#latin american and caribbean studies

Text

imperialism and science reading list

edited: by popular demand, now with much longer list of books

Of course Katherine McKittrick and Kathryn Yusoff.

People like Achille Mbembe, Pratik Chakrabarti, Rohan Deb Roy, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, and Elizabeth Povinelli have written some “classics” and they track the history/historiography of US/European scientific institutions and their origins in extraction, plantations, race/slavery, etc.

Two articles I’d recommend as a summary/primer:

Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. May 2016.

Kathryn Yusoff. “The Inhumanities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020.

Then probably:

Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. “Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times.” Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives. 2023.

Sharae Deckard. “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden.” 2010. (Chornological overview of development of knowledge/institutions in relationship with race, slavery, profit as European empires encountered new lands and peoples.)

Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017, (Interesting case study. US corporations were building fruit plantations in Latin America and rubber plantations in West Africa during the 1920s. Medical doctors, researchers, and academics made a strong alliance these corporations to advance their careers and solidify their institutions. By 1914, the director of Harvard’s Department of Tropical Medicine was also simultaneously the director of the Laboratories of the Hospitals of the United Fruit Company, which infamously and brutally occupied Central America. This same Harvard doctor was also a shareholder in rubber plantations, and had a close personal relationship with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which occupied West Africa.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties.” 2008. (Case study of how British wealth and industrial development built on botany. Examines Joseph Banks; Kew Gardens; breadfruit; British fear of labor revolts; and the simultaneous colonizing of the Caribbean and the South Pacific.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” 2014. (Indigenous knowledge systems; “nuclear colonialism”; US empire in the Pacific; space/satellites; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.)

Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal #115, February 2021. (”Pest control”; termites; mosquitoes; fear of malaria and other diseases during German colonization of Africa and US occupations of Panama and the wider Caribbean; origins of some US institutions and the evolution of these institutions into colonial, nationalist, and then NGO forms over twentieth century.)

Some of the earlier generalist classic books that explicitly looked at science as a weapon of empires:

Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World; Delbourgo’s and Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World; the anthology Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World; Canzares-Esquerra’s Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World.

One of the quintessential case studies of science in the service of empire is the British pursuit of quinine and the inoculation of their soldiers and colonial administrators to safeguard against malaria in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia at the height of their power. But there are so many other exemplary cases: Britain trying to domesticate and transplant breadfruit from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to feed laborers to prevent slave uprisings during the age of the Haitian Revolution. British colonial administrators smuggling knowledge of tea cultivation out of China in order to set up tea plantations in Assam. Eugenics, race science, biological essentialism, etc. in the early twentieth century. With my interests, my little corner of exposure/experience has to do mostly with conceptions of space/place; interspecies/multispecies relationships; borderlands and frontiers; Caribbean; Latin America; islands. So, a lot of these recs are focused there. But someone else would have better recs, especially depending on your interests. For example, Chakrabarti writes about history of medicine/healthcare. Paravisini-Gebert about extinction and Caribbean relationship to animals/landscape. Deb Roy focuses on insects and colonial administration in South Asia. Some scholars focus on the historiography and chronological trajectory of “modernity” or “botany” or “universities/academia,”, while some focus on Early Modern Spain or Victorian Britain or twentieth-century United States by region. With so much to cover, that’s why I’d recommend the articles above, since they’re kinda like overviews.Generally I read more from articles, essays, and anthologies, rather than full-length books.

Some other nice articles:

(On my blog, I’ve got excerpts from all of these articles/essays, if you want to search for or read them.)

Katherine McKittrick. “Dear April: The Aesthetics of Black Miscellanea.” Antipode. First published September 2021.

Katherine McKittrick. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe. 2013.

Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” A chapter in: Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. 2004.

Kathleen Susan Murphy. “A Slaving Surgeon’s Collection: The Pursuit of Natural History through the British Slave Trade to Spanish America.” 2019. And also: “The Slave Trade and Natural Science.” In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History. 2016.

Timothy J. Yamamura. “Fictions of Science, American Orientalism, and the Alien/Asian of Percival Lowell.” 2017.

Elizabeth Bentley. “Between Extinction and Dispossession: A Rhetorical Historiography of the Last Palestinian Crocodile (1870-1935).” 2021.

Pratik Chakrabarti. “Gondwana and the Politics of Deep Past.” Past & Present 242:1. 2019.

Jonathan Saha. “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017.

Zoe Chadwick. “Perilous plants, botanical monsters, and (reverse) imperialism in fin-de-siecle literature.” The Victorianist: BAVS Postgraduates. 2017.

Dante Furioso: “Sanitary Imperialism.” Jeremy Lee Wolin: “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.” Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” Andrew Herscher and Ana Maria Leon. “At the Border of Decolonization.” All from e-flux.

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. 2 October 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “Introduction: Nonhuman Empires.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (1). May 2015.

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017).

Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner. “Monster as Medium: Experiments in Perception in Early Modern Science and Film.” e-flux. March 2021.

Lesley Green. “The Changing of the Gods of Reason: Cecil John Rhodes, Karoo Fracking, and the Decolonizing of the Anthropocene.” e-flux Journal Issue #65. May 2015.

Martin Mahony. “The Enemy is Nature: Military Machines and Technological Bricolage in Britain’s ‘Great Agricultural Experiment.’“ Environment and Society Portal, Arcadia. Spring 2021.

Anna Boswell. “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” 2018. And; “Climates of Change: A Tuatara’s-Eye View.”2020. And: “Settler Sanctuaries and the Stoat-Free State." 2017.

Katherine Arnold. “Hydnora Africana: The ‘Hieroglyphic Key’ to Plant Parasitism.” Journal of the History of Ideas - JHI Blog - Dispatches from the Archives. 21 July 2021.

Helen F. Wilson. “Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes.” Environment and Planning. July 2019.

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Kirsten Greer. “Zoogeography and imperial defence: Tracing the contours of the Neactic region in the temperate North Atlantic, 1838-1880s.” Geoforum Volume 65. October 2015. And: “Geopolitics and the Avian Imperial Archive: The Zoogeography of Region-Making in the Nineteenth-Century British Mediterranean.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2013,

Marco Chivalan Carrillo and Silvia Posocco. “Against Extraction in Guatemala: Multispecies Strategies in Vampiric Times.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. April 2020.

Laura Rademaker. “60,000 years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

Paulo Tavares. “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazon’s Deep History.” Architecture in the Anthropocene. Edited by Etienne Turpin. 2013.

Kathryn Yusoff. “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time.” Social Text. 2019. And: “The Anthropocene and Geographies of Geopower.” Handbook on the Geographies of Power. 2018. And: “Climates of sight: Mistaken visbilities, mirages and ‘seeing beyond’ in Antarctica.” In: High Places: Cultural Geographies of Mountains, Ice and Science. 2008. And:“Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene.” 2017. And: “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” 2017.

Mara Dicenta. “The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego.” Arcadia. Spring 2020.

And then here are some books:

Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Helen Tilley, 2011); Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Londa Schiebinger, 2004)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten A. Greer); The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge (Arndt Brendecke, 2016); Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2014)

Anglo-European Science and the Rhetoric of Empire: Malaria, Opium, and British Rule in India, 1756-1895 (Paul Winther); Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands (Andrew Stuhl)

Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (Britt Rusert, 2017); Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (Jonathan Saha)

The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa (Bernhard Gissibl, 2019); Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century (Edited by Adriana Craciun and Mary Terrall, 2019)

Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500-1850 (Cameron B. Strang); The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022); Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Allison Bigelow, 2020); The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods); American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Megan Raby, 2017); Producing Mayaland: Colonial Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism (Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, 2023)

Domingos Alvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (James Sweet, 2011); A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Anya Zilberstein, 2016); Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines (Sarah Steinbock-Pratt, 2019); Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea, 1800-1970 (Edited by Anderson, Rozwadowski, et al, 2016)

Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Maile Arvin); Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (Janet Dorothy Larkin, 2018); A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (Michael A. Verney, 2022); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013)

Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Daniela Cleichmar, 2012); Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India (Arnab Dey, 2022); Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopoeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Edited by Crawford and Gabriel, 2019)

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment (Hi’ilei Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart, 2022); In Asian Waters: Oceanic Worlds from Yemen to Yokkohama (Eric Tagliacozzo); Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017); Turning Land into Capital: Development and Dispossession in the Mekong Region (Edited by Hirsch, et al, 2022); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski); Colonial Fantasies, Imperial Realities: Race Science and the Making of Polishness on the Fringes of the German Empire, 1840-1920 (Lenny A. Urena Valerio); Against the Map: The Politics of Geography in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Adam Sills, 2021)

Under Osman’s Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail, 2017); Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Jim Endersby); Proving Grounds: Militarized Landscapes, Weapons Testing, and the Environmental Impact of U.S. Bases (Edited by Edwin Martini, 2015)

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Multiple authors, 2007); Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Peter Redfield); Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Andrew Togert, 2015); Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of ‘Green’ Capitalism (Hannah Holleman, 2016); Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and the Reordering of Biodiversity Governance (Katja Grotzner Neves, 2019)

Botanical Entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England (Anna K. Sagal, 2022); The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Harriet Ritvo); Rubber and the Making of Vietnam: An Ecological History, 1897-1975 (Michitake Aso); A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Kathryn Yusoff, 2018); Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt (Jessica Barnes, 2023); No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers); Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1768-1941 (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017); Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia (Douglas C. Harris, 2001); Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep Time (Edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Jakelin Troy); Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Joyce Chaplin, 2001)

American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 (Jeremy Zallen); Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Erik Linstrum, 2016); Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Water (James Pettifer and Mirancda Vickers, 2021); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti); Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea (David Fedman)

Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Julie Cruikshank); The Fishmeal Revolution: The Industrialization of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem (Kristin A. Wintersteen, 2021); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); An Imperial Disaster: The Bengal Cyclone of 1876 (Benjamin Kingsbury, 2018); Geographies of City Science: Urban Life and Origin Debates in Late Victorian Dublin (Tanya O’Sullivan, 2019)

American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (John Krige, 2006); Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Ann Laura Stoler, 2002); Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire (Faisal H. Husain, 2021);

The Sanitation of Brazil: Nation, State, and Public Health, 1889-1930 (Gilberto Hochman, 2016); The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia (James Hevia); Japan’s Empire of Birds: Aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and Transwar Ornithology (Annika A. Culver, 2022)

Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation (Jose E. Martinez, 2021); Sound Relations: Native Ways of Doing Music History in Alaska (Jessica Bissette Perea, 2021); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Andrew Zimmerman, 2001)

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Multiple authors, 2016); The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (Katherine Johnston, 2022); Seeking the American Tropics: South Florida’s Early Naturalists (James A. Kushlan, 2020); The Postwar Origins of the Global Environment: How the United Nations Built Spaceship Earth (Perrin Selcer, 2018)

The Colonial Life of Pharmaceuticals: Medicines and Modernity in Vietnam (Laurence Monnais); Quinoa: Food Politics and Agrarian Life in the Andean Highlands (Linda J. Seligmann, 2023) ; Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, 2017); Spawning Modern Fish: Transnational Comparison in the Making of Japanese Salmon (Heather Ann Swanson, 2022); Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Mark Bassin, 2000); The Usufructuary Ethos: Power, Politics, and Environment in the Long Eighteenth Century (Erin Drew, 2022)

Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures (Anita Mannur, 2022); On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, 1830-1890 (Philip Gooding, 2022); All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation Through Species Acclimitization, from Colonial Australia to the World (Pete Minard, 2019)

Practical Matter: Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687-1851 (Margaret Jacob and Larry Stewart); Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Setller Colonialism (Jarrod Hore, 2022); Timber and Forestry in Qing China: Sustaining the Market (Meng Zhang, 2021); The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (David A. Chang);

Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (Christine Keiner); Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire (Mauro Jose Caraccioli); Two Years below the Horn: Operation Tabarin, Field Science, and Antarctic Sovereignty, 1944-1946 (Andrew Taylor, 2017); Mapping Water in Dominica: Enslavement and Environment under Colonialism (Mark W. Hauser, 2021)

To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire (Jason Smith, 2018); Fir and Empire: The Transformation of Forests in Early Modern China (Ian Matthew Miller, 2020); Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500-1950 (Sandra Swart and Greg Bankoff, 2007)

Science on the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya (Lachlan Fleetwood, 2022); Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i (John Ryan Fisher, 2017); Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

An Ecology of Knowledges: Fear, Love, and Technoscience in Guatemalan Forest Conservation (Micha Rahder, 2020); Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Debjani Bhattacharyya, 2018); Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka); Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity (Ann Elias, 2019); Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (Angela Thompsell, 2015)

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to nerd out for a few minutes here:

In his interview with Drumeo II said about the process of coming up with drum parts for the music:

“Most, if not, all of the time, I try to pay close attention to the vocals and figure out any specific syllables that can benefit from accents on the kit. I sometimes use the vocal line as a guide of sorts to dance in between what's being sung to. Filling in those gaps. Typically speaking, songs don't start from a particular drum part. Although, this isn't necessarily deliberate. Another element I look for when writing are any specific syncopations that the drums must match. This could be a pattern on the guitar, a breakdown of some sorts or something electronic. But I feel this takes away a lot of the guesswork when initially writing parts and provides me with a clearer idea of the song in question.”

This made me think of something.

I once saw a video by Adam Neely. It was about something in American Hip Hop Music called “scotch snaps”.

The way that we speak has something to do with the music that we write.

Here is some science stuff about what I mean. I took that from Adam's video which I will link.

This rhythm of a metrically accented sixteenth note followed by a dotted eighth note has a name. It's called the scotch snap, named because of its use in traditional Scottish song and dance, as well as the Lallans Scottish accent.

So why is this rhythm showing up so much now in American pop music?

Well, it might have something to do with how Americans speak English.

A foot is a basic unit of rhythm used in language.

A trochee is a foot that has a stressed syllable followed by a weak syllable. So, for example, Teenage, mutant, ninja, turtles. The stressed syllable in this case falls on what we might consider the musical Downbeat. In many dialects of English, the accented syllable is very short. One corpus study suggested that among European languages, English had the highest percentage of patterns with very short stressed syllables, many as short as100 milliseconds.

This number is significant in music making, because a hundred milliseconds corresponds to the length of a sixteenth note at 140 beats per minute. As L.A. Buckner on PBS Sound Field has mentioned, modern trap hip-hop tempos range from about 110 beats per minute to 140 beats per minute. So what this means is that by using the cadences of certain English trochees, we will naturally, in fact, tap trap rap Scotch snaps.

Now, the average distance between short and long sounds in a given dialect can be measured by something called the Normalized Pairwise Variability Index, otherwise known as the NPVI.

We alternate very quickly between short sounds and long sounds. Latin languages with lower NPVI, like Spanish, often use the foot of an Amphibrach, or a stressed syllable placed in between two unstressed syllables. For example, Lo siento, te quiero, el mundo, mañana. The rhythms used in modern Spanish rap follow that pattern, like in the song Mi Gente, which itself is an Amphibrach. (which leads to reageton) It would make sense that the rhythmic characteristics of languages would be reflected in the vocal rhythms of rappers and singers, right?

It just kind of makes sense.

But what's interesting is that those very characteristics might show up also in the music itself.

For example, consider the Dembo drum groove, characteristic to Caribbean-derived Spanish hip-hop and pop music. (reageton)

The English musicologist, Gerald Abraham, would write that the nature of a people's language inevitably affects the nature of its music, not only in obvious and superficial ways, but fundamentally. Some interesting new research has actually backed that up.

One study found that the NPVI of American jazz musicians and their speech patterns was reflected in their musical choices, how quickly they switched between different subdivisions.

Thank you very much Adam Neely.

I love his videos.

youtube

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future."

This summer, let us browse the stacks of the remarkable life and career of archivist, collector, and curator Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (the "Father Of Black History"), without whom there almost certainly would not have been a Harlem Renaissance. Born in 1874 Puerto Rico to a black mother (from the Virgin Islands) and a Puerto Rican father of German ancestry (hence his distinctive surname), Schomburg recounted a childhood tale of a bigoted grade school teacher in San Juan, who asserted that black people had "no history, art or culture." He moved to New York City in his teens but he never forgot this racist sentiment, and he remained fiercely connected to his Puerto Rican heritage. Activism called to Arturo early; in 1892 he was deeply involved with Las Dos Antillas, an advocacy group that pushed for Puerto Rican independence from Spain --a mission which of course sputtered to a disillusioning end after Spain ceded Puerto Rico to the United States.

Schomburg pivoted to academic life and embarked on a study of the African Diaspora. In 1911 he co-founded the Negro Society for Historical Research, a long-term reclamation project in which materials on Africa and its Diaspora were collected. Schomburg would devote the next 20 years of his life to this project --travelling throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America to rare book stores, antique dealers, and even used furniture stores (one from which he apocryphally claimed to have recovered a handwritten essay by Frederick Douglass). Over time he and his team of African, Caribbean, and African American scholars would amass a collection of over 10,000 books, manuscripts, artwork, photographs, newspapers, periodicals, pamphlets, and even sheet music. One of his proudest finds was a long-forgotten series of poems by Phillis Wheatley.

Of course as any curator will tell you, acquiring unique pieces is nothing without a means to share the knowledge and the history that comes with them --by 1930 (the year of his eventual retirement), Schomberg would have lent numerous items to schools, libraries, and conferences and organized exhibitions. In the midst of all this he wrote articles for a wide range of publications, to include Marcus Garvey's Negro World; the NAACP's The Crisis (edited by W. E. B. Du Bois), and A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen's The Messenger; as well as essays for the National Urban League and The Amsterdam News (Harlem's newspaper).

Significantly in 1926 the Carnegie Corporation bought Schomburg's collection for $10,000 (about $125,000 in today's currency), on behalf of The New York Public Library. The collection was added to the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints of the Harlem Branch on 135th Street, of which Schomburg would later be appointed curator (following a stint as curator of the Negro Collection at Fisk University). The Division became the "go-to" centerpiece of many a Black artist, writer, and scholar; to include Arna Wendell Bontemps and Zora Neale Huston. After his death in 1938, the Division was renamed the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature, History and Prints. Schomberg's protégé, an up-and-coming author and poet named Langston Hughes, assumed responsibility for the collection.

Today the collection is known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (still under the auspices of The New York Public Library) --now topping out at more than 11 million indexed items, and considered to be one of the world's foremost research centers on Africa and the African Diaspora.

#blacklivesmatter#dothework#teachtruth#history detective#new york public library#arturo alfonso schomburg#harlem renaissance

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milford Graves, Arthur Doyle, Hugh Glover — Children of the Forest (Black Editions)

Children of the Forest by Milford Graves, Arthur Doyle, Hugh Glover

Drummer Milford Graves rarely recorded during his lifetime, and, until recently, most of his releases were long out of print. Corbett vs. Dempsey began to rectify that with key reissues of Bäbi, his trio with reed players Arthur Doyle and Hugh Glover, and The Complete Yale Concert 1966, his duos with Don Pullen. TUM records stepped in with Wadada Leo Smith’s Sacred Ceremonies, a 3 CD set including an incendiary duo with Graves along with a trio with Graves and bassist Bill Laswell. Since his death in February, 2021 Black Editions Archive has stepped up the game, digging in to Graves’ vaults, first with an issue of a trio set by Peter Brötzmann, Milford Graves, William Parker, and now, with Children of the Forest, a set of recordings captured in Graves’ Queens workshop with Doyle and Glover in the months leading up to the Bäbi session. The two-LP set documents a January 1976 duo session with Graves along with Glover on tenor saxophone, a brief drum solo from February of that year and a March trio session with Graves, Glover on klaxon, percussion and vaccine (a Haitian one-note trumpet) and Doyle on tenor saxophone and flute. The torrid rawness of these recordings looks toward the torrential barrage of Bäbi but brings out a more ritualistic edge to the playing.

Graves had spent his early years studying African drumming, tablas and playing timbales in Latin jazz bands and that sense of time, extended from African and Caribbean ceremonial music and ritual imbue these sessions. Hugh Glover talks about this and the time he spent with Graves, whom he refers to as Prof, in the extensive interview included with the LP set conducted by Jake Meginsky. “We were listening to the music of the peoples of the interior forest of the Congo… First, the Prof’s mood sets up a tribal-like atmosphere. It’s Congo-like — possession states. The rhythms, I think they immediately stimulated the need to dance… The next thing one must know and be aware of is that Milford Graves, he is not a time-keeping drummer like most jazz drummers. Prof represents the epitome of traditional hand drumming. I’m talking about ceremonial music and ritualistic sounds most familiar with divination.”

Hugh Glover only recorded a few times so the January duo session with him and Graves is a particular find. The first of the four improvisations starts out with the percussionist’s churning thunder, leading to the entry of the tenor player’s hoarse, braying cries. The two had known each other for a decade at that point and Glover had been part of a European tour of Graves’ quartet along with Joe Rigby and Arthur Williams. That symbiosis is immediately evident. There’s a fluid sense of polyphony and elastic polyrhythms at play as the two bound along with ebullient intensity. The music is charged with open, spontaneous interchange and while the intensity level is high, they never overpower each other. Graves’ percussion work is revelatory here, spilling across his kit with a limber, propulsive dynamism. One can hear the legacy of African and Latin American rhythms exploded out with the drummer’s lithe control of tuned skin and slashing cymbals, with masterful control of dynamics and timbre. The inclusion of a short, 2-minute recording from the session reveals their careful attention to detail as the two sound-check the room and their balance and then charge into a compact give-and-take. Their concluding 7-minute improvisation is a particular highlight as they ebb and flow with synchronous fervor.

The inclusion of a three-minute drum solo, recorded in February, is a brilliant addition to the set, particularly since Graves didn’t release any solo recordings until his two discs on Tzadik that came out in the late 1990s. On this 1976 recording, Graves distills his unified, multi-limbed attack into a roiling tempest of energy. Each thundering salvo, each cymbal crash, each resounding wallop of the bass drum is meted out with focus and intention. Glover remarks that listening to the solo recording he was struck by “the melody, and the melody of the tones that he gets, the way he rocks from one melody pitch to another. It has always been a mystery to me how Cuban drummers in Bata were able to modulate the rhythm and the meter. Well, it takes more than one player to do it Cuban style. Prof shows you can do it as one player.”

The three March improvisations with Graves, Glover, and Arthur Doyle provide a notable link in the trajectory toward the session recorded a few weeks later that would be released as Bäbi. Glover reminisces about the March session here, noting “When we played, though, Doyle and I, we weren’t thinking of BÄBI [a name Graves used for his conceptual approach to improvisation]. We were thinking of… well I know I was thing of, and I’m pretty sure he was thinking, how do we keep up with Prof!” While that may have been going through their minds, that uncertainty never reveals itself in their playing. Graves begins the 12-minute improvisation that opens the set with tuned cascades of rim shots and toms and the two quickly join in, with Doyle’s raspy tenor crying out against the shifting percussion. The modulating rhythms and meters of Graves’ solo are the foundation of the buzzing whorls that develop in three-way, spontaneous orchestration which never flags for a moment. The shorter second piece kicks off with an extended section of chattering drums, making way for the two partners to interject barking, ecstatic exclamations that mount with intensity as Graves hurtles in with clanging cowbell. The final piece is the most abstracted, with Doyle’s high-pitched flute skirling against the chafed yawp of Glover’s klaxon and Graves’ coursing flow. Here, improvisation and ritual are melded together with pelting focus.

Glover concludes his interview reminiscing that “It was like Prof was saying, there is no ensemble, there is no musical configuration that I can’t play with as long as I’m allowed to play what I want to play. In other words, his confidence factor was like, I know I have the essence of where any group wants to go. If they allow me to do my thing, I’ll take them there.” The sessions released on Children of the Forest are a fitting testament to that belief and provide a welcome addition to the documentation of the lineage of Graves’ musical legacy. Here's to hoping that Black Editions continues to mine the Prof’s archives.

Michael Rosenstein

#milford graves#arthur doyle#hugh glover#children of the forest#black editions#michael rosenstein#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#free jazz#eremite records

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

is that yaya dacosta? oh, no, that’s marisol souza, a fourty two year old owner of casablanca blooms & coffee who uses she/her pronouns. they currently live in casablanca, and the character they identify with most is olivia benson from law and order: svu. hopefully they find their own little paradise here in el país de los poetas!

basics.

full name: marisol souza

nicknames: mari, soul, mars

age: fourty two

zodiac: scorpio

birthday: october 28th, 1981

birthplace: new york city, new york

ethnicity: afro-latina

orientation: biromantic / bisexual

education: graduated from brown university; majored in business, minored in latin american and caribbean studies

occupation: owner of casablanca blooms & coffee

height: 5'8"

eyes: brown

piercings: standard lobes

languages: english, spanish, portuguese, french

family.

robert souza (father/alive)

adriana andrade-souza (mother/alive)

one (1) older brother (alive)

one (1) younger sister (alive)

child of marisol (child/alive)

background.

marisol was raised in new york city, the place where her parents had immigrated to when they were younger. hard and almost unachievable expectations were set for their oldest girl, so from the start she was forced towards excellence. as marisol grew older and proved to her parents that she was smart enough that she was able to get into any college that she wanted they eased up on her. as the rules were less strict, she also began to let loose more. however when she graduated highschool, she was one of the top students in her class.

tw pregnancy/ fresh into college, it was her first time away from home. college was great for her. she flourished socially, started picking up new hobbies, and even found a part time job at a local coffee shop. halfway throughout her college career she had went to a party that ended up changing her life. while this wasn't her first party it would be the last one that she would attend for while. a couple of weeks after she had started feeling sick and lethargic. marisol didn't think anything of it until she had missed a period. at twenty and almost two years of school left this was the last thing she wanted to deal with.

tw pregnancy and adoption/ once marisol had worked through her own emotions about the situation, she had told her parents and they gave her two options, have the child or give the baby up for adoption. and not wanting to disappoint her parents she gave the baby up, she had an open adoption, hoping to give her baby a better life than marisol could provide as a twenty year old. she always hoped to hear from them, but it's been radio silence since.

marisol kept her head down throughout the rest of college and finished her last two years finally graduating. after graduation she felt almost lost, she was unsure of what to do after coming back home to her parents. she worked in office positions on and off for five years. anytime she left the 9-5 office job the lectures from her parents started and were repeated every time they saw each other.

the pressure from her parents had pushed her to start looking into moving away from home. on her twenty seventh birthday she told her parents that she was moving to chile. while they were sad to see marisol go they were happy that she was going to experience traveling the world and living abroad, just as they had done when they were just a tad younger.

marisol left for chile a month after telling everyone back home. she cried when her closest friends drove her off to the airport and saw her off. when she got settled in her new home, she struggled finding anything that she could do with her degree, so she went back to what she knew from her part time job. finding casablanca blooms and coffee starting as a barista she put in the hours and finally started feeling like she had found her purpose.

after fifteen years of living in chile she fell in love with the city, fell in love with her job. she had gained ownership of the coffee and floral shop that she had started her career at. marisol was never disappointed in her life in the city and calls valparaiso her home.

wanted connections.

siblings: like stated in the family bio she has an older brother and a younger sister.

child: as stated above she had her child when she was twenty so they would be 22/23. they were given up for adoption so they wouldn't have a strong relationship. as long as the fc is at least half black anyone would be fine!

baby daddy: would be around the same age. would have gone to the same univeristy or at least going to the college parties. they could have kept in contact as friends or separated ways after school. open to any fc for this.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some foreign leaders are slamming Washington for planning to exclude three adversarial, non-democratic regimes — Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua — from the gathering, and threatening not to show up themselves. [...]

The critics include Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. On a visit to Cuba this month, he slammed the U.S. sanctions on the communist-led island and said he would urge Biden to invite Havana to the summit. He later said that if all the countries in the region were not invited, he personally would not attend the summit and send a representative instead. [...]

On Tuesday afternoon, Reuters reported that Brazilian leader Jair Bolsonaro, who has often been at odds with the United States, planned to skip the summit, too. [...]

Antigua and Barbuda’s ambassador to the United States warned late last month that leaders from most Caribbean Community countries won’t bother to show up to the summit if Cuba is excluded. [...]

“It’s basically the Biden administration’s best chance to lay out their vision for Latin America, and it might be one of their last chances,” said Ryan Berg, an analyst with the Center for Strategic and International Studies. [...]

Latin American leaders want Biden to unveil new investment and financial support for their countries, but having seen little emerge so far, some are instead turning to Beijing, analysts and former U.S. officials said.

“The real risk is that — after nearly three decades of summitry — this year’s event may be interpreted as a gravestone on U.S. influence in the region,”

11 May 22

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

professional organizations for classics

this is by no means a comprehensive list of every Classics-oriented professional society in the world, but it's a pretty sizeable list. google around and see if you can find more that suit your interests! as you can tell from this list, theres a society or organization for practically every subfield within Classics. a lot of these societies also offer scholarships and grants.

based on my experience as an american, most of these are going to be based in the US; any that are international or outside the US will be indicated in blue. each state also typically has its own state-wide association (i know california has two distinct associations for different part of the state and new york has several, with some of them specifically geared toward NYC.

General Organizations

Society for Classical Studies (SCS)- one of the biggest Classical Studies organizations in the world, a catch-all for all subfields of Classical Studies and Classical Archaeology (including but not limited to Mediterranean prehistory, late antiquity, early medievalism, Near Eastern Studies, etc.) *INTERNATIONAL*

Classical Association of the Middle West and South (CAMWS)- the largest regional North American Classical organization (31 US states and 3 Canadian territories are included, divided into smaller subregions) *US & CANADA*

Classical Association of New England (CANE)- New England region Classical Association

Classical Association of the Atlantic States (CAAS)- Atlantic states (Virginia, Maryland, etc.) region Classical Association

Classical Association of the Pacific Northwest (CAPN)- Pacific Northwestern states and Canadian provinces region Classical Association *US & CANADA*

American Classical League (ACL)- a lot like SCS but not as prominent and restricted to the USA

Eta Sigma Phi- honor society for undergraduates; you can apply for scholarships for up to 8 years after graduating from your undergrad

Digital Classics Association- an organization focused on the teaching and study of Classics through digital media

Classical Association of Canada- like SCS and ACL but specifically for Canada *CANADA*

The Classical Association- like SCS and ACL but specifically for Great Britain *GREAT BRITAIN*

Hesperides: Classics in the Luso-Hispanic World- an organization focusing on the study of Greco-Roman influence outside of the normal geographic constraints (i.e., the Americas, Caribbean, Pacific, etc.) with an emphasis on underrepresented voices in the field including Hispanic, Indigenous, and African descent; website available in English, Spanish, and Portuguese *INTERNATIONAL*

Language & Author-Specific Organizations

International Ovidian Society *INTERNATIONAL*

Vergilian Society

American Association for Neo-Latin Studies (AANLS)

American Society of Greek and Latin Epigraphy (ASGLE)

International Society for Neoplatonic Studies (ISNS)

Society for the Oral Reading of Greek and Latin Literature

Minority Identity Organizations

Classics and Social Justice- not an organization, but an extremely helpful and important resource for Classicists who are not content with the current social and political climate and want to work towards change

Women's Classical Caucus (WCC)- affiliate organization of the SCS focusing on women's and gender studies in the Ancient Mediterranean

Mountaintop Coalition- a relatively new organization focusing on the professional advancement of students and scholars of the Ancient Mediterranean and its reception who identify with an underrepresented ethnic minority

Lambda Classical Caucus (LCC)- an organization for queer Classicists and allies

Eos- a relatively new organization focusing on Africana and Africana Reception Studies

Asian and Asian American Classical Caucus (AAACC)- an organization focusing on the promotion of scholarship by Asian and Asian-American Classicists

Multiculturalism, Race, and Ethnicity in Classics Consortium (MRECC)- an organization focusing on the teaching of race and ethnicity in ancient cultures, as well as sensitivity to those subjects in modern scholarship

Archaeological Organizations

Archaeological Institute of America (AIA)- the largest archaeological organization in the US and a sister organization to SCS; not limited to Classical archaeology *significant international presence*

American Society of Papyrologists

American Friends of Herculaneum (AFoH)- an organization focusing solely on the study of the archaeological site of Herculaneum

Etruscan Foundation- an organization dedicated to the study of Etruria

Historical & Religious History Organizations

Association for Ancient Historians (AAH)

Society for Ancient Medicine and Pharmacology

Society for Late Antiquity

Society for Ancient Mediterranean Religions (SAMR)

Society for Early Modern Classical Reception (SEMCR)

MOISA: International Society for Ancient Greek & Roman Music and Its Heritage

Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy

Schools

Most European countries have their own Schools in Rome and Athens, which may offer membership and scholarship opportunities.

American Academy in Rome

American School of Classical Studies at Athens

College Year in Athens

Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies in Rome

Padeia Institute

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think it’s funny how rowling placed mexico with the rest of north america and the entirety of latin america except mexico in the same school.

in truth, being brazilian myself and an avid observer of geography and statistics; it’s more likely that brazil (not mexico but correlated) would have its own wizarding school, perhaps gathering students from the entire portuguese speaking world (portugal, mozambique and angola specifically), and it wouldn’t be located in the amazon, that’s for sure. who the hell wants to study magic being bitten by mosquitoes all the time? the southern or southeastern highlands are more likely to me. deep minas gerais state sounds just perfect, and very brazilian. and the castle itself would look nothing like an aztec temple or something, but rather like this.

brazil is very much isolated from the rest of latin america, to the extent brazilians ourselves often don’t know we’re classified as latinos by americans and europeans. the language barrier and the sheer size of our country (given it wasn’t broken in 20 different countries like hispanic america) makes isolationism quite easy and so we don’t mingle with the rest of latin america as much.

thus, the rest of latin america (and the caribbean possibly, though i quite like the idea of a jamaican school) would have its own wizarding school, which i imagine could be located in the andes or the mexican highlands. the andes sound just perfect though - isolated and its climate is cool enough for studying. since rowling herself didn’t imagine a hispanic american wizarding school, i can’t google it for cool fan arts. (also given that the andes and the mexican highlands were both the seats of the two largest empires in pre-columbian america, they could after all have their own separate wizarding schools; the andean one serving students from southern latin america and the mexican one from northern)

and the u.s. would still have its own school along with canada. canada just gets dragged along all the time anyways. though some students could choose the french school i guess?

imo rowling just got lazy when designing the rest of the wizarding... globe. it makes no sense that the british isles would have its own school but all of europe gets lumped together and the same for latin america or asia & oceania. and let me not get started about the names. “castelobruxo” is a lazily anglicised way to spell “witching castle” in portuguese, and sounds nothing like a real place name. “castelo de magia” (magic castle or something) would make more sense if she wants to be plain. but since hogwarts (warts on hogs??) doesn’t sound anything close to normal in english i imagine a portuguese name for a wizarding school would also sound alien. if she did it for hogwarts, she could do it for us.

unfortunately harry potter suffers from lazy worldbuilding outside of the british isles. i guess rowling’s behavior in the last few years makes suspension of disbelief a little bit harder is all.

#harry potter#worldbuilding#ritalin.txt#listen rowling wasn't autisti enough for worldbuilding is what i'm getting at#i'm 100% sure tolkien and martin are neurodivergent#neurotypicals can't do this stuff#yes i'm flexing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nicola Conte - Umoja - the host of musicians on his new album take his sound even closer to the ideal of 70s-era soul-jazz

Renowned Italian spiritual jazz master, DJ, producer, guitarist, and bandleader Nicola Conte proudly presents his new album Umoja via London based label Far Out Recordings.

A joyous exultation across ten tracks, Umoja taps into the abundant well of knowledge Conte has amassed over his career as connoisseuring compiler and archivist of deep jazz, latin, afrofuturist, bossa-nova and soul music from around the world. Expressing unity, oneness and harmony in Swahili, Umoja coalesces universal feelings through the multifaceted global music Conte has spent his life studying and researching.

The music of Umoja draws on the deep-dug 70's independent spiritual and free jazz sounds, private-press soul records, and African and Afro Caribbean rhythms in Conte’s collection. But he equally recognises his debt to many of the decade’s more celebrated musical icons, such as North American cosmic jazz masters Lonnie Liston Smith and Gary Bartz, and Afrobeat originators Fela Kuti and Tony Allen.

Proudly revivalist, Umoja was recorded direct to analog tape, with just two takes for each track. “Searching for an unadulterated, spontaneous, almost improvised feeling”, Nicola made sure that the few overdubs were also transferred to tape in order to retain the colour and warmth of the analog sound. “Very little post production or editing has been added, so what you hear is largely what happened in those magical live sessions”.

Zara Mcfarlane - Lead Vocals On Arise/life Forces/freedom & Progress

Bridgette Amofah - Lead Vocals On Dance Of Love & Peace/soul Of The People/flying Circles

Myles Sanko - Lead Vocals On Into The Light Of Love

Timo Lassy - Tenor Saxophone

Teppo Makynen - Drums

Pietro Lussu - Fender Rhodes , Wurlizter, Acoustic Piano

Alberto Parmegiani - Guitar

Abdissa Assefa - Congas & Percussions

Ameen Salim - Fender Bass & Double Bass On Freedom & Progress/Flying Circles/Umoja Unity

Marco Bardoscia - Electric Bass On Dance Of Love & Peace/Arise/Life Forces

Luca Alemanno - Fender Bass & Double Bass On Soul Of The People/Heritage/Into The Light Of Love

Simon Moullier - Vibraphone On Arise/Heritage

Dario Bassolino - Fender Rhodes Piano & Moog On Soul Of The People/Into The Light Of Love

Magnus Lindgren - Flute On Into The Light Of Love

Fernando Damon - Drums On Heritage

Milena Jancuric - Flute On Heritage

Pasquale Calo’ - Tenor Saxophone On Flying Circles

Hermon Mehari - Trumpet On Freedom & Progress

Paola Gladys - Vocals On Flying Circles/Freedom & Progress

Chantal Lewis - Vocals On Into The Light Of Love

Jaelee Small - Vocals On Into The Light Of Love

Produced By Nicola Conte

Music Composed By Nicola Conte & Alberto Parmegiani

Except Into The Light Of Love By Conte/Parmegiani/Sanko

Arise By Conte/Parmegiani/Mcfarlane

Soul Of The People By Conte/Parmegiani/Amofah

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazil and Uruguay Vow to Modernize Mercosur, Pursue Trade Deals With EU, China

Members of the customs union Mercosur pledge to ease internal trade and explore new deals abroad.

Trade was high on the agenda of Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s first overseas trip of his term to Argentina and Uruguay this week. The former jaunt included Tuesday’s summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in Buenos Aires.

During Lula’s visit to Argentina on Monday, Brazilian Finance Minister Fernando Haddad announced that a government-owned bank would issue new credit lines for Brazilian companies to export goods to Argentina, and Lula and Argentine President Alberto Fernández announced that the two countries would study a financial mechanism to conduct bilateral trade without converting transactions to U.S. dollars, which Argentina sorely lacks.

While Lula and Fernández referred to this mechanism as a “common currency” in an op-ed last weekend, Haddad has since clarified that the leaders are considering a common unit of account for trade operations rather than a currency that would replace the Brazilian real and Argentine peso.

Then, at the CELAC summit the next day, leaders from center-right Uruguayan President Luis Lacalle Pou to leftist Colombian President Gustavo Petro called for Latin America to trade more internally.

And on Wednesday, during meetings in Uruguay’s capital of Montevideo, Lula proposed talks on “modernizing” the Mercosur customs union, an “urgent” approval to its draft trade deal with the European Union, and subsequent exploration a free trade agreement with China. Mercosur’s rules prohibit any one of its members—Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay (Venezuela is suspended)—from making trade agreements without the others’ consent, but Lacalle Pou has been studying the possibility of an independent bilateral trade deal between Montevideo and Beijing.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#brazilian politics#uruguay#uruguayan politics#economy#foreign policy#mercosur#international politics#europe#china#european union#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

At this point I should just be jobless and major in latin american/caribbean studies and do my studies in on the jibaros of puerto rico or immigration of asians and europeans to the islands

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nestor Miguel Torres (born April 25, 1957) a virtuoso technician Classical, jazz, and composer was born in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico to Nestor Torres Sr., pianist and vibraphone, and Ana E. Salcedo Baldovino-Torres. He skipped two grades, began flute studies at 12, and began studies at Interamerican University. He took classes at the New England Conservatory of Music. He received a BSM from Berklee College of Music at the age of 16. He received an Artist Diploma from the Mannes School of Music.

He performed with the Florida Philharmonic Orchestra and the New World Symphony. He appeared in Cachao: Como su ritmo no hay dos. He released the album, Burning Whispers, which sold more than 50,000 copies.

He married Patricia San Pedro (2002). He was a central attraction at Connecticut’s Greater Hartford Festival of Jazz. Mayor Eddie Perez proclaimed August 19, 2004, as “Nestor Torres Day” with two concerts at Hartford’s Keney Park and Arch Street Tavern.

He played at the World Music Concert during One World Week at the University of Warwick. At the 51st Annual Grammy Awards, he was nominated for “Best Latin Jazz Album Nouveau Latino.

He played at the Herbst Theatre in the San Francisco Civic Center where he performed “Tango Meets Jazz.” He performed at the 21st Central American and Caribbean Games in Mayagüez, Puerto and presented his composition “Saint Peter’s Prayer” for the Dalai Lama at Miami Beach’s Temple Emanu-El. He became the founding director of the Florida International University’s first charanga ensemble, made up of winds, strings, and percussion instruments used to perform traditional and modern versions of folk music from the Caribbean and especially Cuba.

He premiered his composition “Successors” for the concert, “Voices of the Future ” performed with the Miami Children’s Chorus at the New World Center on Miami Beach. In 2017, he released his first album of Latin American classical flute music, Del Caribe, Soy!

His music is a crossover fusion of Latin, Classical, Jazz, and Pop sounds. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Hofstra University

Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and the Latin American and Caribbean Studies Program

presents

GREAT HISPANIC WRITERS SERIES

Poetry Reading and Dialogue with Lila Zemborain and Víctor Rodríguez Núñez

Two fundamental Latin American poets of today, Lila Zemborain (Argentina) and Victor Rodriguez Nunez (Cuba), will read their poetry in a bilingual format. During this session they will hold a dialogue about contemporary Latin American poetry with Professor Miguel Angel Zapata. Lila Zemborain is a professor in New York University’s Spanish Creative Writing program and has recently published Matrix Lux. Collected poetry (1989-2019). Victor Rodriguez Núñez is a professor of Spanish at Kenyon College. One of his most recent books is La luna según masao vicente (2021).

Thursday, April 25, 1-2:25 p.m. 246 East Library Wing, Axinn Library, First Floor, South Campus

This event is FREE and open to the public. Advanced registration is required. More info and to RSVP visit https://tinyurl.com/mss4brht

0 notes

Text

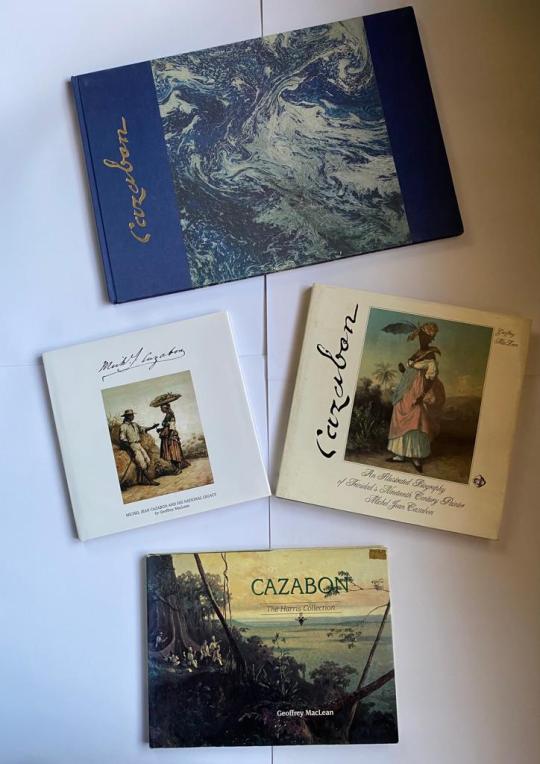

Sexypink - A huge loss to Trinidad and Tobago. Thank you Geoffrey for your vision, kindness and love.

..............................

Geoffrey's contribution to Art history. He was the definitive writer on Cazabon.

An image of one of Cazabon's paintings.

Finally, a beautiful tribute to Geoffrey MacLean from one of many friends.

.................................

TRIBUTE TO GEOFFREY MACLEAN. In each island nation of the Eastern Caribbean, economies of scale make it so that there are only one or two (and if they are lucky, three or four) local experts in some field of study which has little to do with industry or clerical work but everything to do with the national character and its history. Because they are often without precedent, these experts often have had to travel abroad for their training or are otherwise self-trained in their chosen sector of the liberal arts/humanities/social sciences.

Trained architect and avocational art historian Geoffrey MacLean was one of these indispensable sages in the field of visual studies and the built environment. He was the world’s foremost specialist on nineteenth-century landscape and genre painter Michel Jean Cazabon. Cazabon was a partially unwitting member of a global late colonial/early post-colonial landscape painting tradition that encompassed artists such as Mexican José María Velasco, the Chartrand brothers of Cuba, Filipino painter Fernando Amorsolo, and the painters of the Hudson River School in the United States. What all of these artists had in common was their urgent need to capture and pay tribute for posterity to the natural beauty of their respective lands before that “Edenic” verdure was despoiled by then-already encroaching industrialization.

MacLean’s passion for Cazabon pressed him not only to hone further the scholastic abilities he had already developed at Presentation College in his native Trinidad and Bristol University in the U.K. but to travel back and forth between the Caribbean and Europe hunting down examples and collections of Cazabon’s work. He also assisted the government of the Republic of Trinidad & Tobago in the acquisition of some Cazabon works for display in its National Museum and Art Gallery.

MacLean was generous with his knowledge, his time, and with his published materials. Every time I visited him, I came home with an armful of books and catalogues (one of my favorites is an unassuming little pamphlet of a catalogue called Chinese Artists of Trinidad & Tobago which probably played some part in my decision to write the book about Sybil Atteck on which I am currently working with Sybil’s nephew Keith). In graduate school, I relied heavily on MacLean’s Cazabon books for the research I was doing on colonial Latin American and Caribbean painting. MacLean’s enthusiasm for Cazabon’s genre painting, especially his rapt verbal and written descriptions of the late 19th century painting Negress in Gala Dress (pictured here) revealed to me that Cazabon’s paintings of local “types” (e.g., “Negress” instead of named individual) was sometimes a form of real portraiture and thus departed the tipo de país-to-costumbrismo continuum that we sometimes use in Latin American art history. Cazabon loved his people too much and included too much implied biography and other narratives in those paintings, to reduce their subjects to mere “types.” His titles were thus deceptively taxonomic.

Architect, scholar, art gallery director Geoffrey MacLean’s contribution to the study and preservation of T&T’s architecture was legendary even before his passing. He has searched out original plans for fretwork houses and saved some of these architectural jewels from the bulldozers of “developers.” He has done the same for members of the Magnificent Seven around the Queen’s Park Savannah and taught workshops on both the civic and residential architecture of Trinidad & Tobago. As MacLean himself now passes into legend, we are left with the perennial question in these small and mid-sized islands of the Eastern Caribbean each with their two or three experts on local art and architecture – who will pick up the torch?

~ Lawrence Waldron

#galleryyuhself/Geoffrey MacLean#galleryyuhself/publisher/gallery owner/architect#galleryyuhself/bereavement#galleryyuhself/medulla gallery#tumblr/aquarella gallery#tumblr/cazabon books#tumblr/architect#trinidad and tobago#Geoffrey MacLean#architect#visionary#gallery owner

0 notes

Text

let us improve the condition of poor and needy without becoming RADICLE ROBIN HOODS who voilently loot and destroy society to help others

https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/ecuador-detains-12-people-including-judges-organized-crime-investigation-2024-03-04/

“ It is a battle that will change the whole system,” said Jimmy “Barbeque” Cherizier, a former police officer who styles himself as Robin Hood figure in his territory.

https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/12/18/latin-america-can-boost-economic-growth-by-reducing-crime

👇🏻

"although slavery was a worldwide institution for thousands of years, nowhere in the world was slavery a controversial issue prior to the 18th century. People of every race and color were enslaved – and enslaved others.

White people were still being bought and sold as slaves in the Ottoman Empire, decades after American blacks were freed.

Everyone hated the idea of being a slave but few had any qualms about enslaving others. Slavery was just not an issue, not even among intellectuals, much less among political leaders, until the 18th century – and then it was an issue only in Western civilization."

Only after INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION in Europe people in there started UNIVERSAL EDUCATION so that they get EDUCATED / SKILLED LABOUR . Before that most societies in the world kept the poor uneducated and socially backward Slavery exploitation is an evil which has been prevalent from ancient times in most of the societies

0 notes