#i was also trying out a different art program and ive never drawn on an ipad before so it all felt a little unfamiliar to me.

Text

Eliot and the stray cat he said they weren't keeping. (Click for better quality)

(Ficlet below the cut)

Eliot glanced up from his book when he heard Parker come in, then did a double take.

She was standing in the doorway, holding a cat. It was scrawny and wet and covered in mud.

"Look what I found in the alley." She said, her voice was sad and sympathetic, but underneath that there was a hint of excitement. "She needs a home."

Oh no. Eliot thought.

"We are not keeping the cat, Parker." He said firmly.

"Woah, who put you in charge?" Hardison asked indignantly.

"We can't have a cat running around here." Eliot insisted. “Not with how often we’re out of town.”

Parker looked disappointed.

"We'd Give the damn thing abandonment issues." Eliot muttered under his breath

"Well, we can at least give her a bath and some food." Hardison said.

Eliot's expression softened.

"It can spend the night. We'll give it a blanket to sleep on and leave it in the bathroom where it can't get into anything." Eliot said. "I'll take it to the shelter tomorrow."

"Shelter's closed over the weekend. Won't open again till Monday." Hardison pointed out.

Eliot groaned. "So we're stuck with it for the next 3 days?"

"Yup." Hardison said smugly.

"What should we call her?" Parker asked.

"No. No. We're not naming it. It'll just make it harder to say goodbye when the time comes."

"Aww, come on, can't we keep her? She needs a home and family to love her." Parker insisted. "And just look how cute she is!"

"They'll find it a good home at the shelter." Eliot said.

"Well, I guess I better go to the store and get some cat chow so she can have something to eat while she's here." Hardison said. "You two can handle giving her a bath while I'm gone."

Eliot rolled his eyes and got up to help Parker clean the cat off.

"Get a wet washcloth." He said. "I'll hold it still while you get as much of the mud off as you can."

Parker gently handed the cat to Eliot and ran to the other room. The cat let out a quiet broken meow that was barely more than a squeak as she passed it to Eliot. It clung to Eliot's arm with its claws, and he could feel the thing trembling. He wondered if it was cold or just scared.

Parker came back a minute later with a washcloth soaked in warm water. Eliot held the cat out so Parker could wipe away all the mud but after a while Eliot realized the washcloth wasn't going to be enough to get the cat clean. He sighed.

"It's gonna need a real bath." He said. “We’ll take it to the bathroom and do it in the tub.”

"She's not gonna like that." Parker pointed out.

The cat didn't mind nearly as much as Eliot expected. Or at least she didn't show it, maybe she was too exhausted or too scared to struggle. Her ears were pinned back in discomfort but she didn't put up a fight. She just sat in the tub, still clinging to Eliot's arm with her front paws as Parker rubbed soap into her fur. When Parker was done lathering the cat with soap Eliot helped rinse all the soap off, running his free hand over the cat's whole body as Parker poured warm water over it.

As Eliot ran his fingers through the cat's wet fur, he could feel scars. Most were old and long since healed up, but a few were more recent, still scabbed with blood.

"She's had a hard life, hasn't she." Parker said. "No family to love her, having to fight to survive."

"Yeah, seems like she has." Eliot said.

She's trying to guilt me into keeping it.

"She's old too." Parker pointed out. "Older animals are less likely to get adopted, you know."

Eliot sighed and shook his head.

I'm not going to let her guilt me into this. He told himself.

She was right though. The cat was old. Now that all the mud was gone, he could see that her face was covered in gray hairs. The rest of her was a dusty brown color with tabby stripes. She was a cute cat, he had to admit. She reminded him of the cat he had as a kid.

Eliot shook his head.

Can't let myself get attached. He reminded himself.

He grabbed a dry towel and gently rubbed as much of the water off as he could. Then he set the cat down on the ground.

"Do we really have to lock her in here?" Parker asked.

"She can wander around the back rooms until we go to bed." Eliot said reluctantly. "As long as we keep an eye on her to make sure she doesn't get into anything."

Parker's face lit up and she opened the bathroom door. No sooner had she done so, the cat scampered out of the bathroom into the livingroom and darted under the couch.

***

When Hardison got home, he found the cat wandering around, cautiously smelling everything. Parker was watching the cat intently and Eliot had his face in a book, paying no attention to the cat whatsoever, or at least pretending not to pay any attention.

"So I see the cat isn't actually staying in the bathroom then." Hardison said with a sly smile.

"She'll be put in there when we go to bed." Eliot said. "She's just hanging out out here while we can keep an eye on her."

Hardison smiled and poured a little food into the new bowl he had bought for the cat and when he looked up, he caught a dirty look from Eliot.

"What?"

"You bought the cat a new food bowl?"

"Yeah." Hardison shrugged.

"Damnit Hardison."

"She needs a dish!"

"The cat is not staying." Eliot insisted.

Hardison just rolled his eyes and set the bowl on the ground next to his feet.

The cat snuck cautiously up, but didn't come close enough to eat.

"Oops, excuse me little lady." Hardison said and backed away from the food bowl.

As soon as the cat decided Hardison was a safe distance away, she darted forward and began scarfing down the food, making happy little meows as she ate.

Parker and Hardison both chuckled at the muffled meows coming from the cat.

"I don't think I've ever heard a cat do that." Hardison mused.

I have. Once. Eliot thought, then quickly dismissed the thought.

As soon as the cat was done eating Parker tried to creep closer to pet her, but the cat darted away and sat down, wrapped her tail around her feet and stared at Parker.

"Aww it's okay little kitty." Parker promised. "I'm not gonna hurt you."

Parker sat down on the ground and scooted closer, but the cat moved away again.

"Parker, leave the cat alone." Eliot said without glancing up from his book. "She'll come to you when she's ready."

Parker reluctantly got up and settled herself on the couch between Eliot and Hardison.

***

Hardison stretched and yawned.

"Welp, I think it's time for me to get to bed." He said and got up from the couch. "Want me to put the cat up?"

"Nah, I got it." Eliot shrugged.

"Okay, night night." Hardison said and made his way up the stairs.

Parker got up to follow him.

"Good night, Eliot." She said.

"G'night."

"I really want to keep the cat." Parker said as she climbed into bed next to Hardison.

"Oh babe, we're keeping the cat." Hardison said definitely.

"But Eliot was very clear that he doesn't want to keep her. I know he's not the boss of us, but I feel like we should respect his opinion, right?"

Hardison wrapped his arms around Parker and pulled her close.

"Parker let me let you in on a little secret that Eliot would probably kill me for telling you. He'd never admit it, but he loves that cat already. He's growing more and more attached to her every second. We just have to pretend like we don't notice it for a while, let him think he’s got us fooled. Before ya know it, he’ll cave and let us keep her."

Parker smiled and snuggled in closer to Hardison.

“I think we should call her Snickers.” Parker said

“I like Snickers.” hardison mumbled sleepily. “But don’t tell Eliot till he’s agreed to keep her.”

***

Parker woke up again in the middle of the night and wondered if Eliot was still awake. She carefully slipped out of Hardison’s arm and crept down the stairs. She found Eliot curled up, sound asleep on the couch. The cat was curled up in the curve of Eliot's stomach, nestled into a pile of blankets, purring loudly.

So the cat’s not staying in the bathroom after all.

She smiled and crept back to the bedroom, nudged Hardison awake and motioned for him to follow her. Together they crept back to the living room.

Hardison chuckled quietly to himself when he saw Eliot asleep with the cat.

"What'd I tell you? He's in love with the cat already."

***

Monday rolled around, but Eliot didn’t seem to be in any hurry to take the cat to the shelter.

"Ya gonna take the cat today?" Hardison asked.

He already knew the answer was no. Eliot was completely and thoroughly attached.

"If I find the time." Eliot shrugged. "Kinda busy today, though."

Hardison and Parker shot each other knowing smiles.

"Well, I can take her if you want." Hardison offered, knowing full well Eliot wouldn't accept it.

"No, I'll do it as soon as I'm not busy."

***

When evening rolled around the cat was still wandering around the back rooms of the brewpub, but Eliot's day had proven to be much less busy than he said. He had worked out a little, gone over the brewpub menu to make a few revisions and taken one client meeting, but all of that took less than half the day.

There should have been plenty of time to take the cat to the shelter. Hardison noted smugly to himself. But he doesn't want to say goodbye.

***

Tuesday really was a busy day. They spent the whole day planning, and executing a heist and by the time they got home, the shelter was closed for the evening.

Eliot grabbed an ice pack from the freezer and pressed it to his aching shoulder. Then he slumped down onto the couch with a sigh and leaned his head against the back, closing his eyes.

The fight he had with the security guards hadn't been particularly rough, but one of them had managed to wrench his shoulder pretty bad. he had popped a couple painkillers on the way home, but it was still aching.

He looked up when he heard a tiny squeak from the cat as she jumped onto the opposite end of the couch and made her way over to him.

The cat never seemed to meow properly. It always came out more like a raspy squeak, as if she had lost her voice. He was reminded once again of the cat he had as a kid, the only other cat he had ever known who had a meow like that.

She rubbed her head against his leg and walked in circles across his lap a few times before laying down and curling up on his lap, purring softly. Eliot scratched behind her ears, and she started purring louder.

Damnit. He thought. She's not going anywhere, is she? We're stuck with her now.

***

Wednesday morning, Eliot woke to find the cat wasn't asleep next to him like she had been when he fell asleep. He got up and wandered into the next room where he found Parker, but the cat wasn't there. Neither was Hardison.

"Where's Hardison?" Eliot asked.

"Oh, He figured since we’re keeping the cat, it was probably time to take her to the vet and get her checked up. Ya know, make sure she doesn't have any illnesses or anything we need to know about. The only available time they had was first thing in the morning."

"Woah, we never agreed to keep..." Eliot trailed off and gave in, shaking his head. "Well make sure he knows to get a litter box while he's out."

Parker smiled and nodded.

"Damn cat." Eliot muttered fondly to himself as he set to work making breakfast.

“Also, we’re calling her Snickers.” Parker added.

Eliot smiled. He liked that name, mostly because Parker was the one who came up with it, but he liked it all the same.

#leverage#eliot spencer#parker#alec hardison#Snickers the cat#leverage fanart#Leverage fanfic#Leverage fluff#my art#it's been a while since I've done any digital art and boy did it feel nice to start again!#i was also trying out a different art program and ive never drawn on an ipad before so it all felt a little unfamiliar to me.#but i think it turned out okay#it took me a while to actually be satisfied with all this but i think im finally satisfied enough to post it.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

yippee carnival flicker!! ive been rotating them in my mind for a while now so im glad to have them drawn properly :D tumblr killed the quality tho so click on the image pretty please

i think i did good as bossifying her design! sm-baby (who made the au btw) had boss design notes that rlly helped!! i focused a lot on adding more details to differentiate carnival flicker from canon flicker (i also tweaked the colors a lil teehee)!

no-box art, doodles, & info dump below!!

About Their Game:

Pop Goes The Weasel plays in its entirety on the first round, with Flicker jumping out on the "Pop!" signaling the player to stop. In later rounds, the music cuts out at different points and the player must time the cue themself.

Their AI was adaptive, able to adjust each round's difficulty to the player's performance. Now they can control their game's difficulty manually, occasionally helping struggling players by moving platforms closer or humming when their music cue cuts out.

There's a hard mode of the level where the player has 1 HP, the platforms move around, and Flicker's music cue plays at varying speeds each time, on top of cutting out at random.

Ice makes platforms slippery, harder to land on & jump from. It's also harder to stop before a red light.

Electrified platforms can be landed on, but drain health the longer you stay on them.

Spikey platforms require careful timing to land on & jump off safely, taking a significant chunk of health if impaled.

Platforms with glue are harder to jump from, you won't have as much momentum.

Lose conditions: Falling into the void below the platforms, losing all HP, moving during a red light, failing to reach Flicker in time.

Fun Facts:

Due to a bug, players will always have spring-shoes equipped in Flicker's room, even in visiting mode.

Flicker's box has collision but no physics, & can no longer be interacted with after she broke off the crank. It's her ultimate safe space.

Prior to the broken crank, players could wind up Flicker's box in visiting mode & have them pop out on cue to start a conversation.

Non-sentient Flicker's AI would make references to their crush on Kinger. Sentient Flicker tends to stay quiet about it, almost never brings it up themself.

Gangle is the only other character who would reference Flicker's crush when non-sentient, even if Flicker wasn't present. She likes to tease them about it, casting Flicker & Kinger in romantic-leaning roles.

Flicker will put herself in increasingly more painful and embarrassing situations to entertain The King. She likes his laugh. Making him happy, even at her expense, is like a secondary purpose to her.

Believes Pomni's love is "real" because she developed it after becoming sentient, opposed to their own "fake" feelings that they were programmed with. Will need a lot of talks with Pomni before they consider their feelings for Kinger to be as real & valid as Pomni's feelings for Caine.

Has a lot of questions for the humans that made her, primarily about the reason for her existence and why she was given a crush on a married man (Made arguably worse by the fact said man is now a widower).

Flicker's room is one of the safest to be in since they aren't actively hostile toward humans. In fact, they'd go out of their way to protect a player actively participating in their game.

Since her game is all she feels she has, she may try to extend it indefinitely, adding more & more rounds with fluctuating difficulties. She doesn't want the moment to end. You'd have to promise to come back & play again before she finally lets you win.

Flicker's game, being adaptive & more forgiving, places them fairly early in the boss order, either before Ragatha or between her & Gangle. Being an early boss puts them in the mindset that no one will revisit them or their game since there's no progress to be made doing so.

Flicker's AI was made to shout words of encouragement & praise to the player depending on their performance & progress through the level each time she popped up. If her AI recognized the player was idling, she would remind them of the controls. If they weren't making it very far between green lights, she would encourage them to keep trying.

Sentient Flicker still does something similar, if only to get the player to keep playing & finish her game despite the danger. To quit partway through would be worse than to not play at all!

They can get snappy if you don't progress for a while though, shouting that it's not that hard, asking if you're even trying. They apologize quickly, not wanting to put you off from playing with their attitude, and will even offer to make the level easier if it'll keep you going.

#hi guys. theres a lot of text i love making flicker lore#i am Not good at drawing caine but i needed flicker to be existential at him bc he worked on the game#ik digital carnival is meant 2 be a vr game in universe But we can pretend they hva the tech to imitate jumping & platforming ok?#tadc carnival au#tadc#the amazing digital carnival#carnival au#carnival kinger#sona: flicker#sona: flicker (carnival)#man i wish there was a tag for like. au ocs. would love to see more ppls ocs auwauhh#my ocs#torchs art#jan 2024#id in alt text

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

im ngl noww that you say that you do art as a hobby, im just intrigued by how you are so confident and are able to have the free time to do it as a hobby...

i hope i didnt make a mistake taking art college ;; IM ROOTING FOR YOU TOO! its so luckily nowdays to have a job youre at least okay with but also have some really fun hobby on the side too

to one broke college student to another do u have any advice for future years? i ltrly just started college like 3 weeks ago

aaaa as far as time for the hobby goes, i actually only have that kinda time very recently (like over the summer and this semester).....if you noticed, i kinda dropped off for a year where i mustve only drawn like 10 things??? which is because last year was such a busy year for me in terms of work and courses...but this semester is better because im only in 3 classes: one doesnt have any exams and another im retaking (cuz i didnt pass the summer comp exam for it lol) so its all content ive seen before!! so this semester is a little easier and i can draw a bit more when i dont have homework or on the weekends!!!

as far as advice goes, (im not sure how art school works? or if youre in a normal university just majoring in art?) id say: take a lot of different classes to see what you like! explore different areas, and i think it might also be good to have like.....a contingency plan so to speak. like in my undergrad i got a minor in anthropology and almost got a certificate in accounting just so i had a little more options post-undergrad if the math major didnt work out!! so doing something like that is never a bad idea!!! (my undergrad program had a requirement to fulfill a certain amount of credits outside your major courses, so i used those to explore different things)

also dont be afraid to change if you feel you dont like your current path.....like i mentioned i was an astronomy major in undergrad first, and had wanted to go into astronomy since i was a kid, but found eventually it wasnt for me (i couldnt cut it in physics) and switched to something i wasnt SUPER passionate about, but i was good at it!! which was a huge decision for me and lowkey pretty risky (the fuck do you do with a math major?? everyone i asked they just replied "Oh you can do lots of things!" and never gave me an actual job title)

try to do summer internships if you can! as long as its financially feasible for you, itll make your resume a lot beefier when you graduate if employers/grad school see that you already have several experiences under your belt (and experience compounds on itself-- the more you have the more likely you are to get more!! for example here in my program, if you have more stats and coding experience coming in youre more likely to get more stats/coding assistantships, so you gain even more experience over the person who had no stats/coding experience prior and as a result got sent to be a TA or something. so the person who already had experience gets more experience and the person who didnt falls even further behind :') (me) )

networking is also important!!! since youre just in undergrad, i would recommend starting by talking to professors when you can. doesnt need to be like, going out of your way to go to their office hours and talk stories, but maybe chat a bit before/after class!! ask them how their weekend went, ask a dumb clarifying question!! i got to my current grad program because my professor came to me before class one day and said "I have a friend from [my current program] coming to recruit, you should go meet him." so be friendly with your professors so they get to know you and will pass on opportunities when they hear about them!!

a lot of professors get emails from all kinds of jobs/programs to the effect of "[place] is looking to recuit/hire" and they can pass those your way if youre on their radar!! and lastly work hard!!

(anyway this is advice i have based on my own experiences and what worked for me, it will most likely be different for you!! stay on top of your studies, but also force yourself to rest every so often!! I personally do not do any work on saterdays and try not to on sundays!! so i feel okay working hard the other nights of the week so i have two full days of rest....sacrifice your work-week free time for grades :') sometimes the best thing for your mental health is just getting the thing you dont wanna do out of the way!! good luck in uni!!!)

#college for everyone else is gonna be a little different than college for me#i was fortunate enough to get a lot of locally-based scholarships that took care of me so i didnt need to work while studying#but i know a lot of people do and thats fucking tough#i also wasnt in a lot of clubs etc#because my scholarship program would organize a lot of our events#and besides studying i didnt have time for any of that lol#stay on top of your studies for real.....#put down that pokemon game and go re-read the lecture content you learned today (pro tip)#yeah dont work 24/7 without rest if you can avoid it#burnout isnt fun and honestly i still havent figured out a way to avoid it#sometimes its inevitable and you just gotta push through#punch studies in the face

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philinda & Timelines

I wrote most of this in a more disorganized form a few months back, but now I’ve fleshed it out and done some more calculations. I hope it might be interesting to fans of these characters or useful for those who write fic for them. I personally like to have some dates and characterization timelines to look at when writing fics set in a “real world” type show, so I generally keep some notes for myself in word docs. Here I just kinda dove into it.

I don’t go into plot timeline details here because I just don’t care. Marvel does an incredibly shit job of taking travel time and medical times into account. They can try and convince me something happened in two weeks, but I’m always going to ignore it. This uses info from the show itself and from an online date calculator. I am mostly not pulling from the various wikis. The wikis are great for trivia, but they are massively self-contradictory due to tie-in comics, stuff said in various interviews, etc. It’s Marvel. [Edited 03/20 to finally include workable theories for Captain Marvel]

*

Phil Coulson was born July 8, 1964. This makes his sun sign Cancer and his Chinese zodiac year the Dragon. He was an active and outgoing kid who wished he had a brother to play with. His dad died or was killed in 1973. Coulson was only 9 years old. They’d either finished restoring Lola together earlier that year or in 1972. It is implied in season 2 that he and his mother moved after the death, either to a different part of the town or somewhere else entirely as he did not attend the high school his father worked at. Coulson finished high school and went to college to study history, both because that was the subject his dad taught and because he was always a giant history nerd. He worked as a lifeguard as a teenager. We do not know anything about his mother’s work or their relationship when she was alive. A research project into the S.S.R. brought him to Shield’s attention. He was recruited from college by Nick Fury, an agent at the time.

Melinda May was born November 20, 1965 (a reference from the scanned back-page of a tie-in comic I cannot find again - Fury’s Secret Files from somewhere I think). Obviously, they’ve just used Ming’s birthday with a different year to parallel the actors. Her birth location is always listed as classified, so it’s possible her mother was involved with something for the CIA at the time. Her sun sign is Scorpio and her birth year in the Chinese zodiac is the snake. May always picked up new physical activities quickly according to her dad in S3. She started ice-skating at 7 and quickly began skating competitively. At 12 she switched from skating to martial arts. May has a trusting relationship with both her parents. We don’t know anything about when they seemingly separated, decided to live separately for Reasons, or got divorced. There is around a year unaccounted for between when she most likely graduated high school and when she likely joined Shield. She might have joined against her mother’s wishes. We know nothing of how she was recruited.

Star Wars Episode IV came out in May of 1977. Coulson was 12 and May was 10. This is totally relevant information.

These dates mean May is just shy of two years younger than Coulson. More precisely, Coulson is 17 months older.

We know they were at the Academy together (Comms and Ops shared some classes and electives) and graduated at the same time because of 2x4. Comms and Ops would have been in different facilities, though reasonably close together for logistics purposes. There would be a significant amount of overlap for field agent hopefulls. They probably wouldn’t have seen each other every day. They probably usually saw each other multiple times a week, depending on their classes.

They also shared classes with future Agent Blake and Agent Garrett. (It’s important to remember that Agents Hand, Hartley, Sitwell, and Hill are younger in the MCU and did not attend the Academy until the previous four Agents had already left.)

From common practices in American educational law, Coulson very likely started school (kindergarten) in the fall of 1969 (at 5). He would have graduated in 1982 and started college that fall. It is also possible he started school in 1970 (at 6) and graduated in 1983. May likely started school in 1971 at 5 and would have graduated in spring 1984 at 18 or she possibly started school at 1970 at 4 and graduated in 1983 at 17. (At the time, starting kindergarten at 4 years old was common if you would be turning 5 soon. Start ages were lower in the 70s.)

Here’s where a couple different things could have happened.

I’m going to move forward here with the (imo) more likely graduation ages for them both. These aren’t official. These events could have happened a year earlier or a year later, but anything more than that would be very unlikely.

It’s spring 1984. Coulson just finished his sophomore year of college and is about to turn 21. May just graduated high school at 18.

We know the Shield Academies at this point were legitimate in the eyes of the U.S. Government, though mostly under the radar. There was enough of a structured curriculum schedule in place we know they had a yearbook (as of season 5). Taking on recruits under 18 generally requires parental permission, as Shield is still paramilitary.

Option 1 - Coulson’s research has already drawn Shield’s attention and he is approached by Fury. Someone recruits May or she becomes aware of Shield some other way. They start at the Shield academies fall of 1984. They are 21 and 18 when they join.

Option 2 - Coulson continues through his junior year of college. His research into the S.S.R. draws Shield’s attention. Fury goes to recruit him. May spends a year doing any number of things. Her mother might want her to pursue the CIA. May picks Shield. They start at the Shield academies fall of 1985. They are 22 and 19 when they join.

Option 3 - Coulson is about to finish college when he draws the attention of Shield and is recruited by Fury. May is an unknown for two years. They start at the Shield academies fall of 1986. They are 23 and 20 when they join.

Star Trek IV (the whale movie) came out in November of 1986. Coulson was 23 and May was just 21. This is also totally relevant information.

Let’s say MCU Shield’s training program lasted 3-4 years. (Fitzsimmons strongly implied in season 1 Seeds that Scitech usually took about four years.)

The absolute earliest (3 years) May and Coulson (and Garrett) should have been in the field was 1987/1988/1989. Their most likely brand-new Level 1 Agent year was 1988/1989/1990.

Coulson and May were most likely Level 1 agents at 23 and 21/24 and 22/25 and 23.

The Sausalito mission mentioned in episode 2x4 probably happened later in 1988/1989/1990.

John Garrett, who they were trained with, was injured in Sarajevo and became a Project Deathlok subject in 1990. He probably was only Level 2. He’d only been an agent 2-3 years maximum.

We knew from season 1 that Coulson’s mom Julie was long gone. The wiki puts her death as September 22, 1992, exactly 19 years after her husband’s death. Coulson was only 28.

This is where I take issue with one of the semi-official dates. Big issue.

We got a flashback to a younger Agent Coulson and Agent May in season 4. May was a Level 3 specialist and Coulson was recently Level 4. We know they knew each other pretty well at that point, enjoyed each other’s company, and also frequently went weeks or months without seeing each other. They worked on missions separately and together and kept track of each other through company gossip. It’s at this point in their lives that a little, badly-kept-secret, mutual crush is going on that is ultimately not pursued for multiple reasons. They stay close friends and work partners for the next 10-15 ish years.

Parts of the wiki claims this flashback was to 2003. However, this is basically a retcon and in my oh so professional and classy-sounding opinion is just dumber than fuck. (Also, that date was never used in the episode.)

The absolute latest Coulson and May started as field agents was 1990. So *13 years* later they’re still Level 3? I don’t think so. Level 1 is your entry level. Anyone who is performing well is only going to stay there 1-3 years max. Level 2 is your no longer a noob level. If you’re doing great work let’s say people stay there 2-5 years. Agents would stay longer in Levels 3/4/5 than Levels 1 and 2.

Let’s be generous and give them 5 years at Levels 1 and 2. It could have easily been 4, maybe even 3 depending on how fast they got their groove after the whole “in the bay for five hours” thing. Coulson and May logically made it to Level 3 anywhere around 1993/1994/1995.

The Captain Marvel movie makes dubious use of existing aos canon, but if we use the perspective that Phil is a brand new Level 3 field agent instead of one fresh out of the Academy (which is completely incompatible with aos’s timeline) than we can say Phil and May were new level 3 agents sometime early in 1995.

A sensible placement for the Russian 0-8-4 mission would be anywhere from late 1995-1997. With Phil having recently made Level 4 (strongly implied the the flashback), I would suggest 1996 or 1997 as the most likely placement.

From the tie-in comics, MCU Agent Barton is recruited by Nick Fury around this same time, Agent Romanoff “recruited’ by him a few years later.

By 2003, both Coulson and May should have advanced a Level again and be taking on more complex missions. Strike Team Delta is part of Shield now. Fury is Director.

The Bahrain mission happened in 2008. Coulson was likely a Level 6 operative and May would be Level 5. Coulson took a lot of orders from a lot of people in episode 2x17. I highly doubt he was Level 7 at that point. The agent in charge of the operation, Agent Hart, was one of the ones Katya took over. Big Shield headquarters forbade Coulson from sending May into the building. He gave her the clear to go anyway and covered for her. May was 42. Coulson was 43 or 44.

May worked on administration for mostly Level 3s in the basement of the Triskelion for the next 4.5 years. This does not mean she became a lower ranking agent; you would likely want a higher-than-3 managing your level 3s.

Coulson is sent to make contact with Tony Stark later in 2008. At some point he advances to Level 7 then 8. Given Shield viewed the Bahrain rescue as a legendary success, not knowing how it unfolded, it is reasonable to think Coulson was promoted to 7 shortly afterwards.

Coulson died on the Helicarrier on May 4th, 2012 during The Incident. He was 47. May was 46 when she found out he was dead.

When we met them in season 1, Coulson was recently 49 (technically…) and May was 47. May is a Level 7 agent and Coulson remains Level 8.

After season 5 they are on a beach in Tahiti. Coulson is 54 and May is 52. They’ve known each other 34/33/32 years.

*

Now, I’ve tried to structure this whole thing in a way that should you want to change their school-dates and use any of the three options you should be able to go through and add/subtract from the existing numbers pretty easily. So I hope that’s useful if you’ve been trying to math and write fic or if there’s just been general confusion.

I greatly prefer to write from the Option 2 set, with adjustments made for Captain Marvel. That just makes the most sense to me as far as events we know about from season one and the other life events for these characters. So if you’ve read any of my stuff, this is generally where I’m coming from.

I really hope this was useful and interesting. I spent far too much time on it.

#agents of shield#aos meta#philinda#phil coulson#melinda may#john garrett#loooong damn meta#omfg#why did i do this to myself#nevermind#i know why#and i will never admit how much of this i was able to write from memory#though I've double checked everything since#and#only a year later than planned#i've finally updated it for captain marvel tie in info lol#pinned now because i think this'll stay relevant for s7

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conversation with David Panos about The Searchers

The Searchers by David Panos is at Hollybush Gardens, 1-2 Warner Yard London EC1R 5EY, 12 January – 9 February 2019

There is something chattering. Alongside a triptych a small screen displays the rhythmic loop of hands typing, contorting, touching, holding. A movement in which the artifice strains between shuddering and juddering. Machinic GIFs seem to frame an event which may or may not have taken place. Their motions appear to combine an endless neurotic repetition and a totally adrenal pumped and pumping tension, anticipating confrontation.

JBR: How do the heavily stylised triptych of screens in ‘The Searchers’ relate to the GIF-like loops created out of conventionally-shot street footage?

DP: I think of the three screens as something like the ‘unconscious’ of these nervous gestures. I’m interested in how video compositing can conjure up impossible or interior spaces, perhaps in a way similar to painting. Perhaps these semi-abstract images can somehow evoke how bodies are shot through with subterranean currents—the strange world of exchange and desire that lies under the surface of reality or physical experience. Of course abstractions don't really ‘inhabit’ bodies and you can’t depict metaphysics, but Paul Klee had this idea about an aesthetic ‘interworld’, that painting could somehow reveal invisible aspects of reality through poetic distortion. Digital video and especially 3D graphics tend to be the opposite of painting—highly regimented and sat within a very preset Euclidean space. I guess I’ve been trying to wrestle with how these programs can be misused to produce interesting images—how images of figures can be abstracted by them but retain some of their twitchy aliveness.

JBR: This raises a question about the difference between the control of your media and the situation of total control in contemporary cinematic image making.

DP: Under the new regimes of video making, the software often feels like it controls you. Early analogue video art was a sensuous space of flows and currents, and artists like the Vasulkas were able to build their own video cameras and mixers to allow them to create whole new images—in effect new ways of seeing. Today that kind of utopian or avant-garde idea that video can make surprising new orders of images is dead—it’s almost impossible for artists to open up a complex program like Cinema 4D and make it do something else. Those softwares were produced through huge capital investment funding hundreds of developers. But I’m still interested in engaging with digital and 3D video, trying to wrestle with it to try and get it to do something interesting—I guess because the way that it pictures the world says something about the world at the moment—and somehow it feels that one needs to work in relation to the heightened state of commodification and abstraction these programs represent. So I try and misuse the software or do things by hand as much as possible, and rather than programming and rendering I manipulate things in real time.

JBR: So in some way the collective and divided labour that goes into producing the latest cinematic commodities also has a doubled effect: firstly technique is revealed as the opposite of some kind of freedom, and at the same time this has an effect both on how the cinematic object is treated and how it appears. To be represented objects have to be surrounded by the new 3D capture technology, and at the same time it laminates the images in a reflected glossiness that bespeaks both the technology and the disappearance of the labour that has gone into creating it.

DP: I’m definitely interested in the images produced by the newest image technologies—especially as they go beyond lens-based capture. One of the screens in the triptych uses volumetric capturing— basically 3D scanning for moving image. The ‘camera’ perspective we experience as the viewer is non-existent, and as we travel into these virtual, impossible perspectives it creates the effect of these hollowed out, corroded bodies. This connects to a recurring motif of ‘hollowing out’ that appears in the video and sculpture I’ve been making recently. And I have a recurring obsession with the hollowing out of reality caused by the new regime of commodities whose production has become cut to the bone, so emptied of their material integrity that they’re almost just symbols of themselves. So in my show ‘The Dark Pool’ (Hollybush Gardens, 2014) I made sculptural assemblages with Ikea tables and shelves, which when you cut them open are hollow and papery. Or in ‘Time Crystals’ (Pumphouse Gallery, 2017) I worked with clothes made in the image of the past from Primark and H&M that are so low-grade that they can barely stand washing. We are increasingly surrounded by objects, all of which have—through contemporary processes of hyper-rationalisation and production—been slowly emptied of material quality. Yet they have the resemblance of luxury or historical goods. This is a real kind of spectral reality we inhabit.

I wonder to myself about how the unconscious might haunt us in these days when commodities have become hollow. Might it be like Benjamin’s notion of the optical unconscious, in which through the photographic still the everyday is brought into a new focus, not in order to see what is behind the veil of semblance, but to see—and reclaim for art—the veiling in a newly-won clarity.

DP: Yes, I see these new technologies as similar, but am interested in how they don't just change impact perception but also movement. The veiled moving figures in ‘The Searchers' are a strange byproduct of digital video compositing. I was looking to produce highly abstract linear depictions of bodies reduced to fleshy lines, similar to those in the show and I discovered that the best way to create these abstract images was to cover the face and hands of performers when you film them to hide the obvious silhouettes of hands and faces. But asking performers to do this inadvertently produced a very peculiar movement—the strange veiled choreography that you see in the show. I found this footage of the covered performers (which was supposed to be a stepping stone to a more digitally mediated image, and never actually seen) really suggestive— the dancers seem to be seeking out different temporary forms and they have a curious classical or religious quality or sometimes evoke a contemporary state of emergency. Or they just look like absurd ghosts.

JBR: In the last hundred years, when people have talked about ghosts the one thing they don’t want to think about is how children consider ghosts, as figures covered in a white sheet, in a stupid tangible way. Ghosts—as traumatic memories—have become more serious and less playful. Ghosts mean dwelling on the unfinished business of the past, or apprehending some shard of history left unredeemed that now revisits us. Not only has no one been allowed to be a child with regard to ghosts, but also ghosts are not for materialists either. All the white sheets are banished. One of the things about Marx when he talks about phantoms—or at least phantasmagorias—is much closer to thinking about, well, pieces of linen and how you clothe someone, and what happens with a coat worked up out of once living, now dead labour that seems more animate than the human who wears it.

DP: Yes, I’ve been very interested in Marx’s phantasmagorias. I reprinted Keston Sutherland’s brilliant essay on how Marx uses the term ‘Gallerte’ or ‘gelatine’ to describe abstract labour for a recent show. Sutherland highlights a vitalism in Marx’s metaphysics that I’m very drawn to. For the last few years I’ve been working primarily with dancers and physical performers and trying to somehow make work about the weird fleshy world of objects and how they’re shot through with frozen labour. I love how he describes the ‘wooden brain’ of the table as commodity and how he describes it ‘dancing’—I always wanted to make an animatronic dancing table.

JBR: There is also a sort of joyfulness about that. The phantasmagoria isn’t just scary but childish. Of course you are haunted by commodities, of course they are terrifying, of course they are worked up out of the suffering and collective labour of a billion bodies working both in concert and yet alienated from each other. People’s worked up death is made into value, and they all have unfinished business. But commodities are also funny and they bumble around; you find them in your house and play with them.

DP: Well my last body of work was all about dancing and how fashion commodities are bound up with joy and memory, but this show has come out much bleaker. It’s about how bodies are searching out something else in a time of crisis. It’s ended up reflecting a sense of lack and longing and general feeling of anxiety in the air. That said I am always drawn to images that are quite bright, colourful and ‘pop’ and maybe a bit banal—everyday moments of dead time and secret gestures.

JBR: Yes, but they are not so banal. In dealing with tangible everyday things we are close to time and motion studies, but not just in terms of the stupid questions they ask of how people work efficiently. Rather this raises questions of what sort of material should be used so that something slips or doesn’t slip—or how things move with each other or against each other—what we end up doing with our bodies or what we end up putting on our bodies. Your view into this is very sympathetic: much art dealing in cut-up bodies appears more violent, whereas the ruins of your abstractions in the stylised triptych seem almost caring.

DP: Well I’m glad you say that. Although this show is quite dark I also have a bit of a problem with a strain of nihilist melancholy that pervades a lot of art at the moment. It gives off a sense of being subsumed by capitalism and modern technology and seeing no way out. I hope my work always has a certain tension or energy that points to another possible world. But I’m not interested in making academic statements with the work about theory or politics. I want it to gesture in a much more intuitive, rhythmic, formal way like music. I had always made music and a few years back started to realise that I needed to make video with the same sense of formal freedom. The big change in my practice was to move from making images using cinematic language to working with simultaneous registers of images on multiple screens that produce rhythmic or affective structures and can propose without text or language.

JBR: The presentation of these works relies on an intervention into the time of the video. If there is a haunting here its power appears in the doubled domain of repetition, which points both backwards towards a past that must be compulsively revisited, and forwards in convulsive anticipatory energy. The presentation of the show troubles cinematic time, in which not only is linear time replaced by cycles, but also new types of simultaneity within the cinematic reality can be established between loops of different velocities.

DP: Film theorists talk about the way ‘post-cinematic’ contemporary blockbusters are made from images knitted together out of a mixture of live action, green-screen work, and 3D animation. I’ve been thinking how my recent work tries to explode that—keep each element separate but simultaneous. So I use ‘live’ images, green-screened compositing and CGI across a show but never brought together into a naturalised image—sort of like a Brechtian approach to post-cinema. The show is somehow an exploded frame of a contemporary film with each layer somehow indicating different levels of lived abstractions, each abstraction peeling back the surface further.

JBR: This raises crucial questions of order, and the notion that abstraction is something that ‘comes after’ reality, or is applied to reality, rather than being primary to its production.

DP: Yes good point. I think that’s why I’m interested in multiple screens visible simultaneously. The linear time of conventional editing is always about unveiling whereas in the show everything is available at the same time on the same level to some extent. This kind of multi-screen, multi-layered approach to me is an attempt at contemporary ‘realism’ in our times of high abstraction. That said it’s strange to me that so many artworks and games using CGI these days end up echoing a kind of ‘naturalist’ realist pictorialism from the early 19th Century—because that’s what is given in the software engines and in the gaming-post-cinema complex they’re trying to reference. Everything is perfectly in perspective and figures and landscapes are designed to be at least pseudo ‘realistic’. I guess that’s why you hear people talking about the digital sublime or see art that explores the Romanticism of these ‘gaming’ images.

JBR: But the effort to make a naturalistic picture is—as it was in the 19th century—already not the same as realism. Realism should never just mean realistic representation, but instead the incursion of reality into the work. For the realists of the mid-19th century that meant a preoccupation with motivations and material forces. But today it is even more clear that any type of naturalism in the work can only serve to mask similar preoccupations, allowing work to screen itself off from reality.

DP: In terms of an anti-naturalism I’m also interested in the pictorial space of medieval painting that breaks the laws of perspective or post-war painting that hovered between figuration and abstraction. I recently returned to Francis Bacon who I was the first artist I was into when I was a teenage goth and who I’d written off as an adolescent obsession. But revisiting Bacon I realised that my work is highly influenced by him, and reflects the same desire to capture human energy in a concentrated, abstracted way. I want to use ‘cold’ digital abstraction to create a heightened sense of the physical but not in the same way as motion capture which always seems to smooth off and denature movement. So the graph-like image in the centre of the triptych (Les Fantômes) in this show twitches with the physicality of a human body in a very subtle but palpable way. It looks like CGI but isn’t and has this concentrated human life force rippling through it.

If in this space and time of loops of the exploded unstill still, we find ourselves again stuck in this shuddering and juddering, I can’t help but ask what its gesture really is. How does the past it holds gesture towards the future? And what does this mean for our reality and interventions into it.

JBR: The green-screen video is very cold. The ruined 3D version is very tender.

DP: That's funny you say that. People always associate ‘dirty’ or ‘poor’ images with warmth and find my green-screen images very cold. But in the green-screened video these bodies are performing a very tender dance—searching out each other, trying to connect, but also trying to become objects, or having to constantly reconfigure themselves and never settling.

JBR: And yet with this you have a certain conceit built into the drapes you use: one that is in a totally reflective drape, and one in a drape that is slightly too close to the colour of the greenscreen background. Even within these thin props there seems to be something like a psychological description or diagnosis. And as much as there is an attempt to conjoin two bodies in a mutual darkness, each seems thrown back by its own especially modern stigma. The two figures seem to portray the incompatibility of the two poles established by veiled forms of the world of commodities: one is hidden by a veil that only reflects back to the viewer, disappearing behind what can only be the viewer’s own narcissism and their gratification in themselves, which they have mistaken for interest in an object or a person, while the other clumsily shows itself at the very moment that it might want to seem camouflaged against a background that is already designed to disappear. It forces you to recognise the object or person that seems to want to become inconspicuous. And stashed in that incompatibility of how we find ourselves cloaked or clothed is a certain unhappiness. This is not a happy show. Or at least it is a gesturally unsettled and unsettling one.

DP: I was consciously thinking of the theories of gesture that emerged during the crisis years of the early 20th century. The impact of the economic and political on bodies. And I wanted the work to reflect this sense of crisis. But a lot of the melancholy in the show is personal. It's been a hard year. But to be honest I’m not that aligned to those who feel that the current moment is the worst of all possible times. There’s a left/liberal hysteria about the current moment (perhaps the same hysteria that is fuelling the rise of right-wing populist ideas) that somehow nothing could be worse than now, that everything is simply terrible. But I feel that this moment is a moment of contestation, which is tough but at least means having arguments about the way the world should be, which seems better than the strange technocratic slumber of the past 25 years. Austerity has been horrifying and I realise that I’ve been relatively shielded from its effects, but the sight of the post-political elites being ejected from the stage of history is hopeful to me, and people seem to forget that the feeling of the rise of the right has been also met with a much broader audience for the left or more left-wing ideas than have been previously allowed to impact public discussion. That said, I do think we’re experiencing the dog-end of a long-term economic decline and this sense of emptying out is producing phantasms and horrors and creating a sense of palpable dread. I started to feel that the images I was making for ‘The Searchers’ engaged with this.

David Panos (b. 1971 in Athens, Greece) lives and works in London, UK. A selection of solo and group exhibitions include Pumphouse Gallery, Wandsworth, London, 2017 (solo); Sculpture on Screen. The Very Impress of the Object, Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal [Kirschner & Panos], 2017; Nemocentric, Charim Galerie, Vienna, 2016; Atlas [De Las Ruinas] De Europa, Centro Centro, Madrid, 2016; The Dark Pool, Albert Baronian, Brussels, (solo), 2015; The Dark Pool, Galeria Marta Cervera, Madrid, 2015; Whose Subject Am I?, Kunstverein Fur Die Rheinlande Und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2015; The Dark Pool, Hollybush Gardens, London, (solo), 2014; A Machine Needs Instructions as a Garden Needs Discipline, MARCO Vigo, 2014; Ultimate Substance, B3 Biennale des bewegten Blides, Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, CentrePasquArt, Biel, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; Ultimate Substance, Extra City, Antwerp, (Kirschner & Panos solo), 2013; The Magic of the State, Lisson Gallery, London, 2013; HELL AS, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Seventh Link: Summary and Rating

The game manual featured some fairly modest hand-drawn art.

The Seventh Link

Canada

Oblique Triad (developer and publisher)

Released 1989 for Tandy Color Computer 3

Date Started: 16 December 2018

Date Ended: 16 March 2019

Total Hours: 22

Difficulty: Medium-Hard (3.5/5)

Final Rating: (to come later)

Ranking at Time of Posting: (to come later)

Summary:

Inspired graphically and thematically by the Ultima series, The Seventh Link is probably the most extensive and full-featured RPG for the TRS-80 Color Computer. A single starting character ultimately enlists a group of allies of different races and classes on a quest to save their planet from a black hole at its core, about to break its containment. Solving the quest will take the party through dozens of towns across multiple planets and through multiple large, multi-leveled dungeons. Although the game gets off to a slow, grindy start, character development is rewarding and the tactical combat system (drawn from Ultima III) is most advanced seen on this platform. The problem is that the game’s content is not up to its size, and not enough interesting stuff happens while exploring the enormous world.

****

I never like giving up on games, and I particularly don’t like when I know the author is reading (I’m frankly not sure it’s ever happened before). But in several months of trying, I simply haven’t been able to make any decent progress in The Seventh Link. That doesn’t necessarily mean I don’t like it. If I was a Tandy Color Computer 3 owner, I’m sure I’d prize the game and play to the very end. The problem is that as a blogger, I have to be able to justify my playing time with material. If I spend four hours in a dungeon and all I can say is I killed a bunch of enemies (showing the same combat screens I’ve shown before) and gathered some gold, it’s hard to countenance that time.

In some ways, The Seventh Link is the quintessential 1980s RPG. It offers a framing story with more detail than appears in the game itself, sticks the player in a large world that the player has to map if he’s to make any progress, and features a lot of combat. In mechanics, it’s as good as any of the early Wizardries or Ultimas.

Unfortunately, Link was the last game I encountered before leaving the 1980s, and I’d just spent a decade mapping featureless dungeon corridors. It’s not its fault that it’s last; that’s just the way it happened. And by the time I got to Link, I just couldn’t do it anymore. I couldn’t–I can’t–play a game that’s just a few dozen 20 x 20 dungeon levels full of combats. The Bard’s Tale and its derivatives drained that battery.

I never figured out anything to do with the pillars.

This is the 90s, and gamers are demanding more interesting content in their game worlds. We want NPCs, special encounters, puzzles, and other features in those dungeons, at regular intervals. We’ve decimated forests in our consumption of graph paper; we’re ready for automaps. Ones that don’t require us to find a spell first.

Despite investing a fair number of hours into the game, I really didn’t accomplish much. I explored the surface of Elira, visited each of its towns to assemble a party, and mapped 4 of 13 levels of one dungeon. There were at least 9 more dungeon entrances on Elira alone, some of which would have taken me to teleporters to three other planets and their own towns and dungeons. I would have found a final party member, a female ranger named Starwind, on the planet Dulfin. Others dungeons would have led me to power packs and the places where I needed to install them to save the planet. I still don’t know where I was to find the other spells. From hints in an old disk magazine, I learned that the maximum character level is 25 (my main character reached 8) and that one of the planets has a store where you can buy potions that increase attributes, serving in the role of Ambrosia from Ultima III.

One of the few lines from an NPC. Alas, I will probably never explore Selenia.

My GIMLET is naturally based on an incomplete picture of the game:

4 points for the game world. The sci-fi origin story is fairly original, and well-told in epistolatory fashion, although it fails to explain a number of aspects of the world (e.g., why are there settlements on other planets). While the player’s role is somewhat clear, it’s less clear where he came from, how he got started on this path, and whether he understands his role.

3 points for character creation and development. The selection of races and classes is familiar but not entirely derivative. There’s nothing special about character creation or the development and leveling process, but they’re reasonably rewarding. I don’t know if the level cap would have caused any issues or if you finish the game well before reaching it.

3 points for NPC interaction. The game has a better system than it uses. You learn a few things from NPCs, but there are hardly any NPCs that say anything to you. Expanding that number would have resulted in a richer, more engaging world. I do like the Ultima IV approach to assembling your party by finding members in the towns.

2 points for encounters and foes. The monsters are mostly derivative of other games (though I like the explanations for their names here: the ship that populated the planet had Tolkien fans on it), and I didn’t really experience other types of encounters.

4 points for magic and combat. The tactical combat screen is about as good as Ultima III, but with fewer spells.

On Level 3 of the dungeon, I met an enemy called “Floating Stars.”

3 points for equipment. You can get melee weapons, missile weapons, armor, and adventuring equipment like torches and keys. Various sites hint at more advanced items like rods and gems of seeing. The selection of stuff is a little paltry in the traditional Ultima style.

5 points for the economy. It lacks a certain complexity, but money is certainly valuable. You almost never have enough keys, for one thing. Healing, torches, equipment, and leveling up consume gold fast, and it sounds like the shop on Dulfan would have served as an endless money sink for any extra you could accumulate.

2 points for a main quest with no side-quests or quest options.

4 points for graphics, sound, and interface. Almost all of that is for the interface. It adopts the Ultima standard of one key per action, which ought to have been mandatory as far as I’m concerned. Graphics are functional but sound sparse.

I never quite got used to the perspective. That lava square is only one square in front of me.

2 points for gameplay. It gets a bit for nonlinearity and a bit more for the moderate-to-challenging difficulty. But it’s not very replayable and it’s way, way, way, way too big and too long.

That gives is a final score of 32, which is hardly awful for the era. It’s actually the highest score that I’ve given to the platform. The only things that stop me from finishing it are the number of hours it will take and the number of other games on my list.

The Georgetown, Ontario-based Oblique Triad was a mail-order developer and publisher, co-founded by Jeff Noyle and Dave Triggerson. The name referred to the decorative bars on the top of a Color Computer. Mr. Noyle used to host a page (available now only on the Internet Archive) with links to their games, which included a pair of graphical adventures called Caladuril: Flame of Light (1987) and Caladuril 2: Weatherstone’s End (1988); a strategy game called Overlord (1990); an arcade game called Those Darn Marbles! (1990); and a sound recording and editing package called Studio Works.

Caladuril, the company’s first game, is a decent-looking graphical adventure.

With the Color Computer in serious decline by 1990, Oblique Triad shifted its focus to specializing in sound programming, and both Noyle and Triggerson have associated credits on Wizardry VI: Bane of the Cosmic Forge (1990) and Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant (1992). I haven’t been able to trace Triggerson from there, but Noyle got a job at Microsoft in 1995 working on Direct3D, DirectX, and DirectDraw and remains (at least according to his LinkedIn profile) there today. He also has a voice credit for a Skyrim mod called Enderal: The Shards of Order (2016).

Mr. Noyle was kind enough to not only comment on one of my entries, but to take the time to create overworld maps to speed things along. I’m sorry that it wasn’t quite enough, but every game that I abandon stands a chance of coming back when circumstances are different, and I’ll consider trying this one again when I feel like I’m making better progress through the 1990s.

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/the-seventh-link-summary-and-rating/

0 notes

Text

Passive income vs. passion income

Shares 167

When I was a younger man back before I founded Get Rich Slowly in 2006 I was intrigued by the idea of creating passive income. While passive income isnt exactly a get rich quick scheme (and boy was I intrigued boy those back then!), theres certainly some overlap. Both passive income and get rich quick schemes appeal to lazy people like my younger self, people looking for ways to make money for nothing.

What Is Passive Income?

Passive income, as the term implies, is money you earn on a regular basis with little or no effort required to maintain the cash flow after the income stream has begun.

Common examples of passive income include rental properties, royalties from books (and other published work), and profitable businesses that you own but in which you have little (or no) active involvement.

My interest in passive income started early in life. When I was a boy, my father was drawn to the promise of easy money. (See? This is another example of how we inherit our money blueprints from our parents.) Dad was a serial entrepreneur, as Ive mentioned before, but he was also drawn to multi-level marketing schemes.

Multi-level marketing schemes lure victims participants with the dream of big bucks for minimal effort. Sure, you have to set up your own operation by recruiting customers and a stable of salespeople, but once you do so the story goes you can sit back and relax as the money pours in!

Like my father, I too was drawn to these schemes when I was younger. My first job out of college, for instance, was a multi-level marketing scheme disguised as an insurance company. On a daily basis, the job entailed going door to door trying to sell hospitalization insurance (that was essentially worthless), but the folks who really made money did so because they recruited salespeople who worked under them. The top managers made plenty of passive income because of the pyramid nature of the program.

That said, passive income is not inherently slimy. In fact, its a terrific concept worth your attention.

Note: My favorite legit book about passive income is The Incredible Secret Money Machine by Don Lancaster. (Heres my review.) My dad bought a copy of this book when it came out in 1978, and I read it several times as a kid. (I still have Dads old copy signed by Mr. Lancaster himself!) If youre at all interested in legitimate sources of passive income, you should read the updated version of this book, which is available for free at the authors website.

The Power of Passive Income

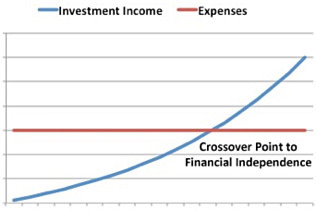

The truth is that if you can create multiple streams of income that operate without effort on your part, these streams can be terrific supplements to your regular job. Actually, the crossover point, an integral part of Financial Independence theory derived from the classic book Your Money or Your Life, is built around passive income:

The Crossover Point provides us with our final definition of Financial Independence. At the Crossover Point, where monthly investment income exceeds your monthly expenses, you will be financially independent in the traditional sense of that term. You will have passive income from a source other than a job.

At the moment, I currently enjoy several small sources of passive income:

Each month, I receive between $30 and $50 from sales of Your Money: The Missing Manual, the book I published in 2010. (I earn about a buck per book.)Similarly, I get about $100 to $200 each month from sales of the Get Rich Slowly course. My share of each sale ranges from $8 to $40 depending on a variety of factors.Im earning a tiny bit of revenue from a variety of websites that Ive abandoned or neglected.Kim is paying me $500 per month to vest into ownership of the house.My top source of passive income comes from interest and dividends on my investment portfolio.

In the past, Ive also received passive income through other sources such as business loans. (I loaned money to my familys box factory, for example, so the company could purchase a piece of machinery. The interest on that loan was passive income.)

There are folks who are under the impression that Get Rich Slowly itself is a source of passive income. Hahaha. Nope. Not even close.

For one thing, theres nothing passive about running this site. Its a full-time job, especially if I want it to be good. Plus, while Get Rich Slowly is generating revenue right now, its operating at a loss and not a profit. (So, I guess you could say that GRS is a source of active expense rather than passive income. Ha.)

What Is Passion Income?

During my short summer break last week, I took a morning drive to visit some friends. Jillian and Adam from Montana Money Adventures were passing through Portland during their 10-week mini retirement. I spent a couple of hours eating breakfast with them and their five kids.

Jillian was amused at how she kept burning the pancakes. (This isnt my usual pancake batter. Im used to Krusteaz, she said. So am I.)

After breakfast, Adam took their troop for a hike. Jillian and I sat by the campfire and recorded a video that shell use sometime in the future at her website. We chatted about travel (or course) and blogging (of course) and early retirement (of course). But then Jillian steered the conversation in an interesting direction.

We were talking about how retirement isnt always what people expect it to be, whether they retire early or not. A lot of folks quit their jobs to find that theyre life is without purpose, that theyre bored.

Thats why I encourage my readers and clients to pursue passion income, Jillian said.

Passion income? Do you mean passive income? I asked.

No, Jillian said. I mean passion income. Passive income is great, and if you can find a way to get some, you should do it. But passion income is something completely different. Passion income is money you generate by simply doing what you love.

Thats interesting, I said.

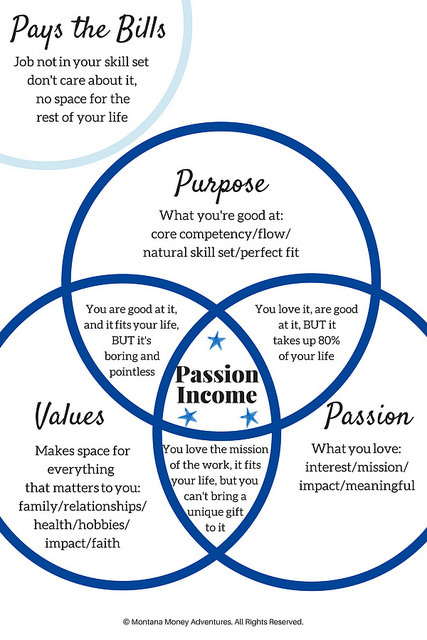

And passion income is different for everyone, Jillian said. For one person, their passion income might come from creating art. For another person, it might come from consulting. For another, it might involve doing carpentry on the weekend. For you, its Get Rich Slowly. The key, though, is that passion income combines what youre good at, what you like to do, and what matters to you.

The Power of Passion Income

I said good-bye to Jillian and her family, then headed home. But along the drive, I continued to think about the notion of passion income. Its an idea that Ive espoused for a while but never had a term for it. When I got back to the house, I dug through the archives at Montana Money Adventures to read more about the concept.

So far, Jillian has three articles about passion income:

Jillian says that passion income is derived from things that (a) are in your natural skill set or match your core competency, (b) you love the outcome and feel like youre making a difference, and (c) give space for other important things in your life.

Shes created the following Venn diagram to show what she means:

While neither Jillian nor I would argue that you should do what you love and the money will follow, I think we both agree that in an ideal world youd make money by doing something you enjoy. This might be difficult if youre currently in the middle of a specific career trajectory, but its much easier after youve retired.

After youve left the traditional workplace, you have the freedom to make choices more aligned with your self and your vision. Pursuing passion income whether its through art, a hobby, or work in your community can be an excellent way to take pressure off your retirement savings while also giving yourself a sense of purpose.

Thinking about it, thats really why I bought back Get Rich Slowly. My hope is that this blog will be a source of passion income (not passive income). And once I get the monetization thing figured out, I think it will be.

Combining Passive Income with Passion Income

The great thing, Jillian says, is that you can pursue both passive income and passion income.

That might mean doing something painting, writing a book that fits in both categories. Your work might fit in that passion income sweet spot, but then produce residual passive income in the future.

Or, that might mean pursuing multiple sources of income, some out of passion and some that are passive. (She points out that the happiest retirees average eight streams of income. Im not sure the source of that stat, but its interesting. And it makes sense. When you have diverse income sources, theres less risk to you if one of them dries up.)

Why even worry about passive income and passion income? Recently, I wrote about the struggle some people face to figure out how much to spend in retirement. While some people overspend, theres a sizable population that underspends. Theyre afraid to touch their nest egg.

Passion income alleviates the pain of spending. You get to work at something you love while also earning some money. And spending this money isnt painful, unlike spending out of your investment accounts.

Another benefit of passion income? If youre able to generate ongoing revenue with work that you love whether its part time or full time youre able to quit your career much sooner than you would on a traditional early retirement path. If you can earn $1000 per month by building picnic tables, for example, thats $300,000 less you need to save for retirement (given standard assumptions).

As I near fifty, Im still intrigued by the idea of passive income. I probably always will be. But the older I get, the more vocal I am that people should consider creating sources of passion income. Finding a way to earn even a little bit of money by doing something you love can not only be fun, but it can also help you reach retirement sooner or make your current retirement less stressful.

Shares 167

https://www.getrichslowly.org/passive-income-vs-passion-income/

0 notes

Text

Extended Play: How Final Fantasy XII’s gambit created one of the most distinct RPGs ever

From Playstation Blog USA

At the time of its original release more than 10 years ago, Final Fantasy XII received critical acclaim. Boasting incredible visuals that pushed the PS2 hardware to its limits, a unique battle system, and a strong cast embodying the classic thrills of a Final Fantasy story, it left a distinct impression on players.

Despite coming in the wake of a number of hugely successful entries in the series, its developers decided to take sizable risks with the franchise formula, while simultaneously paying homage to Final Fantasy traditions. It represented a bold, daring new vision for the series.

This is not just the story behind that gamble, but of the building of the game’s huge world and the rebuilding of the game itself both in the International Version, which tinkered with the gameplay, and the upcoming PS4 remaster, The Zodiac Age, which launches on 11th July. It’s a chronicle told by developers Hiroaki Kato and Takashi Katano, both of whom not only worked on the PS2 original, but have headed up development of the remaster as Producer and Game Director respectively.

youtube

XII’s extended dawn

Final Fantasy XII’s development lasted around six years. An unusual gestation length that – for a time – saw the game hold the Guinness Book of Records title for the longest development period for a video game production. Hiroaki Kato was project manager on Final Fantasy XII, and he was running the whole schedule for the development and production of the game.

Hiroaki Kato: “I remember one of the main things I did was trying to hurry up Mr Sakimoto, the composer of the original game, telling him ‘we need the music now, you need to get it quicker!’”

“Working on a game for such a long time was a difficult thing to do. When we look back at it today, a few reasons come to mind as to why it lasted this long. One of the things about the Final Fantasy series as a whole is that we try new things every single episode: new worlds, new characters, new game systems… Developing all of this from scratch always takes a certain amount of time.

“However, on FFXII specifically we were trying something that had never been done before in the Final Fantasy franchise: we wanted to transition from the kind of old traditional JRPG format that we were used to – shifting from field exploration to battle with separate systems – into what’s basically a modern open world game with a seamless transition from exploration to battle.

“We put a lot of our efforts into transitioning to a seamless automatic battle setup and how to make that fun for players. It took us long time to work this out. In fact, this concept was very set through the course of development but it is rather the volume of content in the game that exploded over time. Getting this in a state where it could be played and all fit together took a lot more time than we thought it would.”

Programming the Gambit system

It is this seamless transition focus that would lead to the introduction of what is probably the most unique feature of Final Fantasy XII: the Gambit system, a customisable battle system that very closely resembles programming code.

Thanks to the Gambit system, players can set up a list of commands for each character which they will perform automatically under the specific conditions they apply to. Setting up these commands and prioritising them with inventiveness is key to defeating many of the game’s encounters.

Hiroaki Kato: “Again, our concept for Final Fantasy XII’s battles was that it must ‘progress seamlessly in real time’. We feared that if we added just the real-time aspect to the command based battle system that other Final Fantasy titles had been following, controlling everything might be too fast-paced and difficult, so to solve this problem we adopted the Gambit system.

“In fact, Final Fantasy IV’s battle system already had a Gambit-like mechanic that controlled the monster’s AI behind the scenes, so we developed this into a different direction to make the Gambit System for Final Fantasy XII.”

“There’s a great feeling of triumph when you defeat a formidable enemy through a fine-tuned setting of your Gambits.” – Hiroaki Kato

Takashi Katano was the lead programmer at the time, and joins Kato-san again on the Final Fantasy XII remaster.

Takashi Katano: “From the very early stages of the project, we all knew the gambit system was going to be difficult to create, but we really wanted to go for that idea so we pushed on.

“I remember Mr Hiroyuki Ito, the main battle designer, saying – and the whole development staff, too – that it was really hard to gauge whether or not what we were doing was going to work nicely or not until the very end. We had this idea and this vision of what we wanted to achieve, of what we thought would make a good game, but when it was only part done it was really difficult to see.

“It’s only when we got quite close to the end of developing the battle system that it all came together and that we saw that yes, this is the vision we had in mind. It’s not something you’ll know from the start.”

Returning to Ivalice

Another particularity of Final Fantasy XII was its setting, Ivalice. The world, its colorful inhabitants and its detailed and seemingly infinite lore didn’t solely belong to XII, but were originally created for Final Fantasy Tactics…

Hiroaki Kato – “Ivalice is a world where the environment and cultures completely change depending on the location and the era, and between Final Fantasy Tactics and Final Fantasy XII, the nature of the world itself and the stories told have changed completely.