#vanessa & virginia: a novel

Photo

THE LONDON LIBRARY ANNOUNCES HELENA BONHAM CARTER CBE AS PRESIDENT

The London Library is delighted to announce Helena Bonham Carter CBE as its first female President. Proposed by the Library’s Trustees, the appointment was formally confirmed by members at the Annual General Meeting on 15 November 2022, also marking the end of incumbent President, Sir Tim Rice’s five-year term.

The new President has been a Library member since 1986 and has been chosen for her creativity and connections with literature and stories, her high profile and potential to advocate among new audiences.

Bonham Carter has a passion for books and deeply appreciates the importance of writers to the acting profession. Much of her own career links with London Library members who have drawn on the Library’s rich cultural heritage, extensive resources and unparalleled atmosphere. She rose to prominence by playing Lucy Honeychurch in the film adaptation of the novel A Room with a View (1985), written by former Library Vice President E.M. Forster. Later, she played Miss Havisham in Great Expectations (2012), Charles Dickens was a founding member of the Library, and more recently Eudoria Holmes in the Enola Holmes films based on characters created by Library member Arthur Conan Doyle.

Open to all, the Library has had innumerable female artists, writers and thinkers in membership throughout its 181-year history. Early members included pioneering women such as social theorist, Harriet Martineau, suffragette, Christabel Pankhurst and the first woman to qualifiy in Britain and a physician and surgeon, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. Great writers in membership have included Virginia Woolf, Angela Carter, Daphne du Maurier, Muriel Spark and Beryl Bainbridge, and other creatives such as actress, Diana Rigg, and artist, Vanessa Bell.

The Library Presidency is an honorary position with fundraising and advocacy at its core; the Library is a charity that receives no regular public funding. Bonham Carter’s first major duty will be to host The Library’s Christmas Party but she is particularly interested in the Library’s highly regarded Emerging Writers Programme, its growing schools programme, and the Library’s various types of supported membership for those unable to meet the full annual fee.

The Library is a world-class centre of creativity and inspiration. Around 700 books are published each year by Library members, and over 460 film scripts, TV screenplays or theatre scripts are also produced by Library members annually, estimating an annual value of £21.3m generated for the UK economy (Nordicity and Chartered Accountants Saffrey Champness Impact Report, 2020).

Helena Bonham Carter CBE, said: “I am delighted to become The London Library’s first female President and to champion an institution that is open to all. The Library is truly a place like no other, inspiring and supporting writers for over 180 years, many of whom have in some way informed my own career and those of actors everywhere. The Library’s unique resources, history and membership help to connect the literary greats of the past with those of the future, and I am proud to support this incredible and vital establishment.”

Philip Marshall, Director of The London Library said: ‘We are all thrilled to welcome Helena Bonham Carter as our new President. With a passion for books and stories, and a long-standing love of the Library, Helena is ideally placed to promote this tremendous resource for the creative and curious.’

Photo credit: Sane Seven

#news#helena bonham carter#the london library#2022#sane seven 2022#photoshoots#photoshoots: 2022#the hbic stays winning 👑

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo of Angelica Bell, daughter of Vanessa Bell and niece of Virginia Woolf, in costume as the Russian Princess from Woolf’s novel Orlando.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Virginia Woolf’s diary, November 23, 1926:

“Life is as I’ve said since I was ten, awfully interesting – if anything, quicker, keener at forty-four than twenty-four – more desperate I suppose, as the river shoots to Niagara – my new vision of death. ‘The one experience I shall never describe’ I said to Vita yesterday.”

Vita Sackville-West in a letter to husband Harold Nicolson, November 30, 1926:

“Darling, I know that Virginia will die, and it will be too awful. (I don’t mean here, over the weekend; but just die young.)”

*

“On 28 March 1941, Virginia left her last letter on the writing block in her garden lodge. It was a note to Leonard which thanked him for giving her ‘complete happiness […] from the very first day till now’. She then walked the half-mile to the River Ouse, filled her pockets with stones, and threw herself into the water.

Letter from Vita to Harold

Sissinghust Castle

31 March

“I’ve just had the most awful shock: Virginia has killed herself. It is not in the papers, but I got letters from Leonard and also from Vanessa telling me. It was last Friday. Leonard came home to find a note saying that she was going to commit suicide, and they think she had drowned herself as they found her stick floating on the river. He says she had not been well for the last few weeks and was terrified of going mad again. He says, ‘It was, I suppose, the strain of the war and finishing her book, and she could not rest or eat.’

“I simply can’t take it in. That lovely mind, that lovely spirit. And she seemed so well when I last saw her, and I had a jokey letter from her only a couple of weeks ago.”

*

“Virginia’s body was discovered on 18 April. She was cremated at Brighton on 21 April, with only Leonard present. Her ashes were buried under an elm tree at Monk’s House, with the penultimate words of The Waves as her epitaph: ‘Against you I will fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death!’

“As soon as Harold heard the news, he came down to Sissinghurst to be with Vita. Many years later she wrote, ‘I still think that I might have saved her if only I had been there and had known the state of mind she was getting into.’

Vita died from cancer on 2 June 1962. Her writing desk at Sissinghurst remains as she left it, decorated with two photos: one is of her husband, and the other is of Virginia.”

From Love Letters: Vita and Virginia

.

.

How did I not know, until now, that Woolf’s epitaph was from the closing of The Waves; it refers to the same Great Wave I once saw, in a vision, folding over everyone I love, the wave that Bernard proudly pitched himself against at the end of the novel, the same wave that forms in the mind before one can find words, when the pulse precedes semantic meaning. To read a life backward from a suicide—one finds clues everywhere: a sudden unspeakable vision of a rushing river, the lover-friend struck by the startling knowledge, she will die, and it will be too awful.

#literature#virginia woolf#death#water#oceanic feeling#river#rivers#vita sackville west#the waves#waters of oblivion#suicide

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Evans Hartman, Jr. October 27, 1943 - February 17, 2023 We are sad to announce the passing of Charles "Chick" Evans Hartman, Jr., 79, of Greenville, South Carolina. Chick was surrounded by his immediate family when he passed away on February 17, 2023, from complications after heart surgery.

Chick was born to Charles and Harriet Hartman on October 27, 1943, in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Following graduation from Bob Jones Academy, he attended Bob Jones University, graduating with a degree in Business Administration. His career began at Bendix Corporation and then Burroughs Corporation in New Jersey. He went on to start and manage several investment banking companies in oil and gas, coal and real estate in New Jersey, Texas, New Mexico, West Virginia, Florida and South Carolina. Through the years, he experienced financial successes and losses but always brought an abundance of energy and business acumen to each venture and deeply appreciated the professional friendships forged through these endeavors. One of his favorite sayings was, "Tough times don't last, tough people do." Along the way, he taught at Clearwater Christian College and also helped establish their school of business. He was a proud Mason, member of the Monroe Lodge #244/Truth Lodge in Monroe, NC and later a member of Taylors Lodge No. 345, in Taylors, South Carolina.

Chick is survived by his former wife and best friend, Amanda "Betty" Hartman, and their three children, Vanessa Kormylo and her husband Matt, Heather Hartman and Eric Hartman. He also leaves behind his grandchildren Kathryn, Knox, Matthew and Andrew whom he loved dearly. Chick's sister, Mary McPheters, her husband Ralph, their three sons Mickey, Royce and Rex, and their families also survive him.

As a Presbyterian, Chick held a strong faith and belief in his Savior. He was known for his generous and optimistic spirit. He had a quick wit and great sense of humor, not usually known for holding back. Chick was an avid reader, enjoying a good spy novel in addition to a passion for history.

His heart was always in West Virginia where he spent many summers as a child with his beloved grandmother, Mary Blaney, on their family farm.

If you were to ask Chick what he was most proud of, he would without a doubt say his family. In times of bounty and times of hardship, he always made sure their needs were met. He enjoyed playing golf at Sawgrass during his time working in Florida, cooking and family meals together and the very special and always memorable family ski trips out west.

We are forever grateful for his love and care for us. He will be greatly missed.

Honoring Chick's wishes, his family will celebrate his life privately, with no public ceremony or service.

#Bob Jones University#BJU Hall of Fame#Obituary#BJU Alumni Association#2023#Charles E. Hartman#Class of 1965#Chick Hartman

0 notes

Text

On August 3, 1917, Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary for the first time in two years—a small notebook, roughly the size of the palm of her hand. It was a Friday, the start of the bank holiday, and she had traveled from London to Asheham, her rented house in rural Sussex, with her husband, Leonard. For the first time in days, it had stopped raining, and so she “walked out from Lewes.” There were “men mending the wall & roof” of the house, and Will, the gardener, had “dug up the bed in front, leaving only one dahlia.” Finally, “bees in attic chimney.”

It is a stilted beginning, and yet with each entry, her diary gains in confidence. Soon, Woolf establishes a pattern. First, she notes the weather, and her walk—to the post, or to fetch the milk, or up onto the Downs. There, she takes down the number of mushrooms she finds—“almost a record find,” or “enough for a dish”—and of the insects she has seen: “3 perfect peacock butterflies, 1 silver washed frit; besides innumerable blues feeding on dung.” She notices butterflies in particular: painted ladies, clouded yellows, fritillaries, blues. She is blasé in her records of nature’s more gruesome sights—“the spine & red legs of a bird, just devoured by a hawk,” or a “chicken in a parcel, found dead in the nettles, head wrung off.” There is human violence, too. From the tops of the Downs, she listens to the guns as they sound from France, and watches German prisoners at work in the fields, who use “a great brown jug for their tea.” Home again, and she reports any visitors, or whether she has done gardening or reading or sewing. Lastly, she makes a note about rationing, taking stock of the larder: “eggs 2/9 doz. From Mrs Attfield,” or “sausages here come in.”

Though Woolf, then thirty-five, shared the lease of Asheham with her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell (who went there for weekend parties), for her, the house had always been a place for convalescence. Following her marriage to Leonard in 1912, she entered a long tunnel of illness—a series of breakdowns during which she refused to eat, talked wildly, and attempted suicide. She spent long periods at a nursing home in Twickenham before being brought to Asheham with a nurse to recover. At the house, Leonard presided over a strict routine, in which Virginia was permitted to write letters—“only to the end of the page, Mrs Woolf,” as she reported to her friend Margaret Llewelyn Davies—and to take short walks “in a kind of nightgown.” She had been too ill to pay much attention to the publication of her first novel, The Voyage Out, in 1915, or to take notice of the war. “Its very like living at the bottom of the sea being here,” she wrote to a friend in early 1914, as Bloomsbury scattered. “One sometimes hears rumours of what is going on overhead.”

In the writing about Woolf’s life, the wartime summers at Asheham tend to be disregarded. They are quickly overtaken by her time in London, the emergence of the Hogarth Press, and the radical new direction she took in her work, when her first novels—awkward set-pieces of Edwardian realism—would give way to the experimentalism of Jacob’s Room and Mrs. Dalloway. And yet during these summers, Woolf was at a threshold in her life and work. Her small diary is the most detailed account we have of her days during the summers of 1917 and 1918, when she was walking, reading, recovering, looking. It is a bridge between two periods in her work and also between illness and health, writing and not writing, looking and feeling. Unpacking each entry, we can see the richness of her daily life, the quiet repetition of her activities and pleasures. There is no shortage of drama: a puncture to her bicycle, a biting dog, the question of whether there will be enough sugar for jam. She rarely uses the unruly “I,” although occasionally we glimpse her, planting a bulb or leaving her mackintosh in a hedge. Mostly she records things she can see or hear or touch. Having been ill, she is nurturing a convalescent quality of attention, using her diary’s economical form, its domestic subject matter, to tether herself to the world. “Happiness is,” she writes later, in 1925, “to have a little string onto which things will attach themselves.” At Asheham, she strings one paragraph after another; a way of watching the days accrue. And as she recovers, things attach themselves: bicycles, rubber boots, dahlias, eggs.

***

Between 1915 and her death in 1941, Woolf filled almost thirty notebooks with diary entries, beginning, at first, with a fairly self-conscious account of her daily life which developed, from Asheham onward, into an extraordinary, continuous record of form and feeling. Her diary was the place where she practiced writing—or would “do my scales,” as she described it in 1924—and in which her novels shaped themselves: the “escapade” of Orlando written at the height of her feelings for Vita Sackville-West (“I want to kick up my heels & be off”); the “playpoem” of The Waves, that “abstract mystical eyeless book,” which began life one summer’s evening in Sussex as “The Moths.” There are also the minutiae of her domestic life, including scenes from her marriage to Leonard (an argument in 1928, for instance, when she slapped his nose with sweet peas, and he bought her a blue jug) and from her relationship with her servant, Nellie Boxall, which was by turns antagonistic and dependent. Most of all, the diary is the place in which she thinks on her feet, playing and experimenting. Here she is in September 1928, attempting to describe rooks in flight, and asking,

“Whats the phrase for that?” & try to make more & more vivid the roughness of the air current & the tremor of the rooks wing <deep breasting it> slicing—as if the air were full of ridges & ripples & roughnesses; they rise & sink, up & down, as if the exercise <pleased them> rubbed & braced them like swimmers in rough water.

But the “old devil” of her illness was never far behind. If, in her diary, Woolf could compose herself, she could also unravel. There are jagged moments. She could be cruel—about her friends, or the sight of suburban women shopping, or Leonard’s Jewish mother. And she felt her failures acutely. In the small hours, she fretted over her childlessness, her rivalries, the wave of her depression threatening to crest.

Her diaries’ elasticity, their ability to fulfill all these uses, is, as Adam Phillips notes in his foreword to Granta’s new edition of the second volume, evidence of “Woolf’s extraordinary invention within this genre.” The Asheham diary was one of her earliest experiments in the form. She was reading Thoreau’s Walden and Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere journals, marvelling at those writers’ capacity for a language “scraped clean,” their daily lives, and their descriptions of the natural world, intensified for the reader as if “through a very powerful magnifying glass.” Yet the life span of her own rural diary was short. In October 1917, upon her return to London, Woolf began a second diary, written in the style of those which preceded her breakdowns. Her Asheham diary she left stowed away in a drawer. (When, the following summer, she reached for the notebook, writing in both concurrently, it was the only time she kept two diaries at once.) In her other diary, the ligatures loosened, and she began developing the supple, longhand style she would use for the rest of her life. Her concision was gone, though her Asheham diary had left its mark. In London, she continued to open each day with her “vegetable notes”—an account of her walk along the Thames, or a note about the weather. And she described everything she saw with the curiosity and precision of a naturalist’s eye.

***

In the long and often fraught history of the publication of Virginia Woolf’s diaries, no one has known what to do with such a sporadic notebook, seemingly out of sync with the much fuller diaries that came before and after it. Following Leonard’s selection of entries for A Writer’s Diary, which was published in 1953, work on the publication of her diaries in their entirety began in 1966, when the art historian Anne Olivier Bell was assisting her husband, Quentin Bell, in the writing of his aunt’s biography. As parcels of Woolf’s papers arrived at the couple’s home in Sussex, Olivier—the name by which she was always known—realized the scale of the project, which involved organizing, noting, and indexing 2,317 pages of Woolf’s private writing. She leaped at the chance, “largely,” she later reflected, “because it gave me an excuse to read Virginia’s diary, which I longed to do.” So began nearly twenty years of scholarship, culminating in their publication, in five volumes, by the Hogarth Press, between 1977 and 1984.

It was a laborious process. Working first from carbon copies—which needed to be pieced back together after Leonard had gone through them, with scissors, to make his selections —and later from photocopies (the manuscript diaries were moved in 1971 from the Westminster Bank in Lewes to the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library), Olivier set about constructing her “scaffolding”: she took six-by-four-inch index cards, one for each month of Woolf’s life, and recorded on them the dates in that month on which Woolf had written an entry, where she had been, and who she had seen. Olivier spent long hours in the basement of the London Library, consulting the Dictionary of National Biography for details of one of Virginia’s friends, or decaying editions of the Times for a notice about a particular concert at Wigmore Hall. And there were decisions to make. What to do with Woolf at her most unkind, or snobbish? Olivier devised some basic rules for inclusion: she pinned a piece of paper above her desk that read ACCURACY / RELEVANCE / CONCISION / INTEREST. She decided there was little point in upsetting those friends still living, and cut any particularly unflattering descriptions. And Woolf’s Asheham diary—“too different in character” from the other diaries, she noted, and “too laconic”—didn’t merit publishing in full. The second volume, from the summer of 1918, was omitted completely.

This summer, Granta has reissued Woolf’s diaries and billed them as “unexpurgated,” a promise that has caused no small stir among Woolf scholars, who had thought Olivier’s editions were complete. The new inclusions are, in fact, mostly minor: a handful of comments about Woolf’s friends, written toward the end of her life, including an unpleasant description of Igor Anrep’s mouth. Otherwise, Olivier’s volume divisions remain unchanged, her notes and indexes intact; it is as much a reproduction, and a celebration, of her scholarly masterpiece as of Woolf’s diaristic eye. The most significant addition is Asheham. For the first time, Woolf’s small diary—the last remaining autobiographical fragment to be published—appears in its entirety. And yet those readers turning to Granta’s edition for details of Woolf’s country life in 1918 must skip to the end of the first volume, and look for her diary beneath the heading “Appendix 3.”

***

Appendixes can be awkward, unwieldy things. They serve a scholarly function—to present information deemed unsuitable for the main body of a text, like an attachment, or an afterthought. And an appendix is an especially odd place for a diary, putting time out of sequence, disrupting the “current”—as Woolf liked to call it—of everyday life. The remaining paragraphs of the Asheham diary have been relegated behind the main text; they sit quietly, unobtrusively, documenting a life as minute and domestic as before. Returning to the house in 1918, Woolf records her days, the winter melting into spring—the last of the diary, and the war. Out on her walks, she sees “a few brown heath butterflies,” the air “swarming with little black beetles.” She spends afternoons on the terrace, the sun hot, “had to wear straw hat,” and in the evening, she and Leonard sit “eating our own broad beans—delicious.” There are more local intrigues: the coal from the cellar goes missing, a mysterious plague kills the farmer’s lambs. Day by day, she watches a caterpillar pupate. The news is better from France. Still, the German prisoners work in the fields. “When alone, I smile at the tall German.” But her entries are thinning. By September, there is “nothing to notice” on the Downs, or “nothing new.” Even the butterflies are less brilliant—a few tortoiseshells, some ragged blues. Finally, toward the back of the notebook, she lists the household linen to be washed.

Her attention had begun shifting elsewhere. In London, she was becoming intensely preoccupied with the Press, and with writing shorter things, impressions and color studies—the pieces that will make up her first book of stories, Monday or Tuesday, published in 1921. And yet, if one looks closely, one can see the diary in some of these stories; something like an underpainting.

Take, for instance, Katherine Mansfield’s visit to Asheham in August 1917. The diary’s summary of Katherine’s visit is brief: her train into Lewes was late, so Woolf bought a bulb for the flowerbed; later, the two writers walked on the terrace together, an airship maneuvering overhead. Yet from letters, we know that the manuscript for Woolf’s “Kew Gardens” was almost certainly brought out. In it, we can see the imprint of Asheham, its reversal of scales, its teeming insect life. In the story, which was published in 1919, human life takes place off center, in the murmur of conversation wafting above the flower bed, while the “vast green spaces” of the bed and the snail laboring over his crumbs of earth loom largest of all. The story, though set in Richmond, captures the atmosphere of Asheham. Its form, like the other stories in Monday or Tuesday, owes much to the episodic structure of her diary, in which impressions are hazy, words come and go, and attention is both microscopic and abstract. And its authorial presence mirrors the one we find in the notebook—a writer who is both there and not there, looking and noticing.

Toward the end of 1918, as Woolf’s convalescence comes to an end, so does her Asheham diary. Back in London, she muses on the project she has kept going for two years: “Asheham diary drains off my meticulous observations of flowers, clouds, beetles & the price of eggs,” she writes in her other, longer diary, “&, being alone, there is no other event to record.” It has served its purpose, paving a way back to writing after illness, of nursing her attention back to life. Though it was later forgotten, it always stood for one of her quietest and arguably most important periods, between her first attempts at writing and those fleeting experiments which determined the novels that came afterward. And it continued to be a storehouse for images to be drawn upon later—her nephews, Julian and Quentin Bell, carrying home antlers, like those in the attic nursery in To The Lighthouse; a grass snake on the path, like the one Giles Oliver crushes with his tennis shoe in Between the Acts; a continuous stream of butterflies and moths.

0 notes

Text

On August 3, 1917, Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary for the first time in two years—a small notebook, roughly the size of the palm of her hand. It was a Friday, the start of the bank holiday, and she had traveled from London to Asheham, her rented house in rural Sussex, with her husband, Leonard. For the first time in days, it had stopped raining, and so she “walked out from Lewes.” There were “men mending the wall & roof” of the house, and Will, the gardener, had “dug up the bed in front, leaving only one dahlia.” Finally, “bees in attic chimney.”

It is a stilted beginning, and yet with each entry, her diary gains in confidence. Soon, Woolf establishes a pattern. First, she notes the weather, and her walk—to the post, or to fetch the milk, or up onto the Downs. There, she takes down the number of mushrooms she finds—“almost a record find,” or “enough for a dish”—and of the insects she has seen: “3 perfect peacock butterflies, 1 silver washed frit; besides innumerable blues feeding on dung.” She notices butterflies in particular: painted ladies, clouded yellows, fritillaries, blues. She is blasé in her records of nature’s more gruesome sights—“the spine & red legs of a bird, just devoured by a hawk,” or a “chicken in a parcel, found dead in the nettles, head wrung off.” There is human violence, too. From the tops of the Downs, she listens to the guns as they sound from France, and watches German prisoners at work in the fields, who use “a great brown jug for their tea.” Home again, and she reports any visitors, or whether she has done gardening or reading or sewing. Lastly, she makes a note about rationing, taking stock of the larder: “eggs 2/9 doz. From Mrs Attfield,” or “sausages here come in.”

Though Woolf, then thirty-five, shared the lease of Asheham with her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell (who went there for weekend parties), for her, the house had always been a place for convalescence. Following her marriage to Leonard in 1912, she entered a long tunnel of illness—a series of breakdowns during which she refused to eat, talked wildly, and attempted suicide. She spent long periods at a nursing home in Twickenham before being brought to Asheham with a nurse to recover. At the house, Leonard presided over a strict routine, in which Virginia was permitted to write letters—“only to the end of the page, Mrs Woolf,” as she reported to her friend Margaret Llewelyn Davies—and to take short walks “in a kind of nightgown.” She had been too ill to pay much attention to the publication of her first novel, The Voyage Out, in 1915, or to take notice of the war. “Its very like living at the bottom of the sea being here,” she wrote to a friend in early 1914, as Bloomsbury scattered. “One sometimes hears rumours of what is going on overhead.”

In the writing about Woolf’s life, the wartime summers at Asheham tend to be disregarded. They are quickly overtaken by her time in London, the emergence of the Hogarth Press, and the radical new direction she took in her work, when her first novels—awkward set-pieces of Edwardian realism—would give way to the experimentalism of Jacob’s Room and Mrs. Dalloway. And yet during these summers, Woolf was at a threshold in her life and work. Her small diary is the most detailed account we have of her days during the summers of 1917 and 1918, when she was walking, reading, recovering, looking. It is a bridge between two periods in her work and also between illness and health, writing and not writing, looking and feeling. Unpacking each entry, we can see the richness of her daily life, the quiet repetition of her activities and pleasures. There is no shortage of drama: a puncture to her bicycle, a biting dog, the question of whether there will be enough sugar for jam. She rarely uses the unruly “I,” although occasionally we glimpse her, planting a bulb or leaving her mackintosh in a hedge. Mostly she records things she can see or hear or touch. Having been ill, she is nurturing a convalescent quality of attention, using her diary’s economical form, its domestic subject matter, to tether herself to the world. “Happiness is,” she writes later, in 1925, “to have a little string onto which things will attach themselves.” At Asheham, she strings one paragraph after another; a way of watching the days accrue. And as she recovers, things attach themselves: bicycles, rubber boots, dahlias, eggs.

***

Between 1915 and her death in 1941, Woolf filled almost thirty notebooks with diary entries, beginning, at first, with a fairly self-conscious account of her daily life which developed, from Asheham onward, into an extraordinary, continuous record of form and feeling. Her diary was the place where she practiced writing—or would “do my scales,” as she described it in 1924—and in which her novels shaped themselves: the “escapade” of Orlando written at the height of her feelings for Vita Sackville-West (“I want to kick up my heels & be off”); the “playpoem” of The Waves, that “abstract mystical eyeless book,” which began life one summer’s evening in Sussex as “The Moths.” There are also the minutiae of her domestic life, including scenes from her marriage to Leonard (an argument in 1928, for instance, when she slapped his nose with sweet peas, and he bought her a blue jug) and from her relationship with her servant, Nellie Boxall, which was by turns antagonistic and dependent. Most of all, the diary is the place in which she thinks on her feet, playing and experimenting. Here she is in September 1928, attempting to describe rooks in flight, and asking,

“Whats the phrase for that?” & try to make more & more vivid the roughness of the air current & the tremor of the rooks wing <deep breasting it> slicing—as if the air were full of ridges & ripples & roughnesses; they rise & sink, up & down, as if the exercise <pleased them> rubbed & braced them like swimmers in rough water.

But the “old devil” of her illness was never far behind. If, in her diary, Woolf could compose herself, she could also unravel. There are jagged moments. She could be cruel—about her friends, or the sight of suburban women shopping, or Leonard’s Jewish mother. And she felt her failures acutely. In the small hours, she fretted over her childlessness, her rivalries, the wave of her depression threatening to crest.

Her diaries’ elasticity, their ability to fulfill all these uses, is, as Adam Phillips notes in his foreword to Granta’s new edition of the second volume, evidence of “Woolf’s extraordinary invention within this genre.” The Asheham diary was one of her earliest experiments in the form. She was reading Thoreau’s Walden and Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere journals, marvelling at those writers’ capacity for a language “scraped clean,” their daily lives, and their descriptions of the natural world, intensified for the reader as if “through a very powerful magnifying glass.” Yet the life span of her own rural diary was short. In October 1917, upon her return to London, Woolf began a second diary, written in the style of those which preceded her breakdowns. Her Asheham diary she left stowed away in a drawer. (When, the following summer, she reached for the notebook, writing in both concurrently, it was the only time she kept two diaries at once.) In her other diary, the ligatures loosened, and she began developing the supple, longhand style she would use for the rest of her life. Her concision was gone, though her Asheham diary had left its mark. In London, she continued to open each day with her “vegetable notes”—an account of her walk along the Thames, or a note about the weather. And she described everything she saw with the curiosity and precision of a naturalist’s eye.

***

In the long and often fraught history of the publication of Virginia Woolf’s diaries, no one has known what to do with such a sporadic notebook, seemingly out of sync with the much fuller diaries that came before and after it. Following Leonard’s selection of entries for A Writer’s Diary, which was published in 1953, work on the publication of her diaries in their entirety began in 1966, when the art historian Anne Olivier Bell was assisting her husband, Quentin Bell, in the writing of his aunt’s biography. As parcels of Woolf’s papers arrived at the couple’s home in Sussex, Olivier—the name by which she was always known—realized the scale of the project, which involved organizing, noting, and indexing 2,317 pages of Woolf’s private writing. She leaped at the chance, “largely,” she later reflected, “because it gave me an excuse to read Virginia’s diary, which I longed to do.” So began nearly twenty years of scholarship, culminating in their publication, in five volumes, by the Hogarth Press, between 1977 and 1984.

It was a laborious process. Working first from carbon copies—which needed to be pieced back together after Leonard had gone through them, with scissors, to make his selections —and later from photocopies (the manuscript diaries were moved in 1971 from the Westminster Bank in Lewes to the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library), Olivier set about constructing her “scaffolding”: she took six-by-four-inch index cards, one for each month of Woolf’s life, and recorded on them the dates in that month on which Woolf had written an entry, where she had been, and who she had seen. Olivier spent long hours in the basement of the London Library, consulting the Dictionary of National Biography for details of one of Virginia’s friends, or decaying editions of the Times for a notice about a particular concert at Wigmore Hall. And there were decisions to make. What to do with Woolf at her most unkind, or snobbish? Olivier devised some basic rules for inclusion: she pinned a piece of paper above her desk that read ACCURACY / RELEVANCE / CONCISION / INTEREST. She decided there was little point in upsetting those friends still living, and cut any particularly unflattering descriptions. And Woolf’s Asheham diary—“too different in character” from the other diaries, she noted, and “too laconic”—didn’t merit publishing in full. The second volume, from the summer of 1918, was omitted completely.

This summer, Granta has reissued Woolf’s diaries and billed them as “unexpurgated,” a promise that has caused no small stir among Woolf scholars, who had thought Olivier’s editions were complete. The new inclusions are, in fact, mostly minor: a handful of comments about Woolf’s friends, written toward the end of her life, including an unpleasant description of Igor Anrep’s mouth. Otherwise, Olivier’s volume divisions remain unchanged, her notes and indexes intact; it is as much a reproduction, and a celebration, of her scholarly masterpiece as of Woolf’s diaristic eye. The most significant addition is Asheham. For the first time, Woolf’s small diary—the last remaining autobiographical fragment to be published—appears in its entirety. And yet those readers turning to Granta’s edition for details of Woolf’s country life in 1918 must skip to the end of the first volume, and look for her diary beneath the heading “Appendix 3.”

***

Appendixes can be awkward, unwieldy things. They serve a scholarly function—to present information deemed unsuitable for the main body of a text, like an attachment, or an afterthought. And an appendix is an especially odd place for a diary, putting time out of sequence, disrupting the “current”—as Woolf liked to call it—of everyday life. The remaining paragraphs of the Asheham diary have been relegated behind the main text; they sit quietly, unobtrusively, documenting a life as minute and domestic as before. Returning to the house in 1918, Woolf records her days, the winter melting into spring—the last of the diary, and the war. Out on her walks, she sees “a few brown heath butterflies,” the air “swarming with little black beetles.” She spends afternoons on the terrace, the sun hot, “had to wear straw hat,” and in the evening, she and Leonard sit “eating our own broad beans—delicious.” There are more local intrigues: the coal from the cellar goes missing, a mysterious plague kills the farmer’s lambs. Day by day, she watches a caterpillar pupate. The news is better from France. Still, the German prisoners work in the fields. “When alone, I smile at the tall German.” But her entries are thinning. By September, there is “nothing to notice” on the Downs, or “nothing new.” Even the butterflies are less brilliant—a few tortoiseshells, some ragged blues. Finally, toward the back of the notebook, she lists the household linen to be washed.

Her attention had begun shifting elsewhere. In London, she was becoming intensely preoccupied with the Press, and with writing shorter things, impressions and color studies—the pieces that will make up her first book of stories, Monday or Tuesday, published in 1921. And yet, if one looks closely, one can see the diary in some of these stories; something like an underpainting.

Take, for instance, Katherine Mansfield’s visit to Asheham in August 1917. The diary’s summary of Katherine’s visit is brief: her train into Lewes was late, so Woolf bought a bulb for the flowerbed; later, the two writers walked on the terrace together, an airship maneuvering overhead. Yet from letters, we know that the manuscript for Woolf’s “Kew Gardens” was almost certainly brought out. In it, we can see the imprint of Asheham, its reversal of scales, its teeming insect life. In the story, which was published in 1919, human life takes place off center, in the murmur of conversation wafting above the flower bed, while the “vast green spaces” of the bed and the snail laboring over his crumbs of earth loom largest of all. The story, though set in Richmond, captures the atmosphere of Asheham. Its form, like the other stories in Monday or Tuesday, owes much to the episodic structure of her diary, in which impressions are hazy, words come and go, and attention is both microscopic and abstract. And its authorial presence mirrors the one we find in the notebook—a writer who is both there and not there, looking and noticing.

Toward the end of 1918, as Woolf’s convalescence comes to an end, so does her Asheham diary. Back in London, she muses on the project she has kept going for two years: “Asheham diary drains off my meticulous observations of flowers, clouds, beetles & the price of eggs,” she writes in her other, longer diary, “&, being alone, there is no other event to record.” It has served its purpose, paving a way back to writing after illness, of nursing her attention back to life. Though it was later forgotten, it always stood for one of her quietest and arguably most important periods, between her first attempts at writing and those fleeting experiments which determined the novels that came afterward. And it continued to be a storehouse for images to be drawn upon later—her nephews, Julian and Quentin Bell, carrying home antlers, like those in the attic nursery in To The Lighthouse; a grass snake on the path, like the one Giles Oliver crushes with his tennis shoe in Between the Acts; a continuous stream of butterflies and moths.

0 notes

Text

471 of 2022

The Letter V (True or False)

Created by joybucket

You've voted in a presidential election. 🗳 (my country is a kingdom)

You like the name Veronica.

You've met someone named Veronica.

You've worn a sun visor.

You've watched the Nickelodeon show Victorious.

...and you like Victoria Justice.

You've taken voice lessons.

You've watched The Voice. 🎤

You like vineyard music. 🎶

You can play the violin. 🎻 (no, but I wish)

You enjoy listening to violin music. 🎻

You've never been to Venezuela. 🇻🇪

You've driven a van. 🚐

You like the name Victoria.

You've met someone named Victoria. (it’s my cat)

You went to school with a Vanessa.

You like to read vampire novels. 🧛♀️

You've dressed up as a vampire for Halloween. 🧛♀️

You've had a friend named Vicky.

You remember learning about Vincent Van Gogh in school.

....and you like some of Van Gogh's paintings. 🖼

You like violets.

You've been to Vermont.

You've been to Virginia.

You've been to West Virginia.

You're a vegetarian. 🥬

You're vegan. 🥗

You like the view outside your living room window.

You've worn a vest at some point within the last week.

You own a vest.

You own a varsity jacket.

You've earned a varsity letter.

You've played a sport on a varsity team.

You've wanted to become a vet. 🩺 🦮

You enjoy learning new vocabulary words.

There is a vase of flowers in the room you're in right now. 🏺💐

You've played volleyball on a team. 🏐

You read the Sweet Valley High books when you were younger. 📚

You've used velum on a scrapbook page.

You drive a vehicle. 🚘

You think Vonda sounds like a good name for an evil villain.

You like Grace VanderWaal. 🎶

You like the name Valencia.

You celebrate Valentine's Day. 💝

You've met someone with the last name Valentine.

You own a Versace robe. 👘

You've never been to Venice, Italy. 🇮🇹

You know what book series Voldemort is from.

You've practiced voodoo.

You've dressed up like Darth Vader.

You've been bitten by a venomous insect. 🐝

You've worn a wedding veil. 👰♀️

You're married, but you didn't wear a veil.

You're not married, and you want to wear a veil when you get married.

You'd rather wear a flower crown than a veil.

You've drank Vernor's.

You've been told you have a beautiful voice.

You've driven down a Verona Road.

You've pole vaulted.

You're married, and you wrote your own wedding vows.

You're not married, but you want to write your own weddings vows when you get married.

You're a Virgo. ♍️

Your heater vents are very dusty.

You own something that uses velcro.

You own a vinyl record.

You've had a VIP pass to an event.

You like to wear vintage clothing.

You've met someone named Vance.

You've experienced vertigo. 😵 💫

You've heard some horrible things about Venezuela. 🇻🇪

....but you've also heard some really good things about it.

You just back from a vacation. 🧳

You're planning to go on vacation soon.

You wish you were about to go on a vacation.

You've ridden a roller coaster with a vertical drop. 🎢

You've had a phone from Verizon.

You've driven a Saturn Vue. 🚗

You take daily vitamins.

You've owned a Windows Vista computer. 💻

There is a military veteran in your family.

You've volunteered at a homeless shelter.

You like to dress in vibrant colors.

You have a Vogue subscription. 💃

Whenever you get blood drawn, they always have a hard time finding your vein. 🩸 (they’re very visible, but apparebtly very small)

You've been told you have teeny tiny veins.

You like the song lyrics, "You're so vain, I bet you think this song is about you..."

You've posted a vague status on Facebook.

....and someone got mad at you for it.

....which is why you made it vague in the first place; you wouldn't want to share every detail of your life and then have someone critique you or judge you for it.

You've passed out valentines to everyone in your class. 💌

You've been valedictorian of your class.

You vape.

You used to vape, but now you don't.

You remember the commercials that said, "verb. it's what you do."

You've used the vomit emoji. 🤮

Thankfully, it's been awhile since you've vomited. 🤮

You've vomited recently.

You've been released from the hospital when you felt horrible, because the doctor or nurse said, "Your vitals are normal."

You like Vitamin Water.

You have a very vivid imagination.

You like to have the volume on your music turned up loud.

You used voluming shampoo. 🧴

You're very vulnerable (i.e., capable of being wounded or hurt).

....and you've put up walls to protect yourself because of it.

You hate vultures.

You enjoyed this survey.

You love Victorian homes.

You think living in the Victorian Era sounds very pleasant and lovely.

0 notes

Text

The Letter V (True or False) by joybucket

You’ve voted in a presidential election. 🗳

You like the name Veronica.

You’ve met someone named Veronica.

You’ve worn a sun visor.

You’ve watched the Nickelodeon show Victorious.

…and you like Victoria Justice.

You’ve taken voice lessons.

You’ve watched The Voice. 🎤

You like vineyard music. 🎶

You can play the violin. 🎻

You enjoy listening to violin music. 🎻

You’ve never been to Venezuela. 🇻🇪

You’ve driven a van. 🚐

You like the name Victoria.

You’ve met someone named Victoria.

You went to school with a Vanessa.

You like to read vampire novels. 🧛♀️

You’ve dressed up as a vampire for Halloween. 🧛♀️

You’ve had a friend named Vicky.

You remember learning about Vincent Van Gogh in school.

….and you like some of Van Gogh’s paintings. 🖼

You like violets.

You’ve been to Vermont.

You’ve been to Virginia.

You’ve been to West Virginia.

You’re a vegetarian. 🥬

You’re vegan. 🥗

You like the view outside your living room window.

You’ve worn a vest at some point within the last week.

You own a vest.

You own a varsity jacket.

You’ve earned a varsity letter.

You’ve played a sport on a varsity team.

You’ve wanted to become a vet. 🩺 🦮

You enjoy learning new vocabulary words.

There is a vase of flowers in the room you’re in right now. 🏺💐

You’ve played volleyball on a team. 🏐

You read the Sweet Valley High books when you were younger. 📚

You’ve used velum on a scrapbook page.

You drive a vehicle. 🚘

You think Vonda sounds like a good name for an evil villain.

You like Grace VanderWaal. 🎶

You like the name Valencia.

You celebrate Valentine’s Day. 💝

You’ve met someone with the last name Valentine.

You own a Versace robe. 👘

You’ve never been to Venice, Italy. 🇮🇹

You know what book series Voldemort is from.

You’ve practiced voodoo.

You’ve dressed up like Darth Vader.

You’ve been bitten by a venomous insect. 🐝

You’ve worn a wedding veil. 👰♀️

You’re married, but you didn’t wear a veil.

You’re not married, and you want to wear a veil when you get married.

You’d rather wear a flower crown than a veil.

You’ve drank Vernor’s.

You’ve been told you have a beautiful voice.

You’ve driven down a Verona Road.

You’ve pole vaulted.

You’re married, and you wrote your own wedding vows.

You’re not married, but you want to write your own weddings vows when you get married.

You’re a Virgo. ♍️

Your heater vents are very dusty.

You own something that uses velcro.

You own a vinyl record.

You’ve had a VIP pass to an event.

You like to wear vintage clothing.

You’ve met someone named Vance.

You’ve experienced vertigo. 😵 💫

You’ve heard some horrible things about Venezuela. 🇻🇪

….but you’ve also heard some really good things about it.

You just back from a vacation. 🧳

You’re planning to go on vacation soon.

You wish you were about to go on a vacation.

You’ve ridden a roller coaster with a vertical drop. 🎢

You’ve had a phone from Verizon.

You’ve driven a Saturn Vue. 🚗

You take daily vitamins.

You’ve owned a Windows Vista computer. 💻

There is a military veteran in your family.

You’ve volunteered at a homeless shelter.

You like to dress in vibrant colors.

You have a Vogue subscription. 💃

Whenever you get blood drawn, they always have a hard time finding your vein. 🩸

You’ve been told you have teeny tiny veins.

You like the song lyrics, “You’re so vain, I bet you think this song is about you…”

You’ve posted a vague status on Facebook.

….and someone got mad at you for it.

….which is why you made it vague in the first place; you wouldn’t want to share every detail of your life and then have someone critique you or judge you for it.

You’ve passed out valentines to everyone in your class. 💌

You’ve been valedictorian of your class.

You vape.

You used to vape, but now you don’t.

You remember the commercials that said, “verb. it’s what you do.”

You’ve used the vomit emoji. 🤮

Thankfully, it’s been awhile since you’ve vomited. 🤮

You’ve vomited recently.

You’ve been released from the hospital when you felt horrible, because the doctor or nurse said, “Your vitals are normal.”

You like Vitamin Water.

You have a very vivid imagination.

You like to have the volume on your music turned up loud.

You used voluming shampoo. 🧴

You’re very vulnerable (i.e., capable of being wounded or hurt).

….and you’ve put up walls to protect yourself because of it.

You hate vultures.

You enjoyed this survey.

You love Victorian homes.

You think living in the Victorian Era sounds very pleasant and lovely.

0 notes

Text

The Letter V (True or False) by joybucket

You've voted in a presidential election. 🗳

You like the name Veronica.

You've met someone named Veronica.

You've worn a sun visor.

You've watched the Nickelodeon show Victorious.

...and you like Victoria Justice.

You've taken voice lessons.

You've watched The Voice. 🎤

You like vineyard music. 🎶

You can play the violin. 🎻

You enjoy listening to violin music. 🎻

You've never been to Venezuela. 🇻🇪

You've driven a van. 🚐

You like the name Victoria.

You've met someone named Victoria.

You went to school with a Vanessa.

You like to read vampire novels. 🧛♀️

You've dressed up as a vampire for Halloween. 🧛♀️

You've had a friend named Vicky.

You remember learning about Vincent Van Gogh in school.

....and you like some of Van Gogh's paintings. 🖼

You like violets.

You've been to Vermont.

You've been to Virginia.

You've been to West Virginia.

You're a vegetarian. 🥬

You're vegan. 🥗

You like the view outside your living room window.

You've worn a vest at some point within the last week.

You own a vest.

You own a varsity jacket.

You've earned a varsity letter.

You've played a sport on a varsity team.

You've wanted to become a vet. 🩺 🦮

You enjoy learning new vocabulary words.

There is a vase of flowers in the room you're in right now. 🏺💐

You've played volleyball on a team. 🏐

You read the Sweet Valley High books when you were younger. 📚

You've used velum on a scrapbook page.

You drive a vehicle. 🚘

You think Vonda sounds like a good name for an evil villain.

You like Grace VanderWaal. 🎶

You like the name Valencia.

You celebrate Valentine's Day. 💝

You've met someone with the last name Valentine.

You own a Versace robe. 👘

You've never been to Venice, Italy. 🇮🇹

You know what book series Voldemort is from.

You've practiced voodoo.

You've dressed up like Darth Vader.

You've been bitten by a venomous insect. 🐝

You've worn a wedding veil. 👰♀️

You're married, but you didn't wear a veil.

You're not married, and you want to wear a veil when you get married.

You'd rather wear a flower crown than a veil.

You've drank Vernor's.

You've been told you have a beautiful voice.

You've driven down a Verona Road.

You've pole vaulted.

You're married, and you wrote your own wedding vows.

You're not married, but you want to write your own weddings vows when you get married.

You're a Virgo. ♍️

Your heater vents are very dusty.

You own something that uses velcro.

You own a vinyl record.

You've had a VIP pass to an event.

You like to wear vintage clothing.

You've met someone named Vance.

You've experienced vertigo. 😵 💫

You've heard some horrible things about Venezuela. 🇻🇪

....but you've also heard some really good things about it.

You just back from a vacation. 🧳

You're planning to go on vacation soon.

You wish you were about to go on a vacation.

You've ridden a roller coaster with a vertical drop. 🎢

You've had a phone from Verizon.

You've driven a Saturn Vue. 🚗

You take daily vitamins.

You've owned a Windows Vista computer. 💻

There is a military veteran in your family.

You've volunteered at a homeless shelter.

You like to dress in vibrant colors.

You have a Vogue subscription. 💃

Whenever you get blood drawn, they always have a hard time finding your vein. 🩸

You've been told you have teeny tiny veins.

You like the song lyrics, "You're so vain, I bet you think this song is about you..."

You've posted a vague status on Facebook.

....and someone got mad at you for it.

....which is why you made it vague in the first place; you wouldn't want to share every detail of your life and then have someone critique you or judge you for it.

You've passed out valentines to everyone in your class. 💌

You've been valedictorian of your class.

You vape.

You used to vape, but now you don't.

You remember the commercials that said, "verb. it's what you do."

You've used the vomit emoji. 🤮

Thankfully, it's been awhile since you've vomited. 🤮

You've vomited recently.

You've been released from the hospital when you felt horrible, because the doctor or nurse said, "Your vitals are normal."

You like Vitamin Water.

You have a very vivid imagination.

You like to have the volume on your music turned up loud.

You used voluming shampoo. 🧴

You're very vulnerable (i.e., capable of being wounded or hurt).

....and you've put up walls to protect yourself because of it.

You hate vultures.

You enjoyed this survey.

You love Victorian homes.

You think living in the Victorian Era sounds very pleasant and lovely.

0 notes

Text

@rosieposiepie tagged me in this book ask game!!

bought: I am one of those nerds who goes to a local comic shop at least once a month, so all of my most recent buys are comics . . . most recently I bought the first trade paperback of Nice House on the Lake (which was SO GOOD), the latest Saga, and the first issue of Eat the Rich (which has completely sucked me in). Oh, and the first issue of Primordial, which I haven’t read yet

borrowed: The last book I borrowed from the library was Artimesia, a graphic novel biography of Artemisia Gentileschi, and before that it was My Dark Vanessa (the first book on this list that is NOT a comic)

was gifted: My mom (an english teacher), gifted me the book Wonder Works, about the history of different symbols in literature! And a few months ago a good friend gave me If It Bleeds, a short story collection by Stephen King

gave/lent: I gave my friend in Virginia Crush by Richard Siken as a thanks-for-letting-me-stay-at-your-place gift last time I was there! Before that, I gave my roommate a couple graphic novels for their birthday and my mom a Mary Oliver collection for Christmas

finished: oh god, of books not already mentioned? For non-comics, I read Let the Right One In back at the begining of this year, and it was an Excellent journey. In terms of comics, I read every issue of The Me You Love In the Dark as it was coming out last year, and I looooooved it

started: Axiom’s End by Lindsey Ellis!! I need to get back to reading it; I have a tendency to read a billion things at once so it’s been, like, Actual Months

5 stars: Okay OKAY let’s go, rapidfire - Are You My Mother? by Alison Bechdel, This One Summer by Mariko and JIllian Tamaki, Exhalation by Ted Chiang, Sorrowland by Rivers Solomon

2 stars: hrmmmmmm . . . god, this is tricky. I can’t think of anything I’ve read recently that I would rate that low, tbh

didn’t finish: The Overstory . . . I know, I know, but the part one just hit so hard as a short story collection for me that it felt like the rest of it dropped off for me

I’m tagging @bi-guy-sci-fi bc he’s the one who told me to read Let the Right One In - your turn, tell me boooooks

1 note

·

View note

Photo

He says the simple things that clever people don't say; I find him the best of critics for that reason.

- Virginia Woolf on E.M. Forster in her private diaries

Although historians disagree on who was part of the “in crowd” and who was not (there was never an official list), many agree that among the founding individuals were Clive Bell, Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, and especially E.M. Forster who carved out an academic life at Cambridge alongside his novel writing.

Several of the men were educated together at Cambridge where they met Thoby Stephen and his siblings: Adrian, Vanessa (later Bell), and Virginia (later Woolf). The Stephens began to host regular but informal gatherings at their residence in the Bloomsbury neighborhood of London. These “Friday Club” and “Thursday Evening” meetings were the soil out of which the Bloomsbury Group grew. Thoby’s early death in 1906 brought the group of friends closer together and spurred them onward.

Other members were Desmond Macarthy, Arthur Waley, Saxon Sidney-Turner, Robert Trevelyan, Francis Birrell, J.T. Sheppard (later provost of King’s College), and the critic Raymond Mortimer and the sculptor Stephen Tomlin, both Oxford men. Bertrand Russell, Aldous Huxley, and T.S. Eliot were sometimes associated with the group, as was the economist Gerald Shove.

The group survived World War I but by the early 1930s had ceased to exist in its original form, having by that time merged with the general intellectual life of London, Oxford, and Cambridge. Although its members shared certain ideas and values, the Bloomsbury group did not constitute a school. Its significance lies in the extraordinary number of talented persons associated with it.

**E.M. Forster in his college rooms at Kings College, Cambridge.

#woolf#virginia woolf#quote#em forster#forster#literature#culture#aesthetics#bloomsbury#cambridge#university#society#england#britain#history

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hii, do you have any recommendations for fantasy or dark academia books?

Why yessss.

First off, let’s cover our bases. I feel like there’s a good chance you’ve already read (or at least heard of) most of the titles that belong to the Dark Academia Starter Pack. But, just in case, here's a list of modern novels that seem to have helped inspire the Dark Academia trend.

Starter Pack:

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

If We Were Villains by M.L. Rio

Vicious by V.E. Schwab

Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo

Bunny by Mona Awad

A Deadly Education by Naomi Novak (I personally disagree with this--would even go so far as to encourage you to avoid Naomi Novak on account of personal bias due to my loathing for all of her works--still, I’ve seen this book quoted often enough and the subject matter is relevant to our theme.)

To this largely agreed upon/already popular list, I would personally add:

Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy

The Idiot by Edith Batuman

Normal People by Sally Rooney

My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab

Moving forward, let’s cover some subdivisions. In my mind, Dark Academia is a broad theme. In fact, I feel as though any book that combines an appreciation for the arts (usually centered around the pursuit of self discovery) and a whiff of the dramatic qualifies. Pick your own vibe.

Folklore & Fairy Tale Vibes:

My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales by Kate Bernheimer

Transformations by Anne Sexton

Apple & Knife by Intan Paramaditha

The Complete Fairy Tales by George MacDonald

Hag: Forgotten Folk Tales Retold by Daisy Johnson

The Fairy Books (any color, my favorite was always Crimson) by Andrew Lang

Spooky + Dreamy Surrelist Vibes:

Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders by Vítězslav Nezval

Rebbeca by Daphne Du Maurier

Other Voices, Other Rooms by Truman Capote

Mr. Fox by Helen Oyeyemi

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides (Light on the academic theme, but the writing here more than compensates.)

The Auteur OR Just Try to Make A Good Movie Out of My Elaborate Word Salad, I Dare You Vibes:

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

White Oleander by Janet Fitch

The Waves by Virginia Woolf

Truly Dysfunctional With a Side of Occasional Batshittery Vibes:

Prozac Nation by Elizabeth Wurtzel

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

The Pisces by Melissa Broder

Sisters by Daisy Johnson

Treasure Island!!! by Sara Levine

Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson

Classical Mythology Vibes:

Mythology by Edith Hamilton

The Roman Way by Edith Hamilton

The Greek Way by Edith Hamilton

Circe by Madeline Miller

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (ONLY SORT OF fits the classical mythology theme, but is an amazing novel either way)

GOTHIC! Vibes:

Don Juan by Lord Byron

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

Johnathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke

Frankenstein by Mary Shelly

The Unsuitable by Molly Pohlig

Dracula by Bram Stoker

I’d also be happy to delve deeper into any category/cater more to any personal interests you may have if you’d like!

149 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Biographical Fiction ft. Complex Characters: Book Recs

More Miracle Than Bird by Alice Miller

On the eve of World War I, twenty-one-year-old Georgie Hyde-Lees—on her own for the first time—is introduced to the acclaimed poet W. B. Yeats at a soirée in London. Although Yeats is famously eccentric and many years her senior, Georgie is drawn to him, and when he extends a cryptic invitation to a secret society, her life is forever changed.

A shadow falls over London as zeppelins stalk overhead and bombs bloom against the skyline. Amidst the chaos, Georgie finds purpose tending to injured soldiers in a makeshift hospital, befriending the wounded and heartbroken Lieutenant Pike, who might need more from her than she is able to give. At night with Yeats, she escapes these realities into an even darker world, becoming immersed in The Order, a clandestine society where ritual, magic, and the conjuring of spirits is practiced and pursued. As forces—both of this world and the next—pull Yeats and Georgie closer together and then apart again, Georgie uncovers a secret that threatens to undo it all.

Vanessa and Her Sister by Priya Parmar

London, 1905: The city is alight with change, and the Stephen siblings are at the forefront. Vanessa, Virginia, Thoby, and Adrian are leaving behind their childhood home and taking a house in the leafy heart of avant-garde Bloomsbury. There they bring together a glittering circle of bright, outrageous artistic friends who will grow into legend and come to be known as the Bloomsbury Group. And at the center of this charmed circle are the devoted, gifted sisters: Vanessa, the painter, and Virginia, the writer.

Each member of the group will go on to earn fame and success, but so far Vanessa Bell has never sold a painting. Virginia Woolf’s book review has just been turned down by The Times. Lytton Strachey has not published anything. E. M. Forster has finished his first novel but does not like the title. Leonard Woolf is still a civil servant in Ceylon, and John Maynard Keynes is looking for a job. Together, this sparkling coterie of artists and intellectuals throw away convention and embrace the wild freedom of being young, single bohemians in London.

But the landscape shifts when Vanessa unexpectedly falls in love and her sister feels dangerously abandoned. Eerily possessive, charismatic, manipulative, and brilliant, Virginia has always lived in the shelter of Vanessa’s constant attention and encouragement. Without it, she careens toward self-destruction and madness. As tragedy and betrayal threaten to destroy the family, Vanessa must decide if it is finally time to protect her own happiness above all else.

Twain & Stanley Enter Paradise by Oscar Hijuelos

Hijuelos was fascinated by the Twain-Stanley connection and eventually began researching and writing a novel that used the scant historical record of their relationship as a starting point for a more detailed fictional account. It was a labor of love for Hijuelos, who worked on the project for more than ten years, publishing other novels along the way but always returning to Twain and Stanley; indeed, he was still revising the manuscript the day before his sudden passing in 2013.

The resulting novel is a richly woven tapestry of people and events that is unique among the author's works, both in theme and structure. Hijuelos ingeniously blends correspondence, memoir, and third-person omniscience to explore the intersection of these Victorian giants in a long vanished world.

From their early days as journalists in the American West, to their admiration and support of each other's writing, their mutual hatred of slavery, their social life together in the dazzling literary circles of the period, and even a mysterious journey to Cuba to search for Stanley's adoptive father, TWAIN & STANLEY ENTER PARADISE superbly channels two vibrant but very different figures. It is also a study of Twain's complex bond with Mrs. Stanley, the bohemian portrait artist Dorothy Tennant, who introduces Twain and his wife to the world of séances and mediums after the tragic death of their daughter.

A compelling and deeply felt historical fantasia that utilizes the full range of Hijuelos' gifts, TWAIN & STANLEY ENTER PARADISE stands as an unforgettable coda to a brilliant writing career.

The Personal Librarian by Marie Benedict, Victoria Christopher Murray

In her twenties, Belle da Costa Greene is hired by J. P. Morgan to curate a collection of rare manuscripts, books, and artwork for his newly built Pierpont Morgan Library. Belle becomes a fixture on the New York society scene and one of the most powerful people in the art and book world, known for her impeccable taste and shrewd negotiating for critical works as she helps build a world-class collection.

But Belle has a secret, one she must protect at all costs. She was born not Belle da Costa Greene but Belle Marion Greener. She is the daughter of Richard Greener, the first Black graduate of Harvard and a well-known advocate for equality. Belle's complexion isn't dark because of her alleged Portuguese heritage that lets her pass as white--her complexion is dark because she is African American.

The Personal Librarian tells the story of an extraordinary woman, famous for her intellect, style, and wit, and shares the lengths to which she must go--for the protection of her family and her legacy--to preserve her carefully crafted white identity in the racist world in which she lives.

#historical fiction#Historical Reads#historical#biographical fiction#complex characters#plot#to read#tbr#Book Recommendations#reading recommendations#library books#book club pick#book club#booklr#book tumblr#books to read

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a young Virginia Woolf scribbled her first stories—precursors to her groundbreaking novels, now considered Modernist classics—her elder sister, Vanessa Bell, could be found quietly sketching or searching for clay in the garden of their London home. In her diary, Woolf remembers her sister’s early passion for art: “Once I saw her scrawl on a black door a great maze of lines, with white chalk. ‘When I am a famous painter—’ she began, and then turned shy and rubbed it out in her capable way.”

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

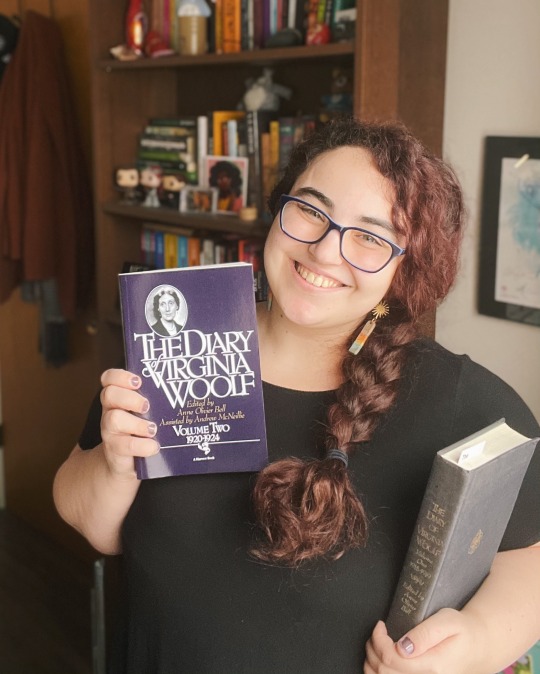

I have spent the past week or so reading the first two volumes of The Diary of Virginia Woolf, annotating, underlining, and enjoying myself thoroughly.

It’s most difficult to get started: Volume One can be tough in that you first have to grasp the cast of characters. Virginia obviously doesn’t introduce her diary to each friend; you are left to do some searching online to understand the context and history behind dramas and attachments. The footnotes specify things like that “Morgan” is EM Forster, for example, but often fail to provide necessary context—such as, Vanessa and Clive are married, but Vanessa is with the bisexual Duncan and Clive is with Mary.

But once you understand the cast, Woolf’s friend group is wildly fascinating—their open and polyamorous relationships, romantic and queer entanglements and break-ups, tangled web of drama, snubs, and critiques, all of it is a riot to read and uncover. Her deep friendship with Lytton, her tumultuous one with Clive, the rivalry with Katherine Mansfield that is both intensely loving and a source of never-ending conflict—they’re all so well expressed, and intensely felt.

Over the course of these two journals, Woolf grows more comfortable with her diary and shifts into the poetic voice that makes her diary so reflective and distinct, so rich with story-telling. She is dry and witty—her backhanded compliments and savage insults wrecked me several times. She writes of “taking my fences”—her determination to always strive, push, work, and takes this as the meaning of her life, and always pushes others to take risks and pursue work and happiness. She is charged by critique of her novels, as it reminds her that she writes for herself and no one else. We enter the realm of Mrs Dalloway. Virginia falls into ‘headaches,’ bouts of depression and anxiety that she can scarcely recognize when they’re over.

Woolf’s diaries are vivid, engaging, and thought-provoking, and I was engaged throughout. Several times I wanted to reach through and speak to her—when she mentions, for example, while writing Mrs Dalloway, that critics accuse her of failing to make characters who last—or when she wonders if her novels are actually good or to be remembered. Excited for the rest of these volumes.

#virginia woolf#the diary of virginia woolf#class literature#nonfiction books#virginia woolf books#all mine#my book reviews

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WhatsOnStage reports that online audiobook and podcast provider Audible will be exclusively releasing new readings of four Virginia Woolfs works with an all-star cast. Vanessa Kirby is set to perform part of Woolfs dreamscape novel The Wave, alongside Adetomiwa Edun, Andrea Riseborough, Tracy Ifeachor, Samuel Barnett, Johnny Flynn and Juliet Stevenson. All readings will be released on March 8 (International Woman’s Day) and available to download via Audible.

9 notes

·

View notes