#Battle of Salamis

Text

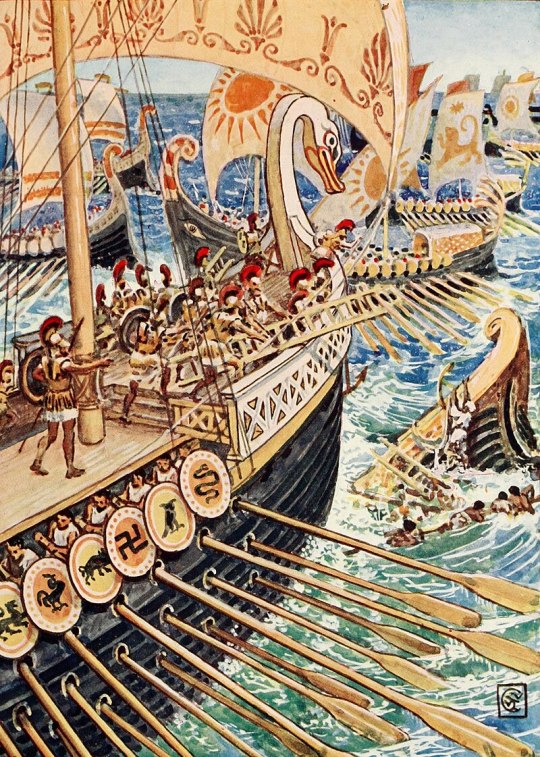

Battle of Salamis by Wilhelm von Kaulbach

#battle of salamis#naval battle#ancient#art#greece#greek#greek city states#achaemenid empire#persian empire#salamis#themistocles#king xerxes#eurybiades#artemisia#ariabignes#tetramnestos#achaemenes#damasithymos#xerxes#artemisia i of caria#xerxes i of persia#persia#persian#athenian#spartan#history#europe#mediterranean

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Themistocles’ Exhortation before Salamis: On Herodotus 8.83

Vasiliki Zali "Themistocles’ Exhortation before Salamis: On Herodotus 8.83", Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 53 (2013) 461–485

Dr. Vasiliki Zali, Lecturer in Classical Studies and Departmental Lead for Widening Participation and Outreach Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool (https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/archaeology-classics-and-egyptology/staff/vasiliki-zali/ )

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victory at Sea

Anthologia Palatina 6.215 = Simonides

Note: According to Plutarch, Diodorus was a Corinthian trierarch (trireme captain) at the battle of Salamis.

These shields, taken from their foes the Medes,

The sailors of Diodorus dedicated

To Leto – monuments of the fight at sea.

ταῦτ᾽ ἀπὸ δυσμενέων Μήδων ναῦται Διοδώρου

ὅπλ᾽ ἀνέθεν Λατοῖ μνάματα ναυμαχίας.

Battle of the Combined Venetian and Dutch Fleets against the Turks in the Bay of Foya, 1649, Abraham Beerstraaten, 1656

#classics#tagamemnon#Greek#Ancient Greek#Greek language#Ancient Greek language#translation#Greek translation#Ancient Greek translation#poem#poetry#poetry in translation#ancient history#Ancient Greece#Greek history#Ancient Greek history#Persian Wars#Greco-Persian Wars#Battle of Salamis#epigram#dedicatory epigram#Simonides#couplet#elegiac couplets#Anthologia Palatina#Palatine Anthology#Anthologia Graeca#Greek Anthology#Abraham Beerstraaten

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Salamis Was Fought During the Persian Wars (499 to 449 BCE). The Struggle Saw the Out-Numbered Greeks Defeat the Larger Persian Navy in One of the Greatest Naval Battles in History. September 23, 480 BCE

Image: The Battle of Salamis, 19th Century illustration. (Public Domain.)

On this day in history, September 23, 480 BCE, the Battle of Salamis was waged during the Persian Wars (499 to 449 BCE). The struggle at Salamis witnessed the out-numbered Greeks defeating a larger Persian navy in one of the greatest naval battles in history. The war had seen the Greeks driven south and Athens seized.…

View On WordPress

#480 BCE#Battle of Salamis#event & history#History Daily#military history#Persian Wars (499 to 449 BCE)

0 notes

Text

BG3 Companions: Do we really have to look in every barrel and burlap sack we find? It takes so long.

Tav: YES! Do you know how much food you guys eat? And now we have an Owlbear to feed? Honestly, I kind of wish more of you were vampires, then at least I wouldn't have to carry all these potatoes.

#BG3#Baldur's Gate 3#Astarion feeds himself in battle and I love that for him#Gale at least is pulling his weight by cooking#The rest of you better carry these fifteen bottles of Ithbank and seven salamis we looted from the goblins#Or I'm leaving you behind#Qd

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

old man .

#aib#animated inanimate battle#aib salami#aib telescope#had fun with brushes here#I just realised I . posted these in the wrong order whoops 😭 excuse the edit here

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round One

This poll is for Amy/Sally vs Amy/Sally/Sonic, both ships from the Archie Comics

All ships included were submitted to us. This tournament does not accept insults towards either ship - use propaganda to uplift your fave, not put down the opponent

27 notes

·

View notes

Link

Each day brings with it its measure of joy or travail. The noise of life hums along and practicalities absorb the attention of most of us, enough so that the profundity of alterations introduced by the covid operation may not quite be appreciated. Indeed, I cannot myself come to comprehend the depths and breadth of the iniquity visited upon us, though I can perceive the stigmata. It bores me to have to repeat the litany of abuse to which we have been subjected – the lockdowns, masks, jab mandates and apartheid, the residual divisions between friends and family, the cheerful … Continue reading →

0 notes

Text

Despite Sparta’s reputation for superior fighting, Spartan armies were as likely to lose battles as to win them, especially against peer opponents such as other Greek city-states. Sparta defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War—but only by accepting Persian money to do it, reopening the door to Persian influence in the Aegean, which Greek victories at Plataea and Salamis nearly a century early had closed. Famous Spartan victories at Plataea and Mantinea were matched by consequential defeats at Pylos, Arginusae, and ultimately Leuctra. That last defeat at Leuctra, delivered by Thebes a mere 33 years after Sparta’s triumph over Athens, broke the back of Spartan power permanently, reducing Sparta to the status of a second-class power from which it never recovered.

Sparta was one of the largest Greek city-states in the classical period, yet it struggled to achieve meaningful political objectives; the result of Spartan arms abroad was mostly failure. Sparta was particularly poor at logistics; while Athens could maintain armies across the Eastern Mediterranean, Sparta repeatedly struggled to keep an army in the field even within Greece. Indeed, Sparta spent the entirety of the initial phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), failing to solve the basic logistical problem of operating long term in Attica, less than 150 miles overland from Sparta and just a few days on foot from the nearest friendly major port and market, Corinth.

The Spartans were at best tactically and strategically uncreative. Tactically, Sparta employed the phalanx, a close-order shield and spear formation. But while elements of the hoplite phalanx are often presented in popular culture as uniquely Spartan, the formation and its equipment were common among the Greeks from at least the early fifth century, if not earlier. And beyond the phalanx, the Spartans were not innovators, slow to experiment with new tactics, combined arms, and naval operations. Instead, Spartan leaders consistently tried to solve their military problems with pitched hoplite battles. Spartan efforts to compel friendship by hoplite battle were particularly unsuccessful, as with the failed Spartan efforts to compel Corinth to rejoin the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League by force during the Corinthian War.

Sparta’s military mediocrity seems inexplicable given the city-state’s popular reputation as a highly militarized society, but modern scholarship has shown that this, too, is mostly a mirage. The agoge, Sparta’s rearing system for citizen boys, frequently represented in popular culture as akin to an intense military bootcamp, in fact included no arms training or military drills and was primarily designed to instill obedience and conformity rather than skill at arms or tactics. In order to instill that obedience, the older boys were encouraged to police the younger boys with violence, with the result that even in adulthood Spartan citizens were liable to settle disputes with their fists, a tendency that predictably made them poor diplomats.

But while Sparta’s military performance was merely mediocre, no better or worse than its Greek neighbors, Spartan politics makes it an exceptionally bad example for citizens or soldiers in a modern free society. Modern scholars continue to debate the degree to which ancient Sparta exercised a unique tyranny of the state over the lives of individual Spartan citizens. However, the Spartan citizenry represented only a tiny minority of people in Sparta, likely never more than 15 percent, including women of citizen status (who could not vote or hold office). Instead, the vast majority of people in Sparta, between 65 and 85 percent, were enslaved helots. (The remainder of the population was confined to Sparta’s bewildering array of noncitizen underclasses.) The figure is staggering, far higher than any other ancient Mediterranean state or, for instance, the antebellum American South, rightly termed a slave society with a third of its people enslaved.

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm curious if you have any thoughts on weaponry in an armada, specifically in settings where there are no guns. Would it make sense for an armada to exist without guns and the like, or what weapons would they specialize in instead? (I guess this kind of leads into the question of "What weapons are best when fighting on a ship if there are no guns in the world?" if that would make it simpler.)

I hope this doesn't come as a major surprise, but naval combat is older than gunpowder, so this is more of a historical question than you seem to expect.

In fact, piracy is a practice that dates back to, at least, The Bronze Age, with pirates preying on Greek shipping in the Mediterranean.

While it's not an exact answer to your question, the main answer is probably a lost technology known as Greek Fire. This was a combustible fluid that could be sprayed onto enemy vessels, burning them to the waterline.

Even before the invention of Greek fire, setting your foes ships ablaze was already a popular tactic in naval warfare. Beyond that boarding parties, and ramming using a reinforced bow were also staples in the Greek world.

If you want a specific example to look at, the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC might be a good choice. It's certainly a classic example.

I'm less familiar with the state of naval combat in the first millennium, though again, that is simply historical research. (Worth noting that, in spite of the Hellenic world making extensive use of setting enemy ships on fire, Greek fire proper was a Byzantine technology, and wouldn't be developed until the 7thcentury AD.)

If you're looking at a fantasy setting, then that will probably lapse into a worldbuilding question, and an examination of the technologies available to your characters. But, yeah, in the real world, people were killing each other on the water long before we had guns and cannons.

-Starke

This blog is supported through Patreon. Patrons get access to new posts three days early, and direct access to us through Discord. If you’re already a Patron, thank you. If you’d like to support us, please consider becoming a Patron.

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artemisia, who moves me to marvel greatly that a woman should have gone with the armament against Hellas; for her husband being dead, she herself had his sovereignty and a young son withal, and followed the host under no stress of necessity, but of mere high-hearted valour. Artemisia was her name; she was daughter to Lygdamis, on her father's side of Halicarnassian lineage, and a Cretan on her mother's. She was the leader of the men of Halicarnassus and Cos and Nisyrus and Calydnos, furnishing five ships. Her ships were reputed the best in the whole fleet after the ships of Sidon; and of all his allies she gave the king the best counsels. The cities, whereof I said she was the leader, are all of Dorian stock, as I can show, the Halicarnassians being of Troezen, and the rest of Epidaurus.

— Herodotus VII.99.

#artemisia#herodotus#history#battle of salamis#ancient greece#ancient greek#ancient#greek#greece#europe#persia#persian#salamis#mediterranean#navy#naval battle#naval warfare#naval combat

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil lamp in shape of a greek warship, end of the 5th cent. BC

The oil lamp with the inscription ΙΕΡΟΝ ΤΗΣ ΑΘΗΝΑΣ (Sanctuary of Athena) was discovered inside the Erechtheion, Acropolis. Its form is linked to the celebration of the Panathenaia and the worship of Athena Polias, whose wooden cultic statue (xoanon) was kept in the eastern part of the Erechtheion.

During the last day of the celebration, the Athenians offered to the xoanon a new peplos, which, after the victory at Salamis, was transported hung like a sail on the mast of a warship -most possibly on one of the victorious triremes of the naval battle– which moved on wheels. The lamp possibly reproduces the features of this ship.

170 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can I offer Fake a nice slice of salami in these trying times?

you offer SLOMMY

Your friendship with fake peppino has increased. You may now use him as a special summon in battles

396 notes

·

View notes

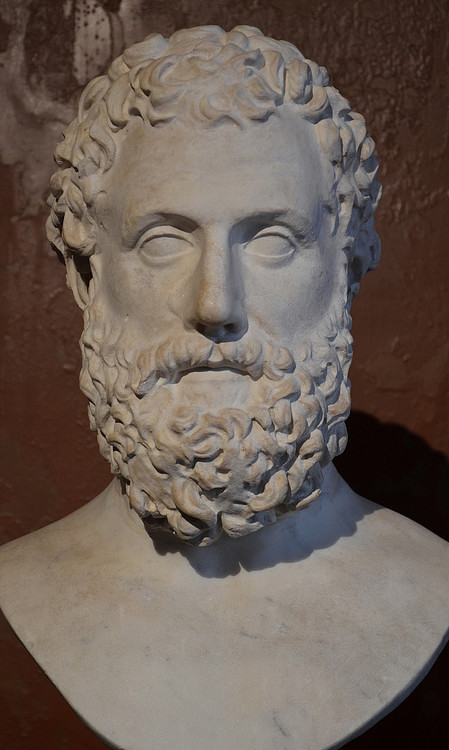

Photo

Aeschylus

Aeschylus (c. 525 - c. 456 BCE) was one of the great writers of Greek Tragedy in 5th century BCE Classical Athens. Known as 'the father of tragedy', the playwright wrote up to 90 plays, winning with half of them at the great Athenian festivals of Greek drama. Perhaps his most famous work is Prometheus Bound which tells the myth of the Titan punished by Zeus for giving humanity the gift of fire. All of his surviving plays are still performed today in theatres across the world. An innovator of the genre, Aeschylus is said to have described his work as 'morsels from the feast of Homer'.

Aeschylus' Life

5th century BCE Athens was blessed with three great tragedians: Aeschylus, Euripides (c. 484 - 407 BCE), and Sophocles (c. 496 - c. 406 BCE). The senior of the three, Aeschylus was born in Eleusis in c. 525 BCE. Aeschylus' father was Euphorion, and ancient sources claim the family belonged to the aristocracy. Living through the Persian wars, Aeschylus almost certainly participated in such famous and decisive battles as Marathon and Salamis. His brother Kynegeiros was killed in the former battle and his other sibling Ameinias fought at the latter. Aeschylus' epitaph, said to have been self-penned, stated nothing of his success as a playwright but only that he had fought at Marathon. These experiences and the transformation of Athens' political structure as it embarked on the road to democracy greatly influenced the playwrights' work.

Other snippets of biography, which have survived from antiquity, reveal that Aeschylus was once prosecuted for revealing details of the secret Eleusinian mysteries cult but managed to prove his innocence. Sometime after 458 BCE Aeschylus travelled to Sicily, visiting Syracuse at the invitation of Hieron I, and around 456 BCE he died on the island in the town of Gela. Aeschylus' plays were already recognised as classics and their public performances were given particular privileges. His son Euphorion and nephew Philocles both became noted dramatists in their own right.

Continue reading...

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

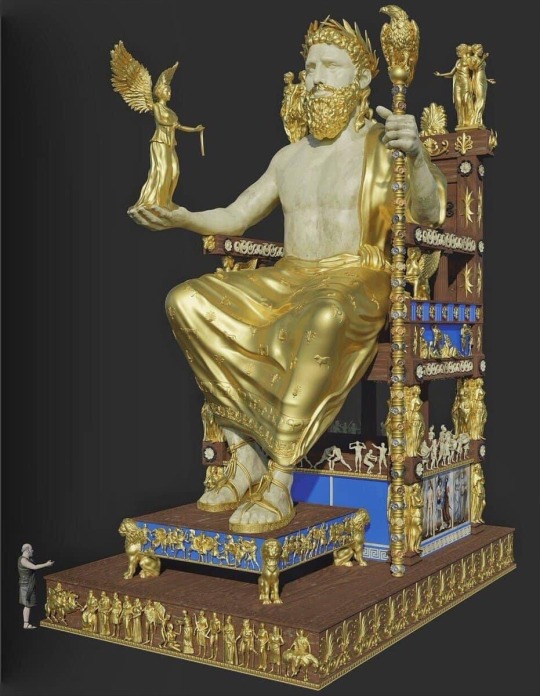

The monumental Statue of Zeus at Olympia in Greece was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Created in the 430s BCE under the supervision of the master Greek sculptor Phidias, the huge ivory and gold statue was bigger even than that of Athena in the Parthenon. Worshipped by pilgrims from across the Mediterranean, the statue inspired countless imitations and defined the standard representation of Zeus in Greek and Roman art in sculpture, on coins, pottery, and gemstones. Lost in later Roman times following its removal to Constantinople, Phidias' masterpiece captivated the ancient world for 1,000 years and was the must-see sight for anyone who attended the ancient Olympic Games.

The statue of mighty Zeus was over 12.4 m (41 ft) high and represented the god seated on a throne. It was bigger even than Phidias' Athena Parthenos in Athens. The Zeus statue, like Athena, was chryselephantine, that is a combination of gold and ivory over a wooden core, with the god's skin (face, torso, arms and legs) being in ivory and his beard, robes, and staff rendered in brilliant gold, applied in hammered sheets. Fine details were picked out using a wide variety of materials: silver, copper, glass (for the decorative lilies of the god's robes), ebony, enamel, paint, and jewels. The clay moulds discovered in Phidias' workshop for a similar statue suggest that it was first erected there in pieces - the size of the workshop is exactly the same dimensions as the inner cella of the temple - and then reassembled at its final destination. The wooden core could not have been fully sculpted or the moulds would have been unnecessary to shape the outer gold pieces.

Zeus' throne - made using ivory, ebony, and gold, and encrusted with glass and gems - was embellished with relief sculpture depicting a wide range of figures from Greek mythology, many of which were considered the offspring of Zeus. There are the Graces (Charites), the Seasons (Horae), various Nikes, sphinxes, Amazons, and the children of Niobe. The screens between the legs of the throne were painted by Phidias' brother Panaenus (Panainos) and depicted the Labours of Hercules, Achilles with Penthesilea, Hippodamia with Sterope, Salamis, and scenes of Greece. The god rested his feet upon a footstool which was decorated with a battle scene involving Theseus fighting Amazons (Amazonomachy).

209 notes

·

View notes