#born into slavery in Tennessee

Text

#Lucy Higgs Nichols (April 10#1838 – January 25#1915)#born into slavery in Tennessee#but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed wi#Paul-Belgium#oldschool

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

I found out about a pair of interesting antique dolls the other day and, since dolls are one of your passions, I thought you might be interested (if you hadn’t heard of them before). A Civil War museum has ‘Lucy Ann’ and ‘Nina’, who were apparently used to smuggle quinine or morphine during the war, or so the story goes. (Searching “Lucy Ann quinine” brings up several articles on Google including how they were x-rayed to see if the folklore was true.)

Yes! I know about them. There's an article here.

The hollow heads alone are not sufficient proof- most dolls of their types had a "cavity" inside the head/shoulderplate, as the article says. But the doll donated in 1923 with her provenance stands a pretty high chance of having come from someone who remembered her history personally, at least. The other one, donated in 1976...well, hey, it's still a possibility.

A fascinating bit of history, though of course in support of the wrong side (since the dolls would have been smuggled through the Union blockade to aid Confederate troops).

#ask#anon#dolls#US history#american civil war#'you shouldn't be moralizing-' yeah no the Civil War was about slavery and the south was wrong#and there's a clear Correct Side and Incorrect Side in this conflict#and I refuse to tiptoe around that#some historical topics are Complex and Nuanced. who was right in the American Civil War is not one of them#and for the record: born and raised in Tennessee here

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

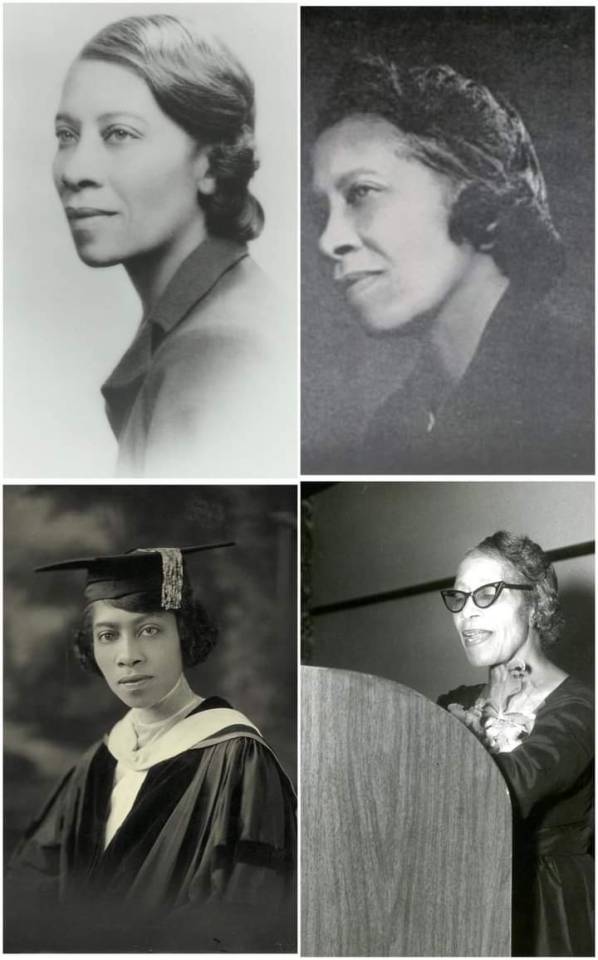

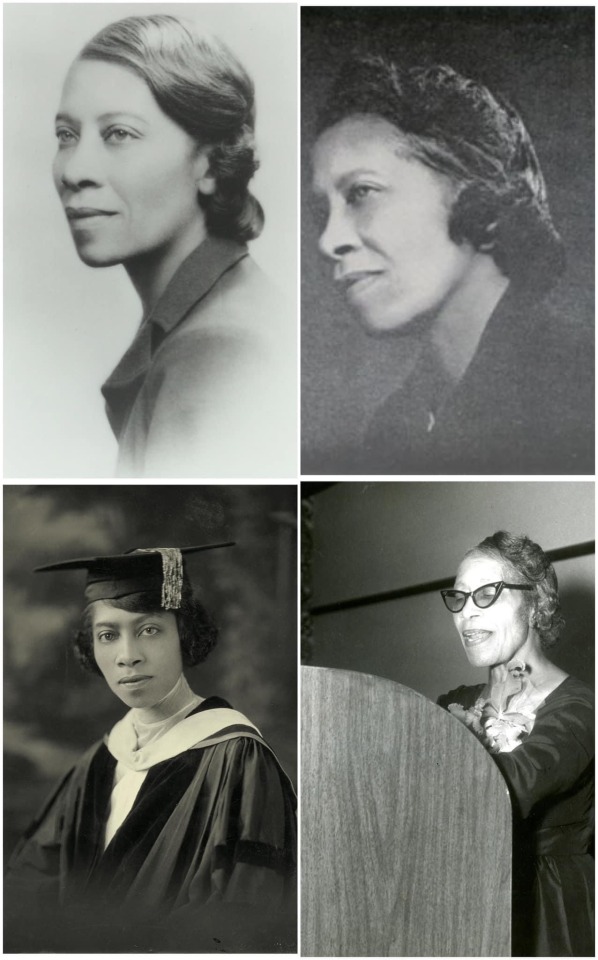

Eva Beatrice Dykes (13 August 1893 – 29 October 1986) was a prominent educator and the third black American woman to be awarded a PhD.

Dykes was born in Washington, D.C., on August 13, 1893, the daughter of Martha Ann (née Howard) and James Stanley Dykes. She attended M Street High School (later renamed Dunbar High School). She graduated summa cum laude from Howard University with a B.A. in 1914. While attending Howard University, where several family members had studied, Eva was initiated into the Alpha chapter of Delta Sigma Theta. At the end of her last semester she was awarded Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Incorporated's first official scholarship. After a short stint of teaching at Walden University in Nashville, Tennessee, Dykes attended Radcliffe College graduating magna cum laude with a second B.A. in 1917 and a M.A in 1918. While at Radcliffe she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. In 1920 Dykes began teaching at Dunbar High School, and in 1921 she received a PhD from Radcliffe (now a part of Harvard University). Her dissertation was titled “Pope and His influence in America from 1715 to 1815”, and explored the attitudes of Alexander Pope towards slavery and his influence on American writers. Dykes was the first black American woman to complete the requirements for a doctoral degree, however, because Radcliffe College held its graduation ceremonies later in the spring, she was the third to graduate, behind Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander (1921, University of Pennsylvania) and Georgiana R. Simpson (1921, University of Chicago).

After her graduation from Radcliffe in 1921, Dykes continued to teach at Dunbar High School until 1929 when she returned to Howard University as a member of the English Faculty. An excellent teacher, Dykes won a number of teaching awards during her 15 years of service at Howard University. Her publications include Readings from Negro Authors for Schools and Colleges co-authored with Lorenzo Dow Turner and Otelia Cromwell (1931) and The Negro in English Romantic Thought: Or a Study in Sympathy for the Oppressed (1942). In 1934 Dykes began writing a column in the Seventh-day Adventist periodical Message Magazine, this continued until 1984.

In 1920 Dykes joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and in 1944 she joined the faculty of the then small and unaccredited Seventh-day Adventist Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama, as the Chair of the English Department. She was the first staff member at Oakwood to hold a doctoral qualification and was instrumental in assisting the college to gain accreditation. Dykes retired in 1968 but returned to Oakwood to teach in 1970 and continued until 1975. In 1973 the Oakwood College library was named in her honor and in 1980 she was made a Professor Emerita. In 1975 the General Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church presented Dykes with a Citation of Excellence honouring her for an outstanding contribution to Seventh-day Adventist education. Dykes died in Huntsville on October 29, 1986, at the age of 93.

#black history#black literature#black tumblr#black excellence#black community#civil rights#black history is american history#black girl magic#blackexcellence365

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most people have heard or used the term UNCLE TOM when we refer to a sell-out, but did you know that the inference is totally wrong.

The real Uncle Tom was a hero, Josiah Henson, was an abolitionist who helped slaves escape among other great things.

Josiah Henson was born into slavery in 1789 in Charles County, Maryland. Growing up he watched his father receive beatings for standing up to his slave owner and also witnessed his father's ear being severed as part of the punishment and also his father being sold off.

Upon the death of his owner, Henson was also separated from his family in an estate sale. He remained on his new owner's farm in Montgomery County, Maryland, until he was an adult. As he aged he rose to become a trusted enslaved and supervised other enslaved people on the farm.

However, he used his new position to make his escape from slavery. Following the Underground Railroad, Henson escaped from Maryland to the Province of Upper Canada (Ontario), Canada with his wife and four children by way of the Niagara River in 1830.

Henson worked on farms in his first years in Canada to support his family. In 1834 founded a black settlement on rented land. He purchased 200 acres of land in Kent County and founded a settlement and laborer's school for other fugitive slaves.

Henson later became a Methodist preacher and a conductor on the Underground Railroad between Tennessee and Ontario helping the enslaved escape from slavery, he also served as a military officer in the British Army in Canada.

So stop calling these sell-outs Uncle Tom! That's a compliment! Its Sambo that was the sell-out,who would do anything for his slave masters' approval! Uncle Tom is a man to be respected.Not associated with the Sambo dog!

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

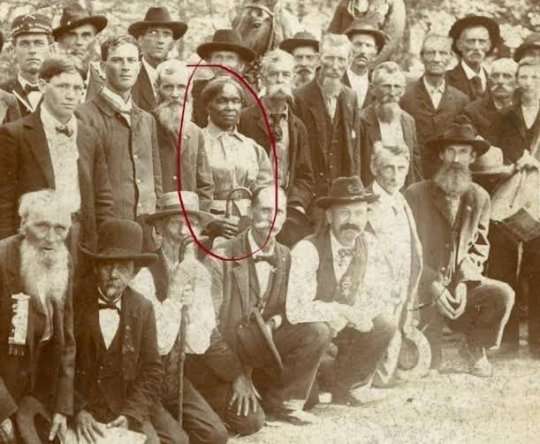

The lady circled in red was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby.

She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war. After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd. She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service.

The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted. The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. She died in 1915 and is buried in a cemetery in New Albany, Indiana.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin#lucy higgs nichols#civil war#tennessee#congress#army nurses#pension act of 1892#indiana#new albany

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

She drank whiskey, swore often, and smoked handmade cigars. She wore pants under her skirt and a gun under her apron. At six feet tall and two hundred pounds, Mary Fields was an intimidating woman.

Mary lived in Montana, in a town called Cascade. She was a special member of the community there. All schools would close on her birthday, and though women were not allowed entry into saloons, she was given special permission by the mayor to come in anytime and to any saloon she liked.

But Mary wasn’t from Montana. She was born into enslavement in Tennessee sometime in the early 1830s, and lived enslaved for more than thirty years until slavery was abolished. As a free woman, life led her first to Florida to work for a family and then Ohio when part of the family moved.

When Mary was 52, her close friend who lived in Montana became ill with pneumonia. Upon hearing the news, Mary dropped everything and came to nurse her friend back to health. Her friend soon recovered and Mary decided to stay in Montana settling in Cascade.

Her beginning in Cascade wasn’t smooth. To make ends meet, she first tried her hand at the restaurant business. She opened a restaurant, but she wasn’t much of a chef. And she was also too generous, never refusing to serve a customer who couldn’t pay. So the restaurant failed within a year.

But then in 1895, when in her sixties, Mary, or as “Stagecoach Mary” as she was sometimes called because she never missed a day of work, became the second woman and first African American to work as a mail carrier in the U.S. She got the job because she was the fastest applicant to hitch six horses.

Eventually she retired to a life of running a laundry business. And babysitting all the kids in town. And going to baseball games. And being friends with much of the townsfolk.

This was Mary Fields. A rebel, a legend.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

February is Black History Month, a time dedicated to honoring and celebrating the essential contributions of Black people in the story of America. National and local events and online celebrations will take place throughout the month to focus attention on Black people's achievements and history.

Since 1976, the US has marked the contributions of Black people and celebrated the history and culture of the Black experience in America every February. Read on to learn more about Black History Month and the ways in which you can participate.

The story of Black History Month

Born as a sharecropper in 1875, Carter G. Woodson went on to become a teacher and the second African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard. He founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History in 1915 and eventually became known as the "father of Black history."

On Feb. 7, 1926, Woodson announced the creation of "Negro History Week" to encourage and expand the teaching of Black history in schools. He selected February because the month marks the birthday of the two most famous abolitionists of the time -- Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Feb. 1 is also National Freedom Day, a celebration of the ratification of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the US.

By the 1940s, schools in Woodson's home state of West Virginia had begun expanding the celebration to a month, and by the 1960s, demands for proper Black history education spread across the country. Kent State's Black United Students proposed the idea of a Black History month in 1969 and celebrated the first event in February 1970. President Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month in 1976 during the US bicentennial.

The excellent history site BlackPast has a full biography of Carter Woodson and the origins of Black History Month.

Visit a Black or African American history museum

Almost every state in the US has a Black history museum or African American heritage site. The country's first and oldest is the Hampton University Museum in Hampton, Virginia. Like many other museums, it offers a virtual tour and online exhibits.

One of the most famous of these museums is the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. The museum, which is located steps away from where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, allows you to sit with Rosa Parks on the bus that inspired the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955, among many other powerful exhibits.

African-American heritage sites include historic parks and other significant locations and monuments in Black history. Some of the most popular include Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas, the epicenter of US school desegregation. You could also consider visiting the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta.

If there's no museum or heritage site near you, keep an eye out for the Black History Mobile Museum, which traverses the country all month and through the summer. Throughout February you can find the mobile museum in several states, starting in New Jersey on Feb. 1 and making its way through 12 other states. See the full list of 2023 tour dates here.

Learn about Black music history by listening online

Marley Marl and Mr. Magic were superstar rap DJs for WBLS FM in the 1980s. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

From spirituals and blues to the rise of jazz, R&B and hip hop, Black music has been entwined with American culture for centuries.

There are lots of ways to learn about and experience the power of Black American music online. One of the most extensive and free resources is the Black Music History Library, created by Jenzia Burgos. The compendium includes an array of Black music sources, with links to music samples, full recordings and interviews, as well as books and articles.

Another remarkable Black music website is the #312 Soul project. Originally launched as a month-long series on Chicago's Black music from 1955 to 1990, the site publishes original stories from Chicago residents about their personal experiences creating and enjoying Black music.

For snapshots of Black music between 1982 and 1999, check out the Hip Hop Radio Archive, a collection of radio show recordings from commercial, college and independent hip-hop stations. Of particular note are classic radio shows from New York City's WBLS, featuring Rap Attack with Marley Marl and Mr. Magic.

Online streaming music services also curate collections for Black History Month -- Spotify has an extensive collection of Black music in its Black History is Now collection. Tidal and Amazon Music also include special Black music collections on their services.

Support Black-owned businesses and restaurants

Becoming a customer of local Black businesses helps protect livelihoods and supports Black entrepreneurs.

If you aren't sure which businesses in your area are owned and operated by your Black neighbors, several resources can help. Start off by learning how to find Black-owned restaurants where you live.

Several directories have now been created to highlight and promote Black businesses. Official Black Wall Street is one of the original services that list businesses owned by members of the Black community.

Support Black Owned uses a simple search tool to help you find Black businesses, Shop Black Owned is an open-source tool operating in eight US cities, and EatOkra specifically helps people find Black-owned restaurants. Also, We Buy Black offers an online marketplace for Black businesses.

The online boutique Etsy highlights Black-owned vendors on its website -- many of these shop owners are women selling jewelry and unique art pieces. And if you're searching for make-up or hair products, check CNET's own list of Black-owned beauty brands.

Donate to Black organizations and charities

Donating money to a charity is an important way to support a movement or group, and your monetary contribution can help fund programs and pay for legal costs and salaries that keep an organization afloat. Your employer may agree to match employee donations, which would double the size of your contribution -- ask your HR department.

Nonprofit organizations require reliable, year-round funding to do their work. Rather than a lump sum, consider a monthly donation. Even if the amount seems small, your donation combined with others can help provide a steady stream of funds that allows programs to operate.

Here are some non-profit organizations advancing Black rights and equal justice and supporting Black youth:

Black Lives Matter

NAACP

Thurgood Marshall College Fund

Color of Change

Black Girls Code

The Black Youth Project

Attend local Black History Month events

Many cities, schools, and local organizations will host events celebrating Black History Month in February 2022. Check your local newspaper or city website to see what events are happening in your area -- for example, Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Baltimore and Louisville, Kentucky, have extensive events planned this month.

If you can't find anything in your area or don't want to attend events in person, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, is offering a handful of online Black History Month events throughout February.

Watch Black history documentaries and movies

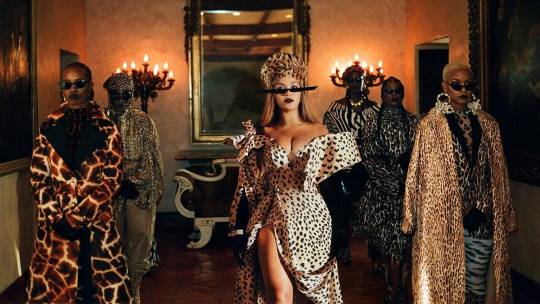

Black is King is an elaborately staged musical directed, written and produced by Beyoncé. Disney

You can find movies and documentaries exploring the Black experience right now on Netflix, Disney Plus and other streaming services.

The CNET staff has compiled a selection of feature films and documentaries for Black History Month 2023, including the wonderful Summer of Soul and Black is King. Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Hulu all have special collections of streaming movies and shows for Black History Month.

PBS also offers several free video documentary collections, which include smaller chunks of Black history for all ages. The collections include subjects like the Freedom Riders, the 1963 March on Washington and the Rise and Fall of Jim Crow.

Find Black authors and stories for yourself and your children

There are so many great books written by Black authors you should read -- not only during Black History Month but all year round. So, where do we start? Try your local library. Many will have Black History Month collections for both adults and kids.

Libraries will also often have Black History Month book recommendations by age. The San Diego Public Library, the Detroit Public Library and DC Public Library, for example, have programs and collections to browse for adults and children.

Next, try Black booksellers. The Noname Book Club, dedicated to amplifying diverse voices, has compiled a list of Black-owned bookshops across the US. The club also highlights two books a month by writers of color.

Dive deeper into Black history with online resources

The National Archives includes many primary resources from Black history in America. Rowland Sherman/National Archives

You can find remarkable Black history collections on government, educational and media sites. One of the best is the aforementioned BlackPast, which hosts a large collection of primary documents from African American history, dating back to 1724.

The National Archives also hosts a large collection of records, photos, news articles and videos documenting Black heritage in America. The expansive National Museum of African American History & Culture's Black History Month collection is likewise full of unique articles, videos and learning materials.

The New York Times' 1619 Project tracks the history of Black Americans from the first arrival of enslaved people in Virginia. The Pulitzer Center hosts the full issue of The 1619 Project as a PDF file on its 1619 Education site, which also offers reading guides, activity lessons and reporting related to the project.

You can buy The 1619 Project and the children's picture book version -- The 1619 Project: Born on the Water -- as printed books.

#Here Are 9 Ways to Celebrate Black History Month in 2023#Black History Month 2023#Black Lives Matter#Black History#Black History Month#Black History 2023 Celebrations#1619 Project

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

She drank whiskey, swore often, and smoked handmade cigars. She wore pants under her skirt and a gun under her apron. At six feet tall and two hundred pounds, Mary Fields was an intimidating woman.

Mary lived in Montana, in a town called Cascade. She was a special member of the community there. All schools would close on her birthday, and though women were not allowed entry into saloons, she was given special permission by the mayor to come in anytime and to any saloon she liked.

But Mary wasn’t from Montana. She was born into enslavement in Tennessee sometime in the early 1830s, and lived enslaved for more than thirty years until slavery was abolished. As a free woman, life led her first to Florida to work for a family and then Ohio when part of the family moved.

When Mary was 52, her close friend who lived in Montana became ill with pneumonia. Upon hearing the news, Mary dropped everything and came to nurse her friend back to health. Her friend soon recovered and Mary decided to stay in Montana settling in Cascade.

Her beginning in Cascade wasn’t smooth. To make ends meet, she first tried her hand at the restaurant business. She opened a restaurant, but she wasn’t much of a chef. And she was also too generous, never refusing to serve a customer who couldn’t pay. So the restaurant failed within a year.

But then in 1895, when in her sixties, Mary, or as “Stagecoach Mary” as she was sometimes called because she never missed a day of work, became the second woman and first African American to work as a mail carrier in the U.S. She got the job because she was the fastest applicant to hitch six horses.

Eventually she retired to a life of running a laundry business. And babysitting all the kids in town. And going to baseball games. And being friends with much of the townsfolk.

This was Mary Fields. A rebel, a legend.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nathan "Nearest" Green

An American head stiller, more commonly referred to as a master distiller. Born into slavery and emancipated after the American Civil War, he taught his distilling techniques to Jack Daniel, founder of the Jack Daniel's Tennessee whiskey distillery. Green was hired as the first master distiller for Jack Daniel Distillery, and he is the first African-American master distiller on record in the United States.

#jack daniels#tennessee#whiskey#jack daniels distillery#lynchburg#tennessee whiskey#jack daniel’s distillery#tenneessee whiskey#Nathan Green#Nathan Nearest Green

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

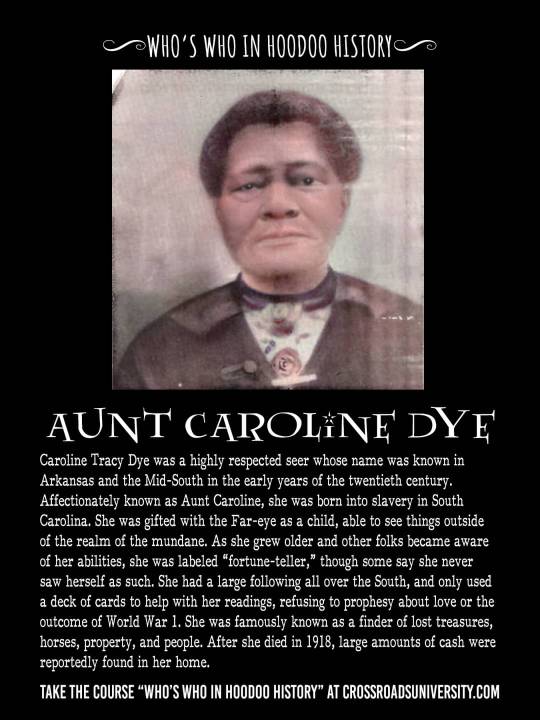

Who's Who in Hoodoo History: Aunt Caroline Dye

Caroline Tracy Dye (1843? –1918), better known as Aunt Caroline Dye, was born into slavery in South Carolina. She was gifted with the Far-eye as a child, able to see things outside of the realm of the mundane. As she grew older and other folks became aware of her abilities, she was labeled “fortune-teller”, though some say she never saw herself as such.

Aunt Caroline Dye was a highly respected seer whose name was recognized in Arkansas and the Mid-South in the early years of the twentieth century. She was born into slavery in Spartanburg, South Carolina, about 1843—there is conflicting information through the years about her date of birth and early life. According to Craig (2009): “Caroline Tracy became aware of her abilities as a seer while still a young child. She could reportedly see things outside her line of vision that others could not.”

Aunt Caroline had a large following from all over the south and in particular from Tennessee. According to Craig (2009) she only used a deck of cards to help with her readings, and she refused to give readings about love or the outcome of World War 1. “She did, however, tell many people the location of strayed or stolen livestock, sometimes giving specific directions, and she helped people locate missing jewelry. She gave visions of the future for her clients and offered advice on missing persons” (Craig, 2009). It was after Dye moved to Newport (Jackson County) that her reputation began to grow. She never claimed to be a fortune teller; that title was given to her by others. Her clients were both Black and White, and most showed their appreciation by paying her a few dollars for a reading, although payment was not required. Dye reported that she received twenty to thirty letters a day, with most including money for her services. It was said that some prominent White businessmen of Jackson County would not make important decisions before consulting her. All day long, people crowded into her home in Newport waiting for a reading. She took advantage of the large number of visitors and sold meals from her house. Dye reportedly only used a deck of cards to help her concentration and would not give readings about love or the outcome of World War I; she did, however, tell many people the location of strayed or stolen livestock, sometimes giving specific directions, and she helped people locate missing jewelry. She gave visions of the future for her clients and offered advice on missing persons. Dye died on September 26, 1918, in Newport. After her death, large amounts of cash were reportedly found in her house. She is buried in Gum Grove Cemetery in Newport next to her husband, who had died in 1907.

Over the years, Aunt Caroline Dye's legend has grown to describe her as seer to hoodoo woman, two headed doctor, fortune teller, psychic and conjure doctor.

Learn more about the OGs of Hoodoo: https://www.crossroadsuniversity.com/courses/who-s-who-in-hoodoo-history

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eva Beatrice Dykes (13 August 1893 – 29 October 1986) was a prominent educator and the third black American woman to be awarded a PhD. (Source)

Dykes was born in Washington, D.C., on August 13, 1893, the daughter of Martha Ann (née Howard) and James Stanley Dykes. She attended M Street High School (later renamed Dunbar High School). She graduated summa cum laude from Howard University with a B.A. in 1914. While attending Howard University, where several family members had studied, Eva was initiated into the Alpha chapter of Delta Sigma Theta. At the end of her last semester she was awarded Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Incorporated's first official scholarship. After a short stint of teaching at Walden University in Nashville, Tennessee, Dykes attended Radcliffe College graduating magna cum laude with a second B.A. in 1917 and a M.A in 1918. While at Radcliffe she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. In 1920 Dykes began teaching at Dunbar High School, and in 1921 she received a PhD from Radcliffe (now a part of Harvard University). Her dissertation was titled “Pope and His influence in America from 1715 to 1815”, and explored the attitudes of Alexander Pope towards slavery and his influence on American writers. Dykes was the first black American woman to complete the requirements for a doctoral degree, however, because Radcliffe College held its graduation ceremonies later in the spring, she was the third to graduate, behind Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander (1921, University of Pennsylvania) and Georgiana R. Simpson (1921, University of Chicago).

After her graduation from Radcliffe in 1921, Dykes continued to teach at Dunbar High School until 1929 when she returned to Howard University as a member of the English Faculty. An excellent teacher, Dykes won a number of teaching awards during her 15 years of service at Howard University. Her publications include Readings from Negro Authors for Schools and Colleges co-authored with Lorenzo Dow Turner and Otelia Cromwell (1931) and The Negro in English Romantic Thought: Or a Study in Sympathy for the Oppressed (1942). In 1934 Dykes began writing a column in the Seventh-day Adventist periodical Message Magazine, this continued until 1984.

In 1920 Dykes joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and in 1944 she joined the faculty of the then small and unaccredited Seventh-day Adventist Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama, as the Chair of the English Department. She was the first staff member at Oakwood to hold a doctoral qualification and was instrumental in assisting the college to gain accreditation. Dykes retired in 1968 but returned to Oakwood to teach in 1970 and continued until 1975. In 1973 the Oakwood College library was named in her honor and in 1980 she was made a Professor Emerita. In 1975 the General Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church presented Dykes with a Citation of Excellence honouring her for an outstanding contribution to Seventh-day Adventist education. Dykes died in Huntsville on October 29, 1986, at the age of 93.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

George Knox was born into slavery in Statesville, Tennessee, and by the end of his life he'd built a barbershop empire, rose and fell as the Republican Party's Kingmaker, took a bankrupt small newspaper and made it a national best-seller, owned a BASEBALL team (which I didn't even have time to get into in this video), ran for Congress (and got 12,000 write-in votes when the white parties had him removed from the ballot), was a friend of Booker T. Washington, Madam CJ Walker, and Frederick Douglass, and was one of the early financial backers of the NAACP in addition to DOZENS of other charity organizations.

I cannot overstate how incredible his story is, especially that he did all of it in a state considered one of the most racist and segregated in the US.

So proud to have written, produced, edited, and narrated this quick summary of his amazing life! I wish I had a whole hour to tell more of his story!

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From A Daily Dose of History on Facebook:

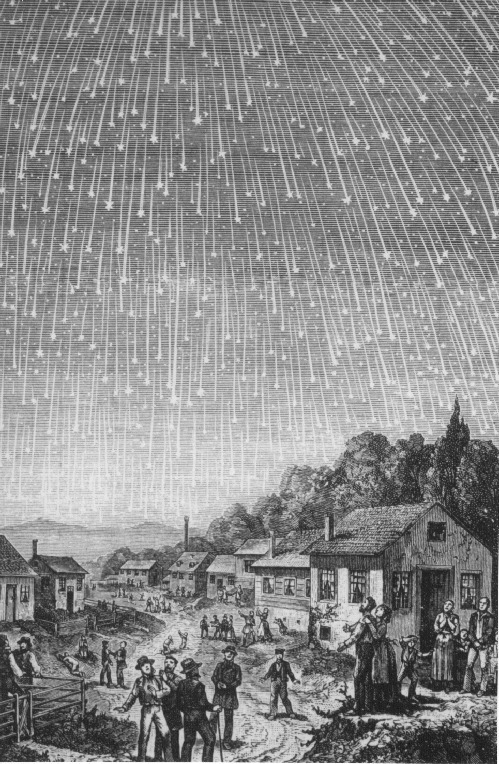

In the pre-dawn hours of November 12, 1833, the sky over North America seemed to explode with falling stars. Unlike anything anyone had ever seen before, and visible over the entire continent, an Illinois newspaper reported “the very heavens seemed ablaze.” An Alabama newspaper described “thousands of luminous bodies shooting across the firmament in every direction.” Observers in Boston estimated that there were over 72,000 “falling stars” visible per hour during the remarkable celestial storm.

The Lakota people were so amazed by the event that they reset their calendar to commemorate it. Joseph Smith, traveling with Mormon refugees, noted in his diary that it was surely a sign of the Second Coming. Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman, among many others, described seeing it. It became known as “The Night the Stars Fell.”

So, what was this amazing occurrence?

Many of those who witnessed it interpreted it as a sign of the Biblical end times, remembering words from the gospel of St. Mark: “And the stars of heaven shall fall, and the powers that are in heaven shall be shaken.” But Yale astronomer Denison Olmsted sought a scientific explanation, and shortly afterwards he issued a call to the public—perhaps the first scientific crowd-sourced data gathering effort. At Olmsted’s request, newspapers across the country printed his call for data: “As the cause of ‘Falling Stars’ is not understood by meteorologists, it is desirable to collect all the facts attending this phenomenon, stated with as much precision as possible. The subscriber, therefore, requests to be informed of any particulars which were observed by others, respecting the time when it was first discovered, the position of the radiant point above mentioned, whether progressive or stationary, and of any other facts relative to the meteors.”

Olmsted published his conclusions the following year, the information he had received from lay observers having helped him draw new scientific conclusions in the study of meteors and meteor showers. He noted that the shower radiated from a point in the constellation Leo and speculated that it was caused by the earth passing through a cloud of space dust. The event, and the public’s fascination with it, caused a surge of interest in “citizen science” and significantly increased public scientific awareness.

Nowadays we know that every November the earth passes through the debris in the trail of a comet known as Tempel-Tuttle, causing the meteor showers we know as the Leonids. Impressive every year, every 33 year or so they are especially spectacular, although very rarely attaining the magnificence of the 1833 event.

The Leonid meteor showers are ongoing now and are expected to peak on November 18. But don’t expect a show like the one in 1833. This year at its peak the Leonids are expected to generate 15 “shooting stars” per hour.

November 12, 1833, one hundred eighty-nine years ago today, was “The Night the Stars Fell.”

The image is an 1889 depiction of the event.

From The Irish Times:

In Maury County, Tennessee, a small girl, born into slavery, was awoken in her cot by the sound of screaming.

The story of Amanda Young, who died in 1920, was recounted in 2010 by her great-great granddaughter Angela Y Walton-Raji as part of a family oral history. Walton-Raji had travelled to Chicago to meet her own elderly cousin, Frances Swader, and to hear from her Young’s story.

Walton-Raji reported Young’s words thus: “Somebody in the quarters started yellin’ in the middle of the night to come out and to look up at the sky. We went outside and there they was a-fallin’ everywhere!

“Big stars coming down real close to the groun’ and just before they hit the ground they would burn up! We was all scared. Some o’ the folks was screamin’, and some was prayin’. We all made so much noise, the white folks came out to see what was happenin’. They looked up and then they got scared, too.

“But then the white folks started callin’ all the slaves together, and for no reason, they started tellin’ some of the slaves who their mothers and fathers was, and who they’d been sold to and where. The old folks was so glad to hear where their people went. They made sure we all knew what happened … you see, they thought it was Judgement Day.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lady circled in the photo was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby.

She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service.

The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted.

The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. Beloved by the troops who referred to her as “Aunt Lucy,” Nichols was the only woman to receive an honorary induction into the Grand Army of the Republic, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in New Albany with full military honors in 1915.

Source: African Archives Twitter

175 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗠𝗮𝗿𝘁𝗵𝗮 𝗔𝗻𝗻 𝗥𝗶𝗰𝗸𝘀 (1817–1901) 𝘄𝗮𝘀 𝗮𝗻 𝗔𝗺𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗰𝗼-𝗟𝗶𝗯𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗮𝗻 𝘄𝗼𝗺𝗮𝗻. 𝗕𝗼𝗿𝗻 𝗶𝗻𝘁𝗼 𝘀𝗹𝗮𝘃𝗲𝗿𝘆 𝗶𝗻 𝗧𝗲𝗻𝗻𝗲𝘀𝘀𝗲𝗲, 𝘀𝗵𝗲 𝗲𝗺𝗶𝗴𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝘁𝗼 𝗟𝗶𝗯𝗲𝗿𝗶𝗮 𝗶𝗻 1830. 𝗜𝗻 1892 𝘀𝗵𝗲 𝗳𝘂𝗹𝗳𝗶𝗹𝗹𝗲𝗱 𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗱𝗿𝗲𝗮𝗺 𝘄𝗵𝗲𝗻 𝘀𝗵𝗲 𝗿𝗲𝗰𝗲𝗶𝘃𝗲𝗱 𝗮 𝗥𝗼𝘆𝗮𝗹 𝗔𝘂𝗱𝗶𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗲 𝘄𝗶𝘁𝗵 𝗤𝘂𝗲𝗲𝗻 𝗩𝗶𝗰𝘁𝗼𝗿𝗶𝗮 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗴𝗮𝘃𝗲 𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗮 𝗾𝘂𝗶𝗹𝘁 𝘀𝗵𝗲 𝗵𝗮𝗱 𝗺𝗮𝗱𝗲.

Ricks was born into slavery in Tennessee. Along with the rest of her family, she was purchased by her father George Erskine and became free. She and her family moved to Clay-Ashland, Liberia, as part of the American Colonization Society in 1830. While she was living in Liberia, she married Zion Harris who she had met along her travels while in Tennessee. She had begun traveling with Liberia’s first president Joseph Jenkins Roberts in 1848 and visited both the United States and the United Kingdom. Martha earned her living raising turkeys, ducks, and sheep as well as growing crops. She was also known for being well versed in field of needlework. Martha was very good at her needlework and won several contests for the silk stocking that she made.

Over the years, Martha developed an interest in Queen Victoria. She was determined that one day she would meet the queen. Over the course of 25 years, Martha worked on a quilt that she wanted to give to the queen when she met her. The quilt that she made depicted the Liberian Coffee Tree and was made of silk cotton. Its pattern included over 300 green leaves, as well as coffee berries in red. There was also a trunk in the center of the quilt and the background was white. Finally, when she turned 76, Martha was able to travel to England and was given audience with the queen through the help of Liberian Ambassador Edward Blyden. She met the queen at Windsor Castle on July 16, 1892, accompanied by First Lady Jane Roberts where she gave her the quilt. Martha died in 1901.

#martha ricks#tennessee#kemetic dreams#queen victoria#liberian#liberian coffee tree#african#africans

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black women who fought for reparations.

Àbáké Matilda McCrear (she was just two years old when she arrived in Mobile, Alabama, in July 1860, a captive aboard the infamous Clotilda, the last known slave ship to bring Africans to America. She died in 1940 at the age 82, making her the last known survivor of the last known slave ship.)

...Matilda had walked the 17 miles to Selma to request that she receive some compensation, too, for being kidnapped and brought to the country as a toddler. As proof that she was from Africa, she showed the marks on her cheek.

The judge denied her any reparations just as Timothy Meaher, the slaveowner who organized the illegal Clotilda journey, had denied reparations to the ship’s survivors back in 1865.

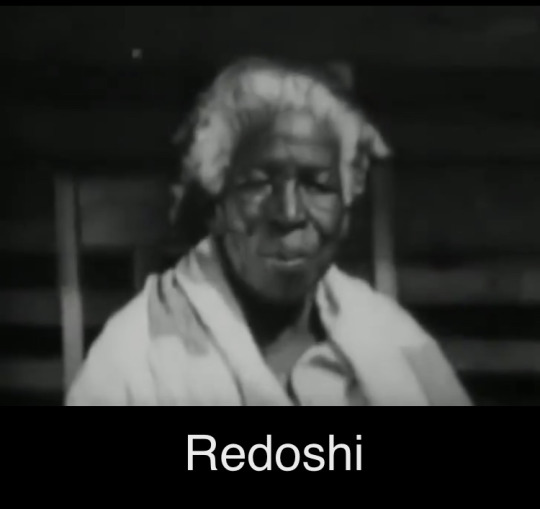

McCrear made a claim for herself and Redoshi.

Redoshi, also known as Sally Smith, was the second to last living, African-born survivor of North American slavery, and the only female survivor of the transatlantic slave trade known to have been recorded on film. Born on the coast of West Africa in what is present day Benin, Redoshi was one of about 110 West African children and adults who were human cargo of the schooner Clotilda, the last slave ship to reach the United States. She may have been 110 years old when she died in Alabama in 1937.

*************************************************

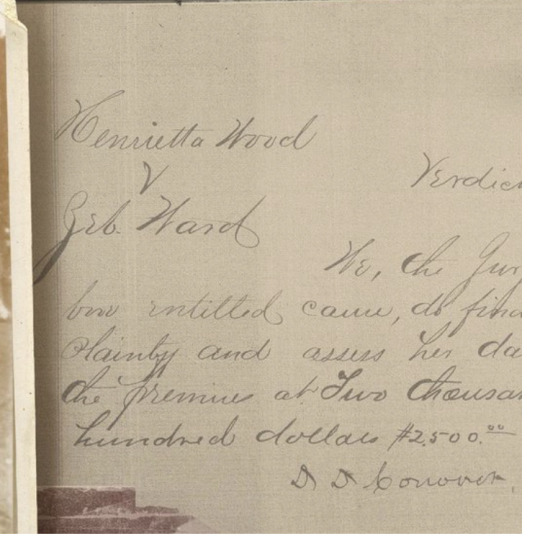

In 1870, Henrietta Wood Sued for Reparations—and Won

The $2,500 verdict, the largest ever of its kind, offers evidence of the generational impact such awards can have.

*************************************************

Callie House is most famous for her efforts to gain reparations for former slaves and is regarded as the early leader of the reparations movement among African American political activists. Callie Guy was born a slave in Rutherford Country near Nashville, Tennessee. Her date of birth is usually assumed to be 1861, but due to the lack of birth records for slaves, this date is not certain.

*************************************************

Belinda Sutton [also known as Belinda Royal/Royall] was the author of one of the earliest known slave narratives by an African woman in the United States and a successful early petitioner for reparations for enslavement.

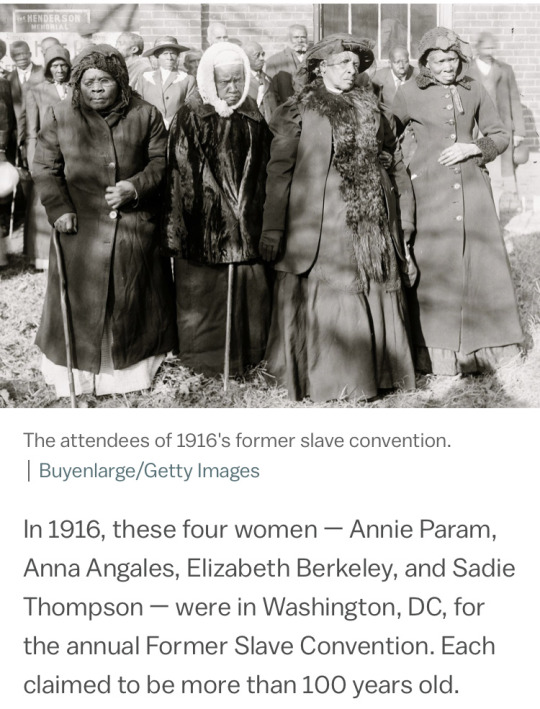

#Annie Param#Anna Angales#Elizabeth Berkeley#Sadie Thompson#Matilda McCrear#Redoshi#Henrietta Wood#Callie House#Belinda Sutton#Black History Month#reparations#HERstory#BHM

3 notes

·

View notes