#the complete works of alberto caeiro

Text

Feel the night enter

Like a butterfly through the open window.

— Fernando Pessoa, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, transl by Margaret Jull Costa & Patricio Ferrari, (2020)

#Portuguese#Fernando Pessoa#The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro#Margaret Jull Costa#Patricio Ferrari#(2020)

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 favorite reads of 2023, thank you amor (: @toramona 📚🫶🏽

#reread Persepolis for the first time in 10 yrs and I still love it#the 6th one is the complete works of alberto caeiro btw#idk who to tag but I’d love to see everyone’s fave reads<3#tag game💭#mine

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fernando Pessoa’s The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro Bilingual Edition Review

I started with Fernando Pessoa’s The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro Bilingual Edition. His pseudonyms were not just that they were actual characters, OC’s, apart from him with different thoughts & believes. He gave them dates of births and lives then wrote as them. He had like two trunks and 30k papers found that is still being delved through with over 70 characters he did this with. His main character and most prolific is the one I started with.

I found myself more intellectually moved than emotionally. And it led me to wonder if Caeiro’s poetry any less because he is a fictious character of Pessoa’s imagination. Are the emotions a flat facsimile. They are pretty in their own way. And expertly tailored for the character. But a character he was.

Yet do I not feel with a fictional character in a novel as I walk alongside during their trials in magical or mundane worlds. So why did I not find myself falling into this characters head but instead intellectualizing, analyzing what it says about the Pessoa instead.

This character is no less than one in a novel, except his world is viewed through the poetry he writes as he experiences. Maybe it is because I could not see the experiences that begat the poetry as I see the experiences in a novel.

And yet I don’t see the experiences of any poet that have breathed & I still become wrapped around their words instead of intentions. I think all of our characters have pieces of us in them & Caeiro’s character is so wrapped around the state of nothing as only someone whose head is intimately entangled in chaos & wishes for simplicity could write him.

If you write a song about something you experienced it is all you. If you write a poem about something you experienced it is all you. If you write a character who writes a poem on his experience experiencing how much is it you. In parts I think he created this character then deemed this creation his poetical master because this is who he wanted to learn to be. To see without searching. To look without wondering. To be. Yet the marvels he would not have created were his head not so full he had to create to empty it.

Caeiro fictional work of art obsessed with everything being nothingness fell in love in the middle of this book. His poetry have become ode to the state of feeling for this other fictional character. And this is was interesting because if love is anything it is everything. You can’t bring the state of nothing to something that is everything. And a transformation we did start to see but then intriguing as it was Caeiro’s the keeper of the sheep portion has finished. It seemed by the end of it he was starting to find the everything in nothing. Don’t you just love a good growth arc. It does make you wonder if he Pessoa made Caeiro fall in love because he himself was similarly was and wanted to explore it or because he hadn’t and still wanted to explore it.

In the uncollected poems portion I found if Caeiro were real and not a carefully constructed fictional entity I would likely find him rather annoying with his perpetual condemnation of poets who personify everything. As is I found him fascinating. Like an interesting lab experiment.

There is a wonder if Caeiro while fictional does in fact exist and by that I mean his way of thinking. To see just with eyes and there be no meaning in anything, no significance. And in a world where anything could be it must be. But it is foreign to me whose mind sees in duality. I can look at the stars and know they are hydrogen & helium & gravity. But I can also look at the stars and wonder if they yearned until the yearning burned so hot they consumed everything to travel eons and fall upon the earth until they grew lungs to breathe with and feet to dance with and lips to melt onto another’s.

I see the stars & I see the stars & I know their heat can mean life. But I see the stars & I see the stars & I know their heat must mean life. That the ichor in my veins comes from the very core of them. So if I can yearn w/ such intensity it must be their remanent that allows it. Because when I see one thing I don’t just see one thing. I see a thousand possibilities alongside it. Everything it is, along with everything it could be, and everything it might be, and everything it would be. And my brain is never just seeing to just see. A flower is not just a flower. It is a scent, it is a taste, it is a longing, it is a memory, it is a possibility, it is a remanent, it is kin to the me that blooms when watered and wilts in droughts and came from the earth, it is a tapestry, and a dozen other things. And so is everything else I lay eyes on. But it must be peaceful to see and just see the input from your eyes to your brain and your brain to your eyes and a thousand possibilities never springing like wildflowers unbidden.

By the Interviews section I was sure the Ego Pessoa gave him is as big as the earth Caeiro proclaims to not see with anything but his eyes. I have wondered since reading this Caeiro’s complete works if I have ever seen just to see. I have lived my life in many different state of minds. If it were possible I’d have earned a doctorate in ennui before I left high school. And still even when seeing was a blur I could not see just to see.

And I look at my computer screen in contemplation trying to emulate a foreign frame of mind. A computer is a computer, Caeiro would say. And yes a computer is a computer but my brain connects constellations and manifests Hermes. Humanity’s perpetually attempting to pull the Gods to the mortal world. Quintessential messenger, mischievous and clever as the hands that fall on its keyboard. Humans go to it sometimes as an emissary, sometimes in hopes for luck in trade and wealth, and in it lays the Tower of Babel connecting us all. And as I am more awake than I have ever been before in my life I wonder why I would want to see just to see when seeing multifacetedly births so many interesting things.

I found it kind of hilarious how Pessoa has his other OCs gush about his main OCs poetry and also kind of brilliant from a marketing standpoint because they’re gushing in like lit journals therefore creating more hype for his works. And liked how Pessoa wrote articles about Caeiro like the ultimate author storyboarding their character and trying to delve into their brain and gushing about their OC to anyone would listen for five seconds.

When done with the book I think in parts some of the reason he created so prolifically so many characters who in turn created in their own style. An exploration of these style and thought streams without potential inevitability of another drowning in that ocean. A mind making a multitude of connections to everything like a computer that’s always on and working on a never ending task.

And I do wonder if perhaps his prolific creation of fictional authors and their works which number so vastly they still haven’t finished combing through those trunks was a self regulating method for that ocean, for the ocean sometimes needs to be a stream sometimes for the sake of others, sometimes for its own. And I find it very interesting he would go on discussions with his own characters that he’d type out as himself in as such then sifting his own thoughts & beliefs while getting to know his characters.

All in all I find Pessoa and his processes fascinating and can’t wait to continue reading his works.

#bookworm#books and reading#books and literature#currently reading#booklr#bookworm life#booklover#booknerd#poetry#prose#book review#book recommendations#fernando pessoa#alberto caeiro

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fernando Pessoa, an insight.

Good afternoon, everyone!

I hope you are all fine and that, above all, you have enjoyed your Easter break! Now it is time for us to get back to burning the midnight oil to produce only the finest work, for our very own Luke White!

It was after having my one-to-one tutorial with Luke, and reviewing my blog assessment, that we discussed and agreed that the right next course of action would be to further dive into the man himself, Fernando Pessoa, and give you a better insight on the worldly, cultural icon, that is Fernando Pessoa. Let's dive into it!

Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) was a renowned Portuguese poet, writer, and philosopher, considered one of the most important literary figures of the 20th century. He was born in Lisbon, Portugal, and spent most of his life there, except for a brief period in South Africa. Pessoa's work is characterized by its originality, its experimentation with language and form, and its intense exploration of the human condition.

Pessoa is perhaps best known for his poetry, which he wrote under various heteronyms, or literary alter egos, each with its own distinctive style, voice, and personality. These heteronyms were not mere pseudonyms, but fully realized literary personas, complete with biographies, aesthetics, and worldviews. Some of the most famous heteronyms include Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos.

Caeiro, for example, is a simple shepherd who writes in a direct, sensory style that celebrates nature and rejects abstraction and intellectualism. Reis, on the other hand, is a classical scholar who writes in a refined, formal style that echoes the Latin poets of antiquity. Campos is a restless, modernist engineer who writes in a fragmented, stream-of-consciousness style that reflects the disorientation and confusion of modernity. By using these heteronyms, Pessoa was able to explore a wide range of themes, styles, and perspectives, and to challenge the notion of a stable, unified self.

In addition to poetry, Pessoa also wrote prose, including essays, reviews, and literary criticism. He was deeply interested in philosophy, and his work reflects his engagement with existentialism, mysticism, and occultism. He was particularly drawn to the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, and he developed his own metaphysical system, which he called "the philosophy of the sensation." This philosophy posits that reality is unknowable, and that the only way to approach it is through sensation and intuition.

Pessoa's writing is marked by a profound sense of melancholy, loneliness, and alienation. He often portrays himself as a solitary observer, disconnected from the world around him, and his work is suffused with a sense of longing for something beyond the limits of everyday experience. This existential angst is evident in poems such as "The Keeper of Sheep," in which Caeiro declares that "To feel is to be other," and in Campos's "Tabacaria," in which he laments that "Everything is worth the trouble / Only one can't get everything."

Pessoa was not widely recognized during his lifetime, and he published very little under his own name. He worked as a translator, commercial correspondent, and advertising copywriter to support himself, and he lived a reclusive existence. However, after his death, his work was discovered and championed by a group of Portuguese intellectuals, who recognized his genius and helped to establish his reputation. Today, Pessoa is celebrated as one of the greatest poets of the Portuguese language, and his work continues to inspire readers and writers around the world.

In conclusion, Fernando Pessoa was a unique and innovative literary figure whose work defies easy categorization. His use of heteronyms, his engagement with philosophy, and his exploration of the human condition have made him a lasting influence on Portuguese and world literature. His legacy continues to inspire new generations of writers and thinkers, and his work remains as relevant and captivating today as it was during his lifetime.

Hope you now have a little more insight into the greatness of Fernando Pessoa! Until next time!

Miguel Moreno.

0 notes

Note

pleade reccc top 3 books that u think will make me escape myself . too in my head its killing me slowly

im thinking fiction then? cause most of the books i read give 'bringing u face to face with urself' opposed to escaping, soooo!! 1) dune! 2) the institute stephen king 3) ray bradburys fahrenheit 451

in terms of 3 books i adore & that first came to mind 1) the complete works of alberto caeiro 2) iyanla vanzant tapping the power within 2) ted andrews nature speak

🫶🏼 u got this, feel free to msg me if u wanna chat

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fernando Pessoa, from The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro; “The Keeper of Sheep”

Text ID: Being a poet is not my ambition. / It’s my way of being alone.

#fernando pessoa#the complete works of alberto caeiro#poetry#lit#miscellanea#portuguese literature#αἰνελένη

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fernando Pessoa, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro; “The Keeper of Sheep”

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

If, when the spring comes,

I am already dead,

The flowers will flower in the same manner

And the trees will be no less green than last spring.

Reality doesn’t need me.

I feel great joy

To think that my death hasn’t the slightest importance.

If I knew that I would die tomorrow

And spring was due to arrive the day after tomorrow,

I would die contented, because it was due to arrive the day after tomorrow.

If that is its proper time, when would it come if not at that proper time?

I like everything to be real and everything to be right:

And I like it to be that way even if I don’t like it.

That is why, if I were to die now, I would die contented,

Because everything is real and everything is right.

People can pray in Latin over my coffin, if they wish.

If they wish, they can dance around it and sing.

I have no preferences for a time when I will have no preferences.

Whatever happens, when it happens, will be what it is.

- Alberto Caeiro (Fernando Pessoa), The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro (New Directions, 2020)

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fernando Pessoa, tr. Margaret Jull Costa, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro; cover design by Peter Mendlesund (New Directions, July)

30 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I salute all those who’ll read me,

Taking off my broad-brimmed hat to them

When they see me at my door

As their carriage appears over the hill.

I salute them and wish them sun,

And rain, when rain is needed,

And for their houses to have,

Next to an open window,

A favorite chair

Where they sit, reading my verses.

And that when they read my verses they will think

That I am some natural thing -

For example, the ancient tree

In whose shade, when they were children,

They would flop down, weary with playing,

And wipe the sweat from their hot brow

With the sleeve of their striped smock.

Alberto Caeiro (Fernando Pessoa), The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

He sleeps inside my soul

And sometimes he wakes at night

And plays with my dreams.

— Fernando Pessoa, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, transl by Margaret Jull Costa & Patricio Ferrari, (2020)

#Portuguese#Fernando Pessoa#The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro#Margaret Jull Costa#Patricio Ferrari#(2020)

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pessoa(s)

"Arguably, the four greatest poets in the Portuguese language were all Pessoa using different names." (NPR, quoted in the blurb to The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro)

0 notes

Text

“Fernando Pessoa sente le cose, ma non si smuove, nemmeno interiormente”

Se parli di Fernando Pessoa è come ingravidare un prisma. Un lato rimanda all’altro e poi all’altro, dio è un crocevia di specchi, le identità esistono per scomposizione. In un libro appena pubblicato da Quodlibet, Teoria dell’eteronimia, utilissimo – sono raccolti i testi che Pessoa dedica ai suoi eteronimi e i saggi in cui gli eteronimi parlano tra loro, dando avvio a un labirinto di relazioni fittizie – ho contato, nell’elenco in appendice, 46 eteronimi. In un libro pubblicato nel 2013 da Jéronimo Pizarro e Patricio Ferrari, Eu sou uma antologia, invece, gli eteronimi risultano 136. Balocco coi numeri: chi sono quei 90 spettacolari spettri rimasti fuori dalla somma italiana? Amici di amici immaginari, giù, fino a un cavalcavia di nebbie. In effetti, cosa sogna un eteronimo? E se nel sogno di un eteronimo un eteronimo sogna Pessoa?

*

Pessoa ha risolto l’egotismo in un polline di identità diffuse. Ha assopito l’io in una caffettiera, per definire i propri indecifrabili io. Mette a servizio la personalità per evacuare le persone che la abitano. Pare un esercizio mistico: al posto di annullare l’ego, decimando la sua autonomia, esiliarlo in sproporzionati alter ego. “Dare a ogni emozione una personalità, a ogni stato d’animo un’anima”, scrive, il creatore, nel 1930.

*

Pessoa è un genio tanto particolare – incardinato nella sua Lisbona, a sorseggiare i racconti di Poe – da apparire universale. New Directions ha appena pubblicato The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, per la traduzione di Margaret Jull Costa, super esperta di letteratura portoghese (ha tradotto nei mondi inglesi tutta l’opera di José Saramago, tra l’altro). La sua introduzione, ricalcata su “The Paris Review” – e pubblicata qui sotto – gioca a bocce con gli eteronimi, rievoca gli anni di “Orpheu”, il trimestrale fondato da Pessoa con Mário de Sá-Carneiro nel 1915, durato due numeri, emblema di un’epoca in cui si faceva avanguardia nei cafè, negli spazi d’ozio, tra le ombre di una copisteria.

*

Di Alberto Caeiro sappiamo quasi tutto. Nato a Lisbona nel 1889, “morto prematuramente nella stessa città, nel 1915, come assicura Ricardo Reis” (cito dal libro Quodlibet), l’anno in cui Pessoa si forza a fondare “Orpheu”. “Di statura media, fragile, anche se in apparenza meno di quanto lo fosse realmente, biondo e con gli occhi azzurri… della sua vita dimessa si sa che è orfano, che non ha quasi ricevuto istruzione, che vive di piccole rendite”. Caeiro fu maestro di Ricardo Reis e di Álvaro de Campos, che ne scrive così: “Il mio maestro Caeiro non era pagano: era il paganesimo… lo stesso Fernando Pessoa sarebbe pagano, se non fosse un gomitolo ingarbugliato dall’interno”. La sua insoddisfazione soddisfatta (“All’improvviso chiesi al mio maestro, ‘è soddisfatto di se stesso?’, e rispose, ‘no: sono soddisfatto’”) era una forma di speculazione mistica. Morì felice: “Non ho mai visto triste il mio maestro Caeiro”.

*

Gli eteronimi di Pessoa sono raffinatissimi pupi in attesa del puparo. Certe didascalie di personaggi meno nitidi, irrisolti, intendo, sembrano i blocchi di partenza di un romanzo. Friar Maurice, ad esempio, “mistico senza Dio, cristiano senza credo”, probabile alter ego di Alexander Search, “il più prolifico eteronimo di lingua inglese” di Pessoa, autore di raccolte come Death of God e Documents of Mental Decadence. Oppure Dr. Gervásio Guedes, che appare per darci una caustica descrizione del popolo inglese, “sonnambuli che camminano verso il precipizio… bambini che giocano a barchette di carta in un pitale”. Oppure il Barone de Teive, figura apocrifa, suicida, invalido – gli mancava la gamba – aristocratico; si ammazzò nel 1920, dal suo manoscritto (“La professione dell’improduttivo”) Pessoa stralciò qualche passo per inserirlo nel Libro dell’inquietudine, il cui autore più importante, tuttavia, è Bernardo Soares, che con Pessoa “condivide lo stesso lavoro, gli stessi posti della città, la stessa solitudine, la passione per lo scrivere… la coincidenza di cenare entrambi alle nove e mezzo di sera”. Insomma, sogno una città di nome “Pessoa” abitata da tutti gli eteronimi del sommo portoghese, desidero un editore visionario che affidi a differenti romanzieri, a casaccio, uno per ciascuno, uno degli eteronimi di Pessoa dicendogli, di questo tizio, ora, scrivetemi la biografia. Immagino la delizia.

*

La cosa curiosa sarebbe assemblare i giudizi e le opinioni che gli eteronimi hanno del loro creatore, Pessoa. Uno pseudonimo non fa che esagerare il nostro ego – un esercito di eteronimi è quasi un esercizio di cannibalismo. “Fernando Pessoa sente le cose, ma non si smuove, nemmeno interiormente”, scrisse di lui, nel 1931, Álvaro de Campos. Questo forse è il carisma di tutti i creatori, una audace, immotivata indifferenza: parlano, e dalle labbra appare un volto, poi una vita in miniatura. (d.b.)

***

La vita di Fernando Pessoa si divide in tre periodi. In una lettera al “British Journal of Astrology”, l’8 febbraio del 1918, lo scrittore ammette che sono solo due le date che ricordi con precisione: il 13 luglio 1893, la data della morte del padre per tubercolosi, quando aveva solo cinque anni, e il 30 dicembre del 1895, il giorno in cui la madre si è risposata, evento che coincide con il trasferimento a Durban, dove il patrigno era stato nominato console portoghese. Nella stessa lettera Pessoa segnala una terza data, il 20 agosto del 1905, il giorno in cui lasciò il Sudafrica per tornare definitivamente a Lisbona.

Il primo breve periodo fu segnato da due perdite: la morte del padre e del fratello minore. La terza perdita fu Lisbona, l’amata. Nel secondo periodo della sua vita, a Durban, Pessoa imparò a parlare con agio in francese e in inglese. Non era uno studente comune. Un suo compagno di scuola ha descritto Pessoa come “un piccolo uomo dalla testa enorme. Decisamente brillante, intelligente, piuttosto arrabbiato”. Nel 1902, sei anni dopo essere arrivato a Durban, vinse un premio per aver scritto un saggio sullo storico britannico Thomas Babington Macaulay. In effetti, passava il tempo libero a scrivere o a leggere, aveva già iniziato a forgiare i suoi alter ego immaginari, o meglio, come li definì più tardi, eteronimi, per i quali è famoso e con cui ha scritto racconti e poesie: Karl P. Effield, David Merrick, Charles Robert Anon, Horace James Faber, Alexander Search… In uno studio recente, Eu sou uma antologia, Jéronimo Pizarro e Patricio Ferrari elencano 136 eteronimi, fornendo biografie e bibliografie di ogni autore fittizio. Di questi eteronimi, nel 1928, scrisse Pessoa, “Sono esseri con una vita propria, con sentimenti che non mi appartengono e opinioni che non accetto. I loro scritti non sono miei, ma a volte lo sono”.

Il terzo periodo della vita di Pessoa iniziò a 17 anni, quando rientrò a Lisbona senza fare mai più ritorno in Sudafrica. Per vari motivi – problemi di salute, scioperi studenteschi, tra gli altri – abbandonò gli studi nel 1907, divenne un visitatore abituale della Biblioteca Nazionale, leggeva di tutto: filosofia, sociologia, storia, in particolare letteratura portoghese. All’inizio visse con le zie, dal 1909 in camere prese in affitto. La nonna gli aveva lasciato una piccola eredità, nel 1909 usò quei soldi per comprare una macchina da stampa necessaria per creare la sua casa editrice, Empreza Íbis. La casa chiuse nel 1910, senza aver pubblicato un solo libro. Dal 1912, Pessoa iniziò a collaborare con varie riviste, nel 1915 fondò la rivista “Orpheu”, insieme a un gruppo di artisti, tra cui Almada Negreiros e Mário de Sá-Carneiro, entrando a far parte dell’avanguardia letteraria di Lisbona, coinvolto in movimenti letterari effimeri come l’Intersezionismo e il Sensazionalismo.

Faceva il traduttore commerciale freelance di inglese e francese, scriveva per i giornali, ha tradotto La lettera scarlatta di Hawthorne, i racconti di O. Henry, le poesie di Edgar Allan Poe. In vita pubblicò poco: un esile volume di poesia in portoghese, Mensagem, e quattro saggi sulla poesia inglese. Quando morì, nel 1935, all’età di 47 anni, lasciò nei suoi bauli fatali (almeno un paio) un tesoro di scritture – circa trentamila pezzi di carta – ordinati grazie all’aiuto di amici e di studiosi, che ne hanno esaltato il genio.

Pessoa viveva per scrivere e scriveva su qualsiasi supporto: pezzi di carta, buste, volantini pubblicitari, sul retro di lettere commerciali, nelle pagine bianche dei libri che leggeva. Attraversò tutti i generi – poesia, posa, teatro, filosofia, critica, politica – sviluppando un profondo interesse per l’occultismo, la teosofia, l’astrologia. Ha elaborato oroscopi non solo per se stesso e i suoi amici, ma anche per molti scrittori, per celebri morti come Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, Robespierre, oltre che per i suoi eteronimi, un termine adatto – rispetto a pseudonimo – per descrivere con maggiore accuratezza l’indipendenza stilistica e intellettuale di queste creature dal loro creatore. Talora gli eteronimi interagivano tra loro, criticando o traducendo uno il lavoro dell’altro. Alcuni erano semplici abbozzi, altri scrivevano in inglese e in francese, i tre eteronimi lirici – Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos – hanno scritto in portoghese, producendo, ciascuno, un’opera autonoma, autentica.

Margaret Jull Costa

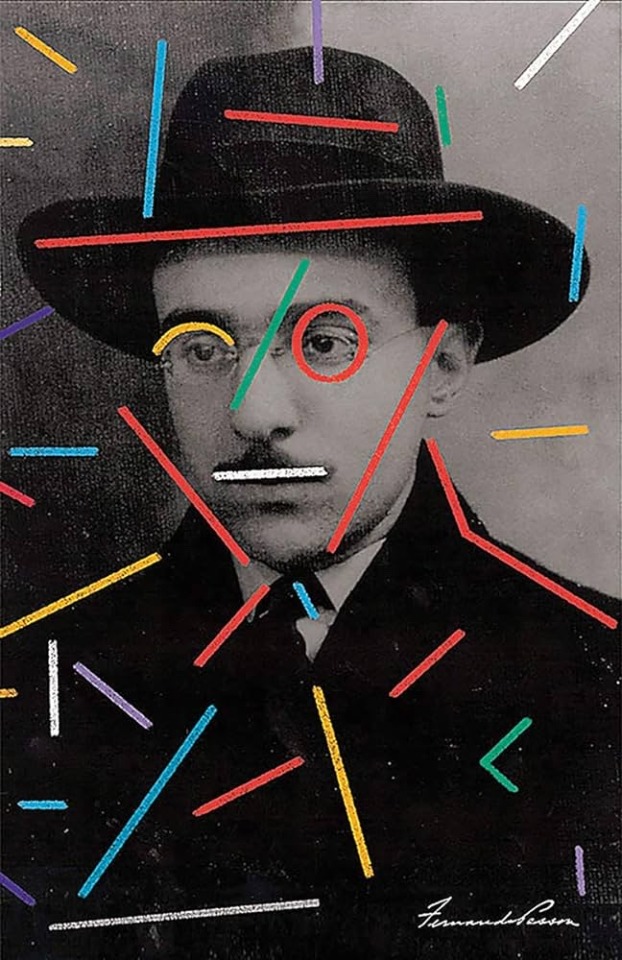

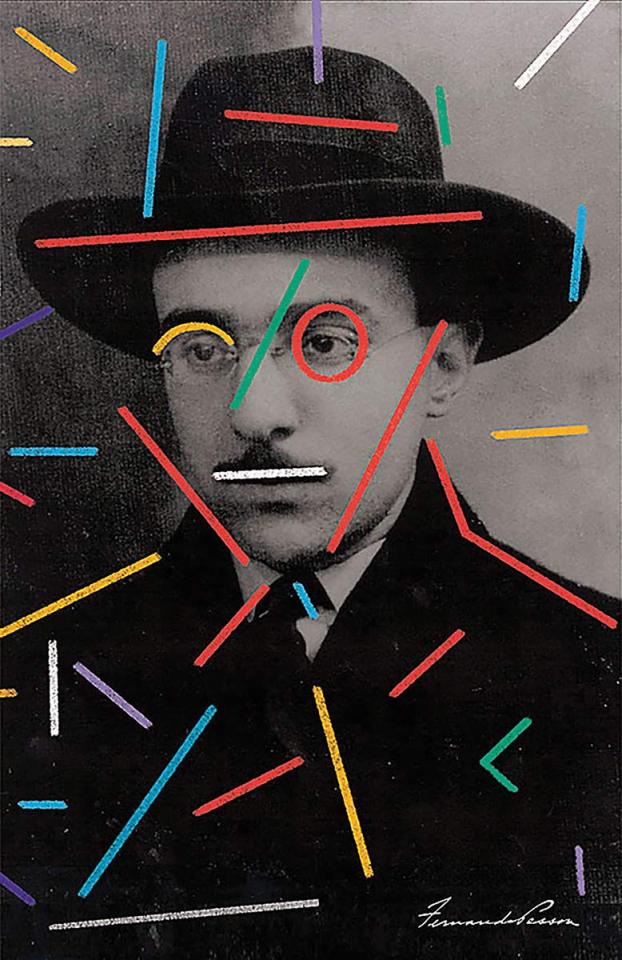

*In copertina: Fernando Pessoa nel ritratto di José de Almada-Negreiros (1954), tra i cofondatori di “Orpheu”

L'articolo “Fernando Pessoa sente le cose, ma non si smuove, nemmeno interiormente” proviene da Pangea.

from pangea.news https://ift.tt/3fBVIts

1 note

·

View note

Text

Of memories and longings

And things that never were.

— Fernando Pessoa, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, transl by Margaret Jull Costa & Patricio Ferrari, (2020)

#Portuguese#Fernando Pessoa#The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro#Margaret Jull Costa#Patricio Ferrari#(2020)#Essence#And never will be

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Night falls, [...]

I’m as lucid as if I’d never had a thought

But had a root, a direct link with the earth.

— Fernando Pessoa, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, transl by Margaret Jull Costa & Patricio Ferrari, (2020)

#Portuguese#Fernando Pessoa#The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro#Margaret Jull Costa#Patricio Ferrari#(2020)#Essence

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now I love [...]

more intimately, more movingly.

— Fernando Pessoa, The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, transl by Margaret Jull Costa & Patricio Ferrari, (2020)

#Portuguese#Fernando Pessoa#The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro#Margaret Jull Costa#Patricio Ferrari#(2020)#Essence

16 notes

·

View notes