#milford graves

Text

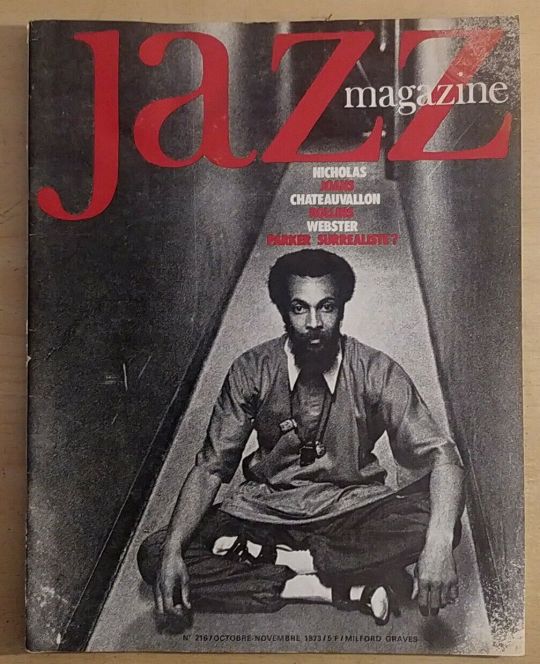

Milford Graves on the cover of Jazz Magazine, 1973.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

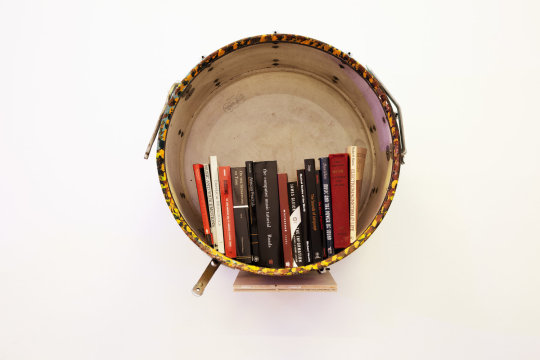

Milford Graves at Queens museum

"I've been thinking about sculpture as a teaching tool. There's a saying I used to always hear: "sculpture is frozen music." I want something with some kind of movement to it. I'm adding elements that are not static, like transducers. I also use my years and years of experience in music and my training in martial arts to understand sculpture. There were movements I used to do that would be very quiet, maybe something from aikido or tai chi. Very slow, very slow... then all of a sudden you would burst out with this explosive, passive-aggressive energy. I wondered how I would put that into a piece of sculpture. I thought the explosion would be to put together some unorthodox elements and have contradictions set in. If a person were to look at it, it would provoke a kind of psychological motion inside of them."

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

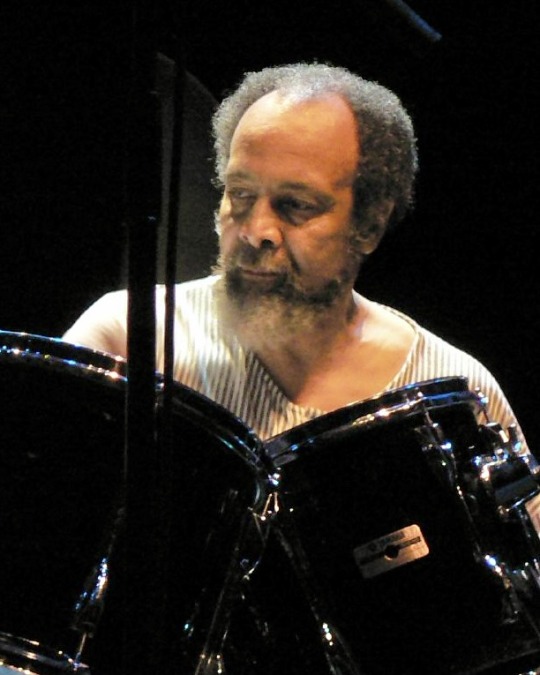

Happy Birthday, Milford Graves

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milford Graves, Arthur Doyle, Hugh Glover — Children of the Forest (Black Editions)

Children of the Forest by Milford Graves, Arthur Doyle, Hugh Glover

Drummer Milford Graves rarely recorded during his lifetime, and, until recently, most of his releases were long out of print. Corbett vs. Dempsey began to rectify that with key reissues of Bäbi, his trio with reed players Arthur Doyle and Hugh Glover, and The Complete Yale Concert 1966, his duos with Don Pullen. TUM records stepped in with Wadada Leo Smith’s Sacred Ceremonies, a 3 CD set including an incendiary duo with Graves along with a trio with Graves and bassist Bill Laswell. Since his death in February, 2021 Black Editions Archive has stepped up the game, digging in to Graves’ vaults, first with an issue of a trio set by Peter Brötzmann, Milford Graves, William Parker, and now, with Children of the Forest, a set of recordings captured in Graves’ Queens workshop with Doyle and Glover in the months leading up to the Bäbi session. The two-LP set documents a January 1976 duo session with Graves along with Glover on tenor saxophone, a brief drum solo from February of that year and a March trio session with Graves, Glover on klaxon, percussion and vaccine (a Haitian one-note trumpet) and Doyle on tenor saxophone and flute. The torrid rawness of these recordings looks toward the torrential barrage of Bäbi but brings out a more ritualistic edge to the playing.

Graves had spent his early years studying African drumming, tablas and playing timbales in Latin jazz bands and that sense of time, extended from African and Caribbean ceremonial music and ritual imbue these sessions. Hugh Glover talks about this and the time he spent with Graves, whom he refers to as Prof, in the extensive interview included with the LP set conducted by Jake Meginsky. “We were listening to the music of the peoples of the interior forest of the Congo… First, the Prof’s mood sets up a tribal-like atmosphere. It’s Congo-like — possession states. The rhythms, I think they immediately stimulated the need to dance… The next thing one must know and be aware of is that Milford Graves, he is not a time-keeping drummer like most jazz drummers. Prof represents the epitome of traditional hand drumming. I’m talking about ceremonial music and ritualistic sounds most familiar with divination.”

Hugh Glover only recorded a few times so the January duo session with him and Graves is a particular find. The first of the four improvisations starts out with the percussionist’s churning thunder, leading to the entry of the tenor player’s hoarse, braying cries. The two had known each other for a decade at that point and Glover had been part of a European tour of Graves’ quartet along with Joe Rigby and Arthur Williams. That symbiosis is immediately evident. There’s a fluid sense of polyphony and elastic polyrhythms at play as the two bound along with ebullient intensity. The music is charged with open, spontaneous interchange and while the intensity level is high, they never overpower each other. Graves’ percussion work is revelatory here, spilling across his kit with a limber, propulsive dynamism. One can hear the legacy of African and Latin American rhythms exploded out with the drummer’s lithe control of tuned skin and slashing cymbals, with masterful control of dynamics and timbre. The inclusion of a short, 2-minute recording from the session reveals their careful attention to detail as the two sound-check the room and their balance and then charge into a compact give-and-take. Their concluding 7-minute improvisation is a particular highlight as they ebb and flow with synchronous fervor.

The inclusion of a three-minute drum solo, recorded in February, is a brilliant addition to the set, particularly since Graves didn’t release any solo recordings until his two discs on Tzadik that came out in the late 1990s. On this 1976 recording, Graves distills his unified, multi-limbed attack into a roiling tempest of energy. Each thundering salvo, each cymbal crash, each resounding wallop of the bass drum is meted out with focus and intention. Glover remarks that listening to the solo recording he was struck by “the melody, and the melody of the tones that he gets, the way he rocks from one melody pitch to another. It has always been a mystery to me how Cuban drummers in Bata were able to modulate the rhythm and the meter. Well, it takes more than one player to do it Cuban style. Prof shows you can do it as one player.”

The three March improvisations with Graves, Glover, and Arthur Doyle provide a notable link in the trajectory toward the session recorded a few weeks later that would be released as Bäbi. Glover reminisces about the March session here, noting “When we played, though, Doyle and I, we weren’t thinking of BÄBI [a name Graves used for his conceptual approach to improvisation]. We were thinking of… well I know I was thing of, and I’m pretty sure he was thinking, how do we keep up with Prof!” While that may have been going through their minds, that uncertainty never reveals itself in their playing. Graves begins the 12-minute improvisation that opens the set with tuned cascades of rim shots and toms and the two quickly join in, with Doyle’s raspy tenor crying out against the shifting percussion. The modulating rhythms and meters of Graves’ solo are the foundation of the buzzing whorls that develop in three-way, spontaneous orchestration which never flags for a moment. The shorter second piece kicks off with an extended section of chattering drums, making way for the two partners to interject barking, ecstatic exclamations that mount with intensity as Graves hurtles in with clanging cowbell. The final piece is the most abstracted, with Doyle’s high-pitched flute skirling against the chafed yawp of Glover’s klaxon and Graves’ coursing flow. Here, improvisation and ritual are melded together with pelting focus.

Glover concludes his interview reminiscing that “It was like Prof was saying, there is no ensemble, there is no musical configuration that I can’t play with as long as I’m allowed to play what I want to play. In other words, his confidence factor was like, I know I have the essence of where any group wants to go. If they allow me to do my thing, I’ll take them there.” The sessions released on Children of the Forest are a fitting testament to that belief and provide a welcome addition to the documentation of the lineage of Graves’ musical legacy. Here's to hoping that Black Editions continues to mine the Prof’s archives.

Michael Rosenstein

#milford graves#arthur doyle#hugh glover#children of the forest#black editions#michael rosenstein#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#free jazz#eremite records

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ryan Collerd, A POLYMATH'S SPHERE, 2020. Photos of Milford Graves' home and laboratory.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milford Graves, 1977. Collage.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Milford Graves: Exploring the Rhythms of Life Through Music and Science

Introduction:

Milford Graves, a name that resonates in the realms of both avant-garde jazz and scientific exploration, stands as a testament to the boundless creative spirit that transcends conventional boundaries. A percussionist, drummer, educator, and groundbreaking researcher, Graves’ influence stretches across music, medicine, and the very essence of human existence. This blog post delves…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

MUZYCZNE REKOMENDACJE: Henry Threadgill Ensemble's „The Other One”

Pi Recordings, 2023

Najnowsza płyta Henry’ego Threadgilla zawiera rejestrację muzycznej częścią multimedialnego dzieła wykonanego i nagranego na żywo w Roulette Intermedium na Brooklynie w Nowym Jorku w 2022 roku, podczas drugiego z dwóch zaprezentowanych wówczas wykonań.

Album dostępny jest na Bandcampie

Całość – obok muzyki – obejmowała projekcję wideo, obrazów i fotografie, odtwarzanie…

View On WordPress

#Adam Cordero#Alfredo Colón#Christopher Hoffman#Craig Weinrib#David Virelles#Henry Threadgill#Jose Davila#Mariel Roberts#Milford Graves#Noah Becker#Peyton Pleninger#Pi Recordings#Sara Caswell#Sara Schoenbeck#Stephanie Griffin

0 notes

Video

youtube

#milford graves#bill fitch#willie bobo#albert ayler#don pullen#hermann von helmholtz#metronome#cardiology#education#the new school#john dewey

0 notes

Video

youtube

Babi, 1977, Milford Graves

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

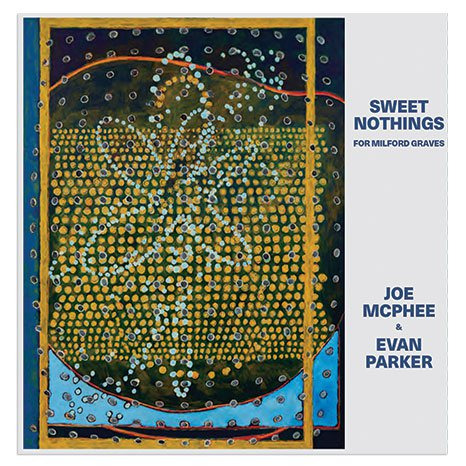

Joe McPhee & Evan Parker — Sweet Nothings for Milford Graves (Corbett Vs. Dempsey)

You might call Sweet Nothings For Milford Graves a chronology complicator. It is the third recording by Joe McPhee and Evan Parker, a pair of highly esteemed improvisers from either side of the Atlantic. But it was recorded in 2003, so it actually falls in between Chicago Tenor Duets (recorded in 1998, released by Okka Disk in 2002) and What / If / They Both Could Fly? (recorded in 2012, released the next year by Rune Grammofon). Discographers, revise your spreadsheets.

When an album comes out 19 years after it was recorded, questions arise. Why did it take so long? Why now? In the case of Sweet Nothings For Milford Graves, some delay is understandable. It was not recorded with the intent of making a record. Rather, it was snatched from the air by Malachi Ritscher, who was an extremely diligent documenter of Chicago’s improvisational musical scene for many years prior to his passing in 2006. It was de rigueur for him to record every set at events like the second Empty Bottle Festival of Jazz and Improvised Music, which included this concert, which was an off-site event held at the Chicago Cultural Center. While it was Ritscher’s habit to hand musicians a recording of a concert the next time they came to town, it’s quite possible that neither McPhee nor Parker, both inveterate travelers, dug their copies out off their respective shelves until COVID took them off the road. Or maybe it wasn’t unearthed until Ritscher’s recordings were archived by the Experimental Sound Studio after his death.

The second question is answered in part by playing the album. The rapport between the two musicians is manifest from its first seconds, as they initiate twin lines on soprano saxophones. First, one musician’s sound-stream writhes like a serpent around the other’s long-toned staff. Then they swap places, and carry on an exquisitely evolving discourse of complementary co-creation that feels too short at a bit over seven minute. Next, they bring out the tenors, matching ascending flutters to descending barks, wrapping precisely articulated notes around deftly turned slurs, and sliding into a moment of abstracted, blue balladry. You can hear both men’s deep engagement with the history of their instruments applied to the moment’s jointly imagined sound picture. The third sweet nothing (there are seven in total) begins in a realm of purer abstraction, with McPhee’s pocket trumpet issuing striated, breathy smears while Parker’s straight horn shoots pitches towards the stars. Yeah, you could say they were having a good day.

The literally mind might be wondering by now, what does any of this music have to do with Milford Graves? The late, august percussionist and scholar wasn’t directly involved in its making, since he was not at the festival that yielded this recording. The time of his passing corresponds more to the time when the album might have been entering pre-production than the time when the music was originally played. Perhaps it’s best to take the title as simply one more expression of appreciation among many that both Parker and McPhee have made towards their peers, comrades and inspirations.

So, back to that question — why issue another duo recording when two have already been made? Beyond the simple fact that the music is good, it’s likely that the label involved has a personal investment in this one. Half of Corbett Vs. Dempsey co-curated that festival in 2003 and you can bet that this recording stirs up some good memories. Or maybe I’m just projecting; after all, I was there too, and I can assure you that it has that effect on me.

Bill Meyer

#joe mcphee#evan parker#sweet nothings for milford graves#corbett vs. dempsey#bill meyer#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#milford graves#saxophone#duet#Malachi Ritscher#improvised music#chicago

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

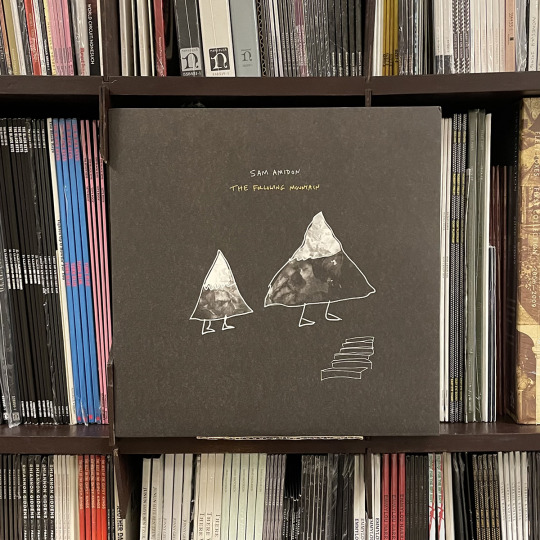

It was five years ago today: Sam Amidon's album The Following Mountain was released on Nonesuch. You can hear it again and get it on vinyl here.

The Following Mountain represented a new approach for Amidon, who shifted from his re-working traditional folk songs to present nine wholly original compositions, with some lyrics drawing on traditional sources. The album was created with producer Leo Abrahams and frequent Amidon collaborator Shahzad Ismaily, with a rare guest appearance by drummer Milford Graves.

#sam amidon#the following mountain#5 years ago#otd#leo abrahams#shahzad ismaily#milford graves#nonesuch#nonesuch records#vinyl

0 notes

Text

So What Became Of The Brokenhearted? They have collected themselves in Milford for the Detroit Social Club Show on Friday, August 25th!

That’s right, the brokenhearted along with many other “Motown Music Lovers” are gathering Friday, August 25th from 7:00 – 9:00 at the Center Street Park in Downtown Milford to listen to the Detroit Social Club perform songs from the classic Motown era!

Come sing-a-long or dance-a-long to the classic soul/R&B songs of the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. Songs like “I’ll Be Around, What’s Going On?, Inner…

View On WordPress

#Arthur Littsey#Blues Music#Carl Graves#Center Street Gazebo#Center Street Park#Chris Kent#Darnell Gardner#Detroit Blues Bands#Detroit Music and Vocal Group#Detroit Social Club Blues Band#George Posey#Little Brother Arthur David#Mark Croft#Milford#Milford DDA#Milford Friday Night Live

0 notes