#incarcerees

Photo

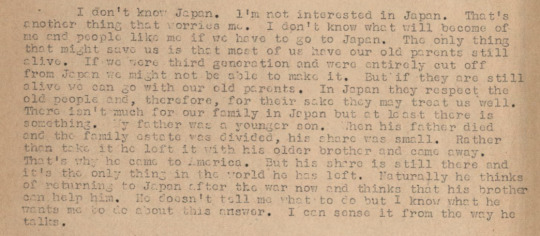

On August 10, 1942, incarcerees arrived at the Minidoka War Relocation Center. The number of incarcerees reached 7,318 at its maximum population.

#incarcerees#Minidoka National Historic Site#Minidoka War Relocation Center#Minidoka Internment National Monument#Japanese-American history#travel#Jerome County#desert#architecture#10 August 1942#anniversary#USA#US history#World War Two#World War II#WWII#free admission#vacation#landscape#tourist attraction#original photography#summer 2017#countryside

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Oki registers two U.S.-born incarcerees of Granada Relocation Center on 2/12/1943.

This registration form is probably the one which asked incarcerees if they would a) be willing to serve in the U.S. armed forces and b) renounce allegiance to the Japanese emperor. Those who answered “No” to both could be segregated as “disloyal.”

Record Group 210: Records of the War Relocation Authority

Series: Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority

Image description: Three young women of Japanese descent sit at a roughly-made table. One of the women is filling out a form; the other two women are each leaning their head on their hand and do not look very excited.

#archivesgov#January 12#1943#1940s#World War II#WWII#Asian American history#Japanese American history#Japanese American incarceration#loyalty questionnaire

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 paved the way for their removal, Japanese-Americans sold their homes, farms and businesses, often for pennies on the dollar. While incarcerated they worked menial jobs for $12 or $16 or $19 a month — hardly enough to survive on, let alone save for a new beginning. Unable to return to their farms — restrictive covenants and alien land laws often banned Japanese-Americans and their Japanese parents — many who worked on or owned strawberry or lettuce fields before the war moved to Los Angeles and became gardeners, trying to settle into an urban life for the first time in their lives.

Los Angeles, which was home to the largest ethnically Japanese community in North America before the war, was changing, too. The War Relocation Authority, the federal agency tasked with operating the 10 internment camps, worked to empty those camps as quickly as possible following Roosevelt’s closure order in December 1944. The W.R.A. shuttered almost all the camps in the fall of 1945. (One camp, Tule Lake, remained open until March 1946 to house “disloyal” incarcerees.) Each internee received $25 and a train ticket to wherever they wanted to go.

Housing was strained to the seams across the United States, but the situation in Los Angeles, described by one official in October 1945 as “full of dynamite,” was especially dire. More than 1.3 million people — roughly one out of every 100 Americans — moved to California between 1940 and 1944. The California State Reconstruction and Reemployment Commission estimated that 625,000 new homes would need to be built to accommodate the growth in the five years following the war, including 280,000 in Los Angeles County alone. During the war, Little Tokyo first became a ghost town, then swelled with Southern Black workers arriving for defense jobs; for three years Little Tokyo was known as Bronzeville. It was into this chaos that the W.R.A. planned to unload 1,200 incarcerees each week that fall.

By the end of 1945, a month after closing nine of the 10 W.R.A. camps, thousands of Japanese-Americans returned to the West Coast with nowhere to live. Those who couldn’t find other housing took rooms in $1-a-night hostels carved out of prewar hotels and Buddhist temples, or trailers and repurposed Army barracks.

Communities with as many as 1,000 residents filled mazes of barracks and trailers in El Segundo, Hawthorne, Burbank, Inglewood and Santa Monica. Even Lomita Flight Strip, an airfield used to house and train squadrons of P-38 fighter pilots 17 miles south of downtown Los Angeles, was converted into housing. To get into Los Angeles to find work required 85 cents each way, and a four-hour round-trip by bus. Charlotte Brooks, a historian, described the camps as “isolated ghettos that perpetuated the hardships of incarceration.”

— For Japanese-Americans, Housing Injustices Outlived Internment

#bradford pearson#for japanese-americans housing injustices outlived internment#history#racism#housing#ww2#internment of japanese americans#executive order 9066#usa#asian americans#japanese americans#los angeles#california#little tokyo#camp tulelake#war relocation authority#charlotte brooks

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Nisei Who Said ‘No’

This post references a report from the United States War Relocation Authority Reports. The collection is comprised of more than fifty mimeographed reports detailing the operation of War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps used to house Japanese American incarcerees during World War Two.

Series 2 is composed of 14 “notes” published by the Community Analysis Section (CAS) between 1944…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Map reflection

I wasn’t sure at first what to do at all for this map so I started with research and tried to find pieces I hadn’t been entirely familiar with along with some I was very familiar with. My map should follow the path of government actions and their impacts. This includes the food shortage that occurred early with incarceration, and also more long term effects. I hope to incorporate specifics about life in the camps which will be part of the continued motion of the Rube Goldberg mechanism but bigger points are where the viewer will have to manually start the machine. These larger points will include the food shortage, long term mental and physical health impacts on incarcerees, displaced peoples after the war, the model minority myth and the lack of appropriate reparations (people who were not included in reparations as well as the ordeal required to get reparations.) My rough sketch includes these points in more broad ways but I intend to have it start at government actions and then go onto a continued motion of uncovering the many effects of those choices before the viewer starts the machine again at the next government action. This intends to point misdirected government actions towards minorities.

0 notes

Text

Is NY Concealing Sex Assault Accusations Against Prison Workers?

Is NY Concealing Sex Assault Accusations Against Prison Workers?

By TCR Staff | November 3, 2022

The New York prison system, managed by the State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, may be suppressing incarcerated people’s complaints of sexual assault against its guards, discounting their testimony, and failing to hold anyone accountable, reports Victoria Law for The Intercept. The allegations stem from the case of Robert Adams, an incarceree…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

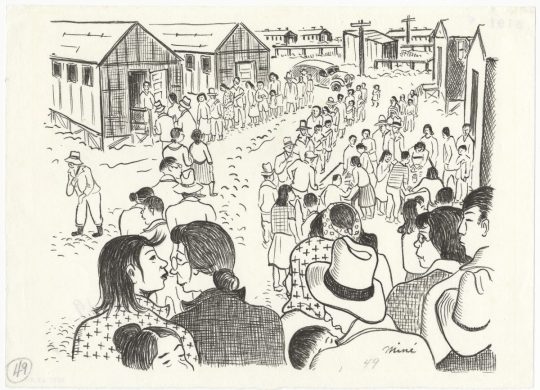

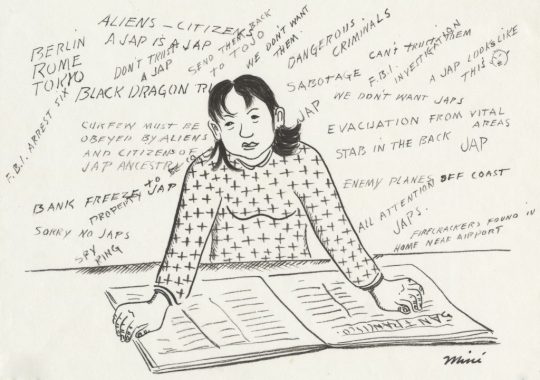

Citizen 13660, a Graphic Memoir of Japanese Concentration Camps, Is an Understudied Masterpiece by Miné Okubo.

On the 75th anniversary of its publication, the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) has opened a new exhibition, “Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece: The Art of Citizen 13660.

” This groundbreaking memoir of nearly 200 illustrations, is an insider’s view of the World War II incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans – the first book-length account of America’s concentration camps by a former incarceree.

“Before World War II, Okubo’s future as an American artist seemed limitless. But her abrupt detention in America’s concentration camps shifted her artistic focus to document this new constrained life with a prolific energy,” said Kristen Hayashi, Ph.D., JANM’s director of collections management & access and curator. “Cameras were banned in the camps, so instead Okubo produced hundreds of sketches and drawings, capturing a chapter of history that could have easily been forgotten.

”https://rafu.com/.../janm-opens-new-exhibition-mine.../

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On August 10, 1942, incarcerees arrived at the Minidoka War Relocation Center. The number of incarcerees reached 7,318 at its maximum population.

#incarcerees#arrived#Minidoka National Historic Site#Idaho#US history#Minidoka War Relocation Center#10 August 1942#80th anniversary#travel#high desert#free admission#original photography#Japanese American history#vacation#never again#summer 2017#WWII#World War Two#landmark#tourist attraction#architecture#World War II#Minidoka Internment National Monument#landscape#countryside#USA

1 note

·

View note

Link

By Natasha Varner

Nearly 75 years ago, 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent were stripped of their rights and property under the guise of national security.

They were packed into trains and buses and moved from their West Coast homes — to temporary holding stations at fairgrounds and racing tracks, and then to permanent camps in remote parts of Idaho, California, Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Texas and Arkansas. Though several cases challenging the legality of this imprisonment made it all the way to the Supreme Court, only a single ruling favored the Japanese American petitioners.

It might come as a surprise, then, that they retained a key tenet of citizenship for the duration of their incarceration: the right to vote. However, between racially motivated interventions and inadequate voter education, this right was only nominally intact.

Absentee voting had existed in some form since 1652, but World War II marked the first and only time in US history that states had to make large-scale arrangements for an incarcerated civilian population to cast votes in absentia. The result was a hodgepodge of rules and regulations that effectively disenfranchised the Japanese American electorate.

One of the first questions to confound wartime voting planners was where exactly the civilian incarcerees should vote. In California, the state with the highest population of displaced Japanese Americans, the constitution stipulated that residence had to be “of choice” in order to qualify for voter registration. It was plain to all that the prison camps were anything but residences of choice. As a result, Japanese Americans were instructed to vote in the precincts where they’d lived prior to incarceration. Other states with camps, fearful of the influence these “enemy aliens” might have on local elections, enacted similar regulations.

By August 1942, the Wartime Civil Control Administration released a policy statement announcing that “qualified citizen evacuees” — the people held in camps — were entitled to the same absentee voting rights as any other citizen who was unable to be present at his or her registered polling place. But states and counties were left to grapple with what exactly those absentee voting rights were in this unprecedented scenario.

Even as the logistics of voting and other basic facets of civilian incarceration were being sorted out, an editorial in the newly minted Tanforan Totalizer urged residents, many of whom were living in old horse stalls at that race track-turned-prison, not to let their “civic consciousness atrophy”:

Civic duty aside, many Japanese Americans felt that they had no choice but to cast a ballot. Election laws stipulated that voter registration would automatically expire if an individual failed to vote in even a single election cycle. However, as incarcerees prepared for the impending midterm elections, they had limited awareness of the issues and candidates due to lack of access to news sources. To make matters worse, new voting regulations prohibited electioneering in the camps.

From Utah’s Topaz concentration camp in November 1942, Doris Hayashi wrote in her diary, “I haven’t been able to do any reading on these issues so it was rather blind voting for me.” A fellow prisoner, Charles Kikuchi, had a similar experience: “I did not know much about the local issues, so I left most of them blank. … California politics are so distant to me now. I wonder how my interest in such things will be with the passage of time.”

Read more...

https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-10-18/japanese-americans-incarcerated-during-world-war-ii-were-still-allowed-vote-kind

#justice#pri#japanese american#japanese incarceration#japanese internment#nikkei#voting#election day#elections#representation#absentee ballot#politics

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

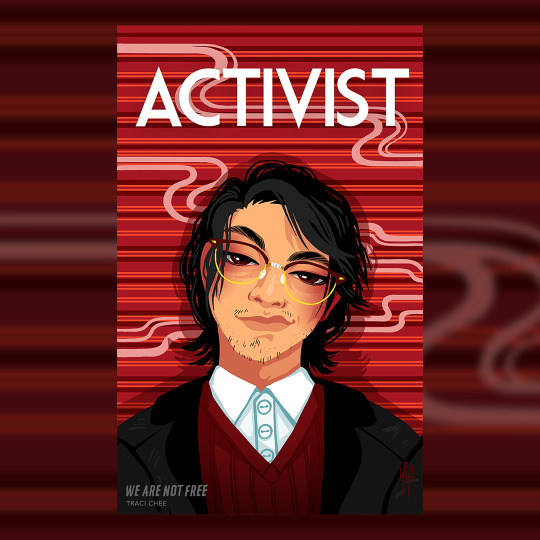

I think we hear a lot about how "good" & "obedient" the Japanese Americans were in WWII, but the incarcerees were not a monolith. They were from diverse backgrounds & held diverse opinions, and rather than submitting to their unjust treatment, a great many of them resisted.

.

If you haven’t read the first three parts of this series, you can read them here:

I) the mass eviction

II) the temporary detention centers and incarceration camps

III) the Japanese-American combat team

.

In 1943, nearly a year after the mass eviction that forced more than 100,000 Japanese Americans from their homes on the west coast, the US government announced that all incarcerees age 17+ would be required to register their names, backgrounds, and allegiances. This registration, which eventually came to be known as the “loyalty questionnaire,” soon became a source of great conflict among the incarcerees due to two questions: Question #27 asked incarcerees if they would serve in the US military, wherever ordered; #28 required them to “forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor.”

.

The wording of these questions led to weeks of confusion and controversy. Some feared feared a “yes” to #27 would enlist them in the military. Others criticized the registration as being “too little, too late.” Many first-generation immigrants were concerned that if they answered “yes” to #28, they would be stripped of their Japanese citizenship--the only citizenship they had--and thus become stateless persons. Some of their American-born children were affronted by the assumption that they’d ever been loyal to Japan in the first place.

.

Despite all of these nuances, however, in the end the federal government accepted only two responses: Incarcerees either replied with an unqualified “yes” to both questions, or their answers were recorded as “no” and “no.”

.

Throughout the late spring and summer of 1943, the divide between those who had answered “yes” and those who were branded “No-Nos” caused extreme tensions between Japanese Americans and with camp administrators. After several violent confrontations, some of which involved the deaths of incarcerees, the Japanese Americans were subjected to another forced relocation, as the “No-Nos” were shipped off to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a camp with higher fences, more soldiers, and heavier artillery to guard the so-called “disloyals” and “troublemakers.”

.

Tule Lake soon became the largest Japanese American incarceration camp of World War II, with more than 18,000 incarcerees crammed into less than 1.75 square miles. Under conditions of overcrowding, inadequate facilities and food supplies, unsafe work environments, and the inevitable differences arising out of so large and diverse a population, Tule Lake became the site of strikes, unlawful detentions, fights, renunciations of American citizenship, and the rule of martial law.

.

This history remains controversial and at times contradictory, but it’s clear that the Japanese American incarcerees were far from a homogenous group of quietly suffering victims. Some resisted their treatment through the due process of the law. Some organized community protests. Some refused to answer the loyalty questionnaire. Some were violent. Some burned their draft cards. Decades later, many of these stories are still emerging, and they continue to demonstrate that resistance is woven into the very fabric of the incarceration.

.

Preorder your copy here or add it on Goodreads!

.

Illustration by Yoshi Yoshitani.

.

(image: illustration of a young Japanese-American man from the 1940s in a red sweater and white shirt with broken glasses)

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today in #history: #OTD, April 1, 1942, the first Japanese arrived Manzanar War Relocation Center in #California after being forced from their homes under Executive Order 9066. The residential area at the Manzanar War Relocation Center was about one square mile and held a population of 10,000. In an effort to make the desert landscape feel more welcoming, the incarcerees built gardens and water features, which are still present in various states of restoration today. After the site closed in 1945, the buildings were either moved, sold for scrap, or demolished. Replicas of two barracks, a mess hall, and a women's latrine have been built at the site on their original foundations. An informative museum is located in the original auditorium building and the cemetery at the rear of the property help put the site into context. Today the site is preserved and interpreted as part of the @NationalParkService as @manzanarnps. #ca #cahistory #nationalpark #nps #nps103 #FindYourPark #goparks #ushistory #americanhistory #nationalparkgeek #travelblog #travelblogger #explore #blog #blogger #manzanar #nationalhistoricsite #wwii #worldwarii #sierranevada #nrhp #nationalparkservice #gardens #optoutside #smallparksaturday #todayinhistory (at Manzanar National Historic Site) https://www.instagram.com/p/B-dXhyIjU__/?igshid=elnslvba2gaz

#history#otd#california#ca#cahistory#nationalpark#nps#nps103#findyourpark#goparks#ushistory#americanhistory#nationalparkgeek#travelblog#travelblogger#explore#blog#blogger#manzanar#nationalhistoricsite#wwii#worldwarii#sierranevada#nrhp#nationalparkservice#gardens#optoutside#smallparksaturday#todayinhistory

1 note

·

View note

Text

Illinois Scores Top Rank in Reintegrating Ex-Incarcerees, Alaska is Lowest

Illinois Scores Top Rank in Reintegrating Ex-Incarcerees, Alaska is Lowest

In the last 18 months, states have adopted a more “enlightened” approach to integrating formerly incarcerated individuals in civil society, in areas ranging from the restoration of voting rights to eliminating discrimination in hiring, according to a report by the Collateral Consequences Resource Center (CCRC).

“But there is still a long way to go before people with a record are treated fairly in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Can the Eighth Amendment Protect Transgender Incarcerees?

Can the Eighth Amendment Protect Transgender Incarcerees?

In September 2017, Adree Edmo, an incarcerated transgender woman, sued the Idaho Department of Corrections for refusing to provide her with medically necessary transition surgery, saying the refusal violated the Eighth Amendment.

Many like her were denied such treatment in the past, as some correctional facilities had routinely rejected transgender people’s access to necessary hormone therapy,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

States Increase Efforts to End 'Internal Exile' of Former Incarcerees: Report

States Increase Efforts to End ‘Internal Exile’ of Former Incarcerees: Report

Efforts to restore rights of individuals released from jail to accelerate their reintegration into civil society picked up momentum during 2021, according to the Collateral Consequences Resource Center (CCRC).

In a report released Monday, CCRC said legislatures around the country were slowly reducing the barriers faced by people with criminal records.

“This year’s rich harvest brings the total…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Covid-19 : le passe sanitaire pourrait bientôt être imposé dans les stations de ski, selon Attal

Covid-19 : le passe sanitaire pourrait bientôt être imposé dans les stations de ski, selon Attal

https://twitter.com/Europe1/status/1462348716522803205?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1462348716522803205%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_c10&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.leparisien.fr%2Fsociete%2Fsante%2Fcovid-19-nouvelle-nuit-de-violences-en-guadeloupe-5-personnes-incarcerees-depuis-vendredi-suivez-notre-direct-21-11-2021-DBUS2SWPQBEOBAVC4LMKUCZHIM.php

View On WordPress

0 notes