#Geoffrey of Anjou

Text

Femboy Geoffrey le Bel I commissioned from hisaoni_art on Twitter! He turned out so beautifully hehehe

#my commissions#Geoffrey le Bel#Geoffrey of Anjou#angevin empire#POV you are Matilda of England. U are not impressed#Henry to his sons: alas this is the only remaining image we have of ur grandpa#12th century#Medieval#Illustration#hisaoni_art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the guys are very much enjoying the world cup

#the gang's all here#france england spain the netherlands denmark and germany#live in consort#Geoffrey of Anjou#guildford dudley#Philip of Spain#William III#george of denmark#albert of saxe-coburg and gotha#normandy#tudor#stuart#hanover

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have seen a post comparing Steven's adoption of Henry II in the anarchy with what the Velaryons did with the Strong boys wanting to justify that their claim is legitimate, but in my humble opinion it is not comparable at all. This situation could be extrapolated to Aegon II having adopted his nephew Aegon (that was the LEGITIMATE son of his political rival) having himself a living son, in addition everyone would know that he is not his son and well in this case it would not be applicable but the adopted heir retains his family name...This is not what happens with the Strong boys, It has nothing to do with the modern concept of adoption that they want to apply. I don't understand why it's so hard for them to accept that these guys had no real claim to the throne. They can continue enjoying their characters accepting that they are bastards in every sense of the word. Do you think they are comparable situations?

I haven't seen this argument myself but clearly those are two completely different situations. Stephen didn't adopt Henry II, he made him his heir as a compromise to end to the civil war. And yes, the clear parallel would Aegon II naming Aegon III his heir over Jaehaerys and Maelor, had they survived. Again, this was part of a peace treaty. Everyone knew who Henry II's parents were, and there was no question of his not being trueborn. Henry II was still Count of Anjou, the title he inherited through his father, and styled himself Henry FitzEmpress in honor of his mother.

To understand why this happened, we need to look at some context. Henry II was only 20 when he decided to re-take his mother's throne, and Stephen was past 60. At that point England had been at war off and on for the better part of 15 years and both the clergy and the lords were unenthusiastic about continuing and forced Henry and Stephen to the peace table after Henry made some early gains in his campaign. Stephen respected Henry, and Stephen's own sons were kind of uninspiring as future kings go. Eustace, the older son and main obstacle, died before Stephen did, and the younger son, William, agreed to renounce his claim. Stephen never really took the throne due to strong personal ambition in the first place, but because he was persuaded by people close to him that Matilda would be a poor choice for queen, both due to her being a woman and due to the influence of her husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, who was pretty well hated in England. Leaving the throne to his children did not seem to be a major consideration for him when all was said and done. Conceding heirship to Henry II meant that the fighting could come to an end, and the country would be in capable hands, but Stephen himself would not face the humiliation and possible consequences of being outright deposed. As it turned out, Stephen died not even a year later, so Henry II took the throne sooner than expected.

Rhaenyra's Strong children are bastards that she's trying to put into the line of succession while claiming they are trueborn. They were not "adopted" by the Velaryons. The medieval world did not have a concept of adoption like we do in the modern world (Rome did, but not medieval Europe). The reason why it is treason to call them bastards is because what Rhaenyra is doing is illegal, and Viserys, Corlys, and Laenor are shielding her from the consequences. I wrote a post here about the whole idea that Rhaenyra's children are not legally bastards, but I have to admit comparing them to Henry II becoming heir after Stephen is a new one!

#sometimes an ask appears that makes you set aside all other waiting asks and immediately hop on it#asks#historical parallels#hotd discourse#hotd meta#team green#anti team black#anti rhaenyra targaryen

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Queens at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. For this reason, women such as Philippa of Hainault and Anne Boleyn have been omitted.

This list is composed of Queens of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707. Using the youngest possible age for each woman, the average age at first marriage was 17.

Eadgifu (Edgiva/Ediva) of Kent, third and final wife of Edward the Elder: age 17 when she married in 919 CE

Ælfthryth (Alfrida/Elfrida), second wife of Edgar the Peaceful: age 19/20 when she married in 964/965 CE

Emma of Normandy, second wife of Æthelred the Unready: age 18 when she married in 1002 CE

Ælfgifu of Northampton, first wife of Cnut the Great: age 23/24 when she married in 1013/1014 CE

Edith of Wessex, wife of Edward the Confessor: age 20 when she married in 1045 CE

Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror: age 20/21 when she married in 1031/1032 CE

Matilda of Scotland, first wife of Henry I: age 20 when she married in 1100 CE

Adeliza of Louvain, second wife of Henry I: age 18 when she married in 1121 CE

Matilda of Boulogne, wife of Stephen: age 20 when she married in 1125 CE

Empress Matilda, wife of Henry V, HRE, and later Geoffrey V of Anjou: age 12 when she married Henry in 1114 CE

Eleanor of Aquitaine, first wife of Louis VII of France and later Henry II of England: age 15 when she married Louis in 1137 CE

Isabella of Gloucester, first wife of John Lackland: age 15/16 when she married John in 1189 CE

Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of John Lackland: between the ages of 12-14 when she married John in 1200 CE

Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III: age 13 when she married Henry in 1236 CE

Eleanor of Castile, first wife of Edward I: age 13 when she married Edward in 1254 CE

Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I: age 20 when she married Edward in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, wife of Edward II: age 13 when she married Edward in 1308 CE

Anne of Bohemia, first wife of Richard II: age 16 when she married Richard in 1382 CE

Isabella of Valois, second wife of Richard II: age 6 when she married Richard in 1396 CE

Joanna of Navarre, wife of John IV of Brittany, second wife of Henry IV: age 18 when she married John in 1386 CE

Catherine of Valois, wife of Henry V: age 19 when she married Henry in 1420 CE

Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI: age 15 when she married Henry in 1445 CE

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Sir John Grey and later Edward IV: age 15 when she married John in 1452 CE

Anne Neville, wife of Edward of Lancaster and later Richard III: age 14 when she married Edward in 1470 CE

Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII: age 20 when she married Henry in 1486 CE

Catherine of Aragon, wife of Arthur Tudor and later Henry VIII: age 15 when she married Arthur in 1501 CE

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII: age 24 when she married Henry in 1536 CE

Anne of Cleves, fourth wife of Henry VIII: age 25 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Catherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII: age 17 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Jane Grey, wife of Guildford Dudley: age 16/17 when she married Guildford in 1553 CE

Mary I, wife of Philip II of Spain: age 38 when she married Philip in 1554 CE

Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI & I: age 15 when she married James in 1589 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I: age 16 when she married Charles in 1625 CE

Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II: age 24 when she married Charles in 1662 CE

Anne Hyde, first wife of James II & VII: age 23 when she married James in 1660 CE

Mary of Modena, second wife of James II & VII: age 15 when she married James in 1673 CE

Mary II of England, wife of William III: age 15 when she married William in 1677 CE

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

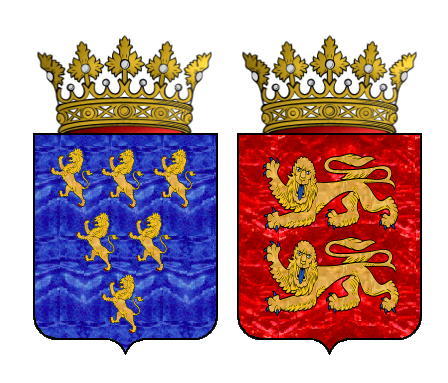

William, The Conqueror to Catherine, The Princess of Wales

⤜ The Princess of Wales is William I's 27th Great-Granddaughter via her paternal grandfather’s line.

William the Conqueror (m. Matilda of Flanders)

Henry I, King of England (m. Matilda of Scotland)

Empress Matilda (m. Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou)

Henry II, King of England (m. Eleanor of Aquitaine)

John I, King of England (m. Isabella of Angoulême)

Henry III, King of England (m. Eleanor of Provence)

Edmund, Earl of Lancaster (m. Blanche of Artois)

Henry, 3rd Earl of Leicester and Lancaster (m. Matilda de Chaworth)

Mary of Lancaster, Baroness Percy (m. Henry de Percy, 3rd Lord Percy) - Coat of Arms

Sir Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland (m. Margaret de Neville)

Sir Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy (m. Elizabeth Mortimer)

Sir Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland (m. Lady Eleanor Neville) - Coat of Arms

Sir Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland (m. Eleanor, Baroness Poynings) - Coat of Arms

Lady Margaret Percy (m. Sir William Gascoigne)

Agnes Gascoigne (m. Sir Thomas Fairfax) - Gawthorpe Hall, family seat.

William Fairfax (m. Anne Baker) - Gilling Castle, family seat.

John Fairfax (m. Mary Birch) Master of the Great Hospital at Norwich, Norfolk

Rev. Benjamin Fairfax (m. Sarah Galliard), Preacher at Rumburgh, Suffolk.

Benjamin Fairfax (m. Bridget Stringer) died in Halesworth, Suffolk.

Sarah Fairfax (m. Rev. John Meadows) died in Ousedon, Suffolk.

Philip Meadows (m. Margaret Hall)

Sarah Meadows (m. Dr. David Martineau)

Thomas Martineau (m. Elizabeth Rankin) buried at Rosary Cemetery, Norwich.

Elizabeth Martineau (m. Dr. Thomas Michael Greenhow) died in Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland.

Frances Elizabeth Greenhow (m. Francis Lupton)

Francis Martineau Lupton (m. Harriet Albina Davis)

Olive Christina Lupton (m. Richard Noel Middleton)

Peter Francis Middleton (m. Valerie Glassborow)

Michael Francis Middleton (m. Carole Elizabeth Goldsmith)

The Princess of Wales m. The Prince of Wales

#this took wayyy to long#princess of wales#william the conqueror#history#ancestry#pictures#people#brf#british royal family#empress matilda#henry ii#henry i#john i#king of england#henry iii#hotspur#KTD

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Now, Bishop Gervais so cherished Hugh, whom he had held on the baptismal font, that he sought for him the hand of the noblest lady Bertha, formerly wife of Alan, Count of Brittany.” This Alain had died in the year 1040. He had had a son from Bertha, the brave Conan, who was poisoned under the walls of Château-Gontier. Bertha was the daughter of Odo II, Count of Blois. "This greatly displeased Count Geoffrey," adds the annalist, "as the event proved. Hugh went with his men-at-arms to Bertha; Geoffrey ran to the Château-du-Loir and set it on fire. "In a charter that we have already mentioned (1), we find some details about the siege of the Château-du-Loir. Geoffrey did not seize it, but he ravaged the streets of the square, the village that surrounded it, and even a church founded in honor of Saint Guingalois, where Gervais had recently established canons. The soldiers of the Count of Anjou dispersed them. These actions,” we read in our manuscript, "now rendered the count to the bishop and the bishop to the count odious to each other. Geoffrey, therefore, seeing that, by the advice of Gervais, who wanted to harm and lose him, Count Hugh had taken a very powerful woman, and carrying Judas in his heart, called the bishop near him, in order to treacherously surprise him. Having seized him, he had him thrown into prison and held him in irons for seven years, hoping to thus make himself master of the Château-du-Loir. But it was of no use to him, because the castle was well defended by the garrison. While these things were going on, Count Hugh died, the bishop Gervais being still a prisoner. This death greatly afflicted the bishop and greatly delighted the Count of Anjou.” Count Geoffrey ruled the province for ten years. Indeed, the inhabitants of Le Mans having driven out the grieving widow of Hugh with her children through one of the gates of the city, had Count Geoffrey enter their walls full of joy.

- Jean-Barthélemy Hauréau, Histoire Littéraire du Maine: Tome 5

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Few figures experienced such a dramatic and disastrous turn of the wheel of fortune as did Eleanor of Aquitaine in the autumn of 1173, when she fell from her place as Henry’s assistant in ruling his collection of territories to detention as his prisoner in Chinon Castle. Eleanor inspired and participated in her sons’ rebellion of 1173–74 that became a widespread revolt against Henry. Spreading throughout his domains, it was the greatest challenge to his authority that he would face until his last days. The record of the royal couple’s sons for rebellions against their father and for fighting each other is almost unequaled in medieval history, and the queen’s active part in a revolt against her royal husband was near unimaginable to contemporaries. Writers ever since have accused the English queen of fomenting her sons’ rebellion, and the family’s troubles are still so notorious that they are a subject for films and plays. The chronicler Ralph Diceto writing not many years after the revolt admitted that young Richard, count of Poitou, and Geoffrey of Brittany in fleeing to Paris to join their elder brother in 1173 were “following the advice of their mother Eleanor.” He then listed over thirty instances of sons rebelling against their parents, but was unable to specify a single case of an earlier queen rebelling against her royal husband.

The dysfunctional character of the family life of Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II, and their sons was no secret to their contemporaries. One late twelfth-century monastic writer likened the English royal family to “the confused house of Oedipus,” and another commented that “this father was most unhappy in his most famous sons.” Courtiers at the English royal court could only explain the intense hostility by recalling an Angevin legend of the Plantagenet family’s diabolical descent, having as ancestor a demon-countess of Anjou. In fact, Henry was largely an absentee father during his sons’ early years, and following aristocratic custom, he was content to leave their upbringing in others’ hands. Once his sons became adolescents, they resented their father’s refusal to share power with them, denying them authority over the lands that he had designated for them in various partition schemes.

- Ralph V. Turner, “Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England”

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

@2kyears

“You are a distraction I don’t need,” Geoffrey told the dark-eyed boy lying next to him. “As much as I love a good bit of sodomy I am trying to fight a war with my brother. And so far the bastard is winning."

He sat and began pulling on his breeches. He like all of Henry II's sons thought of himself more as a soldier than a prince. But he wasn't a butcher. Granted he'd raided his share of monasteries to pay his men and fill their bellies with the fat larders only men of god seemed to have. But the Barons of Brittany had never rebelled against their young Duke though they had ample reason too. His father had made Conan IV their duke and they had hated him. When they rebelled Henry II disposed of him and seized the lands for himself before giving them to Geoffrey. The Bretons were proud and with long memories. They hated the upstart Count of Anjou but had no reason yet to hate his son, he'd been tremendously careful not to give them one.

His brother Richard on the other hand seemed to him a mad dog. He'd assumed the reports from the Aquitaine nobles given to him and his brother also named Henry were exaggerated. Now he knew they were not.

He stood and reached toward Maurice. "Be a good boy and get up, you're on my shirt."

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The psychological investment of medieval English royalty in their children seems generally not to have been great. Yet the family life of Henry II, Eleanor of Aquitaine and their children had more than most royal families’ share of hostility. The stormy relationship between Henry II and his sons is almost a classic example of father-son relations in feudal society. They saw him preventing their attaining full manhood with lands and authority of their own, and their resentment pushed them into rebellion. Henry was a restless man with a violent temper, and his sons often bore the brunt of his impatience and anger. The estrangement between Henry and his queen by 1170 must have had an effect on their children’s feelings, and the couple’s hostility can account for some of the boys’ lack of affection for their father. Once they reached adolescence, they lacked any loyalty to him; and their rebellions gave a tragic quality to his last years. […]

William of Newburgh, a northern chronicler, wrote of Henry II’s ‘inordinate love for his sons’ and accused him of trampling on others’ rights ‘while he exerted himself unduly for their advancement’. Yet little concrete evidence survives for Henry’s feelings toward his children except his schemes for succession to his lands. It is difficult to know whether Henry II was applying any principle in his partition of his territories, whether he had any vision of the Angevin domains as a unity or viewed them simply as a block of family lands to be used to provide for his offspring. Henry gave his sons honourific titles in 1169 when they were adolescents, hinting at an ‘Angevin empire’ with at least a loose structure held together by family ties. His eldest son and namesake, crowned king of England in 1170 at age fifteen, was to have the Anglo-Norman realm together with greater Anjou (Anjou plus Maine and Touraine); his second son, Richard, was proclaimed duke of Aquitaine, when he was fourteen; and Geoffrey became count of Brittany through marriage at age eleven; along with his continental county went the English earldom of Richmond. Little John ‘Lackland’ had no place in this tripartite partition. Most scholars agree that Henry II followed feudal custom in rejecting strict primogeniture succession of Young Henry to all his domains; he had both Angevin and Anglo-Norman precedent in feudal law for his scheme. Probably Henry held the hope that as his sons grew up, he could share the governing of the Angevin domains with them, withdrawing from day-to day work into something like ‘the chairman of a family consortium’.[…]

The birth of John in 1166 exacerbated relations between Henry II and his older sons, for he did not want his lastborn to remain ‘John Lackland’. His periodic new schemes for partition of his empire angered Young Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey, feeding their jealousy of each other and of their youngest brother. Such schemes especially aroused Richard’s resentment once his elder brother’s death promoted him to senior rank among the sons. Any younger son had uncertain prospects; and since Richard and Geoffrey were ahead of John in any division of Henry II’s acquisitions, his prospects were even less certain. He must have known from literature and from his own family’s history that the youngest of several sons often got nothing. Twelfth-century vernacular poetry is filled with tales of younger sons forced to leave home to seek their fortunes as knights errant. Insecurity about his future, rivalry with his brothers and awareness of their resentment over his father’s schemes to find land for him must have influenced John’s character. No youth growing up in such an atmosphere of suspicion and treachery could fail to absorb some poisons.”

— Ralph V. Turner, King John: England’s Evil King?

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

okay I just saw a Richard III stan on twitter claim that there's no way Elizabeth of York could have loved Henry VII because he was Ugly(tm) and so I just had to say/vent: the obsession with using physical attractiveness to unironically rate and compare historical figures is really fucking weird. This generally tends to happen with women (Henry VIII's wives in particular) but it's pretty common to see it with fans of Richard III as well, who are generally negative to Henry VII. Which is both very frustrating and very funny, because putting aside the generic compliments issued to royals, NEITHER of them were hailed as singularly attractive or singularly charismatic during their time as far as I know, they both looked like Some Guys who ruled the nation and (in Henry's case, idk much about Richard's reign) were quite good at it. And in Henry's case, its doubly weird and mean-spirited because I believe he was sick when his portrait was being made?

I mean, it's certainly not as though someone insulting a historical monarch's physical appearance is a major crime or anything lol, you do you, but it does become an issue when it spills into an analysis and examination of them as rulers and individuals. There's really no need to turn important periods of history into a hotness contest.

Also (more of a general rant), generally speaking, attractiveness was a feature conveniently assigned to most people of high status, and was almost a exaggerated. It's also relatively easy to identity genuine undeniable attractiveness based on the sheer intensity and awe with which contempraries raved about the people who possessed it (Elizabeth Woodville, Edward IV and all their children were key examples of that lmao, as well as geoffrey of anjou and Philip iv of France as far as men were concerned), which was usually quite rare because the majority of people were not supermodels and were not expected to be lmao.

(a bit irrelevant, but I feel like the guy who played Henry in the white princess was absolutely perfectly for a younger version of his portrait, I haven't watched the show but I absolutely loved his casting)

Oh, I think Jacob Collins-Levy does look like a young Henry VII indeed, even if a more 'polished' version of him. Certainly, I think the real Henry VII had a much stronger nose, which leads me to the main part of your comment: some people find big noses attractive, for example. People experience attraction in such different ways! Someone might be attracted to another person's voice or hands, to someone's attention to detail or alternatively to their carefree attitude, to someone's jokes or their way of speaking or caring for their family or someone's intellect and insight. Attraction is a vast and varied universe, and to me it seems quite childish to reduce it only to someone's facial features. We don't even know what his body looked like, for example; we only have Vergil's word that his height was 'above the average', and Bishop Fisher's word that Henry was 'tall and of a fine build'.

Even if you consider Henry Tudor to have been the ugliest man in the world (which I doubt, as he was described as 'remarkably attractive' in his later years still), it's quite possible there was something about him that charmed people around him, in the sense that he was able to inspire extraordinary loyalty throughout his life. Thomas More said Bishop Foxe would give up his own father's head in order to serve Henry VII; Thomas Lovell was reported to have only one painting in his multiple residences, precisely a portrait of Henry VII. Henry was able to inspire and retain the trust of 400 Englishmen for two years in exile. The same thing that was attractive to his followers might have been attractive to Elizabeth of York as well, surely? We don't know!

According to a Venetian ambassador, Henry was 'gracious and grave', and according to Commynes, he was 'very pleasant, an elegant character, and a fine ornament in the court of France'. Once, during a conversation with the Spanish ambassador, his speech was described as 'like precious jewels'. I find it doubtful that Henry VII was an all-around unlikable, unattractive figure. And that's simply going by the premise that he was extraordinarily ugly, though when compared to other European rulers at the time, it seems reasonable to call him 'just some guy', if not actually attractive (see Charles VIII, Maximilian I, Louis XII, Ferdinand of Aragon, and even Philip 'the Fair').

I linked portraits in this ask but I don't even believe they are much conducive to a good discussion on attractiveness at all. It's not uncommon to find that many figures who were described as handsome/attractive (eg: Philip the Fair) don't actually look handsome/attractive to a 21st-century audience. And that might be simply because portraits or painting techniques of the time weren't able to transcribe their real physical attractiveness to us or because their ideas of attractiveness were different from ours—to which I ask: what's even the point of using portraits to call a historical figure attractive or unattractive, then? It's perhaps more useful to go by awed reports of a certain historical figure's attractiveness, as you said, and even then, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The resident Spanish Ambassador in England, for example, never once mentioned Elizabeth of York's looks in fifteen years, even though her beauty was mentioned elsewhere by other people.

Those types of comments against Henry VII do sound mean-spirited, as you said, even if not especially heinous (he and his family are, after all, dead). It's a sterile argument and proves no point as to a historical figure's ability to inspire loyalty or love in someone else, and even less as to their ability to rule well. If anything else, quite frankly it's not an argument at all, it's just the expected pettiness of a bad loser lol It gets even weirder at their insistence that Richard's reconstruction is especially handsome (which has inspired even some... questionable poetry).

(x)

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

Pls upload the one with Geoffrey le bel

One Foxy Grandpa coming right up 🌱🌼 ...he can be your angel or yuor Angevin devil

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Lion in Winter (1968)

directed by Anthony Harvey

Peter O'Toole

as Henry II, King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and of Aquitaine, Count of Anjou

Katharine Hepburn

as Eleanor of Aquitaine

Anthony Hopkins

as Richard the Lionheart

John Castle

as Geoffrey

Nigel Terry

as John

Timothy Dalton

as Philip II, King of France

Jane Merrow

as Alais

#peter o'toole#the lion in winter#katharine hepburn#anthony hopkins#john castle#nigel terry#timothy dalton#jane merrow

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite History Books || Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen by Kathryn Warner ★★★★☆

Isabella of France (c. 1295–1358), who married Edward II in January 1308, is one of the most notorious women in English history. In 1325/26, sent to her homeland to negotiate a peace settlement to end the war between her husband and her brother Charles IV of France, Isabella refused to return to England. She began a relationship with her husband’s deadliest enemy, the English baron Roger Mortimer, and with her son the king’s heir under their control, the pair led an invasion of England which ultimately resulted in Edward II’s forced abdication in January 1327. Isabella and Mortimer ruled England during the minority of her and Edward II’s son Edward III, until the young king overthrew the pair in October 1330, took over the governance of his own kingdom and had Mortimer hanged at Tyburn and his mother sent away to a forced but honourable retirement. Edward II, meanwhile, had died under mysterious circumstances – at least according to traditional accounts – while in captivity at Berkeley Castle in September 1327.

Though she was mostly popular and admired by her contemporaries, her disastrous period of rule from 1327 to 1330 notwithstanding, Isabella’s posthumous reputation reached a nadir centuries after her death when she was condemned as a wicked, unnatural ‘she-wolf’, adulteress and murderess by writers incensed that a woman would rebel against her own spouse and have him killed in dreadful fashion, or at least stand by in silence as it happened (the infamous and often-repeated ‘red-hot poker’ story of Edward II’s demise is a myth, but widely believed from the late fourteenth century until the present day). Isabella’s relationship with Roger Mortimer and her alleged sexual immorality, as well as her frequently presumed but never proved role in her husband’s murder, became a stick often used to beat her with; a typical piece of Victorian moralising by Agnes Strickland declared that ‘no queen of England has left such a stain on the annals of female royalty, as the consort of Edward II, Isabella of France’. Strickland’s work divided the queens of England, seemingly fairly arbitrarily, into the ‘good’ ones such as Eleanor of Castile and Philippa of Hainault, and the ‘bad’ ones such as Eleanor of Provence; Isabella of France, naturally, fell into the second category. Her reputation fared poorly between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and well into the twentieth: in the early 1590s the playwright Christopher Marlowe called her ‘that unnatural queen, false Isabel’, a 1757 poem by Thomas Gray was the first to apply the ridiculous ‘she-wolf’ nickname (which had been invented by Shakespeare for Henry VI’s queen Margaret of Anjou) to her, and in 1958, exactly 600 years after her death, Isabella was still being called ‘the most wicked of English queens’. The French nickname sometimes used for her, la Louve de France – the title of a 1950s novel about her by Maurice Druon – is simply the translation of the English word ‘she-wolf’ and has no historical basis whatsoever. (Although it is sometimes claimed nowadays that Edward II himself, or his favourite Hugh Despenser the Younger, called Isabella a ‘she-wolf’, this is not true; one fourteenth-century chronicler, Geoffrey le Baker, called her Jezebel, a play on her name, but otherwise no unpleasant nicknames for her are recorded until a few centuries after she died.) An academic work of 1983 unkindly calls Isabella a ‘whore’, and a non-fiction book published as late as 2003 depicts her as incredibly beautiful and desirable but also murderous, vicious and scheming, and claims without evidence that she ‘had murder in her heart’ towards her husband in 1326/27, called for his execution and was ‘secretly delighted’ when she heard of his death. Her contemporaries were mostly kinder. With the notable exception of Geoffrey le Baker in the 1350s, who was trying to promote Edward II as a saint and who detested Isabella, calling her an ‘iron virago’ as well as ‘Jezebel’, fourteenth-century chroniclers generally treated her well, and it is certainly not the case, as is sometimes claimed nowadays, that they called her a ‘whore’ or anything equally ugly and harsh because of her liaison with Roger Mortimer. Most fourteenth-century chroniclers seem uncertain whether Isabella even had an affair with Mortimer at all, and a few depict the two merely as political allies and call Mortimer Isabella’s ‘chief counsellor’, which may be a more accurate portrayal of their association than the romanticised accounts so prevalent in modern writing. In the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, writers have mostly been keen to write Isabella sympathetically and rescue her from the unfair calumnies heaped on her head for so long – an impulse to be applauded – but in doing so have tended to go too far in the opposite direction. As a result, Isabella is depicted nowadays as a tragic, long-suffering victim of marital cruelty, impoverished and deprived of her children, who is miraculously transformed in 1326/27 into a strong, empowered feminist heroine bravely fighting to end the oppression of her husband’s subjects and to get her children back. This is no more accurate than the old tendency to write her as an evil she-wolf.

Portrayals of Isabella of France down the centuries say far more about the societies that produced them and the prevailing attitudes towards women and their sexuality, in particular women who step outside the bounds of traditionally conventional behaviour, than they do about Isabella herself. For all the piles of chronicles, non-fiction books, novels, plays, poems and articles written about the queen over the last 700 years, have we come close to knowing the real Isabella at all, or has she only ever been an image of what we think she must have been like, formed from our own experiences and cultural expectations? Can we discover the real Isabella underneath the centuries of myth? The queen would surely not recognise herself and the events of her life in the way she has so often been portrayed: either as a malevolent and vengeful murderer, or as a despondent martyr treated appallingly for many years by her despised husband and his lovers, or as a time-traveller parachuted into the Middle Ages from the twenty-first century with modern attitudes towards sexual equality. Isabella was far more complex: neither wicked nor saintly, she was a fascinating human being with both excellent qualities and flaws, who did laudable things and other things not so praiseworthy. She was a product of her time and place – Europe in the fourteenth century – intensely proud of her royal birth and high position, steeped in Christianity, taught that she must marry in a political alliance to benefit her father’s kingdom and happy to do so, taught also that she must obey her husband and bear his children.

#historyedit#litedit#isabella of france#house of capet#house of plantagenet#medieval#french history#english history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics#history books

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fitzempress sons and the velaryon boys

the term fitzempress was born from the fact that empress matilda, in her first marriage, was made empress of the holy roman empire. she never let go of that title even in remarriage - due to her husband being a mere count. she passed this sense of importance to her three sons. her sons had multiple names and monikers but the title fitzempress stuck the longest, especially with henry ii's two younger brothers. the name is deeply close to henry ii as it is his mother who he proudly descended from to inherit the throne of england.

the term velaryon boys was used to refer to the sons of rhaenyra targaryen and laenor velaryon. through their royal and noble parents, they are the known heirs to house targaryen and house velaryon. however, when their mother rhaenyra ascends to the throne - their eldest son, jacaerys velaryon would change his last name to targaryen, to continue the royal line. while lucerys velaryon would be the one to inherit driftmark and continue house velaryon. the youngest of the three sons, joffrey velaryon would also retain the velaryon name.

jacaerys velaryon - henry fitzempress, henry ii.

jacaerys's character is heavily influenced by who henry ii, eldest son of matilda, was. henry ii was the most intelligent and dutiful of matilda's sons. he had been a educated by great tutors in his mother's household. his father sent him to his uncle robert of gloucester to have his education in england. there, he was raised with canons of the church who were all prolific academics at the time. he got the best education that is fit for a son of the empress, a future king of england.

he understood many languages but spoke latin and french. he was energetic and zealous and was athletic and liked hunting as a young man. he was also stubborn and strident. from a young age involved in the running of their family's endeavours, taught how to run his father's lands. he was also known to be someone who was fair, he raised people above their station based on merit rather than by station and was also very concerned for the common folk, having emptied his own private stores to aid his people during a famine in 1176.

jacaerys velaryon is the same. he was educated on dragonstone by his mother, where he grew up. he was considerably known to be robust young boy, who was also known to be quite fair in looks. as his mother's royal heir, we know that he would have been educated well as a prince of the realm with trusted maesters and educators his mother would have been able to find.

we do see in the show, where jacaerys is learning high valyrian - he determined to get everything right. and was stubborn and stern in the show. it is also to be known that in the books, jacaerys was well adept at using arms, becoming a prolific squire at his young age.jacaerys was responsible and bold, he was considered savy at his politics and was one to not care about the station of others. he himself was the person who led the venture for dragonseeds, whom all came from various backgrounds. he also led the family throughout the war.

henry ii and jacaerys were heavily influenced by their ancestral descendency. henry ii wanted to rebuild the kingdom his grandfather worked to hold together. we see that in the show elaborated on, where jacaerys declares he should learn in order to bring honor to his ancestors. both of them were married or was to marry women of great beauty, strength and power. henry married eleanor of aquitaine, who held the duchy of aquitane in her own right and ruled with him. jacaerys was set to wed baela targaryen, who was to be his queen and dragonrider like him.

lucerys velaryon - william fitzempress

william fitzempress was born the third son of empress matilda and geoffrey of anjou. william as a third son was never really set to inherit anything but he's considered a smart young man and was martially inclined, reading tactics often.he was studied tactics like that of roman military theorist vegetius and used that against his elder brother geoffrey when he occupied one of their family's castles. as he was the brother who shared similarities to his brother and because he most loyal, henry ii favoured him. at one point, henry ii had a council convened to propose the invasion of ireland - where he planned to make him king. but their mother opposed, as she thinks it is not worth conquering.

william fitzempress was born the third son of empress matilda and geoffrey of anjou. william as a third son was never really set to inherit anything but he's considered a smart young man and was martially inclined, reading tactics often.he was studied tactics like that of roman military theorist vegetius and used that against his elder brother geoffrey when he occupied one of their family's castles. as he was the brother who shared similarities to his brother and because he most loyal, henry ii favoured him. at one point, henry ii had a council convened to propose the invasion of ireland - where he planned to make him king. but their mother opposed, as she thinks it is not worth conquering.

instead, henry ii made up to his brother by giving him land, wealth and titles. when he was in his mid 20s, he was set to wed isabel de warenne, countess of surrey who was a rich heiress. however their marriage required a dispensation due to their close affinity. thomas becket, who was archbishop of canterbury refused to help - he and king were at odds.unfortunately, william died suddenly - they said of a broken heart at the age of 27. henry ii was distraught at his brother's death and blamed becket- furthering conflict. when becket wss murdered by knights under henry ii's employ, they screamed of vengence for william's death.

lucerys velaryon was the second son of rhaenyra targaryen and laenor velaryon. unlike william, laenor and his father made lucerys heir to driftmark at his birth. lucerys was just as robust like his elder brother lucerys whom he was close with which we saw elaborated on the show. as elaborated on by the show, lucerys is warm hearted and kind. just as william proved, lucerys is loyal to his family to a fault even against other kin. like william,

he also is for his martial skills being known for being adept at using arms just like his elder brother. lucerys in the show was someone who shunned power, but did his duty. just like william, he knew his duty and his place was to support henry ii's rule as king - lucerys made sure to support his own mother queen rhaenyra during the dance of the dragons as a dragonrider and envoy. like william, lucerys velaryon suddenly died young after his uncle aemond killed him and his dragon arrax over the skies of storm's end. his death just like william's, lead to the deepening of horrors to come. and just like william, lucerys velaryon's death was avenged brutally.

joffrey velaryon - geoffrey fitzempress, count of nantes

geoffrey fitzempress was born the second son of empress matilda and geoffrey of anjou. he was named in honor of his father during the war as his mother was off in england, defending her claim to the throne. as he grew up with his father, it was the count of anjou who chose how his son was to be raised however we know little of what went through on in geoffrey's life at this time due to lack of records. still, when his father passed, it was thought that he was his father's heir. being a second son, this meant that should his elder brother claim normandy or england, anjou would be ceded to geoffrey.

however his brother henry ii did not cede the lands to his brother and instead, when he turned 16, young geoffrey became count of nantes. geoffrey considerably was eager to prove himself as powerful and worthy. he often did this by making plots. he would occupy castles and force his brothers to siege them. he also tried to plot to get eleanor of aquitaine to wed him however that failed completely. geoffrey however always made up with his family quite often, even escorting his brother henry ii and his newly wedded wife eleanor back to england around the same time. he continued to try and prove himself and fought his brothers - ending up dying young suddenly aged 24.

joffrey velaryon was born to rhaenyra targaryen and laenor velaryon as their third and last son. just like geoffrey, the youngest son was named to honor someone. in joff’s case, it was his father's departed lover and friend, joffrey lanmouth. just like his elder brothers, joff was also born robust of body. like his historical counterpart, we know very little about how he grew up after the incident in driftmark, both book and show. however we know that joffrey is a loyal and honest boy, having fought off his uncle aemond from claiming vhagar during his father's funeral. that being said, unlike his historical counterpart, joffrey velaryon was a third son. however, both are certainly in the same predicament, which is that their position as a member of their family is yet to be determined.

however joffrey was eager to do well and prove himself worthy of being his mother's son just like geoffrey. the difference however is their approach towards it. while geoffrey favored trying to fight his family to attain glory, joffrey velaryon was resolute to prove himself by fighting for his family and ensuring that he contributes to their family's success in the war - in order to make his mother queen and avenge his departed family. however just like geoffrey, the youngest velaryon son was destined to die young. while we do not know how geoffrey fitzempress died, he did not perhaps die so miserably and horribly like joffrey did. but unlike geoffrey, joffrey velaryon died trying to serve his family.

#fire and blood#asoiaf#house of the dragon#hotd#f&b#jacaerys velaryon#lucerys velaryon#joffrey velaryon#medieval history#henry ii of england#wiilliam fitzempress#geoffrey fitzempress

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Capétiens vs Plantagenêts: a matter of suzerainty.

It was also his position as suzerain which gave Louis VII the chance of interfering in and inflaming the quarrels which raged in the Angevin family. This was an effective means of weakening his great antagonist. Henry II and Eleanor produced a large family, and reared four of their sons to the age at which custom demanded that they should be provided for. Their eldest son Henry was granted Normandy in October 1160 and was associated with his father on the throne of England in 1170. Richard was given Aquitaine in 1169 and Geoffrey Brittany in 1175. John, the youngest child of Henry and Eleanor, was not old enough to be entrusted with any estates until the very last years of his father's reign, and by the time he came of age all the available lands had been given away. As Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Count of Poitiers, the sons of Henry II came to perform homage to the King of France and became his men. It was in vain that Henry II sought to utilise the Norman procedure of pariage to maintain the unity of his continental territories in favour of his eldest son, the "Young King" Henry. (Under pariage the eldest son succeeded to all the heritable property and was alone answerable for it to the suzerain; each of his brothers received a share, but held it of him). This device could not be put into full operation in Aquitaine, which was not part of Henry's heritage but Eleanor's. And when she granted it to Richard, he owed homage not to his father or his eldest brother, but to the King of France. The Young King Henry had done homage as Duke of Normandy to Louis VII in October 1160. When he repeated his homage in 1170 it was made to embrace Anjou, Maine, and Brittany as well. At the same time Richard did homage to Louis for Aquitaine.

It is true that in 1174 Henry II compelled his sons to perform homage to him after their rebellion, but this new homage did not necessarily annul their homages to the King of France. Henry II himself had done homage to Louis VII in 1151 and again in 1169, and was to perform it yet again to Louis's successor, Philip Augustus, in 1180. Thus throughout the conflict between Louis VII and Henry II the French king's suzerainty was affirmed and recognised. This did not save Louis from defeats at his vassal's hands. Nevertheless, to judge from the Toulouse affair in 1159, Louis' suzerainty occasionally cramped Henry's style, and put him in the wrong in the eyes of contemporaries, including the barons of his continental fiefs. To play the rebel vassal was hardly prudent for a king when many of his own vassals were rebelliously inclined. It was not that the idea of rebellion itself shocked feudal society. On the contrary, it was one of the legitimate courses open to a vassal needing to safeguard his rights against the encroachments of his suzerain. But in the disputes between Louis VII and Henry II, Henry was the law-breaker as well as the vassal in revolt. For his rebelliousness against an impeccable suzerain there could be no justification.

It may be objected that Louis VII was constantly intriguing with Eleanor of Aquitaine and with Henry II's sons. But after all Eleanor, as Duchess of Aquitaine, was herself a royal vassal. Two of Henry's sons had done homage to Louis. Another, Geoffrey, by dint of his father's vassalage, was the French king's rear-vassal. And the king had, as suzerain, not merely the right but the duty to concern himself with the welfare and harmony of his great vassal's family, to ensure that a proper settlement was made on the sons. It would be unfair to accuse Louis of hypocrisy; nor did Henry ever complain that the French king was making trouble in his family. Louis' own grievances against Henry were many and varied, and Henry never made a serious effort to deny their validity.

Thus from 1154 to 1180 Henry II had the appearance of a vassal engaged in unjustifiable revolt against his suzerain. This line of conduct undermined his own position. It constantly reminded the baronage of the Angevin fiefs that the King of France was Henry's suzerain- if only because his suzerainty was so often invoked. And it helped to prevent the fusion of the individual elements of the Angevin empire on the continent. Provincial separation, already too strong for Angevin rule to subdue, was reinforced.

Robert Fawtier- The Capetian Kings of France

#xii#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#louis vii#henry ii of england#aliénor d'aquitaine#henry the young king#richard the lionheart#geoffrey plantagenêt#john lackland#jean sans terre

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

hotd & the anarchy

I did a poll recently about how much people knew about the Anarchy, a period of civil war in early English history, and most people said they were not familiar with it, or not very familiar. I was originally going to do a really long post explaining all the historical context, but let's be real, you have access to wikipedia and nothing I'm going to say is going to be more researched than a wiki entry. what I can do for you is put it down quickly and easily, so! the anarchy, and what it has to do with asoiaf / hotd / the conflict known as the Dance of Dragons* in Fire & Blood.

*From here on, when I'm referring to the Dance of Dragons, I'm specifically referring to the events that take place in F&B, not the book with the similar name in the main ASOIAF series.

THESIS:

the Dance of Dragons is based on the Anarchy.

making Rhaenyra based on, or at least inspired by, Empress Matilda.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN:

The way the Anarchy ends historically is extremely similar to how the Dance of Dragons conflict ends in Fire & Blood, and will probably have some bearing on the ending of HOTD. So stop reading if you want to avoid spoilers.

WHAT ARE THE SIMILARITIES BETWEEN THESE CONFLICTS?

The granddaughter of William the Conqueror (the obvious basis for Aegon the Conqueror), Empress Matilda was a really interesting historical figure who isn't well-remembered today, which is a shame because her life was batshit interesting.

Below is a very (very!) brief overview of her actions, and how they compare to the events in the Dance of Dragons:

While Matilda's father King Henry I had many children, he only had two in his legal marriage. One was the prince and heir, and one was Matilda.

The prince, and about 298 other people, fucking died in the White Ship Disaster. (The White Ship Disaster is really interesting in and of itself and I could go into more detail, but you ain't here for that, so I'll spare you. But at least give the Wikipedia page a look if you're interested in bizarre episodes in royal history. Anyway, moving on!)

Daddy needs an heir! He grabs his daughter - who had been married to the Holy Roman Emperor (thus the title Empress) - and made all the lords in England and Normandy swear to accept her as heir.

(exactly like Viserys does with Rhaenyra)

Matilda is extremely hesitant to marry - after an emperor (he's dead now), everyone's a kind of a letdown. Eventually, she marries a foppish French duke, Geoffrey V of Anjou. (This is where the Angevin dynasty started, for those keeping track.)

(could Geoffrey V be an inspiration for Laenor? Entirely possible! I do think one of Rhaenyra's kids being named Joffrey is a homage; Matilda's second son was named Geoffrey after his father.)

When King Henry I dies, Matilda is away in Normandy with her family.

(similar to how Rhaenyra is away at Dragonstone when Viserys dies)

Matilda's cousin Stephen of Blois takes this opportunity to crown himself king as the eldest male heir.

(could Stephen of Blois be an inspiration for Daemon? I think it's possible - at the very least, the Dance of Dragons feels partially like a what-if scenario: what if Matilda had been able to shore up her support by marrying another male heir? What if Henry I had more legal children? etc)

When Matilda finally comes back to England, she does so with full military force, and the conflict between her and Stephen's forces plunge England into a period of war so bad it's commonly known as 'the Anarchy', because no one was in charge.

(Similarly, the period of civil war between the Greens and the Blacks gets its own soubriquet, though, in the Fire & Blood book, it's noted that the 'Dance of Dragons' name is too poetic and hides the real bloodshed)

During this conflict, Stephen's wife - also named Matilda, but we'll call her Maud to differentiate - briefly commands some troops in London; Maud is held up by contemporary sources as an ideal woman for her daring and bravery... things that Matilda is castigated for in the same sources.

(This is, to me at least, similar to how Alicent is treated vs Rhaenyra, because Alicent tries to work more within the extant political systems - only claiming power for male heirs, not herself etc - while Rhaenyra does similar but is seen negatively for it. I do think that Maud is a partial inspiration for Alicent.)

Neither Matilda nor Stephen are ever able to completely claim victory over each other, and eventually, the war ends in a stalemate.

By this time, Matilda's son Henry II is grown. (This is the Henry II who married Eleanor of Aquitaine and is played by Peter O'Toole in The Lion in Winter, for those keeping track.)

Matilda stops trying to claim power for herself and begins putting her son forward as heir. Henry II is an excellent commander who becomes known to the people of England. When peace talks with Stephen finally begin, they're between Stephen and Henry; Matilda stays in France.

Eventually, Stephen agrees to declare Henry II as his heir, and it goes smoothly enough; Henry II is king of England.

(This is similar to how Rhaenyra never definitively 'wins' the dance of dragons, but her son is king.)

tl;dr the clear similarities between these two events, one historical and one fictional, point to GRRM's interest in medieval history and his continued use of it as a source of inspiration in building out Westeros. I think his tragic ending for Rhaenyra is extremely intentional because it reflects Matilda's real life.

3 notes

·

View notes