#my biology unit this week was bones can you tell

Note

Happy WBW! In honor of the pain bestowed upon me by the Blood Goddess 🙃, what is your world like in relation to sicknesses, injuries, and other afflictions? Feel free to discuss the medical system or how jobs/institutions respond, or even how individual characters feel!

First of all, my deepest condolences for your life rn. That's the worst.

And thank you for the question! Within SolCorp, it's the Pluto Department that is in charge of all medical care ranging from pediatric, general preventative care, trauma medicine, and mental healthcare.

Pluto agents are pretty dang busy on a daily basis. Sol offices are practically closed systems with the majority folks leaving the campus maybe once a week so all that recirculated air means that when a cold hits, everyone gets it. Pluto (Dakota del Sol) refers to LAHQ as a plague ship (affectionate) (sort of).

A lot of healthcare provided by Sol is what you'd expect of modern medicine. Some of it, not. Biological manipulators are recruited to work in Pluto for their ability to alter someone's biology, down to their cells. There is too much risk to use bio manips for every single medical problem but when agents are gravely injured in the field or there's a serious issue, bio manips can reknit bones, close gunshot wounds, remove cancers, heal organs, etc. And yes, this does mean people with muscle sprains will aggressively pout at the bio manips telling them to go home and rest instead of fixing them.

Those not living in a SolCorp office can travel to the closest office for care or, in emergencies, trauma units will be teleported to them. There is typically someone with basic medic training on each team to take care of everyday needs. (Hannah is the medic for Reeve's team.)

There is no charge or cost whatsoever for any of this for Sol agents. It's just part of being in Sol. Your needs are cared for.

Thanks to having an expansive employee base, agents' bosses are generally understanding of illness/injuries and are not overly pushy to get the agent back to their desk/out into the field until they're ready. (Something a certain other organization of knacked people views as supremely soft.) If you become too disabled to continue at your job, you will be moved to something you are able to do.

Also some knacks can cause medical issues all by themselves that Pluto has to manage. For example, mimics often (1 in 2) develop autoimmune issues because their body reacts to the "borrowed" knack as if it were a foreign virus to be fought. If knacks become too dangerous/harmful (I'm looking at you, radiation manips) Pluto and Venus work together to perform a Post-Breathe Gene Alteration (post-breathe for short) which can alter or remove a person's knack altogether.

All of this is nothing at all like how medical care is handled in Entropy or in The Church but...no spoilers.

#wbw#didn't mean to write a novel there but here we are#can you tell that this stuff comes up in the story?#the mimicry causing autoimmune reactions is all Tou's brilliant idea btws

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, August 16, 2023

I am sad that last week was my last week of youth group with my church friends since dance started back up. Julien is going tonight because it will be his last night as he will be at university next week.

Wednesday is always a long day, but I truly enjoy it.

Tasks Completed:

Geometry - Review writing slope-intercept equations, equations of horizontal and vertical lines, and graphing equations of lines using intercepts + practice

Lit and Comp II - Studied vocabulary + read a poem + read about plagiarism and took a quiz

Spanish 2 - Reviewed telling time, question words, use of articles, use of ser, and spelling of weather-related words

Bible I - Read Genesis 5-6

World History - Read about Ancient Mesopotamian society + read about Hammurabi's Code and a few of the laws + wrote a paragraph about the significance of the laws and its impact on other civilizations

Biology with Lab - Started an outline of notes about the characteristics of life + watched videos and read about the characteristics to take notes on the outline

Foundations - Read spiritual meanings of alertness + took a quiz on Read Theory + took a quiz on how I learn best and I discovered that my preference is multimodal with higher scores in kinesthetic and reading/writing and high scores in visual and aural

Practice - Practiced assigned pieces for 30 minutes and worked on memorization

Khan Academy - Completed Unit 1: Lesson 3 of 9th-grade reading and vocabulary

Duolingo - Completed one lesson each in Spanish, French, and Chinese

Activities of the Day:

Ballet

Variations

-

What I’m Grateful for Today:

Spending more time with Julien before he leaves for university.

Quote of the Day:

Hope can be a powerful force. Maybe there’s no actual magic in it, but when you know what you hope for most and hold it like a light within you, you can make things happen, almost like magic.

-Daughter of Smoke & Bone, Laini Taylor

🎧La valse d'Amélie (Version orchestre) - Yann Tiersen

#study community#study blog#study inspiration#study motivation#studyblr#studyblr community#study-with-aura

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who says science isn't exciting?

Episode 4x03 Subterranean homesick alien

Compared to 4x02 or even 4x01, this episode is very light on science. Also, apologies for the delay, but between exams and going back home for the holidays, I've had a very hectic week. Once again, I am not an expert in anything, just a nerd.

The two science-y bits happen at Deep Sky (can we talk about how everyone seems to just walk in and out of that place? including dead bodies). The first one is when Liz thanks Eduardo for giving her access to his machine:

"Eduardo, thank you. This machine is my favorite thing. It tests for everything: EC, pH, PO4-P. I'm about to ask it to do my taxes."

EC could mean a multitude of things, even when just looking at biology and chemistry. I will spare you all the different possible definitions and directly give you the two options that I think Liz might be referencing:

EC50: which is the half maximal effective concentration, and is a toxic unit measuring the concentration of a drug, antibody or toxicant. To put it in simpler terms, EC50 is the concentration required to reach 50% effect.

Or she could be talking about the electrical conductivity of a solution. Which, as the name indicates, represents the ability of a certain material to conduct electric current.

(The other options would not make that much sense in the context of the sentence).

I would be more inclined to believe that she is talking about EC50, especially given she talks about pH just after.

pH (potential of hydrogen) is a measure of how acidic/basic a solution is. The range goes from 0 - 14, with 7 being neutral. If the pH < 7 then the solution is acidic, and reversely if the pH>7 then it is basic.

Fun fact, but testing for pH (as far as my chemistry knowledge from high school goes) is not that hard. And I don't think it requires a special machine to do. The way we did it in high school (granted, we were not doing very complex solutions), is that we stuck a piece of pH paper into the solution, and depending on the color we had the scale of acidity.

The third thing Liz mentions is PO4-P.

PO4-P is a method of testing for phosphorus. It basically gives back the number of phosphorus (and only phosphorus, not oxygen) present in a solution.

We also know from 2x01 where Michael and Liz are dissecting Noah's body, that oasians' organs (other than bones) contain traces of organic phosphorus. I talk more about phosphorus here.

I tried finding a link between phosphorus and P2P (phenyl-2-propanone), and the closest I got was that both P2P and phosphorus can be used in creating meth (but they are both different methods, and it requires mostly red phosphorus).

So, the logical conclusion would be that the mystery component is both a derivative of P2P and of phosphorus.

Either way, we do know that alien organs have stronger traces of phosphorus than humans (hence why the little green men typically glow in the dark), and since Liz's machine can test for the presence of phosphorus, we now have an easier way to track down aliens and their environment.

(Instead of, you know, analysing someone's DNA in five minutes, as Liz often does)

The next bit of science follows in the next scene, where Liz tells Max (after having analysed all the samples in record time. Really, Deep Sky is like heaven with how fast things happen):

"Okay. All right, well, the alien plasma matches the balloons, but that's to be expected since the samples we took were from their car wheels. Usual levels of bacteria and fungi, EC is normal. Huh... High levels of petroleum hydrocarbon."

Once again I think EC is actually EC50 as I talked about earlier, since I don't think electrical current is relevant here.

And now, petroleum hydrocarbon. Max says that it's the result of oil extraction. That is correct.

Petroleum is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons.

A hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting only of hydrogen and carbon.

The thing that bothers me in that scene, which I've mentioned before, is the speed at which the science is done. I understand that actual science consists mostly of waiting and therefore isn't interesting to show on tv. But no one told them they had to do an episode / a day. If everything was simply a little more spread out, it would still make more sense.

Anyway, this is all the science for 4x03, thanks for reading, and if you have any criticism about it, feel free to reach out!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kalyani Lodhia - Visionary Explorer - A Freelance Photographer, Biologist, and Wildlife Filmmaker Uncovering Nature's Marvels.

In her own words:

“Hi! I'm Kalyani, a freelance photographer, biologist and wildlife filmmaker, born and raised in the city of Leicester, what felt like miles away from the countryside and the outdoors.

With no role-models or influences in my life to steer me to the natural world, it's a mystery to my whole family how I ended up loving the outdoors and everything in it, but somehow I did.

My love for nature fuelled me to pursue a BSc at the Royal Veterinary College where I studied a whole range of aspects of animal biology; from anatomy and physiology to behaviour and evolution. My research into kangaroo biomechanics and limb bone scaling was part of a paper published in the Royal Society Open Science in 2018. I then completed my MSc at Imperial College London, where I fell in love with science communication and story telling.

I first picked up a camera at 19 years old when my parents sent me to live in an ashram for 6 months (of course, as a teenager, I wasn't too thrilled at the prospect initially) and that's how I accidentally got into, and got hooked on, photography. I am self-taught and now specialise in travel and wildlife photography.

I love exploring the world, often travelling solo, and learning about different cultures beyond stereotypes. Having Indian heritage, I have a deep understanding of the need to look beyond imperialist and colonialist generalisations and I am able to truly connect with people around the world.

As a biologist, there's something so incredibly special about seeing the most breathtaking animals in their natural habitat and experiencing the sheer magnitude and magic of the world around us.

I have been fortunate enough to have been to the Kumbh Mela, the largest gathering of people on Earth, the forests of Finland to photograph brown bears and the depths of the South African ocean, surrounded by thousands of hammerhead sharks.

My photography work has been featured by UNICEF and the BBC and I have had the opportunity to have worked for Parmarth Niketan Ashram and Light for the World. I have also had footage featured on BBC AutumnWatch and one of my photographs was selected for the long list of the Natural History Museum's Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition. I work full time as a freelancer on science and wildlife documentaries, where I am currently working as a researcher for the BBC's Natural History Unit on a landmark natural history series for National Geographic.”

***

New episodes of the Tough Girl Podcast go live every Tuesday at 7am UK time - Hit the subscribe button so you don’t miss out.

You can support the mission to increase the amount of female role models in the media. Visit www.patreon.com/toughgirlpodcast Thank you.

***

Show notes

Who is Kalyani

Her love for the outdoors and nature

Wanting to be a vet when she was younger

Being sent to India by her parents

Accidentally getting into photography

What did her daily life look like in the Ashram

The moment when it all came together for her and started to enjoy taking photos

Going back home and doing a 3-year science degree

Still unsure what she wanted to do

Getting her Master's at Imperial Science Media Production

Working in a restaurant

How did she get her first job in The Great British Bake Off

Starting out as a runner and what she does

Taking every opportunity that is given to her

How does she cope with the stress

Her trips to other countries and what was it like for her

Her main job as a wildlife filmmaker

Working on a big series for National Geographic

Interesting place in Africa called Mauritania

Doing a shoot for three and a half weeks with a small crew

Why she's less tired than many others and her exhaustion-coping advice

Biggest challenges she's faced and had to deal with

Kalyani's trip to Iceland and why it was one of the best wildlife moments for her

Taking a trip to Finland for her birthday

Diving in the South African ocean with the hammerhead sharks

Climate change and figuring out shoot dates

The reality of nature

Where to find more information about Kalyani

Top tips and advice

Social Media

Website: www.kalyanilodhia.com

Instagram: @kalyanilodhia

Twitter: @kalyanilodhia

Check out this episode!

#podcast#women#sports#health#motivation#challenges#change#adventure#active#wellness#explore#grow#support#encourage#running#swimming#triathlon#exercise#weights

0 notes

Text

come hither, come hither, some Zukka I'll blither

The second installment in the Neurodiverse Zukka AU! In which Sokka builds a blanket fort, Zuko info-dumps, and they share some soft kisses.

#zukka#my fic#rolandtowen#mine#zuko#sokka#zuko x sokka#autistic zuko#adhd sokka#neurodiverse zukka#autism#adhd#med school au#my biology unit this week was bones can you tell#domestic fluff#zukka fluff#modern au#coffee shop au

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marine Biology Story of the Day #13: The Collection

Hey everybody, long time no see—we’ve been dealing with hurricanes and vacations and I’ve been extremely worn down from work so I have not posted anything in the last two weeks.

But, since it’s early spooky season and I’ve finally had a chance to sit down, we are going to do a special post today and go over my collection.

My collection of “dead things”, as my husband likes to describe it.

I like to describe it as my natural history collection. It’s a collection I’ve been curating since I got go college, and I have either collected and cleaned them myself, or received them as gifts from others who share my strange hobby. I have not personally killed any of these animals, however I’m sure some were road kill or were killed by barotrauma (if they were fish). Also, these are not all from dead animals, I have a large collection of molts and shells as well. For me, these are found objects, and I am giving them life again in my house. If you are uncomfortable with the idea of animal bone collection and processing, I suggest you stop here.

If you have a morbid curiosity like I do, welcome.

Lets start with the bones. On the first row we have what I think is a squirrel skull that I found on a beach (I’m not 100% sure because I don’t have any teeth from it) and a cormorant skull I found completely bleached and cleaned on a dock. On the second row we have a pair of deer antlers I spent $2 on at an antique fair, we have an otter that I cleaned for my university that I was allowed to keep, we have rocky the raccoon, also from my university, a cat skull I found on a washed up beach (there were no tags attached, no tissue left, it could have been a pet or a stray, but considering we were in the middle of nowhere, there was no way to tell), and a Atlantic sharpnose shark jaw I cleaned while on a NOAA trip. The back row we have a blacktip reef shark jaw from the same trip, and a red drum skull collected from a beach.

Now, rocky is one of my favorites—we have a long relationship. When I was in college, I took a mammalogy class and one of our assignments was to go find a dead animal and bring it in, dissect it, and clean it. Like for a grade. Our professor had tenure and was pretty eccentric, so he got away with it much to the chagrin of the president. I found rocky on the side of a highway, while I was driving home to my parents’ house for fall break, and he looked pretty freshly dead, so I thought that would be the best way to go. It didn’t stop him from stinking up my car though, and my mom was not pleased that I stuffed him in the basement freezer. He made it back to school in a Styrofoam cooler, and I got an A on that assignment, and then we put all of our skulls in the “beetle tank” so that they could finish cleaning the skulls for us. I forgot about it. Fast forward to two years later, I was working for the graduate department while getting my graduate degree, and we were asked to clean out the “bone room” and process the skulls, and I found him, a tag with my name on it attached. He came home to live me ever since.

Next we have the molts, all of which, with the exception of the sea urchin, all came from live animals that continued on living after they had shed their shells. On the bottom left we have my horseshoe crab molts, the larger one was collected on a fisheries survey I was on, the little one I found at a hotel beach in Florida. Just above the horseshoe crabs, we have an urchin that I found in Maine—this one was likely smashed against the rocks by a seagull, because when an urchin dies, it usually doesn’t leave behind it’s spines. Next to it is the large, American Lobster, which came from the lobster at the aquarium I used to work at!! And then, in the bottom right is a spiny lobster molt. Spiny lobsters come from the south eastern united states, but our aquarium collected a spiny lobster in North Carolina. She was one of my favorite animals I worked with in the aquarium.

Then we have the full bodied organisms that were preserved fully. We have European hornets pinned in the bottom block, which are from a small project I worked on as an undergrad. These are invasive to the states. The large blue jar contains a baby sandbar shark. My friend (who is also a biology nerd) found this one for me at a thrift store, so WHO KNOWS how it got there originally—but I gave her a new home none the less. The last three small jars are fish and invertebrates that were collected on my trip studying marine plastics in the Pacific. In one is a Velula velula, or a by-the-wind sailor, which is a small siphonophore (similar to a jelly fish, or like a small man-o-war) that “sails” on the surface of the water with it’s little biological sail! The next one is a myctophid, which I’ve covered in previous posts, but it’s a small, very numerous deep sea fish with bioluminescent photophores on it’s belly. The last is a dragonfish or a viperfish, which is another deep see fish similar to an angler fish, but it’s bioluminescent lure is on it’s chin.

I’ve been putting this collection together for almost 10 years now, and they all have their little spots on my shelves at my home. I just find these pieces of biology so beautiful, and I want to give these animals a second life. I’m not just into dead animals, I have a 55 gallon saltwater tank and a sweet baby puppy as well, but I just love natural specimens--it is just so cool to be able to reach up on your book shelf and be able to study anatomy from the real thing.

Now, there are a myriad of methods required for preserving biological samples, many of which you can do at home with your own materials. Cleaning a skull successfully also depends on the condition that the remains are found in. I rarely do a skull that has a lot of tissue still on it, it’s a lot of work. I do stress though, unless you want to get into some really nasty stuff, it is not for the faint of heart (or people who are easily nauseated). If you want any information on how to clean skulls, both from mammals and from fish, please feel free to contact me in the notes or in the asks.

That being said, as a reminder, there are some legal issues regarding many species. Marine Mammals and endangered species are a no go, even if you find the animal already dead. Make sure to be aware of that when you go out in the field looking for bones. It is also is typically illegal to collect things from state and national parks in the U.S., and I don’t have all the rules for other countries, so just educate yourself before you head out.

As always, if you have any questions or comments PLEASE do not be afraid to ask!

#bone collection#skull collection#natural history collection#spooky season#spooky collection#molt collection#marine biology story of the day#marine biologist#squirrel#comorant#deer#raccoon#otter#cat#atlantic sharpnose shark#blacktip reef shark#red drum#horseshoe crab#sea urchin#American lobster#spiny lobster#sandbar shark#european hornet#velela velela#myctophid#lanternfish#dragonfish#viperfish#preserved specimens

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are We Out Of The Woods Yet?

Whumptober Prompt No. 12 - I think I’ve broken something

Broken Down | Broken Bones | Broken Trust

AO3 Link

###

“There are so many reasons why online classes are better than going to school.”

Peter shook his head. “And there are plenty of reasons why learning in school with other students is preferable. How it helps retain the material better than—”

Morgan groaned without even looking at him, her nose in the air, eyes on the leafy trees above them. “You can learn the same things at home, only then you could have dinner at night with us instead of in your stinky room in Boston.”

“Hey,” he craned his neck to see where she went, then walked after her. “My room doesn’t stink.”

“It’s a boy’s room.” She said it like that alone was a valid argument, when it couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, the girl’s dorms he had been in—

He stopped himself. Not the time and place.

“Or you could go visit May!”

Peter had his hands in his pockets, trying to keep up with her. “Right.”

“You should!” She turned towards him and pointed her phone at him. “You should come with me and mom. She’s taking me next time she flies out to HQ.”

That startled Peter. “She is?”

“Yeah, in like two weeks or so. You should come, Pete! It’d be so much fun.”

Peter pulled a grimace, even if her excitement was infectious. He hadn’t been in LA since before the semester had started and he did miss May, but he’d also been looking into a weekend or two at Yale, wondering, hoping, that things with MJ—

“So, what do you think?”

He forced his mind back to the present. “I think you shouldn’t run off that far, Morg.”

She cocked her head at him, then blinked and made her eyes roll up high towards the treetops. A performance that was only second to the master, her dad.

“You sound like Tony,” she groaned.

Peter pulled a face. “Don’t call your dad by his first name. That’s just weird.”

Her eyes were scanning the trees, hoping to pick up the last couple of tree species that she needed to catalog for her biology project. “You call him Tony.”

“Yeah, so?”

“Well, what’s the difference?”

Peter screwed up his face at the question. “That he’s not actually my dad?”

“Oh please…”

She vanished behind some undergrowth and for a moment Peter’s Spider senses tingled and his heart jumped into his throat. That olive green jacket she was wearing didn’t help her stick out either. Sure, he had the nano-housing units secured on his forearms, but those were only the last resort. The very last resort. The gig would be up if he popped up as Spider-Man from behind a tree and Morgan, she couldn’t know. Not yet, they had agreed. Hurried steps through the trees had him almost fall over a large root until he found her, crouching down on the ground. Her phone still in hand, she took a picture of a random weed.

“What are you doing? I thought we were looking for trees.”

“We’re looking for biodiversity and this is rare basil-mountain mint, which will likely win me this thing.”

Peter blew out a long breath, telling his pulse to calm the fuck down. He just hated not having her in his sight. “Just don’t wander off like that.”

“I didn’t wander off. I just walked.” Morgan stood up, wiping the dark forest soil off her knees. “Plus, don’t change the subject.”

“What subject?”

“Why it’s okay for you to call daddy Tony and not for me?” She didn’t even look at him, eyes on her phone screen. “Is that a weird boy thing?”

“No, it’s…” Peter shook his head. “It’s a your his daughter and I’m the weird dude that comes around to eat out his fridge thing.”

Morgan’s eyebrows were pulled up not unlike Pepper would when she was arguing with Tony. “Harley calls him dad…”

“Not to his face.”

“Ya-ha!”

“Nu-uh!” Peter turned his back, not interested in discussing that in the slightest. Harley, well, was Harley. It wasn’t the same. He had years to build that bond with Tony, when Peter had had, well, fewer years.

“I’m 8, not an idiot, you know.”

“I don’t know, you’re giving a great impression of one…” He had said it louder than he meant to and he hadn’t really meant to say it at all.

Morgan stood up straight like he had taken an actual shot at her. Her lips were pressed into a tight line and she swung around, explicitly away from him, and stalked in the opposite direction.

“Morg…” He blew out a long breath that had his overly long hair blow across his forehead. “Come on, you know I didn’t mean that.”

She turned on her heel, eyes sparkling - which he hoped was with annoyance, anger even, and not with tears - and gave him the finger. Two of them, actually.

He was a horrible influence on her. Well, it was him or Harley. Probably Harley.

Still, he shouldn’t have said that. She was struggling as it was, being called names and such at school, though Tony refused to get her some tutors instead. Went on and on about the social skills he never had the chance to develop in a regular school environment. Peter had to roll his eyes as his father’s words echoed in his own head.

Wait… His eyes widened and he physically shook that train of thought from his mind. That girl was putting ideas in his head that he didn’t need in there at all.

“Dude, the car is in the other direction…” he called after her.

Morgan still walked away from him, only tilted her head all the way back, and screamed towards the sky. “I STILL NEED TO FIND TWO MORE TREES, ASSFACE!”

He groaned, shrugging his arms in surrender as he started to follow her. “I thought that weed thingy will get you the win.”

She didn’t even turn, just held up the same two fingers once again as she stalked further away from him.

“Change that attitude or I’ll have to bring it up in your dad’s exit interview when we get back.”

Not that he actually would.

“Don’t you mean your dad, ASSFACE?!”

Or maybe he would bring it up…

But like a loyal puppy dog, he followed right behind her, and like a loyal puppy dog, he couldn’t help but hold his nose into the wind and…

He sighed under his breath, teeth gritted as he scanned the endless forest around them. He had this feeling and that feeling never meant something cheerful. They were in a remote part of the national park. Very remote. Odds were, he might just be sensing wildlife that could get to them. Boars or… or something bigger maybe?

“Can we just… hey… Morg…” He cursed as he followed along after her. “Morgan!”

“What?!” She had stopped and turned, both her hands balled into fists.

“Can we just walked back towards the car at least?” He pointed behind himself. “I don’t want to get lost in the middle of the damn woods.”

He wouldn’t get lost. He knew where they were, where the car was. That it would take them an hour and 10 minutes to get back to it. What he didn’t like was that girl stalking deeper and deeper into the forest. He shuddered with a sudden wave of goosebumps at the thought. No, they really had to leave.

“Let’s just… let’s just head back. We can take a bit of a curve.” He shot a glance over his shoulder, but it was just the wind ruffling the leaves above them. “I’m sure we’ll find your trees on the way back.”

“But I don’t want to turn around yet!” She was properly mad, foot-stomping and everything.

“Hey!” Peter pulled his shoulders back, his head held high, one finger pointing at her like Tony would do to him. “When I say we go back, we go back. This is not a democratic decision.”

Again, she threw her head back and groaned, but slowly trotted towards him. She had just moved past him as his ears pick up how she quietly muttered “You suck and I hate you!” under her breath.

Peter bit his lip, pretending like he didn’t have any enhanced hearing whatsoever as he followed along behind her. He tried to remind himself that Morgan was just a kid and how kids sometimes say things they didn’t mean because he knew she didn’t really mean that.

His eyes on the ground, head bowed low, trying his best not to fall or have his eyes scratched out by any of the low hanging branches. This wasn’t an environment that he excelled in so maybe that was where that queasy feeling in his stomach came from.

“How’s it going, Morg? Any luck with the rest of your—” He had looked to his left, then to his right, but he couldn’t see her anymore. “Morgan?” He hurried a few steps ahead, craning his neck but there was no sign of her. She must have rushed ahead. Must have stormed of that sulky, little—

“Morgan!” He cursed when a branch hit him in the face, leaving a stinging cut just above his eye. “Dude, seriously, this is not funny any—” His stomach fell into a deep hole as to his right, Morgan’s voice echoed only faintly through the forest, screaming his name.

He hadn’t run this fast ever. Never before, tripping over branches and roots as he went. He only just saw her brown hair disappear through the door of what appeared to be a little hunting cabin, worn down enough to seem deserted. It was just right there mid-among the trees. His feet carried him closer and closer until he reached the edge of a little meadow right in front of the small house. There was a guy next to the door, standing guard or something, openly showing off the handgun he was holding though it wasn’t pointed at Peter. Not yet.

“Nothing to see here,” he called across the distance. “Move along.”

He had stopped, about 50 feet away from the front door, his breathing was fast and shaky, not so much from the run, moreso from his nerves. “How about you get my sister back out here and I’ll think about it.”

“Go’ the wrong house, boy.” The man pointed the gun in the direction that led back towards the main road. “No girl here. Pro'ably went ahead. Waiting at you car.”

“Get her out here right now,” Peter hissed through gritted teeth.

“Nobody here, move along.”

The guy could play all old-man-in-the-woods he wanted, his eyes were sharp and Peter could see it. Without his senses, he might have never heard Morgan cry out earlier. He might not have seen well enough to spot her being dragged through the door frame, but he was still Spider-Man.

“I’ll give you a last try. One more chance to let my sister go or—”

Peter ducked and turned, sought shelter behind the closest tree as he heard the shots that were fired in his direction. It hadn’t been the old fool whose hands Peter had been watching like a hawk. No, there was someone else. Two guns that were shot at him simultaneously.

Not that it mattered. It didn’t matter how closely he had thought he was watching, not to his arm that was painfully burning. Deep breaths. In and out.

“Fuck, fuck, fuck,” he cursed under his breath.

“You’re not welcome here, boy,” the guy at the door hollered in his direction. “Fuck off!”

The door creaked as it was pulled open and then slammed shut with a bang. He cursed himself. Morgan was counting on him. What the fuck was he doing? One quick look determined what he knew to be true. He was dripping blood onto the forest floor. Quickly, he pulled his sweatshirt off and ripped a string of fabric off it, then did his best to one-handedly tie it around his arm.

He was still hiding among the trees but he had no doubt that whoever had shot at him was still up there.

“Fucking bastards.” He didn’t even think about it, just tapped the nano-housing unit on his lower arm and the Iron Spider engulfed him within seconds. It didn’t matter now, his identity wasn’t worth shit as long as Morgan was in danger.

“Peter, I’ve registered severe trauma to your left arm. Calculating closest medical—”

“Karen, stop. It doesn’t matter. It’s just a graze. I need to get into that house over there. Read out heat signatures. Anything you can give me. Morgan’s in there. We need to get her out.”

“Heat sensors are activated. I record six individual signatures within the parameter of the house, one of them Morgan.”

Fuck. Five of them. Peter closed his eyes, concentrated on his pulse, his senses. He was fine. He’d done this a thousand times. Something like this.

“There is no reception but satellite connectivity is now active to send a beacon out to Mr. Stark and the rest of the Avengers.”

He was breathing hard. “Just.. just hold off on that Karen. It’s… it’s fine. I.. I got this. I got this.” It wasn’t… wasn’t that bad. He couldn’t have the team come out for some dudes in the woods. Mr. Stark… Tony would murder him in cold blood for this. It… this wasn’t all that bad. He would just… just get her out and… and then they could tell him together and they would be safe and all of this wouldn’t even be such a big deal.

“Alright, Karen. Here goes nothing.”

As soon as he came out of the trees, there were more shots fired right at him. None of that phased him though. The Iron Spider was bulletproof. Karen made out both shooters, one of them hiding behind the back wall of the building, the other one had crept up onto the roof. His webs hit the one on the rooftop first, immobilizing him completely. The other guy had bolted as soon as he’d seen the suit.

From there on out, the things happening around him were a blur. A weird mixture of slow motion and an out-of-body experience where nothing mattered, nothing except Morgan. It didn’t even matter that this wasn’t just a random cabin in the woods. Maybe it was the fumes from the meth lab they were running in that room that were messing with his mind. Maybe he was losing more blood than he had realized.

None of it mattered, not when Morgan was kneeling on the floor, her eyes red as she cried, cried out for help, for her dad and for Spider-Man. He was winning this. He had to. And for the longest time that he was in that cabin, he thought he really was going to win this. It wasn’t until he stood right in front of Morgan, the man behind her pressing a gun against her neck while she was ringing for air, that he realized the flaw in his plan.

He would never risk her. He… he couldn’t risk Morgan.

Peter was frozen, couldn’t do a single thing, paralyzed by fear. What if he would be too slow? What if they shot her before his webs could bind them? He wouldn’t be able to live with himself. It wasn’t until Morgan had started whispering his name over and over again that he realized he had let the suit retreat far enough to reveal his head at some point. That was right, they had made him do it. Said they’d kill her if he didn’t. He couldn’t risk that. Couldn’t risk his sister.

It was the old guy, the one that had been at the door who was pointing his gun right at Peter’s head now, no nanites to protect him from the impact if the man were to fire. They wanted money. Of course, they did. Not like Peter had a lot of that. Some, sure. They told him to go and get as much as he could carry and maybe, if it was enough, maybe they would let Morgan go.

“I’m… I’m not leaving her here…” His voice was cracking just like his nerves. “I’m not—”

“You’ll leave her here, either breathing or not,” the guy behind Morgan hissed as he pressed the barrel of the gun even firmed against her skin. “Your choice. Try anything, she’s dead.”

His vision was swimming, eyes burning. He had been such a fool. He should have never let her leave his sight, should have grabbed her and bolted the moment his senses had started to pick up the smallest thing. He should have called Mr. Stark. He should have…

“She’s just a child. Just… let her go and… and you’ll keep me.”

The old guy snickered next to Peter. “Who’d pay a dime for you, huh?”

Then everything changed. A cold shiver ran down his spine. Dread and… and hope. The men couldn’t hear him but Peter did. He would know those thrusters anywhere. Just as he was about to call out to Morgan, tell her to keep her eyes closed, the old man’s other hand grabbed him, tightening around his throat. He pushed Peter further away from her, back against the wall right next to the door and Peter… he didn’t do anything. He just let it happened, let the old bastard choke him for if he didn’t, they might hurt her. If he fought, they might kill her and this was almost over.

His knees hit the floor from one moment to the next, as the old man crumbled to the ground next to him. The same was true for the man behind Morgan. Peter was just about to crawl to her, to shield her from… he didn’t know what, but Iron Man blasted in through the door next to him faster than Peter could get up.

The armor around Tony retreated and he almost fell to the floor, crouching down next to Morgan. “I’m here, baby. It’s okay.” He pulled her close, pressed her head against his chest so she didn’t see, didn’t have to look at the mess around them. “It’ll be okay. Don’t worry, baby. It’ll all be just fine.”

He gathered her in his arms and carried her, heading for the door, his armor following behind him.

“You’ll find your way back?”

Peter was still on the floor, his pulse still hammering in his ears. “Yes… yes, Sir.”

He didn’t even look at Peter as he left and it was the worst feeling in the world.

###

Part II is up, Enjoy!

###

This is my first try at a prompt fill and I feel like those are usually supposed to be One-Shots, right? Well, this won’t be. But I think one is also supposed to start on October 1st and do them in the right order… Well, what can I say other than, it is what it is ;)

The Fix-it is based on my Endgame Fix-it “Like You’d Know How It Works“. I’ll likely use this story as the basis for more than one of the Whumptober prompt fills.

#wumptober2020#no.12#whumptober#spider son#irondad#morgan stark#spiderman#peterparker#whump#broken trust#broken down#prompt fill#iron dad and spider son#LYKHIW timeline

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 19: She Blinded Me with Science

Sources

Jocelyn Bell-Burnell

PhysCon

Star Child – NASA

NPR

Reflections on women in science -- diversity and discomfort Ted Talk (YouTube)

We are made of star stuff Ted Talk (YouTube)

Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell describes the discovery of pulsars (YouTube)

Concepción Mendizábal Mendoza

People Pill

México Desconocido (Mexico Discovered)

She Builds Podcast

Instituto de Investigaciones (Investigations Institute)

CAPSULA DEDICADA A LA ING. CONCEPCIÓN MENDIZABAL (Capsule dedicated to Concepción Mendizabal, YouTube)

Seattle Times

Further Learning: Nuestras Voces (Our Voices)

Rosalind Franklin

US National Library of Medicine

SDSC

National Geographic

Further Learning: PBS NOVA

Click below for a transcript of this episode!

Archival Audio: “There’s something else. When you and Jack were little and wanted to know what made it rain, what made the telephone work, whom did you ask? Not dad. He was at work. But I didn't learn about science in school. I had to dig out the encyclopedia later to satisfy you. So you see, women need to know as much about science as some men do.”

Haley: Lady History made me smarter. So my dad and I were watching Jeopardy, and I can't tell you when this was but Alex Trebek was in it and also I don't think the new season came out but I digress. It's the final question where you have to like write it down and it's like this whole very awkwardly put question about like French history and it was like who did she– like she murdered X, Y, and Z who is this. And my dad’s like Joan of Arc and I was like no, Charlotte Corday. And he said “how did you know” and I was like “honestly dad this is like a ninety five percent like balls to the wall guess, but I'm gonna say Charlotte Corday” and it was Charlotte Corday and I was just sitting there like haha! Because my dad– I think I spoke about this I think it was with like Erin– that my dad, the way we would get like our allowance was through…

Alana: Riddles and trivia questions.

Haley: Yeah. So he's still on that like this whole–

Lexi: You still get allowance?

Haley: No no no no.

Lexi: Oh. I was like wow, okay.

Haley: No. I still– I don't get allowance, I wish. The way that we like we just spend the holidays was either playing Codenames, which is like a fun fun board game, everyone should just play it, and then doing crossword puzzles. New York Times comes out with these like questions from the news… like it's ten– usually ten questions, or for the new year they did like thirty questions. So his thing will be like everyone has to answer the New York Times, and he won't give out the answers until we've all done it just to see like who's the smartest of the week. And I've only got like the smartest of the week once.

Alana: Nice.

Haley: To be fair, they watch the news everyday and I do not. I use like my like news app to get like notifications and if I go on some sort of site, that's how I get the news. I'm awful, no one like model after me. But Jeopardy came in clutch just because of this podcast. My dad was like “oh so the podcast like is actually like helping education, growth” and I was like…

Alana: Yes!

Haley: Yaaaas. Thank you. He also said we have a cool logo.

Alana: Um, shout out to Alexia Ibarra, you can find her on Twitter and Instagram at LexiBDraws.

Lexi: So we've proven that the show's educational.

Haley: Yes.

Lexi: We now can continue that claim.

Haley: Yes.

Alana: We knew the show was educational.

Lexi: Although, is it only educating us?

Haley: I have faith we have listeners. Hi listeners.

Alana: Hi listeners. To be fair, we’re kind of the primary… like we can see our reactions to the podcast the most.

Lexi: Hey, listeners. Are you there, it's me Margaret.

[INTRO MUSIC]

Alana: Hello and welcome to Lady History; the good, the bad, and the ugly lady you missed in history class. I'm not sure how she ended up always being first introduced, Lexi. Lexi, what's your favorite science?

Lexi: I should probably say like astrophysics or something because I'm currently interning at the Air and Space Museum, but that would be a lie because my favorite science is probably like earth science, environmental science would be my real favorite science.

Alana: That means next up is Haley. Haley, what's your least favorite science?

Haley: Physics. Hard core physics.

Alana: I really wanted you to say astrophysics.

Haley: I was about to, but like I will forever say physics just because I have a really hard time with numbers and letters being in the same math groups.

Alana: And I'm Alana and as a child I went to science camp for upwards of five years.

Haley: Okay, so my question is did y’all ever learn about like the history of science in class? Because I don't remember, especially I was thinking about this for twentieth century like STEM women because that's our theme. And I realized like I conceptually like didn't realize like what happened in the twentieth century, even though I know it's like the nineteen hundreds that's the twentieth century. But realizing that like my history class didn't really go through that. Like I had no concept of like people from the twentieth century doing impacts of science.

Lexi: We didn’t learn about it in history class, we learned about in science class.

Haley: Yeah, in my science class I can't pull from it I can’t–

Alana: I had– I forget who the author is, but I met him at a Politics and Prose event– when I was in my tenth grade chemistry class, we had reading from a book called The Disappearing Spoon, which was like the discovery, the history of the discovery of a bunch of elements which was really cool and so that was like kind of our history of science thing, that was fun. Also Crash Course recently did a history of science.

Haley: Yes, that’s why I loved it. Yes. So, Crash Course– Hank and John Green, hello.

Alana: Hello. Hank?

Lexi: it wouldn’t be an episode without a Green brothers reference.

Haley: I truly was trying to like figure out a way that wouldn't bring them up with this question.

Alana: I literally was like… you said history of science and I was like Crash Course. Crash Course. Crash Course!

Haley: That's how I got into like not just like forensics and like history of like science and history. But they were the ones that made like science fun for me in high school. And then I got hooked on their history, and then it was college where it was like you can study history, medicine, and bones! Congrats, Haley, here it is! But like in my high school curriculum nothing like twentieth century history and or science was like… science was not a thing. We just were still learning basic cells. Like I just remember every year, come January, we were fucking learning what a cell was. And it's like, okay, mitochondria–

Lexi: You were talking about biological cells every year in school?

Haley: I don't know why, but like at least two years in high school because I was in like the intro to bio and then chemistry even we talked about like cells because it was biochemistry as a unit. And then I took AP bio junior year and then for forensics she brought up cells because of like blood cells and everything.

Lexi: I mean, cells are important.

Haley: Yeah, cells are important.

Alana: Do you remember Punnett squares?

Lexi: Yeah, I love Punnett squares.

Alana: Those are my favorite.

Lexi: Genetic science is actually my favorite science. And it's my mom's favorite science, my mom was actually a biology major.

Haley: Low key…

Lexi: Because she loved Punnett squares.

Haley: I thought like something was wrong with me, like I had a terrible genetic mutation because I could not tell the difference between a capital P. and lowercase P..

Archival Audio: Is astronomy a significantly more inviting field for women today than it was thirty years ago?

Jocelyn Bell-Burnell: Yes, I believe it is and I believe it's getting better all the time. We are becoming more conscious of the differences between men and women– the different ways they work, and the contribution of women is becoming more and more recognized. It's still got a bit to go, but it's coming along very nicely.

Lexi: On July 15th, 1943, Dame Jocelyn Bell-Burnell was born near Lurgan, Northern Ireland. As a young girl, she encountered astronomy through her father’s extensive book collection. Her family, who knew educating girls was important, encouraged her to explore her interest in the subject. She received support in her studies from the staff of the Armagh Observatory, which was near her home. When Jocelyn was attending preparatory school, only boys were permitted to study science. In a TEDx Talk from 2013, Jocelyn recounted being separated from her male peers and assuming it was for physical education, but it turned out the girls were being sent to the “home economics” class while the boys were being sent to science class. Of course, she went home and told her parents. And her parents, who as I mentioned before, believed girls should be educated just like boys, were angry to hear that the school did not allow girls to participate in science class. So along with the parents of two other girls at the school, Jocelyn’s parents fought for her right to study science. The three girls were moved into the science class, but being the only girls in class was not easy. The teacher kept a close eye on the girls. So it was hard for them to overcome being the only girls in that class. But, Jocelyn received the highest score on her science final at the end of that term. She did it, she passed all the boys, and got the highest score despite being disadvantaged by being one of the only girls and by them trying to keep her out of that class. Jocelyn went on to study at the University of Glasgow, where she earned a degree in Physics. She graduated in 1965, and went on to pursue her doctorate at Cambridge. Jocelyn worked with her advisor Antony Hewish to study the mysteries of space. And she assisted in the construction of a radio telescope, which would be used to track quasars, which are large celestial bodies and there’s like a lot more science that makes them… It’s a deep science thing… deep astrophysics. Again, astrophysics is complicated and too big brain for me. But they’re things in space. And when the telescope was ready to operate, Jocelyn was assigned to operate it and analyze the results it produced. And this was like way before computers as we know them today, so the telescope actually printed its results out on a big chart and then she would look at the chart as it was printing out and analyze it that way. Jocelyn began to notice strange results on the charts produced by the telescope, which were faster than those typical of the quasars. Jocelyn did not know it yet, but she had discovered the first evidence of pulsars, highly magnetized rotating compact stars, which are different than the previously mentioned celestial bodies. At first, Jocelyn and her advisor were suspicious that the signals may have been signs of alien life, so they nicknamed them “little green men” signals. A year later, her findings were published in an academic journal. As scientists around the world began to investigate the signals further, they were able to identify them as coming from the stars that I mentioned. And the term pulsar was applied to this type of signal. The press, upon finding out that the discovery had been made by an attractive, young, female graduate student, pounced on the story, of course. But instead of asking her about her scientific studies and the research she was doing, they pestered her with questions about her appearance like “what’s your waist size” so we love that. In 1968, Jocelyn earned her doctorate. That same year she was married, and unfortunately spent much of her marriage focused on her husband’s career rather than her own, moving place to place as he moved place to place. In 1974, her advisor was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for Jocelyn’s contributions to the discovery of pulsars. Alana is raging in the background. After her marriage ended and her son had grown up and gone off to live on his own, she went back to pursuing her own passions. She went on to teach with the goal of making science welcoming and accessible to all students, regardless of gender, class, or race. She became a professor at the Open University, a non-traditional college that allows students to take courses at their own pace, and she was appointed as the chair of physics. Her appointment made her one of only two female physics professors in the United Kingdom, so she joked that they had doubled the number of physics professors that were women in the country, so that’s a little sad, but you know… at least there’s two. In 1999, Jocelyn was interviewed for NASA’s StarChild program, which I believe is now defunct but it was an educational program in the 90s, and you can hear some great audio clips of her answering interview questions on the StarChild website which I will link in the show notes. And Jocelyn has also given several TED and TEDx talks, one of which is about women in science and what it’s like to be a woman in science. And I used it as a source so that will also be linked in the show notes. You can find that there if you’re interested– in the further learning. And I will leave you with a quote from her 2013 TED talk which I thought really summed up her experience, “Those of us who've been early in a field have often had to… play the male game. And I hate to think what a lifetime of doing that has actually done to me.” She should have won the Nobel Prize but they gave it to the guy who was her advisor instead, even though she actually made all the discoveries. And her accent’s adorable.

Alana: Is she still alive?

Lexi: Yeah, she’s 77.

Alana: I’m not good at math.

Lexi: She’ll be 78 this year.

Alana: She’s a Cancer you didn’t point that out.

Lexi: You’re– that’s your thing.

Haley: Concepción Mendizábal Mendoza. I definitely pronounced her middle name incorrectly, I am so sorry. The Z-A with un acento on top of the A always messes me up for some reason. My little lisp comes back. But Concepción is how I’m gonna refer to her. Actually I think it means conception in Spanish, so like that's fun. Here's my little side note read this: my Spanish is declining because my mom is Cuban, therefore my Spanish came from my grandparents so when they died I never had that continuous we talk every single week every… sometimes like every single day, and I'd be speaking Spanish so in those like six years I have not spoken Spanish. I’ve read it and translated it for various projects, however, pronunciation is difficult, apparently. And that also comes in with our gal, coming from Mexico City, a lot of like the publications and references are coming from Mexico, so it took me like ten plus hours because then I was like trying to see what resource was a blog or what resource was like an actual resource and then I found some YouTube and some podcasts. But again, don't stop researching someone even if they come from a different country and you have a hard time like researching. It was still fun. I knew her from like a book of like STEM– she's an engineer, we'll get into it, don't worry. Just sit back and relaxing. It was fun reading in Spanish honestly. My Google translate kept popping up, but some of the Google translates for like the scientific terms were just no Bueno and also with how they like conjugated her name of being conception didn't look great sometimes. But that's Google Translate’s problem. So her being an engineer is rad in itself, but she's Mexico's first female to earn a civil engineering degree, so snaps for that. Ahora abramos nuestro libro de historia! I practiced that five times in the mirror even though I knew how to say all those– Lexi’s cracking up, I just wanted to do a good job. I have a big fear about speaking Spanish even though I'm technically fluent.

Alana: It made me smile. I thought it was cute.

Haley: So Concepción, with her upbringing, it was written in the stars if you will because she was the daughter of the famous engineer Joaquín de Mendizábal y Tamborrel and growing up she was motivated to study. And like one article described her as like her life being a little sheltered? Honestly I think that… that was just like me translating because it did use the word– literally translated sheltered, but it's noted that like her father was an engineer motivating her as well to study. And again being like the first woman engineer, yeah your life was probably a little sheltered in Mexico City where like no other females were studying the same thing in a sense. And in school– and for orienting ourselves in the timeline– it's 1913 to 1917, and her… she had her like basic education at la Normal para Maestras de la capital which is the normal for teachers in the capital. That's like the crude translation. And then she was enrolled into a higher level math in another school, the Escuela de Altos Estudios– which is the school for higher education essentially– and she was one of four women at that school. And this gets a little dicey because not only did she stand out for like being that sparkly fish in the pond, being one of four women, but she was able to tackle difficult civil engineering courses, finishing them without failure. And moving forward a little bit to 1922, she attended Palacio de Minería which is the Palace of Mines and Mining, which is now a museum actually. So it was first built as a space for the Royal School of Mines and Mining, like the royal court there, and then changed to the school for engineering, mines, and physics. However, it's now a museum. Like I said, it kind of gets dicey around the 1913/1917 when she’s taking classes and now we’re a few years later in the 1921s, where she got into the school in the sense that she… she was there listening to classes; however, not fully enrolled until 1926 because she didn't have the high school certificate yet. But again, she passed with flying colors because obviously. And she passed the engineering exam on February 11, 1930 and quick side note because some of y'all are screaming at me saying that she was not the first woman to get a civil engineering degree in like Mexico. There is contention, because around like 1930ish– before, because 1930ish was when Concepción Mendizábal got her degree, so her being the first at 1930. There's another woman who apparently went to the engineering school before her, but from the end result of my snooping, there was no other registered woman at the school between 1792 and 1909, and then also no other like registered woman to have graduated. At this point, it's Concepción because she graduated, and she was the first woman to graduate. She wrote down a lot through her education and post education, and it’s Memorias Prácticas, which is practical memories. And literally what I'm thinking of practical memories is books and notes. Again with my research it's very much scattered of translating from what I deemed as the best resources coming from Mexico. Please give me more research sources, let me learn more about this gal. So practical memories, I'm guessing are just like her books and notes and they're still in the Palacio de Minería or the Palace of Mines and Mining, again, which is now a museum. So I thought that was like really cool how like her school like recognized that she was just like such a beautiful mind and like so great and talented that they've kept all her stuff. I really want to see it. The Palace of Mines and Mining is not a great website, so I couldn't like go through their collections and actually see it. Maybe one day I'll make it down to Mexico City. And in 1974 she received the Premio Ruth Rivera which is the Ruth Rivera Prize which goes to the best woman in engineering and architecture, which I thought was like really cool because she like continued– she didn’t go after school and like settle down like none of what I read was like her settling down with like a husband and kids, it was all like concretely what she did for engineering. So post her getting the prize and just also she died in 1985, just up to her death she was still working. She wrote a lot. She was the author of like a fifty two volume book– she just knew how to conceptualize or kind of put a lot of hard engineering concepts into writing and into paper which is a really hard thing to do. And the fact that I obviously couldn't see many of them… I tried, maybe I was looking in the wrong places. But I just wanted to see if there was more for like the engineering mind, or if she wrote some things for us as non engineers to read them. Kind of like what Hank Green does. Because that's what interests me. I love when people take what they're like very very good at, especially when it's like a hard science and dwindle it down for people not in that field.

Alana: That's what we do. We’re trying to make our knowledge more accessible. At least that's what I feel like we're doing.

Lexi: That's what we're trying to do.

Alana: That’s why we interrupt each other to be like Hey…

Haley: Yeah.

Alana: What is that?

Lexi: Hey, explain more in depth that thing…

Alana: ...that we all kind of understand, but yeah just in case.

Alana: So. I'm going to start off my story here with a joke that you might know, you might have seen, that joke is… What did Watson and Crick discover?

Haley: Absolutely nothing.

Alana: Rosalind Franklin's notes.

Haley: Gold.

Alana: Thank you. It’s not mine, but I really like that.

Lexi: Exquisite.

Alana: Thank you. If I do a bad job– just like a heads up if I do a bad job explaining the science part of this, I'm sorry. Lexi doesn't speak Chinese, I don't speak science. That's just how it is. So Rosalind Franklin was born July 25, 1920, a Leo, in London, England to a prominent Jewish family… and I'm having an identity crisis because I think I was born into a prominent Jewish family? Anyway. I should talk to my mom about that. She attended Saint Paul’s School for Girls which focused on women getting degrees other than their M. R. S..

Haley: What’s an MRS?

Alana: Oh, I was waiting for a laugh at my joke and Lexi snapped but I didn't get an audible laugh. M R– your MRS degree is Mrs degree… you know…

Haley: Oh my God I just got that!

Lexi: Wait, I thought you were like playing dumb. You’ve never heard that?

Alana: You've never heard MRS degree?

Haley: No.

Alana: It’s my favorite thing. It's like why women in… Like it was this phenomenon of women in the forties and fifties going to college…

Lexi: Yeah.

Alana: … to meet their husbands.

Lexi: To meet men.

Haley: Ring before the spring, I know that one.

Lexi: I’ve never heard ring before the spring but I have heard MRS degree.

Alana: MRS degree!

Haley: So dumb.

Alana: I think they make that joke in Grease.

Haley: It has the same letters as…

Alana: MRS degree. I was waiting for a laugh because I–

Lexi: Your Master’s in being married to a man.

Alana: The MRS– I love that joke, it’s my favorite joke. I think it's so funny. We can dive into why I think that's so funny in therapy. But I have more pressing issues for therapy. So Rosalind was very good at math and science and also languages. She left St Paul's a year early to go to Newnham College which is part of Cambridge University and was one of only two all women colleges at Cambridge. She graduated in 1941. I'm going to summarize the rest of her academic work so that we can get to the good stuff. She earned her PhD in physical chemistry from Cambridge in 1945 after studying the microstructures of carbon and graphite at the British Coal Utilization Research Association where she had done research during World War II. Instead of going into the kind of war work that other women were doing during the war she was doing war-oriented research on carbon and graphite which was more what she was interested in doing the science-y stuff and not like building weapons which was another important part of women’s work in World War II but we're not talking about women in World War II even though I have a lot of feelings about that. In 1947 she started working at a lab in Paris, the name of which I'm not even gonna try to pronounce where she learned how to analyze carbons with x-ray crystallography which is sometimes called x-ray diffraction analysis. I'm sorry I can't explain more about what that is, it's just what it's called. You use X-rays to–

Lexi: If you tried to explain it I wouldn't understand the explanation.

Alana: But maybe… Maybe our listeners will understand and can help explain to me what X-ray crystallography slash diffraction is. Let us know. Write in. A friend of hers, Charles Coulson, suggested, “hey what if you did this, but make it larger biological molecules.” So she took over a project at King's College in London from a scientist named John Randall using X-ray diffraction to take pictures of DNA molecules. This is where Rosalind crosses paths with Maurice Wilkins, who is the first villain of our story. He’s not actually a villain, he's just kind of a chauvinist and annoying. I'm just being dramatic, as usual. Maurice Wilkins thought that our dear Rosalind was just a lab assistant when in actual fact she was conducting her own research. One of my sources was like “this is understandable given the university's attitude towards women at the time.” It's not an excuse. That's not an excuse. You suck. Period. Anyway, so. The specific note that Watson and Crick discovered was a photograph called Photo 51. I can't find any copyright free images of it, but if you go to our show notes… which will be at ladyhistorypod dot tumblr dot com… under further learning there's a PBS website where you can learn more about the photo specifically and see it. The point is it's a very clear photograph of a DNA molecule where you can kind of pretty clearly see the double helix structure, which is like a twisted ladder. It really was only a hop, skip, and a jump for people to figure out that, using this photo, the structure of DNA was the double helix which is like a twisted ladder if you don't know. Maurice Wilkins showed this picture to James Watson and Francis Crick who were also doing DNA research without Rosalind's knowledge or permission. Frustration noises! I'm so angry about this. So Watson and Crick beat Rosalind Franklin to the punch publishing their research even though they were really publishing Rosalind's research. It's like if they were doing a 200 piece puzzle and Rosalind had put in 198 of the pieces, but Watson and Crick came in and put down the last two and were like “look we did a puzzle!” I almost knocked my headphones out I was so angry. Oops.

Lexi: It's like when my mom makes dinner but then my grandma takes it out of the oven and she tells my dad that she made dinner.

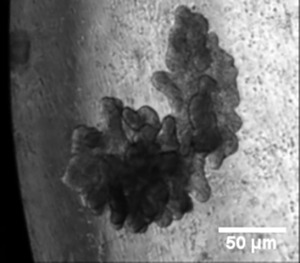

Alana: Yeah pretty much. Rosalind left King's College– I wonder why– for Birkbeck College where she did some X-ray diffraction work with the tobacco mosaic virus– which as far as I can tell only infects plants– as well as the polio virus, specifically on their structure. Rosalind Franklin died of ovarian cancer in 1958 at the age of 37. Four years later, Watson and Crick were awarded the Nobel Prize, which Rosalind would not have been eligible for anyway– I guess– because they don't nominate or award posthumously, but still really annoying. Anyway, Rosalind Franklin, she's really cool, she deserved better. I love her very much, my girl. Even though I have no idea– what she… like I know what she did but I don’t understand how.

Lexi: You know it's absurdly easy to nominate someone for a Nobel Prize.

Alana: It is absurdly easy to nominate someone for a Nobel Prize. And the research was published before she died, so maybe just be like “hey–”

Lexi: It's even easier today. I mean I can't speak for back then, but literally there's a form on a website you fill out. So like someone could have done it before she died. Like I said, they did not have the website back then. But it's not easy today…

Alana: Yeah.

Lexi: There was like… easier then too.

Alana: So that's really annoying to me. They couldn't even be like “hey, you know Rosalind Franklin actually took this picture, and that really helped us.”

Lexi: Just like what happened with my lady.

Alana: Yeah.

Lexi: Her supervisor could be like “actually my grad student really did all the grunt work on this,” you know.

Alana: It's not like Rosalind was even a grad student though. Like she had a PhD and was doing this research.

Lexi: Yeah, it’s just women in science get real… What all women in science, regardless of… the situation.

Haley: And this wasn't that long ago.

Alana: This wasn’t that long ago!

Lexi: We’re talking about the 20th century.

Alana: We’re talking about the 20th century, it’s the 21st century. My grandfather was born in 1927 and he's still alive. And Rosalind was born in…

Lexi: The woman I talked about is younger than my grandmother, yeah.

Alana: They're all still here, there’s still work we gotta do on being more welcoming to people of non male genders just in general.

Haley: There’s just work we have to do as human beings just all across the board.

Alana: In science fields and ever. Ever where.

Lexi: You can find this podcast on Twitter and Instagram at LadyHistoryPod. Our show notes and a transcript of this episode will be on ladyhistorypod dot tumblr dot com. If you like the show, leave us a review, or tell your friends, and if you don't like the show, keep it to yourself.

Alana: Our logo is by Alexia Ibarra you can find her on Twitter and Instagram at LexiBDraws. Our theme music is by me, GarageBand, and Amelia Earhart. Lexi is doing the editing. You will not see us, and we will not see you, but you will hear us, next time, on Lady History.

Haley: Next week on Lady History; she will be the history. We're talking about some modern gals and their impact on our lives. Really we’ll be fangirling a lot. I'm excited, are you excited? Of course you are.

Lexi: It's called “Tomorrow She’ll Be History'' if that inspires anything.

Haley: That's what I was gonna do. I was just gonna repeat the title and see what else comes out of my mouth.

Lexi: Yes I love when… I love when you like mouth– mouth vom. Word vom. Normal vom is mouth vom. But… mouth vom.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Coffee Stained Confusion Ch 3

< Last Chapter First Chapter Next Chapter >

“Tell us everything you know.” Sam looked at the girl sitting in front of them. She was a student at the college, but that alone wouldn’t prove her innocence.

“All I know is what was in the police report that I accidently got ahold of.” she responded. She tried to sound calm but Sam could tell she was nervous. To be fair, she was tied to a chair and had no idea what was going on. Or was that just what she wanted them to believe.

“Hey, Sam, you mind if I talk to you for a minute?” Bucky asked. “I don’t know if this is getting us anywhere. Besides,” he added under his breath, “she’s clearly scared and isn’t going to be a threat. Do we really need her tied up?”

“Fine, we can untie her, but she isn’t leaving yet. Not until we can be sure she’s not with HYDRA. You know Tony would have our heads if we accidently let our only lead go. Let alone the Hell that Steve would raise.”

“You’re right,” he conceded. “But it’s getting late. How about we offer for her to stay the night here? Before you ask, I can sleep on the couch and she can take my room.”

“And if she refuses? We can’t let her just leave.”

“Then it’ll be a late night.”

~~~

You shivered as the two men entered the room again. You could tell one of them had what seemed to be a metal arm, and you assumed that one was Bucky. Something clicked for you then, and your mind flashed back to a news clip of the Avengers fighting an unknown enemy known as The Winter Soldier, who was later revealed to be the “long-dead” best friend of Captain America, James Buchanan Barnes. You found yourself getting nervous, since you weren’t sure exactly whose side he was on.

The other man appeared to be The Falcon, which eased your mind a bit. You remembered him fighting alongside the Avengers, not against them. But what if he had been brainwashed? No, that wouldn’t happen. Would it? You were overthinking everything, and weren’t sure if you had taken your anxiety medicine that morning or not.

“Hey there,” Bucky knelt down beside the chair, “I’m going to untie you alright? I don’t want to regret that decision though, so please don’t make any brash decisions.” he said kindly.

You nodded dumbly, not trusting yourself to speak. Once the ropes were off you slowly rubbed your wrists, noticing some burn marks where you must have struggled against the ropes without realizing it.

Bucky’s eyes met yours, and for a brief second you forgot all about where you were as you felt butterflies fill your stomach. As soon as your broke eye contact the filling was forgotten and you felt panic seize you again. Sam cleared his throat, seemingly uncomfortable with the scene playing out before him. “So, do you want to tell her about the deal or should I?” he asked.

“Wait, what deal?” you asked, fear seeping through your body. “Like a plea deal? Oh God, I can’t go to jail-”

“No, not a plea deal.” Bucky said with a light chuckle. “A deal about questioning. And, uh, sleeping arrangements. It’s getting a little late, and rather than us all be up til who knows when asking you questions, we were thinking you could spend the night here and we could pick things back up in the morning when we’re all well-rested. Now, you don’t need to worry, you get to sleep in a regular bed and I’ll take the couch. Does that sound alright?”

“Well, yes, that should be fine. I’m assuming I don’t have much choice in the matter. If it wouldn’t be too much trouble though, could I go back to my dorm to get my anxiety medication. It helps calm me down a lot and I don’t do too well without it.”

“Well, it probably isn’t the best idea but I think it would be alright.” Sam stated. “Bucky, you can drive her over? Unless you’ll be needing some backup?” he said with a laugh.

“I’ll be fine, Sam.” Bucky retorted, rolling his eyes. “We’ll be back soon enough.” He led you to the door, and as you stepped outside the cold night air chilled you to the bone. You shivered audibly but said nothing. You didn’t want to seem any weaker than you already did. “I’m sorry we didn’t bring a jacket with us. Here, you can have mine. I really don’t need it anyways.”

“Are you sure? I wouldn’t want to be any trouble, and I don’t want you to get sick because of me.” you responded, blushing slightly.

“It’s fine, don’t worry about it. Besides, if my mother taught me anything it was how to be a gentleman. As for the getting sick part, one benefit of being a super-soldier is not having to deal with the common cold.” He shrugged his jacket off and you glanced away, trying not to stare. You shivered again, worse this time, and quickly grabbed the jacket.

“I really didn’t know anything about the murders until the papers got switched. It was an accident.”

“It’s alright, I believe you. Sam does too, he’s just being cautious.” As you got to your old, beaten down car that somehow still passed inspection he opened the door for you. “To be honest, I can see why he’d want you to have a lead, we need to get one soon, or else all of this is for nothing.”

You chewed on your lower lip in thought as you got into the car. “Well, maybe I shouldn’t be saying this, it might just drag me deeper into the case but I think I have a lead for you. In biology we were discussing poisons and their effects on the human body. We just finished a unit on belladonna. It’s not much, it’s probably just a coincidence, but it might help you.”

“Was there, by chance, a unit on cyanide?”

“Um, yeah, about a week or two ago, why?’

“Well doll, I think you just helped us find a lead.”

~~~

Me? Actually updating? It's more likely than you think! Anyways, thank you all so much for the continued support! Sorry this chapter is on the shorter side, but I promise the next one will make up for it! As always, likes and reblogs are appreciated! Let me know if you want to be added to the tag list! Love you all <3

#Bucky Barnes#bucky barnes x reader#bucky barnes fanfiction#bucky x reader#james buchanan barnes#bucky fanfic#bucky x y/n#james bucky barnes#sam wilson#my wriitng#fanfic#fanfiction#winter soldier#captain america#ca:tws#ca:cw#falcon and winter soldier#the falcon#winter solider imagine#bucky barnes imagine#winter solider x reader#winter solider fanfiction#bucky barnes x you#coffee stained confusion

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

TLDR: How the Coronavirus Hacks the Immune System

At a laboratory in Manhattan, researchers have discovered how SARS-CoV-2 uses our defenses against us.

By James Somers

November 2, 2020

Some four billion years ago, in the shallow waters where life began, our earliest ancestors led lives of constant emergency. In a barren world, each single-celled amoeba was an inconceivably rich concentration of resources, and to live was to be beset by parasites. One of these, the giant Mimivirus, masqueraded as food; within four hours of being eaten, it could turn an amoeba into a virus factory. And yet, as the nineteenth-century mathematician Augustus de Morgan said, “Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em, and little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum.” The Mimivirus had its own parasites, which sometimes followed it as it entered an amoeba. Once inside, they crippled the Mimivirus factory. This trick was so useful that, eventually, amoebas integrated the parasites’ genes into their own genomes, creating one of the earliest weapons in the immune system.