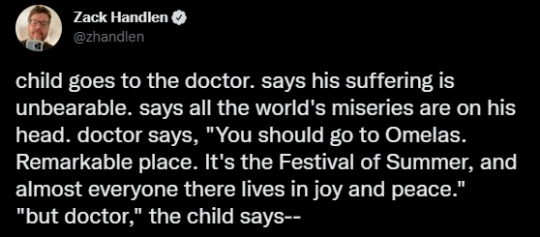

#omelas

Text

silly pet peeve but boy do lot of people misread Omelas. “It doesn’t make sense that one child suffering lets other people live in a utopia” yeah that’s the point. It’s almost like even if the reader has been taught that some exploitation is simply part of life, they can still imagine a world where no one actually had to suffer.

These people are still all reading it better than that one pro life Christian blogger though so like. Partial credit?

Update: this was a pretty off the cuff post and I think it’s more fair of me to say that it’s a story that lends itself to multiple interpretations. Le Guin calls it a psychomyth, a genre which she defines as “more or less surrealistic tales, which share with fantasy the quality of taking place outside any history, outside of time, in that region of the living mind which—without invoking any consideration of immortality—seems to be without spatial or temporal limits at all.”

So yes, it’s supposed to be an atypical story. A thought experiment that takes place everywhere and nowhere. It’s about what we accept in a story on one level but it’s also operating on multiple layers and the disturbing image of the child locked in a scary dark room just to suffer is why the story is memorable enough that it gets memed and debated decades after it was written.

I shouldn’t have downplayed the ethical question it implicitly asks the reader— could you stand being part of a society where someone has to suffer for your comfort? The irony isn’t lost on me. In a post about how people don’t engage with one layer of the story, I failed to engage with another layer of the story.

But I would still argue that a radical imagination, one that lets you imagine how life could be structured without anyone having to suffer, is part of what it takes to dismantle any kind of system of injustice, and so the question of whether you can imagine a world where no one needs to suffer is a central question of the story too.

It’s not just, “would you walk away?” It’s also, “can you imagine a world where no one needs to walk away?” because thinking of something is an important step towards making something.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

(source)

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

omelas writing masterpost

accepting that I will be thinking really hard about omelas approximately once per year for the rest of my life so here's a bunch of links for future me next time I go down this rabbithole

The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, Ursula K. Le Guin (1973)

Omelas, Je T’Aime, Kurt Schiller (2022)

The Ones Who Stay and Fight, N.K. Jemisin (2018)

The Ones Who Yell at Omelas, Rite Gud podcast (2022) [links a bunch of other responses]

tumblr post by shedoesnotcomprehend (2018)

After We Walked Away, Erica L. Satifka (2016)

Why Don't We Just Kill the Kid In the Omelas Hole, Isabel J. Kim (2024)

and bc I always forget, the BTS music video that references it is Spring Day

@ myself read another story jfc

#le guin#omelas#hmu if you've got other stuff that's interesting#always want to talk about uklg#also I want to see some older interpretations since all of these are from the past 10 years

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ones Who Found The City

Ursula K. LeGuin's "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" is a classic short story, and obviously I knew of it, but I'd never actually read it until recently. Well, I finally got around to it, and as many timeless classics do, it got stuck in my brain. This story is my - response? homage? sequel? pale imitation? - to it. I suggest you go and read "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" if you haven't. Not because it's actually required reading for this story - I think it stands on its own more or less okay - but because it is a classic for a reason.

---

Initially, no one is quite certain of what they’ve found when the Animus breaches the next manifold layer. This is in and of itself expected, of course. Exploring psychspace is by its very nature an unpredictable venture. Each of the various infinite layers is unique and bizarre in its own way, reflecting the archetypal underpinnings of an entire species present, past, or future across an infinitude of possible realities. The crew of the Animus, therefore, has seen things so utterly alien and inexplicable that only the rigors of their training and the care put into their psychic warding saved them from insanity.

It is somewhat disappointing, then, to find that this sub-domain is just a city. Definitely not Terranic, certainly not, but still following the Terranic modality, with no more than a seven-degree quantum drift.

“Towers,” Thromby says into the recorder as they sit at their post at the nose of the Animus’s command center. “Following the standard skyscrape pattern. Unclear if they’re domiciles or business centers or both. Coastal city, bay appears to be oceanic rather than lake. Pleasing blend of urbanization with natural setting.” They glance at Vigil. “Anything on the lifescope?”

Vigil shakes his head. “Nothing. It’s empty. Totally empty.”

“That’s odd,” Katrina speaks up from the helm. “The city doesn’t show signs of decay or reclamation by nature.”

“Entropy may not work in the usual way in this sub-domain,” Teasha reminds her. “The city itself could be the natural growth, reclaiming the artificial countryside. We’ve seen things like that before.”

Thromby feels Katrina’s unconscious bristling at the subtle reminder that she is the newest member of the crew and thus less experienced in the vagaries of psychspace than everyone else. Next to Vigil, who is only nineteen, she is also the youngest. “I would expect,” Katrina says, her voice cool, “that in a sub-domain so obviously based on human archetypes, entropy and nature-versus-civilization tropes would function more or less as usual.”

“I’m certain you would,” Teasha replies, her voice equally cool. “When you’ve been at this as long as me and Thromby, you’ll learn better.”

“Enough of that,” Thromby says before Katrina can reply. They love Teasha, but she tends to be too harsh on new crewmembers. A defense mechanism, they know, to insulate her from the all-too-common pain of losing them. But Katrina has too much to prove. The clash is natural and to be expected, and even useful at times, but now is not one of them. “Vigil, get me readings on atmosphere, microbiome, and psychic radiation, if any. Katrina, pick a spot on the coast and bring us down there. I want to see if the ocean is actually an ocean or a liminality representation. Teasha, get the Animus tuning to this sub-domain’s resonance frequency. I don’t want any dissociation issues.”

The orders are mostly unnecessary, since everyone already knows what they’re about, but they serve their intended purpose, which is to re-focus everyone on the task at hand and redirect their nervous energies, particularly Katrina’s. Thromby still isn’t sure she’s going to make the cut after this expedition is over, but there’s potential there. They would be foolish to ignore someone with Katrina’s strength of identity grounding.

There are plenty of sub-domains out there where it’s useful to be entirely certain of who you are, and not everyone can be.

---

The first day’s worth of exploration yields more questions than answers, which is normal and expected. Thromby is indeed certain that Katrina’s initial assumption that this is a human-archetypal sub-domain is correct. Human atmosphere, human shadow- and ontological concepts, Terranic fish in the very-real ocean. But the iconography is sparse and mostly nonsensical. It’s clear that the city was able to actually function as a city, but it feels purposeful, designed, in a way that actual cities outside psychspace rarely do.

“It’s a metaphor,” Vigil says as they sit around a campfire on the beach after the first day.

“Well, obviously,” Katrina agrees, and Vigil lights up – both visibly and psychically – at her concordance. Thromby knows Vigil has been nursing burgeoning feelings for Katrina since she joined them, and has so far seen no need to make anything of it. “But a metaphor for what?”

“We don’t have enough data,” Vigil replies. “But I’m certain of it. We just need to keep exploring.”

Thromby takes a bite of the fish they’ve been roasting over the fire. It’s a pleasant change of pace to be able to eat something real, instead of the platonic nourishment suggestions dispensed by the Animus. “Agreed. I’m curious to see what the point of this place was. We have five more days before we have to resurface and the expedition has been quite successful already. I think we can spare the time. Teasha?”

Taking a bite of her own fish, Teasha purses her lips as she chews. “I concur, but I’m uneasy.”

Teasha is their psychometry specialist, so this makes all of them sit up a little straighter. “Are we in danger?” Katrina asks.

“Of course we’re in danger, we’re in psychspace. But in this particular sub-domain? Metaphorical danger, as Vigil says. Ideological or memetic patterning rather than physical.”

Thromby nods. “I suspected that might be the axis of it, here. We will need to split up to cover the necessary ground in the time we have left, so everyone stays in contact while exploring. Mechanical and psychic. No exceptions.”

None of them are particularly happy with this pronouncement, but they see the wisdom of it. It’s distracting and somewhat draining to keep a four-way psychic connection going, especially over distance, but their implanted transceivers sometimes don’t function properly, depending on the sub-domain. Electromagnetism and causality both seem to be standard here, but such things have been known to change in an instant depending on whether the sub-domain is actively malicious or not.

Thromby doesn’t feel any such malice here, though. That doesn’t mean it isn’t present; such things are often quite good at hiding themselves. But they’ve been exploring psychspace for seventy-eight years subjective. They’ve learned to trust their instincts.

---

Two more days of exploration are frustratingly unrevealing. The city is the size of a proper metropolis, and they know it will be impossible to actually explore any significant percentage of it in only a few days, but Thromby is still irritated by their lack of progress. They find evidence of cultural signifiers, rituals, and traditions, but again, the iconography is vague and appears opaque to standard Jungian-Jingweian analysis.

Teasha spends the two days on a different investigative track than the rest of them. “Psychometrically speaking the city is remarkably healthy,” she said on the morning of their second day. “Most locations, metaphorical or otherwise, bear the echoes of trauma or strife, but this place seems to have been almost entirely peaceful. Totally voluntary anarcho-communism or ordnung-socialism, perhaps, without the usual markers of systemic violence inherent to capitalistic or fascistic systems. But there’s a thread somewhere that I keep detecting the edges of.”

“A thread of what?” Thromby asked.

“Pain, of course.”

It is on the evening of their third day in the city that Teasha calls them to her. She uses their transceiver link rather than a psychic summons. “To avoid contamination,” she explains. “I’ve found the source of the thread. Double your usual wardings and enter seclusive patterning before you come inside.”

Thromby does so, of course, though they dislike cutting themselves off from their extrasensory perception. It feels like trying to see with only one eye. When they arrive at Teasha’s location, however, they immediately understand why she insisted on it. The possibility of psychic contamination here is very high.

“What is this?” Katrina asks, holding her nose in disgust.

“The point of the metaphor, of course,” Teasha replies. She indicates the filthy cellar in which they’ve found themselves, the only part of the city so far that has seemed actively decrepit. “I guarantee you that even if we spent the rest of our lives exploring this city we would find only this one place showing any signs of entropy.”

The cellar stinks of excrement, a combination of ammonia and fetid shit, despite the physical processes creating such smells having terminated long ago. The floor is dirt. There are no windows. In one corner there are two mops, their heads stiff with drying waste, and a bucket, the metal bands around its circumference orange with rust.

“They concentrated all of the city’s entropy into a single space?” Vigil asks.

“Not entropy,” Teasha tells him. “Cruelty.”

Katrina gapes, her hand falling away from her nose for a moment. “Come again?”

“Something lived here,” Teasha explains to her. “Or, more precisely, was forced to live here. It functioned as a psychic magnet, of sorts. The functioning of the city relied entirely upon its imprisonment and use as a scapegoat.”

“What was it?” Vigil asks.

“One of the innocence-sacrifice archetypes. An animal or a child. I suspect a child; an animal can feel pain and misery, certainly, but it doesn’t conceive of injustice in the same way a child does.”

Thromby feels their stomach turn a little. “Ah. I see.”

“See what?” Katrina demands.

“The point of the metaphor indeed,” Thromby replies. “This entire city and all its inhabitants, predicated on the suffering on a child. It’s a morality construct, and a good one, too.”

“A good one?” Vigil asks. “It’s grotesque.”

“Your deontological leanings are showing,” Katrina tells him. “From a utilitarian perspective it’s perfect. Nothing exists without imposing an energy burden on the system in which it exists. Even the nourishment suggestions the Animus feeds us in liminal space between manifolds is distilled from universal krill. But this? The concentration of all of a society’s utility burden onto a single individual. The ultimate maximization principle.”

“And your teleological leanings are showing,” Teasha sniffs. “You’re missing the point of the metaphor entirely, Katrina. It isn’t about utility. It’s about cruelty. The cruelty is the point.”

Katrina’s nostrils flare and Thromby cuts in before she can start really arguing. “Enough,” they say. “A conflict here in this space could be dangerous. We’re at the focus of the sub-domain and things have a way of rippling. We’ve discovered the point of the metaphor, so we can go back to the Animus and leave in the morning.”

Both Katrina and Teasha look ready to argue the point with them, but then they master themselves and both nod.

“Do we have to wait until morning?” Vigil asks, looking around the cellar in transparent disgust. “I would prefer to leave sooner rather than later.”

“You know the rules,” Thromby replies. “We don’t transit without everyone being rested. A tired mind is a vulnerable mind.”

Reluctantly, Vigil nods, too. The four of them walk away from the cellar, their thoughts opaque to one another.

---

Thromby is jolted out of sleep by Teasha screaming.

They sit bolt upright and look down at Teasha in the bed next to them. She is clutching at her head, shaking, writhing beneath the sheets. “Teasha!” Thromby snaps. “Focus! Center yourself!” They grab her by the wrists and pry her hands from her face; her nails are leaving bloody marks in her skin.

“Too much, it’s too much!” she shrieks. “I’m lost!”

Thromby forces their way into her mind. She previously gave them her consent for this, knowing that it might be necessary in a moment like this one. What they see there –

“Aquinas,” they say aloud. The implants in Teasha’s cochlear nerves pick up on the trigger word and activate, sending the kill-signal to other implants deeper within her brain. She stops screaming and slumps, unconscious, temporarily brain-dead. When Thromby says the word again she will be switched back on, but for the moment she is safe from the psychic contamination that was attacking her along her psychometric vector.

Which, of course, means that Thromby has to deal with this issue alone.

They dress quickly and exit the Animus into a beautiful summer day. Pennants and banners wave atop the rigging of ships in the harbor, bells sound from the city, and people, so many people, cavort and revel on the beach, in the waves, in the streets. There is laughter, merriment, the intoxicating psychic swell of happiness and excitement. Thromby threads their way through the crowds in the streets – mothers carrying their infants, children running through the streets in elaborate games of some variation of Terran tag, huge parades of horse-drawn carts with animalistic balloon totems floating in the air above them. Vendors call out to Thromby, offering delicious food, intricately made jewelry, amazing clockwork-mechanical toys, sensory-enhancing drugs, and a thousand other variegated temptations. Street musicians play upon cunningly crafted instruments – strings, pipes, percussion, keys – and revelers cavort to the tunes.

Thromby can feel the bright sparks of all of these people in their mind. These are real, thinking, feeling beings. They belong to the metaphor, certainly, but Thromby could speak to them, touch them, verify their self-consciousness and interiority, even invite them to come and join them onboard the Animus and explore psychspace. They could bring them up into the real, return home with them, have a life with them. That is how it has to be, of course. Thromby knows they themself may belong to a different metaphor of a different order, after all. The real is only real because enough people agree it is.

But they do none of these things. They just walk, stolidly, back to where they know they have to go.

Katrina is waiting for them outside the cellar, barring the way in. Thromby has their wards up at triple strength and has been in seclusive patterning since before leaving the Animus, but they don’t need to be psychic to read her mind. Everything she is feeling and thinking is there in plain sight – the proud and defiant way her chin is thrust out, the blaze in her eyes, the way she has her arms crossed and feet at shoulder width. She is ready to fight.

“Let me through,” Thromby says without preamble.

“No.”

Well, that’s their respective positions, Thromby thinks, articulated clearly and easily enough. “Why not?” they ask.

“Vigil consented.”

“Vigil is in love with you and you know as well as I do that consent is a matter of framing,” Thromby snaps. “Move.”

“No. I explained everything to him and he consented. It has nothing to do with whatever feelings he might have for me.”

“That’s bullshit and you know it, but fine. For the sake of argument, tell me how you explained it.”

Katrina hesitates, and Thromby can tell she wasn’t expecting them to actually offer her a chance to proselytize. “The point of the metaphor is that no matter how great and beautiful the society, if it’s predicated on cruelty, it’s unjust,” she says. “Deontological thinking, obviously, but cruelty is by definition nonconsensual. I explained to Vigil that if he allowed it, we could collaboratively put blocks in his mind, purposefully regress him to a childlike mental state, and put him in the cellar to suffer for a specific length of time. Then we can pull him back out, remove the blocks, and even erase the memories of the trauma. The child-Vigil won’t, can’t, consent, but it also won’t exist for more than a day, and pragmatically speaking never will have.”

Thromby massages their temples. “Congratulations. Once again, you have missed the point of the metaphor.”

“Damnit, Thromby, I’m not a child! I have the same training and grounding in theory that you and Teasha do. Everything I’m doing is teleologically sound, and Vigil agreed that with the steps we’re taking –”

“You’re trying to outsmart it,” Thromby cuts her off. “That’s how I know you’ve missed the point. You can’t outsmart this, Katrina. There is no perfect set of circumstances you can construct to get around the simple fact that this city functions, exists, because of deliberate and terrible cruelty. That’s the entire point of it, just like Teasha said. Teasha, who, by the way, is currently in a coma. I had to put her into it to keep Vigil’s misery from damaging her.”

“It’s a thought experiment,” she argues, obviously not addressing the point about Teasha because she knows she won’t win that argument. “There’s always a correct answer for them. The trolley, the Gettier, the –”

“It’s about fucking sin,” Thromby sighs.

“Are you joking right now? You’re going back to the religious well?”

“Yes, because that’s what’s happening right now. The city is a sin, Katrina. The excesses of its beauty, its wonder, its perfection, are obscene precisely because of how and why they function. It’s rooted in the ideology of disgust and taint. Utility, teleology, all of these justifications and rationalizations exist and have their use, but at the end of the day, answer me one question: will you trade places with Vigil?”

Katrina hesitates.

It’s only a bare moment, less than a second, even, but it’s there. And Thromby sees it, and Katrina sees it.

“Yes,” she says, finally.

“I knew that would be your answer. But you know that the answer doesn’t really matter, does it?”

Katrina lowers her head. “No.”

“You know why you hesitated.”

“Yes.” She looks back up at them. “But – there’s no such thing as absolute morality, any more than there’s a single objective reality.”

“Of course there isn’t. And yet, you hesitated.”

They just lock eyes for a few seconds. Then she lowers her gaze again. “And yet, I did.”

Thromby steps past her and opens the cellar.

#writing#my writing#story#short story#short stories#creative writing#omelas#the ones who walk away from omelas#ursula k leguin#leguin#science fiction#sci fi#sci-fi

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the wild things about people’s stubborn insistence on misunderstanding The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas is that the narrator anticipates an audience that won’t engage with the text, just in the opposite direction. Throughout the story are little asides asking what the reader is willing to believe in. Can you believe in a utopia? What if I told you this? What about this? Can you believe in the festivals? The towers by the sea? Can we believe that they have no king? Can we believe that they are joyful? Does your utopia have technology, luxury, sex, temples, drugs? The story is consulting you as it’s being told, framed as a dialogue. It literally asks you directly: do you only believe joy is possible with suffering? And, implicitly, why?

the question isn’t just “what would you personally do about the kid.” It isn’t just an intricate trolley problem. It’s an interrogation of the limits of imagination. How do we make suffering compulsory? Why? What futures (or pasts) are we capable of imagining? How do we rationalize suffering as necessary? And so on. In all of the conversations I’ve seen or had about this story, no one has mentioned the fact that it’s actively breaking the fourth wall. The narrator is building a world in front of your eyes and challenging you to participate. “I would free the kid” and then what? What does the Omelas you’ve constructed look like, and why? And what does that say about the worlds you’re building in real life?

#ursula k le guin#omelas#There are so many ideas in this story that simply do not get engaged with!#I’ve heard it argued that a central element of anarchism#as a political philosophy#is the expansion of the imagination: what is truly possible if we forget the structures we are raised in?#if we forget what we have been told is or is not possible?#le guin wasn’t an anarchist but her work is heavily inspired by anarchist thought#Also the idea that the compassion of citizens of omelas is possible only because they are able to see themselves in relation and contrast t#the kid#very interesting stuff there#arguably a searing critique of moderate liberals#who feel compassion from on high but rationalize the ways in which those who suffer cosmically deserve it#in order to maintain structures of suffering#This short story is breaking the fourth wall Constantly to grab you by the collar and ask#what do you think is possible in the world and what do you think is good and what do you think is necessary#If you want to free the kid then what! What does that mean!#ALSO if omelas is a place being constructed as an idea#are the ones who walk away meant to be literally deserting a place#or are they rejecting an idea#hmmm much to think about

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Omelas

"The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas"

By Ursula K. Le Guin 1973

This haunting short story is about a city that can be a utopia only if a single child suffers. You will forever be thinking about this story after reading it.

Fun fact, she chose the name from a passing road sign. Salem O (Oregon) spelled backwards. This story is very much grounded in colonized Oregon's long history of utopia projects (that all eventually fizzle out, many after becoming dangerous cults).

"Why Don't We Just Kill The Kid In The Omelas Hole"

By Isabel J. Kim, 2024

Kim tells the story of what happens if the suffering child of Omelas is killed. Outstanding new story that powerfully examines Omelas vs. our world.

"The Ones Who Stay and Fight"

By N. K. Jemisin, 2018

Jemisin's rebuttal to "The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas" about a society that achieves utopia through honoring all people as having inherent worth. It asks the reader why that sounds so impossible.

#Ursula K. Le Guin#Omelas#The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas#Isabel J. Kim#Why Don't We Just Kill The Kid In The Omelas Hole#N. K. Jemisin#The Ones Who Stay and Fight

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Answer as honestly as you can, and explain your answers in the tags if you want

#poll#the ones who walk away from omelas#ursula k. le guin#literature#literary poll#utopia#dystopia?#tumblr polls#omelas

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am working on a paper for school and oh man the human brain was NOT meant to read The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas seven times in one day. I am staring into the void, and the void is a mop closet, and BOY HOWDY is it staring back.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

A week after you decide to stay in Omelas, they show you the second child. It's just as dirty, just as neglected, just as miserable as the first one.. They tell you that this one, too, is necessary.

In another week, they show you the third one. It's a damned shame, what they do to that child. But they assure you that it's necessary.

In another week, well, you're not stupid. You know what to expect when they tell you they have something to show you. Again, they're very clear about the necessity of it all.

And the weeks go by, and so do the children, but you've grown used to it. After all, you stayed for the first one.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

team of scientists in Omelas studying the phenomenon of "tortured child = utopia" trying to figure out if there are sneaky ways to reduce the child's suffering without disrupting the utopic effects

they're unsuccessful and become very depressed and eventually lose funding. no money in un-torturing a child

different team of scientists studying if "The Omelas Effect" can be extended to other cities; do they need their own tortured children too, do bigger cities with more people need more tortured children for the same amount of utopia?

why does the effect care about geopolitical borders anyway, they say.

Assuming you only ever need one tortured child for a theoretically infinite number of people, should Omelas start invading its neighbors with the eventual goal of conquering the world. getting a lot more utopia per tortured child that way. respecting the child's sacrifice (unwilling). maybe they have a moral obligation to do it. does a perfect utopia even have the capacity to wage war. does the utopia effect mean they can just ask really niceys and it'll work

a political faction says the kid has it too easy, sure they're starving and freezing in miserable squalor but they're just sitting there, we should put them to work too, being the Omelas child is no excuse for not also being a productive member of society.

eventually this becomes some kind of system where the tortured child will ~earn their freedom~ if they meet some impossible work quota. if the kid doesn't want to be tortured they should simply work harder, they're stuck down in that freezing pit because they're lazy.

#incomplete#meh#writing this actually got me to read the OG omelas story for the first time cause I wanted to see if it already addressed some of this#(mainly the last bit)#and-- kind of?#drafts clearinghouse#omelas

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regrettably, my off-the-cuff, irritated post blew up.

I think it’s more fair of me to say that “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is a story that lends itself to multiple interpretations. Le Guin calls it a psychomyth, a genre which she defines as “more or less surrealistic tales, which share with fantasy the quality of taking place outside any history, outside of time, in that region of the living mind which—without invoking any consideration of immortality—seems to be without spatial or temporal limits at all.”

If you put aside the fact that complete universality is kind of unattainable, what she’s gesturing at is that it’s supposed to be an atypical story. A thought experiment that takes place everywhere and nowhere. It’s about what we accept in a story on one level, the level I argued many readers don’t engage with, but it’s also operating on multiple layers and the disturbing image of the child locked in a scary dark room just to suffer is why the story is memorable enough that it gets memed and debated decades after it was written.

I shouldn’t have downplayed the ethical question it implicitly asks the reader— could you stand being part of a society where someone has to suffer for your comfort? The irony isn’t lost on me. In a post about how people don’t engage with one layer of the story, I failed to engage with another layer of the story.

But I would still argue that a radical imagination, one that lets you imagine how life could be structured without anyone having to suffer, is part of what it takes to dismantle any kind of system of injustice, and so the question of whether you can imagine a world where no one needs to suffer is a central question of the story too.

It’s not just, “would you walk away?” It’s also, “can you imagine a world where no one needs to walk away?” because thinking of something is a step towards making something.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

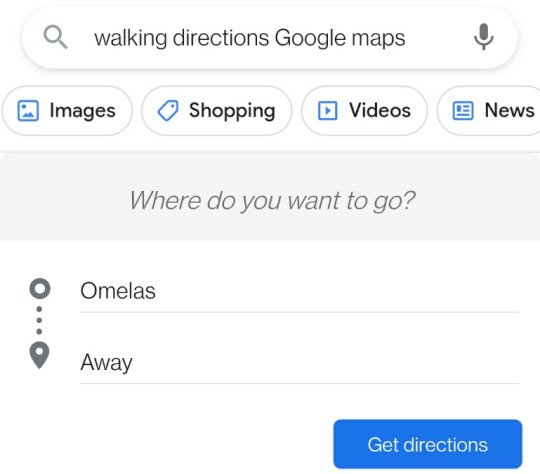

[Image description Screenshot of a Google maps search for walking directions away from Omelas]

#ursula k. le guin#the ones who walk away from omelas#omelas#image described#image description added#described images#geekysteven

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

For anyone who would like to read "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas," the source text for SNW's "Lift Us Where Suffering Cannot Reach" episode.

https://archive.org/details/the-ones-who-walk-away-from-omelas

#Star Trek#Strange New Worlds#Lift Us Where Suffering Cannot Reach#Ursula K. Le Guin#Omelas#the ones who walk away from omelas

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are two things you need to know about the road that leads away from Omelas. The first is that it's lined with human bones, because good ethics are no substitute for knowing how to survive in the wilderness. The second is that it's forked.

One fork - the one not often taken - leads to a swamp, a nasty fetid place, where a small community of people try to scratch out an existence. It's a miserable life, and the people have fond memories of the comforts they enjoyed every day back in Omelas. But they don't regret leaving it behind, for here in the swamp the misery is equally distributed to everyone. No one suffers for someone else's luxury. In the cold damp night, they tell their few shivering children why this matters.

Perhaps this knowledge consoles them as they die from disease or malnutrition or childbirth. Perhaps they sincerely believe it's worth it. I'll never know for certain.

The second fork leads to a cave of unimaginably hostile darkness. Those who stumble into the cave can barely find each other, let alone food or water. A bowl of corn mush would be a delicacy beyond measure in this cave. Whatever meager necessities of survival there are, they are constantly fought over in the dark. Some win. Others die or suffer grievous injury. Every so often, you can hear sobs echoing through the darkness.

All this misery goes to one purpose: To sustain the house above the cave. It's a huge house, with a beautiful view out of every window. And in the house lives a man, whose every slightest whim is instantly indulged, whose every luxury is available to him instantly.

Every morning and every evening, he calls down into the cave's mouth, telling the people there how lucky and blessed they are, for here they don't have to exploit that poor tortured child any more. Here, they have been freed from the sin of Omelas. His voice is warm and kind and pleasant as he speaks. And the people in the cave nod to themselves in agreement, in the dark. They pray, not for their own deliverance, but for God to smite the wicked city. For how could a just God allow one child's torture for the comfort of so many?

Perhaps those prayers keep them warm in the darkness. Perhaps they provide consolation for their empty bellies or broken limbs. I'll never know for certain.

That's where the road away from Omelas leads.

Where did you say you lived, again?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas (Le Guin, 1973) summarised:

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Beautiful Maze~

She is a demon.

#bjd#ball#jointed#doll#ball jointed doll#sd#female#girl#peakswoods#vampire#red#omelas#outside#farm#australia

14 notes

·

View notes