#miesian

Text

House (1952) built for himself in Geneva, IL, USA, by Jacques Brownson. Photo by the architect himself.

355 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Loft-Style in Chicago

#Example of a large trendy loft-style living room design with a ribbon fireplace#a stone fireplace and white walls high rise#led lighting#miesian#modern cabinetry#oak#living room

0 notes

Text

YELLOW METAL SCULPTURE AT MIESIAN PLAZA

Miesian Plaza is an office building complex on Lower Baggot Street, Dublin. It is designed in the International Style, inspired by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, particularly his Seagram Building

GEOMETRIC REFLECTIONS BY MICHAEL BULFIN

The plaza contains the sculptures Reflections by Michael Bulfin and Red Cardinal by John Burke.

Miesian Plaza (formerly known as the Bank of Ireland Headquarters) is an office building complex on Lower Baggot Street, Dublin. It is designed in the International Style, inspired by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, particularly his Seagram…

View On WordPress

#baggot street#bank of ireland#Dublin#Fotonique#geometric Reflections#Infomatique#iPhone 12 Pro Max#Ireland#Michael Bulfin#Mies van der Rohe&039;s Seagram Building#Miesian Plaza#Scott Tallon Walker#William Murphy#Yellow Metal Sculpture

0 notes

Text

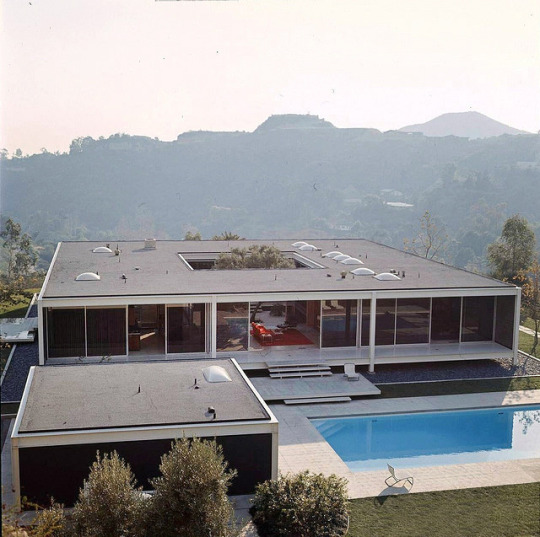

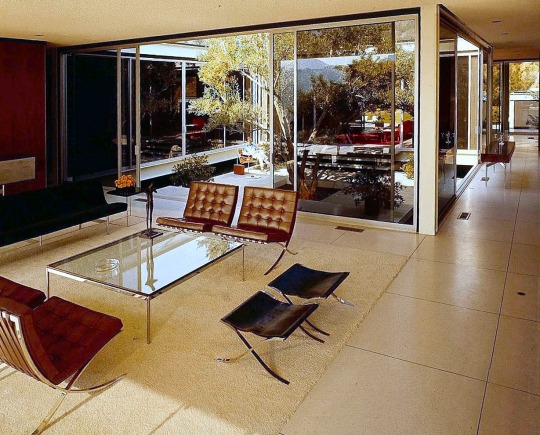

Rosen House | Craig Ellwood

West Los Angeles, CA | United States | 1963

The Rosen House of 1963, designed in conjunction with Jerrold Lomax, is among the most clearly Miesian of Craig Ellwood’s houses. The white steel frame and curtain walls loaded with glass, along with the way that the dwelling hovers a few feet above the ground, all recall the Farnsworth House in particular (see earlier post). Yet Ellwood, as alway, brings fresh ideas to this suburban pavilion. From the street, the pavilion is semi-enclosed by grey-brick infill that shields much of the facade, apart from the neat, central entrance. Stepping inside, the house unfolds and becomes semi-transparent. Its fulcrum is a central courtyard, flanked by glass, with a towering tree at the very centre; here, literally, nature is placed at the heart of the home. Living spaces and bedrooms radiate around this court and connect to the gardens via sheets of floor-to-ceiling glass. A series of service cores, encased in timber and mostly top-lit by skylights, hold the bathrooms and other services. A swimming pool to one side is partially sheltered by the square body of the house itself and a micro-pavilion holding the garage and plant room. The greenery around the residence has grown over the years, reinforcing the idea of a pavilion among the trees dispite the suburban context.

Images: © LIFE Magazine

Words: © thegreatdaydreamer

#architecture#modern architecture#midcenturyhome#midcenturymodernhome#luxury houses#luxuryhomes#swimming pool#bungalow#craig ellwood#west los angeles#california#lifestyle#house design#interior#interior design#urban architecture#urban nature#pavilion

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Building at 3101 Euclid Avenue (The Midtown Apartments)

3101 Euclid Avenue

Cleveland, Ohio 44115

The Building at 3101 Euclid Avenue in Cleveland, Ohio, was designed and constructed by the successful construction firm H.L. Vokes Company for a syndicate of investors led by Halle H. Lipp. It began construction in May 1958 and was finished in March 1959. In the 1800’s the same plot of land was home to a Samuel Andrew who named the site Andrew’s Folly, an 18,000 square feet, Gothic Revival home built in 1882-1885. The home was later demolished in 1923. The 1958 3101 Euclid Avenue Building was designed to be an office building. 3101 Euclid was the company’s first attempt at a metal curtain wall structure. The building was the tallest International Style-Miesian glass midrise built during the revitalization of the now designated “MidTown” area. It was designed to the maximum elevation permissible by City of Cleveland codified ordinances.

Now known as The Midtown Apartments, an apartment community in Cleveland, the building is situated on Euclid Avenue which was once known as “Millionaires Row.” The structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 7, 2017. The renovated historical building is conveniently located within a five-mile radius from hospitals, highways, public transportation, restaurants, and dancing, to name a few. At The Midtown Apartments residents will experience unmatched luxury and comfortable perks, such as front door access to RTA’s HealthLine, commutes to some of Downtown Cleveland’s most popular destinations, picturesque views of Lake Erie, and top-level amenities. The Midtown boasts of 90 luxury apartments, including pet-friendly studio, 1-bedroom, and 2-bedroom apartment rentals as well a penthouse. With outstanding amenities and features and beautifully designed interiors, The Midtown Apartments is the perfect place to call home.

0 notes

Photo

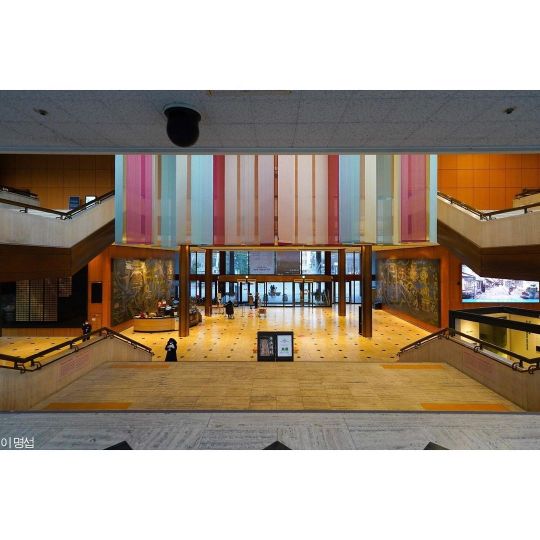

서울역사박물관, 종로구 신문로 2가/ 서울건축(김종성 건축가, 2002년 개관) 서울시 공공건축 중 가장 좋은 로비 대공간 #신문로2가 #서울역사박물관 #김종성건축가 #김종성 #서울건축 #miesian https://www.instagram.com/p/CYwXpnavXDc/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

My friend asked me what my dream home would look like. I told her that I don't let myself think about it because it is far from achievable.

I told her that I would want to move somewhere warmer, maybe out west, and bring some Chicago architecture with me.

Rather than buy I house, I'd want to build one inspired by Miesian Modern architecture (Chicago has a lot of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's architecture). He was able to achieve the "less is more" without making places look stark and uninviting as many of his predecessors would. The rigid grid of Miesian buildings is articulated with wood or stone or brick. The designs often feature uninterrupted plates of glass, blending the inside with the outside.

In my own home, however, I don't think I'd want to include the completely open and adaptable interior style. I think I'd reserve that more for the common areas. Additionally, as much as I like the horizontal look, I also like a bit of a gabled roof that can be incorporated in its use as a bit of a covered entry or for sunshade (I also like the way a high ceiling shapes the inside).

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Drawing Room at Arts Club of Chicago Draws Miesian Influence

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

House (1954) built for himself in Chicago, IL, USA, by John W. Moutoussamy

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Capitol Center Building (1966), G. Stacey Bennett, architect. Olympia, Washington.

Being renovated after years of no occupants.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

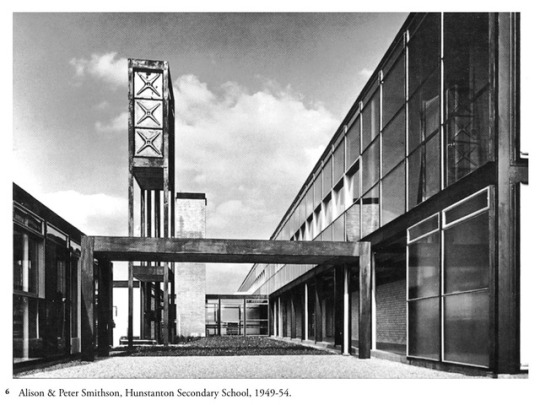

The Smithson's were made famous, after winning the competition for designing Hunstanton Secondary School. It's described to be...'an essay in Miesian modernity' according to the independentgroup.org.uk website. After this, they had not gotten anymore commissions during the 1950s. However, they had many competition entries which... ‘made an impact on the international stage of architecture’. For example, Golden Lane in 1952 and Sheffield University in 1953.

The ‘Streets In The Sky’ had many names such as: ‘Pedway’ and ‘three-dimensional city’ which was a concept at the time of brutalism, where people could ‘walk between the glassy offices and tucked-away churches of the City of London’ - Douglas Murphy. The idea behind this society-like

Furthermore, the Golden Lane never happened and was ‘polemically described the ‘street in the air’.’ - Notopia: fall of streets in the sky an article by Douglas Murphy.

The question that occurs with this architectural style is what made them think of implementing the idea of elevated floors, apart from just socialising? The answer lies further into the article, which Murphy writes...’The post-war attempts to make room for the automobile’ and he example Canary Wharf as one of many modern societies that have different levels but are ‘illusionistically decorated to appear traditional and street-like’.

In conclusion, this ‘streets in the sky’ was not only for the sole purpose of taking long walks and see where each pedway takes you. The logic behind it was to contribute to finding the solution to congestion and street affairs. However, it did seem to add more to the problem, because during Broadwater Farm riots of 1985, a police officer’s death was related to ‘youths exploiting the changing levels’ of the elevated walk paths and concludes that this architectural style also has faulty in design.

Links:

http://independentgroup.org.uk/contributors/smithson/ - biography of Alison and Peter Smithson

https://www.architectural-review.com/notopia/notopia-the-fall-of-streets-in-the-sky/10006944.article - article by Douglas Murphy

1 note

·

View note

Photo

London Open House 2021

Highlights

What with Covid, a couple of Septembers spent travelling researching books, a year giving a tour for Tokyo bike and another year opening my own house for London Open House, it's been ages since I actually visited anything myself. This year the festival is bigger than ever, and goes beyond just the weekend with a whole nine days of tours and events.

I've trawled the programme and picked out a few of my highlights

Saturday 11 September

Blackheath Quaker Meeting House

Architect: Trevor Dannatt

A new one to me! Small 1970s concrete Grade II listed building with a raised lantern. Designed to fit in with older buildings in the conservation , and make the most of the split-level site. Book here

Cheeky plug, if you're in Blackheath, why not do my Blackheath Walking Guide to modernist houses—available here).

Sunday 12 September

Central Hill Estate

Architect: Rosemary Stjernstedt

It's been at least 8 years since I visited Central Hill. There were rumours of it being demolished back then, but now it's really under threat. I've no idea (well I do) why Lambeth doesn't value its post-war housing schemes more. Central Hill was designed by Rosemary Stjernstedt for Lambeth Borough in 1963. The tree-lined housing estate on the ridge of Central Hill & Crystal Palace, incorporating open spaces, views over London, gardens and a sense of community. It's definitely worth a visit. Book tickets here for a lunchtime walk here

Saturday 11 and 12 Sunday September

Cressingham Gardens

Architect: Ted Hollamby

Another Lambeth scheme, and another also earmarked for redevelopment, is Ted Hollamby's wonderful Cressingham Gardens. Low-rise high-density estate located next to Brockwell Park. Innovative design with pioneering architectural elements & echoing natural topography. Under threat of demolition by Lambeth council. Tours provided of estate and rotunda.

Events, including walks of the estate and an exhibition, run Saturday and Sunday next weekend. Register here

Saturday 4 September

Page High Estate

Architect: Dry Halasz Dixon Partnership

The what estate? I've not heard of it. It was designed by Dry Halasz Dixon Partnership in 1975. According to the website: Page High is a hidden jewel of post-war London social housing, a 92-home rooftop village in Wood Green. High above the hue and cry of the High Road, Page High (Good Design in Housing award, 1976) is a model for social housing today. The walk is today, and there's only capacity for 10 so we may be too late for this now, but I'm putting it on the list for exploring on another day. More details here

Image via the Page High Estate residents association.

Saturday 4 and Saturday 11 September

South Norwood Library

Architect: Hugh Lea

Also under threat of demolition (a bit of a theme here eh?) is the South Norwood Library. The purpose-built library is a fine example of brutalist architecture. Designed by Hugh Lea, Borough Architect for Croydon, in 1968 the main volume shows Miesian influence with an abundance of natural light, interrupted by a concrete cuboid. Open for visits this Saturday and next. Register here

Sunday 5 September

Walter Segal Self-build Houses

Architect: Walter Segal

There's a good book out about Walter Segal which I must buy: Walter Segal Self-built Architect by Alice Grahame and John McKean published by Lund Humphries. Walters Way is a close of 13 self-built houses. Each is unique, built using a method developed by Walter Segal, who led the project in the 1980s. Houses have been extended and renovated. Sustainable features including solar electric, water & space heating. There are several events running on Sunday 5 September. More details here

Saturday 11 and Sunday 12 September

Fitzroy Park Allotments

If you've done my Fitzroy Park walk, you would have past the allotments, which are ordinally locked and not open to the public. Next weekend is an opportunity to the largest allotment site in the borough of Camden at approximately 3.5 acres. The lower part of the site was acquired by local government after the first world war as a result of requests by local people for the provision of secure growing space. Fitzroy Park Allotments – one of North London's best-kept bucolic secrets – is located on the south-west slopes of Highgate West Hill, alongside the much-cherished and well-known public open space of Hampstead Heath. Register here

(Image by Jim Osley)

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Screen, Stanley Tigerman, 1987, Art Institute of Chicago: Architecture and Design

This screen represents an important and infrequently collected area of work by architect Stanley Tigerman— furniture and interior design. Many of his residential projects completed in the 1980s and 1990s featured elaborate custom furnishings and built-ins, often featuring subversive references to classical architecture. This work was designed as part of a competition for the book publisher Rizzoli New York. Tigerman had a close and long standing relationship with the CEO, Gianfranco Monacelli, and the press published many of his books and journals over the years. This screen takes the overall form of a colonnade, with four connected pillars with stepped bases, capitals featuring semicircular brass bowls, and a bright pastel palette. Although unrealized, this element is one of the few furniture pieces by Tigerman in a museum collection, and an important aspect of his postmodern work. Stanley Tigerman was a major figure in the Postmodernism movement from the1970s–1990s, and remains one of the most provocative architects in Chicago. After founding his own practice in 1962, his early projects included designs for low-cost housing and experimental cities, and in the 1970s his work developed into a crusade against the dominance of post-Miesian corporate modernism in the United States. With built work and projects ranging from elaborate single families to sensitive designs for disadvantaged children and the homeless, Tigerman’s work is always framed and inspired by heady concepts including as irony, rupture, humor, and allusion. This interest led to his leadership in the seminal, yet never cohesive, group of architects known as the Chicago Seven. Since 1982, Tigerman has been in practice with his wife, Margaret McCurry, as Tigerman McCurry Architects. This acquisition joins a large collection of work by Tigerman McCurry at the museum, including an archive of material in the Ryerson and Burnham Library, and more than 30 original models. Gift of Stanley Tigerman and Margaret McCurry

Size: 188 × 183 × 27 cm (74 × 72 × 10 1/2 in.)

Medium: Mixed media

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/240545/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

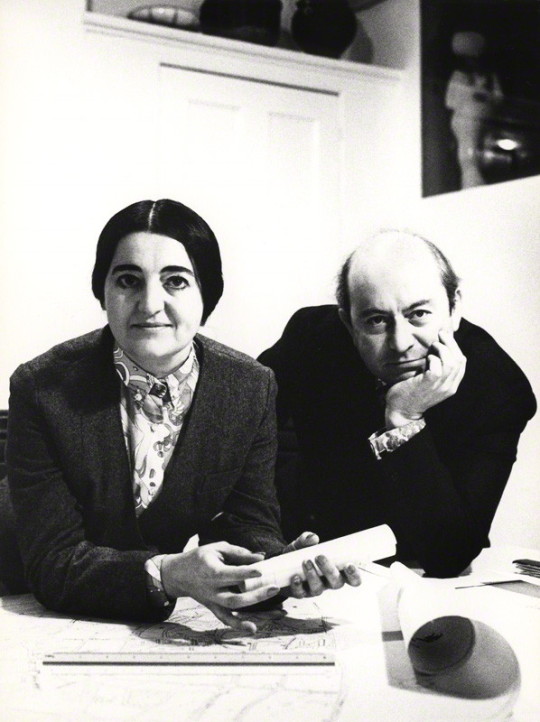

The Brutalism Post Part 3: What is Brutalism? Act 1, Scene 1: The Young Smithsons

What is Brutalism? To put it concisely, Brutalism was a substyle of modernist architecture that originated in Europe during the 1950s and declined by the 1970s, known for its extensive use of reinforced concrete. Because this, of course, is an unsatisfying answer, I am going to instead tell you a story about two young people, sandwiched between two soon-to-be warring generations in architecture, who were simultaneously deeply precocious and unlucky.

It seems that in 20th century architecture there was always a power couple. American mid-century modernism had Charles and Ray Eames. Postmodernism had Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Brutalism had Alison and Peter Smithson, henceforth referred to simply as the Smithsons.

If you read any of the accounts of the Smithsons’ contemporaries (such as The New Brutalism by critic-historian Reyner Banham) one characteristic of the pair is constantly reiterated: at the time of their rise to fame in British and international architecture circles, the Smithsons were young. In fact, in the early 1950s, both had only recently completed architecture school at Durham University. Alison, who was five years younger, was graduating around the same time as Peter, whose studies were interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served as an engineer in India.

Alison and Peter Smithson. Image via Open.edu

At the time of the Smithsons graduation, they were leaving architecture school at a time when the upheaval the war caused in British society could still be deeply felt. Air raids had destroyed hundreds of thousands of units of housing, cultural sites and had traumatized a generation of Britons. Faced with an end to wartime international trade pacts, Britain’s financial situation was dire, and austerity prevailed in the 1940s despite the expansion of the social safety net. It was an uncertain time to be coming up in the arts, pinned at the same time between a war-torn Europe and the prosperous horizon of the 1950s.

Alison and Peter married in 1949, shortly after graduation, and, like many newly trained architects of the time, went to work for the British government, in the Smithsons’ case, the London City Council. The LCC was, in the wake of the social democratic reforms (such as the National Health Service) and Keynesian economic policies of a strong Labour government, enjoying an expanded range in power. Of particular interest to the Smithsons were the areas of city planning and council housing, two subjects that would become central to their careers.

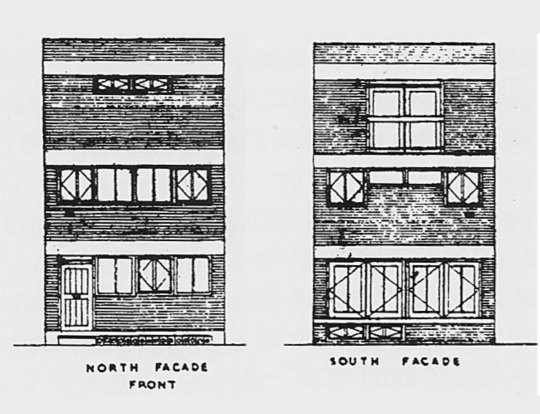

Alison and Peter Smithson, elevations for their Soho House (described as “a house for a society that had nothing”, 1953). Image via socks-studio.

The State of British Architecture

The Smithsons, architecturally, ideologically, and aesthetically, were at the mercy of a rift in modernist architecture, the development of which was significantly disrupted by the war. The war had displaced many of its great masters, including luminaries such as the founders of the Bauhaus: Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. Britain, which was one of the slowest to adopt modernism, did not benefit as much from this diaspora as the US.

At the time of the Smithsons entry into the architectural bureaucracy, the country owed more of its architectural underpinnings to the British architects of the nineteenth century (notably the utopian socialist William Morris), precedent studies of the influences of classical architecture (especially Palladio) under the auspices of historians like Nikolaus Pevsner, as well as a preoccupation with both British and Scandinavian vernacular architecture, in a populist bent underpinned by a turn towards social democracy. This style of architecture was known as the New Humanism.

Alton East Houses by the London County Council Department of Architecture (1953-6), an example of New Humanist architecture. Image taken from The New Brutalism by Reyner Banham.

This was somewhat of a sticky situation, for the young Smithsons who, through their more recent schooling, were, unlike their elders, awed by the buildings and writing of the European modernists. The dramatic ideas for the transformation of cities as laid out by the manifestos of the CIAM (International Congresses for Modern Architecture) organized by Le Corbusier (whose book Towards a New Architecture was hugely influential at the time) and the historian-theorist Sigfried Giedion, offered visions of social transformation that allured many British architects, but especially the impassioned and idealistic Smithsons.

Of particular contribution to the legacy of the development of Brutalism was Le Corbusier, who, by the 1950s was entering the late period of his career which characterized by his use of raw concrete (in his words, béton brut), and sculptural architectural forms. The building du jour for young architects (such as Peter and Alison) was the Unité d’Habitation (1948-54), the sprawling massive housing project in Marseilles, France, that united Le Corbusier’s urban theories of dense, centralized living, his architectural dogma as laid out in Towards a New Architecture, and the embrace of the rawness and coarseness of concrete as a material, accentuated by the impression of the wooden board used to shape it into Corb’s looming, sweeping forms.

The Unité d’habitation by Le Corbusier. Image via Iantomferry (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Little did the Smithsons know that they, mere post-graduates, would have an immensely disruptive impact on the institutions they at this time so deeply admired. For now, the couple was on the eve of their first big break, their ticket out of the nation’s bureaucracy and into the limelight.

The Hunstanton School

An important post-war program, the one that gave the Smithsons their international debut, was the expansion of the British school system in 1944, particularly the establishment of the tripartite school system, which split students older than 11 into grammar schools (high schools) and secondary modern schools (technical schools). This, inevitably, stimulated a swath of school building throughout the country. There were several national competitions for architects wanting to design the new schools, and the Smithsons, eager to get their hands on a first project, gleefully applied.

For their inspiration, the Smithsons turned to Mies van der Rohe, who had recently emigrated to the United States and release to the architectural press, details of his now-famous Crown Hall of the Illinois Institute of Technology (1950). Mies’ use of steel, once relegated to being hidden as an internal structural material, could, thanks to laxness in the fire code in the state of Illinois, be exposed, transforming into an articulated, external structural material.

Crown Hall, Illinois Institute of Technology by Mies van der Rohe. Image via Arturo Duarte Jr. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Of particular importance was the famous “Mies Corner,” consisting of two joined exposed I-beams that elegantly elided inherent problems in how to join together the raw, skeletal framing of steel and the revealing translucence of curtain-wall glass. This building, seen only through photographs by our young architects, opened up within them the possibility of both the modernist expression of a structure’s inherent function, but also as testimony to the aesthetic power of raw building materials as surfaces as well as structure.

The Smithsons, in a rather bold move for such young architects, decided to enter into a particularly contested competition for a new secondary school in Norfolk. They designed a school based on a Miesian steel-framed design of which the structural elements would all be visible. Its plan was crafted to the utmost standards of rationalist economy; its form, unlike the horizontal endlessness of Mies’ IIT, is neatly packaged into separate volumes arranged in a symmetrical way. But what was most important was the use of materials, the rawness of which is captured in the words of Reyner Banham:

“Wherever one stands within the school one sees its actual structural materials exposed, without plaster and frequently without paint. The electrical conduits, pipe-runs, and other services are exposed with equal frankness. This, indeed, is an attempt to make architecture out of the relationships of brute materials, but it is done with the very greatest self-denying restraint.”

Much to the upset and shock of the more conservative and romanticist British architectural establishment, the Smithsons’ design won.

Hunstanton School by Alison and Peter Smithson (1949-54). Photos by Anna Armstrong. (CC BY NC-SA 3.0)

The Hunstanton School, had, as much was possible in those days, gone viral in the architectural press, and very quickly catapulted the Smithsons to international fame as the precocious children of post-war Britain. Soon after, the term the Smithsons would claim as their own, Brutalism, too entered the general architectural consciousness. (By the early 1950s, the term was already escaping from its national borders and being applied to similar projects and work that emphasized raw materials and structural expression.)

The New Brutalism

So what was this New Brutalism?

The Smithsons had, even before the construction of the Hunstanton School had been finished, begun to draft amongst themselves a concept called the New Brutalism. Like many terms in art, “Brutalism” began as a joke that soon became very serious. The term New Brutalism, according to Banham, came from an in-joke amongst the Swedish architects Hans Asplund, Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm in 1950s, about drawings the latter two had drawn for a house. This had spread to England through the Swedes’ English friends, the architects Oliver Cox and Graeme Shankland, who leaked it to the Architectural Association and the Architect’s Department of the London County Council, at which Alison and Peter Smithson were still employed. According to Banham, the term had already acquired a colloquial meaning:

“Whatever Asplund meant by it, the Cox-Shankland connection seem to have used it almost exclusively to mean Modern Architecture of the more pure forms then current, especially the work of Mies van der Rohe. The most obstinate protagonists of that type of architecture at the time in London were Alison and Peter Smithson, designers of the Miesian school at Hunstanton, which is generally taken to be the first Brutalist building.”

(This is supplicated by an anecdote of how the term stuck partially because Peter was called Brutus by his peers because he bore resemblance to Roman busts of the hero, and Brutalism was a joining of “Brutus plus Alison,” which is deeply cute.)

The Smithsons began to explore the art world for corollaries to their raw, material-driven architecture. They found kindred souls in the photographer Nigel Henderson and the sculptor Edouardo Paolozzi, with whom the couple curated an exhibition called “Parallel of Life and Art.” The Smithsons were beginning to find in their work a sort of populism, regarding the untamed, almost anthropological rough textures and assemblies of materials, which the historian Kenneth Frampton jokingly called ‘the peoples’ detailing.’ Frampton described the exhibit, of which few photographs remain, as thus:

“Drawn from news photos and arcane archaeological, anthropological, and zoological sources, many of these images [quoting Banham] ‘offered scenes of violence and distorted or anti-aesthetic views of the human figure, and all had a coarse grainy texture which was clearly regarded by the collaborators as one of their main virtues’. There was something decidedly existential about an exhibition that insisted on viewing the world as a landscape laid waste by war, decay, and disease – beneath whose ashen layers one could still find traces of life, albeing microscopic, pulsating within the ruins…the distant past and the immediate future fused into one. Thus the pavilion patio was furnished not only with an old wheel and a toy aeroplane but also with a television set. In brief, within a decayed and ravaged (i.e. bombed out) urban fabric, the ‘affluence’ of a mobile consumerism was already being envisaged, and moreover welcomed, as the life substance of a new industrial vernacular.”

Alison and Peter Smithson, Nigel Henderson, Eduoardo Paolozzi, Parallels in Life and Art. Image via the Tate Modern, 2011.

A Clash on the Horizon

The Smithsons, it is important to remember, were part of a generation both haunted by war and tantalized by the car and consumer culture of the emerging 1950s. Ideologically they were sandwiched between the twilight years of British socialism and the allure of a consumerist populism informed by fast cars and good living, and this made their work and their ideology rife with contradiction and tension.

The tension between proletarian, primitivist, anthropological elements as expressed in coarse, raw, materials and the allure of the technological utopia dreamed up by modernists a generation earlier, combined with the changing political climate of post-war Britain, resulted in a mix of idealism and post-socialist thought. This hybridized an new school appeal to a better life - made possible by technology, the emerging financial accessibility of consumer culture, the promises of easily replicable, luxurious living promised by modernist architecture - with the old-school, quintessentially British populist consideration for the anthropological complexity of urban, working class life. This is what the Smithsons alluded to when they insisted early on that Brutalism was an “ethic, not an aesthetic.”

Model of the Plan Voisin for Paris by Le Corbusier displayed at the Nouveau Esprit Pavilion (1925) via Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

By the time the Smithsons entered the international architectural scene, their modernist forefathers were already beginning to age, becoming more stylistically flexible, nuanced, and less reliant upon the strictness and ideology of their previous dogmas. The younger generation, including the Smithsons, were, in their rose-tinted idealism, beginning to feel like the old masters were abandoning their original ethos, or, in the case of other youngsters such as the Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, were beginning to question the validity of such concepts as the Plan Voisin, Le Corbusier’s urbanist doctrine of dense housing development surrounded by green space and accessible by the alluring future of car culture.

These youngsters were beginning to get to know each other, meeting amongst themselves at the CIAM – the International Congresses of Modern Architecture – the most important gathering of modernist architects in the world. Modern architecture as a movement was on a generational crash course that would cause an immense rift in architectural thought, practice, and history. But this is a tale for our next installment.

Like many works and ideas of young people, the nascent New Brutalism was ill-formed; still feeling for its niche beyond a mere aesthetic dominated by the honesty of building materials and a populism trying to reconcile consumerist technology and proletarian anthropology. This is where we leave our young Smithsons: riding the wave of success of their first project as a new firm, completely unaware of what is to come: the rift their New Brutalism would tear through the architectural discourse both then and now.

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon!

There is a whole new slate of Patreon rewards, including: good house of the month, an exclusive Discord server, monthly livestreams, a reading group, free merch at certain tiers and more!

Not into recurring donations or bonus content? Consider the tip jar! Or, Check out the McMansion Hell Store! Proceeds from the store help protect great buildings from the wrecking ball.

#brutalism#architecture#architectural history#brutalism post#smithsons#alison and peter smithson#british architecture#modern architecture#le corbusier#concrete#brutalist architecture

933 notes

·

View notes

Photo

서울역사박물관(서울건축, 김종성)의 봄 #서울역사박물관 #서울건축 #김종성 #Miesian https://www.instagram.com/p/B-kLRFEllNp/?igshid=168nxzfjt34fj

0 notes