#i was considering blur to be an english major because. obvious reasons

Text

not me wanting to make bee an education major for a college au and then I reread my first blurb fic and there's literally a line in there abt how he should stay away from a career in education .

#WHOOPS#ok on my defense . i got nothing akdhdljflf#i was so focused on bee being good with kids & potentially gaining the patience and ethic to be a mentor if hes just given a chance#that it slipped my mind that i once thought he wouldnt be able to handle it bc hes scatterbrained & not the best at managing himself#its ok. its ok this is what character arcs are for#they didnt give bee any meaningful character arcs in the show that means i have to pick up the slack#except im not obligated to make any content of it and im too busy to rlly do any of that atm aksjdlfj#anyway. college au#i was considering blur to be an english major because. obvious reasons#actually maybe hes studying to be a reporter#or an editor#and then bee i had some trouble bc like. hes definitely the kind of guy to be directionless and probably would switch majors at the start#and im. these guys are not in the military bc theyre in college so i cant just copy paste stuff from the show#(thats why blur is not in intel. hes not in the military this time and his life is probably more peaceful bc of it)#and i was like. hey im going to be an education major maybe ........#bee would be a fun teacher but he needs to become more. structured? like time management and being more firm & focused#which hes definitely not good at atm. but again this is where he can develop his character#hes already sociable & good with kids & quick witted. good at problem solving & thinking on his feet#so yeah. just needs to get better at the ''boring'' stuff#ive had convos where others said he would be a gym teacher bc hes not smart enough to be a general studies teacher but. listen#i dont think bee is not smart enough hes just not traditionally booksmart or smth like that#but i believe in him he can do it 🥺#he just might need help from a study partner... like you know who#that's right. bulkhead.#also blur i guess but whatever#🐝 could you repeat the last part? 🟦

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I-I did it... I...I'm free! I'm free!"

i made a yt thumbnail thingy for fuyuki's second mv! i tried to cel shade to give it a more animated look.

more about fuyuki here.

also another infodump below!!

Songs and MVs

Fuyuki's T1 song will be called "Mirage". I imagine it having primarily having a green color palette and mainly taking place at his school. It has a light-hearted vibe (akin to Magic or TIHTBILWY). Everyone else except for Miori will have blurred faces. It will have plenty of lighting effects (lens flare, bokeh, chromatic aberration)

His T2 one will be titled "UMA". It will have a darker and purplish color scheme. It will mainly take place inside his house, specifically his bedroom (which also doubles as his mindscape). It will have a similar vibe to Double or Weakness. Everyone else except for Miori will be represented by chairs.

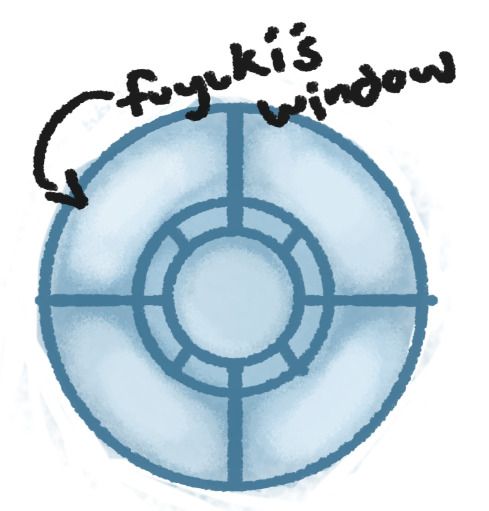

All of his mv will have this window:

His door art will also have this window

--------------------------------------------------------

Family and Friends

Miori was his closest friend and they have been together since childhood. Miori had a large influence in Fuyuki's life and a majority of his interests were actually because of her. She was the only person Fuyuki considered as a true friend, but he doesn't think so anymore.

He also has another friend, Seiichi. Fuyuki seems to be uncomfortable (or perhaps annoyed) around him, although Fuyuki claims otherwise.

His father is distant to him as he almost always away from home due to work. Fuyuki claims that he doesn't miss his father as he doesn't really have that much memories with him.

His mother is much more closer to him. Fuyuki loves her very much however it seems that Fuyuki tries to distance himself from her at times.

--------------------------------------------------------

About Fuyuki

Fuyuki has been noted to be easy to work with and seems to be incapable of expressing anger, only mild disappointment.

He is extremely bad at taking care of himself and has a habit of pushing himself to the limit. Has fallen ill several times because of this.

Good with the subjects math and English. He says he dislikes them though.

He also dislikes being given the position of leader during school projects.

Fuyuki is fond of the shima enaga and wants to see them in person one day. He is also interested in sharks and insects (one of the reasons he likes gardening)

Fuyuki likes oversized clothing.

--------------------------------------------------------

Miscellaneous

I have changed his birthday from June 18 to July 24 to correspond correctly with his birth flower.

His hair was supposed to evoke the image of a sheep. I think I failed though haha. I was originally planning to give him a light colored hair just to make it more obvious, but then he'd look like another oc of mine so yeah

Miori was originally supposed to be another prisoner paired with Fuyuki (she was going to be 012). But having more than one prisoner oc was too much work for me at that time, so i gave up and just made her Fuyuki's victim. Although I am currently working on another milgram oc.

That's all for now, thank you for reading all the way here!

I give you fuyuki's drawing of jackalope as a gift!

#milgram#milgram oc#ocgram#oc: fuyuki asagiri#oc#original character#evegram#my stuff#digital art#green's gallery

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soul

Breaking news, everyone: Pixar made another slapper.

I’m gonna get it out of the way first, but the only (and yes, only. Not like someone trying to say “only” even though they have many more nitpicks that they just don’t want to talk about) problem I had at all was that the super high realism of the settings of Earth kind of made the more cartoony faces of the people look a little more off. But, it’s kinda like the same thing people were talking about with that cat in Toy Story 4. It looks super real, which is impressive, but I feel like it was almost too real compared to the faces. Obviously it was too real compared to the supernatural settings because that was intentional, but yeah. It’s not even a big problem, it’s just the only one I can think of. I do think the realistic renderings of hair, light, water, etc at least work with cartoony stuff, but apart from that it looked almost like it could’ve been a photograph, with no exaggeration in the buildings or anything else.

I mean, I love the faces, so I definitely wish they went the extra mile showing extra personality and character in the buildings, as faces do with characters. Considering the faces matter like a bazillion times more, I still think they knocked it out of the park on the visuals. People with more investment and knowledge into the topic already said that the faces of any of the people of color felt cartoony and unique while also being true to life and respectful (My family recently stumbled onto some old animations from the 30s and lemme tell ya... We’ve come a long way), but seriously the characters that sold me on the visuals were the Picasso-esque beings who may or may not be the Gods of the universe maybe?

Spoiler boundary of course. It’s definitely worth a watch.

And that’s honestly what made the realistic world so much better. When the accountant guy went into the real world to set the count right, it was one of the most fun I’ve had just watching something. The sheer contrast between him and the world was so much fun, and it even solidified that those beings weren’t even acting in a different dimension or anything. They’re literally just beings that exist, meaning that all the other parts with the unborn souls and such are just as real as Earth. Or, even better, they’re the ones who can just casually rip a hole in dimensions. As far as depictions of Gods go, if they are even Gods at all, I think they’re one of the best I’ve ever seen. They feel like they could actually be how Gods actually exist, since all the commonalities of Gods involve supernatural power, which would suggest they’re supernatural themselves. I mean, I have a story with Gods in it too and they’re basically just that although admittedly a lot less imaginative.

With those guys being my favorite design, second place definitely goes to the lost souls, although obviously for more subjective reasons. 1) They’re purple, 2) They have one eye, 3) That eye is yellow which I always think is the best compliment to purple, 4) Tentacles, 5) Creepy in a kid’s movie. Franky, I would’ve made them a lot creepier, but even then they’re super creepy, if not visually then in their behavior. They’d just be kind of sad if they were just mumbling around, but since the first introduction to them starts charging at the main characters like a deranged monster. Considering how weird everything in that dimension is, finding something that isn’t nearly as innocent as everything else instantly invokes fear, since you have no idea what that thing can and wants to do to you. Sort of similar, I would’ve also made the “In the Zone” moments a bit more crazy and colorful, like when Joe fell through the void between the road to the Great Beyond and the You-seminar (is that how it’s spelled?), but these “I would do it differently”s might just be a fault of my design ideas or just subjective interests. I would’ve watched 2 hours of pure, nonsensical abstract worlds like the You-seminar with no explanation to how they work.

I definitely have a relief with the story, mostly entirely revolving around 22′s character. I was kind of worried she’d be too childish to really enjoy, but I feel like she was done really well. All the major historical figures’ remarks on how hopeless she were both funny and also really tied into her character “flaw” at the end as she was a lost soul. It might not be the most unique character archetype of all time, but it definitely makes sense, with all the people bringing her down implanting in her mind that she was an anomaly, and after a while was just sort of following it. Plus, she seemed genuinely interested in Joe’s weirdness, instead of being super mindlessly irreverent. And her being able to expand Joe’s understanding about his own world, like with the barber and his student, brings her up as more than a whiny, bratty child in the scope of the story. She didn’t JUST learn.

Even though I kind of expected it from the get-go, I’m also relieved that the movie didn’t shy away as much with the dark elements of death. It was kind of suggested that this wasn’t going to be a perfectly casual romp through a magical afterlife like Inside Out was with the mind because of the unborn souls unabashedly saying “Hell” in the TRAILER of the movie. I feel like that alone made the story super interesting, because it shows they’re actually going to be a bit more serious with things instead of just simplifying the unknowable complexities of the before & afterlife. Even with the dead souls going into the Great Beyond, it was a mix of being weirdly peaceful for some and super scary for others. My family thought it was peaceful for the most part, but my mom specifically though it was terrifying, and even though it’s a lot more peaceful than almost all other depictions of death, I can’t blame her. The souls were just kinda accepting it, like they’d been brainwashed or something, but still acknowledged that they were dead and were going into the afterlife. Plus, Joe, being the main character who we are supposed to sort of reflect in a way, was super freaked out by it, so that could easily suggest it’s to be afraid of and the other people are the weird ones.

I think the true message of the story being so strange was better too, because it would’ve been so boring if it fell into a super basic message we’ve heard millions of times. I feel like it has a similar sentiment to the basic messages, but is at least a more interesting way of saying it, if it is even like that in the first place, because it’s also somewhat vague in a good way. I think my brother/mother misinterpreted and simplified things a bit too much, where they thought it was sort of like a happier way of saying “accept your lot in life and don’t change it.” I could probably go on a full other rant about why I think this is wrong, but part of it is I don’t really know how they came to this conclusion in the first place, considering with that scene with that guy who threw the computers off his desk as his lost soul was cured (I guess you could call it that?), who obviously realized he wasn’t okay with his lot in life and was destined to change it. I think they sort of misinterpreted “the spark” and other things it as a 100% for-real, this-is-how-the-real-world-works sort of way, and not as much as a fictional way of saying things. Not necessarily symbolic, but I guess symbolic also? It has some of the same weird logical problems as the Cutie Marks from My Little Pony, except they’re obviously better since Cutie Marks determine your life down to your very job some of the time, while “sparks” are more vague and seemingly up to you. They’re more like when an unborn soul realizes there’s something on Earth they want to figure out, not necessarily their hobbies or jobs. For example, they kind of cited the barber character as the one who supported their point, but I think he does the complete opposite. He wanted to be a vet, but he ended up being a barber. But, they sort of assumed his “spark” was to be a barber, and that his personal interests didn’t matter because the “spark” forced him into a less favorable job. But, in reality, I feel like his “spark” is more his interest in love for the people around him, which is why he decided to get a more practical job to support his daughter (wife? one of the two) when he really needed to. Plus, he still enjoys being a barber because his devotion to love lets him connect to people as he cuts their hair. After all, he seems to be succeeding in his goal, since Joe was just like “Hey, let’s go see this guy he’s the exact guy we need!” People who don’t show love and interest for others don’t make that kind of impression in people’s minds. I feel like if we knew each story of everyone’s life down to the last detail we could fully determine what the mechanics of the world and its people are meant to say from a fictional context, but with such a limited selection I don’t think you can say something so sure. Sure, every choice in a movie is made specifically for a purpose, but I feel like if a movie tries to hard to be like “Oh but don’t worry here’s an exception” a million times it gets bogged down by its own attempt to make the message as obvious as possible.

Anyway...

There are also a lot of neat little details I loved, like how even though they did this for basically no other point in the movie, they made sure to include people from all around the world in that mess of dead souls, firmly sort of putting in the idea that the entire globe is in a sense one single entity that leads to the same place. They could’ve so easily just made everyone speak English for that throwaway scene, but I feel like including people from all around the world was very beneficial. Even the EXTRA little things, like the path to the Great Beyond looking like the neck portion of a guitar with the metal bits that separate the notes, or the facial features of the Gods blurring when they turned their heads in the other direction.

But yeah, who would’ve guessed Pixar made another good movie, right? Even then, Soul’s in the upper echelon of Pixar films. I really hope they (and Disney) realize they can go bonkers with a movie and still benefit/survive from it, since they’re so damn rich and inherently profitable. I think AAA animated movies like this that are the perfect amount of artsy are few and far between, and we need more of them. If anything, I hope they get more artsy, but I guess I’ll still never say no to a fun fantastical romp either. Basically, Pixar has looped me into watching any and everything they produce because it’s never “bad” I think. In the grand scheme of quality, even their worst work (Cars 2) is still not “terrible,” per se, even if it feels like it exists more as a cash grab than a genuine tale.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can’t live with them, can’t live without them

Yes hello time to over-analyze the omakes again even though they’re mainly meant to be jokes.

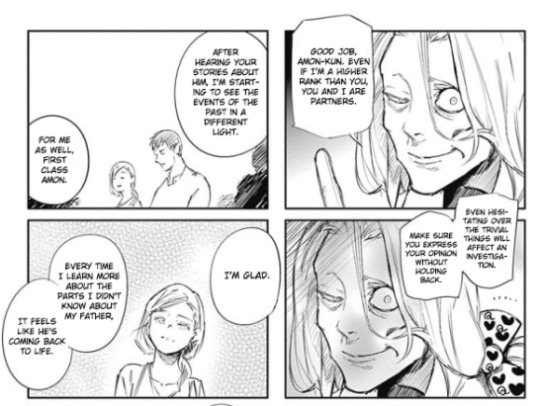

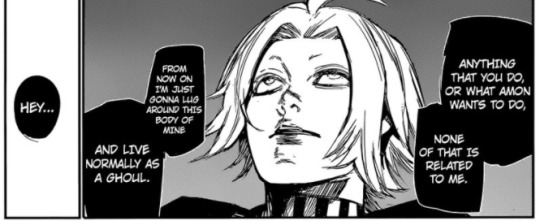

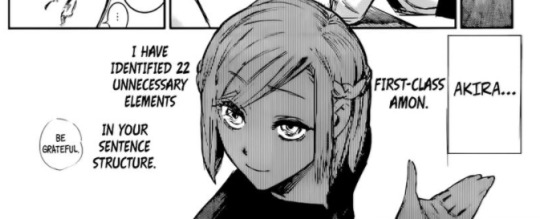

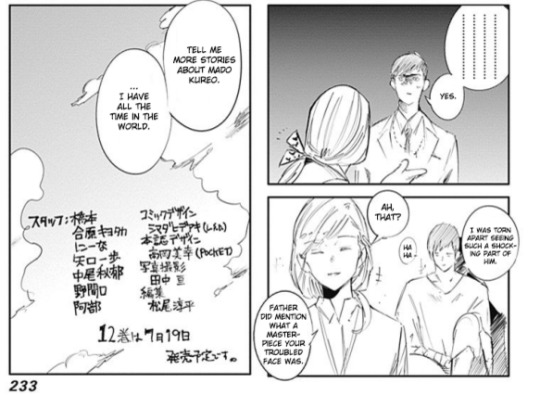

The omakes give us a glimpse into what Amon and Akira, and Seidou are doing separately without one another. As expected they’re both stuck in the past in a way, with Akira continuing to pore over old stories of her father even though everything in her character arc has suggested the way to move forward is in fact to let go of her father, and Seidou much less willingly being haunted by nightmares of his past and blurred memories sifting into his dreams as well. Something he is clearly not able to sort out for himself on his own without support.

The mixing of memories and dreams is clearly some kind of symptom of post traumatic stress disorder, but putting that aside for the second the fact that he sees Kanou and Houji in roughly the same light also means Takizawa could have unresolved feelings about what Houji’s betrayal meant to him.

The issue isn’t really the morality of whether or not Seidou was justified in killing Houji in that moment, as it’s already said and done, but the fact that Seidou’s own feelings about that aren’t ackonwledged, that they are shut up and only come back to haunt him in dreams is relevant.

It’s both a transgression and a trauma, that while yes Seidou acknowledges that he did do this and it was wrong which is almost a step above the other characters ignoring entirely their hands in building the wrongness of the world, he still chooses at this moment to simply to survive the trauma, to live simply teetering between life and death rather than even think about about trying to move past it.

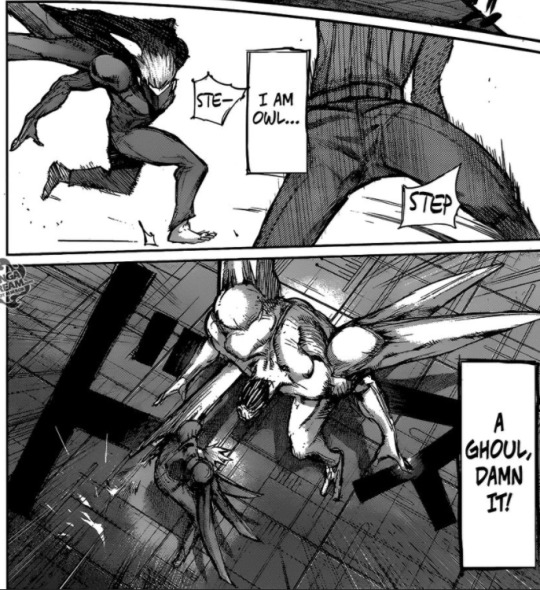

Ever since Houji severed his last hope, Seidou Takizawa has referred to himself exclusively as owl, or even avoided being called by his own name Seidou. In a way he’s let Houji’s rejection of his attempt to take over the CCG, his attempt to reclaim his old life, as an overwriting of his entire identity. A hope, no matter how misguided it is, is still some form of hope. Now in Seidou’s own mind, there’s no hope at all for ever being Seidou Takizawa again, Owl is a label he’ll wear for the rest of his life.

Seidou says he’s going to live, while at the same time calling himself dead. It’s an obvious contradiction and one he won’t be able to sustain himself on for long if his talk with Kaneki is anything to go by. It’s his same inferiority complex again, Seidou is either at the top of the world or the absolute bottom with no in between. He’s either a human who has the chance of returning to the investigators, or a ghoul with no hope in hell. Even though he’s correct right now in defining himself as a ghoul, and as one whose killed and done things he can’t take back right now, he’s still not seeing all of himself. The manga has been clear before, all half ghouls are part ghoul and part human in equal measure nad both parts of their being are valid and important.

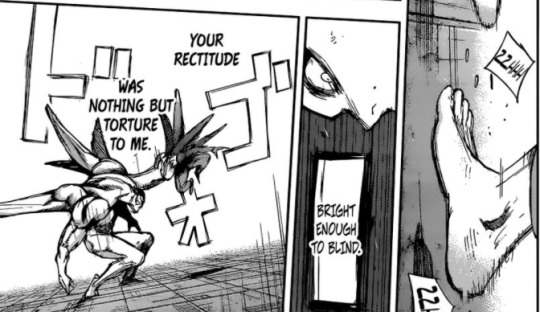

Seidou has a great ability to look at himself, but it’s not perfect. He has problems with looking at himself full, and evaluating himself fairly, perhaps because he’s always used to looking inside with little to no outsider perspective. This same applies to the others around him, while he’s capable of figuring them out and also figuring out the reality of the situations he also tends to fall into black and white idealizations too. Something which in the past, Amon has played along to rather than discouraged, but Seidou is still the one who initiates it. He sees things in terms of heroes and villains still, even if he looks at himself as the villain or perhaps one step above it.

He also, clearly designates Amon as the hero in comparison to him. While at the same time recognizing that for all of his talk, Amon’s words are just that words. he’s still unable to control his ghoul powers, and has lost not once but twice to Takizawa. This is once again, an unstable paradox of belief held by Takizawa. That Amon is both a hero an untouchable person who he could never measure up to, but also that Amon is pathetic and just as bad as he is.

In english terms this is called ‘binary opposition’ two opposing beliefs that seem as opposites and completely unable to coexist, yet at the same time find some uneasy balance within each other. The other sources of binary opposition are pretty easy to determine in Tokyo Ghoul, human and ghoul, and the uneasy tension that exists between them on a societal level but also the individual conflcits between both sides that half ghouls like Seidou and Amon face.

Rather than attempting a balance, the two of them have decided to live on opposite ends. Seidou considers himself a ghoul, and Amon a human, and this inability to see both sides is what prevents them from further growth.

While Amon and Akira turned their back on Seidou way too easily, perhaps in part motivated by the fact that Seidou represents an uncomfortable reality that neither of them fully want to face, it was Seidou himself who ran away first as soon as Amon reentered the picture. He had no problem of course, sitting next to Akira’s bedside every day before Amon suddenly became a factor again.

It’s Seidou who left first, making the classical wrong decision to try to live for their sake from a distance rather than enjoying their happiness up close. For making the assumption that Akira and Amon would not want him to be a part of their happiness.

Speaking of them.

A personal aside for a moment, I know I talk about Amon a lot. It’s not anything personal against Amon. I’m literally just trying to figure out what his character flaws are and where that next direction in his arc is going. It’s an attempt to understand the story.

Also, I wrote way more about Seidou this post, and I will admit my own bias Seidou is my favorite of the trio by a longshot. However, I hope my own ability to be critical of Seidou will show that my following criticisms aren’t a matter of personal preference but my honest evaluation of where I think characters are right now.

Seidou also makes this mistaken assumption too when he leaves. That this is the kind of world he can continue to live normally in, even when Furuta is in power. Seidou however has chosen to cling to his misery, his incitement of trauma, to just accept what he’s become and live on as a ghoul.

Which is the exact opposite of Amon and Akira’s own choice which is to cling onto past happiness. Just to preface this, what exactly is it that Amon and Akira have in common, what are the two most major things that lead them to meet? That they are ghoul investigators, and that they both had a strong personal connection to Mado who was a father figure to them both. This again isn’t me just trying to be reductive to frame my argument, it’s literally the moment they were introduced, in front of Mado’s grave. Their last character beat together in Tokyo Ghoul, in front of Mado’s grave. It’s something that hangs in the background of their two characters from introduction all throughout.

Of course the circumstances under which two characters meet does not define the entirety of their relationship, it is something that can be overcome. At the moment though, do either of the two characters show an interest in overcoming it?

The way Amon and Akira met was because of the connection they shared, as both investigators who were attached to Mado. This is the way they acknowledge each other now.

There’s a temptation for the two of them to act as if nothing has changed, to simply pick off where they have left off. One possibly suggested and encouraged by Touka who herself waiting for three years wanted nothing more than to simply continue where she once was regardless of the time spent waiting. To act as if it were nothing, that nothing progressed.

The two of them rather than trying to move forward with themselves, still focus on that which originally united them. That is their identities both of them as investigators, and the connection they both shared to Mado. Which is why all we see them doing in the omake, is musing about their past with Mado.

Akira says in the omake, the reason she tells stories about her father is because it feels like bringing him back to life. I think Ui clearly demonstrates that the point is not to attempt to bring your loved ones past back to life in some form, the proper thing to do is move on and let them go.

As Seidou chooses to dwell in his own trauma and misery believing that is all there is to his life, both Amon and Akira cling to past nostalgia. Believing that their time with each other in the bureau, the time they spent with Kureo Mado are the best times they are ever going to have in their lives. In a way this clinging to the past is something that implicitly prevents them from moving forward onto better things.

It’s also a bit more destructive, as Seidou admitted and Akira says indirectly, both of them believe they can simply step out of the conflict that is soon enveloping the entire world. Akira and Amon do not have all the time in the world. Especially if Akira truly loves and wants to live the rest of her life with somebody who is half ghoul. The same way that Seidou cannot simply keep living normally on as a ghoul.

They’re both showing they don’t really care about the world around them, even when it presses on them and begs them to care.

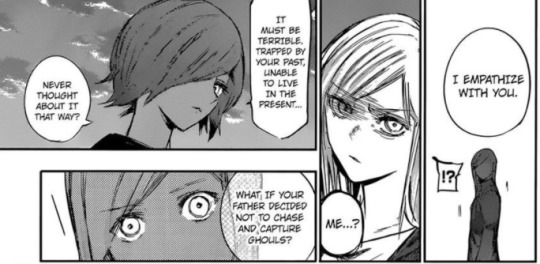

For Akira she too, has an impossible belief which she cannot reconcile. That of her father, because one thing I think the majority of the anaylsis that her talk with Touka misses is that she acknowledges this:

She knew that her father was taking lives. (Stole) is being used as the unspoken assumption in what she’s saying, the intention behind her words that Akira keeps to herself. It’s the same way that Arima referred to the taking of ghoul lives, “Stealing them”. That implies something inherently wrong with the act itself. On some level, Akira must have known what her father was doing was wrong. Especially considering how defensive she gets in the next moment without even much prompting from Touka. Defensiveness = Repression.

Therefore there are two conflicting images that Akira has of her father that she too cannot reconcile, that he was a murderer and also a caring father. What trips her up though is when it’s suggested that he didn’t have to be that way.

All of the things inflicted on Akira, were not done because of the way the world was, because of obligation, but rather by choice. Mado chose to pursue revenge against her passed on mother, and not to just try to live on simply with his daughter. He chose to not move on. That’s what rattles Akira, that a choice exists within this. It’s why her next moment what she is talking about her father, but rather her own element of choice.

The idea that rather than ghouls taking her father from her, but rather that she is a person in control of her own life an responsible for her own misery is terrifying to her. Akira can’t reconcile her motivations on her own, because her father gave her some her entire life, pressuring her to be an investigator, to live as her mother. She’s lived her entire life believing she did not have a choice, so the fact that she does is scary to her.

It’s possibly why her default mechanism is to delay, delay and delay until somebody steps up to make the choice for her.

Ignore all the past aspects of ghoul vs human an morality, and focus on this. By pretending that they have an infinite amount of time, that they can simply sit around and muse on their past and catch up with one another Akira and Amon are choosing not to choose. Narratives are made up of choices and Amon and Akira are not making any choices at all.

As characters in a narrative this is always a bad thing, and not a state that they can sustain. Sooner or later something will force them to choose.

I think it lies in Seidou who is absent from the group and neither of them seem to want to acknowledge. Seidou who also, doesn’t want to choose and acts uninvolved in this conflict. However rather than hide himself away in happiness, he hides himself from happiness an faces the darkness on his own. Seidou who looks physically, one eyed,

white haired and a bit deranged, like the ugly side of Kureo Mado that both of them refuse to acknowledge.

Akira and Amon ignore conveniently that Amon is a ghoul now, and the two of them focus on their time spent together as a human. Seidou lives only as a ghoul, and he himself loses and gets confused the memories of his time as a human in his dreams.

These two situations are deliberately set up to contrast each other. Just like a trio, who all it seems they do when they get together is fight and yet when separated all they seem to be able to do is think of how much they miss each other.

#tg meta#meta#the terrible trio#Seidou Takizawa#Koutarou Amon#Akira Mado#tokyo ghoul theory#tokyo ghoul meta#analysis

203 notes

·

View notes

Note

write your name in fire on my skin DVD commentary!

:DD Thank you so much for asking!

(write your name in fire on my skin)

Roxanne’s palm connects with a sharp crack; Megamind’s head snaps to the side with the force of the blow, but before Roxanne can feel more than a fleeting sense of satisfaction (she finally managed to work her arms free during a kidnapping, finally managed to—almost—escape), a burst of pain flares across the inside of her wrist. Jesus, she didn’t slap him that hard, did she? She didn’t want to hurt him, not really, just shock him enough to give her a chance to get away.

Soulmate AUs are one of those things that, when they work for me, really work for me. And I’ve always liked the versions that involve the soulmate’s name appearing on the character’s skin; this seemed especially interesting for a Megamind/Roxanne story because of the way that names are clearly so important to Megamind (he chooses his own name in canon; he’s appalled at being called ‘bernaaard’; he addresses Roxanne as ‘Miss Ritchi’ during their professional interactions, etc.)

Having the bond be cued off of skin-to-skin contact seemed like the most interesting choice, too, since Megamind wears so much clothing—an indication, I figured, that he didn’t feel that he deserved the chance of finding a soulmate.

So I thought some more about the soulmate idea, and I was thinking ‘well, how would having soulmates be a thing affect human culture?’ and then I thought ‘oh, but what if it’s not human culture? what if it’s just Megamind’s?’

And I saw a golden opportunity for angsty misunderstanding.

So I knew that the skin contact had to be initiated by Roxanne (Megamind would never risk it; the disappointment if he touched her and the mark didn’t appear would be too much for him to handle, and, as previously stated, he thinks he doesn’t deserve the chance at finding a soulmate anyway). Like I said, Megamind wears a lot of clothing, so there’s not a lot of possibilities for skin contact.

And having the soulbond be catalyzed by a slap seemed like a delicious piece of irony.

But—no—the pain is—more of a burning sensation, heat licking over her skin, and she’s made a pained noise and pulled her wrist to her chest before it registers with her that Megamind has made the same sound, and is cradling his own wrist to his chest. Why—

She looks down at her hand—is she bleeding; did she scratch herself on his spikes or something, and sees—

“What.” she says flatly. “How is—Megamind, what did you do?”

There’s a mark on her wrist; not a scratch or a burn, but something that looks almost like a tattoo: fluid black lines of what appears to be a script of some kind. Roxanne can’t read it, but she does recognize the first mark in the series.

It’s the M-and-two-lightning-bolts insignia that Megamind uses to mark things as his.

Interestingly! I was still thinking about my M’ega language at this point, and still wanted to make the {M} symbol something like

So I headcanoned it for myself like this: Megamind has spent a lot of time on earth, and human culture has shaped his personality and his sense of himself. That’s why his name isn’t written M’ega-style on Roxanne’s wrist: he’s sort of intertwined the M’ega language with the english language into his own personal pidgin.

‘Syx’ still = {M} and it’s still what his parents called him—which is why it’s still such an important part of his identity, and why it’s the beginning mark in his name.

Your soulmate’s soulmark will be your true name: whatever you consider to be your true name. (for example, if you’re trans, your soulmate’s soulmark will never be your deadname; it will be the name you choose to identify yourself as)

Megamind stares at her, eyes too wide, white showing all around the green of his irises, cradling his own wrist protectively.

“That’s not possible,” he whispers. “It’s not—it’s not supposed to be—”

“What the hell is this doing on my wrist?!” Roxanne demands.

She tries wiping the mark away with her other hand (Megamind makes a soft, pained noise at that), and then scrubbing it vigorously on her skirt. This has absolutely no effect; the mark stays where it is.

“Ugh! What is this thing? Get it off of me!”

“Oh, god,” Megamind says, sounding as though he’s about to be sick. “Oh, god, no. Please, no.”

This, Megamind thinks, is the only thing that could be worse than Roxanne not being his soulmate: she is his soulmate but she doesn’t want to be.

Roxanne looks up at him at that, about to demand to know what’s wrong with him, and is hit full in the face by a cloud of knock-out spray.

She wakes up in her apartment, lying on her couch. Someone has stuck a throw-pillow underneath her head.

Megamind definitely had a minor panic attack over whether or not to put the pillow under her head. (as opposed to the major panic attack that he was still having about the soulmark itself)

The mark is still on her wrist.

The mark stays on her wrist. It stays when she scrubs at it with soap and water, when she attacks it with makeup remover, when she pours peroxide over it.

Nothing she does even manages to smudge the firm, flowing black lines and finally Roxanne, frustrated and exhausted, goes to bed.

The mark is still there in the morning. She stares at it for a full minute and a half and then, for lack of a better option, puts on a long-sleeved shirt and goes to work.

She will make Megamind explain this to her when he kidnaps her next, make him take it off of her, make him fix it.

Roxanne’s first instinct is to try to fix the problem herself. Her second instinct is that everything will be fine once she talks to Megamind again.

Roxanne wears a lot of long-sleeved shirts over the next two months.

As the days—and then the weeks—begin to go by, and Megamind still doesn’t show up,

Roxanne goes from merely annoyed, to downright furious, to increasingly alarmed.

He’s never gone this long without kidnapping her. She’s never gone this long without seeing him. She actually—she misses him, misses his ridiculous theatrics and his stupid evil laugh and the way his eyes light up when he talks about something exciting. She’s always said, ever since the beginning, that she just wanted her normal life back, but now—it’s like there’s a hole in the fabric of Roxanne’s reality, an emptiness that—it feels like loss, like—

Roxanne still wants her normal life back, but normal now means spikes and lasers and blue supervillains with smiles as bright as magnesium fire and she wants him back, wants him back right now, wants him—

She doesn’t know where he is; Wayne doesn’t know where he is (she asks).

Nobody knows where he is.

Magnesium fire is extremely bright! And fire/warmth as an indication of love is a theme throughout the story: that’s why there’s that flare of heat when the bond takes, and that’s why Roxanne compares Megamind to magnesium fire.

It’s midnight and Roxanne should be sleeping. Instead, she’s standing in front of the glass doors that lead out to her balcony, looking out into the dark, at the streetlights and the stars, rubbing her thumb absently over the mark on her wrist.

It’s been—hurting, lately, a sort of ache that started in her skin and has since spread into her bones, settling there like cold, like resignation, like the certainty that, somewhere, something awful is happening.

And here we have the first indication that the soulbond is also a psychic link! (I LOVE TELEPATHY) Notice that she talks about feeling cold.

She rubs her thumb back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, and then presses her hand to her chest, as though she’s trying to put pressure on a wound.

She goes looking for Megamind the next day.

(She thinks she might be feverish; it’s summer, the sun is shining, and Roxanne is in long-sleeves, and yet she feels cold, so cold.)

Emotional agony as actual physical pain is such a fascinating trope to me—pon farr and the version of beauty and the beast that I read when I was a child where the beast almost dies because he’s so unhappy and convinced that beauty doesn’t love him.

She has no very clear idea of where she should be looking for the Lair, but it’s by the water; she knows that much. Roxanne heads for the waterfront and begins wandering. The mark on her wrist aches like frostbite; she covers it with her other hand, clutching at it, shivering.

Another reference to feeling cold as an indication of her soulmate in trouble/an incomplete soulbond.

This way, she thinks, mind all blurred around the edges, and takes a turn down an alleyway seemingly at random. This way. She takes another turn. Here.

She finds herself at a brick wall but somehow the fact that this should pose an obstacle to her doesn’t manage to sink into her brain.

Roxanne walks into the wall before it occurs to her that she should stop, and then there isn’t any reason to stop, because she’s somehow walked through the wall and ended up, as if by magic, exactly where she wants to be.

Here, she thinks, he’s here.

She stumbles onwards through the darkened Lair.

She almost cries with relief when she sees him. He’s sitting in his chair, looking at a giant screen on which numbers are rapidly scrolling, one hand resting on the keyboard.

Roxanne catches herself against the doorframe, knees going a bit weak, and Megamind looks up and sees her.

“Oh,” he says, in a flat voice. “It’s you again.”

The tone of his voice—Megamind has never spoken to her like that. It’s not—

“I’m afraid I still don’t have it,” he says, already looking at the screen again. “Like I told you last time, though, I’m getting close.”

And even Roxanne, disoriented as she is, knows that something here is very wrong.

Still don’t have it? she thinks muzzily. Still don’t have what? Last time? What last time? When did we talk about this? The last time she remembers talking to Megamind at all is that kidnapping he cut short after the weird mark on Roxanne’s wrist appeared.

Roxanne crosses the room to stand beside his chair, leaning against it, one arm on the back.

“What’s with the screen?” she asks.

(Megamind will explain this to her; Megamind always explains things to her when she asks; show even the slightest interest in his evil plan and he starts monologuing.)

She looks down at him.

The sweater he has on, an orange-gray thing with ragged sleeves and half its buttons missing, is possibly the ugliest thing Roxanne has ever observed.

(the ugly orange sweater returns in Code: Safeword, actually!)

He’s wearing ordinary clothes; she’s never seen him in ordinary clothes before. He’s not wearing his cape or his spikes or his high collar, although he is wearing his gloves, fingers of one hand tapping at the keyboard now, the other hand lying like a dead thing on the arm of his chair.

That would be the hand with the soulmark on it. And that’s why he’s wearing gloves: he can’t bear to look at the mark.

God, he looks—he looks terrible: bruise-like shadows underneath his eyes and in the hollows under his cheekbones, and the way he’s holding himself, as if simply existing hurts him almost more than he can bear.

He looks like Roxanne feels.

She’s getting dizzy, standing like this, and she wants—

She climbs into his lap, turning herself sideways, her legs over the arm of the chair, one arm around his neck, the other hand on his chest.

“Oh,” Megamind says softly, “touching? That’s—that’s new.”

He puts his arms around her easily, though, one curling around her waist, the fingers of his other hand sliding into her hair as though they’ve done this a thousand times before.

It feels—she feels—

Roxanne feels safe, the terrible cold feeling in her bones finally easing just a little bit beneath the pressure of his hands. She almost gasps in relief with it, and yet—

And yet it is not contentment; she wants to—she wants him closer, closer even than this. She leans against him, pressing her face into his neck, skin to skin and shudders at the sensation and it is still not enough.

Having physical contact ease the pain of the incomplete bond seemed logical, since it’s catalyzed by skin contact.

The hand in her hair moves to hold the back of her neck and why, why is he wearing gloves?

Megamind is speaking; for several moments she’s too caught up in the sound of his voice to understand what he’s saying, but then—

“—chemical composition, just has to finish sequencing, and then I’ll be able to get rid of it for you,” he murmurs, hand in her hair again. “It’ll be gone; It’ll be gone soon, you don’t need to worry—”

Roxanne is just about to ask him what he’s talking about when she hears Minion say, in a shocked voice—

“Miss Ritchi?”

Megamind’s hand stills in her hair.

“You can see her, too?” he asks, sounding confused. “I thought I was—I thought it was another—she’s actually here?”

“Of course I’m here,” Roxanne says, hooking her fingers in the collar of his hideous shirt.

Megamind lets go of her like she’s made of fire and Roxanne’s vision goes gray and starts to tilt.

Like she’s made of fire: something that it hurts him to touch, something dangerous, and remember that fire = love is a big theme in this fic.

That, she thinks, her last thought as the dark rises up and blots everything out, that is probably not good.

She wakes up in Megamind’s arms again, to the sound of him and Minion arguing.

“—horrible, Sir, how can you even contemplate—it’s—that’s blasphemy; you can’t just break a soulbond—”

“—it’s a physiological reaction, Minion! There is a physiological cause and a physiological cure and—”

“—isn’t a disease! This is dangerous. You could die and—”

“—humans aren’t even meant to bond like this! It’s—look at her, it’s hurting—”

“—that’s because you’re being—”

“—she’ll be fine when I—”

“—she’ll be—? What about you?”

“—said she didn’t want—”

Roxanne makes a distressed sound, anger and terror and misery pouring into her body in a way that feels oddly—foreign. As though the emotions aren’t coming from her, but from somewhere outside of her.

The bond is closer to being completed, now, and they’re physically closer, too, so the telepathic/empathic connection is stronger.

She hears Megamind’s swift intake of breath, feels a sudden spike of that strange, outside-of-herself fear.

“What’s happening?” Roxanne asks weakly, sitting up to look around but staying as close to Megamind as she can.

They’re in a bedroom, she realizes, on a bed. Are they—is this Megamind’s bedroom?

“Nothing,” Megamind says, “nothing’s happening. Go back to sleep. I’m fixing it.”

Roxanne looks into his face.

“Fixing what?” she asks.

He swallows, eyes flickering closed and then opening again.

“The—the mark on your wrist,” he says. “It was. The result of—an unfortunate accident.”

Roxanne hears Minion make a sound of protest.

“An unfortunate accident,” Megamind repeats firmly. “It—the physical contact, when you slapped me, our skin—it allowed for a contamination, an infection, that’s why—”

“That is not—” Minion says.

“That is why,” Megamind continues loudly, “you’ve been feeling—ill—lately, because you are ill, but I’ve found the cure for it, so you don’t need to be worried—”

“That is an inaccurate representation of the facts, Sir, and you know it!” Minion cries.

Megamind trying to downplay his own emotional needs always hurts my heart. He calls her connection with him an infection and is as dismissive as possible about what it means to him.

“It’s not inaccurate! Humans aren’t supposed to have this! What the hell else do you call that but a contamination?”

“I feel cold,” Roxanne whispers. “I feel cold again.”

An indication from the bond that whatever it is Megamind has planned? Is a very bad idea.

Megamind wraps his arms around her and pulls her close and Roxanne moans. He feels—so warm.

“I can fix this,” Megamind says. “I’m going to fix this.”

Roxanne nuzzles his throat and feels a shock of pleasure run down her spine like lightning.

Oh, she thinks and does it again.

Again that ripple of pleasure and Megamind gasps this time, the way a man coming out of deep water gasps for breath.

Roxanne’s tongue goes out to taste his skin, licking up the length of his throat and Megamind moans and suddenly Roxanne’s fingers are on the buttons of his shirt, undoing them and shoving the material aside.

“Uh,” she hears Minion say, “I’m just gonna—yeah, I’m gonna go now.”

AHAHAHAHAHAHA OH GOD I LAUGHED WRITING THIS PART. See, I knew that I needed Minion in the room to talk to Megamind, so that we could get an idea of what’s going on with the soulbond. But I also knew that I wanted the bond to actually be fully completed between Megamind and Roxanne—and I couldn’t figure out how to get from one scene to the other. I tried a whole bunch of different things, but none of them worked. So finally I was like ‘okay, what if it just starts happening while Minion is there and it’s AWKWARD?’ and it really worked.

And part of Roxanne, a distant part, is appalled that she just started undressing Megamind in front of Minion and part of her is appalled that she’s pretty sure she would have continued to do so if Minion hadn’t taken it upon himself to leave, but most of her is focused on undoing the damn buttons.

“This is—” Megamind says weakly, “—this is really not what I meant by fixing—this is the opposite of—I have the cure now, the syringe, I can—” he kisses Roxanne, then tears his mouth away from hers. “I can take it now, I can—”

Note that he’s always going to be the one taking the dangerous ‘cure’, not her.

“Or,” Roxanne says, unbuckling the clasps of his gloves, “or you could not do that and kiss me again.”

She yanks off his gloves and sees—

—on his wrist—

—that’s her name.

That’s her name, Roxanne Ritchi, black letters written there in her handwriting, and she thinks of the M-and-lightning-bolts symbol on her own wrist, before the alien lettering—his name?

Is it his name, on her wrist?

And she thinks she almost—she almost understands what is happening to her, what is happening between them, what this is—

“Roxanne—“ Megamind says, and kisses her again and Roxanne’s mind is wiped clean of all thought.

She drags her fingers down his throat and he shudders in pleasure and she feels an echoing jolt of sensation go through her own body and this—this is where the unfamiliar emotions are coming from, isn’t it, a strange feedback loop between the two of them.

He pushes her down onto the bed and Roxanne can feel him, his thoughts and feelings humming in the back of her mind, but it’s not until later, when they’re pressed together, skin to skin, nothing between them, that she feels the connection break wide open and—

—then—

—he’s everywhere, above and around and inside of her, their thoughts running together like water, desire and pleasure and love, so much love that Roxanne’s mind cannot contain it.

I love you, she thinks as she cries out, as Megamind cries out with her, the whole world bursting into fire and light.

I love you.

Again the fire/light/love connection.

She wakes up alone.

She is alone in the bed, and when she reaches for Megamind’s presence, for that low hum of his thoughts in the back of her mind—

It’s not there. He’s not there.

She sits up in bed, looking down at her wrist, and—

The mark is gone.

Megamind’s name is gone.

Her wrist is empty.

“No,” she whispers. “No no no.”

She hears someone make a pained noise from the floor beside the bed and looks down swiftly.

Megamind is slumped bonelessly up against the wall, back in his clothes again.

Missing scene from Megamind’s point of view is: he wakes up first and is horrified at himself, decides to take the ‘cure’ immediately. He puts his clothes back on because he plans on leaving the room to inject himself—but he can’t quite do it.

He thinks he’s probably going to die doing this and he desperately wants Roxanne to be the last thing he sees before he dies.

So he sits next to the bed instead, and watches her sleep for a moment (god, she’s so beautiful and he hates himself so much) and then he injects himself.

There’s an empty syringe on the floor beside him.

“Oh,” he says in a flat voice. “I survived.”

Roxanne finds that she is shaking.

“Oh, well,” he says, sitting up an wincing. “I suppose Minion will be pleased about that, anyway.”

Megamind isn’t particularly pleased about it.

“Megamind,” Roxanne says, voice trembling, “what have you done?”

“I fixed it,” Megamind tells her, his voice devoid of any inflection whatsoever. “Bond’s gone. Check your wrist.”

Roxanne looks again at the bare skin of her wrist.

“Mine, too,” says Megamind.

He holds up his own hand, tugging up the sleeve of his shirt to show her.

It’s blank. Roxanne’s name has disappeared.

Oh god. Oh god.

“But,” Roxanne whispers, “but we just—how could you when we just—”

Megamind turns his face away from her, mouth in a flat line.

“Yes,” he says. “I—apologize. For—that. I should never have—I wasn’t thinking clearly—the. The bond, the impetus of the—” He makes a quick slashing gesture. “But of course that’s no excuse. Confusion is no—I shouldn’t have. I am very sorry, Miss Ritchi.”

Roxanne makes an involuntary sound of horror and covers her mouth with both hands.

He calls her Miss Ritchi and it hurts.

But I thought you loved me, she wants to say, and presses her palms harder to her lips to hold in the words.

The feedback loop. She’d thought—she’d thought that the love was coming from both of them, but—oh god—it had just been her.

Had his desire even been—the impetus of the bond—wasn’t thinking clearly—no, oh no, please no.

He didn’t love her. He didn’t even want her. She was never going to—she was never going to feel his thoughts again; she was going to be alone forever, inside her own mind, alone—

Roxanne seems to be a rather lonely person, in canon: we don’t see her with friends, or with family, and when she meets ‘Bernard’ she latches onto him fiercely and immediately. She’s also clearly fascinated by Megamind’s mind—the breathless way she says “wow” when she sees his idea cloud. I think she’d be very into the idea of sharing his thoughts, and having such an intimate connection ripped away like that without warning is very awful for her.

“Please,” Megamind says, standing, a look of distress on his face. “Oh, god, please don’t cry.”

Roxanne buries her face in her hands, trying to muffle the sobs.

“I’m sorry,” he says, “I’m so sorry, so very—I won’t ever touch you again, so you don’t need to worry about the bond coming—don’t need to worry about—I won’t ever—I’ll stay away from you, I swear; you won’t ever have to see me again, Roxanne—”

Megamind thinks she’s crying because she had sex with him, that she’s that upset about remembering it. Roxanne, of course, is crying because she thinks he doesn’t love her.

“Is that,” Roxanne manages to say, “supposed to make me feel better?”

“Of course it isn’t—enough,” he says, “it isn’t good enough. I don’t. I don’t know what you want me to do. I’ll do—whatever you want, whatever will make you feel—”

“You don’t—have to do anything,” Roxanne says, curling up into a ball, fingers tightening in her own hair, trying to hold in her sobbing. “You don’t—god, Megamind, you don’t owe me anything like—just don’t—please just don’t act like you expect me to be happy that you—don’t want me—” she grits her teeth to keep from wailing. “—when I just—when you know—”

“—wait,” Megamind says, “that I don’t—? I don’t under—I don’t understand. What are you—”

“You know how I feel about you!” Roxanne cries, slamming her hands down on the mattress and fixing him with a glare through the tears blurring her eyes. “You felt it! Stop pretending like you didn’t! I get that you don’t want me and that’s—” she drags her hand over her face “—fine! But don’t pretend—”

“That wasn’t you—” Megamind says, eyes wide. “That wasn’t you feeling that. That was all—you don’t—you told me you wanted the bond gone!”

“When the hell did I say that?” Roxanne demands, furious and still crying. “Was it during one of your hallucinations?”

“Those are beside the point!” Megamind says. “They happen when I don’t sleep at all for more than a week and—you did say it! You said it the day the mark appeared! You said, ‘ugh, what is this thing’ and you said ‘get it off of me’ and you tried to wipe it away and—”

“I didn’t know what it was!” Roxanne shouts. “You didn’t tell me what it was! How the hell was I supposed to—”

“You don’t even like me!” Megamind shouts back.

Roxanne’s mind goes white with fury. She swings her legs over the side of the bed and stands, not bothering to cover herself with the sheet, not bothering with anything but moving towards Megamind.

A look of alarm flashes over his face; he backs up a handful of steps, but then his back hits the wall. There’s nowhere for him to go and Roxanne is right in front of him, blocking him.

“Don’t like you?” she repeats, voice low and dangerous. “You fucking idiot.”

(*shivers* Roxanne is so beautiful when she’s angry.)

“You don’t,” Megamind tells her. “You can’t possibly.”

“Let me show you,” she says, and kisses him.

Fire licks across her wrist and Roxanne licks into Megamind’s mouth, feeling the bond flare to life inside of her head. She reaches for the connection and pours as much love as she can through it, directly into his mind.

The fire/love metaphor again!

Megamind makes a noise beneath her mouth and she feels the slow-dawning wonder in his thoughts, feels the moment that he starts to believe her, feels the joy that bursts inside of him, and then a pulse of love singing all along their connection. And it’s not an echo of her own feelings—it’s from him—he feels it; he feels it, too, and Roxanne lets him push her gently backwards towards the bed again.

Later, she wakes up to find Megamind leaning on one elbow next to her, tracing the lines of his name on her wrist. Roxanne takes his hand and presses a kiss to her own name on his wrist.

Megamind smiles like magnesium fire flaring to life and leans in to kiss her.

The ‘flaring to life’ line evokes both the magnesium fire and the catalyst of the bond, and it’s important that it flares ‘to life’—this moment is about a beginning, about living (happily ever after).

And we finally get to see Megamind smile.

#dvd commentary meme#write your name in fire on my skin#megamind#megamind/roxanne#still working gradually through the requests for the dvd commentary meme!#mycatisis

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Lost Vocabulary of Social Insurance

Social insurance programs are at the center of American politics. In fiscal terms, Medicare and the Social Security Administration’s programs for retirement, disability, worker’s compensation, and worker’s life insurance amount to roughly 41 percent of the federal budget. This fiscal centrality, however, does not rest on anything like a broader, public understanding of what makes social insurance social — and thus why such programs are so important in American political life. On the contrary, over the years our vocabulary of social insurance has become increasingly replaced with a vocabulary of welfare and redistribution, creating a fundamentally misleading impression about most of what the federal government does.

In the mid-1930s, when the retirement and survivors insurance programs had their legislative start, university-educated Americans had every reason to be clear about what distinguished social insurance from its commercial counterpart. Indeed, most undergraduate programs in the social sciences took up social insurance’s rationale and history. But note the data measuring the historical use of the expression in three of America’s most important daily newspapers. The changes recorded are startling. By the end of the 20th century, the category of social insurance had seemingly lost its place in the vocabulary of American politics.

This is particularly unsettling because of the enormous importance of social insurance programs in American history. The Great Depression, which wiped out the savings of most American families, caused multiple bank failures, and saw an unemployment rate of some 25 percent, prompted demands for substantially increased government protection against economic disaster. “Welfare” was the term used for programs that made poverty status the precondition for financial aid, and President Roosevelt acknowledged that immediate aid to poor families was required. But his case for increasing the footprint of American social policy was based on the principles of social insurance, not merely poor-relief narrowly construed.

By the 1970s, social insurance programs had become major components of the federal government, but also the targets of ideological and budgetary attack. Social Security retirement, Medicare, disability, and unemployment insurance were increasingly labeled as simply “entitlements,” and charged with contributing to out of control spending via unaffordable benefits. This allowed critics to advocate for a much smaller social policy commitment, urging a less costly “safety net” for the deserving among America’s poor citizens. The semantic bait-and-switch can be seen with Google’s Ngram viewer, which tracks word frequencies across the American English corpus.

Yet the principles and judgments incorporated in the concept of social insurance remain central to the major policy debates of our time, most dramatically in the debates over health care reform and the affordability of Social Security retirement benefits. They are relevant to the backlash against the Affordable Care Act and to the debate, rekindled recently, between the advocates of “Medicare for All” and advocates of Medicaid expansion as the next step toward universal health coverage. More generally, they are crucial to addressing the broader conservative critique of government’s role in American social policy.

So, What is Social about Social Insurance?

Social insurance, like commercial insurance, is about protection against financial risk. It is “insurance” in the sense that people contribute to a fund to protect themselves against unpredictable financial risks. These include outliving one’s savings in old age, the early death of a breadwinner, the onset of a disability that makes work difficult if not impossible, the high costs of acute illness, involuntary unemployment, and work-related injury. Yet unlike with commercial insurance, contributions are not prices in a market and thus do not depend on the contributor’s risk profile (unless commercial regulations say otherwise, in essence creating “social” insurance through the backdoor). Instead of a contract between an enrollee and an insurer, social insurance is a system of shared protection among the insured, most comparable to mutual insurance in the commercial realm, with contributions made in proportion to one’s market income. In social insurance, the “insurer”—whether a government agency or a corporate body with a joint labor-management board—is the agent of the contributing enrollees. And unlike commercial insurance, the social insurance “contract” mandates participation by law, since otherwise adverse selection would cause its unraveling.

Social insurance spreads the costs of coverage according to a different logic than that of commercial insurers. The same risk in commercial insurance carries the same premium price. The greater the risk, the higher the price of coverage. Social insurance, by contrast, operates on the premise that contributions are calculated according to one’s income and benefits according to one’s needs. But the central political feature of social insurance is that the contributors are also beneficiaries. This is not the case with social assistance programs with means-tested eligibility standards. As important as such programs are for those who experience poverty, taxpayers do not in general identify with welfare beneficiaries.

How much difference does it make that most contemporary reporting on social insurance programs, and much social science scholarship, ignores their conceptual underpinning and distinctive operational features? Should popular voices in American social policy be criticized for using proper names to describe programs without explaining their distinctiveness from means-tested welfare programs? I would not be writing this essay if I did not believe, as one of three co-authors, that the title of our 2014 book — Social Insurance: America’s Neglected Heritage and Contested Future — identified an important problem.

“Entitlement”-talk

Words make a difference to all thinking about public policy, but this is especially the case where conflicts are over fundamental values. Consider, for example, the common use of “safety net” as a collective description of programs as diverse as Medicare and Medicaid, old age Social Security, food stamps, disability insurance, and homeless shelters. This expression collapses the distinction between means-tested welfare and social insurance programs into a metaphor suggesting that recipients have to “fall” into poverty to warrant help. This is the opposite of social insurance, which represents a platform on which one can stand before economic risks arise. The term “safety net” is even more ambiguous, particularly when modified by terms like high or low, porous or tightly knit, threadbare or generous, or applied in situations when one’s financial resources are largely “spent.”

The use of public finance terms like “income transfers” further blurs the differences between cash benefits that one receives only after income and asset tests are applied and insurance payments that kick in without such tests. Then there is the term “entitlement,” which was meant to refer to the nondiscretionary nature of the spending, but now connotes an adolescent sense of entitlement among the beneficiaries. Neither term helps us understand the robust public approval of our major social insurance programs, and indeed, are often employed by opponents of social insurance in order to obfuscate an otherwise popular concept.

The negative connotation of “entitlements” is especially misleading. When one legitimately claims some social insurance benefit, the implication is that there is a corresponding duty to provide that benefit. That is the basis of the common sentiment among recipients of retirement income Social Security that they have earned their pensions. That widely shared sentiment largely explains the political fear that any substantial reduction in those benefits is a “third rail.” Few if any critics of the program criticize the appropriateness — or desirability — of OASI, the old age retirement and survivors insurance programs, on its own terms. Instead, they concentrate on claims that the programs are unaffordable. As a result, a large proportion of the public fears for their future despite the obvious political vulnerability of such critiques.

Understood as a technical budgetary category, entitlements in American fiscal policy are simply those programs whose benefits and beneficiaries cannot be adjusted without statutory changes. Administrations cannot simply reduce a program’s benefits or change its eligibility rules on their own. That entails constraints on administrative flexibility, reflecting the idea of stable governmental commitment to social insurance protections over long periods.

Using the entitlement category in two senses is confusing and in that respect harmful. What citizens believe about the appropriateness of a program is a distinct concept from the budgetary rules about changing its provisions. Both are important, but when was the last time you, the reader, saw this distinction explained when the entitlement term was used? Instead, “entitlement” is used like a four-letter word in diatribes about the supposedly troubled future of social insurance programs.

“Solvency”-talk

Still another source of linguistic confusion is what I will call solvency talk. When policy discussion turns to the fiscal projections of social insurance programs, critics and defenders alike turn to the trust fund. If the old-age retirement actuaries forecast a revenue projection of X in 25 years and the projected outlays of Y equal more than X, the “trust fund” is, according to this logic, in trouble. It will no longer have enough to meet its “bills” at that date. And if that shortfall were to continue, the necessary result would, in this framing, be insolvency, even though few policy experts seriously doubt the sustainability of programs like Social Security given fairly modest reforms, nor the political catastrophe of allowing the trust fund to run dry. In this sense, solvency talk is a lot like the threat of government shutdown created by the Federal debt ceiling — a crisis manufactured from the intransigence of elements on both sides of the aisle rather than anything fundamental.

Reflect for a moment about budget forecasts of Department of Defense outlays. Nobody writes about the military department going “broke” or becoming “insolvent” no matter how fast the growth in the budget. Indeed, no sensible analyst would make 20, 30, or 40-year forecasts for defense expenditures. Some analysts, in discussions of the future of Social Security make conditional forecasts long into the future. These are said to be useful exercises, reminding the public that commitments now have long-term effects. But the very preoccupation with solvency generates unnecessary anxiety. Since DOD does not have a “trust fund” budgetary categorization, its future outlays are presumed to be ones over which future governments have some control.

The same legal control is available to the Social Security Administration and the Congress. The confusion is even worse in programs that combined different funding mechanisms. For instance, funding for Part A of Medicare comes from the social health insurance trust fund (HI) while Part B is funded from general revenues and beneficiary premiums; it cannot go broke, but it can be reduced. That prompts solvency talk about Medicare’s future without clarification of how the program differs in two of its component parts.

The background of most solvency questions is the widely reported growth of the future retiree population. The Census Bureau projects that the over-65 population will soon make up 20 percent of the population. Such projections, unaccompanied by estimates of what increases in funding social insurance programs will require, prompt concern. Dire predictions of “insolvency” or cuts in retirement benefits get reported in the media without much scrutiny. As a public speaker, I face such questions regularly. I urge my questioners to dwell for a moment on how a growing proportion of senior citizens can be politically compatible with large reductions in future Social Security benefits. Put another way, how could the “sacred cow” of Social Security — in the language of its critics — face such a fate under conditions that, if anything, only cement its political sanctity?

There is another irony here that warrants discussion. The original use of trust fund language in social insurance had more to do with trust than with funds. President Roosevelt rightly felt in the 1930s that the contributory ethos of social insurance would come to be central to its secure political status. A population believing that each contributing worker had earned their social insurance benefit would not tolerate substantial budgetary cutbacks. The idea of a trust fund, then, was to emphasize the special status of a program whose benefits would be decades after a contributor’s payments. Its design is to enforce time-consistency, and its language is meant to highlight reliability. Yet sadly this language has since been turned upside down, bringing needless fear of “running out” of funds and thus uncertainty about the future. Roosevelt’s protective rhetoric backfired as the original understandings of social insurance weakened, even while the popularity of the programs remained substantial.

Social Insurance, Our Neglected Heritage

There are at least two plausible criticisms of this essay’s argument about the importance of relearning the appeal of social insurance principles. One is that the world has changed dramatically since the birth of social insurance in the late 19th century, let alone since the 1934-35 Committee on Economic Security provided a blueprint for expanding social insurance in American public life. The other is that changes in long-standing European social insurance programs show that major adjustments in the American programs are required as well.

The claim that the world has changed does not necessarily mean that the economic risks against which social insurance programs offer protection have been fundamentally altered. Consider every one of the risks noted in this essay — outliving one’s savings, involuntary unemployment, medical costs, and disability. Not one has disappeared, and social insurance programs for each have been implemented in wealthy democracies. I doubt, in other words, whether social insurance is in any conceptual trouble.

But that does not mean social insurance programs don’t need to adapt to contemporary circumstances. The spread of contract employment has been particularly challenging for European countries where social insurance is a function of trade unions and other sector-level organizations. It is equally obvious in the US that employer-provided health insurance puts a damper on labor market flexibility. Reduced employment in regular jobs with health coverage will demand the search for other sources of provision. These and other realities of our changing economy will only bring to the fore the central claim of this essay: Social insurance programs dominate American social policy but what that means for our politics is too little understood or explained. And that criticism extends not only to harried reporters but to a significant amount of the public policy community, as well.

Theodore (Ted) Marmor is a Niskanen Center adjunct fellow and Professor Emeritus at The Yale School of Management.

The post Our Lost Vocabulary of Social Insurance appeared first on Niskanen Center.

from nicholemhearn digest https://niskanencenter.org/blog/lost-vocabulary-of-social-insurance/

0 notes