#filipinofoodhistory

Text

Palitaw - Floating Cake recipe from Texas, USA (once aka "New Philippines")

This is our food, this is how we eat…

Recipe from Mrs. Aurea L. Reyes of San Antonio, Texas.

“Mix flour and water. Form into 10 to 20 small balls. Flatten each ball into a round or elongated shape and drop into 8 to 10 cups boiling water. As each cake floats to the surface, remove from water with a slotted spoon. Roll in gated coconut and coat with sugar and sesame seeds. Serve with hot or cold tea. Makes 4 servings.”

Interesting to know, “Nuevas Filipinas and Nuevo Reino de Filipinas were secondary names given to the area of Texas above the Medina River.”

“Following the explorations of Alonso (Álvarez de) Pineda in 1519 and that of Pánfilo (de) Narváez in 1528, Texas became known as Nueva Filipinas – New Philippines- for over 200 years.”

Sources:

-The Institute of Texan Cultures of the University of Texas at San Antonio. 1977. The Melting Pot. Ethnic Cuisine in Texas. San Antonio, Texas. 224 pp.

Handbook of Texas Online, Jesús F. de la Teja, "NEW PHILIPPINES," accessed February 18, 2020, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/usn01.

#philippinefood#philippines#filipinofood#filipinofoodhistory#pinoyfood#food#history#palitaw#philippinehistory#philippinefoodhistory#filipinohistory#texas#usa#floatingcake#gastrobscura#pinoy#pinoypride#pinoyako#pinoygram#filipino#filipinas

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bataan stew

This is our food, this is how we eat...

Towards the end of the defense of Bataan, Philippines in WW II against the Japanese Imperial forces until its eventual surrender on April 9, 1942, "the Filipinos and American forces had been living and fighting on crumbs."

"When infantryman Dominick Pellegrino of Medford, Massachusetts, went to ladle himself a portion of his unit's "Bataan stew", he spotted the skeletal paw of a monkey reaching up from the depths of the pot."

"Soon almost every carabao (water buffalo) on Bataan, some 2800 animals, had been eaten, and the quartermaster began to slaughter the cavalry's mounts, packhorses, and mules. When these too were gone, the men turned to hunting wild pigs, jungle lizards, giant snakes. A veterinary officer who thought birds might make a good meal shot and cooked some crows."

Source:

Norman, M. & Norman, E.M. 2009. Tears in the Darkness. The story of the Bataan Death March and its aftermath. Picador. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York. 464 pp.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinohistory#filipinofood#filipino#history#philippinefoodhistory#Philippines#philippinehistory#philippinefood#philippinearmy#ww2#wwii#war#bataan#japan#japanese#MacArthur#usa#usarmy#stew#pinoyfood#pinoypride#pinoyako#pinoy#food#gastrobscura#atlasobscura#Massachusetts#Medford#deathmarch

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Bubud” – the Igorot rice wine.

This is our food, this is how we drink...

From a lecture delivered before the 8th Meeting of the California Branch of the American Folk Lore Society, April 17th, 1906 at Cloyne Court, Berkeley, California by Captain Henry Du R. Phelan, U.S.V. entitled, “The Peoples of the Philippine Islands, Illustrating with an exhibition of ethnological specimens.”

"In all their feasts a beverage called Bubud plays an important part. This is prepared in the following fashion.

A handful of powdered rice is mixed with the strongly acid juice of a vine and then dried in the sun. Rice is next boiled with water and some of the firs at mixture is added to it, when it is place into a jar and allowed to ferment for eight days. After this it is ready for use. It has a disagreeable taste and occasions a furious rage which nothing can control.”

Above was from the section on “IGORROTES. – In the central chain of mountains of Northern Luzon there is a tribe known as Igorrotes. This name, which means infidel, is applied in a general way to all pagan tribes, but more particularly to certain ones.”

Source:

Phelan, Henry Du Rest. 1906. The Peoples of the Philippine Islands; a lecture delivered before the California branch of the American folk-lore society San Francisco, California. www.hathitrust.org http://hdl.handle.net.2027/miun.afm3313.0001.001.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinohistory#filipino food history#filipinofood#filipino#food history#history#philippinefoodhistory#philippinefood#philippinehistory#philippines#pinoyfood#pinoypride#pinoyako#pinoy#luzon#bubud#igorot

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

GUINIMOS, RICE, and LEGOMBRE - a poem, worth a thousand words.

This is our food, this is how we eat…

A poem of an American soldier, 28th Infantry Regiment, Company M, somewhere in Cagayan de Misamis (Mindanao), 1901.

“There once was a Philippine hombre;

Ate guinimos, rice, and legombre;

His pants they were wide,

And his shirt hung outside;

But this, you must know, is costombre.

He lived in a nipa balay

That served as a stable and sty.

He slept on a mat

With the dog and the cat,

And the rest of the family near by.

He once owned a bueno manoc,

With a haughty and valorous look,

Who lost him amain

And mil pesos tambien,

And now he plays monté for luck.

In this land of dhobie dreams,

Happy, smiling Philippines,

Where the bolo man is hiking all day long,

Where the natives steal and lie,

And Americanos die…”

“Guinimos” appears to be a small fish, most likely anchovies, a typical Filipino food, as it is mentioned several times in the book.

Source:

Gilbert, P. T. 1903. The Great White Tribe in Filipinia. Cincinnati: Jennings and Pye. 303 pp.

#philippinehistory#philippinefood#philippines#philippinefoodhistory#filipinofoodhistory#filipinohistory#filipinofood#filipino#pinoy#pinoyfood#gastrobscura#cagayan

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle Breakfast – the “strange” flavor of miso soup.

This is NOT our food… but the connection to our history is deep, the pain and suffering haunting, and the tragedy should never be forgotten.

“On the morning of December 22 (1941), 85 transport carrying 36,000 troops from the 4th Army invasion force dropped anchor in the waters of Lingayen Gulf (Luzon), preparing for a pre-dawn attack. On the Yae Maru, Ryotaro Nishimura went among his men checking their equipment and quizzing them on the order of battle.

On the morning of the invasion he woke his men at 3 o’clock and huddled with them at breakfast: miso soup and an egg over a thick porridge of barley and white rice.

Japanese soup always reminded the men of home, but on this morning the troops complained the miso has a “strange” flavor, and Ryotaro Nishimura knew that the men had awakened with the metallic taste of fear in their mouths.”

Source:

Norman, M. & Norman, E.M. 2009. Tears in the Darkness. The story of the Bataan Death March and its aftermath. Picador. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York. 464 pp.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipino food history#filipinohistory#filipino#filipinofood#Philippines#pilipinas#philippinefood#pinoy#philippinehistory#luzon#miso#misosoup#みそ#味噌汁#味噌#みそしる#pinoyfood#pinoypride

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is our food, this is how we eat...

Towards the end of the defense of Bataan, Philippines in WW II against the Japanese Imperial forces until its eventual surrender on April 9, 1942, "the Filipinos and American forces had been living and fighting on crumbs."

"When infantryman Dominick Pellegrino of Medford, Massachusetts, went to ladle himself a portion of his unit's "Bataan stew", he spotted the skeletal paw of a monkey reaching up from the depths of the pot."

"Soon almost every carabao (water buffalo) on Bataan, some 2800 animals, had been eaten, and the quartermaster began to slaughter the cavalry's mounts, packhorses, and mules. When these too were gone, the men turned to hunting wild pigs, jungle lizards, giant snakes. A veterinary officer who thought birds might make a good meal shot and cooked some crows."

Source:

Norman, M. & Norman, E.M. 2009. Tears in the Darkness. The story of the Bataan Death March and its aftermath. Picador. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York. 464 pp.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinohistory#filipinofood#filipino#food#history#philippines#philippinefood#philippinehistory#bataan#MacArthur#douglasmacarthur#ww2#wwii#war#japan#japanese#Massachusetts#usa#usarmy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sticky rice ball & salt... food from heaven in Balanga (Bataan)

This is our food, this is how we eat...

"The exodus from Bataan took place in the hottest, driest time of the year, the season of drought. The unclouded sun seared the earth; by afternoon the air was an oven and the ground was rock-hard."

70,000 Filipinos and 12,000 Americans started "The Hike", as known to the men at the time, resulted in the two-week atrocity known later as the "Bataan Death March ".

"The first men to reach Balanga remembered it as a source of food. This was typically only a ball of sticky rice and a pinch of salt, but it was the first evidence that the Japanese did not intend to starve them to death."

Source:

Caldwell, D.L. 2019. Thunder on Bataan. The First American Tank Battles of World War II. Stackpole Books, Lanham, MD. 320 pp.

Background photos from Google.

#filipinofoodhistory#foodhistory#filipinofood#filipino#food#history#philippinefoodhistory#philippinefood#philippinehistory#philippines#Bataan#deathmarch#pinoyfood#pinoypride#pinoy#Balanga

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chocolate / Tsokolate – have you ever wondered why, in Asia, only Filipinos has developed the taste and culture of drinking this rich indulgence?

Try asking your Chinese friend, your Japanese sushi chef, your Vietnamese classmate, or even try your South Asian colleague. Even a Thai or Indonesian would tell you that it’s either tea or coffee that their grandmothers used to prepare, but not a hot chocolate drink over fire that your Lola (grandmother) would made from cacao tablets (tablea) whisked with a batidor or molinillo between the palms of the hands. Or on a rainy morning, we get served with champorado, glutinous rice cooked with chocolate and sugar, paired with tuyo, the staple dried salty herring.

Who knows? One probable reason is that among Southeast Asians, except for the small Chinese-Filipino population, tea drinking is not mainstream in Filipino food culture. Tea plantations did not thrive as an industry, but cacao and coffee did.

Let’s go way, way back - the Maya were drinking chocolate 1,000 years before the Aztecs, and 2,600 years before the Spanish arrived (Civitello, 2011). Chocolate made the long journey from Mesoamerica to Spain, and then to Europe. It never made any real inroads in the coffee-loving Near East, possibly the cult of coffee and the way of life that revolves around the coffee house prevented the establishment of a popular taste for drinking chocolate. Nor did it ever “conquer” India, Southeast Asia, or the Far East, with the exception of the Catholic Philippines(Coe and Coe, 1996).

Spaniards brought from New Spain to the Philippines the cacao plant, the source of the chocolate that Jesuit missionaries and Portuguese businessmen found a necessity of life for their survival. And the hot, thick chocolate drink is still part of the Spanish heritage, even a century of Americanization has not been able to change this (Coe and Coe, 1996).

Who else can concretely mention “chocolate” as profoundly as it permeated into our food other than the Philippines’ national hero…

In Noli Me Tangere, Gat José Rizal (1902), mentioned chocolate several times as exemplified in the section,

“—¿Va usted al convento á visitar al curita Moscamuerta? ¡Ojo! Si le ofrece chocolate, ¡lo cual dudo!... pero en fin si le ofrece, ponga atención. ¿Llama al criado y dice: Fulanito, haz una jícara de chocolate, ¿eh? entonces quédese, sin temor, pero si dice: Fulanito, haz una jícara de chocolate ¿ah? entonces coja usted el sombrero y márchese corriendo.

—¿Qué? preguntaba el otro espantado ¿da jicarazo? ¡Caramba!

—¡Hombre tanto, no!

—¿Entonces?

—Chocolate ¿eh? significa espeso, y chocolate ¿ah? aguado.”

Rough translation appears to be a secret code for servants from the friar P. Salví: “chocolate ¿eh? significa espeso”, “stay, without fear” as it is a rich thick chocolate; “chocolate ¿ah? aguado” means you “take the hat and run away” as the chocolate is watery.

Sources:

Coe, S.D. and Coe, M.D. 1996. The True History of Chocolate. Thames & Hudson Ltd., London. 280 pp.

Civitello, L. 2011. Cuisine & Culture. A History of Food and People. John Wiley & Son, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. 436 pp.

Rizal, José. 1902. Noli Me Tángere. Novela Tagala, Edición completa con notas de R. Sempau. BARCELONA. Casa Editorial Maucci.—Mallorca, 226 y 228 Buenos Ayres. Maucci HermanosCuyo, 1070México. Maucci Hermanos 1.a del Relox, 1. The Project Gutenberg EBook #47584.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinofood#filipinohistory#foodhistory#filipino#food#history#philippinefoodhistory#philippinefood#philippinehistory#Philippines#pinoyfood#pinoyhistory#chocolate#tsokolate#rizal#nolimetangere#asianfood

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The undying mystery of “ADOBO”, the original name lost in history…maybe not

When one mentions quintessential Filipino food, “chicken or pork adobo” is the ubiquitous choice.

As we all know by now, and as has been written multiple times, the term adobo is from the Spanish word adobar, meaning “marinate”. And when the Spaniards arrived in the late 16th century, they probably found the natives using this cooking process, noted by some authors as written in Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala by Pedro de San Buena Ventura in 1613. I have not gotten hold of the book as it is stacked in some University libraries, like the Kroch Library Asia at Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Some more than 200 years later, adobo was written down again and published in the Tagalog-Spanish-Tagalog Dictionary, the Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala (Noceda and De Sanlucar, 1860).

Searching inside the book, the word adobo can be found twice:

- in the Tagalog-Spanish section, within the De la Letra P., P antes de I., as

PINALAM. pc. = Un gẽnero de adobo de venado con vinagre, y el linabus del labot. Vide Chinalan.

The word PINALAM is defined partly as “deer meat (venison) marinated in vinegar”.

I wonder, is PINALAM the old, long-lost original Tagalog word for the cooking process as encountered then by the Spaniards? Later, as we all know, it quietly evolved into the name of the dish itself of adobo. Interesting enough, yet not confirmed.

- searching further in the Spanish-Tagalog section (Vocabulario Hispano-Tagalog), there is no mention of PINALAM. However, the word appears as PANALAM:

Adobo de venado con vinagre, PANALAM. pc.

with exactly the same meaning, “deer meat (venison) marinated in vinegar = PANALAM.

PINALAM and/or PANALAM … can somebody tell me, or give me adobo for breakfast.

Sad to say, there is only the mention of vinegar in the venison, no other ingredients. I assume salt was widely available at that period in time and could have been added to the meat. The description is a far cry from the modern-day recipe with soy sauce, sugar, bay (laurel) leaves, garlic, black pepper, chilies and vegetable oil, etc.

I just wished somebody could have recorded when these ingredients were added, in a letter, in a recipe, in a book, on a leaf or on the wall. We know when the Portuguese/Spaniards came (1521), the Arab traders in 1300s and Chinese merchants in 982 AD or earlier (Newman, 2018), whom we owe the ingredients. Soy sauce was made in China around 2000 years ago, sugar cane from New Guinea travelled to Indonesia and Philippines, then to India around 3000 BC where it transformed into sugar and introduced to China in 800 BC. From Central Asia, most probably Arab traders to southern Philippines came bay (laurel) leaves; garlic, written in a Babylonian tablet recipe around 1750 BC; black pepper was mentioned in the Hindu epic poem, Mahabharata, written in 4th century BC (Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2018);

Only chilies were originally from the New World (Mexico), introduced by Spaniards to Portuguese traders, and as Vasco de Gama made it to India in 1498, spreading it to Thailand, China and Korea. But it is not certain whether Filipinos had already sampled the spicy fruits during Muslim occupation in the decades prior to the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521 (Anderson, 2016).

Sources:

Anderson, H.A. 2016. Chillies: A Global History. Reaktion Book Ltd., London. 150 pp.

DK Publishing (Contributor). 2018. The Story of Food: An Illustrated History of Everything We Eat. DK Publishing (Dorling Kindersley), New York. 360 pp.

Newman, Y. 2018. 7000 Islands: Cherished Recipes and Stories from the Philippines. Hardie Grant Books (London). 336 pp.

Noceda, J. de and De Sanlucar, P. 1860. Vocabulario de la lengua tagala compuesto por varios religiosos doctos y graves, y coordinado por el P. Juan de Noceda y el P. Pedro de Sanlucar. Ultimamente aumentado y corregido por varios religiosos de la orden de Augustinos calzados. Publisher: Reimpreso en Manila: Impr. de Ramirez y Giraudier. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/miun.aqj5903.0001.001. 642 pp.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinohistory#filipinofood#Filipino#Philippines#philippinehistory#philippinefoodhistory#philippinefood#adobo#adobonation#chicken adobo#pork adobo#pinoyfood#pinoyhistory#pinoy#pinoyako#pinoygram#pinoy tambayan#history#food#foodlover#food photography#food and drink#tagalog

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“TINAPAI”, an original rice cake recipe.

This is our food, this is how we eat...

As we all know, after setting sail with five ships from Seville, Spain on August 10, 1519, Ferdinand Magellan landed in “Zamal (Samar, Philippines) on March 16, 1521. After Magellan’s death on April 20, 1521 and after burning the ship “Conceptione”, the two remaining ships sailed from the Visayas on to Mindanao, “whose king in order to make peace with us, drew blood from his left hand marking his body, face, and the tip of his tongue with it as a token of the closest friendship, and we did the same. I (Antonio Pigafetta) went ashore alone with the king in order to see that island.”

After drinking palm wine with the king, Pigafetta noted down the recipe of the food:

“Then the supper, which consisted of rice and very salt fish, and was contained in porcelain dishes, was brought in. They ate their rice as if it were bread, and cook it after the following manner. They first put in an earthen jar like our jars, a large leaf which lines all of the jar. Then they add the water and the rice, and after covering it allow it to boil until the rice becomes as hard as bread, when it is taken out in pieces.”

In his vocabulary of Visayan words, he noted

"Acerte fogacie de rizo = tinapai = for certain Rice cakes"

Source:

Blair, E.H. (Editor). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898, Volume XXXIII, 1519-1522, by Antonio Pigafetta. Translated from the Originals. The Arthur H. Clark Company, Cleveland, Ohio. MCMVI. The Project Guttenberg EBook-No. 42884.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipino food history#filipinohistory#filipinofood#filipino#food#food history#history#philippinefood#philippinehistory#philippines#pinoyfood#pinoymade#pinoypride#pinoygamer#pinoy#samar#magellan#pigafetta#tinapay#tinapai

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

SISING, SISID or SISIG, what’s in a name?

This is our food, this is how we eat…

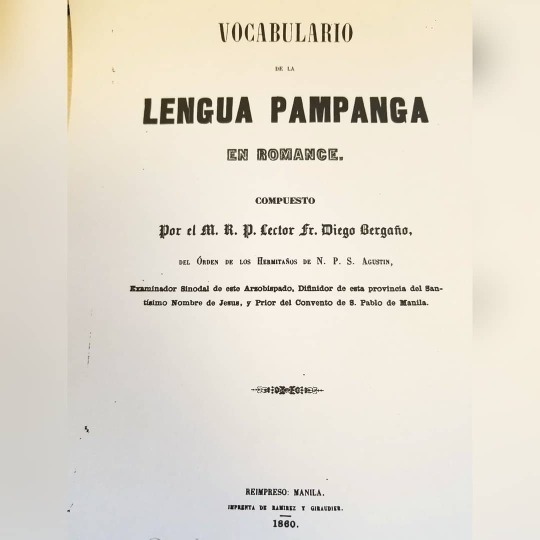

Online information would note that “sisig” was first recorded in a Kapampangan-Spanish dictionary back in 1732 by Diego Bergaño, an Augustinian friar as “a salad including green papaya or green guava eaten with a dressing of salt, pepper, garlic, and vinegar.”

However, searching the same book published in 1860, translated “Sisig” as the Spanish word for “chata”, roughly meaning “flat” or maybe something else.

On the book, “Sising” appears as:

“SISING. (pp.) N. S. Ensalada. Y aun papaya verde, ó guayaba comida con pebre.”, roughly translate to “Salad. And even green papaya, or guava food with pepper.”

There is no mention of salt, garlic or vinegar. Then, in the Spanish-Kapampangan section, “Ensalada.” is written as “Sisid.”

Whatever you call it now - “Sising” or “Sisid”, which probably evolved into the modern-day “Sisig”, is the fatty, salty, greasy, heavenly goodness that we enjoy today…

Source:

Bergaño, D., Guerra, F. and Ramírez, Y G. 1860. Vocabulario de la Lengua Pampanga en Romance. Reimpreso: Manila. Online resource: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ucm.5325289041&view=1up&seq=5

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinohistory#filipinofood#filipino#filipino food history#history#foodhistory#philippinefood#philippinehistory#philippines#philippinefoodhistory#pinoyfood#pinoypride#pinoy#pilipinas#kapampangan#eatpilipinas#pinoyfoodporn#pagkaingpinoy#gastrobscura#panlasangpinoy

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unbroken… a lone chicken egg, a gift from a Filipino guerilla liberator.

This is our food, this is how we eat…

“…they (the Sams family - Jerry, Margaret, David and Gerry Ann) hurried back to their barracks, where they had their first face-to-face meeting with one of their liberators: a Filipino guerilla. With a wide grin, he presented them with a lone chicken egg that had somehow come through unbroken.

It was a lovely sight and quite a treasure, and it took Jerry less than ten minutes to hurriedly scramble it up and serve it to Margaret and David.”

In commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Los Baños Internment Camp, February 23, 1945.

Freedom at last, after almost 3 years of Japanese imprisonment, experiencing torture, hunger and deprivation; amidst the beauty and lush greenery of the College of Agriculture campus in Los Baños. Despite way behind Japanese enemy lines, a successful raid by American troops and Filipino guerillas freeing more than 2,000 Allied men, women and children.

No U.S. casualties that day, but a salute to the supreme sacrifice of two guerillas from Hunters ROTC, Atanacio Castillo and Anselmo Soler, who unselfishly gave their lives so that others can be free.

Source:

Henderson, B. 2015. Rescue at Los Baños. The most daring prison camp raid of World War II. Harper-Collins Publishers, New York. 366 pp

#philippinefood#history#filipinohistory#filipino#pinoy#philippinefoodhistory#pinoypride#philippinehistory#food#filipinofoodhistory#filipinofood#uplb#wwii#ww2#losbanos

1 note

·

View note

Text

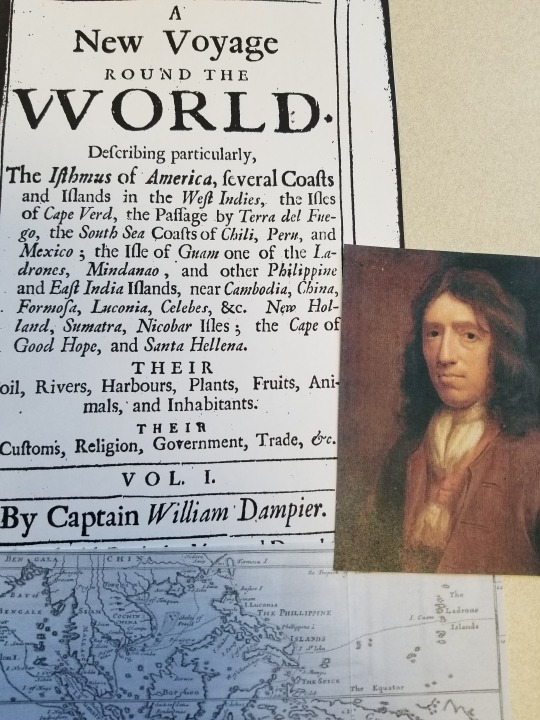

A 17th century British pirate and the first written recipe of Atsarang (Burong) Mangga – an unlikely encounter...

"When the mango is young they cut them in two pieces and pickle them with salt and vinegar in which they put some cloves of garlic. This is an excellent sauce and much esteemed; it is called mango-achar. Achar I presume signifies sauce.”

As written by the British-born William Dampier in his book, A New Voyage Round the World, which first appeared in 1697 (Dampier, 1697).

This appears to be more of the recipe of atsarang or burong mangga (pickled mango) when Dampier reached the Philippines from Guam on his 17th century journey around the world. He further noted, “The mangoes here grow on trees as big as apple-trees: those at Fort St. George are not so large. The fruit of these is as big as a small peach but long and smaller towards the top: it is of a yellowish colour when ripe; it is very juicy, and of a pleasant smell and delicate taste.”

The word, achar, is Hindustani (from Persian āchār) and described as pickles, as prepared in the Indian subcontinent (Speake and LaFlaur, 1999); which is most likely the origin of the Tagalog word, "atsara", with exactly the same meaning.

Sources:

Dampier, W. 1697. A New Voyage Round the World. Adam and Charles Black 4, 5 & 6 Soho Square, London, W.1. A Project Gutenberg Australia eBook No.: 0500461h.html.

Speake, J. and LaFlaur, M. 1999. The Oxford Essential Dictionary of Foreign Terms in English. Oxford University Press. 496 pp.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinofood#filipinohistory#filipino#food#history#philippinefoodhistory#philippinefood#philippinehistory#philippines#pickles#mango#pickledmango#mangga#burongmanga#atsara#atsarangmangga#dampier

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

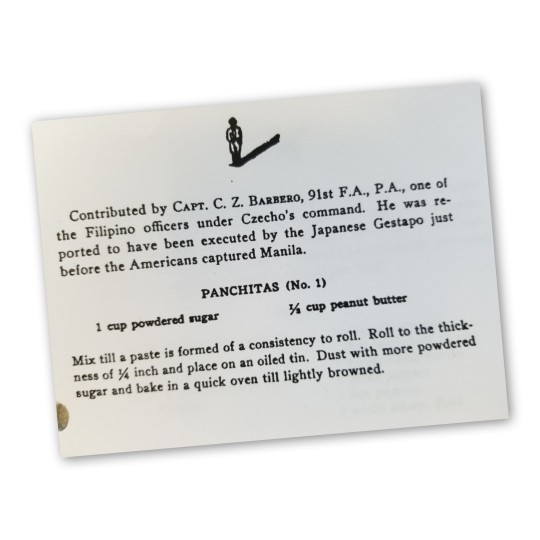

PANCHITAS - a war hero’s forgotten recipe

Simple as it may seem - peanut butter and powdered sugar, mixed to a paste and baked to golden brown… but as one understands that it came from a Filipino war hero, long-forgotten in the pages of history, there is something deeper and sentimental meaning to those simple ingredients.

The recipe was from the book, Recipes Out of Bilibid, contributed by Capt. C.Z. Barbero, 91st F.A., P.A. a Filipino military officer under Lieutenant-Colonel George Dewey Vanture, Field Artillery, USA, as he was imprisoned in Bilibid Prisoner of War (POW) camp during World War II by the Japanese.

Sad to say, the book noted, “He (Capt. Barbero) was reported to have been executed by the Japanese Gestapo just before the Americans captured Manila.” (Fowler & Wagner, 1946).

Source:

Fowler, H. C. (Halstead Clotworthy) and Wagner, D. 1946. Recipes Out of Bilibid. New York, N.Y.: G.W. Stewart, publisher. 81 pp.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinofood#filipinohistory#foodhistory#filipino#food#history#philippinefoodhistory#philippinefood#philippines#pinoyhistory#pinoyfood#pinoy#pinoygram#peanutbutter#WWII#WW2#recipes#philippinearmy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond tea itself, a subtle connection between tea and Philippines…

No doubt, tea was most likely brought to the Philippines from China as it was consumed about 3000 B.C. (Civitello, 2011), way before the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan landed in Samar Island in 1521.

Sad to say, it never seeped into the Filipino food culture, as very rare that a guest at a home will be offered tea; unlike as it has abetted Chinese poets in their greatest achievements and burrowed itself to the core of the Japanese soul (Mair and Hoh, 2009).

The relationship doesn’t end there, as the twain connects somehow…

Tea’s scientific name is Camellia sinensis or Camellia assamica, named by Carl Linnaeus in honour of Georg Joseph Kamel, a Jesuit missionary, pharmacist and naturalist who regarded Philippines as his adopted homeland.

Kamel was sent to Philippines in 1688, assigned to Colegio Máximo de San Ignacio (now the site of Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila). He turned to local nature to identify resources, which he could use in his practice. Remarkably for a Jesuit of low rank, he entered communication with European scholars and exchanged knowledge and materials both in the Indies and Europe. His work appeared as an Appendix to the 3rd volume of Historia, published in 1704 (Kroupa, 2015).

Unfortunately, Kamel’s contribution is mostly forgotten in the Philippines; as I never heard of him in history books nor mentioned during my years at the College of Agriculture, University of the Philippines at Los Baños.

Sources:

Civitello, L. 2011. Cuisine and Culture. A History of Food and People. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New Jersey. 436 pp.

Kroupa, S. 2015. Ex epistulis Philippinensibus: Georg Joseph Kamel SJ (1661-1706) and His Correspondence Network. Centaurus. Vol. 57: pp. 229-259.

Mair, V.H. and E. Hoh. 2009. The True History of Tea. Thames & Hudson, London. 280 pp.

#philippines#food#filipinofood#filipinofoodhistory#foodhistory#camellia#magellan#philippinefood#philippinefoodhistory#tea#filipino#losbaños

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

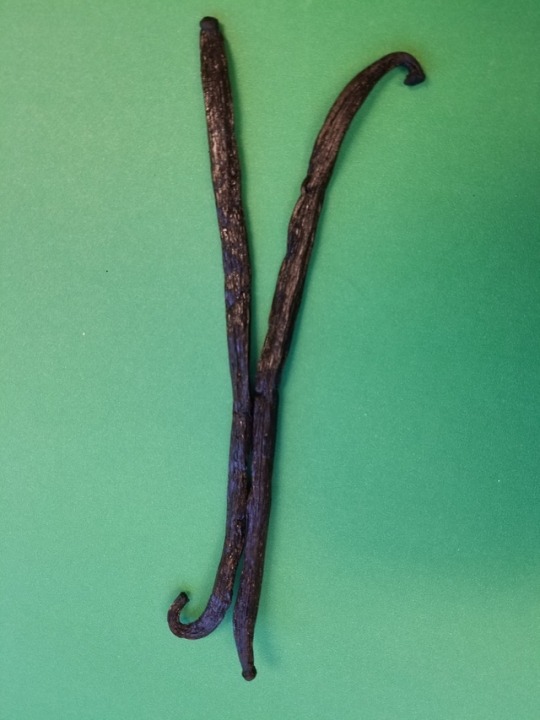

Tahiti - Philippines, an unlikely vanilla connection…

Vanilla beans from the Americas-Spanish Galleon Trade between Acapulco and Manila-a plant laboratory in Manila-a French Navy Admiral-French Polynesia-Tahiti

Vanilla, as we may know, is a flavoring derived from orchids of the genus Vanilla, (V. planifolia), mainly a Mexican species, cultivated and consumed by the Aztecs and other Mesoamericans even before Christopher Columbus landed in the New World.

There are at least 150 species of vanilla indigenous to tropical regions worldwide, but only two species proved edible, V. planifolia and V. pompona Schiede. The third one is V. tahinensis, produced in Tahiti, believed to be a cross between the two species above which originated from stocks in a plant laboratory in Manila, Philippines in the 1700s (Rain, 2004). Vanilla, which is not native to the Philippines, was previously introduced by the Spaniards via the Manila Galleon trade from the New World.

There were at least three introductions of vanilla to Tahiti between 1848 and 1898. The first introduction to French Polynesia dates from 1848 by French Admiral Ferdinand-Alphonse Hamelin, from Manila in the Philippines. The seeds of these pods could be the origin of the Tahitian vanilla (Odoux and Grisoni, 2011).

Sources:

Rain, P. 2004. Vanilla. The cultural history of the world’s most popular flavor and fragrance. Penguin Group, USA. 372 pp.

Odoux, E. and M. Grisoni. Editors. 2011. Vanilla. Medicinal and aromatic plants – industrial profiles. CRD Press, Boca Raton, FL. 387 pp.

#filipinofoodhistory#filipinofood#philippines#tahiti#vanilla#philippinefood#pinoyfood#foodhistory#food#filipino#vanillatahinensis

7 notes

·

View notes