#shelah marie

Text

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shelah Marie radiates self-love and Aries energy, reminding us all to embrace our inner fire. 🔥 Wearing a stunning Aries necklace, she's not just a vision of beauty; she's a powerful force of self-acceptance and empowerment.

💖 Dive into her wisdom and let her words inspire you to love yourself a little louder today.

Feeling inspired? Amplify your self-love journey and adorn yourself with an Aries necklace from our collection.

👇 Share how you're embracing self-love this season in the comments and tag a friend who embodies the Aries spirit!

Shop now to make a bold statement of self-love and astrological pride!

#astrology#zodiac#gifts#giftsforher#giftsforfriends#zodiac signs#♈️#aries#self love#aries szn#aries season

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Parable of the Persistent Widow. Luke 18:1-8.

What is a widow, according to the Torah? A widow is a person who has lost interest in their soul. In the Parable of the Vineyard, Jesus explains how to obtain awareness of one, a widow is someone who has lost interest in life. In the Torah, Tamar, a widow is told she has to wait for God to decide when her life will take on new meaning:

"So Judah said to his daughter-in-law Tamar, "Wait as a widow in your father's house until my son Shelah grows up," for he feared lest he also die as his brothers did. So Tamar went to live in her father's house. (Gen. 38:11)"

Tamar instead has an affair with a young goat and he emits into her. She returns to life and waits for Mashiach.

Who is the widow in the Parable of the Persistent Widow and how she is she like the one in the Torah?

18 Then Jesus told his disciples a parable to show them that they should always pray and not give up.

2 He said: “In a certain town there was a judge who neither feared God nor cared what people thought. 3 And there was a widow in that town who kept coming to him with the plea, ‘Grant me justice against my adversary.’

4 “For some time he refused. But finally he said to himself, ‘Even though I don’t fear God or care what people think,

5 yet because this widow keeps bothering me, I will see that she gets justice, so that she won’t eventually come and attack me!’”

6 And the Lord said, “Listen to what the unjust judge says. 7 And will not God bring about justice for his chosen ones, who cry out to him day and night? Will he keep putting them off?

8 I tell you, he will see that they get justice, and quickly. However, when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on the earth?”

A town is a happy person. Unless there is an adversary present, then this widows the town, and then it should naturally seek justice for whatever reproached its happiness.

So who is the Judge in the story, and why is he so stoic towards the idea? The duties of judges are detailed in Shoftim, but for the purposes of the Parable, they exist only because trouble exists. Once Mashiach takes place, there should be much less of a need for judges. Shabbat the ablity to sort reality from fantasy is for persons, Mashiach is for everyone, all at once.

Judges are the mechanism for these, they are the process by which perception becomes reason. This is unique to the human form, and it completely unnatural to us. We require a "crime" a reason to reason, and then a judgement and a sentence that will help us carry out the results of the tribunal. First is the power to veto any process contrary to what is reasonable.

The widow has witnessed something, a transgression, her eyes are open but she is immobilized, so the Judge is going to have to step in.

From 10440, אאֶפֶסדדאֶפֶס, apseddapes=

Ap=eyes open

Sed=

The verb εζομαι (hezomai) means to sit or be seated. It stems from the same PIE root "sed-" as does out English verb "to sit". In the classics this verb was only used for present and imperfect tenses and it and its derivatives alternate with ημαι (hemai) and its derivatives.

Our verb is not used independently in the New Testament but together with the preposition κατα (kata), meaning down from, down upon it forms the verb καθεζομαι (kathezomai), meaning to sit down or be seated down, but with an emphasis on being stationary rather than being seated on a chair: the opposite of Mary who "sat" at home (JOHN 11:20) was not Martha standing or lying down, but Martha on the move outside the house.

The opposite of Jesus who "sat" in the temple (MATTHEW 26:55) was not Jesus standing but Jesus on the move, outside the Temple. Sitting emphasizes immobility and specialization in an economic and cognitive sense, and demonstrates a lack of flexibility, diversification and development. Sitting is what lame people do, and see our article on the proverbial duo the lame and the blind.

da= understanding

pes= corruption

There are two roots with the form פסס (pss) in Biblical Hebrew, and one with the comparable form פשה (psh), which appears to have to do with one of the roots פסס (pss):

The root פשה (pasa) means to spread. It occurs only in Leviticus 13 and 14, and only in connection with leprosy and similar eruptions.

So the widow seems to want an underactive judge to address something of the caliber of an outbreak of leprosy or conditions contributing to the demise of the poor.

The verses after this part, state only the most advanced of men will comprehend how to overcome the crippling effects of the world around them and establish their humanity.

This is found in the gematria for verses 6,7, and 8, which are 14995, אדטטה, adetta, which translates as:

Ad=

The masculine noun עד ('ad), also spelled ועד (w'ad), literally meaning advancing time. This word is usually translated with perpetuity or forever: of past time (Job 20:4), but most often future time (Psalm 21:6). In the latter case the form is usually לעד (l'ad), literally for always.

Atta=

The verb אתה ('ata) is spelled the same as, and according to the Masoretes, pronounced slightly different from the masculine second person singular. Were we to stubbornly maintain that the two are connected, this verb would literally mean "to you". In reality it's commonly translated with to come; it's a rate poetic equivalent of the much more common verb בוא (bo').

But still, in order to express a coming, one would first require an awareness of you and me, so this verb is still not far removed from the above.

Our verb occurs about twenty times in the Old Testament, half of which in the Book of Isaiah. It describes bringing water to the thirsty (Isaiah 21:14), the coming of the morning (Isaiah 21:12), the getting together of humanity (Isaiah 41:5), the coming of the future in general (Isaiah 41:23), or a specific person and his policies (Isaiah 41:25), or wild beasts on the prowl (Isaiah 56:9).

Scary things may come (Job 3:25), or years (Job 16:22), or the brood of fools (Job 30:14), or the golden splendor around God (Job 37:22). It may describe the coming of God (Deuteronomy 33:2) or a coming to God (Jeremiah 3:22).

Jesus worries the world is too devolved to develop an interest in the things that will bring complete sentience to the world and happiness along with it. The levels of intelligence needed to solve the problems it has caused just seem too evasive. The result will widow all of us of a really good life if something isn't done.

0 notes

Text

Shelah Marie needs to quit playing g

452 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Like shelah said...where are the news post and Facebook filters?

#theblvckcool#somalia#double standard#black lives matter#shelah marie#disaster#disaster relief#disaster response#send help

213 notes

·

View notes

Video

instagram

😩❣️

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

https://www.instagram.com/p/BQlzr1NjsbS/

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

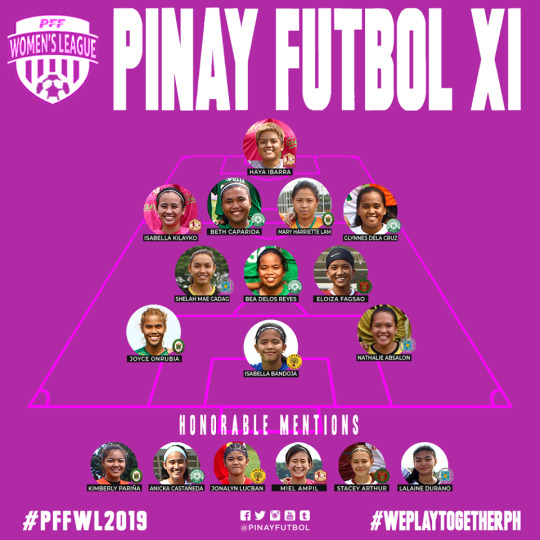

#PFFWL#Highlights#haya ibarra#isabella kilayko#beth caparida#mary harriette lam#glynnes dela cruz#shelah mae cadag#bea delos reyes#eloiza fagsao#joyce onrubia#Isabella Bandoja#nathalie absalon#kimberly pariña#anicka castañeda#jonalyn lucban#miel ampil#stacey arthur#lalaine durano#hiraya fc#de la salle university#far eastern university#university of santo tomas#university of the philippines#tuloy fc#Awards

1 note

·

View note

Photo

My week feels like it has been overflowed with Black Girl Magic. Just everything. $125 very well spent on experiences. I met and got to speak to some women who have played a virtual role in my personal growth and development and influenced me to ask myself some questions and consequently seek and determine those answers. Gaaaaah. And I've even met some women that even if I never see them again It felt great to share space and time and awesome energy with. Loooooong story short, I feel tremendously full and ultimately I'm glad I get to transfer this energy to my own little magical black girl.

#black girl magic#heyfranhey#shelah marie#Issa Rae#I hugged francheska 😩😩😩#and I hugged shelah and we talked about Beyoncé 😁#shoutout to Shelby!#x3#I got to see Issa be awkward in real life#her skin is God-level#yoooo sophomore me is livinggggggggg right now#but glad I'm not 19 though#wwarnd#rndrt

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sweet Melanated Marriage: Ace Hood & Shelah Marie Tie The Knot In Miami http://bit.ly/31KSNt9

0 notes

Text

Rapper, Ace Hood Shelah Marie are officially married (photos)

American rapper, Ace Hood and his longtime partner Shelah Marie are officially married.

The rapper whose real name is Antoine McColister got married to the self-love advocate and lifestyle entrepreneur on Friday, February 7, 2020. The wedding was attended by friends and family of the couple.

Ace Hood and Shelah Marie, who have been together for so many years before getting engaged in April…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

instagram

Shelah Marie 😍

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The understanding of birth as a time of great danger stemmed first and foremost from reality; death during labor and birth was not uncommon. Traditionally, pain and death during childbirth were attributed to the sin of Eve. The Bible already states that the pain of childbirth is a punishment for that sin: “In pain you shall bear children” (Gen. 3:16). Later, the Mishna explains that death at childbirth is the result of laxity in performing three specific commandments—the separation of the challah, the lighting of the Sabbath candles, and the observance of menstrual purity. These were known, in short, as Mizvot HaNaH (CHallah, Niddah, and Hadlakat haNer). A connection between these two explanations was implied.

…Although the Mishna attributes a woman’s death at childbirth to her failure to perform the three commandments that were her domain, and this understanding was accepted throughout the centuries, few medieval sources emphasize this specific cause of guilt. Rather, the consensus seems to be that at the hour of birth, all a woman’s deeds are judged and not just her performance of these three female commandments. The author of Sefer Hasidim warns people not to gossip or discuss any bad deeds the woman may have done, since any reminder of her sins might tip the scales against her. Instead, the parturient was to be prayed for. In fact, the first known mention of blessings for the sick connected to the reading of the Torah are blessings for the parturient.

These understandings again highlight the complex web of connections between religious understandings and biological and social realities. Many women died in childbirth, and, as in the case of many other deaths in the Middle Ages, the justification offered was religious. The belief that women died during childbirth because of their sins is, of course, not uniquely Jewish. It might even have been of greater importance in Christian sources. In Christianity, the origin of pain and death during childbirth was also assigned to Eve. Christians, like Jews, believed that women who gave birth without pain were not in Eve’s lot. In Christian tradition, the Virgin Mary was regularly characterized as not having suffered at birth, while in Jewish tradition, only the midwives in Egypt were ascribed this quality.

In fact, as Ulrike Rublack has recently shown, women who did not suffer during childbirth were viewed with tremendous suspicion. Pain during childbirth was the lot of women and they were expected to bear this pain with perseverance. Birth was also a symbol of the mundane world and its trials and tribulations. A central source in this connection was Midrash Yezirat haValad (The Midrash of the Creation of the Newborn), which was well known in medieval Ashkenaz. …The Midrash has two versions; one describes the fetus’s encounter with the world before leaving the womb and after being born, whereas the other explains the creation of a fetus in great detail.

According to the Midrash, the creation of the embryo is the product of cooperation between God, man, and woman, and is assisted by an angel called Layil (Night) “When a man comes to have intercourse [leshamesh mitato] with his wife, God calls the angel responsible for pregnancy and says: “Know that tonight this man is sowing the creation of a man.” The Midrash also explains how the fetus is created: R. Eliezer says the man sows white and the woman sows red and they mix with each other and from them the fetus is created according to the will of God.... The white that the man sows, from it the bones and tendons and brain and nails are formed, as well as the white in the eyes. The red that the woman sows, from it the skin and flesh and blood are created, as well as the black in the eyes. Spirit and soul and image and wisdom . . . and courage—they are given by God.

The Midrash describes the time spent by the fetus inside his mother’s womb and divides this period into three parts. It also explains that the sex of the baby is determined within the first forty days. These understandings are medical explanations that can be traced back to Aristotle’s medical treatises on obstetrics. For example, it was believed that the male’s soul is formed forty days after conception, and the female soul eighty days after conception. These numbers also explain the duration of ritual impurity after birth, as mentioned in the Bible: forty days for males and eighty for females.

Consequently, medieval Jewish sources instruct expectant fathers to pray for the birth of a son during the first forty days of a pregnancy. After these first forty days, they believed that the gender of the child had been determined; thus, they prohibited praying for a specific gender. Although medieval writings discuss the centrality of the father in the formation of the fetus and the development of the different parts of his body, the determination of the gender of the fetus was attributed to his or her mother. The extent of the mother’s enjoyment of the act of procreation determined the gender of the child. This belief was shared by Jews and Christians alike.

Medieval Jewish texts provide many other details on pregnancy and birth. Although it was commonly accepted that pregnancy lasted nine months, medieval medical sources understood that the term of pregnancy was somewhere between seven and nine months. Children born after an eight-month term were doomed to death, but those born after a seven- or nine-month term were healthy children. Some halakhic discussions, as well as exegetic texts, distinguish between these two possibilities. For example, most medieval biblical commentators understood the births of the ten tribes as following short pregnancies, whereas Jacob and Esau underwent a full-term birth, as it is written, “when her time to give birth was at hand” (Gen. 25:24).

These ideas on pregnancy had practical implications as well. For example, Hasidei Ashkenaz were very concerned about women giving birth on the Sabbath. Although helping a woman in travail was permitted and overrode the laws of the Sabbath, Hasidei Ashkenaz preferred to avoid such an instance. They determined that the duration of pregnancy as between 271 and 273 days. Consequently, they believed they could calculate the day of the baby’s birth. Thus, the readers of Sefer Hasidim were instructed to refrain from sexual intercourse on Sundays, Mondays, and Tuesdays, days that might lead to a Sabbath birth. These many references to birth and its processes in halakhic writings testify to men’s intimate knowledge of this world of women.

Although men were excluded from the birth chamber, they were well aware of the many activities within. We may even situate the physical location of the father during birth. One commentator derives the names given to Judah’s sons from his involvement in their respective births. Judah’s first son was called Er (literally, awake); the commentator explains that Judah was awake all night and listened to his wife’s screams during labor. The second son was called Onan (lament), for Judah cried and lamented his wife’s pain during birth. His third son was called Shelah, (literally, hers), since “the sorrow was hers alone, as he was at Kziv at the time of her birth.” (Gen. 38:5)

In the account of the birth of twins related later in that chapter, commentators remark on the birth of twins in medieval culture and the methods of examining and determining multiple births. The male authors display familiarity with the female anatomy of birth as well. For example, Rashi explains what the placenta is and says: “It is a kind of clothing that the baby lies in and is called ‘vashtidor’ in French.” It is interesting to note that, in many of these discussions, including most cases of Rashi, commentators almost always provides a parallel vernacular term when discussing issues related to childbirth. Clearly, the women who provided accounts of birth used these terms, whereas the Hebrew names were not well known.”

- Elisheva Baumgarten, “Birth.” in Mothers and Children: Jewish Family Life in Medieval Europe

24 notes

·

View notes