#women maternity

Text

Even though it's been months since I switched from neurosurgery to internal medicine, I still have a hard time not being angry about the training culture and particularly the sexism of neurosurgery. It wasn't the whole reason I switched, but truthfully it was a significant part of my decision.

I quickly got worn out by constantly being questioned over my family plans. Within minutes of meeting me, attendings and residents felt comfortable lecturing me on the difficulties of having children as a neurosurgeon. One attending even suggested I should ask my co-residents' permission before getting pregnant so as not to inconvenience them. I do not have children and have never indicated if I plan to have any. Truthfully, I do want children, but I would absolutely have foregone that to be a neurosurgeon. I wanted to be a neurosurgeon more than anything. But I was never asked: it was simply assumed that I would want to be a mother first. Purely because I'm a woman, my ambitions were constantly undermined, assumed to be lesser than those of my male peers. Women must want families, therefore women must be less committed. It was inconceivable that I might put my career first. It was impossible to disprove this assumption: what could I have done to demonstrate my commitment more than what I had already done by leading the interest group, taking a research year, doing a sub-I? My interest in neurosurgery would never be viewed the same way my male peers' was, no matter what I did. I would never be viewed as a neurosurgeon in the same way my male peers would be, because I, first and foremost, would be a mother. It turns out women don't even need to have children to be a mother: it is what you essentially are. You can't be allowed to pursue things that might interfere with your potential motherhood.

Furthermore, you are not trusted to know your own ambitions or what might interfere with your motherhood. I am an adult woman who has gone to medical school: I am well aware of what is required in reproduction, pregnancy, and residency, as much as one can be without experiencing it firsthand. And yet, it was always assumed that I had somehow shown up to a neurosurgery sub-I totally ignorant of the demands of the career and of pregnancy. I needed to be enlightened: always by men, often by childless men. Apparently, it was implausible that I could evaluate the situation on my own and come to a decision. I also couldn't be trusted to know what I wanted: if I said I wanted to be a neurosurgeon more than a mother, I was immediately reassured I could still have a family (an interesting flip from the dire warnings issued not five minutes earlier in the conversation). People could not understand my point, which was that I didn't care. I couldn't mean that, because women are fundamentally mothers. I needed to be guided back to my true role.

Because everyone was so confident in their sexist assumptions that I was less committed, I was not offered the same training, guidance, or opportunities as the men. I didn't have projects thrown my way, I didn't get check-ins or advice on my application process, I didn't get opportunities in the OR that my male peers got, I didn't get taught. I once went two whole days on my sub-I without anyone saying a word to me. I would come to work, avoid the senior resident I was warned hated trainees, figure out which OR to go to on my own, scrub in, watch a surgery in complete silence without even the opportunity to cut a knot, then move to the next surgery. How could I possibly become a surgeon in that environment? And this is all to say nothing of the rape jokes, the advice that the best way for a woman to match is to be as hot as possible, listening to my attending advise the male med students on how to get laid, etc.

At a certain point, it became clear it would be incredibly difficult for me to become a neurosurgeon. I wouldn't get research or leadership opportunities, I wouldn't get teaching or feedback, I wouldn't get mentorship, and I wouldn't get respect. I would have to fight tooth and nail for every single piece of my training, and the prospect was just exhausting. Especially when I also really enjoyed internal medicine, where absolutely none of this was happening and I even had attendings telling me I would be good at it (something that didn't happen in neurosurgery until I quit).

I've been told I should get over this, but I don't know how to. I don't know how to stop being mad about how thoroughly sidelined I was for being female. I don't know how to stop being bitter that my intelligence, commitment, and work ethic meant so much less because I'm a woman. I know I made the right decision to switch to internal medicine, and it probably would have been the right decision even if there weren't all these issues with the culture of neurosurgery, but I'm still so angry about how it happened.

#I would love to do something about this but I have no idea how to#even the faculty that I do really admire and respect seem entrenched in some of these attitudes#it's really hard to convince people that women aren't traitors in the making#simply because we might get pregnant one day and need time off#oh I also heard people shittalking a resident that was on maternity leave#and saying she wasn't serious about neurosurgery#so it's just inevitable#I'm not the only female student that feels this way btw#there's a reason no women have applied to nsgy from my school in years#sexism#neurosurgery#surgery#medicine#medical school#med school#med student#medblr#my content#my text posts

777 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh Baby - Mayternity

“Have a kiddie pool ready at my baby shower. I have a feeling my water will break in the middle of the party.” Kellie teased waddling past her guests to go into the kitchen. She grabs a tray of cookies to bring outside; placing a cookie or three in her salivating mouth. Her bestie calls for her from outside, making Kellie turn quickly. Her massive belly knocks over several bottles of water like a bowling ball hitting the pins for a strike. Kellie stands there looking at the bottles on the floor with a defeated expression upon her face. Her mother walks into the room chuckling and gently rubs her daughter’s belly.

“I got this dear, Denise is calling for you outside.” Mother starts to pick up the water bottles off the floor.

Kellie waddles outside, feeling extreme heaviness on her bladder. She approaches Denise to see what she called her outside for.

“Someone sent these flowers for you. He didn’t say his name, but he’s a tall, dark and handsome man.” Denise smiles handing her the bouquet.

“They’re so lovely, he could have stayed if he wanted.” Kellie blushing as she knows whom it was that sent the flowers. She takes the flowers and smells them. They smell sweet and fresh from the floral shop. Kellie began to think about that night with him. It was all a blur, but she remembers how she gotten pregnant. His strong arms held her up on the kitchen counter of her place, the room smelled of cookies baking in the oven releasing more endorphins. Her hormones were all over the place that night.

Kellie sneezes abruptly followed by a sudden gush between her thick thighs. Kellie gasps as her water has just broken and her hunch was right. It’s happening now!

tinylf.com/ieJxgq8t

#dress ups#belly love#fake belly#loyalfans#maternity#pregblr#pregnant#pretend pregnant#cute belly#expecting#big for babies#heavy belly#huge pregnant belly#big pregnant belly#pregnant with triplets#fake pregnant belly#pregnantbelly#preggie#pregnant women#preg#pregnancy#pregnant kink#preggoalways#preggo kink#preggophilia#super preggo#preg k!nk#plus size preggo#so pregnant#Preg story

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

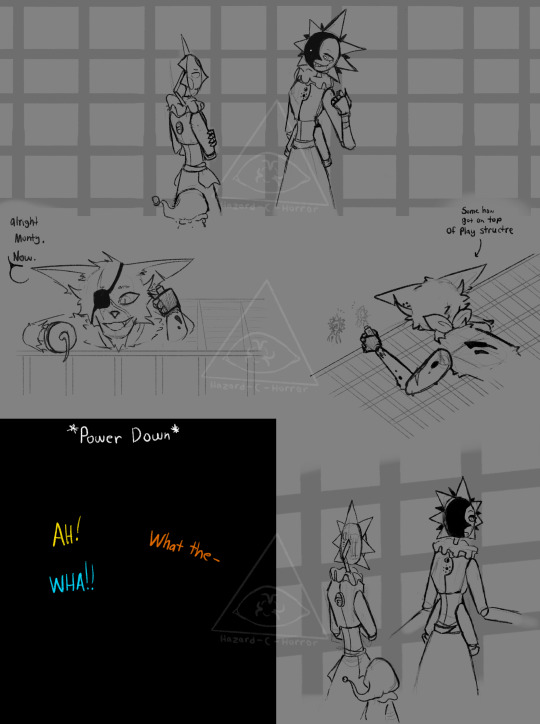

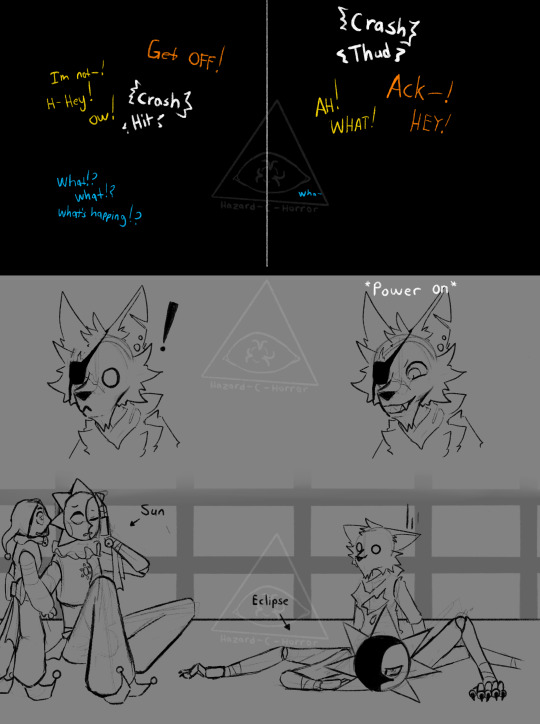

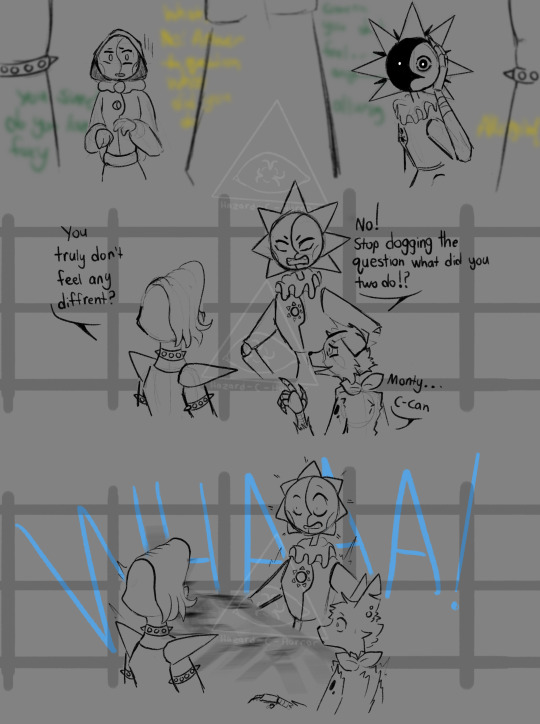

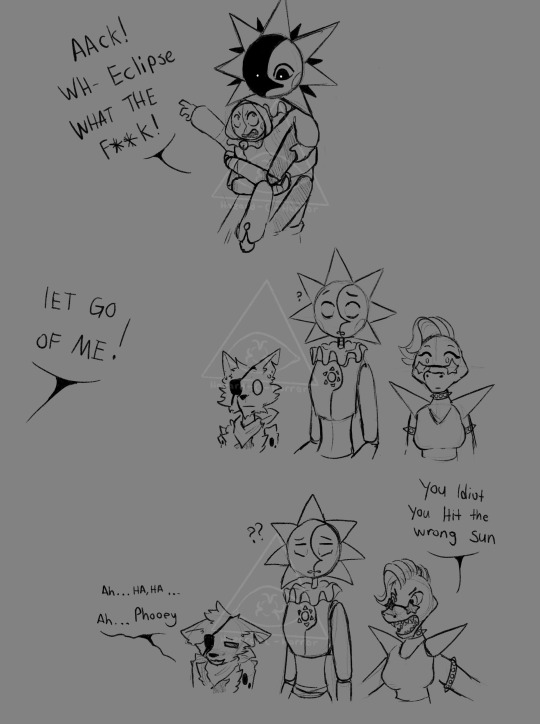

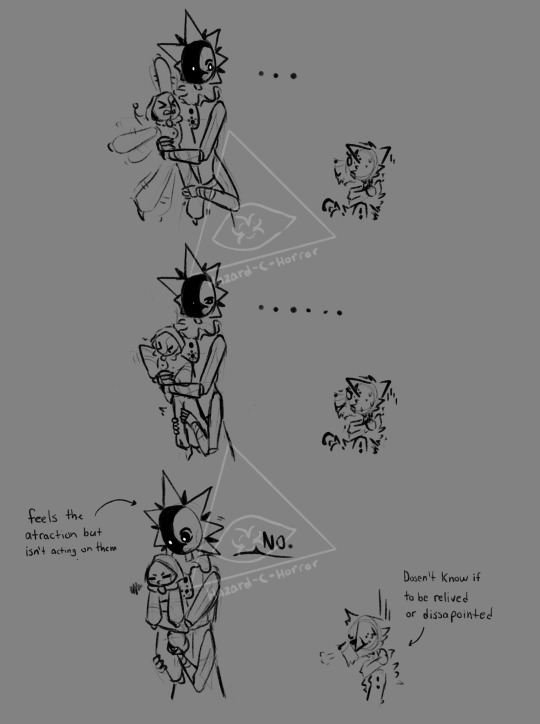

Maternity Chip Eclipse Au

so I had two ideas for how Eclipse got the chip stuck in his head. And then asked the TSBS discord which one would be better

and so I made a comic

read right to left

Monty: Uh, we were going to put a maternity chip into you

Sun: …

Sun & Lunar: WHY!?

You can consider this part2

#I need to practice drawing women#sun and moon show#eclipse sams#sams eclipse#the sun and moon show#tsams#eclipse tsams#tsams eclipse#lunar laes#lunar sams#sun and moon show au#sams au#tsams au#tsams lunar#sams lunar#lunar and earth show#laes lunar#the monty and foxy show#monty and foxy show#mafs foxy#mafs monty#monty gator and foxy show#maternity chip eclipse#maternity chip eclipse au#my art

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love how kinda shit Tina is with kids it's incredible to me. like she thinks the eggs are adorable and fawns all over them but when it comes to like practical stuff she slips up a lot and freaks about the responsibility. When she's unprepared she's super awkward like when she first met em she spent most of her time overthinking and panicking. Or during the date when Richas started playing pretend with her and Bagi, Bagi adapted pretty quick but Tina had some trouble playing along. And she's hyper aware of to. Shes very insecure about her parenting abilities and swears up and down that her first meeting with Empanda was a garbage fire. She is, however, determined to do better. Shes actively trying to become a better parent and is holding herself to it. I just really like that she's not immediately settling into being a mother. Not everyone immediately acclimates to parenthood and it fits super well for her character.

#it just CTINE GYAHHHH#shes super duper insecure and cctina plays it so well#no way the woman who files down her horns and lies constantly abt her identity bcs of how ashamed of it she is would immediately be#the 'perfect mother'#not to mention the expectation for women being that their 'maternal instincts' kick in immediately and make up for any character flaws#and the expectation for mother to become their primary identity#IDUNNO i love her complexities shes babygirl 2 mr#<*2 me#tinakitten#q!tina#qsmp tag#smp analysis

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctors and nurses who are not willing to listen to their patients should be replaced

BY VICTORIA SMITH

The third time I went into labour, I was determined to avoid getting told off. With both of my previous births, I had somehow managed to get things wrong. My errors the first time: going to hospital too early, then, when I returned three hours later, “leaving it so late”. The second time: ignoring assurances that I didn’t need to come in yet, then giving birth in the car park — an event I later discovered was being used in antenatal classes as an example of women “not planning ahead”.

“My previous births have been fast,” I said, when I went into labour with my third, “so I’d like to come in now.” I was speaking to the woman at the midwife-led unit that is the only option where I live. (If you need a caesarean section, you have to be transferred to next town.) “Third babies are notoriously difficult,” was her response.

What an odd thing to say to a woman already in labour. The “notoriously” suggested it wasn’t based on any actual evidence, but rather a kind of folk wisdom. It felt as though I was being warned not to tempt fate, not to assume that this baby would just pop out. I saw myself being categorised as one of those arrogant women who presumes to know her own body, only to be taught a harsh yet much-deserved lesson. “Third babies are notoriously difficult” sounded not unlike “third-time mothers shouldn’t get above themselves”.

In fact, I have never been particularly cocky about childbirth. When I was pregnant with my first child, back in the days when the Right-wing press were still obsessed with famous women being “too posh to push”, I wondered if I might be able to get an elective caesarean myself. I did not particularly care about childbirth being a wonderful experience, or about “doing it well”. I didn’t care if the Daily Mail thought I was a joke.

What I cared about was not having a child who would face the same difficulties as my brother, who was starved of oxygen at birth. This has had serious consequences for him, and for the rest of my family. Just how serious is hard to gauge. He was born traumatised; there has never been a before to compare the after with. What there has been instead is the hazy outline of an alternative life, one that runs parallel to the one he has now. It’s a life that began with the problem being identified sooner, with him being delivered quickly, perhaps by emergency caesarean. The difference between this and his actual life comes down to something small: mere moments, mere breaths.

I was born three years after my brother, in a larger hospital, where my mother was induced and monitored carefully. There is something very strange about being the sibling who had the safe birth. It feels as though I stole it. There is a constant sense of guilt, as if my life — my independence, my choices — constitutes a form of gloating. “This is what you could have had.” Everything I do feels like something owed to my brother (do it, because he can’t) but also something taken from him (you shouldn’t have done that, because he should have done it first).

Still, my family were fortunate, insofar as my brother didn’t die. Current reports on the Nottingham maternity scandal reference 1,700 cases, with an estimated 201 mothers and babies who might have survived had they received better care. What strikes me, reading them, is the enormous gulf between the cost of a disastrous birth and the trivial, opportunistic way in which childbirth is so often politicised — with mothers themselves viewed as morally, if not practically, to blame if anything goes wrong.

As a feminist who concerns herself with how the female body is demonised, my interest in debates about birthing choices is more than personal. I have read books railing against the over-medicalisation of childbirth, aligning it with a patriarchal need to appropriate female reproductive power. I have also read books protesting the fetishisation of “natural” birth, suggesting that it infantilises women, that it implies women deserve pain. To be honest, I find both arguments persuasive and dismaying. Both are right about the way in which misogyny and professional arrogance can shift the focus away from meeting the needs of women and babies. I feel a kind of rage that we are told to pick a side.

Representations of the labouring woman are so often negative: the naïve idealist, the “birthzilla“, the birth-plan obsessive, the woman who is “too posh to push”. This latter stereotype has gone hand-in-hand with a veneration of vaginal births, and stigmatisation of caesareans, that has had sometimes disastrous consequences. Midwives at the centre of the Furness General Hospital scandal were reported to have “pursued natural birth ‘at any cost’”, referring to one another as “the musketeers”; at least 11 babies and one mother died. But their approach was sanctioned by their employer: the 2006 NHS document “Pathways to Success: a self-improvement toolkit” explicitly suggested that “maternity units applying best practice to the management of pregnancy, labour and birth will achieve a [caesarean section] rate consistently below 20% and will have aspirations to reduce that rate to 15%”. Proposed benefits to this included “a sense of pride in units”.

Responses to maternity scandals now express horror that such an anti-intervention culture ever arose — responses in the same press that denigrated women such as Victoria Beckham and Kate Winslet for not giving birth vaginally. Instead, newspapers now stoke outrage over “natural” treatments during NHS births, such as burning herbs. Women have been shamed for having caesareans, but they have also been shamed for wanting births with minimum intervention — as though they are selfish and spoilt for seeking control over such an extreme situation.

In his memoir This Is Going To Hurt, former doctor Adam Kay writes disparagingly of women who arrive at the delivery suite with birth plans:

“‘Having a birth plan’ always strikes me as akin to having a ‘what I want the weather to be’ plan or a ‘winning the lottery’ plan. Two centuries of obstetricians have found no way of predicting the course of a labour, but a certain denomination of floaty-dressed mother seems to think she can manage it easily.”

Wanting to have some control over your experience of labour — which will hurt you and could kill you or your baby — is not akin to some messianic aspiration to control the weather. And in his mockery of the woman who wants whale song and aromatherapy oils, ironically, Kay deploys the same silencing techniques that might intimidate a woman out of seeking the very interventions he so prizes. What he and others do not seem to grasp is that their arrogance is a problem, regardless of which course of action they champion. It makes women feel they can’t speak, for fear of inviting hostility at their most vulnerable moments. It’s true that none of us knows our body well enough to know how we will give birth. But, looking back, I find it utterly insane, not least given my own family history, that one of my biggest worries during labour was “please don’t let anyone get cross with me”. Then again, I don’t think that fear is unrelated to the desire to remain safe.

Birth is not a joke. It is not a place for professional dick-swinging or political one-upmanship. I cannot describe — and, as I am not my mother, cannot fully understand — the shame of feeling that you “let down” your child before they drew their first breath, that they will forever suffer because of it. You watch an entire life unfolding and that feeling is there, every single day. This is the fear of the women in labour who are characterised as either idiots mesmerised by fantasy homebirths or cold-hearted posh ladies who can’t take the pain. If things go wrong, they are the ones who will bear the consequences, reflecting every day on what might have been, if they’d only done more.

When people discuss their siblings, my mind does wander to the one I don’t have, the one who was born safely. Perhaps he would have a job he loved, or one he hated, but in any case a job. Perhaps he would have a partner. Perhaps he would have children, and I would be their aunt. Perhaps we wouldn’t get on, wouldn’t even speak, but he’d have a life of his own. I know he thinks about this too. I wonder if the professionals who presided over his birth have thought about him since.

My third labour was not, by the way, “notoriously difficult”. My third son arrived into the world safe and well. No one can say why him or me, and not my brother. Mothers may long for control over birth, for which we are mocked; but we do not have it, for which we are blamed. Politics still takes precedence over our needs, and the needs of our babies.

#Traumatic births#Doctors not listening to women#There's no such thing as a birthzilla#Women aren't too posh to push#Doctors are so posh they schedule cesareans to accommodate their schedules not the mothers#Furness General Hospital Scandal#This is going to hurt#Keep Adam Kay away from women#Women wanting a say in their births are not acting like they want to control the weather#Nottingham maternity scandal#If the baby suffers during a traumatic birth it's the mother who will providing the care after they come home from the hospital

549 notes

·

View notes

Text

My maternity shoot you guys 🤍 I’m so thankful for this new journey. I can’t wait to meet you

Instagram : @alanicekarele

#black women#blacklove#blackcouple#black excellence#pregnancy#pregnant#babyontheway#maternity#maternity shoot#maternité#african#blacklivesmatter#black ouftit#pregnancy announcement#luxury#black girl moodboard#black women in luxury#blackgirl#black girls are beautiful

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

1908-1912 Maternity silk mourning dress

(Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery)

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

#big pregnant belly#pregnant women#pregnantgril#twin pregnancy#preg kink#huge pregnant belly#super preggo#maternity

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝑯𝒂𝒍𝒍𝒆 𝑩𝒂𝒊𝒍𝒆𝒚'𝒔 𝑼𝒏𝒅𝒆𝒓𝒘𝒂𝒕𝒆𝒓 𝑴𝒂𝒕𝒆𝒓𝒏𝒊𝒕𝒚 𝑷𝒉𝒐𝒕𝒐𝒔𝒉𝒐𝒐𝒕

#halle bailey#melanin#black women#beauty#the little mermaid#maternity photoshoot#2024#my post#dailywoc#dailymusicians#dailymusicqueens#femalepopculture#popularcultures#userzonez#usermusic#userwocs

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

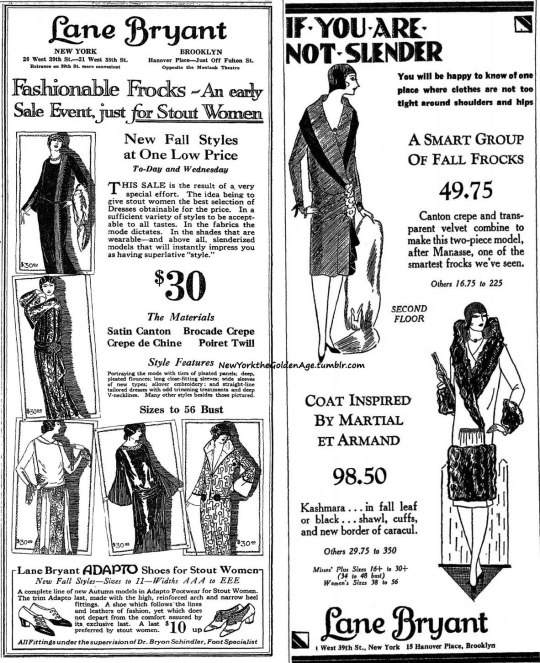

Lane Bryant was founded in New York in 1904 as a shop for standard-sized women. When a pregnant customer asked the proprietor, Lena Bryant (the bank officer who opened her account had misspelled her name), to make a "presentable but comfortable" dress for her, it was the first commercially available maternity dress.

When measuring her customers, Bryant realized the need for clothing for those who needed larger sizes than those usually available. So she began to stock them, and the first "plus size" clothing was available. Business boomed. It became a chain, which now has 448 stores in 46 states.

The ad on the left appeared in the NY Times in 1923 and the one on the right in 1925. I like the line, "If you are not slender." Better than "stout" or "plus sized."

Source: NY Times

#vintage New York#1920s#Lane Bryant#plus sized clothing#vintage clothing#shops#stores#women's clothing#maternity wear#female business owners#women in business

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hoppy Easter darlings 🐣💜

I’d be a fool to wait until tomorrow 🤭

https://tinylf.com/kDOflfxq2hXC

#dress ups#belly love#fake belly#loyalfans#maternity#pretend pregnant#pregnant#pregnant women#pregnant kink#pregblr#pregnantbelly#cute belly#bump#expecting

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maternity Chip Eclipse Au

so I guess I have an Au now…

Since this is based on a small bit at the very beginning of “The Monty and Foxy Show gets Shutdown” episode. Monty and Foxy made this maternity chip

for the kidscove clickbait, but now they got some new material

#I don’t know how to draw women#sun and moon show#the sun and moon show#eclipse sams#sams eclipse#eclipse tsams#tsams#tsams eclipse#sams au#tsams au#sun and moon show au#tsams lunar#lunar sams#sams lunar#lunar laes#the monty and foxy show#monty and foxy show#monty gator and foxy show#maternity chip eclipse#maternity chip eclipse au#my art

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ryan Adamczeski at The Advocate:

The majority of Black women of reproductive age in the United States live in areas that restrict access to abortion, a new report has found.

Out of the 11.8 million Black women between the ages of 15 and 49, 57 percent (6.7 million) have little to no abortion access, according to a study from the National Partnership for Women & Families (NPWF) and In Our Own Voice.

Of the Black women in states that prohibit abortion, 43 percent live in just three states — Florida, Georgia, and Texas. 2.7 million are already “economically insecure” and 1.4 million work service jobs where wages are lower and sick days are not mandatory.

"Nearly two years later, the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade continues to significantly harm millions of people across the nation, impeding their access to abortion, disrupting their economic futures, and putting their health and even their lives at risk," the report states. "The impact of this decision is particularly harmful for women of color, who are less likely to have access to high-quality, culturally competent health care and face greater economic barriers to getting abortion care."

The report noted that "abortion bans and the harms caused by Dobbs are especially egregious in light of this country’s ongoing maternal health crisis." Black women and birthing people are three times more likely to die in childbirth as compared to white women and birthing people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to a study conducted jointly between National Partnership for Women and Families and In Our Own Voice, a majority of Black women of reproductive age live in areas that don’t have access to abortion services.

The 2022 Dobbs ruling exacerbated those harms even further.

See Also:

HuffPost: Report Shows How The Fall Of Roe Will Hit Millions Of Black Women

#Abortion Access#Maternity#Abortion#Black Women#Reproductive Health#Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization#Roe v. Wade#Abortion Bans#In Our Own Voice#National Partnership For Women and Families#Economic Inequality

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Business Class

#ai art#stable diffusion#pregnancy art#pregnant art#fake photo#pregnant beauty#maternity art#AI girls#AI generated#AI waifus#Working Women

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wealthiest Black Moms More Likely To Die In Childbirth Than Poorest White Moms

Here, in the only industrialized country where overall maternal mortality is rising, Black women remain between three and four times more likely than their white or Hispanic counterparts to die from pregnancy-related complications. And although Black women suffer above-average rates of pregnancy-related complications such as preeclampsia, uterine fibroids, and preterm birth, they’re also less likely to have access to quality care, creating a double-edged sword with compounding factors on both sides. A new study finds that even the wealthiest Black women are unable to escape this harm.

756 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jasmine Tookes is expecting her first child with husband Juan David Borrero

876 notes

·

View notes