Text

“How should I help an autistic person who’s having a meltdown?”

This is a question that hundreds of people asked after my latest Twitter thread about Sia’s movie, where the autistic character is restrained in prone position while having a meltdown.

That post explains why & how prone restraint is dangerous and traumatic. But a lot of people were wondering what should be done to help an autistic person during a meltdown. What are the alternatives to restraint? What would I recommend, as someone who’s had countless severe meltdowns myself?

I generally advise against trying to assist with a meltdown unless you know the person. If they’re totally by themselves, then it’s a judgement call. But more often than not, the person will already have someone with them who can help. Additionally, having a stranger approach during a meltdown has a high chance of making the situation even more stressful for the autistic person. So only approach the person in this circumstance if you think it’s absolutely necessary and would definitely help. For example, if the person was lost and needed assistance getting back to a familiar location.

Okay, so, what do you do if assisting the person is the right role for you to take?

The first step when assisting with any meltdown, is to minimize sensory input and ensure physical safety. Meltdowns are the result of overstimulation, so it’s important to try and reduce the amount of external factors that could be causing overwhelm. It’s also important to ensure that the person is not in immediate danger. Often, solving for those two things will involve changing location.

This is complicated, and if a meltdown is already underway it might be impossible to change locations safely. Even if you do change locations, the meltdown has already started so it’s not just going to stop immediately. So, here are some suggestions for direct support to the person. All of this depends on the environment, the tools available, and your relationship to the person having the meltdown. Use your critical thinking skills to consider different types of responses in different scenarios.

If the person can’t speak: assess what communication methods they can use, and what kind of communication is necessary. If you need to collaborate with the person to find solutions (particularly if you’re in a public place), using an AAC app, a picture-based communication system, pen and paper, or sign language will probably be your best bet. If the person can’t access those things but is still able to nod & shake their head, make sure that any questions you ask are yes or no questions. If you ask something like “Do you want to stay or leave?” they won’t be able to respond. Instead say, “Do you want to stay?” and then if that answer isn’t clear, “Do you want to leave?”

If the person is in a loud or chaotic environment: try to remove them as soon as possible. If they stay in that situation, the meltdown will probably get worse. Sometimes it can be hard for autistic people to move on our own when we’re in a meltdown. We tend to get stuck. So having someone lead us elsewhere can be extremely helpful in a circumstance where we’re too overwhelmed to move ourselves or even know where to go.

If the person has comfort items: try to make sure they have access to them. Blankets, pillows, stuffed animals, water bottles, chewies, stim toys, etc. can all help comfort an autistic person who’s having a meltdown. Some of us have favorite items that we carry with us everywhere. Make sure we have those with us (assuming the items aren’t lost; and if they are lost, help us find them).

If the person is injuring themselves or others: the first step is to try and find replacements for those actions, that meet the same sensory need. If someone is biting themselves, try to find something else for them to bite into. Many autistic people have chewies and other stim toys that can help us in this type of situation. If we don’t have one with us, sometimes other kinds of strong sensory input can work as well. Something that has worked for me in the past, to keep me from biting or hitting myself, is to put something frozen on my lips or in my mouth. The cold is strong and provides a very similar sense of relief.

Many autistic people, myself included, find it beneficial to be hugged tightly and to have our hands or arms squeezed by someone else. But this really depends on the person and their sensory profile, as well as your relationship to the person. Some autistic people hate being touched during meltdowns. So you have to be aware of the individual and their specific needs.

The ONLY circumstance in which a person should be restrained, is if they are at imminent risk of causing injury to themselves or others. Noncompliance, angry speech, etc. are NOT a valid reason to restrain someone. And the typical kinds of restraint used on autistic people are actually quite dangerous. Prone restraint, for example, can be deadly. The only kind of restraint I’ve had used on me that was physically comfortable and felt safe, was when my mom sat behind me and put her legs over mine (leaving some space so that I could still bend my knees a little bit), and hugged me from behind so that my upper arms were against my sides but my hands & wrists weren’t being held and could still move.

I’ve been restrained in a basket hold and in prone position, and both of those positions were extremely painful and traumatic to me. There are probably forms of restraint similar to the one I described that would work but are not harmful and that don’t run the risk of injuring the person. The key I think is to have the person sitting upright, and to restrict the movement of their limbs without putting any pressure on their torso or running the risk of bending/stretching their limbs too far. And again, only do this if it’s absolutely necessary and all other options have been exhausted.

If the person is stimming, making loud noises, sobbing, screaming, and so on: Do not restrain the person, try to stop them from stimming, or try to stop them from making noise. As long as they’re physically safe, this needs to be allowed because it’s the only way for the energy of the meltdown to be released. If they’re screaming and it hurts your ears, put in earplugs to meet your own sensory needs. The truth is that there’s almost always nothing you can do to stop this aspect of a meltdown. All you can do is provide sensory tools, move the person to a safer and quieter location, and wait for it to pass.

Now, here are some reminders about meltdowns:

They are neurological events that are beyond the person’s control

Becoming angry at a person who’s having a meltdown will not help

Meltdowns are caused by a buildup of overwhelming stimuli, not just one tiny thing

They can be triggered more easily if the person is hungry or has low blood sugar (so if a person is getting cranky or seems like they might enter a meltdown, try to get them to eat something)

Every autistic person is different, which means that all of our meltdowns look different and all of us need different things when we’re being helped

You should talk to your autistic friends or relatives about how to help them during a meltdown when they’re in a calm and regulated state. If you can’t talk to the person, you can ask their caregivers what things tend to help the most

Meltdowns often require a period of recovery and after-care. Make sure that the person is safe and comfortable as they recover

While there are lots of things you can do to mitigate the chances of a meltdown happening, sometimes they just can’t be prevented. That’s okay, and it’s something you can prepare for

Communication is key when caring for someone who’s having a meltdown. Let them know what you’re doing and why, ask simple questions when needed, and listen when they communicate with you

What works during one meltdown might not work during the next one. Try to be flexible and ready to adapt as needed, because every situation is different

It’s okay if you don’t get everything right. Situations like these are stressful and hard for everyone involved, so don’t worry about doing things perfectly. All that matters is that you’re trying your best

This is all I have to say for now, but there’s a lot that I’m forgetting about or just haven’t included because it would make the post too long.

If you have any questions about autism that you want answered quickly and you’re willing to pay me a small amount (starting at $3) via Venmo or PayPal, you can email your questions to me at [email protected] and I’ll get back to you with a detailed answer (and payment information) as soon as possible. This is something I’m starting as I expand the consulting side of my advocacy work. Thank you for your support!

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#ableism#autism acceptance#autism awareness#autismacceptance#autism meltdown#neurodivergent

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Autism in Relationships: an interview with Abby about dating me as an autistic person. (Part 2)

Yesterday I posted part one of this interview with my girlfriend, so you can check that out first if you haven’t read it yet. The aim here is to give people insight on what it can be like when autistic people enter close relationships. So, here’s part 2!

Eden: What are some of your favorite things about the way my autism affects our relationship and the way we interact?

Abby: I don’t think I’ve ever been in a relationship with someone who isn’t neurodivergent, so in general I would say that autism/ADHD makes a relationship good for me because I can be myself around the other person. I know they won’t judge me for doing something “weird,” because... they’re weird too! That understanding makes autistic relationships much more comfortable for me.

Of course, everyone’s autism is different. My favorite things about you are that you are so easygoing and “uncarved” [from the Daoist concept of Pu; uncarved wood]. You’re very innocent and unbothered by society. I also like that you are able to understand sarcasm, which a lot of autistic people struggle with. I’m sarcastic a LOT, and although I would absolutely adjust my behavior if you didn’t understand it, it’s still a nice bonus. It’s also a nice bonus that our special interests align. I like nature/biology and social justice, and you like social justice and nature.

Eden: What are some of your favorite aspects of my autism and how it affects my personality & behavior? (including tiny quirks)

Abby: Again, I like your uncarved-ness and how your autism lets you see past ridiculous societal standards. I don’t live up to a lot of those so that’s super cool. I also like how that quality allows you to experience joy in things that other people might not, specifically in natural details, like milkweed fluff. That is something I love to relate to and partake in. On a related note, I love how strongly your autism makes you appreciate and care about things such as nature, or social movements like the fight against climate change, or me! :) Like Greta says, autism is definitely a superpower in that area, and you definitely have it.

Your autism also helps with your creativity, and since I’m an artist, I can definitely admire that. You have a creative and critical mind, and I love sharing ideas with you. I also love when you share ideas, since you’re so clear and informative. You are a great teacher.

In terms of little quirks, I like your stimming and your cute stimmy laugh. That especially makes me happy since it’s a laugh you only do when you think something is really fantastic. It’s also really funny when you get orange juice for every meal, even if it’s something that definitely doesn’t go with orange juice (like cheesecake). I also like when we impulse buy sweets because of our ADHD.

Eden: Romantic relationships can involve a lot of new experiences. How have you helped me feel comfortable when I get anxious about not knowing what to expect?

Abby: Most of your new experiences are physical ones, since your last relationship was a long time ago and you didn’t have much of a chance to explore physicality. I’ve been in relationships before and have plenty of experience with that, so what I do is generally outline what will happen and always ask before doing something. For instance, when we first kissed, you were like “????!!??,” so I described in (very awkward) detail what I was going to do. I literally gave you a schedule, and that helped you know what to expect. It was important to me that you were the one initiating: even if I was the one suggesting an action, I wanted you to be the one who actually did it first, so I could be completely sure that you were okay with it. I also asked before doing anything new or weird. My general advice is “make new experiences less scary and new by giving a rundown of what will happen.”

Eden: I’m pretty much always moving, and I stim more obviously than you. What are your favorite stims of mine?

Abby: I think the mothman stim is super cute, where you put your hand in front of your mouth and wiggle your fingers. I like when you jump all over the place and do full body stims but I sometimes worry that you’re going to smack something, or me lol. I also like when you laugh and shake your head like a wet dog. And I like the “fiddling with rings” stim because it looks similar to my “picking at nails” stim, and that feels like a special stimmy bond.

Eden: Do you have any advice for people who are friends or romantic partners to autistic people? What do you think are the most important things for them to know?

Abby: Given that many people who are dating an autistic person are also autistic or neurodivergent, a lot of it will be instinctual. So like, go with your gut. (And to add onto that, if you’re dating someone that’s autistic and you’re “neurotypical” I would definitely second guess that and ask yourself why neurotypical is the default. You might learn something insightful and super fun about yourself!).

Remember to set boundaries, as in all relationships, and also remember that your needs are just as important as your partner’s, even when they conflict. For instance, sometimes Eden’s vocal stimming can put me on edge, so to compromise, I might put in earplugs, or redirect their stimming into something physical. Or, sometimes we would make plans and I’d forget about them and freak out when Eden reminded me because it was “unexpected plans,” but then if we canceled, Eden’s autism would be weirded out because of “changing plans.” We would talk and see what each of us can concede, and make a new plan together. Sometimes I would think I was being a bad partner or “suppressing Eden’s autism” if a situation like that arose–that is just not true.

It’s inevitable that needs will conflict and it’s important to respect both people equally. I KNOW a lot of y’all have poor self esteem from being an afterthought in a NT-centered society (cause I do), so don’t forget to value yourself as much as you value your partner or friend. In addition, people in an autistic relationship really cannot measure their bond by neurotypical standards. A simple friendship with an autistic person may include a lot of cuddling and holding hands. A romantic partnership may not include much of that at all, depending on someone’s sensory needs. Eden and I hit a lot of “relationship milestones” in like a month that a lot of neurotypicals don’t hit for years. So, a relationship is not “better” if it does align with a neurotypical one, and it’s not “worse” if it doesn’t. All autistic relationships are beautiful as long as they are healthy. <3 <3 <3

In conclusion, autistic people are so full of love and compassion, and if you decide to be in a relationship, it can be really great! Autistic love is not destined to fail, it’s not harder than any other relationship, and it can absolutely be a wonderful and loving experience.

...

Let us know in the comments or via DM if there are any other questions you’d like us to answer. Abby and I may do a Q&A sometime in the next few months, so if you have anything to ask please do. Thanks for reading!

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#autism acceptance#autism awareness#autismacceptance#autistic culture#autism in relationships#autism and adhd#autism and dating#lesbian relationship

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Autism in Relationships: an interview with Abby about dating me as an autistic person. (Part 1)

A few days ago I asked our followers what topics they’d like to see discussed more, and several people asked for more content about autism and relationships. So, I decided to interview my girlfriend. Here’s part 1 of that interview:

Eden: When we’re out in public, what are some of the most common challenges we face related to my autism? What are the ways you assist me?

Abby: A lot of the problems we face tend to be with loud noises or unexpected plans. A loud bus or motorcycle can be disruptive, and since you have forearm crutches for your EDS [Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome], you can’t cover your ears. So, I do that for you. Sometimes, I’ll do certain tasks for you like ordering food, or asking people for help. You actually tend to be pretty good with changes in plans, better than I am, but I try to tell you what we’re doing at least a day before. And I’m always looking for places for you to sit [because of EDS].

Eden: How has dating me impacted your view of your own autism?

Abby: Prior to meeting you, I was kind of sure I was autistic, and saw it as mostly a good thing. Like, I definitely didn’t see it as a disease or anything. However, since meeting you I’ve learned so much about autism, ADHD, EDS, etc. There are so many things about myself that were just confusing for so many years, and you explain every single one. This understanding has helped me unmask a lot, which makes me feel much more comfortable and happy! I often feel like a lot of your followers do--validated and even celebrated.

Eden: I generally have higher support needs than you do, but you face your own autism-related challenges as well. What are some of the ways I help you in situations where you’re having a harder time than I am?

Abby: You’re much more literate about autism and what exactly goes on in the brain. Most of my help is instinctual, but you’ve actually read up on this stuff, which helps a lot when I’m facing a crisis. You can help explain or rationalize why I might be feeling a certain way, which is validating.

A lot of what I struggled with before I learned about neurodivergence was thinking that I wasn’t as good as someone else. For instance, I would beat myself up over not studying, or putting off a project, but now I know that’s just ADHD. And you remind me of that often.

I also prefer not speaking when I’m experiencing a lot of emotion at once, and the way you accept that and give me resources to communicate alternatively helps a lot. However, usually when we’re in a situation where I might experience an autism-related challenge, you are too, so the “Eden protection mode” adrenaline helps me overcome a lot of potential autistic problems.

Eden: Would you mind explaining how you approach things when I have a shutdown or meltdown? (Like what your strategies are to help me calm down, how you speak to me, etc.)

Abby: First, if I’m not with you, I get information on where you are and what resources you might have. I ask you to identify what is causing the problem (loud noise, fear, stress from school etc). Yes or no questions are sometimes good, but often you can type reasonably well even if you’re not speaking. I’ll give you an impetus to get yourself out of the situation, usually specific instructions like “get a chewy and something to dig your nails into if you need it,” or “go outside and get some fresh air.” A lot of the time, you’re too overwhelmed to find your own way out, so to speak, so I’ll suggest actions or objects that you can use.

If I’m by your side, I’ll get you out of the situation asap, usually holding your hand or arm so ground you. I’ll find the closest quiet spot and hug you really tight, and try and provide something for you to stim with, like a bracelet. I’ll ask yes or no questions, because usually at this point you’re nonverbal. Asking about or verbalizing every action is helpful, so you know what to expect next. Sometimes we use the one-way texting app thing [EmergencyChat]. After a while, when you’ve calmed down somewhat, I can start talking to you and making jokes to take your mind off whatever just happened. Then we are A-Ok.

Basically, it takes a lot of resourcefulness and quick thinking, but whenever you’re in danger, my body goes into “protect Eden mode” and it does that on its own. Thanks ADHD! I also hold you a lot, but for some autistic people that won’t fly, so I would ask if touching is okay. Also for some reason, me having a shutdown can take you out of one, but I don’t recommend trying this at home. That’s always done on a closed course with professional drivers.

Eden: Would you mind describing our general communication style, and how it helps us make sure we’re both understanding each other?

Abby: Pretty much we just vibe? We don’t have that many miscommunications, and if we do it’s usually something funny like the vacuum thing [caused by taking things literally]. At this point, I can kind of anticipate what you might get stuck on, but if I don’t clarify, you just ask. We are very straightforward and blunt. In terms of body language, it usually lines up with what you’re verbally saying, so I don’t need to pay that much attention to it unless you’re nonverbal. There aren’t ever any subliminal messages in anything either of us say, so that is a nice precedent to just know.

Eden: What are some of the ways you balance meeting your own needs with meeting mine?

Abby: Most of the time, our needs line up. Usually if you’re overwhelmed and need to take a break, so do I. And occasional shutdowns are just that--occasional. I can handle those. And as for smaller things, that’s not a drain at all. If there’s a food you don’t like, I’ll just eat it. If there’s a loud noise, I’ll cover your ears. However, I do sometimes need space, which I’ll usually simply ask for.

We both respect my boundaries a lot, since I do seem to get socially drained faster than you do. For instance, if I were feeling drained, I would ask to meet for dinner tomorrow instead of tonight. In addition, you’ve probably handled as many of my shutdowns as I’ve handled yours. They also tend to be more difficult to deal with, since they’re often brought on by emotional problems (like anxiety about calculus bleh) rather than immediate sensory problems. You can’t really be like “here have some headphones” and make it go away. But the give and take of emotional support is a balance as a whole.

...

This concludes part one of the interview :)

The aim here was to give y’all a glimpse into what life can be like when autistic people enter romantic relationships. Whether you’re an autistic person in a relationship, a nonautistic person who’s dating an autistic person, or a friend to an autistic person, I hope that this gave you some insights that you can put to use in your own life.

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#autism acceptance#autism awareness#autismacceptance#lesbian#autism in relationships

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

An examination of Yale’s defensive statement, released after public outcry over their study on autistic toddlers.

On December 6th, 2020, a study conducted by three researchers from Yale University’s Child Study Center was published in the Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research. It’s called “Attend Less, Fear More: Elevated Distress to Social Threat in Toddlers With Autism Spectrum Disorder.” (https://europepmc.org/article/med/33283976) It is a peer-reviewed study, and it was approved by Yale’s Institutional Review Board.

The goal of the study was to measure autistic toddlers’ fear responses, in order to compare their emotional reactivity to that of neurotypical toddlers. The idea was that this could give some insight into how anxiety and depression develop in autistic people later in life. That’s a decent goal, but those insights could have been sought in much better ways, and without conflating autism with mood disorders (suggesting that autism itself requires treatment, as the authors of this study did).

As it was, the authors ended up conducting a study in which toddlers (42 autistic and 22 neurotypical) endured 10 trials of frightening stimuli to measure their fear responses. The methodology was based on the Lab-TAB - Locomotor Version, which is a standardized method of measuring the general temperament of young children.

In other studies (1, 2) that use some variation of Lab-TAB techniques, the stimuli used to induce fear include a mechanical toy dog, and a toy robot. In those studies, none of the fear-inducing stimuli were introduced for more than three trials, and the durations of those trials were significantly shorter (15 seconds and ~10-30 seconds respectively, compared to 60 seconds in the Yale study). In the Yale study, not only did the toddlers endure 10 trials each, but the stimuli used were much more frightening.

From Yale’s study:

“The Stranger probe involved a female stranger wearing dark clothing, a hat, and sunglasses entering the room, approaching the child, and leaning toward the child for approximately 3 s (one trial). The Objects condition included Spider (large mechanical spider crawling toward the child, three trials) and Dinosaur (mechanical dinosaur with red light-up eyes approaching the child, three trials). Masks involved a female stranger dressed in dark clothes and wearing three grotesque masks in succession (e.g. vampire, Star Wars character) entering the room briefly and maintaining an approximate 1.5-m distance from the child (three trials).”

“Each probe lasted approximately 60 s with the effective exposure to threat time of approximately 30 s. Breaks were instituted between each probe, with a minimum of 30 s and an average of 75 s (SD = 36 s) needed to ensure that the child’s affect returned to neutral before proceeding to the next probe.”

So, ten trials. Assuming that “trial” means “repetition of the probe,” each one lasted around 60 seconds. Since 60 seconds is one minute, that’s ten minutes of exposure to threat; five minutes if we’re being conservative and going with their estimation of 30 seconds of effective exposure. There was an average of 75 seconds between each trial, however. So that’s 9x75, which adds 675 more seconds to the total time of the experiment. 675 seconds is 11.25 minutes. Add that to the previously calculated ten minutes, and that brings the total time of the experiment to around twenty-one minutes.

All of this is in contrast to what the authors wrote in their defensive statement (https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/29344/):

Let’s pick apart each aspect of this paragraph.

1. “The events used to elicit emotional responses were very brief [and] had low intensity.”

Based on my calculations, the combined amount of time that the kids were exposed to the events was 5 to 10 minutes. That’s not brief compared to other studies measuring similar things. And surely a large mechanical spider, a dinosaur with red eyes, and a vampire are much more intense stimuli than a mechanical dog?

2. “[The events] were interspersed with playtime, and mirrored what the children might encounter in the real world. For example, a Halloween costume or a new mechanical toy.”

There is absolutely NO mention of playtime anywhere in this paper. Nothing. Not a word about it. The only thing that could be potentially be seen as playtime is the 30 to 75 seconds between trials. But really? There’s not even a mention of the kids being given toys between trials. All the study says is that they waited for the toddlers’ demeanor to become neutral again.

As for the “Halloween costume” and “mechanical toy” euphemisms here: the study literally says “grotesque masks.” Grotesque. And “toy” sure is an interesting way to say “large mechanical spider crawling toward the child.” We don’t have photographs of the masks or toys used in this study, but from the way they were described in the paper itself, the words “Halloween” and “toy” put a much too positive spin on things.

3. “The entire task reported on in the paper lasted approximately two minutes with several additional minutes for breaks and transitions.”

This is the part that baffles me. Anyone can look at the paper and see where they wrote that each probe lasted for 60 seconds, and that there were 10 trials. Even if there had only been one 60-second trial of each probe, that still would have been 4 minutes (for the 4 probes), not 2 minutes.

What they might be doing here is only counting “effective exposure to threat” (30 seconds), and then multiplying that by 4 for each probe. That would be 2 minutes. But if that’s true, they’ve still failed to explicitly state how long each trial of each probe was. Because there were 10 trials, not 4. And why would a trial of the Stranger probe last 60 seconds, while a trial of the other probes would only last 20 seconds? (60 seconds divided by 3 trials). The math works out, yes. But if that’s the case, this is an issue that should have been more clearly addressed in the paper itself. Clarification on what’s meant by the terms “probe” and “trial,” in addition to information on the duration of each trial, should have been established. And, “effective exposure to threat time for each probe” (a subjective measure to begin with) is not even close to what’s implied by the phrase “the entire task.”

Here’s the last bit I want to touch on:

There is no mention of physiological responses in this study. According to what they wrote in the paper, the authors observed external behavior, not internal bodily changes. The toddlers were not hooked up to any sort of technology that would have measured their heart rate, breathing, etc.

And perhaps the mildly distressed children had an easy time calming down. But what about the trials that had to be terminated and excluded from the results due to “the child’s negative affect” or “parental noncompliance (i.e. parent interfering with probe administration)”? If they literally had to end trials because the kids were so upset, or the parents intervened to comfort their children, then how is it possible to say that “none” of the children experienced extreme negative emotions?

Yale’s statement is full of holes, and creates more questions than it answers. The autistic community is calling for full transparency on the methods used, an explanation of the reasons behind those choices, and detailed answers to our questions about the ethical legitimacy of what happened. Inquiries about the study should be directed to the authors at these two email addresses: [email protected], and [email protected].

Thank you for reading.

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#ableism#autism acceptance#autism awareness#aba therapy#yale#Yale autism study#attend more fear less

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

The impersonation of disabled people for personal gain is a serious problem that needs to be addressed.

I am writing this post in lieu of two events: my witnessing of an interaction between a student who was faking a service dog and a university employee; and the release of Sia’s trailer for the film “Music.”

Those events may seem disconnected at first, as they did to me. But as I thought more deeply about both situations, something big stood out to me: in both cases, a nondisabled person was temporarily assuming the identity of a disabled person in order to generate some form of personal gain or profit.

I’ll go over the “service dog” interaction first, because it’s a story I haven’t told yet. Basically, last Tuesday I went into the Covid testing center on UVM’s campus. In line ahead of me was a fellow student who had a small lap dog on a leash. The dog was barking, yapping, running around, and jumping on the legs of workers at the testing center. It was incredibly disruptive, and honestly very irritating, especially since the student wasn’t doing anything to try and correct the dog’s behavior.

Nobody said anything to the student at first (the worker whose legs the dog jumped on didn’t even react), so I considered the possibility that pets were allowed in the building. The dog was so clearly not a service animal (bad behavior, lack of other identifying markers) that it just didn’t seem possible that people could notice and still do nothing to reprimand the student, if pets weren’t allowed in the building. But apparently someone eventually noticed, and called over an employee.

This was the conversation I observed between the student and the employee:

Employee: unless your dog is a service dog, it’s not allowed in the building. We don’t allow pets.

Student: oh I’m leaving anyway, so don’t worry about it.

Employee: okay but I’m just letting you know for future reference that unless your dog is like, a registered service dog, it’s not allowed in the building.

Student: she’s in training, does that count?

Employee: I don’t know the rules about being in training, I would have to ask, but-

Student: she’s also a registered therapy dog, if that helps.

Employee: I don’t know, I think it’s just service dogs but I’d have to check.

At this point in the conversation, I left the building. There were so many things wrong with this interaction, and there was so much ignorance on both sides, that I couldn’t handle it. I thought about going up to educate both of them, but that prospect was too overwhelming. I was obviously disabled at that moment, because I was using my forearm crutches. That made what I witnessed even more painful. This student felt comfortable impersonating someone like me, right in front of me.

And for those who aren’t aware of the laws around service dogs, here are all of the things that were wrong with that conversation:

1. In the United States, there is no such thing as a federal registry for service dogs. Organizations that claim to provide registration papers are fraudulent. So the employee was wrong to say that a service dog would have to be “registered.”

2. Legitimate service dogs (in training or not) can legally be kicked out of establishments if their behavior is disruptive (as this dog’s behavior was- barking and jumping on people), so the employee could have just told her to leave point blank.

3. Service dogs in training have full public access rights, but therapy dogs do not. An actual service dog handler would be aware of these laws and would not ask an employee questions about if they were allowed in the building or not. Additionally, this dog was clearly not being “trained” by the student in any way.

So from every available external indicator, this student was flustered when confronted about bringing her pet dog into the building, and therefore decided to pretend that she was disabled & had a service dog “in training.” The student benefited personally from implicitly lying about being disabled; avoiding the potential consequences of her actions by exploiting the ignorance and good nature of the employee.

Because disability is more fluid and often less obvious than other characteristics like skin color, body size, etc. it is easier for nondisabled people to impersonate us when it’s convenient or it benefits them in some way (with the assistance of plausible deniability).

Bring your pet dog into a building even though you’re not supposed to? It’s okay, just pretend to be disabled and say it’s a service dog. Want to make lots of money on a film about autism but can’t bother to spend time working on accommodating an autistic actor? It’s okay, just hire someone to pretend to be autistic instead. (/s)

The trouble with all of this is that disabled identity is being appropriated and used by nondisabled people to generate personal benefit and/or capital, all while actual disabled people remain marginalized. And the mis-appropriation of disabled identity creates false ideas in the public consciousness, about what disability is and how disabled people act.

People who fake having service dogs create situations in which actual handlers have trouble being taken seriously or gaining access to establishments. People who create films about the disabled experience without including disabled actors & writers create situations in which misconceptions and stereotypes about a certain disability are perpetuated and exaggerated.

The most disturbing thing about this dynamic is that disabled people are oppressed. It’s not like abled people are pretending to be us because they want to enjoy the sociocultural “benefits” of disabled life (there are none). We’re not an exalted category. We’re not nobles, or members of a high class. Rather, our lives and stories and meager legal protections are exploited by those who have no need to do so. Abled people are already advantaged, and they use our existence to further widen that gap in status.

I can’t stop being autistic when it’s convenient. I can’t stop being chronically ill when it’s convenient. I can’t stop having mobility issues when it’s convenient. This is my life every day. So to the student at the testing center, to Sia & Maddie Ziegler, and to every other abled person who’s put on a disabled persona: stop acting like this is your life when it’s not.

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#ableism#autism acceptance#autism awareness#autismacceptance#aba therapy#disability justice#disability rights#music film#sia#Maddie Ziegler#autism service dog#service dog

546 notes

·

View notes

Text

What it’s like to have misophonia

Hi everyone, it’s Abby, Eden’s girlfriend! I also go to UVM, I use she/they pronouns, and I have undiagnosed ADHD (and probably autism as well). I also have a condition called misophonia, which is likely familiar to many of you.

For those of you that don’t know, misophonia is defined as a disorder where certain sounds (trigger noises) spark severe emotional and/or physiological responses. The name specifically means “hatred of sound.” Some common triggers are chewing, tapping, sniffing, etc. Like many disorders, it exists on a spectrum.

It’s separate from Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD), but they often manifest together, as in my case–enough that many people suspect a linkage between misophonia and neurodivergence. It’s probably magnified by SPD as well.

Misophonia can also develop at any age, unlike SPD, which is present from birth. I developed symptoms around age 11, and my strongest trigger noises are chewing/smacking sounds. Those are accompanied by a range of “associated sounds” like crinkling wrappers that aren’t standalone triggers, but tell me that I’m probably about to become very uncomfortable.

The physiological response induced by misophonia is overwhelmingly negative. I always get very flustered and my body produces a severe anxiety response. It’s definitely enough to be disabling. In the past, if the sound was strong, I would scream or hit someone. I used to have detailed, violent intrusive thoughts about killing people, just to end the misery I was in. And there is always a lot of crying involved. It’s gotten better over time, and I’ve been much happier since I started using earplugs more. But I still get very anxious when someone eats in class, for example, and it makes me absolutely unable to focus. I’ll usually start crying then too, and feeling very itchy and hot.

One of the worst instances happened a few years after the condition developed. My family and I were at a baseball game. The game had just finished, and we were sitting in the car waiting in parking lot traffic. I was totally fine, I was very pleased with the game and straight vibing. Unfortunately, my sister and I got into a sibling spat, I probably said something I shouldn’t have, and she retaliated by smacking her lips at me. I went completely off the rails at that. I screamed and hit her in the face and absolutely broke down in tears. My parents were taken so off-guard by this shift in moods, and my dad said something invalidating that I forget because I was so overwhelmed at that point.

I sat there crying for half an hour, basically knowing that there was no way I could explain this to them in a way that they’d understand. How can you describe the emotional distress a tiny little sound causes, especially to someone who has no experience with that? In addition, my own sister had just weaponized my disability against me and seemed to show no remorse. That’s what I’d call a Whole Mess.

Realizing this, I was ashamed for years. I refused to wear my earplugs because I thought there was something wrong with me, and I didn’t want anyone else to know. In eighth grade, however, I met another person with misophonia who was very vocal about awareness. That helped me accept myself and take my needs more seriously. Although I was still shy about it, I felt much less alone, and I always got very internally excited when they mentioned it.

My parents have also been increasingly supportive over the years. When it first developed, both my mom and dad were absolutely baffled about why in the world I was crying and yelling at dinner. Over time, they’ve encountered articles, and we worked together to find solutions for me. They’ve bought me a LOT of earplugs (which I leave all over the house lol), and adjusted eating schedules with me. My mom always asks if I have earplugs before eating something in the car. My dad is generally less receptive to my mental and emotional differences, but this past summer, he asked me about the specifics of my trigger noises and my response. It made me really happy to answer his questions, especially since I know it’s not something he intuitively understands.

Managing misophonia is definitely a joint effort–yes, it’s my responsibility to carry my earplugs with me, and to try and not like, smack people, but I would be much less able to function if I didn’t have the support of my family and friends. My high school friend, along with a number of articles and regular old emotional growth, have allowed me to come to terms with my needs and ask for accommodations when I need them. For now, it’s just with good friends, but I hope that as it gets talked about more, me and many other people allow themselves the care and love they deserve.

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you’re only paying attention to autistic people when we die, take a moment to think about why.

Three days ago, I made a Twitter/Instagram post about the death of an autistic boy named Dylan Freeman. You can go read the post on either of those platforms if you don’t already know what I’m talking about.

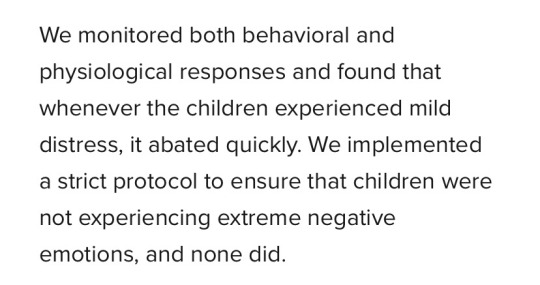

At the time I’m writing this, the post has received over 40,000 likes on Instagram, and it has been viewed by over 220,000 people. That’s more engagement than any other post I’ve made to date, and quite honestly, I feel weird about it. This is what the top of the insights page looks like:

So... yeah. That’s a lot of people.

I wrote that Twitter thread because I wanted to provide a rebuttal to the narrative that Dylan’s life didn’t matter, or that he was burdensome & therefore his death was “understandable.”

And in some ways I’m glad that it’s being shared so widely. Because it spreads the message that autistic people are not subhuman, and that we have the right to live in this world. It also directs more traffic to our account, so more people follow us and more people learn about autism.

But I keep asking myself these questions:

Why did a post about an autistic child being killed generate more engagement than any of the other educational posts I’ve made?

Why do people pay attention to autistic people when we die, but ignore our lives and advocacy work?

A little over 600 people followed our account after seeing (and presumably liking) the post. But according to the insights page, 91% of people who saw the post weren’t following us. So what about the other ~20,000 or more people who liked the post but didn’t follow us because of it? Who liked it, but never visited our profile or read any of our other posts?

All of that bothers me. Not because it’s bad for our account, or bad for autistic people, or bad to educate others about the hardship that autistic people face in the world. It bothers me because a post about a violent, heartbreaking event, has surpassed other posts we’ve made that can help prevent that same type of violence and heartbreak.

That’s the important takeaway here.

If y’all really care about autistic people and you want us to stop being murdered, you need to start amplifying our voices and paying attention to our lives, not just our deaths.

That means not just following us, but following people like Lydia X.Z. Brown, Julia Bascom, Ari Ne’eman, Morénike Giwa Onaiwu, Tiffany Hammond (@fidgets.and.fries), Tee (@unnmasked), and many more.

Consider this your invitation to learn.

~Eden🐢

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you guys have ADD/ADHD, autism, OCD, or something else that affects your ability to concentrate, I highly recommend the chrome extension Mercury Reader. You just open whatever link you're using, then click on the MR icon (it should look like a rocket) and it'll simplify the page so that it's in a focus-friendly layout. Instead of having random pictures and word boxes all over the screen, it'll be in a vertical format with nothing to distract you so you can focus on what's important. You can also adjust the text size (small, medium, large), font (serif, sans), and theme (light, dark). And the best part is, it's completely free! It's honestly one of the best things I've ever downloaded.

This is an article without the extension. See that messy format, and how the actual article content only takes up a fraction of the page? It's no wonder it took me 7 hours to write that paper.

The same article, this time with Mercury. The user-friendly settings are at the top, and the rest of the article is formatted vertically down the middle with no free-roaming pictures or words. How nice.

73K notes

·

View notes

Text

Autistic people often have altered body language and patterns of movement.

This is due to a variety of factors, which include inherent differences in proprioception and sensory processing, and frequent comorbid dyspraxia, hypermobility, etc.

Here are some common features of autistic body language (not universal, just common):

walking without swinging the arms

raptor hands

stiff, hunched, or otherwise unusual posture

an uneven gait

walking with flat feet (meaning the front of the foot hits the ground at the same time or before the heel. It’s normal for the heel to hit the ground first)

toe walking

frequently not making eye contact

often having blank or unusual facial expressions

covering/plugging ears, eyes, nose, etc. to block out sensory input

sitting in unusual positions

clumsiness and a tendency to bump into things, step on people’s feet without noticing, accidentally get too close to people, etc.

stimming! This could mean rocking back and forth, flapping hands, twirling hair, flicking fingers, etc.

trouble with coordination, which might lead to some difficulties playing sports or mimicking the physical movements of other people

There are probably some things I’m forgetting, and not everything on this list will apply to every autistic person. Some of us may only display a few of these traits, or we might express these traits differently depending on the circumstances.

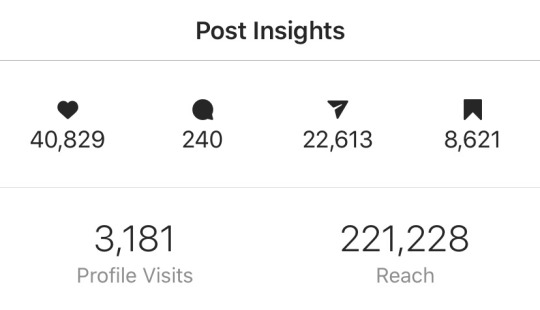

Now I’m going to include some illustrations done by Miss Luna Rose for WikiHow, which demonstrate autistic body language:

The person on the left is autistic. They are sitting in an unusual position, and are stimming with their hands.

Both of these people are autistic. Neither of them are making eye contact, and both of them are stimming and expressing themselves with their hands.

This person is autistic. They are plugging their ears to block out auditory input.

The person on the right is autistic. They are looking away/avoiding eye contact to block out sensory input.

This person is autistic. They are stimming with their hands, with their eyes closed, to regulate sensory input and/or express emotion.

Hopefully this list of traits, coupled with these illustrations, help you to recognize autistic body language in other people and yourself :)

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#ableism#autismacceptance#autism acceptance#autism awareness#autistic body language#body language

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Autism and authenticity

I was reading through @/ theautisticlife’s Instagram stories earlier and was really struck by her writing on authenticity. Many autistic people feel the need to mask, and hide parts of themselves that are incongruent with dominant social norms. This makes it easier to be accepted by neurotypicals, but it comes at a great cost to their mental health.

On the other hand, some autistic people never really mask that much. We’re true to ourselves in the majority of scenarios, regardless of what other people might think. I fall into this category, and it made my life harder throughout elementary, middle, and high school.

My authenticity was off-putting and disorienting to many classmates, who weren’t used to their peers being so sure of themselves and what they believed. As a result, I was informed many times that certain people “didn’t like me,” but they were never able to pinpoint specific reasons. I never did anything particularly mean, rude, or insulting to others. I wasn’t selfish, or manipulative, or aggressive. I just did things that I felt like doing, wore things I felt like wearing, and said things without worrying too much about what others would think. And for some reason, that scared people.

Sometimes peers would make comments about my appearance, mannerisms, etc. Or they would ask me why I was doing something. For example, I stopped shaving my legs and armpits in freshman year of high school, because the only reason AFAB people are taught to is because of a capitalist ploy by razor companies. There’s nothing “unhygienic” about it at all. So once I learned that, I just stopped shaving, because it didn’t make sense and I didn’t want to. But when I changed for gym class in the locker room, sometimes people would make comments: “Your legs are hairy,” and “Your armpits aren’t shaved.” My reply was always, “I know.”

Funnily enough, some of those people followed suit in later years, once they realized the same things I had realized prior, and decided that they also didn’t care much for capitalist beauty standards. I was just ahead of the curve.

I’ve always been myself. I don’t compromise my values for the acceptance of others. If something doesn’t feel right, I don’t do it. If something is morally wrong, I tell people what I think about it. This is what has caused people to dislike me in the past: my authenticity threatens the validity of their conformity.

People follow along with the crowd because it’s safer, because they know they’ll be protected by their peers. But what if the crowd is doing something wrong? What if the crowd is harming others? People don’t want to know, because it calls into question their reasons for following along with the group in the first place. It makes them feel like their safety net might collapse. It forces them to challenge their worldview.

One of the most interesting stories I’ve ever experienced because of this, started with a fraught invitation to a Christmas party in 8th grade.

I was friends with two people in the group, and friendly acquaintances with most. One of the people I was friends with invited me to the group’s annual Christmas party, but apparently didn’t tell the others that she had invited me until about two weeks beforehand. When she informed the rest of the group that she had invited me, all hell broke loose in their groupchat.

Most people were neutral on the subject, but two people in particular were vehemently opposed to my presence. One of them even went so far as to say that she hated me. Reasons cited by the two of them were that I was weird, that I didn’t get along with other people (which was a strange thing to say, given that they barely knew me), that I would ruin the party, and that I didn’t deserve to come.

You can imagine how I felt when the people I was friends with sent me screenshots of that conversation. It was deeply confusing and hurtful to me, and it only exacerbated my already prevalent anxiety about what others were saying about me behind my back. I spent the night crying about it to my mom, and she let me stay home from school the next day.

After school on the following day, I started to get texts from people in that friend group. They were worried about me, and wanted to make sure I was okay. I told them I was fine, that I took the day off. Then, I got a text from the girl who had said she hated me only 24 hours prior.

She apologized for everything she had said, and told me she had been worried sick all day when she realized I wasn’t at school. Then, she said something interesting. She told me that she didn’t actually dislike me, but rather that she felt threatened by me because I’m always so true to who I am. She said, “You’re a better person than me,” and explained that because of that she felt insecure, and lashed out. I told her that I understood, and wouldn’t hold the incident against her. And I thanked her for being honest with me.

I think that’s one of the most important, illuminating conversations I’ve ever had in my life. And it fits in perfectly with everything I’ve discussed so far in this post. One of the main reasons autistic people are bullied, ostracized, excluded, etc. is because we amplify other people’s own insecurities. Our honest, unassuming demeanor puts a mirror in their faces and forces them to confront who they are, what they think, and how they truly feel. It makes people call into question the things they’ve been taught to think and feel, and opens up the possibility for more authentic ways of relating to others. To neurotypical middle schoolers especially, that prospect is frightening.

I think that’s why, as my peers have gotten older and started developing a stronger sense of who they are, it’s gotten much easier for me to interact with them. Because now that they’re secure in themselves, they have a much greater capacity to understand that my existence isn’t a threat to their personal lives. And they can actually appreciate my personality, without being scared off by my strong passions and interests.

I’m sure I’ll always face some challenges of this sort, given that social cohesion is an important aspect of the way neurotypicals operate in the world. But luckily I’ve been able to make friends with other autistic and neurodivergent people, who understand me and support me in all my endeavors. I used to wonder if I’d ever be able to make lasting friendships, where the other people truly care about me and love me for exactly who I am. Now I know the answer: yes.

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#ableism#autismacceptance#autism acceptance#autism awareness#authencity#neurodivergent#neurodiversity

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you’re someone who experiences panic attacks, you need to check out the app PanicMechanic

This isn’t a paid promotional thing, by the way. I just think it’s important that y’all know about this app, because it’s been immensely helpful to me. Also before you start reading know that the first two paragraphs are me describing my own panic attacks, so content warning for physical sickness and weight loss.

I’m someone who experiences frequent, severe panic attacks. Before I got this app and started communicating about my needs to the people closest to me, my panic attacks would usually make me throw up. At one point last year, my anxiety was so severe that I could barely eat, and I threw up everything I ate. I was throwing up every single day, multiple times a day. It was absolutely miserable. During that time, I lost 5 pounds in 5 days (and I’m thin to begin with, so it was a big deal).

I still struggled with this up until about a month ago, even though I take two different anxiety meds- one of which is an anti-nausea appetite stimulant (as a side effect). It didn’t matter what my meds were, how much deep breathing I did, or how many times I grounded myself by naming things I could sense. Nothing seemed to work. My autonomic nervous system is explosively hypersensitive, and my fight-or-flight can be set off by just about anything. Once the chain reaction has started, it’s impossible to stop.

Or so I thought. Around a month ago, my mom walked into my room with the latest copy of the University of Vermont’s magazine. In it was an article about an app called PanicMechanic, which had been developed by people in the engineering department at UVM. It uses a form of biofeedback, by tapping into your phone’s camera. You put your finger over the lens and the app measures your heart rate.

Then, the app cycles through a series of questions. It asks you what caused the panic attack (you can add custom triggers), then it asks you what your anxiety level is, on a scale from 1 to 10. It might also ask you questions about your sleep quality, food consumption, exercise levels, etc. Then, it will tell you approximately how long is left until your panic attack ends (based on previously recorded ones). After that, it goes back to your heart rate. The screens keep cycling through, with your heart rate graph being shown each time, until you press “Finish Attack” in the upper righthand corner.

The app sounds simple, and it is. But it’s fantastically effective at facilitating mindfulness, and a sense of control over the situation. Before I started using it, I had a really hard time getting out of my head and staying focused on my immediate reality. Now, it’s way easier to regain control of my body and my breathing. My panic attacks used to last anywhere from 5 to 30 minutes. Now, they only last 5 to 7 minutes. And the best part? I don’t throw up anymore!

The app is free to download on iPhones, and soon it will be available on Androids. There’s a 7 day free trial, so you can see if it works for you before paying the yearly fee (which I believe is around $50 annually, or about $4 a month). That’s extremely cheap compared to the usual costs of therapy and medication.

Since I’ve been using the app, I’ve felt an enormous change in my ability to gain control of anxiety. The fact that it’s so easily accessible in the moment makes it that much more effective. I really hope this helps some of you!

~Eden🐢

#panicmechanic#panic attack#anxiety#anxiety disorder#panic disorder#ptsd#bpd recovery#actually autistic#autism#autistic#autismacceptance#ableism#autism awareness#autism acceptance

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love autistic people’s sense of humor

And when I say that, I don’t really mean our “sense of humor.” Because a lot of the time, it’s not intentional. I mean the way we say things that aren’t meant to be funny, but end up being hilarious.

I saw a post a while back that said “the greatest superpower my autism has given me is accidental big dick energy,” and it’s absolutely true.

Because we don’t pick up on NT social cues as easily, we have highly original thoughts, and we have a tendency to be honest and direct, we end up saying some pretty amusing things.

For example, one time I had friends over for my birthday. One of them had gotten me an ugly graphic T-shirt, whereas the others had given me nicer presents. The friend said, “Now I feel bad, all I got you was this shitty T-shirt.” My response was, “Well, yeah, but-” and then I couldn’t say the rest of the sentence because all of my friends were absolutely beside themselves with laughter. I started laughing too because I realized how much of a blunt, autistic response it was.

A neurotypical might have said something like “It’s not a shitty T-shirt, don’t say that! I really like it.” But it didn’t even cross my mind to say a white lie. Because it’s true, it was a terrible gift. And since I’m autistic, I just acknowledged the truth of my friend’s statement. But I also didn’t care about the gift, I wasn’t insulted by it, and I thought the whole situation was funny.

That’s one of the things I love about being autistic. I’m funny without meaning to be, and luckily my friends appreciate me for it.

~Eden🐢

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

So-called “high functioning” autistic people have meltdowns, too.

There seems to be some sort of notion in the NT, parent-dominated autism sphere, that so-called “high functioning” autistics (read: conventionally intelligent autistic people who can speak) don’t have meltdowns like the kids who are “really” autistic. But if those parents were to dig a little deeper, I’m sure they’d find that there’s more to autistic self-advocates than meets the eye. Just because we don’t put our most difficult moments on display constantly, doesn’t mean those moments don’t exist.

Regardless of the fact that nobody is owed any piece of my story, it’s important to me to share what my meltdowns were like, from an insider’s perspective. This aspect of my childhood is what led to me getting diagnosed at age 8, which is early considering that I’m AFAB. So here I’m going to share something I wrote in 7th grade and revised today, about a meltdown I had while I was still in elementary school. I go into a lot of detail and the entire situation was very distressing, so if you aren’t in the headspace to read this please don’t.

Here it is:

My head is spinning, on constant rewind and replay. The argument comes in flashes, with angry faces and ears that never listen to me. I’m dizzy and nauseous and I feel my throat tighten as I start to cry. I don’t want to leave the living room and I don’t want to be touched. My dad yells, his voice unbearably loud. He says I have to go to my room, and threatens to carry me if I don’t. It doesn’t matter that I’m stuck on the couch, that I can’t move. He starts counting backwards from three.

“Three… two… one… okay! That was your choice.”

“No!” I yell, “No! No! No!”

But I know what comes next. He lunges towards the sofa and grabs me roughly by the armpits as I claw at the fabric and try to hold on. My hands slip, and he throws me over his shoulder. I scream, my voice tearing at my throat. I bite his shoulder, scratch his back, and try my best to knee him in the ribs. I twist and writhe in an attempt to escape his firm grasp. But he manages to hold onto my 10-year-old limbs as he stumbles down the hallway, then flings me onto my bedroom floor.

My spine slams into the hard linoleum tiles. Pain surges through my back and out through the top of my head. I yell, tears streaming down my face. Dad tries to leave me there on the ground, tries to slam the door behind him. I lunge at the doorknob as he leaves, twisting it to try and keep the door open, but he is stronger and locks it before I escape. Another piercing wail reverberates around the small room. I’m hurting my own ears, but I can’t stop. I hear my dad yell to my mom,

“It’s your turn! I can’t do this anymore!”

I throw my body at the door, ramming my shoulder and hip into it. I accomplish nothing, so I lay down and prepare my legs. Feet on white paint, I kick violently at the center of the door. This is a routine I’ve gotten used to over time. With my back on the cold tile floor, my legs battle with the wood. I cry in outrage, I shriek and sob, aware of the situation but unable to stop myself. I hear my mother approaching. She opens the door a crack and slips in, quickly slamming the door behind her. I leap at the handle and try to twist it open, but she grabs my wrists tightly. The blanket she had in her hands falls to the floor.

“Calm. down. I’m going to wrap you, don’t try to get away because the door is locked.”

She moves to the center of my bedroom and spreads the blanket out on the floor. She calls my father in for backup.

“Honey! Get in here! I need you to hold her down so that I can wrap her!”

He rushes into the room, and slams the door behind him. It sounds like a gunshot. They’re here to trap me like an animal, with earplugs in so they don’t have to feel the weight of my screams. I scurry to the farthest corner of the room and curl into a ball on the floor, still sobbing loudly. Don’t touch me. Don’t touch me. Don’t touch me. My dad yanks me off of the ground, throwing me unceremoniously onto the edge of the blanket in the middle of the floor. My back will be bruised tomorrow.

Mucus drips from my nose and onto his exposed arm. He attempts to stretch out my legs, but I bend and twist and press back against his force. My mom tears at my arms, trying to stretch them out by my sides, lay me out flat on the edge of the blanket. After minutes of struggle, I accidentally fall into a position where they can do what they wish. My mother seizes the opportunity, and throws half of the blanket over me while my dad keeps his knees on my legs and hands on my wrists. My throat is raw. I look at my parents through my tears, the water blurring and distorting their image. I can see that they are just as sweaty as I am. I try to fight back but it’s not enough as they roll my body in the blanket, my face grazing the floor with each rotation. My arms are pinned to my sides, my legs can’t bend, and I can’t turn my head so I lay there face down. Mom sits on my back and dad sits on my legs, and I feel the air leaving my lungs. I gasp and choke and tell them I can’t breathe, but they don’t listen. They never listen.

They won’t release me until I fall silent, but I do not close my mouth. My rage increases with my guilt. I won’t let them squeeze my breath away, but it must be my fault that they’re trying to. I wish I was good but they just don’t listen. With these thoughts, in a maddening burst of emotion, I tear myself out of the suffocating blanket. My parents both yell, try to keep my arms down and lungs compressed, but suddenly I’m too strong for them. My ears collapse inside themselves as I stumble to the ladder of my loft bed. They can’t reach me up there. I climb as I cry, crawl into the blankets and grab my water bottle. I drink to ease my pounding headache, the popped blood vessels in my face. Water will quench the angry fire.

...

Meltdowns like this didn’t just happen every once in a while. When I was a young child, they happened almost daily. And as I got older, they happened once or twice a week. They began going away when I started taking anxiety medication at age 12. But they still happen sometimes. The last massive one (like this narrative describes) happened when I was around 16- two years ago. But often, they were worse. I would break things, cut things, and smash things. I would threaten to hit my parents with metal objects if they got any closer to me. I did those things because I felt I had no other way to get my point across, since they were so dismissive of my boundaries and needs.

These experiences were very traumatic to me, mostly because of the way my parents always handled the situation- with anger, force, and disrespect. We’ve discussed this recently and they both understand how harmful their actions were, and feel remorseful. Regardless, it’s important for me to talk about this so that other parents of autistic kids don’t make the same mistakes my parents did.

To all the other autistic people who have gone through similar experiences during meltdowns: I see you. I am you. I’m with you.

~Eden🐢

#actually autistic#autism#autistic#aba therapy#ableism#autismacceptance#autism acceptance#autism awareness#autism meltdown#meltdowns

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

How the Autistic Brain Works, Part 1: Locally Oriented Processing

Some of you might already be familiar with the Enhanced Perceptual Functioning (EPF) model of autism (click on the underlined portion to read the paper), and some of you may not. So for those of you who are new to this model of understanding autistic brains, I’m here to explain it. The EPF model was created in the early 2000s, by a research team including Michelle Dawson, who is autistic. The model is broken down into 8 separate principles, that describe different aspects of the way autistic brains work. Today, I’m going to explain the first principle.

Principle 1: “The Default Setting of Autistic Perception is more Locally Oriented than that of Non-autistics”

What does that mean? Basically, it means that autistic people are much better than non-autistics at accurately perceiving and identifying the parts that make up a whole. However, this ability does not limit us to seeing just the “little picture.” We are able to perceive the whole just as well as non-autistics. A common saying about autistic people is that we “can’t see the forest for the trees.” But according to research, that’s not correct. We see both the trees and the forest, it’s just very hard for us to obscure our vision of the trees and only see the forest instead. Before reading further, you need to know the definitions of three key words in this context: local, global, and hierarchical.

Local stimuli: small elements that make up something larger or more complicated.

Global stimuli: larger patterns that are made of a bunch of local stimuli put together.

Hierarchical perception/processing: the way that local and global stimuli are perceived, with local stimuli at the bottom and global stimuli on top. Non-autistic people tend to perceive things from the top down (global to local), whereas autistic people perceive them from the bottom up (local to global).

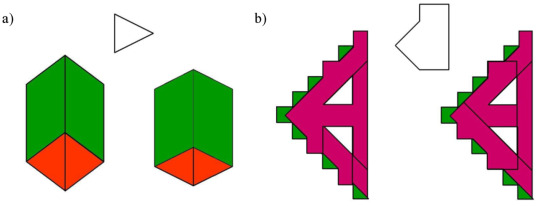

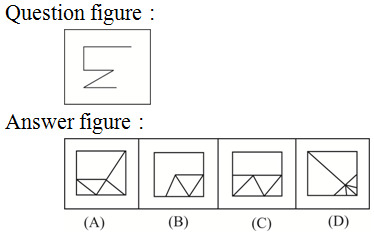

Three examples of tasks given to autistic people in clinics that demonstrate our advantage in local processing are the Block Design subtest of the Wechsler scales (an intelligence test), the Embedded Figures Task, and being asked to draw impossible figures.

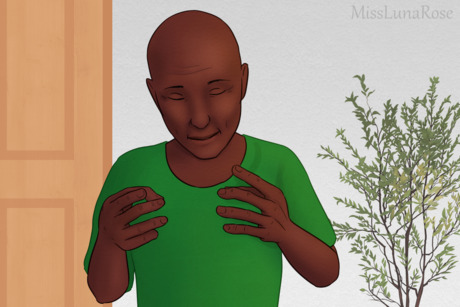

The Block Design subtest is a task with 9 blocks that are red on two sides, white on two sides, and half-white-half-red on two sides. The goal of the task is to arrange the blocks in a manner that replicates a pattern on a sheet of paper next to the blocks. The task is scored based on how long it takes the participant, and how accurate the participant’s designs are. Here are pictures for a better idea of what it looks like:

Autistic people are known for having what’s called a “peak of ability” on the block design subtest. This is because we have an enhanced ability to pick apart the local elements of global stimuli, and arrange them properly. In this example, the local elements are the individual blocks, and the global stimuli are the patterns we’re trying to replicate (in the image above, the “unsegmented” illustrations are the patterns).

The same thing goes for the Embedded Figures Test, which is a task where the person has to select which of a series of figures contains a specific shape that’s embedded in the lines. Here’s an example:

The answer to both a) and b) is the right-hand figure.

Here’s another example, just for fun:

The answer is C.

Finally, here’s a drawing of an impossible figure. These are easier for autistic people to draw because we can focus on the individual lines without getting messed up by the appearance of the figure as a whole:

Here’s what the authors of the Enhanced Perceptual Functioning paper have to say about this:

“When the processing of a global aspect conflicts with a local analysis among typically developing persons (perceptual cohesiveness in [Block Design], impossibility of a figure in [drawing of] figure tasks, visual context in [Embedded Figures Task]), autistics perform at a level superior to their comparison groups. In contrast, when this conflict is diminished, for example by segmentation to diminish the perceptual cohesiveness in [Block Design] or in copying possible vs. impossible figures, autistics are brought back to a level of performance equivalent to that of typical individuals. This indicates that autistics are not obliged to use a global strategy when a global approach to the task is detrimental to performance. For example, autistic persons are better able than typically developing persons to copy impossible figures (Mottron et al., 1999b), and as able to identify that impossible figures are impossible (Brosnan, Scott, Fox, & Pye, 2004). In contrast, typical individuals cannot adjust to the situation of an impossible figure coinciding with a possible drawing.”

To sum up Principle 1, the authors write:

“The default setting of the autistic perceptual system toward local information contrasts with typical hierarchical processing (Robertson & Lamb, 1991) that combines ‘‘global advantage’’, the superior relative speed and accuracy of global target detection, with ‘‘global interference’’, the asymmetric influence of global processing on the detection of the local stimuli.”

This basically means that instead of perceiving things from the top down (like most other people), autistic people perceive things from the bottom up. Our brains are like direct democracies.

I find this incredibly fascinating, especially given how many autistic people I know (including myself) are leftists. One of my main special interests is Democratic Confederalism, which is a political system of community government and direct democracy in both the public and private spheres- it prioritizes the “local elements” and gives them freedom to govern themselves.

Autistic people also tend to act in a very autonomous manner, and not give into peer pressure as easily as others. Greta Thunberg is a great example of an autistic person acting autonomously (as a local element) to spark change from the bottom up.

I wonder how much of all this has to do with the way we perceive our everyday world- and I suspect it’s all very much related.

~Eden🐢

#actuallyautistic#actually autistic#autism awareness#autism#Autism Acceptance#enhanced perceptual functioning#unjust hierarchy#anarchy#anarchism#democratic confederalism#leftism#bottom up#direct democracy

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Public School: an open letter from an autistic student in the graduating class of 2020

Let me preface this by saying that in many ways, I suspect that my experience with public school was no different than many autistic students’ experiences in private schools, charter schools, and so on. That’s because ableism is pervasive in global society, and it affects every aspect of our lives. But here I have written my own experiences in public high school.

I can’t count the number of times I heard students use slurs such as r*tarded, the n-word, f*g, d*ke, etc. By far the most common slur used was r*tarded, which was often used within earshot of teachers who usually said nothing. Sometimes people would even use the words “sped” and “autistic” as insults, as if my educational accommodations and neurology were something to be weaponized to make others feel terrible about themselves. This common cocktail of slurs made me feel extremely unsafe.

Sometimes I spoke up about it, but most of the time I stayed quiet, because I just wanted to get through my day without having to argue with people about my humanity. Even students who were generally pretty socially aware and vocally supported LGBT people and people of color, often used the r-slur. And it hurt way more when I saw that type of behavior from those people, who I thought I could trust.

In my experience, ableism against autistic and other developmentally disabled people is probably the most prevalent form of dehumanization in the school system. It’s so ubiquitous that some people don’t even know what you’re talking about when you refer to the word r*tarded as “the r-word.” It’s so unquestioned that entire classes of people would laugh and crack jokes about autistic students who were having meltdowns that you could hear down the hallway.

I know, because I’ve been in those classes, and tried not to cry as everyone around me started laughing at another autistic person’s pain. It’s really hard to describe how humiliating that was. Because I’ve had meltdowns just like the ones other students were having, which means that my classmates might as well have been laughing and cracking jokes about me, in my most vulnerable moments.

One day at lunch, I overheard another autistic student talking to his aide about how his gym clothes had been thrown into the locker room toilet, and he had been shoved and choked by other boys as he tried to get his clothes out. His aide was aghast, and asked if this had been brought up to the administration. The student told her that he had talked to the office about these same students many times before, but it never seemed to change anything.

But these types of overt verbal and physical violence were not the only things autistic students had to face. We also had to deal with extreme levels of sensory overload, caused by events that were not planned without our needs in mind. Even if prom hadn’t been canceled this year due to coronavirus, I still wouldn’t have been able to go. The music would have been too loud and overwhelming, even with earplugs. I nearly cried at way too many pep rallies to count, from the bone-shattering vibrations of speakers blaring “upbeat” music, combined with hundreds of shrieking, shouting students. It’s absolutely horrible to have to endure severe physical pain just to be socially included. I spent most of my time at pep rallies plugging my ears with my hands.

My public school did a pretty terrible job at educating students about autism and other disabilities. Autism was only brought up once in a blue moon, and when it did get brought up, it was framed as if it’s some sort of disease that requires “awareness” and a “cure.” The problem was that barely anyone really understood what autism is, teachers included. On the very rare occasions that it was brought up, I was usually the only autistic person in a class full of people talking about it, and I had to correct both students and teachers on certain fundamental facts.