#the earth has been uninhabitable for centuries

Text

There are a couple of things about Aziraphale that I think we, as a fandom*, focus too much on and get it slightly wrong in the process.

*= I am talking about the regular Good Omens fandom and Aziraphale fans here, not including the Aziraphale haters, who can skip this post because they wouldn't care or understand anyway.

First of all, yes, Heaven is an abusive work environment. The angels in charge are bullies, while Aziraphale is a sweet little cinnamon roll. Absolutely no question there.

And yes, Aziraphale is scared that his relationship with Crowley is discovered. Again, elementary, my dear Watson.

But he is always much more scared for Crowley, if Hell would ever find out, than he is for himself. He's terrified that something could happen to Crowley (see Edinburgh leading to the whole Holy Water blow-up). He knows, or can at least imagine, what Hell would do to Crowley, and he wouldn't even be able to get to him, much less help. Maybe not even immediately realise when it happened.

But he himself has been lying to God and Heaven from the very beginning (what he says to the Starmaker in Before the Beginning, about not wanting to get him into trouble, proves that he was always wary and filtering his words carefully). He lied directly to God's face right after Eden. And he always got away with it. We see him getting more and more comfortable with it during the millennia.

Yes, he sometimes still gets nervous when he faces a surprise or a new threat and he has to think on his feet, but he does it. Every time.

But we are tending to treat him like a little scaredy cat that lives in constant terror of Heaven, and I don't think that's the case. In later centuries he knows that he can run circles around the archangels when it comes to Earth, because he is the expert and they are absolutely clueless. Earth is his domain, where he holds all the power. (Or at least, all the knowledge, which some philosophies argue is the same.)

And while he is much more naive than his book counterpart in his belief that Heaven is good and Hell is bad, this also isn't as extreme as we sometimes make it out to be.

He knows what Sandalphon did during Sodom and Gomorrah. He knows what God did to people with the Flood. He knows what God did to Job. He was told - or is telling himself - it was just, and even that he already started to doubt. With Job, he knew it wasn't.

He hasn't, as I just read in an otherwise rather similar post, been drilled to believe that the Apocalypse is the end goal. He was taught it was inevitable. That it was Hell's end goal. That Heaven winning (what Hell would start) was inevitable - and just! And that was what made him believe that when he finds a way to make it not inevitable, the other angels would have no choice other than to support him, that God herself would want to support him, because they're supposed to be the good guys. And when he learns that that is not the case, he still immediately goes on to do it by himself. He isn't unsure, after he stepped into the circle, when the military angel tries to draft him for the war, or pondering what he should do. He spends the whole time trying to figure out how to get back to earth, and when he discovers a possibility, he doesn't even hesitate for a second.** And when he leaves Earth to take the job as the Supreme Archangel, he does so because he believes he can change it into what he still thinks it should be, knowing full well what it is.

Now I, personally, am not with the nihilistic / resigned Gen-Z crowd who seem to think that trying to change things is stupid, because only violent revolutions and total destruction of existing structures could achieve any real change, and that Aziraphale somehow has to apologise for believing otherwise and trying. (?) Maybe that's because as an elder millennial I can rest in the knowledge that I won't be around when our planet becomes uninhabitable, or maybe it's because I was actually alive to witness the collapse of the USSR, which, incidentally, was pretty much the same time at which Good Omens was written.

Which brings me to my next point.

I don't want to take anything away from fans who relate to Aziraphale because they themselves have experienced religious trauma. He is certainly a powerful metaphor for it. But Aziraphale the character does not experience religous trauma, because he doesn't experience religion.

The existence of God, of Angels, the creation of the world in 7 days, those are not beliefs for Aziraphale, they are simple facts. He has actually witnessed them, he has worked on some of them himself, he is an angel himself. He knows how everything works (or where it doesn't). He isn't a human who has free will and is supposed to have faith, who gets to interpret and re-interpret and guess at how it all works while forming self-important little groups around it and lay it down as law for anyone who wants to join (or remain). It's simply his job. (Well, job for life, and the whole reason for his own existence, but still his job.) God is literally just his boss. A largely absentee boss, but still his boss. He actually even talked to Her at least once.

For angels and demons, Heaven and Hell are not religions, but simple work environments (with certain accompanying ideologies). In the book, being 30 years older than the show, the two sides are quite open references to the two sides in the cold war, and Crowley and Aziraphale are likened to spies in the field. (Pretty much the only thing remaining from that in the show are the St. James Park Bench scenes.)

And I would like people to start remembering that. Aziraphale is not a traumatized little kid who tries to escape a religious cult. He is a Secret Agent who is walking the very dangerous line of collaborating with an Enemy Secret Agent, undermining both their nations and their ideologies at the same time. (Think John Le Carré characters rather than James Bond.) He is afraid of dangers that are very real, but that he has faced and flaunted during his whole career. He knows what he's doing. Which also means he knows what's at stake. And yeah, that is terrifying, naturally. (Again, John Le Carré writes those kind of spy stories brilliantly.)

But Aziraphale is the fucking Angel of the Eastern Gate. He was issued a flaming sword that he gave away against his orders because he believed it to be the right thing to do. Who befriended his demon enemy because he liked him, more than he ever liked anyone from his own side. And who is basically using the seven deadly sins as a to-do-list. That he has a sweet little face that lights up like a christmas tree when he's happy and in love, or that he still believes in the basic goodness and justice of the world, or that he tries to be kind or at least polite whenever he can, does not take anything away from that.

And for the 2nd Coming in season 3 he will be what Crowley was for Armageddon in season 1: The Inside Man.

**= Here I would also like to add that again, as much as I was disappointed for not getting the tv evangelist scene in the show, book!Aziraphale is still much less naive and more cynical about Heaven's goodness - even while show!Aziraphale's defiance of Heaven is much more outspoken and obvious, I can't actually imagine him delivering the whole "if that's your idea of a morally acceptable time" speech.

#good omens#aziraphale#az fell#azira fell#good omens aziraphale#aziraphale good omens#good omens book#good omens meta#good omens analysis#good omens thoughts#good omens season 3#good omens season 1#good omens season 2#good omens 2#good omens 3#good omens show#good omens tv show

242 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is it like on your home planet? On Earth we have two continents called the Artic and Antartica at each end of the hemisphere, which both remain at uninhabitable cold temperatures year round, no matter what season each side of the Earth is in. Due to your family’s naming scheme (well, apart from your son’s name) being related to the cold, I was wondering if your planet had a similar disposition to those continents?

Also, why is your son named Kuriza? As mentioned his name doesn’t seem to fit the family theme-that is unless the name has a specific meaning in your language?

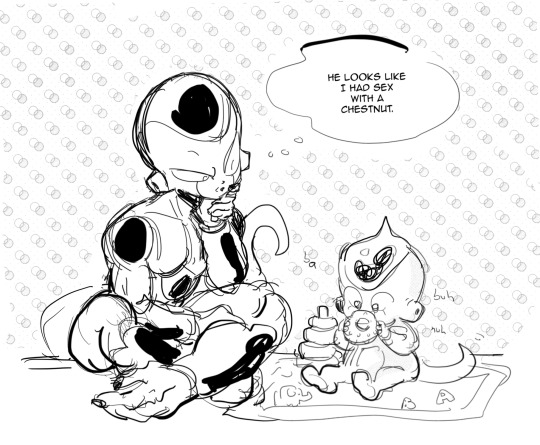

Planet Arcos was a barren, frigid place. Surviving there meant becoming as cold as the planet itself, or so they say… I’ve never actually been; the capitol was abandoned centuries ago. My father used to go back and forth with himself, debating whether to destroy it outright.

And on the topic of Kuriza…

His given name was meant to be Algid Pola Cold, but after he was born my men started calling him “Kuriza” on account for the little point on the top of his head, and it just sort of stuck. Algid “Kuriza” Cold it was, and shall forever be.

#img response#text response#Kuriza#my darling chestnut boy#Thank god for eggs#I would not have liked to feel that thing scraping along my insides#thank you very much

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prairies are ecosystems that evolved with people, that came to meet their own fullness and their own agency in relationship to people. Plains peoples would set some of the fires themselves, for when the litter was cleared and the energy stored in last season’s grasses was released back into the soil, when the encroaching trees withered, the land restored itself and the grazers came back to feed on the bright sustenance that returned.

Grassland ecosystems in the continental United States have not known any significant stretch of time without the active participation of human beings. People are an integral part of the life cycle of prairies, still. But because we have, by and large, now stripped the land of the conditions that once sustained grassland ecosystems—bison, fire, human understanding of the interplay of these forces on the landscape—the way we interact with prairies determines not only their condition, but often their very existence. Only where prairies are carefully and actively managed by people do they thrive in all of their biodiversity.

The fact that humans have been a part of prairies since there has been such a thing on this continent calls into question a widespread assumption about the word wilderness.

WILDERNESS: (1a) a tract or region uncultivated and uninhabited by human beings; (1b) an area essentially undisturbed by human activity together with its naturally developed life community; (2) an empty or pathless area or region; (3) a part of a garden devoted to wild growth.

Standing atop this dune, I’m wondering whether this word describes any of what I am seeing. The world over, humans have been participating in complex, cohesive ecosystems for millennia, their activities often serving peak biodiversity rather than working against it.

How our philosophical and spiritual separation from those systems has come about is deeply complex in its own right. But a key part of that separation can be glimpsed in the recent etymological evolution of this word. Wilderness in nineteenth-century American discourse—a concept with roots in both scripture and the Enlightenment—was something to be conquered and controlled. Manifest Destiny sought the taming of the wild.

After the pursuit of the American frontier came to a close in the late 1800s, the influence of Romanticism and Transcendentalism helped to shift the American attitude toward wilderness from one of conquering to one of preserving, a shift that is apparent, three-quarters of a century later, in the language of the 1964 Wilderness Act: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

In both of these definitions “wilderness” designates humans as apart. In its contemporary usage, the concept of wilderness spawns distance from the very thing it attempts to affirm.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yet another another another excerpt from I Survived Kirk, the forthcoming fanfic autobiography of a bitter redshirt on Kirk's Enterprise

I may be a former member of Starfleet, but that doesn’t mean I agree with every choice they make or have made in the past. Starfleet is STILL paying for the mistakes they made in early missions, and likely will for centuries to come.

I hate propaganda. I hate whitewashing history. Don’t teach lies so that your children won’t have to learn that you’re flawed and made stupid mistakes, otherwise they’ll make the same damn ones. Obviously, I wasn’t there but if you do the research you can verify all this for yourself.

We’re taught that Jonathan Archer heroically saved the planet from the Xindi in 2153. We’re told he was instrumental in ending the Romulan war. He was a hero, who paved the way for the United Federation of Planets. He’s a legend.

But here’s what they don’t tell you: Jonathan Archer wasn’t even the first choice to command Enterprise NX-01. That was a guy named AG Robinson, who was disqualified after an unauthorized test flight. Something HUGE that is ALWAYS glossed over, is the fact that it was Jonathan Archer’s father Henry Archer who designed the Enterprise’s warp five engine. Nepotism in Starfleet? The same nepotism that pervades today, if anyone looks up George Kirk Sr, best friend of Captain Robert April and whose troublemaker of a son ended up succeeding April (and Pike) as captain of this generation’s USS Enterprise.

And it’s not like Archer had any starship experience. That’s why you never hear about his time on any ships before Enterprise. There wasn’t any. “Flight School” (that’s what came before Starfleet Academy) – test pilot of the NX-project – Captain of the Enterprise. They just declared him a captain and sent him out in charge of 80-odd people.

It was Jonathan Archer that invited the infamous Xindi attack which cost 7 million lives and destroyed Florida by telling every alien they encountered for two years how to find Earth. He literally sent starcharts so that even the ones that couldn’t understand our language knew where we came from.

And Starfleet just let him. In fact, they didn’t even send Enterprise out with a proper mission statement except to “go where no man has gone before”. You’d think a mission of such import (they only spent 30 years developing the warp five engine and ship design, which ended up the blueprint for everything after upto and including our current generation of starships), they’d have mapped out the mission in intricate detail, which stars to visit, which planets to chart, which aliens to contact and what to say/not say. But no, Johnny boy just floated around aimlessly, getting his ship into trouble and making a professional victim of himself. He was “officially” kidnapped 28 times between April 26, 2151 and April 24, 2153. Once he caused an intergalactic incident because he let his dog piss up some sacred tree. Once he almost let member of his crew die in the extreme heat of a planet and never thought to beam down cooling units. Most infamously, he refused medical help to a species called the Valakians because he decided it was their destiny to die out. What a nice man.

So anyway, after two years of obliviously causing intergalactic incidents (including with the Romulans, more on that later), a race called the Xindi sent a weapon to Earth and killed 7 million people. They then build and launch a second, much larger weapon to destroy the entire planet (because just rendering it uninhabitable is too mainstream, or something. I guess these guys weren’t the sharpest knives in the drawer either). Archer somehow sneaks onto the weapon and destroys it, and somehow survives.

Now, why did the Xindi attack? Something to do with ancient gods but they’re very sorry now can we join the Federation blah blah. How did the Xindi attack? Earth was clearly marked in maps the Enterprise had been transmitting to everyone they encountered. Why advertise your location to a galaxy full of clearly hostile species without adequate defences?

And yes, Archer’s why the Klingons and Romulans hate us, too. Cheers mate, you’re a legend.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

capital worlds of the solar federation

Earth:

The ancestral homeworld of humanity is now becoming slowly overshadowed by human colonies on other worlds, the biggest of these being Sirius. Often called the new earth, most of earths wildlife and nature was transported to sirius as earths collapsing ecosystem threatens to cause a mass extinction of animal life.

Despite this, earth is still home to 150 billion humans and other species and holds important cultural sites. From the most ancient of ruins to the first megacity constructed in japan.

Most life on the planet is concentrated in these megacitys, with anything outside them considered uninhabitable. The abandoned ancient cities here have been overtaken by nature, and becoming home to gangs of looters scavenging anything left behind.

Earth is considered a very expensive world to life on, despite the standard of living for 99% of the population being far below that of human colonies across space.

The Richest of the population live in skyscrapers above the clouds, or floating cities in orbit. The air and rain in many of the megacitys is somewhat toxic, to be largely indoors. Parks are build to simulate the outside, and a artificial sky at least gives the illusion of a clear sky.

80% of wildlife has gone extinct, with the remaining few being transported to sirius.

Scientists have luckily managed to bring most animal species back from extinction trough cloning, however some are sadly lost forever.

However in recent years, thanks to the help of therian terraforming technology, a massive ecological restoration project has begun thats estimated to have restored earth by the year of 2850. So many hold hope that even in her rough condition, the homeworld of humankind can be saved.

Due to climate change, the average temperature of earth is around 19°c, wich caused mass flooding and eventually ecological disaster. The planet has 24 hour days with 365 days in a year.

Silakare:

The new homeworld of the Therians, silakare is a beautiful world of lush purple plant lifes and shallow warm oceans.

The world's surface is uninhabited, as the avian therians life in floating cities kilometres above the ground.

Silakut was the original homeworld, wich was destroyed by a supernova that was scientifically impossible and is still not understood. Silakare was once a dead moon with a barley existing atmosphere, but thanks to therians advanced technology they managed to turn it into the paradise it is today.

Animals from their old homeworld were genetically modified to life on the terraformed world, wich was transformed to resemble their old home as closely as possible.

Since then, the floating cities of silakare have become the official capital of the solar federation, with the largest of the cities being Orlos. Wich boasts a population of 240 billion and has a reputation for being a melting pot of cultures from all member species of the federation.

Silakare is relatively cold despite its tropical appearance, with temperatures around 9 degrees most of the year. A day has 32 hours with 409 days in a year.

Zadrik:

Homeworld of the Ilgorans. Its the smallest of the capital worlds, around the size of mars.

Its surface is covered in the ilgorans iconic city trees, enormous tree like plants specalized to grow into massive towers and house thousands of ilgorans.

In many ways zadrik is a lot like earth before the ecological collapse of the 25th century, with lush forests of red plants and the chirping of the slugbirds in their canopies.

Like the ilgorans, most life on zadrik is comparable to molluscoids. Most have a hard shell of sorts and posses a soft inside with hermaphroditic reproductive organs.

The planet itself is actually a moon orbiting the gas giant of Zuldrun, wich is often seen as the shell of a deity in ilgoran religions.

Zadrik is moderately warmer than earth at 31 degrees, with 19 hour days and 290 days in a year.

Thaul:

Home of the Vardee, and the biggest known habitable world in explored space.

This size is likely due to not being formed naturally, instead being artificially constructed 300 million years ago. The core is theorized to have been a smaller moon of planet that was artificially turned into a planetary core. Massive towers hundred of kilometers wide run from the surface to the core, likely as some sort of maintenance system.

Underneath the surface are tunnels that run underneath entire continents, and go even deeper into unexplored areas of the planet.

The vardee and many other animals of thaul likely descend from pets that these ancient “architects” kept.

This is evidenced my murals that depict these architects and being that looks strikingly similar to a lot of lifeforms inhabiting thauls oceans and continents. The architects themselves seem to have been somewhat humanoid, or at least bipedal. Sadly most murals are extremely eroded and damaged, making it hard to make out details.

Vardee build their cities in the massive towers that run to the core, wich are large enough for each tower to act as its own nation.

Most of the towers have only the first few hundred floors explored, many of wich have been flooded or house entire ecosystems of subterranean lifeforms. The deepest any explores got was floor 450 In the tower city of zulkran which is also the planetary capital. The bottom most layers were filled with overgrown ruins of buildings, home to entirely unknown blind animals. After DNA testing, it was revealed that these were actually the closest living relatives of the Vardee, with a 97% match.

The vardee rarely travel outside of the massive tower cities, meaning large portions of thaul are mostly uninhabited and wilderness. They take great care and pride in this wilderness, it even being a afterlife in some believes.

The average temperature of thaul is 16°c. Days are 30 hours long and a year lasting for 490 days.

Lirthak:

Home to the Olorans, and the most unique of the planetary capitals.

The planet itself looks like a barren rock from the surface, however underneath is a expansive cave system large enough to house forests, oceans and steppes of bioluminescent grass.

Olorans evolved in these steppes as lirthaks equivalent to herd animals, eating the blue glowing grass with their prehensile and dexterous tongues. This combined with having to find strategies to outsmart predators aswell as remembering the layouts of the cave system lead to the olorans extreme intelligence.

Over time they developed an advanced civilization with technological wonders rivalling the therians. With the cities becoming overcrowded however, they sought to see whats outside of the cave systems. They were aware that there was something outside of it, but this was only realy discover relatively recently thanks to modern technology. Problem was, there were only a few dozen exits out of the cave systems, and these lead to the uninhabitable surface of their homeworld.

So the top scientists and engineers got together to build massive domes on the surface, wich were then artificially filled with ecosystems and cities.

After this, oloran civilization was never the same. Soon after they constructed their first off world colonies, and travelled outside of their home system.

With the megacorporations that rule oloran civilization needing space for their manufacturing and housing the population of the overcrowded cities, two rings were build using material from lirthaks 2 moons. The olorans had no sentimental attachment to the moons due to not even knowing about their existence only decades before, and being as pragmatic as they are simply saw them as unused construction material orbiting their homeworld.

These rings now house everything from entire sectors of industry, housing, city sized malls, megacomputers, farming sectors and even artificially created beach resorts for tourists.

Lirthak and its two rings now have the largest population of any planet in the galaxy, with a grand total of 990 billion people calling it home. Its predicted to reach 1 trillion inhabitants by 2790.

The cave systems of lirthak are very cold due to not having sunlight, with average temperatures around -30°c. The rings are kept at around 20°c. A Lirthak day is 15 hours with 270 days in a year.

#scifiart#sci fi writing#sci fi planets#planets#space#solar system#planet art#sci fi planet#future planet#map art#my art#solar archives

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Omentober Day 10 - Beelzebub

Prompt by @disaster-dog

Beelzebub remembers the longing they felt. What was meant to be a punishment for the demon Crawly ended up being a journey of self-discovery for them both.

Crawly was struggling to find their way in Hell. The stench never really left and it felt like the place was always crawling with something. They’d slowly begun carving a place out for themselves in hell.

They’d gotten the hang of playing practical jokes on the demons and were slowly getting better at tempting the humans but the most fun was seeing how much chaos they could unleash on Hell without being caught.

Crawly’s most recent exploits included making half of Hell uninhabitable as he created a huge plume of hellfire and ensured it had enough fuel to burn for centuries. The demons were welcome to walk through it but the smoke and the smell was too much for anyone to bear for an extended period of Beelzebub placed a flat ban on the area.

Now, however, Crawly was summoned to face Lord Beelzebub themselves and part of them was nervous. Sure, nothing could be worse than falling but Crawly also wasn’t trying to test that theory.

“Crawly, the little practical joker of the underworld. I’ve been expecting you,” Beelzebub buzzed. They were perched on their throne staring down at the demon.

Crawly shifted somewhat awkwardly and looked up at the superior in front of them. They were hesitant to say a word knowing they already had enough reason to be in hot water.

“We have a unique job for you. We have been looking for a reason to get you out of our hair and the perfect position just opened up.” A ghoulish grin began to spread across the Lord’s features and they moved to lean forward, their hands resting on their knees.

“So like, a promotion?” Crawly quizzed, “I was expecting some kind of punishment but if you think I need a promotion I won’t complain.”

“We need someone on the ground to make sure the angels don’t influence the humans too much. We already have a couple of demons out doing some tempting but after your efforts in Eden, I think you’re more than qualified to be our representative on Earth. Permanently.” Beezlebub muttered darkly, standing up to move closer to Crawly. “That angel in your past reports, Aziraphale, was it? Well, a few other demons have reported seeing him around so we’re worried Heaven might have the same idea. You need to keep an eye on that one.”

Crawly simply nodded, feeling more intimidated with each step Beelzebub moved closer, “I’d be more than happy to. Someone has to keep the humans in check.”

“That doesn’t mean you get free reign, Crawly. I have eyes everywhere. We will watch your every move,” Beelzebub threatened, grabbing Crawly’s collar to limit the distance between them, “You will not fuck this up.”

Crawly got shoved aside and Beelzebub sat back down on their throne. The Dukes of Hell began to file into the room, ready to see Crawly off. All the demons were ready to be rid of them but Beelzebub had a sense that they were too valuable to lose just yet.

Beelzebub wasn’t kidding when they said they had eyes everywhere. For a long time, it felt like there were more demons on earth than humans, all watching to see Crawly’s next temptation or to see what kind of big tragedy they’d cause.

Whenever Crawly was with Aziraphale, they felt chills run down their spine and they swore they could always hear the buzzing of flies. It always made the demon feel paranoid but they should’ve expected Beelzebub to keep their word.

And they did. Beelzebub always paid particular attention to Crawly, or Crowley as he’d come to be known. They’d watched as he kept crossing paths with Aziraphale and they'd always have to check to make sure there were no demons fraternizing with Heaven. That wasn’t the only reason, though.

Beelzebub was intoxicated by the thought of having someone that close, especially someone who was meant to be an enemy. Occasionally, they would follow the two around just to hear about whatever they were talking about. Ducks, dinner, driving. They wanted to see Crowley and Aziraphale admit their feelings for each other. If they could be together then it would give Beelzebub some hope for their own life.

Beelzebub never thought they’d find someone like that for them. It’s the kind of thing that was drilled into the Fallen. They were unlovable, worthless and not good for anything but temptations and evil.

---

The first person who had ever told them otherwise was Gabriel in their few unlikely meetings. It was like he saw right through them, saw right through their dark exterior to the heart of someone who just wanted to feel like they belonged again. Despite being on opposite sides, Gabriel could understand how it felt to have thousands of people at your beck and call. Gabriel understood what it was like to have to be in control of everything but felt so out of control.

Beelzebub would constantly arrange opportunities to ‘bump into’ Gabriel after their first meeting. They wanted to feel those butterflies in their stomach again and they wanted to feel like they meant something to someone. The demons in hell only listened to them because they had to. Gabriel listened because he wanted to.

Beelzebub quickly realised that waiting for Aziraphale and Crowley to set an example wasn’t going to work. They were both too stubborn and Aziraphale still hadn’t learnt to listen to Crowley. Beelzebub never had that problem with Gabriel, though. They instantly fell into a whimsical dance and the Lord never wanted it to end.

When they both agreed to leave their slides behind to devote all their time to each other, Beelzebub finally felt whole. The longing they’d felt in Hell was finally filled and they found paradise among the stars.

#good omentober#crowley#aziracrow#good omens season 2#good omens 2#good omens#beelzebub#beelzebriel#fallen angel#ao3 fanfic#fanfiction#crawly

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

This story originally appeared in Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems, and is part of the Climate Desk collaboration. It was published in collaboration with Earth Island Journal.

The floatplane bobs at the dock, its wing tips leaking fuel. I try not to take that as a sign that my trip to Chirikof Island is ill-fated. Bad weather, rough seas, geographical isolation—visiting Chirikof is forever an iffy adventure.

A remote island in the Gulf of Alaska, Chirikof is about the size of two Manhattans. It lies roughly 130 kilometers southwest of Kodiak Island, where I am waiting in the largest town, technically a city, named Kodiak. The city is a hub for fishing and hunting, and for tourists who’ve come to see one of the world’s largest land carnivores, the omnivorous brown bears that roam the archipelago. Chirikof has no bears or people, though; it has cattle.

At last count, over 2,000 cows and bulls roam Chirikof, one of many islands within a US wildlife refuge. Depending on whom you ask, the cattle are everything from unwelcome invasive megafauna to rightful heirs of a place this domesticated species has inhabited for 200 years, perhaps more. Whether they stay or go probably comes down to human emotions, not evidence.

Russians brought cattle to Chirikof and other islands in the Kodiak Archipelago to establish an agricultural colony, leaving cows and bulls behind when they sold Alaska to the United States in 1867. But the progenitor of cattle ranching in the archipelago is Jack McCord, an Iowa farm boy and consummate salesman who struck gold in Alaska and landed on Kodiak in the 1920s. He heard about feral cattle grazing Chirikof and other islands, and sensed an opportunity. But once he’d bought the Chirikof herd from a company that held rights to it, he got wind that the federal government was going to declare the cattle wild and assume control of them. McCord went into overdrive.

In 1927, he successfully lobbied the US Congress—with help from politicians in the American West—to create legislation that enshrined the right of privately owned livestock to graze public lands. What McCord set in motion reverberates in US cattle country today, where conflicts over land use have led to armed standoffs and death.

McCord introduced new bulls to balance the herd and inject fresh genes into the pool, but he soon lost control of his cattle. By early 1939, he still had 1,500 feral cattle—too many for him to handle and far too many bulls. Stormy, unpredictable weather deterred most of the hunters McCord turned to for help thinning the herd, though he eventually wrangled five men foolhardy enough to bet against the weather gods. They lost. The expedition failed, precipitated one of McCord’s divorces, and almost killed him. In 1950, he gave up. But his story played out on Chirikof over and over for the next half-century, with various actors making similarly irrational decisions, caught up in the delusion that the frontier would make them rich.

By 1980, the government had created the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge (Alaska Maritime for short), a federally protected area roughly the size of New Jersey, and charged the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) with managing it. This meant preserving the natural habitat and dealing with the introduced and invasive species. Foxes? Practically annihilated. Bunnies? Gone. But when it came to cattle?

Alaskans became emotional. “Let’s leave one island in Alaska for the cattle,” Governor Frank Murkowski said in 2003. Thirteen years later, at the behest of his daughter, Alaska’s senior senator, Lisa Murkowski, the US Congress directed the USFWS to leave the cattle alone.

So I’d been wondering: What are those cattle up to on Chirikof?

On the surface, Alaska as a whole appears an odd choice for cattle: mountainous, snowy, far from lucrative markets. But we’re here in June, summer solstice 2022, at “peak green,” when the archipelago oozes a lushness I associate with coastal British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. The islands rest closer to the gentle climate of those coasts than to the northern outposts they skirt. So, in the aspirational culture that Alaska has always embraced, why not cattle?

“Why not cattle” is perhaps the mantra of every rancher everywhere, to the detriment of native plants and animals. But Chirikof, in some ways, was more rational rangeland than where many of McCord’s ranching comrades grazed their herds—on Kodiak Island, where cattle provided the gift of brisket to the Kodiak brown bear. Ranchers battled the bears for decades in a one-sided war. From 1953 to 1963, they killed about 200 bears, often from the air with rifles fixed to the top of a plane, sometimes shooting bears far from ranches in areas where cattle roamed unfenced.

Bears and cattle cannot coexist. It was either protect bears or lose them, and on Kodiak, bear advocates pushed hard. Cattle are, in part, the reason the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge exists. Big, charismatic bears outshone the cows and bulls; bear protection prevailed. Likewise, one of the reasons the Alaska Maritime exists—sweeping from the Inside Passage to the Aleutian chain and on up to the islands in the Chukchi Sea—is to protect seabirds and other migratory birds. A cattle-free Chirikof, with its generally flat topography and lack of predators, would offer more quality habitat for burrow-nesting tufted puffins, storm petrels, and other seabirds. And yet, on Chirikof, and a few other islands, cows apparently outshine birds.

The remoteness, physically good for birds, works against them, too: Most people can picture a Ferdinand the Bull frolicking through the cotton grass, but not birds building nests. Chirikof is so far from other islands in the archipelago that it’s usually included as an inset on paper maps. A sample sentence for those learning the Alutiiq language states the obvious: Ukamuk (Chirikof) yaqsigtuq (is far from here). At least one Chirikof rancher recommended the island as a penal colony for juvenile delinquents. To get to Chirikof from Kodiak, you need a ship or a floatplane carrying extra fuel for the four-hour round trip. It’s a wonder anyone thought grazing cattle on pasture at the outer edge of a floatplane’s fuel supply was a good idea.

Patrick Saltonstall, a cheerful, fit 57-year-old with a head of tousled gray curls, is an archaeologist with the Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak. He’s accompanying photographer Shanna Baker and me to Chirikof—but he’s left us on the dock while he checks in at the veterinarian’s where he has taken his sick dog, a lab named Brewster.

The owners of the floatplane, Jo Murphy and her husband, pilot Rolan Ruoss, are debating next steps, using buckets to catch the fuel seeping from both wing tips. Weather is the variable I had feared; in the North it’s a capricious god, swinging from affable to irascible for reasons unpredictable and unknowable. But the weather is perfect this morning. Now, I’m fearing O-rings.

Our 8 am departure ticks by. Baker and I grab empty red plastic jerrycans from a pickup truck and haul them to the dock. The crew empties the fuel from the buckets into the red jugs. This will take a while.

A fuel leak, plus a sick dog: Are these omens? But such things are emotional and irrational. I channel my inner engineer: Failing O-rings are a common problem, and we’re not in the air, so it’s all good.

Saltonstall returns, minus his usual smile: Brewster has died.

Dammit.

He sighs, shakes his head, and mumbles his bewilderment and sadness. Brewster’s death apparently mystified the vet, too. Baker and I murmur our condolences. We wait in silence awhile, gazing at distant snowy peaks and the occasional seal peeking its head above water. Eventually, we distract Saltonstall by getting him talking about Chirikof.

Cattle alone on an island can ruin it, he says. They’re “pretty much hell on archaeological sites,” grazing vegetation down to nubs, digging into the dirt with their hooves, and, as creatures of habit, stomping along familiar routes, fissuring shorelines so that the earth falls away into the sea. Saltonstall falls silent. Brewster is foremost on his mind. He eventually wanders over to see what’s up with the plane.

I lie on a picnic table in the sun, double-check my pack, think about birds. There is no baseline data for Chirikof prior to the introduction of cattle and foxes. But based on the reality of other islands in the refuge, it has a mix of good bird habitats. Catherine West, an archaeologist at Boston University in Massachusetts, studies Chirikof’s animal life from before the introduction of cows and foxes; she has been telling me that the island was likely once habitat for far more birds than we see today: murres, auklets, puffins, kittiwakes and other gulls, along with ducks and geese.

I flip through my notes to what I scrawled while walking a Kodiak Island trail through Sitka spruce with retired wildlife biologist Larry Van Daele. Van Daele worked for the State of Alaska for 34 years, and once retired, sat for five years on the Alaska Board of Game, which gave him plenty of time to sit through raucous town hall meetings pitting Kodiak locals against USFWS officials. Culling ungulates—reindeer and cattle—from islands in the refuge has never gone down well with locals. But change is possible. Van Daele also witnessed the massive cultural shift regarding the bear—from “If it’s brown, it’s down” to it being an economic icon of the island. Now, ursine primacy is on display on the cover of the official visitor guide for the archipelago: a photo of a mother bear, her feet planted in a muddy riverbank, water droplets clinging to her fur, fish blood smearing her nose.

But Chirikof, remember, is different. No bears. Van Daele visited several times for assessments before the refuge eradicated foxes. His first trip, in 1999, followed a long, cold winter. His aerial census counted 600 to 800 live cattle and 200 to 250 dead, their hair and hide in place and less than 30 percent of them scavenged. “The foxes were really looking fat,” he told me, adding that some foxes were living inside the carcasses. The cattle had likely died of starvation. Without predators, they rise and fall with good winters and bad.

The shape of the island summarizes the controversy, Van Daele likes to say—a T-bone steak to ranchers and a teardrop to bird biologists and Indigenous people who once claimed the island. In 2013, when refuge officials began soliciting public input over what to do with feral animals in the Alaska Maritime, locals reacted negatively during the three-year process. They resentfully recalled animal culls elsewhere and argued to preserve the genetic heritage of the Chirikof cattle. Van Daele, who has been described as “pro-cow,” seems to me, more than anything, resistant to top-down edicts. As a wildlife biologist, he sees the cattle as probably invasive and acknowledges that living free as a cow is costly. An unmanaged herd has too many bulls. Trappers on Chirikof have witnessed up to a dozen bulls at a time pursuing and mounting cows, causing injury, exhaustion, and death, especially to heifers. It’s not unreasonable to imagine a 1,000-kilogram bull crushing a heifer weighing less than half that.

But, as an Alaskan and a former member of the state’s Board of Game, Van Daele chafes at the federal government’s control. Senator Murkowski, after all, was following the lead of her constituents, at least the most vocal of them, when she pushed to leave the cattle free to roam. Once Congress acted, Van Daele told me, “why not find the money, spend the money, and manage the herd in a way that allows them to continue to be a unique variety, whatever it is?” “Whatever it is” turns out to be not much at all.

Finally, Ruoss beckons us to the plane, a de Havilland Canada Beaver, a heroically hard-working animal, well adapted for wandering the bush of a remote coast. He has solved the leaking problem by carrying extra fuel onboard in jerrycans, leaving the wing tips empty. At 12:36 pm, we take off for Chirikof.

Imagine Fred Rogers as a bush pilot in Alaska. That’s Ruoss: reassuring, unflappable, and keen to share his archipelago neighborhood. By the time we’re angling up off the water, my angst—over portents of dead dog and dripping fuel—has evaporated.

A transplant from Seattle, Washington, Ruoss was a herring spotter as a young pilot in 1979. Today, he mostly transports hunters, bear-viewers, and scientists conducting fieldwork. He takes goat hunters to remote clifftops, for example, sussing out the terrain and counting to around seven as he flies over a lake at 100 miles per hour (160 kilometers per hour) to determine if the watery landing strip is long enough for the Beaver.

From above, our world is equal parts land and water. We fly over carpets of lupine and pushki (cow parsnip), and, on Sitkinak Island, only 15 kilometers south of Kodiak Island, a cattle herd managed by a private company with a grazing lease. Ruoss and Saltonstall point out landmarks: Refuge Rock, where Alutiiq people once waited out raids by neighboring tribes but couldn’t repel an attack from Russian cannons; a 4,500-year-old archaeology site with long slate bayonets; kilns where Russians baked bricks for export to California; an estuary where a tsunami destroyed a cannery; the village of Russian Harbor, abandoned in the 1930s. “People were [living] in every bay” in the archipelago, Ruoss says. He pulls a book about local plant life from under his seat and flips through it before handing it over the seat to me.

Today, the only people we see are in boats, fishing for Dungeness crab and salmon. We fly over Tugidak Island, where Ruoss and Murphy have a cabin. The next landmass will be Chirikof. We have another 25 minutes to go, with only whitecaps below.

For thousands of years, the Alutiiq routinely navigated this rough sea around their home on Chirikof, where they wove beach rye and collected amber and hunted sea lions, paddling qayat—kayaks. Fog was a hazard; it descends rapidly here, like a ghostly footstep. When Alutiiq paddlers set off from Chirikof, they would tie a bull kelp rope to shore as a guide back to safety if mist suddenly blocked their vision.

As we angle toward Chirikof, sure enough, a mist begins to form. But like the leaking fuel or Brewster’s death, it foreshadows nothing. Below us, as the haze dissipates, the island gleams green, a swath of velveteen shaped, to my mind, like nothing more symbolic than the webbed foot of a goose. A bunch of spooked cows gallop before us as we descend over the northeast side. Ruoss lands on a lake plenty long for a taxiing Beaver.

We toss out our gear and he’s off. We’re the only humans on what appears to be a storybook island—until you kick up fecal dust from a dry cow pie, and then more, and more, and you find yourself stumbling over bovid femurs, ribs, and skulls. Cattle prefer grazing a flat landscape, so stick to the coastline and to the even terrain inland. We tromp northward, flushing sandpipers from the verdant carpet. A peppery bouquet floats on the still air. A cabbagey scent of yarrow dominates whiffs of sedges and grasses, wild geraniums and flag irises, buttercups and chocolate lilies.

Since the end of the last ice age, Chirikof has been mostly tundra-like: no trees, sparse low brush, tall grasses, and boggy. Until the cattle arrived, the island never had large terrestrial mammals, the kind of grazers and browsers that mold a landscape—mammoths, mastodons, deer, caribou. But bovids have fashioned a pastoral landscape that a hiker would recognize in crossing northern England, a place that cows and sheep have kept clear for centuries. The going is easy, but Baker and I struggle to keep pace with the galloping Saltonstall, and we can’t help but stop to gape at bull and cow skeletons splayed across the grasses. We skirt a ground nest with three speckled eggs, barely hidden by the low scrub. We cut across a beach muddled with plastics—ropes, bottles, floats—and reach a giant puddle with indefinable edges, its water meandering toward the sea. “We call it the river Styx,” Saltonstall says. “The one you cross into hell.”

Compared with the Emerald City behind us, the underworld across the Styx is a Kansas dust bowl, a sandy mess that looks as if it could swallow us. Saltonstall tells us about a previous trip when he and his colleagues pulled a cow out of quicksand. Twice. “It charged us—and we’d saved its life!”

Hoof prints scatter from the river. At one time, the river Styx probably supported a small pink salmon run. A team of biologists reported in 2016 that several Chirikof streams host pink and coho, with cameo appearances of rainbow trout and steelhead. This stream is likely fish-free, the erosion too corrosive, a habitat routinely trampled.

Two raptors—jaegers—cavort above us. A smaller bird’s entrails unspool at our feet. On a sandy bluff, Saltonstall pauses to look for artifacts while Baker and I climb down to a beach where hungry cattle probably eat seaweed in winter. We follow a ground squirrel’s tracks up the bluff to its burrow, and at the top meet Saltonstall, who holds out his hands: stone tools. Artifacts sprinkle the surface as if someone has shaken out a tablecloth laden with forks, knives, spoons, and plates—an archaeological site with context ajumble. A lone bovid’s track crosses the sand, winding through shoulder blades, ribs, and the femoral belongings of relatives.

After four hours of hiking, we turn toward the lake where we left our gear. So far on this hike, dead cattle outnumber live ones, dozens to zero. But wait! What’s that? A bull appears on a rise, across a welcome mat of cotton grass. Curious, he jogs down. Baker and Saltonstall peer through viewfinders and click off images. The bull stops several meters away; we stare at each other. He wins. We turn and walk away. When I look back, he’s still paused, watching us, or—I glance around—watching a distant herd running at us.

Again, my calm comrades-in-arms lift their cameras. I lift my iPhone, which shakes because I’m scared. Should I have my hands on the pepper spray I borrowed from Ruoss and Murphy? Closer, closer, closer they thunder, until I can’t tell the difference between my pounding heart and their pounding feet. Then, in sync, the herd turns 90 degrees and gallops out of the frame. The bull lollops away to join them. Their cattle plans take them elsewhere.

Saltonstall has surveyed archaeology sites three times on Chirikof. The first time, in 2005, he carried a gun to hunt the cattle, but his colleagues were also apprehensive about the feral beasts. At least one person I talked to suggested we bring a gun. But Saltonstall says he learned that cattle are cowards: Stand your ground, clap, and cows and bulls will run away. But to me, big domesticated herbivores are terrifying. Horses kick and bite, cattle can crush you. The rules of bears—happier without humans around—are easier to parse. I’ve never come close to pepper spraying a bear, but I’m hot on the trigger when it comes to cattle.

The next morning, we set out for the Old Ranch, one of the two homesteads built decades ago on the island and about a three-hour amble one way. Ruoss won’t be picking us up till 3 pm, so we have plenty of time. The cattle path we’re following crosses a field bejeweled with floral ambers, opals, rubies, sapphires, amethysts, and shades of jade. It’s alive with least sandpipers, a shorebird that breeds in northern North America, with the males arriving early, establishing their territories, and building nests for their mates. The least sandpiper population, in general, is in good shape—they certainly flourish here. High-pitched, sped-up laughs split the air. They slice the wind and rush across the velvet expanse. Their flapping wings look impossibly short for supporting flights from their southern wintering grounds, sometimes as far away as Mexico, over 3,000 kilometers distant. They flutter into a tangle of green and vanish.

From a small rise, we spot cattle paths meandering into the distance, forking again and again. Saltonstall announces the presence of the only other mammal on the island. “A battery killer,” he says, raising his camera at an Arctic ground squirrel, and he’s right. They are adorable. They stand on two legs and hold their food in their hands. To us humans, that makes them cute. Pretty soon, we’re all running down the batteries on our cameras and smartphones.

Qanganaq is Alutiiq for ground squirrel. An Alutiiq tailor needed around 100 ground squirrels for one parka, more precious than a sea otter cloak. Some evidence suggests the Alutiiq introduced ground squirrels to Chirikof at least 2,000 years ago, apparently a more rational investment than cattle. Squirrels were easily transported, and the market for skins was local. Still, they were fancy dress, Dehrich Chya, the Alutiiq Museum’s Alutiiq language and living culture manager, told me. Creating a parka—from hunting to sewing to wearing—was an homage to the animals that offered their lives to the Alutiiq. Archaeologist Catherine West and her crew have collected over 20,000 squirrel bones from Chirikof middens, a few marked by tool use and many burned.

Chirikof has been occupied and abandoned periodically—the Alutiiq quit the island, perhaps triggered by a volcanic eruption 4,000 years ago, then came people more related to the Aleuts from the west, then the Alutiiq again. Then, Russian colonizers arrived. The Russians lasted not much longer than the American cattle ranchers who would succeed them. That last, doomed culture crumbled in less than 100 years, pegged to an animal hard to transport, with a market far, far away.

Whether ground squirrels, some populations definitely introduced, should be in the Alaska Maritime is rarely discussed. One reason, probably, is that they are small and cute and easy to anthropomorphize. There is a great body of literature on why we anthropomorphize. Evolutionarily, cognitive archaeologists would argue that once we could anthropomorphize—by at least 40,000 years ago—we became better hunters and eventually herders. We better understood our prey and the animals we domesticated. Whatever the reason, researchers tend to agree that to anthropomorphize is a universal human behavior with profound implications for how we treat animals. We attribute humanness based on animals’ appearance, familiarity, and non-physical traits, such as agreeability and sociality—all factors that will vary somewhat across cultures—and we favor those we humanize.

Ungulates, in general, come across favorably. Add a layer of domestication, and cattle become even more familiar. Cows, especially dairy cows named Daisy, can be sweet and agreeable. Steve Ebbert, a retired USFWS wildlife biologist living on the Alaska mainland outside Homer, eradicated foxes, as well as rabbits and marmots, from islands in the refuge. Few objected to eliminating foxes—or even the rabbits and marmots, he told me. Cattle are more complicated. Humans are supposed to take care of them, he said, not shoot them or let them starve and die: they’re for food—and of course, they’re large, and they’re in a lot of storybooks, and they have big eyes. Alaskans, like many US westerners, are also protective of the state’s ranching legacy—cattle ranchers transformed the landscape to a more familiar place for colonizers and created an American story of triumph, leaving out the messy bits.

We spot a herd of mostly cows and calves, picture-book perfect, with chestnut coats and white faces and socks. We edge closer, but they’re wary. They trot away.

Saltonstall, always a few leaps and bounds ahead, spots the Old Ranch—or part of it. A couple of bulls are hanging out near the sagging, severed rooms that cling to a cliff above the sea, refusing their fate. Ghostly fence posts march from the beach across a rolling landscape.

Close by is a wire exclosure, one of five Ebbert and his colleagues set up in 2016. The exclosure—big enough to park a quad—keeps out cattle, allowing an unaggravated patch of land to regenerate. Beach rye taller than cows soars within the fencing. This is what the island looks like without cattle: a haven for ground-nesting birds. The Alutiiq relied on beach rye, weaving the fiber into house thatching, baskets, socks, and other textiles; if they introduced ground squirrels, they knew what they were doing, since the rodents didn’t drastically alter the vegetation the way cattle do.

Saltonstall approaches a shed set back from the eroding cliff.

“Holy cow!” he hollers. No irony. He is peering into the shed.

On the floor, a cow’s head resembles a Halloween mask, horns up, eye sockets facing the door, snout resting close to what looks like a rusted engine. Half the head is bone, half is covered with hide and keratin. Femurs and ribs and backbone scatter the floor, amid bits and bobs of machinery. One day, for reasons unknown, this cow wedged herself into an old shed and died.

Cattle loom large in death, their bodies lingering. Their suffering—whether or not by human hands—is tangible. Through size, domestication, and ubiquity, they take up a disproportionate amount of space physically, and through anthropomorphism, they grab a disproportionate amount of human imagination and emotion. When Frank Murkowski said Alaska should leave one island to the cattle, he probably pictured a happy herd rambling a vast, unfenced pasture—not an island full of bones or heifer-buckling bulls.

Birds are free, but they’re different. They vanish. We rarely witness their suffering, especially the birds we never see at backyard feeders—shorebirds and seabirds. We witness their freedom in fleeting moments, if at all, and when we do see them—gliding across a beach, sipping slime from an intertidal mudflat, resting on a boat rail far from shore—can we name the species? As popular as birding is, the world is full of non-birders. And so, we mistreat them. On Chirikof, where there should be storm petrels, puffins, and terns, there are cattle hoof prints, cattle plops, and cattle bones.

Hustling back to meet the seaplane, we skirt an area thick with cotton grass and ringed by small hills. In 2013, an ornithologist recorded six Aleutian terns and identified one nest with two eggs. In the United States, Aleutian tern populations have crashed by 80 percent in the past few decades. The tern is probably the most imperiled seabird in Alaska. But eradicating foxes, which ate birds’ eggs and babies, probably helped Chirikof’s avian citizens, perhaps most notably the terns. From a distance, we count dozens of birds, shooting up from the grass, swirling around the sky, and fluttering back down to their nests.

Terns may be dipping their webbed toes into a bad situation, but consider the other seabirds shooting their little bodies through the atmosphere, spotting specks of land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean to raise their young, and yet it’s unsafe for them on this big, lovely island. The outcry over a few hundred feral cattle—a loss that would have absolutely no effect on the species worldwide—seems completely irrational. Emotional. A case of maladaptive anthropomorphism. If a species’ purpose is to proliferate, cattle took advantage of their association with humans and won the genetic lottery.

Back at camp, we haul our gear to the lake. Ruoss arrives slightly early, and while he’s emptying red jerrycans of fuel into the Beaver, we grab tents and packs and haul them into the pontoons. Visibility today is even better than yesterday. I watch the teardrop-shaped island recede, thinking of what more than one scientist told me: when you’re on Chirikof, it’s so isolated, surrounded by whitecaps, that you hope only to get home. But as soon as you leave, you want to go back.

Chirikof cattle are one of many herds people have sprinkled around the world in surprising and questionable places. And cattle have a tendency to go feral. On uninhabited Amsterdam Island in the Indian Ocean, the French deposited a herd that performed an evolutionary trick in response to the constraints of island living: the size of individuals shrank in the course of 117 years, squashing albatross colonies in the process. In Hong Kong, feral cattle plunder vegetable plots, disturb traffic, and trample the landscape. During the colonization of the Americas and the Caribbean, cattle came to occupy spaces violently emptied of Indigenous people. Herds ran wild—on small islands like Puerto Rico and across expanses in Texas and Panama—pulverizing landscapes that had been cultivated for thousands of years. No question: cattle are problem animals.

A few genetic studies explore the uniqueness of Chirikof cattle. Like freedom, “unique” is a vague word. I sent the studies to a scientist who researches the genetics of hybrid species to confirm my takeaway: the cattle are hybrids, perhaps unusual hybrids, some Brown Swiss ancestry but mostly British Hereford and Russian Yakutian, an endangered breed. The latter are cold tolerant, but no study shows selective forces at play. The cattle are not genetically distinct; they’re a mix of breeds, the way a labradoodle is a mix of a Labrador and a poodle.

Feral cattle graze unusual niches all over the world, and maybe some are precious genetic outliers. But the argument touted by livestock conservancies and locals that we need Chirikof cattle genes as a safeguard against some future fatal cattle disease rings hollow. And if we did, we might plan and prepare: freeze some eggs and sperm.

Cattle live feral lives elsewhere in the Alaska Maritime, too, on islands shared by the refuge and Indigenous owners or, in the case of Sitkinak Island, where a meat company grazes cattle. Why Frank Murkowski singled out Chirikof is puzzling: Alaska will probably always have feral cattle. Chirikof cattle, of use to practically no one, fully residing within a wildlife refuge a federal agency is charged with protecting for birds, with no concept of the human drama swirling around their presence, have their own agenda for keeping themselves alive. Unwittingly, humans are part of the plan.

We created cattle by manipulating their wild cousins, aurochs, in Europe, Asia, and the Sahara beginning over 10,000 years ago. Unlike Frankenstein’s monster, who could never find a place in human society, cattle trotted into societies around the world, making themselves at home on most ranges they encountered. Rosa Ficek, an anthropologist at the University of Puerto Rico who has studied feral cattle, says they generally find their niche. Christopher Columbus brought them on his second voyage to the Caribbean in 1493, and they proliferated, like the kudzu of the feral animal world. “[Cattle are] never fully under the control of human projects,” she says. They’re not “taking orders the way military guys are … They have their own cattle plans.”

The larger question is, Why are we so nervous about losing cattle? In terms of sheer numbers, they’re a successful species. There is just over one cow or bull for every eight people in the world. If numbers translate to likes, we like cows and bulls more than dogs. If estimates are right, the world has 1.5 billion cattle and 700 million dogs. Imagine all the domesticated animals that would become feral if some apocalypse took out humans.

I could say something here about how vital seabirds—as opposed to cattle—are to marine ecosystems and the overall health of the planet. They spread their poop around the oceans, nurturing plankton, coral reefs, and seagrasses, which nurture small plankton-eating fishes, which are eaten by bigger fishes, and so on. Between 1950 and 2010, the world lost some 230 million seabirds, a decline of around 70 percent.

But maybe it’s better to end with conjuring the exquisiteness of seabirds like the Aleutian terns in their breeding plumage, with their white foreheads, black bars that run from black bill to black-capped heads, feathers in shades of grays, white rump and tail, and black legs. Flashy? No. Their breeding plumage is more timeless monochromatic, with the clean, classic lines of a vintage Givenchy design. The Audrey Hepburn of seabirds. They’re so pretty, so elegant, so difficult to appreciate as they flit across a cotton grass meadow. Their dainty bodies aren’t much longer than a typical ruler, from bill to tail, but their wingspans are over double that, and plenty strong to propel them, in spring, from their winter homes in Southeast Asia to Alaska and Siberia.

A good nesting experience, watching their eggs hatch and their chicks fledge, with plenty of fish to eat, will pull Aleutian terns back to the same places again and again and again—like a vacationing family, drawn back to a special island, a place so infused with good memories, they return again and again and again. That’s called fidelity.

Humans understand home, hard work, and family. So, for a moment, think about how Aleutian terns might feel after soaring over the Pacific Ocean for 16,000 kilometers with their compatriots, making pit stops to feed, and finally spotting a familiar place, a place we call Chirikof. They have plans, to breed and nest and lay eggs. The special place? The grassy cover is okay. But, safe nesting spots are hard to find: Massive creatures lumber about, and the terns have memories of loss, of squashed eggs, and kicked chicks. It’s sad, isn’t it?

This story was made possible in part by the Fund for Environmental Journalism and the Society of Environmental Journalists and was published in collaboration with Earth Island Journal.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I've had this AU for TTL floating around in my head since pretty much the beginning that's basically a "what would happen if Janus was just a little too slow in escaping and was grabbed by the Prince Pride of the Unseelie". It's a total shit show and it's on my mind so I want to talk about it.

Basically, Janus manages to get Virgil out safely but can't save himself. He gets horrifically tortured by the somewhat rogue unseelie princes. Virgil can't save Janus but he somehow uses the claim and idk some other magic (the spirit species might be involved) to project a sort of ghostly version of himself to keep Janus company through it all so that he's not alone. Janus is, eventually, killed.

The unseelie deliver his mutilated body to his family. They don't take it well. King Thomas doesn't start a war over it for the sake of his people but naturally, nothing will ever be the same. What Thomas does do is gift more magic to each of his remaining sons and Remy so that they're more powerful and it's less likely for history to repeat itself.

Here's the twist: What if Janus is resurrected centuries later? He'd come back to find:

All of his siblings drastically changed because of his death

Thomas is dead

Roman is king

Roman started a war against humans to avenge Janus (but not the unseelie because he knows he won't win that war which is bullshit)

Roman got married only for his husband and Remy to team up and run away because the new Roman became abusive and a cheater

Remus has become ostracized from the rest of the family

Without Janus there to help him and without the rest of the family supporting him Remus lost his mind and became hellbent on killing as many humans as he could because it's the only vengeance he can get

The seelie are hunting Virgil because he was last seen with Janus and they wildly misunderstood the situation

Virgil has been hiding out in an uninhabited section of the fae realm and has been taking good care of himself because Janus believed he was worth saving

Remy and Virgil know each other and have bonded over their love for Janus and them both being part drider

Remy has been disguising himself as human and is hiding on Earth working in a rehabilitation center for victims of fae particularly humans who were unwillingly claimed and then freed

Remy and Remus teamed up to manipulate the humans into helping them resurrect Janus because they miss him but also because they know he's the only one who has a chance of actually fixing everything

Is anyone interested in this? Does anyone want to ask questions or give me a reason to ramble because this AU lives in my head rent free and it's on my mind right now. I've been listening to my playlist for it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, while you're answering SR asks---one thing that I wasn't clear on after reading through the tag. SR has a really _deep_ history of human civilization, tens of thousands of years or more, right? and it's definitely explicit that a lot of cultures have lost technology over time, or explicitly stopped "progressing" technologically (that one plateau culture), which is why it's bounced around basically the same tech level that whole time (with anachrotech pockets). But I'm not clear on _why_ that is.

Is it 1. that you're implying that this is actually likely to happen to any civilization on long timescales, and modern Earth monotonic progress is temporary, 2. that it's caused somehow by the semisymbiotic native SR life (some of the stories seem to imply periodic catastrophes driven by its influence? are those frequent & big enough to hold tech progress back overall?) 3. SR society Just Does That because of some combination of resource factors and social structures 4. something else?

Your intuitions are correct--there is indeed a reason for it! It's mostly the second thing.

But there have actually been two great technological stagnations in the history of humanity, and the longer and bigger one was before they arrived on Sogant Raha.

In order for the setting to work (mostly-terraformed alien planet), humans had to have some means of resurrecting species from genetic samples or records, but my intention was always that the beginning of the Exile is very much a near-future, or possibly alternate-present event: humans were forced to spread out among the stars by a catastrophe that made Earth at least temporarily uninhabitable, and they did so, at least initially, with crude Project Orion-type spacecraft, because that's all they had available. This universe doesn't have FTL travel, and Earthlike worlds are comparatively rare, so even when they settled in other solar systems, they did so in pressure domes and grew their food hydroponically.

This created a situation not incomparable to the Paleolithic phase of human history on Earth: extremely slow population growth, very little spare productive capacity, little room for experimentation or innovation. For the exiles who eventually arrived at Sogant Raha aboard the Ammas Echor, this era lasted about four hundred thousand years. The people of the Ammas Echor would have been more technologically advanced than the first exiles who left Earth, but not fantastically so. They simply did not have the resource budget for it. Nowadays, we can afford to invest in experimentation and in r&d that may not pan out; in an environment when even a small hit to your energy budget means people are going to die, you stick with the techniques you know for a fact work, and if you innovate, you do so slowly.

Once the Ammas Echor reached Sogant Raha, simply the fact they could walk around in an oxygen-rich atmosphere that was a comfortable temperature and grow food in any patch of open ground that got good sunlight would have been a phenomenal luxury. They certainly had the technology to grow quickly, and to rapidly innovate again. And they did aim to do that, at first (despite, y'know, centuries of hidebound traditionalism that come from hidebound traditionalism being the difference between survival and extinction of your whole lineage). But catastrophe soon struck in the form of a virulent disease that seemed to be caused by native alien microorganisms.

There were other catastrophes after, and some were human-caused (devastating wars, or environmental collapses like the Burning Spring). But many were not; many can indeed be traced back to the tahar, the genus of acytic symbiont that makes its home in the tissues and cells of endobiota and xenobiota alike. These have probably been equal to, or significantly worse than, many of the purely "human-caused" disasters. But the dividing line isn't always so clear; if an apparently random mutation in the tahar's signalling mechanism is, as a side effect, causing heightened aggression across a whole continent for a hundred years, then the wars that result might well be a human disaster, but in a purely causal sense they're not solely humanity's fault.

I think left to their own devices--if they had found a world without the tahar--the people of the Ammas Echor would have rapidly built up an industrial base and flourished. Indeed, they had a rather fantastical idea at one point to try to build a beacon to signal to other exiles that Paradise had been found. Alas, the planet had other plans.

#the technology in use in any given civilization#is probably kind of schizophrenic#what technologies and techniques survive a collapse#will depend heavily on what materials can be locally sourced#and what manufacturing methods are still possible#and scientific knowledge might actually be much greater#than the capacity to utilize that knowledge#sogant raha#tanadrin's fiction#worldbuilding#conworlding

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I figure rambles about world building should maybe not go in the tags of a completely unrelated post so uhhhh tbi yggdrasil! (I was going to draw the planets to go with this but I kinda haven't yet) (I'm realizing j wrote all of this in present tense so assume this is as things were just before the train arrived) *infodump mode: activate!!*

my basic idea is 9 planets obviously, 4 of them within the goldilocks zone and with naturally occurring life, and 5 naturally uninhabitable but with enough artificial modifications that people can and do live there. there are also a few small colonies on some of the dwarf planets and asteroids in the system, with hoddmimis being the only one outside of the farthest planet niflheims orbit. all the naturally habitable planets are self sustaining, can produce all the resources necessary to support their populations, but they have grown more dependent on trade between the planets during the centuries that interplanetary travel has existed. the colonized planets are much more reliant on trade, although all have been modified enough they could provide for basic needs (food, water, power, etc) for a while if supplies were cut off for some reason. a closer look at each planet:

this is getting long the rest is under the cut :)

muspelheim: closest planet to the sun, inhabitants live almost exclusively underground. some mining takes place here but since it's not nearly as rich as nidavellir mining isn't pushed as heavily. it does produce most of the fuel used in the system. one of the most well known disasters in yggdrasil history was when a mining mishap led to a fuel tank ruprure that took out 200 square miles of space in a single explosion and started fires that raged for nearly a year. also notable for hosting the training grounds for the Asgard defense unit before it was phased out, replaced by the yggdrasil early alert force. at one point a few centuries before the planets were unified under Asgard, muspelheim got in a war with Niflheim. it would have been forced to a stop within a few decades since this was when Niflheim was the closest to the sun as it gets in it's orbit and after a few decades the two planets would be far enough apart to no longer justify the spent resources, but Asgard kindly put a stop to the conflict early by taking over both planets.

nidavellir: next furthest out. nidavellir is the site of many of the factories in yggdrasil. each planet has its own industrial district for (relatively) local products, but for big, expensive, heavy duty, or dangerous stuff such as spacecraft, heavy machinery, or weapons, it's nearly always made on nidavellir. safety standards were kind of shit during Odin's era but after the ratatosk express disappeared the citizens took the opportunity to set up stricter regulations. it was first settled for the pre in the crust, and is still mined centuries later. a method of extracting iron from the core is in development, but there is serious pushback since no one is sure how that would affect the planet and it's magnetic field in the long run. nidavellir is denser than earth and while it has no natural inhabitants, enough generations have passed on this planet that the people have somewhat adapted. they tend to be shorter and can take higher temperatures than humans could.

hel: the first planet outside of the goldilocks zone that was settled. at the start people mostly went there to prove they could, to show living beings could conquer an uninhabitable world, but at the time they hadn't figured out how to set up truly long lasting infrastructure in a way that would allow them to have a large population on a new planet, so population remained relatively low. when Asgard started taking over, they saw the amount of space available and decided hel would be a lovely place to put everyone who disagreed with the glory of Asgardian rule

and thus begins the handful of habitable planets

vanaheim: a gas giant in a twin planet rotation with asgard. they were the first two planets to make contact with each other. they went to war a few times but have been on good terms for centuries. vanaheims inhabitants, the vanir, live either on small moons in very close orbit or on floating cities suspended in the planet. the planet has a very scientific mindset and is the center for a lot of the research and development in the system, as well as home to some of the top universities. while Asgard was where the bifrost was constructed and tested, vanaheim was where much of the fundamental research was done. the vanir are winged and somewhat reptilian, they can reproduce asexually if necessary, tend to be slightly carnivorous, and usually have large family units (polyamory win!)

Asgard: even after Asgardian rule was overturned it is still seen as a cultural capital of sorts. it was home to the entire government setup during Asgard's rule, including the shoddy attempt at a senate set up to convince the people of other planets they had some representation. after the train, there was a complete restructuring of most of the government and the locations were shifted over to midgard as it was more central to the whole system. Asgard is smaller than earth, the inhabitants are Tall. aside from that visibly similar to humans with the exception of pointed ears and bigger eyes

midgard: fairly similar to earth actually. it's the center of a lot of trade and sees a lot of intercultural activity since it's one of the most central planets at the moment (when the outer planets hit the other end of their orbit it will probably change). midgard has a lot of forests, and it's oceans are warmer because there is a lot of underwater volcanic activity. midgardians could be mistaken for humans except for pointed ears and better flexibility. if a midgardian can't do the spilts they are looked down on.

jotunheim: the coldest habitable world. it's inhabitants are tall and blue and can handle much colder temperatures. they tend to be good problem solvers. jotunn music and cuisine are both becoming increasingly popular. it has a bit of a bad reputation for crime in some spots but really so does every planet, Jotunheim just happened to be dragged into the spotlight for it. the Jotunheim equivalent of noir detective is a very popular character archetype.

the cold planets:

alfheim: home of a lot of data processors and storage centers, the cold makes it cheaper to run them at such high capacities. in Odin's reign Freyr was the governor of alfheim, he was born into an influential family on vanaheim and basically bought the position.