#Karin Bergman

Photo

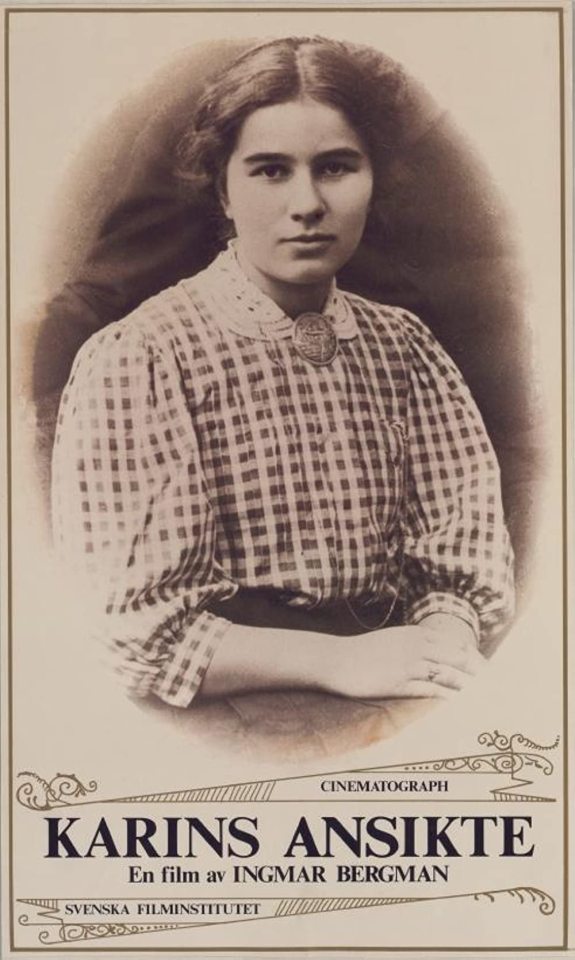

Karin’s Face (Karins ansikte) (1984) Ingmar Bergman

January 9th 2023

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Karins ansikte" (1983) - Ingmar Bergman

("Karin's face")

Films I've watched in 2022 (115/210)

Ingmar Bergman's journey through the family albums in a study of his mother Karin's face through the years.

Beautiful, intimate and very personal short film.

Full film:

youtube

#films watched in 2022#Karins ansikte#Ingmar Bergman#Karin Bergman#short film#motionpicturelover's picture compilations

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

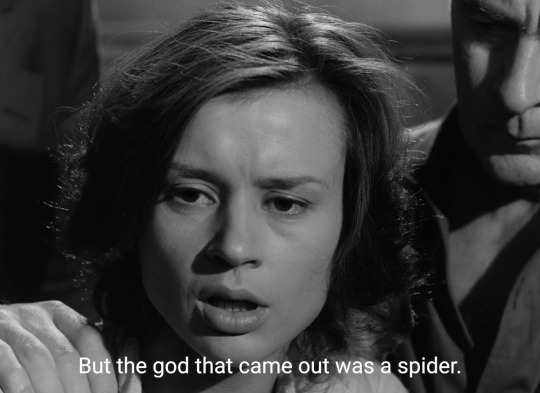

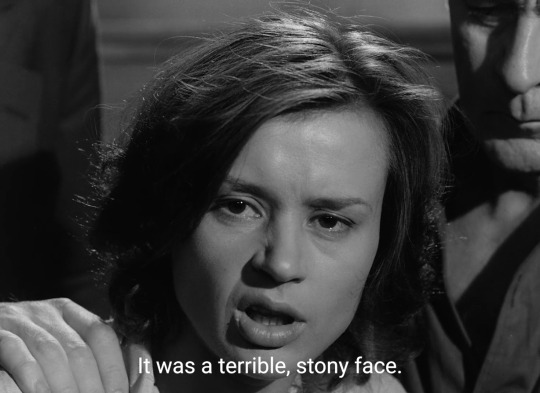

The god that came out was a spider.

#through a glass darkly#såsom i en spegel#ingmar bergman#harriet andersson#sweedish#karin#scenephile#movie quotes#film quotes#movie scenes#film scene#movie scene

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm afraid, I'm afraid! I'm afraid!

Ingrid Bergman as Karin

STROMBOLI: TERRA DI DIO (1950) dir. Roberto Rossellini

#stromboli#stromboli (terra di dio)#worldcinemaedit#classicfilmsource#classicfilmblr#cinemaspast#filmgifs#moviegifs#uservintage#filmedit#cinematv#movieedit#ingrid bergman#roberto rossellini#italian cinema#italian movie#nico.gif#movies#1950s#1950#literally scene of all time TBHHHHH

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Favorite female performances [19/?]

“Can you conceive how anyone can live with so much hate as has been my burden? There's no relief, no charity, no help! There is nothing. Do you understand? Nothing can escape me for I see all!”

INGRID THULIN as Karin in

— CRIES AND WHISPERS (1977)

dir. Ingmar Bergman

#ingrid thulin#cries and whispers#viskningar och rop#ingmar bergman#permormances list#cinema#1970s#fav films#quotes#my gifs

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ingrid Thulin as Karin the self harming older sister in Cries and Whispers (1972) dir. Ingmar Bergman

#this scene is so important yet so poignant regarding her character#cries and whispers#worldcinemaedit#classicfilmsource#oldhollywoodedit#filmgifs#userfilm#userstream#fyeahmovies#my gifs#gif#*

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Brigitta Petterson in The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman, 1960)

Cast: Max von Sydow, Brigitta Valberg, Gunnel Lindblom, Brigitta Petterson, Axel Düberg, Tor Isedal, Allan Edwall, Ove Porath, Axel Slangus, Gudrun Brost, Oscar Ljung. Screenplay: Ulla Isaksson. Cinematography: Sven Nykvist. Production design: P.A. Lundgren. Film editing: Oscar Rosander. Music: Erik Nordgren.

The Virgin Spring was probably the first Bergman film I ever saw, and it made a powerful impression that stuck with me. I think that's one reason why I have mixed feelings about it today. I remembered it as a simple tale based on a 13th-century Swedish ballad, in which a young girl on her way to church is raped and murdered, but from the ground where the crime took place, a spring of fresh water erupts miraculously. But watching it today I see a more complex story, full of moral ambiguities. The girl, Karin (Birgitta Pettersson), is not such a paragon as I remembered: She is spoiled and prideful, trying to sleep late and avoid the task of taking the candles to the church. She may not even be as innocent as she is thought to be: The servant, Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), who accompanies her says the reason she wants to sleep late is that she was out the previous night flirting with a boy. Karin's mother, Märeta (Birgitta Valberg), is on the one hand a religious fanatic given to self-torture, and on the other an indulgent parent unwilling to discipline her daughter. Karin's father, Töre (Max von Sydow), is divided between the Christian faith he has adopted and a furious desire to wreak revenge on the rapist-murderers. After he has killed the two men and the boy who accompanied them, he expresses remorse but also blames God for his daughter's fate. He vows to build a church on the site, and the spring gushes forth, but as a miracle it seems like a somewhat anticlimactic response to the horror that has gone before. (It's not like the site, where running water is copious, even needs another spring.) Bergman for once is working from a screenplay he didn't write: It's by Ulla Isaksson, which may be why the film is poised so ambiguously between Christian affirmation and Bergman's usual bleak alienation. It is, however, one of Bergman's most beautifully accomplished films, joining him with the cinematographer Sven Nykvist, with whom he had worked only once before (seven years earlier on Sawdust and Tinsel), and with whom he would form one of the great working partnerships in film history. In its evocation of medieval narrative and meticulous re-creation of a milieu (the production designer is P.A. Lundgren), it's superb. But as a film from one of the great modern directors it seems oddly anachronistic and insincere.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here we see a picture of Swedish mezzo-soprano Kerstin Thorborg (1896-1970) as Magdalene in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg by R. Wagner. Salzburg 1936.

Kerstin Thorborg was a court singer. She celebrated her greatest triumphs in Wagner’s contralto roles at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and prior to that in Buenos Aires, at the German Opera in Prague and in pre-Nazi Germany and Austria.

Kerstin Thorborg was born in 1896 in the village of Siknäs in Venjan, in a musical home. Her brother Olof often sang during his training as a physician as did their father Viktor Thorborg, who had sung first bass in the male choir Orphei Drängar in Uppsala before becoming a newspaperman and editorial secretary at Södra Dalarnas Tidning. Their mother Hildur, née Boman, and brother Klas were even more important to Kerstin Thorborg since they encouraged and supported her economically.

After passing her school certificate, Kerstin Thorborg took lessons for the voice pedagogue Ina Wickström in 1914–1916 in Växjö. After that followed studies with the voice pedagogue and voice physician Gillis Bratt, who was her teacher in 1917–1919, after which one of his assistants, Karin von Rosen, took charge of Kerstin Thorborg’s voice training until 1923. After a successful audition at the Kungliga Teatern Opera School (now Operahögskolan in Stockholm) she started her professional training.

After small roles in Wagner’s Die Walküre and Verdi’s Rigoletto, she made the first of her three obligatory debuts in 1923: as Lola in Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, a role that disappeared out of her repertoire after three performances. On the other hand, she enjoyed some of her greatest successes in the future in Berlin, Vienna and New York with her other two debut roles: Ortrud in Wagner’s Lohengrin in 1924 and Amneris in Verdi’s Aida in 1925.

In the autumn of 1925, Kerstin Thorborg got to know Gustaf Bergman who became very important to her. He had been the director at the Stora teatern in Gothenburg, from which he was fetched by the Stockholm Opera director John Forsell after having produced Die Fledermaus by Johann Strauss the younger. He was to be responsible for the Stockholm production of the same work. After that, he was appointed as stage manager at the Kungliga Teatern. It was at the Stockholm Opera that Kerstin Thorborg — probably with the help of Gustaf Bergman — learned practically her entire future repertoire with five exceptions: Eudossia in Ottorino Respighi’s La Fiamma, the dryad in Ariadne auf Naxos, Clytemnestra in Electra, Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier and Herodias in Salome, the four last-named operas by Richard Strauss.

In 1925, Kerstin Thorborg signed her first contract with the Kungliga Teatern, the first of several that were often renegotiated so that her annual income rose from 3,000 kronor to 16,000 kronor. When her final Stockholm contract expired in 1931, she had appeared in 341 performances of altogether 38 productions, among which were lesser roles in Swedish operas.

Kerstin Thorborg signed her first foreign contract with the Nürnberg Opera in 1930. After that she appeared mainly in the German-speaking opera houses: Deutsches Landestheater in Prague, Stadt-Theater in Nürnberg, Städtische Oper in Berlin, Wiener Staatsoper and the Salzburg Festival as well as the German seasons at Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. At Covent Garden in London she sang only Wagner and Richard Strauss every spring in 1936–1939.

In 1928, Kerstin Thorborg and Gustaf Bergman were married in the church in her home town Hedemora in the central Swedish province of Dalarna. With that she was to share her sixteen-year-older husband’s economic problems with paying maintenance after two divorces. However, from 1931 onwards, she earned so well that she was able to end her contract with the Städtische Oper in Berlin in 1934 on account of her dissatisfaction with the Nazis and as a protest against Hitler. She did the same thing with the Vienna Opera a few days before the Anschluss.

In 1935, the Canadian tenor Edward Johnson took over as the director of the Metropolitan Opera. With his Norwegian roots, he favoured Scandinavian singers like Kirsten Flagstad and Lauritz Melchior and soon also Kerstin Thorborg, who made her debut in New York in 1936. During her first season in 1936/1937, she sang five Wagner roles at 15 performances. At her 24 performances in the season of 1937/1938, both her new Richard Strauss roles, Clytemnestra in Elektra and Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier attracted general admiration but disappeared immediately out of the repertoire. The season of 1938/1939 included 52 performances and only one new role – that of Orpheus in Gluck’s opera Orpheus and Eurydice.

During her visit to Europe in 1939, she appeared in four concerts with Arturo Toscanini: in Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis on two May evenings in London and in Verdi’s Requiem with Jussi Björling at her side on two August evenings in Lucerne. Despite the war, her duty demanded that she sang Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde with Martin Öhman on four October evenings in Holland.

In October 1939, Kerstin Thorborg and Gustaf Bergman travelled by ship from Oslo to the USA and did not return to Dalarna until the end of May 1946. In between lay 67 months in America and 254 performances with mainly Wagner on the programmes.

During the couple’s home journey after the war in 1946, Kerstin Thorborg’s fiftieth birthday was celebrated onboard in company with two other returning Swedish Metropolitan stars: the tenors Jussi Björling and Torsten Ralf with their respective wives. In October the same year, Kerstin Thorborg and her husband returned to New York. Four performances at the Opera in Chicago were her first appearances, but nothing was fixed with the Metropolitan, despite the fact that Kerstin Thorborg had for several years been accustomed to participating in more than 30 performances per year there.

When M/S Gripsholm arrived in Gothenburg early in January 1947 with the couple who were already returning home, the journalists wondered why they were back so soon. The couple blamed Kerstin Thorborg’s Dutch tour and the fact that Gustaf Bergman’s memoirs must be completed. They did not yet know that the director of the Metropolitan, Edward Johnson, had for a long time dreamt of engaging Hjördis Schymberg who was already on her way there. For the couple, 1947 was an involuntary sabbatical year. Not until January 1948 did Kerstin Thorborg sing again at the Metropolitan, but only in five Wagner roles during a period of ten weeks. The following year, her contribution was reduced to fourteen appearances in four Wagner roles but as encouragement also six Richard Strauss evenings. Edward Johnson left the Metropolitan in 1950 and Kerstin Thorborg had to be satisfied with six appearances at the beginning of that year. With four evenings singing Verdi and Saint-Saëns in Stockholm in the autumn of the same year, Kerstin Thorborg ended her career.

After her husband’s death in 1952, Kerstin Thorborg isolated herself and socialised mainly with her nine cats. In 1963, Falu-Kuriren’s music journalist Seth Karlsson was given the assignment of interviewing her, which led to an exhibition at the Dalarna Museum, that also received two of her stage costumes. Seth Karlsson was appointed as sole trustee after Kerstin Thorborg’s death in 1970, to take charge of her musical estate. In it were many private film recordings, all her scores and recordings on HMV in 1928, Odeon in 1928–1931, Columbia in 1936 and RCA Victor in 1940, as well as 25 live recordings of her performances at the Metropolitan Opera in 1937–1949.

Kerstin Thorborg is buried in Hedemora Cemetery.

#Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg#Richard Wagner#Wagner#opera#classical music#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#Kerstin Thorborg#Thorborg#Mezzo-soprano#Royal College of Music#Royal Swedish Opera#chest voice#classical musician#classical musicians#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#maestro#classical history#the Metropolitan Opera#the Met#MET#metropolitan opera#contralto

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Stromboli (1950) **** / Italy

Italian neorealist film set in Stromboli in 1948 following Karin, played by a charismatic Ingrid Bergman, a foreigner who tries to make her way in the volcanic island, as her recent marriage turns abusive and the locals reject her. A devastating portrait of a woman's existential crisis with a revelatory final scene.

Directed by Roberto Rossellini, Rome, Open City (1945), Germany, Year Zero (1948)

0 notes

Text

Assistir Filme Através de um Espelho Online fácil

Assistir Filme Através de um Espelho Online Fácil é só aqui: https://filmesonlinefacil.com/filme/atraves-de-um-espelho/

Através de um Espelho - Filmes Online Fácil

Harriet Andersson é a frágil Karin. Afetada por crises de loucura, ela entra em conflito com seus familiares durante as férias de verão numa ilha remota. Um drama psicológico intenso em que Bergman disseca o processo de degradação de uma família.

0 notes

Text

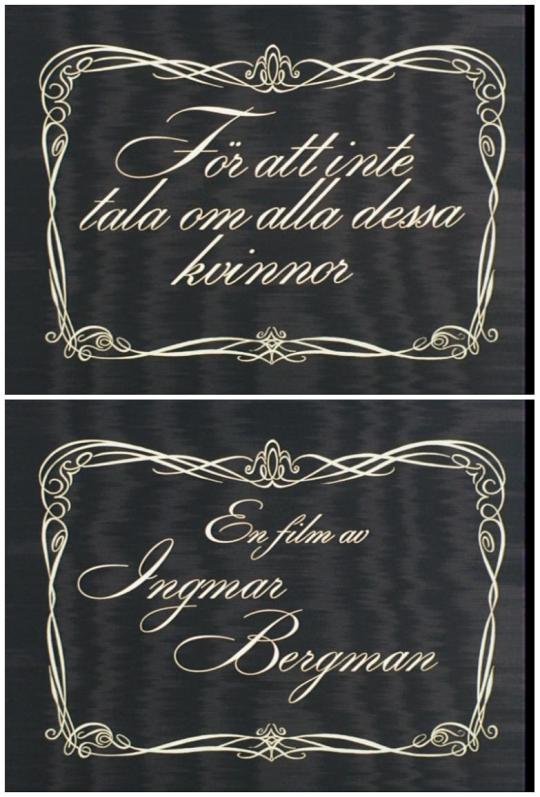

"För att inte tala om alla dessa kvinnor" (1964) - Ingmar Bergman

Films I've watched in 2022 (90/210)

Quite simply one of the funniest films I've ever seen!

#films watched in 2022#För att inte tala om alla dessa kvinnor#Jarl Kulle#Allan Edwall#Eva Dahlbeck#Bibi Andersson#Harriet Andersson#Barbro Hiort af Ornäs#Gertrud Fridh#Mona Malm#Karin Kavli#Ingmar Bergman#Sven Nykvist#film#Swedish film#Swedish cinema#comedy#motionpicturelover's screencaps#motionpicturelover's picture compilations

4 notes

·

View notes

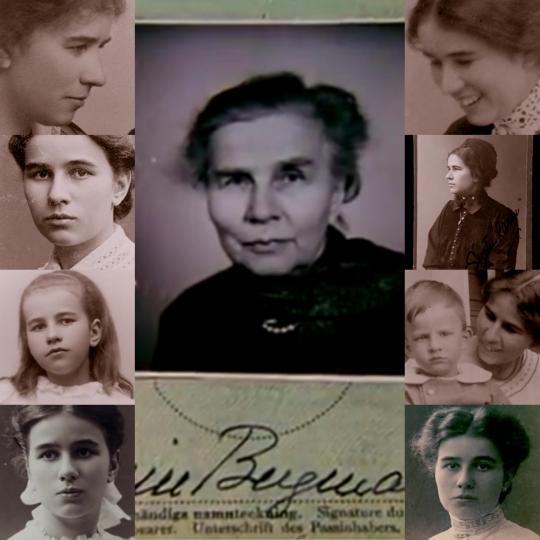

Photo

The Touch (Beröringen) | Ingmar Bergman | 1971

Elliott Gould and Bibi Andersson are looking at a photograph album and the camera focuses on one photo. In the film it is supposed to be Gould’s mother but is in fact a photograph of Ingmar Bergman’s mother Karin Bergman.

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seen in 2020:

Karin’s Face (Ingmar Bergman), 1984

#films#shorts#movies#stills#Karin's Face#Ingmar Bergman#Karin Bergman#Erik Bergman#Swedish#1980s#seen in 2020#docs#documentary

0 notes

Text

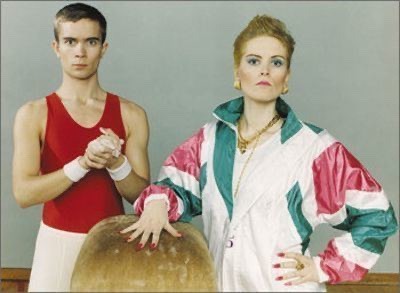

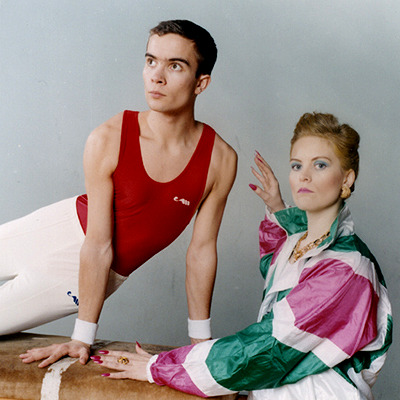

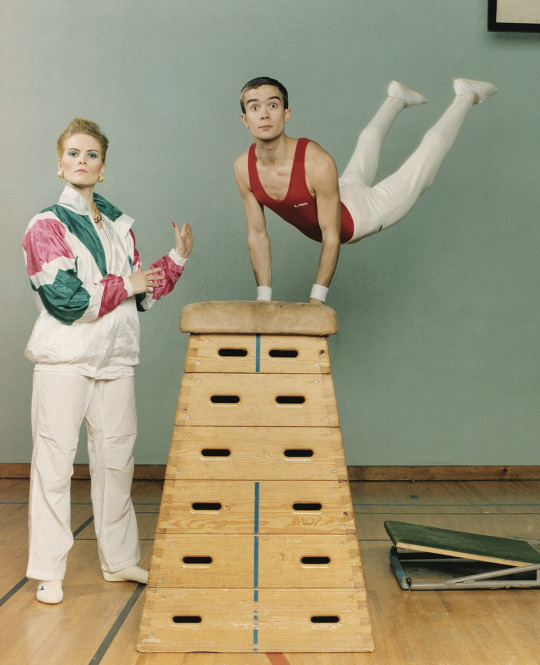

#Jon Bergman#2003#not mine#stolen images#rabid records#deep cuts#the knife#olof dreijer#karin dreijer#lord karin

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday Pernilla August!

#Pernilla August#celeb birthdays#actress#female directors#Beyond#The Best Intentions#Ingmar Bergman#Noomi Rapace#Karin Franz Körlof

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Max von Sydow, Harriet Andersson, and Gunnar Björnstrand in Through a Glass Darkly (Ingmar Bergman, 1961)

Cast: Harriet Andersson, Gunnar Björnstrand, Max von Sydow, Lars Passgård. Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman. Cinematography: Sven Nykvist. Production design: P.A. Lundgren. Film editing: Ulla Ryghe. Music: Erik Nordgren.

Ingmar Bergman's Through a Glass Darkly is usually grouped with his films Winter Light (1963) and The Silence (1963) as a kind of trilogy about the search for God, though Bergman denied having any intent to make a trilogy. It remains one of his most critically praised films, winning an Oscar for best foreign language film and receiving a nomination for Bergman's screenplay. But there are many, like me, who find it talky and stagy, despite Sven Nykist's beautiful cinematography and the effective use of location shooting on the island of Fårö in the Baltic. Some of the staginess, I think, comes from the casting of such familiar members of Bergman's virtual stock company as Harriet Andersson, Max von Sydow, and Gunnar Björnstrand. Andersson plays Karin, a woman just out of a mental hospital where she has recovered from a recent bout with what seems to be schizophrenia. She is married to Martin (von Sydow) and they have come to stay on the island with her father, David (Björnstrand), and her younger brother, Minus (Lars Passgård). David is distracted by his attempt to finish a novel, and both of his children rather resent his preoccupation. Martin confides in David that although Karin seems to have recovered, the doctors say that her illness is incurable -- a revelation that David records in his diary. Of course, Karin reads the diary, which precipitates a crisis, during which, among other things, she seduces her own brother. At the climax of the film, Karin has a vision of God as a giant spider that attempts to rape her. After she and Martin are taken away to the hospital, David has a moment alone with Minus, whom he assures that God and love are the same thing, and that their love for Karin will help her. Minus seems consoled by this thought, but perhaps even more by the fact that he has actually had a connection with his father: "Papa spoke to me" are the last words of the film. This resolution of the film's torments feels pat and theatrical and even upbeat, which may be why Bergman went on to make the much darker films about religious faith that constitute the rest of the trilogy. But it also suggests to me why I find Bergman's films so much less satisfying than those of Robert Bresson and Carl Theodor Dreyer, both of whom wrangled with God and faith in their films. Bresson and Dreyer liked to use unknown actors, and some of the familiarity we have with Bergman's players from other films distances us from the characters. We watch them acting, not being. When Bresson is dealing directly with religious faith in a film like Diary of a Country Priest (1951) or Dreyer is telling a story about a literal resurrection in Ordet (1955), we are forced to confront our own beliefs or absence of them. Bergman simply presents faith as a dramatic problem for his characters to work out, whereas Bresson and Dreyer drag us into the messy actuality of their characters' lives.

5 notes

·

View notes