned to Paris for a second time to try at negotiation–this time she brought Georges with her, who, she believed might intimidate government clerks more than Virginie.

Georges also was a prod at his father, who was writing his Memoires and who would grow impatient when Georges wasn’t there to coax him to write it. Mid-1799, Gilbert grew impatient with Adrienne’s constant absences, “It is two years today, dear Adrienne, since we left the prison to which you came, bringing me consolation and life… How can we arrange our spending the winter together?”

In the Spring of 1802, George Washington de Lafayette married Emilie de Tracy, the daughter of Destutt de Tracy, a renowned philosopher who had served in the Constituent Assembly with Lafayette and as a cavalry commander under him at the frontier in 1792, just before Lafayette fled France. Pere Carrichon, the priest who had blessed three of Adrienne’s family members as they marched up to the guillotine, performed the ceremony. After the wedding, the Lafayette’s and the de Tracy’s went south together for a long visit to the Chavaniac–”to share our new found happiness with our old aunt, who still had all her faculties,” according to Virginie.

Italy rebelled against French rule and Georges and his brother-in-law were called to military service. His mother and his father were responsible for caring for his wife, she had just given birth to a little baby girl. He served as a second lieutenant in the French Army under Napoleon Emperor Napoleon blocked every promotion for Gilbert’s son and sons-in-law, prevented them from ranking up in the army despite the highest recommendations of their commanders. During one battle, George suffered a minor wound saving the life of General Grouchy to whom he was an aide-de-comp for and had given up his horse for during battle.

1805, Russia and Austria joined Britain in a new coalition against France, but French armies swept northward through Austria and crushed a combined Austro-Russian army at the decisive battle of Austerlitz in Moravia (now eastern Czech Republic). Two days later Austria sued for peace, and the Russian army limped home to Mother Russia to lick its wounds. In 1806, Napoleon destroyed the Prussian army at Lena and extended the French empire eastward to Warsaw. With peace at hand, with no chance for promotion, and with their military commitments complete, Georges Washington and his two brother-in-laws resigned their commissions. Although his father grumbled at the emperor’s pettiness, Adrienne rejoiced to have the boys home safely; she wanted no more knights in the family and reveled in the presence of the three young couples and their children, all of whom made La Grange their permanent home.

August 1807, Georges and his father went to visit the elder Lafayette’s Aunt Charlotte and inspect the Chavaniac properties. In their absence, Adrienne developed terrible pains and high fever; she began vomiting uncontrollably, unable to retain any food or liquid. They moved near Paris and Lafayette and George raced up from Chavaniac from La Grange. Both refusing to leave her bedside.

In March 1814, George introduced his father to the young duc d’Orleans. 1821, they both returned to their home on the rue d’Anjou. In his father’s later years Georges was always hovering at his side. Georges helped him with his Memoires and his voluminous correspondence. At six each evening, the courtyard bell sounded dinner, and as many as thirty people poured into the huge dining room–Lafayette’s children and grandchildren. Virginie and Anastasie sat opposite their father as hostesses, Georges always sat beside him. 1820, thirty nine year old Georges and Lafayette organized a group of young liberals into a new political club, Les Amis de la Liberte de la Presse. In the Autumn of 1821, King Louis XVIII posted spies outside La Grange, considering arresting Lafayette and Georges.

On Gilbert de Lafayette’s last trip to America, Georges accompanied him. “My brave light infantry!” his father cried out once, “That is exactly how their uniforms looked. What courage! How I loved them!” In an accident, a boat they were taking sunk and they were assured into lifeboats and rowed to shore. At bunker hill, Lafayette gathered soil from the ground, placing it into a tiny flask and told Georges to sprinkle the soil across his grave when he passed so that he would be apart of two countries when he was buried. Throughout most of the trip, he stayed close company with his father’s secretary, Auguste Levasseur. They visited Mount Vernon again and Georges got to meet Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. 1826, Lafayette and his son thought of America and sailed away towards home.

In 1832, Lafayette sent Georges back to La Grange to help Anastasie and Virginie cope with the needs of the family and the villagers,while he remained in Paris to help the government deal with the emergency. During the battle of the Bastille, Georges managed to hustle his father from the fighting and blood. After the death of his father, Georges Washington covered his father’s coffin with the dirt they gathered at bunker hill.

Georges Washington de Lafayette had five children total with his wife, Emilie de Tracy:

Oscar Thomas Gilbert Motier de Lafayette (1815–1881) was educated at the École Polytechnique and served as an artillery officer in Algeria. He entered the Chamber of Deputies in 1846 and voted with the extreme Left. After the revolution of 1848, he received a post in the provisional government; as a member of the Constituent Assembly, he became secretary of the war committee. After the dissolution of the Legislative Assembly in 1851, he retired from public life, but emerged on the establishment of the third republic, becoming a life senator in 1875.

Edmond Motier de Lafayette (1818–1890) shared his brother’s political opinions and was one of the secretaries of the Constituent Assembly and a member of the senate from 1876 to 1888.

Natalie de Lafayette who married Adolphe Périer, a banker and nephew of Casimir Pierre Périer.

Matilde de Lafayette who married Maurice de Pusy (1799–1864, son of Jean-Xavier Bureau de Pusy).

Clementine de Lafayette who married Gustave de Beaumont.

None can direct agnatic claim to the Lafayette name. It disappeared after Georges sons both died before having a male son. He spent the remaining years immediately following his father’s death organizing Lafayette’s letters, speeches and papers and compiling together his Memoires and more of his writing which was published in a six volumes in Paris in 1837-1838 he retained is seat in the Chamber of Deputies until the summer of 1849, remaining a loyal member of the ultra liberal minority his father had organized to oppose the restrictive dicta of King Louis Philippe. He lived to see the third French revolution of his life in 1848. 1848, Georges won reelection to his old seat in the Chamber of Deputies, but he failed to win the following year. He died in November 1849, never achieving the celebrity of his father.

#Flood Pressles box#Sincerely Anonymous#Marquis de Lafayette#Georges Washington de Lafayette#Georges Washington#Georges#Georges de Lafayette

178 notes

·

View notes

Note

did georges have any friends in america, i know he was trying to stay undercover but since he stayed with the hamiltons a bit he had philip who was in close age, and other kids in the hamilton house that georges could’ve talked to. i’m very interested in georges but I can’t seem to really find anything about his stay in america besides the letters with washington and hamilton♥️

Dear Anon,

thank you for the question. I really like to see all the interest that Georges received lately on this blog!

While it is true that Georges (born December 24, 1779) was quite close in age to Philip Hamilton (born January 22, 1782) I do not believe that were that close. I have never seen any source, letters for example, that suggested that the two were close. Georges stayed only a short time with the Hamilton’s and his and Philip’s friendship therefor would have to develop quickly. I am not an expert on the Hamilton’s, so somebody correct me if I am wrong, but I believe that Philip was during this time quite busy with his studies and he and his younger brother Alexander Hamilton jr. only spend the weekends with their family. If I am correct, Georges would have little interaction with the two oldest boys. He himself was busy continuing his studies and was overall in a dark state of mind. Georges, still almost a child, had gone through a series of life-changing events and did not seem to be in the mood to socialize or to find new friends. Even if he forged meaningful connections with the Hamilton children, they did not make him feel better. Hamilton wrote on December 24, 1795 to George Washington:

Young La Fayette appears melancholy and has grown thin. A letter lately received from his mother which speaks of something which she wishes him to mention to you (as I learn from his preceptor) has quickened his sensibility and increased his regret. If I am satisfied that the present state of things is likely to occasion a durable gloom, endangering the health & in some sort the mind of the young man (…).

“From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, 24 December 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 19, July 1795 – December 1795, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1973, pp. 514–515.] (06/28/2023)

When Georges came to live with his godfather George Washington, he seemed to have formed a close bond with Elizabeth “Eliza” Parke Custis Law and Eleanor “Nelly” Parke Custis Lewis. The two sisters were the children of John Parke Custis, Martha Washingtons only surviving son and George Washingtons adopted son. The relationship with Nelly appears to have been especially close.

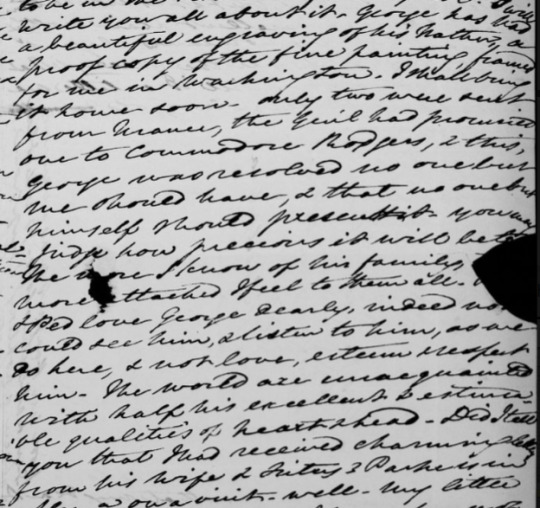

Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis wrote on January 26, 1825, to her friend Elizabeth Bordley Gibson:

Georges has had a beautiful engraving of his father, a proof copy of the fine painting, framed for me. I shall bring it home soon – only two were sent from France, the Genl had presented one to Commodore [illegible], & this, George was resolved no one but me should have, & that no one but himself should present it. You may judge how precious it will be to me [paper torn] I know of his family, [paper torn] more attached I feel to them all. [paper torn] [illegible] love George dearly, indeed no one could see him, & listen to him, as we do here, & not love, esteem & respect him. The world are unacquainted with half his excellence & estimable qualities of heart & head – Did I tell you that I had received charming letters from his wife & sisters (…)

Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis, Woodlawn, to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson, Philadelphia, 1825 January 26, A-569.110, Box: 4, Folder: 1825.1.26. Elizabeth Bordley Gibson collection, A-569. Special Collections at The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon. Accessed June 28, 2023.

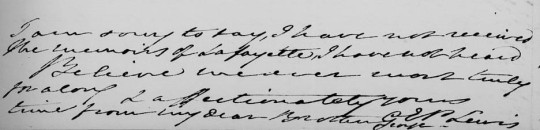

Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis wrote on December 25, 1838, to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson:

I am sorry, I have not received the memoirs of Lafayette. I have nor heard for a long time from my dear Brother George.

Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis, Woodlawn, to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson, Spruce Street Philadelphia, 1838 December 25, A-569.161, Box: 5, Folder: 1838.12.25. Elizabeth Bordley Gibson collection, A-569. Special Collections at The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon. Accessed June 28, 2023.

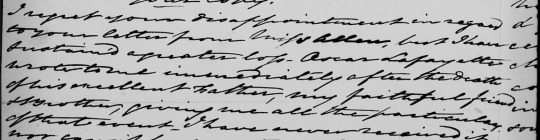

Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis, wrote on August 4, 1851 to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson:

I regret your disappointment in regard to your letter from Miss Below [?] but I have sustained a greater loss – Oscar Lafayette wrote to me immediately after the death of his father, my faithful friend & brother, giving me all the particulay of that event.

Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis to Elizabeth Bordley Gibson, 1824 October, A-569.104, Box: 3, Folder: 1824.10.00. Elizabeth Bordley Gibson collection, A-569. Special Collections at The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon. Accessed June 28, 2023.

There are several letters from Nelly, Eliza and Georges in the special collections at the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon. Most of them are from the time of La Fayette’s American Tour of 1824/25 or from later years. But there are also two farewell letters from the time that Georges and his mentor Felix Frestel left the Washingtons. While Eleanor’s letters in particular are mostly digitalized, Georges letters are only published with short summaries or keywords. I therefor mainly focused on Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis’ descriptions of her and Georges’ relationship but all that we have suggests that Georges felt the same.

While he was not a friend Georges made in America, we should not forget Felix Frestel, the man who accompanied Georges to America. Employed as Georges’ tutor prior to the French Revolution, the young man soon surpassed himself in the fulfillment of his duties. What he did for Georges, and indeed the whole family, carried a great personal risk. Once in America, he was Georges’ father, and mother, teacher, mentor, advocate, protector and friend. Georges and his family never forgot what Frestel had done, and the two families remained very close. Georges would later refer to Frestels younger son in a letter to Monsieur Guittére dated April 12, 1832:

(…) a young friend of mine, whom I love as I would love a younger brother.

Archives départementales de Sein-et-Marne - La Fayette, une figure politique et agricole (05/16/2022).

Washington commented in a letter to La Fayette from October 8, 1797:

Mr Frestal has been a true Mentor to George. No Parent could have been more attentive to a favourite Son; and he richly merits all that can be said of his virtues—of his good sense—and of his prudence. Both your son and him carry with them the vows, and regrets of this family, and of all who know them.

“From George Washington to Lafayette, 8 October 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 390–391.] (06/28/2023)

I hope that helped and I hope you have/had a lovely day!

P.S.: You mentioned that you find it hard to come across information about Georges’ stay in America. A week or so ago I had an ask about some general resources concerning Georges – maybe that was you or maybe you have seen it. If not, you might find this post useful. :-)

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#history#french revolution#letter#georges de la fayette#founders online#alexander hamilton#philip hamilton#martha washington#george washington#felix frestel#1779#1782#1795#1825#1838#1851#oscar de la fayette#john parke custis#elizabeth parke custis law#eleanor oarke custis lewis#elizabeth bordley gibson#handwriting

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

what was georges lafayettes and alexander hamiltons relationship? and do they have any letters together?

Dear Anon.

thank you for the question. I am really happy that I got so many Georges-asks recently – he deserves his time in the spotlight. :-)

I think the relationship between Alexander Hamilton and Georges can best be described as “caring”. It was by far not the same father and son like caring that Georges’ father La Fayette had with George Washington, but Hamilton was under no obligation to take Georges in. Nobody would have thought worse of the Hamilton’s if they had not housed Georges and his tutor Felix Frestel – but they did so anyway.

There were some bumps in the rode though and a certain level of distance or stiffness. Georges and Frestel still moved around a bit before they finally settled with the Hamilton’s and Hamilton was at one point not even quite sure where Georges and Frestel were.

Georges continued to express the desire to move in with Washington and Washington very much reciprocated the sentiment – staying with the Hamilton’s indefinitely was never an option.

As to letters – I know of no letters between Georges and Hamilton. I just had a look to be sure, but neither the Library of Congress, FoundersOnline nor any of my other sources have letters between the two of them. Georges and Frestel tried long to keep a low profile and many letters, not just to Hamilton, were not send straight away. Out of the few letters that were written, probably none survived. But maybe the Hamilton-crowd does know more, and they have some sources that I am not aware of?

Anyway, there are a few letters between George Washington and Alexander Hamilton where they talk about Georges. I will put them under the cut for you.

I hope I could help and I hope you have/had a wonderful day!

Hamilton to Washington, October 16, 1795

Hamilton to Washington, October 26, 1795

Washington to Hamilton, October 29, 1795

Washington to Hamilton, November 10, 1795

Washington to Hamilton, November 18, 1795

Hamilton to Washington, November 19, 1795

Washington to Hamilton, November 23, 1795

Hamilton to Washington, November 26, 1795

Washington to Hamilton, November 28, 1795

Washington to Hamilton, December 22, 1795

Hamilton to Washington, December 24, 1795

Hamilton to Washington, December 30, 1795

Washington to Hamilton, February 13, 1796

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#french revolution#american history#history#letter#founders online#georges de la fayette#felix frestel#1795#1796#alexander hamilton#george washington

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello again! I was just wondering if you could tell me about the time where Lafayette's son was staying with the Hamilton's because Washington couldn't take him in right away due to the political and national outbreak that was going on?

Dear @yr-obedt-cicero

thank you for the question, I think Georges’ years in America are extremely interesting. The only problem, details are hard to come by. It is a crying shame that Georges never wrote his own memoirs. The memoirs of family and friends (his father’s, Virginie’s and Cloquet’s memoirs) mostly only focus on his time with Washington, often not even mentioning Hamilton and most other sources followed this approach. I wrote a post about Georges’ time in America in my “La Fayette in Prison”-series. I covered his journey to America, his time with Hamilton, with Washington and with other people as well as his return to France. Maybe that post interests you.

As to Georges’ stay with the Hamilton’s in particular, as I just said, there is little detail that I can give you. His letters from the time are very carefully constructed and it appears that he did not like to elaborate on his stay in America later in life. When he accompanied his father in 1824/25 there is little to indicate that Georges was reminiscent of his last stay in North America. He did not comment on meeting the Hamilton-children, with whom he lived for a time and grew up, again.

What first came to my mind is this excerpt from a letter Hamilton wrote to George Washington on December 24, 1795, Georges’ birthday:

Young La Fayette is now with me. I had before made an offer of money in your name & have repeated it—but the answer is that they are not yet in want and will have recourse when needed

Young La Fayette appears melancholy and has grown thin. A letter lately received from his mother which speaks of something which she wishes him to mention to you (as I learn from his preceptor) has quickened his sensibility and increased his regret. If I am satisfied that the present state of things is likely to occasion a durable gloom, endangering the health & in some sort the mind of the young man, I shall conclude, on the strength of former permission, to send him to you for a short visit—the rather as upon repeated reflection I am not able to convince myself that there is any real inconvenience in the step and as there are certainly delicate opposite sides. But it will be my endeavour to make him content to remain away.

“From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, 24 December 1795,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 19, July 1795 – December 1795, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1973, pp. 514–515.] (09/26/2022)

During this time of his life, Georges had hit bottom low. Hamilton had a troubled childhood himself and knew full how Georges must have felt. He and Eliza were furthermore devoted parents and had adopted/fostered children before. Later letters show that Georges improved - although it is hard to determine the exact extent of the Hamilton’s influence on that matter.

In short, Georges (and Felix Frestel) stayed with the Hamilton’s. Georges was not well, and the family tried to support him as best as they felt they could. He never spoke much about his time in America and most sources focus on other aspects of his stay there.

I hope I could help nevertheless, and I hope you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#yr-obedt-cicero#georges washington de lafayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#history#letter#french revolution#felix frestel#alexander hamilton#elizabeth hamilton#george washington#1795#founders online#memoirs#or the lack thereof

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

okay, quick question: how old was frestel when he came to the u.s. with georges? I stg I was reading stuff about georges' stay there and when i tried to imagine frestel my mind completly stopped workimg cause of this lmao. thankss =)))

Dear @msrandonstuff,

your question comes as quite a peculiar coincident. As it is, I have a lengthy and, I hope, detailed post about Félix Frestel and his family scheduled for this afternoon (afternoon in my time zone.) But to answer your question, I do not know the exact date of Frestel’s birth and therefor can not give you an exact age at which he came to America with Georges. Based on descriptions of him and the age of his children, I would estimate that Frestel was in his late twenties to early thirties when he came to America.

Not the clear answer that I would like to give you, but I nevertheless hopes that gives you a more concrete image of Félix Frestel.

I hope you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#felix frestel#georges washington de lafayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#american history#french history#french revolution

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The (early) Relationship between Georges de La Fayette and Louis Philippe I

Lately I have gone back to “the roots” so to speak – in other words, I have read the French version of La Fayette’s memoirs (and again realized that the first English version I read was somewhat strange.)

While reading, I found this passage in the fifth volume:

Je ne con les ducs d'Angoulême et de Berry; mais la manière dont le duc d'Orléans demanda de mes nouvelles à mon fils, qu'il avait vu aux États - Unis , me fit un devoir d'aller chez lui

My translation:

I don't know the dukes of Angoulême und de Berry; but the manner in which the Duc d’Orléans inquired after my son, whom he had seen in the United States, made it my duty to go to him.

Most of you are probably aware of the fact that the relationship between the La Fayette’s and the d’Orléans’ often was … interesting to say the least. The Marquis de La Fayette and the Ducs father, Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans or “Philippe Égalité” really did not get along during the French Revolution. In that context it is quite interesting to see how their sons connected.

During the course of the French Revolution Louis Philippe II was executed via the guillotine and his sons fled the country. His oldest son, the new Duc d’Orléans, the one mentioned in the quote above, lived in Switzerland before moving to England and later spending two years in North America, mostly in Philadelphia. In April of 1797 he and two of his brother visited Mount Vernon in Virginia before embarking on a three-month trip of the American backcountry. By October they had concluded their trip and George Washington noted in his diary for October 30, 1797:

30. Wind brisk from No. Wt. & cold. Mer. at 54. Doctr. Stuart went away after breakfast. Mr. Cottineau & Lady, Mr. Rosseau & Lady, the Visct. D’Orleans, & Mr. De Colbert came to Dinner & returned to Alexa. afterwards. A Mr. Stockton from N. Jerseys came in the afternoon.

“[Diary entry: 30 October 1797],” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 6, 1 January 1790 – 13 December 1799, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979, pp. 265–266.] (09/29/2022)

By late 1797, Georges and Felix Frestel had begun their preparations to return to Europe but Georges would not be reunited with his family prior to February of 1798. I am therefor not quite sure if Georges and the Duc d’Orléans met during one of the described instances or elsewhere. Georges certainly had spent his fair share of time in Philadelphia as well.

One way or the other, the two young Frenchman in exile met and seemingly got along quite nicely. I have sadly never found a statement by Georges himself on the meeting or their subsequent relationship.

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#american history#french history#french revolution#history#1797#george washington#georges washington de lafayette#louis philippe#louis philippe i#duc d'orléans#founders online

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just saw your post about the letters between George(Lafayette) and Jackson so I had to ask this question

Out of all five of the Lafayettes (Gilbert, Adrienne, and their three children) who had the best handwriting in your opinion?

Or maybe any others who were close to them that you think had a good handwriting?

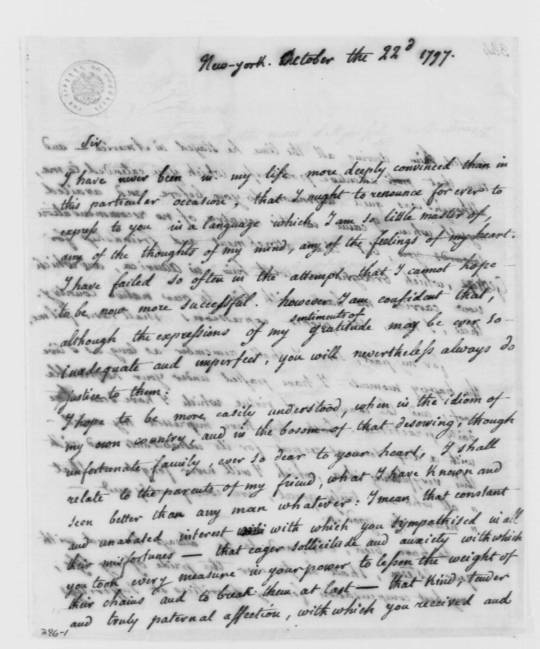

And here we are for round two, my dear Anon!

Félix Frestel was Georges’ tutor and brought him to America during the French Revolution. The Library of Congress has a small number of letters from Frestel, mostly to George Washington.

Félix Frestel to George Washington, October 22, 1797, (English).

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Felix Frestel to George Washington. 1797. Manuscript/Mixed Material. (05/23/2022)

Last but not least, Auguste Levasseur. He was La Fayette’s secretary and we have quite a sizable stack of letters, mostly between him and Georges Washington de La Fayette.

Auguste Levasseur to Georges Washington de La Fayette, January 7, 1826, (French).

Lafayette Manuscripts, [Box 1, Folder 32], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. (05/23/2022)

After I have let you all suffer through these examples, lets summaries what we have seen. I think my most favourite handwriting is Levasseur’s. Following Levasseur is either Adrienne’s (particularly the one in English) or La Fayette’s handwriting. I can not quite decide between the two of them. An honourable mentions goes to Georges and Edmond. :-)

That was my unnecessary long opinion on historic handwritings, I hoped that was what you were looking for and I hope you have/had a fantastic day!

#ask me anything#anon#letters#handwriting#1826#1797#george washington#georges washington de lafayette#félix frestel#auguste levasseur#history#french history#marquis de lafayette#la fayette

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

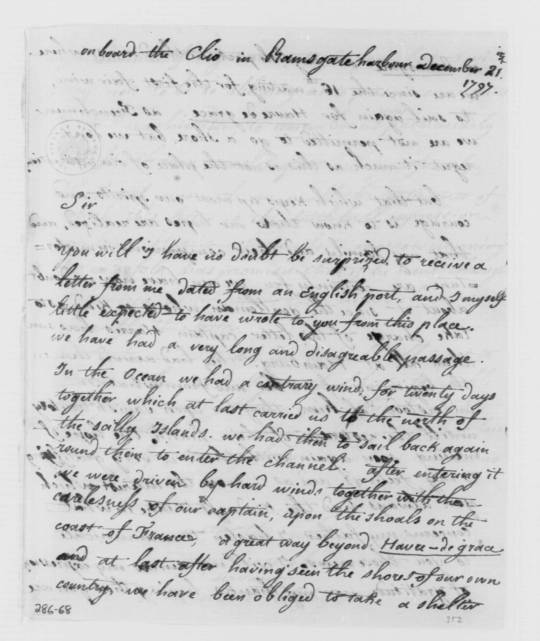

24 Days of La Fayette - Day 21

This one is a little bit out of the ordinary :-)

From Georges Washington de La Fayette to George Washington

[on board the Clio in Ramsgate harbour

December 21irst 1797.]

Sir

You will I have no doubt be surprized, to receive a letter from me dated from an English port, and I myself little expected to have wrote to you, from this place, we have had a very long and disagreable passage. In the Ocean we had a contrary wind, for twenty days together which at last carried us to the north of the scilly Islands. we had then to sail back again round them to enter the channel. after entering it we were driven by hard winds together with the carelesness of our captain, upon the shoals on the coast of France, a great way beyond Havre-de grace and at last after having seen the shores of our own country, we have been obliged to take a shelter in Ramsgate on English port in the downs, where we are since the 16th waiting for the first fair wind, to sail again for Havre de grace. as Frenchmen we are not permitted to go a shore, but we don’t regret it much as this is not the place of our destination.

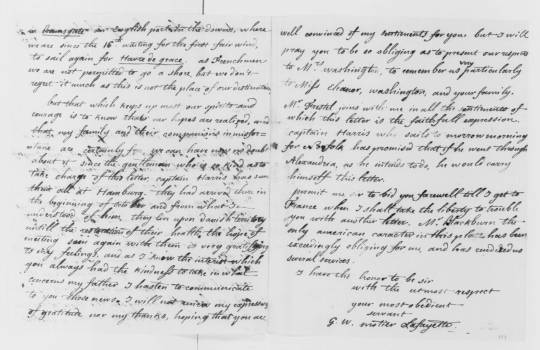

but that which keeps up most our spirits and courage is to know that our hopes are realized, and that my family and their companions in misfortune are certainly free, we can have now no doubt about it since the gentleman who is so kind as to take charge of this letter, captain Harris has seen them all at Hamburg. they had arrived there in the beginning of October and from what I understood of him, they live upon danish territory untill the restoration of their health. the hope of meeting soon again with them is very gratifying to my feelings, and as I know the interest which you always had the kindness to take in what concerns my father I hasten to communicate to you those news. I will not renew my expressions of gratitude nor my thanks, hoping that you are well convinced of my sentiments for you, but I will pray you to be so obliging as to present our respects to Mrs Washington, to remember us very particularly to Miss Eleanor, Washington, and your family. Mr Frestel joins with me in all the sentiments of which this letter is the faithfull expression. captain Harris who sails to morrow morning for Norfolk has promised that if he went through Alexandria, as he intends to do, he would carry himself this letter.

permit me sir to bid you farewell till I get to France when I shall take the liberty to trouble you with another letter. Mr Blackburn the only american caracter in this place has been exceedingly obliging for me, and has rendered us several services. I have the honor to be sir with the utmost respect your most obedient servant

G. W. motier Lafayett

#24 days of la fayette#marquis de lafayette#american history#french history#french revolution#la fayette#george washington#georges washington de lafayette#1797#letter#handwriting#founders online#felix frestel#library of congress

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Fayette in Prison - Part 4.2 - Adrienne in Paris

After six months the dreaded news came. Adrienne was to be transferred to Paris. Virginie wrote:

My mother arrived in Paris on the 19th of Prairial, the eve of the fete de l'Étre supréme, three days before the decree of the 22nd, which organized une terreur dans la Terreur. At that time, no less than sixty people were daily falling victims of the Revolutionary Tribunal. All seemed to forebode approaching death to my mother.

Her children were allowed to visit her one last time and her oldest daughter, Anastasie, argued and pleaded with the guards that she was old enough to be taken with her mother to Paris, that she was an adult and guilty of the same “crimes” as her mother. Anastasie was fifteen at this point in time and the guard refused her, although they were visibly touched by her plea.

Frestel, well aware of the imminent danger, wrote Morris in Paris and informed him about the situation. Morris lost no time and immediately demanded Robespierre himself to release Adrienne - he was ignored. Morris had previously been quite open about this dislike for the revolution and was therefore not really welcomed. He however made it very, very, very clear, that the Americans were quite attached to La Fayette and his whole family and that if, should anything happen to Adrienne or the children, this could quite possible be the final straw for the Americans. He said, and I paraphrase here, Morris himself was a tad more diplomatic, “Our rebellion against England started with a trade boycott. America is one of the last countries that still trades with France. The American government is and will remain neutral, but if something were to happen to Adrienne or her children and the American people start boycotting French goods, well, what is the government supposed to do?” After that, Morris was even more hated by the Jacobins but his initiative proofed to be successful. Adrienne remained in prison but it was made clear that she should not be executed. Americas neutrality was nothing that France could afford to lose.

Frestel had furthermore collected all the jewellery that still reminded in Chavaniac and sold most of it, so that Adrienne would have money while in prison. A number of the servants even gave some of their own money to Adrienne (have I mentioned how great and loyal and amazing the servants were?).

Adriennes mother, the duchess d’Ayen, her sister, the vicomtesse de Noailles and her grandmother, the duchess de Noailles were all executed early in July of 1794. Her mother and sister had fled to safety in Switzerland but decided to return to France to nurse Adrienne’s dying grandfather. After his death, the three women were arrested. Virginie wrote concerning their arrests:

My grand mother and my aunt de Noailles, who had remained along time at Saint - Germain, to take care of the Maréchal de Noailles in his old age, returned to Paris after his death, anxious to attend once more to their religious duties. They were, soon after their return, put under arrest in their own house, at the Hôtel de Noailles. The danger of their situation filled my mother's mind with terror and absorbed all her thoughts.

They died on the same day. Their local priest was able to get close enough to them to give them the absolution. He later noted that the two duchesses at least were content with their fate because they would both die before their child. On the day of the execution, the duchess de Noailles was the first to be guillotined, followed by her daughter, the duchess d’Ayen who in her turn was followed by her daughter, the vicomtesse de Noailles. A parent should not outlive their child.

I can not imagine what Adrienne must have felt as she received the news. All her live she had been extremely close with her mother and her older sister Louise. She furthermore could never be completely certain that she were not to follow her family members to the guillotine. Her American connections kept her safe for the time being, but that could change quickly.

The downfall of Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety was Adrienne’s salvation. More moderate forces took over the reign of government and less and less people were executed. Adrienne however was still in prison - and she did not know why. James Monroe, a close and dear friend of La Fayette had just taken over as ambassador from Morris and getting Adrienne out of prison was one of his top priorities. He could not risk a diplomatic misstep in his affair and he therefor did something very clever - he asked his wife Elizabeth Monroe if she would like to visit Adrienne. Elizabeth naturally agreed and soon the Monroe couple visited Adrienne on a regular basis and brought her all sorts of things she might need in prison. Their visits served two purposes (beside cheering poor Adrienne up). They made it clear that America was still very invested in the wellbeing of Adrienne and her family. They also kept Adrienne in the spotlight because it almost seemed as if the new government had simply forgotten that she was still imprisoned - and still without any reasonable charges. Adrienne wrote Monroe on October 3, 1794:

It is likely that I will be the last to leave this place. I believe that the threat of execution is subsiding and if hope persists, there is no danger for me, as I have not the least reason to be held. But the situation of my children so far away from me adds to the sorrow that will follow me to my grave. These cruel anxieties and this kind of torment not being completely without remedy, I beg you to ease my cares by allowing me a moment of conversation with a man who should have your full confidence. Nothing is easier than what I am asking you, and I cannot believe that you would refuse me. (…)I truly need you to look after the interest of my dear children from whom I have been torn apart. It isn’t too much I think after a two-month confinement in the same place, to ask for the consoling confirmation that I have some right to hope for my liberation at the moment of their arrival. You see, my dear sir, that I assume no pride in this because I sense that you have already enough assurances of my appreciation that I am ready for you to undertake new responsibilities. But, I am accustomed to remaining silent when I am not allowed to express openly what I feel. Pardon the candor with which I express myself to you; and doubt not that not only what the United States and its minister has done for me, but what they have willingly attempted to do for me, has instilled in me a very sincere appreciation.

There are many letters between Monroe and Adrienne, a few letters between Adrienne and Washington and only one letter between Adrienne and La Fayette (that I know of). Monroe did not only aided Adrienne in obtaining her release but he also helped her further with her finances and to take care of several relatives and former employees. Here is just one of the many, many examples. Adrienne wrote to Monroe in an undated letter (in all likelihood November 1794):

I cannot finish without recommending again to the kindnesses of the American minister, Mr Mercier, a servant who has served me for seventeen years with fidelity and zeal, and who has also run risks for me and shared with me a month in prison. He has a position at this moment, but I cannot bear the idea that he would suffer poverty. And I need to hope that he will not be abandoned by the United States. A very poor family whose son is the victim with my husband also has sacred claims to their kindness, the father, the mother and five children will be furnished of what aid that will relieve them.

Adrienne was not in a great position herself, but she constantly thought of others.

After a grand total of sixteen months in prison, Adrienne was finally released. Her immediate aim was to get her son and his tutor Frestel to the safe shores of America. She first re-purchased Chavaniac from the government so that Louise Charlotte and her children had a safe place to stay. She also argued with the government that she was eligible to inherit her mother’s properties - they eventually agreed with her. Monroe in the meantime had “found” an American passport for Georges. (Let me know if you all are interested in a separate post about Georges time and reception in America).

Adrienne and her daughters travelled to Austria, there to argue for La Fayette’s release - and that is exactly where we continue next time, with La Fayette’s stay in the infamous Olmütz prison.

#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#marquis de lafayette#general lafayette#historical lafayette#french history#french revolution#virginie de lafayette#anastasie de lafayette#georges washington de lafayette#felix frestel#france#paris#america#james monroe#american history#american revolution#history#letters#lafayette in prison#1794

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Fayette in Prison - Part 5 - Georges in America

Getting La Fayette’s and her son out of France was Adrienne’s top priority. The boy had, as their direct heir, the most to fear. The plan was to send Georges with his tutor Felix Frestel to the United States. With La Fayette already in prison, Adrienne and Frestel tried several times to set their plan into motion, but always to no avail. The French authorities were not very keen on letting La Fayette’s heir slip out of the country, to America no less, where they knew, they would never again get their hands on him. So the plan was postponed until Adrienne in her turn was freed from prison and the new American ambassador to France, James Monroe, had managed to get his hands on passports for Georges and Frestel. In an undated letter (probably around November of 1794) to Monroe, Adrienne explained her very detailed plans for Georges’ future.

(…) I entrust to the minister of the United States the following requests (…) 1. I ask him kindly to look after my son. I want him to finish his education in an American house of commerce. It would appear to me preferable to set him up at the residence of a consul of the United States. I want him to join their navy, and if it is absolutely impossible for him to begin his first line of duty at sea on an American vessel, I would have him serve on a French merchant ship. I encourage the minister of the United States to recall that my son was adopted by the state of Virginia in 1785, and that he still has his certificate as a citizen of that state. I foresee therefore no difficulty in his entering the service of this second country, friend and ally of the French Republic.

A few things about the letter. First, I do not know why Adrienne was so focused on sending Georges to sea. I could imagine that she wanted to prepare her son for the possibility that their family would not make it through the revolution. A house of commerce would teach him a respectable trade, a position in the navy could provide a stable income, the chance to rise through the ranks, comradery, and the service in the American navy would further tie Georges to America. Then there is also the resolution from the state of Virginia that she mentions. To my knowledge, only the state of Maryland declared in their resolution from December 24, 1784 La Fayette and “his heirs male for ever” citizen. It is at least the resolution that was cited in court cases up until 1955 - so I think that Adrienne simply confused the Maryland resolution with the Virginia resolution.

Adrienne also wrote a letter to George Washington where she told him that she had send her son to America and that she hoped the American people and George Washington in particular would take care of her son. She also repeated the sentiment that her son should finish his education and otherwise live a quiet and unassuming live like any other American citizen.

Georges travelled to America under the name of “Georges Motier”. For reasons of security, Frestel and Georges travelled separately. Joseph Russell, Jr., of Boston and his brother-in-law Isaac Winslow (1763–1806) helped Georges travel to Le Havre and board a ship to America there. Georges stayed in the house of Russell’s father (John Russell, 1734-1795) until Frestel joined him. Even after his arrival in America, the boy and his tutor were still laying low. So much so, that the congress passed this resolution on March 17, 1796:

The son of Lafayette

Mr Livingston called up the resolution, laid upon the table some days ago, respecting the son of Major General Lafayette; which after a few observations, and an alteration in the form of it, was agreed to as follows:

Information having been given to this House that a son of General Lafayette is now within the United States--

Resolved, That a committee be appointed to inquire into the truth of the said information, and report thereon; and what measures it will be proper to take, if the same be true, to evince the grateful sense entertained by this country for the services of his father.

Ordered, That Mr. Livingston, Mr. Sherburne, and Mr. Murray be appointed a committee, pursuant to the said resolution.

Although they tried to keep their arrival a secret, Frestel and Georges nevertheless reached out to various people and a number of people were aware of their whereabouts. Both of them had written George Washington on August 31, 1795. Henry Knox also wrote to George Washington from Boston on September 2, 1795:

(…) The son of Monsieur La Fayette is here—accompanied by an amiable french man as a Tutor—Young Fayette goes by the name of Motier, concealing his real name, lest some injury should arise, to his Mother, or to a young Mr Russel of this Town now in France, who assisted in his escape—Your namesake is a lovely young man, of excellent morals and conduct. If you write to him please to direct under cover to Joseph Russel Esqr. Treasurer of the Town of Boston—They will write by this post to you.

Washington, now being aware of Georges’ arrival in America, was unsure how to proceed. He wanted to take care of the boy (in one letter he wrote that he wanted to be a “Father—friend—protector— and supporter”) but he was also aware that the public entanglement of his father might harm his and Americas political neutrality and bring the country in a problematic position. Washington wrote George Cabot, a Senator from Massachusetts on September 7, 1795:

To express all the sensibility wch has been excited in my breast by the receipt of young Fayettes letter—from the recollection of his fathers merits, services and sufferings—from my friendship for him—and from my wishes to become a friend & father to his Son; are unnecessary. Let me in a few words, declare that I will be his friend; but the manner of becomg so considering the obnoxious light in which his father is viewed by the French government, and my own situation, as the Executive of the U. States, requires more time to consider in all its relations—than I can bestow on it at present—the letters not having been in my hands more than an hour, and I myself on the point of setting out for Virginia to fetch my family back whom I left there about the first of August. The mode which, at the first view, strikes me as the most eligable to answer his purposes & to save appear[ance] is, 1. to administer all the consolation to young Gentleman that he can derive from the most unequivocal assurances of my standing in the place of and becoming to him, a Father—friend—protector— and supporter. but 2dly for prudential motives, as they may relate to himself; his mother and friends, whom he has left behind; and to my official character it would be best not to make these sentiments public; of course, that it would be ineligable, that he should come to the Seat of the genl government where all the foreign characters (particularly that of his own nation) are residents, until it is seen what opinions will be excited by his arrival; especially too as I shall be necessarily absent five or Six weeks from it, on business, in several places—3. considering how important it is to avoid idleness & dissipation; to improve his mind; and to give him all the advantages which education can bestow; my opinion, and my advice to him is, (if he is qualified for admission) that he should enter as a student at the University in Cambridge altho’ it shd be for a short time only. The expence of which, as also of every other mean for his support, I will pay; and now do authorise you, my dear Sir, to draw upon me accordingly; and if it is in any degree necessary, or desired that Mr Frestel his Tutor should accompany him to the University, in that character; any arrangements which you shall make for the purpose—and any expence thereby incurred for the same, shall be born by me in like manner. One thing more, and I will conclude: Let me pray you my dear Sir to impress upon young Fayette’s mind, and indeed upon that of his tutors, that the reasons why I do not urge him to come to me, have been frankly related—& that their prudence must appreciate them with caution—My friendship for his father so far from being diminishd has encreased in the ratio of his misfortunes—and my inclination to serve the Son will be evidenced by my conduct reasons wch will readily occur to you, & wch can easily be explained to him will acct for my not acknowledging the receipt of his—or Mr Frestel’s Letter. With sincere esteem & regard I am—Dear Sir Your Obedt & obliged

Go: Washington

P.S. You will perceive that Lafayette has taken the name of Motier. Whether it is best he should retain it and aim at perfect concealment—or not, depends upon a better Knowledge of circumstances than I am possessed of, and therefore I leave this matter to your own judgment after a consultation with the parties.

I think this letter is incredible sweet and heart-breaking because it is just so obvious how eagerly Washington would like to take Georges in, were he not afraid about the diplomatic backlash. George Cabot replied to Washington on September 16, 1795: