#Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Text

In the darkest chapter of German history, during a time when incited mobs threw stones into the windows of innocent shop owners and women and children were cruelly humiliated in the open; Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a young pastor, began to speak publicly against the atrocities.

After years of trying to change people’s minds, Bonhoeffer came home one evening and his own father had to tell him that two men were waiting in his room to take him away.

In prison, Bonhoeffer began to reflect on how his country of poets and thinkers had turned into a collective of cowards, crooks and criminals. Eventually he concluded that the root of the problem was not malice, but stupidity.

In his famous letters from prison, Bonhoeffer argued that stupidity is a more dangerous enemy of the good than malice, because while “one may protest against evil; it can be exposed and prevented by the use of force, against stupidity we are defenseless. Neither protests nor the use of force accomplish anything here. Reasons fall on deaf ears.”

Facts that contradict a stupid person’s prejudgment simply need not be believed and when they are irrefutable, they are just pushed aside as inconsequential, as incidental. In all this, the stupid person is self-satisfied and, being easily irritated, becomes dangerous by going on the attack.

For that reason, greater caution is called for when dealing with a stupid person than with a malicious one. If we want to know how to get the better of stupidity, we must seek to understand its nature.

This much is certain, stupidity is in essence not an intellectual defect but a moral one. There are human beings who are remarkably agile intellectually yet stupid, and others who are intellectually dull yet anything but stupid.

The impression one gains is not so much that stupidity is a congenital defect but that, under certain circumstances, people are made stupid or rather, they allow this to happen to them.

People who live in solitude manifest this defect less frequently than individuals in groups. And so it would seem that stupidity is perhaps less a psychological than a sociological problem.

It becomes apparent that every strong upsurge of power, be it of a political or religious nature, infects a large part of humankind with stupidity. Almost as if this is a sociological-psychological law where the power of the one needs the stupidity of the other.

The process at work here is not that particular human capacities, such as intellect, suddenly fail. Instead, it seems that under the overwhelming impact of rising power, humans are deprived of their inner independence and, more or less consciously, give up an autonomous position.

The fact that the stupid person is often stubborn must not blind us from the fact that he is not independent. In conversation with him, one virtually feels that one is dealing not at all with him as a person, but with slogans, catchwords, and the like that have taken possession of him.

He is under a spell, blinded, misused, and is abused in his very being. Having thus become a mindless tool, the stupid person will also be capable of any evil – incapable of seeing that it is evil.

Only an act of liberation, not instruction, can overcome stupidity. Here we must come to terms with the fact that in most cases a genuine internal liberation becomes possible only when external liberation has preceded it. Until then, we must abandon all attempts to convince the stupid person.

Bonhoeffer died due to his involvement in a plot against Adolf Hitler, at dawn on 9 April 1945 at Flossenbürg concentration camp - just two weeks before soldiers from the United States liberated the camp.

—Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Theory of Stupidity

#politics#dietrich bonhoeffer#republicans#theory of stupidity#donald trump#dunning kruger effect#pedagogy#stupidity#germany#conspiracy theorists#mob mentality#interesting#ethics

846 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Christian fellowship lives and exists by the intercession of its members for one another, or it collapses. I can no longer condemn or hate a brother for whom I pray, no matter how much trouble he causes me. His face, that hitherto may have been strange and intolerable to me, is transformed in intercession into the countenance of a brother for whom Christ died, the face of a forgiven sinner.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, "Life Together: The Classic Exploration of Christian Community"

#catholicism#christianity#works of mercy#spiritual works of mercy#quote#dietrich bonhoeffer#dietrich bonhoeffer quote#pray for the living and the dead#forgive offences

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

We have to consider that most people learn wisdom only through personal experiences. This explains, first, the astonishing inability of most people to take any kind of preventive action—one always believes that he can evade the danger, until it is too late. Second, it explains people’s dull sensitivity toward the suffering of others; sympathy grows in proportion to the increasing fear of the threatening proximity of disaster. There is some justification in ethics for such an attitude: one does not want to interfere with fate; inner calling and the power to act are given only when things have become serious. No one is responsible for all of the world’s injustice and suffering, nor does one want to establish oneself as the judge of the world. And there is some justification also in psychology: the lack of imagination, sensitivity, and inner alertness is balanced by strong composure, unperturbed energy for work, and great capacity for suffering. From a Christian perspective, none of these justifications can blind us to the fact that what is decisively lacking here is a greatness of heart. Christ withdrew from suffering until his hour had come; then he walked toward it in freedom, took hold, and overcame it. Christ, so the Scripture tells us, experienced in his own body the whole suffering of all humanity as his own—an incomprehensibly lofty thought!—taking it upon himself in freedom. Certainly, we are not Christ, nor are we called to redeem the world through our own deed and our own suffering; we are not to burden ourselves with impossible things and torture ourselves with not being able to bear them. We are not lords but instruments in the hands of the Lord of history; we can truly share only in a limited measure in the suffering of others. We are not Christ, but if we want to be Christians it means that we are to take part in Christ’s greatness of heart, in the responsible action that in freedom lays hold of the hour and faces the danger, and in the true sympathy that springs forth not from fear but from Christ’s freeing and redeeming love for all who suffer. Inactive waiting and dully looking on are not Christian responses. Christians are called to action and sympathy not through their own firsthand experiences but by the immediate experience of their brothers, for whose sake Christ suffered.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906 – 1945), Are We Still of Any Use?, from: Letters and Papers from Prison; An Account at the Turn of the Year 1942-1943

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morning Prayer For Fellow-Prisoners

O God, early in the morning I cry to you.

Help me to pray

And to concentrate my thoughts on you;

I can’t do this alone.

In me there’s darkness,

But with you there’s light;

I’m lonely, but you don’t leave me;

I’m feeble in heart, but with you there’s help;

I’m restless, but with you there’s peace.

In me there’s bitterness, but with you there’s patience;

I don’t understand your ways,

But you know the way for me.

~ Dietrich Bonhoeffer

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Bisogna trovare, in mezzo ai piccoli pensieri che ci danno fastidio, la strada dei grandi pensieri che ci danno forza.”

— Dietrich Bonhoeffer

#bisogna#bisogno#trovare#piccoli pensieri#pensieri#che fastidio#fastidio#grandi pensieri#dare forza#frasi tumblr#frasi#frasi e citazioni#dietrich bonhoeffer

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

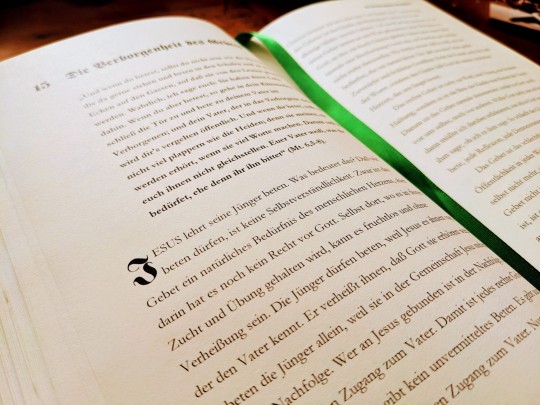

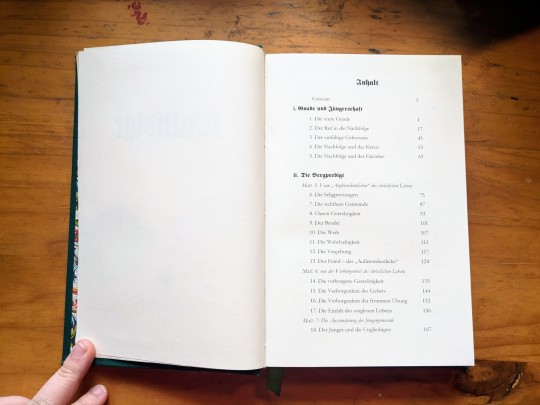

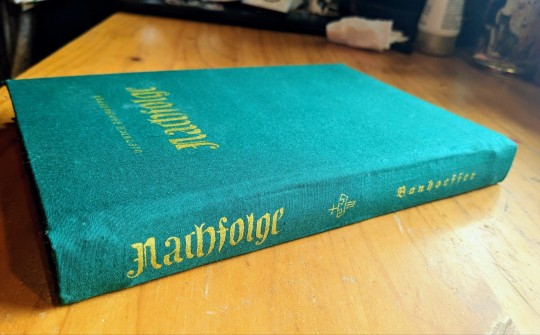

Another Bonhoeffer book, for my father for father days, which I finished were last summer but neglected to post until now, whoops. The typesetting was based off the version found in the Internet Archives, and the cover design based off of one of the early editions, except I made the green a lot darker and the lettering gold so in all... Not that similar to that edition ahaha. This shade of green seems to dislike being photographed, but I've done my best to represent it. It's certainly been interesting to use cloth instead of paper, which I'm more used to using, and in the process of typesetting I learned how to use drop caps which I am now very keen on, as well as page footnotes. The end papers are also a homage to the other Bonhoeffer book I've bound for my father, which has the same end papers.

#rose serpent press#rose serpent bindery#renegade bindery#bookbinding#dietrich bonhoeffer#bonhoeffer#photos are kinda shit hnnnghhh.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

A német történelem legsötétebb fejezetében, amikor a felbujtott csőcselék köveket dobált az ártatlan üzlettulajdonosok ablakaiba, nőket és gyerekeket nyíltan aláztak meg kegyetlenül; Dietrich Bonhoeffer, egy fiatal lelkész nyilvánosan felszólalt az atrocitások ellen.

Miután éveken át próbálta megváltoztatni az emberek véleményét, egy este mikor Bonhoeffer hazatért, saját apjának kellett elmondania neki, hogy két férfi várja a szobájában, hogy elvigyék.

A börtönben Bonhoeffer azon kezdett el elmélkedni, hogyan vált a költők és gondolkodók országa gyávák, szélhámosok és bűnözők kollektívájává. Végül arra a következtetésre jutott, hogy a probléma gyökere nem a rosszindulat, hanem az ostobaság.

Bonhoeffer a börtönből írt híres leveleiben azzal érvelt, hogy az ostobaság veszélyesebb ellensége a jónak, mint a rosszindulat, mert míg „tiltakozni lehet a rossz ellen; erőszakkal leleplezhető és megelőzhető, a hülyeséggel szemben védtelenek vagyunk. Sem a tiltakozás, sem az erőszak alkalmazása nem ér semmit. Az érvek süket fülekre találnak.”

Azokat a tényeket, amelyek ellentmondanak egy hülye ember előítéletének, egyszerűen nem hiszi el, és ha megcáfolhatatlanok, akkor lényegtelenként, mellékesként félre teszi őket. A hülye ember önelégült, és könnyen ingerülten támadásba lendülve veszélyessé válik.

Emiatt nagyobb elővigyázatosság szükséges, ha egy ostoba emberrel bánunk, mint amikor egy rosszindulatúval. Ha tudni akarjuk, hogyan lehet felülkerekedni a butaságon, törekednünk kell annak természetének megértésére.

Annyi bizonyos, hogy a hülyeség lényegében nem intellektuális, hanem erkölcsi hiba. Vannak emberek, akik feltűnően mozgékonyak intellektuálisan, de ostobák, és vannak olyanok, akik intellektuálisan unalmasak, de nem hülyék.

Nem annyira az a benyomás alakul ki az emberben, hogy a hülyeség veleszületett hiba, hanem az, hogy bizonyos körülmények között az embereket hülyévé teszik, vagy inkább megengedik, hogy ez megtörténjen.

A magányosan élőknél ez a hiba ritkábban jelentkezik, mint a csoportokban előknél. Ezért úgy tűnik, hogy a hülyeség kevésbé pszichológiai, mint szociológiai probléma.

Nyilvánvalóvá válik, hogy a hatalom minden erős felfutása, legyen az politikai vagy vallási jellegű, az emberiség nagy részét butasággal fertőzi meg. Mintha ez egy szociológiai-pszichológiai törvény lenne, ahol az egyik hatalmához a másik hülyesége kell.

A folyamat itt nem az, hogy bizonyos emberi képességek, mint például az értelem, hirtelen meghibásodnak. Ehelyett úgy tűnik, hogy a növekvő hatalom elsöprő hatása alatt az embereket megfosztják belső függetlenségüktől, és többé-kevésbé tudatosan feladják autonóm pozíciójukat.

Az a tény, hogy a hülye ember gyakran makacs, nem vakíthat el attól, hogy nem független. A vele való beszélgetés során az ember gyakorlatilag azt érzi, hogy egyáltalán nem is mint emberrel van dolga, hanem szlogenekkel, hívószavakkal és hasonlókkal, amelyek birtokba vették.

Megbabonázták, megvakították, visszaélnek vele, és lényében bántalmazzák. Miután így esztelen eszközzé vált, az ostoba ember is képes lesz minden rosszra – nem látja, hogy az gonosz.

Az utasítás nem, csak a felszabadítás képes legyőzni a hülyeséget. Itt be kell látnunk, hogy a legtöbb esetben a valódi belső felszabadulás csak akkor válik lehetségessé, ha az a külső felszabadulás megelőzte. Amíg ez nem történik meg fel kell hagynunk minden próbálkozással, hogy meggyőzzük az ostoba embert.

Bonhoeffer az Adolf Hitler elleni összeesküvésben való részvétele miatt 1945. április 9-én hajnalban a flossenbürgi koncentrációs táborban hunyt el, mindössze két héttel azelőtt, hogy az Egyesült Államokból érkező katonák felszabadították a tábort.

Bonhoeffer szavaival: „A cselekvés nem a gondolatból fakad, hanem a felelősségre való készségből. Az erkölcsös társadalom végső próbája az, hogy milyen világot hagy gyermekeire.

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In the Incarnation the whole human race recovers the dignity of the image of God. Thereafter, any attack, even on the least of men, is an attack on Christ, who took on the form of man, and in his own Person restored the image of God in all. Through our relationship with the Incarnation, we recover our true humanity, and at the same time are delivered from that perverse individualism which is the consequence of sin, and recover our solidarity with all mankind."

~Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Bisogna trovare, in mezzo ai piccoli pensieri che ci danno fastidio, la strada dei grandi pensieri che ci danno la forza.”

[D. Bonhoeffer]

#frasi#pensieri#frasi pensieri#frasi tumblr#frase del giorno#frasi italiane#quotes#citazioni#frasi libri#citazioni libri#dietrich bonhoeffer

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Von guten Mächten treu und still umgeben

Von guten Mächten treu und still umgeben,

behütet und getröstet wunderbar,

so will ich diese Tage mit euch leben

und mit euch gehen in ein neues Jahr.

Noch will das alte unsre Herzen quälen,

noch drückt uns böser Tage schwere Last.

Ach Herr, gib unsern aufgeschreckten Seelen

das Heil, für das du uns geschaffen hast.

Und reichst du uns den schweren Kelch, den bittern

des Leids, gefüllt bis an den höchsten Rand,

so nehmen wir ihn dankbar ohne Zittern

aus deiner guten und geliebten Hand.

Doch willst du uns noch einmal Freude schenken

an dieser Welt und ihrer Sonne Glanz,

dann wolln wir des Vergangenen gedenken,

und dann gehört dir unser Leben ganz.

Laß warm und hell die Kerzen heute flammen,

die du in unsre Dunkelheit gebracht,

führ, wenn es sein kann, wieder uns zusammen.

Wir wissen es, dein Licht scheint in der Nacht.

Wenn sich die Stille nun tief um uns breitet,

so laß uns hören jenen vollen Klang

der Welt, die unsichtbar sich um uns weitet,

all deiner Kinder hohen Lobgesang.

Von guten Mächten wunderbar geborgen,

erwarten wir getrost, was kommen mag.

Gott ist bei uns am Abend und am Morgen

und ganz gewiß an jedem neuen Tag.

--Dietrich Bonhoeffer

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Left side: In clockwise order from the top left, Dorothy Day (Catholic Worker Movement), Daniel Berrigan (Anti-Vietnam War/Ploughshares Movement/Peace activist, imprisoned for draft resistance activities), Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Anti-German government from 1933-1945, when he was murdered by that same German government), and Oscar Romero (now a saint, human rights and social reform advocate in El Salvador (Liberation Theology adjacent), murdered with the approval of the CIA in 1981). And then MLK.

Right side: Christofascists you are probably very familiar with. The least persecuted people ever crying the loudest that they are being repressed. Fuck 'em all.

It's weird to think my dad knew Daniel Berrigan (fairly well, they were in the Jesuits at the same time and Berrigan influenced him to become a CO during Vietnam, though his draft number was never called (he ripped up his draft card when he received it, kept half of it in his wallet for a long time, I think it's now somewhere in his office)) and Dorothy Day (through folks who had been with CW for a long time, he said she was great but the way some Catholic Worker folks revered her was a little culty, and this was in 1960s-1970s San Francisco, where most things were a little culty to begin with) along with several people who knew Romero and Merton (not featured here but Thomas Merton is tops). Small world, I guess.

#catholic left#dietrich bonhoeffer#daniel berrigan#dorothy day#catholic worker movement#oscar romero#mlk jr#christofascists

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

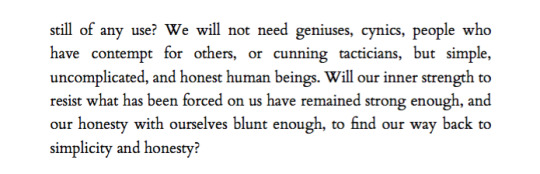

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906 – 1945), Are We Still of Any Use?, from: Letters and Papers from Prison; An Account at the Turn of the Year 1942-1943

Text under the cut.

[Are We Still of Any Use?

We have been silent witnesses of evil deeds. We have become cunning and learned the arts of obfuscation and equivocal speech. Experience has rendered us suspicious of human beings, and often we have failed to speak to them a true and open word. Unbearable conflicts have worn us down or even made us cynical. Are we still of any use? We will not need geniuses, cynics, people who have contempt for others, or cunning tacticians, but simple, uncomplicated, and honest human beings. Will our inner strength to resist what has been forced on us have remained strong enough, and our honesty with ourselves blunt enough, to find our way back to simplicity and honesty?]

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

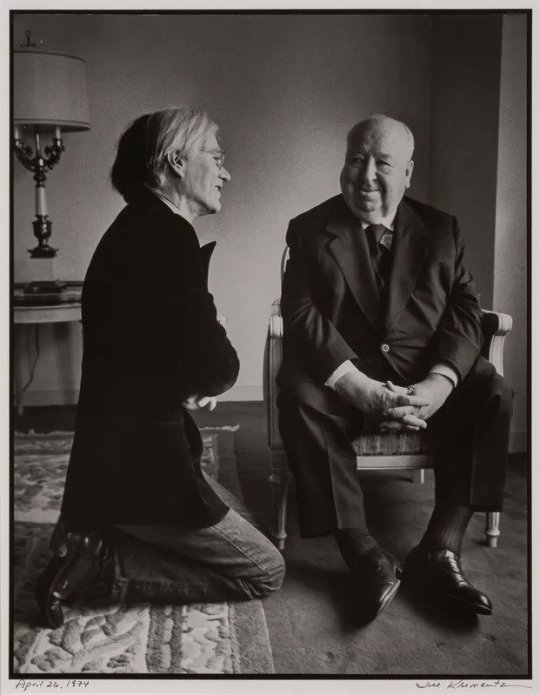

The 'polymath' had already died out by the close of the eighteenth century, and in the following century intensive education replaced extensive, so that by the end of it the specialist had evolved. The consequence is that today everyone is a mere technician, even the artist.

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison

Alfred Hitchcock gets his photo taken by Andy Warhol.

#bonhoeffer#dietrich bonhoeffer#quote#polymath#arts#artist#technician#culture#aesthetics#specialism#andy warhol#alfred hitchcock

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

The time in which one could say everything by words—be they theological or words of piety—is over; likewise the time of inwardness and conscience, that is, the time of religion altogether.

Die Zeit, in der man alles den Menschen durch Worte—seien es theologische oder fromme Worte—sagen könnte, ist vorüber; ebenso die Zeit der Innerlichkeit und des Gewissens und d. h. eben die Zeit der Religion überhaupt.

— Dietrich Bonhoeffer, letter to Eberhard Bethge, Apr 30, 1944, in Bonhoeffer Werke vol viii, p 402

[Robert Scott Horton]

14 notes

·

View notes