#battle of marathon

Text

The Athenian Messenger Pheidippides Delivers News of the Victory at Marathon

by Frank Moss Bennett

#pheidippides#art#frank moss bennett#marathon#messenger#victory#battle of marathon#athens#athenian#history#ancient greece#ancient greek#greek#greece#persian#invasion#persia#europe#european#battle#war#classical antiquity#antiquity#ancient#run#runner#race#running

362 notes

·

View notes

Photo

📍𝗠𝗮𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗵𝗼𝗻, 𝗔𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗻𝘀, 𝗚𝗿𝗲𝗲𝗰𝗲 🇬🇷

The Park, founded in 2000, is the most important wetland in Attica. The area of the Park reaches 13,000 acres. Historically, the site is identified with the field of the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), there was the Persian camp. The forest is at risk of fires due to the composition of the vegetation. The area belongs to the Natura 2000 network with 115 species of birds and endangered species of fish, reptiles and amphibians.

Photo and commentary by Vasilis Chrisanthopoulos.

#greece#europe#history#landscape#wetlands#bird's eye view#nature#natura 2000#travel#battle of marathon#marathonisi#schinias#sterea hellas#attica#central greece#mainland#greek facts#greek history

196 notes

·

View notes

Photo

At the Battle of Marathon, a vastly outnumbered force of Greek hoplites saved Athenian democracy and protected the course of Western civilization.

Credit: Royal Ontario Museum

#Battle of Marathon#Greek#Western civilization.#Helmet#Soldier’s Skull Still Inside#photo#museum#antique#royal ontario museum#photography

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Idea of Marathon

The Idea of Marathon

Battle and Culture

Sonya Nevin (Author)

Published Feb 10 2022

Publisher Bloomsbury Publishing

Description

The Battle of Marathon changed the course of history in ancient Greece. To many, the impossible seemed to have been achieved - the mighty Persian Empire halted in its advance. What happened that day, why was the battle fought, and how did people make sense of it? This bold new history of the battle examines how the conflict unfolded and the ideas attached to it in antiquity and beyond. Many thought the battle offered lessons in how people should behave, with heroism to be emulated and faults to be avoided. While the battle itself was fought in one day, the battle for the idea of Marathon has lasted ever since. After immersing you in the battle, this work will help you to explore how the ancient Athenians used the battle in their relations between themselves and others, and how the battle continued to be used to express ideas about gods, empire, and morality in the age of Alexander and his successors, at Rome and in Greece under the Roman Empire, and in the ages after antiquity, even in our own era, in which Marathon plays a remarkable role in sport, film, and children's literature with each retelling a re-imagining of the battle and its meaning. A clash of weapons, gods, and principles, this is Marathon as you've never seen it before!

Table of Contents

Introduction

1. Athenians at a Turning Point

2. The Greek World

3. Persia

4. Revolt in Ionia

5. The Plain of Marathon

6. The Fight

7. Surviving Marathon

8. Events after Marathon

9. Memories of Marathon in Fifth-Century Art and Literature

10. Marathon beyond the Fifth-Century

11. Marathon under Rome

12. Marathon after Antiquity

Afterword

Source: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/idea-of-marathon-9781788314206/

Dr. Sonya Nevin, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge is an ancient historian with a special interest in ancient war narratives and in modern receptions of Classical Antiquity. She also runs (with the animator Steve Simons) the blog Panoply (http://panoplyclassicsandanimation.blogspot.com/ )

10 notes

·

View notes

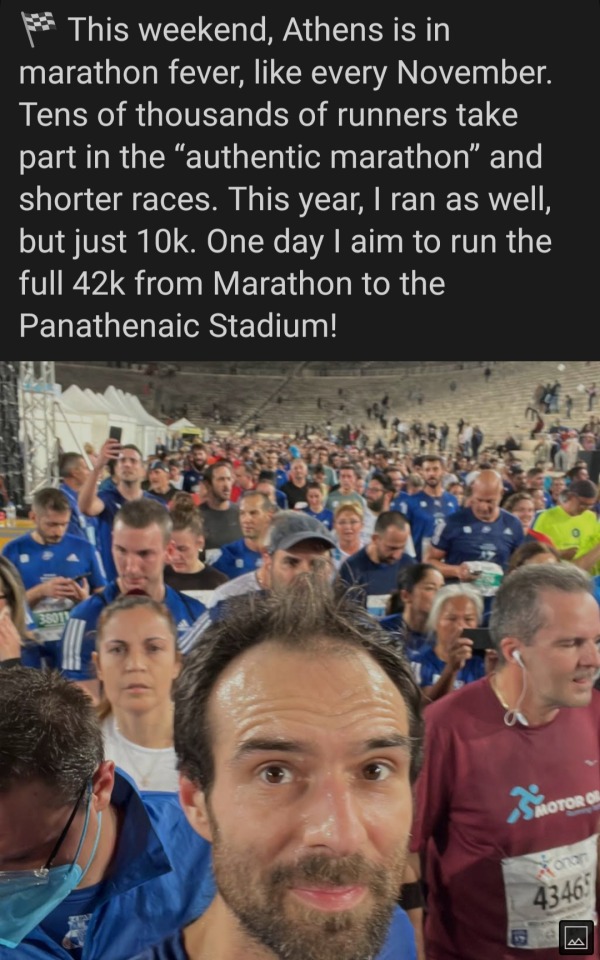

Text

November small marathon in Marathon, Athens! Photo by the YouTube channel EasyGreek

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nikolai had a power to turn bsd into gay porno if he put sex drug into those syringes he gave Dazai and Fyodor instead of poison

#man the potential#and Nikolai would do something like that in a heartbeat#idk where to even start with possible ships given who was there at that moment#sigzai#speed run of Sigma and Dazai getting to know each other#soukoku#chuuya broke into prison to get his lame ass bf out but got his bones jumped#fyolai#cuz Nikolai had everything planned out#fyoya#cuz why not#fyosig#battle over a gun and 'touch me if you dare' turn into something else#and ofc#fyozai#it'd be a marathon of they're both affected like talk about rivalry reaching climax in best way possible#bsd

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Marathon: The Helmet With the Soldier’s Skull Still Inside

This remarkable Corinthian-style helmet from the Battle of Marathon was reputedly found in 1834 with a human skull still inside.

It now forms part of the Royal Ontario Museum’s collections, but originally it was discovered by George Nugent-Grenville, who was the British High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands between 1832-35.

A keen antiquarian, Nugent-Grenville carried out a number of rudimentary archaeological excavations in Greece, one of which took place on the Plains of Marathon, where the helmet was uncovered.

A pivotal moment in Ancient Greek history, the battle of Marathon saw a smaller Greek force, mainly made up of Athenian troops, defeat an invading Persian army.

There were numerous casualties, and it appears that this helmet belonged to a Greek hoplite (soldier) who died during the fighting of the fierce and bloody battle.

The Athenian army under General Miltiades consisted almost entirely of hoplites in bronze armor, using primarily spears and large bronze shields. They fought in tight formations called phalanxes and literally slaughtered the lightly-clad Persian infantry in close combat.

The hoplite style of fighting would go on to epitomize ancient Greek warfare.

Today the helmet and associated skull can be viewed at the Royal Ontario Museum’s Gallery of Greece.

Battle of Marathon saved Western Civilization

It was in September of the year 490 BC when, just 42 kilometers (26 miles) outside of Athens, a vastly outnumbered army of brave soldiers saved their city from the invading Persian army in the Battle of Marathon.

But as the course of history shows, in the Battle of Marathon, they saved more than just their own city: they saved Athenian democracy itself, and consequently, protected the course of Western civilization.

According to historian Richard Billows and his well-researched book Marathon: How One Battle Changed Western Civilization, in one single day in 490 BC, the Athenian army under General Miltiades changed the course of civilization.

It is very unlikely that world civilization would be the same today if the Persians had defeated the Athenians at Marathon. The mighty army of Darius I would have conquered Athens and established Persian rule there, putting an end to the newborn Athenian democracy of Pericles.

In effect, this would certainly have destroyed the idea of democracy as it had developed in Athens at the time.

The Battle of Marathon lasted only two hours, ending with the Persian army breaking in panic toward their ships with the Athenians continuing to slay them as they fled.

In his book, however, Billows calls the Battle of Marathon a “miraculous victory” for the Greeks. The victory was not as easy as it is often portrayed by many historians. After all, the Persian army had never before been defeated.

By Tasos Kokkinidis.

#Battle of Marathon: The Helmet With the Soldier’s Skull Still Inside#greek helmet#persian army#general miltiades#king darius i#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#long reads

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

When a magnificent helmet was recovered from the ruins of the temple of Zeus researchers couldn't believe their eyes. It is very rare to find an item which belonged to a famous hero of the ancient Greek battlefields. The offering he brought to the temple centuries ago made his name known once again.

#Miltiades#helmet#warrior#greece#battle#Marathon#Olympia#Zeus#offering#Callimachus#Persia#ancient#history#ancient origins

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

How has our online marathon been going??

Welp, we're down to ONE WEEK LEFT OF ONLINE SERVICE...

AND TONIGHT!!! As per result of our poll on YT, @pikakoopa and I will start playing KID ICARUS, if we can get 2 more players... KIRBY BATTLE ROYALE! , and a classic SUPER SMASH BROS for WiiU... (3DS version is poopy).

It will be multiple parts! So if you miss tonight, you can have a chance tomorrow! Just sit back and watch us beat each other up!!!!!

#havent been able to share streams as soon as they go up cuz my time is so short between them. but theres enough to at least get them started#nintendo 3ds#nintendo#wiiu#3ds#wii u#april 8 2024#april 8#livestream#live#youtube#marathon#online service#online#multiplayer#nintendo network#kid icarus#kid icarus uprising#kirby battle royale#uprising#super smash bros#smash bros#kirby

7 notes

·

View notes

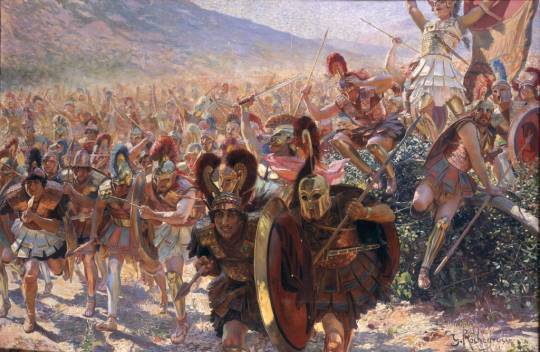

Text

Les Héros de Marathon (The Heroes of Marathon) by Georges Rochegrosse

Greek troops rushing forward at the Battle of Marathon 490 BC

#battle of marathon#athens#plataea#art#georges rochegrosse#history#athenians#achaemenid empire#persian#invasion#antiquity#ancient greece#greece#ancient greek#ancient#greek#europe#european#heroes#troops#soldiers#battle#war#marathon#art nouveau

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

You mean you can watch something without becoming immediately obsessed with the characters and symbolism?

#anyway i thought the people shipping bilbo and thorin were out of left field but like#did you notice how they did bilbo and thorin right alongside kili and tauriel? you cannot look me in the eye after that and say that bilbo#wasnt at least a LITTLE in love with him. in the way you love a close friend. or someone you look up to and admire#bc bilbo followed that man into battle. several times. and i think that devotion is something akin to love#also i am being unwell abt golem and frodo being character foils#esp considering we’re planning a lotr marathon at some point#and can i just say. i do appreciate that in absence of gandalf bilbo is ALWAYS the voice of reason#mans is so unwilling to ignore his own moral compass for the majority of the series. (which is what also makes his attitude when it comes to#the ring that much more jarring)#anyway yeah so normal abt them :] <-lying#sev rambles#also i was trying so hard not to rant abt billionares and dragons being functionally the same thing. i only did once. considering one of my#moms friends were there you should be so proud of me for my self restraint

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Corinthian helmet found with the soldier’s skull still inside from the Battle of Marathon which took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece.

2,500 years ago, on the morning of September 12th, 10,000 Greek soldiers gathered on the plains of Marathon to fight…

#helmet#the Battle of Marathon#with the soldier's skull still inside#Greece#Persian invasion#Greek soldiers#Marathon#fight#museum#photo

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Greek scholar reviews “The Idea of Marathon” of Sonya Nevin

“The idea of Marathon: battle and culture

Sonya Nevin, The idea of Marathon: battle and culture. London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022. Pp. 256. ISBN 9781788314206

Review by

Manolis Petrakis, Directorate of the National Archive of Monuments, National Archaeological Museum of Athens. [email protected]

Preview

This reader-friendly book provides more than it claims. It offers a handy overview of (Athenocentric) ancient Greek history and historiography from the 6th century BCE to its ancient and modern reception, focusing on the Battle of Marathon. The twelve chapters are preceded by a brief Introduction, where the author sets the stage at the twilight of the Persian Wars, elaborates on the influence of the name “Marathon”, and sets the book’s goals, namely, to explore the circumstances that led to the battle, the battle itself, and its cultural influence. Next, Nevin briefly introduces Greek historiography, (not surprisingly) highlighting Herodotus as the primary source of evidence—for herself as well as others—along with other literary texts, archaeological finds, and inscriptions.

The first five chapters are devoted to the events that led to the battle and to introductory information on Greece and Persia before the war. Chapter 1, “Athenians at a Turning Point”, offers an overview of Athens before the Persian Wars. First, the author emphasizes the changes of regime from oligarchy to tyranny to the shaping of democracy. She then draws attention to the elite families of the city and their role in politics. Finally, the chapter closes with general information on the Greek military, especially the hoplites.

Chapter 2, “The Greek World”, moves swiftly from Athens to Sparta, Boeotia, and Asia Minor. Nevin provides an excellent overview of Greek identity’s shared attributes during the Archaic Period, namely origin, language, customs, and religion. The interaction of the other Greek cities and areas with Athens is thoroughly explored. Especially in the case of Ionia, relations between Greeks and non-Greeks are discussed. The chapter ends with the Persians in Ionia, an ideal way to smoothly transition to the third chapter.

Chapter 3, “Persia”, discusses the Persian Empire, providing the historical context of its creation and expansion. It deals with various subjects, such as Persian identity, cultural characteristics, and economy. In addition to the historical overview and the presentation of crucial personalities, Nevin analyses Persian weaponry, drawing comparisons between the Greek and Persian militaries. The author handles her source material with care, also drawing from Persian evidence, which is important given that “we are disproportionately dependent on Greek sources” (p. 33), as she rightly points out.

Chapter 4, “Revolt in Ionia”, explores the events and the cause of the Greek-Persian Wars, stressing the importance of the Ionian Revolution. Nevin takes a fresh look at how Darius’ shifting from his predecessors’ manner of governing triggered the Revolt. She demonstrates how Aristagoras’ unfortunate attempt to take over Naxos in favor of Persia resulted in Miletus’ revolt against Persian authority. She then provides an overview of the formation of the Ionian League and the Ionian Revolt itself. Nevin uses some archaeological finds, in addition to the historical sources, “as evidence of siege [that] can be seen in the archaeology of Paphos” (p. 57), referring to a Persian siege of Cyprus, but unfortunately does not cite her archaeological sources, a practice which is not helpful for convincing the reader. This is a problem throughout the book.

Chapter 5, “The Plain of Marathon”, primarily deals with Hippias, Datis, Artaphernes, and Miltiades, while only two pages discuss the plain (p. 69–70). Some basic information on the topography of the Marathon plateau is given. Note 14 cites some of the main publications on the subject, but the omission of Dionysopoulos’ monograph is a serious one,[1] as many topographical issues have been reconsidered since the most recent publication mentioned, that of van der Veer in 1982.[2]

The following two chapters pursue the battle and the events immediately after it. In Chapter 6, “The Fight”, after briefly discussing the mythical stories of gods and heroes who contributed to the fight, Nevin presents the various theories and interpretations of the battle formations and the role of the Persian cavalry. The narrative continues to follow Herodotus, as does the whole book, but especially here more space given to modern scholarship. This chapter is a good sample of the author’s excellent knowledge of the subject and her critical approach to literary texts, as she challenges the sources, e.g., on the numbers of combatants, and she also notes possible anachronisms.

Chapter 7, “Surviving Marathon” continues this inquiry, examining the events immediately after the battle. Nevin convincingly characterizes as symbolic the Athenian army’s two visits to sanctuaries of Heracles on its way home. She investigates the original Marathon road, concluding that we must not rely on the details that could be fictional. The author continues with the treatment of the wounded and a brief note on the spoils, which either benefited the Athenian treasury or became offerings to the gods. Alongside Miltiades’s helmet, a reference to a second helmet dedication, taken as booty, is omitted.[3] The chapter concludes with the treatment of the dead. In respect to the tumulus, we shall note that Antonaccio first stated the idea that it was adapted from an earlier tomb.[4] Also, a mention of the cenotaph at Kerameikos would have been welcome.[5]

In the remaining five chapters, Nevin investigates the battle’s impact from antiquity to modern times. Chapter 8, “Events after Marathon”, touches on numerous topics in a few pages. First, the author explores the effects of this battle on the Persian Empire, concluding that they were insignificant. Then she proceeds with the significance of Marathon in shaping Athenian identity, concluding that this battle eventually became its cornerstone. Next, the author presents an overview of the commemorative monuments and of festivals established in honour of the event. She continues with Miltiades’ decline and death to the formation of the Delian League. Finally, the chapter closes with Aeschylus’ Persians; Nevin shows that this tragedy signifies the beginning of the process of shaping Greek (Athenian) identity through reference to the Persian Wars.

In the first part of Chapter 9, “Memories of Marathon in Fifth-Century Art and Literature”, she stresses the importance of the Athenian Treasury and other Cimonian monuments at Delphi. Again, only Pausanias is mentioned, although the monuments themselves have been excavated and published.[6] She proceeds with more discussion of material culture, the Stoa Poikile, pottery, and the Temple of Nemesis. The chapter closes with an examination of historiography and theatrical plays.

Chapter 10, “Marathon beyond the Fifth Century”, surveys the presence of the battle in the oratorical speeches, philosophy, and historiography from the 4th to the 2nd centuries BCE. The author shows how Athenian rhetoric and propaganda kept using the battle in various circumstances. Conversely, she demonstrates how and why Alexander did not use Marathon in his symbolic anti-Persian gestures. This chapter offers a summarized overview of Greek history; it deals more with the Greek-Persian Wars’ impact in general rather than Marathon in particular.

Chapter 11, “Marathon under Rome”, proceeds from the Hellenistic to the Roman Imperial Period. After discussing relevant passages from Pausanias, Lucian, and especially Plutarch, Nevin convincingly concludes that these authors did not emphasize who fought (as was the case in Classical/Hellenistic Athens) but rather the virtues connected with the battle.

Chapter 12, “Marathon after Antiquity”, brings together much interesting material. It opens with an 11th century CE Persian epic, Wamiq u ‘Adrha, which follows Miltiades’ son, Mentiochus. Then it outlines Marathon’s survey and excavation history, from the original antiquarian projects (Chandler, Fauvel, Leake) to the formal excavations (Schliemann, Philios, Stais). Probably Fink’s monograph deserved to be consulted here.[7] Finally, Nevin’s narrative reaches the modern era, with the development of the Soros into an archaeological site. More elaboration or a reference was needed on the long debate concerning the Soros’ identification as the Athenian Tumulus.[8] Next, the author notes the erection of the Marathon Archaeological Museum, for which a citation is also needed.[9] Nevin mentions the copy of the Aristion monument next to the Soros, but she fails to mention the marble replica of the Trophy set near its original site after Korres’ comprehensive study.[10] Finally, a book dealing with the reception of the Battle of Marathon would greatly benefit from a reference to the 1929 copy of the Athenian Treasury of Delphi, constructed by Ulen next to the Marathon Lake’s dam, and ideally a discussion of its symbolism.[11] Next, Nevin deals with Byron’s poetry and its resonance. A sub-chapter follows on 19th-century European youth’s classical education and an excellent overview of the modern Marathon run, demonstrating the influence that Browning’s poem may have had on its shaping. Again, a reference to the Marathon Run Museum is missed.[12] Then the author jumps to the use of Marathon in the propaganda of the military dictatorship in Greece and sketches the situation in 1930s Persia-Iran. The chapter ends by focusing on 21st-century novels on Marathon.

A short afterword sums ups the book conveniently, highlighting that “Marathon is also a story of how events are remembered” (p. 191). A concluding index, as well as opening lists of Illustrations and Abbreviations are provided.

Throughout the book, Nevin provides a helpful overview of Greek history, to which she incorporates the presence and the use of the Battle of Marathon. The structure is clear and easy to follow. Some translated ancient texts, mainly Herodotus, contained in the text are useful to the reader, and translations are generally accurate. The book is also commendably readable and virtually without misprints (exceptions: p. 19 Aeolians from Aeolus, not Aeolis, p. 131 Acharnians, not Acharnanians) or inconsistencies (the three citations to Inscriptiones Graecae are inconsistent p. 205 note 13: IG I31472; on the same page note 28: IG ii 1.47I and on page 209 note 46: IG I3 435). In contrast, the publisher did not pay attention to the quality of the few illustrations (11): the line drawings are faint, the legends on the maps are barely readable, and the only vase photograph (fig. 11) does not meet publication standards.

My main criticism of this volume would be its limited bibliography and the scarcity of references or citations within the body of the text, as has already been noted above. Be this as it may, Nevin offers readers many interesting observations that provide much food for thought. There are a few inaccuracies/overgeneralizations, e.g. (p. 6) the Panathenaea (from the context we get the Great Panathenaea) are mentioned as an annual festival, while they were in fact celebrated every four years (as opposed to the Lesser Panathenaea, which were annual) or (p. 65) the modern Marathon Run is not from east to west Attica, but central, still closer to the east.

The writing style is by no means academic, yet it is graceful. Accumulations of excessively short sentences (e.g., p. 86: “Narrow paths. Soft soil. Water. Plants. Panicked men.”) and informal vocabulary (e.g., p. 6 “‘Tyrant’ was not a dirty word”, [on Corinthian helmets] “they looked fantastic”, [on Spartans] “They were not super-soldiers”, “smaller players Plataea, Thespiae and Tanagra”, “Mission on”, “Fantastic sass”, etc.) show that the book targets a larger audience than just fellow classicists. That probably explains the scarcity of secondary sources. Given the intended readership, most of the issues mentioned above are also irrelevant; Nevin’s writing could be nothing but successful in attracting non-specialists. The book is straightforward to read and offers a short, concise, and informative overview of the Greek-Persian Wars and their reception. It therefore represents a welcome addition to the vast bibliography on Marathon and ancient history in general. Newcomers to the study of classics, undergraduates, or interested members of the public looking for an overview of the Battle of Marathon will find this volume very useful.

Bibliography

Antonaccio, C.A. 1995. An Achaeology of Ancestors. Tomb Cult and Hero Cult in Early Greece. Lanham.

Dionysopoulos, Ch.D. 2015. The Battle of Marathon. A Historical and Topographical Approach. Athens.

Fink, D.L. 2014. The Battle of Marathon in Scholarship. Research, Theories and Controversies since 1850. Jefferson, North Carolina.

Korres, M. 2017. “Το Τρόπαιον Του Μαραθώνος. Αρχιτεκτονική Τεκμηρίωση.” In Giornata Di Studi in Ricordo Di Luigi Beschi / Ημερίδα Εις Μνήμην Του Luigi Beschi: Italiano, Filelleno, Studioso Internazionale. Atti Della Giornata Di Studi, Atene 28 Novembre 2015, edited by E. Greco, 149–202. Tripodes 17. Atene.

Petrakos, V. 1996. Marathon. Athens.

Raubitschek, A.E. 1940. “Two Monuments Erected after the Victory of Marathon.” American Journal of Archaeology 44 (1):53–9. doi:10.2307/499590.

Robinson, B.A. 2013. “Hydraulic Euergetism. American Archaeology and Waterworks in Early-20th-Century Greece.” Hesperia 82 (1):101–30. doi:10.2972/hesperia.82.1.0101.

Scott, M. 2010. Delphi and Olympia. The Spatial Politics of Panhellenism in the Archaic and Classical Periods. Cambridge; New York.

Steinhauer, G. 2009. Marathon and the Archaeological Museum. Athens.

Valavanis, P. 2010. “Σκέψεις Ως Προς Τις Ταφικές Πρακτικές Για Τους Νεκρούς Της Μάχης Του Μαραθώνος.” In Marathon. The Battle and the Ancient Deme, edited by K. Bouraselis and K. Meidani, 73–98. Athens.

———. 2019. “What Stood on Top of the Marathon Trophy.” In From Hippias to Kallias. Greek Art in Athens and Beyond. 527-449 B.C., edited by O. Palagia and E. Sioumpara, 145–56. Athens.

van der Veer, J.A.G. 1982. “The Battle of Marathon: A Topographical Survey.” Mnemosyne 35 (3):290–321.

Notes

[1] Dionysopoulos 2015.

[2] van der Veer 1982.

[3] Museum of Olympia no. B 5100.

[4] Antonaccio 1995, 118–9.

[5] Raubitschek 1940.

[6] See Scott 2010, 77–81 with previous bibliography.

[7] Fink 2014.

[8] For the debate see Valavanis 2010, 73–98.

[9] Petrakos 1996; Steinhauer 2009.

[10] Korres 2017; Valavanis 2019 with previous bibliography.

[11] Robinson 2013.

[12] https://marathonrunmuseum.com/en/.”

Source: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2023/2023.01.09/

Manolis Petrakis

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Wait if Scourge is there when Breezepelt kills Fire then how does the little punk still LIVE. Scourge doesn't take that shit lightly. Also the image of Scourge gutting Breeze or even Onestar is kinda satisfying tbh but I don't really like either of them so. Please tell me Scourge at least scares the crap out of one of them after Fire's death, please.

Scourge is WRECKED when Firestar dies, and WOULD have sworn revenge, but he wouldn't dare disrespect his memory like that. He swore to abide by the Warrior Code while in Clan territory and abides by it undauntingly.

Not out of respect to the law obviously, but because Firestar hosts him on his own honor. So he would never shame his legacy.

Lucky for Breeze, he's also not known as the killer until after OotS when Scourge is dead. But there's plenty of opportunity for him to have a satisfying beatdown of one of the WindClan boys in the meantime.

#Also to prevent too many curbstomp battles Scourge is getting a couple nerfs#For one he's getting older and may have low blood sugar#He can't run marathon battles anymore but he can still delete a warrior twice his size when he's fresh#Bonefall Rewrite

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The F@tT Fic Marathon: 41-60

*says he'll be back at the end of the week because the beginning is very busy. reads a full 20 anyway* WELL. anyways, I have proven to myself that the fake-dating trope just does not work for me.

other fun details: all of these fics, with the exception of a cross-season ficlet anthology are set in Hieron, likely because i'm in the early 2017 fics, and winter in hieron was in full swing at this point

moth to the flame/pray for guidance by confidencealive (dazzler) - short, but I really enjoyed the comparison this fic drew between Ephrim and Hadrian both struggling with faith. and also naming it after their moves

Fall on Your Knees by Hierodule - the summary sells this as a fic about Hella and Hadrian's friendship, but imo it's just as much if not more about Rosana. or is at least half about Rosana and her frustrations and resilience as a wife left behind, and also she and Emmanuel bond. i liked it!

Always So Loud by SHAYCH___xxvii - the last smut I recommended because it was extremely funny. I am recommending this on pure pornographic value. hella is sexy. goodbye.

words read: 47,457 (115,876 total)

works remaining: 1840

next reading list: page 92 of the ao3 tag if you sort by Date Posted

#fatt fic marathon#arwainian princessoid decrees#friends at the table#jamie james my friend if you are seeing this don't check out the first two you may get spoiled#the internal battle i had to wage about whether or not to recommend that pwp? intense. i am smacking my protestant shame with a hammer

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

no fucking way there's a new marathon game coming and it's gonna be a PvP eSports FPS. my day was literally made then subsequently ruined into oblivion in an instant

#bet they'll have a battle pass and live service hype buffoons too#old ridge yells at cloud#marathon

9 notes

·

View notes