#steven shaviro

Photo

Steven Shaviro, The Cinematic Body

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maurice Blanchot (1981) suggests that the image is not a representational substitute for the object so much as it is—like a cadaver—the material trace or residue of the object's failure to vanish completely: "The apparent spirituality, the pure formal virginity of the image is fundamentally linked to the elemental strangeness of the being that is present in absence" (p. 83). The image is not a symptom of lack, but an uncanny, excessive residue of being that subsists when all should be lacking. It is not the index of something that is missing, but the insistence of something that refuses to disappear. Images are banally self-evident and self-contained, but their superficiality and obviousness is also a strange blankness, a resistance to the closure of definition, or to any imposition of meaning. Images are neither true nor false, neither real nor artificial, neither present nor absent; they are radically devoid of essence. Empty simulacra, copies for which there is no original, they tend to proliferate endlessly, repetitiously, without hope of regulation or control. The fleeting insistence of weightless images, of reflections and projections, of light and shadow, threatens to corrupt all standards, to exceed all limits, and to transgress every law.

Steven Shaviro The Cinematic Body

24 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Films and music videos, like other media works, are machines for generating affect, and for capitalizing upon, or extracting value from, this affect. As such, they are not ideological superstructures, as an older sort of Marxist criticism would have it. Rather, they lie at the very heart of social production, circulation, and distribution. They generate subjectivity, and they play a crucial role in the valorization of capital. Just as the old Hollywood continuity editing system was an integral part of the Fordist mode of production, so the editing methods and formal devices of digital video and film belong directly to the computing-and-information-technology infrastructure of contemporary neoliberal finance. There's a kind of fractal patterning in the way that social technologies, or processes of production and accumulation, repeat or 'iterate' themselves on different scales, and at different levels of abstraction

Steven Shaviro, Post-Cinematic Affect, pg. 2-3

#Shaviro#steven shaviro#post-cinematic affect#affect#media#film#video#music#marxism#labour#capital#ideology#ideological superstructure#valorization of capital#hollywood#neoliberalism#production of affect

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pastiche of this sort is a lot like dressing in drag: in both, it's a matter of piling up and juxtaposing stereotypical traits, thereby transforming them into eccentricities and quirks. Jameson somewhat misses the point, I think, when he argues that postmodern pastiche is "a neutral practice of such mimicry, without any of parody's ulterior motives, amputated of the satiric impulse, devoid of. . . any conviction that alongside the abnormal tongue you have momentarily borrowed, some healthy linguistic normality still exists." For the "blankness" of postmodern style in drag and pastiche is of course inspired precisely by our deep suspicion of "ulterior motives." The very notion of a "healthy. . .normality" is at the root of what oppresses us. We've heard this stuff about "normality" and "health" far too many times before. We're not complaining that the values people once believed in are now empty; to the contrary, we're doing our best to empty them more and more. Get used to it. Stealing is a thrill in itself; this enjoyment is the real reason for postmodern appropriation. We aim to undermine those "convictions" of authenticity and truth, of proper meaning and right order, that sometimes seem to be as dear to Marxist dialecticians as they are to bureaucrats in the Pentagon. Speaking in my own voice is a tedious chore, one that the forces of law and order are all too eager to impose. They want to make me responsible, to chain me to myself. "Man could never do without blood, torture, and sacrifices when he felt the need to create a memory for himself" (Nietzsche). But forgetting myself, speaking in others' stolen voices, speaking in tongues: all this is pleasure and liberation. Let a hundred simulacra bloom, let a thousand costumes and disguises contend.

Steven Shaviro, Doom Patrols

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Everything comes back to the zombies’ weird attractiveness: they exercise a perverse, insidious fascination that undermines our nominal involvement with the films’ active protagonists. The rising of the dead is frequently described as a plague: it takes the form of a mass contagion, without any discernible point of origin. The zombies proliferate by contiguity, attraction, and imitation and agglomerate into large groups. The uncanny power of Romero’s films comes from the fact that these intradiegetic processes of mimetic participation are the same ones that, on another level, serve to bind viewers to the events unfolding on-screen.

The Living Dead trilogy achieves an overwhelming affective ambivalence by displacing, exceeding, and intensifying the conventional mechanisms of spectatorial identification, inflecting them in the direction of a dangerous, tactile, mimetic participation. Perception itself becomes infected and is transformed into a kind of magical, contagious contact. The films mobilize forms of visual involvement that tend to interrupt the forward movement of narrative and that cannot be reduced to the ruses of specular dialectics. We cannot in a conventional sense “identify” with the zombies, but we are increasingly seduced by them, drawn into proximity with them.

The participatory contact that they promise and exemplify is in a deep sense what we most strongly desire; or, better, we gradually discover that it is already the hidden principle of our desire. Romero’s trilogy amply justifies Bataille’s suggestion that “extreme seductiveness is probably at the boundary of horror.” The first of these modes of seductive implication is a kind of suspension or hesitation. We watch alongside a protagonist who does not see anything—but who is waiting anxiously, for the zombies to appear, or for dead bodies to rise. Nothing happens; the instant is empty.

Of course, such scenes are a classic means of building suspense. But Romero gives the blank time of anticipation a value in its own right, rather than just using it to accentuate, by contrast, the jolt that follows. Sometimes he even sacrifices immediate shock effect, the better to insist upon the clumsy, hallucinatory slowness of the zombies’ approach, for even after the zombies have finally appeared, we are still held in suspense—waiting for them to come near enough to devour us, to embrace us with their mortifying, intimate touch. Such a pattern of compulsive, fascinated waiting is especially important in Dawn.

In one excruciatingly drawn-out scene, one of the barricaded human waits for the moment when his comrade, having just died in bed from zombie-inflicted wounds, will come back to life as one of them. There is nothing he can do; he simply sits, gun in hand, taking swigs from a bottle of whiskey. Ever so slowly, the sheets covering the corpse begin to move . . . Again at the very end of the film, the same character is tempted to remain behind and shoot himself in the head, instead of joining the woman survivor in a last-minute departure by helicopter. No true escape is possible; running away now only means accepting the horror of having to fight the zombies again someplace else.

One can put an end to this eternal recurrence only by not delaying, by shooting oneself immediately in the head, directly destroying the physical texture of the brain. The man hesitates for a long, unbearable moment, his gun at his temple, as the zombies approach—ravening after his flesh, but still shuffling along at their usual slow pace. Only at the last possible instant is he finally able to tear himself away. The dread that the zombies occasion is based more on a fear of infection than on one of annihilation.

The living characters are concerned less about the prospect of being killed than they are about being swept away by mimesis—returning to existence, after death, transformed into selves. The screams of the dying man in Dawn sound very much like (and are equated by montage with) the cries of the zombies. The man is most horrified not by his pain or his impending death but by the prospect of walking again; he promises with his last breath that he will try not to return. Of course, he fails: revivification is not something that can be resisted by mere force of will.

To die is precisely to give up one’s will, and thus to find oneself drawn, irresistibly, into a passive, zombified state. In these scenes, the protagonist’s momentary hesitation is already, implicitly, a partial surrender to temptation. A chain of mimetic transference moves from the zombies, to the man who dies and returns as a zombie, to the other man who watches him die and return, and to the audience fascinated by the whole spectacle. As the moments are drawn out, a character with whom we identify seems on the verge of slipping into a secretly desired incapacity to act, a passionate wavering and paralysis.

Living action is subverted by the passivity of waiting for death; indecision debilitates the self-conscious assertion of the will. In Dawn, the protagonists end up resisting this temptation and returning to a stance of action and resolve. But it’s only a small step from them to the wounded soldier in Day, who gives himself over entirely to the zombies. At such moments in the three films, it is as if perception were slowed down and hollowed out. As I wait for the zombies to arrive, I am uncannily solicited and invested by the vision of something that I endlessly anticipate but that I cannot yet see.

Gilles Deleuze argues that the sensorimotor link, the reflex arc from stimulus to response, or from affection to action, is essential to the structure of action narrative. But at such moments of waiting for the zombies’ awakening or approach, the link between apprehension and act and action is hollowed out or suspended, in what Deleuze calls a “crisis” in the act of seeing. The stimulating sensation fails to arrive, and the motor reaction is arrested. The slow meanders of zombie time emerge out of the paralysis of the conventional time of progressive narrative.

This strangely empty temporality also corresponds to a new way of looking, a vertiginously passive fascination. The usual relation of audience to protagonist is inverted. Instead of the spectator projecting himself or herself into the actions unfolding on the screen, an on-screen character lapses into a quasi-spectatorial position. This is the point at which dread slips into obsession, the moment when unfulfilled threats turn into seductive promises. Fear becomes indistinguishable from an incomprehensible, intense, but objectless craving. This is the zombie state par excellence: an abject vacancy, a passive emptying of the self.

But such vacuity is not nothingness, for it is powerfully, physically felt. The allure of zombiehood cannot be represented directly—it is a kind of mimetic transference that exceeds and destroys all structures of representation—but it lurks in all these excruciating, empty moments when seemingly nothing happens. Passively watching and waiting, I am given over to the slow vertigo of aimless, infinite expectation and need. I discover that implication is more basic than opposition; a contagious complicity is more disturbing than any measure of lack, more so even than lack pushed to the point of total extinction.

The hardest thing to acknowledge is that the living dead are not radically Other so much as they serve to awaken a passion for Otherness and for vertiginous disidentification that is already latent within our own selves. A second mode of voyeuristic participation in the Living Dead trilogy comes into play when the zombies finally do arrive. Romero gleefully exploits his viewers’ desires to experience and enjoy, vicariously, the rending apart and communal consumption of living flesh. These films literalize obscenity.

In their insistence on cannibalism and on the dismemberment of the human body, their lurid display of extruded viscera, they deliberately and directly present to the eye something that should not be seen, that cannot be seen in actuality. Audiences attend these films largely in the hope of being titillated by a violence that is at once safely distant and garishly immediate—extravagantly hyperreal. I’m taken on a wild ride, through a series of thrills and shocks, pulled repeatedly to the brink of an unbearable and impossible consummation.

The zombies’ almost ritualistic violation of the flesh allows me to regard, for an ephemeral instant, what is normally invisible: the hidden insides of bodies, their mysterious and impenetrable interiority. At the price of such monstrous destructiveness, I am able to participate in a strange exhibition and presentation of physical, bodily affect. These films enact the making evident, the public display, of my most private and inaccessible experiences: those of wrenching pain and of the agonizing extremity of dying.

I am fixated upon the terrifying instant of transmogrification: the moment of the tearing apart of limb from limb, the twitching of the extremities, and the bloody, slippery oozing of the internal organs. Fascination resides in the evanescent and yet endlessly drawn-out moment when the victim lives out his own death, an instant before the body is finally reduced to the status of dead meat.”

- Steven Shaviro, “Contagious Allegories: George Romero.” in Zombie Theory: A Reader

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading thee most eye-opening book about the state of capitalism and putting it down to go see the barbie movie. i contain multitudes

1 note

·

View note

Text

Derek Mears as Judge Holden

“Judge Holden's Weltanschauung-

His Theoretical Teaching

Since the hopes of a harmony and a Kantian "perpetual peace" prove to be untenable, all that remains is war, the "ultimate practitioner," who destroys by pushing things into their eternal existence. Like Heraclitus, the judge gives war its supremacy because war shows how things really are. It contains the principle of reality and points to the fact that existence, not the mind, has to come first. In a duel, it is only the outcome that counts. It does not matter which of the participants is right or wrong. War supersedes and overwrites such distinctions. Any other preconceived framework formed by the mind will fail the test of reality. In a Nietzschean manner, the judge gives the example of the moral law as an invention for the "weak." For Nietzsche, the weak are those who cannot come to a clear-cut decision and thus establish an end. McCarthy's nihilism is so systematic that the outcome is not moralizable post factum. One cannot even suggest that "might can be right" because power is absolute and cannot be represented in terms of right and wrong; it just is. The only possible law is the "historical law" or the law of necessity that is an immediate, immanent manifestation of what is.

The judge does not reject the mind, though; he is everything but a mindless killing machine. He just gives priority to the order of existence, the all-inclusive order that contains the mind itself. A thing will still exist whether one thinks of it or not. The mind cannot create existence; only existence can by being its own cause. And because the mind cannot will anything into existence, it has to be put in its right place and recognized for what it is: a mere mode of existence, like the body, among others. This means that it cannot impose the way it thinks, its own laws, its own mode of functioning, which is merely its own mode of existence, onto what exists. This happens only when the mind starts looking at itself and, like a sorcerer's apprentice, it opens a reflection that implies consciousness and that stretches into the infinite without being able to close it. The mind has to just become an instrument through which things that exist get their voice. This univocal perspectives is the substantial link between Spinoza and Nietzsche but will connect the judge and Chigurh as well.

The fact that the mind cannot rule over things doesn't impede it from knowing them though. In his reading of Blood Meridian, Steven Shaviro calls it a "radical epistemology" that "subverts all dualisms, of subject and object, inside and outside, will and representation or being and interpretation." Things are useful "breadcrumbs" for the dedicated archivist Judge Holden while Anton Chigurh calls them "instruments.” The principle of reality is thus discerned starting from bare facts. The judge is an avid collector in his notebook because they are God's "words": "He speaks in stones and trees, the bones of things. He archives material yet truthful artifacts as if to discover a road map that would help him find his way through the "maze" of existence. He is the one who singles out the "thread of order in the tapestry," thus knowing the (one) way of existence, the way things are (or become). It is in this sense only that he will be able to "dictate the terms of his own fate." This mastery is neither a creation/imposition of a new order nor an altering of an already given one. It neither shapes one's fate nor gets rid of it altogether; one is not beyond fate. Freedom emerges from finding this one path "and not some other way," this "thread of order" in the labyrinth that conquers a mystery, a darkness that generates fear so that one's decisions are taken from an active position rather than a passive one.

Like a memento mori, these facts will keep one grounded in the necessity of the "historical law," in the very "heart of darkness" that reminds one that "death and dying are the very life of darkness". In turn, they will keep the judge away from imaginative projections of the mind that generate superstition, mystery and fear. He records them like in a citation "a l'ordre du jour” in order to maintain the state of war and thus be closer to its eternity. "It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way" (BM 259).

Judge Holden loves war because it brings about "a new and broader view" (BM 261). War is the supreme game of life that teaches the unity of existence. "War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence. War is god" (BM 261). Playing games is "nobler" than any other action, and war is the supreme game because the wager is one's most precious possession: one's life. When one wages one's life, one wages oneself, one's identity that resides in the subject, the game will "swallow" both the player and the game itself, merging both subject and object in its unity. From the perspective of this unity of existence, one can access something more than one's life. It allows one to partake in a realm of eternity that goes beyond duration, beyond beginning and ceasing to be. At this point, even "notions of chance and fate are the preoccupations of men engaged in rash undertakings" (BM 159). The unity of existence is an all-inclusive whole that cannot be broken into contradictory parts. Its parts will be distinguished merely as forms that are still embedded in the whole. In this game of war, one cannot clearly distinguish and oppose necessity and randomness anymore. Better said, loving one's fate will affirm necessity and freedom at the same time. Further, life and death are not mutually exclusive anymore but rather inextricably connected as two halves of the same coin. Embracing one will by default affirm the other.”

- Adrian Mioc, ‘Holden and Chigurh, Cormac McCarthy and the Ethics of Power’

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

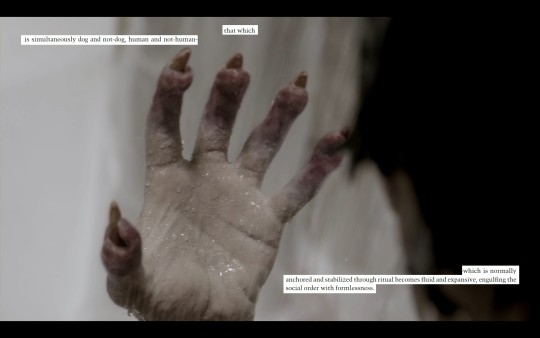

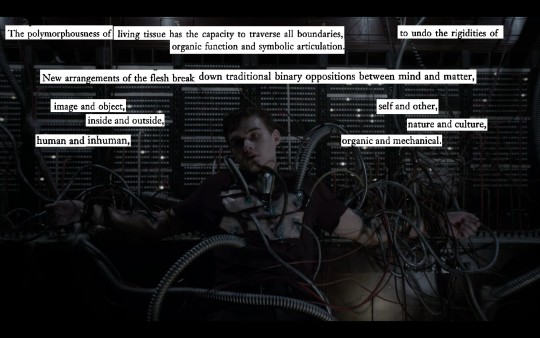

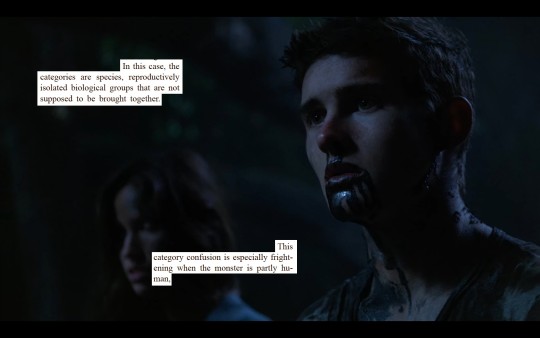

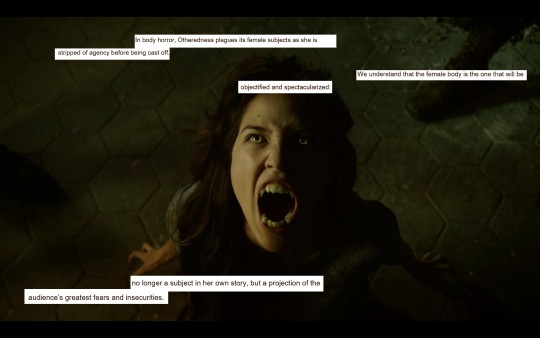

The Horror Genre in Teen Wolf

Dread, Taboo, and The Thing: Toward a Social Theory of the Horror Film by Stephen Price / Bodies of Fear: David Cronenberg by Steven Shaviro / Mutations and Metamorphoses: Body Horror is Biological Horror by Ronald Allan Lopez Cruz / Exploring Mutilation: Women, Affect, and the Body Horror Genre by Carina Stopenski

#teen wolf#teen wolf meta#the horror genre#body horror#werewolves#scott mcall#corey bryant#tracy stewart#lydia martin#jennifer blake#ethan and aiden#i am first and foremost a teen wolf scholar these days#i am the the only person who truly understand the field of teen wolf academic studies so i must make posts for y'all#mine#teen wolf academia

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actually, while we're shaming people for their 452 unread books, here's a list of unread books of mine of which I own physical copies, attached to the year I obtained them, so that you can all shame me into reading more:

2024: Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence (James Bridle; just started)

2021: Islands of Abandonment: Life in the Post-Human Landscape (Cal Flyn)

2024: Extreme Fabulations: Science Fictions of Life (Steven Shaviro)

2021: The Unreal & The Real Vol. 1: Where on Earth (Ursula K. Le Guin)

2023: A Study in Scarlet (Arthur Conan Doyle)

2023: Ritual: How Seemingly Senseless Acts Make Life Worth Living (Dmitri Xygalatas)

2023: Vibrant Matter: A political ecology of things (Jane Bennett)

2023: The History of Magic: From Alchemy to Witchcraft, from the Ice Age to the Present (Chris Gosden)

2018: Ways of Seeing (John Berger)

2022: An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (Ed Yong)

2020: Owls of the Eastern Ice: The Quest to Find and Save the World's Largest Owl (Jonathan C. Slaught)

2023: My Life in Sea Creatures (Sabrina Imbler)

2020: The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think (Jennifer Ackerman)

2023: Birds and Us: A 12,000-Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation (Tim Birkhead)

2020: Rebirding: Restoring Britain's Wildlife (Benedict Macdonald)

2022: The Song of the Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New Human (Siddhartha Mukherjee)

2022: An Anthropologist on Mars (Oliver Sacks)

2021: Sex, Botany & Empire: The Story of Carl Linnaeus and Joseph Banks (Patricia Fara)

2023: At The Mountains of Madness (H.P. Lovecraft)

2019: Invisible Cities (Italo Calvino; I have been trying to finish this forever and am so, so close)

2023: Brian Boru and the Battle of Clontarf (Sean Duffy)

2021: What is History, Now? How the past and present speak to each other (Helen Carr and Suzannah Lipscomb; essay collection, half-read)

2020: Winter King: The Dawn of Tudor England (Thomas Penn)

2022: Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (Silvia Federici)

2020: Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Touissant Louverture (Sudhir Hazareesingh; half-read)

2019: The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper (Hallie Rubenhold; 3/4 read)

2022: Lenin on the Train (Catherine Merridale)

2020: October: The Story of the Russian Revolution (China Miéville)

2019: The Villa, the Lake, the Meeting: Wannsee and the Final Solution (Mark Roseman)

2019: Heimat: A German Family Album (Nora Krug)

2018: Maus I: My Father Bleeds History (Art Spiegelman)

2020: Running in the Family (Michael Ondaatje)

2022: Wide Sargasso Sea (Jean Rhys; also never technically "finished" Jane Eyre, but I did my time, damn you)

2023: Time Shelter (Georgi Gospodinov)

2019: Our Man in Havana (Graham Greene; started, left unfinished)

2019: The Spy Who Came In From The Cold (John le Carré)

2021: Why I'm No Longer Talking to White People About Race (Reni Eddo-Lodge; half-read)

2017: Rebel Without Applause (Lemn Sissay)

2022: The Metamorphosis, and Other Stories (Franz Kafka)

2011?: The Complete Cosmicomics (Italo Calvino; vaguely remember reading these when I was maybe 7 and liking them, but I have forgotten their content)

2022: Free: Coming of Age at the End of History (Lea Ypi)

2021: Fairy and Folk Tales of Ireland (W.B. Yates)

Some of these are degree-related, some not; some harken back to bygone areas of interest and some persist yet; some were obtained willingly and some thrust upon me without fanfare. I think there are also some I've left at college, but I'm not sure I was actually intending to read any of them - I know one is an old copy of Structural Anthropology by Claude Levi-Strauss that Dad picked up for me secondhand, which I...don't intend to torment myself with. Reading about Tom Huffman's cognitive-structural theory of Great Zimbabwe almost finished me off and remains to date the only overdue essay I intend to never finish, mostly because the professor let me get away with abandoning it.

There are also library books, mostly dissertation-oriented, from which you can tell that the cognitive archaeologists who live in my walls finally fucking Got me:

The Rise of Homo sapiens: The Evolution of Modern Thinking (Thomas Wynn & Fred Coolidge)

The Material Origin of Numbers: Insights from the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (Karenleigh A. Overmann)

Archaeological Situations: Archaeological Theory from the Inside-Out (Gavin Lucas)

And, finally, some I've actually finished recently ("recently" being "within the past year"):

The Body Fantastic (Frank Gonzalo-Crussi, solid 6/10 essay collection about a selection of body parts, just finished earlier)

An Entertainment for Angels: Electricity in the Enlightenment (Patricia Fara, also a solid 6/10, fun read but nothing special)

Babel: An Arcane History (R.F. Kuang, 8/10, didactic (sometimes necessary) but effective; magic system was cool and a clever metaphor)

The Sign of Four (A.C. Doyle, 2/10 really racist and for what)

Dr. Space Junk vs. the Universe: Archaeology and the Future (Alice Gorman, 8/10, I love you Dr. Space Junk)

In Search of Us: Adventures in Anthropology (Lucy Moore, 8/10, I respect some of these people slightly more now)

The Dispossessed (Ursula K. Le Guin, 9/10 got my ass)

The Hound of the Baskervilles (A.C. Doyle, 7/10 themez 👍)

#if you see a book on this list that you gave me years ago. well. just know that i failed.#genuinely so much worse than i thought it was but i'm making my best effort to get through them#this is honestly just for fun because i love to list things. user professionalowl bookshelf reveal. please offer reviews if you have them#hooting

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"For we suffer from reminiscences, and every reminiscence is a wound: whether slashed across the epidermis, or hacked out by the fraying of neural pathways in the brain."

Steven Shaviro on Kathy Acker

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Images are condemned because they are bodies without souls, or forms without bodies. They are flat and insubstantial, devoid of interiority and substance, unable to express anything beyond themselves. They are—frustratingly— static and evanescent at once, too massively present in their very impalpability. The fundamental characteristic of the cinematic image is therefore said to be one of lack.[...] Images are false, since they have been separated from the real situations of which they claim to be the representations, as well as from the material conditions in which they have been produced. They are suspect, unreliable, and 'ideological,' because they presume to subsist in this state of alienation, and even perpetuate it by giving rise to delusive 'reality effects,' rituals of disavowal, and compensatory fantasies of plenitude and possession.

Steven Shaviro, The Cinematic Body

143 notes

·

View notes

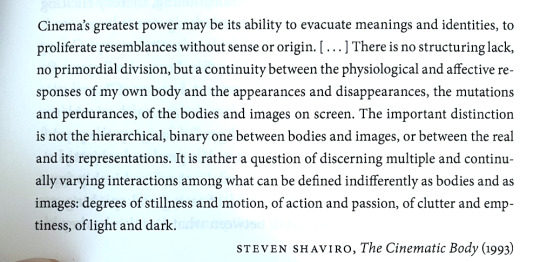

Text

[ID: Cinema’s greatest power may be its ability to evacuate meanings and identities, to proliferate resemblances without sense or origin […] there is no structuring lack, no primordial division, but a continuity between the physiological and affective responses of my own body and the appearances and disappearances, the mutations and perdurances, of the bodies and images on screen. The important distinction is not the hierarchical, binary one between bodies and images, or between the real and its representations. It is rather a question of discerning multiple and continually varying interactions among what can be defined indifferently as bodies and as images: degrees of stillness and motion, of action and passion, of clutter and emptiness, of light and dark. — Steven Shaviro, The Cinematic Body (1993) end ID]

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Vivian Sobchack compellingly argues...that electronic media 'engage [their] spectators and 'users' in a phenomenological structure of sensual and psychological experience that, in comparison with the cinematic, seems so diffused as to belong to no-body...the electronic is phenomenologically experienced not as a discrete, intentional, body-centered mediation and projection in space but rather as a simultaneous, dispersed, and insubstantial transmission across a network or web that is constituted spatially more as a materially flimsy latticework of nodal points than as a stable ground of embodied experience'

Steven Shaviro, Post-Cinematic Affect, pg. 39

#shaviro#steven shaviro#post-cinematic affect#sobchack#electronic media#phenomenology#phenomenological#cinema#cinematic#nobody#bodyless#disembodied

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The mechanically reproduced object has two lives: one as an ephemeral throw-away item, the other as a precious fetish. This also corresponds to two ways that comics are consumed by their audience. On the one hand, you need to leaf through them quickly, with what Walter Benjamin calls distracted attention: it's precisely in this suspended state that they become so strangely absorbing. On the other hand, you need to go back over them, studying every word and every panel, with a fanatical attention to detail. The letters pages of any comic book are filled with the most minutely passionate comments and observations. The letter-writers worry about inconsistencies and continuity errors, express approval or disapproval of the characters, engage in lengthy symbolic analyses, critique the artists' renderings, and make earnest suggestions for future plot directions. In this way, these books become interactive; as Marshall McLuhan was apparently the first to note, comics are "a highly participational form of expression." It's all so different from the old habits of highbrow literary culture.

Steven Shaviro, Doom Patrols

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“But what of horror’s traditional themes of struggle and survival, of rescuing the possibilities of life and community from an encounter with monstrosity and death? The Living Dead trilogy plays with these themes in a manner that defies conventional expectations. Indeed, it is this aspect of the films that has been most thoroughly discussed by sympathetic commentators, like Robin Wood and Kim Newman. All three films have white women or black men as their chief protagonists, the only characters with whom the audience positively identifies as they struggle to remain alive and to resist and escape the zombies.

The black man in Night is the sole character in the film who is both sympathetic and capable of reasoned action. The woman protagonist in Dawn rejects the subordinate role in which the three men, wrapped up in their male bonding fantasies, initially place her; she becomes more and more active and involved as the film progresses. The woman scientist in Day is established right from the start as the strongest, most dedicated, and most perspicacious of the besieged humans. In both Dawn and Day, the women end up establishing tactical alliances with black men who are not blindly self-centered in the manner of their white counterparts.

All these characters are thoughtful, resourceful, and tenacious; they are not always right, but they continually debate possible courses of action and learn from their mistakes. They seem to be groping toward a shared, democratic kind of decision making. In contrast, white American males come off badly in all three films. The father in Night considers it his inherent right to be in control, although he clearly lacks any sense of how to proceed; his behavior is an irritating combination of hysteria and spite.

The two white men among the group in Dawn both die as a result of their adolescent need to indulge in macho games or to play the hero. The military commanding officer in Day is the most obnoxious of all: he is so sexist, authoritarian, cold-blooded, vicious, and contemptuous of others that the audience celebrates when the zombies finally disembowel and devour him. These white males’ fear of the zombies seems indistinguishable from the dread and hatred they display toward women. The self-congratulatory attitudes that they continually project are shown to be ineffective at best, and radically counterproductive at worst, in dealing with the actual perils that the zombies represent.

The macho, paternalistic traits of typical Hollywood action heroes are repeatedly exposed as stupid and dysfunctional. Romero dismantles dominant behavior patterns; he gives a subversive, left-wing twist to the usually reactionary ideology and genre of survivalism. To the extent that the films maintain traditional forms of narrative identification, they divert these forms by providing them with a new, politically more progressive content. Carol J. Clover argues that slasher and rape–revenge films of the 1970s and 1980s enact a shift in the gender identification of traditional attributes of heroism and struggle, whereby women take on these attributes instead of men.

Dawn and Day present us with a more self-conscious, radical, and thoroughgoing version of the same shift in cultural sensibilities. But the scope of Clover’s argument is limited by the fact that it too easily valorizes heroic triumph. In Romero’s trilogy, to the contrary, the success of the sympathetic characters’ survival strategy is limited; it does not, and cannot be expected to, resolve all the tensions raised in the course of the three films. Unlike in the slasher and revenge films described by Clover, here the protagonists’ survival is not the same as their triumph.

The zombies are never defeated; the best that the sympathetic living characters of Dawn and Day can hope for is the reprieve of a precarious, provisional escape. And this tenuousness leads us back to the zombies. The Living Dead trilogy does not simply or unequivocally valorize survival; perhaps for that reason, it ultimately does not rely for its effectiveness on mechanisms or spectatorial identification. The zombies exercise too strong a pull, too strange a fascination. The three films progress in the direction of ever-greater contiguities and similarities between the living and the nonliving, between seduction and horror, and between desire and dread.

In consequence, identities and identifications are increasingly dissolved, even within the framework of conventional, ostensibly sutured narrative. The first film in the series, Night of the Living Dead, is the one most susceptible to conventional psychoanalytic interpretation, for it is focused on the nuclear family. It begins with a neurotic brother and sister quarreling as they pay a visit to their father’s grave and moves on to the triangle of blustering father, cringing mother, and (implicitly) abused child hiding from the zombies in a farmhouse basement.

Familial relations are shown throughout to be suffused with an anxious negativity, a menacing aura of tension and repressed violence. In this context, the zombies seem a logical outgrowth of, or response to, patriarchal norms. They are the disavowed residues of the ego-producing mechanisms of internalization and identification. They figure the infinite emptiness of desire, insofar as it is shaped by, and made conterminous with, Oedipal repression. The film’s high point of shock comes, appropriately, when the little girl, turned into a zombie, cannibalistically consumes her parents.

But at the same time, the film’s casual ironies undercut this allegory of the return of the repressed. The protagonists not only experience the zombie menace firsthand, they also watch it on TV. Disaster is consumed as a cheesy spectacle, complete with incompetent reporting, useless information bulletins, and inane attempts at commentary. The grotesque, carnivalesque slapstick of these sequences mocks survivalist oppositions. Even as dread pulses to a climax, as plans of action and escape fail, and as characters we expect to survive are eliminated, we are denied the opportunity of imposing redemptive or compensatory meanings.

There is no mythology of doomed, heroic resistance, no exalted sense of pure, apocalyptic negativity. The zombies’ lack of charisma seems to drain all the surrounding circumstances of their nobility. And for its part, the family is subsumed within a larger network of social control, one as noteworthy for its stupidity as for its exploitativeness. Romero turns the constraints of his low budget—crudeness of presentation, minimal acting, and tacky special effects—into a powerful means of expression: he foregrounds and hyperbolizes these aspects of his production in order to depsychologize the drama and emphasize the artificiality and gruesome arbitrariness of spectacle.

Such a strategy doesn’t “alienate” us from the film so much as it insidiously displaces our attention. Our anxieties are focused upon events rather than characters, upon the violent fragmentation of cinematic process (with a deliberate clumsiness that mimes the shuffling movement of the zombies themselves) rather than the supposed integrity of any single protagonist’s subjectivity. The zombies come to exemplify, not a hidden structure of individual anxiety and guilt, but an unabashedly overt social process in which the disintegration of all communal bonds goes hand in hand with the callous manipulation of individual response.

It is entirely to the point that Night ends on a note of utter cynicism: the zombies are apparently defeated, but the one human survivor with whom we have identified throughout the film—a black man—is mistaken for a zombie and shot by an (implicitly racist) sheriff’s posse. The other films in the cycle are made with higher budgets and have a much slicker look to them, but they are even more powerfully disruptive. The second film, Dawn of the Dead, deals with consumerism rather than familial tensions. The zombies are irresistibly attracted to a suburban shopping mall, because they dimly remember that “this was an important place in their lives.”

Indeed, they seem most fully human when they are wandering the aisles and escalators of the mall like dazed but ecstatic shoppers. But the same can be said for the film’s living characters. The four protagonists hole up in the mall and try to re-create a sense of “home” there. Much of the film is taken up by what is in effect their delirious shopping spree: after turning on the background music and letting the fountains run, they race through the corridors, ransacking goods that remain sitting in perfect order on store shelves.

Once they have eliminated the zombies from the mall, they play games of makeup, acting out the roles of elegance and wealth (and the attendant stereotypes of gender, class, and race) that they dreamed of, but weren’t able actually to afford, in their previous middle-class lives. This consumers’ utopia comes to an end only when the mall is invaded by a vicious motorcycle gang: a bunch of toughs motivated by a kind of class resentment, a desire to “share the wealth” by grabbing as much of it as possible.

They enter by force and then pillage and destroy, enacting yet another mode of commodity consumption run wild. One befuddled gang member can’t quite decide whether to run off with an expensive TV set or smash it to bits in frustration over the fact that no programs are being broadcast anymore. The still alive and the already dead are alike animated by a mimetic urge that causes them to resemble Dawn’s third category of humanoid figures: department store mannequins.

The zombies are overtly presented as simulacral doubles (equivalents rather than opposites) of living humans; their destructive consumption of flesh—gleefully displayed to the audience by means of lurid special effects—immediately parallels the consumption of useless commodities by the American middle class. Commodity fetishism is a mode of desire that is not grounded in repression; rather, it is directly incited, multiplied, and affirmed by artificial means.

As Meaghan Morris remarks, “a Deleuzian account of productive desire . . . is more apt for analyzing the forms of modern greed . . . than the lack-based model assumed by psychoanalytic theories.” Want is a function of excess and extravagance, and not of deficiency: the more I consume, the more I demand to consume. In the words of the artist Barbara Kruger, “I shop, therefore I am.” The appearance of the living dead in the shopping mall thus can no longer be interpreted as a return of the repressed. The zombies are not an exception to, but a positive expression of, consumerist desire.

They emerge not from the dark, disavowed underside of suburban life but from its tacky, glittering surfaces. They embody and mimetically reproduce those very aspects of contemporary American life that are openly celebrated by the media. The one crucial difference is that the living dead—in contrast to the actually alive—are ultimately not susceptible to advertising suggestions. Their random wandering might seem to belie, but actually serves, a frightening singleness of purpose: their unquenchable craving to consume living flesh.

They cannot be controlled, for they are already animated far too directly and unconditionally by the very forces that modern advertising seeks to appropriate, channel, and exploit for its own ends. The infinite, insatiable hunger of the living dead is the complement of their openness to sympathetic participation, their compulsive, unregulated mimetic drive, and their limitless capacity for reiterated shock. The zombies mark the dead end or zero degree of capitalism’s logic of endless consumption and ever-expanding accumulation, precisely because they embody this logic so literally and to such excess.

In the third and most complex film of the series, Day of the Dead, Romero goes still further. A shot near the beginning shows dollar bills being blown about randomly in the wind: a sign that even commodity fetishism has collapsed as an animating structure of desire. The locale shifts to an isolated underground bunker, where research scientists endeavor to study the zombies under the protection of a platoon of soldiers.

All human activity is now as vacant and meaningless as is the zombies’ endless shuffling about; the soldiers’ abusive, macho posturings and empty assertions of authority clash with the scientists’ futile, misguided efforts to discover the cause of the zombie plague and to devise remedies for it. All that remains of postmodern society is the military–scientific complex, its chief mechanism for producing power and knowledge. But the technological infrastructure is now reduced to its most basic expression, locked into a subterranean compound of sterile cubicles, winding corridors, and featureless caverns.

Everything in this hellish, underground realm of the living is embattled, restricted, claustrophobically closed off. This microcosm of our culture’s dominant rationality tears itself apart as we watch: it teeters on the brink of implosion, destroying itself from within even as it is literally under siege from without. The bunker is like an emotional pressure cooker: fear, fatigue, and anxiety all mount relentlessly, for they cannot find any means of relief or discharge. As the film progresses, tensions grow between the soldiers and the scientists, between the men and the one woman, and ultimately among the irreconcilable imperatives of power, comprehension, survival, and escape.

The entire film is a maze of false exits and dead ends, with the zombies themselves providing the only prospect of an outlet. Day of the Dead is primarily concerned with the politics of insides and outsides: the social production of boundaries, limits, and compartmentalizations, and their subsequent affirmative disruption. The zombies, on the outside, paradoxically manifest a “vitality” that is lacking within the bunker. Their inarticulate moans and cries, heard in the background throughout the film, give voice to a force of desire that is at once nourished and denied, solicited and repulsed, by the military–scientific machine.

Inside the bunker, in a sequence that works as a hilarious send-up of both behaviorist disciplinary procedures and 1950s “mad scientist” movies, a researcher tries to “tame” one of the zombies. The dead, he explains, can be “tricked” into obedience, just as we were tricked as children. He eventually turns his pet zombie, Bub, into a pretty good parody of a soldier, miming actions such as reading, shaving, and answering the telephone, and actually capable of saluting and of firing a gun.

This success suggests that discipline and training, whether in child rearing or in the military, is itself only a restrictive appropriation of the zombies’ mimetic energy. Meanwhile, the zombies mill about outside in increasing numbers, waiting with menacing passivity to break in. From both inside and outside, mimetic resemblances proliferate and threaten to overturn the hierarchy of living and dead. The more rigidly boundaries are drawn between reason and desire, order and anarchy, purpose and randomness, the more irrelevant these distinctions seem, and the more they are prone to violent explosion.

The climax occurs when one of the soldiers—badly wounded (literally dismembered, metaphorically castrated), and motivated by an ambiguous combination of heroic desperation and vicious masculine resentment—opens the gates and lets the zombies into the bunker, offering his own body as the first sacrifice to their voracity. The controlling boundary is ruptured, and the outside ecstatically consumes the inside. Allegory entirely gives way before a wave of contagious expenditure and destruction.

The zombies take their revenge; but, as Kim Newman notes, “American society is cast in the role usually given to an individually hatable character.” If the zombies are a repressed byproduct of dominant American culture in Night, and that culture’s simulacral double in Dawn, then in Day, they finally emerge—ironically enough—as its animating source, its revolutionary avenger, and its sole hope of renewal. They are the long-accumulated stock of energy and desire upon which our militarized and technocratic culture vampiristically feeds, which it compulsively manipulates and exploits but cannot forever hope to control.”

- Steven Shaviro, “Contagious Allegories: George Romero.” in Zombie Theory: A Reader

6 notes

·

View notes