#macedonian phalanx

Text

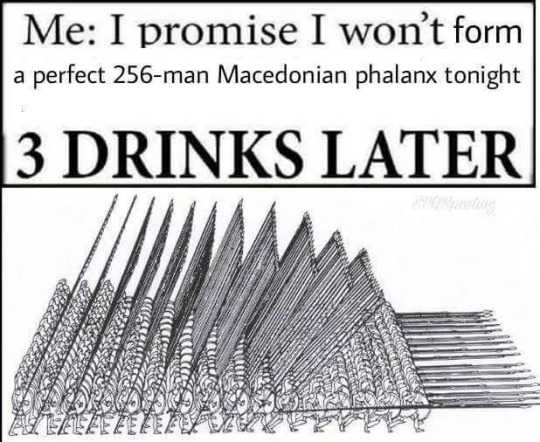

Getting some work done on the Macedonians, going fast and dirty with them for a fun "break" from more intense projects

Works been rough and my car is having a time so a nice repetitive calming exercise like this is nice

#art#canopiancatboyart#painting#miniature#hail caesar#macedonian phalanx#macedonia#alexander of macedon#ancient greece#ancient history#tabletop#miniatures#wargaming#3d printing#board games#miniature painting#greece

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

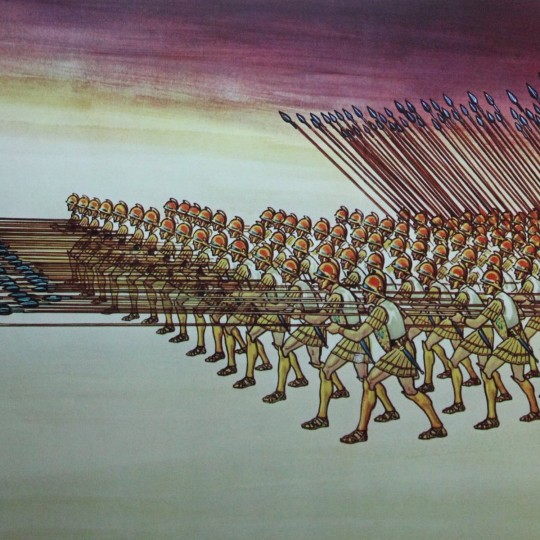

The Battle of Pydna, 168 BC by Peter Connolly

#battle of pydna#art#ancient rome#peter connolly#rome#macedonia#macedon#roman#romans#macedonian#phalanx#pikes#antiquity#roman republic#third macedonian war#greece#history#macedonian wars#ancient greece#perseus#lucius paullus#lucius aemilius paullus#publius cornelius scipio nasica#mediterranean#europe#european

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

some of yous are friends with quilge , but yous also need to pass irys' vibe check ( she rushes you with physical violence ) .

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pezhetairoi

The pezhetairoi (foot companions) were part of the imposing army that accompanied the Macedonian commander Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) when he crossed the Hellespont to face the Persian king Darius III in 334 BCE. Armed with long pikes (sarissas), the pezhetairoi fought in a Greek phalanx formation and played an important role in the battles of the Granicus, Issus, and Gaugamela.

Origin

Like with the hypaspist, the origin and evolution of the pezhetairos (plural: pezhetairoi) are shrouded in mystery. Except for references to them in discussions of Philip II and Alexander, the term pezhetairoi is hardly found in ancient literature. In his The Army of Alexander the Great, historian Stephen English wrote that, at some inexact point, the peasantry was recruited territorially and organized into infantry, and, according to the historian Anaximenes, it was given the name pezhetairoi. He added that the pezhetairoi were "essentially an evolution of the standard phalanx" (3).

However, disagreements still persist: some scholars refer to all of the Macedonian infantry as pezhetairoi while others believe they were not front-line infantry but bodyguards to the king. English contends that the pezhetairoi may have been created as a select, elite infantry acting as royal bodyguards under the Macedonian king Alexander I (498-454 BCE). It is claimed by some that this elite infantry eventually became the hypaspists. It was Alexander III (the Great) who would extend the term pezhetairoi to include all of the heavy phalanx infantry with the exception of the hypaspists.

Continue reading...

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

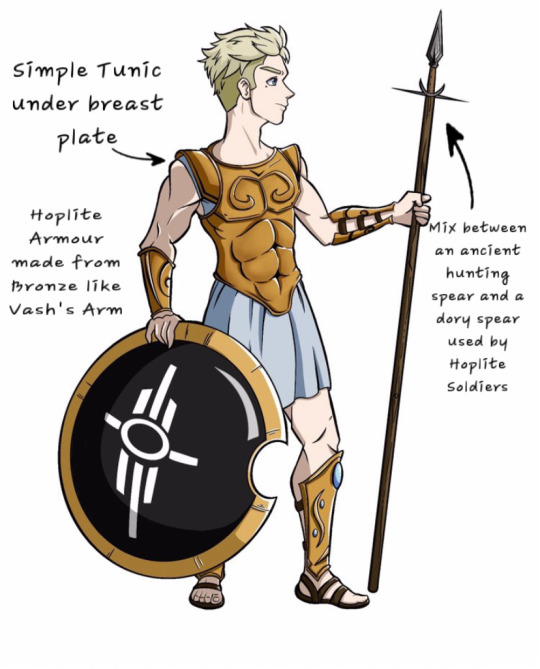

In the Plain of Nysa

Millions Knives

Nai, the God of War

God of War and Vash’s twin brother

Younger brother of Tesla (Goddess of Victory)

Raised by Rem (Goddess of Wisdom)

Based on Ares and partly Demeter

Respected and rather well liked among the other Olympians (except Meryl)

After the death of his sister at the hands of mortal Soldiers during the Trojan war and Vash losing his left arm to the same soldiers, he became fiercely protective/possessive of his twin brother

Some time after the end of the Trojan War he built a giant "cage” under Mt. Olympus and locked Vash inside it for nearly a Millennium.

When any of the other Olympians asked him regarding Vash’s whereabouts he’d tell them his brother was travelling through the mortal realm, which seemed to shut the majority of the other gods up regarding this issue and the Golden Cage beneath their feet remained a secret only he and Vash knew about.

After Vash managed to escape the the golden Cage with the help of Meryl and Roberto, rather than an eternal Winter like Demeter in the Myth of Persephone & Hades, Nai, overcome with rage, created a giant war that would slowly spread across all of ancient Greece.

For more Information/lore about this AU just look at the in the plain of Nysa tag on my page or just send me an ask in my inbox.

As always thanks to my friend Stephan for helping me with this drawing of Nai and this AU in general. Please check out his art on instagram!

Please do not Tag this AU as Plantcest

[More ramblings about Nai’s design under the cut.]

Nai’s Design as you may have gathered is very much based on your typical Greek Hoplite Soldier

He was supposed to also wear a helmet but i was so proud of how the hair had turned out that I did not want to cover it up haha.

Around the time that this story takes place in, classical greece, bronze armours like these had actually fallen out of fashion in favour of iron ones so I just like to think that Nai, being over 1000 years old, is just very traditional or never fully mentally moved on from the Trojan War so he kept his old Bronze Plate Armour all those years while still adopting the newer Hoplite Warfare system (which used spears and Phalanx formations in comparison to the open battle fields and sword fights of the Mycenean Age/the Trojan War)

As for Nai‘s spear, an actual Dory could be up to 4 meters high, especially in the case of Macedonian ones. But making him run around with one of those would be impractical for many reasons as you may assume. The half-moon shaped spikes right underneath the actual Spear‘s spike is the part I stole from ancient greek hunting spears. The point of them was to keep wild animals like boars at a safe distance from you. Because boars, even if you pierce their skull with the actual spear‘s tip would just keep on running towards you even if it meant impaling their own brain on the entire spear Dracula Style. If you look closely you can kind of see it on the Meleager Sarcophagus.

#in the plain of nysa#i am still not that good at art but I am improving I think#vashwood#trigun stampede#trigun#persephone au#trigun 98#nai and vash#nail art#millions knives#knives trigun#millions knives trigun#tristamp vashwoood#tristamp knives#tristamp#vash x wolfwood#vash the stampede#hades and persephone#ares

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Conversely, if you and Alexander talked only once, what do you think he’d ask you? I guess he wouldn’t be surprised to find out there are professors studying his life and reign more than two thousand years after his death - but what do you think he would ask you about the history of, well, himself?

Interesting question. I think it would be difficult for him to know what TO ask. While it’s possible to forecast a little way into the future (science-fiction authors do it all the time), the further into the future we look, the further off-base we get. Unsurprisingly. Things come out of left field that even the most foresighted can’t anticipate.

For Alexander, I do think he realized that he died too soon, and his empire wasn’t established enough yet. Ergo, one of his first questions would likely be, “So, how fast did it all fall apart and who came out on top?”

He might even be weirdly happy to hear the answer. (Not long.) Why? It proved they couldn’t hold it together without him—which underscores his own uniqueness. I realize that’s self-centered on his part, but don’t all of us, deep down, kinda wanna know we’re irreplaceable? How much more for somebody raised in a society where kleos (glory) and timē (public recognition) were so important? An older king might have been more concerned with his “legacy” after ruling for decades. But Alexander was still young. He didn’t have much of a legacy yet to protect, other than his remarkable success. That nobody else could match it would, I think, have pleased him.

Would he have asked about his family? Probably. But I think it’d be part of the larger question of what happened next and who came out on top.

He’d LOVE that Rome named him “the Great.” In his own day, he was known as “the invincible” anikētos; “the Great” is Roman.

Yet I don’t think he’d have seen Rome coming. I expect he’d predict Carthage as the dominant Western power. Remember that, in his day, Rome wasn’t especially notable. This was still the Early Republic. Plebians were relatively new into the Senate, Rome was nowhere near in control of all the peninsula and just starting the shift from a Greek- and Etruscan-style phalanx to what would become the legion.

Reputedly, Alexander of Epiros (before his death in 331) resented Alexander of Macedon’s early successes, claiming he (Alexander of Epiros) was fighting real men in Italy while his nephew “waged a war against women” (e.g, barbarians). That’s a typical Western-centric view.* At the time, however, Persia had the most powerful army in the world. Whatever Livy claimed, had Alexander brought the Macedonian military machine west instead of east, he’d have mowed through Italy, just like in Greece, Thrace, and Illyria. It took another hundred-plus years of Roman military development to result in the wins at Magnesia or Cenoscephalae. Italy/Rome at that point was just no match for Macedon, much less Macedon under Alexander’s command.

But hoo-boy, he’d want to know about the legion, even if he wouldn’t know enough to ask directly. He might ask about future military innovations.

Also…he’d be PISSED that more people in the West today recognize the name of Julius Caesar than Alexander of Macedon. 😉 “Why didn’t Shakespeare write a play about ME???” But he’d be tickled there are more stories about him in more varied world cultures than there are about Caesar (true fact). IOW, Caesar may be more famous in the West, but Alexander is more famous in the larger world (thanks to the Alexander Romance).

Last, he might ask me about my world. If we assume he knew I was 2300+ years in his future, I think he’d naturally want to know what life is like in my time. I mean, wouldn’t we ask what life would be like 2300 years in our future? He’d probably be fascinated by the changes, although perhaps not the ones we’d anticipate.

Long ago, on a drive from Kentucky back to Nebraska, my son and I had a fun conversation about a fictional interview between Alexander and Stephen Colbert (Ian’s favorite talking-head person at the time). Stephen Colbert would ask Alexander what were the three most surprising things he’d found about the future? Would it be medical breakthroughs? Computers? The rise of democratic states? Flying through the air (and into space)? Etc.

Nope. The three things I think would surprise him the most are:

1. Near-instantaneous speed of communication

2. Easy availability of information (even if it may be wrong)

3. Changes in the importance of religion (at least in some places)

It was such an interesting conversation, I turned it into what’s now the opening Power-point in my World History I class! Ha.

————

* This supposed claim of Alexander of Epiros may not even be real. It’s recorded by Roman Cheerleader Livy, where of course the West is more powerful than the weak, decadent Oriental East.

#asks#Alexander the Great#what would Alexander the Great want to know about the future?#Classics#Alexander the Great and Rome#alternate history#Successor Wars

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Complicating this picture further, we have another ethnic category in Ptolemaic armies, that of ‘Persians.’ The Ptolemaic army has a place for most Egyptians, they fight as machimoi, get paid less than ‘Macedonians’ and don’t (usually) serve in the phalanx. But then we have soldiers noted as being ‘Persians.’ These are not, clearly, actual ethnic Persians or any sort of Iranian peoples – there really aren’t any of those in Egypt. Instead ‘Persian’ too is a fictional legal status. Under Alexander, there was briefly a program of training local youths (mostly elites) in Macedonian warfare and customs and the products of these programs were called ‘Persians,’ which fits into Alexander’s other failed efforts to try to fuse his Macedonian ruling-class with a broader Persian (and related peoples) ruling class. While those programs get shut down basically everywhere after Alexander’s death – as his successors instead set up ethnic hierarchies where Macedonians (and Greek-speakers) rule and all other people are ruled – it seems like it ran a little longer in Egypt, producing a class of ethnic Egyptians who were Hellenized in their customs and fighting style and legally coded as ‘Persians.’ In the second century, some number of Egyptians also earned ‘Persian’ status through military service and it seems like several generations in, some of those original ‘Persians’ end up reclassified as ‘Macedonians.’

can only imagine the intensity of the discourse posted by the scribes in Ptolemaic Egypt

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sacred Band of Thebes (Ancient Greek: Ἱερός Λόχος, Hierós Lókhos) was a troop of select soldiers, consisting of 150 pairs of male lovers which formed the elite force of the Theban army in the 4th century BC, ending Spartan domination. Its predominance began with its crucial role in the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC. It was annihilated by Philip II of Macedon in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC.

According to Plutarch, the 300 hand-picked men were chosen by Gorgidas purely for ability and merit, regardless of social class. It was composed of 150 male couples, each pair consisting of an older erastês (ἐραστής, "lover") and a younger erômenos (ἐρώμενος, "beloved"). Athenaeus of Naucratis also records the Sacred Band as being composed of "lovers and their favorites, thus indicating the dignity of the god Eros in that they embrace a glorious death in preference to a dishonorable and reprehensible life", while Polyaenus describes the Sacred Band as being composed of men "devoted to each other by mutual obligations of love".

Defeat came at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), the decisive contest in which Philip II of Macedon, with his son Alexander the Great, extinguished Theban hegemony. The battle is the culmination of Philip's campaign into central Greece in preparation for a war against Persia. It was fought between the Macedonians and their allies and an alliance of Greek city-states led by Athens and Thebes. Diodorus records that the numbers involved for the two armies were more or less equal, both having around 30,000 men and 2,000 cavalry.

The traditional hoplite infantry was no match for the novel long-speared Macedonian phalanx: the Theban army and its allies broke and fled, but the Sacred Band, although surrounded and overwhelmed, refused to surrender. The Thebans of the Sacred Band held their ground and Plutarch records that all 300 fell where they stood beside their last commander, Theagenes. Their defeat at the battle was a significant victory for Philip, since until then, the Sacred Band was regarded as invincible throughout all of Ancient Greece. Plutarch records that Philip II, on encountering the corpses "heaped one upon another", understanding who they were, wept and exclaimed,

Perish any man who suspects that these men either did or suffered anything unseemly.

— Plutarch, Pelopidas 18

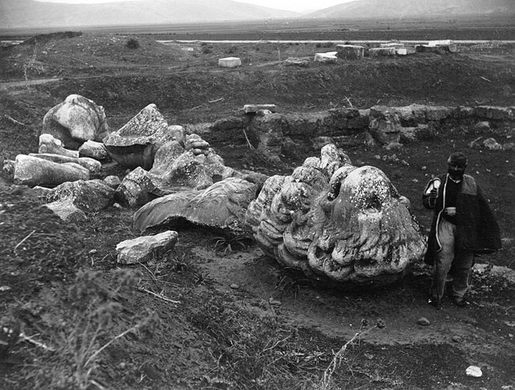

Pausanias in his Description of Greece mentions that the Thebans had erected a gigantic statue of a lion near the village of Chaeronia surmounting the tomb of the Thebans killed in battle against Philip.

In 1818, a British architect named George Ledwell Taylor spent a summer in Greece with two friends at Livadeia. On June 3, they decided to go horseback riding to the nearby village of Chaeronea using Pausanias' Description of Greece as a guidebook. Two hours away from the village, Taylor's horse momentarily stumbled on a piece of marble jutting from the ground. Looking back at the rock, he was struck by its appearance of being sculpted and called for their party to stop. They dismounted and dug at it with their riding-whips, ascertaining that it was indeed sculpture. They enlisted the help of some nearby farmers until they finally uncovered the massive head of a stone lion which they recognized as the same lion mentioned by Pausanias. Parts of the statue had broken off and a good deal of it still remained buried. It was later pieced back together in 1902 after obtaining permission from the Greek government.

In the late 19th century, excavations in the area revealed that the monument stood at the edge of a quadrangular enclosure. The skeletons of 254 men laid out in seven rows were found buried within it. A tumulus near the monument was also identified as the site of the Macedonian polyandrion where the Macedonian dead were cremated. Excavation of the tumulus between 1902 and 1903 by the archeologist Georgios Soteriades confirmed this. At the center of the mound, about 22 ft (6.7 m) deep, was a layer of ashes, charred logs, and bones about 0.75 m (2.5 ft) thick. Recovered among these were vases and coins dated to the 4th century BC. Swords and remarkably long spearheads measuring about 15 in (38 cm) were also discovered, which Soteriades identified as the Macedonian sarissas.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

One might have supposed that the true act of love was to lie together and talk.

— Fires from Heaven by Mary Renault

He talked of man and fate; of words heard in dreams from speaking serpents; of the management of cavalry against infantry and archers; he quoted Homer on heroes, Aristotle on the Universal Mind, and Solon on love; he talked of Persian tactics and the Thracian battle-mind; about his dog that had died, about the beauty of friendship. He plotted the march of Xenophon's Ten Thousand, stage by stage from Babylon to the sea. He retailed the backstairs gossip of the Palace, the staff room and the phalanx, and confided the most secret policies of both his parents. He considered the nature of the soul in life and death, and that of the gods; he talked of Herakles and Dionysus, and how Longing can achieve all things.

Listening in bed, in the lee of mountain crags, in a wood at daybreak; with an arm clasping his waist or a head thrown back, on his shoulder, trying to silence his noisy heart, Hephaistion understood he was being told everything. With pride and awe, with tenderness, torment and guilt, he lost the thread, and fought with himself, and caught the drift again to find something gone past recall. Bewildering treasures were being poured into his hands and slipping through his fingers, while his mind wandered to the blinding trifle of his own desire. At any moment he would be asked what he thought; he was valued as more than a listener. Knowing this he would attend again, and be caught up even against his will; Alexander could transmit imagination as some other could transmit lust. Sometimes, when he was lit up and full of gratitude for being understood, Longing, who has the power to achieve all things, would prompt the right word or touch; he would fetch a profound sigh, dragged up it seemed from the depth of his being, and murmur something in the Macedonian of his childhood; and all would be well, or as well as it could ever be.

#mary renault#the alexander trilogy#fire from heaven#alexander the great#hephaistion#alexander/hephaistion#this book ❤️

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

LizzLove's Gender Preference Kite Redone As Macedonian-Roman Phalanx Shield

I did this for someone over at PlumbBobKeep and thought maybe someone else might want it. Mesh and texture by the awesome Hriveresse from her amazing Titans set.

If you are interested, you may DOWNLOAD

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

What? Tyranids? Why would I be posting tyranids? Clearly my next, most important project was printing a full 256 man Macedonian Phalanx. Historia Civilis binges will do that to you, unfortunately

#wip#art#canopiancatboyart#miniature#tabletop#miniatures#wargaming#3d printing#board games#macedonia#alexander of macedon#macedonian phalanx#ancient history#ancient greece#greece#hail caesar#historia civilis

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

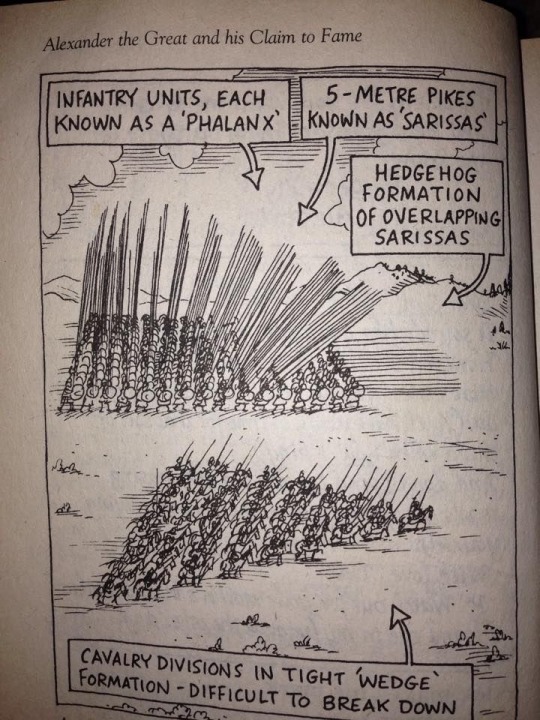

#alexander the great#alexander#macedonian#army#macedon#macedonia#ancient greek#ancient greece#formation#tactics#greece#greek#ancient#cavalry#infantry#pikes#phalanx#sarissas#battle#war#history#europe#european#empire#asia minor

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ptolemaic Gondor?

Tolkien named Ancient Egypt as one of the inspirations for Gondor-particularly aesthetically and in their capacity for grand architecture. The crown of Gondor also resembles the crown of Upper Egypt, tall and conical, with similar symbolism between the combining of the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt and the combination of the Gondorian crown with the Arnorian diadem-the Elendilmir. I think there is also a deeper link between Gondor and Ancient Egypt, particularly Egypt under the Ptolemaic dynasty, the last to rule Egypt before the Romans annexed it.

Under the cut for a brief history of Ptolemaic Egypt and what that has to do with Gondor!

The Ptolemies were descended from one of Alexander the Great’s generals, called, unsurprisingly, Ptolemy. Alexander and his army were from Macedon, a northern Greek kingdom. In the chaos after Alexander’s death his generals carved up his empire, with Ptolemy rushing to Egypt and having himself proclaimed Pharaoh. The Ptolemaic dynasty ruled from Alexandria, a city founded by Alexander in the Nile delta, on the shores of the Mediterranean. Ptolemy was a Macedonian, and many other Macedonians, both soldiers of Alexander and others, followed them to Egypt. Alexandria became a great centre of Greek Hellenic culture dominated by Macedonians, who became basically a ruling class of this new Ptolemaic state. The highest offices of government were reserved for Macedonians, Macedonian Greek was the court language, the military was made up (at first at least) of Macedonians and mercenaries, with no recruitment from the Egyptian population. The traditional Egyptian religion and the role of the Pharaoh within it remained (with some Greek introductions), but in most other things Macedonians and their customs dominated. No Ptolemaic Pharaoh even knew how to speak Egyptian until Cleopatra VII (yes, that’s THE Cleopatra), the last ruler of the dynasty! Even she seems to have done little to better integrate Egyptians and Macedonians, with the Macedonians remaining firmly in charge until the Romans annexed Egypt.

Now the Ptolemies were not the only successors of Alexander, and one of their main rivals were the Seleucid empire, founded by fellow Macedonian general Seleucus. The Ptolemies often fought for control of the Levant in the Syrian wars. During the reign of Ptolemy IV the Ptolemies and Seleucids were embroiled in the fourth Syrian war. Faced with manpower shortages within the Macedonian ruling class, Ptolemy IV’s army included Egyptians trained to fight in the Macedonian style as part of the phalanx. At Raphia, Ptolemy IV won a decisive victory, with the Egyptian troops playing a key role in the battle. While this did improve the lot of Egyptians within Ptolemaic Egypt, Macedonians continued to dominate both the state and the military, and the failure to further integrate Egyptians into the army contributed to the weakening of the Ptolemaic state, which enjoyed arguably its finest hour at Raphia. A succession of poor rulers and civil war would see the state decline, eventually being annexed into the Roman empire after the death of Cleopatra VII.

Now, how does that fit with Gondor?

Gondor was founded by Númenorian exiles, with a Númenorian ruling class. Its main languages are Westron (descended from Númenorian Andunaic) and Sindarin, a common language among certain Númenorian communities. Comparisons may be made between Alexandria and cities like Pelagir and Osgiliath as centres of Númenorian dominance and culture (Pelagir especially, there is a reason Castamir liked it so much). And, like Ptolemaic Egypt, it seems like Númenorians dominated the military, with other peoples excluded. To quote Faramir:

“But the stewards were wiser and more fortunate. Wiser, for they recruited the strength of our people from the sturdy folk of the sea-coast, and from the hardy mountaineers of Ered Nimrais.”

This would seem to imply that prior to this, these peoples were excluded, and Númenorians dominated the military. But the Gondorians learned their lesson, at least to a greater degree than the Ptolemies did, and were able to slow their decline by better integrating non-Númenorians into the state. Númenorians still hold the highest positions of power (Denethor and Imrahil are the two most powerful men in the country in the late third age, both are Númenorians), but military discrimination is at least heavily reduced.

The appendices and unfinished tales do say that Northmen were recruited into the Gondorian military after the Kin-Strife, and mentions them in Eärnur’s army sent to fight Angmar. These may have been analogous to the mercenary forces used by the Ptolemies, rather than representing a widening of recruitment (though many Northmen did settle in Gondor after the Kin-Strife).

Obviously the comparisons are not 1:1, but I think early Gondor may well have resembled Ptolemaic Egypt in the structure and stratification of society. I suspect that this began heavily breaking down after the Kin-Strife. For a start, a lot of Númenorians are dead, or have been forced to renounce their ancestry by Eldacar. The Gondorians will need to look elsewhere for a supply of manpower. Númenorian supremacy may well start being seen as treasonous due to Castamir’s actions, and an active threat to the continued existence of the Gondorian state. By Denethor II’s time the Gondorian army seems far more diverse, and even many of the aristocrats may well be non-Númenorian (though again, Denethor and Imrahil occupy the most powerful positions).

#gondor#lotr#lotr meta#my posts#I've seen people compare Númenorian imperialism to modern imperalism like that of the european states from 1600-1900s#While I think that fits for Númenor I don't think it quite works for Gondor#Ptolemaic-like Gondor seems to fit much better with how this society works-it's very much not like anything from the modern period to me#also apologies if I made any historical mistakes#I'm not a historian or an expert on ptolemaic egypt to feel free to correct me if I got anything wrong#I just think ptolemaic egypt is an interesting comparison for what we know about gondor

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

forget a chiropractor i need an entire macedonian phalanx to sort out my back

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

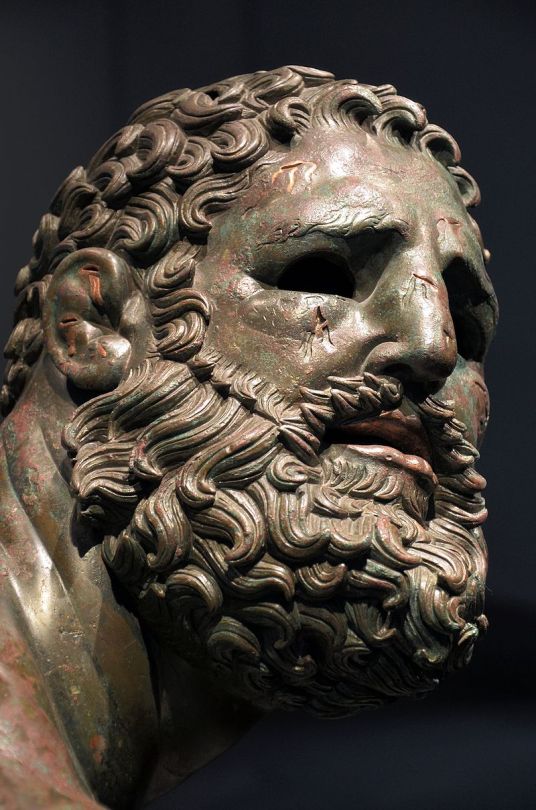

Apollonius the Athenian (active 1st c. BC)

_

Boxer at Rest / Seated Boxer / Terme Boxer, 330 to 50 BCE. Greek bronze with copper inlays, 140 × 64 × 115 cm. Εxcavated in Herculaneum (Rome) in 1885, collection of the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome.

Pankration, an ancient Greek sports event that combined wrestling and boxing (the only recognized fouls were biting and gouging) was introduced at the XXXIII Olympiad (648 BC). The word derived from the Greek words παν and κράτος, which means complete power and control [over]. There weren’t weight divisions and the fight ended with one of the combatants knocked out or signaled surrender by raising his index finger.

Due to the often deaths inside the arena, after ca. 200 BC, the judges had the right to stop a contest if the life of the athletes was in danger.

According to Andreas Georgiou (historian and writer of “Pankration–An Olympic Combat Sport”), pankration wasn’t only an Olympic sport, but a technique that both Spartan hoplites and Alexander the Great’s Macedonian phalanx used in battle.

The Romans adopted pankration, called pancratium in Latin. But in 393 AD, this ancient martial art, along with gladiatorial combat and all pagan festivals, was abolished by the Christian Byzantine emperor Theodosius I.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boxer_at_Rest

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thermae_boxer_Massimo_Inv1055.jpg

https://brewminate.com/ancient-greek-boxing-legends-and-history/

https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/pankration-deadly-martial-art-form-ancient-greece-005221

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/ancient-mediterranean-ap/greece-etruria-rome/v/apollonius-boxer-at-rest-c-100-b-c-e

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Apollonius-the-Athenian

Sep 24, 2020 previous eucanthos’ post

#Apollonius the Athenian#sculpture#bronze#gr#ancient#fight#technique#Pankration#Andreas Georgiou#research#history#box#wound

63 notes

·

View notes