Text

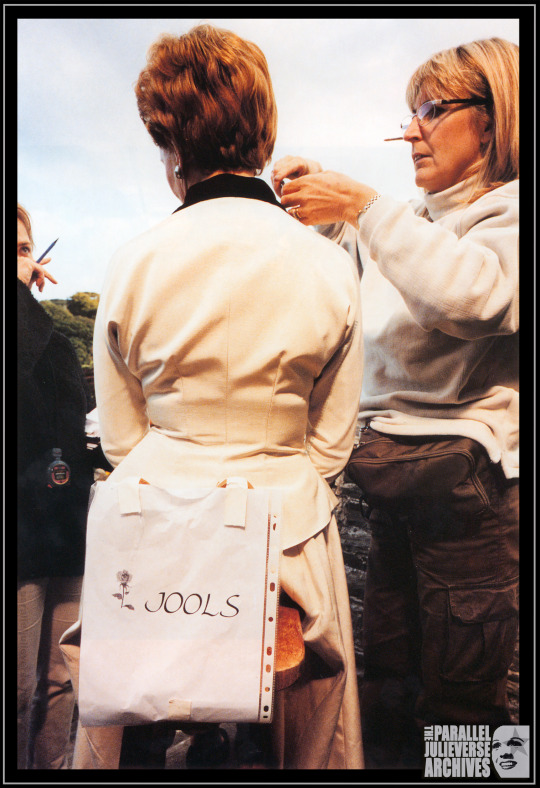

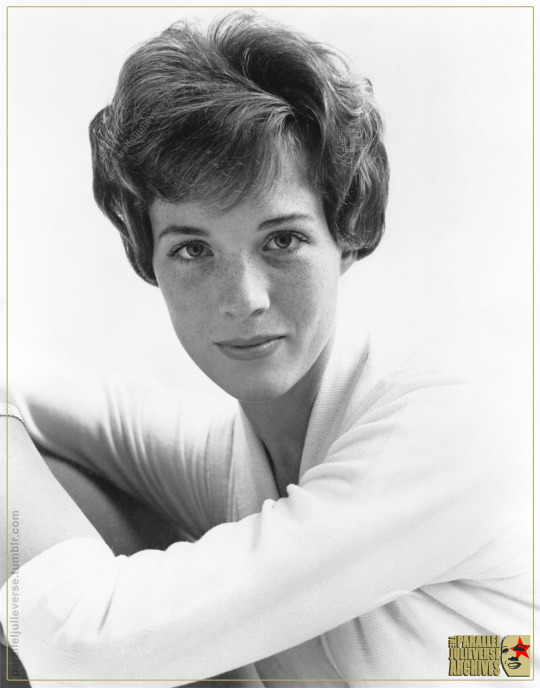

From the Archives: Julie Andrews on the set of Relative Values

Photographs by Greg Williams

July/August 1999, Isle of Man

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

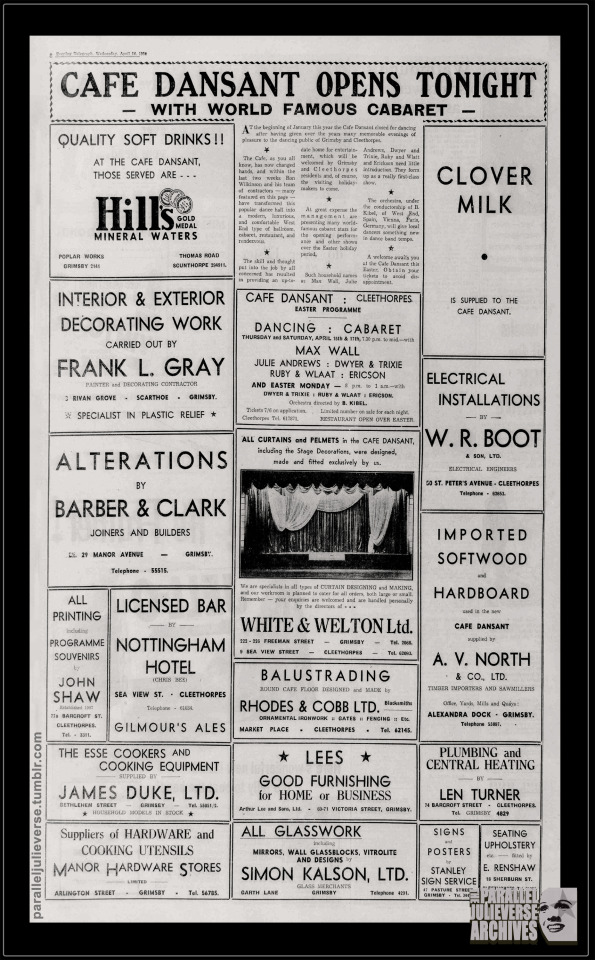

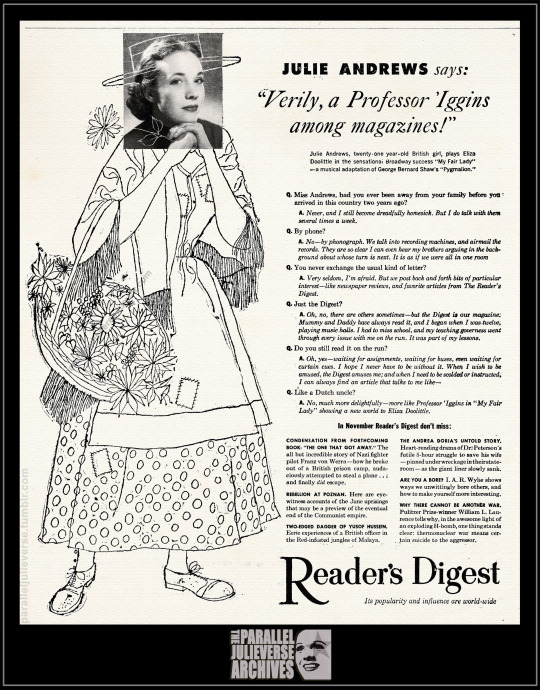

Come taste the wine... : 70th anniversary of Julie Andrews's 'cabaret debut' at the Café Dansant, Cleethorpes,

3 performances

Easter, 14-17 April, 1954

This week, seventy years ago, Julie Andrews made her official 'cabaret debut' at the Café Dansant in Cleethorpes. While not a major milestone in the traditional sense -- and one that seldom features in standard Andrews biographies -- the Cleethorpes appearance was nevertheless a significant event in the star's early career.

For a start, it was Julie's first appearance in cabaret -- the theatrical genre that is, not the Broadway musical which is a whole other Julieverse story. Characterised by sophisticated nightclub settings with adult audiences watching intimate performances, cabaret emerged in fin-de-siècle Paris before expanding to other European cities such as Berlin and Amsterdam (Appignanesi, 2004). Imported to Britain in the interwar years, cabaret offered a more urbane, adult alternative to the domestic traditions of English music hall and variety with their family audiences and jolly communal spirit (Nott, 2002, p. 120ff).

Julie's debut in cabaret was, thus, a significant step in her professional evolution towards a more mature image and repertoire. By 1954, Julie was 18, and well beyond the child star tag of her earlier years. Under the guidance of manager, Charles Tucker, there was a calculated strategy to reshape her stardom towards adulthood.

The maturation of Julie's image had begun in earnest the previous summer with Cap and Belles (1953), a touring revue that Tucker produced as a showcase for Julie, comedian Max Wall, and several other acts under his management. Cap and Belles afforded Julie the opportunity to shine with two big solos and a number of dance sequences. Much was made in show publicity of Julie's new "grown up" look, including the fact that she was wearing "her first off-the-shoulder evening dress" ('Her First Grown-Up Dress', 1953, p. 4).

The Cleethorpes cabaret was a further step in this process of transformative 'adulting'. Indeed, it was something of a Cap and Belles redux. Not only was Max Wall back as headline co-star, Julie even wore the same 'grown up' strapless evening gown. In keeping with a cabaret format, though, Julie was provided a longer solo set where she sang a mix of classical and contemporary pop songs including "My Heart is Singing", "Belle of the Ball", "Always", and "Long Ago and Far Away" ('Cabaret opens', 1954, p. 4).

That Julie should have chosen Cleethorpes for her cabaret debut might seem odd to contemporary readers. Today, this small town on the north Lincolnshire coast is largely regarded as a somewhat faded, out-of-the-way seaside resort. In its heyday of the mid-twentieth century, however, Cleethorpes was a vibrant tourist hub that attracted tens of thousands of holidaymakers each year (Dowling, 2005). With several large theatres and entertainment venues, Cleethorpes was also an important stop in the summertime variety circuit, drawing many of the era’s big stars and entertainment acts (Morton, 1986).

The Café Dansant was one of Cleethorpes' most iconic nighttime venues, celebrated for its elegant suppertime cabarets and salon orchestras. Opening in the 1930s, the Café was a particularly popular haunt during the war and post-war era when servicemen from nearby bases danced the night away with locals and visiting holidaymakers to the sound of touring jazz bands and crooners (Dowling, 2005, p. 129; Ruston, 2019).

By 1954, the Café was starting to show its age, and incoming new management decided to shutter the venue for several months to undertake a luxury refurbishment (‘Café Dansant closed', 1954, p. 3). A gala re-opening was set for the Easter weekend of April 1954, just in time for the start of the high season (‘Café Dansant opens', 1954, p. 8).

Opening festivities for the Café kicked off with a lavish five hour dinner cabaret on the evening of Wednesday, 14 April. Julie was “one of the world famous cabaret stars" booked for the gala event, and she received considerable promotional build-up in both local and national press (‘Café Dansant opens', 1954, p. 8). There was even a widely circulating PR photo of Julie boarding the train to Cleethorpes at London's Kings Cross station.

In the end, Max Wall was unable to appear due to illness, and Alfred Marks -- another Tucker artist and former variety co-star of Julie's (Look In, 1952) -- stepped in at short notice. Rounding out the bill were several other minor acts, including American dance duo, Bobby Dwyer and Trixie; novelty entertainers, Ruby and Charles Wlaat; and magician Ericson who doubled as cabaret emcee.

Commentators judged the evening a resounding success. The "Cafe Dansant has got away to a flying start, after probably the biggest opening night ever seen in Cleethorpes," effused one newspaper report (Sandbox, 1954, p.4). Special mention was made of Julie who “received a great reception when she sang a selection of old and new songs, accompanied at the piano by her mother” (‘'Café Dansant reopening’, 1954, p. 6).

Following her performance, Julie joined the Mayor of Cleethorpes, Mr Albert Winters, in a cake-cutting ceremony and mayoral dance. Decades later, Winters recalled how he still “savour[ed] the memory of snatching a dance with the young girl destined to be a star… [S]he seemed very slim and frail,” he reminisced, “but she was a great dancer and I thoroughly enjoyed myself” (Morton, 1986, p. 15).

Julie stayed on in Cleethorpes for two more performances on Thursday 15 and Saturday 17 April respectively, before returning to London with her mother on Easter Sunday, 18 April. The very next day she commenced formal rehearsals for Mountain Fire, Julie's first dramatic 'straight' play and another step in her professional pivot to more adult content (--also, time permitting, the subject of a possible future blogpost).

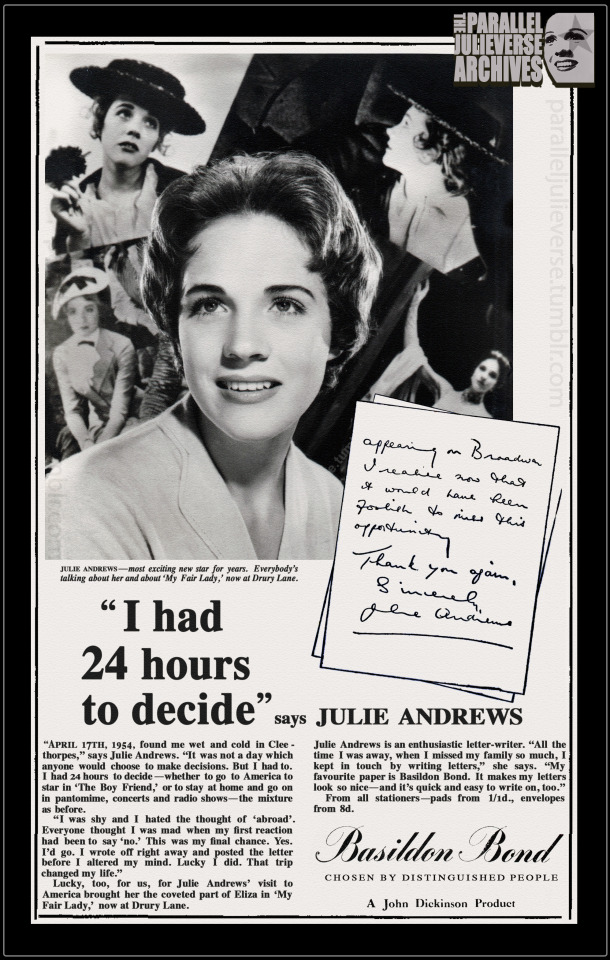

A final noteworthy aspect about the Cleethorpes appearance is that it was during this weekend that Julie made the momentous decision to go to America to star in The Boy Friend. In what has become part of theatrical lore, Julie had been offered the plum role of Polly Browne in the show's Broadway production sometime in February or March of 1954 while she was appearing in Cinderella at the London Palladium. To the American producers’ astonishment --- and manager Tucker’s horror -- Julie was initially reluctant to accept, fearful of leaving her home and family. She prevaricated for weeks. Finally, while she was in Cleethorpes, Julie was given an ultimatum and told she had to make her decision.

In her 1958 serialised memoir for Woman magazine, Julie recounts:

“Mummie and I went to Cleethorpes to do a concert. It was a miserable wet day. From our hotel I watched the dark sea pounding the shore with great grey waves. I was called to the downstairs telephone.

“Julie,” said Uncle Charles [Tucker]‘s voice from London, “they can’t wait any longer. You’ll have to make your mind up NOW.”

I burst into tears.

“I’ll go Uncle,” I sobbed, “if you’ll make it only one year’s contract instead of two. Only one year, please.” …

Against everyone’s judgment and wishes I got my way…None of us knew that if I’d signed for two [years], then I should never have been free to do Eliza in My Fair Lady. And never known all the happiness and success it has brought me” (Andrews, 1958, p. 46).

The Cleethorpes ultimatum even found its way into an advertising campaign that Julie did for Basildon Bond stationery in 1958/59, albeit with the telephone call converted into a letter for enhanced marketing purposes. Framed as a choice between going to America and the “trip [that] changed my life” or staying at home in England “and go[ing] on in pantomime, concerts, and radio shows—the mixture as before,” the advert highlighted the “sliding door” gravity of that fateful Cleethorpes weekend (Basildon Bond, 1958). What would the course of Julie's life been like had she said no to Broadway and opted to remain in the UK?

It is a speculative refrain that Julie and others have made frequently over the years. “If I’d stayed in England I would probably have got no further than pantomime leads,” she mused in a 1970 interview (Franks, 1970, p. 32). Or, more dramatically: “Had I remained in London and not appeared in the Broadway production of The Boy Friend…who knows, I might be starving in some chorus line today” (Hirschorn, 1968).

In all seriousness, it's doubtful that a British-based Julie would have faded into professional oblivion. As biographer John Cottrell quips: "that golden voice would always have kept her out of the chorus” (Cottrell, 1968, p. 71). Nevertheless, Julie's professional options in Britain during that era would have been greatly diminished. And she certainly wouldn't have achieved the level of international superstardom enabled by Broadway and Hollywood. Who knows, in a parallel 'sliding door' universe, our Julie might have gone on playing cabarets and end-of-pier shows in Cleethorpes...

Sources

Andrews, J. (1958). 'So much to sing about, part 3.' Woman. 17 May, 15-18, 45-48.

Appignanesi, L. (2004). The cabaret. Revised edn. Yale University Press.

Basildon Bond. (1958). 'I had 24 hours to decide, says Julie Andrews'. [Advertisement]. Daily Mirror. 6 October, p. 4.

'Cabaret opens Café Dansant." (1954). Grimsby Daily Telegraph. 15 April, p. 4.

‘Café Dansant closed.' (1954). Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 28 January, p. 3.

‘Café Dansant opens tonight – with world-famous cabaret’. (1954). Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 14 April, p. 8.

‘Café Dansant reopening a gay affair.’ (1954). Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 15 April, p. 6.

Cottrell, J. (1968). Julie Andrews: The story of a star. Arthur Barker Ltd.

Dowling, A. (2005). Cleethorpes: The creation of a seaside resort. Phillimore.

'Echoes of the past, the old Café Dansant'. (2009). Cleethorpes Chronicle. December 3, p. 13.

Frank, E. (1954). Daily News. 15 April, p.6.

Franks, G. (1970). ‘Whatever��s happened to Mary Poppins?’ Leicester Mercury. 4 December, p. 32.

'Her first grown-up dress.' (1953). Sussex Daily News. 28 July, p. 4.

Hirschorn, C. (1968). 'America made me, says Julie Andrews.' Sunday Express. 8 September, p. 23.

Morton, J. (1986). ‘Where the stars began to shine’. Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 22 September, p. 15.

Nott, J.J. (2002). Music for the people: Popular music and dance in interwar Britain. Oxford University Press.

Ruston, A. (2019). 'Taking a step back in time to the Cleethorpes gem Cafe Dansant where The Kinks once played'. Grimsby Live. 12 October.

Sandboy. (1954). 'Cleethorpes notebook: Flying start.' Grimsby Evening Telegraph. 19 April, p. 4.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Headline: Iconic Street Artist Unmasked: Dame Julie Andrews Revealed as the Mastermind Behind Banksy's Artistry

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

LONDON, April 1, 2024 (PJV NEWSWIRE) -- In an astonishing turn of events that has rocked the art world to its core, Dame Julie Andrews, the celebrated singer, actress and star of family classics like Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music, has been unveiled as the creative mastermind behind the enigmatic street artist, Banksy.

The shock revelation was announced by a team of international researchers at the Tate Modern in London. Head researcher and world-renowned Banksy expert, Professor Savant of Whangdoodle University, explained that the team initially set out to map the geographical patterns of Banksy's work, but noticed an intriguing overlap with the locations of Dame Julie's UK appearances over the years.

Further investigation uncovered a series of coded messages hidden within Banksy's artworks that, when deciphered, spelled out various Andrews references. The celebrated Bansky stencil "Girl with Balloon" revealed a sequence of tiny numbers in the balloon string that corresponded to ASCII values spelling "How do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?". "Kissing Coppers" contained an anagrammatic mix of letters on the policemen's epaulettes that unscrambled to read, "The constable's responstable..."

The smoking gun came when researchers discovered a hidden subterranean studio deep beneath the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, containing stencils, spray cans, and a collection of Andrews' vinyl records. Here the team located an early draft version of Banksy's "Flower Thrower" where the famous bouquet was a posy of edelweiss.

The revelation that Dame Julie is the hand behind the elusive graffiti superstar has stunned the entertainment and art worlds alike with critics scrambling to reevaluate the combined Andrews-Banksy oeuvre. Professor Savant discerns a deep, thematic link between Banksy's provocative street murals and Andrews' film characters, both of which challenge societal norms with a mix of whimsy and sharp commentary.

And the Banksy pseudonym? Savant believes it is a nod to the name of the family transformed by Andrews as the eponymous flying nanny in Mary Poppins. Just as Poppins upended the repressive Edwardian world of Mr Banks with her magical carpet bag of tricks, Andrews as Banksy has been sprinkling another brand of subversive mischief across the urban landscapes of the modern world.

Dame Julie Andrews has yet to make an official statement, but a source close to the star says, "Julie has always had a flair for the dramatic and she constantly seeks new outlets for her creative voice, so it's not all that surprising that she would take it to the streets!"

THIS IS A BREAKING NEWS STORY. FURTHER DETAILS TO FOLLOW.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

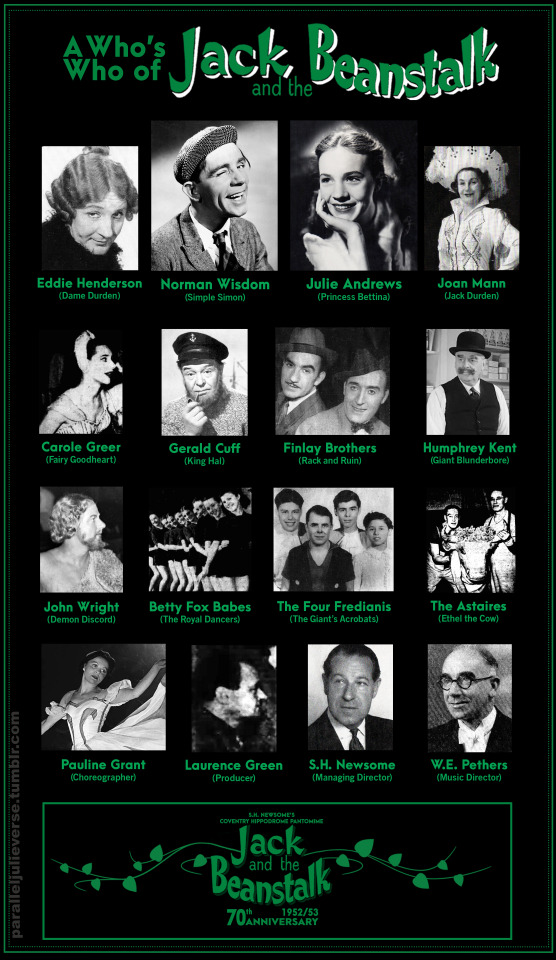

From the PJV Archives: 20th Century Fox...and the Summer of Love

In the summer of 1967, 20th Century Fox was riding high on the waves of extraordinary commercial success. Their 1965 release, The Sound of Music, was the biggest grossing film of all time and the studio coffers were overflowing. With a lineup of promising blockbuster productions in the works, the studio organised a high-profile PR junket where theatre exhibitors from across the United States and abroad were flown to Hollywood for an "open house" visit.

This souvenir foldout map, a memento from the event, vividly captures the studio's breezy confidence. Rendered in hyper-energetic cartoon style, it shows Fox films dominating the North American continent from sea to shining sea. Crowds everywhere throng to Fox theatres, their enthusiastic sentiments captured in comic speech bubbles. Even aliens from outer space are featured in the studio's vision of cultural ascendancy!

That this glorious Hollywood summer would soon enough turn to a winter of discontent is a matter of historical record. The youth-driven counter-cultural revolution unfolding on the streets of San Francisco that summer would quickly transfer to the nation's movie houses. Later that year, smaller edgier films like Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Graduate (1967) emerged to lead the charge of the New Hollywood and, almost overnight, Fox's big roadshow offerings like Doctor Dolittle and STAR! would be deemed old-fashioned and out-of-touch.

Still, for one final "fun summer", there was nary a cloud on the 20th Century Fox horizon..!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The renowned Canadian director Norman Jewison has passed away at the age of 97. While most people remember Jewison for his outstanding work as the award-winning director of major Hollywood hits like In the Heat of the Night (1967), Fiddler on the Roof (1971), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), and Moonstruck (1987), the versatile director actually began his career in television.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Jewison directed a series of highly acclaimed variety specials for CBS, featuring some of the era's biggest stars, including Judy Garland, Jackie Gleason, Harry Belafonte, and Danny Kaye. It was in this context that Jewison worked with our Julie on not one but two gala specials: The Fabulous Fifties (1960) and The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe (1962).

So, farewell, Mr Jewison, and thank you for your work.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

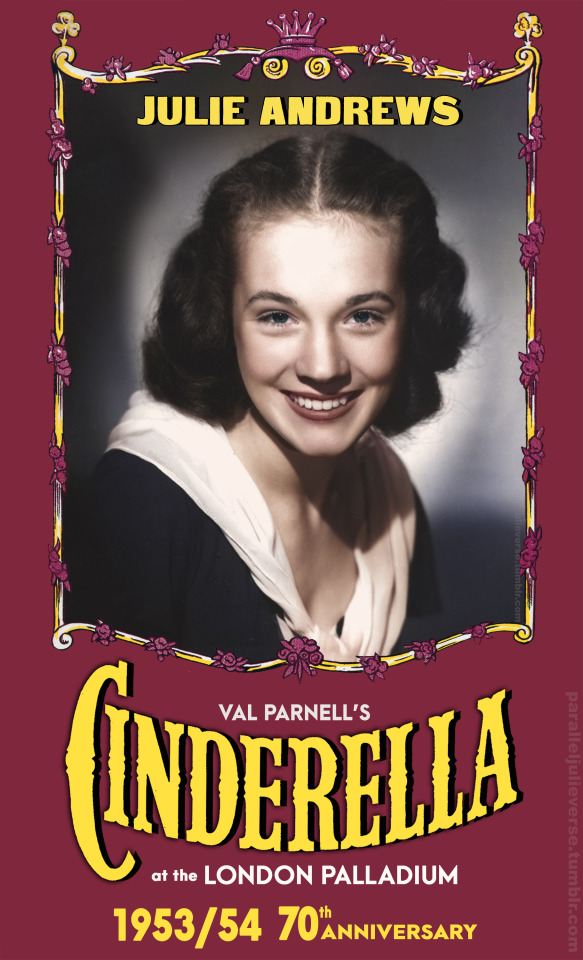

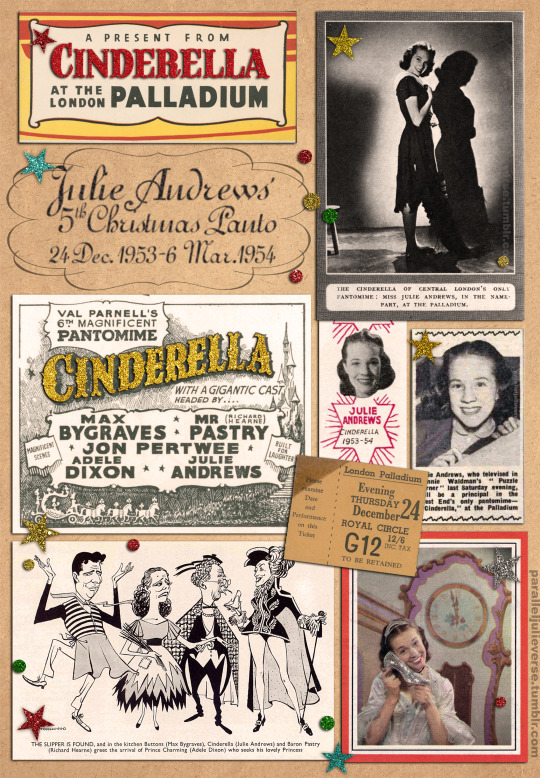

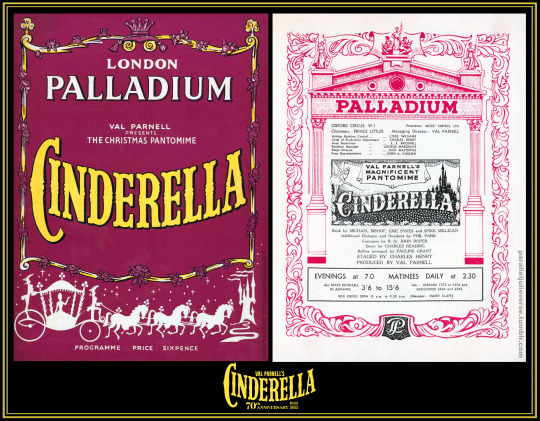

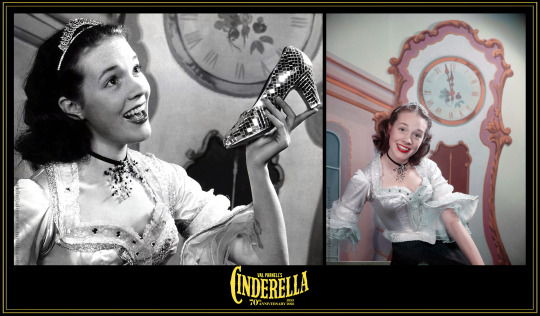

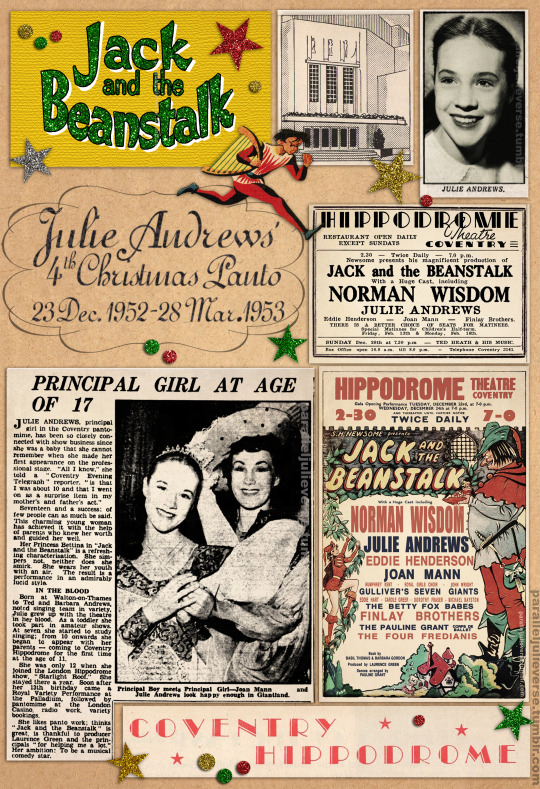

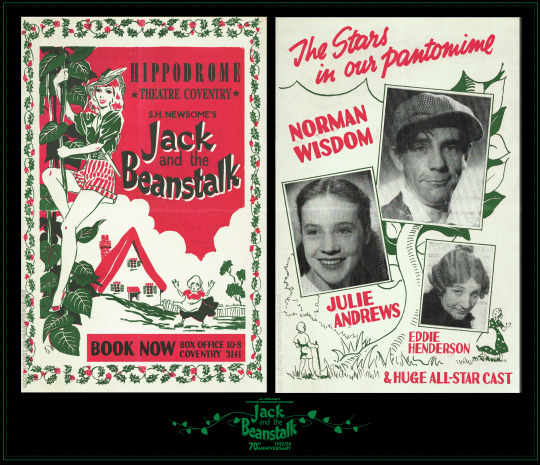

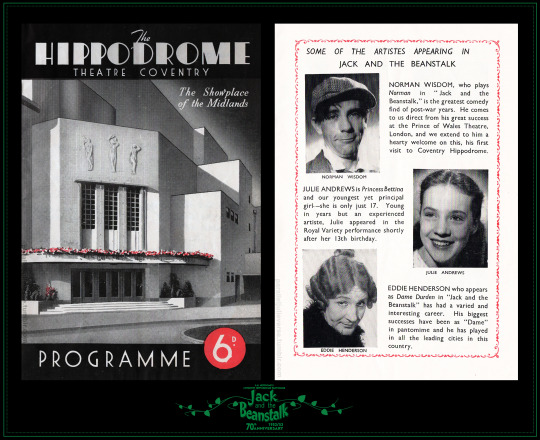

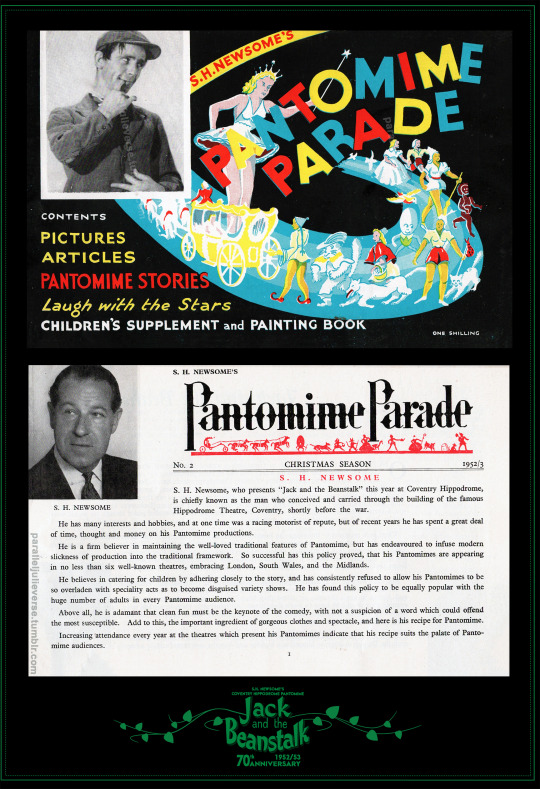

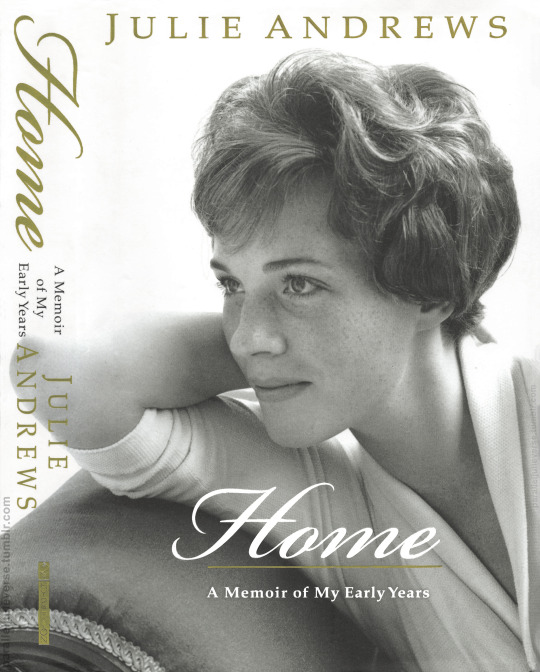

70th anniversary of Cinderella

London Palladium, 122 performances

(24 December 1953 - 6 March 1954)

This month marks the 70th anniversary of a milestone in the early career of Julie Andrews: the opening of Val Parnell's lavish Christmas pantomime, Cinderella, at the London Palladium on 24 December 1953.

Cinderella would be Julie’s fifth and final UK pantomime, following earlier runs in Humpty Dumpty (1948), Red Riding Hood (1950) Aladdin (1951), and Jack and the Beanstalk (1952). It was the biggest theatrical production Julie had yet undertaken and it would prove a turning point in the young star's career.

'No Pigtails for Julie'

By 1953, Julie was turning 18 and fast outgrowing the "infant prodigy" label of her early career. Efforts had been made for some time to update Julie's star image with a more mature look and an expanded musical repertoire. Much was made in the press about the new "[g]rown up now (or almost) Julie Andrews" (Bendle 1953: 2). "The tiny pigtailed schoolgirl who at age 13 sang in a Royal Command Performance," remarked one newspaper commentator, "is now a long-limbed attractive young lady who is wearing her first strapless dresses" (Pearce 1954: 6).

As an archetypal tale of girl-to-woman metamorphosis, Cinderella was an ideal vehicle with which to advance these transformative ambitions. It not only gave Julie titular 'principal girl' status, but called on her to assume a role of emotional nuance and adult sophistication.

Even Julie's mother, Barbara, is reported to have exclaimed:

“Julie, this is the perfect part for you at the perfect age. It couldn’t have come at a better time in your career" (Andrews 2008: 156-57).

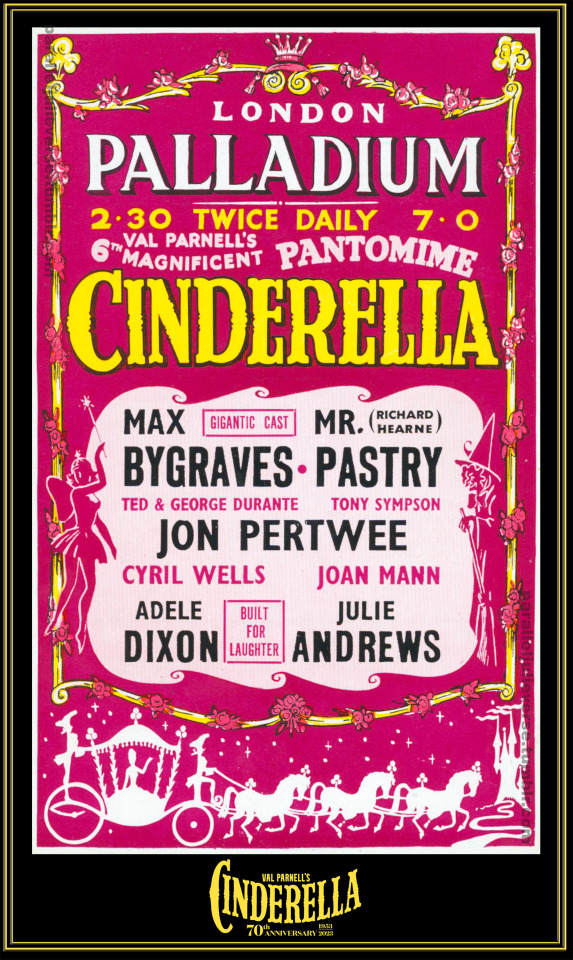

Val Parnell presents...

Underscoring the significance of Cinderella was the fact it was a Val Parnell production. Dubbed 'Britain's Mr. Show Business', Parnell was a hugely influential impresario who dominated the British entertainment scene for many decades. He had started in provincial variety management before progressively rising up the ranks to assume control of the prestigious Moss Empires theatre chain (Bullar & Evans 1950: 219). Later, Parnell would go on to play a significant role in the expansion of the British television industry as General Manager of ATV, the first commercial television network in the United Kingdom (Sendall 1982: 250).

Renowned for his astute promotion of new talent, Parnell had been instrumental in launching Julie's career when he cast her in her first professional show at just 12 years of age: the now legendary Starlight Roof at the London Hippodrome in 1947/48 (Alldridge 1954: 1). Cinderella would bring the two together again for the first time in six years. To hear Parnell tell the story, it was a reunion long in the making.

"From the moment [I] first heard her sing," he declared, I "made a mental note that one day [I] was going to present Julie Andrews as Cinderella." As he explained:

"So many child performers are inclined to be precocious...But Julie was not. She had that appealing simplicity which she still retains. It struck me at the time that she had all the qualities of an ideal Cinderella -- youth. freshness, charm" (Lanchbery 1954: 1).

At the London Palladium

Of all the theatres managed by Parnell, none was more celebrated than the London Palladium, a 2200 seat theatre noted for its opulent architecture and state-of-the-art stage facilities (Woodward 2009). Parnell's adept leadership propelled the Palladium to international acclaim as the most famous variety theatre in the world and a top drawcard for international stars. "To appear at the Palladium is the goal to which every artist strives," noted a 1957 newspaper commentary, "to appear at the Palladium is to have achieved star status!" (Hoddinott 1957: 4).

The Palladium was also an important venue for Christmas pantomimes. Under Parnell, the Palladium "became the home of spectacular pantomime" with audiences eagerly anticipating each year's offering (Baker 2014: 219). Parnell applied the same triumphant formula to the humble British panto that he used in his variety revues: a blend of star power, spectacle, and money.

Writing in 1952, Ian Beven chronicled Parnell's studied approach to his annual pantomime at the Palladium:

"Each year...Parnell has tried to produce something bigger and better than the year before...He starts in midsummer, with a bare stage. By the third week in December, he has spent about £25,000 on scenery, costumes, musical arrangements, script, and rehearsals...Running costs of the show are high, as Parnell is prodigal with talent and fills his stage with people, and there are only about 140 performances on which to make a profit; but there is no disguising the fact that pantomime in this manner is a highly remunerative proposition, for there is rarely an empty seat throughout the run" (Seven 1952: 223).

Val Parnell's Magnificent 'Cinderella'

Cinderella would be Parnell's sixth pantomime at the Palladium. It would also be the only fully-staged panto in the West End for the 1953 Christmas season. In a sign of the rapidly changing post-war theatre scene, most of the other major London houses were tied up with long-running musicals and plays, largely imported from America. In addition, arena-style ice spectaculars were increasingly in vogue with a slew of new-fangled pantos "on ice" scheduled for suburban venues, leading some wags to quip that Parnell should call his show "Cinderella on Wood" ('Old fashioned Val' 1953: 6).

While many lamented it as a sign of "the decline and fall of the honoured institution" of the traditional panto, the absence of competition gave Parnell a distinct commercial advantage ('At the Pantomime', 1954: 4). When pre-sales for Cinderella opened in the autumn of 1953, the booking office was inundated and the show would become the theatre's most successful pantomime to date (Alldridge 1954: 4).

It also spoke to Parnell's innate sense of theatrical traditionalism. Though he was certainly not averse to innovation and was quick to adopt state-of-the-art technologies, Parnell was a producer of the old school. He believed in sticking to the tried-and-true and giving audiences what they expected. "Audiences haven't changed at all," he opined, "Certainly not the Palladium audiences. It's the same as it ever was. People go the the theatre to enjoy themselves...My job is to give it to them in bigger and better shows" (Hoddinott, 1957: 4)

True to this crowd-pleasing philosophy, Parnell determined to make Cinderella his most spectacular panto yet. Planning for the show started early in 1953. "I always start pantomime with a bare stage," he declared, "Everything must be new" (Fagence 1958: 4). Heading the production team were two influential figures who were something of righthand men to Parnell: Charles Henry and Charles Reading.

Henry was Chief of Production at the Moss Empire chain for over thirty years. During his tenure, he would produce over 200 revues and pantomimes, as well as fourteen Royal Command Performances (Born & Frame 1960: 4; 'Charles Henry' 1959: 1). Known as a canny talent-spotter with an encyclopaedic memory -- Bud Flanagan famously called him "a blinking card index of comedy" -- Henry was fondly remembered by Parnell at his passing in 1968 as "one of the theatre's greatest backroom boys" and "my closest associate" (Evening Standard Reporter 1968: 17).

Reading was an equally trusted majordomo for Parnell. A true theatre polymath, Reading trained as an actor before expanding into production, direction, writing, and design. It was the latter talent that brought Reading initial fame with a series of innovative opera and ballet designs for Sadler's Wells and the Old Vic. He subsequently moved into designing more commercial fare in the West End and, in 1947, was contracted by Parnell as resident designer and production assistant at the Palladium (Barker 199: 20; Vallance 199: 36).

Together Parnell, Henry, and Reading set about staging Cinderella as an unparalleled spectacular. Set and costume design alone was budgeted at over £20,000, which equates to almost £700,000 in today's money (Webster 2013). Reading designed an intricate series of progressively spectacular sets, including a palatial Ballroom, a Cave of Crystal Lustres, and a Palace of Porcelain for the grand finale (V&A 2015).

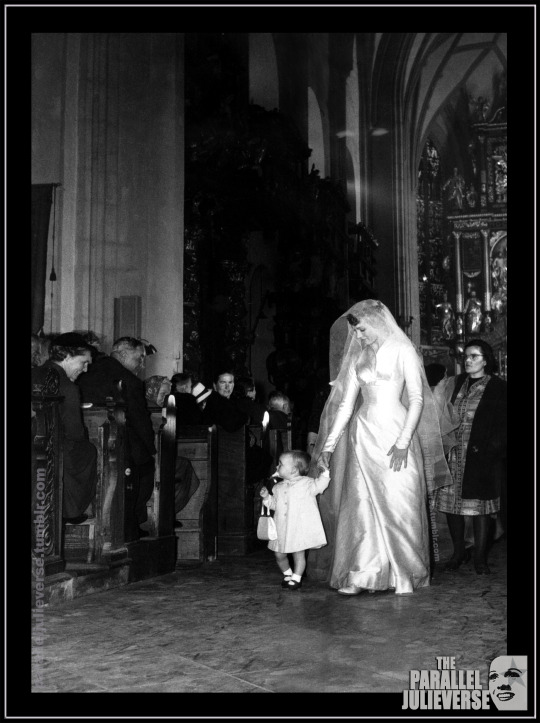

Famed stage couturier, Robert St John-Roper, designed a complementary suite of costumes including a dazzling ballgown and bejewelled wedding dress for Julie. In her 2008 memoir, Julie recalled the breathtaking splendour of it all:

"Everything about that 1953/1954 production of Cinderella had a certain elegance...The production values on the show were terrific; there were revolving stages, and real white ponies pulling the spectacularly gilded coach...In the grand finale wedding sequence, my crinoline was so huge that I had to arrive backstage dressed in my bodice, sleeves, and petticoat, and walk into the crinoline skirt, which was braced on a stand because it was so bejewelled and cumbersome. The company, Prince Charming, and I were brought up from below stage on a hydraulic elevator, to be revealed in a sparkling white set and costumes for the final tableau" (Andrews 2008: 155-57).

Spectacle, Humour, and Charm

Careful attention was equally paid to the other production elements of Cinderella to ensure a well-wrought work of quality theatrical entertainment. To write the script, Parnell commissioned a trio of talented young writers who were only then beginning to make a name for themselves but who would go on to become giants of British comedy: Eric Sykes, Spike Milligan, and Mike Bishop. Their original treatment hewed closely to the core elements of the well-known fairy story but embroidered with innovations and, true to panto style, comic flourishes.

In the Sykes et al script, the story opens with Baron Pastry of Stoneybroke Hall lamenting that he has fallen on hard times (Stoneybroke...get it?!). He lives with his beloved daughter, Cinderella, and their faithful but hopeless retainer, Buttons who carries an unrequited flame for Cinderella. The Baron announces he has just married a wealthy widow in the vain hope of restoring his fortune. She comes to the Hall with her two unloved and unlovable daughters -- the Ugly Stepsisters, of course -- and they set about making Cinderella's life a misery. The requisite Royal Ball, benevolent Fairy Godmother, and Glass Slipper hunt all ensue before the inevitable happily-ever-after ending (Sykes et al. 1953).

Woven around these well-worn plot points were a series of comic interludes designed to accomodate the pantomime conventions of audience participation and novelty acts. These ran the gamut from a demonic door and a bomb-toting spaceman ("it's behind you") to jive singing footmen and a giant electric washing machine that tumbled a hapless Baron Pastry along with an assortment of oversized clothes (Sykes et al. 1953).

Song and Dance

No pantomime would be complete without music and dance and Cinderella served both in abundance. Overseeing the musical side of things were another pair of Palladium panto stalwarts: Phil Park and Bobby Howell.

Park had been a star cinema organist during the picture palace era but, following the war, he turned his attention to composing and arranging. It was in this capacity that Park worked frequently for Parnell on his Palladium pantos which he "tailored to the stars appearing in the shows but always preserved the time-honoured tradition" ('Obituary: Phil Park' 1978: 6).

Bobby (aka Bobbie) Howell was a prominent band leader of the inter-war years, touring the cinema and dance circuits. After the Second World War, he became a musical director in the West End, working on a string of successful shows such as Strike a New Note, The Lisbon Story, and Piccadilly Hayride. He also worked as musical director and conductor on many of Parnell's pantomimes, including Cinderella ('Bobby Howell' 1962: 3).

In crafting the musical score for Cinderella, Park and Howell followed typical pantomime form of mixing existing well-known tunes with bespoke compositions. Many of the latter were written by Park including a humorous duet between Cinderella and Buttons (played by Max Bygraves). In this duet, Cinderella fantasises about a romantic future with the Prince, while Buttons humorously interjects with sardonic quips:

Cinders: There's a lady -- and she curtseys,

Who she is, I cannot guess.

She might be me, except that she

Has such a pretty dress.

And there's her handsome partner,

Who is he, do you suppose?

Buttons: All I see's a turkey,

With a whopping parson's nose!

Cinders: Now I see him very clearly,

With a smile upon his face;

I'm certain he's a Prince,

Because he bows with royal grace.

See now he takes her hand,

And lifts it gently to his lips!

Buttons: He looks like George Dawson,

With a plate of fish and chips!

In addition to the duets, Julie had two showcase solos in Cinderella: "Chasing Shadows", a 1935 torch song by Silver and Davis, and "Is it Any Wonder," a lilting pop ballad by Bob Hayes and Roy Rodde which had been a recent chart hit for Joni James.

Interestingly, both solos were modern pop standards and, thus, a marked departure from the light classical repertoire that had been Julie's stock-in-trade. She did get to do some limited coloratura trilling in the extended Transformation Scene at the climax of Act 1 where Strauss waltzes formed the musical accompaniment, but the strong emphasis on popular tunes was indicative of the strategic shift in Julie's image mentioned earlier.

A number of reviewers remarked that Julie didn't seem to do as much singing in Cinderella as they were expecting. She did, however, compensate with quite a bit of dancing -- more dancing in fact than she'd ever done in a professional context.

Not only was there the mandatory waltz with the Prince, but Julie had a solo dance early in Act 1. She was also a key part of the pre-intermission ballet sequence. Choreography for Cinderella was provided by Pauline Grant with whom Julie had worked so happily the previous year in Jack and the Beanstalk. Pre-show publicity photos showcased Julie's dance rehearsals with Grant, underscoring her now mature lithe figure and womanly style.

A Who’s Who of Cinderella

Alongside Julie, the cast of Cinderella was a roster of star names and variety notables:

Max Bygraves as Buttons: Born in 1922 in London, Bygraves was a versatile entertainer known for his Cockney persona, humorous storytelling, and sentimental singing. His endearing catchphrases and relaxed chummy style made him a beloved figure in British entertainment. Growing up in a modest family, he showed early signs of showmanship, encouraged by his prizefighter father. Bygraves left school at 14 and served in the RAF during WWII, where he began entertaining troops. His career took off post-war with various stage and radio appearances, including Educating Archie where he first performed alongside Julie. He made several films in the 1950s and his recordings, often nostalgic or comedic, were hugely popular. He continued performing internationally for many years, eventually settling in Australia. Recognised for his contribution to entertainment, he was awarded an OBE in 1982. He passed away in 2012 (Leigh 2012: 37).

Richard Hearne as Baron Pastry: Born in Norwich in 1909, Hearne came from a family with deep roots in music hall and circus arts, and he started performing on stage as a child. Hearne's career in variety and revue culminated in the creation of the beloved Mr. Pastry, a bowler-hatted, walrus-moustached character that brought him success in West End shows, pantomime, and TV, both in the UK and internationally. His role in Cinderella was effectively an adaptation of Mr Pastry complete with his signature comic dance, "The Lancers". A dedicated philanthropist, Hearne was a very active supporter of handicapped children and was honoured with an OBE in 1970 for his charity work. He passed away in 1979 ('Obituary: Richard Hearne', 1979: 27).

Adele Dixon as Prince Charming: Born in South London in 1908, Adele Dixon was a versatile performer known for her roles in London and Broadway musicals, Palladium pantomimes, and Shakespearean plays. After training at the Italia Conti Academy and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, she joined the Old Vic company. There, she shone in roles like Juliet and Ophelia. Dixon's transition to musical comedy in the 1930s made her a celebrated figure in the West End, admired for her red-gold hair, expressive brown eyes, and clear soprano voice. Her noteworthy performances included leading roles in Lucky Break, Anything Goes, and Over She Goes. Additionally, she appeared in the film Calling the Tune and became the first female performer on BBC Television in 1936. Dixon continued her success in post-war years with major hits like The Fleet's Lit Up and All Clear. She was also highly acclaimed as a Principal Boy in pantomimes, performing in these trouser roles 14 times throughout her career. Her portrayal of Prince Charming in the 1953 production of Cinderella marked her last appearance on the West End stage. While she continued to perform in provincial roles, health issues forced her into early retirement in the late 1950s. Dixon passed away in 1992 (Thornton, 1992: 29).

Joan Mann as Dandini: Welsh-born Mann trained as a dancer and started touring the variety circuit in her teens where she appeared on bills with stars including Max Miller and Tommy Trinder. A tall attractive brunette with a pleasant voice and shapely dancer’s legs, Mann was a perfect pantomime boy. She played opposite Julie in Jack and the Beanstalk (1952) and also toured with her as part of the musical revue, ‘Cap and Belles’ in 1953 (Andrews 2008: 146). Though she wasn't Principal Boy in Cinderella, Mann played the other leading pants role of Dandini, the Prince's Squire. Mann’s greatest fame came later as part of the celebrated Fols-de-Rols variety troupe with whom she performed for almost two decades. She also starred opposite Dame Anna Neagle in the hit West End musical, Charlie Girl in the late-1960s. Mann died in 2007 aged 87 (P.N., 2007: 53).

Jon Pertwee as Buttercup: Born in 1919, Pertwee was a versatile actor who left a significant mark in television, radio, theatre, and film. Educated at Sherborne, he belonged to a family of distinguished artists and made his acting debut in 1939 in Brighton. His notable wartime service on the HMS Hood led to a fruitful collaboration with Eric Barker in comedy writing and radio. Pertwee became a household name with his long-running role in the BBC radio series, The Navy Lark. He gained even greater international fame on television as the third Doctor Who from 1970 to 1975, and as Worzel Gummidge. Pertwee's career spanned over 100 films, including two Carry On movies, and numerous stage productions. In Cinderella, Pertwee took on the comic drag role of Buttercup, one of the Ugly Sisters. Pertwee passed away in 1996, leaving a legacy as a unique and memorable actor (Newley, 1996: 38).

Tony Sympson as Dandelion: Born in East London in 1907, Tony Sympson had a dynamic career in music and theatre. Initially trained as a choral scholar at St Clement Danes Church Strand, he made his stage debut as a specialty dancer in Dear Love. A mainstay character actor in West End theatre, he appeared in plays, musicals, revues, pantomimes, and operas. Sympson also featured in television ads where he earned a reputation for well-conceived characterisations. A pantomime regular, Sympson played the second of the Ugly Sisters, Dandelion, in Cinderella, a role he would repeat in subsequent productions. Sympson died in 1983 at the age of seventy-six (Marriott, 1983: 7).

Cyril Wells as Baroness Pastry: Born in Belfast in 1907, Wells' entry into acting was fortuitous. Initially a bank clerk, his passion for dancing led him to become a rehearsal partner for actress Jessie Matthews. This collaboration resulted in Wells being cast as her dance partner in the 1936 film It's Love Again, his only appearance on screen but a stepping stone into show business. He then featured in West End musical comedies like Order to View (1938), Here's Looking at Them (1939), and The Charcoal-Burner's Son (1939). Post-war, Wells shifted to comic roles in theatre and variety, notably in pantomime. In Cinderella, he played the Dame role of the blue-wigged Baroness. Wells passed away in 1958 in Southport, Lancashire ('Obituary: Cyril Wells', 1958: 9).

Ted and George Durante as the Broker's Men: One of several novelty acts to appear in Cinderella, the Durantes were a popular acrobat comic duo who found popularity on the post-war variety circuit. Contrary to their billing as brothers, the duo actually comprised two unrelated individuals, Ted Aston and George Mooney. They met in 1946 while performing as part of an acrobatic troupe and decided to branch out as partners, adopting the Durante surname at random. Their act ran for nine years till the late-1950s when Ted married and formed a new double act with his wife, becoming 'Ted and Hilda Durante'. This husband-and-wife team continued for many decades, becaming regulars on TV variety shows in the sixties and seventies (Wilmut, 1985: 182).

Elaine Garreau as the Godmother: Anglo-French actor Garreau, born in 1903, had an extensive and diverse career in British theatre, film, and television. She trained as a dancer, starting on the London stage at age 11 with a company of child artists. At 16, she was principal dancer at the Théâtre des Ambassadeurs in Paris and, at 20, understudy to the legendary Mistinguett. Returning to the UK, Garreau transitioned to acting and performed for many years in various London and provincial troupes across drama, comedy and musicals. Throughout the 40s and 50s, Garreau appeared frequently in pantomimes. In Cinderella, she took on the role of the magical Fairy Godmother. A few years later in 1958, Garreau would play again opposite Julie as part of the original London production of My Fair Lady, in the role of Lady Boxington. Garreau would remain with the show for over 10 years in both the Drury Lane and touring productions, racking up over 3,000 performances which was a world record. In her later career, Garreau increasingly appeared as a character actor in film and television. Garreau died in 2000 at the grand age of 97.

Silvia Ashmole as the Fairy Queen: Born in 1926, Ashmole enjoyed an idyllic childhood, travelling through Europe with her affluent parents and attending Cheltenham Ladies College. A trip with her mother to the ballet in London inspired Ashmole to take dancing lessons and, at age 16, she enrolled in the Cone-Ripman School of Dance, where she quickly excelled. Soon thereafter she secured a place in the coveted Royal Ballet (Sadler's Wells) and toured with them for several years. During a season at Glyndebourne, she met and eventually married the renowned Anglo-German opera director Peter Ebert. Ashmole continued her career as a dancer, often performing in operas at Glyndebourne and Edinburgh. She also worked frequently with choreographer Pauline Grant who contracted her to appear as the Fairy Queen in Cinderella (Wigglesworth 2018).

The Casavecchia Troupe as the Clowns: Billed as the "World's Greatest Comedy Tumblers," the Casavecchia Troupe was a team of acrobats who had worked individually in circus and variety before combining their talents. They toured widely in the UK variety circuit during the late-40s and early-50s. In Cinderella, they appeared as part of the Harlequinade sequence where their slapstick routine offered well-received comic relief.

William Barrett and Edna Busse as Harlequin and Columbine: Barrett and Busse were a pair of classically trained ballet dancers who danced the classic roles of Harlequin and Columbine in the Act 1 Harlequinade. Barrett was born in 1919 in Staffordshire and joined the Sadler's Wells Ballet company in the late-40s, touring with them to the US ('From Farm' 1954: 11). In the 60s and 70s, he performed in theatre and TV as a resident member of the Black and White Minstrel Show. He later retrained as a drama teacher and passed in 1995 (Jevons 1995: 29). Edna Busse was born in Melbourne in 1918. A protégé of Edouard Borovansky, she later honed her skills in London with Mathilde Kschessinska. Returning to Australia, she continued to perform, before transitioning into a revered ballet teacher. She passed in 2019, aged 100 (Yeo 2019).

The Aida Foster Babes: One of many companies of dancing juveniles popular in the era, the Aida Foster Babes were students of the Aida Foster Academy in Golders Green, London. Established in 1929, the Academy trained several generations of young hopefuls till ists closure in 1970, including several famous alumni such as Jean Simmons and Barbara Windsor ('End' 1970: 43). For Cinderella, Foster provided a group of 12 ‘babes’ who performed in several of the show’s lavish dance sequences.

Critical and Popular Reception

Cinderella was very well received by audiences and critics alike. The following excerpts give a sense of the uniformly glowing notices earned by the show, with particular mention of Julie:

Daily News: "Mr. Val Parnell has really done us proud. There can hardly be two more endearing comics than Max Bygraves and Richard Hearne. Julie Andrews, less operatic than I would have expected, is just the girl for Cinders, and she dances gracefully...a most spiffing pantomime" (E.F. 1953: 4).

The Tatler: "Cinderella has taste, beauty and elegance...But if there is more spectacle than of other good things who will complain, since the result...is so giddily splendiferous. The lighting and the costumes and the scenery could not better done...The principals are worthy of their splendiferous surroundings. Miss Adele Dixon has the right princely strut and Miss Julie Andrews, though she is less vocal than she was expected to be, makes Cinderella a young lady of character and charm" (Cookman 1954: 10).

Daily Mail: "Star names may shine all over the programme -- Max Bygraves and Richard Hearne here; Adele Dixon and Julie Andrews there -- but spectacle is the real star of Val Parnell's typically sumptuous pantomime. Instead of scuffling through the usual sleight-of-stagehand transformation scene Cinderella escapes from the kitchen by way of magic force, fairy spinning wheel, and luminous flying ballet to the cave of crystal lustres: a silvery-white vision as glittering as a wedding cake brush to life" (Wilson 1953: 4).

The Guardian: "Pantomime, though represented only by a single Cinderella in Central London, still flourishes...Cinders (Julie Andrews) croons before the dying kitchen fire...Max Bygraves and Richard Hearne use routine 'biz' to good effect...But what is really remarkable and characteristic of Pantomime 1953 is the standard of the ballet: the scene before Cinders goes off in her glittering coach is as smart, fast, extravagant and excitingly danced as a finale at the Moscow Opera" (F.B. 1953: 3).

The Observer: "The new Palladium Cinderella is magnificent to the eve and its Transformation Scene has fine taste as well as sumptuosity...Julie Andrews is a most attractive Cinderella but not so vocal as I expected" (Brown 1953: 6).

Daily Telegraph: "Cinderella...is up to the best Palladium standard. Elaborate spectacle and attractive dancing combine to delight one's eye. Adele Dixon is an admirable Prince Charming -- she has always been able to fill a big stage with her personality -- and Julie Andrews, kept oddly short of chances to sing, makes Cinderella a young lady of character and charm" (Darlington 1953: 7).

The People: "This is a grand and glamorous show with Julie Andrews as Cinderella. But it would have been grander still had they let her sing more. Adele Dixon constantly charms as the Prince. Max Bygraves and Richard Hearne provide a crescendo of laughs" (Shepherd 1953: 5).

The Times: "It is a hard fact for traditionalists to swallow that there is only one pantomime on the grand scale in the West End...yet if the dismayed traditionalists go the Palladium..., they will soon be cheered up....Here, it seems to say with complete confidence, is one of the few things in a changing world that have remained constant...The humour...is received with every sign of enjoyment and the romantic side of the show is from the first in good trim...Miss Adele Dixon and Miss Julie Andrews belong to the order of unobtrusively pleasant principles. They are an appealing pair, and they have in Mr. Max Bygraves an affable Buttons" ('The Palladium' 1953: 8).

The Stage: "Mr. Parnell has thrown everything into a demonstration of faith, assembling a director's dream of a cast and applying it to all the skill, experience and efficiency that have set the Palladium high in the world of entertainment. He lavishes talent and creative art, he employs every device of lighting, mechanical contrivance and novel effect that the theatre possesses, underlines it all with a defiant and traditional Harlequinade, and the result is the pantomime of pantomimes...Julie Andrews's fragile charm graces Cinderella's rags and raiments alike, and Adele Dixon's slim figure and are of intelligent humour are a delight" ('Christmas Shows' 1953: 5).

The Sketch: "It is the happiest panto-subject, and this is as happy a version as I remember. Richard Hearne in the bowels of a washing-machine, Adele Dixon and Julie Andrews to end rightly as Prince and Princess, Max Bygraves to chant 'Bighead!' -- here they all are, and Val Parnell has never had a spectacle more satisfying than the magical creation of coach and gown." (Trewin 1954: 18).

A Real-Life Cinderella

In many ways, Cinderella signalled something of a pinnacle for Julie's early British career. She was now a young woman in a starring role on the West End stage and, in professional terms, could scarcely go much further. Julie herself writes that "I felt that with Cinderella, my career had peaked" and whatever future she may have would be a continued cycle of "radio, vaudeville and pantomime" (Andrews 2008: 157).

But the theatre gods had other plans and a real-life Fairy Godmother materialised to change the course of Julie's life forever. Midway through the run of Cinderella, Julie was paid a backstage visit by Vida Hope, the producer of the smash hit London musical, The Boy Friend. There were plans to take the show to New York with a new company, but the producers were struggling to cast the lead role of Polly Browne. At the suggestion of Hattie Jacques, Julie's former co-star in Educating Archie, Hope went to see Julie in Cinderella and offered her the role.

It is part of theatrical lore that Julie was initially reluctant to accept the offer, but she was eventually persuaded to seize the opportunity (Andrews 2008: 157-58). Five months after the close of Cinderella, Julie flew off to New York and the rest, as they say, is history...

References:

Alldridge, John (1954). 'Oh, for another Gracie! says Mr Show Business.' Manchester Evening News. 12 October 1954: 1.

Andrews, Julie (2008). Home: A memoir of my early years. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

'At the Pantomime.' (1953). Belfast Telegraph. 30 December: 4.

Baker, Richard Anthony (2005). British Music Hall : An Illustrated History. Stroud: Sutton.

Barker, Dennis. (1999). 'Obituary: Charles Reaaing.' The Guardian. 19 May: 20.

Bendle, Alan (1953). 'Keeping a Straight Bat on a Sticky Wicket.' Manchester Evening News. 15 August: 2.

Bevan, Ian (1952). Top of the Bill: The Story of the London Palladium. London: Frederick Muller Ltd.

'Bobby Howell.' (1962) The Stage and Television Today. 8 February: 3.

Brown, Ivor (1953). "At the Theatre: Not on Ice." The Observer. 27 December: 6.

Bullar, Guy R. & Evans, Len (1950). The Performer: Who's Who in Variety. London: The Performer Ltd.

Cameron, Don (1958). 'The Val Parnell Story Parts 1-4'. The :

Chanticleer (1953). 'People: Old Fashioned Val.' Daily Herald. 3 November: 6.

'Charles Henry Resigning.' (1959). The Stage. 2 April: 1.

'Christmas Shows: The Palladium "Cinderella'".' (1953). The Stage. 31 December: 5.

Cookman, Anthony (1954). 'At the Theatre: Cinderella (London Palladium).' The Tatler and Bystander. 6 January: 10.

Cottrell, John (1968). Julie Andrews: The Story of a Star. London: Arthur Barker.

Darlington, W.A. (1953). "Christmas Shows: Modern Twist to Cinderella, Elaborate Show at Palladium." Daily Telegraph. 28 December: 7.

Double, Oliver (2012). Britain Had Talent: A History of Variety Theatre. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

E.F. (1953). 'A Most Spiffing Pantomime." Daily News. 28 December: 4.

Even Standard Reporter. (1968). 'Ex-Palladium Showman Dies.' Evening Standard. 28 February: 17.

Fagence, Maurice (1958). 'Curtain Up on Mr. Palladium'. Daily Herald. 17 February: 4.

F.B. (1953). "From a Nose in Egypt to Abandon in the Outer Suburbs." The Guardian. 28 December: 3.

Frame, Colin & Boorn, Bill. (1960). 'Palladium Nights.' The Birmingham Evening Mail. 9 November: 6.

Hoddinott, Derek (1957). 'Val Parnell Speaks". The Stage. 29 August: 4.

Lanchbery, Edward (1954). 'Teen-age Cinderella task to the CN: Julie Andrews' dream comes true.' Children's Newspaper. 16 January: 1.

Leigh, Spencer (2012). 'Obituary: Max Bygraves.' The Independent. 3 September: 37

Marriott, R.B. (1983). 'Obituary: Tony Sympson'. The Stage and Television Today. 21 April: 7.

Newley, Patrick. (1996). 'Obituary: Jon Pertwee'. The Stage. 23 May: 38.

'Obituary: Cyril Wells' (1958). The Stage. 17 April: 9.

'Obituary: Phil Park' (1978). The Stage and Television Today. 23 November: 6.

'Obituary: Richard Hearne' (1979). The Stage and Television Today. 30 August: 27.

Pearce, Emery (1954). “No Pigtails for Julie.” Daily Herald. 11 January: 6.

P.N. (2007). ‘Obituary: Joan Mann’. The Stage. 6 December: 53.

Ray, Ted (1956). 'Palladium Nights.' The Liverpool Echo. 27 October: 3.

Sean, Neil (2014). Live from the London Palladium: The World's Most Famous Theatre in the Words of the Stars Who Have Played There. London: Amberley Publishing.

Shepherd, Ross (1953). "London Holiday Shows." The People. 28 December: 5.

Sykes, Eric; Milligan, Spike; Bishop, Michael; and, Park, Phil. (1953). Val Parnell's Cinderella: For production at the London Palladium Xmas 1953. Moss Empires Ltd. [Manuscript held in the Lord Chamberlain's Plays Collection, British Library].

"The Palladium: Cinderella." (1953). The Times. 28 December: 8.

Thornton, Michael. (1992). 'Obituary: Adele Dixon.' The Stage. 4 June: 29.

Trewin, C.W (1954). "At the Theatre: Cinderella (Palladium)." The Sketch. 13 January: 18.

V&A (2015). 'Charles Reading.' V&A Theatre and Performance Collection. https://collections.vam.ac.uk.

Vallance, Tom. (1999). 'Obituary: Charles Reading.' The Independent. 17 June: 36.

'Variety Stage: Palladium Plans' (1953). The Stage. 17 September: 3.

Webster, Ian (2013). 'U.K. Inflation Calculator.' In2013dollars.com. https://www.in2013dollars.com/UK-inflation.

Wilmut, Roger (1985). Kindly leave the stage! : the story of variety, 1919-1960. London: Methuen.

Wilson, Cecil (1953). "Spectacle gets the star role." Daily Mail. 28 December: 4.

Woodward, Chris (2009). The London Palladium: The Story of the Theatre and its Stars. Huddersfield: Northern Heritage Pub.

©2023, Brett Farmer. All rights reserved.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Julie Andrews Story (BBC, 1976) Part 3: Star of the Sixties

The Parallel Julieverse is proud to present "The Julie Andrews Story", a special three-part radio profile produced by BBC Radio and first broadcast in January 1976.

Julie's relationship with BBC Radio traces back to her early days as a child performer in the 1940s and 50s when she lit up the airwaves as "Britain's youngest singing star". It's a testament to her enduring popularity that the national broadcaster continued to follow Julie's journey closely, crafting this rare gem of an audio profile in the mid-seventies. Based on original transcription recordings, this special video presentation offers the first chance to hear a programme that has lain dormant since its initial broadcast, half a century ago.

In "Star of the Sixties", the captivating finale to "The Julie Andrews Story", we journey with Julie through her skyrocketing ascent as an international film sensation, propelled by blockbuster titles like "Mary Poppins", "The Sound of Music", and "Thoroughly Modern Millie". We also delve into the unexpected failure of her subsequent big screen musicals, "Star!" and "Darling Lili", and witness her graceful pivot to television in the early 70s with the award-winning variety series, "The Julie Andrews Hour". Interviews with esteemed co-stars and collaborators, including Michael Craig, George Roy Hill, Daniel Massey, Beryl Reid, Nick Vanoff, and Robert Wise, shed further light on this fascinating period of Julie's career.

DISCLAIMER: This is a fan preservation project; it was created for criticism and research, and is completely nonprofit; it falls under the fair use provision of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. section 107. All materials used remain the property of the original copyright holders.

#julie andrews#hollywood#classic film#british#mary poppins#the sound of music#thoroughly modern millie#hawaii#musicals#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Julie Andrews Story (BBC Radio, 1976) Part 2: Hollywood, Here I Come!

The Parallel Julieverse is proud to present "The Julie Andrews Story", a special three-part radio profile produced by BBC Radio and first broadcast in January 1976.

Julie's relationship with BBC Radio traces back to her early days as a child performer in the 1940s and 50s when she lit up the airwaves as "Britain's youngest singing star". It's a testament to her enduring popularity that the national broadcaster continued to follow Julie's journey closely, crafting this rare gem of an audio profile in the mid-seventies. Based on original transcription recordings, this special video presentation offers the first chance to hear a programme that has lain dormant since its initial broadcast, half a century ago.

In "Hollywood, Here I Come", the second chapter of "The Julie Andrews Story", we follow Julie's continued triumphs on Broadway and the West End with hits like "My Fair Lady" and "Camelot", leading into her meteoric transition to film stardom in the mid-sixties. Through the eyes and voices of those who collaborated with Julie during this heady transformative era – including Martin Ransohoff, Richard Rodgers, the Sherman Brothers, Robert Stevenson, and Robert Wise – we gain a deeper appreciation for her extraordinary career.

DISCLAIMER: This is a fan preservation project; it was created for criticism and research, and is completely nonprofit; it falls under the fair use provision of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. section 107. All materials used remain the property of the original copyright holders.

#julie andrews#broadway#hollywood#classic film#musical theatre#musical#my fair lady#camelot#mary poppins#disney studios#the sound of music#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Julie Andrews Story (BBC Radio, 1976) Part 1: From Walton-on-Thames to the Great White Way

The Parallel Julieverse is proud to present "The Julie Andrews Story", a special three-part radio profile produced by BBC Radio and first broadcast in January 1976.

Julie's relationship with BBC Radio traces back to her early days as a child performer in the 1940s and 50s when she lit up the airwaves as "Britain's youngest singing star". It's a testament to her enduring popularity that the national broadcaster continued to follow Julie's journey closely, crafting this rare gem of an audio profile in the mid-seventies. Based on original transcription recordings, this special video presentation offers the first chance to hear a programme that has lain dormant since its initial broadcast, half a century ago.

But beyond the mere allure of rediscovery, this video breathes life into Julie's formative years. Titled "From Walton-on-Thames to the Great White Way", Part 1 of the "The Julie Andrews Story" traces Julie's tender years from her humble beginnings in Walton-on-Thames, through the bustle of the post-war variety and concert stages, right up to her dazzling Broadway debut in the 1950s.

Adding depth and dimension are the candid insights from those who stood shoulder to shoulder with Julie. The voices of Lilian Stiles-Allen, Barbara Andrews, Peter Brough, and many more shed light on Julie's meteoric ascent. Each interview weaves a tapestry that reveals fresh insights into the artist and the woman behind the legend.

So, sit back and journey with us, retracing the footsteps of Julie Andrews as she transitioned from a young English lass to Broadway's brightest star.

DISCLAIMER: This is a fan preservation project; it was created for criticism and research, and is completely nonprofit; it falls under the fair use provision of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. section 107. All materials used remain the property of the original copyright holders.

#julie andrews#broadway#west end#musical theatre#classic film#hollywood#british#walton on thames#Youtube

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

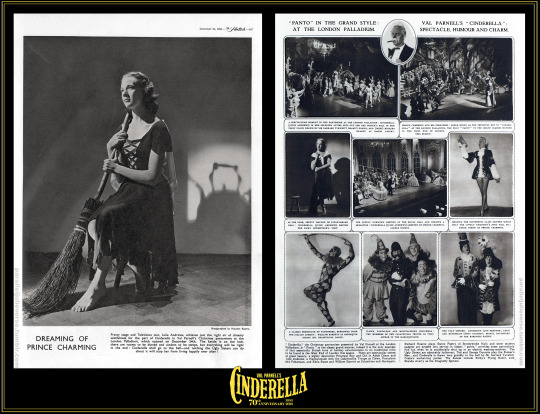

This Week in Julie History: Coronation Night Gala Supper Dance and All-Star Cabaret, Cumberland Hotel, 2 June 1953

Seventy years ago, in June 1953, London pulsated with the exhilarating energy of Coronation Week. Just as witnessed during the recent ascension of King Charles, crowds thronged the flag-bedecked streets of the capital, hearts ablaze with patriotic pride, waiting for a glimpse of their new young Queen Elizabeth II.

Numerous celebrations filled the Coronation Week of 1953, ranging from quaint neighbourhood street parties to grand, opulent balls. Almost every hotel and restaurant across the city curated special coronation-themed events. Among these, the Cumberland Hotel, located in the upscale Marble Arch district, offered a notable highlight with a magnificent Gala Supper Dance and Dinner.

Tickets for the gala were priced at 5 gns—approximately £200 in today's terms—so it was clearly a high-end affair. But for their money, guests were indulged with a gourmet six-course supper featuring suitably coronation-themed dishes such as Le blanc de poularde Reine Elizabeth -- Queen Elizabeth chicken breast -- served with Windsor Pearls and Royal Potatoes. Enhancing the experience, guests were also treated to a cocktail on arrival, half-bottle of vintage champagne and after-supper liqueurs.

A superbly curated All-Star Cabaret performance served as a delightful accompaniment to the evening's supper. Compered by celebrated magician, Billy McComb, it featured a line-up of top variety entertainers including comedian Reg Dixon; radio impressionist Peter Cavanagh, the singing duo, Jack and Daphne Barker, and ‘Britain’s youngest soprano’, Julie Andrews.

That Julie was contracted as one of the gala’s headliners attests to her rising professional stock in the era. Now aged 17, she was fast moving beyond the child star persona of her early career and events such as this cabaret marked a pivot to a more mature and sophisticated style.

Unfortunately, as she relates in the first volume of her memoirs, Julie didn’t actually make it to the Cumberland Hotel that night due to a car breakdown:

“There were many glamourous events and galas during the time of the coronation, and my mother and I were invited to perform one evening at a hotel on Park Lane. We set off in Bettina, our trusty car. There was a low bridge on the way to London, where the road took a huge dip. We were decked out in our best attire, and as happens so often in England, it was simply teeming with rain. Ahead of us, under the bridge, was a vast body of water.

“Oh, just plow through it,” I advised Mum. “If we go fast enough, we ’ll come out the other side.”

Mum gunned the engine, and Bettina came to a hissing stop right in the middle of the pool. Her motor had completely flooded. Dressed in our finery, we waded out of the deep water and stumbled to a garage to ask for the car to be towed to safety. We never did make the concert” (2008, 154).

There is no record of how Julie’s absence was conveyed to the crowd at the Cumberland or what their response was...but we’d have been crying into our five guinea half-bottle of vintage champagne!

Sources:

Andrews, Julie (2008). Home: A memoir of my early years. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bartlett School (2023). Survey of London: Vol 11 Histories of Oxford Street. Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London.

Cumberland Hotel (1953). A souvenir of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. London.

Evening Standard, 27 April 1953: 2.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2023

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

To mark the recent announcement of a release date for the long awaited Blu-Ray of Duet for One from Kino Lorber -- June 27, folks -- here is a rare behind-the-scenes shot of the cast and crew from the final day of principal shooting at Stonor Park in March 1986.

Principals in the front row are from L to R: Margaret Courtney, Rupert Everett, Alan Bates, Julie Andrews, Cathryn Harrison, Andrei Konchalovsky, Macha Méril, Max von Sydow, and Nicola Perring. Absent, presumably because they were not involved in filming that day: Sigfrit Steiner, Liam Neeson, and Siobhan Redmond.

Here’s hoping the new release of Duet for One brings this criminally neglected gem of a film the belated love it deserves.

#julie andrews#duet for one#andrei konchalovsky#cannon films#1986#max von sydow#alan bates#rupert everett#kino lorber#behind the scenes

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

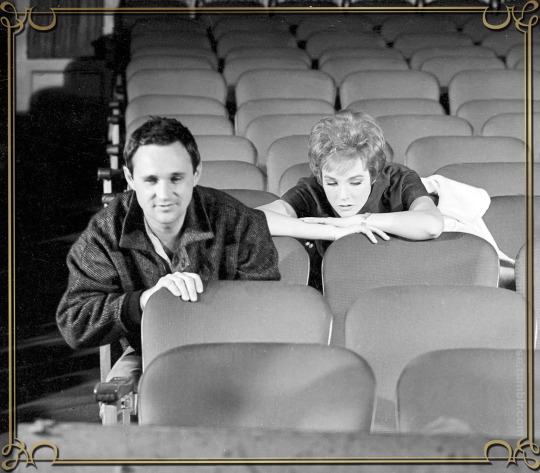

From the Archives: Julie and Pat Boone at the rehearsal for the Royal Command Variety Show at the London Coliseum. 3 November 1958.

As an added bit of trivia, Julie and Pat Boone shared the same dialect coach, Alfred Dixon. Dixon helped Julie master Cockney for My Fair Lady and he worked with Boone on his (not terribly convincing) Scottish accent in Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1959).

#julie andrews#pat boone#royal command variety#london coliseum#british theatre#1958#My Fair Lady#journey to the center of the earth

13 notes

·

View notes

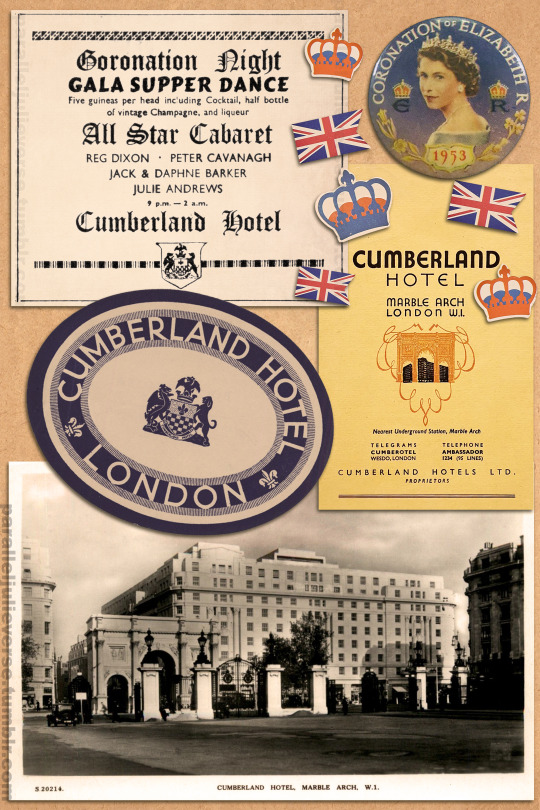

Photo

“Don't I tell you I'm bringin' you business...?!”

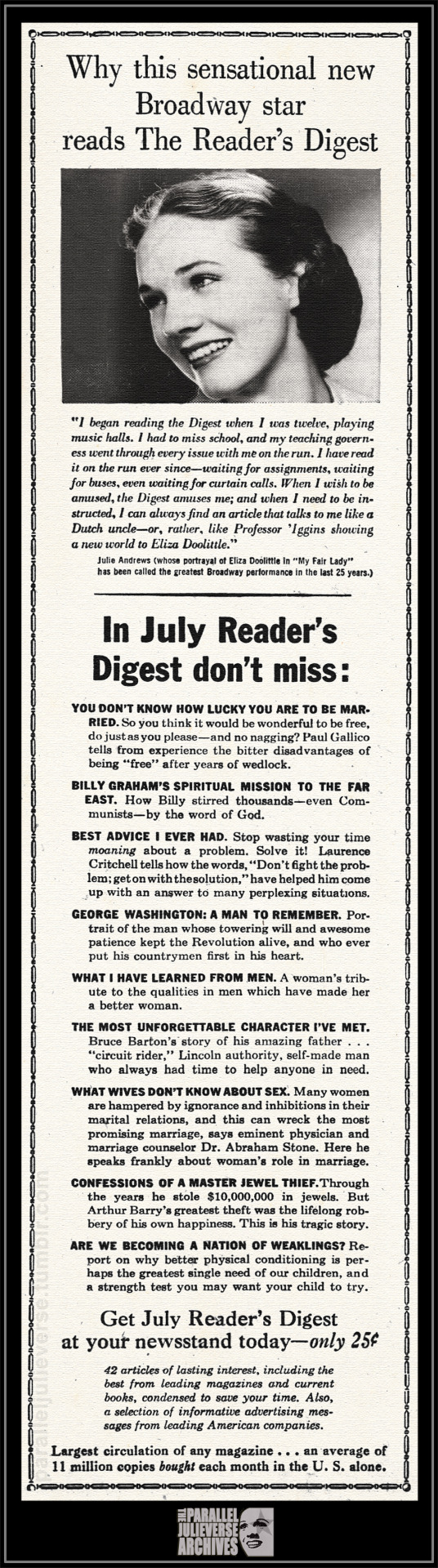

US newspaper advertisements from 1956 for Reader’s Digest featuring Julie Andrews who was riding high at the time on the smash success of My Fair Lady on Broadway. It was one of many advertising campaigns in the era that sought to capitalise on Julie’s newly minted stardom.

Sources:

Chicago Daily Tribune, 3 July 1956: F3.

The Southwestern, 6 November 1956: 4.

#julie andrews#My Fair Lady#1956#reader's digest#advertising#Broadway#musical theatre#eliza doolittle

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

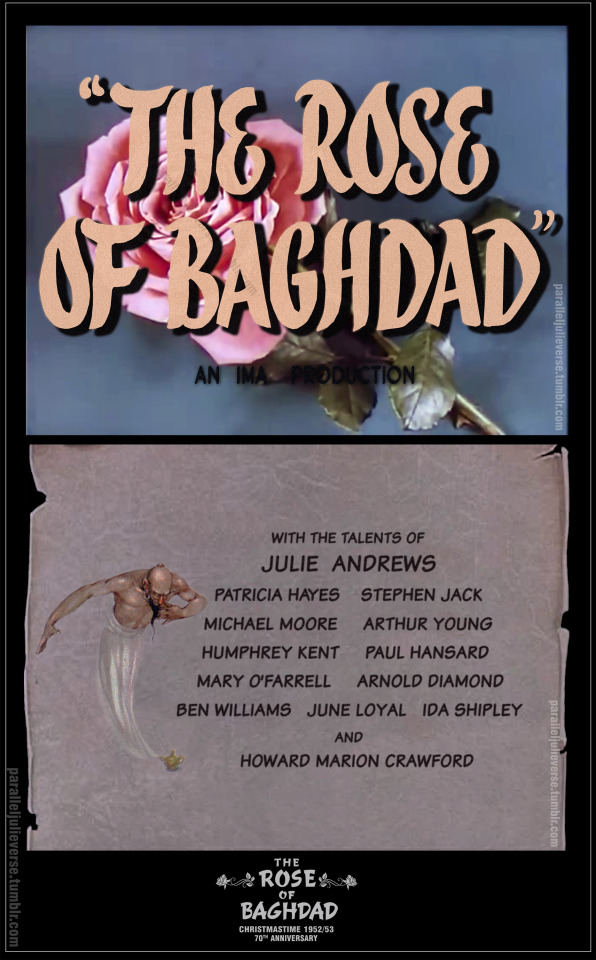

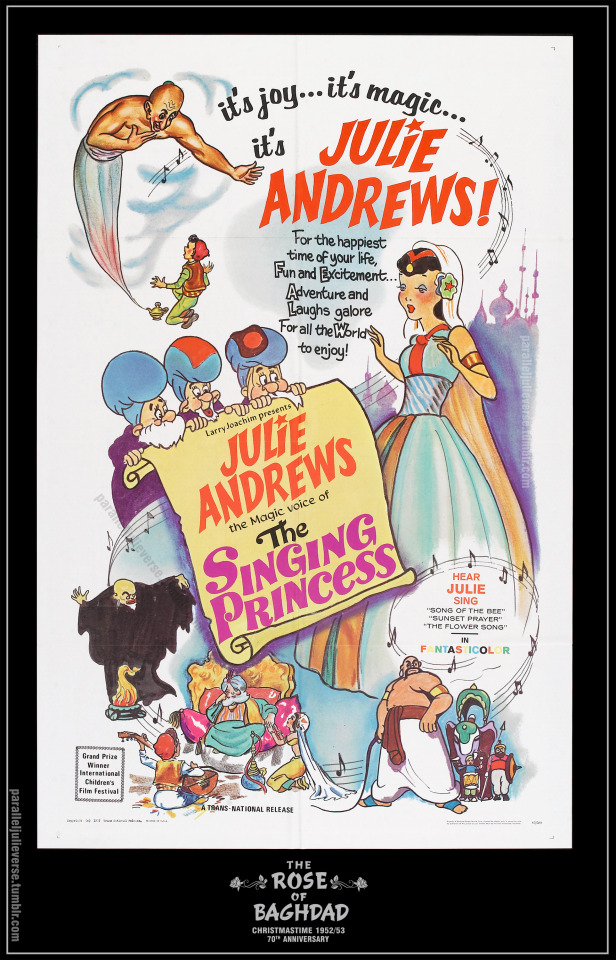

‘Who is queen of all the garden?’:

70th anniversary of The Rose of Baghdad (UK version)

Christmastime 1952/53

Ask almost anyone the name of Julie Andrews’ first film and the automatic response will be: “why, Mary Poppins...of course!” It’s part of Hollywood folklore that, having been passed over by Jack Warner for the film adaptation of My Fair Lady because she wasn’t a ‘proven movie star’, Andrews was offered the title role of the magical nanny in Walt Disney’s classic 1964 screen musical. It earned Andrews a Best Actress Oscar straight off the bat and catapulted her to international stardom as Hollywood’s musical sweetheart. Her film debut in Mary Poppins has even been a question in the ’easy’ category on Jeopardy! (Answered correctly, natch, for $100 by Steven Meyer, an attorney from Middletown, Connecticut).

But, with all due respect to Alex Trebek and general knowledge mavens everywhere, Julie's very first film actually came out more than a decade before Mary Poppins. In 1952, when the young star was just 16 going on 17, she was cast to voice the lead character of Princess Zeila in the UK version of the Italian animated film, The Rose of Baghdad.

It’s an easily overlooked part of Andrews’ oeuvre, figured, if at all, as a minor footnote to her later Broadway and Hollywood career. But The Rose of Baghdad was a not insignificant stepping stone in Andrews’ rise to stardom and one, moreover, that prefigures important aspects of her later screen image. So, on the 70th anniversary of the film’s British release, it is timely to look back briefly at The Rose of Baghdad.

La rosa italiana

Produced and directed by Anton Gino Domeneghini, The Rose of Bagdad -- or, in its original title, La rosa di Bagdad -- was the first feature-length animation ever made in Italy and also the country’s first Technicolor production. As such, it commands a prominent position in Italian film history (Bellano 2016; Bendazzi 2020).

La rosa di Bagdad was a real passion project for Domeneghini, a commercial artist and businessman with a successful advertising company, IMA, headquartered in Milan. During the 30s, Domeneghini’s firm handled the Italian marketing for many major international clients including Coca-Cola, Coty, and Gillette (Bendazzi: 23). With the outbreak of WW2, the advertising industry in Italy was effectively shut down. In an effort to keep his company afloat, Domeneghini rebranded as a film production company, IMA Films.

Inspired by the success of animated features from the US such as Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) and the Fleischer Brothers’ Gullivers Travels (1939), Domeneghini decided to produce an Italian animated film that could emulate the crowd-pleasing dimensions of American imports but with a distinct Italian sensibility (Fiecconi: 13-14). He threw himself heart and soul into the endeavour.

Based on an original idea developed from various stories Domeneghini had enjoyed as a boy, La rosa di Bagdad was conceived as an orientalist fairytale pastiche. The plot was patterned loosely after the Arabian Nights, complete with an Aladdin-style boy minstrel, a mystical genie, tyrannical sorcerer, and a golden-voiced princess. But it was embroidered with a host of other elements from assorted folktales and pop cultural texts.

To oversee the production, Domeneghini handpicked a core creative team including a pair of stage designers from La Scala, Nicola Benois and Mario Zampini, and a trio of head artists: animator Gustavo Petronio, caricaturist Angelo Bioletto, and illustrator Libico Maraja (Bendazzi: 23). They helped craft the film’s distinctive aesthetic with its striking blend of comic character-based animation and figurative exoticism of the Italian Orientalist School of painters such as Mariani, Simonetti, and Rosati (Fiecconi: 17).

Music was crucial to Domeneghini’s vision for the film. Fiecconi (2018) asserts that “the original creative part of the movie lies in the musical moments where the film seemed to celebrate the Italian opera” (17). Domeneghini commissioned the celebrated Milanese composer, Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli, to write the film’s musical score. It would be the composer’s last complete work before his untimely death at age 66 in early-1949 and it has been described as something of “a summa of Pick-Mangiagalli’s art” (Bellano: 34). Combining Hollywood-style romantic underscoring with Italian and Viennese classicism, Pick-Mangiagalli composed a broadly operatic score replete with arias, waltzes, and orientalist nocturnes.

Given the difficulties of wartime, the production process for La rosa was long and arduous and the film took over seven years to complete. At various stages, more than a hundred production staff worked on the film, including forty-seven animators, twenty-five ‘in-betweeners’, forty-four inkers and painters, five background artists, and an assortment of technicians and administrative assistants (Bendazzi: 25). Colour processing was initially done using the German Agfacolor system but it produced a greenish tint that was not to Domeneghini’s liking. So after the war, he took the film to the UK where it was reshot in Technicolor at Anson Dyer’s Stratford Abbey Studios in Stroud (Bendazzi: 24).

La Rosa di Bagdad finally premiered in 1949 at the Venice Film Festival where it won the Grand Prix in the Films for Youth category. The following year, the film was given a general public release in Italy. Leveraging his professional training as an ad man, Domeneghini crafted an extensive marketing and merchandising campaign for the film that was unprecedented at the time (Bendazzi: 30). It helped secure decent, if not spectacular, commercial returns for the film in Italy and encouraged Domengheni to shop his film abroad to other markets in Europe (Ugolotti: 8).

The English Rose

It was in this context that a distribution deal was brokered in early-1951 with Grand National Pictures in the UK to release La Rosa di Bagdad to the British market (’Many countries’: 20). Not to be confused with the short-lived US Poverty Row studio whose name -- and, even more confoundingly, logo -- it adopted, Grand Pictures was an independent British production-distribution company established in 1938 by producer Maurice J. Wilson. While it produced a few titles of its own, Grand National was predominantly geared to film distribution with an accent on imported product from the Continent and Commonwealth countries (McFarlane & Slide: 301).

Retitled The Rose of Baghdad, the film was part of an ambitious suite of twenty-six films slated for distribution by Grand National to British theatres in 1952, the company’s “biggest ever release programme” (’Grand National’: 16). The screenplay and musical lyrics were translated into English by Nina and Tony Maguire, and a completely new soundtrack was recorded at the celebrated De Lane Lea Processes studio in London (Massey 2015).

To do the voicework for the English-language version, Grand National assembled a roster of diverse British talent from across the fields of theatre, radio and film. The distinguished BBC actor Howard Marion-Crawford lent his sonorous baritone to the role of the narrator. RADA graduate and popular radio comedienne, Patricia Hayes voiced Amin, the teenage minstrel. Celebrated stage and film star, Arthur Young voiced the kindly Caliph, while rising TV actor Stephen Jack provided a suitably menacing Sheikh Jafar.

The biggest and most publicised name in the line-up, however, was Julie Andrews 'enacting’ the role of Princess Zeila. Much was made of Julie’s casting, and she was the only member of the British cast to be given named billing on the film’s poster and associated marketing materials. Scene-for-scene, her role wasn’t necessarily the biggest. Other characters have more lines and more action. But, as the symbolic “rose” of the film’s title and the focus of narrative attention, Julie as Princess Zeila had to carry much of the film's emotional weight.

And, musically, Princess Zeila certainly dominates proceedings. Her character is meant to posses a golden voice of rare enchantment and the film showcases her virtuosic singing in several key scenes. As mentioned earlier, composer Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli imbued the score with a strong operatic flavour and this is nowhere more apparent than in the three coloratura arias that he penned for Zeila: “Song of the Bee”, “Sunset Prayer” and the “Flower Song”. In the original Italian release, the part of Zeila was sung by Beatrice Preziosa, an opera soprano of some note who performed widely in the era with the RAI and had even sung opposite Gigli (Bellano: 35).

In her 2008 memoirs, Julie recalls the challenge of recording the Pick-Mangiagalli score:

“I had a coloratura voice, but these songs were so freakishly high that, though I managed them, there were some words that I struggled with in the upper register. I wasn’t terribly satisfied with the result. I didn’t think I had sung my best. But I remember seeing the film and thinking that the animation was beautiful. I’m pleased now that I did the work, for since then I don’t recall ever tackling such high technical material” (Andrews: 143-44).

The Rose opens

The British version of The Rose of Baghdad had its first public screenings in September of 1952 at a series of trade events organised by Grand National to market the picture to prospective exhibitors. The first such screening was on 16 September at Studio One in Oxford Street, London, followed by: 17 September at the Olympia in Cardiff; 19 September at the Scala in Birmingham; 22 September at the Cinema House in Sheffield; 23 September at the Tower in Leeds; 25 September at the Theatre Royal in Manchester; and 26 September at the Scala in Liverpool (’London and provincial’: 32; ’Trade show’: 14).

In promoting the film, Grand National pitched The Rose of Baghdad as wholesome family fare perfect for children’s matinees and double features. “A fascinating cartoon to enchant audiences of all ages” was the campaign catchline. They especially plugged the film’s potential as a seasonal attraction with full-page adverts in trade publications that billed it as the “showman’s picture for Christmastide”.

One of the film’s first UK reviews came out of these early trade screenings with Peter Davalle of the Welsh-based Western Mail newspaper filing a fulsome report:

“Ambitious in scale as anything that Disney has conceived...it has very right to demand the same intensity of judgement conferred on the Hollywood product. I have little but praise for it and I hope my enthusiasm will infect one of the country’s cinema circuit chiefs to the extent of giving it the showing it deserves” (Davalle: 4).

Ultimately, the film was unable to secure an exhibition deal with a major cinema chain. Instead, it was given a patchwork release at various independent and/or unaffiliated theatres across the country.

The Tatler theatre in Birmingham proudly billed its 14 December opening of The Rose of Baghdad as the film’s “first showing in England”. Archive research, however, evidences that it opened the same day at several other provincial theatres such as the Classic in Walsall (’Next week’: 10). Other notable early openings included the Alexandra Theatre in Coventry on 22 December -- the day before Julie premiered in the Christmas panto, Jack and the Beanstalk at the Coventry Hippodrome -- and the News Theatre in Liverpool and the Castle in Swansea on 29 December.

The film’s initial London release was at the Tatler in Charing Cross Road where it had a charity matinee premiere on 28 December sponsored by the West End Central Police with 470 children in the audience from the Police Orphanage (’Pre-release’: 119). The film then continued a chequerboard rollout across the UK throughout early-1953 with concentrated bursts around school holiday periods.

Because of the fitful nature of the film’s release pattern, The Rose of Baghdad didn’t attract sustained critical attention, though there were short reviews in various newspapers and publications. The critical response was lukewarm with reviewers finding the film pleasant, if lacking in technical polish. Most praised the English soundtrack with generally kind words for Julie:

The Times: “This Italian cartoon, ‘dubbed’ into English, proves once again how much more happy and at home the medium is with animals than with human beings. Mr. Walt Disney never did anything better than Bambi, which was given entirely over to the beasts and birds of the forest, and the Princess Zeila, the rose of Baghdad, proves just as unsatisfactory a figure as Snow White and Cinderella. The fault is that not of Miss Julie Andrews, who speaks and sings the part; it seems inherent in the medium itself...The Rose of Baghdad is not, however, without some delightful incidentals (’Entertainments’: 9).

The Observer: “Intelligently dubbed English version of full-length Italian cartoon...Nice use of crowds and minarets; one or two brilliant shots...; variably jerky animation; trite comedy; chocolate box princess...Not at all bad, a little too foreign to be cosy” (Lejeune: 6).

Picturegoer: “Charm stamps this full-length Italian cartoon, dubbed in English. Technically, it hardly bears comparison with the best of Disney. But it has genuine freshness and some appealing character studies...There is a delicate, very un-jivey musical score, and Julie Andrews sings attractively for the princess” (Collier: 17).

Photoplay: “The under 20′s and the over 50′s will love this one...Young B.B.C. star Julie Andrews ‘enacts’ the role of the Princess and sings three of the film’s seven tuneful songs....Yes, you’ll love this -- make it a must” (Allsop: 43).

Kinematograph Weekly: “Refreshing, disarmingly ingenuous Technicolor Arabian Nights-type fantasy, expressed in cartoon form. Made in Italy and expertly dubbed here...It hasn’t the fluid continuity nor flawless detail of Walt Disney’s masterpieces, but even so its many charming and novel characters come to life and atmosphere heightened by tuneful songs, is enchanting” (’Late review’: 7).

Picture Show & Film Pictorial: “Such a charming mixture of heroics, villainy and romance should not be missed, and although the animation is not as good as first-class American cartoons, the colour and the songs are delightful” (’New Release’: 10).

The Birmingham Post: “[A]n Italian cartoon in colour which equals Disney in artistic invention though not in smooth animation...Fancy flies high but always it takes us with it. Much of the colour work is beautiful...The characters remain always between the covers of the story book, but within their limited living rom they are a gay and enterprising company” (T.C.K.: 4).