#David Weininger

Text

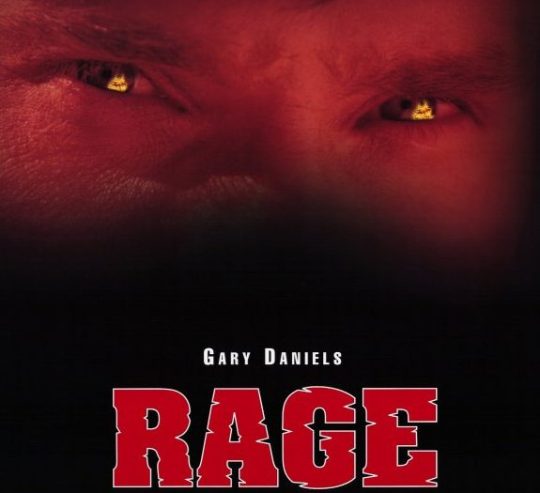

Rage (1995)

Directed by Joseph Merhi, Rage stars Gary Daniels as Alex Gainer, a husband, a father and second grade teacher. He is such a nice dad he sings ‘The Wheels on the Bus’ to his daughter while driving his daughter to her friends’ place for a sleep over. Suddenly a man on the run from the law dives into Alex’s car and forces his to speed away at gunpoint. With the Police chasing Alex has no choice and…

View On WordPress

#Anthony Backman#Barry Nolan#Bob Minor#Charles A. Tamburro#Chuck Butto#David Powledge#David Weininger#Denney Pierce#Doren Fein#Emilio Rivera#Fiona Hutchison#Gary Bullock#Gary Daniels#Gary Imhoff#Jefferson Wagner#Jillian McWhirter#Joseph John Barmettler#Joseph Merhi#Judith Marie-Bergan#Kenneth Tigar#Luis Beckford#Mark Metcalf#Peter Jason#Ramon Sison#Raymond Fitzpatrick#Rick Avery#Rod Britt#Tim Colceri#Tracey Flint#Trent Hopkins

0 notes

Text

Michael A. Peters, Wittgenstein and the ethics of suicide: Homosexuality and Jewish self-hatred in fin de siècle Vienna, 51 Edu Phil & Theory 981 (2019)

If suicide is allowed, then everything is allowed. If anything is not allowed, then suicide is not allowed. This throws a light on the nature of ethics, for suicide is, so to speak, the elementary sin. And when one investigates it is like investigating mercury vapours in order to investigate the nature of vapours. —Wittgenstein, L. Notebooks 1914–1916, Tr. G.E.M. Anscombe. Harper: New York, 1961, p. 91

Introduction

One of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s cousins and three of his four brothers committed suicide. Hans committed suicide most likely throwing himself from a boat in Chesapeake Bay in May 1902, having run away from home. Rudi committed suicide in a Berlin bar, administering himself cyanide poisoning in 1904, most probably because of homosexuality that he referred to as ‘perverted disposition’ in a suicide note. Kurt shot himself in 1918 at the end of the war when his troops deserted en masse.

The profound influences upon young Ludwig were the physicist Ludwig Boltzmann who committed suicide in 1906 and Otto Weininger, author of Sex and Character, who committed suicide in 1903. For the most part, these suicides were committed before Ludwig had turned 15. Young Ludwig was also profoundly influenced by Schopenhauer who he read while still at school. Schopenhauer denied that suicide was immoral and instead saw it as the last supreme act of freedom and assertion of the will in ending one’s life. In ‘On Suicide’ in Studies in Pessimism, Schopenhauer writes that none of the Jewish religions ‘look upon suicide as a crime’. Yet, these religious thinkers:

tell us that suicide is the greatest piece of cowardice; that only a madman could be guilty of it; and other insipidities of the same kind; or else they make the nonsensical remark that suicide is wrong; when it is quite obvious that there is nothing in the world to which every mail has a more unassailable title than to his own life and person.1 https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/s/schopenhauer/arthur/pessimism/chapter3.html

Schopenhauer remarks ‘the inmost kernel of Christianity is the truth that suffering – the Cross – is the real end and object of life. Hence Christianity condemns suicide as thwarting this end ... ’ As Jacquette (2000) notes, despite his profound pessimism Schopenhauer rejects suicide ‘as an unworthy affirmation of the will to life by those who seek to escape rather than seek nondiscursive knowledge of Will in suffering’ (p. 43). Young Ludwig while of Jewish origins was baptised a Catholic. It is well known that Wittgenstein loses his faith while still at school.

Wittgenstein entertained thoughts of suicide from his early teenage years throughout his life. This suicidal ideation came to the fore even more intensely, if we are to judge from his letters to Paul Englemann, during the years he spent as an elementary school teacher in the mountain villages of Austria. In the period 1919 when he trained as a teacher until 1926 when he abruptly resigned after hitting a boy who fell unconscious as a result, Wittgenstein suffered intense bouts of depression (Peters, 2017).

This essay is devoted to the question: in view of his suffering and the Jewish cult of suicide in fin de siecle Vienna why did Wittgenstein not take his own life? I investigate this question focusing on Wittgenstein’s sources of suffering around what I call his ‘double identity crisis’ caused by his homosexuality and his Jewish self-hatred.

Identity crisis; suicide in Vienna

Under the heading ‘Suicide Squad’ Jim Holt (2009) reviewing Alexander Waugh’s The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War begins rather sensationally with the following:

“A tense and peculiar family, the Oedipuses,” a wag once observed. Well, when it comes to dysfunction, the Wittgensteins of Vienna could give the Oedipuses a run for their money. The tyrannical family patriarch was Karl Wittgenstein (1847-1913), a steel, banking and arms magnate. He and his timorous wife, Leopoldine, brought nine children into the world. Of the five boys, three certainly or probably committed suicide and two were plagued by suicidal impulses throughout their lives. Of the three daughters who survived into adulthood, two got married; both husbands ended up insane and one died by his own hand. Even by the morbid standards of late Hapsburg Vienna these are impressive numbers. But tense and peculiar as the Wittgensteins were, the family also had a strain of genius. Of the two sons who didn’t kill themselves, one, Paul (1887-1961), managed to become an internationally celebrated concert pianist despite the loss of his right arm in World War I. The other, Ludwig (1889-1951), was the greatest philosopher of the 20th century. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/01/books/review/Holt-t.html

At the end of World War I, troops under the command of Wittgenstein’s second oldest brother, Kurt, rebelled against his orders, and Kurt became the third brother to commit suicide. This is how Waugh describes the suicide of Rudi, a 22-year-old chemistry student at the Berlin Academy:

At 9.45 on the evening of May 2, 1904, Rudi walked into a restaurant-bar on Berlin’s Brandenburgstrasse, ordered two glasses of milk and some food, which he ate in a state of noticeable agitation. When he had finished, he asked the waiter to send a bottle of mineral water to the pianist with instructions for him to play the popular Thomas Koschat number, Verlassen, verlassen, verlassen bin ich. As the music wafted across the room, Rudolf took from his pocket a sachet of clear crystal compound and dissolved the contents into one of his glasses of milk. The effects of potassium cyanide when ingested are instant and agonising: a tightening of the chest, a terrible burning sensation in the throat, immediate discoloration of the skin, nausea, coughing and convulsions. Within two minutes Rudolf was slumped back on his chair unconscious. The landlord sent customers out in search of doctors. Three of them arrived, but too late for their ministrations to take effect. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/3559463/The-Wittgensteins-Viennese-whirl.html

His father forbade any mention of Rudolf in the Wittgenstein household, a decision that caused a rift between parents and children. Johannes ‘Hans’ the eldest son had died in a canoe- ing incident in America. As Waugh (2010: 29) writes: ‘the most likely scenario is that he did indeed commit suicide somewhere outside Austria, that the family had prior intimations, or direct warnings, of his suicidal intent, and that the spur that induced them to declare openly that he had taken his life was the very public death in Vienna, on October 4, 1903, of a 23-year-old philosopher called Otto Weininger. Weininger’s suicide caused a significant stir in Viennese society. The newspapers ran pages of commentary about him, and his reputation rose from that of obscure controversialist to national celebrity in a matter of days. All the Wittgensteins read his book.’

Weininger (1903/2005) had a profound influence on Wittgenstein through his notorious Sex and Character that he wrote and published in 1903. The book argues that all people are fundamentally bisexual and all individuals are composed of a mixture - the male aspect is active, productive, conscious and moral/logical, while the female aspect is passive, unproductive, unconscious, amoral and alogical. While emancipation is only possible for ‘masculine women’ it is the duty of the male to strive to become, a genius forging sexuality for the abstract love of God in which he can find himself. He was a Jewish convert to Christianity, and Weininger analysed Jewishness in terms of feminine qualities, later used by the Nazis. Weininger was a tormented soul who became a cult figure influencing a wide range of people. His genius was acknowledged by ‘Ford Maddox Ford, James Joyce, Franz Kafka, Karl Kraus, Charlotte Perkins- Gilman, Gertrude Stein, and August Strindberg’ as well as William Carlos Williams, Freud and Hitler (Stern & Szabados, 2004). He was a deep misogynist, an anti-Semite and self-loather (Rider, 2013). He also deeply influenced Wittgenstein, who writes:

I think there is some truth in my idea that I am really only reproductive in my thinking. I think I have never invented a line of thinking but that it was always provided for me by someone else & I have done no more than passionately take it up for my work of clarification. That is how Boltzmann Hertz Schopenhauer Frege, Russell, Kraus, Loos Weininger Spengler, Sraffa have influenced me. (CV, 16)

Engaging the work of Otto Weininger (1880–1903), one of the most widely discussed authors of fin-de-siece Vienna, can help illuminate this sense of a ‘crisis of the subject’ and its relation- ship to the world that informed so much of Vienna’s cultural production and debate at the time. Of all the books Wittgenstein read in his adolescence Weininger’s Sex and Character has the greatest influence (Monk 1990, p. 25). Achinger (2013, p. 121) reads Weininger through the lens of Critical Theory to suggest ‘viewing “the Woman” and “the Jew” as outward projections of different, but related contradictions within the constitution of the modern subject itself.’ She goes on to argue:

More specifically, “Woman” comes to embody the threat to the (masculine) bourgeois individual emanating from its own embodied existence, from “nature” and libidinal impulses. “The Jew,” on the other hand, comes to stand for historical developments of modern society that make themselves more keenly felt towards the end of the nineteenth century and threaten to undermine the very forms of individuality and independence that had previously been produced by this society. Such a reading of Geschlecht und Charakter not only can help illuminate the crisis of the bourgeois individual at the turn of the twentieth century, but also could contribute to ongoing discussions on why modern society, although based on seemingly universalist conceptions of subjectivity, continues to produce difference and exclusion along the lines of gender and race.

Certainly, such a critical interpretation coheres with the reading of a ‘double identity crisis’ facing the younger Wittgenstein growing up in fin d’siecle Vienna. Le Rider (1990) argues ‘The crisis of the individual, experienced as an identity crisis, is at the heart of all questions we find in literature and the humane sciences’ (p. 1) and remarks that ‘Viennese modernism can be interpreted as an anticipation of certain important ‘postmodern’ themes’ (p. 6). He has in mind, for instance, the way in which Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language ‘deconstructs the subject as author and judge of his own semantic intentions’ (p. 28). He remarks in terms of the crisis of identity how Wittgenstein, ‘like all assimilated Jewish intellectuals, found his Jewish identity a problem’ and the problem of his Jewish identity was coupled with a crisis of sexual identity, when at least at some periods of his life he sought refuge from his homosexual tendencies in a kind of Tolstoyan asceticism (p. 295). He suggests:

Wittgenstein, who ... looked back nostalgically on a well-ordered world where everyone had his place, found modernity uncultured because it had lost its power to integrate, and left individuals in a state of confusion. The only ones who can keep their balance and personal creativity are those whom Nietzsche calls the strong men, that is the most moderate, who need neither convictions nor religion, who are able not only to endure, but to accept a fair amount of chance and absurdity, and are capable of thinking in a broadly disillusioned and negative way without feeling either diminished or discouraged. (p. 296)

He argues that the consequences of this double crisis of identity, much more than is commonly accepted, are intimately tied up with the fundamentals of his thought and with a number of his intellectual preoccupations: his interest in Weininger and in psychoanalysis, his mystical tendencies, but also his reflections on genius, on the self, and on ethics^ı (p. 296). The importance that Le Rider(1993) places upon Nietzsche as part of the cultural fabric of Viennese modernism exericised upon a young Wittgenstein is borne out by other scholars of fin-de-siecle Vienna.

There is a kind of Wittgensteinian hagiography that for years has prevented the investigation of these questions which is of itself an interesting question in the anthropology of philosophy, especially that form of analysis that insists on a sharp separation between the man and the work. This line of argument suggests that the realm of ideas properly belongs to that of the mind that can be discussed dispassionately and in a technical way that pays attention to the space of arguments and the structure of argumentation; while the realm of biography belongs to that of the body, to the temporal dimension of existence emphasising its finitude. Thus, the mind-body dualism lives on and also prevents the influence of arguments and observations of psychobiography on philosophy per se.

Viennese Modernism has attracted much scholarly and public interest in recent decades, in part because some of the most enduring works of art, literature, and philosophy produced in Vienna around the turn of the last century question key concepts of liberalism and Enlightenment – such as the notions of progress, of the coherent and rational subject, and of a stable and unproblematic relationship between subject and world in which language is nothing but a neutral and transparent mediator – in ways that seem to prefigure contemporary debates. There are many stories of Jewish artists and philosophers who wrestled with identity issues in a hostile social and intellectual environment of Vienna sometimes internalising aspects of anti- Semitic ideology that no doubt propelled many to seek a new Christianised identity to help mask the transition. How Gustav Mahler, a Bohemian-Jewish artist of genius, responds to the challenges of a German culture that he has appropriated completely but into which he is never fully accepted is the subject of Niekerk’s (2013) Reading Mahler: German Culture and Jewish Identity in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna. Mahler was a frequent visitor to the Wittgenstein mansion when Wittgenstein was a boy. Mahler’s own artistic endeavours are determined by the complex responses to Goethe, the Romantics, Wagner, and, above all, Nietzsche and to rewrite German Romanticism at a time when German cultural history was dominated by Wagner’s anti-Semitic views. Another example is Fritz Waerndorfer who wanted to ‘His House for an Art Lover’ to ‘establish himself as an important participant in the Viennese avant-garde scene but also to promote a new artistic agenda’ and wished ‘to establish a new identity for himself as an assimilated Jew through the modernist redesign’ (Shapira, 2006).

Jewish self-hatred and homosexuality

The question of Jewish self-hatred has been an enduring issue for many years. Paul Reitter (2009: 359), author of The Anti-Journalist: Karl Kraus and Jewish Self-Fashioning in Fin-de-Siecle Europe (2008) indicates

The tendency not to lean too heavily on anyone else’s theory of Jewish self-hatred has no doubt helped a fairly small discussion produce a wide range of interpretive strategies: social psychological (Lewin), psychoanalytic (Gay), psycho-historical (Liebenberg), intellectual historical (Hallie), “topological” (Gilman), and cultural historical (Edelman and Volker).

He refers to Gilman’s (1986) Jewish Self-Hatred that ‘it is only natural, that where some measure of integration is a desideratum, and there is also bigotry in the ‘majority culture’, minority self-loathing will occur’ (Reitter, 2009: 360). He argues Gilman, like W.E. B. Du Bois before him, attempts to explain how ‘German Jews came to ‘accept’ and ‘internalize’ a distorted, decidedly negative image of their own group.’ Du Bois, as Reitter (2009: 360) reports, writes: ‘But the facing of so vast a prejudice could not but bring the inevitable self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering of ideals which ever accompany repression and breed in an atmosphere of contempt and hate’ (cited in Reiter, 2009). He quotes from Endelman, who as he remarks is an eminent historian of European Jewry:

Self-hating Jews were converts, secessionists, and radical assimilationists who, not content with disaffiliation from the community, felt compelled to articulate how far they had travelled from their origins by echoing anti-Semitic views, by proclaiming their distaste for those from whom they wished to dissociate them- selves. What set them apart from other radical assimilationists was that, having cut their ties, they were unable to move on and forget their Jewishness. (cited in Reitter, 2009: 366).

Reitter (2009) wants to retrace the evolution of the term ‘Jewish self-hatred’ as a more polite concept than ‘Jewish antisemitism’ with redemptive possibilities. The question is complex and the hypothesis that Jews who harboured such a negative self-image and possessed such a strong desire to be accepted in a society that was covertly and residually hostile to Jews’ might be true but it risks becoming ‘a rhetorical weapon to critics of assimilation’, as Janik (2013 Janich (2013, p.143) suggests in a review of Rietter. He refers to David Sorkin and Steven Beller, who ‘have provided us with accounts of how vigorous Jewish criticism of Jewish life, Socratic self-criticism, was part and parcel of a self-consciously Jewish ‘enlightenment’ (haskalah) from the time of Moses Mendelssohn.’

Wittgenstein’s Jewish self-loathing is a complex affair. David Stern (2001: 237) asks:

Did Ludwig Wittgenstein consider himself a Jew? Should we? Wittgenstein repeatedly wrote about Jews and Judaism in the 1930s (Wittgenstein 1980/1998, 1997) and the biographical studies of Wittgenstein by Brian McGuinness (1988), Ray Monk (1990), and Szabados (1992, 1995, 1997, 1999) make it clear that this writing about Jewishness was a way in which he thought about the kind of person he was and the nature of his philosophical work.

He answers his own question by reference to Brian McGuinness’ Young Ludwig (1889-1921) – ‘First, Wittgenstein did, on occasion, speak of himself as a Jew’ especially in relation to Weininger’s writings on Jewish character in a series of now famous remarks made in the 1930s recorded in Culture and Value. Second, ‘Wittgenstein did, on occasion, deny his Jewishness, and this was a charged matter for him’ (p. 239), in particular in his confessions to family and friends in 1936 and 1937 when he refers to his misrepresentation of his Jewish ancestry. Stern later comments: ‘Is there a connection between Wittgenstein’s writing on Jews and his philosophy? What did he mean when he spoke of himself as a “Jewish thinker” in 1931?’ (p. 265) and concludes

Wittgenstein’s problematic Jewishness is as much a product of our problematic concerns as his. There is no doubt that Wittgenstein was of Jewish descent; it is equally clear that he was not a practicing Jew. Insofar as he thought of himself as Jewish, he did so in terms of the anti-Semitic prejudices of his time (p. 269).

Wittgenstein’s sexuality also caused him much anguish and led to bouts of homosexual self- loathing. In Austria and the United Kingdom homosexuality was still outlawed and considered not only a crime but also a psychiatric treatable condition. There were many risks associated with homosexuality and even with writing about in as late as the 1970s. William W. Bartley III (1973) published his book on Wittgenstein that included references to Wittgenstein being gay, much to the dismay of the philosophical establishment that tried to ban such discussion and to deny that there was any link at all between his work and his sexuality and the feelings it generated. Barley made a few off-hand remarks about Wittgenstein’s promiscuous homosexuality while he was training to be a teacher in Vienna. The evidence for this claim has never been established (Monk, 2018).

Wittgenstein had relationships with David Pinsent in 1912, with Francis Skinner in the 1930s and Ben Richards in the late 1940s. The first was purely Platonic or unconsummated and it is unclear to what extent the other two relationships involved physical expressions of love. It has been a major problem in Wittgenstein studies to address and analyse his sexuality and homo- sexuality as though somehow Wittgenstein’s sexual feelings tainted the ascetic moral ideal that had been built around him as a philosopher. It is interesting the extent to which perspectives have changed – not only societal values and the embrace of gay and transsexual rights but also the legitimacy of sexual autobiography in relation to questions of philosophy. The fact that Michel Foucault was gay by contrast is considered strongly to influence his outlook and his work, and he is celebrated because of it. It was a very significant part of his work in his genealogical studies of the history of sexuality and coloured his view of women’s sexuality. For Wittgenstein, a generation older, the societal reaction was quite vicious and Wittgenstein agonised over his sexuality, without ever addressing it, even though there was an underground acceptance of homosexuality at Cambridge.

There is little doubt of Wittgenstein’s homosexuality or its importance in understanding the man. The more difficult question is the effects of his homosexuality on his philosophy and on his relationships when he was a teacher. Psychoanalytically, much could be made of this personal secrecy and the need to preserve confessional material from prying eyes that might be very damaging. The question is fundamental yet there is no extant work that risks analysis in relation to Wittgenstein to my knowledge. Sex and language as a particular focus of a wider debate on the issue of gender and language now seems almost commonplace. Wittgenstein may have taken some relief from Freud’s analysis of the bisexual nature of human beings where everyone is attracted to both sexes yet Freud’s determinism in ascribing biological and psycho- logical factors on the basis of deep libidinal sexual drives making it difficult to change would have raised questions for Wittgenstein at the point he was trying to change.

Gay male culture began to flourish in the late nineteenth century in 1920s Vienna (sodomy was still an imprisonable offence) and sexologists like Krafft-Ebing and Freud had begun to codify homosexual identity and to see it as a ‘perversion’. There were still very strong taboos in place when Wittgenstein was a teacher. It was not until the 1970s after the ‘Gay Holocaust’ that gay and lesbian activism saw a resurgence. Had Wittgenstein’s homosexuality been known at this time it would almost certainly would have led to his vilification. This anti-gay environment in general society and in teaching forced Wittgenstein’s sexual identity ruminations underground. Derek Jarman’s (1993) witty depiction of the gay ‘Wittgenstein’ is a path-breaking dramatic analysis of Wittgenstein’s opening up as a gay man.2

Wittgenstein on suicide

‘The Ethics of Suicide Digital Archive’ is an exhaustive work accompanying the book prepared by the philosopher Margaret Pabst Battin from the University of Utah3 that begins:

Is suicide wrong, always wrong, or profoundly morally wrong? Or is it almost always wrong but excusable in a few cases? Or is it sometimes morally permissible? Is it not intrinsically wrong at all, though perhaps often imprudent? Is it sick? Is it a matter of mental illness? Is it a private or a social act? Is it something the family, community, or society should always try to prevent, or could ever expect of a person? Could it sometimes be a “noble duty”? Or is it solely a personal matter, perhaps a matter of right based in individual liberties, or even a fundamental human right? https://ethicsofsuicide.lib.utah.edu/introduction/

The Digital Archive acts as comprehensive sourcebook, providing a collection of primary texts on the ethics of suicide in both the Western and non-Western traditions, with an archive based on Wittgenstein’s Notebooks 1914–16 and Letters. The introduction to these texts is prefaced by a note on Wittgenstein’s feelings about suicide during the years 1912–13 when how spent time with David Hume Pinsent, a friend, collaborator and Plantonic lover of Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein friend and collaborator David Hume Pinsent, with whom he traveled on holidays together, describes Wittgenstein’s frequent thoughts of suicide at numerous places in his own diary. In Pinsent’s entry for June 1, 1912, he notes that Wittgenstein told him that he had suffered from terrific loneliness for the past nine years, that he had thought of suicide then, and that he felt ashamed of never daring to kill himself; according to Pinsent, Wittgenstein thought that he had had “a hint that he was de trop in this world.” In his entry for September 4, 1913, when they were traveling in Norway, Pinsent describes Wittgenstein as “really in an awful neurotic state: this evening he blamed himself violently and expressed the most piteous disgust with himself ... it is obvious he is quite incapable of helping these fits. I only hope that an out of doors life here will make him better: at present it is no exaggeration to say he is as bad–(in that nervous sensibility)–as people like Beethoven were. He even talks of having at times contemplated suicide.” In his entry for September 25, 1913, Pinsent reports that “This evening we got talking together about suicide–not that Ludwig was depressed or anything of the sort–he was quite cheerful all today. But he told me that all his life there had hardly been a day, in which he had not at one time or other thought of suicide as a possibility. He was really surprised when I said I never thought of suicide like that–and that given the chance I would not mind living my life so far–over again! He would not for anything.” (Italics in origin, https://ethicsofsuicide.lib.utah.edu/selections/wittgenstein/).

Pinsent (1891–918) was a descendent of Hume who gained a first class honours at Cambridge University in mathematics. Wittgenstein had only arrived at Cambridge to talk with Russell about whether he should take up philosophy in October 1911. During the Christmas vacation Wittgenstein comes to the end of a deep depression. He meets David Pinsent in Russell’s rooms and they quickly became friends, taking tea together, attending concerts, and making music. Within a month of meeting Wittgenstein proposed to Pinsent that they go on holiday together to Iceland in September 1912. They took a second holiday together at the same time in 1913 and were to meet in August 1914 before WWI intervened. As Preston (2018) has reported Wittgenstein received letters which he described as ‘sensuous’. Their relationship was fated when on May 8 1918 Pinsent is killed in an air accident while flying a de Havilland bi-plane. Preston writes:

In the immediate aftermath of Pinsent’s death, Wittgenstein was depressed to the point of planning to kill himself somewhere in the mountains in Austria. But at a railway station near Salzburg he bumped into his uncle Paul, who found him in a state of anguish, but saved him from the suicide he was planning. Wittgenstein kept in contact with Pinsent’s family at least until mid-1919, and probably beyond that. https://theconversation.com/how-ludwig-wittgensteins-secret-boyfriend-helped-deliver-the-philosophers-seminal-work-96557

Pinsent supported Wittgenstein and admired him. It seems clear that Wittgenstein was in love with Pinsent. He dedicated the Tractatus to him when it was published in 1921. Many of the reports on Wittgenstein’s depressed and suicidal state of mind during this period come from Wittgenstein’s letters and Pinsent’s diary.4

It is during this period that Wittgenstein (1961) comes to a resolution about suicide when he writes in what we know as the Notebooks 1914–1916

If suicide is allowed then everything is allowed. If anything is not allowed then suicide is not allowed. This throws a light on the nature of ethics, for suicide is, so to speak, the elementary sin. And when one investigates it it is like investigating mercury vapours in order to investigate the nature of vapours.

For Wittgenstein suicide is the paradigmatic case for ethics and while he seems to have entertained suicide as an idea from when he was a boy he steadfastly refuses to give into his despair. Suicide is an evasion of life and God’s will demands that we should come to terms with the facts as a moral task despite the sheer enormity of it and the difficulties of confronting one’s own nature. To his friend Paul Englemann (‘Mr E’ who edits the Letters) on May 30, 1920 he expresses how desperate he has become:

I feel like completely emptying myself again; I have had a most miserable time lately. Of course, only as a result of my own baseness and rottenness. I have continually thought of taking my own life, and the idea still haunts me sometimes. I have sunk to the lowest point.

And writing again to Mr E. he confesses that he is sinking more deeply into depression, that he is contemplating suicide but cannot will himself to take his own life:

I am beyond any outside help. – In fact I am in a state of mind that is terrible to me. I have been through it several times before: it is the state of not being able to get over a particular fact.... I know that to kill oneself is always a dirty thing to do. Surely one cannot will one’s own destruction, and anybody who has visualized what is in practice involved in the act of suicide knows that suicide is always a rushing of one’s own defenses. But nothing is worse than to be forced to take oneself by surprise.

One wonders about the state of mind of a man suffering from continual torment and living daily with the threat of suicide and his capacity to teach children under such circumstances. He writes to Keynes in October 18, 1925 just before the so-called Haibauer incident (hitting the boy):

I have resolved to remain a teacher as long as I feel that the difficulties I am experiencing might be doing me some good. When you have a toothache, the pain from the toothache is reduced by putting a hot water bottle to your face. But that works only as long as the heat hurts your face. I will throw away the bottle as soon as I notice that it no longer provides that special pain that does my character good.

Suicide could not be the answer for Wittgenstein. He had decided to learn to live with it as a test of his moral character. Paul Engelmann (1974) in a brief memoir writes:

Wittgenstein experienced the world as filled with ‘vile’ and ‘disgusting’ people, not exempting himself. He told David Pinsent, the close companion of his prewar years in Cambridge, that he felt he had ‘no right to live in an antipathetic world ... where he perpetually finds himself feeling contempt for others, and irritating others by his nervous temperament without some justification for that contempt etc. such as being a really great man and having done really great work.’ He began to think of suicide at the age of 10 or 11; a decade or so later he told Pinsent he ‘felt ashamed of never daring to kill himself,’ and in 1918 we find him ‘on his way to commit suicide somewhere.’ ....Though Wittgenstein eventually died of natural causes, he was clearly a tormented figure. His search for decency and honesty not only led him to give his entire fortune away but often took the form of browbeating others ... .

In The Myth of Sisyphus Albert Camus (1942/1997) declares ‘There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide’ (Il n’y a qu’un probl eme philosophique vraiment s erieux: c’est le suicide), a very similar definitive statement by Wittgenstein some forty years earlier: ‘Suicide is the elementary sin’. According to Schopenhauer, moral freedom – the highest ethical aim – is to be obtained only by a denial of the will to live. ‘When life is so burdensome, death has become for man a sought-after refuge’. Schopenhauer affirmed: ‘They tell us that suicide is the greatest act of cowardice... that suicide is wrong; when it is quite obvious that there is nothing in the world to which every man has a more unassailable title than to his own life and person’. Schopenhauer has a significant influence on Wittgenstein, especially in his the early period. Schroeder (2012, p. 367) notes that Schopenhauer influences his early thinking on ethics and the meaning of life:

His 1916 Notebook (NB 71–91) and the final pages of the Tractatus contain a number of echoes of Schopenhauer. Like him he describes aesthetic contemplation using Spinoza’s expression “sub specie aeterni[tatis]”; he repeats Schopenhauer’s criticism of the categorical imperative: that every imperative calls forth the question “And what if I do not do it?” (TLP 6.422); he also agrees with Schopenhauer (and Kant) that the good action should not be motivated by its consequences (TLP 6.422); like Schopenhauer he thinks that science cannot answer questions of value; like him he places “the solution of the riddle of life” outside space and time (TLP 6.4312), and like him he thinks that “what is higher” cannot ultimately be expressed in words. (TLP 6.432, 6.522)

Schroeder (2012) suggests that of greater philosophical importance are Schopenhauer’s thoughts on idealism and especially ‘world as idea’ (p. 368) and the notion that ‘the subject is ... a presupposition of [the world’s] existence’ (NB 79: 2.8.16) and the attendant idea that the metaphysical subject ‘cannot be encountered in experience’ but ‘must be identified with its experiences’ (p. 369). Wittgenstein came to identify both solipsism and idealism as errors, on the basis of early thinking for the private language argument. It seems the case that Schopenhauer did influence the early Wittgenstein’s thinking on suicide but this thought did not remain with him. Schroeder (2012, p. 380) writes:

As a young man, in times of crisis, trying to formulate his ethics and attitude towards life, he remembered and adopted various thoughts from Schopenhauer, some of which he tacked on to his logical-philosophical treatise; but they have very little to do with his philosophical achievements. His real debt to Schopenhauer lies elsewhere. For one thing, the young Wittgenstein was persuaded by Schopenhauer’s idealism (minus its transcendental side), and that proved extremely fruitful for his own thinking all through his life.

In ‘Wittgenstein, Schopenhauer and the metaphysics of suicide’ Modesto Gomez (2018) suggests,

the problems that Wittgenstein raised and the views that he emphatically endorsed are in keeping with his overarching transcendental conception of the metaphysical I, the fundamental character of ethics (NB, p. 79), the meaning of life, and the I as “the bearer of ethics” (NB, p. 80), as it is extensively advanced in the Notebooks 1914-1916 and tersely expressed in the Tractatus. Far from demanding further development, what Wittgenstein’s views on suicide would require is an appropriate background. Such considerations naturally stemmed from the core of the metaphysical picture that permeates Wittgenstein’s early writings. This picture is, in its essentials, Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of the Will (p. 299).

I think this is correct and there is no doubt that Schopenhauer was decisive in Wittgenstein’s early view of suicide but, at the same time, this ought not to detract from the biographical and autobiographical in explaining Wittgenstein ethics of suicide. Here, it is difficult to deny that Wittgenstein’s own experiences did not have an effect on his existential philosophy.

Notes

Schopenhauer writes that suicide is accounted a crime in England which is “followed by an ignominious burial and the seizure of the man’s property” and most often occasions a verdict of insanity.

http://www.openculture.com/2013/03/iwittgensteini_watch_derek_jarmans_tribute_to_the_philosopher_featuring_tilda_swinton_1993.html

https://ethicsofsuicide.lib.utah.edu/

http://www.wittgensteinchronology.com/6.html

References

Achinger, C. (2013). Allegories of destruction: “Woman” and “the Jew” in Otto Weininger’s sex and character. The Germanic Review, 88(2),121–149. 2013

Camus, A. (1942). The myth of Sisyphus (O’Brien, Justin, Trans.). London: Penguin Group. (First published by Gallimard)

Engelmann, Paul (1974) Letters From Ludwig Wittgenstein. With A Memoir. New York, Horizon.

Gilman, Sander (1986) Jewish Self-Hatred: Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP

Jacquette, D. (2000). Schopenhauer on the ethics of suicide. Continental Philosophy Review, 33(1),43–58.

Janik, Alan (2013) On the Origins of Jewish Self-Hatred by Paul Reitter (review) HYPERLINK "https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/181" Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, HYPERLINK "https://muse.jhu.edu/issue/29179" Volume 32, Number 1, Fall 2013, pp. 142-145.

Jamison, K. R. (2000). Night falls fast: Understanding suicide. New York: Vintage.

Le Rider, J. (1990). ‘Between modernism and postmodernism: The Viennese identity crisis’ (R. Manheim, trans.). In E. Timms & R. Robertson (eds.) Vienna 1900: from Altenberg to Wittgenstein, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Le Rider, J. (1993). Modernity and the crises of identity: Culture and society in Fin-de-Si ecle Vienna (R. Morris, trans.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Le Rider, J. (2013). Otto Weininger: A Misogynist, anti-Semite, and Self-loather as Wagnerite. Wagnerspectrum, 9 (1),2013, 89–93.

McGuinness, B. (1988). Wittgenstein: A life. Young Ludwig (1889–1921). Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Modesto Gomez, A. (2018). Wittgenstein, Schopenhauer and the metaphysics of suicide. Rev. Filos., Aurora, Curitiba, 30(49), 299–321.

Monk, R. (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein: The duty of genius. London: Jonathan Cape.

Monk, R. (2018). Bartley’s Wittgenstein and the coded remarks. In: Flowers, F. A., III (ed. and preface); Ground, Ian (ed. and preface); Portraits of Wittgenstein (pp.129–134). London; Bloomsbury Academic; 2018. (xiii, 489 pp.)

Niekerk, C. (2013). Reading Mahler: German culture and Jewish identity in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna. (Studies in German literature, linguistics and culture) Rochester, NY: Camden House.

Peters, M A. (2017). Les proc es et l’enseignement de Wittgenstein, et la « figure de l’enfant » romantique chez Cavell. A contrario, 25(2), 13-37. https://www.cairn.info/revue-a-contrario-2017-2-page-13.htm.

Preston, John (2018) How Ludwig Wittgenstein’s secret boyfriend helped deliver the philosopher’s seminal work, https://theconversation.com/how-ludwig-wittgensteins-secret-boyfriend-helped-deliver-the-philosophers- seminal-work-96557

Reitter, P. (2009). The Jewish self-hatred octopus. The German Quarterly, 82(3),356–372. 82.3 (Summer)

Schroeder, S. (2012). Schopenhauer’s influence on Wittgenstein, pp.367–384. In Ed. Bart Vandenabeele, A Companion to Schopenhauer, Oxford, Blackwell.

Shapira, E. (2006). Modernism and Jewish identity in early twentieth-century Vienna: Fritz Waerndorfer and his house for an art lover. Studies in the Decorative Arts, 13(2), 52–92. Vol. No. SPRING-SUMMER (2006).

Stern, D. (2001). Was Wittgenstein a Jew? In J. Klagge (Ed.), Wittgenstein: Biography and philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stern, David and Szabados, Bela, (eds.) (2004). Wittgenstein reads Weininger, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 206pp., $24.99 (pbk), ISBN 0521532604

Szabados, B. (1992). Autobiography after Wittgenstein. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 50(1), 1–12.

Szabados, B. (1995). Autobiography and philosophy: Variations on a theme of Wittgenstein. Metaphilosophy, 26(1/2), 63–80.

Szabados, B. (1997). Wittgenstein’s women: The philosophical significance of Wittgenstein’s misogyny. Journal of Philosophical Research, 22, 483–508.

Szabados, B. (1999). Was Wittgenstein an anti-Semite? The significance of AntiSemitism for Wittgenstein’s philosophy. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 29(1), 1–28.

Weininger (1903/2005) Sex and Character. An Investigation of Fundamental Principles Otto Weininger, edited by Daniel Steuer and Laura Marcus, translated by Ladislaus Lob, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Waugh, Alexander (2010) The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War. New York, Anchor.

Wittgenstein, L. (1980). Culture and value, edited by G. H. von Wright in collaboration with H. Nyman , trans. P. Winch, Oxford, Basil Blackwell.

Wittgenstein, L. (1980/1998). Culture and value. First published as Vennischte Bemerkungen, German text only, G. H. von Wright & Heikki Nyman (ed.). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1977: Amended 2nd ed., traps. P. Winch. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1980; rev. 2nd ed., German text only, edited by G. H. von Wright and Heikki Nyman, with revisions by Alois Pichler. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1994, rev. 2nd ed., new traps. P. Winch. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1998. (References will give the pagination for the 1980 and 1998 editions of the book; translations are taken from the 1998 edition.)

Wittgenstein, L. (1997). Denkbewegungen: Tagebiicher 1930–1932 1936–1937 (MS 183) ed. Use Somavilla. Innsbruck, Austria: Haymon Verlag.

#ludwig wittgenstein#philosophy#jews#yiddishkeit#otto weininger#greats#arthur schopenhauer#misogyny#self-hating jews#austria#fin-de-siecle#identity#jewishness#suicide#metaphysics#self-image#david pinsent#shame#vienna#identity crisis#fin-de-siecle vienna#homosexuality#sexuality#jewish culture#secular judaism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphorisms On Madness, Philosophy, & Society (from my book, Gaslit By A Madman)

Aphorisms On Madness, Philosophy, & Society (from my book)

Wittgenstein on Otto Weininger.

Wittgenstein once said about Otto Weininger: “If you were to reverse all of his assertions, they would still be equally fascinating and worthwhile. ” That tends to be how I view all utterances. (If only SJWs thought like this about all utterances!) This is much closer to truth as aletheia, the Greek and Heideggerian notion, rather than strict formal, propositional veracity.

If you believe in truth, you are delusional!

.......Thus, as things became even more extreme, and relativism spread from ‘values’ to truth itself, we increasingly began to see the crazed spectacle of Professors of Psychiatry ‘scientifically’ labelling everyone who simply happens to have different beliefs from themselves as ‘sick’ and ‘delusional’i. e meaning they have a ‘fixed false belief’. while their prestigious, highly rewarded colleagues in the Humanities, Philosophy or Literary Studies department loudly proclaim there is ‘no truth, only interpretations’! No doubt somewhere or other, the two doctrines have been combined and solidified in the very same individuals such that if you still believe in ‘truth’, you are delusional, i. e you have a fixed ‘false’ belief and require urgent ‘treatment’! Pretty deranged, eh?

Truth as the best healer

Real truth saves lives; real truth works better than any pill. Especially for the honest.

On self-identity and freedom of conscience

Nowadays, if a ‘woman’ came into a psychiatrist’s office and professed to be a Champion Bull, raring to butt horns in the otherwise peaceful long-grassed meadows of her youth once more . the good Dr. would quite rightly feel obliged to continue the interview in aggressive snorts and threatening raking at the carpet, like any other modern, non-bigoted professional. But if this erstwhile proud Minator were to opine that there is no such thing as ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘mental illness’, someone’s professional opinion would be gravely offended and someone else’s dosage – that of the poor, once righteous monster -- would be judiciously and roundly quadrupled.

Excessive codes of 'civility' as cause of hateful outbreaks

Excessive codes of 'civility', which rule out certain antagonistic, strongly felt forms of speech, when such cosy 'civility' is not truly felt are one of the leadingyet most over-looked causes of hatred and violence. The reason that throughout society and on all social media websites especially there is enforced civility is because the powers-that-be were afraid of people's differences being worked out in a peaceful manner and them growing united and thus harder to control and dominate.

Psychiatry’s inversion of health and sickness.

In all discernment between healthy and pathological behaviors, the key thing to be aware of is that the nature of the former is to be a deliberate, willful action -- realizing one's 'true will' to quote Aleister Crowley -- whereas that the latter is to be picked up unconsciously or half-consciously from one's environment, sometimes with a dimly conscious but burgeoning awareness that it is vulgar, stupid or slavish. Psychiatry precisely inverts the true nature of this dichotomy, labelling healthy, i. e willful liberation as pathological, and unhealthy, slavish unthinking conformity as healthy: it is the exact opposite. "Its sickness is for its traits and the traits of its parts to be traits by which the soul does not do its actions that come about by means of the body or its parts, or does them in a more diminished manner than it ought or not as was its wont to do them. Al Farabi

Harm, punish, or 'treat'.

If you harm, punish or 'treat' an bad man, he might just re-consider his wicked ways; but if you harm, punish or 'treat' a good one, he is often liable or prone to re-consider his good ways.

The disadvantages of self-control.

The exhortation to self-control is really an exhortation to obedience and submission. (When they said I lacked 'self-control', what they actually meant was I wasn't controlling myself according to their demands. and they proceeded to take actual selfcontrol away from me) If we are really going to free ourselves of the crippling influence of convention and actually arbitrary, oppressive socalled 'authority', we probably ought to rid ourselves of all self-control that is not absolutely necessary.

Real change.

The cave-dwelling masses and everyday non-mental -patients, while all too fatuously and recklessly embracing ideologies of social 'progress', are frightened of a real change in their Being and locked into a pattern of stagnation and decay. The madman, (remember, the etymological meaning of the word 'mad' is to 'change') at least in the normative, ideal sense of that term, (as well as often he or she who is solabelled), has awakened to the need for spiritual becoming, both in himself and others.

Madness and Art.

Madmen and poets are alike: they both give freer reign to their emotional and linguistic expressions than is considered decent. And, both of them too, do it largely for socially admirable, therapeutic reasons. Albeit the 'mad' one is more often misunderstood, since people forget that all life, and the unartistic life most of all, is a good opportunity for art, for therapy.

The unartistic life is the most drab, automatic, unredeemed kind of life, in which salutary disruptions are still possible No one blinks twice if they see an eviscerated heart in an art gallery nowadays. But if they see an eviscerated heart while it is still in someone's chest. That's magic.

Autobiography of values as requisite.

To counter-act the tide of artificial, false pretenses to expert, scientific 'objectivity', and the docile, herd-like conformity that actually entails within social science, within the healing professions, and within society a whole, I propose that a personal account of one's life-story, focusing on how one came to arrive at one's central, integral values, become a standard for all such careers. This would be a move towards bolstering the development of personality and character throughout society, preventing people from hiding entirely behind their professional veneers, and presencing the real-lived experience and actual, rather than false selves, of individuals. I don't propose this merely as a helpful task for the 'professional' on the way to qualifying, but as a central piece that he must present to his or her clients/patients. A kind of C. V., but, as I say, with the focus on HOW HE CAME TO HIS CENTRAL CONVICTIONS ABOUT LIFE

‘Recreational’ drug use is medicinal drug use.

The potential of currently illegal substances such as LSD and DMT, as well as more common and less potent ones such as marajuana, to provide radical new, mad vistas of consciousness, and so heal the mental sickness with which mainstream society is so disastrously afflicted ( see the work of Terence Mckenna), is no less important than their capacity to treat physical illness or relieve physical pain. While all substances can potentially be used ill-advisedly, the depreciation of supposed ‘recreational’ uses ignores the dire and gaping need even so-called ‘normal’ people have for fresh inspiration, hedonic sustenance, and the health benefits that all true enjoyment, relaxation or true insight brings. It merely repeats the fallacious and artifical seperation between these supposedly mutually alien aspects of ourselves, a long with the superstitious, ascetic and crude utilitarian privileging of the mere functionality of ‘health’, over the supposedly wicked nature of happiness in this world --- a sad residue of religious puritanism and centuries of slavery to sadistic dogmas of control --even though it is only Epicurean pleasure that ultimately justifies life itself. This attitude is so pervasive and so perverse that it simply cannot be under-stated.Ravi Das, a neuroscientist at University College London who is researching the effects of ketamine said: “The potential benefits are definitely downplayed in face of these drugs being used recreationally,” he said. “People view their use in a research setting as ‘people are just having a good time’. ”From this vantage point, must one not wager the theory that almost the whole of modern medicine, most obviously in terms of mental illness, but even in its approach to illness as such --- including physical illness- -- as simply a form of prolonged Christian hatred-ofthe-flesh and jaw-dropping sado-masochism on a mass scale ? That is why Prof. David Nutt equated the barriers to research to the Catholic church’s censorship of Galileo’s work in 1616. “We’ve banned research on psychedelic drugs and other drugs like cannabis for 50 years,” he said. “Truly, in terms of the amount of wasted opportunity, it’s way greater than the banning of the telescope. This is a truly appalling level of censorship. ” Ignoring the importance of psycho-active drugs for promoting health is bad enough, but to ignore or denigrate the importance of pleasure to this aim, is like discounting the use of the eyes in driving to work in the morning! --.

Beyond rational self-preservation ((lock him up! He's a danger to himself.

.!)

. Enlightenment thinkers such Thomas Hobbes and John Locke tried to appeal to and foster what is called man's rational selfpreservation, inserting it above all other goals as the centrepiece and pivot of the whole of society. Notice here the two concepts, reason, on the one hand, and self-preservation, on the other, are heavily intertwined, which still remains the case today. Madness, on the other hand, is commonly associated with throwing caution to the wind, tightrope walking over a precipice just for the sheer Hell of it, and embracing a variety of dangers that may very well end in personal extinction. However, when one considers the nature of our own inevitable mortality, is making selfpreservation our highest goal really so rational? In order to face life in all its grim reality, is it not necessary, at some point or other, to eschew 'rational' self-preservation for a bold leap, (if only in the imagination, if not outward practice), towards an affirmation and embrace of this inextricable fatality? Especially if one seeks to give birth to something greater than oneself, like the Christ, and take on the grave sacrifices that sometimes requires. In other words, rather than 'rational self-preservation', isn't the ability for the‘insane self-annihilation’ of loving sacrifice equally, or an even greater sign of maturity - or of true morality? Thus also the Buddha would seem to have it, who equally, in view of the passing away of all earthly things, preached 'Loss of self' rather than the steady incremental Lockean accumulation of an estate that is eventually destined to perish anyway; he who is said, out of compassion, to have given his life up to be voluntarily devoured by a starving tiger. Reminds me of those ‘voluntary patients’ on the ward that I was on!—.

Consequences of the dehumanization of madness on the collective mind.

The villifIcation of madness and the various phenomenon which are labelled as ‘mentally ill’ in our society, such as ‘grandiose delusions’, ‘hallucinations’, ‘paranoia’, etc. , a long with all the other countless represents a form of collective repression that not only has unspeakably dire results for those so labelled, but wreaks utter havoc on the collective unconscious and the collective conscious. Rather than being the shamen, the spiritual leaders of society, such men and women are quietly tortured and cast into ignominy. Thereby, society is not only deprived of its natural guiding elite, but everyone in society is trained to feel a senseless (‘paranoid’) fear and hatred of their own deepest spiritual roots, that prevents them re-connecting with these forbidden aspects of themselves and manifesting their true potential. Take for instance ‘paranoia’. This stigmatization of questioning the benevolent motives and fundamental agendas of one’s government is one of the most cynical and blatant causes of that government getting out of control and the citizenry failing to protect their own rights and freedoms. The same applies to all the other associated phenomenon of madness, which as has been argued, represent a perenial bed-fellow and midwife of intellectual and spiritual awakening. Just as the criminalization of drugs produces an association between drug-use and general criminality that does not exist independently, re-validating society’s negative view of drug-use in its own eyes, so the category of mental illness and the inhumane, disabling treatments with which those who fall subject to it suffer, is not merely a product of but re-inforces and creates society’s negative attitude to those who manifest these various ‘mad’ phenomenon. All the while, the fact that the sacred key to everybody’s own selfrealization is so maligned and spat upon understandably produces a deep, unacknowledged sense of disconcertedness and pessimism in the population as a whole, the root cause of many other of society’s ailments and self-destructive tendencies. In truth, the real mental illness is the senseless conformity which the ‘mental health’ establishment sacralizes. This sanctified madness then, unconsciously aware of its own shortcomings, in order to sustain its own self-conception as reasonable and sane, is driven to ever more fervent quest to identity and persecute those it delusionally deems ‘mad’, for the sake of externalizing and thereby gaining some sense of control over its own deepest insecuries, and having an Other to label & stigmatize in opposition to which it can re-affirm its own false, insecure and groundless sense of Self

The question is.

why do 'sane' family members (& Dr.s & nurses) have such an enormous problem correctly even identifying their 'unwell' relatives extremely normal human needs?

~Max Lewy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Blob (1988)

Today's review on MyOldAddiction.com, The Blob by #ChuckRussell starring #KevinDillon and #ShawneeSmith, "as exploitative remakes go, is actually more than decent"

CHUCK RUSSELL

Bil’s rating (out of 5): BBB.5.

USA, 1988 . TriStar Pictures, Palisades California Inc.. Screenplay by Chuck Russell, Frank Darabont, based on the earlier screenplay by Theodore Simonson, Kay Linaker, story by Irvine H. Millgate. Cinematography by Mark Irwin. Produced by Jack H. Harris, Elliott Kastner. Music by Michael Hoenig. Production Design by Craig Stearns. Cost…

View On WordPress

#Art LaFleur#Beau Billingslea#Bill Moseley#Billy Beck#Candy Clark#Charlene Fox#Charlie Spradling#Chuck Russell#Clayton Landey#Craig Stearns#Daryl Sandy Marsh#David Weininger#Del Close#Don Brunner#Donovan Leitch Jr.#Douglas Emerson#Elliott Kastner#Erika Eleniak#Frank Collison#Frank Darabont#Irvine H. Millgate#Jack H. Harris#Jack Nance#Jack Rader#Jacquelyn Masche#Jamison Newlander#Jeffrey DeMunn#Jennifer Lincoln#Joe Seneca#Joseph A. Porro

0 notes

Text

This is also the place to remember the similarity between the Englishman and the Jew, which has often been emphasized since Richard Wagner first noted it. Among all the Germanic peoples the English are most likely to have a certain affinity to the Semites. This is suggested by their orthodoxy, including their strictly literal interpretation of the Sabbath. The religiousness of the English often involves hypocrisy, and their asceticism a great deal of prudery. Like women, they have never been productive either in music or in religion. There may be irreligious poets—who cannot be very great—but there is no irreligious musician, and there is also a connection between religion and the fact that the English have never produced a significant architect and even less an outstanding philosopher. Berkeley is an Irishman, as are Swift and Sterne, while Erigena, Carlyle and Hamilton, like Burns, are Scots. Shakespeare and Shelley, the two greatest Englishmen, are still far from the pinnacles of humanity and come nowhere near Dante or Aeschylus. If we consider the English “philosophers,” we see it was they who have supplied the reaction against any depth ever since the Middle Ages, from William of Occam and Duns Scotus, through Roger Bacon and the Chancellor of the same surname, Spinoza’s spiritual relative Hobbes and the shallow Locke, to Hartley, Priestley, Bentham, the two Mills, Lewes, Huxley, and Spencer. This list contains all the important names from the history of English philosophy, for Adam Smith and David Hume were Scots. Let us never forget that psychology without the soul has come to us from England. The Englishman has impressed the German as an efficient empiricist and as exponent of Realpolitik in both practical and theoretical terms, but this is all that can be said about his importance for philosophy. There has never yet been a profound thinker who stopped at empiricism, and never an Englishman who transcended it on his own.

—Otto Weininger

1 note

·

View note

Text

Waiting for Y The Last Man - Aaron Weininger - Ep 36

A TV heavy episode with a healthy dose of comic book reading suggestions. Aaron is the kind of fan who knows who the colorist is on a book. Who else was up for the role of Moon Knight? Do Avengers in the MCU get paid? Would Falcon ever cash in on his status? What are Aaron's problems with the CW superhero shows (Brett likes those shows)? Which version of Moon Knight does Brett prefer? Which Hawkeye comic elevates the character? Are Aaron and Brett excited about the new Hawkeye Disney Plus series? What is Nowhere Men about? What is Great Pacific about? When will we get a Y The Last Man TV series? Did the pandemic change what type of media we want to consume? What show made Brett feel stupid? What is a good comic for people who don't like superhero comics? Who controls Spider-Man's movie appearances?

Reading tips: Civil War (original Marvel comics), Extremis, Transmetropolitan, Planetary, Warren Ellis' Moon Knight (or anything by Warren Ellis), Ed Brubaker's Captain America (Winter Soldier et al), Matt Fraction and David Aja's Hawkeye, Nowhere Men (Image), Great Pacific (Image), Umbrella Academy (Dark Horse), Y The Last Man, Kevin Smith's Green Arrow, Saga, Invincible

Watch tips: Falcon and Winter Soldier, Umbrella Academy, Batman The Animated Series, X-Men The Animated Series, Invincible

Recorded 4/16/21 via Cleanfeed

Check out Comics Who Love Comic Books!

0 notes

Photo

"My Favorite String Quartet" by BY DAVID WEININGER via NYT Arts https://ift.tt/2zwno3X

0 notes

Text

Andras Schiff, Brahms and the Question of Tradition

Much attention and mention is given Sir Andras Schiff’s latest remarkable recording of both Brahms’ piano concertos with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Schiff’s choice of instrument is a Blüthner grand piano built in Leipzig around 1859, the year in which the first D minor concerto was premiered. Schiff has changed foot in his views on period instruments and the recording can be seen as an ambitious attempt to scrutinize and fully bring out the true characteristics of Brahms’ works.

Several years ago, Schiff acquired an 1820 fortepiano, which was used to make recordings of two double albums with Schubert’s late piano works. Schiff says: ”Playing the Brahms concertos on a modern piano with modern orchestras, there were always balance problems. And I found, especially in the second B-flat Concerto, that it was just physically and psychologically very hard to play. Somehow, with this Blüthner piano, the physical difficulties disappear. The keys are a tiny bit narrower, so the stretches are not so tiring, and the action is much lighter. So there is not this colossal physical work involved.” In recent interviews, Schiff has criticised the increasing homogeneity of piano performance, with modern Steinways used for repertoire of every era.

In the album’s liner notes Schiff describes his aim of this ECM label New Series project: “To liberate it from the burden of the – often questionable – trademarks of performing tradition.”

The ambition has been to get back to the sound and scale of the performances that Brahms himself would have expected. Among Brahms’ favourite orchestras was Hans von Bülow’s band in Meiningen, which had just 49 players. Schiffs’ previous collaboration with the period instrument ensemble Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in the Schumann piano concerto in London, led to a natural choice of ensemble for this recording.

Listen to a sample from the album:

youtube

David Weininger in New York Times asked Schiff in which passages the use of these instruments allows the music to come across with unusual freshness, and Schiff replied:

“For example, in the first movement of the Second Concerto, the development section can sound, in modern performance, very muddy and not clear, because there is so much counterpoint there. I’m very pleased to hear all those details. But also, take the opening of the third movement, with the cello solo. If it’s played with these instruments, next to the cello solo you hear all the other lower strings: the cellos and violas, and then later the oboe and bassoon. I just hear these layers of sound instead of a general sauce.”

András Schiff on the many facets of Johannes Brahms

youtube

András Schiff on performance tradition and choice of instruments

youtube

”He has gone back to the original manuscripts to check details of his performances, discovering, for instance, that Brahms had attached a metronome marking to the first movement of the D minor concerto that is significantly slower than we usually hear today, but which was omitted from the printed editions. It’s a shock to begin with but Schiff makes it convincing, gradually building the tension through the movement as the sound of his Blüthner – with its much less overpowering lower register than we are used to hearing from modern Steinways – blends beautifully with the soft grained OAE strings, while in the slow movement, it’s the wonderfully mellow woodwind that come into their own.” – The Guardian

“Schiff’s whole point of doing it this way is to strip the music of all of its accumulated performance traditions, and what the Blüthner piano may lack in oomph is more than made up for by the mellow smoothness of its tone and the clarity of textures across the various registers of the instrument…This warmth is pleasingly complemented by the orchestral playing…I was really surprised by how much this recording changed the way I both heard and thought about these concertos.” – Presto Classical

from Piano Street’s Classical Piano News https://www.pianostreet.com/blog/albums/andras-schiff-brahms-and-the-question-of-tradition-11125/

0 notes

Text

Boekerij

Een hele uitgebreide boekenlijst

Oswald Spengler - De ondergang van het avondland

Oswald Spengler - De mens en de techniek

Plato - De republiek

Aristoteles - Metafysica

Aristoteles - Poëtica

Aristoteles - Retorica

Aristoteles - Politica

Aristoteles - Ethica Nicomachea

Thomas van Aquino - Summa Theologica

Augustinus - De stad van God

Niccolò Machiaveli - De vorst

G.W.F. Hegel - Hoofdlijnen van de rechtsfoilosofie

G.W.F. Hegel - De filosofie van de objectieve geest

G.W.F. Hegel - Phenomenology of the Spirit

Arthur Schopenhauer - De vrijheid van de wil

Arthur Schopenhauer - Bespiegelingen over levenswijsheid

Arthur Schopenhauer - De wereld als wil en voorstelling

Friedrich Nietzsche - Voorbij goed en kwaad

Friedrich Nietzsche - Aldus sprak Zarathoestra

Friedrich Nietzsche - Menselijk, al te menselijk

Friedrich Nietzsche - De vrolijke wetenschap

Friedrich Nietzsche - De geboorte van de tragedie

Friedrich Nietzsche - De genealogie van de moraal

Carl Schmitt - The Concept of the Political

Carl Schmitt - Political Theology

Carl Schmitt - Dictatorship

Carl Schmitt - The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy

Martin Heidegger - Being and Time

Martin Heidegger - De vraag naar de techniek

Martin Heidegger - Basic Wriings

Nicolai Hartmann - Moral Values

Nicolai Hartmann - New Ways of Ontology

Nicolai Hartmann - Moral Phenomena

Irving Babbitt - Democracy and Leadership

Irving Babbitt - On Literature, Culture, and Religion

Robert Nisbet - The Quest for Community

Robert Nisbet - Conservatism, Dream and REliaty

Christopher Lasch - The Culture of Narcissism

Christopher Lasch - The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy

Christopher Lasch - The Minimal Self

Friedrich von Hayek - The Road to Serfdom

Friedrich von Hayek - Individualism and Economic Order

Friedrich von Hayek - The Counter-Revolution of Science

Friedrich von Hayek - Law, Legislation and Liberty

Otto F. Bollnow - Mensch Und Raum

José Ortega y Gasset - De opstand der horden

MIchael Oakeshott - Rationalism in Politics & Other Essays

Michael Oakeshott - Voice of Liberal Learning

Michael Oakeshott - On Human Conduct

Michael Oakeshott - Experience and its Modes

Michael Oakeshott - Hobbes on Civil Association

Michael Oakeshott - On History and other Essays

James Burnham - Suicide of the West

James Burnham - The Managerial Revolution

James Burnham - Congress and the American Tradition

James Burnham - De strijd om de wereldmacht

Bertrand de Jouvenel - The Ethics of Redistribution

Bertrand de Jouvenel - Sovereignty

Bertrand de Jouvenel - The Pure Theory of Politics

Christopher Dawson - Religion and the Rise of Western Culture

Christopher Dawson - The Movement of World Revolution

Christopher Dawson - Progress and Religion

Christopher Dawson - The Age of the Gods

Christopher Dawson - The Gods of Revolution

Wilhelm Röpke - A Humane Economy

Hans-Hermann Hoppe - Democracy, The God That Failed

Murray Rothbard - Anatomy of the State

Milton Friedman - Capitalism and Freedom

Milton Friedman - Why Government Is the Problem

Milton Friedman - Free to Choose

Milton Friedman - A Monetary History of the United State

Milton Friedman - Price Theory

Julius Evola - Ride the Tiger

Julius Evola - Men Among the Ruins

Julius Evola - Revolt Against the Modern World

Julius Evola - Meditations on the Peak

Julius Evola - Metaphysics of War

Julius Evola - The Doctrine of the Awakening

Julius Evola - Fascism Viewed from the Right

John Stuart Mill - On Liberty

John Stuart Mill - Principles of Political Economy and Chapters on Socialism

Thomas Hobbes - Leviathan

John Locke - Two Treatises of Government

Adam Smith - Wealth of Nations

Jean-Jacques Rousseau - Discourse on the Origin of Inequality

David Hume - An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding

Karl Marx - Communistisch Manifesto

Karl Marx - Kapitaal

Edmund Burke - Reflections on the Revolution in France

Thomas Sowell - Basic Economics

John Maynard Keynes - The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Ayn Rand - Atlas Shrugged

Thomas Piketty - Capital and Ideology

Thomas Piketty - Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Thomas Piketty - The Economics of Inequality

Naomi Kelin - The Shock Doctrine

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon - What Is Property?

Robert Nozick - Anarchy, State, and Utopia

Robert Nozick - The Examined Life

John Rawls - A Theory of Justice

John Rawls - Political Liberalism

Bertrand Russell - History of Western Philosophy

Theodore Kaczynski - Technological Slavery

Theodore Kaczynski - Industrial Society and Its Future

Theodore Kaczynski - Anti-Tech Revolution

Pentti Linkola - Can Life Prevail?

Jacques Ellul - The Technological Society

Jacques Ellul - Propaganda

Jacques Ellul - Anarchy and Christianity

Jacques Ellul - The Political Illusion

Jacques Ellul - The Presence of the Kingdom

Noam Chomsky - Manufacturing Consent

Guy Debord - Society of the Spectacle

Edward Bernays - Crystallizing Public Opinion

Edward Bernays - Propaganda

Walter Lippmann - Public Opinion

Gustave Le Bon - The Crowd

Werner Sombart - The Jews and Modern Capitalism

Otto Weininger - Sex and Character

Michel Foucault - Discipline and Punish

Michel Foucault - The History of Sexuality

Ludwig Wittgenstein - Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

Ludwig Wittgenstein - Major Works

Camille Paglia - Sexual Personae

Camille Paglia - Sex, Art, and American Culture

Camille Paglia, Free Women, Free Men

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - The Gulag Archipelago

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - 200 Years Together

Leo Tolstoy - War and Peace

Fyodor Dostoyevsky - Crime and Punishment

Fyodor Dostoyevsky - The Idiot

Maurice Samuel - You Gentiles

Benjamin Freedman - Facts are Facts

Richard Tedor - Hitler’s Revolution

Tomislav Sunic - Against Democracy and Equality

E. Michael Jones - Libido Dominandi

1 note

·

View note

Text

David Stern, Was Wittgenstein a Jew?, In Wittgenstein: Biography and Philosophy, ed. James Klagge, 237 (2001)

In my mind's eye, I can already hear posterity talking about me, instead of listening to me, those, who if they knew me, would certainly be a much more ungrateful public.

And I must do this: not hear the other in my imagination, but rather myself. Le., not watch the other, as he watches me - for that is what I do - rather, watch myself. What a trick, and how unending the constant temptation to look to the other, and away from myself.

--- Wittgenstein, Denkbewegungen: Tagebucher 1930-1932/1936-1937, 15 November or 15 December, 1931

1. Was Wittgenstein Jewish?

Did Ludwig Wittgenstein consider himself a Jew? Should we? Wittgenstein repeatedly wrote about Jews and Judaism in the 1930s (Wittgenstein 1980/1998, 1997) and the biographical studies of Wittgenstein by Brian Mc- Guinness (1988), Ray Monk (1990), and B€la Szabados (1992, 1995, 1997, 1999) make it clear that this writing about Jewishness was a way in which he thought about the kind of person he was and the nature of his philosophical work. On the other hand, many philosophers regard Wittgenstein's thoughts about the Jews as relatively unimportant. Many studies of Wittgenstein's philosophy as a whole do not even mention the matter, and those that do usually give it little attention. For instance, Joachim Schulte recognizes that "Jewishness was an important theme for Wittgenstein" (1992, 16-17) but says very little more, except that the available evidence makes precise statements difficult. Rudolf Haller's approach in his paper, "What do Wittgenstein and Weininger have in Common?," is probably more representative of the received wisdom among Wittgenstein experts. In the very first paragraph, he makes it clear that the sole concern of his paper is the question of "deeper philosophical common ground" between Wittgenstein and Weininger, and not "attitudes on feminity or Jewishness" (Haller 1988, 90) . Those who have written about Wittgenstein on the Jews have drawn very different conclusions. He has been lauded as a "rabbinical" thinker (Nieli 1987) and a far-sighted critic of anti-Semitism (Szabados 1999), and criticized as a self-hating anti- Semite (Lurie 1989), as well as condemned for uncritically accepting the worst racist prejudices (Wasserman 1990). Monk (1990) provides a rather more nuanced reading of the evidence . He presents Wittgenstein as briefly attracted to using anti-Semitic expressions in the early 1930s, but only as a way of thinking about his own failings. Most discussions of the topic take it for granted that Wittgenstein was a Jew, but recently McGuinness (1999/ 2001) has contended that even this is a mistake.

In this essay, I argue that much of this debate is confused, because the notion of being a Jew, of Jewishness, is itself ambiguous and problematic. Instead, we would do better to start by asking in what senses Wittgenstein was, or was not, a Jew. Another way of putting this is to say that we should first consider different ways of seeing Wittgenstein as a Jew. Before rushing to judgment, we need to consider what it could mean to say that Wittgenstein was, or was not, a Jew, or an anti-Semite. This is not just a matter of tabulating various possible definitions of these expressions, but of considering the different contexts - cultural, social, personal - in which those terms can be used, and their significance in those contexts. In doing so, we need to give critical attention not only to the various criteria for being a Jew that Wittgenstein would have been acquainted with, and the presuppositions he might have taken for granted about Jews and Judaism, but also the ones that we use in our discussion of Wittgenstein as a Jew, and our motives for doing so. One of the great dangers in writing philosophical biography is the risk of turning the study of a philosopher's life and work into vicarious autobiography, wishful thinking, or worse.

I begin my discussion of the question of Wittgenstein's Jewishness by looking at two passages by Brian McGuinness that offer very different answers. The first, from the first volume of his biography of Wittgenstein, subtitled "Young Ludwig (1889-1921)," takes it for granted that Wittgenstein did think of himself as a Jew, at least during the first half of his life, and gives some indication of how important that fact was to him. The passage begins with a reference to Otto Weininger, who Wittgenstein identified, in a passage written in 1931 (1980/1998, 18-19/16-17), as an important influence. In the same piece of writing, Wittgenstein also discussed the connection between his Jewishness, his character, and his way of doing philosophy. Wittgenstein repeatedly recommended Weininger's pseudoscientific and anti- Semitic Sex and Character (1903) to friends, including G. E. Moore in the early 1930s and G. E. M. Anscombe in the late 1940s. As we shall see, Monk's biography also emphasizes Wittgenstein's indebtedness to Weininger's ideas about talent and genius, and their close connection to his views about Jewishness and femininity.

Weininger had yet two important features in common with the young Ludwig. First he was Jewish. He suffered from the consciousness of that fact . He identified the Jewish with all that was (on his theory) feminine and negative.... The theme of the stamp put on a man's life and thought by his Jewishness often recurs in Ludwig's later notes, though, to be sure, he saw it more as an intellectual than as a moral limitation. Already in childhood he was preoccupied on a more practical level with dissociating himself for social and even moral reasons from all the different strata of Judaism in Austria. We shall see what remorse that cost him and can measure in that way how compelling the need for dissociation was . (McGuinness 1988, 42)

In the passage quoted above, McGuinness puts his finger on two leading themes that must be addressed by anyone interested in the question of whether Wittgenstein was a Jew, or his views about the Jews : the nature of the Weininger connection, and the nature of Wittgenstein's "dissociation" from Judaism. First, Wittgenstein did, on occasion, speak of himself as a Jew, and the understanding of what it means to be a Jew we find in his writings - his conception of Jewishness, so to speak - makes use of ideas of Weininger's. Most of his surviving writing on this topic dates from the early 1930s, and much of it has been published in Culture and Value: these are the "later notes" McGuinness (1988, 42) refers to above in passing, and discusses in some detail in (1999/2001). (I examine this material in §§ 4 f. below.)