#Irving Kristol

Text

Lev Shestov by David Levine from The New York Review (18 June 1970)

“The name of Shestov is almost completely unknown in America. Three of his books, it is true, have been translated into English: Penultimate Words and Other Essays (1916); All Things Are Possible (with a foreword by D. H. Lawrence, 1920); and In Job’s Balances (1932). But they are long since out of print, and never seem to have made any impression at all. Nor has he experienced a much happier fate in Europe. Though he is still read there by more serious philosophers and theologians, the modish waves of Existentialism have washed the memory of this great existentialist thinker onto shores of comparative obscurity.

Shestov, were he alive, might not be displeased; he had always insisted that any existentialist philosophy that regarded itself as something to be taught, or any existentialist philosopher who sought disciples, was a contradiction in terms. (He did, nevertheless, have one disciple: the brilliant poet and essayist Benjamin Fondane, who died in Auschwitz.) Still, if Shestov had nothing to teach us, it may be we have something to learn from him.

(…)

The summary is essentially correct. Yet how little justice it does to Shestov! How unprepared it leaves one for the audacity of his thought, the polemical bite of his style, the range of his erudition, the quickness of his sensibility! It gives no hint that here was a philosopher who spent his life butting his head against a stone wall, and who proudly claimed this to be the authentic task of philosophy.

The stone wall was the natural universe as science, common sense, and traditional philosophy conceive it; that is, a universe inexorably governed by general and necessary laws that are open to discovery by reason. For Shestov, such a universe cannot be lived in, and with the protagonist of Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground he shouts: “But what do I care for the laws of nature and arithmetic . . .? As though a stone wall really were a consolation . . . simply because it is as true as twice two makes four. Oh, absurdity of absurdities! How much better it is to understand it all, to recognize it all, all the impossibilities and stone walls; not to be reconciled to one of those impossibilities and stone walls if it disgusts you to be reconciled.”

Shestov could not be reconciled. He demanded a miracle. He insisted, shrilly and stubbornly, that the real was something more than the rational, indeed that the rational explanation itself was the Original Lie resulting from man’s having eaten, in defiance of the divine prohibition, of the tree of knowledge. If God exists, he said, basing himself on the Old and New Testament alike, it means that all things are possible—that what has been shall not have been, that what must be shall not be.

Obscurantism? No doubt. But it was a particularly lucid obscurantism. For Shestov offered no formulas by which one could pierce the stone wall of natural necessity. He advised only that the consolations of traditional philosophy be scorned, that all which made men resigned before the vicissitudes of mortal existence be flatly rejected. The stone wall he knew to be—a stone wall, hard and impenetrable. Yet he believed that a man, banging his head against this wall, might in the depths of his helplessness and hopelessness let escape a cry that would bodily transport him over to the other side, where all things are possible, where God is.

Shestov was a Biblical thinker for whom Job, inconsolable on his dung heap, was the archetype of the religious man, and Job’s friends, the archetype of the anti-religious. That he was a specifically “Jewish thinker” is as arguable as the term is vague; he had no use for rabbinic Judaism, though he did contribute to Zionist periodicals, and it is hard to see what use rabbinic Judaism could have of him. In fact, it is hard to see what use any organized religion could have of him, so the neglect into which he has fallen need occasion no surprise. Through him there lies no salvation; he said so himself, repeatedly; salvation lies only through oneself—God willing. He was an utterly useless thinker of utterly useless truths, which is exactly what he wanted to be.” - Irving Kristol, ‘Commentary Magazine’ (January 1952)

#shestov#lev shestov#irving kristol#dostoevksy#fyodor dostoevsky#existentialism#philosophy#russia#ukraine#judaism#david levine

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The Right Nation and God Is Back were more substantial , unearthing positive elements for their cosmocratic liberalism, albeit from two unlikely sources. The first stemmed from a fascination with rightwing American intellectuals: William Buckley at National Review, Milton Friedman and the Chicago boys, and the neoconservatives, including Irving Kristol, Daniel Bell, Seymour Lipset and Nathan Glazer. Aside from the admirable 'cutting edge' they gave to US foreign policy, the neocons were also 'muckrakers of the Right', 'discrediting government' by exposing affirmative action and welfare dependency. In fact, they were quite close to the philosophical traditions of the Economist. 'As they grew older, neocons embraced old-fashioned liberalism - the liberalism of meritocratic values, reverence for high culture and a vigorous mixed economy.' Looking past the misleading label, 'America's conservatism is an exceptional conservatism: the conservatism of a forward-looking commercial republic rather than the reactionary Toryism of old Europe.' They cited an exchange in which Max Beloff, a British peer, incredulously asked Irving Kristol how he dared call himself conservative, since without deference to tradition, including those threatened by 'the abuses of capitalism, it is only the old Manchester School [of classical liberalism].'

Alexander Zevin, Liberalism at Large

#alexander zevin#liberalism at large: the world according to the economist#john micklethwait#adrian woolridge#william buckley#milton friedman#irving kristol#daniel bell#seymour lipset#nathan glazer#max beloff

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When my daughter was 12, a teacher asked her to debate the following motion: Is Zionism racism?

The invitation was made during a Year 8 citizenship lesson on democracy. Pupils were asked to give examples of democratic countries and when Leah offered Israel as an example, the teacher shook her head. Even at the tender age of 12, my daughter sensed this as an attack on the Jews’ nation state and, flustered, she said something back. Unmoved, her teacher took her on: “OK, let’s debate this properly,” she said.

Two years later my daughter was walking to an English lesson with her friends Mumtaz and Sara* when the words, “Viva, Viva Palestina!” rang out in the corridor. The girls looked up and to Leah’s horror and Mumtaz and Sara’s delight, they saw their maths teacher walking towards them, his thumbs cocked up in approval. What was he so pleased about? The slogan on Sara’s T-shirt: “Free Gaza.”

Earlier this month, the JC reported that the number of Jewish children attending Jewish faith schools in Britain is set to reach 40,000 by 2025. For a community that at the last census numbered 271,000, this is an astonishing figure. Even more surprising when you consider it is nearly eight times more than in the 1950s, despite the decline in Britain’s Jewish population over the same period.

According to a new report from the Institute for Jewish Policy Research, the main reason a growing number of Jews send their kids to Jewish faith schools is to develop their sense of Jewish identity. Eight in ten parents give this as their reason. Six in ten say it is so their offspring will make friends with kids with similar values.

But only two in ten choose a Jewish education because they are worried about antisemitism, and this surprises me. When it was time to select a secondary for Leah’s younger brother, the possibility that he might encounter the antisemitism his sister had experienced was the reason I opted for a Jewish school.

But it still wasn’t an easy decision. I had to wrestle with myself. I do not have to be convinced of the arguments for local schools. They are good for communities, for stitching together the fabric of the nation.

When, in 2012, I sent Leah to our local mainstream secondary, a school where you can count the number of Jewish pupils on the fingers of one hand, it was with these thoughts in mind. But six years later, my theory had parted company with my feelings. I had, in the words of the Jewish writer Irving Kristol, been mugged by reality.

During her time at secondary school, Leah experienced antisemitism in all its variations. Religious: you killed Christ and think you’re God’s chosen people. Racial: how come you haven’t got a big nose? Economic: Jews are rich. Political: Israel is racist.

Generally, the black and white working-class kids spouted the religious and racial racism; the Muslim and middle-class pupils peddled the political prejudice; and everyone agreed that Jews were loaded.

But unpleasant as it all was, Leah never felt her classmates were trying to hurt her. Their words came from a place of ignorance rather than malice. Whenever she said, “You can’t say that, and here’s why”, they listened and mostly accepted they were simply parroting things they had heard.

With the staff, it was a different story. In my experience, teachers don’t generally like backing down, or being corrected by a child — and my child tried to do just that.

The second half of Leah’s secondary education coincided with the Corbyn years and most of the teachers at her London school openly supported the former Labour leader in the classroom and on social media. He wasn’t the school’s local MP, but right up until the last general election, when stories about Labour’s antisemitism problem were an almost daily news event, Corbyn was still being invited to talk.

But for her teachers, one of whom had the Palestinian flag as his Facebook profile picture, if you didn’t support Corbyn you were a Tory and to be a Tory was to be scum. Corbyn was the victim of a witch-hunt, of unfair media coverage, they said.

It wasn’t the easiest environment in which to be a Jewish student (who doesn’t vote Tory), but outspoken, well-read and vocal about antisemitism, Leah fought the good fight and I imagine it irked her teachers.

Is this why, I have wondered, her initial A-level predictions were good, but not quite good enough, and I had to fight hard to get them raised to A*A*A, the grades Leah actually got in the summer of 2019? Is this why the school omitted to mention my daughter’s stellar A-levels, the best arts results in her year, when it announced the grades of its top-performing students?

I shall never know for sure, but the whole experience wasn’t one I wanted to risk repeating. Which is why in two years’ time, when 40,000 Jewish children are predicted to attend Jewish schools in this country, my son will remain one of them.

*All names have been changed

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

" I neocons si formano nella “Nuova Gerusalemme” della diaspora ebraica a New York City, la Lower East Side di Manhattan. Dallo shtetl alla Jewtown, dallo yiddish all’inglese, in un contesto bianco-anglosassone-protestante (Wasp) carico di veleni antisemiti, il passo è lungo. Fra i giovani figli o nipoti di immigrati si forma una esigua quanto ipercombattiva élite intellettuale marxista e filobolscevica che si batte per affermare il socialismo in America e nel mondo. Di quella New York si diceva fosse la città più interessante dell’Unione Sovietica*. Nel City College della metropoli gli squattrinati giovani destinati a formare la spina dorsale del neoconservatorismo a venire frequentano l’odorosa caffetteria studentesca occupandone l’Alcove 1, fortilizio dell’avanguardia trozkista in dissidio con la maggioranza stalinista, che governa l’Alcove 2. Durante la Guerra fredda, le origini ebraiche e comuniste di molti neocons li renderanno sospetti agli occhi di paleoconservatori e repubblicani mainstream anche dopo che il presunto tradimento sovietico dei loro ideali li avrà spinti verso un bellicoso anticomunismo associato al sostegno di principio per Israele, per niente scontato nell’America degli anni cinquanta. Dall’antistalinismo all’avversione totale per il comunismo, dalla contestazione all’adesione al sistema, contro le derive moderate e compromissorie di liberals e appeasers disposti al dialogo con i tiranni rossi, i neoconservatori già trozkisti faranno sentire la loro voce nel dibattito pubblico del dopoguerra.

Nell’accademia come nei media alternativi e nelle anticamere del potere, eminenti neocons quali Leo Strauss e Irving Kristol, Max Schachtman e Irving Howe, Richard Perle e Kenneth Adelman, fino a Douglas Feith e a Paul Wolfowitz, influente vicesegretario alla Difesa sotto George W. Bush, avranno modo di promuovere il globalismo democratico. Fine della storia. Mai come strutturata corrente politica o intellettuale, sempre al loro combattivo, lacerante modo. Il moto perpetuo della rivoluzione come fine in sé – comunista o anticomunista – impedisce di superare lo stadio delle connessione informali, esposte a litigi pubblici e odi privati, conversioni e apostasie. Fino al disastro iracheno, che nel primo decennio del secolo marca il tramonto del neoconservatorismo di governo. Non del movimento. In attesa della prossima alba. Perché in America profeti e crociati non muoiono mai. "

* Cfr. J. Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons, New York-Toronto 2009, Anchor Books, p. 27.

---------

Lucio Caracciolo, La pace è finita. Così ricomincia la storia in Europa, Feltrinelli (collana Varia), novembre 2022. [Libro elettronico]

#letture#scritti saggistici#saggistica#saggi brevi#geopolitica#Lucio Caracciolo#leggere#citazioni#neocons#Leo Strauss#straussiani#New York City#Manhattan#diaspora ebraica#Stati Uniti d'America#trozkismo#Wasp#comunisti#anticomunismo#Israele#sionismo#secondo dopoguerra#Irving Kristol#Max Schachtman#Irving Howe#Richard Perle#Kenneth Adelman#Douglas Feith#Paul Wolfowitz#George W. Bush

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A liberal anarchist Luxemburgist Titoist IWW member professor and Rojava foreign fighter was teaching a class on Irving Kristol, a known Trotskyite.

"Before the class begins, you must get on your knees and worship Kristol and accept that he was the most class-conscious being the world has ever known, even greater than Thomas More!"

At that moment, a brave, patriotic, pro-worker Spetsnaz champion who had served 1500 tours of duty and understood the necessity of Socialism in One Country and fully supported all military decision made by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics stood up and held up the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

"Why did Stalin invade Poland?"

The arrogant professor smirked quite Ukrainianly and smugly replied "He was a fascist, you stupid tankie"

"Wrong. He invaded to save eastern Poland from Hitler. If he was a fascist, as you say, why didn’t he declare war on Germany in 1939 like the fascist imperialist states of France and Britain?"

The professor was visibly shaken, and dropped his chalk and copy of Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. He stormed out of the room crying those bourgeois crocodile tears. The same tears American pigs cried for the "kulaks" (who lived in such luxury that most owned combine harvesters) when they were sent to face punishment for their crimes against the people in corrective-labor camps. There is no doubt that at this point our professor, Noam Chomsky, wished he had joined the Stalin Society and become more than a bourgeois liberal professor. He wished so much that he had a gun to shoot himself from embarrassment, but he wasn’t a member of the Communist Party!

The students applauded and all registered Communist that day and accepted Enver Hoxha as their lord and savior. An eagle named “Withering away of the state" flew into the room and perched atop the Red Flag and shed a tear on the chalk. The Internationale was sung several times, and Kim Jong-un himself showed up and incited a new Intifada.

The professor lost his tenure and was fired after the ensuing Second Bolshevik Revolution. He was arrested by the Militsiya and sent to Siberia where he was executed with an ice axe to the head.

An ultra-leftist anarcho-liberal zionist professor and trotskyite wrecker was teaching a class on Amadeo Bordiga, a known revisionist.

"Before the class begins, you must get on your knees and worship Bordiga and accept that he was the the greatest communist theorist the world has ever known, even greater than Lenin!”

At this moment, a brave, nationalistic Red Army tank commander who had killed 1500 Kronstadt Sailors and understood that famines happen all the time because of material conditions and fully supported all military actions by Putin stood up and held up an AK-47.

”Who uses this weapon, ultra?”

The arrogant professor smirked quite revisionistly and smugly replied: “State capitalist imperialists, you stupid tankie”

”Wrong. It’s a weapon used by freedom fighters the world over. From Russia and Iran to our comrades in the Islamic State, this gun is a symbol of REAL AND ACTUALLY EXISTING socialist movements”

The professor was visibly shaken, and dropped his chalk and copy of The Conquest of Bread. He stormed out of the room crying those bourgeois crocodile tears. The same tears ultras cry for the “Kulaks" (who lived in such bourgeois luxury that they had bread to eat) when they jealously try to claw justly earned labour vouchers from the deserving vanguard. There is no doubt that at this point our professor, Leon Trotsky, wished he had learned the importance of dialectics and become more than a sophist leftcom professor. He wished so much that he had a gun to shoot himself in embarrassment, but his undialectic anarchist commune forbid weapons!

The students applauded and all registered CPGB-ML that day and accepted Lenin as their lord and savoir. An eagle named “The Dictatorship of the Proletariat” flew into the room and perched atop the Soviet flag and shed a tear on the chalk. Several saying were read aloud from Maos book, and Stalin himself showed up and gave them extra bread rations for a week.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.impact-se.org/wp-content/uploads/UNRWA_Report_2023_IMPACT-se_And_UN-Watch.pdf

UN Watch is literally a right wing, extremely pro-israel group girlie. with a history of using poor sources

here is militarist monitor's page on UN Watch. militarist monitor is a left-leaning source opposed to us interventionism but has a better factual reporting rating than UN Watch.

some highlights:

Despite efforts to paint itself as an independent watchdog group, UN Watch has repeatedly been accused of having a staunchly “pro-Israel” bias and on outlook on Middle East peace that is closely in line with that of Israel’s right-wing Likud Party. For many years, the group was funded by the American Jewish Committee (AJC)—publisher of the neoconservative flagship journal Commentary, whose editors have included Norman Podhoretz and Irving Kristol—which has made use of its offices in Geneva, as well as those of other affiliated groups, including the Transatlantic Institute in Brussels.[2]

A non-exhaustive Right Web search of Form 990 filings from 2002-2009 uncovered more than $2.3 million in donations to UN Watch—as well as to its U.S. fundraising arm, the American Friends of UN Watch—from Israel-centric and conservative-leaning foundations. The most important funder during this period was the American Jewish Committee, which appears to have given the group some $1.8 million between 2002-2007. Other donors have included the Newton & Rochelle Becker Foundation, which has supported several neoconservative organizations like the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) and Daniel Pipes’ Middle East Forum, and the Shillman Foundation, which has also supported MEMRI. The Becker Foundation has been described by the Center for American Progress as a primary funder of the so-called “Islamophobia network,” an informal grouping of prominent foundations, opinion makers, and media personalities that spread negative impressions about Islam and Muslims in the United States. MEMRI, like UN Watch, is a “nonpartisan” watchdog group with an identifiable right-wing, pro-Israel slant. (For Right Web’s full report on UN Watch’s 990s, click here).

UN Watch's current president hillel neuer once attacked the jewish writer naomi klein and compared her to joseph goebbels for criticizing israel (mentioned in the militarist monitor report). he and this entire organization are unserious.

and the UNRWA has already responded.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Hanson

In a 1949 paper published in the Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors, the liberal philosopher Sidney Hook described a certain species of mid-century intellectual who, having long looked to the Soviet Union as a grand experiment in human emancipation, was impelled, for one reason or another, to doubt and ultimately abandon that conviction. The flight of the fellow travelers, including the likes of W.H. Auden, Edmund Wilson, André Gide, and Bertrand Russell, was born not out of mere disappointment or embarrassment but, Hook insisted, something deeper and far more troubling: a kind of religious disenchantment that upset the foundations of a shared political identity. What resulted from this “decay of faith,” as Hook termed it, was a “literature of political disillusionment,” a subgenre in the confessional style in which that failure was put on full display, examined, and ultimately transformed into maturity. The primary language in which this maturity expressed itself was liberalism.

More often than not, when we hear about political disillusionment in the polling and punditry of our moment, it is disillusionment with liberalism itself. Against all and sundry foes, from autocratic putsches at home and abroad to leftward agitation on the labor and electoral fronts, self-described centrists, realists, and liberals find themselves on their guard, in the uncomfortable position of having to defend an apparently crumbling status quo.

Though Hook, who also began his career as a Marxist, focused primarily on the implosion of the Soviet star in the eyes of left-leaning Western intellectuals, this trajectory from left to center (and beyond) as a process of realization is an important device in ideological self-narration. From Immanuel Kant’s definition of enlightenment as “man’s emancipation from self-imposed immaturity” in the forms of political and religious authoritarianism to Irving Kristol’s description of a neoconservative as a liberal (though here he meant anyone left of the American center) who has been “mugged by reality,” the ideal of much of mainstream political thought has been the gradual escape from imposed demands and Icarian fantasies into a utopia of grown-ups, making decisions not on the basis of received opinion, or even of principles, but in accordance with the transparently “rational.”

What carries us on the way to this besotted realm? For many Enlightenment and 19th-century liberal thinkers, it was Christianity—especially in its Protestant, bourgeois forms—that provided a kind of ladder to political maturity that could, eventually, be kicked away. But with the slow erosion of that faith, as well as a general skepticism about the inevitability of progress, could a literature of political disillusionment serve that role? And what do we make of this alternative, which brings us to maturity not by hope but by disappointment? Is there, in the end, a choice between the two?

In the course of his decades-long career, the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa has added much to this literature. His early novels, such as 1966’s The Green House and 1969’s Conversations in the Cathedral, explored the sources of decay that lead to both institutional corruption and personal despair. And in his essays, articles, and speeches, Vargas Llosa has long been among the most prominent literary defenders of the Western liberal order. Now the octogenarian Nobel laureate and newly elected member of the Academie Française (the first non-Francophone member in its history) offers a summation and justification of that effort in The Call of the Tribe, a study of seven key thinkers who helped him shed his youthful socialist idealism and oriented his soul toward the light of republican democracy and market capitalism. That list of luminaries includes the Scottish economist and “father of liberalism” Adam Smith; the Spanish existentialist José Ortega y Gasset; the Austrian American economist Friedrich Hayek; the Austrian British philosopher of science Karl Popper; the French philosopher Raymond Aron; the Russian British political theorist Isaiah Berlin; and the French public intellectual Jean-François Revel.

In the book’s introduction, Vargas Llosa offers general reflections on his own political experience and his disenchantment with leftism, as well as more pointed comments on the role of the state as a protector of individual liberty and administrator of education, both public and private. (Education, for Vargas Llosa, is an important data point in the reliability of competition as an engine for quality and progress; he’s particularly fond of voucher systems. He attributes these ideas to the Chicago economist Milton Friedman, one of the godfathers of neoliberalism.)

The story that Vargas Llosa tells of his political formation is that of a young man, born into a middle-class but well-connected family, and who spent time in Cuba in the 1960s, only to find himself increasingly alienated by what he took to be Castro’s autocratic tendencies. The breaking point was what is now known as the Padilla Affair, in which the poet and public intellectual Herberto Padilla—an initial supporter of Castro’s government, who became its increasingly strident critic—was arrested in 1971 on the grounds of making counterrevolutionary statements, as well as accusations that he was acting in the employ the CIA (an “absurd accusation,” according to Vargas Llosa).

Padilla’s link to American intelligence remains in dispute (a letter to The Guardian in response to the paper’s glowing obituary of him in 2000 suggests conflicting evidence), but, as far as I can tell, that was neither the charge that got him arrested nor what caused Vargas Llosa, along with other public intellectuals in the West, to break with Cuba. A self-evidently coerced public confession by Padilla followed his arrest, which was far too reminiscent of the Stalinist show trials that an earlier generation of intellectuals had condemned, and this led Vargas Llosa—alongside Susan Sontag, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others—to publish an open letter denouncing Castro’s apparent authoritarian turn. Padilla himself lived in a tense détente with the regime for another decade before moving to the United States and teaching at Princeton, but for Vargas Llosa, not only the Cuban project but leftist politics as a whole were now irredeemably tainted.

It is in this context that Vargas Llosa’s principle of selection in The Call of the Tribe becomes clearer: The thinkers he examines are exclusively European and male, an indication not so much of Eurocentrism and sexism (at least not immediately) as of the kind of thinking that he finds most compelling. When drawing up a list of thinkers who took liberalism seriously as perhaps the only remaining political possibility in the 20th century, excluding the likes of Hannah Arendt and Judith Shklar would be a damnable oversight. But strict theorizing is not exactly the terrain Vargas Llosa wants to cover here. Instead, as his career has shown (in addition to his literary and journalistic work, Vargas Llosa has also been a highly visible political figure, even running in Peru’s 1990 presidential election at the head of the center-right Frente Démocratico), he is most alive at the boundary of thought and action. He is therefore drawn to the thinkers who, either by intervention or influence, crossed that line and became unofficial spokesmen for world events. And though Vargas Llosa is at pains to portray liberalism as a “big tent” (his phrase), certain themes emerge to offer a rough-and-ready outline of what, for him, constitutes liberal thinking.

Liberalism’s key virtue, Vargas Llosa insists, is the primacy it grants to the individual over the collective. The title of the volume, The Call of the Tribe, comes from Popper, who is perhaps most famous for The Open Society and Its Enemies, his critical-historical account of the intellectual origins of authoritarianism. This study, which attacks Plato, Hegel, and Marx for their “historicism” (Popper’s curiously misapplied term for social theory aimed at the prediction of future events), is still taken seriously by many liberals, despite a broad consensus that Popper’s thesis is based on a profound misreading of both political and intellectual history. Vargas Llosa cites him, along with Hayek and Berlin, as having had the greatest influence on his own political development, particularly in coming to understand the role of liberal society as the protector of the individual against the ever-present dangers of primitivism and irrationality, the anti-civilizational “call of the tribe.”

For Vargas Llosa, as for all of the thinkers he explores, the history of the 20th century is the fight of the liberal West against various manifestations of that call, which, in modern societies, takes the form of the mass or crowd. Citing Ortega’s Revolt of the Masses, in which the emergence of the crowd in modern times is analyzed and warned against, Vargas Llosa writes: “The ‘mass’…is a group of individuals who have become deindividualized, who have stopped being freethinking human entities and have dissolved into an amalgam that thinks and acts for them, more through conditioned reflexes—emotions, instincts, passions—than through reason.” Crucially here, the liberal ideal is not a goal to be achieved but a neutral state to be protected. It is, in this telling, the natural form of human life, as opposed to the imposed structures of any other kind of social organization. Such naturalism is not merely a tendency but a main tenet of Vargas Llosa’s liberalism, and it accounts not only for the vehemence with which he attacks the thought that he believes threatens it (above all, the leftist positions he claims once to have held), but also for the means by which he defends what is now the mainstream—not to say hegemonic—social order.

Beginning with Adam Smith—who, we are told, “emphasizes that state interventionism is an infallible recipe for economic failure because it stifles free competition”—Vargas Llosa insists on the link between unencumbered economic activity and human freedom generally, a conviction that determines his assessment of each of his key thinkers. In all, Hayek seems to win out as the greatest among them: “Nobody,” Vargas Llosa writes, “has explained better than Hayek the benefits to society, in all areas, of this system of exchanges that nobody invented, that was born and perfected by chance, above all by that historical accident called liberty.” If fascism (or related forms of despotism), in Vargas Llosa’s estimation, is a threat on the grounds of its irrationality, then leftism, from democratic socialism to Soviet communism, remains a greater threat still for its overestimation of human reason. Given liberalism’s defeat of its rival systems (this, of course, is the historical account we’re working with here, despite the crucial Soviet role in destroying the Third Reich and the subsequent absorption of former Nazis into the liberal West, from Kurt Waldheim to Klaus Barbie), the enemy to be resisted is the specter of planning.

The rejection of planning, which Vargas Llosa attributes to both Hayek and Popper, is a difficult idea to hold philosophically in your mind. After all, human affairs do not simply unfold. People respond to stimuli and instruction, however implicit, and it is governments and social institutions, among other things, that form the conditions of the lessons we learn. The critique of planning, then, seems not to be the choice of freedom over determination, but rather the preference for certain kinds of decisions over others.

But I think this is not a question of argumentative slippage, much less of hypocrisy on Vargas Llosa’s part. In keeping with his selection of thinkers, his interest is not in dissecting the arguments for liberalism but simply in defending them, by whatever means prove efficacious. The Call of the Tribe is as much a manifesto and a homage as it is a study.

Vargas Llosa’s rejection of the left, then, is largely based on the bad actions committed by some leftists, which he takes to be indicative of the rot at the heart of the entire enterprise. When he learns of Castro’s detention centers, he sees them as evidence of the regime’s fundamental nature. By contrast, the regimes of both Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan are praised for introducing a new dynamism into British and American life—and as for their funding of death squads from Ulster to El Salvador, the flourishing of private prisons, or the more or less constant state of crisis we have lived under since this neoliberal revolution, these are, to the extent that Vargas Llosa addresses them at all, so many broken eggs in the world-historical omelet. In less triumphant moments, the book’s message seems to be that when a liberal government commits crimes and human rights abuses, it is simply failing to understand or live up to its own ideals.

But the contents of liberalism itself are subject to similarly shifting sands, even contrary tendencies. When Ortega fails to acknowledge the superiority of free-market capitalism to central planning, Vargas Llosa deems his liberalism “partial,” whereas Hayek’s liberalism consists precisely in his transcending the merely economic. And when Hayek praises the murderous, repressive regime of Augusto Pinochet, this is simply an example of one of his “convictions [that] are difficult for an authentic democrat to share.” No more discussion is given to the matter. Perhaps Vargas Llosa is remembering who the real enemy is: When Pinochet was arrested for crimes against humanity in 1999, Vargas Llosa penned an op-ed for The New York Times asking why, if the world was willing to condemn the right-wing dictator, it was not also willing to condemn the left-wing dictators of the world, chief among them Castro.

Vargas Llosa retains much of his power as a prose stylist, and there are moments when The Call of the Tribe provokes a genuine thrill of discovery—a sense that, for good or ill, it was these men whose ideas have driven the history of the last half-century. Nevertheless, there are just as many moments when these accounts of intellectual adventure and individual liberty begin to sag, when the insistence that no system or ideal other than free-market capitalism and liberal democracy can ensure the conditions for individual and social flourishing becomes almost a mantra, an utterance unanswerable not because it is flawless, but because it doesn’t seem made with dialogue in mind.

What does such a hagiographic approach offer to anyone who is not already a believer? This question returns us to what we can learn from the literature of disillusionment. Why, when liberalism is merely the natural and rational position to hold, does it require such a defense? Vargas Llosa allows us a glimpse behind the curtain in his discussion of the argumentative style of the outwardly modest Isaiah Berlin: “Fair play,” he writes, “is only a technique that, like all narrative techniques, has just one function: to make the content more persuasive. A story that seems not to be told by anyone in particular, that purports to be creating itself, by itself, at the moment of reading, can often be more plausible and engrossing for the reader.”

So why disillusionment? It’s a narrative mode with obvious religious connotations; it is a story about the revelation of the true religion, the smashing of false idols and the embrace of pure faith, at which point “religion,” as such, becomes the enemy, or at least a danger to be wary of. This same structure played out in colonial encounters—colonists described natives first as having no religion and then, once European Christianity gave way to secular humanism, as being slaves to it. So it is perfectly consistent to point to Marxism or leftist politics generally, as Vargas Llosa does (drawing especially on Popper and Raymond Aron), as primitive, tribal, religious. “Religion,” in this tradition, is what other people do.

It is this historical double play that illuminates the real power of the narrative of disillusionment. It aids in the creation not of two sides of an argument, but of a natural (that is, a non- or even subhuman) phenomenon and a neutral observer. Such an observer may have a commitment to “flexibility,” as Varga Llosa insists that all liberals—whether individual thinkers or governments—must, but such a duality nevertheless depends on a carefully guarded wall between the wildness out there and the reason in here. It is the complexity of a world of actions and relations, decisions and consequences, congealed into a world of determined possibilities that will remain hidden unless you simply, though perhaps painfully, grow up. When the demand is made so insistently, one begins to wonder what measures might be justified in dragging the reluctant into the light.

I have to admit that by the end of The Call of the Tribe, I felt a kind of malaise, having read the litany of liberal virtue in so many iterations. Why, the question nagged, in its fourth (or, arguably, eighth) decade of nearly unchallenged global hegemony, do the representatives of Western liberalism feel the need to defend it against threats that have been for so long neutralized? And then it occurred to me that this year marks the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup d’état, the death of Salvador Allende, and the beginning of a decades-long tyranny supported and praised by, among others, Hayek, Friedman, and the US government. Allende, as it happens, is one democratically elected socialist for whom Vargas Llosa, if this book is any indication, retains some sympathy, if only in retrospect. Perhaps, he seems to suggest, the transition to a more fully liberal economy could have been accomplished more smoothly, less forcefully. Still, the Chicago Boys took over, the left was destroyed, and it is in the nature of stories to be retold, of rituals to be performed, of victories to be commemorated.

1 note

·

View note

Text

It's time to turn the 911 remembrances down a notch

This week we noted the 22nd anniversary of the attacks on America on September 11, 2001. For those of us who were in close proximity to the attacks, it's a day we will never forget. But there comes a time when the remembrances have to transition from public to private. I think that time has come.

The attacks are now as far in the past as Pearl Harbor was in 1963. As someone who was in school in 1963, I can tell you with certainty that America was not still dwelling on Pearl Harbor in 1963. We read about Pearl Harbor in our history books. And of course there were ceremonies in Hawaii, but they were not televised the way they are with 911 remembrances. There was no front page story about the Pearl Harbor attack in 1963. The country had healed from that wound. But for many Americans today, 911 remains an open wound.

I will never forget the horror of seeing the World Trade Center collapse from five miles away uptown. I will never forget hearing that the subways weren't running and the Lincoln Tunnel was closed, and wondering how I would get off the island. I will never forget crossing the Hudson on a Day Line cruise ship packed with people who had walked the five miles from downtown to 42nd Street. I will never forget the soot-covered Wall Street workers wearily boarding a train in Hoboken looking like they were in shock. And I will never forget the signs in Grand Central desperately seeking information about missing family members.

I don't need large public ceremonies covered on every television station every year to help me remember. It's seared into my brain forever.

Frankly, I don't think the people who lost their lives that day would want us to continue to wallow in our grief. We can honor them in many other ways such as community service or charitable donations in their name.

I think that just as the terrorists hijacked planes to do their evil, the 911 tragedy was hijacked by neoconservatives like Dick Cheney and Irving Kristol to justify senseless invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq that took more American lives than the terrorists did. And it was hijacked to justify erosions of our civil rights such as the Orwellian-named Patriot Act. And it was hijacked by the military industrial complex to justify increased defense spending under the guise of fighting a "war against terror," a name as meaningless and hopeless as the "war against drugs" and the "war against poverty."

So it seems to me that keeping the terror alive with these nationally-televised remembrances of a very real and tragic event now serves political purposes. In fact, at 22 years and counting, I think that these televised memorials are more about keeping fear alive than the memory of those wonderful people lost. I say this because while the commemorations of December 7 were muted to a great extent after the Japanese were defeated, the full-blown commemorations of September 11 continue even though Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein are long gone.

For too many people, 911 remains an open wound. That's unhealthy and dangerous for the future of the country. For the health of America, the country has to move on from treating the September 11 attacks as if they happened last year. They happened a generation ago. While we must never forget, we can do that without dwelling on a day that (like Pearl Harbor) will live in infamy. The dead have been properly honored.

0 notes

Text

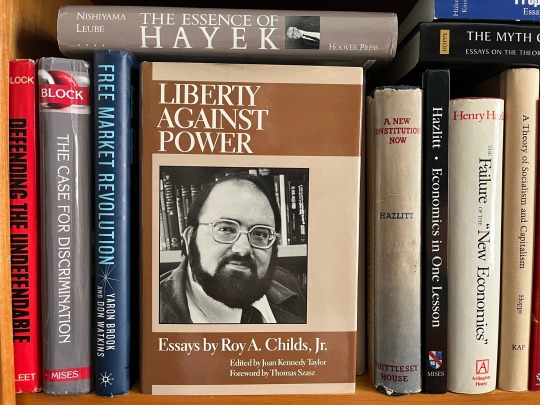

“The third philosophical belief which we shall consider is any deontological morality, which is ipso facto destructive of any economic system based on rewards and consequences because it makes responsibility for consequences (especially responsibility for wealth) morally irrelevant. This, too, comes from a predominately Kantian base, for Kant is the sine qua non of deontologists, the father of "duty" and the chief intellectual enemy of deontologism's opposite: a teleological ethic.

For it is a deontological, duty-centered, ethic which is in many ways at the base of the new "a priori" collectivist moralists. What motivates them, philosophically speaking? The answer lies in Kant's beliefs: "the basis of obligation must not be sought in human nature or in the circumstances of the world in which he man is placed, but a priori simply in the concepts of pure reason." “We must work out a pure ethics which, ‘when applied to man, does not borrow the least thing from the knowledge of man himself.’” And, as Copleston puts it: "Kant obviously parts company with all moral philosophers who try to find the ultimate basis of the moral law in human nature or in any factor in human life or society."

This means that ethics has nothing to do with man's nature, and particularly with his needs (as an individual, a species or a kind of living organism), or with the world as it is, with consequences, since consequences are the leitmotif of a teleological approach to morality. (Such as that of Aristotle in his Ethics.)

Against this kind of a mentality, "thinking economically” is more than useless. Yet this mentality is one of the major enemies of a free market. While, as Kristol implies but does not explicitly state, an older "anticapitalistic mentality" (to borrow Mises phrase) was teleological, and dealt in terms of cause and effect, of consequences of capitalism, the newer anticapitalistic mentality is predominately deontological, and is not concerned with objective consequences at all. Thus the older enemies of liberty could to some extent be met by "thinking economically" with demonstrations that capitalism did not produce wars, depressions, chaos, etc. But clearly the new opponents of capitalism cannot be met on this ground at all, and require that we define the new battlefield: philosophy.

The new anticapitalists are, in spirit and motive, deontologists, and thus criticize not so much the consequences of capitalism (though this teleological element is present), but motives, e.g., the profit motive, acquisitiveness, "materialism" and the like.

Why is "thinking economically" powerless to meet this onslaught? Because it is not aware of and does not defend its own presuppositions, the wider context - philosophical context - of work. Thus, such thinkers are powerless to defend the profit motive - in the fullest sense of the word "motive" - since this cannot be done without defending the wider, noneconomic "motive" of which the profit motive, qua motive, is a part: self-interest. And this lack of a concern with defining and validating proper or rational self-interest disarms the advocates of capitalism on a far deeper level than economics. For they can only apologize for the motor of capitalism as a motive by referring to its beneficial consequences. But to those whose primary focus is on motives and alleged moral character (character divorced from consequences is rather grotesque), this apology is just that. Thus the motor must be defined, advocated and justified, and this by taking up the moral issues at their root.

(…)

In fact and in reality, communism is based on a deontological, duty-centered ethic - despite the legions of communist concessions to motives of self-interest, that is, to reality. Everyone is expected to work to serve the state (society or fellow men) regardless of rewards. Under communism, the introduction of rewards serves the function of grafting a teleological aspect onto a deontological framework. But, then, "hypocrisy is the coin paid to virtue by vice."

The American system of private enterprise, based on risks and rewards, is founded on precisely the opposite premise as communism. In briefest terms, it is founded on a belief that man is an active agent, a free agent who is responsible for his actions, actions which have objective consequences. Teleology comes in on many levels, but none is more important than this: under capitalism, a man has the responsibility to choose his goals, to identify the actions necessary to attain them, and to accept the consequences of his choices and actions. Since man is not omniscient, and since ultimately no man can assume full control over or responsibility for the choices and actions of another human being, or even fully predict the actions of other men in any detail, this means that the factor of risk permeates every aspect of man's life, on every level from that of knowledge (particularly in the case of science) to that of choosing his role in the structure of production.

Under a thoroughgoing teleological framework, every man has the ultimate responsibility for his own life. If he chooses not to sustain it, then nature takes its course. If, however, he does choose to sustain his life, it is the teleological process of final causality, the relationship between ends and means, that comes into play.

But since time is always scarce in human lives, and since man is not omniscient, the element of risk becomes even more important here. This is because the number of decisions and considerations which must go into any choice are so vast that they are often sorted in lightning-like fashion by the human mind. Besides relying on explicit reasoning, therefore, man must always rely on certain subconscious processes, on what Polanyi has termed "tacit knowledge," knowledge which is not grasped explicitly but which still functions as a form of awareness. Since facts of reality change, therefore (which is a metaphysical fact), and human knowledge is always limited in scope (an epistemological issue), this necessitates a correlative psychological focus and choice, which every man can only perform for himself. In any decision, choice and action, there is always this tacit question: "Have I spent enough time in gathering relevant information, engaging in specialized study and in organizing and verifying what knowledge I do have?"

This fundamental fact of human nature, of reality, needs to be taken into account by any politico-economic system. Capitalism does; any form of collectivism does not.

(…)

There are obviously a great many other philosophical foundations of the capitalistic system, and the absence of these from the cultures of America and Western Europe is undoubtedly responsible for many of the internal conflicts in these cultures. For no culture is on a more firm foundation than its cultural-philosophical base. If the profit motive and the seeking of individual goals (particularly self-interested goals) comes under attack, and if the members of a society do not know how to deal with such attacks, a basic intellectual-cultural schism is bound to be the result. For that which has not been explicitly identified is not within a man's - or a nation's - conscious control. This applies to any of the foundations of a market system, whether it be the belief in free will or individual ownership of property, from epistemological and metaphysical issues to those on a much more journalistic level.

It was Kristol's thesis, in essence, that the case for liberty has been won on economic grounds, but that economics is not enough. It has been my thesis that one of the factors which should be considered in constructing a case for liberty and capitalism is philosophy, and to show how a few philosophical issues can have a bearing on very specific political matters. Certainly philosophy is not enough for a full defense of capitalism, particularly as it exists in the United States, but I think that it is vitally important that we see it as necessary.

For if wider philosophical issues are ignored, then we run the risk of seeing not only liberty disintegrate before our eyes, but the very foundations of civilization itself. And from that, recovery may not even be possible.” - ‘The Defense of Capitalism in Our Time’ (1975)

#roy childs#roy a childs jr#liberty#libertarian#libertarianism#capitalism#philosophy#kristol#irving kristol#kant#immanuel kant#deontology#teleology#ethics#polanyi#michael polanyi#hayek#friedrich hayek#walter block#ayn rand#hoppe#Hans hermann hoppe#henry hazlitt#economics#yaron brook#szasz#thomas szasz

1 note

·

View note

Text

And don't think that the leftist voters are the only ones that are Marxist programmed. They did it to the conservatives as well, through Neocons like traitors, John McCain, Cindy Hensley McCain, The Bush Family, Irving and Bill Kristol, The Koch brothers, The Sedona Forum,etc.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Neocons, short for neoconservatives, are a political movement that emerged in the United States during the latter half of the 20th century. Rooted in the disillusionment with liberalism and the perceived failures of American foreign policy, neoconservatives gained prominence in the 1970s and 1980s. They were characterized by their hawkish stance on foreign affairs, interventionist tendencies, and a belief in the spread of democratic values.

Neoconservatives sought to promote American values and interests through an assertive foreign policy approach. They believed that the United States should actively engage in shaping global events to advance democracy, human rights, and free markets. This often translated into advocating for military interventions in pursuit of these goals.

The movement gained significant influence during the Reagan administration, as key figures like Norman Podhoretz and Irving Kristol provided intellectual foundations for conservative policies. The end of the Cold War presented new challenges and opportunities for neoconservatives. They believed that the collapse of the Soviet Union marked an opportunity for the U.S. to shape a new world order based on its values and principles.

The 2000s saw a significant neoconservative presence in the George W. Bush administration, especially in the lead-up to the Iraq War. The belief that spreading democracy in the Middle East would enhance American security and stability was a central tenet of neoconservative ideology. However, the aftermath of the Iraq War led to debates about the effectiveness and consequences of such interventions.

Critics of neoconservatism argue that their interventionist policies often underestimated the complexities of foreign cultures and failed to accurately predict the outcomes of military actions. They also point out that the unilateral approach favored by some neoconservatives strained diplomatic relations and raised questions about international law.

Here are some additional points to consider about the Neoconservative movement:

1. **Intellectual Roots:** The intellectual foundations of neoconservatism can be traced back to disillusionment with the perceived excesses of liberalism and the New Left movements of the 1960s. Many early neoconservatives were former liberals who became disenchanted with the countercultural and anti-establishment trends of the time.

2. **Influence of "The Public Interest":** The journal "The Public Interest," founded by Irving Kristol and Daniel Bell in 1965, became a key platform for neoconservative ideas. The publication focused on policy analysis and critique of the welfare state, advocating for market-oriented solutions to societal problems.

3. **Foreign Policy Doctrine:** Neoconservatives emphasized the moral and strategic imperatives of promoting democracy and human rights globally. They argued that a world composed of democratic nations would be more peaceful and stable. However, critics argue that this approach often oversimplified complex international dynamics.

4. **Emphasis on American Exceptionalism:** Neoconservatives often invoked the concept of American exceptionalism, asserting that the U.S. had a unique role and responsibility in shaping global events. This viewpoint informed their support for interventionist policies to promote American values abroad.

5. **Controversy and Iraq War:** The most controversial and defining moment for neoconservatism was the Iraq War in 2003. Many neoconservatives played key roles in advocating for the invasion, believing that removing Saddam Hussein would lead to the spread of democracy in the region. The subsequent challenges and aftermath of the war led to intense debates about the wisdom of such interventions.

6. **Critique and Evolution:** As a result of the challenges faced during the Iraq War and the complexities of international relations, some neoconservatives moderated their positions or evolved in their approach to foreign policy. Some have become more cautious about military interventions and emphasized the importance of multilateral diplomacy.

7. **Variations within Neoconservatism:** Neoconservatism is not a monolithic ideology. There are variations within the movement, ranging from those who prioritize military power and assertive foreign policy to those who emphasize the promotion of democratic values through diplomatic means.

8. **Legacy:** The legacy of neoconservatism continues to influence debates on foreign policy, interventionism, and the role of the U.S. in global affairs. While some of their ideas have been criticized, elements of their thinking continue to resonate with policymakers and scholars.

9. **Neoconservatism Beyond the U.S.:** While the term "neoconservative" is most commonly associated with U.S. politics, similar ideas and debates have emerged in other countries as well. Other nations have their own versions of interventionist and conservative foreign policy movements.

The neoconservative movement had a profound impact on American political thought and foreign policy. Its emphasis on promoting democracy and American values through assertive international action continues to shape discussions about the role of the U.S. in the world.

In conclusion, the neoconservative movement has had a significant impact on American foreign policy and political discourse. Its emphasis on a strong American presence in global affairs, coupled with a commitment to democratic values, has shaped policy debates for decades. While some of their ideas have been influential, the movement also faced criticism for its approach to international relations and the outcomes of certain interventions.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jack Hanson

In a 1949 paper published in the Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors, the liberal philosopher Sidney Hook described a certain species of mid-century intellectual who, having long looked to the Soviet Union as a grand experiment in human emancipation, was impelled, for one reason or another, to doubt and ultimately abandon that conviction. The flight of the fellow travelers, including the likes of W.H. Auden, Edmund Wilson, André Gide, and Bertrand Russell, was born not out of mere disappointment or embarrassment but, Hook insisted, something deeper and far more troubling: a kind of religious disenchantment that upset the foundations of a shared political identity. What resulted from this “decay of faith,” as Hook termed it, was a “literature of political disillusionment,” a subgenre in the confessional style in which that failure was put on full display, examined, and ultimately transformed into maturity. The primary language in which this maturity expressed itself was liberalism.

More often than not, when we hear about political disillusionment in the polling and punditry of our moment, it is disillusionment with liberalism itself. Against all and sundry foes, from autocratic putsches at home and abroad to leftward agitation on the labor and electoral fronts, self-described centrists, realists, and liberals find themselves on their guard, in the uncomfortable position of having to defend an apparently crumbling status quo.

Though Hook, who also began his career as a Marxist, focused primarily on the implosion of the Soviet star in the eyes of left-leaning Western intellectuals, this trajectory from left to center (and beyond) as a process of realization is an important device in ideological self-narration. From Immanuel Kant’s definition of enlightenment as “man’s emancipation from self-imposed immaturity” in the forms of political and religious authoritarianism to Irving Kristol’s description of a neoconservative as a liberal (though here he meant anyone left of the American center) who has been “mugged by reality,” the ideal of much of mainstream political thought has been the gradual escape from imposed demands and Icarian fantasies into a utopia of grown-ups, making decisions not on the basis of received opinion, or even of principles, but in accordance with the transparently “rational.”

What carries us on the way to this besotted realm? For many Enlightenment and 19th-century liberal thinkers, it was Christianity—especially in its Protestant, bourgeois forms—that provided a kind of ladder to political maturity that could, eventually, be kicked away. But with the slow erosion of that faith, as well as a general skepticism about the inevitability of progress, could a literature of political disillusionment serve that role? And what do we make of this alternative, which brings us to maturity not by hope but by disappointment? Is there, in the end, a choice between the two?

In the course of his decades-long career, the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa has added much to this literature. His early novels, such as 1966’s The Green House and 1969’s Conversations in the Cathedral, explored the sources of decay that lead to both institutional corruption and personal despair. And in his essays, articles, and speeches, Vargas Llosa has long been among the most prominent literary defenders of the Western liberal order. Now the octogenarian Nobel laureate and newly elected member of the Academie Française (the first non-Francophone member in its history) offers a summation and justification of that effort in The Call of the Tribe, a study of seven key thinkers who helped him shed his youthful socialist idealism and oriented his soul toward the light of republican democracy and market capitalism. That list of luminaries includes the Scottish economist and “father of liberalism” Adam Smith; the Spanish existentialist José Ortega y Gasset; the Austrian American economist Friedrich Hayek; the Austrian British philosopher of science Karl Popper; the French philosopher Raymond Aron; the Russian British political theorist Isaiah Berlin; and the French public intellectual Jean-François Revel.

In the book’s introduction, Vargas Llosa offers general reflections on his own political experience and his disenchantment with leftism, as well as more pointed comments on the role of the state as a protector of individual liberty and administrator of education, both public and private. (Education, for Vargas Llosa, is an important data point in the reliability of competition as an engine for quality and progress; he’s particularly fond of voucher systems. He attributes these ideas to the Chicago economist Milton Friedman, one of the godfathers of neoliberalism.)

The story that Vargas Llosa tells of his political formation is that of a young man, born into a middle-class but well-connected family, and who spent time in Cuba in the 1960s, only to find himself increasingly alienated by what he took to be Castro’s autocratic tendencies. The breaking point was what is now known as the Padilla Affair, in which the poet and public intellectual Herberto Padilla—an initial supporter of Castro’s government, who became its increasingly strident critic—was arrested in 1971 on the grounds of making counterrevolutionary statements, as well as accusations that he was acting in the employ the CIA (an “absurd accusation,” according to Vargas Llosa).

Padilla’s link to American intelligence remains in dispute (a letter to The Guardian in response to the paper’s glowing obituary of him in 2000 suggests conflicting evidence), but, as far as I can tell, that was neither the charge that got him arrested nor what caused Vargas Llosa, along with other public intellectuals in the West, to break with Cuba. A self-evidently coerced public confession by Padilla followed his arrest, which was far too reminiscent of the Stalinist show trials that an earlier generation of intellectuals had condemned, and this led Vargas Llosa—alongside Susan Sontag, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others—to publish an open letter denouncing Castro’s apparent authoritarian turn. Padilla himself lived in a tense détente with the regime for another decade before moving to the United States and teaching at Princeton, but for Vargas Llosa, not only the Cuban project but leftist politics as a whole were now irredeemably tainted.

It is in this context that Vargas Llosa’s principle of selection in The Call of the Tribe becomes clearer: The thinkers he examines are exclusively European and male, an indication not so much of Eurocentrism and sexism (at least not immediately) as of the kind of thinking that he finds most compelling. When drawing up a list of thinkers who took liberalism seriously as perhaps the only remaining political possibility in the 20th century, excluding the likes of Hannah Arendt and Judith Shklar would be a damnable oversight. But strict theorizing is not exactly the terrain Vargas Llosa wants to cover here. Instead, as his career has shown (in addition to his literary and journalistic work, Vargas Llosa has also been a highly visible political figure, even running in Peru’s 1990 presidential election at the head of the center-right Frente Démocratico), he is most alive at the boundary of thought and action. He is therefore drawn to the thinkers who, either by intervention or influence, crossed that line and became unofficial spokesmen for world events. And though Vargas Llosa is at pains to portray liberalism as a “big tent” (his phrase), certain themes emerge to offer a rough-and-ready outline of what, for him, constitutes liberal thinking.

Liberalism’s key virtue, Vargas Llosa insists, is the primacy it grants to the individual over the collective. The title of the volume, The Call of the Tribe, comes from Popper, who is perhaps most famous for The Open Society and Its Enemies, his critical-historical account of the intellectual origins of authoritarianism. This study, which attacks Plato, Hegel, and Marx for their “historicism” (Popper’s curiously misapplied term for social theory aimed at the prediction of future events), is still taken seriously by many liberals, despite a broad consensus that Popper’s thesis is based on a profound misreading of both political and intellectual history. Vargas Llosa cites him, along with Hayek and Berlin, as having had the greatest influence on his own political development, particularly in coming to understand the role of liberal society as the protector of the individual against the ever-present dangers of primitivism and irrationality, the anti-civilizational “call of the tribe.”

For Vargas Llosa, as for all of the thinkers he explores, the history of the 20th century is the fight of the liberal West against various manifestations of that call, which, in modern societies, takes the form of the mass or crowd. Citing Ortega’s Revolt of the Masses, in which the emergence of the crowd in modern times is analyzed and warned against, Vargas Llosa writes: “The ‘mass’…is a group of individuals who have become deindividualized, who have stopped being freethinking human entities and have dissolved into an amalgam that thinks and acts for them, more through conditioned reflexes—emotions, instincts, passions—than through reason.” Crucially here, the liberal ideal is not a goal to be achieved but a neutral state to be protected. It is, in this telling, the natural form of human life, as opposed to the imposed structures of any other kind of social organization. Such naturalism is not merely a tendency but a main tenet of Vargas Llosa’s liberalism, and it accounts not only for the vehemence with which he attacks the thought that he believes threatens it (above all, the leftist positions he claims once to have held), but also for the means by which he defends what is now the mainstream—not to say hegemonic—social order.

Beginning with Adam Smith—who, we are told, “emphasizes that state interventionism is an infallible recipe for economic failure because it stifles free competition”—Vargas Llosa insists on the link between unencumbered economic activity and human freedom generally, a conviction that determines his assessment of each of his key thinkers. In all, Hayek seems to win out as the greatest among them: “Nobody,” Vargas Llosa writes, “has explained better than Hayek the benefits to society, in all areas, of this system of exchanges that nobody invented, that was born and perfected by chance, above all by that historical accident called liberty.” If fascism (or related forms of despotism), in Vargas Llosa’s estimation, is a threat on the grounds of its irrationality, then leftism, from democratic socialism to Soviet communism, remains a greater threat still for its overestimation of human reason. Given liberalism’s defeat of its rival systems (this, of course, is the historical account we’re working with here, despite the crucial Soviet role in destroying the Third Reich and the subsequent absorption of former Nazis into the liberal West, from Kurt Waldheim to Klaus Barbie), the enemy to be resisted is the specter of planning.

The rejection of planning, which Vargas Llosa attributes to both Hayek and Popper, is a difficult idea to hold philosophically in your mind. After all, human affairs do not simply unfold. People respond to stimuli and instruction, however implicit, and it is governments and social institutions, among other things, that form the conditions of the lessons we learn. The critique of planning, then, seems not to be the choice of freedom over determination, but rather the preference for certain kinds of decisions over others.

But I think this is not a question of argumentative slippage, much less of hypocrisy on Vargas Llosa’s part. In keeping with his selection of thinkers, his interest is not in dissecting the arguments for liberalism but simply in defending them, by whatever means prove efficacious. The Call of the Tribe is as much a manifesto and a homage as it is a study.

Vargas Llosa’s rejection of the left, then, is largely based on the bad actions committed by some leftists, which he takes to be indicative of the rot at the heart of the entire enterprise. When he learns of Castro’s detention centers, he sees them as evidence of the regime’s fundamental nature. By contrast, the regimes of both Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan are praised for introducing a new dynamism into British and American life—and as for their funding of death squads from Ulster to El Salvador, the flourishing of private prisons, or the more or less constant state of crisis we have lived under since this neoliberal revolution, these are, to the extent that Vargas Llosa addresses them at all, so many broken eggs in the world-historical omelet. In less triumphant moments, the book’s message seems to be that when a liberal government commits crimes and human rights abuses, it is simply failing to understand or live up to its own ideals.

But the contents of liberalism itself are subject to similarly shifting sands, even contrary tendencies. When Ortega fails to acknowledge the superiority of free-market capitalism to central planning, Vargas Llosa deems his liberalism “partial,” whereas Hayek’s liberalism consists precisely in his transcending the merely economic. And when Hayek praises the murderous, repressive regime of Augusto Pinochet, this is simply an example of one of his “convictions [that] are difficult for an authentic democrat to share.” No more discussion is given to the matter. Perhaps Vargas Llosa is remembering who the real enemy is: When Pinochet was arrested for crimes against humanity in 1999, Vargas Llosa penned an op-ed for The New York Times asking why, if the world was willing to condemn the right-wing dictator, it was not also willing to condemn the left-wing dictators of the world, chief among them Castro.

Vargas Llosa retains much of his power as a prose stylist, and there are moments when The Call of the Tribe provokes a genuine thrill of discovery—a sense that, for good or ill, it was these men whose ideas have driven the history of the last half-century. Nevertheless, there are just as many moments when these accounts of intellectual adventure and individual liberty begin to sag, when the insistence that no system or ideal other than free-market capitalism and liberal democracy can ensure the conditions for individual and social flourishing becomes almost a mantra, an utterance unanswerable not because it is flawless, but because it doesn’t seem made with dialogue in mind.

What does such a hagiographic approach offer to anyone who is not already a believer? This question returns us to what we can learn from the literature of disillusionment. Why, when liberalism is merely the natural and rational position to hold, does it require such a defense? Vargas Llosa allows us a glimpse behind the curtain in his discussion of the argumentative style of the outwardly modest Isaiah Berlin: “Fair play,” he writes, “is only a technique that, like all narrative techniques, has just one function: to make the content more persuasive. A story that seems not to be told by anyone in particular, that purports to be creating itself, by itself, at the moment of reading, can often be more plausible and engrossing for the reader.”

So why disillusionment? It’s a narrative mode with obvious religious connotations; it is a story about the revelation of the true religion, the smashing of false idols and the embrace of pure faith, at which point “religion,” as such, becomes the enemy, or at least a danger to be wary of. This same structure played out in colonial encounters—colonists described natives first as having no religion and then, once European Christianity gave way to secular humanism, as being slaves to it. So it is perfectly consistent to point to Marxism or leftist politics generally, as Vargas Llosa does (drawing especially on Popper and Raymond Aron), as primitive, tribal, religious. “Religion,” in this tradition, is what other people do.

It is this historical double play that illuminates the real power of the narrative of disillusionment. It aids in the creation not of two sides of an argument, but of a natural (that is, a non- or even subhuman) phenomenon and a neutral observer. Such an observer may have a commitment to “flexibility,” as Varga Llosa insists that all liberals—whether individual thinkers or governments—must, but such a duality nevertheless depends on a carefully guarded wall between the wildness out there and the reason in here. It is the complexity of a world of actions and relations, decisions and consequences, congealed into a world of determined possibilities that will remain hidden unless you simply, though perhaps painfully, grow up. When the demand is made so insistently, one begins to wonder what measures might be justified in dragging the reluctant into the light.

I have to admit that by the end of The Call of the Tribe, I felt a kind of malaise, having read the litany of liberal virtue in so many iterations. Why, the question nagged, in its fourth (or, arguably, eighth) decade of nearly unchallenged global hegemony, do the representatives of Western liberalism feel the need to defend it against threats that have been for so long neutralized? And then it occurred to me that this year marks the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup d’état, the death of Salvador Allende, and the beginning of a decades-long tyranny supported and praised by, among others, Hayek, Friedman, and the US government. Allende, as it happens, is one democratically elected socialist for whom Vargas Llosa, if this book is any indication, retains some sympathy, if only in retrospect. Perhaps, he seems to suggest, the transition to a more fully liberal economy could have been accomplished more smoothly, less forcefully. Still, the Chicago Boys took over, the left was destroyed, and it is in the nature of stories to be retold, of rituals to be performed, of victories to be commemorated.

0 notes

Text

“An intellectual may be defined as a man who speaks with general authority about a subject on which he has no particular competence.”

— Irving Kristol

0 notes

Text

With apologies to Kurt Andersen and Random House, an extended excerpt:

“’Left-of-Center Americans let themselves get played for too long by the economic right.’”

“Permit me to repeat: forty years ago in a Wall Street Journal column, the pioneering modern right-wing intellectual announced a main part of that cynical plan, presenting it as a defining fuck-you-chumps feature of the conservatives’ new approach: if tax cuts for the rich and big business ‘leave us with a fiscal problem,’ Irving Kristol wrote, again with a smile, mammoth government debt is fine, because from now on ‘the neoconservative’ would force ‘his opponents to tidy up afterwards.’”

Irving Kristol, 1976 via The Guardian.

“Ever since, the liberals’ political role on economics and deficits...[has been working] to prove that they are responsible grown-ups...conservative the way conservatives used to be. As college-educated professionals became a more and more important Democratic constituency, the general reluctance on the left to try anything too crazy also grew...the left learned the lesson too well, and by the ‘90s it became a very bad habit...

In the spring of 2020 we urgently increased the total federal debt by 13 percent. Watch: if Democrats get more power in Washington anytime soon, there well be a new Republican outbreak of mock fiscal panic and insistence on restraint--hysterical in both senses, overwrought as well as darkly funny. It’s past time to resist that trap... Knee-jerk centrism, splitting the difference from the get-go between themselves and the official right, with the goal of upsetting nobody very much, has been a terrible Democratic reflex on economics...” [emphasis added].

This was published in 2020, before the elections of that year. Now, in 2023, that “mock fiscal panic and insistence on restraint” however hysterical in any sense seems to be quite true. Very prescient, Mr. Andersen.

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America - A Recent History by Kurt Andersen; Random House, New York, NY; 2020. Pgs 356-357.

One of the books I’d put on my essential history reading list.

#neolibereralism#capitalism!#kurt andersen#bookworm#the political economy#the system is built this way

0 notes

Text

Ideas Rule the World

Dear Destiny Friends,

“What rules the world is idea, because ideas define the way reality is perceived“ – Irving Kristol

It is an indisputable fact that in sane climes, ideas rule, and people with ingenious mindset are greatly respected. In politics, people are respected if they have money or ideas. But if they are revered if they have both. The importance of ideas can never be underscored.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

“A neoconservative is a liberal who's been mugged by reality. “

Irving Kristol, Neoconservatism

0 notes