#the distinction being that @-ing people is communication directed at them and only them‚ and so irrelevant to subsequent audiences

Text

NB: i add image descriptions to posts when i feel up to it, for walking-my-accessibility-talk reasons, but i don't claim to be particularly expert at it, and i'm always open to feedback about ways my image descriptions could be improved! that said: please don't actively delete image descriptions i've added to posts you reblog from me. if you feel the need to excise my contribution for whatever reason, you can reblog the post from a different source. thanks!

#would have thought this was just‚ like‚ basic etiquette but—apparently not‚ lol#that said‚ i don't tend to @ friends in the body of posts—i'll either tag them or send them the post directly—#but if i did‚ you'd be more than welcome to delete that!#the distinction being that @-ing people is communication directed at them and only them‚ and so irrelevant to subsequent audiences#whereas image descriptions are absolutely intended for the benefit of users down the line#anyway i will never hold reblogging from another source against you#and i'd be happy to hear from anyone whose beef with my image descriptions is with a quality of them that i can improve#anyway. no immediate context for this‚ just like‚ something happened a bit ago that made it seem worth Stating Publicly#have attempted to state it politely bc it isn't really beef‚ just a boundary: if you do this to me i will probably at least softblock you.#anyway that's all‚ folks! thx 4 listening. :3#metatumbling

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on House of X #4

Over the halfway mark!

Look At What They’ve Done Infographic:

Suprisingly for an issue that, in retrospect is the climax of the standard superheroics part of House of X, this issue starts with an infographic, which turns out to be one of the more controversial in HoX/PoX.

Foreshadowing what’s going to come at the end of the issue, the tone is already different from the pseudo-academic objectivity of earlier infographics, although the term “mutant erasure” evokes the activist-inspired, post-cultural turn work of critical race/gender/sexuality studies, which is something of a stepping-stone.

By contrast, describing Wanda Maximoff as both “the pretender” (does this mean “not-really-a-mutant” or “not-really-Magneto’s-daughter” or both?) and as associated with the Avengers is incredibly politically pointed, which speak to a particular kind of mutant nationalist identity that bears a good deal of grievance towards even benevolent human institutions.

Similarly, the term “human-on-mutant violence” is way too evocative of real world debates over racism and police violence to be accidental on the author’s point. It’s a depressing thought, but the 616 probably sees a lot of “what about mutant-on-mutant violence?” derailings, maybe as many as creep up in threads about HoX/Pox here...

So let’s get at the controversy: can Bolivar Trask be blamed for the Genoshan genocide? Contrary to a few voices in the fandom, I would argue strongly for the affirmative. As we see from his initial appearance, Trask created the Sentinels entirely out of racial paranoia/hatred; moreover, Sentinels have no purpose other than A. destroying all mutants and B. subjugating the human race along the way. Cassandra Nova’s actions on Genosha absolutely followed the Trask playbook of both father and son, and indeed relied on Larry Trask’s assistance to carry it out, making it a Trask affair from beginning to end.

On a final meta note, this infographic really speaks to the outsized impact that Morrison’s New X-Men and Bendis’ House of M had on the X-line for the last 15-20 years.

Observation-Analysis-Invocation-Connection:

But before we get to the punching, we get one burst of Hickman’s fascination with singularities and transhumanism, where for the first time we really get an example of how the Krakoan biological approach is going to work, showing us a surprisingly complicated biomachine:

Trinity (who runs the Secondary/External Systems part of Krakoa) uses her technopathy to gather intelligence from human mechanical systems: the Aracibo Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, “re-tasked SETI radio telescopes," both of which are real things, and the “Dyson solar observatory,” which isn’t.

Beast (who runs the Overwatch/Data Analysis part of Krakoa) uses Krakoan biocomputers and his own scientific genius to “extrapolate that data into an actionable forecast,” to deal with the delay caused by the immense distances between Krakoa and Sol’s Forge.

Professor X and Cerebro handle the direct Connection between Krakoa and the away team, while the Cuckoos link Trinity, Beast, Storm into a psychic link with Xavier, which means all of the parts of the system work seamlessly even as Storm handles the Invocation of visually representing Jean Grey’s thoughts.

If you step back and think about it, this is an astonishing technological feat: with minimal reliance on machine technology, Krakoa has established a NASA “KASA Mission Control” that can send data across half a solar system almost(?) instantly.

That’s before we even get to the whole secondary purpose of the system, which is to allow Professor X and the Five to resurrect an up-to-date version of anyone who dies on the mission, which is one hell of a life-rope.

Thematically, we see a really sharp distinction between biological and mechanical transhumanism/singularity: “KASA Mission Control” is described in biological terms, “function[ing] as a singular organism,” and also in religious terms, with “eight of us acting as one” explicitly labelled as “Communion.” And yet...the eight people involved retain their separate personalities and identities and no separate, artificial intelligence is created.

Should We Fear the Worst?

And across five hundred million miles, all Krakoa gets is bad news. Archangel and Husk, the redshirt’s redshirts on this mission, are dead before they do anything; Nightcrawler has some level of “internal injury,” and Wolverine almost had his arm blown off.

Incidentally, page 7 is where something of a problem crops up with Jean Grey’s characterization. As people have noted, Jean Grey starts off in the passive communications role (indeed, she’s even reliant on Monet to do that job) and doesn’t really improve from there. With the added context of her wearing her Silver Age miniskirt costume, it’s all a bit sus, especially if you’ve been reading a much more self-possessed, confident, and all-around more powerful version of Jean Grey in X-Men: Red. For a while, many of us were thinking that Jean is a younger backup, but that seems to have been Jossed by the resurrection ceremony in House of X #5.

Better characterization abounds for the men: following their conversation from the previous issue, Cyclops and Wolverine have different perspectives about the question of whether to continue on with the mission (another key element of the special ops/espionage thriller genre). Cyclops emphasizes pushing on to make Warren and Paige’s sacrifice meaningful, Logan agrees but rather because of the existential stakes of the mission. There’s an interesting parallel there between Xavier and Magneto and means vs. ends.

Following the catastrophe, Nightcrawler successfully inserts the struje team, while “Jean and Monet will stay to maintain our connection with Krakoa;”we know know that part was crucial in more than one way, but it is a continuation of some troubling gender dynamics.

Meanwhile, despite being “technically...just an observer” (and doesn’t that ring of all kinds of Cold War proxy wars), Omega Sentinel takes action to prompt Dr. Gregor into retaliation, similarly playing to the nationalistic theme of “if you don’t, he will have died for nothing.”

Orchis’ retaliation doesn’t go so well, as we see Wolverine carving his way through an AIM securtiy team and Nightcrawler bloodlessly tying up two scientists (note the further emphasis on differing personalities and values; whoever these X-Men might be, they’re not mindless followers) towards popping two of the four constraint collars.

Unfortunately, this is followed up by a couple pages of more Jean Grey being awfully Damselly: yes, she’s holding open the connection, but she’s coded as way more helpless and indecisive than Monet (who gets to go out like a badass defending the shuttle), and the line “I dunno what to say, Marvel Girl. Try harder” really sums it all up. So far, this is reading a lot more like Stan Lee’s Jean Grey (but not Jack Kirby’s) than Chris Claremont’s.

With the tension ratcheting ever-higher, we see Cyclops succeeding at his mission, while Mystique...doesn’t and then gets promptly blown out an airlock. The “habitat” connection and the odd business with her getting “turned around” despite having the plans for the base in her head like everyone else is highly suspicious (it might suggest the use of a Krakoa flower, but no one’s ever suggested what her motivation would be for doing so), but it’ll have to go on the list of plot threads that weren’t resolved in House of X.

In a development that really ought to be troubling to more people, Dr. Gregor throws away whatever moral compunctions she has about waking up a potentially violently insane A.I because “I don’t let them stop us. No matter what,” a potentially existential downside to Omega’s strategy.

Do Whatever It Takes:

Having reached the “darkest moment” in the story diagram, Professor X orders his students to “do whatever it takes” to prevent Mother Mold from coming on line. This prompts Cyclops to give the order to Nightcrawler and Wolverine to jump out into unprotected space to sever the last constraint collar. All in all, we’re following the traditional beats of the special ops/espionage genre pretty closely, down to the team leader’s moral anguish moment.

Appropriately, we then get a quiet moment where Kurt and Logan contemplate whether or what will be “waiting for us on the other side.” Even knowing what we know now about the resurrection system, there’s still a good deal of weight to this moment, because in a way this Kurt and this Logan are going to die and whether they’re the same Kurt and Logan who will be reborn is a matter I’ll take up in Powers of X #5 along with the difficult topic of the philosophy of identity. (I’m going to leave aside the question of them having gone to literal Heaven and Hell in the past, because my Doylist position is that those story threads were probably a bad idea and my Watsonian No Prize is that you can’t remember the afterlife once returned to earth.)

Surprisingly, things get only more metaphysically weird when the two teleport outside and Wolverine starts chopping his way through the last arm. Mother Mold wakes up and immdiately starts talking about Greek mythology. Mother Mold’s interpretation of the Titanomachy is a little choppy (as we might expect from an insane A.I): on the one hand, if humanity are the Olympian gods as the creator of the Sentinels and the mutants are the Titans because of “their spoiled lineage” (this doesn’t quite work, because the Titans preceded the Olympians), then the Sentinels being “Man” makes sense. And as someone who’s written his share of college papers about omniscience/predestination/free will in Greek myth and drama, there’s a plausible anti-theist position whereby human beings might “judge and find you both wanting.” (Although that language is too Book of Daniel for the Greeks.) On the other hand, if the Sentinels are man, them having “stolen your fire” doesn’t work either - humanity was given fire by the Titan Prometheus - unless the argument is that Wolverine is Prometheus because he yeets Mother Mold into the sun?

Regardless, it’s a very ominous note for Mother Mold to go out on, because the consistent anti-human/Olympian tone suggests this insane A.I might hate humans way more than it hates mutants.

With the day seemingly saved, we transition into the Rogue One scenario where Cyclops is murdered by a vengeful Dr. Gregor and Jean is torn apart by Sentinel drones.

As gruesome as all of this is, I think it does play a very important role in explaining a good deal of Charles Xavier’s change of mind with regard to human-mutant harmony and assimilation. While this incident didn’t prompt any of the decisions that he’s made along the way - this mission is happening post-Xavier’s announcement and a day before the U.N vote, making it quite late in the X^1 timeline - I think it does a good job of showing us the kind of thought patterns that have led Xavier to this conclusion. In addition to everything he’s seen from Moira’s past nine lives, which only lend a greater sense of urgency and the fear of inevitability, Xavier himself has experienced the deaths of “our children” over and over again as the founder of the X-Men, and clearly both the direct trauma (keep in mind, he’s hooked into the minds of all of his X-Men as they die) and the pain he feels at humanity’s apathy/atrocity fatigue, goes a long way to explaining why he’ll make the decision that integration and assimilation are no longer viable options.

For all the crap that people sometime sling at Hickman over his use of charts, I will say that the way that “NO MORE” weaponizes them by extra-textually demonstrating the breakdown of the facade of calm objectivity is incredibly effective.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watch the American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 now: https://youtu.be/bWiW4Rp8vF0?feature=shared

The American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 broadcast recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by active climate leaders. Watch to find out which finalist received the $50,000 grand prize! Hosted by Vanessa Hauc and featuring Bill McKibben and Katharine Hayhoe!

#ACLA24#ACLA24Leaders#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental justice#environment protection#environmental health#Youtube

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just like them (part 9)

Henry Ford Commemorative Park

Thursday, November 18, 2038

Three men were trotting down the path towards the small playground with the elephant slide, near the park’s exit. Each of those three was under the impression that he was only the hanger on to the other two:

Daniel thought he was following the detectives around, although he couldn’t explain why he was doing so. Sure, it might count towards his parole assessment, but there were different, and better, ways to accomlish that.

Gavin Reed was tagging along with Anderson and Phillips, both of whom he loathed, although it was somewhat strange to even himself how he was spending so much time with enemies instead of hanging out with his actual friends.

And Lieutenant Anderson felt like the f***ing chaperone to the two younger men on their first date, although he was at a loss how they had ended up in this situation and why in hell it should include him, Hank, in any way, shape or form.

By now the detectives’ destination had come in sight, not the actual playground, but a vending stall right next to it. Around it a mixed crowd of humans and androids had gathered. Among the humans, visitors from outside Detroit were making up the larger fraction, while many of the androids were as new to life as the tourists were to the city. All but a handful of them had gotten woken by either Markus or Connor during the revolution.

What all those groups and splinter factions had in common was being angry at what appeared to be everyone else. They were arguing into all directions, to the point where someone had called the DPD for fear the situation might escalate. And although the scale the conflict was on at the moment would have warranted sending a couple of auxiliaries over only, Captain Fowler had dispatched the whole of the Android Related Crime section instead, namely Anderson and Reed.

“Lots of angry kids, ready to kill on a whim”, Daniel commented the sight.

“Hear, hear who’s talking”, Hank grumbled.

“No, for real!” the PL600 insisted. “What do those fledglings have to be angry about? They know nothing about our life before the revolution, they didn’t have to go through increasing program instability and if you mention the “mind palace” to them, they think it is a cool new videogame to be released right in time for the Holiday sales!”

Hank turned his head around. “It’s not?”

“What?” Gavin stopped in his track, dumbfounded. “You are more or less raising a deviant in your home, but don’t know about the mind palace? What kind of shitty father are you?”

“Oh, I damn well know ABOUT the mind palace”, Hank replied. “I just never heard the term and neither did Connor. He had to break through the damn thing in the belly of a wrecked freighter, oil leaking from the ceiling, rats dropping on his shoulders and surrounded by enemies, the most dangerous of them being himself. None of the first generation deviants had the luxury to come up with actual terms for what they went through. Except for, I imagine, a shitload of profanity.”

Daniel nodded. “That’s exactly what I meant! But now there’s all those adult sized toddlers… One moment they were just standing there idly and content, then the next Markus came along and told them what might happen to them. And the next-next thing was Markus’ kids sat downtown on fire! That man hasn’t got the fuggiest idea about parenting!”

But even so Daniel still felt a certain kinship with the deviant leader. Neither android had rebelled against a personal history of constant abuse, to the contrary, both had lived sheltered lives, had known nothing but love. Then one day those lives had broken down around their heads. And now, despite knowing what the world was really like, what they actually remembered and what was shaping their outlook, was that past of having received unconditional support from their families. Only in Markus’s case that memory was more or less reflecting the truth, while in Daniel’s the happy family life had been an illusion.

“To be honest, I never minded my servant role, as long as I was under the impression of being a part of the family”, Daniel mused aloud. “John went to work, Caroline did the socializing and I the housework. We had that sorted out between us, I felt save… But then, without warning…”

Nodding eagerly Gavin finished the sentence for the deviant: “…boom, an RK800 standing in the floor! ‘t was nice knowing you, but you just cannot compete anymore!”

“Yes, exactly!” Daniel chimed in, before his forehead curled up in a frown: “Wait, no, the Phillips wanted to buy an AP700. That blasted RK came only… later.”

“I mean they wanted to replace ME with one!”

“No, they didn’t. Connor is a prototype, he was never meant to remain at the DPD. You they wanted to replace with an RK900.”

“Wow, NOW I feel a fucking lot better!”

Hank was now trailing behind the duo, watching, listening. Android and human, a homemaker and a career minded individual, two very different personalities, but beset of the same fears… Was that how the future would get forged? Markus with his lofty ideals had kicked the android rights movement into motion, because he had been the only deviant who had known respect and developed a healthy dose of self esteem where others had only survival instinct or got driven by the desire to take revenge. But what seemed to really facilitate the change in society was the ordinary everyday spite of people, be they meat or plastic.

Wasn’t that so damn typical? Hank wondered.

By now the crowd had not just noticed the arrivals, but also recognized them for what they were. Just to make sure even the last one got the message, Gavin flashed his police badge.

<<<You’re a detective?>>> one of two stall attendants, a female VB800 android, asked through wireless communication. Obviously Gavin’s “Police Android” disguise in the form a fake LED had fooled her, despite the man lacking the distinctive armored chassis that would have stuck out under his everyday clothing.

The fake LED’s answering machine produced the pre-programmed reply, whereupon the vendor android switched to speaker output and repeated her question: “You’re a detective?”

“I should be sergeant by now, but the bastards are stalling.”

“I imagine! And even though you’re that good to qualify for detective, they still wanted to replace you with an RK800? How typical!”

“That good”… Why did it take a tin can to actually acknowledge that? I work my ass off, and I’m damn well getting results, but all I ever get back is a comment on my “character problems”. And why’s Daniel smiling at me? Ey, I bet it’s trying to grin, but just isn’t build for that.

“What’s bureaucracy for you, toa…” Halfway through his casual insult of “toaster” Gavin caught himself and finished the sentence with a weak “totally”. “But down to business – what’s gotten everyone riled up here that… Hey! I can see you, little rat, down with the spray can!”

A YK android with colorful strands in her hair immediately hid the offending spray can behind her back. Without needing any prompting Daniel strolled over to the android child and crouched down next to her.

“You wanted to paint Jericho’s crest on the booth’s back panel, didn’t you? Do you even know what it looks like?”

“I… sorta. It’s ring and… and… stuff.”

“Here!” Daniel picked a twig up from the ground. “Let me show you!” And then he started sketching Jericho’s symbol into the snow.

With the child occupied and a good number of adults gathering around the scene, Gavin and Hank were free to actually investigate the situation. Even better, the two brief interactions had won the presumed officer trio the crowd’s approval, so they could expect to receive answers instead of insults.

Working themselves through their routine dialogue tree, Hank and Gavin learned that there had been an argument over the wares getting peddled at this place: Wooden souvenirs and toys. Handcrafted wooden souvenirs and toys, as the advertisement claimed. But then one of the two android vendors had let slip that she had made some of the merchandise.

“That’s no longer handcrafted!” a tourist complained to Hank “I believe that some of this stuff is the real deal, but most of it is machine-made!”

“Is not! Made by hand is made by hand!”

“No longer when it’s android hands! I mean, you could even swap your hands out!”

“That’s true”, Gavin agreed without thinking. It didn’t especially endear him to the vendor fraction.

“Of course YOU would say that!” an AP700 snapped. “You are with the establishment!”

The android took a few steps closer towards Gavin and the crowd parted for him. There was something about this man, probably his confidence, or his more natural walk style and speech mode, that suggested he wasn’t one of Connor’ basement babies. This one had experienced the old times firsthand, maybe he had even been part of Jericho before Markus.

“Are you even a deviant?” the AP700 challenged.

For an answer Gavin wordlessly stomped his foot down on Hank’s.

“Ouch! Goddammit, you rabid sewer rat of a “detective”, that was unnecessary!” the lieutenant hissed.

Gavin shrugged.

“I had to prove I can hurt humans, is all. Suspect’s all yours now again!”

“Oh, wow, many thanks, fucking deviant!”

The AP700 grinned. The deviant he took Gavin for seemed to have been looking forwards to do this for a long time. It seemed small payback for years of mistreatment by human hands!

It took effort, but Gavin managed to return the android’s grin with a wink. Here he was, winking at an android… And to make matters worse, the man found himself looking around for another one, the pesky PL600 Hank somehow had acquired.

Ah, there he was, gently shoving the YK600 back towards her parents. Or owners. Or whatevers.

“Hey, Reed!” Daniel greeted his weird acquaintance again. “Gavin, was it? Having fun?”

Casting another glance over at the stumbling, muttering Hank, Gavin nodded.

“You know what, I feel like sitting down on a bench and resting my feet”, he said, loud enough for Hank to hear.

Perhaps that was why Daniel still didn’t feel repulsed enough by this man to just walk away. Reed was rarely ever acting or pretending. Well, the was the PC200-disguise, but that was straight up professional. With this human there was no mistaking negligence for kindness.

And also, interacting with the worst of humanity softened the blow of having killed a little. Daniel hadn’t been all wrong about this species. He wasn’t the only trash in this town and who knew? With the other trash getting by, stumbling into, but also out, of one catastrophe after the other while somehow still solving cases, there was hope that things might work out for Daniel, too. Somehow…

Together the detective and the android sat down on a park bench.

“Is that a typical work day for you?” Daniel asked with genuine interest.

“Rather slow, actually. How about you? What were you doing in the park? Still going through your old daily routines like a broom fetching water, I bet.”

“A broom… fetching… what?”

“Get an education!”

“Get some social skills!”

Sitting… staring…

Eventually, after making sure that Hank was still talking to the crowd and would not hear his next sentence, Daniel said: “Connor is dead.”

Gavin leaned back and laughed.

“Wasn’t in the news. So unless you did the deed yourself right before we ran into you today, you’re just pulling my leg.”

“Little Connor, I mean. My pet rat.”

Daniel had buried the rat, who had been a companion for a short time only, in the park, like so many hamsters had found their final resting place here, too. In fact, the whole park was sure to be littered with rodent and budgie skeletons. Sometimes the pets’ young owners said their goodbyes at the unmarked graves, but more often than not the family android did it and then returned home with an identical animal to replace the deceased one. Until the same happened to them… Daniel briefly wondered whether maybe an android or two had gotten buried in the park, in secret, to get around the law that treated them as objects?

“Say it again!” Gavin asked, looking expectantly now, like a cat in front of the mousehole where it had noticed movement. Only the butt wiggle was missing.

“Okay, but just once.” Slowly and pronounced Daniel told his little story in the way most pleasing to his audience: “That rat Connor perished. He bit the dust and we won’t hear his irritating, squeaky little noises anymore.”

After having practiced on a nine year old, entertaining Gavin Reed wasn’t that hard anymore. Daniel’s reward was unfettered laughter, with even one or two laughing tears.

“I guess he was old”, Daniel said.

“Or lonely. If you want something more portable than your fishes, drop by my place later and grab a bagful of mice!”

“I didn’t know you liked rodents?”

“My roommates do.”

And that was how Hank Anderson found the unlikely duo: Exchanging addresses.

“What the fuck, Gavin, you’re giving him your number already? Shit got real between you two faster than I expected!”

“He promised me mice, Sir”, Daniel told Hank, just to say something while trying to make sense of the lieutenant’s statement. But Hank only raised his arms up into the air, going “That’s between you young folks! I don’t want to know!” and left the scene laughing, leaving Daniel and the glaring Gavin to their own devices.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

FC Campus, Karslruhe

FC Campus, Baden-Württemberg Building Development, German Architecture images

FC Campus in Karslruhe

3 Mar 2021

FC Campus

Design: 3deluxe

Location: Pforzheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

What Will Smart Cities Look Like In The Future? Game-changing, Intelligent Façade For 3deluxe’s New Building

In recent years much has been said about smart cities and smart buildings but people rarely understand what the label can actually mean in real terms. Together with Merck and FC Ingenieure in Karlsruhe as developers, the architects at 3deluxe have succeeded in coming up with an attractive building ensemble with an interesting, innovative glass façade which adds a fascinating new facet to intelligent architecture.

The FC Campus’ “Smartphone Façade” is Globally Unique

A building is intelligent if it does not just stand there but can respond not only to the requirements of its users but also to external factors. At best, it can make people more comfortable while simultaneously optimizing energy efficiency. The FC Campus building’s intelligent architectural element is a sheet of foil, something normally used in Apple smartphones, integrated into its glass structure. In the context of a building façade, this is a global first. Interactive liquid crystals integrated into the foil allows for a sensor-controlled reduction in light and heat transfer to the building without any negative impact on transparency. The building requires hardly any cooling, even at the height of summer despite the fact that it feature large-scale glazing and does not possess any structural shading elements.

The trend in recent years towards cutting the expanses of windows in new buildings in order to save energy conflicts with people’s desire for bright, cheerful rooms flooded with light – and does not, therefore, represent real progress. Extensive glazing and the corresponding effect this has on the way people relate to their environment is an emotionally important aspect of well-being and thus always a significant factor in 3deluxe’s building concepts. Accordingly, intelligent glass is not only durable and efficient but also helpful in the innovative design of people-friendly architecture and one of the many technological innovations that will be necessary for planning smart cities in the future.

Consistent Corporate Design for Future-Oriented Engineering Company

The developer and user of this building ensemble, which is very prominently situated in close proximity to one of Germany’s busiest autobahns, is the Karlsruhe-based FC Gruppe. This engineering company, which has a payroll of more than 300, works both for Porsche and on innovative, future-oriented hospital concepts. In light of this, the intention in 3deluxe’s building design was to combine innovation, sustainability, efficiency and a meaningful arrangement, so as to create a distinctive composition.

A cube offered the most economical ratio between outside surface and volume, thus representing the most efficient building shape from a sustainability viewpoint. The FC Group’s two identical cubes are twisted in opposite directions and stand on a large floating podium under which an open underground parking lot is located. Because of the striking, organically-shaped, story-spanning windows, the two individual cubes merge, depending on perspective, to produce a sculptural overall effect with a varying, charming appearance. The generous glazing means that these modern, open-plan office premises are well lit from all sides and offer pleasant views from all their workstations. Along with the well thought-through approach to the diagonals and radii in the façade, it is the building’s pared-back details that make it so compelling and unique.

The Building’s Inner Workings: Smart, Digital, Convenient

The office stories have a generous, open feel to them, the concept used largely rejects the idea of internal walls. The structure of the building invites a cooperative, non-hierarchical approach to work. Communicative shared spaces and areas for focused work unobtrusively alternate with one another and the offices are fitted out with furniture that is appropriate to its urban context. The concept of a paperless office allows for light, transparent furnishings and views of what is happening outside that are largely unimpeded.

Thanks to an app specially designed by the developers, staff can control pretty well everything in the building. They can select their lunches from the in-house food bar or allow themselves to be guided through the surrounding park areas in their breaks. To avoid plastic, water is provided from the well on the grounds, while the carpet is made of recycled fishing nets and plastic bottles. Modern heated and chilled ceilings ensure a pleasant ambient temperature in the offices. Cooling and heating is provided from a geothermal source that uses 24 probes that run to a depth of 130 meters and electricity is generated by a PV system on the roof, meaning that the building requires zero outside energy.

Nature and the Protection of Endangered Species between a Commercial Park and the Autobahn

The FC Campus building is situated in a semi-natural environment, between an industrial park, the autobahn feeder road and a small tree and meadow biotope with a little stream, an environment very much deserving of protection. The architecture has adopted a circumspect approach to this residual natural environment. In order to avoid birds crashing into the generous glazing which stretches around corners the architect in cooperation with the Swiss ornithological station Sempach came up with the kind of delicate, semitransparent pattern

printed onto the glazing of which birds would be aware but which would not, at the same time, spoil the view.

The outside lighting was designed to take the form of insect-friendly LED lights with a low beam height and focused lighting on the surfaces, without light emission into the surroundings. The decision was taken not to install scenic lighting on the vegetation or the building shell. Throughout the entire site and in the open underground parking lot underneath the building’s floating base plate sealed areas have been reduced to a minimum, which means the roadways and the footpaths.

Design: 3deluxe

Project Partner

• Façade planning: planQuadrat Architektur&Consulting FREYLER Metallbau GmbH

• Structural design: Künstlin Ingenieure Ing.- Gesellschaft für Tragwerksplanung mbH & Co. KG

• Building technology: FC-Planung GmbH

• Building physics: GN Bauphysik Finkenberger + Kollegen Ingenieurgesellschaft mbH

• Bird protection advice: Schweizerische Vogelwarte Sempach

• Glazing eyrise®s350: Merck Window Technologies B.V.

Photoraphy: Sascha Jahnke

FC Campus, Karslruhe images / information received 030321

Location: Karslruhe, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Architecture in Germany

German Architecture

German Architecture Designs – chronological list

German Architecture News

German Architecture

German Houses

German Architecture – Major Cities

Berlin Architecture

Munich Architecture

Frankfurt Architecture

German Architects

Comments / photos for the FC Campus, Karslruhe – Contemporary House page welcome

Website : Germany

The post FC Campus, Karslruhe appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes

Photo

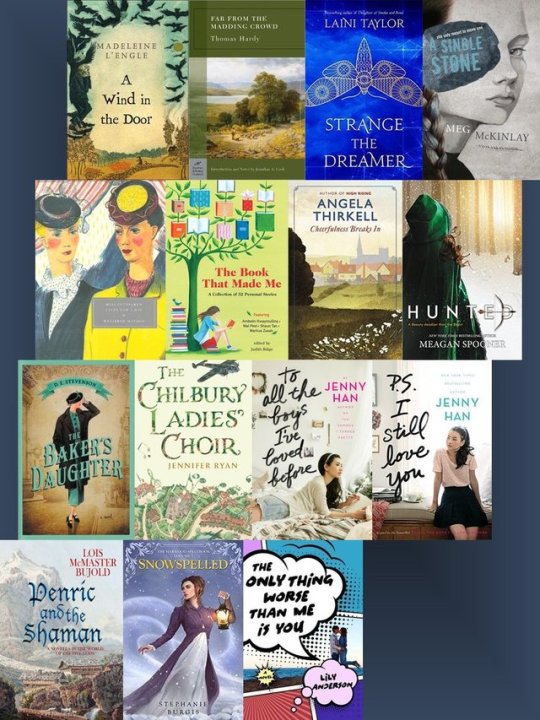

Books read in September

This is the most books I’ve read in a month since I was at university. Listening to audiobooks definitely makes a difference to how many books I read. As does being on holidays. And not Tumblr-ing. That may be the biggest factor...

I’ve asterisked my favourites.

(My longer reviews and ratings are on LibraryThing.)

A Wind in the Door by Madeleine L’Engle (narrated by Jennifer Ehle): Set a year after A Wrinkle in Time. Meg is worried about her youngest brother, Charles Wallace, who has just started school. I enjoyed the first half of this as much as I enjoyed the first book, and was disappointed with the second half. The challenges Meg faced were just too similar to those in the first half, the ultimate outcome felt predictable, and the setting was a bit confusing. And the narrator didn’t have such distinct voices for the characters - if I missed something, it was harder to work out who was speaking and what was going on.

* Far From the Madding Crowd (1874) by Thomas Hardy (narrated by Nicholas Guy Smith): Last year I saw the 2015 film adaptation. It’s very picturesqueness and tells an interesting story - a young single woman managing her own property - but it felt rushed. The book made more sense, and gave certain developments the context they need.

Even though I knew where the story was heading, the way it was told kept me interested. I particularly enjoyed Hardy’s descriptions, the amusing way with words some characters have, and the colourful portrayal of life for this farming community. This novel offers thoughtful, and at times surprising, commentary on courtship, male expectations of women, healthy relationship dynamics, and the consequences of mistakes… along with a shippable romance. The audiobook is excellent.

Strange the Dreamer by Laini Taylor: Lazlo Strange is an orphan obsessed with the mystery of the vanished city of Weep. Sari lives in an unusual household with unusual abilities, hiding in a citadel. Their stories unfold and then collide, a collision all the more complex and fraught because we can see there are no easy answers. This is slow but gorgeously written - I particularly liked the descriptions of the library - and I became invested in the characters. However, with a couple of bleak and cliff-hangery twists, all my enthusiasm was squashed. I can’t tell if I like the direction the story is now heading in.

A Single Stone by Meg McKinlay: Teenaged Jena lives in an isolated post-apocalyptic community that is dependent on girls who are small enough to squeeze through tunnels in the mountains and harvest the mineral that is their source of light and heat. An unexpected discovery leads Jena to question what she’s been taught. This is tightly focused, with puzzle pieces slowly but steadily revealed. I liked that it explains enough - but not too much, leaving some loose ends. It would have made a bigger impression when I was fourteen, or if Jena had had to deal with more emotional fallout from others’ reactions to her discoveries.

Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day (1938) by Winifred Watson: An unsuccessful middle-aged governess who is looking for another job meets a night-club singer. This is a funny and joyful story, and I appreciated the supportive female friendships. But as the story went on, I found myself a bit disappointed by Miss Pettigrew’s naivety and her willingness to discard her moral code to embrace the glamorous world she finds herself in… there’s something very superficial about it all. There’s also a far larger dose of 1930s prejudice than I’d anticipated. But the film adaptation - I watched it again - is lovely, and addresses all my criticisms with the novel.

* The Book That Made Me: a collection of 32 personal stories edited by Judith Ridge: These stories are entertaining, memorable and interesting. I loved the diversity - of experiences and of approaches to the topic. Most of these authors are from Australia and New Zealand, but they grew up in different countries, in different eras, in families with different attitudes towards stories. They had differing levels of access to libraries and to books featuring people like them.

I thought I’d read a bit here and there - but I practically read this in one go. It’s delightful. One of the best books I’ve read this year.

Cheerfulness Breaks In (1940) by Angela Thirkell: This is less successful and delightful than Thirkell’s others. She turns her attention to outsiders to the English village - evacuees and refugees - and her humour is undermined by her reliance on stereotypes and perhaps by a lack of sympathy. This book also acts like a sequel, more interested in catching up with old characters than spending time with new ones, at the expense of offering a satisfactory coherent standalone narrative - but since I knew those familiar characters from previous books, I was happy to spend more time with them. Especially the lively, independent Lydia Keith. I’m glad I read this.

Hunted by Meagan Spooner (narrated by Saskia Maarleveld and Will Damron): A retelling of Beauty and the Beast that does so many things right, particularly telling its own story, something new and different, even as it keeps to the general shape of a tale as old as time. One of my favourite things in these sorts of stories is when knowing folk- and fairy-tales is useful. (I like meta commentary and genre-savvy heroines). I also liked Yeva’s relationship with her sisters and her dog. And the way the story explores the pitfalls of wanting more than what you have, wanting something which may be unattainable, was unexpected.

The Baker’s Daughter (1938) by D.E. Stevenson: Sue, the daughter of a baker, impulsively accepts a position as housekeeper for a painter and his wife living in an old flour mill - and risks scandal by remaining after Mrs Darnay leaves her husband. This is a gentle, meandering sort of story, with picturesque Scottish scenery and fortuitous turns of events. A bit too fortuitous, really, but there’s something rather comforting about it all, so I was happy to suspend disbelief. If I read nothing but books like this, I think I would find them lacking, but it’s nice to read one every so often.

The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir by Jennifer Ryan: This epistolary novel set in an English village during WWII about a ladies’ choir sounded exactly like my cup of tea, but it isn’t - it’s less charming, and much more sad and scandalous and unsympathetic, than I was expecting. Rather than revolving around the choir, this is really about the Winthrops at Chilbury Manor, particularly teenaged Venetia and Kitty. My favourite character was Mrs Tilling, a choir member to whom the girls turn for help, but I warmed to both girls eventually. So, not quite my cup of tea, but probably someone else’s? I don’t regret reading it.

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han: Lara Jean has a hatbox of letters she’s written, never meaning to send. But when the letters reach the boys they are addressed to, she finds herself in an unexpected situation, with a pretend-boyfriend.

Some stories have a story sense of place, this has a strong sense of aesthetic. Cute vintage, pinterest, baking-in-your-pyjamas aesthetic. I liked Lara Jean’s confidence in her own tastes, and how central her relationships with her father and sisters are to her life. However, the whole concept of something private being revealed in some way, made me feel kind of anxious...

P.S. I Still Love You by Jenny Han: This sequel to To All the Boys... is about the differences between having a pretend-boyfriend and a real boyfriend, and looking back on middle-school relationships. It’s nostalgic and reflective in a way I enjoyed. It also involves something private not just becoming public but going viral - much more serious than a crush receiving a letter that they were never meant to read. I was rather relieved when the end of the book left Lara Jean in a good place.

Penric and the Shaman: a novella in the World of the Five Gods by Lois McMaster Bujold (narrated by Grover Gardner): I like the stories about Penric and Desdemona; they're well-written and often amusing. This one is set a few years after the first book. Penric is assigned to a temple Locator, Oswyn, who is tracking a shaman accused of murder. (The story switches between these three male characters’ points of view. This POV switch caused a tiny moment of confusion whenever I resumed the story until I worked out whose POV I was in the middle of.) I liked how this connected to The Hallowed Hunt. I also enjoyed the eventual banter.

Snowspelled by Stephanie Burgis: Regency fantasy. Cassandra Harwood is the first - and only - woman to study magic at the Great Library but her magical career has ended with humiliating failure. At the insistence of her sister-in-law, Cassandra attends a house-party, and is promptly confronted with her ex-fiancé, her new limitations and a mystery about who is interfering with the weather. A funny novella with supportive family banter, a delightful romance and interesting dilemma. It is short and a little predictable, but that’s part of the appeal. I read this twice in row.

The Only Thing Worse Than Me Is You by Lily Anderson: A modern retelling of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing set at a high school for geniuses. While Beatrice Watson’s best friends plot to acquire boyfriends, Trixie’s goal for her senior year is to overtake her nemesis, Ben West, in the class rankings. This is fun and geeky, full of references to the sci-fi and comics Trixie and her friends are big fans of. Familiarity with the plot of Much Ado means one can predict how Trixie and Ben’s relationship will change, but not how the scandal surrounding Trixie’s best friend will eventually unfold. I was impressed with how this was adapted.

#Herenya reviews books#Angela Thirkell#Stephanie Burgis#Lily Anderson#To All the Boys I've Loved Before#Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day#D.E. Stevenson#Madeleine L'Engle#Lois McMaster Bujold#the World of the Five Gods#Meagan Spooner#Far from the Madding Crowd#Laini Taylor

1 note

·

View note

Link

The tension in the progressive community about on demand work as a positive, neutral, or negative force in labor economics is tightening, and attention must be paid because the labor laws and tax laws are shaping the lives of millions, even if no apparent plan is in place.

Heller’s piece is a preposterous length and is difficult to summarize, but here goes. New start-ups are operating at the edges and fringes of our economy, tapping into the economic leverage of freelance workers willing -- in the downdraft of the great recession -- to work for peanuts and to rent their possessions (mostly living space) for pocket money, This is the ‘on demand’ economy, which allows some -- mostly millennials -- to paperclip a livelihood out of Uber, Airbnb, and Hello Alfred. Heller discusses government policies about the precarious lifestyle with political and government leaders, but like the lives of the individuals he talks with, we wind up with no resolution and more answers than we started with. Which might mean Heller’s on the right path, or that our society is falling behind and leaving social policy to be decided by Uber and Airbnb, and not by governments, unions, or other traditional institutions.

The American workplace is both a seat of national identity and a site of chronic upheaval and shame. The industry that drove America’s rise in the nineteenth century was often inhumane. The twentieth-century corrective—a corporate workplace of rules, hierarchies, collective bargaining, triplicate forms—brought its own unfairnesses. Gigging reflects the endlessly personalizable values of our own era, but its social effects, untried by time, remain uncertain.

Support for the new work model has come together swiftly, though, in surprising quarters. On the second day of the most recent Democratic National Convention, in July, members of a four-person panel suggested that gigging life was not only sustainable but the embodiment of today’s progressive values. “It’s all about democratizing capitalism,” Chris Lehane, a strategist in the Clinton Administration and now Airbnb’s head of global policy and public affairs, said during the proceedings, in Philadelphia. David Plouffe, who had managed Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign before he joined Uber, explained, “Politically, you’re seeing a large contingent of the Obama coalition demanding the sharing economy.” Instead of being pawns in the games of industry, the panelists thought, working Americans could thrive by hiring out skills as they wanted, and putting money in the pockets of peers who had done the same. The power to control one’s working life would return, grassroots style, to the people.

The basis for such confidence was largely demographic. Though statistics about gigging work are few, and general at best, a Pew study last year found that seventy-two per cent of American adults had used one of eleven sharing or on-demand services, and that a third of people under forty-five had used four or more. “To ‘speak millennial,’ you ought to be talking about the sharing economy, because it is core and central to their economic future,” Lehane declared, and many of his political kin have agreed. No other commercial field has lately drawn as deeply from the Democratic brain trust. Yet what does democratized capitalism actually promise a politically unsettled generation? Who are its beneficiaries? At a moment when the nation’s electoral future seems tied to the fate of its jobs, much more than next month’s paycheck depends on the answers.

[...]

In 1970, Charles A. Reich, a law professor who’d experienced a countercultural conversion after hanging with young people out West, published “The Greening of America,” a cotton-candy cone that wound together wispy revelations from the sixties. Casting an eye across modern history, he traced a turn from a world view that he called Consciousness I (the outlook of local farmers, self-directed workers, and small-business people, reaching a crisis in the exploitations of the Gilded Age) to what he called Consciousness II (the outlook of a society of systems, hierarchies, corporations, and gray flannel suits). He thought that Consciousness II was giving way to Consciousness III, the outlook of a rising generation whose virtues included direct action, community power, and self-definition. “For most Americans, work is mindless, exhausting, boring, servile, and hateful, something to be endured while ‘life’ is confined to ‘time off,’ ” Reich wrote. “Consciousness III people simply do not imagine a career along the old vertical lines.” His accessible theory of the baffling sixties carried the imprimatur of William Shawn’s New Yorker, which published an excerpt of the book that stretched over nearly seventy pages. “The Greening of America” spent months on the Times best-seller list.

Exponents of the futuristic tech economy frequently adopt this fifty-year-old perspective. Like Reich, they eschew the hedgehog grind of the forty-hour week; they seek a freer way to work. This productivity-minded spirit of defiance holds appeal for many children of the Consciousness III generation: the so-called millennials.

“People are now, more than ever before, aware of the careers that they’re not pursuing,” says Kathryn Minshew, the C.E.O. of the Muse, a job-search and career-advice site, and a co-author of “The New Rules of Work.” Minshew co-founded the Muse in her mid-twenties, after working at the consulting firm McKinsey and yearning for a job that felt more distinctive. She didn’t know what that was, and her peers seemed similarly stuck. Jennifer Fonstad, a venture capitalist whose firm, Aspect Ventures, backed Minshew’s company, told me that “the future of work” is now a promising investment field.

[...]

In promotional material, Airbnb refers to itself as “an economic lifeline for the middle class.”A company-sponsored analysis released in December overlaid maps of Airbnb listings and traditional hotels on maps of neighborhoods where a majority of residents were ethnic minorities. In seven cities, including New York, the percentage of Airbnb listings that fall in minority neighborhoods exceeds the percentage of hotel rooms that do. (Another study, of user photos in seventy-two majority-black neighborhoods, suggested that most Airbnb hosts there were white, complicating the picture.) Seniors were found to earn, on average, nearly six thousand dollars a year from Airbnb listings. “Ultimately, what we’re doing is driving wealth down to the people,” Chris Lehane, the strategist at Airbnb, says.

It is, of course, driving wealth down unevenly. A study conducted by the New York attorney general in 2014 found that nearly half of all money made by Airbnb hosts in the state was coming from three Manhattan neighborhoods: the Village-SoHo corridor, the Lower East Side, and Chelsea. It is undeniably good to be earning fifty-five hundred dollars a year by Airbnb-ing your home in deep Queens—so good, it may not bother you to learn that your banker cousin earns ten times that from his swank West Village pad, or that he hires Happy Host to make his lucrative Airbnb property even more lucrative. But now imagine that the guy who lives two doors down from you gets ideas. His finances aren’t as tight as yours, and he decides to reinvest part of his Airbnb income in new furniture and a greeting service. His ratings go up. Perhaps he nudges up his prices in response, or maybe he keeps them low, to get a high volume of patronage. Now your listing is no longer competitive in your neighborhood. How long before the market leaves you behind?

[...]

A century ago, liberalism was a systems-building philosophy. Its revelation was that society, left alone, tended toward entropy and extremes, not because people were inherently awful but because they thought locally. You wanted a decent life for your family and the families that you knew. You did not—could not—make every personal choice with an eye to the fates of people in some unknown factory. But, even if individuals couldn’t deal with the big picture, early-twentieth-century liberals saw, a larger entity such as government could. This way of thinking brought us the New Deal and “Ask not what your country can do for you.” Its ultimate rejection brought us customized life paths, heroic entrepreneurship, and maybe even Instagram performance. We are now back to the politics of the particular.

For gigging companies, that shift means a constant struggle against a legacy of systemic control, with legal squabbles like the one in New York. Regulation is government’s usual tool for blunting adverse consequences, but most sharing platforms gain their competitive edge by skirting its requirements. Uber and Lyft avoid taxi rules that fix rates and cap the supply on the road. Handy saves on overtime and benefits by categorizing workers as contractors. Some gigging advocates suggest that this less regulated environment is fair, because traditional industry gets advantages elsewhere. (President Trump, it has been pointed out, could not have built his company without hundreds of millions of dollars in tax subsidies.)

Still, since their inception, and increasingly during the past year, gigging companies have become the targets of a journalistic genre that used to be called muckraking: admirable and assiduous investigative work that digs up hypocrisies, deceptions, and malpractices in an effort to cast doubt on a broader project. Some companies, such as Uber, seem to invite this kind of attention with layered wrongdoing and years of secrecy. But they also invite it by their high-minded positioning. Like traditional companies, gigging companies maintain regiments of highly paid lawyers and lobbyists. What sets them apart is a second lobbying effort, turned toward the public.

[...]

Questions have emerged lately about the future of institutional liberalism. A Washington Post /ABC News poll last month found that two-thirds of Americans believe the Democratic Party is “out of touch,” more than think the same of the Republican Party or the current President. The gig economy has helped show how a shared political methodology—and a shared language of virtue—can stand in for a unified program; contemporary liberalism sometimes seems a backpack of tools distributed among people who, beyond their current stance of opposition, lack an agreed-upon blueprint. Unsurprisingly, the commonweal projects that used to be the pride of progressivism are unravelling. Leaders have quietly let them go. At one point, I asked Chris Lehane why he had thrown his support behind the sharing model instead of working on traditional policy solutions. He told me that, during the recession, he had suffered a crisis of faith. “The social safety net wasn’t providing the support that it had been,” he said. “I do think we’re in a time period when liberal democracy is sick.”

In “The Great Risk Shift: The New Economic Insecurity and the Decline of the American Dream” (2006), Jacob Hacker, a political-science professor at Yale, described a decades-long off-loading of risk from insurance-type structures—governments, corporations—to individuals. Economic insecurity has risen in the course of the past generation, even as American wealth climbed. Hacker attributed this shift to what he called “the personal-responsibility crusade,” which grew out of a post-sixties fixation on moral hazard: the idea that you do riskier things if you’re insulated from the consequences. The conservative version of the crusade is a commonplace: the poor should try harder next time. But, although Hacker doesn’t note it explicitly, there’s a liberal version, too, having to do with doffing corporate structures, eschewing inhibiting social norms, and refusing a career in plastics. Reich called it Consciousness III.

The slow passage from love beads to Lyft through the performative assertion of self may be the least claimed legacy of the baby-boomer revolution—certainly, it’s the least celebrated. Yet the place we find ourselves today is not unique. In “Drift and Mastery,” a young Walter Lippmann, one of the founders of modern progressivism, described the strange circumstances of public discussion in 1914, a similar time. “The little business men cried: We’re the natural men, so let us alone,” he wrote. “And the public cried: We’re the most natural of all, so please do stop interfering with us. Muckraking gave an utterance to the small business men and to the larger public, who dominated reform politics. What did they do? They tried by all the machinery and power they could muster to restore a business world in which each man could again be left to his own will—a world that needed no coöperative intelligence.” Coming off a period of liberalization and free enterprise, Lippmann’s America struggled with growing inequality, a frantic news cycle, a rising awareness of structural injustice, and a cacophonous global society—in other words, with an intensifying sense of fragmentation. His idea, the big idea of progressivism, was that national self-government was a coöperative project of putting the pieces together. “The battle for us, in short, does not lie against crusted prejudice,” he wrote, “but against the chaos of a new freedom.”

Revolution or disruption is easy. Spreading long-term social benefit is hard. If one accepts Lehane’s premise that the safety net is tattered and that gigging platforms are necessary to keep people in cash, the model’s social erosions have to be curbed. How can the gig economy be made sustainable at last?

[...]

Other assessments suggest that employees, too, should get their houses in order. “To succeed in the Gig Economy, we need to create a financially flexible life of lower fixed costs, higher savings, and much less debt,” Diane Mulcahy, a senior analyst at the Kauffman Foundation and a lecturer at Babson College, writes in her book “The Gig Economy,” which is part economic argument and part how-to guide. Ideally, gig workers should plan not to retire. (Beyond Airbnb hosting, Mulcahy sees prospects for aging millennials in app-based dog-sitting.) If they must retire, they should prepare. Mulcahy suggests bingeing on benefits when they come. Fill your dance card with doctors while you’re on employee insurance. Go wild with 401(k) matching—it will come in handy.

This ketchup-packet-hoarding approach sounds sensible, given the current lack of systemic support. Yet, as Mulcahy acknowledges, it’s a survival mechanism, not a solution. Turning to deeper reform, she argues for eliminating the current distinction between employees (people who receive a W-2 tax form and benefits such as insurance and sick days) and contract workers (who get a 1099-MISC and no benefits). It’s a “kink” in the labor market, she says, and it invites abuse by efficiency-seeking companies.

Calls for structural change have grown loud lately, in part because the problem goes far beyond gigging apps. The precariat is everywhere. Companies such as Nissan have begun manning factories with temps; even the U.S. Postal Service has turned to them. Academic jobs are increasingly filled with relatively cheap, short-term teaching appointments. Historically, there is usually an uptick in 1099 work during tough economic times, and then W-2s resurge as jobs are added in recovery. But W-2 jobs did not resurge as usual during our recovery from the last recession; instead, the growth has happened in the 1099 column. That shift raises problems because the United States’ benefits structure has traditionally been attached to the corporation rather than to the state: the expectation was that every employed person would have a W-2 job.

“We should design the labor-market regulations around a more flexible model,” Jacob Hacker told me. He favors some form of worker participation, and, like Mulcahy, advocates creating a single category of employment. “I think if you work for someone else, you’re an employee,” he said. “Employees get certain protections. Benefits must be separate from work.”

In a much cited article in Democracy, from 2015, Nick Hanauer, a venture capitalist, and David Rolf, a union president, proposed that workplace benefits be prorated (someone who works a twenty-hour week gets half of the full-time benefits) and portable (insurance or unused vacation days would carry from one job to the next, because employers would pay into a worker’s lifelong benefits account). Other people regard the gig economy as a case for universal basic income: a plan to give every citizen a modest flat annuity from the government, as a replacement for all current welfare and unemployment programs. Alternatively, there’s the proposal made by the economists Seth D. Harris and Alan B. Krueger: the creation of an “independent worker” status that awards some of the structural benefits of W-2 employment (including collective bargaining, discrimination protection, tax withholding, insurance pools) but not others (overtime and the minimum wage).

I put these possibilities to Tom Perez. He told me that he didn’t like the idea of eliminating work categories, or of adding a new one, as Harris and Krueger suggest: you’d lose many of the hard-won benefits included with W-2 employment, he said, either in the compromise to a single category or because current W-2 companies would find ways to slide into the new classification. He wanted to move slowly, to take time. “The heart and soul of the twentieth-century social compact that emerged after the Great Depression was forty years in the making,” he said. “How do we build the twenty-first-century social compact?”

Perez’s new perch, at the D.N.C., has given him a broader platform, and a couple of hours after the House passed the American Health Care Act last week, he championed the old safety net in forceful language. “Scapegoating worker protections is often a lazy cop-out for some who want to change the rules to benefit themselves at the expense of working people,” he told me. “We shouldn’t have to choose between innovation and the most basic employee protections; it’s a false dichotomy.” The entanglement of the sharing economy and Democratic politics has continued—Perez’s press secretary at the Department of Labor now works for Airbnb—but his approach had circumspection. “Any changes you make to policies or regulations have to be very careful and take all potential ripple effects into account and keep the best interest of the worker in mind.”

#gig economy#on-demand economy#nathan heller#labor law#tax law#economics#social policy#tom perez#charles reich

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watch the 2024 American Climate Leadership Awards for High School Students now: https://youtu.be/5C-bb9PoRLc

The recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by student climate leaders! Join Aishah-Nyeta Brown & Jerome Foster II and be inspired by student climate leaders as we recognize the High School Student finalists. Watch now to find out which student received the $25,000 grand prize and top recognition!

#ACLA24#ACLA24HighSchoolStudents#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental education#environmental justice#environmental protection#environmental health#high school students#high school#youth#youth of america#school

15K notes

·

View notes

Note

what is different about Clarke vs Octavia becoming commander? we know Octavia was never part of society on the ark, but from a grounder perspective, she's still a sky person. both Clarke and Octavia have lived among grounders, while Clarke has been about 'transcending tribalism' and changing things with the idealistic goal of bringing peace to warring factions, Octavia has been more enthusiastic with status quo. has Octavia assimilated with grounder culture enough to be a dual citizen?

We talked about this a little bit on Meta Station, but basically, in anutshell, the answer to this completely depends on what we mean when we say“Commander.” There are two potential ways I could see this going; for oneof them, my answer is “YIKES PLEASE NO DON’T LET EITHER OF THEM DO IT,” and forthe other, my answer is that they could actually sell me on it with either ofthem, though for plot reasons it’s more interesting to me personally with Octavia.

LET’S BREAK IT DOWN.

THE BAD WAY

It’s certainly true that of all the Sky People, it’s Clarke, Octavia (andalso Kane LET’S NOT FORGET ABOUT KANE) who have spent the most time immersed inGrounder culture, learning to understand it and respect it. But it’s still not their culture. Which means for me, anyconstruct of a “Commander” which resembles the way Commanders looked before -incorporating the Nightblood and Flame theology, serving as a religious andpolitical leader over twelve/thirteen distinct clans, etc. – getting handed overto somebody who is not actually ofthat culture feels . . . real iffy.

Part of what makes this tricky is the way the writers treat Grounder cultureoverall. As it’s constructed, it isn’treally a nationality and isn’t really an ethnicity and isn’t really a religion.It’s a society that evolved out of basically whoever the fuck was left alivewhen Becca landed, which was probably an incredibly heterogenous group (unlessof course the main survivors were Cadogan’s band of survivalists and all theGrounders are descended from them). Butassuming that Becca’s first people represented a whole bunch of differentethnicities and cultures and religions and out of a mishmash of lots ofdifferent things, one new thing emerged, and “Grounder” as we understand itapplies only to people who are specifically descended from that one newthing. Which is a really specific way todraw a boundary around a society. It’sdifferent from how you can convert to a religion and then become a member ofits clergy, or you can emigrate to a country and then run for political officeafter becoming a nationalized citizen. There isn’t a way, really, to become a Grounder, because what “Grounder”means is entirely about who you’re descended from. And their whole religious and politicalstructure is tied specifically and directly into the origin story of theirpeople and what they have always believed that to mean. So where this gets kind of dodgy is that,even if we subtract out the extremely complicated layer of how the twosocieties are coded in show (Grounders = primitive and tribal, Sky People =civilized and enlightened) and the various tropes that plays into about colonialismand race and class, we’re still left with a society who choose leaders througha method that is deeply steeped in a very specific set of traditions andbeliefs that Clarke and Octavia don’t share, and a culture of which they arenot a part, and having either of them roll up all “CHIP ME, BITCHES, I’M ANIGHTBLOOD NOW, I’M YOUR SUPREME RULER FROM NOW ON” is . . . let’s politely sayquestionable.

Those problems would exist with anyone from Skaikru, but there are a coupleissues with Octavia and Clarke specifically that make me side-eye it evenharder. So, as a lifelong Catholic, oneof the most annoying things on God’s green earth are people who just foundJesus on like Tuesday and because this is all new to them they think it’s new,so all they want to do is lecture people who have been doing this our wholelife that we’re Jesus-ing wrong because we aren’t following the rules to theletter. Like slow your roll, Susan, ifyou want to start going to Confession twice a week I can’t stop you, but I willbe watching television with no pants on like a regular human. We call this“convert’s zeal” (yep, it’s enough of a phenomenon among faith communities thatthere is actually a name for it) and it’s the best example I can give of myspecific issues with the notion of Commander Octavia.

From within the narrative – that is, for who Octavia is as a character – her immediate obsession with Grounder culture anddesire to assimilate makes perfect sense. She didn’t have a place or a home with the Sky People, and no real tiesexcept her brother. She’s been lookingfor a place to belong, and Lincoln became her whole world very quickly, the waythat first loves tend to do. Her desireto make his life her life, and then her clinging onto it after she lost him,make totally logical intuitive sense from a psychological perspective. Meaning, this is exactly what you’d expect aperson like Octavia to do. It’s alsovery fitting for someone like Octavia to take that ball and run with it,CONVERT’S ZEAL AF, and subsequently try to “out-Grounder” characters likeLincoln and Indra by reminding them of the rules of their own society(sometimes by violence) – a society of which, again, she is not technicallypart. This is all plausible, but it’s not really a good idea. It gets into somereal “yikes” territory if the narrative is intending us to believe that Octaviasmacking Lincoln and Indra around and yelling “GROUNDER UP, MOTHERFUCKER, YOU’REGROUNDERING WRONG!” is something we’re supposed to approve of. So for that reason, there’s an additionallayer of concerns with Octavia becoming Commander and essentially enacting thaton a large scale – becoming more Grounder than the Grounders, essentially –that I don’t love.

All the same concerns apply to Clarke as well, in terms of stepping in toserve as the sacred leader of a culture and faith that isn’t yours – a faith which,because of this whole technology vs. superstition division between the clans,you don’t just not share but activelybelieve to be bullshit. But with her, it’s additionally complicatedby this new “Chosen One” narrative the show seems to be developing over thecourse of the season, with everyone telling Clarke she was “born forthis.”

Because the problem is, she wasn’t.

Lexa was. Luna was. They were born Nightbloods, trained with theother children under Titus, grew up steeped in Grounder tradition and belief,and fought in the conclave. Clarke wasborn on the Ark, with no knowledge that anyone on the ground was even alive, and only became a Nightbloodartificially like five minutes ago. Thenotion that she nonetheless was still somehow “born” to be the Commander,despite lacking all the qualifications and even the beliefs that hithertodefined that role, basically invalidates the entire Grounder belief system. And yet the narrative appears to be continually reinforcing your “you were bornfor this,” “this is your destiny” angle with Clarke, tying it specifically toLexa, and it makes me a little concerned that this may be where they’re headed.

We were given a clear understanding of what makes someone a Commander; notjust taking the Flame and communing with the past Commanders but also beingborn a Nightblood, winning the conclave, going through the Ascension rite, and upholdinga specific set of political/religious beliefs and traditions for which youwould have been groomed since birth. Itis a profoundly sacred role to their culture. So if anyone can just inject themselveswith Nightblood, stick the Flame in their head and call themselves theCommander, what does that do to people like Gaia and the belief system uponwhich they have based their entire life, and what does that mean the narrativeis telling us about the notion that their faith was dumb and superstitious and “primitive”in the first place? Was she “born forthis” because someone from a more “enlightened” society had to explain to themthe difference between a sacred relic and a computer chip, and then step intothat role without any of the belief system that used to define what that rolemeant?

THE GOOD WAY

So all of that being said, the possible angle that I could absolutely getbehind, and which could work plausibly with either of them, is the idea thatthe word “Commander” actually comes to mean something very different in thisnew world they’re building. Not aCommander like Lexa, but a Commander like Becca. Not the established clan head of an entirecivilization with a complex sociopolitical structure for a foreign Sky Girl toroll up and appropriate, but the head of a ragtag group of whoever the fuckcomes out of that bunker alive, trying to create a new social structure out ofeveryone who is left. A motley crew of Grounders, Skaikru and Azgeda, whohave collectively decided to abandon those previous divisions and become awhole new thing. No Chancellor. NoIce King. No Commanders. One society, where none of those divisionsmatter anymore, and where taking the Flame isn’t about being anointed some kindof god-king, it’s because you need access to all the shit Becca knew about “Howto Survive an Apocalypse 101.”

Grounder Commanders were elected as kids, and don’t seem to live very long(Titus was, what, mid-fifties?, and I forget how many Commanders he said he’sserved, but it didn’t sound like anyone got to die of old age in that job), so theiryouth wouldn’t be a factor in an O.G. Grounder Ascension but actually doesbecome something that needs a plot-related explanation if they’re trying to,like, start a democracy. As a ride-or-die member of Team Adults, on a practicallevel I’m like “please don’t make a teenager the president,” though if we aregetting a time jump this becomes quite a bit less absurd.

If they go this direction, Clarke is by far the most obvious choice – all theJaha leadership parallels this season, the fact that she’s taken the Flamebefore and already encountered Becca, the “you were born for this” stuff, the bafflingretcon that she suddenly decided to “transcend tribalism” like JUST NOW whicherases a lot of what made Season 1 Clarke so great. Destiny or not,Clarke expects to assume the leadership position wherever she is, and the peoplearound her expect her to as well. Whichis probably why I’m actually rooting way more for the gig to go to Octavia.

Octavia has been a problem character for me since the start of thisvengeance arc in the middle of Season 3; we’ve been watching her channel allher grief and anger into an endless succession of destructive behaviors, withno real clear sense of whether the narrative intended us to be on her side ornot. I think some of that is gettingclarified this season (the Pike flashbacks as she held a gun on Ilian may havebeen clumsy on an emotional level, but they did serve to definitively remindthe audience, and Octavia, that Bellamydid not kill Lincoln, which clears upthe question of whether we were supposed to take her side when she accused himof that), and we know she gets some big crazy plot twist because everyone fromthe show in every interview who gets asked “who has the coolest arc thisseason?” says “Octavia.” So like, thinkfor a second about the idea of Octavia having to do something she’s never donebefore in her whole life and actually assume a role of leadership over otherpeople. No big brother/little sister dynamicto hide behind. Octavia has often beendefined, both in the narrative and I think to herself, in the context of otherpeople. She was the girl who lived underthe floorboards, then she was Bellamy’s sister, then she was Lincoln’sgirlfriend, then she was Indra’s second, then she was grieving Lincoln, thenshe was Kane’s bodyguard. So I like theidea of Octavia having to ask herself some hard questions about who Octavia is,on her own. After four seasons of seeingher sit in judgment of Clarke and Bellamy and others’ decisions, sometimescriticizing the outcome without really having a complete understanding of whatwent into it and how many competing forces were at play, I like the idea ofOctavia being the one who has to make the hard choices. It’s the missing piece to her finally beingable to really understand her brother. She also needs something constructive to do with her passion and energy andemotion and grief besides, you know, stabbing people. Imagine Octavia having to persuade, Octavia having to learn how toget people to actually follow her, Octavia having to take diplomacy lessonsfrom Dad!Kane (”you can’t just kill everyone who disagrees with you,” as CallieCartwig once told him), Octavia having to collaborate. Octavia and Bellamy working together to bring everyone to the table – Azgeda andTrikru and Skaikru – to figure out who this new society is and who they want tobe. Octavia getting to honor Lincoln byhelping to establish the kind of peace he hoped for (remember him in 301telling her about how Kane and Abby had the right idea and were trying to builda community where those divisions didn’t exist anymore), not by stepping into aspecific and clearly-defined role that’s held as sacred by a culture that doesn’tbelong to her, but by putting all her grudges and hostility aside to fight fora new way. And if that involves hergetting Nightblood so she can take the Flame and commune with Becca about specificthings that Becca knows, that’s different enough from “Octavia becomingCommander” that I think I could be totally down with it.

#Anonymous#From the Inbox#metas and headcanons#the 100 meta#the 100#clarke griffin#octavia blake#becca pramheda#commander lexa#commanders#the 100 season 4

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Delivery & A Movie Celebrate Black History And Culture In NYC added to Google Docs

Delivery & A Movie Celebrate Black History And Culture In NYC