#House of Capet

Photo

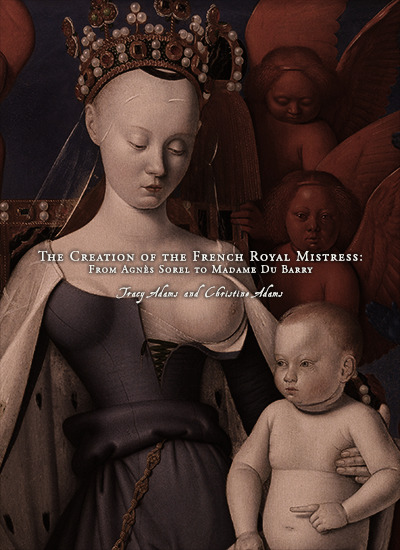

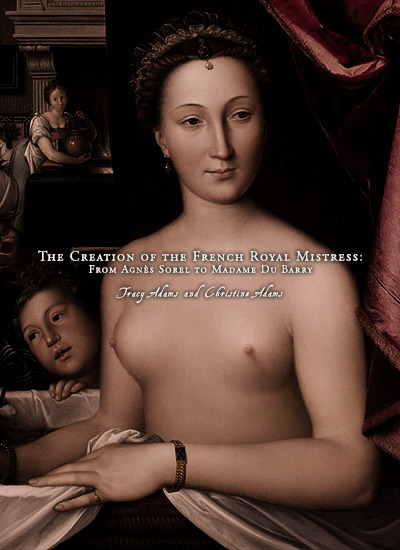

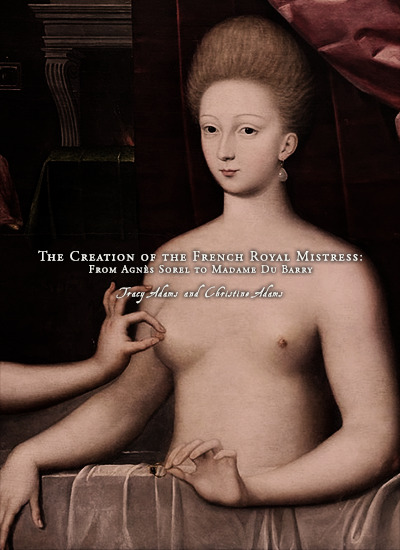

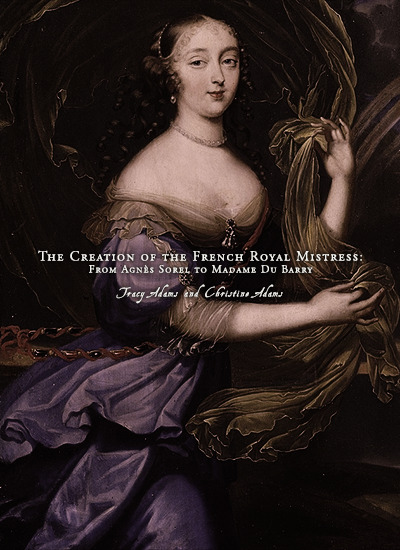

Favorite History Books || The Creation of the French Royal Mistress: From Agnès Sorel to Madame Du Barry by Tracy Adams and Christine Adams ★★★★☆

This study explores the sociogenesis and development of the position in France, examining the careers of nine of its most significant holders: Agnès Sorel, Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, Diane de Poitiers, Gabrielle d’Estrées, Françoise Louise de La Baume Le Blanc, Françoise Athénaïs de Rochechouart de Mortemart, Françoise d’Aubigné, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, and Jeanne Bécu. Although kings had always had extraconjugal sexual partners—some of them powerful, such as Alice Perrers or Jane Shore—only in France did the royal mistress become a tradition, a quasi-institutionalized political position, generally accepted if always vaguely scandalous. And yet the position has been studied only in popular narrative histories intended to titillate. Other powerful female roles central to royal family life, such as the queen, the queen’s entourage, and the female regent, an unofficial role once considered somewhat illegitimate, have received serious attention in recent years, as have individual mistresses. However, the important and enduring position of French royal mistress per se has not been explored.

The study’s point of departure is a simple question: What was it about France? We would like to be very specific about our approach to this question. The creation of the role could be examined from any number of valid and enlightening perspectives. For example, it could be approached through a psychoanalytic lens, to hypothesize about the hidden emotional reasons why the role emerged when it did. Or it could be examined within the context of the Querelle des femmes, that long-term debate over the merits and faults of women, which corresponds, chronologically, to the appearance of the powerful royal mistress in France. However, given our own critical inclinations, we have opted to examine the intellectual, emotional, and physical environment that made emergence of the role possible.

We take as the basis of our analysis Fernand Braudel’s three-part schema of history, which differentiates long- from medium-term structures and both of these from short-term events, and, in this introduction, we initiate the study by applying the schema to the period between 1450 and 1540. Agnès Sorel, often considered to be the first significant French royal mistress, died in 1450; around 1540 Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, the Duchess of Étampes (1508–1580), begins to appear in ambassador reports as a central figure in court politics. As we will see in chapter 1, although indirect evidence attests to Agnès’ political influence, it was not widely recognized during her own time. In contrast, no one doubted Anne de Pisseleu’s power. Between these two dates, then, something occurs that makes it possible for the king’s mistress to be taken seriously as a political adviser.

#historyedit#house of valois#house of capet#french history#european history#women's history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Iron King by @sekihamsterdiestwice

A fan art of young Philip IV“the fair”,want to show his solitude,piety and grimness

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

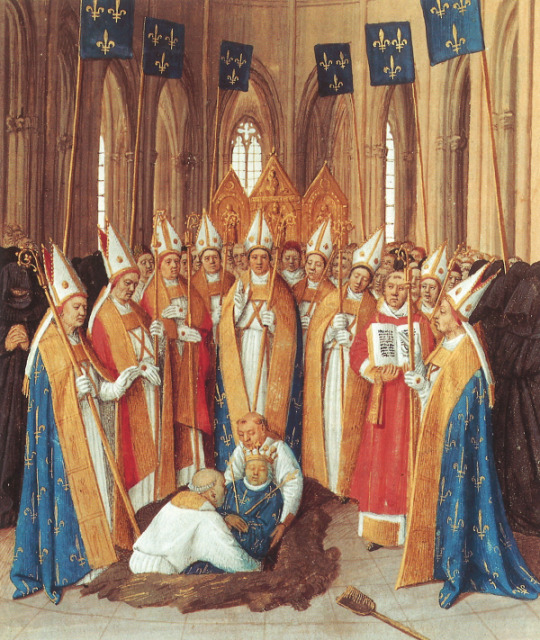

Detail showing the coronation of Queen Jeanne, from the Coronation Book of Charles V, France (Paris), 1365, Cotton Tiberius B. VIII, f. 68r.

#maison capét#house of capet#capet dynasty#reine de france#queen of france#charles v#consort#medieval France#manuscripts#royalty#french royalty#queen joan of france

0 notes

Photo

Margaret I (1310 – 9 May 1382) was a Capetian princess who ruled as Countess of Burgundy and Artois from 1361 until her death. She was also countess of Flanders, Nevers and Rethel by marriage to Louis I of Flanders, and regent of Flanders during the minority of her son, Louis II, in 1346.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The House of Capet.

987-1328

The Capetian dinasty was the first French dinasty resulting after the death of Louis V (c.967-987) last Frankish king of the Carolingian Empire. In my HC, this Frankish personification is father of both France and HRE, and also Austria. After the colapse of the Carolingian empire, the Kingdom of Francia disappeared and the empire was partitioned in three big territories; West Francia (France), East Francia (HRE) and Middle Francia (the territories that the both of them will be fighting for in the centuries to come, the Benelux spawned from those territorial wars in between them, as well and Switzerland and everything in between).

France and the Holy Roman Empire would become natural enemies, then, as Franco's inheritance would be the same as that of the Carolingian Empire; to become the next Roman Empire. And both kingdoms would spend the rest of the centuries until the World Wars trying to achieve that inherited goal. It has a name, in fact; Franco-German enmity.

Hence, then, the name Holy Roman Empire, from the intentions to become the next great empire uniting the three continents. France is the older son, by the way. The Frank had... a little favoritism towards the youngest, because it was identical to him. And more visibly German, of course. This fueled the competition between the two and the hereditary and historic animosity between the two "princes".

It was the Franks that started the monarchical rule, feudalism and the hereditary rule for the sons in Europe. So France, HRE and Austria would be the first princes, haha.

#hetalia#aph fanart#aph france#francis bonnefoy#hws france#historical hetalia#myart#As always this are my HCs based on historical events#no one has to agree with them or anything

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self-Portrait – Joachim Wtewael // Self-Portrait – George Frederic Watts // Self-Portrait – Hans Baldung Grien // Self-Portrait – François Grenier de Saint-Martin // Self-Portrait - Anthony Van Dyck // Self-Portrait with Lace Jabot – Maurice Quentin de La Tour // Self-Portrait – Pierre-Auguste Renoir // House on the Shore – Pierre-Auguste Renoir // Self-Portrait – Amanda Sidvall // Self-Portrait – Marie-Gabrielle Capet // Self-Portrait with Palette – Alice Pike Barney // Self-Portrait – Angelica Kauffmann // Self-Portrait with Apron and Brushes – Anna Bilińska-Bohdanowicz // Self-Portrait – Theresa Concordia Mengs // Self-Portrait at an Easel – Sofonisba Anguissola // Alice Roosevelt Longworth – Alice Pike Barney

#amanda sidvall#marie gabrielle capet#alice pike barney#angelica kauffmann#anna bilińska bohdanowicz#theresa concordia mengs#sofonisba anguissola#you're just a boy (and i'm kinda the man)#yjabaiktm#the good witch#the good witch maisie peters#maisie peters the good witch#maisie peters#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of French Princesses at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

This list is composed of princesses of France until the end of the House of Bourbon; it does not include Bourbon claimants or descendants after 1792.

The average age at first marriage among these women was 15.

Judith of Flanders, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 12 when she married Æthelwulf, King of Wessex in 856 CE

Rothilde, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 19 when she married Roger, Count of Maine in 890 CE

Emma of France, daughter of Robert I: age 27 when she married Rudolph of France in 921 CE

Matilda of France, daughter of Louis IV: age 21 when she married Conrad I of Burgundy in 964 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Reginar IV of Hainault in 996 CE

Gisela of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Hugh of Ponthieu in 994 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Robert II: age 13 when she married Renauld I, Count of Nevers in 1016 CE

Adela of France, daughter of Robert II: age 18 when she married Richard III of Normandy in 1027 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Philip I: age 16 when she married Hugh I, Count of Troyes in 1094 CE

Cecile of France, daughter of Philip I: age 9 when she married Tancred, Prince of Galilee in 1106 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Louis VI: age 14 when she married Eustace IV, Count of Boulogne in 1140 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry I, Count of Champagne, in 1159 CE

Alice of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Theobald V, Count of Blois in 1164 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry the Young King in 1172 CE

Alys of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 35 when she married William IV of Ponthieu in 1195 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 8 when she married Alexios II Komnenos in 1180 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Philip II: age 13 when she married Philip I of Namur in 1211 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 14 when she married Theobald II of Navarre in 1255 CE

Blanche of France. daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married Ferdinand de la Cerda in 1269 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married John I, Duke of Brabant in 1270 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 19 when she married Robert II, Duke of Burgundy in 1279 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Philip III: age 22 when she married Rudolf III of Austria in 1300 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Philip III: age 20 when she married Edward I of England in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip IV: age 13 when she married Edward II of England in 1308 CE

Joan II of Navarre, daughter of Louis X: age 6 when she married Philip III of Navarre in 1318 CE

Joan III, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Odo IV, Duke of Burgundy in 1318 CE

Margaret I, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Louis I of Flanders in 1320 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip V: age 11 when she married Guigues VIII of Viennois in 1323 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Charles IV: age 17 when she married Philip, Duke of Orleans in 1345 CE

Joan of Valois, daughter of John II: age 9 when she married Charles II of Navarre in 1352 CE

Marie of France, daughter of John II: age 20 when she married Robert I, Duke of Bar in 1364 CE

Isabella, daughter of John II: age 12 when she married Gian Geleazzo Visconti in 1360 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles V: age 8 when she married John of Berry, Count of Montpensier in 1386 CE

Isabella of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 6 when she married Richard II of England in 1396 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VI: age 5 when she married John V, Duke of Brittany in 1396 CE

Michelle of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 14 when she married Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1409 CE

Catherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 19 when she married Henry V of England in 1420 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married Charles I, Duke of Burgundy in 1440 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married John II , Duke of Bourbon in 1447 CE

Yolande of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Amadeus IX, Duke of Savoy in 1452 CE

Magdalena of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Gaston, Prince of Viana in 1461 CE

Anne of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Peter of Bourbon in 1473 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Louis XII in 1476 CE

Claude of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 15 when she married Francis I in 1514 CE

Renée of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 18 when she married Ercole II d'Este in 1528 CE

Madeleine of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 17 when she married James V of Scotland in 1537 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 36 when she married Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy in 1559 CE

Elisabeth of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 13 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1559 CE

Claude of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married Charles III, Duke of Lorraine in 1559 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 19 when she married Henry IV in 1572 CE

Elisabeth of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Philip IV of Spain in 1615 CE

Christine of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy in 1619 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 16 when she married Charles I of England in 1625 CE

Louise Élisabeth of France, daughter of Louis XV: age 12 when she married Philip, Duke of Parma in 1739 CE

Marie-Thérèse, daughter of Louis XVI: age 21 when she married Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême in 1799 CE

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the same vein as the “whole world is a garden” line that constantly gets treated as an actual quote from the text of The Secret Garden even though it’s from the 1993 film, there’s another quote that gets misattributed to Frances Hodgson Burnett.

“I am a princess. [...] All girls are! Even if they live in tiny old attics, even if they dress in rags, even if they aren’t pretty or smart or young, they’re still princesses, all of us!”

This is not from Burnett’s A Little Princess. It’s from the 1995 film adaptation.

It’s not an abridgment of a quote from the book or even really applicable to its themes either. Burnett’s treatment of being a princess defines it as an attitude of maintaining one’s integrity and dignity despite adverse circumstances or the cruelty of others.

Nothing wrong with finding the quote from the film inspirational in some way! But it’s important to attribute it to the correct source and not to Burnett, who did not write it or anything like it.

See below for a quote from the text of A Little Princess on being a princess, for comparison.

“Whatever comes,” she said, “cannot alter one thing. If I am a princess in rags and tatters, I can be a princess inside. It would be easy to be a princess if I were dressed in cloth of gold, but it is a great deal more of a triumph to be one all the time when no one knows it. There was Marie Antoinette when she was in prison and her throne was gone and she had only a black gown on, and her hair was white, and they insulted her and called her Widow Capet. She was a great deal more like a queen then than when she was so gay and everything was so grand. I like her best then. Those howling mobs of people did not frighten her. She was stronger than they were, even when they cut her head off.”

This was not a new thought, but quite an old one, by this time. It had consoled her through many a bitter day, and she had gone about the house with an expression in her face which Miss Minchin could not understand and which was a source of great annoyance to her, as it seemed as if the child were mentally living a life which held her above the rest of the world. It was as if she scarcely heard the rude and acid things said to her; or, if she heard them, did not care for them at all. Sometimes, when she was in the midst of some harsh, domineering speech, Miss Minchin would find the still, unchildish eyes fixed upon her with something like a proud smile in them. At such times she did not know that Sara was saying to herself:

“You don’t know that you are saying these things to a princess, and that if I chose I could wave my hand and order you to execution. I only spare you because I am a princess, and you are a poor, stupid, unkind, vulgar old thing, and don’t know any better.”

This used to interest and amuse her more than anything else; and queer and fanciful as it was, she found comfort in it and it was a good thing for her. While the thought held possession of her, she could not be made rude and malicious by the rudeness and malice of those about her.

“A princess must be polite,” she said to herself.

And so when the servants, taking their tone from their mistress, were insolent and ordered her about, she would hold her head erect and reply to them with a quaint civility which often made them stare at her. “She's got more airs and graces than if she come from Buckingham Palace, that young one,” said the cook, chuckling a little sometimes. “I lose my temper with her often enough, but I will say she never forgets her manners. ‘If you please, cook’; ‘Will you be so kind, cook?’ ‘I beg your pardon, cook’; ‘May I trouble you, cook?’ She drops ‘em about the kitchen as if they was nothing.”

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabel de Clare 4th Countess of Pembroke (1172-1220 AD). Anglo-Irish women of the nobility in profile...

Isabel de Clare’s life is largely known in detail for her proximity to people in her life during the late 12th & early 13th centuries of Medieval England. Her parents and ancestors were of noble & royal extraction. Her husband rose through the ranks from son of a relatively minor noble to being the man regarded as the best knight and most trustworthy nobleman in all of the Angevin Empire and a powerful statesman who ruled in England in all but name for a brief period. In death he was lionized as the “greatest knight who had lived” and their children would either become nobles & warriors in 13th century England themselves or marry into other noble families of note.

All of this overlooks just how important, strong and capable Isabel was of her own merit. Something her husband and indeed Anglo-Norman law at the time recognized. Despite its male dominance, there were women capable of being major power players in the ranks of nobility & royalty and Isabel played a contribution to that. Her life offers us a unique glimpse into a noble woman’s life during the High Middle Ages in Western Europe.

Royal Roots, Birth & Early Life:

-Isabel de Clare was born circa 1172 AD, somewhere in Leinster (southeastern), Ireland. From the start she was a symbolic & physical bridge between two cultures. She was the result of a political but dutiful marriage, and her physical being would be of crucial importance in later years.

-Her father was Richard FitzGilbert, also known as Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (1130-1176). Richard would be best known to history by his nickname Strongbow. He was an Anglo-Norman nobleman of the De Clare family. The De Clare or Clare family originated in Normandy and came to England where they accompanied William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy who would become the first Norman King of England.

-The first Richard FitzGilbert (1035-1090) was a companion of Duke William and distant kinsman. They both shared a common ancestor in Richard I of Normandy (932-996), Count of Rouen & Duke of Normandy. The name De Clare was from the Norman French for a place name, to be from or “of” said location. As a reward for being companion to Duke William in the Norman Conquest of England. Richard FitzGilbert like other Norman nobles was granted landholdings in England, becoming the new English nobility which replaced the Anglo-Saxons of old. Richard’s particular land holding was in centered in the town of Clare in Suffolk England which made him the first Lord of Clare. He also gained territory in Tonbridge in Kent, England.

-Over the generations the family expanded its holdings in England and in the Welsh Marches, Anglo-Norman controlled portions of southern Wales. Strongbow’s father Gilbert de Clare (1100-1148) became 1st Earl of Pembroke under King Stephen of England, gaining control of important parts of the Welsh Marches, including the Pembroke peninsula in southwest Wales. He also held Striguil in southeastern Wales on the River Wye, forming the strategic border between England & Wales.

-Gilbert de Clare was married to Isabel Beaumont, a former mistress of King Henry I of England & daughter of Robert de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Leicester & his wife Elizabeth de Vermandois. Elizabeth was a French noblewoman was the paternal granddaughter of French King Henry I (1008-1060) of the House of Capet. While her maternal grandfather Herbert IV, Count of Vermandois (1028-1080) was a descendant of Charlemagne and the Carolingian dynasty of Franks. Also, by virtue of Henry I’ of France’s marriage to Princess Anne of Kiev, Strongbow and subsequently Isabel de Clare were direct descendants of the Kievan Rus’s royal ruling House of Rurik which ruled Medieval Ukraine & Russia. Also confirmed among their ancestors from this line were Swedish royalty, Polish tribal royalty & possibly Byzantine Greek royalty, if the debated connections regarding Anne of Kiev’s purported paternal grandmother (Anna Porphyrogenita) are indeed true.

-Isabel de Clare’s mother and the wife of Strongbow was Aoife MacMurrough of Eva of Leinster (1145-1188) an Irish princess who was daughter of Dermot MacMurrough, King of Leinster. Ireland at the time was not ruled by one king but was instead made up of several feudal petty kingdoms, Leinster being one of them located in the southeast of the country, a land of rivers, hills and the famed Wicklow Mountains. Aoife’s and subsequently Isabel’s ancestry in Ireland went back to various Irish petty kings & even the vaunted High Kings of Ireland, who ruled as a somewhat symbolic overlord of the other petty kings. This included her paternal ancestor through Brian Boru, High King of Ireland & King of Munster and founder of the O’Brien dynasty who defeated the Vikings at their settlement in Dublin in 1014, taking the area back for the Gaelic natives of Ireland after years of Viking rule. Though Brian Boru died in the process.

-Isabel de Clare’s parents came together in the 1170′s following a power struggle in Ireland between her maternal grandfather Dermot MacMurrough & then High King of Ireland, Rory O’Connor who worried that Dermot would become too powerful as King of Leinster, so he launched an invasion of Leinster, this forced Dermot off his throne and into exile in 1166.

-Dermot’s exile took him to the court of Henry II, King of England & Duke of Normandy who was in France at the time, trying to hold together his many French possessions (Normandy, Brittany, Aquitaine, Anjou etc.) which made up his Angevin Empire. Henry would not personally partake in restoring Dermot to the throne in Ireland, but he did authorize Dermot to negotiate and make mercenary use of some of his Anglo-Norman nobility and their knightly retinues. Strongbow would be one of these Norman nobles Dermot would negotiate with.

-Strongbow promised to assist Dermot in the recapture of his throne, in exchange for Aoife’s hand in marriage and kingship of Leinster upon Dermot’s death, co-ruling with Aoife to give it air of legitimacy among the native Irish. The Norman invasion of Ireland commenced in small waves as early as 1169 with Strongbow himself arriving in 1170 where his Anglo-Norman forces, some 200 mounted knights and 1,000-foot soldiers teamed with earlier Norman war parties from the prior year, they took the port city of Waterford, once a Viking a stronghold. Here Aoife & Strongbow were married, uniting the Irish royalty with Anglo-Norman nobility in a political manner.

-Children would of course cement this marriage with the birth of Isabel probably in 1172 and her brother Gilbert.

-Dermot’s gamble paid off, his Norman mercenaries overwhelmed the forces loyal to High King Rory O’Connor. The Gaelic Irish military in terms of arms & armor were no match for the Anglo-Normans who sported the most high-quality weapons and armor of their day in Western Europe. Dermot was once again agreed to be King of Leinster in agreement with O’Connor. However, his deals with his new son-in-law Strongbow & the other Anglo-Normans unintentionally and unbeknown to them opened the door to the start of England’s several centuries of involvement in Ireland...

-Dermot would die in 1171 shortly after the retaking of the kingdom, leaving his son and son-in-law (Strongbow) to claim kingship of Leinster. His son and Aoife’s brother claimed it under traditional Brehon law while his deal with Strongbow left it as part of the dowry for marriage.

-Meanwhile. Henry II of England was concerned about his Anglo-Norman nobles over in Ireland. Strongbow in particular had through marriage and acquisition of lands, begun a private colonization of Ireland. Other nobles who took part in Dermot’s operation did so too. This resulted in Henry and Strongbow making a deal, in exchange for keeping Leinster and the restoration of Strongbow’s English, Welsh & French landholdings, he would surrender the ports of Wexford, Waterford & Dublin to royal authority directly. He’d also be required to assist Henry on campaign in France against rebels. He was made in title by Henry II, Lord of Leinster & Justiciar of Ireland (chief justice). Henry II arrived in Ireland in late 1172 for a six month stay where royal troops directly loyal to him took over the key cities of Wexford, Waterford & Dublin from the earlier Anglo-Norman mercenaries. All the Anglo-Norman nobles who gained land in Ireland during the initial invasion were forced to pledge fealty to Henry II as Lord of Ireland in exchange for their right to keep their newly colonized lands. Likewise, the native Gaelic kings were to pledge fealty to Henry II as their feudal overlord, essentially ending the now meaningless institution of High King of Ireland. Waves of Anglo-Norman, Welsh, & Flemish colonists began to settle and establish new English towns in Ireland. Some established relations with the Gaelic Irish, intermarrying, becoming a new cultural group which would expand, ebb and flow over the centuries, the Anglo-Irish. Thus began a fusion of Anglo-Norman architecture, warfare, language and with a gradual cultural assimilation of Gaelic customs that began to blur the differences overtime until the early Anglo-Normans became just accepted as Irish. Nevertheless, politically the longer lasting implications of England’s occupation of Ireland had begun.

-Isabel de Clare was born into this new political realty, her maternal ancestral homeland permanently transformed within a few years due to her maternal grandfather’s personal struggle to regain power in his homebase. None of the the participants, including her parents & grandfather had the slightest notion of the longer-term implications of their decisions. Isabel & her brother were, nevertheless, the flesh and blood realty of this new political & cultural fusion. Meant in part as political bridges between two worlds.

-Strongbow intended for his son Gilbert to inherit Leinster and the various holdings in Wales, England and Normandy. His own death came about in 1176 following an infection of the leg. He was buried in Dublin, with his tomb & effigy still found Christ Church Dublin. Aoife took charge of her children’s upbringing hoping to ensure their inheritance. She was by many accounts fierce in this regard, she was also seemingly well-educated for anybody in that time period but especially a woman, a trait she passed on to Isabel. She is also said to have led Anglo-Norman & Irish loyalist troops into battle against those who tried to take Leinster from her, she earned the nickname Red Eva.

-Gilbert de Clare, died as a teenager around 1185. Thus, all the inheritance remained with his mother Aoife and would by right of Anglo-Norman law pass on to his nearest relative, his sister Isabel and any man she would marry.

-Aoife died in 1188 by some accounts, this left the teenage Isabel orphaned without and without her brother. She was, nevertheless, rightful heir to Leinster, the castles in Wales & England that had belonged to her father and paternal grandfather (Gilbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke). She was the 4th Countess of Pembroke in this line after her brother’s brief tenure. Isabel, became a royal ward of Henry II personally. Meaning he would ensure the safekeeping of her legal inheritance and person. He entrusted this to Ranulf of Glanville, Justiciar of England. She was therefore kept in London for her safekeeping.

-In practical terms this royal wardship was essentially a foster home for orphaned nobility until the king could marry them off to some other noble. Sometimes, other nobles would be entrusted as their personal guardian and be tasked with arranging the marriage of the ward to another noble, sometimes to their guardian’s child or even the guardian themself for personal gain. This would of course require the king’s blessing.

-Isabel was described as beautiful, kind & intelligent “the good, the wise and courteous lady of high degree.” She was among the wealthiest heiresses in the Angevin Empire (Henry II’s personal empire which through conquest, inheritance and diplomacy included all of England, parts of Wales, Ireland and most of Northern & Western France). She was well educated like her mother and could speak her father’s language of French, the courtly language of the English royalty and the Anglo-Norman nobility at the time. She could also speak her mother’s native Irish (Gaelic) & Latin, the language of clergy, diplomacy and government bureaucracy. This coupled with her bloodlines would be of tremendous political import, meaning she could navigate the Irish and Anglo-Norman cultures she was born of. Rather than her education in language, courtly manners, warfare, diplomacy and politics being perceived as a threat to any husband, it would have likely been seen as a great asset.

-Her hand in marriage was promised by Henry II, to one William Marshal in 1189. Marshal was himself an Anglo-Norman noble born and raised in England around 1147. He was the son of a relatively minor noble in England’s West Country with his mother coming from a more distinct Norman family. He came of age through training as a knight with his mother’s relative in Normandy, enduring a six-year apprenticeship in knightly warfare, court etiquette & the arts. He saw some combat but was assigned to the personal service of England’s Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine and then the service of her and Henry II’s son, Henry the Younger. They bonded especially in the late 1170′s by becoming famous knights on the European knightly tournament circuit that was just blossoming at the time. Marshal became perhaps the most renowned tournament knight of all, capturing or unhorsing some 500 knights. Henry the Younger would eventually die after Marshal served him for over a decade loyally.

-Marshal then found himself in Henry II’s personal service and during a war against the King of France who was briefly joined by Henry II’s son and heir Richard where he personally unhorsed Richard with a lance, killing the horse but sparing the prince. Supposedly, the only man to do so. After Henry II’s death, Richard rose to the throne of England & Normandy. He was preparing to go on Crusade to the Middle East and liberate Jerusalem from Muslim rule. He would in time be known as Richard the Lionheart.

-Despite Marshal’s recent opposition with King Richard, the new monarch kept Marshal in his service. He also fulfilled his father’s promise to wed Isabel de Clare to William Marshal. This would make Marshal not only a wealthy and increasingly influential knight but by right of marriage make him now one of the wealthiest landowners & nobles in the Angevin Empire.

Marriage, until death do you part;

-William Marshal & Isabel de Clare were married in August 1189 in London. There was an age difference, she was not quite 18 and he was in is early 40′s. Despite the political nature of the marriage, it appears to have been a genuinely happy one by all accounts. Neither party appears to have been unfaithful to one another. The written records show a great mutual appreciation for one another and produced 10 children, 5 sons and 5 daughters over the next several decades.

-Marshal was technically by right of marriage, Earl of Pembroke but he would not officially acquire the title in his own name until 1199, a decade after his marriage. Nevertheless, he was overlord of Leinster and Striguil and set about making improvements to the castles both he had acquired in England & France for loyal service to the monarchs but his marital gains in Wales & Ireland.

-For the first decade of marriage, William was in service to Richard the Lionheart, particularly when he was gone on Crusade, he stayed behind as a member of the ruling council. This kept him in England, Wales & France mostly, with little attention to affairs in Ireland. Isabel for her part focused on raising a family and supporting her husband as he navigated politics. Though his wartime commitments to defending England from rebels & the French throne often kept them separated. Isabel, appears to have been like her mother before devoted to ensuring the cultured learning of her children.

-Affairs in her native Ireland wouldn’t be pressing for the Marshal family until around the year 1200, during the reign of Henry II’s youngest son with Eleanor of Aquitaine, John. John became king after the death of his eldest brother Richard who had returned from years in the Crusades and then a captive in Germany from a rival monarch, found himself campaigning against Philip II of France (his father’s rival) to regain territory that had been lost under John’s regency of throne. John was eventually back in Richard’s good graces when the Lionheart died of infection from a crossbow wound fired by a rebel soldier in southern France where Richard was campaigning to suppress a revolt.

-John was now King of England and had a reputation for being paranoid, highly emotional and making rash decisions, making him more unpredictable than his older brothers and father.

-Marshal found himself both in John’s good graces and bad graces at various times over the years. He and Isabel were turning to press their rightful rule in Leinster in the early 1200′s despite John’s warnings he not to do so. John like his father Henry II had been concerned about Strongbow now worried Marshal and Isabel would be too powerful and independent in Ireland. Indeed, in the two decades since the Norman invasion of Ireland, the Anglo-Norman nobility who settled there had become accustomed to their own relative autonomy. Loyalty to the king was in name but in practice, so long as they didn’t rebel against the king, they were basically free to do as they please. John’s predecessors did little to enforce this and initially John was more concerned about England & France.

-Marshal & Isabel helped develop the town of New Ross in Leinster, an English town separate from the Gaelic towns nearby, it was peopled with English & Welsh colonists, many of whom were part of the Marshal family retinue and to whom they owed their feudal allegiance. The castles of Kilkenny, Trim & others were developed and expanded by Marshal & Isabel.

-Meanwhile, Marshal earned John’s ire for having paid homage to Philip II of France in exchange for retention of Norman lands after the French kicked John’s English armies out of Normandy, forever losing his ancestral duchy of Normandy to France.

-Concerned of Marshal’s power in Ireland and anger over his dueling homages to John in England and Philip in France. John organized for Marshal to come pay homage in England where he was duly placed under house arrest at the royal court. Meanwhile his own Justiciar in Ireland, Meiler Fitzhenry who had his own ambitions on Leinster invaded using his own Irish & Anglo-Norman forces with John’s blessing. John sought to teach Marshal a lesson and increase personal control over Ireland by having a Norman noble with more loyalty. It also worked in Fitzhenry’s favor.

-Marshal himself was considered fair if not especially popular among the Anglo-Normans already settled in Leinster under his rule. While the native Gaels were less than enthused by him or any other Anglo-Norman lord. Isabel, however, appears to have been the critical element & saving grace for Marshal. Given her ancestry including the native Irish rulers of Leinster and the Anglo-Norman new elite, her command of language & diplomacy appears to have held things together while this Anglo-Norman civil war with the king’s blessing raged in Ireland.

-in 1208 Fitzhenry’s men besieged Isabel (who was pregnant) and the Anglo-Normans who were loyal to Marshal all while Marshal himself and his sons remained personal hostages of King John. Only thanks to an alliance between Marshal’s & Isabel Anglo-Norman loyalists with another rival of Fitzhenry, Hugh de Lacy (1176-1242) Anglo-Norman noble who was first Earl of Ulster did the war come to an end in Marshal & Isabel’s favor. Isabel is said to have helped direct the defense of her castles under siege while de Lacy’s men came to their relief, defeating and capturing the men John had sent to assist Fitzhenry.

-Fitzhenry remained a noble in Ireland but he was removed as Justiciar. Marshal was released by John, and he was allowed to reunite with Isabel.

-Isabel’s day to day to involvement in the civil war is hard to gauge but almost certainly if not the military matters, the diplomatic ones she learned from her Irish princess mother, along with her symbolic blood ties to the Irish & Anglo-Norman nobility of Leinster still held important sway. As Marshal had said prior to his departure to his custody in England, all he had emanates from her. This was mostly true in a political and legal sense, but he appears to have meant it in a romantic sense since she was his faithful wife & mother of his children, the vessel to his dynastic future.

-In the coming years, Isabel & Marshal looked to marrying off their children to important Anglo-Norman nobility. Though successful in this regard and Marshal & Isabel have thousands if not millions of descendants today, none of their sons would bring about descendants meaning, their holdings in Ireland, Wales and England would transfer to other families since their daughters were married off into other noble families and hence the Marshal dynasty was short lived-in terms of male direct descendants. All five daughters Maud, Isabel, Joan, Eva & Sibyl all had children that lived and went onto have descendants that live into the modern era, including members of the British royal family today as well as numerous people in America and elsewhere due to colonial descendants from English nobility.

-Marshal found himself back in John’s good favor and counselled him during the rough times of the First Baron’s Rebellion (1215-1217). He also helped guide John to signing the famed Magna Carta, meant as a peace treaty to ensure certain royal guarantees for the rebellious nobility. Making Marshal one of the Magna Carta “signers”, though the peace was broken shortly thereafter, and John died of illness during rebellion. To make matters worse England’s civil war between nobles revolting against John’s excesses and those loyal to him, including Marshal now attracted the attention of the French king Philip II and his son Louis. The rebel barons now swore fealty to Louis and asked he take over as King of England. Marshal had been made guardian of John’s son 9-year son who was crowned Henry III, making him the 4th crowned King of England that Marshal would serve. Marshal was styled as “Guardian of the Realm” and swore to defending England and its rightful king from the predations of the rebel barons and the French pretender.

-As regent he was now the head of the country in practical matters, yet he was also 70 years old. Marshal would help Henry III and England’s royalist forces when the war when at age 70 and donning knight’s armor one last time he would lead a royalist force to defeat a combined Anglo (rebel)-French force in the Battle of Lincoln in May 1217. This along with the English naval victory over France at Sandwich ended the war in the royalist favor. Henry III was recognized by France at the rightful King of England and the rebels would be forgiven in exchange.

-Marshal won the war for England but his old age was catching up with him. He now set about as Regent of England on behalf of Henry III to try and restore the treasury which was drained under John. He also reissued updated versions of Magna Carta, later cited by historians as a cornerstone moment in the gradual expanding of human rights and democracy, though the original document was narrow in scope and intended for the nobility and the preservation of their rights against royal abuse. It would influence English common law and American Constitutional law in centuries to come.

-From 1217-1219 Marshal was the de-facto the ruler of England, he wasn’t always successful, but he did ensure some measure of peace and lay a foundation that Henry III’s other regents and the king himself could later build upon.

-Isabel remained faithful to the very when Marshal died at home near Reading England in May 1219. She was said to have wept uncontrollably at his passing and could not walk during his funeral procession to London where he was buried in Temple Church.

-Nevertheless, evidence shows that despite her husband’s passing she immediately set about ensuring inheritance was due. Writing the other regents that her lands in Ireland, Wales (minus Pembroke which went to their eldest son) and England were duly granted in her name. She also negotiated with the French king to ensure inheritance of her Norman lands. She even got William Marshal II, their eldest son the hand in marriage to Henry III’s younger sister Princess Eleanor, though this marriage would produce no heirs.

-Isabel’s son William Marshal II was effective as agent managing her various estates, but illness caught up with her in March 1220 and she died in Wales ten months after her husband’s death. She was buried Tintern Abbey near Striguil Castle, now Chepstow Castle which had belonged her father Strongbow and his father before him. Her grave is there to this day alongside her mother Aoife of Leinster. Though the abbey which the De Clare & Marshal families patroned is now in ruin, the grave markers are located on the ground.

-So passed a woman of high birth within the High Middle Ages of Western Europe. She was born of two different cultures and served as a living bridge immersed in the customs of both. As a result, she was given a unique and rich in-depth education unusual for anybody for the times but especially someone of her sex. Her life is mostly known for a seemingly peripheral role in relation to her family and acquaintances of great political importance but the evidence we have suggests she was regarded by especially her family and husband in particular as an absolutely vital and strong character in the events of the time. She played a part in shaping the history of nations, by dint of her birth and by her cultured and determined character.

#middle ages#england#france#anglo-norman#medieval#William Marshal#knighthood#chivalry#ireland#leinster#castles#normans#nomandy#de clare#strongbow#wales#chepstow castle#princesses#countess#brehon law#eva of leinster#high middle ages#henry ii#richard the lionheart

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

kingdom of averon, eden amidst devils

regions of averon:

northcambria (ruled by the monarch, currently House Medomai)

camber (ruled by House Cairn, with houses borick, vardyn, blackford, elderwood, cardwyn, and lorne in liege)

the march (ruled by House Vertor, with houses Florin, Rhogar, and Terrin in liege).

the highlands (ruled by House Acheron, with houses Durret, Capet, and Magnar in liege)

the arborlands (ruled by House Cafferen, with houses morwyn, perwyn, alden, teague, varodi in liege)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

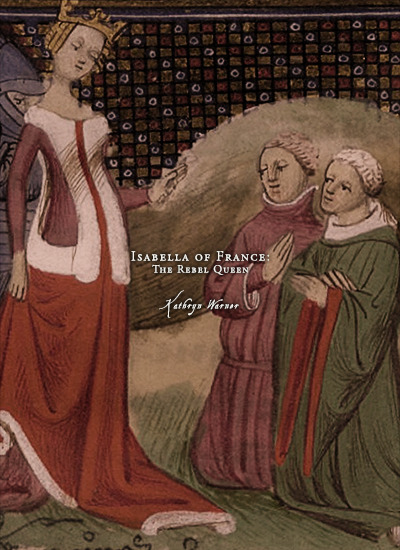

Favorite History Books || Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen by Kathryn Warner ★★★★☆

Isabella of France (c. 1295–1358), who married Edward II in January 1308, is one of the most notorious women in English history. In 1325/26, sent to her homeland to negotiate a peace settlement to end the war between her husband and her brother Charles IV of France, Isabella refused to return to England. She began a relationship with her husband’s deadliest enemy, the English baron Roger Mortimer, and with her son the king’s heir under their control, the pair led an invasion of England which ultimately resulted in Edward II’s forced abdication in January 1327. Isabella and Mortimer ruled England during the minority of her and Edward II’s son Edward III, until the young king overthrew the pair in October 1330, took over the governance of his own kingdom and had Mortimer hanged at Tyburn and his mother sent away to a forced but honourable retirement. Edward II, meanwhile, had died under mysterious circumstances – at least according to traditional accounts – while in captivity at Berkeley Castle in September 1327.

Though she was mostly popular and admired by her contemporaries, her disastrous period of rule from 1327 to 1330 notwithstanding, Isabella’s posthumous reputation reached a nadir centuries after her death when she was condemned as a wicked, unnatural ‘she-wolf’, adulteress and murderess by writers incensed that a woman would rebel against her own spouse and have him killed in dreadful fashion, or at least stand by in silence as it happened (the infamous and often-repeated ‘red-hot poker’ story of Edward II’s demise is a myth, but widely believed from the late fourteenth century until the present day). Isabella’s relationship with Roger Mortimer and her alleged sexual immorality, as well as her frequently presumed but never proved role in her husband’s murder, became a stick often used to beat her with; a typical piece of Victorian moralising by Agnes Strickland declared that ‘no queen of England has left such a stain on the annals of female royalty, as the consort of Edward II, Isabella of France’. Strickland’s work divided the queens of England, seemingly fairly arbitrarily, into the ‘good’ ones such as Eleanor of Castile and Philippa of Hainault, and the ‘bad’ ones such as Eleanor of Provence; Isabella of France, naturally, fell into the second category. Her reputation fared poorly between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and well into the twentieth: in the early 1590s the playwright Christopher Marlowe called her ‘that unnatural queen, false Isabel’, a 1757 poem by Thomas Gray was the first to apply the ridiculous ‘she-wolf’ nickname (which had been invented by Shakespeare for Henry VI’s queen Margaret of Anjou) to her, and in 1958, exactly 600 years after her death, Isabella was still being called ‘the most wicked of English queens’. The French nickname sometimes used for her, la Louve de France – the title of a 1950s novel about her by Maurice Druon – is simply the translation of the English word ‘she-wolf’ and has no historical basis whatsoever. (Although it is sometimes claimed nowadays that Edward II himself, or his favourite Hugh Despenser the Younger, called Isabella a ‘she-wolf’, this is not true; one fourteenth-century chronicler, Geoffrey le Baker, called her Jezebel, a play on her name, but otherwise no unpleasant nicknames for her are recorded until a few centuries after she died.) An academic work of 1983 unkindly calls Isabella a ‘whore’, and a non-fiction book published as late as 2003 depicts her as incredibly beautiful and desirable but also murderous, vicious and scheming, and claims without evidence that she ‘had murder in her heart’ towards her husband in 1326/27, called for his execution and was ‘secretly delighted’ when she heard of his death. Her contemporaries were mostly kinder. With the notable exception of Geoffrey le Baker in the 1350s, who was trying to promote Edward II as a saint and who detested Isabella, calling her an ‘iron virago’ as well as ‘Jezebel’, fourteenth-century chroniclers generally treated her well, and it is certainly not the case, as is sometimes claimed nowadays, that they called her a ‘whore’ or anything equally ugly and harsh because of her liaison with Roger Mortimer. Most fourteenth-century chroniclers seem uncertain whether Isabella even had an affair with Mortimer at all, and a few depict the two merely as political allies and call Mortimer Isabella’s ‘chief counsellor’, which may be a more accurate portrayal of their association than the romanticised accounts so prevalent in modern writing. In the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, writers have mostly been keen to write Isabella sympathetically and rescue her from the unfair calumnies heaped on her head for so long – an impulse to be applauded – but in doing so have tended to go too far in the opposite direction. As a result, Isabella is depicted nowadays as a tragic, long-suffering victim of marital cruelty, impoverished and deprived of her children, who is miraculously transformed in 1326/27 into a strong, empowered feminist heroine bravely fighting to end the oppression of her husband’s subjects and to get her children back. This is no more accurate than the old tendency to write her as an evil she-wolf.

Portrayals of Isabella of France down the centuries say far more about the societies that produced them and the prevailing attitudes towards women and their sexuality, in particular women who step outside the bounds of traditionally conventional behaviour, than they do about Isabella herself. For all the piles of chronicles, non-fiction books, novels, plays, poems and articles written about the queen over the last 700 years, have we come close to knowing the real Isabella at all, or has she only ever been an image of what we think she must have been like, formed from our own experiences and cultural expectations? Can we discover the real Isabella underneath the centuries of myth? The queen would surely not recognise herself and the events of her life in the way she has so often been portrayed: either as a malevolent and vengeful murderer, or as a despondent martyr treated appallingly for many years by her despised husband and his lovers, or as a time-traveller parachuted into the Middle Ages from the twenty-first century with modern attitudes towards sexual equality. Isabella was far more complex: neither wicked nor saintly, she was a fascinating human being with both excellent qualities and flaws, who did laudable things and other things not so praiseworthy. She was a product of her time and place – Europe in the fourteenth century – intensely proud of her royal birth and high position, steeped in Christianity, taught that she must marry in a political alliance to benefit her father’s kingdom and happy to do so, taught also that she must obey her husband and bear his children.

#historyedit#litedit#isabella of france#house of capet#house of plantagenet#medieval#french history#english history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics#history books

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France"

The hour that struck the death of Louis VIII was arguably the most critical in the history of the Capetian family. The new king, one day to be St Louis, was still a child. The trend of events in the previous two reigns had brought the higher nobility to realise that its independence would soon be seriously threatened. But a unique opportunity was raised to the regency of the queen-mother, Blanche of Castile, on the pretext that she was a woman and a foreigner. Yet this was not the first occasion on which the king's widow had acted as regent, nor the first on which a queen had played a part in politics. Philip Augustus had been the first Capetian not to involve his wife in the government of his realm. Before his time the queens of France had often intervened in affairs of state. Constance of Arles, not content with making married life difficult for Robert the Pious, had wanted to change the order of succession to the throne. She had led the opposition to Henri I, provoking and upholding his brothers against him, and she was perhaps responsible for the separation of Burgundy from the royal domain, to which Robert the Pious had joined it. Anna of Kiev, after the death of her husband Henri I, had been one of the regents, and it was only her second marriage, to Raoul de Crépy, that took her out of politics. Bertrada de Montfort's influence over Philip I had been notorious, and so had her hostility to the heir to the throne, whom she had even been accused of trying to poison. Adelaide of Maurienne, despite a physical personality before which Count Baldwin III of Hainault is said to have recoiled, had held considerable sway over Louis VI, procuring the disgrace of the chancellor, Etienne de Garlande, and egging on Louis to the Flemish adventure from which her brother-in-law, William Clito, was to profit so much. Eleanor of Aquitaine- as St Bernard had complained- had more power than anyone else over Louis VII as long as their marriage lasted. Louis VII's third wife, Adela of Champagne, had appealed to the king of England for help against her son Philip Augustus when he had sought to free himself of the tutelage of her brothers of Champagne. Later, reconciled with Philip, Adela had been regent during his absence from France on crusade. From the beginnings of Capet rule, the queens of France had enjoyed substantial influence over their husbands and over royal policy.

But Blanche of Castile was to play a greater role than any of her predecessors. To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France. For from 1226 until her death in 1252 she governed the kingdom. Twice she was regent: from 1226 to 1234, while Louis IX was a minor, and from 1248 to 1252 during his first absence on crusade. Between 1234 and 1248 Blanche bore no official title, but her power was no less effective. Severe in personality, heroic in stature, this Spanish princess took control of the fortunes of the dynasty and the kingdom in outstandingly difficult circumstances. For in 1226 there arose the most redoubtable coalition of great barons which the House of Capet ever had to face. Loyalty to the crown, so constant a feature of the past, seemed to be in eclipse. This was at any rate true of the barons who revolted, for they appear to have tried to seize the person of the young king himself- an attempt without parallel in Capetian history.

Blanche of Castile threw herself energetically into the struggle over her son and his throne. Taking her father-in-law, Philip Augustus, as her model, she won over half her enemies by craft, vigorously gave battle to the rest, and enlisted the alliance of the Church, including the Pope himself, and of the burgess class, which in marked fashion took the side of the royal family. Blanche was able to fend off Henry III of England, who tried to take the opportunity of recovering his ancestral lands, lost by John to Philip Augustus. She broke up the baronial coalition and reduced to submission the most dangerous of the rebels, Peter Mauclerc, Count of Brittany, and Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse. She adroitly took advantage of her victory to re-establish- this time definitively- the royal power in the south of France: her son Alphonse was married to the daughter and heiress of Raymond of Toulouse. The way was now open for the union of all Raymond's rich patrimony with the royal domain.

The Capetian monarchy emerged all the stronger from a crisis which had threatened to overwhelm it. Blanche felt it her duty not to rest on her laurels. After her son came of age she continued to make herself responsible for good and stable government. By the force of her example she drove home the lessons which Philip Augustus seems to have wanted to press upon his grandson when they had talked together. To Blanche's initiative must be credited the measures taken to suppress the dangerous revolt of Trencavel in Languedoc, as also those taken to defeat the coalition broken up after the battle of Saintes. On these occasions Louis IX did no more than carry out his mother's policy. When he went off on crusade, Blanche one more officially shouldered the government of the kingdom. She maintained law and order, prevented the further outbreak of war with England, and successfully pressed on with the policy which was to lead to the annexation of Languedoc. Likewise it was she who refurnished her son's crusade with men and money, and she took all the steps necessary for the safety of the kingdom when Louis was captured in Egypt.

Robert Fawtier- The Capetian Kings of France- Monarchy and Nation (987-1328)

#xiii#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#blanche de castille#queens of france#regents#louis viii#louis ix#philippe ii#constance d'arles#robert ii#henri i#anne de kiev#philippe i#bertrade de montfort#adélaïde de savoie#louis vii#étienne de garlande#st bernard#aliénor d'aquitaine#adèle de champagne

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Death and burial of Philippe IV le bel of France.

#art#manuscript#illuminated manuscripts#philippe iv de france#maison capét#maison capétienne#house capet#phillip iv of france

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Congratulations, Fawn! You have been summoned to Moscow as AGNES OF BURGUNDY (LILY JAMES). To accept your invitation, please refresh our guidelines, checklist, and send in your muse(s)’ blogs within (24) hours.

AGNES OF BURGUNDY, the 32 year-old TSAREVNA has arrived from MOSCOW. The SNOW LEOPARD resembles LILY JAMES and is both +PERCEPTIVE and –CONTRARY. They are a member of the HOUSE OF CAPET AND VASILYEVICH and remind the poets of SUCCULENT APPLES / MORNING DEW ON LUSH FLORA / GOLD TARNISHED BY NEGLECT YET STILL GLIMMERING WITH A NOBLE WINK IN THE RISING SUN / A KISS GOODBYE, BRIGHT RED, WITH AN IRON-RICH AFTER TASTE. In the annals of history, they will be remembered in the year of 1319 as a PAWN. One day they may rise to greatness, though greater men and women have surely failed. (fawn — she/her — 21+ — est)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things to remember about the Hundred Years War

Ever since 1066, the king of England held lands in France as a vassel of the king of France. Sometimes more than half of the country belonged to him. This situation was untenable. In 1224, all but Gascony was reconquered by the French, but this piece of land (which, amongst others, has Bordeau) produced more revenue than the whole of England.

In 1328, the last of the main branch of the Capet family, Charles IV, died without heir. The French lords decided that Philippe of Valois (Philip VI) were to become the next king, whereas the king of England, Edward III, was the nephew of the lst French king. Edward, being a minor, initially agrees to this, but later takes up arms. He would become one of the best kings England has ever had, with a golden reign of half a century.

In 1337, Philip VI declared that Aquitaine no longer belonged to Edward III. Most historians consider this the beginning of the Hundred Years War.

In 1340, Edward III declared himself king of France

The English used the technique of 'chevauchée', destroying the land and thereby the morale and revenue of the people of France.

There was proxy-war going on in Brittany, France.

In 1346, the Battle of Crezy was the first in a series of battles in which French mounted knights lost to smaller armies of English longbow-soldiers.

The French king, John II, was taking prisoner during one of these battles, the battle of Poitiers in 1356. His son, the later Charles V, effectively ruled in his name. John would be able to return thanks to a treaty, but as Louis of Anjou escaped and therefore broke the rules, he willingly returned to England, eventually dying there. He also wrote poetry.

Bertrand de Guesclin, one of the most badass generals ever.

So many troubles, a mad French king who thought he was made of glass, but end 14th century, the French had a capable king whereas in England the situation was bad with the end of Plantagenet rule and the beginning of the house of Lancaster on the throne. As the golden generation passed.

Horrible Azincourt in 1415.

The mad Charles VI signed the Treaty of Troyes in 1420, making Henry V the regent and heir to his throne, surpassing his own son ( the later Charles VII)

After the battle of Verneuil, known as the Second Azincourt, the situation was so bad that the later Charles VII considered fleeing the country. Joan of Arc completely turned French morale around, helping them to break the siege of Orleans and then getting Charles VII coronated. Of course, the same Charles did nothing to save her from her horrible fate.

The tide had been turned in favour of the French. An important turning point was the 1429 Battle of Patay, also known as the 'English Azincourt', which proved that the English could be defeated in open battle.

#dark academia#european history#history#middle ages#france#england#french history#english history#joan of arc#hundred years war

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Congratulations, Yerin! You have been summoned to Moscow as PHILIP DE ROUVROY. To accept your invitation, please refresh our guidelines, checklist, and send in your muse(s)’ blogs within (24) hours.

PHILIP DE ROUVROY, the TWENTY-EIGHT year-old COUNT OF CHAMPAGNE has arrived from VERSAILLES, FRANCE. The FACADE resembles TIMOTHEE CHALAMET and is both +MAGNETIC and –CUNNING. They are a member of the HOUSE OF CAPET and remind the poets of A VENUS FLYTRAP CLOSING AROUND ITS PREY, GOLDEN FLAME FLICKERING IN A CRUMBLING CASTLE, BECOMING THE IDEAL AND LOSING YOURSELF IN THE PROCESS. In the annals of history, they will be remembered in the year of 1319 as a PLAYER. One day they may rise to greatness, though greater men and women have surely failed. (yerin — she/her — 22 — gmt+9)

2 notes

·

View notes