#yankee to confederate

Text

#us politics#american civil war#fuck the confederacy#fuck the confederates#confederate states of america#confederate flag#a confederacy of dunces#traitors#treason#memes#shitpost#rebellion#yankee candle

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Confederate and Union Veteran at the 1938 Gettysburg reunion exchanging stories. Original photo from The Gettysburg Museum Of History archives. www.GettysvburgMuseumOfHistory.com

#1938GettysburgReunion#american civil war#north and south#Yankees and Confederates#GettysburgMuseumOfHistory#1938

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stand Watie was A Native American Brig General for the CSA. He was the last general to surrender. He remembered the treatment of the Federals during the trail of tears and he vowed to punish them.

#civil war#fuck the yankees#gettysburg#southerners#states rights#history#confederate#gravestones#robert e lee#confederacy#cherokee

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Southern food tournament is making me realize I no longer have access to half or more of my biggest comfort foods (at least, not cooked properly) and I haven't had any of them in years and this is the one and only motivation I have ever had to actually learn how to cook. I need to make my own hushpuppies and okra if I ever want them again

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

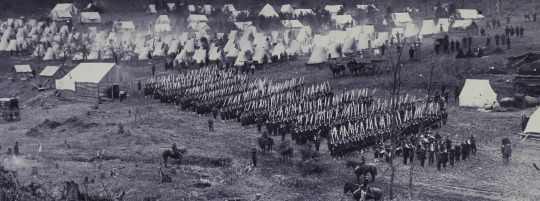

Cobb County in the Atlanta Campaign | American Battlefield Trust

#history#future#Cobb County Georgia#civil war#confederacy#confederate states#union states#Yankees#Rebels#Southern#Northern#march towards Atlanta

0 notes

Text

Confederate General Joseph Wheeler volunteered to fight in the Spanish-American War, and received appointment to Major General by President William McKinley. The former rebel, in his sixties and thirty years since last commanding troops, was now second-in-command of Fifth Army Corps. Under his command was fought the first major engagement of the war, the Battle of Las Guasimas…

… during which Wheeler, in a moment of excitement, yelled out “Let’s go, boys! We’ve got the damn Yankees on the run again!”

wrong… wrong war, joe

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dallas and Sylvia argue about politics when they wanna piss each other off can’t find anything else to fight about

“AT LEAST I CAN ACTUALLY NAME ALL THE STATES THIS SIDE OF THE MASON DIXON-,”

“SORRY BABE, CAN’T HEAR YOU OVER THE FACT THAT YOU LOST-,”

“Yankee bitch.”

“Confederate hick.”

#dillo’s replies#sophie i guess13#disregard the fact that oklahoma was not a part of the confederacy#but dallas doesn’t know that#he’s dumb <3

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

April 12, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

APR 13, 2024

At 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, a federal fort built on an artificial island in Charleston Harbor.

Attacking the fort seemed a logical outcome of events that had been in play for at least four months. On December 20, 1860, as soon as it was clear Abraham Lincoln had won the 1860 presidential election, South Carolina lawmakers had taken their state out of the Union. “The whole town [of Charleston] was in an uproar,” Elizabeth Allston recalled. “Parades, shouting, firecrackers, bells ringing, cannon on the forts booming, flags waving, and excited people thronging the streets.”

Mississippi had followed suit on January 9, 1861; Florida on January 10; Alabama on January 11; Georgia on January 19; Louisiana on January 26; and Texas on February 1. By the time Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, seven southern states had left the Union and formed their own provisional government that protected human enslavement.

Their move had come because the elite enslavers who controlled those southern states believed that Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860 itself marked the end of their way of life. Badly outnumbered by the northerners who insisted that the West must be reserved for free men, southern elites were afraid that northerners would bottle up enslavement in the South and gradually whittle away at it. Those boundaries would mean that white southerners would soon be outnumbered by the Black Americans they enslaved, putting not only their economy but also their very lives at risk.

To defend their system, elite southern enslavers rewrote American democracy. They insisted that the government of the United States of America envisioned by the Founders who wrote the Declaration of Independence had a fatal flaw: it declared that all men were created equal. In contrast, the southern enslavers were openly embracing the reality that some people were better than others and had the right to rule.

They looked around at their great wealth—the European masters hanging in their parlors, the fine dresses in which they clothed their wives and daughters, and the imported olive oil on their tables—and concluded they were the ones who had figured out the true plan for human society. As South Carolina senator James Henry Hammond explained to his colleagues in March 1858, the “harmonious…and prosperous” system of the South worked precisely because a few wealthy men ruled over a larger class with “a low order of intellect and but little skill.” Hammond dismissed “as ridiculously absurd” the idea that “all men are born equal.”

On March 21, 1861, Georgia’s Alexander Stephens, the newly-elected vice president of the Confederacy, explained to a crowd that the Confederate government rested on the “great truth” that the Black man “is not equal to the white man; that…subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” Stephens told listeners that the Confederate government “is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

Not every white southerner thought secession from the United States was a good idea. Especially as the winter wore into spring and Lincoln made no effort to attack the South, conservative leaders urged their hot-headed neighbors to slow down. But for decades, southerners had marinated in rhetoric about their strength and independence from the federal government, and as Senator Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana later wrote, “[t]he prudent and conservative men South,” were not “able to stem the wild torrent of passion which is carrying everything before it…. It is a revolution...of the most intense character…and it can no more be checked by human effort, for the time, than a prairie fire by a gardener’s watering pot.”

Southern white elites celebrated the idea of a new nation, one they dominated, convinced that the despised Yankees would never fight. “So far as civil war is concerned,” one Atlanta newspaper wrote in January 1861, “we have no fears of that in Atlanta.” White southerners boasted that “a lady’s thimble will hold all the blood that will be shed” in establishing a new nation. Senator James Chesnut of South Carolina went so far as to vow that he would drink all the blood shed as a consequence of southern secession.

Chesnut’s promise misread the situation. Northerners recognized that if Americans accepted the principle that some men were better than others, and permitted southern Democrats to spread that principle by destroying the United States, they had lost democracy. "I should like to know, if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle, and making exceptions to it, where will it stop?” Lincoln had asked in 1858.

Northerners rejected the white southerners’ radical attempt to destroy the principles of the Declaration of Independence. They understood that it was not just Black rights at stake. Arguments like that of Stephens, that some men were better than others, “are the arguments that kings have made for enslaving the people in all ages of the world,” Lincoln said. “You will find that all the arguments in favor of king-craft were of this class; they always bestrode the necks of the people, not that they wanted to do it, but because the people were better off for being ridden…. Turn in whatever way you will—whether it come from the mouth of a King, an excuse for enslaving the people of his country, or from the mouth of men of one race as a reason for enslaving the men of another race, it is all the same old serpent….”

Northerners rejected the slaveholders’ unequal view of the world, seeing it as a radical reworking of the nation’s founding principles. After the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, Lincoln called for 75,000 to put down the rebellion against the government. He called for “loyal citizens to favor, facilitate, and aid this effort to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular government; and to redress wrongs already long enough endured.”

Like their southern counterparts, northerners also dismissed the idea that a civil war would be bloody. They were so convinced that a single battle would bring southerners to their senses that inhabitants of Washington, D.C., as well as congressmen and their wives packed picnics and took carriages out to Manassas, Virginia, to watch the Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. They decamped in panic as the battle turned against the United States army and soldiers bolted past them, flinging haversacks and rifles as they fled.

For their part, southerners were as shocked by the battle as the people of the North were. “Never have I conceived,” one South Carolina soldier wrote, “of such a continuous, rushing hailstorm of shot, shell, and musketry as fell around and among us for hours together. We who escaped are constantly wondering how we could possibly have come out of the action alive.”

Over the next four years, the Civil War would take more than 620,000 lives and cost the United States more than $5 billion. By 1865, two-thirds of the assessed value of southern wealth had evaporated; two-fifths of the livestock— horses and draft animals for tilling fields as well as pigs and sheep for food— were dead. Over half the region's farm machinery had been destroyed, most factories were burned, and railroads were gone, either destroyed or worn out. But by the end of the conflagration, the institution of human enslavement as the central labor system for the American South was destroyed.

On March 4, 1865, when a weary Lincoln took the oath of office for a second time, he reviewed the war’s history. “To strengthen, perpetuate and extend [slavery] was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it,” he said. “Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph and a result less fundamental and astounding.

“Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered—that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.”

“Both parties deprecated war but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish,” he said.

“And the war came.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#American Civil War#Heather Cox Richardson#Letters From Am American#racism#created equal#equality#Fort Sumpter#The South#income inequality#American's DNA

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw a rightist meme on the Book of Faces (the Book of Faces keeps showing me groups like that, probably in part because I'm in a group that mocks Right memes, which the algorithm apparently thinks means I must actually unironically want to see those kinds of memes) with a picture of Robert E Lee and I'm presuming his family with "Happy Thanksgiving" on it

What makes this hilarious is that Thanksgiving was not celebrated in the Confederacy. At the time, it was largely seen in the South as a Yankee holiday. It had originated in New England, and while it had started to spread to the south in the 1830s and 1840s, it began to lose popularity in the 1850s, in part because many Northern preachers used it as an occasion to give abolitionist sermons, and thus came to be seen as a pro-Abolitionist holiday (along with the rising sectionalism in general that made anything "Yankee" unpopular in the South). By the Civil War, it had pretty much disappeared from the South, especially among Lee's class. It didn't really begin to be fully adopted by the South until the post-Reconstruction era

So it's pretty hilarious that some pro-Confederate decided to associate Lee with a holiday that he would surely have hated to be associated with

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apparently before there was a War On Christmas, there was a War Of Thanksgiving. (The Civil War. It was the Civil War.)

Although meant to unify people, the 19th-century campaign to make Thanksgiving a permanent holiday was seen by prominent Southerners as a culture war. They considered it a Northern holiday intended to force New England values on the rest of the country. To them, pumpkin pie, a Yankee food, was a deviously sweet symbol of anti-slavery sentiment.

...

Southern leaders attacked Thanksgiving as the North’s attempt to impart Yankee values on the South. Virginians, especially, retaliated against Hale’s campaign. In 1856, the Richmond Whig published a scathing editorial on the District of Columbia’s “repugnant” declaration of thanksgiving, arguing that the holiday did nothing but rob men of a day’s wages and encourage drunkenness. As for the Northerners who started the celebration: “They have crazy society within New England’s limits, where they have been productive of little but mischief—of unadulterated and unmistakable injuries to sound religion, morals, and patriotism.”

A few years later, according to historian Melanie Kirkpatrick, Governor Wise of Virginia answered letters from Hale by telling her he wanted nothing to do with “this theatrical national claptrap of Thanksgiving, which has aided other causes in setting thousands of pulpits to preaching ‘Christian politics.’” Wise’s statement directly referred to anti-slavery politics.

...

In Texas, Governor Oran Milo Roberts, a former Confederate army officer, refused to declare Thanksgiving a holiday as late as the 1880s. Some Southern governors would follow the annual presidential proclamations, but move the date of Thanksgiving to resist its message of national unity.

#happy thanksgiving#american thanksgiving#would it really be an american holiday without partisan squabbling

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Captain Confederate is GOD!!

“Damn straight, Yant. Now, come worship your god. I won’t hurt ya…long as ya do a good job.”

“You can do a good job worshippin me, can’t ya, lil Yankee? You said I’m yer god and let’s face it, I deserve to be worshipped by Yankees like you.”

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

“I don’t have much personal experience with international travel, but my intuitive guess for why Americans would lead with their state is because a lot of Americans fucking hate each other and don’t want to be mistaken as being from one of THOSE states.” Want some cheap malicious fun? Call a White US Southerner with a prickly sense of regional identity (Confederate flag regalia are a useful marker) a Yankee. (An immediate exit strategy is recommended.)

--

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

Mad hatter and King of Hearts and you tell me who you want to tell me about. :)

(from the An OC's Adventures in Canonland ask game)

Mad Hatter: How would the story be different if they weren't around?

A little corner of Edward's brain still blames Margaret Weiss for his slippery slope in 1927. She was a delicious nobody, just a girl who sat next to him in Biology. Not a singer, but some people really do smell better than others. Edward got a little... studious about Margaret's scent during a time of adolescent moral upheaval and it soon devolved into having fantasies about killing her. He very nearly did kill her on his way out of town, but fortunately Charles Evenson popped into his head and the whole thing became more heroic from that moment on. To this day, Edward thinks "If she hadn't been around, maybe those thoughts would have come and gone without incident."

They would not have. Edward needed those rebellious years, so they were going to happen no matter what.

King of Hearts: How are they most likely to die (If already dead, how did they die?)

When death came up, I immediately consulted my list of red shirt OCs. Let's talk about Sergeant Lockewood! He was in Jasper's Confederate regiment, the Texas Fifth Cavalry, and the one who accompanied him on the evacuation mission to Houston. This poor guy was never going to amount to much, but at least he was superstitious enough to take the vampire rumors seriously. Jasper laughed in his face.

Lockewood didn't get a Yankee bullet like the others. The cause of death was, you guessed it, Jasper. (I haven't written this one yet.)

#inbox#wow apparently I never gave Lockewood a first name??#eh *shrugs* red shirt#for non-Trekkies that means he was invented solely for the purpose of being dispensable#OC: Margaret Weiss#OC: _____ Lockewood#Edward#Jasper#ask game

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The US Springfield Rifle 1861 - .58 caliber was one of the most produced and utilized small arms during the war. Even Rebels used it when we found one or requisitioned Yankee small arms. Credit: Passing Through by Don Stivers during the capture of Carlisle, PA

#springfield#civil war#american civil war#southerners#confederate#states rights#damn yankees#robert e lee#history#gunshot#virginia#confederacy#gravestones#alabama

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your thoughts on James Longstreet? He was a Confederate commander, and so fought to preserve slavery, but he was also one of the few among the Confederate senior officers who supported the Reconstruction.

So Longstreet is a fascinating case of pesonal character growth. Pretty much through the war he was a very conventional Southern officer in his attitudes to slavery; he owned slaves, he was very open that the Confederacy's cause was "protecting and defending lawful property," infamously in 1862, he gave this speech to rally his men against the enemy:

He told his men that the Yankees were determined to seize Southern land and property; as proof, he cited “one of their great leaders [who has] attempted to make the negro your equal by declaring his freedom. They care not for the blood of babes nor carnage of innocent women which servile insurrection thus stirred up may bring upon their heads.” (source)

That's a pretty straightforward invocation of the specter of slave revolts and the rape of white women which were the hallmarks of pro-slavery mobilization of public opinion in Southern society, the original blood libel against black emancipation.

But to give him credit, James Longstreet was also one of the few high-ranking Confederates who really took the idea of Reconstruction seriously on a personal level and sought to educate and grow from his experiences. As he said in a letter to the newspaper after the war:

"The great principles that divided political parties prior to the war were thoroughly discussed by our wisest statement...appeal was finally made tot the sword, to determine which of the claims was the true construction of constitutional law. The sword has decided in favor of the North, and what they claimed as principles cease to be principles, and are become law. The views that we hold cease to be principles cease to be principles because they are are opposed to the law. It is therefore our duty to abandon ideaas that are obsolete and conform to the requirements of law."

As a philosophical and political position, It's weirdly militaristic and oddly Hegelian, but Longstreet goes on to explicitly state that black suffrage and full citizenship should be adopted throughout the South. This letter destroyed his reputation among white Southernors, but Longstreet put his money where his mouth was, becoming a Republican and a railroad executive, and a general in the Louisiana state militia leading black troops against white supremacist paramilitaries.

He was an imperfect man, but I think you have to give him credit for consistently applying his beliefs, being willing to follow reason and logic even if it required a complete renunciation of his former beliefs, and following through with thorough action in furtherance of his new principles.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Southern women zealously supported the southern cause of independence. A Georgia woman wrote her local newspaper, ‘I feel a new life within me, and my ambition aims at nothing higher than to become an ingenious, economical, industrious housekeeper, and an independent Southern woman.’ Throughout the South, women urged their menfolk to enlist in the Confederate military. A Selma, Alabama, woman even broke off her engagement when her fiance failed to enlist. She sent him a skirt and pantaloons with a note attached: ‘Wear these or volunteer.’

Up North, women also showed passionate support--for the Union. Shortly after the war began, Louisa May Alcott, who later wrote the novel Little Women, confided in her diary, ‘I long to be a man; but as I can’t fight, I will content myself with working for those who can.’ Harriet Beecher Stowe called the Union effort a ‘cause to die for,’ and a woman in New York declared, ‘It seems as if we never were alive till now; never had a country till now.’ As their husbands and sons drilled and marched and prepared for battle in opposing armies, women of the North and South swung into action.

…Women also took over the work of men who had gone off to fight. Across the North and South, women took charge of family farms and plantations as their men battled in Antietam or Chancellorsville or Gettysburg--or lay languishing in makeshift army hospitals or military prisons. Some women despaired at the enormous responsibilities of planting, plowing, and running a farm, but other women met the challenge head on--and discovered new strengths and abilities in the process. Sarah Morgan of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, marveled at how much she accomplished in one day--’empty a dirty hearth, dust, move heavy weights, make myself generally useful and dirty, and all this thanks to the Yankees.’

Throughout the North, scores of women worked in government offices for the first time to replace male clerks who had enlisted in the Union army. They worked as clerks and copyists, copying speeches and documents for government records. They also became postal employees and worked in the Treasury Department cutting apart long sheets of paper money and counting currency. Salaries ranged from $500 to $900 a year by 1865. Although this was more than what most female employees made at the time, women still earned half of what men earned for the same work.

…As the Union armies advanced deeper into the South, capturing Confederate territory and liberating slaves in the process, hundreds of black and white women, mostly in their 20s, followed closely behind to teach the former slaves, many of whom were illiterate. Women risked danger and hardship--and sometimes their families’ disapproval--to venture South. They went under the auspices of American Missionary Society, the Pennsylvania Freedmen’s Relief Association, and other agencies that recruited teachers and paid their monthly wages of $10 to $12.

Teachers admired their students’ eagerness to learn. ‘It is a great happiness to teach them,’ Charlotte Forten, a black woman who taught in the Sea Islands off of South Carolina, wrote a friend in November 1862. ‘I wish some of those persons at the North who say the race is hopelessly and naturally inferior, could see the readiness with which these children, so long oppressed and deprived of every privilege, learn and understand.’ Adult ex-slaves, too, were willing students. Of one of her grown-up students, Forten remarked, ‘I never saw anyone so determined to learn.’

…About 400 women disguised themselves as Union or Confederate soldiers and fought in the war. With the proper attire, some could easily pass for being a man. Women enlisted for a variety of reasons--some believed in the cause so deeply that they would not let being a woman stop them from fighting as soldiers. Others craved adventure or could not bear to be apart from husbands or other loved ones who had joined the army. No doubt some women were killed in battle and went to their graves with their true identities concealed.

Other women soldiers were forced to reveal their secret when they were wounded. A female Union soldier, wounded in the battle of Chickamauga in Tennessee, was captured by Confederate troops and returned to the Union side with a note: ‘As the Confederates do not use women in the war, this woman, wounded in battle, is returned to you.’ When a Union nurse asked her why she had joined the army, she replied, ‘I thought I’d like camp life, and I did.’

…In 1863, women in New York City went on a rampage. In the South, women had rioted for food; in New York, they joined men, mostly Irish, who were protesting against a federal provision that allowed draftees to hire substitutes. The protest quickly erupted into a riot against the city’s blacks. The protestors, who feared competition from black workers, resented being drafted to fight a war for the slave’s freedom. Even more so, they resented upper-class Yankee Protestants who could afford to pay substitutes $300 to fight in their places.

Over four days, rioters looted stores and beat innocent blacks. Angry mobs lynched about six blacks, destroyed the dwellings where blacks lived, and burned down the Colored Orphan Asylum. They also set fire to several businesses that employed blacks and destroyed the homes of prominent Republicans and abolitionists. Women took part in the plunder, venting their rage at a government and a war that sacrificed their men and impoverished their lives.”

- Harriet Sigerman, “‘I Am Needed Here’: Women at War.” in An Unfinished Battle: American Women, 1848-1865

#harriet sigerman#history#american civil war#american#1860s#19th century#gender#an unfinished battle

7 notes

·

View notes