#kazakh history

Text

one thing that's unfortunate when researching early 20th century kazakhstan is that you'll find one specific person, usually an etymologist, or an ethnographer, or a poet, or all of them, they revolutionize one part of kazakh society, so you wonder, I wonder what happened to them?

they almost all died before 60 due to either the purge or tuberculosis, which is very sobering at the least, and makes me want to crush stalins head like a watermelon

I urge you guys to research at least some of them, off the top of my head there's:

Ahmed Baitursynov

Alikhan Bukeikhanov

Mirjaqip Dulatuly(uli)

Shokan Ualikhanov

Baurzhan Momushuly

and tons of others, quite interesting, though expect most of the sources to be russian or kazakh

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Context missed from the screenshot: the soil in Qazaqstan varies greatly in quality, and the climate is similarly unpredictable. Qazaqs have adapted to this land by adopting seminomadic lifestyle, which Soviet russians denounced as "culturally backwards" and decided to force them into sedatary farms. They, of course, did not provide any scientific/agricultural/terraforming preparations and simply expected Qazaqs to provide cosmic harvests in a semi desert by a sheer power of faith in communism 😒)

Force nomadic cultures into a farm -> do not provide the water and food that cattle needs to survive -> the said nomads begin to starve and try to escape somewhere where they won't starve -> declare the people your policy forced into starvation "enemies of the state" and shoot them

🤬🤬🤬🤬🤬

[Book: Sarah Cameron - The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence and Making of Soviet Kazakhstan]

#history#kazakhstan#Aşarşılıq#Qazaqstandağı#famine#artificial famine#ussr#soviet history#communism#kazakh history#quasaqstan

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay so one of the symbols of modern Kazakhstan's independence is Altyn Adam - Golden Man*(as in person).

Altyn adam refers to an artefact that was found 1970 in Issyk kurgan(burial)*.

It looks like this(id in the end of the post and in alt):

It is actually quite interesting how the artefact was found.

In 1968 the town Issyk became a town and wanted to develop. However, they needed experts to first check that there are no historical sites, which is what they did. For all of 1969 they were carefully uncovering he kurgan, and in 1970 they finally opened it.

It was empty. The place had signs that it has been robbed several times before.

One archeologist, Bekmuhanbet Nurmuhanbetov*, decided to check some 30-40 meters away, and found a side-burial which was left untouched since 6-5th century BC.

They found so many artefacts that listing them all here would be quite difficult.

What I would like to mention though is who was buried here:

Gender is unknown*, but the age is around late teens(16-18)

The person that was buried here was most likely to be a child of some kind of tribe leader, because their burial is smaller than the main one.

About the tribe! The burial probably belonged to Saka tribes. Saka people might relate to Scythians(they are probably part of the same cultural group?)* *. Anyways this particular kurgan was made by Tigraxauda people. Their name derives from persian and means. Pointy hats........

The golden armor is probably more ritualistic(haven't seen it in direct text sorry) than anything because the golden pieces of armor are wood covered in golden leaf. The helmet is made from golden plates though.

There are actually some interesting thing that are present on the helmet. By that I mean the arrows, which are said to symbolise 4 parts of the world. There are also multiple animals* on it. As a whole the costume consists of 4000 golden pieces.

And finally, Why is it so important?

Well to answer this question, you should know USSR's relationship with history and how is was teached in Kazakhstan specifically: mainly, world history through the lense of revolution and how Kazakhstan just sorta became part of USSR after it was Russian Empire's colony*. Nothing before that as people that lived on this land.

Which led to a very hard situation after the independency was gained because well. The majority of people were Kazakhs, but a lot of culture and identity was lost. And part of it was history.

So an artefact this old brings a sense of legitimacy. It also doesn't hurt that it's pretty.

ID and notes under cut

[ID: Armor on a mannequin in a museum setting standing above camera. The mannequin is wearing long-sleeved jacket which is a mix of red fabric and triangular golden pieces. The same pattern is on its boots. The pants are made from a red fabric. It is wearing a very large conical headpiece almost as tall as its chest(40cm). It is very pointy. The headpiece has 4 golden arrows and some animal ornaments on it. The figure has a bow and and an arrow in its hands, and a sheath for sword and another weapon on its belt. It is also wearing a red cape just reaching its thighs. ]

* Actually there are several artefacts like this! Around 6 or so which were found in different regions at different time. All of them are called golden men, just the place that varies. This one is Issyk's Golden Man. Some of them are actually made from solid gold and not gold leaf which I find fascinating.

* Ok so kurgan is used interchangeably here with burial. And in a way kurgan is a burial. It is also in a way like a pyramid? There are things left for the dead so they can carry them to the afterlife, but the kurgan itself is built a bit in and above ground. The rooms are made from logs, and then covered with dirt to create mounds. I also heard that a herd of horses would run it over a bunch of times to set the earth.

*Full name Bekmuhanbet Nurmuhanbetov Nurmuhanbetovich. He eventually organized a museum for the kurgans he found. He died in 2016, at the age of 81, and for some reason he has "Bekem-aĝa"(aĝa means older brother, uncle just an older friendly male figure) as his pseudonym on his Wiki.

*Actually Saka seem to had been pretty great about equality. There is also a very cool story about their female chief Tomiris.

*Historical records about nomadic people come exclusively from settled ones. Because a lot of stuff they would probably write on(despite the claims about lack of writing system) would't have survived because you know. Nomads.

*Haven't mentioned it in the post but sometimes Saka people are called ancestors of Kazakh people and uhhhh. They are probably more related to modern Europeans than to us. They still had similar lifestyle and lived on this land though. And they were more mixed than anything because you know, race is bullshit.

* Oh also fun fact one of the animals is a tulpar which is a horse with wings. The same mythical animal is present on Kazakhstan's official coat of arms.

*should I keep making these notes? because I feel they might take away from the flow of the text, and some details are simply not that important or I cannot convey them properly. so. what do you think?

#the whole legitimacy thing is of course not just kazakhstan#every country out there is doing it tp build a cohesive narrative that people can unite around#kazakhstan#kazakh#kazakh culture#kazakhstan history#kazakhstan politics#kazakh history#Kazakhstan culture#ussr#history#asia#central asia#cw: mention of death#what warnings should I put?#ussr culture#ussr education

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

National Museum Astana ( Kazakhstan )

#travel#travelphotography#museum#astana#kazakhstan#musical instruments#gold#national museum#kazakh history#kazakh culture#silk road#central asia#nationalmuseumastana#visitastana#kazakhstantravel#visitkazakhstan#history#culture#photooftheday#pickoftheday#around the world

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Country flags now vs then Part 3

What countries do u want to see next? Tell me in the reply section or in the messages

#history#country flags#flags#geography#greece#mongolia#kazakhstan#ethiopia#mongol empire#kazakh history#mongol history#greek history#ethiopian history#my edit

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Manshuk Mametova, a machine gunner during the Second World War and the first Kazakh woman awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

She was only twenty one years old when she didn’t retreat from a strategic hill after German soldiers began to approach. She was wounded in the head and knocked out, but regained consciousness and continued to fire from three machine guns.

She killed more than 70 enemies in her final battle.

#kazakh culture#kazakh history#history#second world war#girl blog#womanhood#women power#girlblogging#girljournal

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Probing the manner in which Kazakhs attained noble status in the Russian empire, this article explores a neglected aspect of the country's social history. Recognizing that nobility is typically associated with landowning in a feudal order, we explore how this status also found application in the steppe. Based on diverse sources and comparison with other ethnic elites, we regard Kazakh ennoblement not only as a way of recognizing a traditional nomadic aristocracy, but also as a method of creating a new native elite beneficial to Russia's colonial project. We likewise propose that the distinctive character of nomads’ pastoral lifeways differentiated the Kazakh nobility from their Russian counterparts and prevented them from making full use of noble privileges. The article thus explores the nature of Russia's social order by interrogating its margins and contemplates both the possibilities and limits of social inclusion for Russia's ethnically and culturally diverse population.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

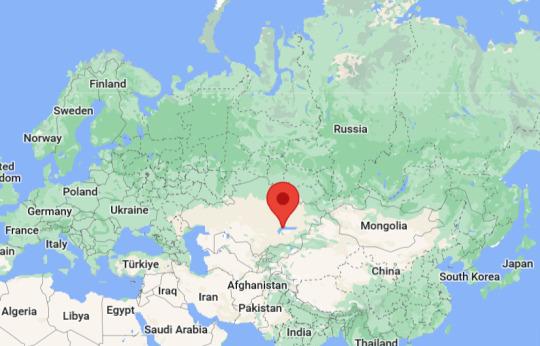

Where in the world: Balkash, Kazakhstan

Copper--it's used to make everything from coins to cookware, and in the case of Balkash, an entire city was built on it.

In 1928, a wealth of copper reserves were discovered on the site where the city now stands along the northern shore of Lake Balkash. By 1937, the settlement that had been set up to provide goods and shelter to workers in the area had become the city.

Over the next few decades, the mining and metallurgical operations in Balkash supplied much-needed copper to the USSR and the rest of the world. After Kazakhstan gained its independence in 1991, Balkash continued to be a major hub for copper.

Today, about 66,000 people live in Balkash, and copper's still a really big deal. They build monuments out of it--like this one that commemorated the 50th anniversary of the company formed to mine copper from the region.

Its rich warm colors are also echoed in the architecture like on the facade of this mosque.

Each year, the anniversary of the opening of the copper plant is celebrated as a holiday, and nearly everyone has at least one family member who works in the industry.

Since 1952, nearly 13 million copper cathodes have been shipped out of the city, and so many tons of raw copper have left Balkash bound for elsewhere that they've literally lost count of how much has been produced.

The next time you see a penny or flip an egg over in your copper-clad skillet, you just might be encountering a little piece of Balkash's history.

#balkash#kazakhstan#geography#history#travel#copper#metallurgy#ussr#soviet union#soviet history#kazakh history#balkash kazakhstan#kazakhstan history#smelting#building#city#mosque#monument#Balqash#scenic#cityscape

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Russian Revolution and the Alash Orda

It’s 1917 and Central Asia is adjusting to a Tsarless reality. To briefly recap, because a lot has already happened and it’s about to get even more complicated:

Russian settlers created the Tashkent Soviet in the city, Tashkent. It is purely Russian managed and was created in response to indigenous organizing.

Various indigenous peoples such as the Jadids, the Ulama, and even the Alash Orda spent all year organizing different organs of government, ending 1917 with the Kokand Autonomy. This is an independent state created in Kokand, a city that neighbors Tashkent, in response to the Tashkent Soviet.

The Bukharan Emir kicked out his Jadids and relied on conservative elements in his society to strengthen his hold on power before Russia returns.

The Khiva Khanate is dependent on a warlord that is planning a coup.

Up to this point, we’ve focused on an Uzbek/Tajik Jadid perspective. Today we’ll be switching focus to the Kazakh and Kyrgyz intellectuals in the Steppe and the creation of the Alash Orda government and the Autonomous Alash state.

Alash Origins

As we discussed in our interview with Dr. Adeeb Khalid, the Muslim world was going through severe soul searching in the 1900s as they tried to understand the rise of European empires and the crumbling foundation of, not just the Ottomans, but Islamic nations in general. This was true in the Kazakh Steppe as well, although for the Kazakh intellectuals, it wasn’t just a question of how does Islam survive, but how do we define Kazakhnessand how do we ensure it survives?

The Kazakh identity crisis was sparked by the land crisis. We’ve talked about this in some of our other episodes, but starting in 1890, Russian settlers streamed into the Kazakh lands, taking important arable land that the nomadic Kazakhs relied on to survive. The Russians performed several exhibitions and surveys in the region between 1890 and 1912 and the Kazakh land grew ever smaller and smaller. Of course, this came to a head in 1916 and by 1917 the Tsar was gone, Russia was in disarray, and the Kazakh peoples had an opportunity to create their own government and address land rights.

Yet, while there was a real threat from Russian incursion, the Kazakhs also took advantage of opportunities the Russian presence offered. Many Kazakhs learned Russian and went to school in Russian run schools as well as local Kazakh schools (as opposed to the madrasa education mandated in places such as Tashkent and Bukhara), they had a long history of trading and even working with Russians, and the Kazakhs were also familiar with the Tatars and even the indigenous people of the Siberian oblast that the Russians relied on to support their colonial administration. And in an odd way the land crisis brought the Kazakhs closer to their Kyrgyz and Bashkir neighbors because they were experiencing the same problem.

This connection with Siberia seems to have provided the Kazakh intellectuals the support they needed to survive Russian persecution and take their ideas and grow it into a full-fledged movement. In fact, there is a great article by Tomohiko Uyama which details how the Russia attempts to banish important Kazakh activities such as Akhmet Baitursynov and Mirjaqip Dulatov to the outskirts of the Steppe (and sometimes in Siberia itself) allowed them to make widespread connection with other activities as well as each other and only fanned the flames of their work.

Akhmet Baitursynov described this time in Kazakh society as being caught between “two fires”: the influence of Muslim culture and the influence of Russian and Western culture. Out of this tension came the Alash, modernizing intellectuals. But even the Kazakh intellectuals couldn’t decide what was the best way to save Kazakhness, so they split into two big-picture groups: the Western-centric modernizers who were the editors for the newspaper Qazaq and the Islamic-centric modernizers who were the editors for the newspaper Aiqap. Some of the most important editors of the Qazaq newspaper was Akhmet Baitursynov, who was editor-in-chief, Alikhan Bokeikhanov, and Myrzhaqyp Dulatov, and they would go forth to become key members of the future Alash state. Some of the most important editors of the Aiqap newspaper were Mukhamedzhan Seralin, Bakhytzhan Qaratev, and Zhikhansha Seidalin.

What was the Alash platform? The two key pillars of their platform were land rights and preserving Kazakh identity.

Akhmet Baitursynov, Alikhan Bokeikhanov, and Myrzhaqyp Dulatov

[Image Description: An image of three Asian men sitting together. The man on the left has short black hair and a droppy mustache. He is wearing glasses and a white shirt, black tie, and black suit. The man in the middle has shaved black hair and a heavy mustache. He is also wearing a white shirt, black tie, and black suit. The man on the right has black hair and thin mustache. he is wearing a white shirt, a black bowtie, and a grey suit.]

Land Rights

We’ll start with land rights, because that is why really differentiates the Steppe from the rest of Central Asia. As we mentioned, the Russians were taking Kazakh land, and making land ownership dependent on one’s sedentary behavior. The Russians also published numerous pieces of propaganda belittling nomadic life. So, the Kazakhs had to determine whether to maintain their nomadic lifestyle or adopt a sedentary lifestyle.

Bokeikhanov, an editor of Qazaq newspaper, argued that the Russians wanted the Kazakh to settle down so they could give even more land (and most certainly the best land) to the Russians while giving the useless land to the Kazakhs and then blaming them for failing. Baitursynov picked up that argument and pointed out that the Kazakhs could not succeed unless they first learned how to farm, but the Russians weren’t interested in that aspect of sedentary life at all. They just pushed the Kazakhs to settle down and worry about the rest later. This could have come out of Russia’s (and the Tatar’s) lack of knowledge of the Kazakh situation but could have also been purposeful ignorance.

Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov argued for a gradual transition to sedentarization due the Steppe’s climatic conditions and lack of agricultural knowledge otherwise they would risk starvation (which Stalin proved in the 1930s). In a series of article, they argued that:

“If we ask what kind of economy is more suitable for Kazakhs-the nomadic or the sedentary-the question is incorrectly posed. A more correct question would be: what kind of economy can be practiced under the climatic conditions of the Kazakh steppe? The latter vary from area to area and mostly are not suitable for agricultural work. Only in some northern provinces do the climatic conditions make it possible to sow and reap. The Kazakhs continue wandering not because they do not want to settle down and farm or prefer nomadism as an easy form of economy. If the climatic conditions had allowed them to do so, they would have settled a long time ago.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 9

Displaying a better understanding of the science behind climate and agriculture than the Russians or the Soviets that would follow, the editors argued that the climate was the number one factor in nomadism and the Kazakhs could not become sedentary until they learned how to adjust to the demands of the land. Another article argued that sedentarism would lead to failed farming which would lead to wage work which led to great abuses and a higher chance of being converted to Christianity, so the Kazakhs must also learn handicrafts in addition to science. They described the Russian’s disinterested in their arguments as

“One may compare it with the dressing some Kazakh in European fashion and sending him to London, where he would either die or, in the absence of any knowledge and relevant experience, work like a slave. If the government is ashamed of our nomadic way of life, it should give us good lands instead of bad as well as teach us science. Only after that can the government ask Kazakhs to live in cities. If the government is not ashamed of not carrying out all the above-mentioned measures, then the Kazakhs also need not be ashamed of their nomadic way of life. The Kazakhs are wandering not for fun, but in order to graze their animals.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 10

It should be noted that the Alash did not equate nomadism with Kazakh identity. Instead, they argued that the Kazakhs (and I would argue extend that to the Kyrgyz and Bashkirs) were nomadic for a sensible and scientific reason and if the Russians were truly interested in helping the Kazakhs successfully transition to sedentarism, then they needed to provide the tools otherwise they were setting the Kazakhs up for failure.

Mukhamedzhan Seralin, an editor of the Aiqap newspaper, believed that the sooner the Kazakhs settled down the sooner they could gain a European level education and become competitive in the modern world while increasing the role of Islam in Kazakh society. He argued that:

“We are convinced that the building of settlements and cities, accompanied by a transition to agriculture based on the acceptance of lands by Kazakhs according to the norms of Russian muzhiks, will be more useful than the oppose solution. The consolidation of the Kazakh people on a unified territory will help preserve them as a nation. Otherwise, the nomadic auyls will be scattered and before long lose their fertile land. Then it will be too late for a transition to the sedentary way of life, because by this time all arable lands will have been distributed and occupied.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 10

The editors of Aiqap argued with the others on the need for greater education, various options for work, etc., but they believed that the Kazakhs could never have these things untilthey became sedentary whereas the editors of Qazap believed that the Kazakhs could not become sedentary until they had those things.

Kazakh identity

This leads to the second pillar in the Alash platform: preserving Kazakh identity.

For the Kazak intellectuals of all stripes, the second most important element of Kazakh society was education and literature. They were worried about the poor education opportunities that centered Kazakhness instead of Russianness, available to Kazakh children. Even after primary school, the Kazakh educational options were limited: either they try to get accepted into a madrassa or go to Russia for further education. The Kazakh intellectuals learned of the new teaching methods the Jadids championed via their southern neighbors as well as the Tatars in the area and used literature to encourage the Kazakh people to focus on schooling.

Akhmet Baitursynov was focused on reforming primary schools and the lack of teaching materials, especially on the Kazakh language. The Qazap newspaper was the only newspaper who wrote in pure Kazakh. Baitursynov answered their detractors as followed:

“Finally, we would like to tell our brothers preferring the literary language: we are very sorry if you do not like the simple Kazakh language of our newspaper. Newspapers are published for the people and must be close to their readers.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 19

The Kazakh intellectuals resisted the Tatar clergy’s attempts to subsume Kazakh language to the Tatar language, eventually arriving at a compromise. This pressure around language inspired Akhmet Baitursynov to reform the Kazakh language, creating spelling primers, and improving the Kazakh alphabet multiple times. This book was soon used in primary schools. He also published a textbook on the Kazakh language which studied the phonetics, morphology, and syntax of the Kazak language as well as a practical guide to the Kazakh language and a manual of Kazakh literature and literary criticism.

Meanwhile Bokeikhanov focused on creating a unified Kazakh history, believing that “History is a guide to life, pointing out the right way.” Together Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov focused on collecting Kazakh folklore, the history of their cultures and traditions, and shared world history with other Kazakhs through their newspapers. They encouraged Kazakh writers to write down their poems and stories, fearful that they would be lost if Kazakhs stuck purely to an oral tradition.

For intellectuals like Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov, Kazakhness was connected to a cultural identity as opposed to a religious identity. Bokeikhanov supported the idea of separation between religion and state and resisted the Aiqap’s call for introduction to Sharia law. Bokeikhanov believed that they should codify and record Kazakh laws, customs, and regulations to counter corruption and bribery, instead of relying on Sharia law. The Kazakh people had a different relationship to Islam than the other peoples of Central Asia (which may have been why the Russian missionaries were initially confident the Kazakhs would be easiest to convert). While the editors of Aiqap believed that sedentary life would create closer ties to Islam, the editors of the Qazap newspaper believed that Islam was a part of Kazakh society but didn’t equal Kazakh society.

1905 Russian Revolution

We’ve talked quite a bit about what the Alash stood for, but how did this translate into political action? The Kazakhs, like many other Central Asians, were initially excited about the 1905 Revolution, which created a State Duma that “welcomed” Central Asians as members for about two Dumas. When the Kazakhs could participate, they sent Alikhan Bokeikhanov and Mukhamedjan Tynyshpaev.

After the Second Duma, the Kazakhs were no longer permitted to send their own deputies, so they either had to rely on the Tatar deputies of the Muslim Faction of the Russian Duma or find support elsewhere. The Kazakh intellectuals believed that the Tatars had no real knowledge of Kazakh needs and distrusted them. So, they turned to the Russian Constitutional-Democratic Party i.e., the Kadets.

The Kadets sold themselves as an umbrella party that advocated for civil rights, cultural self-determination, and local legislation that would allow for the use of native languages at schools, local courts, administrations, and institutions. Even though the Kadets and the Alash didn’t agree on land rights, they still became allies. The tension between the two parties would not disappear, especially following the 1916 Revolt (which the Alash, like the Jadids, tried to prevent), but they also acknowledged that the Kadets were the only game in town.

1917 Russian Revolution

The 1917 Revolution changed all of that by allowing the indigenous peoples and settlers to create their own forms of government. In April 1917, they would form their own All-Kazakh Congress in Orenburg where they passed a resolution calling for the return of Steppe land to Kazakh peoples, control over local schools, and the expulsion of all new settlers in Kazakh-Kyrgyz territories.

The Alash used 1917 to win local support, focusing on winning the support of the most influential leaders of the local communities and trusting the elders to use tribal affiliations to mobilize the people under the Alash banner. The Kazakh intellectuals dug deep into Kazakh history to unify the people under Alash, the father of all Kazakhs, creating a unified history from creation to modernity. This can be thought of as similar to the Jadids attempts to trace Uzbekness back to Timur.

They also worked with the Provisional Government in Russia, and with the various councils and meetings held by their Jadid counterparts in Turkestan, but ran into great friction because their Tatar, Uzbek, Tajik, etc. counterparts didn’t truly appreciate how important the land issue was for the Kazakhs. They were also wary of the Ulama’s version of a council, wanting to maintain the traditionally limited role of Islam in Kazakh society.

Because of the differences in priorities and the role of Islam, the Alash would go their own way while continuing to support the efforts of other indigenous peoples. They would continue to serve on the various councils and even took part in the creation of the Kokand Autonomy, but knew they needed their own Congresses and their own autonomous state to protect their people and achieve meaningful land reform.

The Kokand Autonomy created three seats for Alash members, believing that two southern Kazakh oblasts would be part of the Kokand Autonomy whereas the Alash wanted a unified Kazakh state. Bokeikhanov explained the Alash’s position as follows:

“Turkestan should first become an autonomy on its own. Some of our Kazakhs argue it would be correct to join the Turkestanis. We have the same religion as the Turkestanis, and we are related to them. Establishing an autonomy means establishing a country. It is not easy to lead a country. If our own Kazakhs leading the country are unfortunate, if we make the argument that Kazakhs are not enlightened, then we can argue that the ignorance and lack of skill among the people of Turkestan is 10 times higher than among Kazakhs. If the Kazakhs join the Turkestani autonomy, it would be like letting a camel and a donkey pull the autonomy wagon. Where are we headed after mounting this wagon?” - Ozgecan Kesici, 'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity', 1145

The Alash similarly considered joining the Siberian Autonomy movement but broke away once more over the issue of Kazakh autonomy. As Bokeikhanov explained:

“In practice, the autonomy of our Kazakh nation will not be an autonomy of kinship, rather, it will be an autonomy inseparable from its land.” - Ozgecan Kesici, 'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity', 1146

Failing to find neighbors who would respect their autonomy and facing extreme violence because of the Russian Civil war that was working itself way through Siberia, the Alash would proclaim the creation of the Alash Autonomy during the Second All-Kazakh Congress in December 1917. This would be the first time a Kazakh state existed since the Russian invasion in 1848. This autonomous state would be ruled by the Alash Orda, a government made up of many of the modernizing intellectuals who worked at the Qazap and Aiqap newspapers. Alikhan Bokeikhanov was elected its president. Whatever relief they may have felt at creating a state government must have been quashed by the understanding that civil war was at the Steppe’s door and sooner or rather they would have to choose a side and risk their long fight for autonomy.

References

'Challenging Colonial Power: Kazakh Cadres and Native Strategies' by Gulnar Kendirbai, Inner Asia 2008, Vol 10 No 1

'"We are Children of Alash..." The Kazakh Intelligentsia at the beginning of the 20th century in search of national indeitty and prospects of the cultural survival of the Kazakh people' by Gulnar Kendirbai, Central Asian Survey, 1999, Vol 18 No 1

'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity' by Ozgecan Kesici, Nationalities Papers, 2017, Vol 45 No 6

'Repression of the Kazakh Intellectuals as a sign of weakness of Russian Imperial Rule'by Tomohiko Uyama Cahiers du Monde russe 2015 Vol 56, No 4

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Coexistence by Shoshana Keller Published by University of Toronto Press, 2019

#history blog#season 2: central asia#central asian history#central asia#kazakhstan#qazaqstan#qazaq history#kazakh history#alikhan bukeikhanov#Akhmet Baitursynov#Spotify

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Ouzbekistan (1930) Ambient Music

#ouzbekistan#silk road#uzbekistan#kazakhstan#kazakh culture#kazakh history#afghanistan#turkmenistan#Youtube

0 notes

Link

Handmade products of Central Asian.........

1 note

·

View note

Text

happy april fools, may your aprils be fooled, I would like to share one funny thing I learned in kazakh history a long time ago

there were many predecessor states that controlled parts of modern-day kazakhstan before the main kazakh khanate that was established in the late 1400s, one of them being the white horde (ak orda), with one of their first khans being called

sasy buka (sasibuqa), or as I would like to interpret it

sussy baka

Bibliography:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sasibuqa

https://dbpedia.org/page/Sasibuqa

https://e-history.kz/en/amp/history-of-kazakhstan/show/9548

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

1) the concept of "bourgeois nomads" is quite hard to wrap your head around. A lot of Soviet ideology presented in this book is what we in Ukraine call "pulling an owl onto a globe"

2) despite calling themselves anti-imperialist, Soviet policy towards Qazaqs stinks of russian imperialism, e.g. denouncing nomadic practices as "culturally backward", despite them being more appropriate to Qazaqstan's climate; and russians' agrarian tradition as more "civilized" just because it's russian

3) It was hard to put this in words when all I wanted was to swear. I really need to learn a couple of quasaq swears to accompany my reading

[Book: Sarah Cameron - The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence and Making of Soviet Kazakhstan]

#history#kazakhstan#Aşarşılıq#Qazaqstandağı#famine#artificial famine#ussr#soviet history#communism#kazakh history#quasaqstan

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kazakhs and our ancestors were for a very ling time nomadic. Our culture is built around it in many ways that I don't want to delve into right now.

The reason for this is what the land we live on is: a steppe. It is not that good for agriculture because the climate is too harsh, and sometimes there isn't even enough water(most steppes in Kazakhstan are actually desert-steppes).

Even livestock isn't really that good, because they would feed to much, so staying in one place wasn't really possible.

The thing is, this wasn't like. Hundred people going randomly around all of Kazakh Khanate.

Imagine a family. They are one yurt. An aul might consist from a few of them or hundreds of them. Every family is a part of a tribe(it is a tad more complicated than this with multiple levels, cause genealogy was really well kept among common people) which has designated land for them.

Now, depending on the land they were on for hundreds of years, they might need to nomad(?)/move(this doesn't feel like a right verb) two or four times a year to their own pastures which are largely left vacant at other times. And they move, with their every belonging, their house and all of their livestock. There are some nuances like some permanent housing, and going into towns and trading, but this was largely it.

Just imagine the level of organisation needed for something like that, from both a family and the whole country to make sure that no one oversteps, everybody has enough, and can survive.

You won't find many nomads in Kazakhstan today however. There are some outside of it, but here it was made difficult by Russian Empire and then killed off by USSR entirely.

#a lot of stuff still persists though#for example in some regions people might still set up yurts to have a celebration or a mourning#kazakh#kazakh history#kazakh culture#Kazakhstan#kazakhstan#i am confused why are these two different#ussr#in a way only#heads up i am not gonna discuss industrialisation and 'civilization' brought to 'barbarians'#at least not on this post#kazakhstan history

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saryozek / Сарыөзек ( Kazakhstan )

#Сарыөзек#soviet architecture#soviet art#soviet union#ussr#kazakhstan#kazakhstantravel#pickoftheday#explore#soviet#small town#streets#photooftheday#adventure#central asia#visitkazakhstan#kazakh history#travelphotography#buildings#aroundtheworld#architecture#travel#trip#cccp#world

15 notes

·

View notes