Text

Debt at the heart of the growth paradigm

Before industrialization, much of the world’s population lived in a society with very low per capita economic growth rates. In the 1930’s with the invention of econometrics, economic growth became a symbol of a modern state, and an aspirational goal of the nation to demonstrate progress in comparison to other nations.

However, sustained economic growth comes with an immense social and ecological cost. There is little doubt that increasing pollution and waste generated by the growth economies threaten the well-being of future generations. Likewise, the overuse of the world’s natural resources is eliminating the possibility of people in the majority world achieving the same levels of income as people in high-income countries.

Photo by Alexander Grey on Unsplash

If the problems of the hegemony of growth are obvious, what is creating a “growth trap” so hard to escape?

In today’s economy money is primarily created through the issuance of loans by the private banking sector. Most of the money circulating in the economy is created by private banks. When a person gets a mortgage to buy a new home, the bank creates a deposit account with an equivalent amount of money in the ledger (no new money is printed). However, this deposit is equivalent to other types of money, in fact over 99% of total transactions by value in the UK are bank deposits! Only a fraction of the money is physical cash created by the state.

The problem with this type of money production is that we need to maintain a high level of loans to have money circulating in the economy. Understanding how money is created in the modern economy, and the role of debt in the process of money creation, helps to understand one of the key obstacles to escaping the hegemony of growth.

At the individual level, dept economy means that people must constantly work more than they consume, to be able to pay back their loans. Having a shorter working week, and earning less, is not an option if one needs to pay back a home mortgage or student loan. It is difficult to reduce private debt in the absence of growth.

Likewise, in the non-growing economy, the country governments struggle to pay down their public debt and may need to cut spending on education, health care or other social services. Particularly low and middle-income countries, with large debts issued in foreign currency, are often unable to invest in public infrastructure without taking more loans.

In the worst case to manage their loan payments to international creditors, they must resort to privatising the state assets such as electricity production or drinking water, exposing these “public goods” under speculation of private markets, and making them too expensive to most of the people in the country.

If all loans would be paid back, there would not be money in the economy.

Dept drives growth, which in turn is necessary to avoid financial crises. High levels of public debt mean that growth is the only option to manage the loan without hurting the people living in the country. Likewise, high levels of private debt mean that people have no option other than to continue to contribute their labour to the growth economy.

However, in the current financial system, private banks continue to issue new loans for profit, without any consideration of whether these loans contribute to the economy operating within planetary boundaries or advance equality and social justice.

And while banks and asset mangers cash in profits, the circle of more debt and demands for more growth goes on and on and on….

References

Escaping Growth Dependency – Why reforming money will reduce the need to pursue economic growth at any cost to the environment by PositiveMoney

https://positivemoney.org/publications/escaping-growth-dependency/

Sovereign Money - An Introduction by Ben Dyson, Graham Hodgson and Frank van Lerven

https://www.insearchofsteadystate.org/downloads/Sovereign-Money,-An-Introduction-Dyson-Positive-Money-2016.pdf

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

How about if tourism was stripped of its commodity logic?

Photo by Elizeu Dias on Unsplash

In the capitalist world, tourism is a commodity, a consumer good to escape life's worries, a getaway from the everyday mundane wage-earning reality, and a highlight of a few weeks of annual leave. Once packaged as a commodity, we also demand that it delivers what the wrapping promises. “A worry-free time with good food, sun, and easy access to a few Instagrammable destinations to share with friends and family.”

But there is a deeper meaning for travel beyond what a holiday package can offer. This deeper meaning is rarely met if the starting point is to define tourism as a commodity. If the travel were a pilgrimage, a lifelong learning journey focused on exploration and making new connections, it would start to resemble a different animal altogether.

If the purpose of the travel would be an inner practice of meeting and experiencing culture, environment, and people, it would mean staying on the often-uncomfortable edge, experiencing something different from your familiar surroundings. Travel - a pilgrimage into your life on the planet earth shared with others.

And as a pilgrim, you would not be looking for luxury and comfort because you did not travel there to consume what “they” or the place can offer, searching for the cheapest and most authentic experience from an online app. Instead, you would be there to learn about yourself, reflect on your reactions when meeting the new, and practicing seeing “them” as equals with mutual wonder and reciprocity.

The world of uncommodified tourism is not a one-way street where only you can go and take what is available; it is open to travel in both directions. In this world, you are equally aware that “they”, however different and a little nerving, may come to see you at your home, even at an unexpected time, when you welcome them with open arms and prepare a feast of reunion.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

My majestic friends

In summer 1998 the Finnish Forest Administration hired me to support an inventory determining the potential Natura 2000 areas under the EU Habitats Directive. I was excited about the opportunity and eager to explore the uninhabited forests of Eastern Finland! My task was to identify biodiversity rich sites and gather information that would contribute to a selection of areas for conservation.

I got a light blue Toyota car and maps to navigate the logging roads in Lieksa and Ilomantsi, two remote municipalities in the Eastern Finland. During the days I was alone, and, in the evenings, I met with my fellow workers in the lodging provided to us in camping sites and forester huts.

It was a summer filled with mosquitoes in wet gullies and intense sun in the apocalyptic sites of “final felling”.[1] I also met some bears, and while they must have seen me, I only saw their steaming excrement, coloured blue from the berries (Vaccinium myrtillus), or hastily plunged yellow chantarelle stems (Cantharellus cibarius).

When I close my eyes to look back to the memories of summer 1998, I can see two sites in front of my eyes.

First is a lush grove with northern wolf's-bane (Aconitum lycoctonum) and tall ostrich ferns (Matteuccia struthioptera) and translucent green leaf mosses. It was a tiny green paradise, and I can still hear the water flowing in the creek beneath my feet.

Second is a steep hill with intimate quality of majestic beauty, a few pine trees clearly over 200 years old mingled with younger birch, aspen and rowan. I remember ticking the box of cultural significance and shading the site in the inventory map as a “high conservation value”, frantically looking for something in the list of threated species. To my disappointment, despite the variety of shrubs, flowering plants, and interesting fungus of rotting tree trunks on forest floor, nothing was on my list.

I was a young botany student and my inventory list included mainly plants, but I also looked for signs of small mammals, such as droppings of Siberian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans) that would guarantee the further investigation of the area. Unfortunately, bear was not on my list of key inventory species, I would have loved to tick that box.

A few weeks after finishing the work I got a phone call from my supervisor; she was excited to tell me all the areas that had been accepted to the list. There were several from my list that had made it to the second stage!

The lush green grove was among them, situated in the middle of the otherwise less impressive commercial forest estate, but it was now among those, which could possibly be protected within Natura 2000 new conservation sites. I smiled, and then something darker surfaced from beneath of my belly. With a slightly shaky voice, I asked her: “What about the site shaded with a high conservation value, the beautiful southern slope with old pine trees?”

I could hear her scuffling through her papers, trying to locate the site I was talking about. After a pause, she answered, with a slight hesitation in her voice: “No, that site is not here, unfortunately, it did not make it to the list for further investigation.” After this she again congratulated me on the good notes, and how we had done extremely well, with so many new sites proposed. There was a click, the call had ended.

Photo by Joel & Jasmin Førestbird on Unsplash

Who holds the history when the one who has seen it is gone?

Now after 30 years when I close my eyes, I can still smell the pine resin, it is like encountering an old friend after a long time. In my imagination these same pine trees shaded children in the forest herding the cows, in the young independent country of Finland at the start of the century, or a soldier during the second world war stopped to admire the view opening from the southern slope during his advance. Perhaps, a few centuries earlier, the ancestors of these trees provided encouragement for the hunter searching for an elk to serve as dinner to her clan. And then, when I open my eyes, I remember that these pine trees, my majestic friends, are no more there.

These trees were “too old”, not a prime quality timber for construction, clearly over the official recommended final felling time. However, if they did not make to the Natura 2000 list, I don’t think there was anything to stopping their commercial use.

“The fibres of conifers, such as pine and spruce, are long and spaced apart. Because the long fibres give the pulp strength, softwood pulp is often used for products that require durability. Coniferous wood also increases the absorbency of the product, making it suitable for applications such as paper towels, baby nappies and other hygiene products.[2]”

Maybe these pines ended up as pulp and paper for packaging the goods we buy at the supermarket, or as nappies, or as toilet paper.

We humans categorise and classify, put some species in the list of threatened, vulnerable and endangered, making them scarce and more “valuable”, and some on the common list of trivial and prevailing, and thus exploitable. We make decisions to conserve or utilise based on the arbitrary boundaries of modernity on what is valuable and what is not. Is that the best we can make?

________________

References

1] Up to very recently Finnish forest management guidelines suggested clear-cutting/final felling of trees at the end of the “cultivation” period, which included ploughing the ground, which turn the forest floor into treacherous swales and heaps.

2] https://www.upmpulp.com/fi/uutiset-ja-materiaalit/blogit-ja-tarinat/stories/sellu-yllattaa-monipuolisuudellaan/

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metalogue on (non)capitalist aims

Scene: two people meet at the old railway station in the place of “hay and water.”

A: Train is late again today; would you like to have a cup of coffee while waiting?

B: Yes, why not. No, I don’t take any milk. What do you plan to do with this place? What will it be? (Q1)

A: I don’t know. What would you like it to be?

B: Hmm. So, you are going to live here then? (Q2)

A: No, this is not our home.

Some more inaudible chatter…. people conversing may move inside and walk through the empty rooms…they return to the front of the station at the end of the conversation. Then, a train arrives.

B: And how much is it for the coffee? (Q3)

A: Nothing, it’s free, you are our guest.

B: But I could pay something.

..............

“Customer satisfaction” survey (n=43) (1.6-8.7.2022)

Q1 = the most common question; everyone is asking this (41/43)

Q2 = many are asking this (28/43)

Q3 = some are asking this (Note: only people with urban background) (7/43)

*Ref: Bateson, G. (1972) Steps to an Ecology of Mind - Metalogue: “… a conversation about some problematic subject. This conversation should be such that not only do the participants discuss the problem, but the structure of the conversation as a whole is also relevant to the same subject’.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queer(ing) the degrowth ecology

In her article titled Toward a Queer Ecofeminism Greta Gaard (1997) argues for the need for increased understanding of the value of queer theories in the ecofeminist discourse on heterosexism. The hierarchal up-down thinking that places men up and women down in a patriarchal system cannot be tackled simply by reversing the order with a direct corrective and calling for equality for all, but by cultivating a deeper understanding of the dominant logic behind the tendency to group people in categories based on their gender, class, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and sexual orientation. Queer(ing) the degrowth ecology means a new viewpoint into the patriarchal modes of the economy.

Photo by Gary Ellis on Unsplash

Timothy Morton in his book The Ecological Thought, 2012, argues that environmentalists have done a similar conceptual error to capitalists while imagining that there is a Nature “somewhere out there” that needs to be protected. While capitalists have regarded nature as an externality to economic growth, the environmentalists have tended to perpetuate the same dualist thinking, viewing the role of a man as a saviour of the fragile (and feminine) nature. This has created confusion about our place in nature and solidified our common understanding of the heteronormative rules of reproduction and relationships.

The same confusion is commonplace in the phenomenon of drawing strict lines between “human” and “more than human” world. Our bodies are living environments to a broad range of microbes that evolve quickly, swap genes, multiply, and adapt to changing circumstances. These micro-organisms help us in absorbing nutrients, breaking down toxins, and replacing damaged cells with new ones. They are part of “us” and without them, we would not be. Boundaries of people and other animals blur when we realize the deeply interconnected nature of bodies with other living beings.

Queer ecology challenges traditional ideas regarding which organisms, species, and individuals have value, and helps to see the problematic nature of capitalist economies that divide humans and more than human beings into different groups depending on their “economic productivity” and whether they are “contributing to” or are taking out and thus “draining” the economy. While interrogating our conceptions of how nature works, and our place in the ecology, we ask whether our conceptions of how the economy works and our place in it, have been misplaced.

Ecology is weirder and queerer than we might have made to believe. The conventional thinking of the gender binary is more an exception than a rule in the living ecosystem, and heteronormative concepts of reproduction start to crumble with a closer look at actual relationships between living beings. Morton (2012) reminds us that majority of reproduction is asexual and heterosexual reproduction is a late addition to an ocean of asexual division. Most plants and half animals are sequentially or simultaneously hermaphroditic; many live with constant transgender switching. While only some of the animals are hermaphroditic, bisexuality is prevalent in the animal kingdom — including courtship, affection, and parenting among same-sex animal pairs.

Similarly, Brigitte Baptista, director of the Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute in Colombia, points out in her vivid TED talk (April 2018) how our quest to understand the nature through a scientific method has led to breaking the ecology into parts of unrelated items that we have grouped in different categories. While providing accurate descriptions of the individual parts of a system, these specimens lack the gender identity formed in relationships with others. At the same time, we have made our own assumptions and possibly false interpretations of how these parts relate to each other.

The patriarchal dualism in traditional philosophy and hegemony of growth imposed by the mainstream economic thought, are deeply interwoven. Capitalism was built on the foundations of pre-existing patriarchal systems, with a social hierarchy that placed a certain group of men above others, enabling the devaluation of the work of other people, and making it socially acceptable to create exploitative relationships that fuelled wealth accumulation. On a deeper level, this was possible because of the splitting of certain groups of people into different categories and the upholding of gender and social norms that made it possible to keep these categories separate.

The metaphoric iceberg (Figure 1) illustrates the interrelations of the money economy and non-paid spheres that lay below the surface of our current social imaginary of the economy. The tip of the iceberg, representing the money economy, would not float if not being supported by a much larger base from which it draws its existence. Although nonpaid care work, and the regenerative capacity of the ecosystems, are prerequisites to create (and accumulate) capital, we tend not to see them as integral to the concept of the economy.

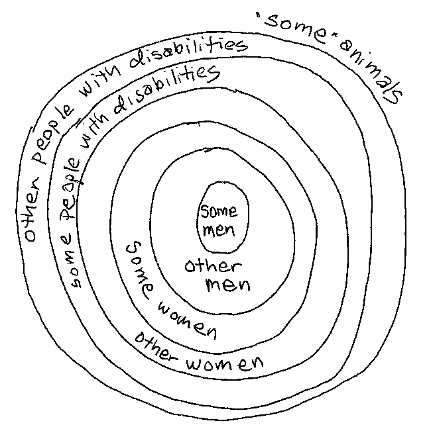

In her lecture Queer(ing) Ecology (Apr 12, 2019 SAS) environmental philosopher Margret Grebowich draws from the thinking of the Australian philosopher and ecofeminist, Val Polumwood (1939-2008)). Quoting Plumwood’s words…, the nature must be seen as a political rather than a descriptive category, a sphere formed from the multiple exclusions of the protagonist-superhero of the western psyche, reason …1 she points out that if we continue to see people, and other species, in specific categories: “some men”, “other men”, “some women”, “other women”, “some disabled”, “other disabled”, “some animals” etc. we always leave someone out (Figure 2).

She concludes that we need to find other ways to deal with the domination than categorizing people into those who are included and those who are excluded. When the splitting on continues there is always someone outside the rights granted to the others.

Queer(ing) the degrowth ecology means a new viewpoint into the patriarchal modes of the economy. We have built an economy on the false premises of separation, seeped into imaginary categories of groups of people who fit in and those who are left out. A closer inquiry into living systems may reveal that what we have been taught to believe is “natural” might be a myth of the modern world.

References

Ambler, L., Earle, J. and Scott, N., (2022) Reclaiming economics for future generations. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978 1 5261 5986 1

Dengler, C. and Lang, M., 2022. Commoning Care: Feminist Degrowth Visions for a Socio-Ecological Transformation. Feminist Economics 28(1), pp. 1-28.

Dengler, C. and Strunk, B. (2018) The Monetized Economy Versus Care and the Environment: Degrowth Perspectives on Reconciling an Antagonism. Feminist Economics 24(3): 160–83.

Gaard, G. (1997) Toward a Queer Ecofeminism. Contributors: Greta Gaard - author. Journal Title: Hypatia. Volume: 12. Issue: 1. Publication Year: 1997. Page Number: 137

Morton, T. (2012) Ecology Without Nature (page 65-71), in Theory on Demand #8 - Depletion Design: A Glossary of Network Ecologies, Ed. Wiedemann, C., Rossiter,N. and Zehle, S. Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2012 ISBN: 978-90-818575-1-2

Morton, T. (2012) The Ecological Thought, Harward University Press ISBN 9780674064225

Plumwood, V. (1993) Feminism and the mastery of nature. New York: Routledge.

VIDEO: Queering the Ecology, Margret Grebowicz, School of Advanced Studies, SAS, April 2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_JyQPdYeBs (link retrieved 11.6.2022)

VIDEO: Brigitte Baptiste, Nada más queer que la naturaleza, TEDxRiodelaPlata 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJC1fsaCbnI (link retrieved 11.6.2021)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are we in the House of Glass?

The Buru Quartet illustrates that the works of the modern-day heroes, in their imperfections, are not stories of personal glory. These moves are acts of love that create cracks for those to come. In that work of learning and play, we are no longer individuals but knots in a chain of change.

Photo by Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash

Two interests were coming into confrontation – Europe which had lost its moorings because of the Great War, and the Natives, who were discovering themselves for the first time. And these Natives were not armed with swords and spears, nor with patriotism, and don’t with religion either. Today their weapons were nothing else but speech and pen.

In 1918 the Dutch East Indies, a land we now know as Indonesia was in the making. The Buru Quartet written by the Indonesian literary Master, Pramoedya Ananta Toer is a remarkable saga from the late 18th century to The First World War period illustrating the outlines of the colonial struggle through the eyes of two opposing, but equally forgotten, individuals.

The book, written in the first person, has two protagonists. Raden Mas Minke,[1] an early antagonist of colonial rule is the central figure in the three first volumes of the saga. The story follows him as a medical student and then as a journalist, exposing the contradictions he sees in western ideals of freedom and personal liberties with the continuing oppression and “ignorance” of the Natives. The House of Glass is the last volume of the tetralogy. Then focus turns from Minke, a shining light of the Native awakening, to another western-educated "Native”, police chief Pangemanann, whose duty is to arrest Minke as the enemy of colonial powers.

In this last volume of the Buru Quartet – House of Glass, the reader finds herself perplexed to face a more nuanced picture of the institutional workings of the oppression. It is a surprising turn. The protagonist of the last volume, the police chief Pangemanann, is the very instrument that holds the colonial system in place, spying on the workings of the Native uprising. However, as opposed to his task of keeping Raden Mas Minke under his control, he himself regards Minke as his personal “hero”. Pangemanann is a great admirer of the principled and “free” individual, under his surveillance.

Once again, I would have to meet him [Minke]. So, we would no longer just be playing chess against each other from afar. He had never surrendered his principles he has just lost his freedom.

The period from the late 18th century to the early 19th century described in the book created conditions for the growth paradigm and capitalist economies today. The hegemony of growth is built on the colonial expansion and extraction of wealth. South-North critique of economic growth relies on and reproduces relations of domination, extraction, and exploitation between the capitalist center and periphery. While the regions under colonial rule, such as the Dutch East Indies, were colonized in the physical sense, with borders and administrative arrangements, relations of domination are reproduced by the global capitalist market economy up to date, fortified by institutions that create conditions for the hegemony of growth.

What is interesting in the narrative of the Buru Quartet is the illustration of the workings of an institution required to create conditions for this extraction and expansion. There is not a clear line of power between the periphery in the South and the capitalist center in the North, but in fact, the continuity of the system is upheld by the relationships between individuals who protect the system from opposing forces and allow the accumulation of wealth to perpetuate. These individuals like the police chief Pangemanann face a double bind. At the personal level they disagree with the goal of the system, but at the same time continue to uphold and fortify its workings.

At the end of these notes, I wrote: A Servant of the Government! Somebody who is always responsible to the government and feels responsibility to the government, such people never accept responsibility themselves, except to ensure their own security and enjoyment…. And as an official I also had a typical personality of an official. I stamped as forbidden, immoral, and heathen everything that was in conflict with loyalty to the government of the Indies.

Even if he clearly sees his own role in protecting the institution of power that leads to the suffering of his countrymen, he is incapable to move the course of the boat and continues to conform to the rules of the game. He feels trapped in the institution that gives him exceptional wealth and status, compared to his countrymen. In fact, what he most fears is losing his face towards those he loves, his role as the breadwinner and husband, and the continuity of the education of his children through Dutch East Indies administration funds.

The story of the Buru Quartet is deeply humane, revealing the person trapped in the institution that provides him personal identity and worth, but destroys his values and moral standing. A cultural critique of economic growth produces alienating ways of working, living, and relating to each other and nature. This critique is not only applicable to the period of modern-day economies, but to various institutional forms of oppression. The stickiness of the intuition to resist change comes from relationships between individuals that receive their identity from acts that fortify the organization.

While Pangemanann in his desolate role, sinks deeper and deeper in the mud of colonial powers, begging for acceptance and reconciliation, he is also aware that the very system that he is trying to orchestrate, is changing in ways that are beyond his control. Even if individuals placed under his surveillance might not be able to achieve their full potential in leading the revolution, their contributions leave marks in the soil, which are picked up by the next generation.

….the government which we came to know only through feeling its action, was nothing more than the manifestation of the supreme power, yet it was still a power wielded by humans, and human error was in turn an essential feature of human’s own imperfection. And my children, this younger generation, paid more heed to the human character of the government – in other words, the things that weren’t right, its weakness, its mistakes.

Without revealing too much of the plot, I can point out that in the end the police chief Pangemannan, the protagonist of the last volume of the Buru Quartet, also makes a significant personal contribution to the national uprising in Indonesia, albeit for reasons beyond his control.

Book Review: House of Glass - Pramoedya Ananta Toer, English Translation 1992 - The quotations above are derived from the last volume of the Buru quartet House of Glass. Buru quartet, first released in 1979, but only officially in circulation since 1999, is well known and loved literary classic in Indonesia. It is also a deeply controversial book that reveals the struggle of courageous individuals involved in the independence movement and beyond to build a democratic nation; a project that is still very much in making. As a critic of the military dictatorship, Pramoedya Ananta Toer was detained with other political prisoners on the island of Maluku during the New Order Regime of Suharto (Suharto’s authoritarian government was in power from 1966 to 1998). Pramoedya narrated the story of Minke and Pangemanann to his fellow prisoners to provide entertainment to the mundane daily routines of the detention camp. Pramoedya Ananta Toer ‘s work was censored in Indonesia until mid-2000. While still officially banned in Indonesia, the Buru quartet became a popular reading among the student protest movement in the 80s, and particularly its two last volumes provided material to reform-minded citizens and activists to study the dynamics of the uprising.

Katja Pellini is an international development cooperation practitioner from Finland and studying Master’s Degree in Degrowth in Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. She has lived and worked in Indonesia 2013-2017.

[1]Raden and mas are titles held by the members of the Javenese aristocracy, Minke was a son of a Bupati - Native Javanese official with noble blood, appointed by the Dutch assistant resident to administer a region; Bupati is up to date the leader of an administrative unit/regent in a modern day Indonesia

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas in the shadow of a storm

Preparing for Christmas eight years after, I reposted this story on the Yolanda storm in the Philippines 2013 - a slightly shorter version of it was published in Plan International Finland blog a month ago. With the ever-increasing weather shocks interlinked to a warming planet, it is not a story from history only but a reminder of what is to come. (warning....this is in Finnish)

Photo by Cole Geconcillo on Unsplash

Lauantaina yhdeksäs marraskuuta 2013 Dumagueten kaupungissa, Negros Oriental saarella, Filippiineillä, aurinko paistaa kirkkaalta taivaalta. Puuskaisesta tuulesta, joka riepotteli kadun varren palmuja eilen, ei ole tietoakaan. Olen kantamassa täytekakkua ulos, kun BBC:n toimittaja soittaa: ”Miten teillä menee, oletteko kunnossa?” En tiedä mitä vastasin. Vaikka käytännössä koko kaupunki, jossa silloin asuimme, oli suljettu, mitään erityistä ei ollut tapahtunut. Myrsky ei ollut yltänyt meille asti. Nyt myrskyn jälkeisenä päivänä juhlimme tyttäreni seitsemänvuotis syntymäpäivää ja pihallemme oli kerääntynyt joukko lapsia ja aikuisia.

Toimittaja ei anna periksi: ”Mitä uutisissa sanotaan? Mitä olet kuullut muilta saarilta?” olen hämmentynyt, koska kuulen hätää hänen äänessään. Aamulla kuuntelin uutisia, joissa kerrottiin, että kolme ihmistä oli menehtynyt eilisessä myrkyssä. Kaikki kollegani oli evakuoitu Leyten saarelta jo päiviä ennen, joten tiesin että heillä ei ollut mitään hätää. Minulla ei ollut muuta tietoa.

Hayan supertaifuuni, tai Yolanda hirmumyrsky kuten paikalliset sitä kutsuivat, iski perjantaina kahdeksas marraskuuta Filippiinien itä rannikolle. Yolanda oli Filippiinien historian tuhoisin myrsky. Se ei vain rikkonut tietoliikenneverkkoja mutta myös tiet, sillat ja lentoliikenne Taclobanin kaupunkiin, jota myrsky riepotteli pahiten, olivat poikki viikkoja.

Kokonaiskuva tuhoista valui hitaasti filippiiniläisten, ja meidän, maassa asuvien ulkomaalaisten, tietoisuuteen. Ihmiset keräsivät tietoa ensin sosiaalisesta mediasta, kansainvälisestä mediasta, ja vasta sitten tuhojen laajuus alkoi hahmottua virallisten kanavien kautta. Kun BBC:n toimittaja soitti, olin autuaan tietämätön siitä, mitä Filippiineillä oli oikeasti tapahtunut edellisenä päivänä. Juhlimme syntymäpäiviä, samalla kun Taclobanin kaupungin edustalla, vain 300 kilometrin päässä meistä, ajelehti tuhansia ruumiita meressä.

Photo by Anandu Vinod on Unsplash

Filippiiniläiset ovat tottuneet ja osaavat varautua hyvin vuosittaisiin hirmumyrskyihin, mutta Yolandan voimakkuus oli niin suuri ja ennennäkemätön, että siihen ei oltu varauduttu tarpeeksi hyvin. Laitakaupungin korttelit ja rannikolla sijaitsevat kalastajakylät kokivat täydellisen hävityksen. Taclobanin kaupungin paikallishallinto ja peruspalvelut romahtivat, vain 70 kaupungin työntekijöistä tuli töihin katastrofin jälkeisinä päivinä verrattuna 2500 ihmisen työvoimaan, jotka tavallisesti vastaavat hallinnosta, kouluista ja terveyspalveluista. Monet heistä kuolivat, loukkaantuivat, menettivät perheensä tai olivat liian traumatisoituneita pystyäkseen työskentelemään (1). Kaiken kaikkiaan myrsky kosketti yli 16 miljoonaa ihmistä, joista 1,9 miljoonaa menetti kotinsa. Plan Internationalin video kuvaa myrskytuhoja, sekä työmme tuloksia, vuoden kuluttua myrskystä.

On selvää, että myrskyriskit evät jakaannu tasaisesti, vaan lisäävät entuudestaan syrjityssä asemassa olevien, etenkin tyttöjen, lasten, vammaisten ja naisten, haavoittuvuutta. Köyhillä on vähemmän mahdollisuuksia turvautua tai hakeutua suojaan kuin niillä, joiden kodit on rakennettu kestämään. Siksi, varsinkin köyhälistökortteleiden asukkaat eivät halunneet Yolandan aikaan jättää talojaan myrskyn lähestyessä, koska he tiesivät kokemuksesta, että vähäinen omaisuus kevytrakenteisissa taloissa lentäisi helposti taivaan tuuliin tai tuhoutuisi rankkasateessa täysin.

Vuoden 2013 jälkeen Filippiineille on iskenyt ainakin kaksi yhtä voimakasta, tai vielä voimakkaampaa myrskyä kuin Yolanda, mutta menetykset ihmishengissä eivät kuitenkaan ole olleet yhtä suuria kuin Yolandan aikaan. Ehkä evakuointi toimet ovat olleet Yolandan jälkeen tehokkaampia, ja ihmiset ovat oppineet olemaan enemmän varuillaan. Voi myös olla, että nämä myrskyt ovat kiertäneet suuret kaupungit. En kuitenkaan usko, että köyhyys tai eriarvoisuus on merkittävästi vähentynyt. Kaupunkien laitamille kohoaa yhä uusia kevytrakenteisia taloja, ja niitä ilmestyy myös ”ei kenenkään maalle” lähelle jokia, jotka tulvivat rankkasateiden aikaan.

Ilmastonmuutoksen vuoksi sään ääri-ilmiöt tulevat lisääntymään ja osa myrskyistä on edellistä voimakkaampia tai tulee eri aikaan kuin tavallisesti. Vain viikko sitten luin Surigao myrskystä, yhdestä historian voimakkaimmasta trooppisesta syklonista, joka kuitenkin täpärästi väisti Filippiinit ja heikkeni trooppiseksi myrskyksi tuoden rannikolle rankkasateita ja puuskaista tuulta, mutta aiheuttaen vain vähän tuhoa (2).

Photo by Charles Deluvio on Unsplash

Vuonna 2013 Yolanda myrsky ei yltänyt Dumagueteen asti, mutta aiemmat myrskyt olivat koskettaneet myös syntymäpäivävieraidemme elämää. Joulukuussa 2012 Pablo myrskyn aikana, kotiapulaisemme toivat omat tyttärensä meille turvaan, kun myrsky riepotteli heidän kotejaan. Sillä kertaa kotiapulaistemme talot kestivät Pablo myrskyn voiman, vaikka monet heidän naapureistaan menettivätkin osan katosta, tai talojen päälle kaatuvat puut rikkoivat rakenteita. Nyt tytöt istuvat puutarhassa odottamassa täytekakkua, jota kannoin pöytään.

Syntymäpäiväpöydän ääressä istui myös kymmenkunta tyttöä Batang Calabnuganin perhekodista kaupunkiin laskevan Banica joen yläjuoksulta. Nämä lapset olivat asuneet lähes vuoden hätämajoituksessa, sen jälkeen, kun joulun alla vuonna 2011 Sendong myrskyn jälkimainingeissa perhekodin sisälle tulviva vesi tuhosi talon alakerran ja puutarhan täysin. Tulva aiheutti valtavat taloudelliset vahingot ystäväpariskunnallemme, Batang Calabniganin perhekodin perustajille. Kesti kauan ennen kuin he saivat kerättyä riittävästi rahaa korjaustöihin. Vasta vuoden kuluttua Sendong myrskystä, ja satojen talkootyöllä tehtyjen korjaustuntien jälkeen, tytöt olivat päässeet palaamaan ”kotiin”.

Näille köyhistä perheistä lähtöisin oleville tytöille oli löytynyt tukijoita Euroopasta. Italialaiselle kansalaisjärjestölle tehdyt yksityislahjoitukset takasivat heidän mahdollisuutensa koulunkäyntiin heti myrskyn jälkeen, ja vapaaehtoiset auttoivat perhekodin korjaamisessa. Näiden tyttöjen koulunkäynti ei keskeytynyt, ja he pääsivät palaamaan turvalliseen perheenomaiseen asumismuotoon.

Tätä toista mahdollisuutta ei anneta kaikille maailman tytöille myrskyn jälkeen. Yhä useampi tyttö kohtaa ainakin yhden elämää ravisuttavan myrskyn, joka uhkaa heidän perusoikeuksiaan, oikeutta koulunkäyntiin ja oikeutta turvalliseen ja terveelliseen asuinympäristöön. Ilmastonmuutoksen vaikutuksesta se myrsky, joka myrskyalttiilla aluilla, kuten Filippiineillä, on ollut osa luonnollista vuodenkiertoa, tulee muuttumaan yhä vaikeammaksi kohdata.

(1) https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z9whg82/revision/4

(2) https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2021/04/16/typhoon-surigae-philippines/ & http://bagong.pagasa.dost.gov.ph/tropical-cyclone/severe-weather-bulletin/2

0 notes

Text

Kahden kerroksen väkeä

On helmikuu vuonna 2016 ja sataa kaatamalla. Olen matkalla luennolle ja myöhässä. Näin jo kotoa lähtiessäni taivaalle kerääntyneet mustat pilvet, mutta ajattelin, että ehdin kyllä bussiin kuivin jaloin. Erehdyin.

Pakenen taivaalta solkenaan valuvaa vettä suojaan lähimmän talon terassille. Talon väki tulee tervehtimään yllätysvierasta, ja perheen tytär tarjoaa minulle riisikakkuja. Terassilla pitää huutaa saadakseen äänensä kuuluviin sateen jylinän yli, mutta ketään muuta kuin minua ei tämä erikoinen tilanne näytä häiritsevän. Ehkä siksi, että kenellekään muulle terassilla olijalle tämä ei ole mitenkään erikoinen tilanne. Laitan viestin luennon järjestäjälle, että joku muu saa tänään esitellä luennoitsijan ja huolehtia aikataulusta. Viestiini vastataan hymiöllä; Jakartassa tämä on arkipäivää. Tunnin myöhästyminen ei ole mikään ihme, ja tavallisin syy on liikenneruuhka, tai tarkemmin sanottuna tulva tai jokin muu este tiellä.

Jakarta on 30 miljoonan ihmisen megakaupunki Kaakkois-Aasiassa, ja se vajoaa. Nopean kaupungistumisen myötä vapaana olevat alueet on asfaltoitu, eikä sadevesi pääse imeytymään maahan. Pohjavesivarannot eivät uusiudu, ja kun vesi johtoverkosta ei riitä, ihmiset pumppaavat vettä omaan käyttöön laittomista porakaivoista. Maanvyörymät ovat rankkasateiden aikaan yleisiä, monin paikoin kaupungin perusta on tyhjän päällä tai jo vajonnut meren pinnan alapuolelle.

Pohjoisissa kaupunginosissa hylätyt teollisuusalueet, pysähtyneet rakennustyömaat ja virastotalojen tyhjät kuoret tervehtivät vierailijaa. Vaikka pilvenpiirtäjät vielä kansoittavat keskikaupungin, näihin pohjoisen kaupungin kortteleihin ei enää rakenneta neljän tähden hotelleja, yritykset eivät investoi uusiin liikerakennuksiin ja asuttujen talojen seinät vihertävät trooppisessa ilmastossa. Hökkelikylien asujat ovat sopeutuneet siihen, että kaupungin palvelut ja viemäriverkosto eivät yllä heidän kotikaduillensa, eivätkä koskaan tulekaan yltämäänkään.

Vaikka Jakarta on tottunut vuosittaisiin rajuilmoihin ja rankkasateisiin, ilmastonmuutoksen myötä myrskyjen voimakkuus on lisääntynyt ja kaatosateita tulee myös silloin, kun niitä ei osata odottaa. Varautumistoimet käyvät kilpajuoksua kasvavan väestön, vajoavan maa, merenpinnan nousun ja muuttuvan ilmaston kanssa. Jakartan lahden ympärille on rakennettu monia kymmeniä kilometrejä tulvavalleja, ja kaupunkia halkovia jokia ja kanaaleja on vahvistettu jokaisessa kaupunginosassa. Tulvien torjuntaan rakennetut pumppausasemat, valumavesisäiliöt ja padot ovat tuttu näkymä kaikkialla kaupungissa, vaikka ne eivät aina ole siinä kunnossa, että niistä olisi hyötyä seuraavan rankkasateen alkaessa. Ilmastonmuutoksen myötä keinot kaupungin pelastamiseksi vähenevät, ja kaupungin johto on jo väläytellyt mahdollisuutta siirtää koko kaupunki kuivemmalle maalle.

Sade omassa naapurustossani on muuttunut tihkuksi, ja lähden kahlaamaan kujille kerääntyneen likaisen veden halki kohti omaa kotia. Kaupunkia halkovan kanaalin molemmin puolin polviin asti yltävä vesi haisee, jätevesi on sekoittunut tulvaveteen. Liejussa kelluu sandaaleja, muovikrääsää ja puun kappaleita. Kiipeän jyrkkää rinnettä ylös kuivalle maalle. Olen takaisin omalla kadulla, ja maailma ympärilläni muuttuu. Tien molemmin puolin seisovat rivissä trooppisen puutarhan ympäröimät kauniit valkoiseksi rapatut talot, talojen pihoilla yksityiset uima-altaat ja autotalleissa autonkuljettajien puhtaana pitämät katumaasturit. Yksi niistä on meidän kotimme. Riisun jo terassilla tulvavedessä rapautuneet liejuiset housut. Niistä ei enää ole työhousuiksi. Kylpyhuoneessa harjaan kuurausharjalla ja pyykinpesuaineella jalat puhtaaksi polviin asti, tavallinen saippua ei riitä poistamaan iholta viemärinhajua.

Me Kemang Timur V:n asukkaat olemme ylemmän kerroksen väkeä. Meille tulva on totta, mutta sitä on helppo paeta. Alemman kerroksen väki, naapurimme kanaalin molemmin puolin, asuu alueella, joka alkaa, kun virallinen tie kotimme jälkeen päättyy. Kartassa tällä alueella ei ole teitä, taloissa ei ole numeroita eikä niiden asukkailla ole osoitteita. Siellä asuvat perheet ovat kuitenkin hyvin todellisia. He maksavat vuokraa, tekevät töitä ja heidän lapsensa käyvät koulua ja leikkivät kaduilla. Joskus, jos säätiedotus lupaa yöksi rankkasateita, perheiden moottoripyöriä pysäköidään meidän kotikadullemme turvaan.

Laitan kahvinkeittimen päälle ja avaan tietokoneen. Onkohan tulvasta jo uutisoitu? Mikä on tilanne muissa kaupunginosissa? Mikään kanava ei kerro tulvista, siis ihan tavallinen rankkasade Jakartassa. Uutiskynnys ei ylity. Kuitenkin tiedän, että naapurini kuivattelevat vielä useita viikkoja tulvan tärvelemiä tavaroitaan. Näiden todellisten perheiden tytöt ja naiset tuulettavat sohvia, sänkyjä, vilttejä ja vaatteita, joita ei voitu, tai ehditty, nostaa turvaan kaduilta ja kotien lattioilta. Ennustan, että aurinko kyllä kuivaa tavarat, mutta viemäreiden haju ei sohvista lähde kulumallakaan.

Ilmastokestävyys tai resilienssi (eng. climate resilience) tarkoittaa tietoista ja ennakoivaa kykyä sopeutua ilmastonmuutokseen, toimia joustavasti häiriötilanteissa sekä toipua ja kehittyä niiden jälkeen. Se on haavoittuvuuksien vähentämistä ja sopeutumiskyvyn vahvistamista. Ilmastokestävyyden ydin koostuu sosiaalisten, taloudellisten ja ekologisten näkökulmien samanaikaisesta huomioimisesta.

Tämä blogi kirjoitus julkaistiin Plan International Suomen sivuilla 26.1.2021

0 notes

Link

Tämä viime kevään interrogativa juttu löytyy nyt suomeksi Pelastetaan Eteläpuisto blogista. Kiitos vielä haastattelutuokiosta Maisa ja Otto!

0 notes

Text

Cultivating skills for resilience PART III

Some resilience skills are for keeping together what already is, while some are for moving forward to what could be. This is a third part of the blog I started a few days ago if you did not read the first go here or the second go here.

Photo by K. P. D. Madhuka on Unsplash

Psychology and resilience

In psychology, resilience is about responding to a multitude of risks, not to an isolated incidence. Specific risk factors can not be looked at in isolation from other risks, and the effect of a risk factor depends on its timing and relationship to other risk factors. Resilience skills in psychology can be broadly divided into three categories.

Resilience skills at the individual level, which are also related to personality, temperament and cognitive ability,

the resilience that comes from social capital and relationships of an individual with other people;

and resilience related to broader environmental factors and institutions (safety, access to life-supporting services etc).

I learnt that while small amounts of stress are good for building resilience, ongoing stress over a long period can result in lifelong physical and psychological consequences. Stressful experiences during critical periods of brain development in infancy and young childhood are particularly detrimental. This sounds quite straightforward.

Then I delve a bit more on the current research on advance neurobiology. It is fascinating to read how environment is changing physiology of an individual even in a lifetime to respond to adversity! We can map out epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, which change gene expressions; preparing the individual for future responses to environmental challenges.

How to connect the psychology of resilience back to the idea of composting?

Fear, doubt, self-hatred and resentment cause resistance for unlearning. If composting and letting go for a change is a vital resilience skill, it is a not a surprise that psychology articles that I did read during this journey, place the self-esteem and sense of control over one’s own life as central resilience characteristics. Conclusively, it does not help to make people who have suffered trauma feel that they are victims of the circumstances, at least not at the personal level.

As a matter of fact, the people that have felt, or are in it just now (be it a climate-related disaster, pandemic or a political conflict), are the real experts of resilience. People who are already profoundly merged in the decay of the modernity, and absurdity of the current development paradigm, are finding alternative ways to nurture life. Remarkably, even in terrible circumstances, people show resilience, a “lust for life”. What this could this mean in practice?

In this podcast episode, Vanessa Andreotti narrates her work with the indigenous communities in Latin America. She used the deep adaptation group practises on “a social collapse” derived from Jem Bendell’s work on deep adaptation. The response of the indigenous community that Vanessa is working with was telling. - What? Are you asking us to imagine what would happen when the so-called “essential” services collapse - if a gasoline station runs out gasoline, or if there is no electricity in the grid, or shelves at the food stores are empty? Some felt offended that this was a picture of a collapse of civilization. - But it is our life now. And we are coping with it, we have to, and we ARE finding ways to live.

I find this insight fascinating. These communities who are in the midst of it all are the best experts to teach resilience skills. It might be helpful if we (who are not so adversely affected by the multiple crises of our globalized world) would pay more attention to what is emerging in these communities. The following anecdote, which I also heard from Vanessa, helps understand this wisdom. “The water needs to be at least knee hight before we can learn to swim; it is no point of practising at the water that is only reaching up to your ankles.

Are you looking at out of the box or inside the box?

From the perspective of a global society these lessons from psychology might be counterintuitive, would we not need to pay attention to vulnerability, to map out and recognize the systemic inequality and suffering that our Western hegemony and destructive economic system is imposing to those exploited?

Yes, collectively, we need to address the historical burden of inequality. Still, answers how to approach that question might be very different from the ways that we think problems are fixed.

Indigenous communities involved in the work of Vanessa’s collective gesturing towards decolonial futures are clear that if relationships are not healed, are not grounded, we will end up more killing and destruction. In contrast to regenerative transformation for the whole of humanity, people will turn inwards, to fight to protect their families and loved ones from the increasing violence. That insight feels right to me.

And indeed, more and more thinkers, artists and activists are paying attention to relationships and what happens in “a liminal space” in between. One of the leaders of this thought is a systems thinker, writer and educator Nora Bateson. What I particularly like in her theory is that instead of searching for something outside the current system “to replace the system” we ought to look inside the system. How we, as warm bodies and intelligent organisms, are in our relationships with other parts of the system. Her concept of warm data is not a map of connections that can be drawn on a piece of paper because it is only perceived when being part of a system and participating in it.

While what is emerging from that thought feels quite blurry at the moment, I’m very excited to participate in a warm data lab process myself. I hope to pen down some reflections from experience in my next blog. Stay tuned.

0 notes

Text

Cultivating skills for resilience PART II

Some resilience skills are for keeping together what already is, while some are for moving forward to what could be. This is a second part of the blog I started yesterday if you did not read the first go here.

Photo by Julietta Watson on Unsplash

Lessons from the decolonial movement – composting

This next part is a surprise also for me. To be honest, I was always wondering why “composting” has such a central role in the vocabulary and practises promoted by the decolonial futures movement. However, the need for active composting (or unlearning) does not look like an alien concept at all when I connect it to the regeneration and resilience in biological systems. A biological system has to be able to bring back its elements to non-living particles (carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorous etc.), that then can, again, be taken back as a raw material for a new life.

Biological processes in our bodies are part of continuous nutrient cycles – without us even realizing – we are renewing the matter that we are. Living organisms are full of particles from the past, particles which have given life for many other earlier living organisms or provided form for non-living things. As we live, we also continue to decay. These two processes, decay, and growth are not opposite but happening simultaneously. The ability to compost is a prerequisite for the ability for renewal. Otherwise, literally, we would bury ourselves to our own shit!

Earlier definitions of resilience and transformative resilience in this blog series describe two pathways to respond to a crisis.First is trying to get the system back in equilibrium.

This response integrates learning from the crisis, which helps the system to be better prepared for similar shocks in the future. Essentially this is resilience to recover quicker and with less damage. The resilience skills are required when the objective of the action is to ensure the continuity of the system.

The second response is related to skills we need when the system itself is unsustainable, oppressive and damaging. The objective here is not to reform the existing system to be better prepared for similar shocks in the future, but using the crisis itself as an opportunity for new patterns to emerge outside the current system. These skills I call transformative resilience skills.

It is becoming more and more clear to me that an active process of unlearning (composting) is necessary for cultivating transformative resilience skills. Self-renewal in biological systems means that new is not just built on top of the old, but the former matter is actively decomposed to make space for new. Ultimately, getting rid of the patterns of behaviour and thought that hold the old system in place.

Higher Education Otherwise calls these skills ‘composting’. ”Noticing, interrupting and ‘composting’ harmful desires, and supporting others to do the same, with patience, humility, critical generosity, and compassion.” I believe this is something that deserves to be more central in the resilience dialogue. Inventing the right ideas is a big part of better though and better action and processes of composting and unlearning, while not new ideas, deserve more attention in human-made systems. According to the barefoot collective, one of my favourite learning communities, unlearning: letting go for a change - is becoming open for different ways to get things done. Not assuming that the ways I have learned to be will be the right way for me forever.

Before concluding this blog, I read some more about resilience in psychology and neuroscience. My reflections in PART III posted tomorrow.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultivating skills for resilience PART I

Some resilience skills are for keeping together what already is, while some are for moving forward to what could be. My latest blog was about the terminology of resilience and transformative resilience. In this follow-up, I continue the resilience theme with further exploration in identifying skillsets needed to embody resilience.

While resilience skills do not belong to one or another system, we (still) live in a world of separation. As a result of this, it is practical to look at the resilience from different perspectives. I am asking a question: what skills or traits for resilience are in different disciplines?

I let the reading lead and made associations along the way. As a biologist, it was easy to start the exploration from biology, which then brought me to think about a familiar concept of self-renewal from a new perspective and associate it with the decolonial movement. Next, I read some journal articles on psychology and neuroscience, finishing my exploration to something new that I am already anticipating to participate. While the blog post became longer than I expected, I have divided it into three parts. Let’s start.

Photo by Neslihan Gunaydin on Unsplash

Resilience biology

Biological systems embody resilience through redundancy and variation. Duplicate forms are essential for survival; when one part of the system (or a living organism) does not make it through the storm, there is another part of the system that survives.

Diversity also enhances change for survival when environmental conditions change in an ecosystem. Diversity helps to create a self-regulating system, where some of its’ parts respond to environmental changes, which affect some of its’ parts adversely. Their role is to substitute pieces impacted by the adversity, or suppress the impact of the disturbance, and bring the system back to equilibrium or back to its functioning state.

Likewise, the processes and systems in a living organism (or ecosystem) are dispersed and not located exclusively together to avoid damage that puts the system in halt when one of its parts is damaged. A systemic decentralization, where multiple units with each other work independently, allows ecosystem or organism to recover after a crisis.

For instance, agroecosystems that are based on single species are fragile for environmental disturbances compared to a diverse farming system based on agroecology. In a monoculture, one pest can wipe away the entire crop, which leads to food crises. At the same time, diverse agroecological systems offer a variety of staple crops that can substitute the loss in case one crop is lost.

Furthermore, in a diverse system, where different parts are in constant communication through food chains and nutrient cycles, infestations might not be able to develop as an outbreak. Parts of the system that feed on a particular pest will simply increase in numbers naturally, bringing down the population size of the parasite before the infestation can spread.

We have applied the resilience biology in the agricultural systems. Unfortunately, some of this wisdom is lost in the era of industrial farming. Nevertheless, the multiple crises are starting to shake the trust in globalized food production. Many local initiatives are exploring how to bring resilience to agriculture. A people’s pluriverse, an exciting book detailing transformative initiatives (not only in agriculture), outlines Nayakrishi Andolon, or the New Agriculture Movement, led by farmers involving more than 3000,000 various household ecological units in Bangladesh. The movement uses ‘seed’ as a central element to demonstrate continuity and history. The Nayakrishi Andolon is a wonderful example of combination of local wisdom, scientific knowledge and bio-spiritual potential of human communities in the real material world to live in dynamic relationship with the other living and non-living parts of the ecosystem; realizing a regenerative local agroeconomy in practise.

There is still one more remarkable skill, which embodies the resilience of biological systems, the capacity of living organisms for self-renewal. Organisms and living systems need capacity for self-renewal at all times to maintain their form or function. However, the self-renewal characterized in the regenerative capacity of an ecosystem is particularly crucial when the ecosystem needs to repair the damage caused by the adversity. Self-renewal is truly an amazing skillset from a biological system, often forgotten when talking about adaptive capacity and risk preparedness in the context of land use or disaster risk management. A self-renewal requires letting go, getting rid of the stuff that does not serve the system, before assembling the new pieces for the service of life.

Self-renewal in human-made systems helps to build regenerative interactions that do not destroy, belittle and oppress, but nurture, hold and repair. That’s where I intend to go next. Read more about my reflections in reading materials related to the decolonial movement in PART II of the blog, posted tomorrow.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Resilience or transformative resilience?

Photo by Stanislav Kondratiev on Unsplash

Past days I have been exploring the concept of resilience in preparation for my new work. While resilience has been a buzzword of a development community already for the past decade, it is a relatively new concept for me. Can resilience describe a pattern that helps us to navigate the stormy waters in the time of a profound change?

It seems that in its’ pure form, the definition of resilience is quite clear. According to C.S. Holling, most sited in the resilience science, resilience is the ability of a system to maintain its structure and patterns of behaviour in the face of disturbance. What is troubling in this definition is that it describes a capacity of a system to return to “back to its’ normal state”. Essentially this definition tells us that resilient communities can absorb the shock, and then continue with the business as usual. They can cope with the disturbance and bounce back to their earlier form and patterns of behaviour.

This definition will not be enough if we want to describe the process of change required to transform the oppressive and exploitative systems. What if in the face of a crisis a resilient community does not want to go back to normal, and the crisis itself opens the door to better ways of being? New-found forms of interacting in the interconnected system arise from the cracks of the crumbling and decaying structure; both with other people and with the other living and non-living members of an ecosystem.

If there is any way forward to tackle the multiple crises humanity is facing just now, the resilience needs to link to the adaptive capacity of a social-ecological-systems to evolve in times of crisis. A more recent definition of climate resilience is already close to the meaning of adaptation. It thus carries within the ability to adapt and change the structure and patterns, and not only describe the strength of a system to bounce back from adverse conditions.

Interestingly, while doing my readings on resilience, I also found out that it is a useful word in the political arena when discussions about the climate emergency are highly politicised. According to an article in the bulleting of the atomic scientists, the term resilience has become a code word for a “climate change”, under which those who still care can push for policies that bring forward the mitigation and adaptation plans required.

Understandably, resilience is a relevant term, but how we can determine what is resilience and what is adaptation or vulnerability? After reading some more articles on the topic, I conclude that it is easier to describe the essential capacities we need to sustain the life on earth in times of crises with two separate terms: resilience and transformative resilience. If resilience means the condition of being able to survive during an adverse situation and/or the ability to recover from such an event, then transformative resilience is the ability of not only to survive and recover but also to use the event itself as an opportunity for change.

As in most processes of life, rather than two opposite possibilities to respond to a crisis, the adaptive capacity is a continuum between resilience and transformative resilience—a delicate dance between two possible strategies to face the adversity. In one hand, we need resilience to tolerate the change to maintain the equilibrium and conditions required to nurture life. In the other hand, we need transformative resilience to use the adverse conditions as a lever towards a different kind of a system; a system even better suited for serving all of its’ interdependent parts.

What is clear is that more crises are coming. If so, we need to practice resilience, individually and in a community. In the next blog, I intend to explore what it could mean in practice to cultivate the capacity for resilience and/or for transformative resilience. Stay tuned.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tärkeintä on välittää muista ihmisistä: systeemiälykäs yrittäjä raivaa polkuja kohti parempaa maailmaa

Photo by Craig Ren on Unsplash

Maaliskuun viimeisenä päivänä kuulen Sampsa Fabritiuksen puhuvan systeemiälykkäästä yrittäjyydestä ystäväni Evan järjestämässä webinaarissa. Jokin esityksessä kolahtaa, sitten putoan linjoilta, internet on iltapäivisin ruuhkautunut. Kun saan Sampsan langan päähän pari viikkoa myöhemmin, hänellä on kotikoulun koordinointi meneillään. Kuulen lasten äänet keskustelun taustalla. Siinä arkisen tohinan keskellä Sampsa kertoo lisää omasta diplomityöstään, joka käsittelee yrittäjyyden neljättä vallankumousta; sitä kuinka yrittäjät parantavat maailmaa.

Haastattelujen pohjalta koottu aineisto osoittaa, että yrittäjät, jotka näkevät yritystoiminnan tapana parantaa maailmaa ovat kaikki tulleet samaan tulokseen: "tärkeintä on välittää muista ihmisistä". Tämä saattaa vaikuttaa itsestään selvältä, mutta haastatelluille yhteisen pyrkimyksen sovittaminen muihin yritykselle, ja yrittäjälle itselleen, tärkeisiin tavoitteisiin ei ehkä olekaan aivan yksinkertaista.

Systeemiälykkään yrittäjän päämäärä on muuttaa maailmaa yrittäjyyden keinoin. Sampsan tutkimuksen mukaan tämä vaatii ainakin hyvää itsetuntemusta, erinomaisia vuorovaikutustaitoja ja päämäärähakuisuutta. Näin toimiessaan yrittäjä on myös valmis kritisoimaan olemassa olevia sääntöjä ja käytäntöjä, jos ne eivät edistä yritykselle asetettua päämäärää.

Yrityksen vakaus perustuu sille, että systeemi, jota osa yritys on, toimii ennakoidulla tavalla. Kun järjestelmään tulee odottamaton häiriö, yritys voi menettää edellytykset kannattavaan liiketoimintaan. Systeemiälykäs yrittäjä kokee päämääräkseen maailman parantamisen ja etsii tapaa yhdistää päämäärän ja yrityksen taloudelliset intressit. Taloudellinen menestys luo toimintaedellytyksiä maailman parantamiselle.

Koronakriisi on hyvä esimerkki siitä, miten häiriö systeemissä suistaa yrityksiä raiteiltaan. Silti häiriöitä myös tarvitaan, koska juuri kriisien aikana näemme selkeämmin ne arvoketjut, joihin liiketoiminta perustuu. Kun ongelma koskettaa monia, ja tapahtuu yhtäkkiä, on helpompi huomata systeemin haavoittuvuus. Tämä myös paljastaa sosiaalisia ongelmia ja luonnonvarojen riistoa ylläpitävät ja synnyttävät rakenteet. Kriisien aikana rajapinnoista nousee käsitteitä valtavirtaan ja avautuu uusia mahdollisuuksia muuttaa käytäntöjä, joita ilman kriisiä kukaan ei olisi uskaltanut kyseenalaistaa.

Systeemiälykkään yrittäjän rooli on tehdä käytäntöjä kyseenalaiseksi; tarkastella ja pohtia miten yritysmaailmalle tutut periaatteet ja tavat edistävät (tai estävät) oman päämäärän saavuttamisen. Näin yrittäjä kohtaa haasteita, joista normatiivisen yrittäjän ei tarvitse välittää. Rakenteita vastustaessaan yrittäjä voi myös samalla kyseenalaistaa oman yrityksensä olemassaolon. Siksi systeemiälykäs yrittäjä voi olla kummajainen, joka tallaa uusia polkuja yritysmaailmalle tuttujen reittien sijaan.

Photo by Andrew Buchanan on Unsplash

Yrittäjä muotoilee maailmaa kohtaamalla toiset ihmiset

Tämän päivän yrittäjän työkalupakkiin kuuluvat asiakaslähtöisyys, palvelumuotoilu, arkkityypit ja elämykset. Yrittäjä toimii tarjotakseen kuluttajille palveluita ja tuotteita, joita he tarvitsevat; palveluja ja tuotteita, jotka luovat ”ratkaisuja” asiakkaiden ongelmiin (ja joista he ovat valmiita maksamaan). Näistä lähtökohdista yrittäjä työskentelee tarpeiden tyydyttämiseksi. Samalla hän voi myös kurkistaa pintaa syvemmälle ymmärtääkseen mistä hänen kohderyhmänsä voisi olla kiinnostunut; mitä he tietämättään ja tiedostamattaan tarvitsevat ja haluavat. Sen jälkeen yrittäjä pohtii miten tuotteistaa ja tarjota nämä pinnan alla kytevät haaveet, ja tarjoilla ne mielenkiintoa herättävässä henkilökohtaisessa kääreessä. Tuotteet, palvelut ja elämykset, jotka yrittäjä kohderyhmälleen muotoilee luovat ”parempaa elämää” asiakkaille.

Mutta riittääkö tämä tarina yrittäjästä asiakkaiden ongelmien ratkaisijana ja elämysasiantuntijana? Voiko yrittäjä sukeltaa syvälle ja vastustaa sitä mitä asiakas haluaa tai tarvitsee? Voiko systeemiälykäs yrittäjä olla osa muutosprosessia, jossa kyseenalaistamme sen mitä yksilöinä ja yhteiskuntana olemme?

Systeemiälykäs yrittäjä ymmärtää, että meillä on monia rooleja, olemme asiantuntijoita, yrittäjiä, älykköjä, perheenäitejä ja isiä, lapsia, sisaruksia, ystäviä, kodinhoitajia, asiakkaita, myyjiä, opiskelijoita ja opettajia. Olemme ihmisiä, eläimiä, suomalaisia ja maailman kansalaisia. Kaikkia näitä erikseen ja yhtä aikaa; kaikkia näitä yksin ja yhdessä toisten kanssa. Olemme osa verkostoa, johon sisältyy paljon enemmän oletuksia ja toiveita, kuin ne säännöt, käytännöt ja tulosvastuu, jota yrityksemme, ja yritysmaailma meiltä odottaa. Systeemiälykäs yrittäjä osaa tarkastella maailmaa monesta eri perspektiivistä. Yrittäjyys on vain yksi näistä.

Pari viikkoa puhelun jälkeen, kävelen lähimetsässä ja kuuntelen The Gloaming podcast sarjasta Norah Batesonin kokemuksia the Warm Data Lab yhteisötyöpajoista. Norah kertoo transkontekstuaalisesta lähestymistavasta (transcontextual approach). Näistä ajatuksista rakennan sillan keskusteluun systeemiälykkäästä yrittäjästä Sampsan kanssa. Tämän oivalluksen valossa, Sampsan diplomityön haastattelujen tulos ”tärkeintä on välittää muista ihmisistä” on loistava yhteenveto. Vaikka meillä yrittäjinä ei ole tarkkaa kuvaa tai suunnitelmaa siitä miltä ”parempi maailma” näyttää, saati siitä miten sinne pääsee, rakennamme sitä tässä ja nyt.

Myös yrittäjälle tulevaisuuden visioita tärkeämpää on se, miten kohtaamme ihmiset, elollisen ja elottoman luonnon tässä hetkessä. Millä mielellä ja asenteella toimitamme arkisia askareita ja työtehtäviä, joita meiltä pyydetään tai jotka valitsemme. Miten suoritamme ne velvollisuudet, joita meillä on, ja mitä ajattelemme niitä tehdessämme. Jos emme yrittäjinä tiedä ”mitä” meidän pitäisi tehdä, voimme keskittyä siihen, ”miten” sen teemme. Lopulta muutosvoima ei ehkä olekaan yksilöissä, yrityksissä ja rakenteiden sisässä vaan siinä mitä on niiden välissä.

0 notes

Text

Resistance

The moment I met two Eteläpuisto activists in the public library of Tampere was beautiful. The sun was pouring in through the large windows, but the light that announced the arrival of spring also carried a weight of time. Our conversation was rich, with nuances of the past and hopes for the future, not visible in an ordinary day. Because of the worldwide pandemic, a new reality was only then starting to shape its collective presence in the consciousness of the City of Tampere.

“A growing city needs dense urban construction; people need houses, and the city needs people. It is environmentally friendly to build compact cities. High-rise buildings are a symbol of progress!” This has been a dominant storyline in the City of Tampere for the past 10 years. However, an alternative narrative is building up, slowly but with determination.

Eteläpuisto is the oldest park in Tampere. It is also a quiet battleground marked with lines and changes in architects’ drawings, city planning documents, maps and court decisions. These events mark the five-page list of bullet points I received from the activists outlining the struggle to protect and develop the park. Eteläpuisto activists have a goal. They believe that the park has a history that is worth preserving and a future that is worth fighting for.

Glamorous banderols or flashy slogans do not support the resistance of these activists to unrestrained change. Their days are spent mostly waiting, staying alert and being ready when action is required.

This is a story of purpose, friendship and perseverance. First, I learn about a tasteless remark about “overactive pensioners” published in a local newspaper, Aamulehti, in 2015. This ill-fitting line sparked outrage and brought more revolutionaries to the ranks of the resistance, despite its initial intentions.

Then we moved on to discuss the 2017 communal elections. The group demonstrated the reality behind architects’ drawings by marking the trees in the park destined to be cut down. This changed public opinion and re-shaped the political debate. Before plans could be executed, they launched a social media campaign to list all decision-makers in favour of the change. Most politicians changed their minds before the election.

I was amazed to see their spirits were not dampened by the numerous delays in preparing for a comprehensive plan for the park (and its advancement). Friendship has united them, but it is wisdom from the past that has given them the strength to continue. They are old enough to know that similar battles have been won, even in this city, and even against all the odds. They are determined to go on, no matter how old they might be when the struggle ends.

It has been a long battle, fought since 2014, but luck may be on their side once more. With the delays that have frustrated them, they have been able to buy enough time to have more people than ever embrace their goals. On November 25, 2019 the group handed over petition directed to the City Council with 16,102 signatures to preserve the park.

With the global crises, such as the pandemic we are facing now, Mother Earth has brought nature back to the centre of our attention–not as something to conquer, but as something that demands our respect.

Eteläpuisto activists know that losing this place, so central to the history of the city, would undermine its promise for future generations. They know that we need cities to embrace green areas and grow around them.

If cities we build alienate us from the environment, we will not have a chance to make peace with it. It is time to respect Eteläpuisto, the green heart of the city.

Thank you, Maisa Heiskanen and Otto Siippainen. More information https://etelapuisto.fi/

This blog post was preapred for Interrogativa https://interrogativa.home.blog/

Photo by Tatiana Rodriguez on Unsplash

0 notes

Text

What’s next? – PART 5 Solidarity

This week I saw a film of Ken Loach: Land and Freedom (Tierra y Libertad) in a European movie evening organised in Tampere. A lead actress of the film, Rosana Pastor, joined the event and told the audience about the process of casting the film 25 years ago in a small village in Spain, where the cast had just met to celebrate the anniversary of the film.

It was a special moment of intimacy, to listen Rosana’s recollections from making the Land and Freedom and how it had created a strong bond between the group of actors (some professional, some just carefully handpicked passers-by, who had demonstrated the specific qualities the director was looking for in this particular film). The cast playing the militants thus had lived the moment, not acted upon it. They had the freedom to express their creativity and trust their feelings when creating the scenes that unfolded in front of them.

Ken Loach, the 83 years old filmmaker, has been named as the consciousness of the Europe, and his movies from freedom fighters and revolutionaries to the gig economy and consumer culture tells a human-size story of Europe. Even his earlier movies from the 60’s are more than relevant in portraying the social oppression, exploitation and discrimination, which can be overcome only by acts of unity and care, a remarkable tribute to solidarity.

Photo by Bekky Bekks on Unsplash

0 notes

Text

What’s next? – PART 4 Public space

I have in my email a quote from a philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt "The central political activity is action.” While means of the political action vary, actions need a public space to influence and shape the world. Space is part of the action and action shapes the space. Be it a speech, story, article, dialogue, debate, performance or demonstration; as important as the action itself, is the context of this action, a public space.

It is perhaps an understatement that our democracy is suffering within the existing public space. Our public spaces are narrow and competitive. There are simply not enough opportunities for a healthy engagement that encourages diversity and creativity. A political debate is often grounded on rivalry and belittlement. A political space becomes a battleground of big egos, rather than a debate on the real alternatives and reasons behind our decisions.

Therefore, I am evermore grateful to people like Uffe Elbaek, who can break the norm, and create an alternative space for healthy political action. We need parties and political platforms, spaces like the Alternativet, and its many branches, to realise what a future of politics could be. Not exercising democracy only through an elected representative but as the form of human social life.

When citizens’ laboratories, assemblies and other forms of engagement create a public space for a vigorous political debate and collaborative action, across the traditional party lines, people realise that they, as citizens of the planet earth, have a right and responsibility to care for the public good. It is a public space that can bring out our unlimited capacity and recognise that we need everyone, yes everyone, to contribute to the future building.

Photo by Phil Hearing on Unsplash

0 notes