#Plataea

Text

The Spartans at the Battle of Plataea by Edward Ollier for Cassell's 1890 "Illustrated Universal History."

#spartans#spartan#plataea#battle of plataea#art#history#ancient greece#greece#ancient greek#greek#phalanx#europe#european#achaemenid empire#persia#persian#invasion#battle#edward ollier#illustration#aristodemus

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

Power Dynamics in State Relations – A History Lesson (Part III)

Note: This is the third and final part of a three-part essay. If you haven’t read the first two parts published in the previous two weeks, I recommend that you read them first before reading this.

The Plataeans admitted that they had indeed become enemies of Sparta, but they attributed this to the Spartans themselves, who had rejected their plea for help against the Thebans (3.55.1). Instead,…

View On WordPress

#Alliances#Ancient Greece#Athens#Cersei Lannister#Great Power Competition#Great Powers#Hellenes#Interstate Relations#Justice#Loyalty#Major Power Conflict#Peloponnesian League#Peloponnesian War#Persians#Plataea#Plataean-Theban Dispute#Sparta#Thebes#Thucydides#War

0 notes

Photo

Ligue de Délos 1: des Origines à la Bataille de l'Eurymédon

Ce texte fait partie d'une série d'articles sur la ligue de Délos.

Lire la suite...

1 note

·

View note

Text

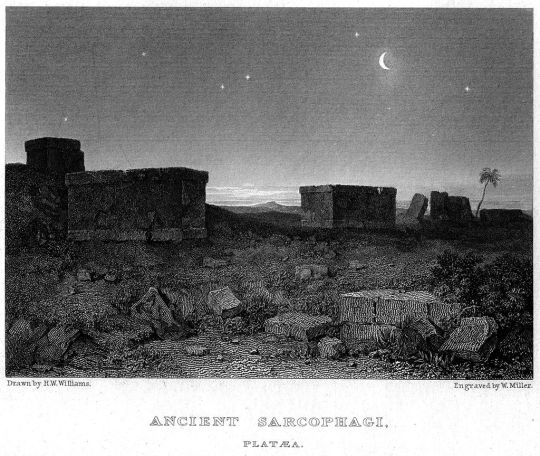

Ancient Sarcophagi, Plataea. Engraving by William Miller published in Select Views In Greece With Classical Illustrations.

#saw this one in class#the moon today looked like that#plataea#ancient greece#ancient history#engraving

1 note

·

View note

Photo

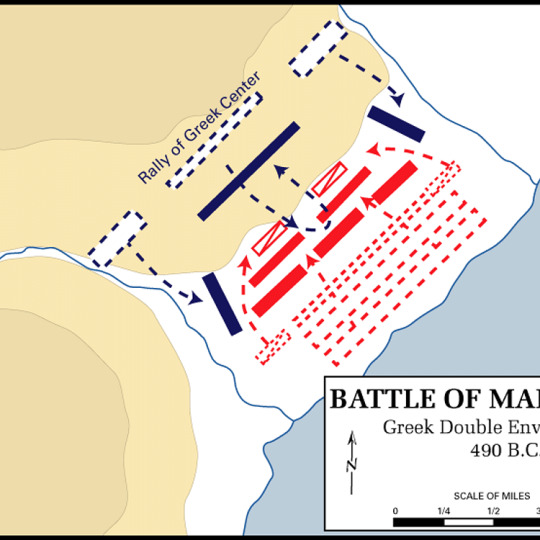

Batalla de Maratón

La batalla en la llanura de Maratón, en septiembre del 490 a.C., entre los griegos y el ejército invasor del rey persa Darío I (quien reinó del 522 al 486 a.C.), se tradujo en una victoria que pasaría a la posteridad como el momento en que las ciudades-Estado griegas mostraron al mundo su coraje y su excelencia y consiguieron la libertad. Aunque, en realidad, la batalla solamente pospuso las ambiciones imperialistas de los persas y después vendrían otras batallas más importantes, Maratón mostró por primera vez que el poderoso Imperio aqueménida podía ser derrotado. La batalla luego se representaría en el arte griego —literatura, escultura, arquitectura y cerámica— como un momento crucial y determinante en la historia de Grecia.

Leer más...

0 notes

Text

“The meal after the victorious battle of Plataea

According to Herodotus, the historian who described the Greek-Persian wars in detail, when the Spartan Commander-in-Chief Pausanias, after the victorious battle of Plataea, entered the scene of the killed Persian General Mardonius:

"... he ordered the bakers and the cooks to prepare the dinner Mardonius usually enjoyed. When Pausanias saw the luxurius daybeds, as well as the gold and silver tables loaded with the majestic dinner, he was surprised. As a joke, he ordered his own servants to prepare a Spartan dinner. The difference was so great that he laughed, called all the Generals of the Greeks and said to them, pointing to the two dinners: "Greeks, I called you here to show you the foolishness of the Median ruler who dines like this everyday and moved against us to steal our poverty."

We know today many nutritional details of the above scene, namely that the Greek General's meal did not stand out from the hoplites battling under his command. The ration was based on barley bulgur and unleavened barley bread, olives preserved in brine, onions and cured fish wrapped in fig leaves. In his haversack every soldier had salt and thyme to flavor the food, dried figs and a small spit perhaps, for the rare occasion that he would find meat. The army's logistics provided also goat cheese, fresh fruit (figs and grapes in the case of the Battle of Plataea, which took place in late August) and wine diluted with water to give courage to the fighters.

The Persians, who, in their vast and multinational troops, served Greeks, Indians and Ethiopians, were supplied by their Theban allies. They also ate barley bread, along with some goat meat, dried dates and almonds. However, the pyramidal structure of the Persian army required Mardonius and his high rank officers to enjoy roasted ducks and peacocks, pilaf flavored with cardamom, honey dripping sweets, wine made from dates and strong barley beer.”

Source: https://olyrafoods.com/blogs/wisdom-treats-blog/the-meal-after-the-victorious-battle-of-plataea

Olyra is the site of a Greek businessman who makes alimentary products inspired by the ancient Greek diet. The information he provides about the culinary habits of ancient Greeks and Persians when these peoples campaigned seems trustworthy.

I remind here that the question of the motivation of the Persian attempt to conquer Greece is a complex one in Herodotus. But the story reported here illustrates well the theme of the imperial hybris, i.e., of the desire of empires and elites which have already too much to acquire even more through further conquest and expansion.

I remind also that this report is not a simplistic illustration by Herodotus of some cliché of “Oriental decadence”, as Mardonius is portrayed in the Histories as aggressive and prideful, but also as competent and brave.

And of course the tragic irony of the same story is that Pausanias, the victor of Plataea and savior of the Greek freedom, the defender of the austere Greek way of life face to the Persian culinary luxury, not only adopted some time later the lavish lifestyle of the Persian nobility, but he was even accused of plotting with Xerxes for the subjugation of Greece and was put to death for this reason by the Spartans - through starvation...

Bust of Pausanias, in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

The Falcata & Kopis are one of my favorite 🗡's

I'm lucky to have been able to get sponsored to attend the 2500th Anniversary of the Battle of Plataea!💪🏿

Greece is still one of my most epic adventures to date!⚔️

On my way home, I got to attend a fun shoot too!📷

#Kult of Athena#KultOfAthena#Simply Samurai#SimplySamurai#Seto Waddell#Spencer Waddell#sword#swords#weapon#weapons#blade#blades#Falcata#Kopis#Hoplite#Greece#Battle of Plataea#Instagram#videos

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

to be honest id rather fucking kill myself than learn about eukaryotic gene expression right now. but i must soldier on

#at the end of this dark terrible tunnel lies the promise of being able to read about the siege of plataea.#and go thrifting.#so i must soldier on.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The meaning of historical events can vary in both the timescale it takes them to happen and how much brief events can cast very long shadows:

There are periods in history fairly short in duration but long-lived in effect, and ones that teach some unwelcome, at times, and ironic lessons. This one is one of the classics. On the one hand you have all the things beloved by more modern historical foci. The rise of new religious and social phenomena, the realities that the great armies were the vain product of claims to assert this, the unexpected reality that it was none of the established powers but semi-barbarian Macedon that ultimately remade the world in spite of the efforts of its predecessors.

And then then there's the other reality, the one that fits more poorly that the sequence is decided not by the deeper events but by Leuctra, Mantinea, Charonea, and Gaugamela. The deeper phenomena might take centuries and then in a single afternoon of bloodshed an army decides things that brush both for and against these patterns. It was not the deeper patterns of rival hegemonic structures of proto-fascist land empire Sparta and sea empire with mercantile aspects Athens that decided events, it was the Padishah of Iran's money and the Spartan fleet it financed.

It was not Thebes quietly building the first truly professional full-time standing army that decided things at Leuctra and Mantinea, in a way, mostly because the Thebans discovered some of the same limits that would later face the Roman Empire. That a full-time army was an expensive thing and a bloody battle can be as ruinous in victory as in defeat.

And it was the semi-barbarian Macedonian state inventing both new approaches to cavalry and the Phalanx and an even larger professional army that toppled the centuries-old multi-continental Iranian empire of the Achaemenid dynasty at Gaugamela. There were no deeper systemic fault lines that broke the empire, the empire of Darius fell as that of the Sassanians would, in a battle that was fought and lost against an underestimated and hostile enemy, and in the process the world was never the same again.

And that, ultimately, is why even with the newer emphases of history the older one focused so much on kings and battles. Even rather late in history, as at Bannockburn, Sekhigahara, Mukden, and Stalingrad it was a battle that set the deeper processes in motion, without which they could not happen. This particular timeframe from Plataea to the death of Alexander the Great is a time that illustrates both this pattern at its grandest and the deep faultlines that last within it.

9/10.

0 notes

Text

Despite Sparta’s reputation for superior fighting, Spartan armies were as likely to lose battles as to win them, especially against peer opponents such as other Greek city-states. Sparta defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War—but only by accepting Persian money to do it, reopening the door to Persian influence in the Aegean, which Greek victories at Plataea and Salamis nearly a century early had closed. Famous Spartan victories at Plataea and Mantinea were matched by consequential defeats at Pylos, Arginusae, and ultimately Leuctra. That last defeat at Leuctra, delivered by Thebes a mere 33 years after Sparta’s triumph over Athens, broke the back of Spartan power permanently, reducing Sparta to the status of a second-class power from which it never recovered.

Sparta was one of the largest Greek city-states in the classical period, yet it struggled to achieve meaningful political objectives; the result of Spartan arms abroad was mostly failure. Sparta was particularly poor at logistics; while Athens could maintain armies across the Eastern Mediterranean, Sparta repeatedly struggled to keep an army in the field even within Greece. Indeed, Sparta spent the entirety of the initial phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), failing to solve the basic logistical problem of operating long term in Attica, less than 150 miles overland from Sparta and just a few days on foot from the nearest friendly major port and market, Corinth.

The Spartans were at best tactically and strategically uncreative. Tactically, Sparta employed the phalanx, a close-order shield and spear formation. But while elements of the hoplite phalanx are often presented in popular culture as uniquely Spartan, the formation and its equipment were common among the Greeks from at least the early fifth century, if not earlier. And beyond the phalanx, the Spartans were not innovators, slow to experiment with new tactics, combined arms, and naval operations. Instead, Spartan leaders consistently tried to solve their military problems with pitched hoplite battles. Spartan efforts to compel friendship by hoplite battle were particularly unsuccessful, as with the failed Spartan efforts to compel Corinth to rejoin the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League by force during the Corinthian War.

Sparta’s military mediocrity seems inexplicable given the city-state’s popular reputation as a highly militarized society, but modern scholarship has shown that this, too, is mostly a mirage. The agoge, Sparta’s rearing system for citizen boys, frequently represented in popular culture as akin to an intense military bootcamp, in fact included no arms training or military drills and was primarily designed to instill obedience and conformity rather than skill at arms or tactics. In order to instill that obedience, the older boys were encouraged to police the younger boys with violence, with the result that even in adulthood Spartan citizens were liable to settle disputes with their fists, a tendency that predictably made them poor diplomats.

But while Sparta’s military performance was merely mediocre, no better or worse than its Greek neighbors, Spartan politics makes it an exceptionally bad example for citizens or soldiers in a modern free society. Modern scholars continue to debate the degree to which ancient Sparta exercised a unique tyranny of the state over the lives of individual Spartan citizens. However, the Spartan citizenry represented only a tiny minority of people in Sparta, likely never more than 15 percent, including women of citizen status (who could not vote or hold office). Instead, the vast majority of people in Sparta, between 65 and 85 percent, were enslaved helots. (The remainder of the population was confined to Sparta’s bewildering array of noncitizen underclasses.) The figure is staggering, far higher than any other ancient Mediterranean state or, for instance, the antebellum American South, rightly termed a slave society with a third of its people enslaved.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Héros de Marathon (The Heroes of Marathon) by Georges Rochegrosse

Greek troops rushing forward at the Battle of Marathon 490 BC

#battle of marathon#athens#plataea#art#georges rochegrosse#history#athenians#achaemenid empire#persian#invasion#antiquity#ancient greece#greece#ancient greek#ancient#greek#europe#european#heroes#troops#soldiers#battle#war#marathon#art nouveau

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Power Dynamics in State Relations - A History Lesson (Part II)

BK K Blogs brings timeless lessons from the Peloponnesian War!

Continue your journey with the second part of this three-part series on the intricacies of power, politics, and betrayal in state-to-state relations and international conflicts.

View On WordPress

#Alliances#Ancient Greece#Athens#Great Power Competition#Great Powers#Hellenes#Interstate Relations#Justice#Major Power Conflict#Peloponnesian League#Peloponnesian War#Persians#Plataea#Plataean-Theban Dispute#Sparta#Thebes#Thucydides#War

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pausanias (général)

Pausanias (510 - 465 av. J.-C.) était un régent et général spartiate qui connut la gloire en menant une force grecque combinée à la victoire sur les Perses lors de la bataille de Platée en 479 avant notre ère. Célèbre pour son manque de modestie à l'égard de son propre talent, il fut accusé de collusion avec les Perses tout au long de sa carrière et, malgré des succès à Chypre et à Byzance, il connut une fin particulièrement peu glorieuse. Il ne faut pas le confondre avec Pausanias, écrivain voyageur grec du IIe siècle de notre ère.

Lire la suite...

1 note

·

View note

Text

Corinthian helmet found with the soldier's skull still inside from the Battle of Marathon which took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece.

2,500 years ago, on the morning of September 12th, 10,000 Greek soldiers gathered on the plains of Marathon to fight the invading Persian army. The Greek soldiers were composed mostly of citizens from Athens as well as some reinforcements from Plataea. The Persian army had 25,000 infantrymen and 1,000 cavalry.

According to legend, a long-distance messenger by the name of Phidippides was sent to Athens shortly after the battle to relay the news of victory. It has been said that he ran the entire distance from Marathon to Athens, a distance of approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi), without stopping, and bursted into the assembly to declare, "We have won!", before collapsing and dying. This story differs quite a bit from Herodotus' account which mentions Phidippides as the messenger who ran from Athens to Sparta, and then back, covering a total distance of 240 km (150 mi) each way.

#history#sparta#spartan#this is sparta#persia#Greece#war#battle#lonely planet#vibes#good vibes#lifestyle#style#aes#aesthetic#aesthetics#helmet

101 notes

·

View notes

Photo

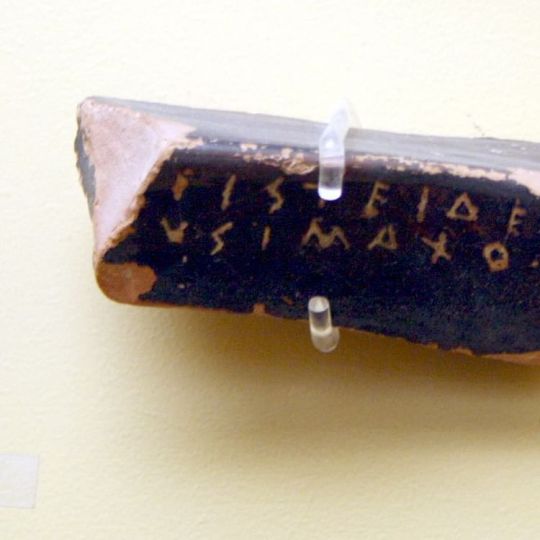

Arístides

Arístides (década de 520 - en torno a 467 a.C.) fue un estadista ateniense y comandante militar galardonado con el título honorífico de "el Justo" por su consistente servicio y comportamiento devoto en el gobierno Ateniense. A pesar de ser excluido por la asamblea ateniense, Arístides regresó para comandar tropas con gran éxito en las batallas de Salamina y Platea durante las guerras médicas al principio del siglo V a. C. Arístides, es el tema de una de las biografías del libro Vidas Paralelas de Plutarco.

Leer más...

0 notes

Text

″Food and the Philosophy of Empire: Herodotus 9.82

After the Battle of Plataea, Herodotus relates an anecdote about Pausanias’ reaction to Persian wealth. When he comes across Xerxes’ tent, he has the Persian slaves prepare a typical meal of the Persian elite. He then has his own slaves prepare a traditional Spartan meal. Pausanias is amused at the difference and calls the Greeks together, saying “my purpose in asking you all here is to show you how stupid the Persian king is. Look at the way he lives and then consider that he invaded our country to rob us of our meager portions!” (9.82). Scholarly response to this scene has been two-fold. First, Herodotus has Pausanias set up a display that proves one of the main themes of the Histories: that soft countries should not attack hard ones (Bowie 2003, Vasunia 2009). Second, the scene, along with Pausanias’ laughter, serves to foreshadow Pausanias’ eventual Medizing (Fornara 1971; Lateiner 1989). I propose that Herodotus includes this scene in order to highlight cultural difference and to show that Pausanias takes the wrong lesson from the Persian meal. His misinterpretation foreshadows not only his own downfall, but also problems in how Sparta exercises power.

Herodotus creates a strong association between food and power in his presentation of the Persians (Munson 2001). When Croesus wants to attack the Persians, his advisor Sandanis warns him against it because the Persians’ “food consists of what they can get, not what they want” (1.71). If Croesus wins, he will gain nothing from it; but if he loses, he will lose everything. His statement is somewhat undercut, however, by his description of how Cyrus incites his Persians to rebel against the Medes, their first step towards empire. As an object lesson on conquest, he sets up two days, one of hard work clearing land and one of feasting, and then goes on to explicitly connect slavery with working the land and freedom with conquest and eating good food (1.127). This connection is reinforced by Cyrus’ advice at the end of the Histories: “it is impossible for one and the same country to produce remarkable crops and good fighting men” (9.122). The Persians associate luxury with conquest.

The relationship between Spartan food and power is not emphasized in the Histories, although he does mention the communal mess as one of Lycurgus’ innovations on the Spartan constitution (1.65). Our picture of Spartan meals comes from later sources. Xenophon plays on the comparative meal scene in Herodotus at the beginning of the Cyropaedia, where he compares Persian and Median meals. Plutarch describes the simple Spartan meal in detail in his Life of Lycurgus. Spartan food is simple and signature. They avoid outside influences in their lives and in their food (Hodkinson 2000). The Spartans associate simplicity with power.

The comparison of the meals after Plataea is paradigmatic for the misunderstanding between the two cultures. Herodotus tells us that the Persians enjoy large meals with many courses—this is analogous to enjoying their large empire with many different subject states. The Persians attack so that they can continue to have big meals. It is not a matter of amassing wealth, but rather maintaining a military society instead of having to shift into an agrarian one (a practice analogous to the Spartan practice of keeping their helots). The Persians will use and enjoy their wealth and they are warlike; their culture values warfare as a means and luxury as the goal. The Spartans value the military life for itself, and put limits on the trapping of wealth in all aspects of their lives. The Persians seek to strengthen their center by bringing more in; the Spartans strengthen their center by protecting it from influence. We can see this in how Sparta interacts with other city states and exerts its hegemonic power. Thus, the meals are emblematic of two kinds of power, rather than an ironic comparison of apparent strength.”

Sydney Roy Food and the Philosophy of Empire: Herodotus 9.82 (abstract)

Source; https://camws.org/meeting/2013/files/abstracts/134.Food%20and%20the%20Philosophy%20of%20Empire.pdf

Sydnor Roy, Ph.D. in Classical Studies, UNC-Chapel Hill, is Assistant Professor at the Texas Tech University, Classical and Modern Languages and Literatures

2 notes

·

View notes