#Clement Marot

Text

Chrome hearts Hermes birkin bag by Clement Marot

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plaque en hommage à : Clément Marot

Type : Lieu de résidence

Adresse : 27 rue de Tournon, 75006 Paris, France

Date de pose :

Texte : Ici s'élevait la maison donnée au poète Clément Marot (1496-1544) par François Premier, Roi de France

Quelques précisions : Clément Marot (1496-1544) est un poète français. Les sources fiables sur sa vie sont peu nombreuses, mais il est établi qu'il vécut sous le patronage de représentants de la noblesse française de l'époque. Il fut ainsi au service de Marguerite d'Angoulême, sœur de François Ier, et finira d'ailleurs par être un des poètes les plus éminents de la cour du roi de France. Il connaît le summum de sa célébrité dans les années 1530, mais ses sympathies pour les courants de la Réforme protestante lui valent des inimitiés qui le conduisent à l'emprisonnement et à l'exil (en Italie et en Suisse). Il meurt à Turin en 1544. Son œuvre abondante laisse un important héritage en poésie, notamment au sein de la communauté protestante, et facilita également la reconnaissance des travaux d'un autre célèbre poète français, François Villon. Cette plaque commémorative est située juste à côté d'une autre honorant l'aventurier Giacomo Casanova (qui vécut dans le même bâtiment deux siècles après Marot).

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

De Clement Marot a Marcudos, de #Paris a #Madrid. 1977 Ya casi empezaba la #democracia..... (at Madrid, Spain) https://www.instagram.com/p/ClcKKTiD_vh5kAp7L2BYpXIN0ou5ByEOmxdMps0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Audio

When Douglas Hofstadter was 16, he read a poem. Just an innocent little poem, a few short lines, nothing special. But the poem burrowed deep into his brain, and many years later, he set out to translate the thing and landed in a world of ham and jam and endless partial views of a person lost to time.

𝚃𝚁𝙰𝙽𝚂𝙲𝚁𝙸𝙿𝚃 ↴

𝗝𝗔𝗗 𝗔𝗕𝗨𝗠𝗥𝗔𝗗: 𝘏𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘰?

𝗗𝗢𝗨𝗚𝗟𝗔𝗦 𝗛𝗢𝗙𝗦𝗧𝗔𝗗𝗧𝗘𝗥: 𝘏𝘪 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘏𝘪!

𝗥𝗢𝗕𝗘𝗥𝗧 𝗞𝗥𝗨𝗟𝗪𝗜𝗖𝗛: 𝘐𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨?

𝗗𝗛: 𝘠𝘦𝘴.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘖𝘩 𝘣𝘰𝘺!

𝗝𝗔: 𝘚𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘦𝘱𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘥𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘪𝘯𝘴𝘱𝘪𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘢 𝘨𝘶𝘺 𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘦𝘥 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨 𝘏𝘰𝘧𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘥𝘵𝘦𝘳, 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘧𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘰𝘳 𝘰𝘧 𝘤𝘰𝘨𝘯𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘷𝘦 𝘴𝘤𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦, 𝘐𝘯𝘥𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘢 𝘜𝘯𝘪𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘺, 𝘉𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘵𝘰𝘯.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘢𝘺 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸 𝘩𝘪𝘮 𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘨𝘶𝘺 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘸𝘳𝘰𝘵𝘦 𝘎𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘭, 𝘌𝘴𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘳, 𝘉𝘢𝘤𝘩, 𝘸𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘩 𝘪𝘴 𝘢 𝘩𝘶𝘨𝘦𝘭𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘧𝘭𝘶𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘣𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘪𝘯 𝘤𝘦𝘳𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘯 𝘤𝘪𝘳𝘤𝘭𝘦𝘴. 𝘗𝘶𝘣𝘭𝘪𝘴𝘩𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘯, 𝘐 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘬, 1979. 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘸𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘩𝘪𝘮 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘯𝘬𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘥𝘶𝘤𝘦𝘳 𝘓𝘺𝘯𝘯 𝘓𝘦𝘷𝘺, 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘢𝘯 𝘰𝘣𝘴𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘥𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵.

𝗗𝗛: 16. 𝘐 𝘸𝘢𝘴 16.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘺𝘦𝘢𝘳, 1961.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘢𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩 𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦 𝘤𝘭𝘢𝘴𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘥𝘢𝘺 𝘐 𝘤𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘳𝘰𝘴𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈 𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘺 𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘭𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘴𝘢𝘵 𝘳𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘮𝘪𝘥𝘥𝘭𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘢𝘨𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘓𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘢 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯 𝘴𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘨𝘦. 𝘝𝘦𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘭. 𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸, 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘦𝘦 𝘴𝘺𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦𝘴 𝘱𝘦𝘳 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘚𝘰 𝘪𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘴𝘶𝘱𝘦𝘳 𝘴𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘯𝘺.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 28 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘪𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘥𝘦𝘭𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘧𝘶𝘭. 𝘐𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘤𝘶𝘵𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘧𝘶𝘯𝘯𝘺. 𝘐 𝘧𝘦𝘭𝘭 𝘪𝘯 𝘭𝘰𝘷𝘦 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘪𝘮𝘮𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘭𝘺 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘮𝘦𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘪𝘻𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘵. 𝘐 𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸 𝘪𝘵 𝘣𝘺 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘵.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘣𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘢 𝘨𝘦𝘵-𝘸𝘦𝘭𝘭 𝘤𝘢𝘳𝘥. 𝘐𝘵'𝘴 𝘸𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘣𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘨𝘶𝘺 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘔𝘢𝘳𝘰𝘵, 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘢 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘭𝘺 1500𝘴.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘈𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘢 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘦𝘯.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘳𝘰𝘵𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘦𝘯'𝘴 𝘥𝘢𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘦𝘳. 𝘚𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘴 7 𝘰𝘳 8 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘥 𝘨𝘰𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘬.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘭𝘶 𝘰𝘳 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘴𝘶𝘱𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘦𝘳 𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘶𝘱.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 -- 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘐 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘪𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘵.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘊𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘴𝘢𝘺 𝘪𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩?

𝗥𝗞: 𝘠𝘦𝘢𝘩, 𝘭𝘦𝘵'𝘴 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳 𝘪𝘵 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘴𝘵.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺. 𝘐𝘵'𝘴 𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘥 𝘈 𝘶𝘯𝘦 𝘋𝘢𝘮𝘰𝘺𝘴𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘦 𝘮𝘢𝘭𝘢𝘥𝘦. 𝘛𝘰 𝘈 𝘚𝘪𝘤𝘬 𝘋𝘢𝘮𝘴𝘦𝘭, 𝘴𝘰 𝘵𝘰 𝘴𝘱𝘦𝘢𝘬.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘈 𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘬 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘨 𝘭𝘢𝘥𝘺.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘈 𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘬 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘨 𝘭𝘢𝘥𝘺. 𝘔𝘢 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦, 𝘫𝘦 𝘷𝘰𝘶𝘴 𝘥𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦 𝘭𝘦 𝘣𝘰𝘯 𝘫𝘰𝘶𝘳; 𝘭𝘦 𝘴é𝘫𝘰𝘶𝘳, 𝘤’𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯. 𝘎𝘶é𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯 𝘳𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘷𝘳𝘦𝘻, 𝘱𝘶𝘪𝘴 𝘰𝘶𝘷𝘳𝘦𝘻 𝘷𝘰𝘵𝘳𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘦 𝘦𝘵 𝘲𝘶’𝘰𝘯 𝘴𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵, 𝘤𝘢𝘳 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘭𝘦 𝘷𝘰𝘶𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦. 𝘝𝘢, 𝘧𝘳𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦 𝘥𝘦 𝘵𝘢 𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘤𝘩𝘦, 𝘲𝘶𝘪 𝘴𝘦 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘤𝘩𝘦 𝘦𝘯 𝘥𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘳 𝘱𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘳 𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘧𝘪𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦𝘴; 𝘴𝘪 𝘵𝘶 𝘥𝘶𝘳𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘳𝘰𝘱 𝘮𝘢𝘭𝘢𝘥𝘦, 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘦𝘶𝘳 𝘧𝘢𝘥𝘦 𝘵𝘶 𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘥𝘳𝘢𝘴, 𝘦𝘵 𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘥𝘳𝘢𝘴 𝘓’𝘦𝘮𝘣𝘰𝘯𝘱𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘵. 𝘋𝘪𝘦𝘶 𝘵𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘵 𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘵é 𝘣𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦, 𝘮𝘢 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦.

𝗟𝗬𝗡𝗡 𝗟𝗘𝗩𝗬: 𝘖𝘩 𝘮𝘺 𝘎𝘰𝘥, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘨𝘰𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘴𝘰 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘺 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘬𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘦𝘳𝘦 16.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘐 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸! 𝘛𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 ...

𝗥𝗞: [𝘭𝘢𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘴]

𝗗𝗛: 𝘌𝘹𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘭𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘱𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘦. 𝘐 𝘸𝘢𝘴 -- 𝘐 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 -- 𝘐 𝘸𝘪𝘴𝘩.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺, 𝘴𝘰 𝘩𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮, 𝘧𝘪𝘭𝘦𝘴 𝘪𝘵 𝘢𝘸𝘢𝘺 𝘥𝘦𝘦𝘱 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘤𝘰𝘳𝘯𝘦𝘳 𝘰𝘧 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘥. 𝘍𝘢𝘴𝘵 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘸𝘢𝘳𝘥 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 20 𝘺𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘴, 𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘶𝘣𝘭𝘪𝘴𝘩𝘦𝘴 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘴𝘵 𝘣𝘰𝘰𝘬. 𝘐𝘵 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘴 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘱𝘰𝘱𝘶𝘭𝘢𝘳 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘶𝘣𝘭𝘪𝘴𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘥𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘪𝘵 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘢 𝘯𝘶𝘮𝘣𝘦𝘳 𝘰𝘧 𝘭𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘶𝘢𝘨𝘦𝘴, 𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘭𝘶𝘥𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘤𝘦𝘴𝘴, 𝘸𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘩 𝘵𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘺𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘴 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐𝘵 𝘱𝘶𝘵 𝘮𝘦 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘳𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘨, 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘤𝘳𝘢𝘻𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘩𝘢𝘱𝘱𝘦𝘯 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘤𝘳𝘢𝘻𝘺 𝘵𝘦𝘹𝘵𝘴. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘰𝘧 𝘢 𝘴𝘶𝘥𝘥𝘦𝘯 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘥𝘢𝘺 ...

𝗝𝗔: 𝘛𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘱𝘰𝘱𝘱𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘐 𝘴𝘢𝘪𝘥, "𝘈𝘩, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦'𝘴 𝘢 𝘤𝘩𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘦! 𝘓𝘦𝘵'𝘴 𝘵𝘳𝘺 𝘵𝘰 𝘥𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴!"

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘴𝘢𝘺 𝘤𝘩𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘦, 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘪𝘵?

𝗥𝗞: 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 -- 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘤𝘩𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘦?

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺. 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘐 𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘯𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘰 ...

𝗝𝗔: 𝘚𝘰 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦'𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨. 𝘏𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘔𝘢 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦, 𝘫𝘦 𝘷𝘰𝘶𝘴 𝘥𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦 𝘭𝘦 𝘣𝘰𝘯 𝘫𝘰𝘶𝘳 ...

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘪𝘧 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘧𝘰𝘤𝘶𝘴 𝘰𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘥𝘴, 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘣𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 -- 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘨𝘶𝘺 𝘵𝘢𝘭𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘰 𝘢 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘳 𝘨𝘪𝘳𝘭 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨, "𝘏𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘰 𝘮𝘺 𝘥𝘦𝘢𝘳. 𝘐'𝘮 𝘴𝘰𝘳𝘳𝘺 𝘺𝘰𝘶'𝘳𝘦 𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘬. 𝘉𝘦𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘬 𝘪𝘴 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯."

𝗗𝗛: 𝘓𝘦 𝘴é𝘫𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘤’𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘐, 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵, 𝘸𝘪𝘴𝘩 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘵𝘰 𝘰𝘱𝘦𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘥𝘰𝘰𝘳𝘴, 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘭𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘊𝘢𝘳 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘭𝘦 𝘷𝘰𝘶𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘎𝘦𝘵 𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘌𝘢𝘵 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘫𝘢𝘮.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘊𝘰𝘯𝘧𝘪𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦𝘴.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘚𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘴𝘰 𝘱𝘢𝘭𝘦 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘊𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘦𝘶𝘳 𝘧𝘢𝘥𝘦 ...

𝗝𝗔: ... 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘭𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘱𝘭𝘶𝘮𝘱 𝘴𝘩𝘢𝘱𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘌𝘵 𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘥𝘳𝘢𝘴 𝘭’𝘦𝘮𝘣𝘰𝘯𝘱𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘵.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸, 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘴𝘰𝘳𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, "𝘎𝘦𝘵 𝘣𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳. 𝘏𝘦𝘳𝘦'𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘨𝘰𝘰𝘥 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩."

𝗗𝗛: 𝘋𝘪𝘦𝘶 𝘵𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘵 𝘚𝘢𝘯𝘵é 𝘣𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦, 𝘮𝘢 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘥𝘴 𝘪𝘯 𝘌𝘯𝘨𝘭𝘪𝘴𝘩 𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘩𝘰𝘭𝘦 𝘴𝘱𝘪𝘳𝘪𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘰𝘯𝘦, 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘦𝘥𝘯𝘦𝘴𝘴 ...

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 -- 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘴 𝘬𝘦𝘺 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨. 𝘐𝘵 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘰𝘳𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮'𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐𝘵𝘴 𝘸𝘰𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘧𝘶𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘤𝘢𝘵𝘤𝘩𝘺 ...

𝗝𝗔: 𝘓𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘭𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘨𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘢𝘱𝘦 𝘰𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘢𝘨𝘦. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘙𝘩𝘺𝘮𝘦. 𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸, 𝘈𝘈, 𝘉𝘉, 𝘊𝘊, 𝘋𝘋. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘴𝘵 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘔𝘢 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦...

𝗗𝗛: ... 𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘭 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘭𝘢𝘴𝘵 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘔𝘢 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘦.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘚𝘰 𝘪𝘵 𝘴𝘰𝘳𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭 𝘰𝘧 𝘢 𝘱𝘢𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘥𝘳𝘰𝘮𝘦?

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘵'𝘴 𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘮𝘪𝘥𝘥𝘭𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘭𝘦 𝘷𝘰𝘶𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘩, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘐 -- 𝘥𝘪𝘥 𝘐 𝘴𝘢𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘦𝘦 𝘴𝘺𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦𝘴 𝘱𝘦𝘳 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦?

𝗥𝗞: 𝘕𝘰, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘥𝘪𝘥𝘯'𝘵. 𝘕𝘰𝘵 𝘺𝘦𝘵.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘧 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘴𝘦. 𝘛𝘩𝘳𝘦𝘦 𝘴𝘺𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦𝘴 𝘱𝘦𝘳 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦. 𝘐 𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘯, 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵'𝘴 𝘤𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 28 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨. 𝘚𝘰 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴 𝘢𝘥𝘥𝘦𝘥 𝘶𝘱 𝘵𝘰 𝘢 𝘴𝘦𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘴, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘴𝘢𝘺, 𝘰𝘯 𝘮𝘦.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘚𝘰 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨 𝘴𝘢𝘵 𝘥𝘰𝘸𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘬, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘲𝘶𝘪𝘤𝘬𝘭𝘺 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘦𝘮𝘣𝘳𝘰𝘪𝘭𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧, 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘥𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮? 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘢𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘺 𝘩𝘦 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘨𝘢𝘯 𝘵𝘰 𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘭𝘦 𝘨𝘳𝘪𝘥𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘣𝘪𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘦𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘥𝘪𝘧𝘧𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮. 𝘍𝘰𝘳 𝘦𝘹𝘢𝘮𝘱𝘭𝘦 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘝𝘢, 𝘧𝘳𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘦 𝘥𝘦 𝘵𝘢 𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘤𝘩𝘦, 𝘲𝘶𝘪 𝘴𝘦 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘤𝘩𝘦 ...

𝗝𝗔: 𝘓𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘣𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘴, "𝘋𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘰𝘸 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘥."

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐 𝘩𝘢𝘥 𝘢 𝘭𝘰𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘣𝘪𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘦𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘐'𝘭𝘭 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘭𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘢𝘨𝘰𝘯𝘢𝘭 𝘥𝘪𝘴𝘱𝘭𝘢𝘺 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. "𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘴𝘱𝘶𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘣𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘣𝘶𝘳𝘱𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘣𝘶𝘳𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘭𝘶𝘳𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘩𝘶𝘳𝘵𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘩𝘶𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘴𝘲𝘶𝘪𝘳𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘴𝘭𝘶𝘳𝘱𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘴𝘭��𝘱 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘣𝘶𝘳𝘯𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘶𝘱 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘥. 𝘐𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘯𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘣𝘭𝘶𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘥."

𝗝𝗔: 𝘖𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘯.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘐 𝘤𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘶𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘵 𝘮𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘮𝘺 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘴𝘵 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯?

𝗥𝗞: 𝘠𝘦𝘢𝘩, 𝘱𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘴𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: "𝘔𝘺 𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘵 𝘥𝘦𝘢𝘳. 𝘐 𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘥 𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘦𝘳. 𝘈𝘭𝘭 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘴𝘵. 𝘠𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘤𝘦𝘥 𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘫𝘢𝘪𝘭. 𝘚𝘰 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘢𝘪𝘭 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨. 𝘑𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘰𝘯𝘨. 𝘎𝘰 𝘰𝘶𝘵𝘴𝘪𝘥𝘦. 𝘛𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘢 𝘳𝘪𝘥𝘦. 𝘋𝘰 𝘪𝘵 𝘲𝘶𝘪𝘤𝘬. 𝘚𝘵𝘢𝘺 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘴𝘪𝘤𝘬. 𝘉𝘢𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘢𝘤𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘮𝘺 𝘴𝘢𝘬𝘦. 𝘉𝘶𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘸𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘥 𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦𝘴 𝘢 𝘮𝘦𝘴𝘴. 𝘚𝘰 𝘶𝘯𝘭𝘦𝘴𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘤𝘩𝘰𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘣𝘢𝘥 𝘯𝘦𝘸𝘴, 𝘐 𝘴𝘶𝘨𝘨𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶'𝘥 𝘣𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘴𝘰𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘦. 𝘚𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘦𝘺𝘦𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘨𝘭𝘢𝘻𝘦. 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘭𝘢𝘴 𝘱𝘳𝘢𝘺𝘴 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩 𝘣𝘦 𝘯𝘦𝘢𝘳, 𝘮𝘺 𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘵 𝘥𝘦𝘢𝘳."

𝘙𝘒: 𝘖𝘩. 𝘚𝘰 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘯𝘰𝘸 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘭𝘢𝘴.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘠𝘦𝘢𝘩, 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘭𝘢𝘴. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘐 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘥 ...

𝗥𝗞: 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘫𝘢𝘮 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥, 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘉𝘶𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘉𝘶𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘉𝘶𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥. 𝘠𝘦𝘴. 𝘞𝘦𝘭𝘭, 𝘐 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘧𝘪𝘨𝘶𝘳𝘦 𝘫𝘢𝘮 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘫𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘺, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘺 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘥𝘴, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘥𝘴 𝘳𝘦𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘤𝘦𝘱𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘤𝘦𝘱𝘵𝘴 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘢 𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘢 𝘩𝘢𝘭𝘰 𝘢𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮. 𝘐 𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘯, 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘵𝘢𝘭𝘬 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘫𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘺, 𝘺𝘰𝘶'𝘳𝘦 𝘪𝘮𝘱𝘭𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘵𝘭𝘺 𝘵𝘢𝘭𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘴𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘪𝘵 𝘰𝘯.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘖𝘩, 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨!

𝗥𝗞: 𝘚𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘱𝘦𝘰𝘱𝘭𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘬 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘪𝘳 𝘧𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘳𝘴 𝘪𝘯 𝘫𝘦𝘭𝘭𝘺. 𝘕𝘰 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘥𝘦𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺. 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺, 𝘧𝘢𝘪𝘳 𝘦𝘯𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘍𝘦𝘦𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘩𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘲𝘶𝘪𝘵𝘦 𝘯𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘵, 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨 𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘵𝘰 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘨𝘶𝘺𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘴𝘵 𝘣𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘠𝘦𝘢𝘩.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈 𝘨𝘶𝘺 𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘦𝘥 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘥𝘥𝘭𝘺 𝘦𝘯𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩, 𝘉𝘰𝘣 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘉𝘰𝘣 𝘸𝘢𝘴 ...

𝗥𝗞: [𝘭𝘢𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘴]

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐 𝘴𝘢𝘪𝘥, "𝘏𝘦𝘺 𝘉𝘰𝘣, 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘥𝘰 𝘪𝘵?" 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘉𝘰𝘣 𝘴𝘢𝘪𝘥, "𝘞𝘦𝘭𝘭, 𝘐'𝘭𝘭 𝘨𝘪𝘷𝘦 𝘪𝘵 𝘢 𝘵𝘳𝘺."

𝗗𝗛: "𝘍𝘢𝘪𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘧𝘳𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘥, 𝘭𝘦𝘵 𝘮𝘦 𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘥 𝘮𝘺 𝘦𝘮𝘣𝘳𝘢𝘤𝘦. 𝘘𝘶𝘪𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘭𝘢𝘤𝘦, 𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘥𝘢𝘳𝘬 𝘩𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘢𝘯𝘬 𝘸𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘴. 𝘐𝘯 𝘴𝘰𝘧𝘵 𝘴𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩, 𝘳𝘦𝘨𝘢𝘪𝘯 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩. 𝘋𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘧𝘭𝘦𝘦 𝘰𝘧𝘧 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘮𝘦, 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘴 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘺𝘰𝘶."

𝗗𝗛: 𝘝𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘥𝘪𝘧𝘧𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘰𝘯𝘦, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘲𝘶𝘪𝘵𝘦 𝘮𝘢𝘳𝘷𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘶𝘴.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘏𝘦 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘢𝘭𝘦 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘏𝘦 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘫𝘢𝘮. 𝘏𝘦 𝘱𝘶𝘵 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵'𝘴 𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘮𝘪𝘥𝘥𝘭𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦, 𝘪𝘵 𝘥𝘪𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘴𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘶𝘤𝘩 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘵.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘞𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘩 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘨𝘶𝘦 𝘸𝘦𝘭𝘭, 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘢𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮. 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘴 𝘯𝘰, 𝘯𝘰. 𝘛𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦'𝘴 𝘢 𝘣𝘪𝘨𝘨𝘦𝘳 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘣𝘭𝘦𝘮.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 30 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨. 𝘚𝘰 𝘦𝘹𝘵𝘳𝘢 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 28 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘢 𝘴𝘢𝘤𝘳𝘰𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘵 𝘯𝘶𝘮𝘣𝘦𝘳.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵'𝘴 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘵𝘸𝘰 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘕𝘰, 𝘯𝘰, 𝘯𝘰, 𝘯𝘰, 𝘯𝘰. 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘔𝘢𝘳𝘰𝘵 𝘸𝘳𝘰𝘵𝘦 𝘢 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘦𝘦-𝘴𝘺𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘰𝘧 28 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘳𝘩𝘺𝘮𝘦𝘥 𝘸𝘰𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘧𝘶𝘭𝘭𝘺, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘢 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮 𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘯 𝘢 -- 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘯 𝘢 𝘮𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘢𝘨𝘦. 𝘛𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘴, 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘮𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘢𝘨𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘸𝘦𝘭𝘭.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘞𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘩 𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘺 𝘴𝘪𝘮𝘱𝘭𝘦, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨 𝘸𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘨𝘶𝘦 𝘯𝘰, 𝘪𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮. 𝘛𝘩𝘢𝘵'𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘮𝘢𝘥𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘧𝘶𝘯𝘯𝘺 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘤𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘨. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘴𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘩𝘪𝘮 𝘸𝘢𝘴, 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘯𝘢𝘪𝘭 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘢 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨 𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘺 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘳𝘵, 𝘩𝘦 𝘦𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘥 𝘶𝘱 𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘥𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘰, 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, 60 𝘱𝘦𝘰𝘱𝘭𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘋𝘰𝘤𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘢𝘭 𝘴𝘵𝘶𝘥𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘴 ...

𝗗𝗛: "𝘞𝘩𝘰 𝘮𝘺 𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘵, 𝘐 𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵. 𝘖𝘯𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘨𝘢𝘳𝘥. 𝘖𝘩 '𝘵𝘪𝘴 𝘩𝘢𝘳𝘥, 𝘥𝘦𝘢𝘳 𝘳𝘦𝘤𝘭𝘶𝘴𝘦."

𝗗𝗛: 𝘊𝘰𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘨𝘶𝘦𝘴, 𝘧𝘳𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘥𝘴 ...

𝗗𝗛: "𝘊𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘬𝘢𝘥𝘦𝘦, 𝘐 𝘥𝘦𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘦 𝘢 𝘧𝘪𝘯𝘦 𝘥𝘢𝘺."

𝗝𝗔: 𝘏𝘦 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘯 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘧𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘥𝘰 𝘰𝘯𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: "𝘋𝘢𝘳𝘵 𝘢𝘸𝘢𝘺 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘤𝘢𝘨𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘢𝘨𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘳𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘧𝘭𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵, 𝘴𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘧𝘭𝘦𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘤𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘱."

𝗝𝗔: 𝘛𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘣𝘪𝘳𝘥-𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮𝘦𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: "𝘏𝘰𝘱𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘴𝘸𝘰𝘰𝘱 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘢𝘮, 𝘢𝘱𝘱𝘭𝘦 𝘫𝘢𝘮 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩 𝘣𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘋𝘪𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘨𝘰 𝘳𝘶𝘯𝘯𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘥 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘵𝘰𝘸𝘯 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘰𝘸𝘯 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨, "𝘏𝘦𝘺, 𝘐 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘢 𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘭𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮. 𝘈𝘯𝘺𝘣𝘰𝘥𝘺 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘨𝘪𝘷𝘦 𝘪𝘵 𝘢 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯?"

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐 𝘤𝘦𝘳𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘯𝘭𝘺 𝘥𝘪𝘥. 𝘐 𝘢𝘮 𝘢 𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 𝘣𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘣𝘦𝘨𝘢𝘯 𝘢 𝘣𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘦, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘴𝘢𝘺.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘣𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘦 𝘦𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘥 𝘶𝘱 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢 700-𝘱𝘢𝘨𝘦 𝘣𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘧𝘪𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘥 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘎𝘰 𝘢𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘯𝘰𝘸. 𝘛𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘰𝘯𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘠𝘦𝘢𝘩, 𝘳𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵. 𝘙𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵. 𝘕𝘰, 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘴 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘰𝘯𝘦.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘐𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘰𝘯𝘦.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘕𝘰, 𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘱 𝘪𝘵. 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺, 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘸𝘦 𝘨𝘰. 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺. 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘛𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘩𝘪𝘴, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 20𝘵𝘩 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: "𝘗𝘢𝘭 𝘱𝘦𝘵𝘪𝘵𝘦, 𝘨𝘢𝘭 𝘴𝘰 𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘵. 𝘏𝘶𝘨 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨. 𝘚𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘥𝘶𝘮𝘣 𝘣𝘶𝘨 𝘥𝘳𝘢𝘨𝘨𝘦𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘥𝘰𝘸𝘯. 𝘡𝘢𝘱 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯. 𝘍𝘦𝘦𝘭 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘶𝘳𝘨𝘦, 𝘣𝘶𝘨𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘱𝘶𝘳𝘨𝘦. 𝘍𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘨𝘦, 𝘺𝘰𝘶'𝘭𝘭 𝘦𝘮𝘦𝘳𝘨𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘢 𝘵𝘳𝘪𝘤𝘦. 𝘚𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘥 𝘢𝘥𝘷𝘪𝘤𝘦 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 -- 𝘢𝘩𝘦𝘮 -- 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨 𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘴𝘩 𝘊𝘭𝘦𝘮. 𝘚𝘰 𝘴𝘮𝘢𝘴𝘩 𝘧𝘭𝘶. 𝘊𝘰𝘮𝘦. 𝘠𝘰𝘰-𝘩𝘰𝘰. 𝘊𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘭𝘪𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘸. 𝘚𝘩𝘦𝘦𝘵𝘴 𝘦𝘴𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘸. 𝘚𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘵𝘴 𝘭𝘦𝘵'𝘴 𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘸. 𝘗𝘰𝘱 𝘢 𝘵𝘢𝘳𝘵. 𝘔𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘵 𝘱𝘢𝘭𝘱𝘪𝘵𝘢𝘵𝘦. 𝘊𝘭𝘦𝘮'𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘢𝘵𝘦. 𝘚𝘶𝘳𝘦 𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘦 𝘎𝘰𝘥 𝘤𝘶𝘳𝘦𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘣𝘰𝘥 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘵. 𝘗𝘢𝘭 𝘱𝘦𝘵𝘪𝘵𝘦."

𝗥𝗞: 𝘚𝘶𝘳𝘦 𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘦 𝘎𝘰𝘥 𝘤𝘶𝘳𝘦𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘣𝘰𝘥! [𝘭𝘢𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘴]

𝗗𝗛: [𝘭𝘢𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘴]. 𝘐 𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘢𝘥𝘮𝘪𝘵 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘩𝘶𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘴.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘠𝘦𝘢𝘩!

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘭𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘴𝘵, 𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘴.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐 -- 𝘐 𝘥𝘰 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘮𝘺 𝘮𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳'𝘴 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯, 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘮𝘺 𝘮𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳'𝘴 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘩𝘰𝘸 -- 𝘐'𝘮 𝘨𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘢 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘪𝘵 𝘶𝘱 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘞𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘪𝘵? 𝘞𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘭𝘥 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘪𝘵? 𝘛𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘣𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘪𝘴 𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘭𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘯𝘥 ...

𝗝𝗔: 𝘛𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘰𝘮 𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘴, 𝘤𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘢𝘭𝘰𝘯𝘨 𝘺𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘴 𝘢𝘧𝘵𝘦𝘳 𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘦𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘏𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘪𝘵 𝘪𝘴.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘬𝘴 𝘪𝘵 𝘮𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘣𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘪𝘯𝘯𝘦𝘳.

𝗗𝗛: "𝘏𝘪 𝘵𝘰𝘰𝘵𝘴. 𝘎𝘦𝘵 𝘸𝘦𝘭𝘭. 𝘏𝘰𝘴𝘱𝘪𝘵𝘢𝘭'𝘴 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘰𝘯'𝘴 𝘩𝘦𝘭𝘭. 𝘎𝘦𝘵 𝘸𝘦𝘭𝘭. 𝘍𝘭𝘦𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘤𝘦𝘭𝘭. 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵'𝘴 𝘰𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘴 𝘪𝘯 𝘢 𝘯𝘶𝘵𝘴𝘩𝘦𝘭𝘭. 𝘎𝘰 𝘱𝘪𝘨 𝘰𝘶𝘵. 𝘖𝘱𝘦𝘯 𝘸𝘪𝘥𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘮𝘰𝘶𝘵𝘩. 𝘒𝘦𝘦𝘱 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘵𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘴 𝘨𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘴𝘰𝘶𝘵𝘩. 𝘜𝘯𝘭𝘦𝘴𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶'𝘳𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘪𝘭, 𝘺𝘰𝘶'𝘭𝘭 𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘯 𝘱𝘢𝘭𝘦. 𝘓𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘰𝘰𝘩-𝘭𝘢-𝘭𝘢 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘪𝘨𝘨𝘭𝘦𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘵𝘢𝘪𝘭. 𝘎𝘰𝘥 𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘨𝘰𝘰𝘥 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘵𝘩 𝘵𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘺 𝘭𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘭𝘦 𝘧𝘭𝘰𝘸𝘦𝘳, 𝘮𝘰𝘯 𝘱𝘦𝘵𝘪𝘵𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘦."

𝗝𝗔: 𝘞𝘰𝘸! 𝘛𝘩𝘢𝘵'𝘴 𝘤𝘰𝘰𝘭!

𝗗𝗛: 𝘕𝘰𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘦𝘴𝘯'𝘵 𝘣𝘦𝘨𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘦𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦. 𝘚𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘦𝘴𝘯'𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 28 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴. 𝘚𝘩𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘺𝘣𝘦 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 16 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴. 𝘚𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘦𝘴𝘯'𝘵 𝘱𝘢𝘺 𝘢𝘯𝘺 𝘢𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘵𝘰 𝘴𝘺𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘤𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘵.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘵'𝘷𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘰𝘯𝘦.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘠𝘦𝘢𝘩, 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 ...

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐 𝘥𝘪𝘥. 𝘔𝘺 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘴𝘵 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘸𝘢𝘴, "𝘖𝘩, 𝘔𝘰𝘮. 𝘕𝘰, 𝘔𝘰𝘮. 𝘊𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘰𝘯! 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘥𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶 -- 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘰𝘯! 𝘋𝘪𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘱𝘢𝘺 𝘢𝘯𝘺 𝘢𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮?" 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘪𝘥, "𝘐 𝘥𝘪𝘥 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘐 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘥𝘰. 𝘛𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘺 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘨, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸, 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵'𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘐 𝘥𝘪𝘥." 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸, 𝘐 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘴𝘢𝘺 𝘪𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘰𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦. 𝘐𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘱𝘪𝘻𝘻𝘢𝘻𝘻 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘯𝘰 𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘳 𝘩𝘢𝘥.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘪𝘧 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮, 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘥𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘺𝘭𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦𝘴, 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘳𝘩𝘺𝘮𝘦 𝘪𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘺 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘴𝘶𝘱𝘱𝘰𝘴𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘳𝘩𝘺𝘮𝘦, 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘨𝘪𝘷𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶 28 𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴, 𝘴𝘩𝘦 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘯, 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘩𝘢𝘭𝘷𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵, 𝘱𝘳𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺, 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘢 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘰𝘳 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘢 𝘮𝘰𝘮? 𝘐 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 -- 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵?

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘯𝘦 𝘩𝘶𝘯𝘥𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘧𝘭𝘰𝘸𝘦𝘳𝘴 𝘣𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘮. 𝘈𝘴 𝘐 𝘨𝘰𝘵 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘥𝘦𝘦𝘱𝘭𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮, 𝘮𝘺 𝘱𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘰𝘴𝘰𝘱𝘩𝘺 𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘊𝘩𝘢𝘪𝘳𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘔𝘢𝘰'𝘴 𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵, "𝘓𝘦𝘵 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘩𝘶𝘯𝘥𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘧𝘭𝘰𝘸𝘦𝘳𝘴 𝘣𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘮." 𝘐𝘯 𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘥𝘴, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘵 𝘧𝘳𝘰𝘮 𝘴𝘰 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘺 𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘭𝘦𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘯𝘦𝘸 𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘭𝘦 𝘦𝘯𝘳𝘪𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘴 𝘪𝘵 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦𝘴 𝘪𝘵 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘧𝘶𝘯.

𝗟𝗟: 𝘈𝘭𝘭 𝘳𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘢𝘯'𝘵 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘢 𝘩𝘶𝘯𝘥𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺, 𝘰𝘬𝘢𝘺. 𝘐 𝘢𝘨𝘳𝘦𝘦. 𝘠𝘰𝘶'𝘳𝘦 𝘳𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘐𝘵 𝘥𝘰𝘦𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘮𝘦 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩, 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘳𝘶𝘭𝘦𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘢𝘨𝘦𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘢 𝘸𝘢𝘺.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘛𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘯𝘰 𝘳𝘶𝘭𝘦𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘯𝘰 𝘳𝘶𝘭𝘦𝘴. 𝘐𝘵'𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘪𝘯𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘮𝘢𝘭.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘖𝘬𝘢𝘺, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦'𝘴 𝘫𝘢𝘮 𝘪𝘯 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘩𝘢𝘮 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳. 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘺'𝘳𝘦 -- 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘺'𝘳𝘦 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘥𝘪𝘧𝘧𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘧𝘰𝘰𝘥 𝘴𝘶𝘣𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘦𝘴. 𝘚𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥𝘯'𝘵 𝘣𝘦 𝘯𝘦𝘨𝘰𝘵𝘪𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦, 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘺?

𝗗𝗛: 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘴 -- 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘥𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘯 𝘣𝘺 𝘢 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘵? 𝘐 𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘯, 𝘢 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘵 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘸𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘣𝘺 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘣𝘰𝘥𝘺 𝘪𝘯 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩. 𝘐𝘵'𝘴 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘩 𝘢𝘯𝘺𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦.

𝗥𝗞: 𝘞𝘢𝘪𝘵, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘯𝘰𝘸 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦'𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘑𝘢𝘥 𝘐 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘬 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘸𝘰𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘨, 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘸𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨, 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘥𝘰 𝘸𝘦 𝘮𝘢𝘬𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘩𝘦'𝘴 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨? 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘭𝘢𝘷𝘰𝘳𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘩𝘦'𝘴 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨? 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘷𝘢𝘳𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘩𝘦'𝘴 𝘴𝘢𝘺𝘪𝘯𝘨?

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘺𝘰𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵. 𝘓𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘪𝘴𝘯'𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘢𝘴 𝘢 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘰𝘳 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘨𝘪𝘷𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘮𝘦 𝘩𝘪𝘮. 𝘓𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘩𝘦𝘺, 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘭𝘰𝘴𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘯𝘰𝘸 𝘴𝘶𝘥𝘥𝘦𝘯𝘭𝘺 𝘐 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘩𝘪𝘮. 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘪𝘧 𝘢 𝘩𝘶𝘯𝘥𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘧𝘭𝘰𝘸𝘦𝘳𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘣𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘨, 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭𝘴 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘐'𝘮 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘨𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘩𝘪𝘮 𝘢𝘵 𝘢𝘭𝘭.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘖𝘣𝘷𝘪𝘰𝘶𝘴𝘭𝘺, 𝘺𝘰𝘶'𝘳𝘦 𝘨𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘪𝘵 𝘣𝘦 𝘥𝘰𝘯𝘦. 𝘔𝘺 -- 𝘮𝘺 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘴𝘦 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘦'𝘷𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘥𝘪𝘧𝘧𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘵, 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘺 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘊𝘭é𝘮𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘔𝘢𝘳𝘰𝘵.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨'𝘴 𝘣𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘤 𝘱𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵, 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦, 𝘢𝘯𝘺 𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘢 𝘶𝘯𝘪𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘦. 𝘛𝘩𝘦𝘺'𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘰𝘰 𝘣𝘪𝘨 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘩𝘦𝘯𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘪𝘳 𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘪𝘳𝘦𝘵𝘺, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘯𝘺 𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘭𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧, 𝘴𝘢𝘺, 𝘢 𝘱𝘰𝘦𝘮 𝘰𝘳 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘷𝘦𝘳 𝘪𝘴 𝘰𝘯𝘭𝘺 𝘨𝘰𝘯𝘯𝘢 𝘨𝘦𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘢 𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘺 𝘱𝘪𝘦𝘤𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘰𝘯, 𝘢 𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘺 𝘳𝘦𝘧𝘳𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘐 𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘯 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬, 𝘸𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘱𝘩𝘰𝘵𝘰𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘱𝘩 𝘰𝘧 𝘍𝘳é𝘥é𝘳𝘪𝘤 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘪𝘯. 𝘖𝘯𝘦 𝘱𝘩𝘰𝘵𝘰𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘱𝘩.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘱𝘪𝘤𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦 𝘩𝘦'𝘴 𝘴𝘤𝘰𝘸𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘨.

𝗗𝗛: 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘥𝘪𝘥 𝘍𝘳é𝘥é𝘳𝘪𝘤 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘪𝘯 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦? 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘴𝘮𝘪𝘭𝘦 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦? 𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘢𝘵 𝘢 𝘱𝘩𝘰𝘵𝘰𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘱𝘩 𝘰𝘧 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘪𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘴𝘢𝘺, "𝘖𝘩, 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘪𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘪𝘯 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬𝘦𝘥 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦." 𝘞𝘦𝘭𝘭, 𝘯𝘰. 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘪𝘯 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬𝘦𝘥 𝘭𝘪𝘬𝘦 𝘮𝘢𝘯𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴. 𝘌𝘷𝘦𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘥𝘢𝘺 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘱𝘩𝘰𝘵𝘰𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘱𝘩 𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘢𝘬𝘦𝘯, 𝘩𝘦 𝘩𝘢𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘥𝘪𝘧𝘧𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘰𝘯 𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘦. 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘯, 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘢 𝘺𝘦𝘢𝘳 𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘭𝘪𝘦𝘳 𝘰𝘳 10 𝘺𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘴 𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘭𝘪𝘦𝘳? 𝘐 𝘮𝘦𝘢𝘯, 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘪𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢 𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘭𝘦𝘹 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨. 𝘐𝘵'𝘴 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨. 𝘐𝘵'𝘴 𝘮𝘪𝘭𝘭𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘥𝘪𝘧𝘧𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘶𝘯𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘢𝘯𝘢𝘭𝘰𝘨𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘴𝘰𝘮𝘦𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘧𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘰 𝘢𝘴 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨.

𝗝𝗔: 𝘞𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘴𝘢𝘺 𝘸𝘦 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬𝘦𝘥 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘰 𝘪𝘵 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘶𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘵𝘸𝘰 𝘱𝘪𝘤𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘱𝘪𝘯, 𝘣𝘶𝘵 𝘩𝘦'𝘴 𝘬𝘪𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘴𝘤𝘰𝘸𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘯 𝘣𝘰𝘵𝘩. 𝘖𝘳 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘢𝘯'𝘵 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘺 𝘵𝘦𝘭𝘭 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘥 𝘰𝘯𝘦, 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘵𝘰𝘰 𝘥𝘪𝘴𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘦𝘥. 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘯𝘰 𝘴𝘮𝘪𝘭𝘦𝘴.

——

#douglas hofstadter#jad abumrad#robert krulwich#lynn levy#clement marot#radiolab#npr#poem#poetry#podcast#radio#august#2020#creator:wnycstudios.org;web#website#audio#adding to the internet

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is The Origin Of (239)?...

What Is The Origin Of (239)?…

Cock and bull story

If you visit the village of Stony Stratford in Buckinghamshire, near Milton Keynes, you will find two drinking establishments on the High Street, the Cock and the Bull. Conveniently situated on what was Watling Street, now the A5, the village was a popular resting spot for coach travellers travelling to and from London and the North. The locals were keen for gossip and local…

View On WordPress

#Clement Marot#cockalane#Jean Le fevre de Ressons#John Taylor the water poet#origin of cock and bull story#Randle Cotgrave#Robert Burton#Robert Nelson#Stony Stratford#The Anatomy of Melancholy#the Cock inn and the Bull inn#Thomas a Kempis

0 notes

Link

One of my favorite songs ever!

#music#early music#lute#tant que vivray#claudin de sermisy#clément marot#clement marot#baltimore consort#16th century#renaissance#french history#queue

0 notes

Quote

Plus ne suis ce que j'ai été

Et plus ne saurai jamais l'être

Mon beau printemps et mon été

Ont fait le saut par la fenêtre

Clément Marot

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marguerite had “the body of a woman, the heart of a man, and the head of an angel,” proclaimed the poet Clement Marot. Although she emerged as a key figure of the French Renaissance, Marguerite occupied a very different place in her mother’s world than Francis did. Louise’s Journal revolved around her “Caesar”; Marguerite was rarely mentioned. Her life was largely shaped by her status as the king’s devoted sister. When Francis disagreed with her over issues such as the marriage of her daughter or the persecution of Protestants, she deferred to his wishes or retreated. Her life was shaped decisively by the limits imposed on elite women: A marriage was arranged for her to a man in whom she had no interest and with whom she shared no interests; when she made a second marriage for love, that beloved husband freely pursued sexual adventures; and Marguerite’s relationship with her own daughter was largely defined by Francis’s diplomatic agenda. Despite these constraints on her personal life, Marguerite was an intellectual luminary and political figure in Francis’s court, and she attained great distinction as one of the most important writers of the French Renaissance. Marguerite was born on April 11, 1492, into the Angoulême family, whose fortunes fluctuated as their expectations of inheriting the throne waxed and waned with Anne of Brittany’s pregnancies and as Louis XII married his successive wives with greater or lesser prospects for fertility. Even more than the family’s position vis-à-vis the throne, Marguerite’s life was shaped by her position as moon to her brother’s sun. We know little of her early life except that she followed her family’s peregrinations from one royal chateau to another, spending time at her mother’s chateaux at Cognac and Romorantin and at the royal chateaux of Amboise and Blois. Her early environment allowed her interests and abilities to flourish. She benefited from the excellent education available to her brother and, indeed, was the more apt pupil. Marguerite grew up surrounded by the young men chosen by her mother as fitting companions for her brother and who later played important roles in the history of France. Several of them, including Gaston de Foix, a young love of Marguerite’s, and Guillaume de Bonnivet, died in Francis’s wars. Charles de Montpensier became the constable of Bourbon and betrayed his king. The most important of them, Anne de Montmorency, was a political advisor and military leader who served Francis and Francis’s son and grandsons. Several of these young men had a marked impact on Marguerite. Her relationship with them, according to scholars’ speculations, may be found, thinly disguised in fiction, in her best-known work, Heptameron. One story tells of a widow left with two children, a young prince and princess. Youthful love and trust was betrayed by assaults on the princess’s virtue. The princess Florinde fell in love with a stunningly handsome young prince who died in battle. Another young man, Amadour, consoled her and became her confidant. He married one of the princess’s friends to remain close to her and then went to war. While he was away, the princess married another. When Amadour returned after the death of his wife, he first tried to persuade the princess that marriage made extramarital relationships permissible. He then tried to take her by force, despite her vociferous objections. She thwarted him again by deliberately bruising her face so badly that he would not find her attractive. When he nonetheless attacked her again, her cries brought her mother, and Amadour was forced into exile. Another story tells of a similar attack. In this version, the aggressor is housed in a room below the princess’s, connected by a trapdoor. But the princess and her maid lie in wait for him. When he invades her room, they beat him so severely that he is forced to absent himself to avoid explaining his battered appearance. Marguerite’s biographers concede that these stories are not conclusively autobiographical. However, there seems to be sufficient correlation between her life and these stories to suppose that Foix was the handsome young prince, as he was both her early love and killed at the battle of Ravenna (1512), and that Bonnivet was the confidant turned attacker. Whether autobiographical or not, these storied expose the vulnerability of women, even those like Marguerite at the top of the social hierarchy. Her personal experience of sexual assault may well explain the prominence of rape in the Heptameron. Marguerite’s personal life, like that of other royal women, was shaped by the marriage alliance made for her—a decision in which she actually had greater say than many of her contemporaries. Her situation was complicated by the fact that, during the years in which a marriage would likely be arranged, it was not clear whether she would be simply the sister of a prestigious but impoverished French nobleman or of the king of France. When marriage to Marguerite was proposed to Arthur, the oldest son of Henry VII of England, he preferred a king’s daughter over a prospective king’s sister and so chose Catherine of Aragon. After Arthur’s death, Marguerite was proposed for his brother, the future Henry VIII, but it was still not certain that Francis would inherit the throne. A royal marriage for Marguerite would have given too much power to the Angoulême family if Francis were not the heir to the throne. Other marriages would have given undue influence to a mere nobleman should he then be married to a king’s sister. Marguerite was not an entirely passive bystander. When Louis XII proposed the English Prince Henry, Marguerite objected to being sent to a foreign land. Surely, she contended, she could find a young, rich, noble husband without crossing the English Channel. Ultimately, the selection of Marguerite’s husband was made in the crown’s narrowest interests. In 1508, she married Charles, the duke of Alençon, a match Louis XII arranged to settle a legal dispute between the crown and the duke. Charles derived great benefit from Marguerite’s status. Once Francis became king, Charles had the status of second gentleman of the kingdom, with the attendant prerogatives. Nothing about the arrangement served Marguerite’s interests, and her situation was quite uncongenial. She was separated from home and family at the age of sixteen to go to her husband’s estates in Normandy. Her spouse had been reared in relative poverty and isolation by a widowed mother. A feudal warrior with no intellectual interests, he was, by all accounts, remarkably undistinguished. Thus, Marguerite, a paragon of Renaissance learning and culture, married a feudal military man on whom the Renaissance had made no impression. She lived in the cultural backwater of Alençon, where the chateau was an austere feudal structure without the stylistic benefits or creature comforts of the Renaissance. Marguerite’s devout mother-in-law had worked to preserve her son’s estates, but their household was impoverished. Despite her difficult circumstances, Marguerite’s exposure to this environment might well have awakened or heightened her religious devotion. Marguerite’s life dramatically changed with Francis’s accession to the throne. He summoned her to court, where she became one of its greatest ornaments and a central figure in promulgating the Renaissance in a French setting. She also took on significant political missions, represented the king in the provinces, marshaled troops, and supervised construction projects. These activities demonstrated that Francis trusted her to act in his stead in a variety of contexts. An Italian ambassador acknowledged her influence: “The sister knows all the secrets but speaks little, what a most beautiful woman.” The duke of Suffolk advised his brother-in-law Henry VIII to write affectionately to Marguerite to curry her brother’s favor. She also received foreign ambassadors, as when the English ambassador came to arrange a marriage between the newborn dauphin and Mary Tudor. Because Queen Claude was both retiring and frequently pregnant, Marguerite performed the public offices of her sister-in-law, often serving as Francis’s official hostess. Marguerite played an important role in the royal household, overseeing the education of her nieces and nephews after Claude’s death. In recognition of her many services, Francis settled a pension on Marguerite, which gave her a measure of financial independence. Even more significant was his gift of the duchy of Berry and his elevation of that duchy to one conferring the status of peer of the realm on its holder. As there were only twelve peers at a time and very few of them throughout the sixteenth century were women, this position alone gave Marguerite an extraordinary official status. With a seat on the royal council, she was consulted by the king about the most important issues of the day. As her correspondence documents, she directed administrative and religious offices in her territories and acted as an effective patron of the nobles of her duchy. Marguerite’s activities enhanced Francis’s reputation as a paragon of the Renaissance. The famous Italian humanist Castiglione acknowledged Francis as “the mirror of graces and good education . . . much in contrast to the practices in France.” Francis was interested in humanism, but his sister was a scholar of true distinction and an outstanding exemplar of the roles women could play in courtly humanism. Castiglione’s famous depiction of the court of Urbino in The Book of the Courtier not only made the court central to the transmission of humanism but also made women the crucial agents in moderating male culture by transforming the feudal warrior into the Renaissance man. While Anne of Brittany’s court had a circle of devout women, it was not a venue where men and women enjoyed each other’s company. Francis’s distinctively Renaissance court appreciated women and made them central to its activities. Marguerite was a particularly apt French rendition of Castiglione’s Elisabetta Gonzaga—a paragon of virtue and learning in a royal court. But Marguerite was not simply, on the Italian model, a woman who orchestrated the conversation of men; she pursued her own intellectual interests and defined the literature of the French Renaissance. The early years of Francis’s reign offer glimpses into Marguerite’s interest in religious reform. Some of her ideas became central to the emergence of Protestantism in France. Initially, Francis gave her full rein. Intrigued by new ideas, he himself did not take a definitive stand until he perceived the reformers as a political threat. After hearing Guillaume Briçonnet, bishop of Meaux, preach, Marguerite corresponded extensively about theological issues with him. He became one of the most notable guides to her religious development. Briçonnet encouraged her interest in religious reform and urged her to get involved in nominating bishops, no doubt seeing her as a powerful ally for his reformminded community. Those who advocated the reform of the Church could remain completely orthodox, and many of them espoused ideas associated with the growing reform movement within the Catholic Church called Christian humanism. Christian humanists, like other Renaissance humanists, studied classical texts and applied philological methods to purify these texts of their medieval accretions; they focused particularly on early Christian texts. Their studies revealed glaring inconsistencies between the practices, beliefs, and structure of the early Church and those of the Renaissance Church. While calls for reform based on this understanding of early Christianity could be and were launched from within the Church, espousing these ideas became more problematic once the Church had condemned Luther’s ideas. Those committed to reform then found it more difficult to define a position distinct from Luther’s. Calls for reform were increasingly construed as direct attacks on the Church. Marguerite was deeply sympathetic to both the ideas and the proponents of religious reform. She saw the new movement as a way to purify Catholicism and return it to its early, apostolic roots. She advocated the reform of monasteries and convents and had reformed several on her lands already by 1520. She remained unflinchingly critical of the corruption of monasteries—a central theme of the Heptameron. Her strong commitment to charitable institutions led her to inaugurate a system of public assistance in hospitals in Alençon and in Paris. Marguerite was also formidable enough in debating the theological complexities underlying the Reformation to be perceived as a threat by the theology faculty of the Sorbonne. Francis’s defeat and subsequent imprisonment after Pavia propelled Marguerite into the arena of international diplomacy. Pavia also altered her personal circumstances. Not only did her husband fail to distinguish himself in battle, but, when wounded, he fled ignominiously and died in disgrace shortly thereafter. (Many years later, Marguerite wrote a six-thousand-verse poem, The Prisons, commenting sympathetically on his disgrace.) As the affairs of state required Louise to remain in France, Marguerite went as the key negotiator with Charles V over the fate of Francis, then held in a Spanish prison. Marguerite found her brother unconscious and near death and warned her mother to expect the worst. Constantly at prayer, she stayed by his side until his fever finally broke twenty-three days later. Marguerite negotiated with the emperor for more than three months. She allied with Charles’s sister, Eleanor of Austria, who entertained a notion of Francis as a romantic hero. Marguerite played on this sentiment to gain better treatment for her brother and promoted the marriage between Eleanor and Francis to gain his release. While she was in Spain, Francis decreed that if anything happened to his mother, Marguerite would be his regent. Although ultimately given safe passage, Marguerite was mistrustful enough to fear that the emperor might detain her as a hostage. While Marguerite was in Spain, religious hostilities in France increased. The group at Meaux took a more belligerent stance toward the Church, destroying a papal bull on indulgences and replacing it with a text criticizing the pope as the anti-Christ. The theology faculty of the Sorbonne took advantage of Francis’s imprisonment to reassert its authority as a vigilant guardian of orthodoxy. It scrutinized the writings of advocates of Church reform, condemning as heretical the works of both Luther and the Christian humanist Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples. Parlement was also mobilized to carry out the Sorbonne’s wishes in the judicial venue, prosecuting those the Sorbonne condemned. Even though Francis had previously intervened on Lefèvre’s behalf, Parlement forced him into exile for the duration of Francis’s imprisonment. When Parlement condemned the celebrated humanist Louis de Berquin to death, he was saved only by Marguerite’s personal intervention. (When Berquin was later convicted again, the death sentence was hastily carried out to prevent royal intervention.) Francis’s eventual release from prison was a reprieve for reformers. Lefèvre, for example, was recalled from exile to serve as tutor to Francis’s sons. When Francis returned from Spain, he credited Marguerite with saving his life during his illness and with negotiating so conscientiously on his behalf. He showered her with gifts, and she was clearly in very high standing. As a widow and now undeniably the sister of the king of France, Marguerite could play a valuable diplomatic role in new marriage negotiations. But when she married again in 1527, she chose a husband for love—Henry d’Albret, the king of Navarre. This marriage afforded Francis only modest political advantage, shoring up the border between France and Spain. Likely Francis allowed this politically less-advantageous match in deference to Marguerite’s personal feelings. Henry could be considered an appropriate husband for a royal princess, for he was a king, albeit a territorially disadvantaged one. He had lost much of his land when Ferdinand and Isabella* of Spain seized part of Navarre in 1512, and Charles V took Béarn, another part of his territory. For a land-poor king, an alliance with the king of France’s sister was a tremendous advantage; Henry became, as a result, one of the greatest lords of France. As queen in Navarre, Marguerite continued to play a direct role in the politics and diplomacy and to correspond with many important European figures on both political and theological issues. While this marriage was happier than Marguerite’s first, it too had its humiliations. At the age of thirty-five, Marguerite was passionately in love with this new husband, twelve years her junior. Young and handsome, Henry had distinguished himself at the Battle of Pavia. He shared her interest in Renaissance arts, and they were bound by their mutual antipathy toward the emperor. Henry hoped marriage to the king’s sister would lead to the recovery of his lost lands with Francis’s support. (He had previously proposed marriage to Charles’s sister Eleanor, expecting his lost lands as her dowry.) But Marguerite’s marriage for love did not bring her great personal happiness, and she found her new situation less than ideal. The court in Navarre was provincial, and her husband was concerned most with protecting his remaining territory. After an initial period of happiness, she became disillusioned as Henry pursued sexual relationships with other women. Marguerite’s correspondence documents her requests to ask others to bring him to heel. Francis was forced to demand that he treat her as her rank required. Henry demonstrates some of these undesirable traits through the words Marguerite puts into the mouth of her character Hircan (a play on his name in Gascon, the language of Navarre) in the Heptameron. As the book’s characters reflect on the meaning of the stories they told to their group of stranded travelers, Hircan inevitably asserts the greatest male prerogative and disdain for women. He is cynical about women’s motives and the depth of their love, claiming, for example, that women act not from love but rather in women’s ways, which are “resentful, bitter, and vindictive.” He appreciates the cleverness of men in overcoming the scruples of women about sexual relations; if women resist, “men turn to trickery.” Men have no call to defer to women, he insists, because “women are made for men.” Although other speakers challenge his views, Hircan presents a crass and overweening sense of male privilege, and his character seems to argue for Marguerite’s increasing unhappiness in her marriage. Despite the difficulties of her marriage, Marguerite gave birth to her daughter, Jeanne, in 1528 to her great joy. At the age of thirty-six, Marguerite was a rather old first-time, sixteenth-century mother. Her first marriage had been childless, and her second occurred after she had already likely entered a period of diminished fertility. In addition to her daughter, she bore a son in 1530 who died at the age of six months, and she had several recorded miscarriages. She grieved over the death of her son and desperately longed for more children. At the age of fifty, she fell ill but believed that she was again pregnant. When Jeanne was just two years old, Francis took her to be raised at the chateau of Plessis-les-Tours so that her father could not use her to recoup his Spanish territory through a Hapsburg marriage alliance for her. Well aware that this was his brother-in-law’s greatest interest, Francis both wanted to prevent Henry from bartering his own daughter for his former lands and intended to use his niece instead to advance his own political agenda. As a result, Marguerite was separated from her daughter for most of her life. While her mother was alive, Marguerite played important social, political, and cultural roles at her brother’s court and acted as Louise’s political and diplomatic agent, working with her to negotiate the Ladies’ Peace. After her mother’s death in 1531, Marguerite took over many of Louise’s official functions. She traveled extensively, pursuing the king’s as well as her own interests, going to Amiens to reform a Franciscan convent, to Normandy when the dauphin Francis was proclaimed governor, and to Rouen with the new queen, Eleanor, on her triumphal entry. Marguerite was greatly involved with Francis’s children, especially in arranging marriages for them. She shared her brother’s enthusiasm for building and commissioned two Renaissance chateaux at Nérac and Pau in Navarre. For the last sixteen years of Francis’s reign, she was one of Francis’s most significant confidants. The Venetian ambassador Matteo Dandolo praised Marguerite as the wisest of all (not merely the wisest woman). In 1540 he reported that she was constantly with the king and proclaimed “in the affairs and interests of state, one can have no surer discourses than hers.” Although Francis relied on Marguerite, she was sometimes at odds with him over politics or religion. These disagreements increasingly became serious enough that she periodically fled the court when she could not condone her brother’s actions. Kathleen Wellman, “Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France”

*the author is wrong here, Isabella died in 1504, so she couldn’t participate in the conquest of Navarre in 1512

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

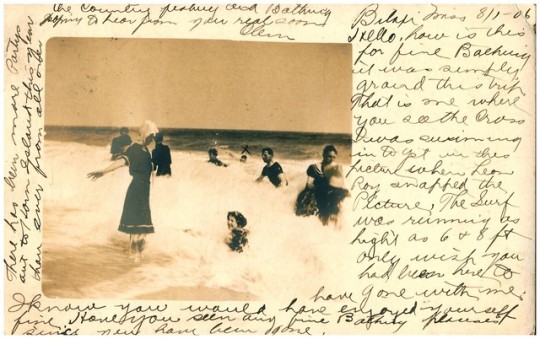

Postcard addressed to Miss Annie N. Griffin, Hotel West End. Rue Clement Marot, Paris, France. Postmarked July 31, 1906. Found, Jackson, Mississippi.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Festivalul Internațional ”George Enescu”: De la Weber la Enescu (luni, 9 septembrie 2019, București)

Festivalul Internațional ”George Enescu”: De la Weber la Enescu (luni, 9 septembrie 2019, București)

Un recital cameral cu lucrări de Enescu, Brahms și Franck deschide programul zilei luni, 9 septembrie 2019, în Festivalul Internațional ”George Enescu”, la ora 17.00 la Ateneul Român. Protagoniști:

Alexander Kniazev (violoncel) și Plamena Mangova (pian). Program: Enescu, Sonata I în fa minor pentru violoncel și pian, op. 26 nr. 1, Brahms, Sonata nr. 2 în fa major pentru violoncel și pian, op. 99

View On WordPress

#București#Clement Marot#cultură#eveniment#Festivalul Enescu 2019#Freischutz#muzică clasică#muzică de operă#poezie#Staatskapelle Dresden#știri

0 notes

Text

« Je suis aimé de la plus belle

Qui soit vivant dessous les cieux :

Encontre tous faux envieux

Je la soutiendrai être telle.

Si Cupido doux et rebelle

Avait débandé ses deux yeux,

Pour voir son maintien gracieux,

Je crois qu'amoureux serait d'elle.

Vénus, la Déesse immortelle,

Tu as fait mon coeur bien heureux,

De l'avoir fait être amoureux

D'une si noble Damoiselle ».

Je suis aimé de la plus belle de Clément Marot.

0 notes

Text

La première de Le roi s'amuse,cont

more from Jehan Valter; this is further along , and the play and its reception are starting to go off the rails:

Unfortunately, the spectators of the parterre and the amphitheater recommenced their jokes during the intermission; appealing to the tenants of the lodges and the balcony, already ill-disposed to the author (Hugo).

Messrs. Arnault pere and his sons, Jouy, Jay, and Viennet, who had signed a passionate protest against the Romantics some time before, were particularly beset. We* sang on the air of Malborough:**

The academy is dead,

Mironton tone your mirontaine,

The academy is dead,

Is dead and buried.

By the time the curtain was about to rise on the second act, a shower of small papers thrown from the third gallery fell unexpectedly onto the audience of the orchestra and the lower galleries. It was Jean Journet "the apostle" who thus announced to the world by printed flyers that a new religion had just been founded and that he was the founder.

Reading these little papers put the whole room in a good mood. We laughed again when the second act began. But the laughter stopped abruptly from the first few verses of the monologue of Triboulet.

This old man cursed me ...

And they changed into enthusiastic bravos from the scene where the unfortunate father said to his daughter:

Oh ! do not wake up a bitter thought.

The verse :

And what would you say if you saw me laughing?

shuddered the whole room. Friends and enemies of the author met in a single ovation. The end of the act went less well. People say- but nothing proves it and I like to doubt it- Samson (Clement Marot), dissatisfied with playing only one end of a role***, deliberately misplaced the band over Triboulet's eyes, and also deliberately forgot the following two explanatory verses:

You can scream high and walk with a heavy step.

The blindfold that makes him blind and deaf.

So that it was not explained how Triboulet did not see that the ladder was applied against the wall of his house and how he did not hear the cries of his daughter. The audience of the lodges burst out laughing.

In addition, Blanche's abduction was as awkward as possible. Mademoiselle Anais was swept upside down with her legs in the air, and the second act ended amid laughter and whistling.

During the passage, Jehan Duseigneur**** ascended to the third gallery, where he had a lively explanation with Journet. Going down, he had to cross the home a group of Lesguillon, Charles Maurice Henri Beyle and a few others, all opponents of the author. The group was heavily eroding the room, that goes without saying.

"Down with the fools!" said the Romantic sculptor energetically.

Nobody answered him and he regained his place proudly.

* This isn’t the first time Valter’s talked about the Romantics as “we” and given his name , it’s likely he really was part of the crew. If so , this pamphlet on Le Roi s’amuse,started as a running article in Le Figaro, is the only writing of his that seems to have survived--though of course it’s possible he has other columns buried in old newspaper articles and the like.At any rate, this is the whole evidence of him that I’ve found, so sadly I can’t give more info on him! But there’s another Jehan for the Romantic Army ; maybe he was a footsoldier and not a lieutenant, but obviously the sense of camraderie stuck with him too.

**Obviously, filking the same song Petrus and his group were singing at the start of the play

*** I am really not sure what this means??

****Duseigneur!! Besides being one of the main hosts of the Jeunes-France, he was the guy who did his hair up like a flame to symbolize THE FLAME OF GENIUS. A noticeable guy, a big success in his art, and well liked, but mostly without speaking lines in histories of the movement--this is fun to see!

Malheureusement, les spectateurs du parterre et de l'amphithéâtre recommencèrent leurs plaisanteries pendant l'entr'acte; interpellant les locataires des loges et du balcon, déjà mal disposés pour l'auteur.

MM. Arnaultpère et fils, Jouy, Jay et Viennet, qui avaient signé quelque temps auparavant une protestation passionnée contreles romantiques, étaient particulièrement pris à partie. On chantait sur l'air de Malborough :

L'académie est morte,

Mironton ton ton mirontaine,

L'académie est morte,

Est morte et enterrée.

Au moment où le rideau allait se lever sur le second acte, une pluie de petits papiers lancés de la troisième galerie tomba à l'improviste sur le public de l'orchestre et des galeries inférieures. C'était Jean Journet « l'apôtre » qui annonçait ainsi au monde par prospectus imprimés qu'une religion nouvelle venait de se fonder et qu'il en était, lui, le fondateur.

La lecture de ces petits papiers mit la salle entière en belle humeur. On riait encore lorsque commença le deuxième acte. Mais les rires cessèrent brusquement dès les premiers vers du monologue de Triboulet.

Ce vieillard m'a maudit...

Et ils se changèrent en bravos enthousiastes à partir de la scène où le malheureux père dit à sa fille :

Oh ! ne réveille pas une pensée amère.

Le vers :

Et que dirais-tu donc si tu me voyais rire ?

fit frissonner toute la salle. Amis et ennemis de l'auteur se réunirent dans une même ovation. La fin de l'acte marcha moins bien. On prétend— mais rien ne le prouve et j'aime mieux en douter— que Samson (Clément Marot), mécontent de ne jouer qu'un bout de rôle, fit exprès de mal placer le bandeau sur les yeux de Triboulet, et fit également exprès d'oublier les deux vers explicatifs qui suivent :

Vous pouvez crier haut et marcher d'un pas lourd.

Le bandeau que voilà le rend aveugle et sourd.

De sorte qu'on ne s'expliqua pas comment Triboulet ne voyait pas que Péchelle était appliquée contre le mur de sa maison et comment il n'entendait pas les cris de sa fille. Le public des loges éclata de rire.

En outre, l'enlèvement de Blanche se fit aussi maladroitement que possible. M" e Anaïs fut emportée la tête en bas et les jambes en l'air. Le deuxième acte finit au milieu des rires et des sifflets.

Pendant Tentr'acte, Jehan Duseigneur monta à la troisième galerie où il eut une vive explication avec Journet. En redescendant, il dut traverser au foyer un groupe composé de Lesguillon, de Charles Maurice, de Henri Beyle et de quelques autres, tous adversaires de l'auteur. Le groupe éreintait fortement la pièce, cela va sans dire.

— A bas les stupide! si cria énergiquement le sculpteur romantique.

Personne ne lui répondit et il regagna fièrement sa place.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Muzicianul care a făcut istorie cu vocea sa baritonală. A fost nevoit să îşi schimbe numele din cauza celui ales de părinţi – VIDEO

Johnny Cash s-a nascut la data de 26 Februarie 1932 si a decedat la 12 Septembrie 2003.

Citeşte şi O farsă ar fi putut să pună capăt carierei de scriitor a lui Mark Twain

Citeşte şi Ce citeşte Barack Obama? Surprizele de pe lista lui de lectură

A fost un cantaret si compozitor de muzica country, castigator a mai multor premii Grammy. Cash este considerat a fi unul dintre cei mai importanti muzicieni americani ai secolului XX.

Cash a fost cunoscut pentru vocea sa baritonala, pentru atitudinea sa si pentru imbracamintea de culoare neagra ce i-a adus porecla de „The Man in Black” („Omul in Negru”). Isi incepea concertele cu formula introductiva „Hello, I’m Johnny Cash” („Buna, sunt Johnny Cash”). Printre cele mai cunoscute cantece ale sale se numara: I Walk the Line, Folsom Prison Blues, Ring of Fire, Get Rhythm sau duetul cu June Carter, intitulat Jackson.

youtube

A vandut peste 90 de milioane de albume in cei aproape 50 de ani de cariera si a ajuns sa ocupe „un loc de frunte in istoria muzicii”.

Johnny Cash, pe numele sau adevarat J.R. Cash, s-a nascut in Kingsland, Arkansas, fiind fiul lui Ray si Carrie (nascuta Rivers) Cash, si a copilarit in Dyess, Arkansas. Cash a fost botezat J.R. deoarece parintii sai nu au cazut de comun acord asupra unui nume, ci doar asupra initialelor. Cand s-a inrolat in Aviatia Statelor Unite, a fost nevoit sa adopte numele de John R. Cash, deoarce armata nu accepta numai initialele ca nume. In 1955, a semnat un contract cu Sun Records, si si-a luat numele de scena Johnny Cash.

Pe cand se afla in perioada de antrenament la baza de aviatie, Cash a cunoscut-o pe Vivian Liberto, la data de 18 Iulie 1951. La o luna dupa ce a fost lasat la vatra, pe 7 August 1954, s-au casatorit la Biserica Catolica St. Anne din San Antonio. Au avut impreuna patru fiice: Rosanne (nascuta la 24 Mai 1955), Kathleen „Kathy” (nascuta la 16 Aprilie 1956), Cynthia „Cindy” (nascuta la 29 Iulie 1958) si Tara Joan (nascuta la 24 August 1961).

La inceputul anilor ’60, Cash a plecat intr-un turneu impreuna cu familia Carter, ale carei membre erau Anita, June si Helen. June, care ulterior i-a devenit sotie lui Cash, isi amintea cum il admira pe Johnny de la distanta in timpul turneului. In anul 1997, Cash a fost diagnosticat cu sindromul Shy-Drager. Acest diagnostic a fost schimbat dupa aceea in neuropatie diabetica. Aceasta afectiune l-a impiedicat sa isi sustina concertele pe care le avea in acea perioada. June Carter Cash a decedat la 15 Mai 2003, la varsta de 73 de ani.

Descoperă îţi prezintă principalele semnificaţii istorice ale zilei de 12 septembrie:

1544 – A încetat din viaţă Clement Marot, poet renascentist, traducător al Psalmilor lui David: „Adolescenţă indulgentă” (n. 1496).

1883 – S-a născut dr. Constantin Ionescu-Mihăieşti, microbiolog şi imunolog, organizator, împreună cu dr. Ioan Cantacuzino, al Institutului de seruri şi vaccinuri din Bucureşti (m. 14 aprilie 1962).

1888 – S-a născut Maurice Chevalier, actor francez (din filmografie: “Văduva veselă”, “Tăcerea e de aur”) (m. 1 ianuarie 1972).

1897 – S-a născut Irène Joliot-Curie, fiica celebrilor Pierre şi Marie Curie, fizician şi chimist, distinsă, împreună cu soţul ei, Frederic Joliot, cu Premiul Nobel pentru Chimie pe anul 1935; a fost membru de onoare străin al Academiei Române (m. 17 martie 1956).

1913 – S-a născut Jesse Owens, celebru atlet de culoare supranumit “torpila umană”; la Olimpiada din 1936 (Berlin) a câştigat 4 medalii de aur (m. 31 martie 1980).

1921 – S-a născut scriitorul Stanislav Lem, promotor al literaturii science-fiction (romanul “Solaris”, ecranizat în 1972 de regizorul Andrei Tarkovski) (d. 27 martie 2006).

1944 – S-a născut Barry White, solist vocal, producător şi compozitor american (m. 4 iulie 2003).

1981 – A încetat din viaţă Eugenio Montale, poet şi jurnalist, iniţiator al poeziei ermetice italiene; a primit Premiul Nobel pentru Literatură în 1975: “Oase de sepie”, “Ocazii” (n. 12 octombrie 1896)

1992 – A încetat din viaţă actorul Anthony Perkins: „Psycho”, „Crima din Orient Expres” (n. 1932).

1997 – A încetat din viaţă scriitoarea canadiană Judith Merril (Judith Josephine Grossman), una din primele femei devenite celebre ca autoare de SF: “Shadow on the Hearth”, 1950, roman despre războiul nuclear, a fost adaptat pentru televiziune (n. 21 ianuarie 1923).

2007 – IPS Daniel a fost validat în funcţia de patriarh al Bisericii Ortodoxe Române.

Articolul Muzicianul care a făcut istorie cu vocea sa baritonală. A fost nevoit să îşi schimbe numele din cauza celui ales de părinţi – VIDEO apare prima dată în Descopera.ro.

0 notes