#Galla Placidia

Text

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, built in 5th century. It is thought to contain the tomb of Galla Placidia (died 450), the daughter of the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. Someone accidentally burned the contents of the tomb in 1577. Emperor Valentinian III or Emperor Honorius and Galla’s husband Emperor Constantius III may still be buried in the tomb.

Ravenna, Italy

#ancient rome#ravenna#italy#italia#mausoleum#tomb#ancient art#mosaics#original photography#photography#taphophile#taphophilia#lensblr#photographers on tumblr#ancient history#galla placidia#archaeology#wanderingjana

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Such an interesting article! It's also really long, but well worth the read.

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ravenna, Italy - Mausoleum Galla Placidia

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

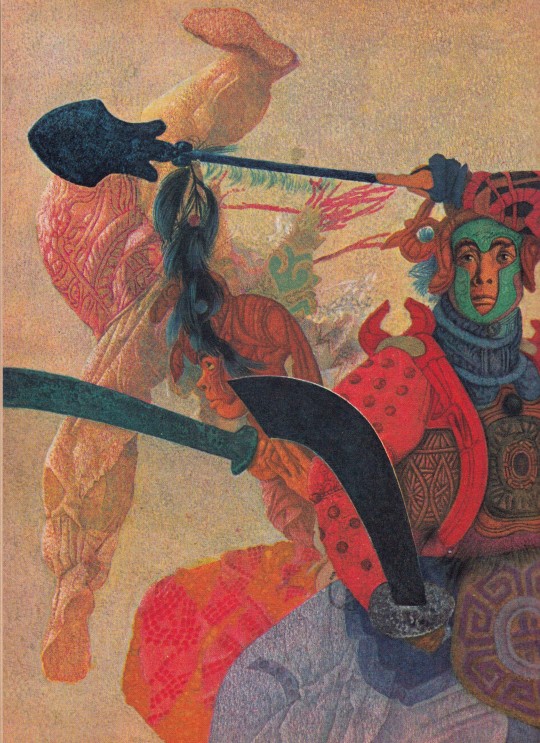

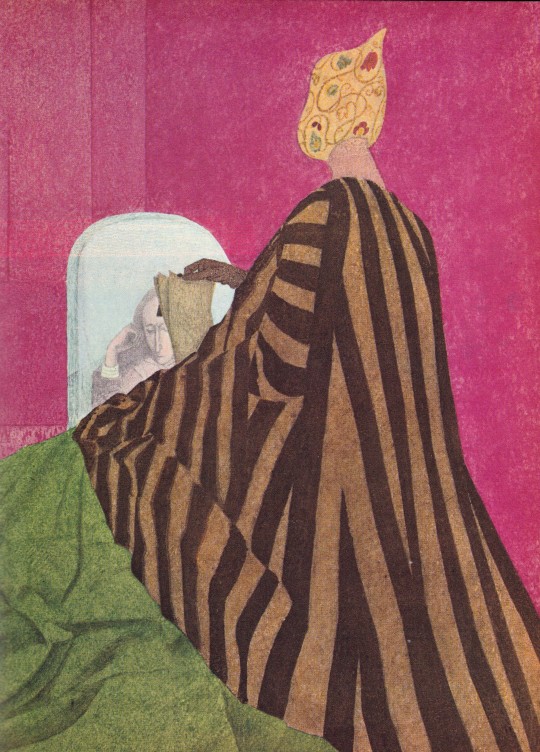

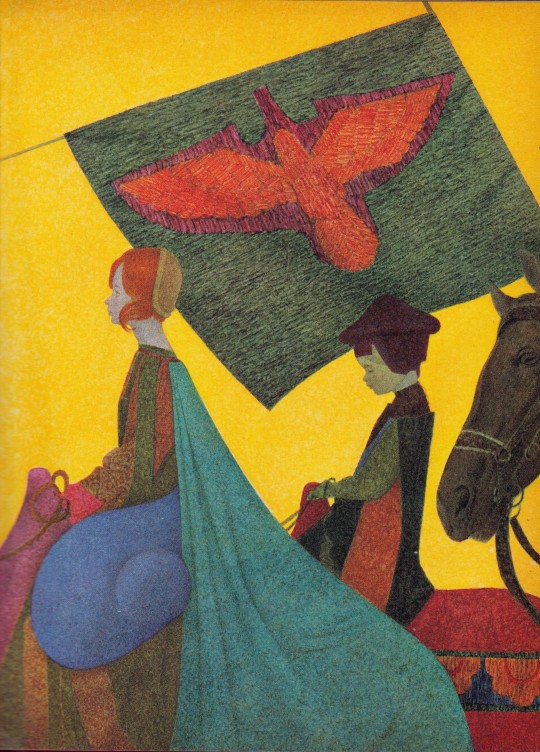

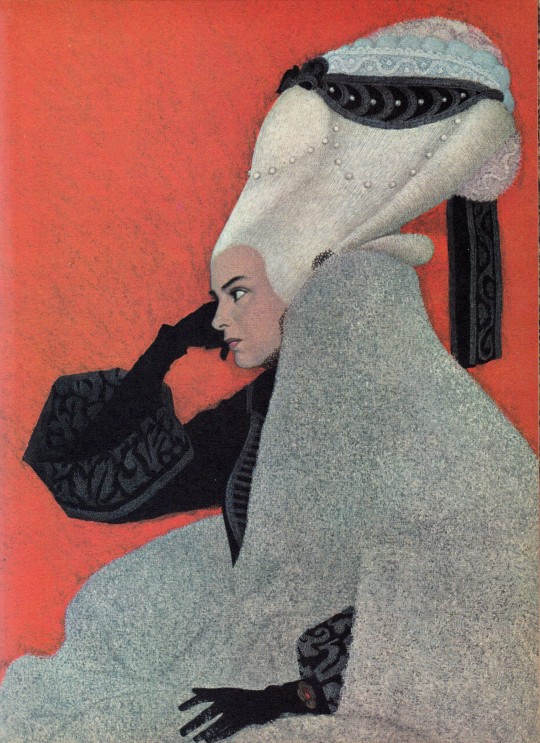

Grandi Regine

Giuliana Pistoso

Illustrazioni di Ugo Fontana

Mondadori, Milano 1968, 155 pagine, 20x28cm

euro 15,00

email if you want to buy : [email protected]

Galla Placidia - Adelaide di Borgogna - Margherita d'Austria - Isabella di Castiglia - Caterina de Medici - Elisabetta d'Inghilterra - Maria Teresa d'Austria - Caterina di Russia

Le protagoniste delle vicende narrate in questo volume - otto eccezionali figure di sovrane - abbracciano e dominano, anche per la loro longevità, un arco vastissimo di tempo: circa quattrocento anni di storia. Intelligenza, sensibilità, coraggio, intuito politico sono le doti che queste regine leggendarie, quasi un simbolo dei tempi in cui vissero, rivelarono nel corso del loro governo, meritando l'attributo di "grandi". In queste pagine, impreziosite da documenti e tavole di raffinata concezione, le grandiose figure delle otto regine riacquistano per il lettore di oggi contorni umani, pur sfumati fra toni di luce e d'ombra, fra verità e leggenda.

Grandi regine è un volume di biografie di sovrane dall'antichità fino all'età moderna (da Galla Placidia e Caterina di Russia): per illustrare il testo di Giuliana Pistoso, Ugo Fontana si è ispirato alla storia dell'arte, soprattutto del Rinascimento, rielaborandone in modo originale l'iconografia.

24/07/23

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter:@fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilano

tumblr: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilanoillustration books

#grandi regine#Giuliana Pistoso#Ugo Fontana#Galla Placidia#Adelaide di Borgogna#Margherita d'Austria#Isabella di Castiglia#Caterina de Medici#Elisabetta d'Inghilterra#Maria Teresa d'Austria#Caterina di Russia#illustration books#fashionbooksmilano

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Galla Placidia girl boss edit

#meme#memes#shitpost#history memes#history#Roman history#Roman empress#Galla placidia#academic meme#college#college meme

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Galla Placidia was one of the most powerful women of Late Antiquity:

Under her some of the last recognized Emperors to hold full sway over it still exercised power and as a result of the convoluted courses of her life she was no small part of securing the Empire that lasted long enough to win its last victory over the very same figure her daughter invited in, Attila the Hun, at the Catalaunian fields in 450. This also raises a key point that will be a recurring motif through the last span of women's history month. Autocracy allowed a kind of political power otherwise barred to women, wealthy or not.

That power could be used well, or it could be used poorly. In Galla Placidia's case, unlike that of Honoria, it was used well.

1 note

·

View note

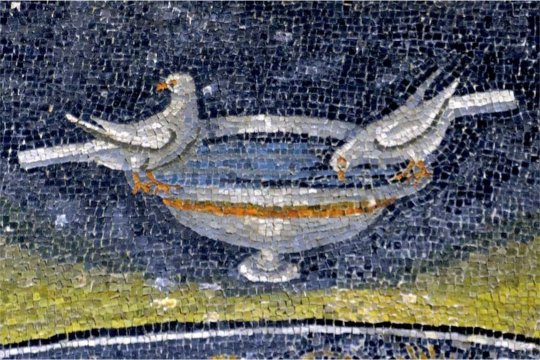

Photo

Maestri mosaicisti - Colombe abbeveranti - V sec d. C.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maestri mosaicisti - Galla Placidia - 425

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 6th century Byzantine mosaic of Christ as the Good Shepherd is in the Mausoleo di Galla Placidia, Ravenna, Italy. With their pure Hellenistic style, the Galla Placida mosaics are considered among the oldest in Ravenna.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna Monumental burial of the Emperor Honorius's sister, Galla Placidia. Built between 425 and 430.

140 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Galla Placidia

Galla Placidia (388-450 CE), the future empress, was the half-sister of the Westen Roman emperor Flavius Honorius (r. 395-423 CE), and the daughter of Theodosius the Great (r. 379-395 CE). She was taken hostage by Alaric during the sack of Rome 410 CE. After returning to Rome, she became regent for her young son, Honorius' heir, Valentinian III.

Continue reading...

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review 5 - The Bright Ages by Matthew Gabrielle and David M. Perry

Okay, the Harper Collins strike is over, so I can finally post this! As you might notice, the wait has meant I have ended up writing far too much of it. Turns out people really are telling the truth when they say writing negative reviews is funner and easier.

Anyway, I did not like this book! It’s an ungainly thing, torn halfway between wanting to be pop history and wanting to be an intervention in the discourse, and entirely too short to do either well. Insofar as is it history, it’s far less revolutionary than it seems to think it is, and the subjects it actually focuses on either already fit entirely into the pop understanding the book is positioning itself against, or else entirely about symbolism and architecture and generally abstracted from (being partial and small-minded) the stuff I’m actually interested in.

All that said the first and fundamental is pretty simple – it’s just altogether too short to do what it wants to. The book tries to be a history of the European Middle Ages – a thousand years of history for an entire continent (more than, given the repeated digressions about the Middle East and also the Mongols one time) – in 200 pages. Which is just, like, I mean I don’t want to say impossible, but I can’t really see any way you’d do it. Which means what we actually get is a series of snapshots, scattered across space and time – just specific, particular dynamics or situations that rarely have much to do with each other. I’m pretty sure the only specific place we ever return to after focusing on it is Ravenna, and that’s for a big, dramatic bookend starting the age with Galla Placidia and ending with Dante. Also the return is really more about Italian city states as a whole. Which is to say only Florence gets any detail at all.

A necessary causality of the snapshot approach is that there’s wide swathes of the period that just, aren’t mentioned in the slightest. Which again, fair, but also it’s a bit much for one of the lacuna to be the entire Holy Roman Empire, right? (Okay, not the entire, there’s repeated off hand mentions of Emperors, and also talk of how the Italian city-states fought the Empire. Just never any description whatsoever of what it, like, was. Except for the specific disavowal of saying it started with Charlemagne, which was never followed up on.) Which is still better than what Poland or Hungary or Lithuania or Kievan Rus got – if any of them were even mentioned, it was only off hand. Which does end up giving the impression that Medieval Europe included Jerusalem but not Krakow – to be fair, something a lot of actual Medieval people might have totally agree with. But given the amount of time spent on the Crusades to the Levant and the Albigensian Crusade, not even mentioning the bloody Christianize of the Baltic in passing feels negligent to the point of being actively misleading.

Also it’s weird, given the books whole focus on connections and commerce between Europe and the rider world – the steppe is right there! You don’t need to wait for the Mongols!

Speaking of – they give a bunch of apologia for the Mongol Empire that’s – well, basically the same stuff all empires get, brought safety to the roads and allowed free movement and trade, brought people together, spread culture and technology, enlightened and cosmopolitan, etc. Which I mostly just find funny because of how obvious it is the authors would, uh, probably not endorse the same sentiment for any more recent imperial projects.

But okay – it’s not that you can’t tell a useful history in what might seem to be way too little space – John Darwin tries to tell a literal history of the world from the 16th century in ~500 pages and I’d still say After Tamerlane is absolutely worthwhile reading. You just need, you know, discipline. Focus. A firm idea of your thesis and an obsession of what’s relevant to it (or just be entertaining and full of fun memorable trivia). So, what are Perry and Gabrielle actually trying to do here?

Honestly, it’s a little bit unclear? The thesis they present is that the Dark Ages didn’t exist – they insist on referring the whole Medieval period as ‘the Bright Ages’ through the entire book, it’s incredibly annoying – and that the Medieval period get a horribly unjustified bad wrap as uniquely cruel and provincial and barbaric and full of disease, illiteracy, superstition, etc. They explicitly position themselves as being a reaction to the vision of the past you see in Game of Thrones or Vikings (I’d say ‘or the Witcher’ but again, for the purposes of this book Eastern Europe doesn’t exist). Instead, they fill the book with hand picked examples of medieval beauty, sophistication, and connection to the wider world with the quite explicit contention that everything good about the Renaissance (and later) was really just outgrowths of the Medieval, and it was only the bad stuff that was new.

(At the same time, they also do not like white nationalists, and go out of their way at length on numerous occasions to remind you that Nazis are bad. Those digressions do always leave me wondering who they’re for – no actual Deus Vult type is going to get more than five pages into it, and they rarely get much deeper that surface level refutation of things no one else is likely to actually believe.)

Anyway – look, the central, overriding problem of the book is that it’s not nearly as revolutionary as it seems to think it is. Very problematic, when it has such a high opinion of itself for being so. The assorted trivia the book uses as shocking examples of how cosmopolitan and tolerant the period was mostly just, well, fit perfectly fine into the popular imagining of the Medieval era? Like ‘royals and elites imported foreign luxury goods and status symbols at great expense; missionaries, adventurers and religious emissaries travelled across Eurasia to preach, trade and try to find someone to help them invade Muslims ; women often wielded significant political influence by virtue of royal birth of marriage, and were active political players’ – are these statements shocking to literally anyone? Basically all of that literally happens in Game of Thrones!

Part of that is that the book keeps almost committing to a really radical thesis – not to say pure unreconstructed romanticism, but close to it – and then always has an attack of professional ethics and cringes away from it, and just awkwardly brings up how, to be sue, there were serfs and slaves and atrocities, but nonetheless when you think about it the later Crusader States really were fascinating sites of cultural exchange, or whatever.

Psychoanalyzing the authors is bad form, of course, but like – reading this book the overriding sense you get is that they’re proud progressives, and have dedicated their lives to studying the Medieval era. But in the contemporary discourse people on their side use ‘Medieval’ as an insult to mean patriarchal, or brutal, or cruel, and the people who like the Medieval era are all in the Sack of Jerusalem Fandom. The sheer angst and righteous indignation they have about this state of affairs just about oozes through every page – honestly if I’m being maximally pithy and uncharitable, you rather get the sense that the real aim of the book is to make ‘being really into Medieval history’ a less reactionary-coded interest to bring up at professional-class dinner parties.

But honestly I could have forgiven almost all of this if the anecdotes and snapshots the book did focus on were informative and interesting. And this is almost entirely pure personal preference, I fully acknowledge but – the things that the book chose to focus on just really weren’t, to me?

Which is to say that The Bright Ages is incredibly interested in architectural and monumental symbolism, especially of the religious variety – there are whole chapters overwhelmingly dedicated to exploring the layout of churches and how their architecture and lighting was meant to convey meaning, or detailing at great length a specific monumental cross in northern England. These are used as synecdoches for broader topics, of course but, like, an awful lot of word count really is dedicated to describing how Gala Placedia’s chapel in Ravenna must have wowed people. And even as far as using them as synecdoches – the way that monasteries, bishops and the royal household in Paris competed to have the most impressive church/chapel as a way to convey religious authority is genuinely interesting, but I’d honestly have rather heard a lot more of the actual politics and sociology or how sacred authority and legitimacy was gathered around the Capetians in the later middle ages and a lot less about how specifically impressive the royal chapel on the palace grounds was. There’s a massive amount of symbolic and artistic detail, a fair amount of time spent charting great thinkers and proving that there was too such a thing as a Medieval intellectual, and almost none at all on, like, political and social and (god forbid) economic history. Which are, unfortunately, the bits of it I’m actually interested in.

The book isn’t just architecture of course, but much of the rest is either very basic – yes, the vikings were traders as well as raiders and travelled shockingly long distances, yes there was intellectual interchange between Muslim, Jewish and Christian thinkers across the Mediterranean, yes the Church acted as a vital sponsor of learning and scholarship. I’m sure these are new information to like, someone? - or so caught up in historiographical arguments and qualifications that it loses sight of the actual subject – I swear the book spent more time saying that it’s wrong to call it a Carolingian Renaissance because that implies there were actual dark ages before and after than it does explaining why anyone actually would.

Beyond that – okay, so as mentioned this book is really consciously progressive. Which, beyond a certain antiquarian distaste for how desperately they’re trying to get across ‘see, our field of study is Relevant! And Important! Please please please give us tenure/prestige/funding’ I wholly support. (I mean, like, I do think Medieval Studies deserves tenure/prestige/funding. Just slightly unbecoming to so transparently be grasping for it, and also more than a bit self-defeating) - but, like, the book’s politics are weird? Or weirdly surface level and slightly confused, given how much of the book is focused around them.

Like – the book spends a massive amount of time and attention combating the myth that women in the middle ages were all cloistered and politically mute and totally powerless. But the sum total of what it actually says is ‘did you know: elite women in the aristocracy and church exercised political influence? And a lot of the Christianization of western Europe happened through highborn christian women marrying pagan kings and raising their children Christian?” And while I suppose ‘elite women have influence even in patriarchal societies’ is a useful fact for someone to learn, I’m not sure examples that more or less cash out to ‘queens could have power by manipulating their husbands and sons’ is a particularly novel or progressive take, you know? More broadly – it’s a weakness of the book’s framework of jumping across countries and centuries between anecdotes that we never get any sense of gender roles and how power and influence were gendered systemically, so much as single (or if you’re very lucky, two or three) particular women with a vague gesture that they’re kind of typical. Not to complain about a lack of theory, but there’s really basically zero theory.

The book’s choices of examples for women to focus on are also – okay, not to be all ‘why didn’t you talk about my faves’, but insofar as you’re talking how women were able to exercise power, it’s really very odd that you never talk about any women who, like, ruled in their own right? C’mon, you mention the Anarchy offhand to introduce Eleanor of Aquitaine but don’t even say what it was about, let alone talk about the Empress Matilda? (I’d say the same thing about Matilda of Tuscany and the investiture Controversy, but it’s not like the book actually talks about the Investiture Controversy beyond the absolute basics, so). The final result is a book that talks a lot about how elite women had influence, and then the influence they actually bring up is almost always of the most stereotypically feminine-gender variety imaginable.

All that really pales to how confused the book seems when it talks about Christianity. Which it has to, of course, fairly constantly – it’s a book about Medieval Europe. But it’s kind of horribly torn between two imperatives here – on the one hand, it desperately wants to fight back against the whole black legend of the tyrannical, book-burning, Galileo-murdering, science-suppressing hopelessly venal and corrupt, all-powering Magesterium. But on the other, they really don’t want to come off as supporting, well, the heretic murdering and antisemitism or being the sort of guy online who posts memes of the Knights Templar. So you see this somewhat exhausting two-step where they go on at length about all the beautiful architecture and scholarship preservation the church did interrupted every so often by this concession about how of course it wasn’t all good and obviously pogroms and burning heretics wasn’t great, but- (The chapter on the vikings is much the same, except with a much clearer ‘it’s important not to romanticize these people because the people who do that are white nationalists, but also see how tolerant and far-ranging and cool they are?’)

Discussing the Church is also a place where the book’s whole allergy to social structure and institutions really serves it poorly. I at a certain point stopped keeping count of the number of times where the book called out that the centralized, papal-centric Church was a creation of the high middle ages, and not at all how things worked for most of the period. But then they just never actually explain how they worked instead, or really even how things changed to so enshrine the Pope’s power. They talk about how convents could be wealthy and powerful landholders and their abbesses’ wield significant power, but never even gesture at explaining how they interfaced with the institutional church. It’s really very frustrating.

Of course Christianity still gets far better treatment than Judaism or Islam – there’s a chapter which goes into some detail on the life of Maimonides in the process of extolling Medieval scholarship and talking about how classical learning was never really lost and the Renaissance is fake news. But despite the gestures to the presence of Jewish communities throughout Europe there’s essentially zero, like, description of how they actually functioned, or were organized, or (aside from the occasionally mentioned pogroms) how they interacted with their christian neighbours. The treatment of Islam is much the same – there are some mentions of the Islamic wold and its intellectual traditions, but essentially just to rehash the same points about the Islamic Golden age and Ibn Sina and all the other bits of trivia everyone probably picked up keeping up with the culture war during the Bush Administration. But again, only the most passing mentions of, like, politics or organization or even theology. It felt gratingly cursory, given the emphasis placed on the fact that eg Al Andulas was clearly part of Medieval Europe

Underneath all this is just the fact that The Bright Ages is almost an entirely a history of the elite. Peasants, serfs and slaves only exist in the for the sake of concessions about how of course things weren’t all good. The book has almost no interest in the lives of the lower classes, and barely seems to realize this. It starts to really, really grate, especially when you’re making all these implicit judgments about how the Medieval era was compared to what came after – in which case, the lives of, like, 90% of the population are rather important! Like unironically peasant life is fascinating! What did life actually look like of the overwhelmingly majority of people? If you want to give a sketch of the entire era, it’s kind of important.

I’m almost certainly being unfair here – basically everything about the book’s sensibilities grated on me, so I can’t say I was trying to be especially charitable. But really – the book’s perfectly fine light reading, but as intentional propaganda is hamfisted and it’s unclear who it’s for, and as an actual history it’s just...bad. It’s useful as a way to get a sense of the discourse, I guess, but otherwise I couldn’t really recommend it.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the end of the fourth century, as the power of Rome faded and Constantinople became the seat of empire, a new capital city was rising in the West. Here, in Ravenna on the coast of Italy, Arian Goths and Catholic Romans competed to produce an unrivaled concentration of buildings and astonishing mosaics. For three centuries, the city attracted scholars, lawyers, craftsmen, and religious luminaries, becoming a true cultural and political capital. Bringing this extraordinary history marvelously to life, Judith Herrin rewrites the history of East and West in the Mediterranean world before the rise of Islam and shows how, thanks to Byzantine influence, Ravenna played a crucial role in the development of medieval Christendom.

Drawing on deep, original research, Herrin tells the personal stories of Ravenna while setting them in a sweeping synthesis of Mediterranean and Christian history. She narrates the lives of the Empress Galla Placidia and the Gothic king Theoderic and describes the achievements of an amazing cosmographer and a doctor who revived Greek medical knowledge in Italy, demolishing the idea that the West just descended into the medieval “Dark Ages.”

Beautifully illustrated and drawing on the latest archaeological findings, this monumental book provides a bold new interpretation of Ravenna’s lasting influence on the culture of Europe and the West.

8 notes

·

View notes