Text

There’s Never Enough Time

A personal one today …

Are you always busy? Then maybe it’s time to rest.

As Nietzsche wrote in Why Am I So Wise?:

‘Almost too fiercely dost thou rush, for me, thou spring of joyfulness! And ofttimes dost thou empty the pitcher again in trying to fill it.

‘And yet must I learn to draw near thee more humbly. Far too eagerly doth my heart jump to meet thee.

‘My heart, whereon my summer burneth, my short, hot, melancholy, over-blessed summer: how my summer heart yearneth for thy coolness!

‘Farewell, the lingering affliction of my spring! Past is the wickedness of my snowflakes in June! Summer have I become entirely, and summer noontide!’

You can read the article here.

#philosophy#blog#original content#the human front#existentialism#meaning#nietzsche#suffering#time#philosophy memes#article#philosophyblr#philoblr

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Treating madness with reason

In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s famous novel Crime and Punishment Lebeziatnikov witnesses Katerina Ivanovna at her wit’s end. Katerina has consumption (tuberculosis) and recently lost her husband. Now she’s losing her sanity. Lebeziatnikov has heard of a solution: reason. But Katerina just won’t be convinced by any.

‘"She has certainly gone mad!" he said to Raskolnikov, as they went out into the street. "[T]here isn’t a doubt of it. They say that in consumption the tubercles sometimes occur in the brain; it’s a pity I know nothing of medicine. I did try to persuade her, but she wouldn’t listen."’

Lebeziatnikov claims that, although she is ‘out of mind’, Katerina can be restored from her madness if she listens to reason.

‘[W]hat I say is, that if you convince a person logically that he has nothing to cry about, he’ll stop crying. That’s clear. Is it your conviction that he won’t?

‘[D]o you know that in Paris they have been conducting serious experiments as to the possibility of curing the insane, simply by logical argument? One professor there, a scientific man of standing, lately dead, believed in the possibility of such treatment. His idea was that there’s nothing really wrong with the physical organism of the insane, and that insanity is, so to say, a logical mistake, an error of judgment, an incorrect view of things. He gradually showed the madman his error and, would you believe it, they say he was successful?’

Sigmund Freud later wrote something similar. He described, for example, mourning a pathology to be cured. So understood, in the extreme our response to loss, as an experience, is a wishful psychosis and the individual must eventually return to ‘reality’.

'Reality-testing has shown that the loved object no longer exists, and it proceeds to demand that all libido shall be withdrawn from its attachments to that object. The demand arouses understandable opposition—it is a matter of general observation that people never willingly abandon a libidinal position, not even, indeed, when a substitute is already beckoning to them. This opposition can be so intense that a turning away from reality takes place and a clinging to the object through the medium of hallucinatory wishful psychosis. Normally, the respect for reality gains the day.'

Perhaps the state of mourning—in being treated as an illness—can be reasoned away, too. I doubt it.

As for the unwell Katerina, successfully deploying reason on her also seems unlikely. Even Lebeziatnikov had his doubts.

Moreover, Katerina had reasons for her unreasonableness. Reason is a contradiction! The death of her husband, illness, poverty... How does one withstand such arbitrary wickedness? If Reason ever graced our lives, it deserted us long ago.

#philosophy#literature#crime and punishment#fyodor dostoevsky#sigmund freud#psychology#reason#novel#book#psychoanalysis#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

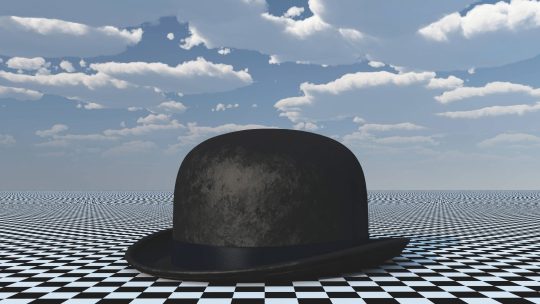

The Unbearable Lightness of Being is a novel written by Milan Kundera. The bowler hat is one of its motifs. (rolffimages via Adobe Stock)

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

If someone offered you a life that repeated itself infinitely, would you take it? Life as we know it is deprived of weight; for every event occurs only once. Thin and fleeting, the present is inscrutable. The future is shrouded by uncertainty. Friedrich Nietzsche, for one, favoured repetition: the beauty of necessity. A life of eternal recurrence? Divine!

The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kunderais a story about the heavy and the light. The heavy signifies fate: the force of being ‘nailed to eternity’, of carrying the ultimate responsibility of our actions by seeing them repeat, their necessity, their reality, and their truth.

The light signifies the present: its weightlessness, ethereality, and the absence of burden.

Which is the correct approach to life: heavy or light? Nietzsche and Parmenides disagree on which is the positive pole.

According to Nietzsche’s eternal return, fate is to be loved. In it we face what is necessary and thereby see beauty. Amor fati!

Parmenides, by contrast, saw splendidness in constancy. He forbade change, let alone a perpetuity of things coming in and out of existence. Reality is unchanging; being cannot be dispelled, regathered, or repeated. Lightness is cherished.

The answer remains ambiguous to us all. Indeed, Kundera’s characters slew between both sides of the dilemma. Though one senses Kundera himself is drawn to the heavy.

Our experience of love (amongst many other things) exemplifies the opposition of heavy and light.

In love you attach yourself to The One: the person with whom you could spend eternity, over and over. Love is therefore heavy: undying and unable to be thinned by repetition. ‘En muss sein!’ Kundera cites Beethoven: ‘It must be so!’ Love is a necessary connection.

Yet, in imagining just one small change to the past, we meet an unbearable lightness. ‘Es könnte auch anders sein,’ writes Kundera: ‘It could just as well be otherwise’.

Life is full of such mysterious oppositions and ambiguities.

#philosophy#existentialism#literature#milan kundera#the unbearable lightness of being#friedrich nietzsche#fate#amor fati#love of fate#books#novel#story#motif#bowler hat#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

World Philosophy Day

It’s World Philosophy Day!

To celebrate we invited two academics, Louise Chapman and Constantine Sandis, from Lex Academic, to be interviewed by The Human Front.

Lex provides researchers with editing, indexing and translation assistance, with the aim of getting their work published. And fewer things are more important in philosophy nowadays than publishing.

You can read the interview here.

#philosophy#blog#original content#the human front#interview#academia#academic#lex#lex academic#editing#indexing#translation#proofreading#publishing#publications#literature#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

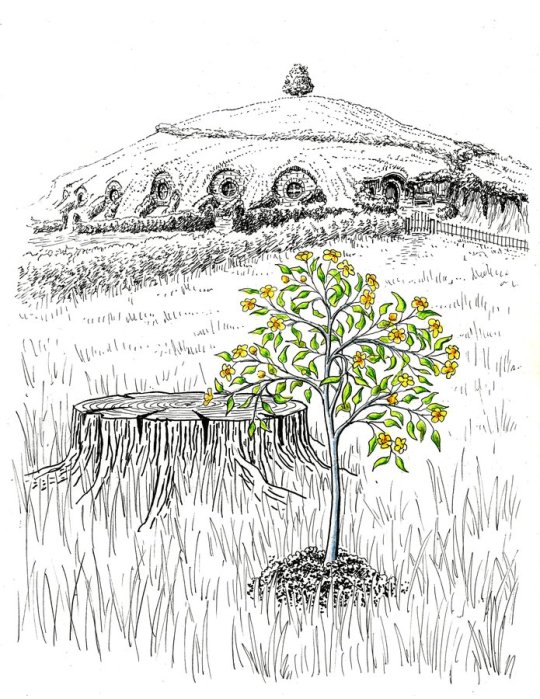

‘Sam's mallorn tree sapling in Hobbiton planted next to the stump of the Party Tree’ by Matěj Čadil.

'Sam planted saplings in all the places where specially beautiful or beloved trees had been destroyed, and he put a grain of the precious dust in the soil at the root of each. [I]f he paid special attention to Hobbiton and Bywater no one blamed him.'

Sustaining nature in his community and keeping a connection to the past—this is how Samwise Gamgee sowed good into the world.

Read more here.

#philosophy#ethics#lotr#the lord of the rings#lord of the rings#samwise gamgee#samwise#plant#nature#hobbiton#art#drawing#middle earth#morality#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Small Nut With a Silver Shale

Is there a way to be morally good without being selfish? Let's use the life of Samwise Gamgee, from The Lord of the Rings, as a case study for the question.

Whatever philosophical system of ethics we come up with for Sam, his morals ring disproportionate. The presence of nature in his people’s neighbourhood takes precedent in his priorities over various other charitable and compensatory acts which are better able to cure the ills of Sauron. Does this make Sam a particularly bad or ignorant person? No. This conclusion doesn’t seem exactly fair or right; for Sam is a wonderfully dedicated and loyal hobbit.

‘Sam planted saplings in all the places where specially beautiful or beloved trees had been destroyed, and he put a grain of the precious dust in the soil at the root of each. He went up and down the Shire in this labour; but if he paid special attention to Hobbiton and Bywater no one blamed him.’

Read more here.

#philosophy#blog#original content#the human front#ethics#morals#morality#society#lotr#lord of the rings#middle earth#the lord of the rings#rings of power#fantasy#samwise gamgee#sean astin#literature#books#film#cinema#philosophyblr#philoblr

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Absurd Man

In our latest article we dissect Camus’ ‘absurd man’ (not literally!) in The Myth of Sisyphus. We focus on the actor of the stage.

‘The actor taught us this: there is no frontier between being and appearing. Let me repeat. None of this has any meaning. The final effort for these related minds is to manage to free themselves also from their undertakings: succeed in granting that the very work, whether it be conquest, love, or creation, may well not be; consummate the utter futility of any individual life.’

Read the article here.

#philosophy#blog#original content#the human front#existentialism#nihilism#albert camus#absurdity#absurdism#actor#literature#books#philosophyblr#philoblr

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Britain versus France

(Pictured: Frenchman Voltaire, who preferred the intellectual views of England, to which he fled in 1726.)

How much of a role do our senses play in knowledge? While we observe things directly and indirectly in experiments, perhaps we shouldn’t trust sensory knowledge—or so Frenchman René Descartes famously thought. He held a mechanical view of nature and of the human body; but he said knowledge is drawn from reason, the pinnacle of which depends on God.

British empiricist John Locke, by contrast, favoured the view that ‘all our ideas come to us via the senses’, a view which was shared by Scotsman David Hume. Similarly, Englishman Thomas Hobbes had already argued that ‘there is no conception in a mans mind, which hath not at first, totally, or by parts, been begotten upon the organ of Sense’. He thought philosophers got too lost in language.

The Brits were teaming up. Even Voltaire, Descartes’ compatriot, fled to England because he associated it with liberty of thought and scientific thinking. And in somewhat humorous fashion (insofar as philosophers are funny) he criticised Descartes’ view as follows:

‘Our Descartes, born to uncover the errors of antiquity but to substitute his own, and spurred on by that systematising mind which blinds the greatest of men, imagined that he had demonstrated that the soul was the same thing as thought, just as matter, for him, is the same thing as space. He affirms that we think all the time, and that the soul comes into the body already endowed with all the metaphysical notions, knowing God, space, the infinite, having all the abstract ideas, full, in fact, of learning which unfortunately it forgets on leaving the mother’s womb.’

Voltaire exaggerated the position of Descartes, who only argued for ‘innate ideas’, not actual knowledge in the womb. Still, Voltaire was right to find the essential point of difference between the likes of Descartes and Locke: they situated the raw materials of knowledge in completely different places.

This was an era of smack talk. Hobbes buried his own philosophical grave by attempting to besmirch others whilst advocating dodgy mathematics.

And people say Brits are polite.

⁂

Some afterthoughts

Is Descartes’ view really one of dualism? Descartes spoke of three distinct kinds (substances): mind (or soul), whose primary mode is thought; matter, which extends in space and of which body is; and God. The pineal gland connects mind and matter. Wait. What?!

Francis Bacon said there are three types of philosopher: ants, spiders, and bees. Empiricists, like ants, accumulate and use whatever they find. Rationalists, like spiders, spin webs. The bee is somewhere in between: ‘it takes material from the flowers of the garden and the field; but it has the ability to convert and digest them.’ We should be like the bee. (My analogies-are-black-magic senses are tingling.)

#philosophy#england#france#smack talk#empiricism#rationalism#mind#voltaire#descartes#appearances#reality#francis bacon#analogy#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘REMEMBER ME!’ 🔥

In Futurama S3E17 Bender is fraught with worry that he won’t be remembered after he dies. Narcissistically, he forces slaves on the planet Osiris IV to build a giant statue of him.

Despite being a robot, Bender is programmed with ways of being human: all foolish and excessive. With this statue he intends to leave behind a mighty legacy.

Humans are usually better than this [sideways glance at Trump Tower]. However, we do like to be known and remembered. So, fundamentally, are we any different from Bender?

Read more about life, memory, and the stories we tell of ourselves here.

#philosophy#blog#original content#the human front#existentialism#story#narrative#catalogue#life#memory#legacy#futurama#bender#cartoons#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Group belief

Can groups of people hold beliefs collectively? Our everyday conversations imply they do: it’s not unusual to hear something like ‘Scientists believe X’, ‘Americans think Y’, or ‘The newspaper is Z-phobic’. The idea feels unintuitive since common sense has it that one belief belongs to one mind. However, in recent years philosophers have gone from focusing just on the beliefs of individuals to the beliefs of groups as well.

Morally, the answer matters. For example, we might want to hold a government, a business, or a church to account for its potentially discriminating decision on a sensitive matter. Equally, we might want to applaud a charity, a think tank, or a university for its declaration of an inclusive position. In such cases the body is treated as a belief-forming group, not merely a set of individuals; else ascribing moral responsibility to the body doesn’t make sense.

The point of contention for philosophers is how autonomous a group’s belief is from its members’ beliefs. Summativists think (as a group 😉) that the belief of a group is a function of its members’ beliefs. The belief may be drawn by majority vote, the similar reasons given by its members, or the shared causes of their beliefs. Non-summativists disagree altogether.

A joint commitment between members of a group can give rise to group beliefs which no member possesses. For instance, a vote may end in a course of action which none of the members had as their first choice.

Dismissing the notion of group belief should be done cautiously: problematic views may be allowed to take refuge behind a denial. Take systemic problems within a group (e.g., sexism within law-enforcement; institutional racism within the press; a lack of environmental concern within a company). Though very few of the group’s members (politicians; journalists; directors) may hold the exact belief in question, a problematic group belief arguably is there; and we might not be able to deal with the problem properly if we deny its existence.

What do you think?

(Photo by Min An.)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Johnny Cash – ‘A Thing Called Love’

You can't see it with your eyes,

Hold it in your hand.

But like the wind, it covers our land,

Strong enough to move the heart of any man,

This thing called love.

But what is ‘This thing called love’ you describe, Johnny?

Read more about love in our latest article.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Philosophy of Love

What is love?

‘Is this love or am I dreaming? This must be love 'cause it's really got a hold on me’ (Whitesnake – ‘Is This Love’). Case closed.

No, seriously, we are back with our first long-read in a while and in it we ask what form love takes and who—and what—is able to feel it (feat. Rilke, Kant, Sartre, and Badiou).

Read the article here.

#philosophy#blog#original content#the human front#love#relationships#companionship#romantic#partners#date#phenomenology#transcendence#reason#truth#desire#experience#biology#realism#animals#evolution#society#philosophy memes#whitesnake#philosophyblr#philoblr

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mount Analogue

Here we bring to you a potent discussion on death and identity from Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing by René Daumal, described as follows:

‘In this novel/allegory the narrator/author sets sail in the yacht Impossible to search for Mount Analogue, the geographically located, albeit hidden, peak that reaches inexorably toward heaven. Daumal's symbolic mountain represents a way to truth that "cannot not exist," and his classic allegory of man's search for himself embraces the certainty that one can know and conquer one's own reality.’

In the passage below Father Sogol begins; the narrator replies.

‘With a little money in this galloping civilization of ours one can easily obtain the basic physical satisfactions. The rest is fraud. Fraud, ticks, and tricks — there's our whole life, from diaphragm to cranium. My Superior was right: I suffer from an incurable need to understand. I don't want to die without having understood why I lived. What about you? Have you ever been afraid of death?’

In silence I hunted around among my memories, deep memories where words had never before pried. And I spoke with difficulty. ‘Yes. When I was around six I heard something about flies which sting you when you're asleep. And naturally someone dragged in the old joke: “When you wake up you're dead.” The words haunted me. That evening in bed with the light out, I tried to picture death, the “no more of anything”. In my imagination I did away with all the outward circumstances of my life and felt myself confined in ever-tightening circles of anguish: there was no longer any “I” … What does it mean “I”? I couldn’t succeed in grasping it. “I” slipped out of my thoughts like a fish out of the hands of a blind man, and I couldn’t sleep. For three years these nights of questioning in the dark recurred fairly frequently. Then, on one particular night, a marvellous idea came to me: instead of just enduring this agony, try to observe it, to see where it comes from and what it is. I perceived that it all seemed to come from a tightening of something in my stomach, as well as under my ribs and in my throat. I remembered that I was subject to angina and forced myself to relax, especially my abdomen. The anguish disappeared. When I tried again in this new condition to think about death, instead of being clawed by anxiety, I was filled with an entirely new feeling. I knew no name for it — a feeling between mystery and hope.’

‘And then you grew up, went to school, and began to “philosophize”, didn't you? We all go through the same thing. It seems that during adolescence a person's inner life is suddenly weakened, stripped of its natural courage. In his thinking he no longer dares stand face to face with reality or mystery; he begins to see them through the opinions of “grown-ups”, through books and courses and professors. Still, a voice remains which is not completely muffled and which cries out every so often — every time its gag is loosened by an unexpected jolt in the routine. The voice cries out its great questioning of everything, but we stifle it again right away. Well, we already understand each other a little. I can admit to you that I fear death. Not what we imagine about death, for such fear is itself imaginary. And not my death as it will be set down with a date in the public records. But that death I suffer every moment, the death of that voice which, out of the depths of my childhood, keeps questioning me as it does you: “Who am I?” Everything in and around us seems to conspire to strangle it once and for all. Whenever the voice is silent — and it doesn’t speak often — I’m an empty body, a perambulating carcass. I’m afraid that one day it will fall silent forever, or that it will speak too late — as in your story about the flies: when you wake up, you’re dead.’

Did you feel that, too?

#philosophy#death#existentialism#identity#mount analogue#mountaineering#literature#novel#searching#absurd#life#meaning#pataphysics#mystic#allegory#surrealism#spiritual#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Being natural

We often speak about things being ‘natural’ or ‘more natural’ than other things. But what does this claim amount to? What does it mean to be natural?

Natural kinds

The concept of natural kind may be of service to us.

Something is of a natural kind if it can be grouped according to the structure of the natural world. The natural world can be ‘carved at the joints’ (Plato). Good theories, then, cut nature along these joints. Physics, for example, has it that electrons (meat) belong to the natural kind of fundamental particles.

Not so fast

However, human beings have blurred the boundaries of naturalness; for our actions and nature are in a constant interplay. At what point should something be considered artificial or arbitrary instead of natural?

Given our inquisitive and creative ways, we have used technology to synthesise vitamin C and new chemical elements (e.g., einsteinium [Es]). We have created ideal conditions for viruses (e.g., COVID-19) to spread globally—a virus which mutates via us. And while plants (e.g., GMO foods) can be grown from natural resources and share biological attributes with ‘wild’ flora, we have manipulated their DNA.

Are none of these examples natural in your eyes?

Philosophy to the rescue?

It’s tempting to think that only mind-independent things, entirely free of human involvement, are natural. But this approach eliminates a lot. Perhaps some metaphysics and philosophy of science can help us tighten up the definition.

For David Lewis there are ‘perfectly natural’ properties, like those described in physics and laws of nature; they are fundamental, simple, and intrinsic. But less-than-perfectly-natural things also exhibit degrees of naturalness; they are just more complex and abundant.

A more-liberal conception of naturalness is available in the work of Quine, whose natural kinds merely share natural properties. The scope of these natural kinds, however, is liable to becoming enormous. For example, if liquid is a natural kind, we haven’t exactly carved nature at the joints; a huge number of items fit this description.

Of course, philosophy didn’t rescue us.

⁂

A helpful concept here is social construction.

Humans causally construct things (e.g., money) which are real but whose existences aren’t inevitable; for they are contingent on human decision-making. They are not natural but social kinds.

But we also constitutively construct things. These are things which necessarily stand in relations to human features and activity.

Take black and woman as two potential human kinds. Are they autonomously real, are they socially constructed, or are they both? While each is said to instantiate its own collection of biological properties, parts of their realities seem to depend on aspects of human culture, such as oppression and privilege, as well as causal factors, such as geography and gender norms.

(Pictured: What of nature survives the influence of ‘man’? [Francesco Paggiaro/Pexels])

#philosophy#nature#natural#metaphysics#philosophy of science#science#natural kinds#social ontology#sociology#ontology#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zombies

Do you believe in zombies? No, not those zombies. Philosophical zombies. They look just like people. In philosophical terms, they are physically identical to us. They have brains, blood flows around their bodies, they laugh at appropriate times, and if you pinch them, they are likely to say ‘Ow!’ Functionally, they are indistinguishable. However, they lack consciousness.

Most of us hope neither kind of zombie exists outside of fiction. While the place of regular zombies is in stories (usually horror), the place of philosophical zombies is in thought experiments (usually in philosophy of mind).

Now here’s why they matter: how do you prove that somebody—even somebody you’ve known for your entire life (e.g., a friend or someone with whom you’re in love)—is not a philosophical zombie?

Sure, you can sense the signals of their body (e.g., the sounds it makes, the light it reflects, the odours it gives off). But on what basis is your experience of them indicative of theirs?

Maybe you deduce mental life in them by analogy to yours. However, this takes a Cartesian leap of faith; for what is your philosophical argument? (Wittgenstein speaks of experience as a ‘beetle in the box’ which can only be inferred in someone else and not articulated, given private language’s inaccessibility.)

Maybe you can send them to a neurophysiologist to find ‘correlates of consciousness’; but this won’t prove experience alone.

In short: in your experience, yours is the only consciousness you are directly aware of.

And here’s the point: if we conceive of philosophical zombies as a logical possibility and believe that humans are distinguishable from them, it follows that we should refute physicalism as a means of explaining consciousness (David Chalmers). Why?

The very conceivability of zombies undermines explanations of consciousness in physicalism’s terms. (Remember, zombies share all our physical features.) We need something else to tell us apart from zombies since physicalism fails to show we are different.

The power of this argument, of course, rests on how conceivable we think zombies are. If you think zombies are conceivable, you have a problem in having no way of verifying others’ consciousness. If you don’t, you are burying your head in the non-philosophical sand until you come up with a reason why.

But what does this argument say about the power of philosophy?

⁂

Maybe it’s best not to think about zombies at all.

ED: Any zombies out there?

SHAUN: Don't say that!

ED: What?

SHAUN: That.

ED: What?

SHAUN: That. The Z word. Don't say it.

ED: Why not?

SHAUN: Because it's ridiculous!

ED: [sighs and rolls his eyes] All right … Are there any out there, though?

— Shaun of the Dead (2004)

(Pictured: Zombies may imitate a smile but do they do not experience happiness. [cottonbro/Pexels])

#philosophy#zombies#mind#qualia#david chalmers#ludwig wittgenstein#physicalism#shaun of the dead#film#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Philosophy as “Great Art” - an Interview with Sophie Grace Chappell’

Exciting news: we just published our interview with Sophie Grace Chappell, the author of over 100 articles and the UK’s only transgender philosophy professor!

What’s her tip for getting into philosophy?

‘Read, read, read, read, read. When you’re doing philosophy, reading is the petrol in the tank; if you don’t read, you’re not going anywhere.’

And how does she assess the current situation for trans people in the UK?

‘This lack of visibility makes it too easy for transgender people to be monstered—we become a dark vague threat that no one actually knows, not people with faces but a “woke mob” or shadowy semi-criminalised lurkers in the Ladies’.’

Read the interview here.

#philosophy#blog#original content#the human front#interview#academia#academic#ancient greece#greeks#classics#literature#history#trans#transgender#lgbt#lgbtq#philosopher#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

7 notes

·

View notes