#Dimetrodon grandis

Text

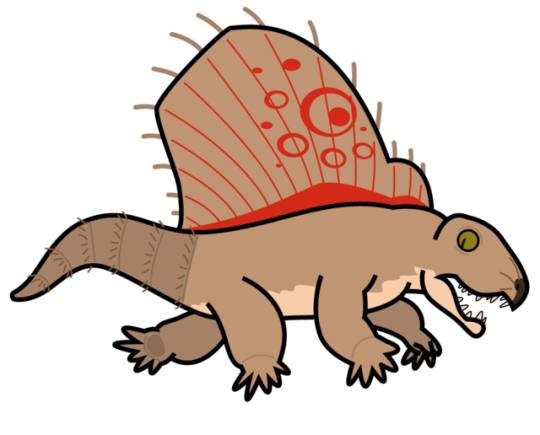

A little watercolour drawing of Dimetrodon (main reference image I used was D. grandis) I might've goofed up the shading a little but I'm still pretty happy with it. Again the photo was taken in piss poor lighting but that's tradition for me at this point. I also used some coloured pencils to add details

#art#my art#traditional art#watercolour#paleoart#paleontology#synapsids#dimetrodon#dimetrodon grandis#queue

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Fossil Friday!

Who: Dimetrodon grandis

name meaning: "two-measures-of-tooth" "large"

pronunciation: Dime-ee-troh-don gran-dis

What: Dimetrodon, a quadrupedal synapsid with a large dorsal sail

When: Permian period (279.5 to 272.5 Ma (Million Years Ago))

Where: USA (Texas and Oklahoma)

Why are they cool?: Dimetrodon are actually closer related to us than to dinosaurs! Though this particular group was not directly ancestral to mammals, they shared the temporal fenestrae (singular socket behind the orbit) with other synapsids that would become the ancestors to Mammalia.

Here is a link to a cute video showing some of the representations of Dimetrodon over the years, a very popular cameo in Dinosaur media.

Image Credits: (Left: M. Cross. Right: Marcos Villarroel, arstation.com)

#palaeontology#paleontology#fossil friday#fossils#paleo#palaeoart#paleoart#Dimetrodon#Dimetrodon grandis

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some pictures of my Dimetrodon plushie. Her name is Dinner :3

I love her and her stupid (/aff) synapsid face very much... her eyes remind me of Rivulet from Rain World tbh.

#Not really related to what I usually post but#I just wanted to share my goober#plushies#Dimetrodon#Dimetrodon grandis

0 notes

Photo

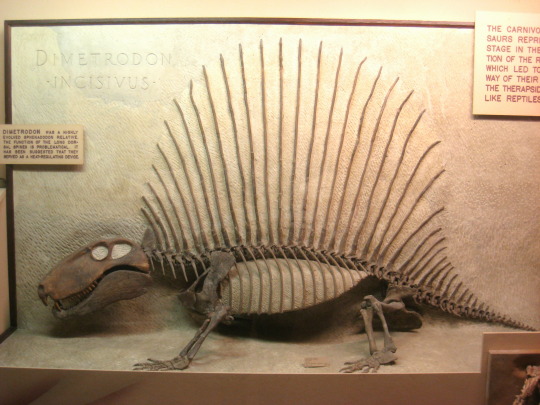

April’s Fossil of the Month - Dimetrodon (Dimetrodon spp.)

Family: Sphenacodon Family (Sphenacodontidae)

Time Period: 295–270 Million Years Ago (Late Permian)

Although the 14-or-so species of stockily-built quadrupedal vertebrates in the genus Dimetrodon are commonly included alongside dinosaurs in popular culture, every member of this genus was already long extinct by the time the first dinosaurs developed (with the most recent known Dimetrodon species, Dimetrodon grandis, disappearing from the fossil record around 270 million years ago, while the earliest known dinosaurs appear some 25 million years later.) The morphology of the skulls of Dimetrodon species (particularly the shape of their temporal fenestrae, a pair of openings behind the eye sockets which housed muscles that operated the jaws in life) suggests that they were actually synapsids - a group of animals containing the mammals and their closest relatives, and while this makes them a “sister-group” to mammals they were still part of a separate group of non-mammalian synapsids with no direct living descendants. While the size of Dimetrodon species varied enormously (ranging from the 60cm/2ft long Dimetrodon teutonis to the 4.6 meter/15 foot long Dimetrodon angelensis, which was among the largest terrestrial animals of its time,) all were alike in possessing a distinctive dorsal “sail” made up of several elongated extensions of their vertebrae, likely with skin running between them. The purpose of this sail has been the subject of extensive debate; it was historically thought to have been used in thermoregulation (with the skin between the vertebral extensions plausibly containing blood vessels, allowing the sail to absorb heat and transport it around the body when exposed to direct sunlight, or to lose heat by flushing the sail with blood to allow it to disperse into the air when in the shade,) but more recently it has been suggested that it may also have served a role in courtship. The name “Dimetrodon” translates roughly to “two measured teeth”, in reference to the fact that, unlike reptiles, members of this genus had two different types of teeth suited to different functions - large canine teeth for gripping and tearing meat, and smaller “shearing” teeth that were likely used to more delicately remove meat from bones. Based on their dentition, it is likely that all Dimetrodon species were carnivores that fed on smaller vertebrates such as amphibians, reptiles and possibly smaller synapsids.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Sources:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dimetrodon_incisivus_Exhibit_Museum_of_Natural_History.JPG and https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dimetrodon_grandis_3D_Model_Reconstruction.png

#dimetrodon#synapsid#synapsids#zoology#biology#paleontology#paleobiology#animal#animals#wildlife#prehistoric wildlife#evolutionary biology#permian wildlife#non-mammalian synapsids#prehistoric animals

156 notes

·

View notes

Note

Eclipse gang, ft. Dimetrodon grandis the synapsid :3

day 53 guest[s]: hoping they have fun!!!

#rain world#rw slugpup#rw slugcat#<- for the slugcat plush ofc. different from the slugpups#daily slugplush#guest plushies

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

atheists be like go great-great-great x10mil grandpa (Dimetrodon grandis doodles)

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

DAY THREE COMPLETE... at 1:45am, ugh.

This is a Dimetrodon grandis whose sail is a turkey tail mushroom. I used this picture of a 3D model as a reference. As my boyfriend reminded me, Dimetrodon is NOT a dinosaur; they are actually synapsids, i.e. "mammal-like reptiles," and went extinct prior to the dinosaurs' rise to prominence.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Not a dinosaur, but just as extinct as any of the others. Doing the research for this one was a little difficult, as there's a bit of confusion about what their skin covering was. To play the middle I gave them some wrinkly skin, but also put a layer of paper texture over it to simulate scales.

Hudson is based on my Dimetrodon borealis art from a while ago. Because of how niche it is, it's probably never going to see play in a game. The rest are generic Dimetrodon, either grandis or limbatus. Renaissance is based on the art of traheripteryx from ages ago. Not sure they still want to be associated with it anymore. It's called Renaissance due to that period of time seeing a lot of new art and speculation about them. Though most of them turned out to be incorrect, it's still an important era in dimetrodon art that I wanted to represent. Monstrous is based off of its appearance in Walking with Monsters, which I think is the only time the genera has been animated on the screen, that I can remember at least.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dimetrodon grandis

I was wrong about yesterday being the last day of Synapsid Week, so here's a classic :)

#dimetrodon#dimetrodon grandis#paleoart#paleontology#synapsid week#synapsidweek#stem mammal#june 30th 2021#not a reptile#???

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arguably the most famous non-mammalian synapsid is Dimetrodon. There are over a dozen species of Dimetrodon, and for my first one I’ve chosen D. grandis. (mostly just due to the fact that there was a skeletal readily available.)

Famous for its tall spine, Dimetrodon is often confused for a dinosaur and seen as a contemporary, though it lived long before dinosaurs existed. As a synapsid, it is more closely related (though not a direct ancestor) to mammals than reptiles. Larger species would have probably been the apex predators of their environments, while smaller species would have filled different niches.

Dimetrodon grandis was the second largest species of Dimetrodon, and had serrated teeth specialized in slicing through flesh. It lived in early Permian Texas.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So... Basically, Easter food preparations got me thinking: "What if... stained Dimetrodon eggs?" So obviously, I had to paint this. Mama Dimetrodon accidentaly built her nest with something that stained her eggs green. It didn't harm them in any way, and the babies are healthy and hatching right on time, but it could be a bit of a surprise if she cared at all about stuff like the colour the eggs are. But she doesn't. This is a quick-ish painting, though it took way longer than I intended. I always underestimate just how much time painting takes. This isn't a very likely scenario, but I guess it's not an impossible one. Also, we have no evidence, as far as I know, for parental care (or lack thereof) in Dimetrodon but considering that it's present in reptiles, amphibians, fish, and insect, I'd say it entirely possible that they cared for their offspring to some extent. Babies are completely speculative, because while juvenile dimetrodons have been found, finding any descriptions online proved impossible. Not to mention any figures that'd show the skeletons. So I based the baby's sail loosely on D. natalis for no other reason than the fact that Bakker seems to think natalis is a juvenile of limbatus (others disagree). I also shortened the snout somewhat, and made the eye bigger. I also decided to have the neural spines quite soft, and not completely ossified. Absolutely for no other reason than: "but how come sail... in an egg?"

#Dimetrodon grandis#synapsids#synapsida#sphenacodontidae#pelycosaurs#Permian fauna#prehistoric animals#extinct animals#paleoart#palaeoart#sciart#palaeoblr#sail back#absolutely not a dinosaur#it's a stem-mammal#say hi to your 1000xgreat grand aunt

132 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Something in the air... by tuomaskoivurinne

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dimetrodon!

A wonderful mammal-like reptile boy! There’s actually (as far as I know) no evidence for the whiskers and the hair, but it’s an interesting concept, and I like it!

Available at my Redbubble!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s what we finished on stream!

A new border! All north American fauna/flora/fungi

Stream was fun, and it was nice directly talking to folk!

This border will be in use once I switch us to OBS, however there’s a couple more planned before then.

I plan to stream on sundays around 3-6PM PST but that may change!

namely gaming and art

fly agaric Amanita muscaria

Laysan albatross Phoebastria immutabilis

lilac fibrecap Inocybe geophylla

Canariomys bravoi Tenerife giant rat

clustered bonnet

Frost's amanita

Chicken of the woods

Pleurotus ostreatus Oyster Mushroom

Fomitopsis mounceae

Puffball

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus

Common raven corvus corax

Dimetrodon grandis

Cantharellus cascadensis

Pyropyxis rubra

Cortinarius subfoetidus

jelly toothed fungus Pseudohydnum gelatinosum

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The caption “Illustration of the pelycosaur dinosaurs Dimetrodon grandis (left) and Edaphosaurus progonias (right) battling during the Permian period in what is now North America.” is incorrect.

Doing a search for “Dimetrodon vs Edaphosaurs” just now lead to this stock illustration from this page.

Science Photo Library hosts stock photography and illustration for professional graphics use. A valuable resource, but every now and then the captions for its illustrations have errors. In this case, both Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus are are correctly identified as pelycosaurs (as that label is traditionally used), though distantly related despite both sporting dorsal sails (a trait each developed independently of the other). However pelycosaurs are not a subgroup of dinosaurs! They are, as traditionally viewed, primitive mammal-like reptlies. In cladistics though, “Pelycosauria” is a paraphyletic grouping, meaning that it includes some but not all of the taxa that are closely related to the basal members. All pelycosaurs, however, are members of the Synapsida, the clade of tetrapods (fully terrestrial vertebrates) that include mammals, and by extension, humans. They are more closely related to us than to dinosaurs.

So, to repeat, Dimetrodon and Edaphossaurus are not dinosaurs. They are classified in the synapsid lineage that we belong to, rather than the reptile lineage that dinosaurs, birds, and crocodiles belong to.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part XI: Dimetrodon teutonis, an apex predator

Holotype specimen of Dimetrodon teutonis, which consists of a partial vertebral column. The preserved portion of this vertebral column is highlighted in the reconstruction of Dimetrodon (lower right). Photograph by the author, 2007. Dimetrodon reconstruction modified from Romer and Price, 1940.

Specimens of two top predators have been discovered at the Bromacker quarry. Like Martensius, both are basal members of the group Synapsida, the later members of which gave rise to mammals. You might be familiar with one of them – Dimetrodon, a synapsid sometimes incorrectly portrayed with dinosaurs, which carried a tall sail on its back that was supported by bony spines. The other is a new genus and species that will be presented in my next post.

The fossil pictured above, the first-discovered specimen of Dimetrodon from the Bromacker quarry, may not look like much, but it was the first record of Dimetrodon outside of North America. The circumstances under which it was found were very different from the discovery of other fossils from the Bromacker quarry. Before Dave Berman and I arrived for the 1999 field season, Thomas Martens noticed that someone, possibly a fossil poacher, had been in the quarry overnight and knocked some rocks off the quarry lip. The rocks apparently broke upon hitting the ground, which exposed some bones. Thomas carefully picked them up and took them to his lab at the Museum der Natur, Gotha (MNG). When Dave and I met Thomas at the quarry on our first day of the field season, Thomas mentioned the find and told us that he thought the bones were ribs. We didn’t think much of it, other than horror at learning a fossil poacher might have visited the quarry overnight, one of our worst fears.

As planned, Dave and I spent the last day of the field season in the museum collections, and when Thomas let us in that morning, he reminded us to look at the potential ribs and told us where they were. Shortly after we began examining them, Dave and I simultaneously realized that the “ribs” were actually spines of Dimetrodon. We couldn’t believe our eyes, because of all the Early Permian fossils known from North America, Dimetrodon was Thomas’ favorite. Indeed, he’d used an image of it on signs at the Bromacker and included a model of Dimetrodon in a diorama, once on display in the MNG, that showed models of Bromacker animals in their environment. Thomas jumped for joy later that day when we gave him the news.

So how did Dave and I so quickly realize that the “ribs” were spines of Dimetrodon? Besides Dimetrodon, some other basal synapsids had sails, the function of which remains unknown, though scientists have speculated they could’ve been used for display or regulating body temperature. The spines (known as neural spines) supporting the sails vary in shape and length, with those of Dimetrodon and its herbivorous relative Edaphosaurus being tall and narrow, and those of another relative, the carnivorous Sphenacodon, being shorter and blade-like. Neural spines of Dimetrodon are easy to distinguish, because in addition to being long they bear fore and aft grooves, which create a dumbbell-shaped cross-sectional outline, and they lack the ‘crossbars’ that occur on the long neural spines of Edaphosaurus. When Dave and I saw the fore and aft grooves, the dumbbell-shaped cross-sectional outline of some broken spine ends, and an absence of crossbars, we knew that the “ribs” were indeed spines of Dimetrodon.

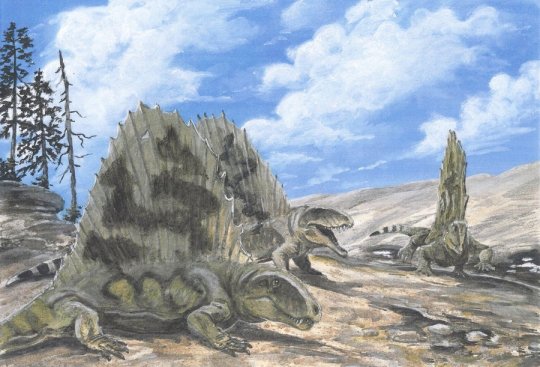

Flesh reconstructions of Sphenacodon sp. (left) Dimetrodon grandis (middle) and Edaphosaurus pogonias (right) to show the differences between their sails. Note that Dimetrodon and Sphenacodon are more closely related to one another than they are to Edaphosaurus, despite their different sail shapes. Reconstructions of Sphenacodon and Dimetrodon by Dmitry Bogdanov and that of Edaphosaurus by Nobu Tamura, all from Wikimedia Commons.

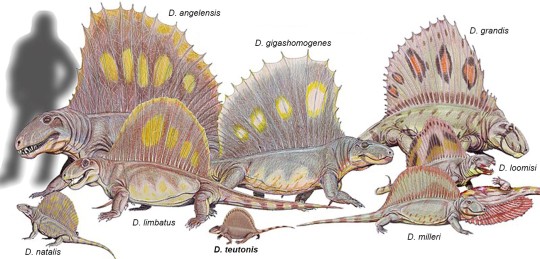

The Bromacker Dimetrodon is considerably smaller than other known species of the genus, and this is one character among other more detailed anatomical features that distinguishes it. For the new species name, Dave selected the Latin “teutonis,” which means an individual of a German tribe, in reference to the geographic origin of the holotype specimen.

Two additional specimens of Dimetrodon teutonis. Left, hindleg and shoulder girdle bone (fused scapulocoracoid) and right, several vertebrae bearing complete to nearly complete neural spines of an individual that was larger and presumably more mature than the holotype. Photographs by the author, 2007.

Dave was able to use a mathematical equation involving measurements of the vertebrae to estimate the holotype’s weight as a living animal at 31 pounds. In contrast, other known Dimetrodon species have estimated weights of about 81–550 pounds. We later discovered additional partial specimens of Dimetrodon at the Bromacker quarry, and Dave estimated the weight of the largest specimen with vertebrae at 53 pounds, still considerably less than that of what had previously been the smallest species, D. natalis from Texas. Dimetrodon is otherwise known from numerous species from the American mid-continent and southwest that generally got larger through time.

Reconstructions of various species of Dimetrodon drawn to scale. The diminutive D. teutonis is at bottom center and D. natalis, no longer the smallest species, is at bottom left. Illustration adapted from Dmitry Bogdanov via Wikimedia Commons.

All Dimetrodon species have teeth adapted for meat-eating in being teardrop-shaped with sharp edges for slashing flesh. By size and jaw position these sharp teeth are divided into precanines, canines, and postcanines of varying numbers. Unlike D. teutonis, some species even had fine serrations on their tooth edges. The only known upper jaw bone of Dimetrodon teutonis clearly has two canines, but one is missing and represented by a large gap in the tooth row that would have accommodated this tooth. The second canine is represented only by its broad base, but it too must have been large. Although it was a small animal, the teeth of D. teutonis indicate that it was a meat-eater and as such would have preyed on other vertebrates from the Bromacker, many of which were even smaller.

Diagrammatic drawing of the skull of Dimetrodon (left) and photograph of the maxilla or upper jaw bone (right) of D.teutonis. Abbreviations: c, canine; pc, postcanine; prc, precanine. Photographs by the author, 2007. Drawing of skull from Wikimedia Commons.

Stay tuned for my next post, which will be about the second-known apex carnivore from the Bromacker. In the meantime, here are links to scientific papers on Dimetrodon teutonis:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325670232_A_new_species_of_Dimetrodon_Synapsida_Sphenacodontidae_from_the_Lower_Permian_of_Germany_records_first_occurrence_of_genus_outside_of_North_America

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288544821_New_materials_of_Dimetrodon_teutonis_Synapsida_Sphenacodontidae_from_the_Lower_Permian_of_Germany

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Dimetrodon#Fossils#Bromacker#Bromacker Quarry#Apex predator#Paleontology

37 notes

·

View notes