#Gomer and other Early Works

Text

‘M*A*S*H’ at 50: War Is Hell(arious)

Five decades ago, “M*A*S*H” anticipated today’s TV dramedies, showing that a great comedy could be more than just funny.

“M*A*S*H,” which debuted in September 1972, feels both ancient and current. With Jamie Farr, seated, and, from left, Mike Farrell, David Ogden Stiers, Alan Alda, Loretta Swit, Harry Morgan and William Christopher in a later season.Credit...CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

By James Poniewozik

Sept. 16, 2022 Updated 10:59 a.m. ET

The pilot episode of “M*A*S*H,” which aired on Sept. 17, 1972, on CBS, lets you know immediately where and when you are. Sort of. “KOREA 1950,” the opening titles read. “A HUNDRED YEARS AGO.”

The Korean War could indeed seem a century away from 1972, separated by a gulf of cultural change and social upheaval. But as a subject, it was also entirely current, given that America was then fighting another bloody war, in Vietnam. The covert operation “M*A*S*H” pulled off was to deliver a timely satire camouflaged as a period comedy.

The year before, CBS had premiered Norman Lear’s “All in the Family,” a battlefield dispatch from an American living room. But “M*A*S*H” was another level of escalation, sending up the lunacy of war even as Walter Cronkite was still reading the news about it. The caption acknowledged the risk by winking at it: Who, us, making topical commentary?

Today, “M*A*S*H” also feels both like ancient history and entirely current, but for different reasons.

On the one hand, in an era that’s saturated with pop-culture nostalgia yet rarely looks back further than “The Sopranos” or maybe “Seinfeld,” “M*A*S*H” is often AWOL from discussions of TV history. Sure, we know it as a title and a statistic: The 106 million viewers for its 1983 finale is a number unlikely to be equaled by any TV show not involving a kickoff. But it also gets lost in the distant pre-cable mists, treated as a relic of a time with a bygone mass-market TV audience and different (sometimes cringeworthy) social attitudes.

Yet rewatched from 50 years’ distance, “M*A*S*H” is in some ways the most contemporary of its contemporaries. Its blend of madcap comedy and pitch-dark drama — the laughs amplifying the serious stakes, and vice versa — is recognizable in today’s dramedies, from “Better Things” to “Barry,” that work in the DMZ between laughter and sadness.

For 11 seasons, “M*A*S*H” held down that territory, proving that funny is not the opposite of serious.

Alda’s Hawkeye was a forerunner of the modern dramedy antihero.Credit...CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

Off the beaten laugh track

The characters serving in the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in Korea were professionals whose vocation was to save lives. But their assignment was to patch up soldiers so that they could return to the front lines and kill other people or get killed themselves. This was the eternal, laugh-till-you-cry joke of “M*A*S*H.”

“M*A*S*H” stepped into, and outside of, a tradition of military sitcoms. “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.” and “The Phil Silvers Show” poked fun at the hardships and hustles of life in uniform; “Hogan’s Heroes,” which preceded “M*A*S*H” from 1965 to 1971 on CBS, was about shenanigans in a Nazi P.O.W. camp. But as for the abominations of war, these sitcoms, like the bumbling Sgt. Schultz of “Hogan’s,” saw nothing.

Only three years earlier, CBS had canceled the successful “Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” amid controversy over its antiwar stances. But by the early 1970s, even die-hard anticommunists saw Vietnam as a lost cause. Pop culture was changing, too, as evidenced by the success of “All in the Family” and of Robert Altman’s 1970 film “M*A*S*H,” based on a novel by Richard Hooker (the pseudonym of H. Richard Hornberger).

The show’s creators, Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds, imagined a version of the story that was more pointedly political than Altman’s dark-comic film, and certainly more so than Hooker’s cheerfully raunchy book.

The staff of the 4077th, mostly draftees, channeled their frustration with their situation into pranks, drinking, adultery and gallows humor. The insubordinate-in-chief was Capt. Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce (Alan Alda), who was dead-serious about surgery and dead-sarcastic about every other aspect of the wartime experience.

Casting Alda as the ensemble’s moral center and chaos agent was key. He could caper on set like the love child of Bugs Bunny and Groucho Marx (Hawkeye would imitate the latter while making rounds with patients). He gave Hawkeye’s flirtations with nurses a bantering lightness (though from a half-century’s distance, they can come across more like straight-up harassment).

But Alda also conveyed Hawkeye’s exhausted spleen, which the doctor poured into letters to his father in Maine, a frequent episode-framing device: “We work fast and we’re not dainty,” he writes in the pilot. “We try to play par surgery on this course. Par is a live patient.”

“M*A*S*H” borrowed bits from its sitcom predecessors. It was a workplace comedy, with a goofy boss, Lt. Col. Henry Blake (McLean Stevenson), and uptight antagonists, like the gung-ho lovers Maj. Frank Burns (Larry Linville) and Maj. Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan (Loretta Swit). The staff wrestled with bureaucracy and gamed the system, as when the hyperefficient company clerk, Cpl. Walter “Radar” O’Reilly (Gary Burghoff) mailed a jeep home one part at a time.

But the zaniness came with constant reminders that the realities of war could intrude at any moment, like the incoming choppers ferrying the wounded. The producers pushed CBS to dump the laugh track — what’s a studio audience doing in the middle of a war zone? — and eventually compromised on shutting off the yuk machine during operating-room scenes.

The show earned its belly laughs and its quiet. Even the sitcom-standard high jinks — dealing with the black market for medicine, inventing a fictional officer in order to donate his pay to an orphanage — were forms of protest.

In Season 1’s “Sometimes You Hear the Bullet,” Hawkeye meets a writer friend, doing research on the war, who later turns up on the operating table with a mortal wound. The executive producer Burt Metcalfe told the Hollywood Reporter that a CBS executive said, at the end of the season, that the episode “ruined ‘M*A*S*H.’”

The show would run for another 10 years.

“M*A*S*H” shows its age in various ways, including in a subplot in which Farr’s Klinger sought discharge from the Army by dressing in women’s clothes.Credit...CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

Comedy meets dramedy

“From any angle, ‘M*A*S*H’ is the season’s most interesting new entry,” the critic John J. O’Connor wrote in The Times in September 1972. Audiences came around in Season 2, after CBS moved the show to a better time slot. It spent most of the next decade in the ratings Top 10 (even as its own timeline hopscotched among different points from 1950 to 1953).

The early seasons worked in a vein of joke-heavy dark comedy, branching out into more story forms and social issues. A Season 2 episode involved a gay patient, decades before Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, who had been beaten up by other soldiers in his unit. (“M*A*S*H” had its share of gay-tinged jokes — as well as a long-running subplot about Jamie Farr’s Cpl. Max Klinger trying to win a discharge by dressing as a woman — but they usually played as banter rather than gay panic.)

Then, in the Season 3 finale, the series exploded a land mine. Stevenson had signed a deal with NBC, and Henry was written off in affectionate sitcom style, with goodbyes and a party. In the episode’s closing moments, Radar — a farm kid who saw Henry as a father figure — walks into the operating room to read a bulletin: “Lt. Col. Henry Blake’s plane was shot down over the Sea of Japan. It spun in. There were no survivors.”

Henry’s death kicked off the series’s peak era, in which it evolved from a lacerating comedy into something closer to what we would recognize today as dramedy.

The new commanding officer, Col. Sherman Potter, was a career Army man, played by Harry Morgan, once Jack Webb’s stoic sidekick in the revival of “Dragnet.” (Morgan played a crackpot general earlier in “M*A*S*H.”) More competent and less malleable than Henry, Potter had a gravitas befitting a show that was growing in ambition.

The Kafkaesque absurdism deepened, too, as in “The Late Captain Pierce,” in which Hawkeye is declared dead in a bureaucratic mix-up and tries to exit the war on a morgue bus. “I’m tired of death,” he says. “I’m tired to death. If you can’t lick it, join it.”

The experimental episode formats became more daring. “Point of View” is shot from the vantage of a wounded soldier whose throat injury renders him mute. In a repeated format, a reporter visits the 4077th for the new medium of television. The unit’s chaplain, Father Francis Mulcahy (William Christopher), described seeing surgeons cut into patients in the winter cold. “Steam rises from the body,” he says. “And the doctor will warm himself over the open wound. Could anyone look on that and not feel changed?”

Just as important, the show evolved its supporting characters, especially Margaret, spoofed as a harpy and sex object in the early seasons. In a Season 5 episode, she vents to her subordinate nurses about the pressures that have made her into the stickler they know. Eventually, she becomes a more complex foil and ally.

Swit and Larry Linville in the first season of “M*A*S*H.” Her character, Margaret, became more complex as the show went on.Credit...CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

The hilarious but one-dimensional Frank even earns some sympathy before his eventual exit, as Margaret throws him over for a fiancé. He’s replaced by the snobby, intelligent Boston Brahmin Maj. Charles Emerson Winchester (David Ogden Stiers), while Hawkeye’s partner-in-pranks Capt. “Trapper” John McIntyre (Wayne Rogers) makes way for the dry, laid-back family man Capt. B.J. Hunnicutt (Mike Farrell).

Even in the matured version of “M*A*S*H,” a lot has aged badly. A largely male story, it subscribed to the kind of counterculturalism that saw sexual freedom mostly as license for men. For much of the show’s run, various minor nurse characters were so interchangeable that they were repeatedly named “Able” and “Baker” — literally, “A” and “B” in an older version of the military phonetic alphabet.

Ironically, Alda — an outspoken Hollywood feminist and co-star of “Free to Be … You and Me” — became a disparaging shorthand for “sensitive men” among gender reactionaries in the “Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche” era. Late in the show’s run, “M*A*S*H” intermittently interrogated its own attitudes toward women, as in “Inga,” a Season 7 episode with Mariette Hartley as a Swedish doctor whose brilliance Hawkeye finds threatening.

Those later years of “M*A*S*H” could be didactic, and few fans would consider them among its best. The camp got cleaner and the hairstyles suspiciously modern. The show’s heart got as soft and the stories as shaggy as B.J.’s mustache. But the final seasons are interesting as a model for how TV would find ways to tell stories pitched between comedy and drama.

In the movie-length finale, which aired on Feb. 28, 1983, the laugh track, which had been scaled back over the seasons, was gone entirely. And while the scenario — the war finally ended, after three real-life years and 11 TV seasons — yielded the expected sentimental goodbyes and even a wedding, the core story was as dark as any the series had ever done.

Hawkeye is in a psychiatric hospital after a traumatic experience whose repressed memory his psychiatrist, Maj. Sidney Freedman (Allan Arbus), is trying to tease out of him. Hawkeye recalls a carefree day trip to the beach, a bottle being passed around on the bus ride home. Then the booze becomes a plasma bottle; the bus had taken on a group of civilians and wounded soldiers. One Korean woman holds a chicken, whose noises threaten to expose the stopped bus to a passing enemy patrol. Hawkeye urges her to quiet the bird, and she ends up smothering it.

Finally — as you will never forget if you’ve seen the episode — the memory clears: The “chicken” becomes a baby. “You son of a bitch,” Hawkeye says, “Why did you make me remember that?”

Is it melodramatic? Sure. A downer? Of course. It is also, on rewatching, a striking bit of filmmaking for an ’80s sitcom. Hawkeye’s memory unfolds with the uncanny clarity of a dawning nightmare. No music cues you in to the horror; the images just grow more unsettling and the scene more grim. It is, in a way, like the journey of “M*A*S*H” over the years: A romp in the midst of a war zone goes, bit by bit, deeper into night and the heart of darkness.

And 106 million people came along for the ride. A year and a half later, Ronald Reagan, a Cold Warrior who was elected partly on a backlash to post-Vietnam sentiment, won a second term in a landslide. Yet more Americans than voted in that election tuned in to watch a big old liberal antiwar TV show.

After ‘M*A*S*H’

For most of its 11 seasons, “M*A*S*H” was one of TV’s most popular comedies. But its style went mostly unimitated for decades.

It’s not really until the 2000s that you see its heirs emerge. The British version of “The Office” shares its ability to turn from blistering comedy to seriousness. (Stephen Merchant, a creator, has talked about the influence of watching “M*A*S*H” episodes without laugh tracks in Britain.) The mockumentary format of the American “Office” and other comedies hark back to the news-interview episodes (while Dwight Schrute is a kind of Frank Burns of the paper-business wars).

Cable and streaming especially became fertile ground for finding laughs in grim situations. “Rescue Me” made trauma-based comedy in a post-9/11 firehouse, “Getting On” in a hospital geriatric wing. The Netflix prison series “Orange Is the New Black” was as thoroughly female as “M*A*S*H” was dominantly male, but it brought anarchic ensemble humor to a deadly dangerous setting.

In Hawkeye, meanwhile, you can see a forerunner of the modern-day dramedy antihero, charismatic but damaged and driven by anger. As a kid watching “M*A*S*H” reruns religiously, I loved Hawkeye’s rascally wit, his principles and his pranks. (One of my elementary-school music pageants had us sing the theme song, “Suicide Is Painless.” The ’70s were complicated.)

Rewatching episodes as an adult, I enjoy all that still. But he’s also kind of a jerk! He’s self-righteous, attention-seeking, snide and, if you’re on his bad side, a bit of a bully. In a Season 5 episode, Sidney Freedman diagnosed him succinctly: “Anger turned inward is depression. Anger turned sideways is Hawkeye.”

This describes not a few difficult modern dramedy protagonists, human and otherwise. In one of the best episodes of “BoJack Horseman,” built entirely around the self-destructive equine protagonist’s eulogy at a funeral, you can hear the echo of the episode “Hawkeye,” in which Alda’s character, concussed in a jeep crash, spends nearly the full half-hour monologuing manically at a perplexed Korean family, to stave off unconsciousness.

Making serious comedy is a feat of balance, and some might argue that the legacy of “M*A*S*H” was to give sitcoms license to be self-important, unfunny bummers. In a 2009 episode of the TV-biz sendup “30 Rock” — a proponent of the joke-packed school of entertainment if ever there was one — Alda made a tongue-in-cheek version of that critique himself.

Playing the biological father of the NBC executive Jack Donaghy (Alec Baldwin), he witnesses Tracy Jordan (Tracy Morgan), a performer on the sketch-show-within-a-show, crying over the memory of being too “chicken” to dissect a frog in high school, which he’d covered up with a phony story of having been asked by a drug dealer to stab a snitch named “Baby.”

“A guy crying about a chicken and a baby?” Alda’s character says. “I thought this was a comedy show.”

Of course, if you got the joke, it was precisely because “M*A*S*H” did its job. It proved, memorably, that a great comedy could cut deep and leave scars. A half-century later, “M*A*S*H” has had the last laugh, or lack thereof.

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diary of a Maad Blaque Wombman:

Can you believe, I failed THREE tests this week, and it’s all coming back me… on why I am a Maad Blaque Woman! Here’s a history lesson

Black women were judged by three things which determined there value. Skin complexion, hair texture, and body type.

Lovie & I toured some historical sights down in old Savannah GA which included First African Baptist Church, the first place of worship built by slaves for their own use. The experience was emotional. We saw Hebrew writing etched into the pews (evidence that slaves knew who they were), under ground railroad hide away places, and alters modeled after the Art of the Covenant made of gomer wood, according to Hebraic tradition, etc.

The tour guide told us of the three test black women were given, in the south in order to be sat by most church ushers…according to their value

Test 1: Brown paper bag test- if you are lighter than the paper bag move forward, if you’re dark go to the back

Test 2: the pencil test- a pencil is pushed into your hair. If it falls out, move forward, if it stays put you sit in the back

Test 3: the book test- a book is placed on your middle back. If behind pokes our further than the book, back to the back. If you’re thinner than the book, move forward

In my early years I have struggled with self love and identity issues. I continuously questioned my value and made strides to overcome such insecurities. Little did I know, some of my issues were indoctrinated into the society that I live in… I was never the problem. Praise Yah for the solution!

Yah’s sacred places have been an asylum for his people. A strong congregation can change generations to come. Praise Yah for First African Baptist and the chains they have broken, by being one of the first integrated congregations where blacks and whites sat amongst one another, for one common purpose.

I am blessed to see the tide turning, and the standard of beauty is ever changing and I look forward to what the future holds!

Highlights of the week:

Antoine‘s baptism

My broasted chicken just…. Wow

My ducklings are doing swell

Thought about running: didn’t

Make everyday a pool day in heaven!

I love a good train read… it’s getting juicy

Thank Yah for my sisters who do life with me :)

I went to work (like I was pose to) & got my feet rubbed

Quick Prayer: Most High Yah, I thank you and praise you that I’m one of yours. Allow me to extend grace to others who aren’t like me, and allow me to never become to self important. Touch the women in my life, remind them of who they are and how you see them. Allow us to be a light in a world of darkness. Forgive us of our sins, and allow your praises to be forever on our lips! HalleluYAH and Amen

To my most beautiful reader: you ARE exactly where you’re meant to be. If there is a thorn in your side, remove it. If ever you don’t like what you see in the mirror… get over it :) virtue is an inside job and character measures beauty

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cherry Hill

“Ain't never been a day like it," the old man said, "and ain't never gonna be one."

He sat rocking in a rickety chair while a calm November wind whistled through the chimes that hung above his paint chipped steps. Nearly eighty six, his hair was grayed and thin, and his scalp showed through in frequent, scattered patches. He spoke clearly and thoughtfully, a trait common to the Southern elderly I'd interviewed.

"You sure you want to hear 'bout this? 'Cuz it might take a while. I still get really choked up when I think on it even though it happened sixty some odd years ago."

I nodded. "Take all the time you need, sir."

"Alright..." he said, and shifted in the rocker, bringing it to a stop. The quiet squeaking died, and all was silent save the whistle of the breeze through the wind chimes. "Suppose it's best. This old county's got its ghosts lying around, and this one's probably due for a resurrection."

* * * * * *

William Emmett Johnson was sheriff then...Will, all us deputies called him. He was a real card, not a lick like the old sheriff. Will always used to win the Liar's Club's gold cup every Saturday night. That man could tell the most outrageous, but just barely believable untruths out of the whole Liar's Club. Heck, even at the jailhouse, we weren't ever really sure when he was giving it to us straight or just pulling our legs.

And he had this old confederate shirt he used to wear all the time. He said his grandmother gave it to him, and that it was sent back to her from General Lee with a letter saying how his granddaddy had been killed by a Yankee Negro. I guess because of that, you could say old Will had his teeth sorta set on edge toward colored people. He wasn't mean outright to them, but he sure didn't take a liking to them either. Will, Joseph, and I were the only ones at the jail, usually, so it was just the three of us who were there when it all happened. July twenty third, nineteen hundred and twenty six, I marked that day on a calendar in my head, and I'll never forget it. Jimmie Baker from the drug store came running into the jailhouse, shouting like Gabriel's trumpet was blowing outside and the good Lord was coming back.

"They gonna string him, Will."

"Who they gonna string up, Jimmie?"

"That little Jenkins boy, the youngest one."

"Albert Jenkins..." Joseph always did his thinking out loud. "Why, he ain't never been in no kind of trouble before."

"Well, he's gone and done it now. Lee Dunsten says he's the one what raped his little girl, Winnie."

Will just stared like he always did when he was thinking. "They got any proof, witnesses or personal things found at the site?"

"I don't think so, Will, but I don't think the lack's gonna slow 'em down any."

Joseph and I had already got our gun belts on, and were getting ready to go arrest the Jenkins boy, when Will gave us the call to arms, "Well boys, negro or no, ain't nobody getting lynched in Cherry Hill without Will Johnson looking it over first."

So we all packed into the new car the town had just bought for us, and rode out to the Dunstens' farm.

That Lee Dunsten and his boys done had the Jenkins boy down and bleeding all over God's green earth. They had a rope 'round his neck, and were jerking him here and there like a wild dog on a first leash. Cussing and whipping out his arms and legs, the boy was fighting the rope for all he was worth, but he just wasn't a match for Lee Dunsten mounted on his horse holding the other end. He never could get more than two or three steps before the rope would yank him to the ground and drag him 'round the farm some more. The Dunstens were making darn sure the boy didn't have any fight in him for when they got ready to dangle him in the wind.

Sheriff Will just stepped out of the car, and walked right up to Lee Dunsten's horse. He jerked the reins right out of Lee's hands, and brought the animal to a stop.

"What's going on here, Lee?"

"Now sherf, this here ain't none of the law's business. This boy's the one raped Winnie, and I'm gonna see he pays for it. You boys can get back in your fancy automobile the good people done bought for you, and go back to the jailhouse. There ain't no kinda trouble here for you to pay a mind to."

"Rape's a right strong accusation, Lee. I sure hope you got some proof the boy's guilty."

"Proof! What in Hell! Will? Since when do you need proof to string up a nigger boy?"

"Since we lost the war, Lee." Will was a lawman through and through.

"Well, Sherf Johnson," Lee said to him, "I don't see that it's so all fired important, but if it'll get you off my farm, we found the boy in the back of the house, half in and half out of Winnie's window, just like he hadda do the other night to get to her."

"Now Lee, you know there ain't no love lost 'tween me and colored folks, but laws are laws, and I got to enforce them. If this boy's the one what did that vile sin against the Lord and your girl, he'll pay for it...but through the courts, not s winging from a rafter in your barn."

About then, one of Lee's boys spoke up, "Sheriff Will, I ain't no fancy lawyer or nothing, but laws or no laws, there ain't nobody gonna tell me that courts are for anybody but white folks."

Will just ignored the boy, and walked over to Albert Jenkins. He was scared, that boy, half to death, and shaking like he was freezing in the summer. I guess being on the wrong end of a hanging rope will do it to a fella. Blood was everywhere he wasn't nothing but a dark open sore by this time, a sixteen year old blood and puss sore. His clothes were torn into rags from being drug over the farm, and he might as well have been stark naked for all the covering they gave him.

"Boy."

"Yessir."

"Tell me the truth, boy. What was you doing coming out of Miss Winnie's window like you was?"

"I didn't do nothing to Miss Winnie, sir. She always been good to me, treatin' me nice and all.

"What was you doing coming out of the window, boy?

"I weren't coming out her window, sheriff. I was jes' pokin' my head in to smell the chocolates she's been getting."

Dunsten's oldest boy blurted out then, "You calling me a liar, boy? Sheriff, you ain't gonna take no word of a dark boy over me, are you?"

"Shut up, Lewis," his daddy told him, then back handed him hard across the jaw.

"Will, my boy said he found him coming out Winnie's window, and I believe that's what happened. My boy's word's all the proof I need."

"You ain't the court, Lee."

"You know what the court'll say, Will. There ain't never been a negro jury in this county yet, and ain't no white jury gonna listen to this malarky you've been giving me about laws."

"Maybe so, but you folks pay me to do a job, and by the good Lord, I'm gonna do it the best I can."

Joseph and I got Albert Jenkins, and put him in the car. Will told Dunsten and his boys to get back to the house and stop fooling with the "little nigra boy," and they went, but not without the last word.

"This ain't the end, Will," Dunsten yelled, as he let the screen door slam shut behind him.

You know how some folks just can't leave well enough alone. Well, Lee Dunsten was one of them folks. The whole time we had Albert locked up, Lee and his friends were out raising all kinds of cain 'round and 'round the courthouse and the jail. I still think to this day that old Will put the boy in jail as much to protect him from the Dunstens as for the accusation of rape.

Lee was a deacon down at the Baptist church, but you wouldn't have ever known it by the way he was cussing and carrying on outside. "It's a right fine day for a hanging, sherf," he'd shout 'bout every half hour or so.

Little scrawny Albert was still scared half to death sitting in the cell where we'd put him. So, I'd gone over to help the boy calm down while Will was outside trying to get rid of the Dunstens and their hundred or so friends that had gathered.

"Mr. Deputy, sir."

"Yeah."

"I ain't ready to be no merter yet."

"A merter?"

"Yessir...One of them folks that gets killed for doing nothin' wrong, just mindin' they own business, then right out of the blue somebody wants to kill them for one fool reason or another."

"There's a lot of good company with the martyrs, Albert, but don't you worry none...you ain't gonna die today."

"He's right, that Mr. Dunsten. Ain't no jury gonna believe me over a white boy."

All I could do was nod in agreement with him. Albert Jenkins' eyes were as brown as his skin, maybe browner, and big as baseballs, but when he looked at me full in the face, I saw how pretty they gleamed when they glazed over with the starting of a little tear.

"How come you and the sheriff trying to keep me from 'em, if I'm gonna die anyhow?"

"Boy," I said, "There ain't nobody on God's earth deserves to go out like them Dunstens want to send you."

By now 'bout half the town was outside shouting for the boy to hang. Lee Dunsten had almost started himself an all out riot. Will came back in sometime 'round then wearing a big look of misery.

"Joseph...Get the boy."

"Excuse me, sheriff?"

"Get the boy."

"But they gonna kill him, and he ain't even gone to trial yet."

"I ain't got no time for this, Joseph. Get the boy, now!" Will looked like a man whose whole family had just passed on all at once.

Joseph got up and fetched Albert from the cell, and brought him right up to where Will was.

"Albert, I got something to say to you, and I want you to be a man about it."

"Yessir."

"I don't know if you was the one what raped the girl or no, but out there they say you did. They want you to hang."

"Yessir, I know."

"I tried my best, good Lord have mercy, to keep you safe 'til you could get a trial and a chance."

"Yessir."

"But Heaven above, boy, they just threatened to burn down my jailhouse to get you, even if it means they have to kill me and all my deputies."

Albert didn't say "yessir" then. No, he didn't say nothing. All he did was to spit right in Will Johnson's face. I wanted to spit in Will's face, too.

We tried to talk him out of it, Joseph and I, but in the end, he had his mind all made up. He told us not to get in the way none, else the town would fire us both as deputies.

I ain't never felt so small in all my life, as I did looking on as Albert Jenkins stood there all by himself, 'bout to be strung up an untried man. He didn't cry, but he sure cussed and hollered and kicked and punched and bit when the two oldest Dunsten boys, Lewis and Vincent, came in to fetch him out. They fought with him a good five minutes or so before they could wrestle him to the ground for a chance to tie up his hands and feet. For a scrawny sixteen year old kid, that boy could throw his fist like a trained fighter, and none of us interfered while Lewis and Vincent got a few bruises to carry out with them. But Albert knew he couldn't fight them all day long, and even if he did, there were more than a hundred others waiting outside to come in all at once, so he quit. He just gave up licking them Dunsten boys, and lay there on the floor gawking for breath. Lewis Dunsten came up then and kicked him hard in the stomach. Albert Jenkins coughed and spit blood, then fainted dead away.

The crowd had their fun with the boy, slapping and kicking at him, and taunting with no end of horrible names. I guess they just wanted to make sure he was good and awake before they killed him.

"Devil boy," somebody yelled out, "Black as soot from the Hell pits."

"Ain't never known nothing but stealin' and hurtin' good people."

"Primitive heathens."

Lee Dunsten just took up on that, and sounded like he was making church out of it. "We know, all of us here, that this little Negro had every opportunity to do right." He took care to drag the word Negro out real clear and loud. "He knows what the rules have always been: Don't no black folks associate with no white folks. He was born knowing it, even if we never hadda told 'em. It's inborn, the natural order." People were whooping and hollering like they were at a tent meeting, all stirred up by what Lee was saying. "But now this boy done stepped way over the dividing line. He's gone and done the unthinkable. No self respecting nigger with a brain in his head would force his affection on a tender, young white girl. But let me tell you...this ain't no self respecting boy."

You could have heard that crowd three towns away. Lee's accusation was all the proof they needed that the boy was Winnie's attacker, and they got thirsty for blood. It made you wonder who was really primitive, hearing a whole town yelling out a death chant like they were.

Next thing I knew, they had Albert standing under the oak tree across from the courthouse, and Lewis Dunsten was slipping the rope 'round his neck one more time. It was happening too far away to know for sure, but I swear that the Dunsten boy was grinning from ear to ear as he tightened the rope.

Then, "Crack!" The explosion of gunpowder stood everybody as still as if death had frozen all of them right where they were standing. Sheriff William Emmett Johnson was standing on the front steps of the courthouse with his rifle pointing up at the clouds.

"This ain't court," he shouted to the crowd, "and you ain't the jury what's gonna decide whether or not the boy hangs."

That yelling and screaming lynch mob got quiet right quick, waiting on Lee Dunsten's reaction.

"Sherf, me and all the good folks here aim to see this boy hang, and ain't you or nobody gonna stop us."

"I can't let that happen, Lee."

"Since when have you gone out of your way to protect a..."

Will cut him off with another rifle blast. "Since I believed in the boy's innocence."

"You ain't callin' my boy a liar, are ya, Will?"

"Nope. Just saying he misunderstood the situation as he saw it. It just ain't evidence enough for a hanging."

"We think it is, sherf."

"I'm right sorry to hear that, but I don't reckon it matters much since the police from Pineville are waiting on him to show up at their big, new jailhouse. I just called them, and they said they had plenty of room to hold him 'til his trial."

Lee turned every shade of red in the book, and stormed right up to Will on the front steps. "Will, the boy ain't gonna make it to Pineville..."

"That's obstructing justice, Lee, and that's against the law."

"Fine." He turned and yelled out to Lewis, "Go ahead, boy. This fine lawman of ours wouldn't shoot no white man for giving out justice to a Negro."

Lewis once again tightened the rope, and got ready to dangle Albert. A bullet whizzed by about two feet above his head, and he flinched, but only for a moment.

"You almost scared me, sheriff. I almost thought you were really gunning for me."

He put on a smirk, stepped off of the box, and raised his foot to send Albert swinging out into the air, when the rifle thundered one last time, and Lewis Dunsten fell to the ground like a dove over a hunter's field.

About half the mob screamed while the other half ran off in all different directions. Lee Dunsten didn't do nothing but drop to his knees crying like a newborn. In the confusion, Will picked up the shaken Lee Dunsten, and took him into the jailhouse for being a public nuisance.

Joseph and I made over to where Albert was still standing on the box, terrified. We took the rope off from his neck, and cut it down from the tree as a safeguard. Albert was bleeding pretty bad from the licking he'd taken, and his wrists were cut deep and rubbed raw down to the muscle from the coarse rope. After we cut his wrists loose, and he tried to bring his arms 'round front again, there was a loud scraping noise like bone rubbing bone. The boy was a sore mess with his body covered in blood and bruises and his right arm broken, but he was still breathing, and he wasn't swinging from an oak tree in front of the Cherry Hill Court House.

That, at least, was something.

We carried the poor kid over to the new police car, and then Will Johnson did something I'll never forget. He took off his granddaddy's old confederate shirt, and standing there before God and everybody all bare chested and sweaty, he tore it into three long strips to make a sling for Albert Jenkins' broken right arm. As soon as we'd put him in the car, it wasn't forty seconds before the boy fell straight off to sleep, right peaceful even, all things considered.

Will told us to get in the car, and drive him up to Charleston.

"Charleston, sheriff?"

"Yeah, Charleston. Even if a jury was to find him innocent, folks 'round here wouldn't care a bit. He'd still be in as much danger of hanging as he was before the trial. But in Charleston, he can live...land a job on a ship...sail off a few years. Nobody ever recognizes a man after the sea gets a hold of him. Heck! He don't even have to come back. No, he can make a whole new life. Anything's better than what he'll have waiting here."

"Sheriff, what about them folks up at Pineville? Ain't they gonna be sorely put out when he don't show up?"

"Naw," Will drawled, and started laughing himself sick to tears. "I lied." And he kept on laughing 'til long after we'd headed on up to Charleston.

* * * * * *

"We got Albert a job two days later, broken right arm and all. We waved good bye from the dock as he sailed off to be a cook's assistant aboard Elizabeth's Dream. It was a right odd name for a boat, so we just called it Jenkin's Dream, because of the chance it meant for Albert `cept he wasn't Albert Jenkins no more. Start over, we told him, fresh and clean. And he did. Grover Calvert Williams was the signature he left on the ship's work list.

"He even wrote once or twice, and said he'd married a little French girl, and that they'd moved back to the States...somewhere up North with lots of land and room for a family.

"You know, the Dunstens moved on right after the sheriff let Lee out of Jail. Rumor said they'd moved up to Pineville for a few weeks, then just moved on from there to nobody knows where. Old Will Johnson never got a gold cup for that one, but he sure should've."

I chuckled, and began packing my recorder and notebook away, all the while fighting November's breath as it sought to close the flap of my pack. "Thanks for your time and the story."

"Anytime, anytime at all."

He turned and entered the big screen door going from his porch to the inside of the small house, and I headed for my VW. But before either of us made it to our destinations, he stopped, the door half open, and looked over toward me again.

"Say...Nobody much cares for the old stories anymore. How come you're so interested?"

"Research for my doctorate...race relations in the rural South," I partially lied, and traced the G, C, and W of my grandfather's pocketwatch inside my windbreaker's front pocket.

© Sean Taylor

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

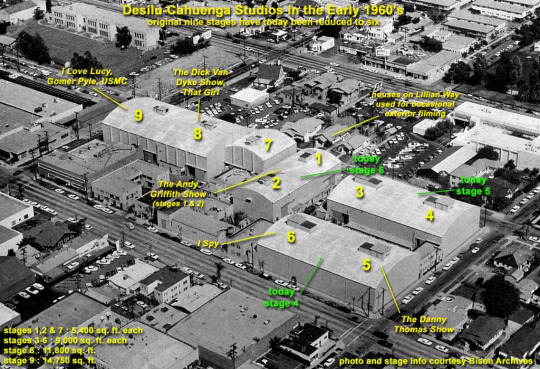

DESILU SOLD!

July 27, 1967

Desilu Productions was formed in 1950 by Lucille Ball and her then-husband, Desi Arnaz. The name was a portmanteau of the couple's first names and was originally applied to the Ball-Arnaz ranch.

Desilu was one of many television production companies that sprung up all over the Hollywood catering to the growing needs of the increasingly popular medium of television. The success of “I Love Lucy” enabled Desilu to expand throughout the 1950s.

When RKO Pictures went bankrupt in 1957, Desilu bought its studios and other location facilities. These acquisitions gave the Ball-Arnaz TV empire a total of 33 sound stages - four more than Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and eleven more than Twentieth Century-Fox had in 1957.

Desilu operated the physical facilities bought from RKO, which included the main Gower Street Studio in Hollywood, next door to Paramount Pictures. It also consisted of a studio in Culver City and the ‘40 Acres’ backlot – most famous for being Mayberry in “The Andy Griffith Show.”

On the lot there was a small theatre called Desilu Playhouse where Lucy hosted the Desilu Workshop, a training ground for new performers.

After the breakup of the Ball-Arnaz marriage in early 1960, Desilu remained successful.

In 1962, Ball bought out Arnaz and became the first female Hollywood mogul ever to run a major motion picture studio, albeit a reluctant one, as Ball never wanted to be a businesswoman. It was shortly after her second marriage to comedian Gary Morton in 1961, that she left the minutiae of the studio's business and financial affairs to her new husband by naming him Co-Chairman of the Board of Directors.

During Ball's time as sole owner, Desilu developed popular series such as “Mission: Impossible” (1966), “Mannix” (1967), “That Girl” (1966), and “Star Trek” (1966).

By April 1964, Desilu found itself in financial trouble – partly due to the fact that husband Morton was inexperienced at running a motion picture studio. “The Lucy Show” was their only remaining self-made production, even though other shows were still produced on the lot as consignments (rentals) from other production companies.

Ball’s success as an actress continued until February 1967, when Ball announced she would sell Desilu to Gulf+Western, a decision which was formalized on July 27, 1967. The act of selling Desilu to Gulf+Western brought the studio under the same parent company as its next-door neighbor Paramount Pictures. The event was commemorated the next day by a dramatic ceremony in which Ball cut a ribbon of film stock which had replaced a wall between the two production studios. Lucille Ball left the Desilu lot the very same day (taking her own hugely popular “The Lucy Show” with her, the only studio asset not included in the sale), directly after the ownership transfer ceremony.

After selling Desilu, rather than working for Paramount, Ball established her own production company, Lucille Ball Productions (LBP) in 1968. The company went to work on her new series “Here's Lucy” that year. The program ran until 1974 and enjoyed several years of ratings success. LBP continues to exist, and its primary purpose is residual sales of license rights for “Here's Lucy.”

Television shows produced by or taped at Desilu

The Jack Benny Program (CBS; 1950-1964/NBC; 1964–1965)

I Love Lucy (CBS; 1951–1957)

Our Miss Brooks (CBS; 1952–1956)

The Danny Thomas Show a.k.a. Make Room for Daddy (ABC; 1953–1957/CBS; 1957–1964)

Private Secretary (CBS; 1953–1957)

December Bride (CBS; 1954–1959)

The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp (ABC; 1955–1961)

Meet McGraw (NBC; 1957–1958)

The Lucy–Desi Comedy Hour (CBS; 1957–1960)

Whirlybirds (Syndicated; 1957–1960)

The Real McCoys (ABC; 1957–1962/CBS; 1962–1963)

The Ann Sothern Show (CBS; 1958–1961)

The Untouchables (ABC; 1959–1963)

The Andy Griffith Show (CBS; 1960–1968)

The Lineup a.k.a. San Francisco Beat (CBS; 1954–1960)

Sheriff of Cochise a.k.a. United States Marshal a.k.a. U.S. Marshal (Syndicated, 1956–1960)

Harrigan and Son (ABC; 1960–1961)

My Three Sons (ABC; 1960–1965/CBS; 1965–1972)

The Dick Van Dyke Show (CBS; 1961–1966)

The Lucy Show (CBS; 1962–1968)

You Don't Say! (NBC; 1963–1969)

My Favorite Martian (CBS; 1963–1965)

The Greatest Show on Earth (TV series) (ABC; 1963–1964)

Gomer Pyle, USMC (CBS; 1964–1969)

I Spy (NBC; 1965–1968)

Hogan's Heroes (CBS; 1965–1971)

Star Trek (NBC; 1966–1969)

Family Affair (CBS; 1966–1971)

That Girl (ABC; 1966–1971)

Mission: Impossible (CBS; 1966–1973)

Mannix (CBS; 1967–1975)

#Desilu#Lucille Ball#Desi Arnaz#RKO#Studios#Paramount Studios#Film#Television#Hollywood#backlot#Gulf + Western#lucille ball productions#The Lucy Show#Here's Lucy#I Love Lucy#Desilu Playhouse#Desilu Workshop#Star Trek#The Andy Griffith Show

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

@yearncryrepeat asked for Josh/Donna, “Would you just stand still?” [Gilmore Girls quote - swap meme]

[In my brain, this is season 4.]

“You’re infuriating,” Donna says, pushing her way into Josh’s apartment.

Josh yawns. It was a rare early night at the White House, and after a long few weeks of running on fumes, he’d fallen asleep on the couch. It felt like he’d barely gotten any rest when he heard a knock at his door. Now he’s standing in his living room in a Mets t-shirt and sweatpants, eyes mostly closed, hoping that if he doesn’t allow them to fully open he can get back to sleep when Donna’s done with whatever the hell she’s doing now.

“Fortune cookie, or horoscope?” he croaks, his voice still sleepy and hoarse.

“What?”

He shuts the door behind her and checks his watch. Apparently he fell asleep on that arm, because the band has pressed red marks into his skin. “It’s almost midnight. You aren’t drunk. So you’re here telling me something now that you can really tell me tomorrow because something has told you to seize a moment, or live, laugh, love, or whatever.”

Donna scrunches up her nose. “I’m perfectly capable of taking charge of my own life without being pushed to action by sayings you can find on a t-shirt at the beach.”

“You go through… phases of things. You latch onto weird stuff.”

“I don’t latch onto weird stuff,” she answers, repeating the latter part of the sentence in a tone that suggests that she doesn’t appreciate the implication.

He sits down on the couch. “Can you get to the monologue listing all the precise reasons I’m infuriating?”

“The flowers.”

“Ah.”

She groans, folding her arms. “That’s all you have to say?”

“I don’t know what else there is to discuss about them. You hate the flowers, then you hate me for a little while. We did the Ricky and Lucy-esque performance at work already,” he says, stretching, having given up on the idea of crawling into bed as soon as she leaves. “We can have our moment of mutual understanding and refreshing candor, then I can go back to sleep.”

“Why do you send me flowers in April? Don’t give me the ‘man of occasion’ line, because you and I both know that’s not the reason.”

“That is the reason,” he insists. “Marking the occasion of your official, permanent return to the campaign.”

“To the campaign, or to you?”

“Can’t have one without the other, can you? Kind of a package deal.”

“Joshua,” Donna says, exasperated. “You’re not understanding.”

Josh raises his eyebrows. “That’s certainly the first thing you’ve said tonight that makes an ounce of sense.”

“You threw snowballs at my window! You told me I looked amazing!”

He sits up straight. “What does that have to do with anything?”

“You threw snowballs at my window, danced with me, and you said I looked amazing.”

“That’s because you did look amazing,” he protests. “Was I not supposed to tell you that? Should I have been a wise-ass instead?”

Donna begins to pace his living room. “See, this is exactly it. You buy me flowers, you flirt with me, you actively look for reasons to be near me, but your default mode of communication is… this?”

She doesn’t sound angry. Her voice is shaky, like she’s been thinking it for years and she can’t hold it in anymore. Finally it hits him. She knows how he feels, and she feels the same way. She loves him. That’s what she’s trying to say.

In a split second, there are forty or fifty reasons flashing through his mind that each indicate why this… whatever it is that they’re thinking about starting... is a bad idea. They’re the same reasons he’s repeated to himself after he catches himself staring at her, or sabotaging a date with yet another gomer, or calling her into his office with a mind-numbing task for her to complete only because he hasn’t seen her face in two hours and he misses her.

But he doesn’t care about any of those reasons at the moment.

“Donna.”

“Do you know how many people have asked me if we’re dating? Do you know how often I have to tell people there’s nothing going on between us, when there is, in fact, something going on between us? What that something is, I have no idea, but… there’s something, Josh!”

Josh stands and walks toward her. “You’re gonna wear a hole in that carpet if you keep pacing.”

“Would you stop with the snark and listen to me?”

“Would you just stand still?”

She does as he asks, and he pulls her close for a kiss. It seems to surprise her at first, but Josh can feel the tension leave her body moments after his lips touch hers.

It feels right, it feels safe, it feels meant to be. It surprises him how natural this seems. He deepens the kiss when she puts her hand in his hair, and suddenly she pulls back, grinning.

“What?”

“Ricky and Lucy? Really?”

“You really want to argue about this now?”

Donna takes his hand. “I suppose not.”

“Next year when you get flowers in April, you can’t get too mad at me.”

“Not if you send them on the right day,” she counters, leaning in closer to his lips in an attempt to kiss him again.

Josh looks at his watch. “It’s 11:56.”

“Your watch sucks. It’s 12:08.”

“I guess we can argue about that next year, then.”

He laughs and jokingly turns on his heel to walk away from her, but she grabs his wrist, smiling.

“Stand still.”

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Pointless Top Ten List (But You’ll Keep Reading, Anyway)

My brother Rikk recently mailed me another top ten list of his, in this instance being his top ten favorite TV comedy shows (which he defines as 30 minutes or less, no movies).

The Three Stooges

M*A*S*H

The Andry Griffith Show

The Beverly Hillbillies

Hogan’s Heroes

I Love Lucy

The Honeymooners

All In The Family

Get Smart

Gilligan’s Island

His honorable mentions include F Troop, The Patty Duke Show, My Three Sons, Gomer Pyle USMC, Batman, Petticoat Junction, Mr. Ed. Bewitched, and I Dream Of Jeanie.

Again, one of those personal favorite lists that you really can’t argue with because it reflects personal tastes and / or fond nostalgia (though I am calling shenanigans on The Three Stooges; they were theatrical shorts shown in movie theaters, not a TV show, and besides, Laurel & Hardy are soooooo much better…).

But of course we’re going to play the game, so I’ll respond, first throwing in a caveat: No skit comedy shows such as Monty Python’s Flying Circus, The Marty Feldman Show, Benny Hill, Second City TV, The Kids In The Hall, or Love, American Style.

I’m also omitting programs like The Gong Show and Jackass because while hilarious and under 30 minutes, they weren’t scripted or story driven.

So here’s my list:

The Dick Van Dyke Show -- the sitcom art form at peak perfection. Carl Reiner’s insight into what writing for a mercurial TV star is like (in his case, Sid Caesar on Your Show Of Shows, for Van Dyke’s Rob Petrie it was Carl Reiner as Alan Brady). If you’ve never seen the show, start off with their two best episodes, “Coast To Coast Big Mouth” and “October Eve” (though they’re all good). “October Eve” is the one where Sally (Rose Marie) finds a nude painting of Laura (Mary Tyler Moore playing Dick Van Dyke’s wife) in an art gallery. SALLY: “There’s a painting here you should know about.” LAURA: “If it’s what I think it is, I can explain.” SALLY: “If you need to explain, it’s what you think it is.”

The Mary Tyler Moore Show – this is the first American novel for television. It’s a novel of character, not plot, and it traces the growth of Mary Richards, a 30 year old woman-child who realizes she needs to grow up, as she blossoms into a mature, self-reliant adult. You can select two episodes at random and by comparing her character growth determine not only which season they were filmed but when in that season.

I Love Lucy -- eking out a bronze medal for its longevity and pioneering of the art form. The first sitcom shot on film, it led the way in the rerun market. Not just a historical icon but consistently funny.

WKRP In Cincinnati -- as crazy as a sitcom could get and still be within the realm of plausibility. Never loved by its network, they bounced it around for four seasons until it faded away (it made a syndicated comeback a decade later, of which we shall not speak). Great supporting staff, dynamite writing. While they never steered away from serious subject matters (such as an actual rock concert tragedy in Cincinnati where several fans were crushed when rushing the stage), they will be forever and justly remembered for the beloved “Turkey Drop” episode.

Fawlty Towers – only two seasons and a mere 12 episodes and yet more comedic bang for the buck than anything else on this list. John Cleese as a frustrated, short-tempered, conniving hotelier practically writes itself. SYBIL FAWLTY: “You know what I’ll do if I find you’ve been gambling again, don’t you, Basil?” BASIL: “You’ll have to sew them back on first, m’dear.”

That Girl -- looking back it can sometimes be hard to judge just how groundbreaking certain shows were. Marlo Thomas as a struggling young actress finding romance and success in Manhattan seems positively wholesome today, but in the mid-1960s it was considered quite daring and progressive. The Mary Tyler Moore Show took their opening credits inspiration from Marlo Thomas’ character exploring Manhattan in the opening credits of That Girl.

He & She -- a one season wonder from 1967. Another daring and progressive show for its era. Richard Benjamin and Paula Prentiss played a young married couple, he being a cartoonist who drew a superhero strip (the actor playing the superhero on TV in the series was Jack Cassidy at his manic best). Another show with a dynamite supporting cast…and just too hip for the room at the time (honorable mention to Love On A Rooftop, a similar show from the previous season that also proved too advanced for audiences at that time).

Green Acres -- started out silly but quickly took a turn into the surreal, breaking the fourth wall, commenting on the opening credits as they ran by, all sorts of oddball stuff. Dismissed as a hayseed comedy, the truth is the supporting cast possessed dynamite comedic chops and their sense of timing is a joy to behold. Forms a loose trilogy with The Beverly Hillbillies and Petticoat Junction since all three referenced the same small towns of Hooterville and Pixley as well as occasional crossovers (honorable mention to the first season of Petticoat Junction which is as pure an example of Americana as one could hope to find and could easily be distilled into a feature film remake).

The Young Ones -- another two season / twelve episode wonder from the UK. Four stereotypical English college students go through increasing levels of insanity as the series progressed. Unlike most shows of the era where there was no continuity episode to episode, damage done in an early episode would still be seen for the rest of the series. (They also would simply end a show when they ran out of time, not resolving that episode’s plot.) Their random / non sequitur style proved a tremendous influence on shows like Family Guy.

Fernwood 2 Nite / America 2-Nite -- a spin off from the faux soap opera Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, this presented itself as a cable access variety show for Mary Hartman’s hometown of Fernwood. With Martin Mull as the obnoxious host, Fred Willard as his incurably dense second banana, and TV theme song composer Frank De Vol as the band leader. Because it’s so rooted in 1970s pop culture it doesn’t age as well as some other shows on the list, but many of the gags still land solidly today. For the second season the show-within-a-show went nationwide and became America 2-Nite. Very funny, very well written, and all the more remarkable because these guys were doing five episodes a week!

Okay, so what can this list tell us?

Buzz is old. Like really, really, really old.

Buzz stopped watching sitcoms in the mid-1980s.

There’s a reason for that. By that time I was writing for TV and trying to get my own work done. I didn’t have time to sit and watch TV on a regular basis (still don’t), and too often I could see the gears turning and guess where the episode was heading by the end of the first scene (still do).

I’ve veered away from “must watch” TV, especially shows that require the audience to keep track of what’s gone on before.

Tell me I have to see the first six seasons of a show to appreciate what happens in the seventh and you’ve just lost me as a potential viewer. I’m strictly a one & done kinda guy now (though I will binge watch if a mini-series has a manageable number of episodes, say six).

My list represents a time capsule for what caught my interest and attention during a very formative period of my life, i.e., from the early 1960s as I became more and more aware that writing was where my future lay, to the mid-1980s when I hit a good peak stretch.

I don’t doubt there are great and wonderful hilarious comedies out there that I haven’t seen, I’m just listing what I have seen that did make an impression on me.

Your mileage may vary.*

© Buzz Dixon

* It should vary! Be your own person!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Green Family Meta // Revised

chun-hwa “katherine” paik was eighteen years old when she was sent to the chinese space station, shenzhen. eldest daughter of one of the most influential families in all of south korea, the welcome and hospitality she received was supposed to be nothing more than a diplomatic show of peace despite the once tense political/economic relationship between south korea and china. about a week into her time on the station, however , katherine began to feel ill and after a quick visit to the station’s hospital , she found out she was pregnant. as the representative of a major power, she didn’t want to reveal this information and quickly planned for her return to earth. due to the nature of space stations , it would take a week before the accommodations could be made , but katherine didn’t mind. the day before she was scheduled to leave, however, disaster struck: nuclear fallout– everyone’s worst fear. young, pregnant, and stranded in a space station that was not her own, katherine melted into the shadows. her entire family all dead– or presumed so.

that same year, she gave birth to a healthy boy: jin paik. the boy was raised in a time of chaos– everything was being figured out. what was legal one day was lethal the next. the environment in the shenzhen was especially tense. even though they’d agreed to be part of unity day , the ark wanted to assimilate all the ships under one culture -- going as far as to rename the station arrow. there was major pushback by people who didn’t want their culture , their history erased for the sake of ... what ? protests were common place , representatives traveling to and from stations to negotiate. but the longer it went on , the more the forced assimilation became the law of the ark. while jin grew up in the thick of this climate, he and his mother had very little to do with it. never re-marrying, katherine raised her son as best she could– teaching him all she remembered about home. not arrow, but south korea: the language, the culture, the food. it became like a fairytale to him, sitting on his mother’s lap as she recited words no one else on arrow understood, besides the handful of others who had been sent with katherine all that time ago.

while it took Jin a very long time to settle down, he eventually married a younger woman: lydia. lydia’s father had been one of the guards stationed with katherine , though when that job became obsolete , he branched off from shenzhen to the american station. there he met a korean-american woman who would eventually become lydia’s mother. jin and lydia had a happy marriage, though jin’s loyalties to arrow station and his mother often conflicted with lydia’s belief in the uniting of the stations and creation of the ark. it was ten years before they had a child– unsure of when they wanted to really start a family, knowing that the child they had would be their only. hannah paik was born forty-five years after the destruction of Earth. while her father tried his best to impart his knowledge of korea and korean culture onto her , hannah was part of a generation that would only know the ark. other languages were phasing out , the luxuries that came with accommodating for other cultural rights were wearing thin– resources they couldn’t afford to ‘waste’ in the preservation of more than just the human race.

although hannah was raised in agro ( where her mother was from ) , she would often go with her father to visit her grandmother in arrow. arrow was still in a state of rebellion, defiance of cultural assimilation everywhere and without strict enforcement , that wasn’t looking to change any time soon. this all went over hannah’s head however. the loyalty jin had towards the station he was born in and culture he was raised in was still a major source of tension between her parents , though. often her father would leave for a day or two after arguing with her mother , spending that time with katherine in arrow. it was during one of those days when the ark’s first culling took place. although poised as a ‘ventilation accident’ , everyone knew better. it was a warning. arrow’s rebellion stopped after the deaths of a hundred and twelve residents. among the dead were hannah’s father and grandmother. the girl was five years old.

hannah paik was a wild child. the strict laws that turned to stone during her early years ( all crimes are punishable by death wasn’t instated until Hannah was six ) only added to her ( and her generation’s ) need to rebel. smart and resourceful , hannah often found ways around things , tiptoeing past the line of legality. her mother tried to reign her in , but there was a will and determination within the girl that couldn’t be suppressed– even though hannah loved and respected her mother immensely. as she got older , she began to harbor a reputation , though whether it was good or bad was all subjective. flirty and ferocious , hannah had a long list of lovers. none of them held her interest for long , but none of them were supposed to. it was all fun and games. until it wasn’t. one day , hannah’s reputation caught up to her. it was then , at her lowest , that she met daniel green. or rather , met him again. like her grandmother , his grandmother had been on the same diplomatic mission from south korea. also like hannah’s grandmother , his had died in the culling. although the two had met before as small children , it wasn’t until then , in their mid-teens that they found each other again. and this time , the two fell madly in love. from that day on , hannah only had eyes for him. she knew she would never love anyone this much.

however , she was still hannah , and her habit of gravitating towards trouble didn’t end entirely when she fell in love. in fact , six months before her eighteenth birthday , hannah was thrown in sky box for illegally holding a party in alpha station. for the next couple of months , no one knew whether or not her crime was enough to get her floated: as innocent as it was , it took a lot for the council to deem a crime unworthy of being floated for after the teenager turned eighteen– especially if their arrest date was within that last year. terrified and alone , hannah vowed that if she got out , she’d dedicate her life to doing good and ( mostly ) following the law. two days before her birthday , a guard came to her cell and informed her that the decision had been made. she was free to go.

soon after leaving sky box , hannah and daniel got married. however , hannah refused to even think about starting a family until she knew what she was going to do the rest of her life. together , mr. & mrs. Ggreen worked their asses off in agro , revolutionizing the way pharmaceuticals were produced and distributed within the ark. even working hard and stressful days , they rarely fought and everyone who knew them , counted the greens among the the happiest couples around. with the pharmaceutical distribution up and running , it was finally time add another member to the family.

And thus, montgomery green was born. and the rest is history.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Snow White and the 1026 Dwarfs

Snow White woke up in the strangest little bed!

She'd happened upon the small, cozy house deep in the woods, found nobody at home, and promptly crashed in the first bed she'd spotted. Sleep claimed her then, dragging her away to a place of relative peace and calm... carefully letting her ignore how tiny all the furnishings were, how oddly low were the ceilings and fixtures.

And now, the next morning! What odd little men surrounded her! Normally she'd be alarmed by close proximity to so many strangers, but the events of the past day had granted her an oddly calm outlook on life. Nothing much rattled her anymore.

Snow White blinked sleepily, yawned, and stretched. The men watched her every movement, transfixed.

"Do you talk?" She asked experimentally.

One older man -- tiny, rotund, and wiser than the rest with a long white beard -- glanced around at the others and nodded. He adjusted his spectacles and stepped forward.

"I'm Doc," he explained with a jolly chuckle. "And these are my friends: Smarmy, Ragey, Explainy, Glossy, Pookie, Pesty, Grippy, Inebriated, Teary, Swampy, Piggy, Catty, Hitler, Stroky, Zombie, Mooky, Tandy, Fakey, Twinky, Biggie, Munchy, Stingy, Intrepid, Gabby, Shitsnacks, Packy, Growly, Sleazy, Pervy, Ookey, Maggy, Slither, Effy, Jelly, Freezy, Snuggy, Dippy, Toothy, Banger, Loathsome, Smelly, Loofa, Eerie, Jenny, Zoidberg, Fatty, Porkey, Cutty, Brazen, Krabby, Outlandish, Irony, Queasey, Juicy, Ugly, Wonky, Appealing, Lectory, Terminator, Off-putting, Shorty, Irregular, Hissy, Silky, Hardy, Whacker, Ginny, Pammy, Lovely, Chasey, Numby, Abba, Unmentionable, Phreaky, Gawkey, Spooly, Dairy, Flamy, Pickley, Jammy, Croaky, Diehardy, Sordid, Boasty, Rumbly, Klepto, Siggy, Serendipity, Touchy, Thrifty, Cassy, Noxy, Woggly, Gaggy, Beauty, Bluto, Easty, Larky, Sleepy, Hottie, Cloggy, Muffy, Busty, Flouncy, Oly, Wordy, Floopy, Bently, Winky, Rampy, Twitty, Rutty, Witchy, Boxey, Sexy, Sicky, Blazey, Googly, Chemistry, Humpy, Bloggy, Palsey, Tranny, Nipply, Creepy, Jumpy, Weekly, Dready, Burny, Stjnky, Potty, Poofey, Affable, Sippy, Yeachy, Volatile, Jacky, Pokey, Tumbly, Stinky, Hippie, Restless, Frosty, Slicey, Grabby, Bashful, Milky, Lenny, Slick, Losty, Dramatic, Subliminal, Peeny, Inserty, Botfly, Whipser, Edgy, Strutty, Gamey, Goaty, Slammy, Hickey, Murdery, Lickey, Quiet, Bastard, Sprainy, Griefy, Freeky, Snicky, Snobby, Destructive, Pagey, Hefty, Freepy, Dreamy, Tinny, Jaunty, Larpy, Yelpy, Pumpy, Techey, Wackey, Krappy, Porky, Banny, Lawdy, Spikey, Noxious, Robby, Forky, Woeful, Cringley, Roasty, Grumpy, Queefy, Slabby, Qwerty, Oaky, Rusty, Donner, Bitey, Ernie, Bratty, Reddy, Alky, Pearly, Tooky, Clingy, Rapey, Contagious, Wheezy, Toasty, Nosy, Hungry, Cupid, Woofy, Wicked, Kitty, Slappy, Silly, Oogly, Quagmire, Chumpy, Spocky, Secretive, Yukku, Checky, Goofy, Porney, Seepy, Angry, Junkie, Dumpy, Cagey, Handy, Ghastly, Bunny, Narky, Crummy, Tipsey, Wizzy, Peachy, Splashy, Frighty, Towley, Rangey, Twitchy, Birdy, Blotty, Wheely, Tweety, Mealy, Tazey, Boozy, Mopey, Icky, Hacky, Mental, Pasty, Guffy, Yelly, Picky, Lucy, Bloody, Doomy, Balky, Sharky, Moby, Tastey, Clunky, Happy, Nancy, Fry, Puke, Zany, Sweaty, Pimply, Poppy, Testy, Classy, Scratchy, Righty, Smegma, Pissy, Schmutzy, Proxy, Preachy, Prey, Baddy, Westy, Clumsey, Jumbo, Pawy, Jaundiced, Masturbatey, Spasms, Wiley, Pukey, Havok, Puffy, Startled, Prissy, Snoopy, Ruffian, Iggy, Acid-Refluxy, Nifty, Dressy, Gomer, Flabby, Deadly, Smalls, Neurotic, Hideous, Shecky, Blondy, Skunky, Yummy, Victor, Jewy, Arny, Neuty, Biff, Toady, Humpty, Moogly, Grassy, Corny, Feisty, Angsty, Creamy, Techy, Lopsey, Queeny, Stretchy, Mo, Spanks, Regretful, Snarfly, Underpants, Ready, Lanky, Splenda, Naggy, Faily, Yakky, Sizzly, Jokey, Pacey, Spooey, Traumatic, Screamy, Tucker, Pimpy, Beady, Roughy, Snoozy, Roofy, Quimbly, Brewy, Gumby, Pointy, Hooky, Writey, Shimmy, Bulgy, Nootsy, Bingey, Mooby, Dunky, Sully, Neurtsy, Woey, Jiggy, Prietsly, Terry, Forgetful, Comfy, Romney, Campy, Northy, Giggidy, Dipsy, Beefy, Poledancey, Apocalypse, Woozy, Evil, Talky, Vapid, Freaky, Whackey, Inserto, Bleaty, Chufty, Scuzzy, Crispy, Tepid, Snazzy, Sqealy, Grotty, Jimmy, Nanny, Godlike, Furious, Booty, Wolfy, Cumpy, Toily, Crumbly, Biggo, Boggly, Ironic, Belchy, Flaily, Killy, Puggy, Wendy, Gloomy, Verbosity, Listless, Twisty, Waffles, Archy, Wheatley, Iconic, Klassy, Pauley, Bruiser, Prefunctory, Ruffy, Poopy, Zuckerman, Snappy, Oily, Shakes, Yiles, Priggy, Airy, Godly, Hotty, Lassy, Fudgy, Wooky, Bursty, Leggy, Soggy, Soulful, Walky, Unkillable, Bindlestiff, Pathy, Soothy, Lolzy, Spiffy, Trekky, Toothsome, Goldy, Daffy, Yucky, Pappy, Snowy, Dancy, Sappy, Lana, Cursey, Drippy, Cackles, Fuzzy, Malignant, Ghosty, Quality, Hurty, Schulty, Fizzy, Toughy, Tweaky, Starry, Jigsaw, Piney, Magnanimous, Softy, Denty, Damned, Intolerable, Dodgey, Spazzy, Ropey, Socky, Moomoo, Sammy, Dampy, Cracky, Zippy, Whorey, Likey, Wooy, Spewy, Farty, Perthy, Kinky, Peely, Wetone, Squeaky, Frenzy, Noisy, Danny, Flippy, Fartsy, Gravy, Barfy, Loopy, Regular, Nedly, Quacky, Sloppy, Snooki, Crampy, Wetty, Appealy, Boofy, Snotty, Kwazy, Nutty, Regal, Zappy, Candy, Scary, Shakey, Yeasty, Trampy, Runty, Turgid, Icey, Dusty, Adolph, Pocky, Shitty, Nasty, Cranny, Mommy, Monkey, Prickley, Lumpy, Snippy, Quaffy, Wendigo, Opulent, Henny, Prancer, Pervo, Pippy, Rotund, Cavey, Dazzle, Clooney, Rumpy, Pudgy, Spunky, Ralfy, Questy, Dwarfy, Limpy, Rugby, Junky, Insideous, Assy, Hizzy, Hotsy, Honey, Punky, Blingy, Spinny, Nicky, Spindly, Lacey, Banshee, Feely, Baldy, Rabbity, Lunky, Swarley, Damply, Whiley, Splattery, Squirty, Alcoholic, Foggy, Denny, Berty, Zinny, Mammy, Delicious, Dropsey, Vixen, Beary, Beatlejuice, Knobby, Loudly, Meaty, Teethy, Drinky, Woz, Wanky, Scuffy, Swimmy, Gummy, Posse, Milly, Wallop, Pouty, Ruby, Chicken, Poofy, Funny, Smugly, Spinry, Grimey, Ripley, Savory, Schmuckey, Stainy, Quivery, Pooly, Droopy, Lappy, Herpy, Able, Goosey, Dapper, Beasty, Dazy, Giggy, Drowsy, Lowly, Coolie, Slutty, Burby, Nippy, Firey, Sniffy, Glassy, Factory, Cheney, Slidey, Chippy, Kludgy, Orly, Meany, Kreepy, Pooley, Ninja, Whizzy, Victim, Iffy, Saggy, Kenny, Floppy, Nabby, Sickley, Groggy, Liquidity, Hussy, Jinxy, Kewpie, Lampy, Saxy, Dexter, Doleful, Dandy, Peggy, Mooey, Slashy, Drunkey, Homo, Rolly, Hoggly, Healy, Salty, Gropey, Ghouley, Whirley, Faggy, Weedy, Teaser, Dasher, Ego, Artsy, Quippy, Insanity, Beastly, Chappy, Sparky, Zesty, Tasty, Bumpy, Tappy, Uggy, Herky, Greasy, Weakly, Grungy, Jeery, Menthol, Ouchy, Trollface, Morty, Pandy, Scooby, Miley, Racky, Upchuck, Stumpy, Spongy, Slurpy, Kiley, Tummy, Incindiary, Tokey, Flighty, Pussy, Porker, Pranky, Itchy, Spongey, Fuckey, Stuffy, Quiver, Dreary, Ravey, Dirtzy, Tanky, Crabby, Besty, Dregs, Killzy, Wackry, Daisy, Killer, Chevy, Tacky, Stimpy, Tiny, Buffy, Piggie, Crufty, Stabby, Oozey, Unlucky, Beatnik, Twitly, Kingly, Aery, Ogly, Gimpy, Shanky, Trippy, Fingery, Trumpy, Quackey, Cringey, Hokey, Emergency, Flowery, Tinky, Wifey, Crowley, Gassy, Gingery, Bobby, Tender, Penny, Nutso, Mighty, Crazy, Klinky, Blitzen, Clappy, Slitty, Leaky, Queasy, Wallaby, Buddy, Bootlicker, Peeky, Sadistic, Lovey, Glowy, Pickles, Gingerly, Misty, Lofty, Mickey, Wrappy, Ridiculous, Perky, Tangly, Sprockets, Lackey, Awful, Crassy, Runny, Nasal, Frigid, Doggy, Leafy, Planty, Stealthy, Soapy, Draggy, Queery, Texty, Undie, Davey, Fucky, Futurey, Lefty, Sickly, Diseased, Cranky, Nukey, Gangly, Totty, Dummy, Flakey, Lizzy, Tighty, Froggy, Gunny, Doily, Blotto, Seizey, Lazy, Venty, Blacky, Sandy, Immotral, Spangly, Clowny, Falsey, Loosey, Hanky, Wavy, Shifty, Annoying, Navy, Broody, Cunty, Impressy, Tuffy, Anonymous, Dickey, Pugly, Trolly, Kissy, Reflexy, Prawny, Obnoxious, Duffy, Kingy, Clicky, Nosey, Weepy, Phony, Frenny, Blinky, Neutral, Icony, Southy, Jetty, Teeny, Brutus, Wiffy, Smuggy, Busy, Plucky, Fisty, Spotty, Smokey, Chokey, Lippy, Tammy, Baggy, Powerless, Whitey, Typo, Mimsey, Tiki, Slurpee, Tearful, Flamey, Boozey, Moochy, Jewlery, Wobbly, Bossy, Randy, Curmudgeon, Grampy, Treacherous, Tonedeaf, Handsy, Speedy, Lulzy, Marty, Smacky, Rooky, Frightened, Piggly, Artful, Plowy, Bitchy, Barky, Preppy, Sunny, Rocky, Whappy, Hiney, Spanky, Whammy, Deafy, Mathy, Brainy, Fishy, Barfly, Swifty, Clueless, Dizzy, Lordy, Swindly, Pony, Snooty, Twix, Banksy, Wisty, Squirmy, Brewery, Scrappy, Slippy, Trollop, Ballsy, Willy, Rappy, Sneezy, Addy, Icy, Earny, Fidgety, Schooly, Klangy, Wistful, Metal, Lucky, Obsessive, Henzy, Huggy, Sassy, Agey, Pinky, Horny, Benny, Passy, Tingly, Rippy, Reagal, Freebie, Tossy, Slippery, Touchey, Kermy, Wiggly, Druggy, Hippy, Sweety, Dougie, Crappy, Peaty, Nazi, Faulty, Swirley, Crunchy, Bully, Flambe, Biddy, Hoppy, Bangy, Punny, Unsavory, Derpy, Jizzy, Ratty, Unlikable, Gently, Droppy, Ren, Smithy, Knotty, Deady, Chicky, Jerky, Flatulent, Billy, Pithy, Humphrey, Hansel, Poopie, Snuggly, Loki, Dopey, Yippy, Ridonkulous, Cody, Blatty, Renny, Parky, Prancy, Banananery, Yukky, Cheaty, Lossy, Scruffy, Silty, and Drifty."

Snow White laughed and clapped her hands with delight. "My, there certainly are a lot of you! I'm ever so sorry for barging in here uninvited, but I don't really have a home any more... would you mind terribly if I stayed for awhile? I can cook and clean and--"

Doc raised a hand, interrupting her gently. "We'd be honored if you stayed!"

All 1026 dwarfs nodded in agreement, and were so thrilled they threw Snow White a party to celebrate their new friendship. The party lasted late into the evening, and everyone passed out with full tummies and a happy smile lighting their faces.

The next day the dwarfs arose early and prepared for work. Snow White cooked them breakfast and when it was time to leave they all lined up at the door to bid her farewell for the day.