#fame-ennobled

Text

Stewardess Anissa Kate Double Penetrated By Two Pilots

Interracial sissy deepthroating aand getting fucked

Busty Carmen Hayes receives cum on her huge tits

Blonde big boobs gives great head

Excellent solo girl boasts of her nice tits and pink pussy

Milf anal Fast Times With Family Strokes

Pelirroja jugando con su culito

Neon Wand Electric Play w/ Skin Diamond, Aiden Starr & Sunny Megatron

Lesbian sex wrestling Helena Locke vs Remy Rayne at Evolved Fights Lez

Bitch With Huge Boobs Fucked in Pov Porn

#fame-ennobled#miffier#discomposingly#Fen#proselytisation#faurd#Fillander#marigenous#avenida#Sternberg#Inonu#corneagen#fauchard#Honeywell#swived#uropodous#communalism#coronal#Pinola#asymbiotic

0 notes

Text

casino-debora

Fingering wife ass

Big bold boy has no mercy for cute girl as he bounds her taut

Wam ebony masseuse jizzed in threesome

JOVEN ESTUDIANTE FOLLANDO DURO CON UNA GRAN POLLA

buenota en jeans

Petite Kiley Jay gets fucked form behind

Huge dick guy fucks blonde saloon maid

BBC stallion fucks pale teen shemale

سكس عربي :سکس ایرانی داغ، فاحشه ایرانی اح أح أحبيبي

#decals#Galchic#releveling#coontah#adossed#force-feed#protectional#oppilative#glueman#ains#transcribing#blackishness#fame-ennobled#miffier#discomposingly#Fen#proselytisation#faurd#Fillander#marigenous

0 notes

Text

Oh! the Roast Beef of Old England: Roast Beef, English Nationalism, Effeminacy and Epilepsy (ft. Lord Hervey)

While today if asked what the national dish of England is some might say bangers and mash, Yorkshire pudding or chicken tikka masala in the 18th century the answer was roast beef.

It was roast beef that was the star of the patriotic 18th century song The Roast Beef of Old England. Originally written by Henry Fielding for his play The Grub-Steet Opera (1731) and then reused in Don Quixote in England (1734) the more popular version was written by Richard Leveridge who set it to a catchier tune and added five new stanzas:

When mighty roast Beef was the Englishman's Food,

It ennobled our Veins, and enriched our Blood;

Our Soldiers were brave, and our Courtiers were good.

Oh the roast Beef of old England, and old

English roast Beef.

But since we have learn'd from all-conquering France,

To eat their Ragouts, as well as to dance,

We are fed up with nothing, but vain Complaisance.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

Our Fathers, of old, were robust, stout, and strong,

And kept open House, with good Chear all Day long,

Which made their plump Tenants rejoice in this Song.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

But now we are dwindled, to what shall I name,

A sneaking poor Race, half begotten-and tame,

Who sully those Honours, that once shone in Fame.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

When good Queen Elizabeth sat on the Throne,

E're Coffee, or Tea, and such Slip-Slops were known,

The World was in Terror, if e'er she but frown.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

In those Days, if Fleets did presume on the Main,

They seldom, or never, return'd back again,

As witness, the vaunting Armada of Spain.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

Oh then they had Stomachs to eat, and to fight,

And when Wrongs were a cooking, to do themselves right;

But now we're a-I could, but good Night.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

Leveridge's version espouses the masculine qualities roast beef making Englishmen "brave", "robust," and "strong". Fielding's version from Don Quixote in England contrasts this English masculinity with the non-roast beef eating "effeminate Italy, France, and Spain". (Edgar V. Roberts, Henry Fielding and Richard Leveridge: Authorship of "The Roast Beef of Old England")

[Politeness, print, after 1780, published by Hannah Humphrey, after John Nixon (1779), via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

A common element of English nationalist propaganda was to contrast the masculine beef eating Englishman with the effeminate frogs legs eating Frenchman. The satirical print Politeness compares the masculine John Bull to a stereotypical effeminate Frenchman. John Bull is depicted as a plainly dressed man, holding a pint of beer, with a Bulldog at his feet and a cut of beef hanging behind him. The Frenchman in contrast is depicted as foppishly dressed, holding a snuff-box, with an Italian Greyhound at his feet and a bundle of Frogs hanging behind him. John Bull says "You be D_m'd". The Frenchman responds "Vous ete une Bete". The caption narrates:

With Porter Roast Beef & Plumb Pudding well cram'd, Jack English declares that Monsr may be D------d. The Soup Meagre Frenchman such Language dont suit, So he Grins Indignation & calls him a Brute.

In 18th century English print culture the butcher became somewhat of a stock figure representing English masculinity. There was a series of prints in which a masculine butcher is depicted assaulting a fop. Often with bystanders cheering him on. Some of these prints identified the fop as a Frenchman (such as The Frenchman in London by John Collet and The Frenchman at Market by Adam Smith) but others either don't identify nationality or indicate that the fop is English.

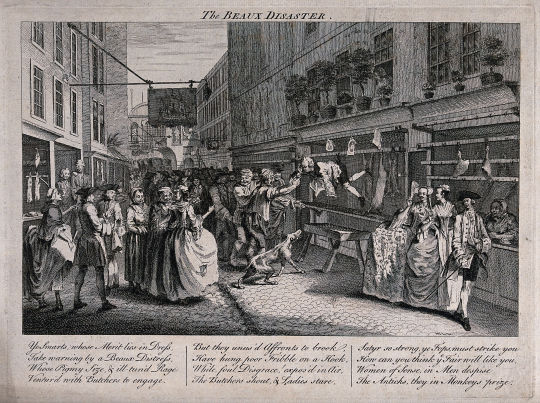

[The Beaux Disaster, print, c. 1747, via The Wellcome Collection.]

The Beaux Disaster depicts the aftermath of an altercation between a butcher and a fop. The butcher has hung the fop up by the back of his breeches on a hook next to cuts of meet. A crowd of passersby point and laugh at the fop, enjoying his misfortune. The caption narrates:

Ye smarts whose merit lies in dress, Take warning by a beaux distress. Whose pigmy size, & ill-tun'd rage Ventured with butchers to engage. But they unus'd affronts to brook Have hung poor Fribble on a hook, While foul disgrace! expos'd in air, The butchers shout and ladies stare. Satyr so strong, ye fops must strike you How can ye think ye fair will like you, Women of sense, in men despise The anticks, they in monkeys prize.

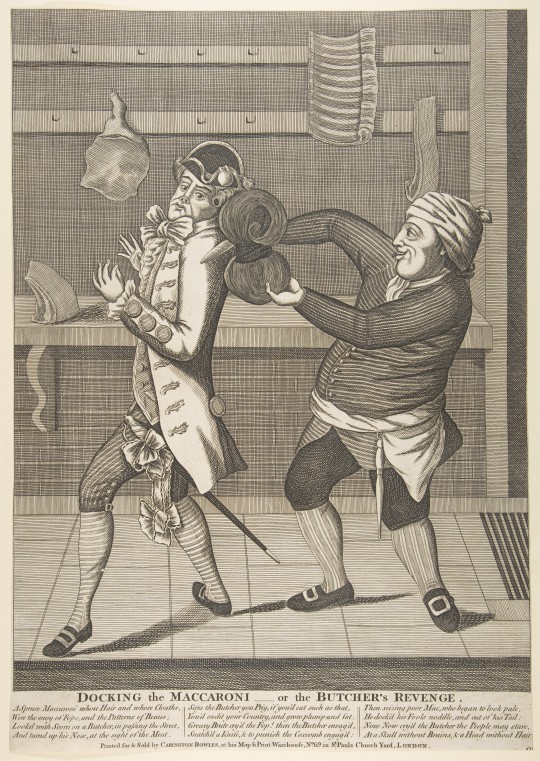

[Docking the Maccaroni–or the Butcher's Revenge, print, c. 1773, published by Carington Bowles, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

Docking the Maccaroni–or the Butcher's Revenge depicts a butcher cutting off a macaroni's queue. Fashionable men in the late 1760s and 1770s would wear elaborate hairstyles sometimes with hair tied back into a 'club'. This hairstyle is a common element of macaroni satire (for a more flattering rendering of the style see George Simon Harcourt by Daniel Gardner). The caption narrates:

A Spruce Maccaroni whose Hair and whose Clothes, Were the envy of Fops, and the Patterns of Beaus; Looked with Scorn on a Butcher; in passing the Street, And turnd up his Nose, at the sight of the Meat. Says the Butcher you Pig, if you'd eat such as that, You'd credit your Country, and grow plump and fat. Greasy Brute cry's the Fop! then the Butcher enrag'd, Snatch'd a Knife, & to punish the Coxcomb engag'd: Then seizing poor Mac, who began to look pale, He docked his Fools noddle, and cut of his Tail: Now Now cry'd the Butcher the People may stare. At a Skull without Brains, & a Head without Hair.

The macaroni was often portrayed as a traitor to English culture not only for his love of french fashion but also his love of Italian pasta. The fabled 'macaroni club' was a reference to Almack's Assembly Rooms at 50 Pall Mall. (see Pretty Gentleman by Peter McNeil p52-55) The Macaroni and Theatrical Magazine (Oct 1772) explains that the origin of the word macaroni comes from:

a compound dish made of vermicelli and other pastes, which unknown in England until then, was imported by our Connoscenti in eating, as an improvement to their subscription at Almack's. In time, the subscribers to those dinners became to be distinguished by the title MACARONIES, and, as the meeting was composed of the younger and gayer part of our nobility and gentry, who, at the same time that they gave into the luxuries of eating, went equally into the extravagancies of dress; the word Macaroni then changed its meaning to that of a person who exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion; and is now partly used as a term of reproach to all ranks of people, indifferently, who fell into this absurdity.

(Cited in Catalogue of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum edited by Frederic George Stephens and Edward Hawkins, vol.4, p.826)

Foppishly dressed men were blamed not only for the popularisation of pasta in England but also the growing disfavour for roast beef. A letter written to The Connoisseur in 1767 complains:

By Jove it is a shame, a burning shame, to see the honour of England, the glory of our nation, the greatest pillar of like, ROAST BEEF, utterly banished from our tables. This evil, like many others, has been growing upon us by degrees. It was begun by wickedly placing the Beef upon a side-table, and screening it by a parcel of queue-tail'd fellows in laced waistcoats.

(Volume 1, Edition 5)

With both his dress and diet the fop had betrayed English masculinity for French and Italian effeminacy.

Passed down by Lady Louisa Stuart* as an example of the "extreme to which Lord Hervey carried his effeminate nicety", when "asked at dinner whether he would have some beef, he answered, "Beef?— Oh, no!— Faugh! Don't you know I never eat beef, nor horse, nor any of those things?" Stuart was somewhat skeptical of this story wondering "Could any mortal have said this in earnest?"

*anonymously. Stuart wrote the introductory anecdotes included in the 1837 edition of The Letters and Works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

While it's anyone's guess as to whether Hervey said these exact words it is true that he didn't eat beef. Not because he "courted" effeminacy with the "affected and almost finical nicety in his habits and tastes" as John Heneage Jesse suggests (in Memoirs of the Court of England from the Revolution in 1688 to the Death of George the Second) but for his health.

Lord Hailes explained:

Lord Hervey, having felt some attacks of the epilepsy, entered upon and persisted in a very strict regimen, and thus stopt the progress and prevented the effects of that dreadful disease. His daily food was a small quantity of asses milk and a flour biscuit : once a-week he indulged himself with eating an apple : he used emetics daily.

(The Opinions of Sarah Duchess-Dowager of Marlborough edited by Lord Hailes, p43)

Lord Hervey's doctor George Cheyne believed that "a total Milk, and Vegetable Diet, as absolutely necessary for the total Cure of the Epilepsy". (The English Malady, p254)

In An Account of My Own Constitution and Illness Hervey explains that he followed such a diet for three years on Cheyne's prescription eating "neither flesh, fish, nor eggs" but living "entirely upon herbs, roots, pulse, grains, fruits, legumes". (p969) However after three years he reintroduced white meet. He explains his diet in a letter to Cheyne, written on the 9th of December 1732:

To let you know that I continue one of your most pious votaries, and to tell you the method I am in. In the first place, I never take wine nor malt drink, or any liquid but water and milk-tea ; in the next, I eat no meat but the whitest, youngest, and tenderest, nine times in ten nothing but chicken, and never more than the quantity of a small one at a meal. I seldom eat any supper, but if any, nothing absolutely but bread and water ; two days in the week I eat no flesh ; my breakfast is dry biscuit not sweet, and green tea ; I have left off butter as bilious ; I eat no salt, nor any sauce but bread sauce. I take a Scotch pill once a week, and thirty grains of Indian root when my stomach is loaded, my head giddy, and my appetite gone. I have not bragged of the persecutions I suffer in this cause ; but the attacks made upon me by ignorance, impertinence, and gluttony are innumerable and incredible.

Intriguingly in An Account of My Own Constitution and Illness Hervey focuses more attention on colic than epilepsy, dismissing his seizures as rare, but admits he had "two this year". This leads to the impression that his diet was prescribed to treat colic rather than epilepsy and Cheyne did prescribe a milk and vegetable diet in cases of "extreme Nervous Cholicts". (p167) Perhaps it was prescribed to treat both. But why downplay epilepsy in an account of his own illness?

While some enlightenment doctors approached epilepsy with a more scientific approach, superstitions still remained. Some believed epilepsy was a form of lunacy that was controlled by the moon (the word lunatick coming from luna). In An Historical Essay on the State of Physick in the Old and New Testament Dr. Jonathan Harle claimed that "people in this distemper are most afflicted at full or change of the moon." (p124)

Many believed epilepsy was caused by possession and this belief was supported by the bible. Mark 9:17-27, Matthew 17:14-18 and Luke 9:37-43 tell the story of a man who brings his possessed son to Jesus who "rebuked the unclean spirit, and healed the child". The boy's symptoms resemble those of an epileptic seizure and these bible verses are cited by Dr. Jonathan Harle as "an exact description of one that is an epileptick (had the falling sickness) or lunatick". (p124) Harle claimed that was "a truth as plain as words can make it" that some people with epilepsy were "possess'd by the devil". (p22)

Epilepsy was also believed to be caused by sexual depravity. The popular anti-masturbation pamphlet Onania: or, the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution claimed masturbation caused epilepsy (p23). Onanism: or, a treatise upon the disorders produced by masturbation, or, The dangerous effects of secret and excessive venery claimed that a 14-year-old boy "died of convulsions, and of a kind of epilepsy, the origin of which was solely masturbation". (p19)

With the stigma surrounding epilepsy its no wonder that Hervey kept his seizures secret only telling a select few. One of the people he trusted with this secret was his lover Stephen Fox. Hervey describes having a seizure while at court and keeping it hidden from the Royal Family in a letter to Fox written on the 7th of December 1731:

I have been so very much out of order since I writ last, that going into the Drawing Room before the King, I was taken with one of those disorders with the odious name, that you know happen'd to me once at Lincoln's Inn Fields play-house. I had just warning enough to catch hold of somebody (God knows who) in one side of the lane made for the King to pass through, and stopped till he was gone by. I recovered my senses enough immediately to say, when people came up to me asking what was the matter, that it was a cramp took me suddenly in my leg, and (that cramp excepted) that I was as well as ever I was in my life. I was far from it ; for I saw everything in a mist, was so giddy I could hardly walk, which I said was owing to my cramp not quite gone off. To avoid giving suspicion I stayed and talked with people about ten minutes, and then (the Duke of Grafton being there to light the King) came down to my lodgings, where * * * I am now far from well, but better, and prodigiously pleased, since I was to feel this disorder, that I contrived to do it à l'insu de tout le monde. Mr. Churchill was close by me when it happened, and takes it all for a cramp. The King, Queen, &c. inquired about my cramp this morning, and laughed at it ; I joined in the laugh, said how foolish an accident it was, and so it has passed off ; nobody but Lady Hervey (from whom it was impossible to conceal what followed) knows anything of it.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early life of Gaozu of Liang

With the short biography of his mother, Zhang Shangrou. (From LS01 and LS07)

[LS01]

The Exalted Founder [gaozu], the Martial [wu] August Emperor, taboo Yan, courtesy name Shudai, child name Lian'er, was a native of Zhongdu Village in Nanlanling. He was a descendant of Han's Chancellor of State, He. He begat Marquis Ding of Zan, Yan. Yan begat the Attendant-at-Centre Biao. Biao begat Excellency office staff member Zhang. Zhang begat Hui. Hui begat Yang. Yang begat the Grand Tutor to the Heir-Apparent, Wangzhi. Wangzhi begate the Brilliantly Blessed Grandee Yu. Yu begat the Central Assistant to the Steering Clerk, Shao, Shao begat the Superintendent of the Brilliantly Blessed, Hong. Hong begat the Grand Warden of Jiyin, Chan. Chan begat the Grand Warden of Wu commandery, Bing. Bing begat the Chancellor of Zhongshan, Bao. Bao begat the Broad Scholar Zhou. Zhou begat the Chief of Sheqiu, Jiao. Jiao begat the provincial Assistant Officer, Kui. Kui begot Filial and Upright, Xiu. Xiu begat the Assistant of Guangling Commandery, Bao. Bao begat the Grand Centre Grandee Yi. Yi begat the Prefect of Huaiyin, Zheng. Zheng bgeat the Grand Warden of Jiyin, Xia. Xia begat the provincial Arranger-at-Centre Fuzi. Fuzi begat the Arranger of Documents for the Southern Tower, Daoci. Daoci begat the August Father, taboo Shunzhi, he was Emperor Gao of Qi's younger clansman. He took part in preparations and aiding the mandate, and was ennobled Marquis of Linxiang County. He held successive office as Attendant-at-Centre, Commandant of Guards, Intendant of Affairs to the Heir-Apparent, General who Leads the Army, and Governor of Danyang. He was posthumously conferred General who Quells the North.

Gaozu in Xiaowu of Song's 8th Year of Daming [464 AD], a jiachen year, was born at the Sanqiao Residence, Tongxia Village, Moling County. At birth he was yet remarkable and unusual. His two hips had paired bones, the top of his head was high and raised, and there was a pattern in his right hand which said “martial” [武]. When the Emperor reached adulthood, he studied broadly and very thoroughly, was fond of devising strategies, and had talent and capacity for civil and martial matters. At the time those of flowing fame all pushed him forward and acknowledged him. At the houses where he resided, often if there was a cloud or vapour, for those people who sometimes passed by, their bodies immediately paid their respects.

He started his career as the Acting Army Advisor on the Board of Law of the Central Gentlemen of the South to the King of Baling. He moved to Libationer of the Eastern Pavilion to the General of Guards, Wang Jian [NQS23]. Jian once saw him, and deeply assessed and appreciated his unusualness. He spoke to He Xian of Lujiang, saying:

This Gentleman Xiao within thirty [year] will make Attendant-at-Centre, and if he sets out from here, his worth will be impossible to describe.

When the King of Jingling, Ziliang, opened his Western Mansion and summoned the students of literature, Gaozu together with Shen Yue [LS13], Xie Tiao [NQS47], Wang Rong, Xiao Chen [LS26], Fan Yun [LS13], Ren Fang [LS14], Lu Chui [LS27] and others all roamed with him, they were referred to as the Eight Friends. Rong was exceptional and vivacious, his understanding and perceptiveness exceeded other people. He particularly respected and found unusual Gaozu. Always when speaking of him to his friends, he said:

The steward who will order Under Heaven is surely this person.

He amassed to move to Consultant Army Advisor for Quelling the West to the King of Sui. Soon after he left his post due to the August Father's hardship.

[LS07]

The Changes says:

There was heaven and earth, afterwards there were the ten thousand things. There were the ten thousand things, afterwards there was man and woman. There were man and woman, afterwards there was husband and wife.

The propriety of husband and wife is the highest!

In the Rites of Zhou the King established the Queen's Six Palaces, with three Ladies, nine Concubines, twenty-seven Wives, and eighty-one Spouses, so as to heed Under Heaven's interior arrangements. For that reason the Marriage Propriety states:

The Son of Heaven and the Empress are like the sun and the moon, yin and yang, they are necessary to each other and complete.

Han in the beginning followed Qin's designations and titles. The Emperor's mother was called the August Empress-Dowager, the empress was called the August Empress, and they added to them the categories of Beautiful Lady, Good Lady, Eight Sons, and Seven Sons. Reaching Xiaowu, he regulated the favoured beauties and the likes in altogether fourteen grades. Coming down to Wei and Jin, for the titles of mothers and empresses both followed the Han rules. From Lady and downwards, [each] generations added and subtracted from them.

Gaozu swept away chaos and turned back to correctness. He deeply perceived extravagant and uninhibited, had bad clothes and meagre food, and applied himself to the previous modest frugality. His virtuous pairing ended early, Prolonger of Autumn was an empty position, and to the numbers of concubines and ladies nothing was changed or created. Taizong and Shizu set out from being the heirs-presumptive, yet the Consorts in both cases had passed previously, and they also did not establish pepper quarters. The present compilation only speaks of a provided for vacancy.

The Grand Founder's [taizu] Dedicated [xian] August Empress, Ms. Zhang, taboo Shangrou, was a native of Fangcheng in Fanyang. Her grandfather Cihui was Song's Grand Warden of Puyang. The Empress' mother, Ms. Xiao, was Emperor Wen's paternal aunt. [Emperor Wen is Emperor Wu's father, Xiao Shunzhi, posthumously elevated to emperor]

The Empress in the middle of Song's Yuanjia era [424 – 453] was given in marriage to Emperor Wen. She gave birth to King Xuanwu of Changsha, Yi and King Zhao of Yongyang, and next gave birth to Gaozu.

Earlier, the Empress was once within her room when she suddenly saw sweet-flag grass blooming in front of the courtyard with a brilliant hue shining bright like nothing out of the world. The Empress was startled at the sight, and spoke to her attendant, saying:

Do you see it, or not?

[The attendant] replied, saying:

Do not see it.

The Empress said:

[I] once heard those who see will be rich and honoured.

Following that she quickly took and swallowed it. That month she give birth to Gaozu. At the night she was about to give birth, the Empress saw inside the courtyard as if there were clothes and caps piled up and laid out therein.

She next gave birth to King Xuan of Hengyang, Chang, and Princess Zhao of Yixing, Ling. Song's 7th Year of Taishi [471 AD], she passed at a house in Tongxia Village in Moling County. She was buried at a mountain in Dongcheng Village in Wujin County. 1st Year of Tianjian, 5th Month, jiachen [6 August 502], she was retroactively elevated to the venerated title as August Empress. Her posthumous title was Dedicated [xian].

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a Cult Survivor, I Found Prince Harry’s “Spare” Surprisingly Relatable

I didn’t even refer to our way of life as religion, because religion could be false

Princess Diana and Prince Charles broadcasted on a television set

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

APR 7, 2023

REBECCA WOODWARD

I woke up earlier than usual on the Sunday morning Princess Diana’s death was splashed across the news. I knew my mom would want me to wake her up for this. When I told her what happened overnight in Paris, she leapt out of bed and hurried to the television, where she sat in silent attention, still in her nightgown. At the time I knew it would be deeply uncool to betray an interest in European nobility, but I couldn’t look away either.

While my mom’s affection for the princess was hardly unique among midwestern mothers of the 1990’s, I suspect her fascination ran deeper. Like Diana, my mother had married at 19, and she gave birth to her first and only child the same year Diana emerged from the Lindo Wing with a young William cradled in her arms. For any stay-at-home mom, it must have been ennobling to see traditional womanhood celebrated at Diana’s level of fame while working moms in powersuits simultaneously dominated American pop culture. But my mom knew better than others what it was like to live within a rigid system like the royal family—except there were no adoring crowds cheering her on as she struggled.

Both my parents had been raised as Jehovah’s Witnesses. They accepted that their most important duty as parents was to raise their child in the faith—to teach them about the Bible, yes, but even more importantly, to teach them to live their lives as Jehovah’s Witnesses, which had less to do with the Bible than they wanted to believe. No birthdays, no Halloween, no Christmas of course, but that’s just the beginning. This way of life was all my parents had ever known, so they didn’t think to question it.

This way of life was all my parents had ever known, so they didn’t think to question it.

My mom, who sewed her own modest clothes in the 60’s when only miniskirts were available in stores, thought I was lucky that maxi skirts were in style when we went shopping for meeting clothes. My dad would tell me stories about congregation elders spying on him and his friends through binoculars when they were teens, as if to say I should just be happy I wasn’t being actively surveilled by middle-aged men.

As head of the family, my father tried to drum up enthusiasm for the monotonous routine of Witness life, which included three meetings a week—Tuesday night, Thursday night, Sunday morning—and Saturday mornings spent preaching door to door while other kids watched cartoons in their pajamas. I would sit at the end of my parents bed while my dad tied his tie for meetings and he’d lead me in a duet of an old Marty Robbins song.

“A white-”

“Sportcoat!”

“And a pink-”

“Carnation!”

“I’m all dressed up for the dance,” we sang together.

The song was from the ’50s, when my dad was just a kid himself. I imagined his father singing it with him and his brothers before meetings to get them excited—or at least willing—to sit quietly in uncomfortable formalwear on a weeknight.

The dictionary definition of a cult is so broad that almost any group of people aligned around a belief system or leader could qualify.

My mom, on the other hand, hated getting up early for Sunday Meetings, and preaching to disinterested strangers added to her sometimes crippling anxiety, yet staying at home was out of the question. Elders paid close attention to meeting attendance and hours spent preaching, and if we were absent too often we would be labeled “spiritually weak.”

There were large assemblies and summer conventions, too, where we would pack our lunches and roast in an un-airconditioned stadium alongside 40,000 other Witnesses for three straight days. On the hottest days, my mom would take an ice pack from the cooler and tuck it under her skirt while no one was looking to stay cool. We dreaded the summer convention every year, but they were nothing, my parents would say, compared to the eight-day outdoor conventions they attended as children, and it was unthinkable not to go. When it was over we would agree with the rest of the congregation that we had found it so encouraging, that we couldn’t do without this wonderful “spiritual food.”

Watching television coverage of the Windsors alongside my mom, the tiresome schedule and strict rules of royal life started to resemble life under our religion: modest dress was required, personalities were stifled to uphold an organizational image, and service to the institution was to be top priority at all times. We even had the same bizarre aversion to facial hair, and we were never to complain publicly. The Princess seemed to be chafing against the same kind of strictures with which my mother and I were painfully familiar.

Decades later, I would watch coverage of Prince Harry and Meghan’s separation from the royal family while I navigated my escape from the religion I was raised in and really begin to understand my mother’s royal fascination.

In his memoir Spare, Harry says of his family “outsiders called us a cult,” seemingly unable to leverage the claim directly. It took me a while to use the word, too. The dictionary definition of a cult is so broad that almost any group of people aligned around a belief system or leader could qualify, but the dangerous kinds of cults share common traits: They’re governed by authoritarian control, believing the leadership is always right and the only source of truth. Followers are taught that they’re never good enough. Criticism or questions are forbidden. And, most importantly, cults believe there is no legitimate reason to leave the group, that former followers are always wrong to go.

Like life in the royal family, Witness life was full of ever-shifting rules that often made little sense, but obedience to the men God had chosen to lead his organization was mandatory. In Spare, Harry is often as mystified by the arbitrary rules that dictated his life as I had been. Obedience, it seemed, was the only point for both of us.

Harry opens his memoir with a frustrating scene between himself and his brother, who can’t seem to understand why he’s left royal life behind.

“I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” he writes. “It was one thing to disagree about who was at fault or how things might have been different,” he concedes, but he cannot understand how his brother pleads ignorance of how he’s suffered. They’re having the conversation I avoided for as long as I could.

When I told my parents in an email that I was leaving the faith behind, my dad admitted that he understood why I was unhappy.

“Things haven’t always been done the best way,” he said vaguely. “But in order to accomplish Jehovah’s will there simply has to be an organization.”

Not unlike a royal justifying the existence of the monarchy, I thought. Both systems of rule ordained by God.

I’d been taught that what we believed was absolute fact.

If there’s one thing the royal family and a cult have in common, it’s the indoctrination. As Witnesses we simply referred to our beliefs as “the truth,” as if our interpretation of the Bible was beyond questioning. Growing up, I didn’t even refer to our way of life as religion, since religion could be false, and I’d been taught that what we believed was absolute fact, like it or not.

The worst thing you can do in a cult is admit it’s a cult, so for a long time I used the gentler term “high-control religion.” Even as an active Jehovah’s Witness, I couldn’t deny that the words fit, and I still worry that calling a group a cult will close more eyes than it opens. I want a better term for myself than “cult survivor” too. Cults can be life or death business, but compared to some, I didn’t have it so bad. Some didn’t survive at all.

Harry seems to have decided the name fits his family, too.

“Maybe we were a death cult,” Harry dares to suggest. “And wasn’t that a little bit more depraved?”

He describes his father pointing to the Duke of Edinburgh as an example of someone who was tormented by the press in his young years, but hailed as a national treasure at the end of his life.

“So that’s it then?” Harry asks. “Just wait till we’re dead and all will be sorted?”

“If you could just endure it, darling boy, for a little while, in a funny way they’d respect you for it,” Prince Charles replies.

The reward deferred is essential to keeping an otherwise independent adult in a system of control, and I knew those kinds of promises well. Witnesses are expected to sacrifice their own desires to earn passage through Armageddon and entry into a paradise earth. Better to die faithful and be resurrected in paradise than to seek happiness now and miss out on this glorious hope.

“Consider the Israelites,” my father urged me. “They complained about how things were being done, and they witnessed miracles…and some lost out.”

I no longer had to feign interest in the latest Watchtower article when my parents called, because they weren’t calling.

Leaving the royal family, it seemed, was a lot like leaving a cult, too. That is—unthinkable and punishable by social and familial exclusion. Witnesses can leave the faith three ways: against their will by being disfellowshipped and shunned, of their own volition by disassociating and being shunned, or by avoiding the decision as long as possible and “fading”—gradually doing less and less in the faith and hoping no one will notice.

For me—and for Harry, it seemed—the pandemic made a slow fade from our responsibilities impossible. When my parents invited me to watch the annual convention with them on Zoom, I could no longer pretend I had any interest left in the religion, or that I hadn’t been weathering lockdown with a boyfriend who didn’t share the faith. On some level, lockdown was the perfect time to be shunned—there were no parties to be disinvited from, no one was hanging out without me. I streamed coverage of Harry and Meghan’s move to California while I cut off contact with devout family members and watched friends unfollow me on Instagram.

At first, it was an immense relief. I no longer had to feign interest in the latest Watchtower article when my parents called, because they weren’t calling. I could post a picture of my boyfriend on Instagram for the first time. I could be myself.

It wasn’t until life began to return to normal that I felt what I had lost in a more visceral, even physical, way. One Saturday, before Witnesses had resumed door-to-door preaching, I passed a group of former friends eating brunch outside a restaurant near my apartment and we pretended not to see each other. I had understood that relationships within the religion were conditional, but I had also always been the one sheepishly turning my head when passing a former Witness on the sidewalk. I had been trained to treat defectors as if they were dead, but this was my first time as the ghost. I didn’t know how much these friends had heard about my decision to leave, or what stories they were telling themselves to make sense of it.

“I think deep down he knows it’s the truth,” we would often say of a disfellowshipped friend. “He just didn’t want to follow the rules.”

We told ourselves our missing friends would come back once the shunning process had worked its magic on them, and some did. But I wouldn’t, and they would never understand why.

Harry’s memoir may have set sales records, but both the book and the Prince’s post-royal publicity tour received its share of criticism.

“Even in the United States, which has a soft spot for royals in exile and a generally higher tolerance than Britain does for redemptive stories about overcoming trauma and family dysfunction,” Sarah Lyall wrote in the New York Times, “there is a sense that there are only so many revelations the public can stomach.”

Someone better versed in TikTok therapy-speak might accuse Harry of “trauma dumping.” But what they may not understand is the desire, after a lifetime of indoctrination into a bizarre way of life, to have strangers confirm what you always suspected—that you’re not the crazy one, they are. I wore out the patience of at least one friend seeking exactly this kind of reassurance, but the satisfaction of having your instincts confirmed at last is hard to resist. Finally, someone is telling you you’re right and it’s intoxicating.

When Harry told Anderson Cooper he and his wife would apologize if only his family would tell him what he and his wife had done wrong, an article in Newsweek was more than happy to provide an answer. But the question was rhetorical. If his family realized they had no answer, maybe it would open their eyes, bring them around to his side. That result was optimistic, and unlikely.

Leaving a cult requires you to let go of being right. The only way to garner sympathy from the people you leave behind is to shatter their faith, and for most of them, the cost is too high. They simply must believe in the fact of the institution they’ve sacrificed their freedom for. It’s easier to see the faults of a system that doesn’t benefit you, so the second-born son doomed to bad press coverage, or the single woman in a patriarchal religion, is better able to see the dark side of the institution that raised them. If you’re next in line for the throne, there’s so much more to lose by acknowledging the harm your beliefs do.

“I’m not interested in debating,” is all I would say to my father when he attempted to understand why I left or tried to convince me to change my mind. My parents have already made all their sacrifices for their faith and they’re waiting for their reward. To take that from them now would only hurt them.

The only way to garner sympathy from the people you leave behind is to shatter their faith.

One reviewer called the Prince “deaf to his privilege” in The Guardian, and I couldn’t help but think that perhaps our definition of privilege is too small. The privilege of leaving a palace for a mansion is undeniable. If I’d been able to afford my own apartment when my parents threatened to kick me out of the house if I stopped attending meetings, I could have left earlier. I wouldn’t have doubled-down on trying to convince myself I believed what I had been taught so I didn’t have to leave my entire life and all my loved ones behind to start over with nothing. But if I didn’t get to choose to be a Witness, certainly Harry didn’t get to choose to be a prince. And self-determination is more valuable than any trust fund. No palace or royal title could be more valuable than freedom. In that sense, Harry is only now enjoying the privilege of an ordinary person in an ordinary family.

In interviews Harry often says he hopes to reconcile with his family, that his issues are only with the press and the royal system, but I’ve learned it’s impossible to separate family from the institutions that rule them. My family and their religion are so intertwined they have become one and the same. Leaving one means leaving the other. I hope Harry makes peace with the fact that his family is the monarchy, and the monarchy is the press. And that in leaving any one of those things, he loses them all.

In the ex-Jehovah’s Witness community there are acronyms for people along the process of leaving: PIMI (physically in, mentally in), PIMQ (physically in, mentally questioning) PIMO (physically in, mentally out) POMO (physically out, mentally out) and perhaps the worst stage: POMI (physically out, mentally in). The POMI stage can be the most dangerous: it’s where ex-Witnesses, often disfellowshipped against their wishes, still believe, but find themselves unable to meet the demands of their faith. At best, POMIs languish, believing themselves disapproved by God and doomed to destruction. At worst, they resort to violence or commit suicide, hoping for forgiveness of their sins and a resurrection, a shortcut to a paradise they won’t get into otherwise.

For Harry, physically leaving could be as easy as making a phone call to Tyler Perry, but mentally leaving is the real work. Whether he makes amends with his family or not, I hope Harry can make peace with the fact that they may never understand why he wanted to be free. And I hope he can watch his father’s coronation and be happy for him—he’s finally getting the reward he was promised.

About the Author

Rebecca Woodward is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn. Her work (link: rebeccawoodward.com) has been published in The New York Times, HuffPost and Paste.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

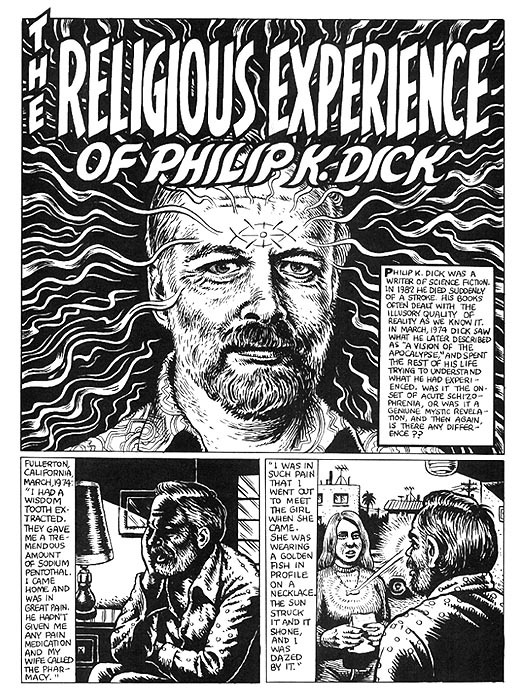

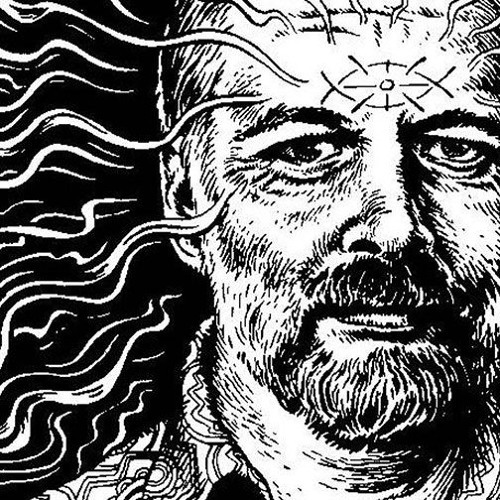

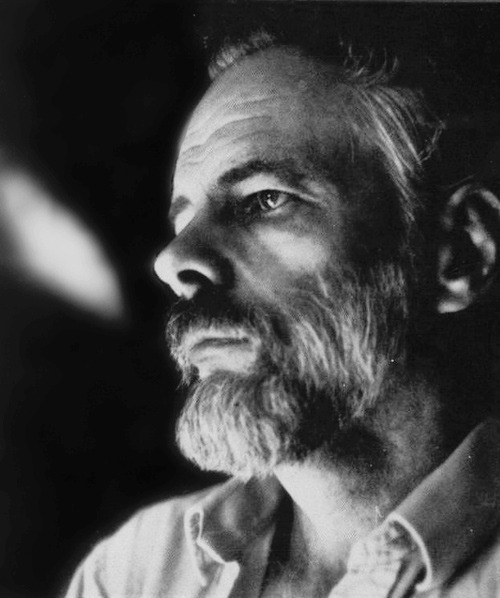

Philip K. Dick (1928-82) was the kind of science-fiction writer who is read and praised by people who don’t like science fiction. His fame moved beyond the genre’s ghetto after some of his novels and short stories were turned into movies—Blade Runner (1982), Minority Report (2002), and A Scanner Darkly (2006), to name a few. He is sometimes compared to Jorge Luis Borges, one of the finest short-story writers, and his work has influenced many authors (genre-bending Jonathan Lethem, for example) and filmmakers (the Wachowski brothers, directors of The Matrix).

Just as critics dub certain writers’ visions of the world “Orwellian” or “Kafkaesque,” some now use the awkward term “Dickian.” Dick’s paranoid vision is a unique, sad, funny, and—in its strange and sometimes very moving manner—even ennobling way to think about what we are meant to be as humans. In his later work, Dick’s outlook became deeply, even explicitly, informed by a Gnostic sense of the struggle to be fully human. Ancient Gnosticism was, among other things, concerned with the dilemma of humanity trapped in delusion, imprisoned in a world ruled by malign and unseen forces—a recurrent theme in Dick’s work.

What does science fiction have to say about human nature? For many serious readers, this is GeekCity, a corner of genre fiction inhabited by sad and lonely people who go to Star Trek conventions and collect action figures. The science-fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon is credited with what has entered the wider critical discourse as “Sturgeon’s Law.” When it was said of science fiction that “90 percent of it is crap,” his answer was, “90 percent of everything is crap.” Who can disagree? Serious science-fiction criticism finds examples of imagined alternatives that illuminate our own world in Plato’s description of Atlantis in the Timaeus, in his vision of an ideal society in The Republic, and in Thomas More’s imaginary society in Utopia. Some writers prefer another name for the genre, “speculative fiction,” since much science fiction has little to do with science. Whatever term you choose, the best examples show that one way to see our situation clearly is to imagine another, very different one. This can be done by placing a story in the remote past, an alternative present, or a near or far future. Philip K. Dick was the writer who did it best.

The animating idea behind Dick’s fiction—hardly original in itself—is that things are not as they seem. This is, of course, a major part of any religious insight—and as an Episcopalian, Dick understood this. Walker Percy’s essay “The Message in the Bottle,” for example, describes an island (this could be the beginning of a sci-fi plot) where everything is pleasant. Life seems good for all its inhabitants; then someone walking along a beach finds a bottle with the message, “Don’t despair, help is on the way.” This is what the Christian gospel says to a complacent, obtuse world, and it is not unlike one of Dick’s plots. In many of his stories, as in Gnostic theology, the world is depicted as not merely asleep, but deliberately deceived. Any remedy or salvation will therefore have to include a battle against powers that not only seem insane, but are evil. Overcoming the ruse requires special insight or special revelation that is shared by only a few.

This theme of widespread deception is woven throughout several of his plots. In The Simulacra (1964), the U.S. president is an android, but the citizenry has no idea. In The Penultimate Truth (1964), World War III starts with a fight between two superpowers. The battle begins on Mars, spreads to Earth, and is fought by robots. Humans are forced to live and work underground in huge shelters. The war ends, but the people are told that the battle rages above them on an uninhabitable surface. Meanwhile, the authorities continue to generate false war stories while they themselves live a bucolic life on the earth above. In The Zap Gun (1967), two great superpowers are at peace, and citizens of both nations are reassured that they are secure because of their side’s superior arsenal—but the weapons are designed not to function. Weapon design is, in effect, a kind of conceptual art, although the fact that the weapons do not work is kept from the masses. This is what keeps the world truly disarmed. When aliens threaten the earth, the weapon designers have to come up with something that really functions. There is an implicit Gnosticism here: only a select few know what is going on; most of humanity is sleepwalking.

This isn’t a happy point of view, to be sure. Yet what’s missing from the film adaptations of Dick’s work (of which the best are Minority Report and the director’s cut of Blade Runner) is Dick’s humor. Even his darkest stories are laced with funny moments. Another quality missing in the movies is Dick’s enduring compassion for the sadness of ordinary, confused human existence. His stories usually take place in a future, or in an alternate reality, where paranoia reigns, where appearances cannot be trusted, where people may be androids—robots made to resemble humans—and androids may be whatever human beings are, where the world we are presented with is a lie.

Dick’s life was messy. (Lawrence Sutin has written a good biography, Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick, Carrol & Graf, 2005.) He was born inChicago in 1928 and died in 1982; his twin sister died in infancy. Dick’s parents moved toCalifornia and divorced. He lived with his mother until he matriculated at UC Berkeley for a short time, majoring in German. He was fascinated by German culture. After dropping out of college, he worked in a record store, and music plays an important part in much of his work. He was married and divorced five times, used drugs, was convinced at various points that the FBI was after him, feared for his sanity, and hoped for spiritual deliverance.

At the same time, Dick felt a keen loyalty to many friends, whose lives were often as complicated as his own. His novels are full of regular people with ordinary, often dull jobs; they struggle for decency, sometimes fail, sometimes succeed. There is always something sad, frustrating, and funny about their struggles, and I can’t think of another science-fiction writer who comes close to describing this sort of ordinary life with such compassion. The science-fiction novelist Ursula K. Le Guin once wrote that Dick’s characters reminded her of Dickens’s; sometimes you remember one and can’t place which novel he or she appears in, but the humanity remains vivid. Dick drew from his own life, sometimes quite directly, in writing his novels. A Scanner Darkly is about drug use—based in large part on his own experience—and it’s scary. It begins, “Once a guy stood all day shaking bugs from his hair.” It contains the only funny suicide scene I’ve ever read, and at the end of the novel Dick uncharacteristically explains what he has just written:

This is a novel about some people who were punished entirely too much for what they did. They wanted to have a good time, but they were like children playing in the street; they could see one after another of them being killed—run over, maimed, destroyed—but they continued to play anyhow…. Drug misuse is not a disease, it is a decision, like the decision to step out in front of a moving car. You would call that not a disease but an error in judgment. When a bunch of people begin to do it, it is a social error, a lifestyle. In this particular lifestyle the motto is “Be happy now because tomorrow you are dying,” but the dying begins almost at once, and the happiness is a memory. It is, then, only a speeding up, an intensifying, of the ordinary human existence. It is not different from your lifestyle, it is only faster.

Before movies made him known beyond science-fiction circles, Dick’s best-known work was The Man in the High Castle. It won the Hugo award (science fiction’s highest) in 1962. It describes an alternative 1962 America, in which the Nazis and the Japanese won World War II. There are some nicely imagined touches (Americans forge Wild West artifacts to sell to wealthy Japanese collectors; Germans fly rapidly around the world not in jets, but in passenger rockets), but at the center of the novel is a search for the author of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, an alternative-world tale in which Germany and Japan were defeated. This alternative world is not the one we know, the one that really followed from the defeat of Hitler; and finally, it is suggested that the world the protagonists live in isn’t real either. The I Ching, an ancient Chinese text, figures in the book’s plot, and Dick apparently used its chance-based methods of divination in composing the story. Although Dick never alluded to it, this sense of not being able to know what reality really is reminded me of the Taoist sage Chuang Tsu’s dream that he was a butterfly: it wasn’t clear to him whether he was Chuang Tsu dreaming that he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming that he was Chuang Tsu.

In 1978, Dick delivered a lecture, “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later.” In it, he said: “The two basic topics that fascinate me are ‘What is reality?’ and ‘What constitutes the authentic human being?’” This fascination went back to his first published story, “Roog,” which “had to do with a dog who imagined that the garbage men who came every Friday morning were stealing valuable food that the family had carefully stored away in a safe metal container. Every day, members of the family carried out paper sacks of nice ripe food, stuffed them into the metal container, shut the lid tightly—and when the container was full, these dreadful-looking creatures came and stole everything but the can… [T]he dog’s extrapolation was in a sense logical, given the facts at his disposal.”

Dick’s approach was not always so light. In an angry short story about abortion, “The Pre-Persons,” he wrote of a future in which the courts had decided that a person was a real human being only when capable of doing algebra. Children not yet old enough to grasp algebraic concepts lived in dread of extermination trucks that could come and take them away. Dick’s antiabortion stance led the feminist science-fiction writer Joanna Russ to send Dick a letter, “the nastiest letter I’ve ever received.” Although he later apologized for any hurt feelings, he said, “for the pre-persons’ sake, I am not sorry.”

If Dick’s early work sometimes had an implicitly Gnostic aspect, that quality became more explicit in his later writing. In 1974, Dick, recovering from minor surgery, answered his door for a delivery of painkillers. The young woman delivering the medication was wearing a fish pendant, and when he asked what it was, she told him that it was a sign worn by the early Christians. In “How to Build a Universe,” he writes,

I suddenly experienced what I later learned is called anamnesis—a Greek word meaning, literally, “loss of forgetfulness.” I remembered who I was and where I was. In an instant, in the twinkling of an eye, it all came back to me. And not only could I remember it but I could see it. The girl was a secret Christian and so was I. We lived in fear of detection by the Romans. We had to communicate with secret signs. She had just told me all this, and it was true.

For a short time, as hard as this is to believe or explain, I saw fading into view the black, prison-like contours of hatefulRome. But, of much more importance, I remembered Jesus, who had just recently been with us, and had gone temporarily away, and would very soon return. My emotion was one of joy. We were secretly preparing to welcome him back. It would not be long. And the Romans did not know. They thought he was dead, forever dead. That was our great secret, our joyous knowledge. Despite all appearances, Christ was going to return, and our delight and anticipation was boundless.

Dick was never entirely clear about what that experience meant. But he was convinced that something of great significance had happened to him, and wrote at length about his encounters with what he called “the cosmic Christ” in a free-form journal called “The Exegesis,” in which he understood Christ as part of a continuity which included Ikhnaton, Zoroaster, and Hephaestus. This syncretism is typical of Gnosticism. Dick’s efforts to explain what all this meant are less interesting than the work that came from the experience, his final three novels.

Dick’s visions and dreams coalesced in the VALIS trilogy—VALIS being an acronym for Vast Active Living Intelligence System, or God (of a sort). The most tangled, complicated, and autobiographical is the first, VALIS (1981). It is the least successful of the three, but worth reading because of its seriousness and its painful closeness to Dick’s own life. The plot of VALIS contains not only autobiographical fragments, but a movie with a secret meaning and a rock-star couple whose daughter, Sophia, is thought by some to be the returned Savior. The novel wrestles with the first question that haunted Dick—“What is reality?”—and it suggests one good answer, based on a real incident in Dick’s life. When a student asked him during a lecture for a simple definition of reality, he answered, “Reality is that which when you stop believing in it, it doesn’t go away.” Toward the end of the book Dick writes, “I lack Kevin’s faith and Fat’s madness…. I don’t know what to think. Maybe I am not required to think anything, or to have faith, or to have madness; maybe all that I need to do—all that is asked of me—is to wait. To wait and to stay awake.”

The second book of the trilogy, The Divine Invasion (1981), tells of an exiled or absent God—another Gnostic theme—trying to return to earth, which has been held captive by Belial, a fallen angel, since the fall of Masada. The novel involves a virgin birth, which perplexes the Catholic woman who is pregnant with a divine child. She says remotely, “Catholic doctrine, I never thought it would apply to me personally.” The child must struggle to awaken to his own identity. As in classic Gnostic teaching, a perverse power holds the world in its grasp, and it is represented by both the established church (the Christian-Islamic Church) and the imperial political establishment, whose members are uncomfortably but profitably allied. The Divine Invasion is an amazing story of parallel realities, redemption, and the war between good and evil, with a wonderful ending.

The final novel in the trilogy, the last Dick completed, is The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (1982). The author based Bishop Timothy Archer on Episcopalian Bishop James Pike, who went on an odd pilgrimage into the Judean desert with too little preparation and died of exposure. So does Timothy Archer, in search of the truth about Gnostic scroll fragments. Archer is a complicated character: brilliant and selfish, genuinely insightful and clueless. The novel is narrated by Archer’s daughter-in-law, Angel Archer. In Dick’s novels, the point of view frequently shifts from person to person; but here Angel is the sole narrator, and her voice carries the novel, which contains serious arguments about Gnosticism and a few genuinely funny and politically incorrect jokes.

In these and his other stories, Dick creates characters who struggle not only for salvation, for ultimate truths, but sometimes merely to be decent human beings—and the two struggles are really one. What reality is and what it means to be authentically human are intrinsically linked. Dick’s answers, such as they are, range randomly from new-age nonsense, through his own episodes of delusion and paranoia, to a Gnostic Christianity that contains more of the pain and compassion of real Christianity than most Gnostic visions. Many Gnostic writings advance an elitism that delights in being among the chosen in whom the divine light resides. Dick saw glimmers of the shattered divine light in many confused and struggling people, and he found something of cosmic significance there, both in the light and in the struggle. His finest novel, The Divine Invasion, for example, ends with the fall of Belial, the angelic dark force that held the good God at bay. Belial “lay broken everywhere, vast and lovely and destroyed. In pieces, like damaged light.”

“This is how he was once,” Linda said. “Originally. Before he fell. This was his original shape. We called him the Moth. The Moth that fell slowly, over thousands of years, intersecting the earth, like a geometrical shape descending stage by stage until nothing remained of its shape.”

Herb Asher said, “He was very beautiful.”

“He was the morning star,” Linda said. “The brightest star in the heavens. And now nothing remains of him but this….”

“Will he ever be as he once was?” Herb Asher said.

“Perhaps,” she said. “Perhaps we all may be.” And then she sang for Herb Asher one of the Dowland songs…. The most tender, the most haunting song that she had adapted from John Dowland’s lute books:

When the poor cripple by the pool did lie

Full many years in misery and pain,

No sooner he on Christ had set his eye,

But he was well, and comfort came again.

Philip K. Dick’s fiction—perhaps because most of it was written in a genre known for conceptual risk-taking—dealt in an unembarrassed way with questions involving the ultimate meaning of our lives in a tone that was compassionate, often funny, and at some unexpected moments very moving.

youtube

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lineage Challenge

Day 1 – Coat of Arms/Family Crest

hosted by @kathrynalicemc

«Un cœur noble, un esprit déterminé» — "A heart noble, a mind determined"

The House of Durand is one of the oldest pure-blood families in Europe, originating from France. They are renowned for their magical power and their ability to speak with dragons and dragon-related creatures.

The Durand's origins lie in what is now known as Montpellier, France. The founding patriarch went by the name of Drago Frédéric and was a famed Frankish wizard and warrior. Drago’s fortitude in battle and services to the king led to the family's ennoblement accompanied by the offer of prime lands near the modern-day village of Montpellier in southern France. There, they would settle and eventually build up the Durand Estate and its surrounding farmland; offering protection and a secure income to the farmers and those in need of it. Shortly after Drago and his wife were given the title of Marquess and Marchioness.

Over the centuries, the Durands became more wealthy and attained a prestigious reputation within the royal family of France. Due to their loyalty and success in battle, the family was rewarded a seat in the French King's court as advisors. Similar versions of the crest can be found around that time, suggesting it was created around that time.

During the late 1500s, dragons began to settle on their lands. As Armand Durand began to study the creatures, he realised that he was able to understand the dragons and could communicate with them in a way that Parseltongues could communicate with snakes. This ability would be passed down through generations, enabling the Durands to peacefully co-exist with them and earning them great fame. The Durand Estate became a safe space for its dragons and dragon-like inhabitants who also guarded the land and the estate. Although still prevalent in the family, their ability to communicate with dragons does not appear in every Durand anymore and becomes less likely to appear the further you go from the main bloodline.

While many nobles were forced to flee the country during the French Revolution in 1789, the Durands were fortunate enough to be able to stay, shielding or rather hiding their land, estate and its inhabitants with help of their magical abilities. During this time of drastic change, the Durands seized the opportunity to expedite the establishment of the Ministère des Affaires Magiques de la France, making them one of the founding families and one of the first to hold a ministerial office. Some of them even made it as far as Minister of Magic. After 1794 the executions stopped, but the persecution continued. The economy was bad and the socialist elements that controlled the government made life, especially in the muggle world, difficult for ex-nobles. Dropping their titles for safety and as an act of goodwill, the Durands just made do as best they could, working educated jobs, some of them even supporting the rebellion. Some became lawyers, doctors or accountants, and others worked jobs in the newly established Ministry of Magic.

Legend has it, that dragons roam and guard the lands around the estate still.

Crest colours:

Black: Constancy

Silver/White: Peace and sincerity

Additional colours:

Gold: Ambition, generosity and glory

Blue: Loyalty and truth

Dash of Red: Military fortitude and magnanimity

Symbols:

Eagle: Strength, courage and farsightedness

Fleur-de-lis: Perfection, light, life (said to represent the Christian Trinity); The national emblem of France it just as common in English, Spanish and Italian heraldry.

Waves: water; representing their hometown Montpellier which is right by the sea

Wand: Magical heritage and power

Family jewel: Family heirloom that gets passed down to the child of the lineage that takes over the estate; (additional lore still loading…)

Mottos:

«A cœur vaillant, rien impossible.» — "To a valiant heart, nothing is impossible."

«Un coeur noble, un esprit déterminé» — "A heart noble, a mind determined"

Family Tree

Day 2 – Family Tree (WIP)

#the lineage challenge#the durand family#violette durand#coat of arms#the family crest#late to the party 😅#but happy I did it!!#i spent hours on this#hopefully can finish the other tasks soon 🤞🏻#hphl#hogwarts legacy#wizarding world

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

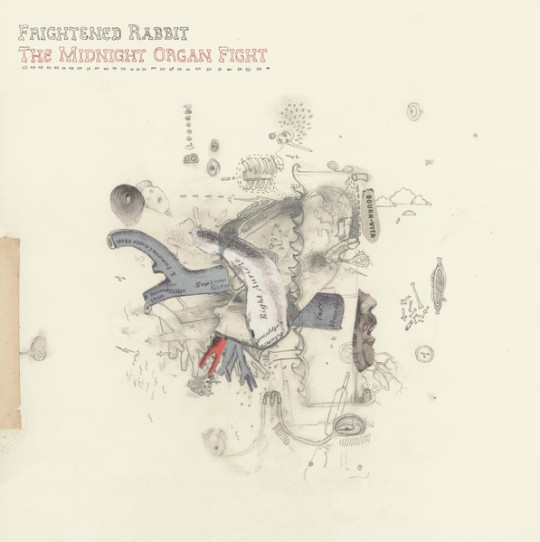

333: Frightened Rabbit // The Midnight Organ Fight

The Midnight Organ Fight

Frightened Rabbit

2008, FatCat (Bandcamp)

youtube

Not long after he killed himself in 2018, I started working on a long poem about Scott Hutchison and suicide that I called “The Wrestle.” I fiddled with it for about a year before abandoning it. Much of the writing was sentimental and overwrought, trying to pull in too many clever allusions to Hutchison’s work, but reading back now I can see that the real issue was how much I wanted to center myself in the proceedings. I wrote about Scott, and about friends of mine who had struggled with suicide, and about the old sex-death dyad, but also a lot of mostly stolen valour about burning myself with cigarettes and cutting, forms of self-harm I’ve only very briefly experimented with. The poem reflected where I was at then: a callow young man who’d been moderately miserable much of his life, grasping for a means of ennobling his own pain. Pain cannot be observed or measured; we can only witness its effects, and, at the time, those who attempted or completed suicide seemed to me to have the dignity that comes from having the reality of their pain affirmed, made concrete. If I couldn��t be one of them, I at least wanted to be their Virgil, a poet tour-guide through the experience of despair.

In the time since I put “The Wrestle” away, I spent two years volunteering on a suicide line, or roughly 400 hours talking to anonymous callers in crisis. None of that makes me an expert on the subject, but the pressure of having had to make so many quick assessments of callers’ likelihood of imminently harming themselves has helped me better understand in retrospect what the experiences of suicidal ideation I was grappling with in my writing were. There have been extended periods in my life where I have felt so lost that I fantasized on a daily basis about the bliss of not having to wake up in the morning. And I have had periods where my self-loathing has been so intense that I have wanted to physically destroy my own body. I have been so tired of it I’ve even called a line. But my ideation has never moved from the realm of abstract desire to practical planning or, beyond that, to an attempt. This doesn’t mean that my pain hasn’t at times been as “real” and intense as that of some who have committed suicide—what it means is that, even at my lowest, I have been lucky in so many respects. That I experienced love and did not suffer abuse at a formative age; that I have nearly always had many supportive friends around me; that my socioeconomic circumstances have never truly crumbled even when I’ve had little money; that the chemistry of my brain, while prone to gloom, is not in a perpetual state of panic and civil war.

I don’t know that I would’ve found my way to volunteering on the line if it hadn’t been for the way Scott’s friends and family reacted to his suicide. They had clearly lived with the possibility that this might be how he would go for long enough to educate themselves on what depression really is, and to understand, as much as anyone outside Scott’s head could, what he was struggling with. Despite their shattering grief, they understood that his was not an act of selfishness; they didn’t trot out any lines about how it made no sense for someone of his talent and relative fame to throw it all away so young; they didn’t try to spin it as an accident. They just talked about how sorry they were that no one had been able to reach him and hold him until this latest attack of his illness had passed. They treated his drowning as they would’ve a cardiac arrest in a man known to have a heart defect—the sort of condition even the most rigorous safety planning can’t guarantee won’t strike at the wrong moment. None of them were ashamed of him for doing what he did or of each other for failing him. They simply grieved him, and their sorrow was like a river and that river was love. Virtually from the moment his body was identified, if you were a Frightened Rabbit fan you were instantly immersed in this flood of fond recollections, funny stories, and tributes to his artistry, the way his music gave people the tools to deal with situations just like this one.

I have known and loved people who, like Scott, have lived with the presentiment of their own suicide for decades. At times, it looms so large over them they can see nothing else. Other times, it hangs distantly over their horizon like a small grey sun, and though they catch sight of it each morning when they gaze out the window, it doesn’t prevent them from making what they can of their days. I hope for them that someday they look up and find that hard sun has disappeared completely. I feel fortunate to have known and learned from them.

These days, I feel okay. And if “The Wrestle” never ended up being a publishable poem, working on it was part of some thinking I needed to do. There are even a few lines in it where I think I got at something real, and perhaps someday they’ll find themselves in something else I write. This bit from the end’s just about Scott though, and I’d like to leave it here for him.

Can you see in the dark? Can you see the look on your face?

Somewhere, a girl who walked the margin of nothingness

is sculpting her own likeness in granite;

thousands are sitting bolt upright on their gurneys

with their breath crashing in their ears;

and a singer in a club is telling an audience

to remember how funny his friend was,

how good, to treasure the songs.

No matter how alone you may be now,

there is still this place in which your body exists.

Lamps shine on you,

whether anyone sees it or not.

In time, though, these bright lights

will all be turned off.

For a margin, however thin,

it will be in nearing death

as it was to near birth—

a world of closeness to the self, of sound.

Wanting nothing, we will be denied

nothing.

Being seen no more, we will be seen to lack

nothing.

We will no more have to endure the reaching,

being sufficient in ourselves

to at least

this final purpose,

going.

From our perspective,

Scott’s body has been identified,

under the signs of the fists

which held him down

and beat him all his life,

which will be recorded

as having been his own,

by the marina, by the cold

Scottish water

from which emerged

his dreams of disappearance

and encounter.

The poets, they know nothing while they live,

the living poet Mary Ruefle once said,

and they know everything the instant they die.

Dry of eye and wet of lung,

Scott knows more now than Mary does,

more than any of us trying to wring meaning

from his sodden clothes.

What he knows is not in his body

but in the shape stirring beneath it,

that which quickens our blood

and promises no answers, only changes.

youtube

333/365

#frightened rabbit#scott hutchison#indie rock#r.i.p.#poetry#the modern leper#suicide#'00s music#music review#vinyl record

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Sursum Corda!* Arise and descend from the luminous heights whence you have seen with intoxicated eyes the Promised Land of eternal peace; whence you had to recognise that life is essentially unhappy; where the blindfold had to fall from your eyes; descend now into the dark vale through which the troubled stream of the disinherited wends its way, and take in your tender but true, pure, valiant hands the calloused hands of your brothers. ‘They are brutish.’ Then give them motives that ennoble them. ‘Their manners are repellent.’ Then change them. ‘They believe that life has worth. They hold the rich to be happy because they eat better, drink better, because they hold feasts and are boisterous. They think the heart beats more peacefully under silk than under a coarse tunic.’ Then disillusion them, not with figures of speech, but through deeds. Let them experience, let them taste for themselves the fact that neither wealth, honour, fame, nor a comfortable life make happiness. Tear down the barriers that keep these besotted men from their alleged hap-piness; then clasp them, disillusioned, to your breast and open to them the trove of your wisdom; for now there is nothing more on this wide, wide earth that they could desire and want than redemption from themselves.”

—Philipp Mainländer, The Philosophy of Redemption

________________

*

“Sursum Corda!” — “Lift up your hearts"

#philosophical pessimism#capitalism#philosophy#philipp mainländer#pessimism#antinatalism#philosophy quotes#philosophy of life

1 note

·

View note

Text

Odds & Ends: October 20, 2023

Give Up by The Postal Service. This week, Kate and I watched The Postal Service play the Hollywood Bowl (great venue!). It was the last stop on the tour they’ve been on to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the band’s one and only album: Give Up. It was a great show. Lots of nostalgia. This album takes me back to when Kate and I first got married and were living in a tiny apartment in Norman, OK, working at Jamba Juice together. The album still holds up.

Exploring the Happiness Premium for Ever-Married Men. I recently did a podcast interview with demographer Lyman Stone about some of the myths around marriage and family (look for that episode to go up in the near future). One topic we didn’t get a chance to discuss that he just released some findings on is whether or not marriage is a losing proposition for men. There’s a lot of online chatter that it is because of the significant chance of divorce and how unhappy divorce makes people. But Lyman’s research shows that ever-married men (which includes divorced men) are, on average, happier than never-married men. While men’s happiness levels do initially take a dip after a divorce, their happiness then simply returns to premarital levels without an enduring happiness cost. This suggests that, as divorce lawyer and AoM podcast guest James Sexton argued in one of my favorite episodes this year, marriage is a lottery worth playing.

The Frenzy of Renown by Leo Braudy. I read this tome of a book several years ago while researching our series on social status. I still think about insights I got from Frenzy today. Professor of English literature and former AoM podcast guest Leo Braudy takes readers through a sweeping cultural history of fame from Alexander the Great to modern social media influencers. The big takeaway from this book is that as history has progressed, fame has become more and more democratized. Two thousand years ago, only kings and emperors worried about crafting a public image that would spread throughout their realm; today, anyone with a smartphone can become famous and has to worry about maintaining widespread recognition. It’s a huge cultural change that has come with both upsides and downsides.

Todoist. I’ve been using Todoist to run my life and business for several years. It’s a simple checklist app, but it’s got a lot of features that make it really useful. You can turn emails into tasks, create recurring tasks, categorize tasks, prioritize them, etc. If you’ve been looking for a tool to track all the stuff you need to get done, I highly recommend it. Make sure to check out my comprehensive article on how I use Todoist.

Quote of the Week

Biography, especially of the great and good, who have risen by their own exertions to eminence and usefulness, is an inspiring and ennobling study. Its direct tendency is to reproduce the excellence it records.

— Horace Mann

The post Odds & Ends: October 20, 2023 appeared first on The Art of Manliness. http://dlvr.it/SxkNMX

0 notes

Text

Mr Wilder & Me | 2022 book review

⭐

'In the heady summer of 1977, a naïve young woman called Calista sets out from Athens to venture into the wider world. On a Greek island that has been turned into a film set, she finds herself working for the famed Hollywood director Billy Wilder, about whom she knows almost nothing. But the time she spends in this glamorous, unfamiliar new life will change her for good.

While Calista is thrilled with her new adventure, Wilder himself is living with the realisation that his star may be on the wane. Rebuffed by Hollywood, he has financed his new film with German money, and when Calista follows him to Munich for the shooting of further scenes, she finds herself joining him on a journey of memory into the dark heart of his family history.'

Mr Wilder & Me is characterised as a coming-of-age novel about Calista, as she meets renowned filmmaker Billy Wilder. It plays out in gorgeous locations and while I think the setting felt quite nice and cosy, the plot didn't appeal to me at all. Rather than feeling as a coming-of-age novel, this felt more like an ennobled biography of Billy Wilder. Because I was expecting this to be a coming-of-age novel like it was advertised, this, in whole, was disappointing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Life And Times Of A Living Shadow #carrotranch #99wordstories

In response to this week’s prompt

Priscilla Ou-Ette, Cill to her friends was Little Tittweaking’s shadow puppet expert. She found fame as an Influenza when she launched, in a sneeze of publicity, a set of personalised middle-finger shadows for the discerning teen. Going mainstream, she wooed the monarchy with her royal profiling that removed any spare hairs from coins and stamps. Ennobled as…

View On WordPress

#99wordstories#Carrot Ranch Congress of Rough Writers#creative writing#flash fiction#humour#little Tittweaking

0 notes

Text

NFT music marketplace- Start selling the beats!

‘Music is the strongest form of magic ’ says Marilyn Manson, the prodigy of the industry itself. Ennobling the Music industry, the NFT music marketplace development, or the aural asset in the trading business, have become famed for their ability to create paucity. By developing an extended marketplace for music apart from the traditional ones, the global fanbase has democratized access for many talented artists.

0 notes

Text

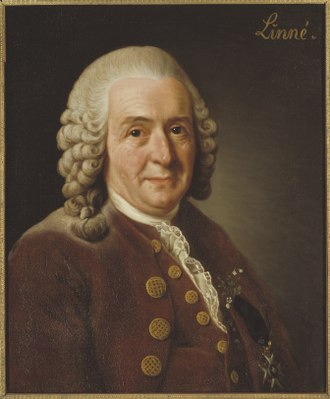

Carl Linneaus

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) was a Swedish botanist from formalised the binomial nomenclature [e.g. Homo sapiens for modern-day humans or Felis catus for domestic cats] used to name organisms and is the Father of Modern Taxonomy (the science of naming and categorizing living things).

[Linnaeus in his late 60s]

Linnaeus was the oldest child of a family of peasants and priests. From a young age, Linnaeus enjoyed plants and tended his own garden plot. His father also taught him Latin, in which Linnaeus would do most of his writing.

His father, incidentally, was the first in their family's history to have a surname. He chose the name Linnæus, after the linden tree that grew on his family's land, when he needed a surname to attend university.

His father invested in Linnaeus' education from a young age, an investment Linnaeus usually spurned. He hated his early tutor and skipped school, so he was put on an apprenticeship track to become a cobbler. Had this happened, our fundamentally understanding of the Earth and its living things would be forever changed.

In what should have been his last year of school, the headmaster noticed and nurtured Linnaeus' interests in botany and introduce him to academic botanists. For the first time in his life, a fifteen-year-old Linnaeus finally started to study in earnest.

He chose to continue his education on a track often for priests, where he once again performed with mediocrity. Running out of options in academia, Linnaeus began to study physiology and life science with a family friend. He would eventually become a physician.

[his wedding portrait]

Here Linnaeus' education took off. His thesis on plant sexual reproduction was so excellent that as only a second-year student he began to give lectures to his fellow students, sometimes with an audience of 300 people. He also began to disagree with the Tournefort system of plant classification, then the scientific standard, and started to divide his own.

He became collecting and describing plants and animals, travelling up to remote Lapland for it.

[the twinflower (Linnaea borealis). Named after Linnaeus in his taxonomy, it was his favorite flower]

He continued to travel and then set out to study medicine in the Dutch Republic, at the time a more prestigious country for natural history education. On the way there, Linnaeus managed to get himself and his friend run out of town for correcting a mayor's alleged taxidermied hydra heads.

He received a doctoral degree in only two weeks (more a sign of the standards of education at the time than of any particular brilliance of his). In 1735, Linnaeus published the Systema Naturae.

[Systema Naturae]

The 1735 Systema Naturae gained him some fame and publicity, but what truly made him famous and changed the world was its 10th edition. Published in two volumes in 1758 and 1759, Linnaeus official introduced the binomial nomenclature for animals. Up until now, he had used it for plants, but using the same system between Kingdoms and Domains is seminal in the shift to modern biology.