#delano grape strike

Photo

Labor Day 2022

Today is Labor Day, a holiday in celebration of the workers of the United States and the struggle of the Labor Movement for the rights and freedoms workers have today. It is a good day to remember that for many the fight is not over, and that we should support our fellow workers whenever possible.

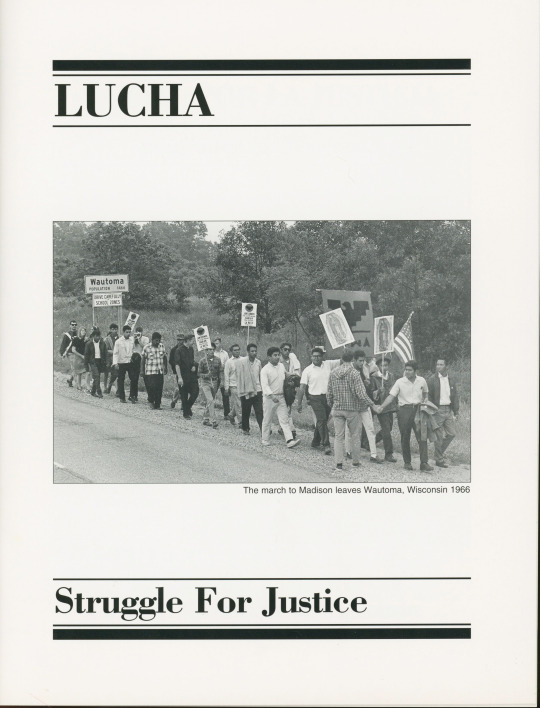

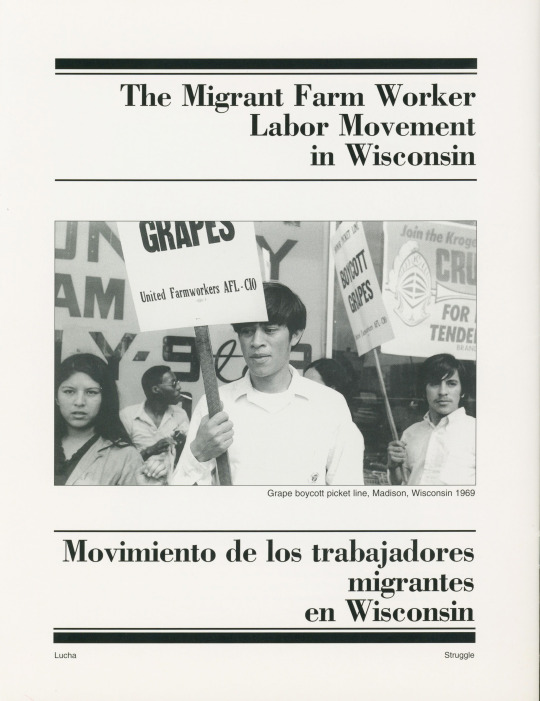

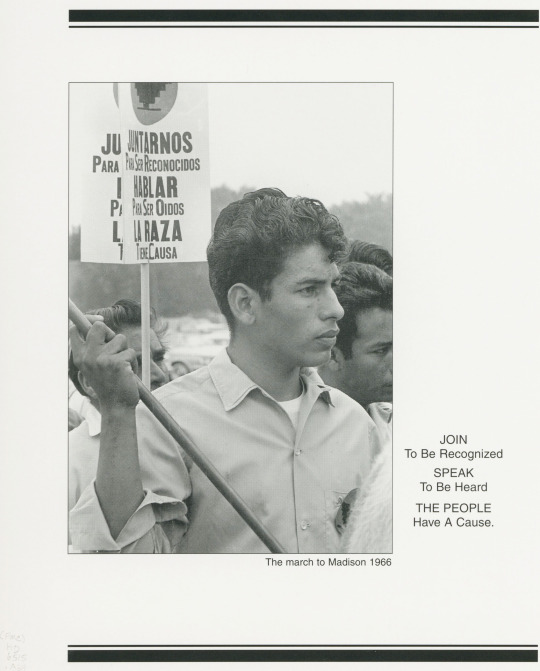

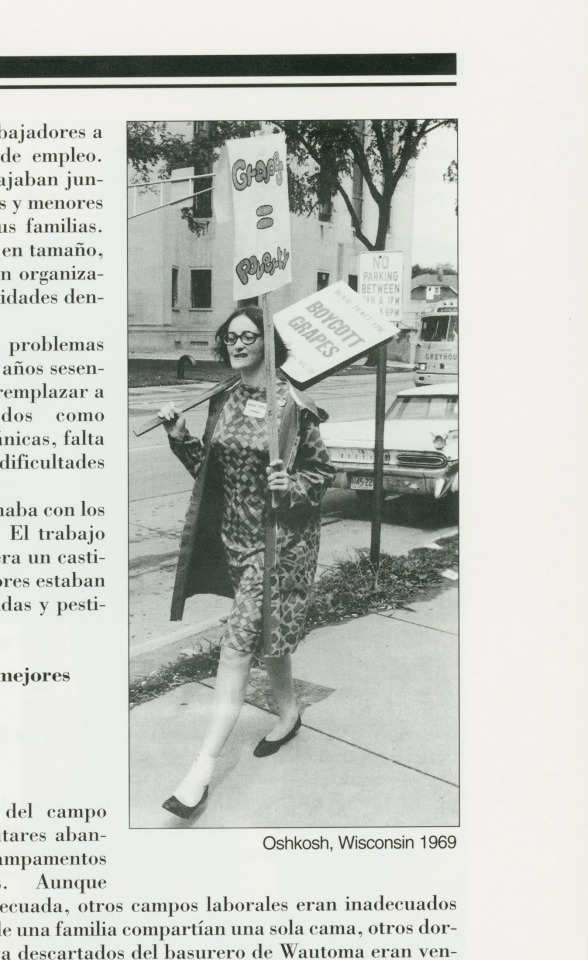

In that light, we’re sharing Lucha por la Justicia / Struggle for Justice published by the Wisconsin Labor History Society in 1998. The book is about the migrant farm worker labor movement in Wisconsin, and in particular strikes and boycotts of the mid-1960s. Agricultural workers, and especially those who are migrant workers, are one of the least protected groups of workers in the country. in 1966, migrant workers in Wisconsin marched 80 miles from Wautoma to Madison to present their demands to the state government. Among their demands were improved housing, a $1.25 minimum hourly wage, and accident and hospitalization insurance. Agricultural workers in Wisconsin also participated in and raised awareness for the Delano Grape Strike of the late 1960s.

Just last week, members of United Farm Workers union in California marched 335 miles from Delano to Sacramento in support of a bill that would make it easier for agricultural workers in the state to vote in union elections. Currently they can only vote in person in union elections, which creates opportunities for retaliation and intimidation by farm owners against those who vote to unionize and prevents migrant workers from voting if they are not in the state at the time of the election. Renowned internet labor supporter and cat Jorts supported their march by marching his furry little paws around his place of employment (which is unionized, fyi). Unions are one of the best ways for workers to make sure that they are not exploited and allow them to collectively bargain with their bosses for fair wages and treatment.

So, as we enjoy our long weekend and most likely grill some burgers and hotdogs and enjoy some sweet corn from a roadside stand, let’s not forget the workers who literally make it possible for us to have food on our tables (or any workers!).

-- Alice, Special Collections Department Manager

#Labor Day#unions#strikes#huelga#Delano Grape Strike#United Farm Workers#Wisconsin Labor History Society#farm workers#agricultural workers#Jorts the Cat#Jorts and Jean#Jorts#holidays#Alice

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

It makes me so mad how Filipinos have been surgically removed from the history of the Delano Grape Strike. They started it!!! The Mexicans were originally scabs! Cesar Chavez was the face of the movement because he was the most charismatic leader, but it was Larry Itliong, the Filipino leader, who approached Chavez to join their strike. It started with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, it started with the Filipinos!

#history#racism#anti-asian racism#delano grape strike#asian american history#filipino american#larry itliong#I said this

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve now had two students make callbacks to previous units, is this what success feels like??

#one of them connected wedge issues to gridlock which was like 4 units and three months ago#and another just connected a core value to the Delano grape strike from our previous unit two weeks ago#oh my god did they actually learn from me#i’m grading tests rn for context but holy shit

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

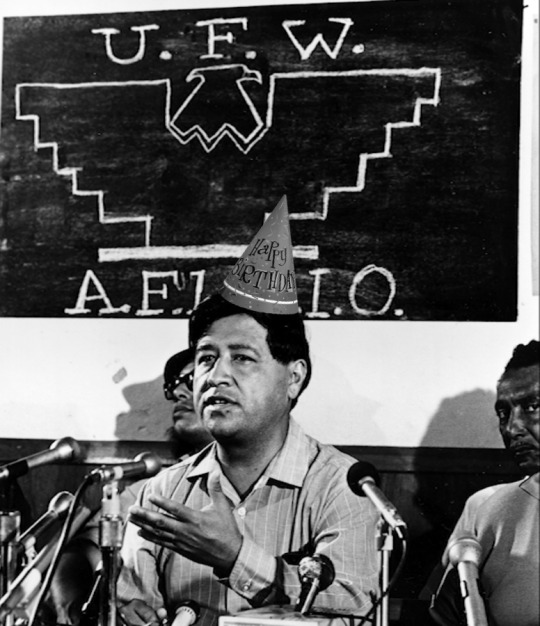

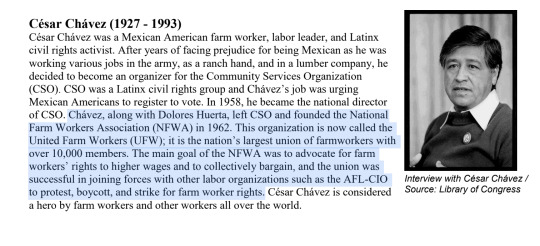

Happy birthday, Cesar Chavez! (March 31, 1927)

A founder and leader of the United Farm Workers union, Cesar Chavez was born in Yuma, Arizona, before his family joined many others seeking a better life in California during the Great Depression. Like the rest of his family, Chavez worked as an agricultural laborer before beginning to involve himself in labor organization and voter registration efforts. In the early 1960s, Chavez helped to found the predecessor to the UFW, and led strikes which helped to build both the union and Chavez's personal reputation in the labor movement. The most significant of these was the Delano grape strike, which lasted from 1965 to 1970, and resulted in victory for the union while cementing Chavez's pedigree as an effective labor leader. Chavez was able to effectively utilize consumer boycotts, direct action, and inter-ethnic solidarity to lead the UFW to victory. These tactics would become a hallmark of the UFW's strategies moving forward, and before long it began expansion efforts outside of California. He continued to lead the UFW until his death in 1993, and remains an icon of the American labor movement, although some of his positions, such as his opposition to undocumented immigants and support for Ferdinand Marcos and the Synanon cult, have experienced scrutiny and criticism.

"What we do know absolutely is that human lives are worth more than grapes and that innocent-looking grapes on the table may disguise poisonous residues hidden deep inside where washing cannot reach."

426 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK, I'll bite - what's the deal with the United Farm Workers? What were their strengths and weaknesses compared to other labor unions?

It is not an easy thing to talk about the UFW, in part because it wasn't just a union. At the height of its influence in the 1960s and 1970s, it was also a civil rights movement that was directly inspired by the SCLC campaigns of Martin Luther King and owed its success as much to mass marches, hunger strikes, media attention, and the mass mobilization of the public in support of boycotts that stretched across the United States and as far as Europe as it did to traditional strikes and picket lines.

It was also a social movement that blended powerful strains of Catholic faith traditions with Chicano/Latino nationalism inspired by the black power movement, that reshaped the identity of millions away from asimilation into white society and towards a fierce identification with indigeneity, and challenged the racist social hierarchy of rural California.

It was also a political movement that transformed Latino voting behavior, established political coalitions with the Kennedys, Jerry Brown, and the state legislature, that pushed through legislation and ran statewide initiative campaigns, and that would eventually launch the careers of generations of Latino politicians who would rise to the very top of California politics.

However, it was also a movement that ultimately failed in its mission to remake the brutal lives of California farmworkers, which currently has only 7,000 members when it once had more than 80,000, and which today often merely trades on the memory of its celebrated founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez rather than doing any organizing work.

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

The Origins of the UFW:

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

In the 1950s, both Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez were community organizers working for a group called the Community Service Organization (an affiliate of Saul Alinsky's Industrial Areas Foundation) that sought to aid farmworkers living in poverty. Huerta and Chavez were trained in a novel strategy of grassroots, door-to-door organizing aimed not at getting workers to sign union cards, but to agree to host a house meeting where co-workers could gather privately to discuss their problems at work free from the surveillance of their bosses. This would prove to be very useful in organizing the fields, because unlike the traditional union model where organizers relied on the NRLB's rulings to directly access the factory floors, Central California farms were remote places where white farm owners and their white overseers would fire shotguns at brown "trespassers" (union-friendly workers, organizers, picketers).

In 1962, Chavez and Huerta quit CSO to found the National Farm Workers Association, which was really more of a worker center offering support services (chiefly, health care) to independent groups of largely Mexican farmworkers. In 1965, they received a request to provide support to workers dealing with a strike against grape growers in Delano, California.

In Delano, Chavez and Huerta met Larry Itliong of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which was a more traditional labor union of migrant Filipino farmworkers who had begun the strike over sub-minimum wages. Itliong wanted Chavez and Huerta to organize Mexican farmworkers who had been brought in as potential strikebreakers and get them to honor the picket line.

The result of their collaboration was the formation of the United Farm Workers as a union of the AFL-CIO. The UFW would very much be marked by a combination of (and sometimes conflict between) AWOC's traditional union tactics - strikes, pickets, card drives, employer-based campaigns, and collective bargaining for union contracts - and NFWA's social movement strategy of marches, boycotts, hunger strikes, media campaigns, mobilization of liberal politicians, and legislative campaigns.

1965 to 1970: the Rise of the UFW:

While the strike starts with 2,000 Filipino workers and 1,200 Mexican families targeting Delano area growers, it quickly expanded to target more growers and bring more workers to the picket lines, eventually culminating in 10,000 workers striking against the whole of the table grape growers of California across the length and breadth of California.

Throughout 1966, the UFW faced extensive violence from the growers, from shotguns used as "warning shots" to hand-to-hand violence, to driving cars into pickets, to turning pesticide-spraying machines onto picketers. Local police responded to the violence by effectively siding with the growers, and would arrest UFW picketers for the crime of calling the police.

Chavez strongly emphasized a non-violent response to the growers' tactics - to the point of engaging in a Gandhian hunger strike against his own strikers in 1968 to quell discussions about retaliatory violence - but also began to employ a series of civil rights tactics that sought to break what had effectively become a stalemate on the picket line by side-stepping the picket lines altogether and attacking the growers on new fronts.

First, he sought the assistance of outside groups and individuals who would be sympathetic to the plight of the farmworker and could help bring media attention to the strike - UAW President Walter Reuther and Senator Robert Kennedy both visited Delano to express their solidarity, with Kennedy in particular holding hearings that shined a light on the issue of violence and police violations of the civil rights of UFW picketers.

Second, Chavez hit on the tactic of using boycotts as a way of exerting economic pressure on particular growers and leveraging the solidarity of other unions and consumers - the boycotts began when Chavez enlisted Dolores Huerta to follow a shipment of grapes from Schenley Industries (the first grower to be boycotted) to the Port of Oakland. There, Huerta reached out to the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and persuaded them to honor the boycott and refuse to handle non-union grapes. Schenley's grapes started to rot on the docks, cutting them off from the market, and between the effects of union solidarity and growing consumer participation in the UFW's boycotts, the growers started to come under real economic pressure as their revenue dropped despite a record harvest.

Throughout the rest of the Delano grape strike, Dolores Huerta would be the main organizer of the national and internal boycotts, travelling across the country (and eventually all the way to the UK) to mobilize unions and faith groups to form boycott committees and boycott houses in major cities that in turn could educate and mobilize ordinary consumers through a campaign of leafleting and picketing at grocery stores.

Third, the UFW organized the first of its marches, a 300-mile trek from Delano to the state capital of Sacramento aimed at drawing national attention to the grape strike and attempting to enlist the state government to pass labor legislation that would give farmworkers the right to organize. Carefully organized by Cesar Chavez to draw on Mexican faith traditions, the march would be labelled a "pilgrimage," and would be timed to begin during Lent and culminate during Easter. In addition to American flags and the UFW banner, the march would be led by "pilgrims" carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadelupe.

While this strategy was ultimately effective in its goal of influencing the broader Latino community in California to see the UFW as not just a union but a vehicle for the broader aspirations of the whole Latino community for equality and social justice, what became known in Chicano circles as La Causa, the emphasis on Mexican symbolism and Chicano identity contributed to a growing tension with the Filipino half of the UFW, who felt that they were being sidelined in a strike they had started.

Nevertheless, by the time that the UFW's pilgrimage arrived at Sacramento, news broke that they had won their first breakthrough in the strike as Schenley Industries (which had been suffering through a four-month national boycott of its products) agreed to sign the first UFW union contract, delivering a much-needed victory.

As the strike dragged on, growers were not passively standing by - in addition to doubling down on the violence by hiring strikebreakers to assault pro-UFW farmworkers, growers turned to the Teamsters Union as a way of pre-empting the UFW, either by pre-emptively signing contracts with the Teamsters or effectively backing the Teamsters in union elections.

Part of the darker legacy of the Teamsters is that, going all the back to the 1930s, they have a nasty habit of raiding other unions, and especially during their mobbed-up days would work with the bosses to sign sweetheart deals that allowed the Teamsters to siphon dues money from workers (who had not consented to be represented by the Teamsters, remember) while providing nothing in the way of wage increases or improved working conditions, usually in exchange for bribes and/or protection money from the employers. Moreover, the Teamsters had no compunction about using violence to intimidate rank-and-file workers and rival unions in order to defend their "paper locals" or win a union election. This would become even more of an issue later on, but it started up as early as 1966.

Moreover, the growers attempted to adapt to the UFW's boycott tactics by sharing labels, such that a boycotted company would sell their products under the guise of being from a different, non-boycotted company. This forced the UFW to change its boycott tactics in turn, so that instead of targeting individual growers for boycott, they now asked unions and consumers alike to boycott all table grapes from the state of California.

By 1970, however, the growing strength of the national grape boycott forced no fewer than 26 Delano grape growers to the bargaining table to sign the UFW's contracts. Practically overnight, the UFW grew from a membership of 10,000 strikers (none of whom had contracts, remember) to nearly 70,000 union members covered by collective bargaining agreements.

1970 to 1978: The UFW Confronts Internal and External Crises

Up until now, I've been telling the kind of simple narrative of gradual but inevitable social progress that U.S history textbooks like, the Hollywood story of an oppressed minority that wins a David and Goliath struggle against a violent, racist oligarchy through the kind of non-violent methods that make white allies feel comfortable and uplifted. (It's not an accident that the bulk of the 2014 film Cesar Chavez starring Michael Peña covers the Delano Grape Strike.)

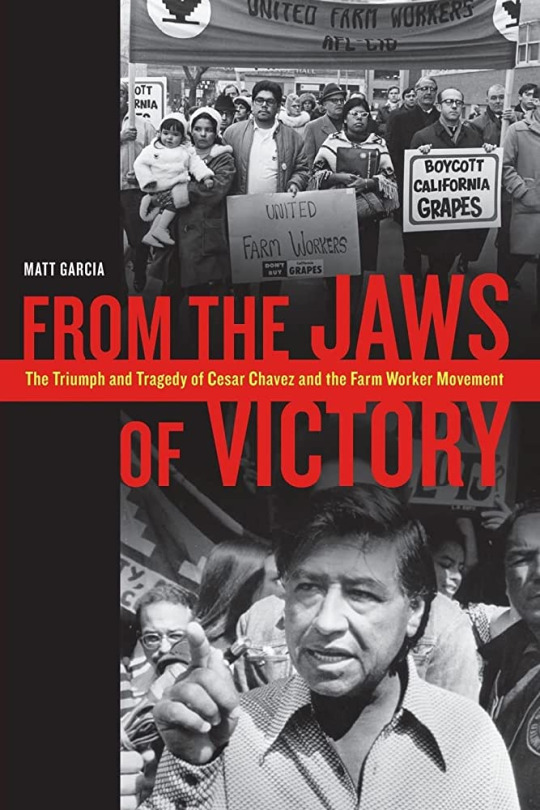

It's also the period in which the UFW's strengths as an organization that came out of the community organizing/civil rights movement were most on display. In the eight years that followed, however, the union would start to experience a series of crises that would demonstrate some of the weaknesses of that same institutional legacy. As Matt Garcia describes in From the Jaws of Victory, in the wake of his historic victory in 1970, Cesar Chavez began to inflict a series of self-inflicted injuries on the UFW that crippled the functioning of the union, divided leadership and rank-and-file alike, and ultimately distracted from the union's external crises at a time when the UFW could not afford to be distracted.

That's not to say that this period was one of unbroken decline - as we'll discuss, the UFW would win many victories in this period - but the union's forward momentum was halted and it would spend much of the 1970s trying to get back to where it was at the very start of the decade.

To begin with, we should discuss the internal contradictions of the UFW: one of the major features of the UFW's new contracts was that they replaced the shape-up with the hiring hall. This gave the union an enormous amount of power in terms of hiring, firing and management of employees, but the quid-pro-quo of this system is that it puts a significant administrative burden on the union. Not only do you have to have to set up policies that fairly decide who gets work and when, but you then have to even-handedly enforce those policies on a day-to-day basis in often fraught circumstances - and all of this is skilled white-collar labor.

This ran into a major bone of contention within the movement. When the locus of the grape strike had shifted from the fields to the urban boycotts, this had made a new constituency within the union - white college-educated hippies who could do statistical research, operate boycott houses, and handle media campaigns. These hippies had done yeoman's work for the union and wanted to keep on doing that work, but they also needed to earn enough money to pay the rent and look after their growing families, and in general shift from being temporary volunteers to being professional union staffers.

This ran head-long into a buzzsaw of racial and cultural tension. Similar to the conflicts over the role of white volunteers in CORE/SNCC during the Civil Rights Movement, there were a lot of UFW leaders and members who had come out of the grassroots efforts in the field who felt that the white college kids were making a play for control over the UFW. This was especially driven by Cesar Chavez' religiously-inflected ideas of Catholic sacrifice and self-denial, embodied politically as the idea that a salary of $5 a week (roughly $30 a week in today's money) was a sign of the purity of one's "missionary work." This worked itself out in a series of internicene purges whereby vital college-educated staff were fired for various crimes of ideological disunity.

This all would have been survivable if Chavez had shown any interest in actually making the union and its hiring halls work. However, almost from the moment of victory in 1970, Chavez showed almost no interest in running the union as a union - instead, he thought that the most important thing was relocating the UFW's headquarters to a commune in La Paz, or creating the Poor People's Union as a way to organize poor whites in the San Joaquin Valley, or leaving the union altogether to become a Catholic priest, or joining up with the Synanon cult to run criticism sessions in La Paz. In the mean-time, a lot of the UFW's victories were withering on the vine as workers in the fields got fed up with hiring halls that couldn't do their basic job of making sure they got sufficient work at the right wages.

Externally, all of this was happening during the second major round of labor conflicts out in the fields. As before, the UFW faced serious conflicts with the Teamsters, first in the so-called "Salad Bowl Strike" that lasted from 1970-1971 and was at the time the largest and most violent agricultural strike in U.S history - only then to be eclipsed in 1973 with the second grape strike. Just as with the Salinas strike, the grape growers in 1973 shifted to a strategy of signing sweetheart deals with the Teamsters - and using Teamster muscle to fight off the UFW's new grape strike and boycott. UFW pickets were shot at and killed in drive-byes by Teamster trucks, who then escalated into firebombing pickets and UFW buildings alike.

After a year of violence, reduced support from the rank-and-file, and declining resources, Chavez and the UFW felt that their backs were up against a wall - and had to adjust their tactics accordingly. With the election of Jerry Brown as governor in 1974, the UFW pivoted to a strategy of pressuring the state government to enact a California Agricultural Labor Relations Act that would give agricultural workers the right to organize, and with that all the labor protections normally enjoyed by industrial workers under the Federal National Labor Relations Act - at the cost of giving up the freedom to boycott and conduct secondary strikes which they had had as outsiders to the system.

This led to the semi-miraculous Modesto March, itself a repeat of the Delano-to-Sacramento march from the 1960s. Starting as just a couple hundred marchers in San Francisco, the March swelled to as many as 15,000-strong by the time that it reached its objective at Modesto. This caused a sudden sea-change in the grape strike, bringing the growers and the Teamsters back to the table, and getting Jerry Brown and the state legislature to back passage of California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

This proved to be the high-water mark for the UFW, which swelled to a peak of 80,000 members. The problem was that the old problems within the UFW did not go away - victory in 1975 didn't stop Chavez and his Chicano constituency feuding with more distinctively Mexican groups within the movement over undocumented immigration, nor feuding with Filipino constituencies over a meeting with Ferdinand Marcos, and nor escalating these internal conflicts into a series of leadership purges.

Conclusion: Decline and Fall

At the same time, the new alliance with the Agricultural Labor Relations Board proved to be a difficult one for the UFW. While establishment of the agency proved to be a major boon for the UFW, which won most of the free elections under CALRA (all the while continuing to neglect the critical hiring hall issue), the state legislature badly underfunded ALRB, forcing the agency to temporarily shut down. The UFW responded by sponsoring Prop 14 in the 1976 elections to try to empower ALRB, and then got very badly beaten in that election cycle - and then, when Republican George Deukmejian was elected in 1983, the ALRB was largely defunded and unable to achieve its original elective goals.

In the wake of Deukmejian, the UFW went into terminal decline. Most of its best organizers had left or been purged in internal struggles, their contracts failed to succeed over the long run due to the hiring hall problem, and the union basically stopped organizing new members after 1986.

#history#u.s history#labor history#ufw#united farm workers#cesar chavez#dolores huerta#trade unions#social history#social movements#unions

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

Isn’t it just super fucking exhausting having morals and beliefs that are just completely at odds with the world around us? Like, I don’t think you’re wrong about the ads and stuff, even if I probably wouldn’t be strong enough to turn down YouTube ads if I was in that position or whatever. In my own line of work I’m constantly in conflict bc the prevailing ethic is “nothing says we have to help this person, so we won’t” where to me, “nothing says we can’t help this person, so we must” is the obvious moral imperative. Feels bad, man!

an aspect of mexican american history my father made a point to impress on me was that boycotts work when people are motivated to act against injustice. companies will be forced to bend the knee but it requires patience, temperance, and a willingness to go without and be uncomfortable for an unknown amount of time. the delano grape strike took 5 years of non stop fighting and sacrifice from the people who had the most to lose.

you are doing the right thing. if nothing else it's insanely mentally destructive to talk to people who act like the cenobites all day and act confused when you're disgusted. my family participated in a lot of boycotts/strikes/labor negotiations/caucusing so losing access to something or losing a level of comfort or sacrificing some time to a cause (even a kid they had me stuffing envelopes lol) was not only normal but expected.

i mostly feel very lonely.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Importance of Filipino Stories: Celebrating Filipino American History Month

October is Filipino American History Month. With more than 4.2 million individuals of Filipino descent here in the U.S., we know there are at least 4.2 million stories to cherish and celebrate! Today’s story comes from Josie Gepulle, our fall 2022 Editorial intern and proud Filipino American.

It wasn’t until I was in my second year of college that I got my first reading assignment on Filipino American stories.

At my university, I was taking a history course entitled “American Radicals and Reformers.” Halfway through the semester, I learned about Larry Itilong, a Filipino migrant laborer who went on to lead the five-year Delano Grape Strike in California and later co-founded the United Farm Workers of America.

I’m pretty sure my jaw actually dropped hearing about this. An actual Filipino American made his way into the history books, one who had a profound impact on the labor movement.

That’s also when it really hit me: there was a lack of Filipino stories in my life.

I grew up in a small suburban Texas town. I was the first and only Filipino my community saw, so I don’t really blame anyone for their ignorance. It was frustrating, however, to receive several comments like, “Are you sure you’re Asian? You don’t look like it at all.” or “Where is the Philippines anyway?” I didn’t understand at that time because I’m proud of my heritage, but what does that mean to a world that doesn’t even know you exist? The most recognition I’ve gotten is from veterans recalling war buddies or travelers who visited Manila once.

I learned the history of the Philippines from my dad, not school. The Philippines, it seems, had no place in the story of America, despite being one of its former colonies. Even the mainstream media barely acknowledged our culture and our community. Any reference to the Philippines seemed to only refer to Manila and how the language was Tagalog. I couldn’t relate to that. My parents are from Bacolod, a city in central Philippines, where the community spoke Illongo. The narrative America wanted to tell about the Philippines, as limited as it was, was not one I could fit into.

It took me a long time to identify as a Pinoy writer. That same year at college when I learned about Larry Itliong, I attended a special event where I heard Jose Antonio Vargas, the famed journalist and immigration rights activist, and openly undocumented Filipino American, give a talk about his book, Dear America: Notes from an Undocumented Citizen. He, too, was a storyteller and writer, just like I wanted to be.

I finally realized I wasn’t alone. I didn’t need to be the author who put the Philippines in the history book. Several writers already did that for me. Carlos Bulosan wrote the famous America Is in the Heart, establishing the Filipino American perspective in literature. Then there are the writers of today, like Elaine Castillo with her book America Is Not the Heart, a clear callback to Bulosan. While Filipino Americans may have different interpretations of their identities, these stories are very much in dialogue with each other.

Each story, including mine, is only a small piece in a much larger puzzle. My own perspective that only represents a tiny fraction of Filipino history. The Philippines is made up of 7000+ islands and has 120+ spoken languages. We have our own history and mythology that existed long before the Americans came and long before the first colonizers, the Spaniards, arrived as well. While colonialism has tried time and time again to erase our stories, remembering our traditions and history is how they live on. We don’t want these stories to become forgotten simply because they’re left out of school curriculums.

However, I do have to take a moment to be grateful for virtual spaces, especially those for writers. While my family is no longer the only Filipino family in my city, it was online where I met my very first Pinoy friends. Together, we traded experiences, laughing at the little tics that our families share. That, too, is an important part of the story. My friends and I aren’t famous, but aren’t those cherished moments together part of our experience as well?

And well, NaNoWriMo is the perfect time to explore your own stories, isn’t it? I remember being drawn to the challenge a long time ago, when I was a tiny middle schooler who felt so lonely in the giant world. NaNo made me believe that my story truly mattered, not just to everyone in the Philippines and America, but to me, the person who all my writing is eventually for. There’s no way I, or anyone for that matter, can accurately describe the story of every single Filipino, let alone Filipino American, out there. But you can talk about your story. Personally, I want to write characters who speak Ilonggo or grew up the only Filipino in their class. Maybe your characters will speak Cebuano or Ilocano. No matter what, Pinoys will get to be main characters! They’ll have grand adventures or share quiet moments with their loved ones. We’ll share our culture, our heritage with the world.

Together, our story will be told. Dungan ta sulat!

Josie Gepulle is a longtime NaNoWriMo fan, spending her teenage years lurking on the YWP forums and procrastinating her novel writing. She loves hearing the unique stories that come from writers all over the world and believes every voice is worth listening to. She enjoys the many different forms storytelling comes in, doing everything from analyzing TV shows to drawing her favorite characters. She can be found scribbling notes or doodling with an array of pens by her side.

If you’d like to learn more about Filipino American History Month, here are some more sites to explore.

10 Ways to Celebrate Filipino American History Month

National Today

Filipino American National Historical Society

FAHM Resources and Creators to learn from (IG Post)

#nanowrimo#writing#amwriting#filipino american history month#inspiration#by nano intern#josie gepulle#motivation

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

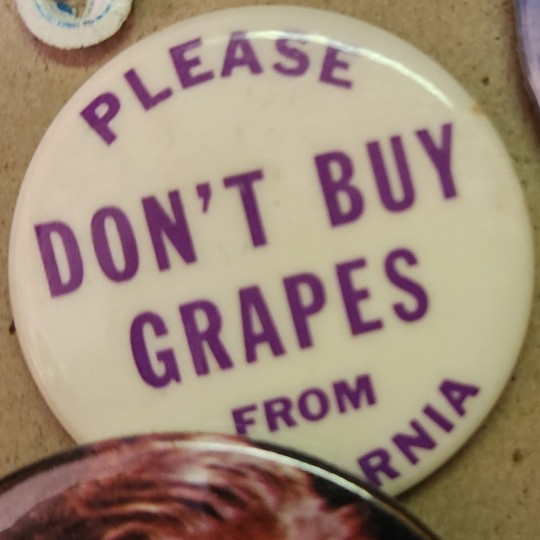

Over the long weekend my Dad had some pins and buttons from his collection that he was going through. Mostly from Toronto in the 70's, specifically the comic book and sci-fi scene.

This is a bit older, of course. My grandfather's Little Orphan Annie decoder ring. Not sure if Ovaltine was involved.

This is part of boycott efforts in relation to the the 5 year long Delano grape strike! I love how polite it was in contrast to the dire circumstances that the agricultural workers found themselves in.

These? I just think they're neat!

#Toronto#vintage#70s#science fiction#comic books#star trek#strike#howard the duck#vintage Toronto#pins#buttons

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Covering topics as diverse as the role of Chinese workers in the construction of the Western railroads; the leadership of Filipinos in the Delano, California, grape strike (1965-1970); and the gendered nature of anti-Asian immigration legislation, Choy’s work treats history not as an artifact of the past but as an urgent source of knowledge—and empathy—for the present."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

everything is raising my blood pressure today and if i see one more repost about the women’s “strike” over the holiday weekend so help me…

this is not sustainable activism. three days of not spending or otherwise withholding your labor, especially when you likely spent a lot to get through said strike, will do nothing for anyone. the money is spent and no one is the wiser of the boycott. it’s also incredibly privileged because a lot of people need to work to survive and cannot feasibly strike or boycott. also, who are we sticking it to? the patriarchy? capitalism? direct action means just that - directed toward someone, usually a company. but it has to be to something with a clear outcome.

successful boycotts often go on for YEARS (see: delano grape strike, 1965-1970), and are backed by a union or several unions. “solidarity forever” isn’t just a catchy slogan but means action is backed by money, bargaining, community, and a clear goal. also, always, ALWAYS ask, “who is pushing this action? is there an organization behind this? if so, which one? are they credible or established in this organizing space?” there are other ways to protest but boycotts are what i’m seeing people initially jump to.

i am not an experienced organizer. i studied social movements as an anthropology/sociology major and have volunteered for some political campaigns (canvassing, mostly), so i have an idea of what historically and also practically works in building a movement. i will be looking to the folks who have been doing this work and asking how i can help. if you want to do the same, find established, local organizations. it will take research and i can’t make it any easier than acknowledging that.

#this post brought to you by me angrily scrolling through a local fb reproductive rights group discussion#this reminds me when i lost my shit over the black profile pics on social media#and I argued with several friends about why it wasn’t helpful#when an action centers YOU it is not building anything#also spoiler but talking to people is what it boils down to#it takes people to change people’s minds#maria blabs

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dolores Huerta by Allison Adams

"We must use our lives to make the world a better place to live, not just to acquire things. That is what we are put on the earth for."

Dolores Clara Fernández Huerta (born April 10, 1930) is an American labor leader and civil rights activist who, with Cesar Chavez, is a co-founder of the United Farmworkers Association, which later merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee to become the United Farm Workers (UFW). Huerta helped organize the Delano grape strike in 1965 in California and was the lead negotiator in the workers' contract that was created after the strike.

#dolores huerta#allison adams#civil rights#activism#activists#ufw#workers rights#female portrait#herstory#women in history#irl women/girls

1 note

·

View note

Text

I will literally never shut up about Larry Itliong: I'm thinking about taking a scholarship exam on unions/worker's rights and can you believe this is what the study guide has to say about Delano

You can literally see the holes where the Filipinos have been omitted -- why did the National Farm Workers Association change its name? The closest Filipinos get to acknowledgement is technically counting as "Latinx" in the second screenshot.

People have rewritten the Delano Grape Strike so hard, and for what purpose? We can't have any Asian Americans who aren't model minorities, can't remove wedge of a myth diving us? Mexican farm workers fit the American collective racial imagination so well we can't see anything else? So it seems people have conceived this history to perfectly align with the stereotypes they already have...

The Delano Grape Strike was started by Filipinos. Larry Itliong led the Agricultural Workers' Organizing Committee along with many other Filipino activists. Delano was Filipino/Mexican solidarity -- workers from Asia and workers from Latin America joining union forces and succeeding. Remember this, forever and ever.

#unions#union history#labor movement#I said this#history#racism#filipino#latine#image undescribed#larry itliong#delano grape strike

1 note

·

View note

Text

"This, rather, is the fasting that I wish:"

Let me share to day's lenten adventure. Today is a the first Friday in Lent and I went to visit my mother at her memory care. I was invited to have lunch with her. I asked for the fish order for us. The staff came in with two beef and bacon meals and apologized that they ran out of fish. My mother already forgot that it was lent, her only concern was that I eat with her. I made a moral decision to go ahead, accept and eat the meal with her. No sooner did we take our first bite of the bacon when we felt a rumbling underneath us. A fiery hole opened up next two us, we felt a surge of heat but since my mother does not like the cold this made her very comfortable and we continued our meal. Four tortured souls however emerged and dragged us into the fiery depth below, luckily they brough the food plates with us so we could continue eating and offending God with this diabolical action.

Well, alright, so this did not happen. The incident of the meal did take place and I did make a moral decision, my mother ate with great satisfaction that her son enjoyed a meal with her and afterwards we took a nice walk. I created this story for two reasons: first, to share with you how creatively twisted my mind can get, and second, to highlight a powerful scriptural reading from today. In today's first reading we hear from the prophet Isaiah 58: 1-9a. In this reading God responds to the complaining Isrealites who religiously fast and do penance and yet do not get their prayers answered. The complained could very well be heard today. The response from God is very simple. Fast and penance are not meant to be empty religious rituals, they were meant to guide us towards social justice. If that was the case God would be with us, but as we continue to allow and even promote injustices then we our prayers, fast and penance are hallow. The words from Isaiah say it best:

This, rather, is the fasting that I wish:

releasing those bound unjustly,

untying the thongs of the yoke;

Setting free the oppressed,

breaking every yoke;

Sharing your bread with the hungry,

sheltering the oppressed and the homeless;

Clothing the naked when you see them,

and not turning your back on your own.

Then your light shall break forth like the dawn,

and your wound shall quickly be healed;

Prayer, Fast and Charity are beautiful aspects of a Catholic's lenten tradition. But it is never meant to be an empty ritual. If the purpose of not eating meat on friday is to enjoy a fish fry then go off and eat a steak because that type of fasting is meaningless. St. John Chrysostom tells us that the purpose of a fast is to make us better people for one another, not to check off some ritual obligation.

Don’t say to me: “I have fasted for so many days! I have not eaten! I have not drunk wine! I have gone without bathing!” Show me instead that, being wrathful, you became meek; and being cruel, you became compassionate to your fellow man. If you are intoxicated with wrath, to what end do you afflict your flesh? If you are filled with envy and covetousness, what benefit is there in drinking only water? I am not concerned with what is on your table, but whether your evil disposition has been transformed.

We have great models who have shown us that fasting and penance can become transformative elements from both personal and social sins. Cesar Chavez, for example, is a modern day saint for having fought for the rights of migrant farmworkers. As a Catholic he would engage in prayer and fasting in order to change economic policies and promote the rights of workers. Here he is with Bobby Kennedy ending his fast during the Delano Grape Strike of 1968.

This is the type of fasting that God is asking us to do. To transform ourselves to be better people and to challenge the social injustices that we face. This is the type of prayers and fasting that God will respond to.

0 notes

Text

Happy birthday, Dolores Huerta! (April 10, 1930)

A cofounder and longtime leader, alongside Cesar Chavez, of the United Farm Workers union, Dolores Huerta was born in Dawson, New Mexico to a Mexican immigrant family. Her father was involved in labor organizing efforts and later served in the New Mexico legislature, but Huerta was primarily raised by her mother in Stockton, California. Huerta became an activist from a young age, and helped to organize the Stockton chapter of the Community Service Organization. Huerta also became active in labor organization, and became acquainted with Chavez through their shared efforts to improve the conditions faced by farm workers. Huerta's organizational skills were instrumental in the UFW's early growth, and she played an important role in coordinating the UFW's national boycott during the Delano grape strike. A feminist, Huerta has also been active in efforts for women's rights as well as the rights of LGBT people, emphasizing intersectionality in struggle. Her birthday is a statewide holiday in California.

“Every single day we sit down to eat, breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and at our table we have food that was planted, picked, or harvested by a farm worker. Why is it that the people who do the most sacred work in our nation are the most oppressed, the most exploited?”

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strikes for Change

By: Jacob Chauvin

Ethnic Studies as we know, can be a sensitive topic to discuss with some, but gives us the cold hard truth about how our country started with diversity, and how we deal with diversity today. Diversity today, is what separates the U.S., from neighboring countries with its unique views, religious practices, and ethnic cultural values. But what did it take to get us to where we are today? Did it take bills? Laws? Amendments? Treaties? All of those are true, but it came down to each ethnic group’s cohesion and strikes to get each distinguishable movement sparked and ignited. The history of ethnic strikes is so important that we understand because it is within these strikes that made everything possible today, for the ethnic groups that battled poverty, discrimination, and social injustices based solely on their appearance and background.

San Francisco State College Strike

It was November 6, 1968, and few would know that this would mark the first day of the longest student strike in American history. Student leaders that attended San Francisco State College Third World Liberation Front marched with their demands for an education more relevant and accessible to their communities (African American, Asian American, Chicano, Latino, and Native American). This was a five-month long battle that engaged all parties involved in the school, police, and even politicians. Stemming from the original basic rights, protestors moved on to demand power and self-determination. The State resisted of course, but that didn’t stop the activists and they held strong. Though this movement didn’t change any economic or political structure, they strongly affected popular ideology and social relations. They also resulted in the formation of mass organizations and produced a cadre of activists who would continue to pursue their ideals.

BSU organizing protests to create equal learning opportunities.

Delano Grape Strike

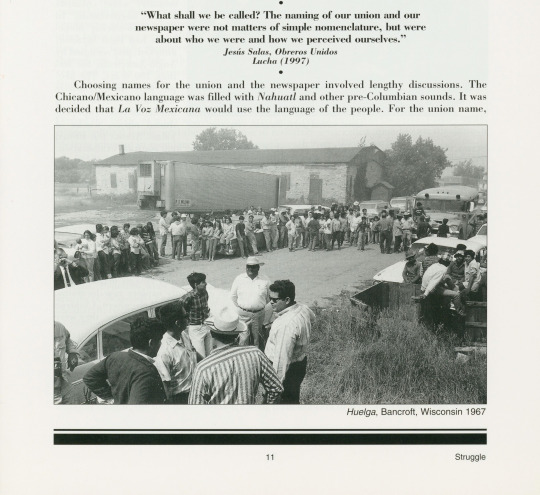

Not all strikes though, however, were at institutions for education. Strikes were also formed for the ways of Filipino workers and Mexican American workers to get better working conditions in California. One is the Delano Grape Strike, which would change the course for immigrant workers who had to work in intense conditions just so grape farmers can meet the demands of the world. On September 19, 1965, at 430 am in Delano California, 200 Filipinos and Mexicans stood below the NFWA (National Farm Workers Association) offices, holding signs inscribed with one word; “Huelga” (Strike). This strike lasted 5 long years, being disregarded by the Delano Chamber of Commoners. It was 1970 when that fight for the civil rights with Delano agricultural working communities was won. NFWA became a union, changing the name to United Farm Workers.

Delano Grape Strike led by Cesar Chavez and Larry Itilong.

Standing Rock and Alcatraz Strike

Another distinguishing strike was involving the Native Americans at Standing Rock, and Alcatraz. In April of 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux established the Sacred Stone protest camp at the confluence of the Cannonball and Missouri rivers in North Dakota. Companies began pipeline construction, and as a result, the Sioux began a protest because the pipeline’s draft environmental assessment did not address risks to their reservation’s water supply. Alcatraz is seen as a Historic Landmark and works with individuals and organizations to preserve and interpret its long history of activism.

Native American Tribes occupying Alcatraz Island

Conclusion...

Strikes are history, strikes are what bring cohesion and unity amongst the unique ethnic groups involved. It is a way for their voices to be heard in this ever-loud country we live in. Strikes are necessary because if a group does not strike, then how can we be heard?

LEARN MORE BELOW!

youtube

youtube

youtube

Sources:

Epstein, K. K., & Stringer, B. (2022). The Student Strike that Won Ethnic Studies and Black Student College Admissions. Journal of African American Studies, 26(4), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-022-09598-y

Contemporary Asian America. (n.d.). Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=0ygUCgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA25&dq=history+of+ethnic+study+strikes&ots=kTOQuCtrQ3&sig=3WdaRHhIg3m9AA20FDbLvEnIe1o#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20ethnic%20study%20strikes&f=false

Lambert, A. M. (2021). Cesar Chavez: The 1965 Grape Boycott and the 400-Mile Pilgrimage.

Beisaw, A. M., & Olin, G. E. (2020). From Alcatraz to Standing Rock: Archaeology and Contemporary Native American Protests (1969–Today). Historical Archaeology, 54(3), 537-555.

FUNG, C. (2014). “THIS ISN’T YOUR BATTLE OR YOUR LAND”: THE NATIVE AMERICAN OCCUPATION OF ALCATRAZ IN THE ASIAN-AMERICAN POLITICAL IMAGINATION. College Literature, 41(1), 149–173. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24544625

Tintiangco-Cubales, A., Kohli, R., Sacramento, J., Henning, N., Agarwal-Rangnath, R., & Sleeter, C. (2015). Toward an ethnic studies pedagogy: Implications for K-12 schools from the research. The Urban Review, 47, 104-125.

0 notes

Text

I'm just saying, whoever came up with the strike on Monday has no idea how strikes work. You don't put an end date on a strike until you have what you want. Going into Monday we all knew(those of us who even knew about the strike) knew it was only going to last one day, removing any pressure it may have generated. The Hollywood strikes lasted months. The Delano grape strike/boycott lasted FIVE YEARS. Yall ain't labor organizers you're tumblr users who know NOTHING

0 notes