Text

Do you love the colour of the sturgeon?

Which one?

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

Less than 24 hours left to the ceremony!!!!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life after life.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sea Creature of the Day is the Magnapinna Squid!!

ive got a big week ahead of me and don't know for certain if ill have the time to post :3 so! i wanted to do the big one :3 bigfin squids!!!! these adorable little fellas get such a bad rep on the internet for being terrifying but they're like, the cutest thing to me.

sure so much of the ocean is terrifying but so many of the animals people are scared of aren't even the scary ones? magnapinnas are just lil sweethearts and i love them so much 💜💜💜💜💜💜💜

678 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tell the Two Fingers,

That Ranni the Witch cometh, to rend thy flesh

#ranni the witch#fanart#ranni#lunar princess ranni#elden ring#elden ring fanart#my art#yes i have not played elden ring#(because i am not good at video games)#but i love ranni. she's the best#she's done no wrong. aside from the murders#(including the murders)#funkiest demigod. slew her own body#slew her stepbro (godwyn) primarily to get back at her stepmom#(or well that's my interpretation of it)#anyway fallen angel by alexandre cabanel stays winning for drama reference

559 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skylark, Chapter 1.

The Skylark sat upon an old boxcar adjusting the valves on her gas mask. The car lay on its side, decrepit and half rusted; a once important piece of infrastructure left to rot. It was quiet here, and the rain had stopped for now. What had once been a city and outpost now sagged and sunk. From here, on a turned over boxcar resting on an old loading station halfway up the old central tower, the Skylark had a vast view of the Zone which lay shortly beyond the old edge of the outpost. It had been of a pair; its twin lay inside the Zone, built by the Bastion to be a monument of human ingenuity. It had become a monument of hubris instead

It was not long until the rain started again. Today it fell as dust rain, dark grey drops which shattered on the ground. A boon of sorts. Not something you’d want to drink unfiltered, but better than the acid rains or the rare blood rains. The Skylark stayed for a while, trying to gauge how the zone was acting. The wind was faint today, so she strained her ears to listen. Then, with a huff, she rose to her feet and gathered up her things, hooking the gasmask onto her tool belt and slinging her rifle-spear across her back. She pulled up the hood of her raincoat and began the long climb down the tower.

Below the overpass at the foot of the tower hung the old propaganda posters of the bastion, boldly proclaiming that this outpost and its twin would herald humanity’s victory over the Zone. No-one had bothered to take them down in the thirty years since the tower in the zone fell. Humans needed something to find humour in, supposed the Skylark. And so the old boast still hung, half-sheltered from the elements. The skylark spat in the printed face of a now-dead king then continued onwards.

To the south, away from the tower and the zone, lay a hollowed-out factory district that served as the homes of the majority of those who’d ended up in the city. The Lark headed east instead, to the river that wound through the city. All the while, the dust rain poured down, forming rivulets of blackened water that trickled through the cracked streets before disappearing underground. There they would either throw themselves down the bellies of the stormdrains or they would join the river, that emerged from the city to the southeast, from where it wandered further, twisting and turning in a roar until it reached a coast somewhere that the Skylark didn’t know.

The path toward the banks of the river was circuitous. First was the old train station, which had once been the heart of the outpost. Even now a train would roll in every once in a while. It had been half a year since the last time. It was a crumbling wreck. Descending down the hillside was the old commercial district. In some places the rain shields had been stripped for the homes down south, leaving the concrete and steel exposed to wither away. Scarce thirty years had passed since this was a bustling, living, outpost. Now all that were left were skeletal ruins. Down further was the river.

When the dams broke it had washed through this place, leaving hollowed out ruins behind. The lark climbed in through the window of one of the grey concrete buildings and continued upward to the old roof-access. Beyond this building the streets were submerged under water; somewhere as shallow as a couple of feet, others several metres below the surface. And in some places the old street level had fallen away, leaving plunging depths for the river to throw itself into. The city predated the Bastion − way the old man by the old storm drain told it, it had been first built before the zones had formed. Before the world had first choked itself on hubris. And as the world choked, as the zones crawled into existence, this city had been one of the last holdouts. But thousands and thousands of years left their mark. Sometimes, in the depths of winter nights with bloodrain strangling the streets, the Lark thought she could hear the whispers of the old city, speaking in a voice that was not a voice at all.

The lark turned south, climbing across the old buildings and rickety paths through the dust rain. She kept an eye over the river as she clambered alongside it. It looked calm today. Upstream of the city lay the Zone. From deep in the maddened landscape the churning waters flowed. It brimmed with life, fish with shimmering scales, crustaceans with river moss growing out of their carapaces, trout with scales that every so often formed fractals, lobsters whose exoskeletons grew into thorny forests that formed moving shelters for smaller things. As the river moved out of the zone it carried its fruits along with it.

The river was the main source of food in the crumbling outpost. Upon the corner of the roof of an old building standing where three paths had once met, the Lark stopped. She waved to the rest of the hunting party, seated below on a wooden deck and preparing as the dust rain fell all about them. Including the Lark, there were five on the hunt. She was early: they wouldn’t leave for another half hour or so. “Lark,” said one of them in greeting, then asked how the river looked. “She’s peaceful today. Saw a flock of herons some two miles north however. Best be quiet.” Herons were bad news. Upon their stilt-like legs they prowled the river, hunting. They were not picky eaters.

The Lark’s job was simple: lookout. Keep an eye out for trouble, and one for prey. She’d clamber over the rickety paths that spanned the shoreward stretches of the river. Good eyes and steady feet. It was a good day for hunting, likely the best they would see in a while. All five of them spent their time preparing; checking harpoons, lacing boots and the like. They talked too, mostly of small things. One of the hunters, a one-eyed man in his forties, asked her how the zone had looked earlier. “It’s uneasy, I’d say. I don’t like the look of it. But I’d have to get to the north of the river to get a better listen.” The one-eyed man nodded at that. Then, after a couple more minutes of rain smattering down, he rose. The hunt was on.

The sturgeon thrashed as the harpoon pierced the bony plates of its flank. It was large – almost three metres long, the skylark estimated from her perch above. As the second harpoonist readied her speargun, the Lark looked north up the river. Here was a good sightline, even through the rain. A little more than a mile north she could see the outlines of the flock of herons she’d spied earlier. They had moved south under the hunt. It made the Lark uneasy. But the herons didn’t seem to have spotted them, so for now they were all right. With the third shot from a harpoonist’s speargun the sturgeon thrashed a last time as a harpoon pierced through one of its four eyes into the brain, then floated silently, held by the lines of the harpoons. It was a good catch. The four of the party helped pull the sturgeon up into the boat. They had caught other fish as well, and gathered some river kelp.

The Lark kept her watch during the hunt. “Good work, everyone,” said the one-eyed man. “Let's get back to town. Have the herons gotten closer?” The last part he directed at the skylark. She told him they were still a bit more than a mile off. He nodded, then started the engine. The four of them would make their way through the ruins of the old district toward what could charitably be called a port. The lark would follow via the rooftops, keep an eye out for any trouble.

The gunshot split the air as the five had barely travelled a street. The skylark dropped onto her belly on instinct. The boat’s pilot killed the engine. “You hurt?” the harpoonist asked the lark. She shook her head. The sound had come from the north, slightly eastward. Up the river, the herons were scattering. She relayed this, then turned back north. Below her the others talked in hushed voices. “Any idea who made the shot” “Militia?” “Aren’t they all dead?” The Lark stared over the landscape, trying to find anything. A heron shrieked in the distance. Its other fellows seemed to be returning to their feast. The pilot asked whether she could see anything. “Only the herons,” she said, then “I could scout more.” A second cry of a heron rang. “Do that then. See you in port. We’ll row,” said the one-eyed man. The Lark nodded at the four, and was off. She kept her gait low, but still fast. Bullets were expensive; whoever made that shot must’ve had a reason for using one. Over the rooftops she scrambled, through the dustrain. It was increasing.

The skylark kept her ears alert as she made her way north. The third scream of a heron cut through the rain. The lark made herself lie motionless upon the roof. The scream was close. Mere seconds later she could see its source, standing less than two-hundred feet away, large and malformed. The lark held her breath and tried to still even her heartbeat. A fast heart might be a fear-response, but hiding from a heron it was worse than useless. The heron screamed again, closer this time. It was bleeding. Had the skylark been someone else she might have prayed. Instead, she simply kept her position: hoped against hope that the heron would pass without noticing her. Its steps through the water were slow. Ten feet tall it stood, a wound in its lower neck.

In front of her, the heron paused. Slowly it swung its eyeless head back and forth. The lark tried to force her heart to stop beating. Blood dripped from the heron’s beak. From the river the Lark could hear other herons’ cry. The heron in front of her turned toward the sound and, with a scream that made the skylark’s ears bleed, headed towards it. She lay still, not moving, until the cry of the wounded heron was far off. Then she picked herself up, wiped away the blood from her ears, and made her way back.

When they made it into port − the skylark having caught up to them followed on the rooftops − the red-clad haruspex was waiting for them. She was old; had been granted a front row seat to the city crumbling. She’d want to see the guts of the fish they had caught. “You’re late,” she said as her greeting. “We made no appointments regarding time,” said the one-eyed man. The haruspex gave a ‘hmph’ as reply, then turned her focus to the catches. “A sturgeon? That’s a good catch. But no trout. Hmph. Ah, but you got me perch.” The haruspex continued talking as the five unloaded the fish and headed to the stall. The skylark and the two harpoonists carried the sturgeon over their shoulders. Once they reached the workplace sheltered from the rain, it was time to carve up the fish. The haruspex took out her tools– various knives, scalpels, hooks, callipers, loupe, and more, as well as a beat up stenotype and camera.

The skylark watched the haruspex at work. Slowly and methodically she disassembled the fish and placed the guts upon the bench. Every once in a while she’d extend a hand to jot down notes with the stenotype. She took apart the guts of the fish like a mechanic dismantling a radio to then carefully put it back together. In the distance were the fishing crew and others, preparing the fish for preservation and eating. The haruspex continued disassembling a fish, then, when all its entrails lay splayed out on the table, she took her conclusive notes on the fish and moved onto the next, carefully taking it apart bit by bit. There was hardly even blood when she worked, aside from the wounds the fish had sustained when it was caught. After the haruspex had gutted the fish, it would be dried and smoked inside what was once a warehouse for one of the factories. The entrails would become either fertiliser for the farms, or be decomposed into the gas that served as fuel for lamps and engines in the city.

Eventually the last of the fishes was gutted and handed off to be smoked and dried. The Lark departed with a de-boned fish as payment for her scouting. There were scarce hours of daylight left as she went west, toward the entrance to the storm drains, where she’d visit the old man who lived there. She needed to speak with him about the weather. If she had read the wind right, there’d be a bloodrain in the coming week. Those were always important to keep track of.

On her way to the storm drain entrance she made sure to gather river moss and kelp. It grew along the sunken walls of the buildings in the shallows. Her boots were good, allowing her to wade through the shallows to get to the mosses. She used her knife to cut them, inspected them, and laid them in a mesh bag. Then, rinse and repeat on her path.

Dinner was a feast of fried river moss, smoked perch, kelp flatbread, and a variety of pickles. The old man was a fantastic cook; it was a joy to simply watch him work. He had an old gas-fired storm stove with a thin cast iron tray on which the moss now was sizzling, while he stirred it regularly. The Skylark and the old man were mostly silent. The two of them were seated under a concrete outcropping with an awning that sheltered them and the food from the pouring dustrain. Beside them stood a row of large jars, with various pickling and fermenting goods.

As he handed her a plate filled with mosses and fish and flatbread, the old man spoke. “So. Why are you here?” he asked her. “Is it so unbelievable I just wanted well made food?” said the Lark. She wasn’t a bad cook per se − she could always make something edible, and half the time it even tasted good − but she paled in comparison to the old man. He simply said ‘yep’ and gave her a lopsided smile. Half his face was a ruin of spines and leathery growths; he could only ever emote with the other half of it. “I read the wind earlier, up the old central tower. I think there’s a bloodrain coming,” said the Skylark, reaching for one of the forks. The old man nodded. “I think you’re right. Day after tomorrow, or possibly the day after that. Won’t be the last of the season; the east wind carries a metal taste.” Well, that did confirm the Lark’s own thoughts. She stared out into the rain. The sun hung low and fat over the buildings. “Eat, little lark. Let’s talk of the weather and the zone later,” the old man said, interrupting her thoughts. She grinned at him, and promptly dug into the feast he’d cooked.

“I’m thinking of making another dive this season,” said the Skylark when she’d scraped off the last remnants of her meal and the two of them were cleaning the dishes. The old man furrowed his half of a brow. She continued, “It’d be good to get one before winter− else it won’t be possible until late spring.” The old man sighed. Before the tower inside the Zone had fallen, he had worked on it − if the Haruspex had been in the front row seats, he’d been a stage hand. “You should visit the chapel first,” he said. The chapel wasn’t really a chapel − it was an abandoned radio post some kilometres south along the river. It was also not what they were talking about. The old man continued dunking the plates into the shallow basin of water. “I’ve known better and more experienced divers than you, Lark,” he said. The sun sank lower “I will visit it after the bloodrain. It’ll be nice to hear from the operator at least.”

Home was a rusting hollow; an abandoned maintenance access carved into a now-broken support pillar of a now-broken bridge that once cut through what would become the flooded district and spanned the river. The lark climbed up the old pillar to the steel grating balcony beneath the door, unlocked the padlock, and entered. The place was small and cramped, even after the guts of machinery it held had been mostly stripped out and harvested. She sat down on a crate by the door, took off her outer gloves, removed the chain grips from her boots, unhooked her toolbelt and set it beside. Her hooded rain tabard she hung by the door. Over the balcony hung an awning that kept the rain off. The sun had set near half an hour earlier. The lark stepped out beneath the awning, leaned back on the concrete pillar, and breathed in the cool evening air. There were still traces of daylight, but they were fast fading.

The Lark stepped back into her hollow, lighting an old lamp and closing the door. Slowly and methodically she removed the rest of her outerwear; knee-guards, boots, coat, fingerless gloves, and waders. Then, with a cup of heated moss juice by her side, she sat down on crossed legs, laid her rifle-spear and boots before her, and began the slow process of maintenance. Her boots were first. She wiped them down, added a thin coat of wax, then stood them aside to maintain the rifle-spear. Slowly, she disassembled it, cleaning and wiping every part, oiling the different mechanisms that allowed the spear-rifle to alternate forms, clearing the bore with the cleaning rod, then varnishing the entire thing. After all the parts were properly cleaned, and her acrid beverage half drunk, she began reassembling it.

On the morrow there’d be more things to do and prepare for. She might need to talk to those of the water tower, a prospect she never looked forward to. She stood the rifle-spear and her boots by the door, and finished her drink, filtering the ground moss between her teeth. In the cities of the bastion, such drinks, called “river moss infused tonics” went for idiotically high prices, touting wonderful health benefits. Here, in a crumbling city-corpse, it was something warm and mildly filling to drink. She sat the cup down upon one of the crates, brushed her teeth, changed into her nightshirt, turned off the light, and went to sleep.

#writing#post apocalypse#skylark#(name of this project)#my writing#original works#original fiction#sci-fi#prose#this is a draft of this chapter#but i like it#will probably post more chapters at a later point

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

What other mythological creatures would be fun in space? If the answer is "most of them?", Then limit the scope of the question to what becomes *more* fun in space?

Still "most of them," unfortunately.

Deep in the bowels of a derelict, drifting hulk, so battered with cosmic rays and space debris all sign of its original function have eroded away, something that could have been human roams the labyrinthine halls. Who knows what terrible crime or tragedy spawned it? It is huge, and hungry, and terribly, terribly alone. All anyone knows is that the drifting hulk that screams to the void in a hundred looping distress calls is to be avoided at all costs, for the maze is deadly and its lone prisoner even deadlier.

An enchanting woman knocks on the porthole with a broad smile, hair flowing in beautiful curls and mouth moving soundlessly in the boiling vacuum. She seems unaware of the inch-thick tempered plasteel, or perhaps unaware of its necessity for the mortal and the fragile within. As she stares unblinking, whispers begin to crackle over the ship radio, half-parseable snatches in many voices - surnames, stardates, coordinates. The knowledge is so, so tempting.

The astronaut is standing just outside the airlock. The sun is starting to sink behind the lunar horizon, cutting razor-sharp shadows across the silvery dust. He's been standing, patiently, for over four hours. The crew in the lander are huddled as far away from the door as possible, unconacipusly avoiding the astronaut's cold and vacant bunk. They had buried him, after all, three rotations ago, the special kind of dead you only get after decompression-induced exsanguination. And yet here he stands, looking better than ever, a healthy blush in his cheeks clearly visible without that bulky reflective helmet in the way. His eyes catch the setting sun strangely, almost red.

Space is an ocean, they say; the analogy is imperfect, and yet persistent in its poetry. The seafarers of old coasted along the surface of a vast and unknowable deep and called it sailing, and the spacefarers of the new frontier do the same. They speed between the stars or cut through wormhole gates for the occasional shortcut, skimming the three-dimensional surface of the vast four-dimensional space that wormholes can only tentatively pierce, and they are satisfied. But there are strange shadows in the stars, twisting and slow - distortions that ripple out from the hyperdepth and mostly pass without incident, barring the sensitive instruments left screaming in their wake. Nobody has ever seen the four-dimensional leviathans that cast these three-dimensional shadows. At least, nobody who's come back.

They call it a dragon because it flies and it's the scariest thing they've ever seen. It doesn't do it justice. If anything, trying to give it a familiar name only highlights its horrible uncategorizability. It flies, yes - or at least it undulates through atmosphere, seemingly irrelevant to its own mass. It has a golden hoard and breathes poison and fire, or rather the nuclear furnace that boils in its sinuous belly vomits out great gouts of poison fire that leaves stone and flesh as glassy slag and metals fused into radioactive gold. The land all around its lair is blackened and sick, a vile caldera of strange-colored swampland and twisted, fungal trees. In the absolute terror and devastation of its wake, the colonists fall back on old, bad superstitions and offer it a girl…

The sorcerer took out his heart long ago, they say. This is true, but inadequate. His true body is shattered in closely guarded pieces to protect himself from a total death; the form he presents is only a projection of his will onto and through the nanite colony his machinations spawned, a body crafted by the immortal mind and will of one who sacrificed everything to be deathless. His heart is concealed in a small life support capsule in a long-forgotten laboratory in a satellite orbiting the moon of a quarantined colony world; his nervous system wires itself through the vast, organic computer that has taken the place of the planet's core. Backups of backups of backups, redundancies laced through every stolen system. He knows there was a purpose to this, once; a goal to all this sacrifice beyond a simple extension of life. He will never remember who he wanted this for. To be truly deathless, one cannot have a heart.

It's retroviral, they think. No other form of infection could've rewired her cells this fundamentally. It's irreversible without gene therapy, but at least she isn't deteriorating, they say. At least she's holding together while they look for a treatment. She can feel it, though, no matter what the medic says; sub-cellular or not, she can feel it boiling under her skin, sharpening her teeth, burning out from the site of the bite on her arm. And she can feel, with absolute certainty, the planet's two satellites slowly shifting into opposition with the sun, right through the windowless walls of the quarantine pod. She doesn't know what she'll become when the moons are full, but she doesn't speak her suspicions. A part of her - perhaps even a part that's always been there - is very, very eager to find out.

A colony was here once, a long, long time ago. Terraformed and everything, but those were the early days, before they realized you needed a magnetosphere to keep all that air and water from being wicked away by the solar wind. The loss was so gradual it didn't make sense until over a century later, and there wasn't anything they could do for them long-term - wrong kind of core for a polarization op. They did evac, of course, but the priority was low - and it was centuries deep into social development. Everybody on that world had been born there, and some of them didn't want to leave. Way I hear it, some of them insisted on staying - strongly and violently - and the folks in charge eventually got tired of losing troops in a dessicating backwater that was gonna solve itself in less than a century, so they just fudged the paperwork and washed their hands of the whole thing. It's near airless now - stopped being a viable colony world nigh on thirty years back when the last of the ice vanished. But that's not why we steer clear. We don't land there because the locals didn't have the decency to die right, and it can be damn unsettling to catch their shadows sneaking across the sand. They're drawn to ships, you know? Poor bastards still think they can leave.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

New icon!

Tried out some more textured brushes and am really happy with the results

#digital painting#my art#impressionism#portrait#may go in later and make some more adjustments#digital arwork#artist on tumblr

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do people actually just eat cereal with milk? Regular milk?

#nightposting#yogurt w cereal is good#also wouldn’t that just be too runny?#you want some viscousity for it

0 notes

Text

the feminine urge to be a first declension noun

#ah language jokes#greek#I like the first declension feminine nouns though#got a bit more pizazz than the second declension#while the third declension is just three (or frankly more) standing on top of each other in a trench coat

718 notes

·

View notes

Text

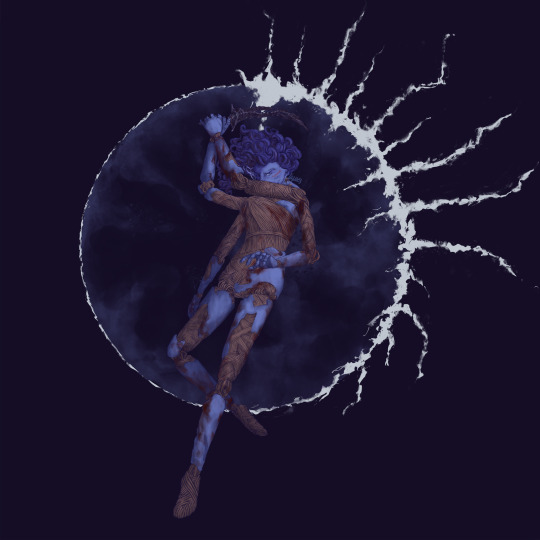

My DND character, Thalassa! A warlock of the Fathomless, sworn to an entity called the Fathomking.

#dnd#warlock#warlock dnd#original character#fathomless warlock#ttrpg#we're sixth level now#its very fun#staged a heist on a lich's castle#that was stressful but we all survived#digital painting#digital art#my art#i need to get a tag for that

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Real Isopod Facts

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

!!!!!! This is fantastic! Also Paige specifically is tied to rhetoric and narrative, she worked in marketing, in crafting rites and gods, and the two gods she interacts with primarily, Babble and the Watcher in the wings, are heavily tied to narrative and rhetoric. Oh and if we compare Carpenter vs the shame and sorrow to Paige vs the watcher in the wings, both gods insisting on a narrative, Paige is much more elegant in wrenching back the power- narrative is, it seems, her element. Carpenter meanwhile screams and breaks things, trying to escape by violence, raging against the shame and sorrow before begging for it, complying with the narrative before finally being able to accept her grief and carry it. And how Paige defeats Hembry by invoking shame and sorrow; the death of his sister who loved him. And in Paige’s first episode, Ware has confirmed that the sacrifice to the crawling in ecstasy was lacking in meaning, a ritual for the sake of ritual - which ties to this post made ages back by katadesmoi and olreid I believe, https://katadesmoi.tumblr.com/post/645168673832747008/adriana-brook-ritual-repetition-in-the-electra And also when carpenter performs the last rites for the corpses and buries them, reciting the prayer to the Cairn Maiden which she states in ep 17 feels off to mouth along to- that she’s transgressing that it should be someone else and I wonder if she’s also trying to play a new role

I rambled a bit there, sorry, but absolutely performance is a theme of S2

i’ve finally caught up on the Silt Verses s2, and what’s striking me most is the recurring theme of performance. like, for instance:

- obviously, there’s the element of theatre in e20 with Hembry and his fucked up god, the Man with Many Faces. in this episode, everything is a performance, with Hembry narrating out loud, and his god as the audience. the story has to be good enough. or else.

- then in e22, we hear Hayward talk about how becoming a cop was just a performance for his mother. “So you put on a show for her,” he says. “You just make yourself into the person they need you to be. And maybe some day you won’t even be pretending any more.” here, the audience is a mother and not a god, but Hayward is still writing his own script. and Paige is able to convince him to help by offering him a different role to play.

- finally, in the devastating time-loop of e24, we have another god with a million faces—the Sorrow-and-Shame, according to the transcript. Carpenter sees through its masks, and accuses it: “You’re not real. This is a performance, nothing more. So let’s get this over with, and maybe you’ll be satisfied.” again and again, we get these themes of performance and satisfaction. the story has to be good enough, or else. and it’s only by rewriting her own script—telling Nana Glass the truth, she’s not okay—that the god is satisfied and Carpenter can escape.

i don’t really know what to do with this observation yet. does it have something to do with the two faces of the Trawlerman? the showmanship of Paige’s dad? the way Faulkner makes people underestimate him on purpose? Adjudicator Shrue’s televised political race? yes, yes, i’m red-string-boarding here.

but my point is—performance and satisfaction are becoming really major themes in season 2, and i’m going to keep an eye out for where that’s going, moving forward.

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

I said it before and i'll say it again

The worldbuilding of tsv is insane. Fantastic. I love it. Thats it, thats the post

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

On ep 5 of the silt verses and this Detective is just venting to Carpenter about his failing marriage. Jesus Christ dude stop ranting to a random stranger in a dinner about your marriage, this is so embarrassing, how do you walk around like this.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh shit.... Carpenter... it's not that she's cursed by the gods. Her problem is that they love her. She's the Trawlerman's favorite.

164 notes

·

View notes