#battle of plataea

Text

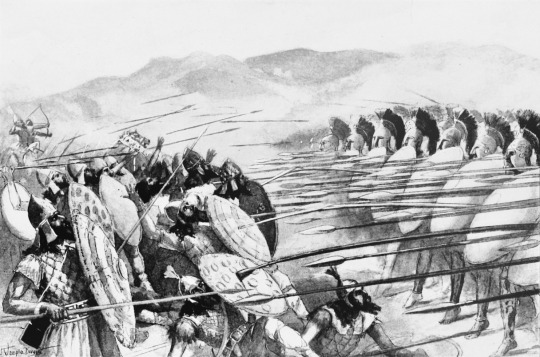

The Spartans at the Battle of Plataea by Edward Ollier for Cassell's 1890 "Illustrated Universal History."

#spartans#spartan#plataea#battle of plataea#art#history#ancient greece#greece#ancient greek#greek#phalanx#europe#european#achaemenid empire#persia#persian#invasion#battle#edward ollier#illustration#aristodemus

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The meal after the victorious battle of Plataea

According to Herodotus, the historian who described the Greek-Persian wars in detail, when the Spartan Commander-in-Chief Pausanias, after the victorious battle of Plataea, entered the scene of the killed Persian General Mardonius:

"... he ordered the bakers and the cooks to prepare the dinner Mardonius usually enjoyed. When Pausanias saw the luxurius daybeds, as well as the gold and silver tables loaded with the majestic dinner, he was surprised. As a joke, he ordered his own servants to prepare a Spartan dinner. The difference was so great that he laughed, called all the Generals of the Greeks and said to them, pointing to the two dinners: "Greeks, I called you here to show you the foolishness of the Median ruler who dines like this everyday and moved against us to steal our poverty."

We know today many nutritional details of the above scene, namely that the Greek General's meal did not stand out from the hoplites battling under his command. The ration was based on barley bulgur and unleavened barley bread, olives preserved in brine, onions and cured fish wrapped in fig leaves. In his haversack every soldier had salt and thyme to flavor the food, dried figs and a small spit perhaps, for the rare occasion that he would find meat. The army's logistics provided also goat cheese, fresh fruit (figs and grapes in the case of the Battle of Plataea, which took place in late August) and wine diluted with water to give courage to the fighters.

The Persians, who, in their vast and multinational troops, served Greeks, Indians and Ethiopians, were supplied by their Theban allies. They also ate barley bread, along with some goat meat, dried dates and almonds. However, the pyramidal structure of the Persian army required Mardonius and his high rank officers to enjoy roasted ducks and peacocks, pilaf flavored with cardamom, honey dripping sweets, wine made from dates and strong barley beer.”

Source: https://olyrafoods.com/blogs/wisdom-treats-blog/the-meal-after-the-victorious-battle-of-plataea

Olyra is the site of a Greek businessman who makes alimentary products inspired by the ancient Greek diet. The information he provides about the culinary habits of ancient Greeks and Persians when these peoples campaigned seems trustworthy.

I remind here that the question of the motivation of the Persian attempt to conquer Greece is a complex one in Herodotus. But the story reported here illustrates well the theme of the imperial hybris, i.e., of the desire of empires and elites which have already too much to acquire even more through further conquest and expansion.

I remind also that this report is not a simplistic illustration by Herodotus of some cliché of “Oriental decadence”, as Mardonius is portrayed in the Histories as aggressive and prideful, but also as competent and brave.

And of course the tragic irony of the same story is that Pausanias, the victor of Plataea and savior of the Greek freedom, the defender of the austere Greek way of life face to the Persian culinary luxury, not only adopted some time later the lavish lifestyle of the Persian nobility, but he was even accused of plotting with Xerxes for the subjugation of Greece and was put to death for this reason by the Spartans - through starvation...

Bust of Pausanias, in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

The Falcata & Kopis are one of my favorite 🗡's

I'm lucky to have been able to get sponsored to attend the 2500th Anniversary of the Battle of Plataea!💪🏿

Greece is still one of my most epic adventures to date!⚔️

On my way home, I got to attend a fun shoot too!📷

#Kult of Athena#KultOfAthena#Simply Samurai#SimplySamurai#Seto Waddell#Spencer Waddell#sword#swords#weapon#weapons#blade#blades#Falcata#Kopis#Hoplite#Greece#Battle of Plataea#Instagram#videos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite Sparta’s reputation for superior fighting, Spartan armies were as likely to lose battles as to win them, especially against peer opponents such as other Greek city-states. Sparta defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War—but only by accepting Persian money to do it, reopening the door to Persian influence in the Aegean, which Greek victories at Plataea and Salamis nearly a century early had closed. Famous Spartan victories at Plataea and Mantinea were matched by consequential defeats at Pylos, Arginusae, and ultimately Leuctra. That last defeat at Leuctra, delivered by Thebes a mere 33 years after Sparta’s triumph over Athens, broke the back of Spartan power permanently, reducing Sparta to the status of a second-class power from which it never recovered.

Sparta was one of the largest Greek city-states in the classical period, yet it struggled to achieve meaningful political objectives; the result of Spartan arms abroad was mostly failure. Sparta was particularly poor at logistics; while Athens could maintain armies across the Eastern Mediterranean, Sparta repeatedly struggled to keep an army in the field even within Greece. Indeed, Sparta spent the entirety of the initial phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), failing to solve the basic logistical problem of operating long term in Attica, less than 150 miles overland from Sparta and just a few days on foot from the nearest friendly major port and market, Corinth.

The Spartans were at best tactically and strategically uncreative. Tactically, Sparta employed the phalanx, a close-order shield and spear formation. But while elements of the hoplite phalanx are often presented in popular culture as uniquely Spartan, the formation and its equipment were common among the Greeks from at least the early fifth century, if not earlier. And beyond the phalanx, the Spartans were not innovators, slow to experiment with new tactics, combined arms, and naval operations. Instead, Spartan leaders consistently tried to solve their military problems with pitched hoplite battles. Spartan efforts to compel friendship by hoplite battle were particularly unsuccessful, as with the failed Spartan efforts to compel Corinth to rejoin the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League by force during the Corinthian War.

Sparta’s military mediocrity seems inexplicable given the city-state’s popular reputation as a highly militarized society, but modern scholarship has shown that this, too, is mostly a mirage. The agoge, Sparta’s rearing system for citizen boys, frequently represented in popular culture as akin to an intense military bootcamp, in fact included no arms training or military drills and was primarily designed to instill obedience and conformity rather than skill at arms or tactics. In order to instill that obedience, the older boys were encouraged to police the younger boys with violence, with the result that even in adulthood Spartan citizens were liable to settle disputes with their fists, a tendency that predictably made them poor diplomats.

But while Sparta’s military performance was merely mediocre, no better or worse than its Greek neighbors, Spartan politics makes it an exceptionally bad example for citizens or soldiers in a modern free society. Modern scholars continue to debate the degree to which ancient Sparta exercised a unique tyranny of the state over the lives of individual Spartan citizens. However, the Spartan citizenry represented only a tiny minority of people in Sparta, likely never more than 15 percent, including women of citizen status (who could not vote or hold office). Instead, the vast majority of people in Sparta, between 65 and 85 percent, were enslaved helots. (The remainder of the population was confined to Sparta’s bewildering array of noncitizen underclasses.) The figure is staggering, far higher than any other ancient Mediterranean state or, for instance, the antebellum American South, rightly termed a slave society with a third of its people enslaved.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Corinthian helmet found with the soldier's skull still inside from the Battle of Marathon which took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece.

2,500 years ago, on the morning of September 12th, 10,000 Greek soldiers gathered on the plains of Marathon to fight the invading Persian army. The Greek soldiers were composed mostly of citizens from Athens as well as some reinforcements from Plataea. The Persian army had 25,000 infantrymen and 1,000 cavalry.

According to legend, a long-distance messenger by the name of Phidippides was sent to Athens shortly after the battle to relay the news of victory. It has been said that he ran the entire distance from Marathon to Athens, a distance of approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi), without stopping, and bursted into the assembly to declare, "We have won!", before collapsing and dying. This story differs quite a bit from Herodotus' account which mentions Phidippides as the messenger who ran from Athens to Sparta, and then back, covering a total distance of 240 km (150 mi) each way.

#history#sparta#spartan#this is sparta#persia#Greece#war#battle#lonely planet#vibes#good vibes#lifestyle#style#aes#aesthetic#aesthetics#helmet

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Much of this tendency to imagine U.S. soldiers as Spartan warriors comes from Steven Pressfield’s historical fiction novel Gates of Fire, still regularly assigned in military reading lists. The book presents the Spartans as superior warriors from an ultra-militarized society bravely defending freedom (against an ethnically foreign “other,” a feature drawn out more explicitly in the comic and later film 300). Sparta in this vision is a radically egalitarian society predicated on the cultivation of manly martial virtues. Yet this image of Sparta is almost entirely wrong. Spartan society was singularly unworthy of emulation or praise, especially in a democratic society.

To start with, the Spartan reputation for military excellence turns out to be, on closer inspection, mostly a mirage. Despite Sparta’s reputation for superior fighting, Spartan armies were as likely to lose battles as to win them, especially against peer opponents such as other Greek city-states. Sparta defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War—but only by accepting Persian money to do it, reopening the door to Persian influence in the Aegean, which Greek victories at Plataea and Salamis nearly a century early had closed. Famous Spartan victories at Plataea and Mantinea were matched by consequential defeats at Pylos, Arginusae, and ultimately Leuctra. That last defeat at Leuctra, delivered by Thebes a mere 33 years after Sparta’s triumph over Athens, broke the back of Spartan power permanently, reducing Sparta to the status of a second-class power from which it never recovered.

Sparta was one of the largest Greek city-states in the classical period, yet it struggled to achieve meaningful political objectives; the result of Spartan arms abroad was mostly failure. Sparta was particularly poor at logistics; while Athens could maintain armies across the Eastern Mediterranean, Sparta repeatedly struggled to keep an army in the field even within Greece. Indeed, Sparta spent the entirety of the initial phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), failing to solve the basic logistical problem of operating long term in Attica, less than 150 miles overland from Sparta and just a few days on foot from the nearest friendly major port and market, Corinth.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

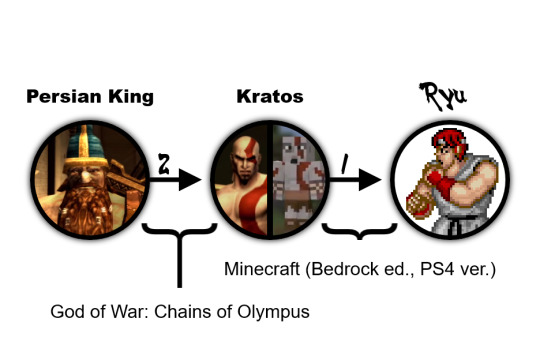

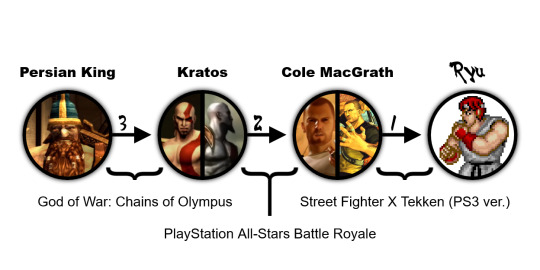

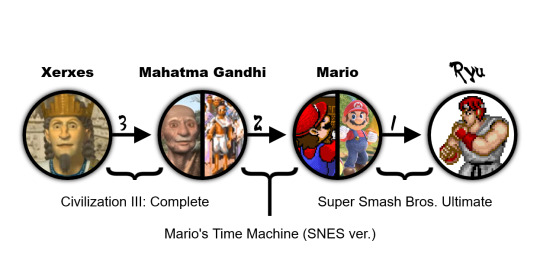

Ryu Number: Xerxes I

Xerxes I, also known as Xerxes the Great, was the ruler of the Achaemenid Empire from 486 BCE until his assassination in 465 BCE. At the time of his ascension to the throne, the Achaemenid Empire ran from the eastern end what's now Pakistan to the west end of what's now Turkey. You might notice that that's about the same amount of empire in about the same location as Alexander the Great had—that's because Alexander the Great was the guy who took over the Achaemenid Empire and made it not-so-Achaemenid anymore.

It was awful big, is what I'm saying.

But let's be honest: You probably know Xerxes I better as the Bad Guy with the nose ring in that one weird Spartan hagiography Gerald Butler was in. Fugging Miller.

Anyway, Xerxes I almost certainly has a Ryu Number of 2, and definitely not a Ryu Number more than 3, but there's some stuff.

The problem with finding a Ryu Number of Xerxes I is that 5th-century-BCE Persian monarchs don't show up in video games that often, for some reason. He makes a historical appearance in the Assassin's Creed Odyssey DLC Legacy of the First Blade...

...but unfortunately, Odyssey takes place too far after the times of myth and legend for anyone big enough to be a Minecraft skin in Greek-mythology-inspired DLC to show up.

It doesn't help, either, that in Assassin's Creed lore, all the "gods" were just members of a Precursor Race pretending to be gods, a la Stargate. No, that's not "Hera," that's a jerk Precursor Person who's taken on the identity of "Hera," all the better to lead mankind around like a clowder of schmucks. She's pretending to be Norse elsewhere. Don't fall for it.

(There's also A Minotaur, which feels like it ought to connect via that Minecraft skin pack, but if I'm understanding the Odyssey lore correctly—and I very well might not be; holler at me—the minotaur the player encounters isn't actually the Minotaur from the myth we know and love, but some random other guy who subsequently got his hands on the Precursor Technology that turns you into a minotaur. Yeah, everything is Precursor People in Assassin's Creed. It's kind of disappointing.)

Of course, you can still get to Xerxes through Odyssey if you want to—a handful of historical characters who don't have Minecraft skins show up—but you'll need an extra step. And if we're going to have an extra step anyway, I'm going to go for the route that doesn't need Assassin's Creed, partially because I haven't played the games yet but mostly because I'm still really disappointed about the Precursor People thing.

Which means, unfortunately, it's back to Miller.

I'll say this: For all that 300: March to Glory is Not A Very Good Video Game, it left me the impression that someone behind the scenes actually did the bare minimum research into the Greco-Persian Wars. Persian commanders Hydarnes and Mardonius make appearances (if only to provide something unique to hit), and Mardonius even survives the movie-equivalent events of the game until an epilogic, post-movie level that takes place during the Battle of Plataea—which is, indeed, where the historical Mardonius bit it. It's not much, but I had to watch the whole dang thing, so I'll take what I can get. Gets me more names for The Chart, besides.

As for connecting this game to Ryu, you can, of course, count on the Ol' Dependable of Games With Historical Figures:

...Or maybe you're not a fan of Anime And Things That Look Like Anime, in which case, try this, instead:

I'm not sure I can explain how weird Spartan: Total Warrior is—by which I'm referring to its existence more than anything in the game itself, though the content's pretty weird, too. For context, Total War is a series of strategy games featuring a combination of turn-based strategy, resource management, and real-time tactical control (so sayeth Wikipedia). There are a coupla Warhammer entries in the franchise, sure, but the vast majority of the games focus on real, historical campaigns and factions.

Spartan: Total Warrior, on the other hand, is a hack-and-slash that took one look at a history book and immediately took a pair of shears to it. The story starts in 300 BCE: The Roman Empire, led by Emperor Tiberius, has conquered almost the whole of Greece, with only Sparta remaining, and Leonidas leads his men into battle to oppose him. Later, the Romans reveal a superweapon powered by the imprisoned Medusa. Sejanus, Tiberius' right-hand man, is a powerful necromancer who kills and resurrects Castor's brother Pollux. One mission involves protecting Archimedes, leader of the Athenian resistance, from assassination.

To quote someone on Discord, this is a game supposedly set circa 300 BCE that "has one side led by a king who died 200 years before, and the other by an emperor who reigned 300 years after (never mind the fact that Rome was still a senatorial republic)." If you forced a too-serious historian to play this game they'd end up on the floor in a frothing heap of rage and/or despair (actually, someone should totally do that; I want to see the Greco-Roman history version of Jonathan Ferguson having to analyze the firearms of Team Fortress 2).

Oh yeah and Beowulf is there.

At some point you've got to appreciate—no, admire, even—the Xena:-Warrior-Princess-level decision to just Don't Worry About It.

And now that we have finished with the indisputable, let us proceed with the first of the hinky. Which is to say: Let's look at God of War: Chains of Olympus.

Chains of Olympus begins with an attack by the Persian navy on the Greek Attic peninsula (where Athens is, incidentally). The opening sequence features (among a whole lot of faceless Persian mooks) this prone-ish fella, who doesn't quite get to operating a ballista, irresponsibly leaving the work for Kratos instead.

(Credit: Migeman)

Inspecting the body after all the local ruckus is over identifies him as "Eurybiades," the "leader of the Athenian army."

Eurybiades was—according to historical record—a real person, though God of War doesn't exactly nail it on the head. Herodotus (who historians depend on more due to him being one of a Very Small Number of sources rather than anything to do with actual reliability) names Eurybiades as a Spartan who, during the second Persian invasion of Greece, was given command of the Greek navy due to some political whatuppery (the Spartans said that if a Spartan didn't lead it they'd be Awfully Uncooperative).

Following this bit, Kratos confronts the King of Persia (identity unspecified), who is apparently personally leading the invasion himself, which seems dumb but was apparently the norm back in those days. I bet we'd have a lot less wars if we made our Presidents actually serve on the front lines whenever they started feeling belligerent.

(Credit: Ibid.)

Anyway, Kratos kills the King of Persia, because if the King of Persia killed Kratos the game would be a lot shorter. Now, there's no watertight confirmation that this is the second Persian invasion—the first one also featured attempted Persian inroads into Attica, and was recent enough that it's not inconceivable for Eurybiades to have shown up, there, too—but if this is the second Persian invasion, and that is the King of Persia that was King of Persia during the second Persian invasion, then that King of Persia is Xerxes I.

And now, I think, you peer up at me, gaze beseeching. "But KC," you say, anxious and afraid, "Xerxes I didn't die during his invasion of Greece! After Greek victory at the Battle of Salamis, Persian forces were forced to withdraw from Attica, including Xerxes I himself, after which he focused on lavish construction projects until he was assassinated fifteen years later for unrelated reasons! He didn't die in the Greco-Persian Wars at all!"

To which I say: You know who else didn't die in the Greco-Persian Wars? Eurybiades. And you know who definitely didn't die in a fit of paranoid, obsessive overwork in the heart of a monumental statue of Apollo on the isle of Delos?

What I'm saying here is that God of War's relationship with historicality is fleeting at best, so maybe Don't Worry About It here, too.

(Incidentally, if it's the first Persian invasion of Greece that Kratos is mucking around in, then that king is actually Darius the Great, who also didn't die in Greece in real life. Darius is in Civilization V, though, so getting his Ryu Number is a lot easier.)

And speaking of Civilization, I've finally come to the shortest route I've found that, for all its likeliness, isn't as definite as I'd like, which is why I've saved it for last. You know how Civilization works, I think—you play a historical civilization (with a historical leader to match), and go up against other historical civilizations with their leaders. Like Darius, just now—he's your leader if you decide to play as the Persians.

Civilization III is like that...but unfortunately not as much like that as a fellow'd prefer. Sure, it's got its civilizations and leaders...

...But there's the occasional glaring unspecificity that's apparently there to make life difficult for me in particular. Yeah, sure, Montezuma here is most likely the second one—the one everyone knows, the one that had the real bad experience with Spain—but are you sure he isn't the first one instead? Like, absolutely sure? The instruction manual doesn't say, you know. How sure are you? Sure enough to bet a dollar? Two dollars? Fifty dollars? Your firstborn child? Why would I want your firstborn child, anyway? I don't want to look after a child; that's literally more work for me.

The Persian civilization exhibits the same problem here. Yeah, of course that's Xerxes I! If the team behind the game is picking out a historical figure named Xerxes to represent the Persians, it's got to be Xerxes I. But at the same time, there's technically nothing saying this isn't Xerxes II, a separate 5th-century-BCE Persian ruler of the Achaemenid Empire. I mean, it's terribly unlikely, seeing as Xerxes II ruled for 45 days before being killed by his half-brother, who ruled for six months before being killed by his half-brother, making him Not Exactly The Sort Of Individual You'd Put The Spotlight On, but Mahatma Gandhi and Joan of Arc are the leaders of Indian and French civilizations in this game, and that's weird, too. Gandhi was never the Prime Minister of India or anything like that, and Joan of Arc was a military leader, not a monarch.

Still, if you're willing to follow the reasonable assumption that the Xerxes here is Xerxes I, then the path that results is pretty dang optimal:

...If this is how you found out that Mahatma Gandhi is in Minecraft DLC, I'm sorry.

#ryu number#xerxes i#ryu#namco x capcom#minamoto no yoshitsune#fate/grand order#leonidas i#minecraft#minecraft (bedrock ed.)#ares#spartan: total warrior#minecraft (bedrock ed.#kratos#god of war: chains of olympus#street fighter x tekken#street fighter x tekken (PS3 ver.)#cole macgrath#playstation all-stars battle royale#mahatma gandhi#civilization iii: complete#super smash bros. ultimate#mario#mario's time machine#mario's time machine (SNES ver.)

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sparta

Sparta was one of the most important city-states in ancient Greece and was famous for its military prowess. The professional and well-trained Spartan hoplites with their distinctive red cloaks and long hair were probably the best and most feared fighters in Greece, fighting with distinction at key battles against the Persian army at Thermopylae and Plataea in the 5th century BCE.

Learn more about Sparta

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

September 22nd, 480 BC.

The Battle of Salamis

It was a naval battle fought between the alliance of Greek City-States under Themistocles of Athens & Eurybiades of Sparta, against the Persian Empire under Xerxes, in the Saronic Gulf.

After the betrayal of Ephialtes and the Greek defeat at the Battle of Thermopylae and subsequent retreat. The Greeks regrouped and under Athenian general Themistocles, were persuaded to bring the Persian fleet to battle once again.

The Persian Navy with a maximum estimated 1200 vessels, rowed into the Straits of Salamis. In the cramped conditions of the Straits, the great Persian numbers struggled to manoeuvre and became disorganised.

Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet numbering a maximum 378 vessels, scored a decisive victory. Xerxes retreated to Asia with much of his forces, leaving Mardonius one of his Generals, to complete the conquest of Greece.

However, the following year, the remainder of the Persian army was decisively beaten by the Greeks at the Battle of Plataea and at the Battle of Mykali.

The defeated Persians made no further attempts to conquer the Greek mainland.

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Athenian historian Thucydides once remarked that Sparta was so lacking in impressive temples or monuments that future generations who found the place deserted would struggle to believe it had ever been a great power. But even without physical monuments, the memory of Sparta is very much alive in the modern United States. In popular culture, Spartans star in film and feature as the protagonists of several of the largest video game franchises. The Spartan brand is used to promote obstacle races, fitness equipment, and firearms. Sparta has also become a political rallying cry, including by members of the extreme right who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Sparta is gone, but the glorification of Sparta—Spartaganda, as it were—is alive and well.

Even more concerning is the U.S. military’s love of all things Spartan. The U.S. Army, of course, has a Spartan Brigade (Motto: “Sparta Lives”) as well as a Task Force Spartan and Spartan Warrior exercises, while the Marine Corps conducts Spartan Trident littoral exercises—an odd choice given that the Spartans were famously very poor at littoral operations. Beyond this sort of official nomenclature, unofficial media regularly invites comparisons between U.S. service personnel and the Spartans as well.

Much of this tendency to imagine U.S. soldiers as Spartan warriors comes from Steven Pressfield’s historical fiction novel Gates of Fire, still regularly assigned in military reading lists. The book presents the Spartans as superior warriors from an ultra-militarized society bravely defending freedom (against an ethnically foreign “other,” a feature drawn out more explicitly in the comic and later film 300). Sparta in this vision is a radically egalitarian society predicated on the cultivation of manly martial virtues. Yet this image of Sparta is almost entirely wrong. Spartan society was singularly unworthy of emulation or praise, especially in a democratic society.

To start with, the Spartan reputation for military excellence turns out to be, on closer inspection, mostly a mirage. Despite Sparta’s reputation for superior fighting, Spartan armies were as likely to lose battles as to win them, especially against peer opponents such as other Greek city-states. Sparta defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War—but only by accepting Persian money to do it, reopening the door to Persian influence in the Aegean, which Greek victories at Plataea and Salamis nearly a century early had closed. Famous Spartan victories at Plataea and Mantinea were matched by consequential defeats at Pylos, Arginusae, and ultimately Leuctra. That last defeat at Leuctra, delivered by Thebes a mere 33 years after Sparta’s triumph over Athens, broke the back of Spartan power permanently, reducing Sparta to the status of a second-class power from which it never recovered.

Sparta was one of the largest Greek city-states in the classical period, yet it struggled to achieve meaningful political objectives; the result of Spartan arms abroad was mostly failure. Sparta was particularly poor at logistics; while Athens could maintain armies across the Eastern Mediterranean, Sparta repeatedly struggled to keep an army in the field even within Greece. Indeed, Sparta spent the entirety of the initial phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), failing to solve the basic logistical problem of operating long term in Attica, less than 150 miles overland from Sparta and just a few days on foot from the nearest friendly major port and market, Corinth.

The Spartans were at best tactically and strategically uncreative. Tactically, Sparta employed the phalanx, a close-order shield and spear formation. But while elements of the hoplite phalanx are often presented in popular culture as uniquely Spartan, the formation and its equipment were common among the Greeks from at least the early fifth century, if not earlier. And beyond the phalanx, the Spartans were not innovators, slow to experiment with new tactics, combined arms, and naval operations. Instead, Spartan leaders consistently tried to solve their military problems with pitched hoplite battles. Spartan efforts to compel friendship by hoplite battle were particularly unsuccessful, as with the failed Spartan efforts to compel Corinth to rejoin the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League by force during the Corinthian War.

Sparta’s military mediocrity seems inexplicable given the city-state’s popular reputation as a highly militarized society, but modern scholarship has shown that this, too, is mostly a mirage. The agoge, Sparta’s rearing system for citizen boys, frequently represented in popular culture as akin to an intense military bootcamp, in fact included no arms training or military drills and was primarily designed to instill obedience and conformity rather than skill at arms or tactics. In order to instill that obedience, the older boys were encouraged to police the younger boys with violence, with the result that even in adulthood Spartan citizens were liable to settle disputes with their fists, a tendency that predictably made them poor diplomats.

But while Sparta’s military performance was merely mediocre, no better or worse than its Greek neighbors, Spartan politics makes it an exceptionally bad example for citizens or soldiers in a modern free society. Modern scholars continue to debate the degree to which ancient Sparta exercised a unique tyranny of the state over the lives of individual Spartan citizens. However, the Spartan citizenry represented only a tiny minority of people in Sparta, likely never more than 15 percent, including women of citizen status (who could not vote or hold office). Instead, the vast majority of people in Sparta, between 65 and 85 percent, were enslaved helots. (The remainder of the population was confined to Sparta’s bewildering array of noncitizen underclasses.) The figure is staggering, far higher than any other ancient Mediterranean state or, for instance, the antebellum American South, rightly termed a slave society with a third of its people enslaved.

The ancient sources are effectively unanimous that the helots were the worst treated slaves in all of Greece; helotry was an institution that shocked the conscience of Athenian slaveholders. Critias, an Athenian collaborator with Sparta, was said to have quipped that it was in Sparta that “the free were most free and the slaves most a slave,” a staggering statement about a society that was mostly enslaved (and about Critias as a person that he thought this was praise). Plutarch reports the various ways that the Spartans humiliated and degraded the helots, while the Athenian orator Isocrates argued that it was a crime to murder enslaved people everywhere in Greece, except Sparta. Sparta, with both the most slaves per capita and the worst treated slaves, was likely the least free society in the whole of the ancient world.

Nor were the Spartans particularly good stewards of Greek freedom. While their place in popular culture, motivated by films such as 300, puts the Spartans at the head of efforts to defend Greek freedom from the expanding Persian Empire, Sparta was not always so averse to Persia. Unable to deal with the Athenian fleet itself, Sparta accepted Persian money during the Peloponnesian War to build its own, selling the Ionian Greeks back into Persian rule in exchange for humbling Athens. That war won the Spartans a brief hegemony in Greece, which they quickly squandered, ending up at war with their former allies in Corinth.

Unable to win that war either, Sparta again turned to Persia to enforce a peace, called the “King’s Peace,” which sold yet more Greek city-states to the Persian king in exchange for making Sparta into Persia’s local enforcer in Greece, tasked with preventing the emergence of larger Greek alliances that could challenge Persia. Far from being the defender of Greek independence, when given the chance the Spartans opened not only the windows but also the doors to Persian rule. They also refused to join in Alexander the Great’s expedition against Persia, for which Alexander mocked them by dedicating the spoils of his first victories “from all of the Greeks, except the Spartans.”

Instead of a society of freedom-defending super-warriors, Sparta is better understood as a place where the wealthiest class of landholder, the Spartans themselves, had succeeded in reducing the great majority of their poor compatriots to slavery and excluded the rest, called the perioikoi, from political participation or citizenship. The tiny minority of Spartan citizens derived their entire income from the labor of slaves, being legally barred from doing any productive work or engaging in commerce.

And rather than spending their time in ascetic military training, they spent their ample leisure time doing the full suite of expensive, aristocratic Greek pastimes: hunting (a pastime for the wealthy rather than a means of subsistence in the ancient world), eating amply, accumulating money, funding Olympic teams, breeding horses, and so on. Greek authors such as Xenophon and Plutarch continually insist that the golden age of Spartan austerity and egalitarianism existed in the distant past, but each author pushes that golden age further and further into that past, and in any event, archaeology tells us it was never so.

And that lavish lifestyle was clearly very important to the Spartans because they were willing to sacrifice all of their other ambitions on the altar to it. Beginning in the early 400s, the population of Spartan citizens, defined by being rich enough in land to make the mess contributions that were a key part of military and social lfie, began to decline as Spartan families used inheritance and marriage to consolidate holdings and increase their wealth, from 8,000 Spartan citizens in 480 B.C. to 3,500 in 418 to 2,500 in 394 to just 1,500 in 371. The collapse in the number of Spartans who qualified for citizenship had disastrous effects on the manpower available for the Spartan army, causing Sparta’s strategic ambitions to all crumble, one by one. Yet efforts by Agis IV (245-241 B.C.) and Cleomenes III (235-222 B.C.) to arrest the decline were foiled precisely because the Spartan political system denied any political voice to any but the leisured rich, who had little incentive to change.

Sparta is no inspiration for the leaders of a free state. Sparta was a prison in the guise of a state and added little to the sum of the human experience except suffering. No American, much less any U.S. soldier, should aspire to be like a Spartan.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Héros de Marathon (The Heroes of Marathon) by Georges Rochegrosse

Greek troops rushing forward at the Battle of Marathon 490 BC

#battle of marathon#athens#plataea#art#georges rochegrosse#history#athenians#achaemenid empire#persian#invasion#antiquity#ancient greece#greece#ancient greek#ancient#greek#europe#european#heroes#troops#soldiers#battle#war#marathon#art nouveau

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

″Food and the Philosophy of Empire: Herodotus 9.82

After the Battle of Plataea, Herodotus relates an anecdote about Pausanias’ reaction to Persian wealth. When he comes across Xerxes’ tent, he has the Persian slaves prepare a typical meal of the Persian elite. He then has his own slaves prepare a traditional Spartan meal. Pausanias is amused at the difference and calls the Greeks together, saying “my purpose in asking you all here is to show you how stupid the Persian king is. Look at the way he lives and then consider that he invaded our country to rob us of our meager portions!” (9.82). Scholarly response to this scene has been two-fold. First, Herodotus has Pausanias set up a display that proves one of the main themes of the Histories: that soft countries should not attack hard ones (Bowie 2003, Vasunia 2009). Second, the scene, along with Pausanias’ laughter, serves to foreshadow Pausanias’ eventual Medizing (Fornara 1971; Lateiner 1989). I propose that Herodotus includes this scene in order to highlight cultural difference and to show that Pausanias takes the wrong lesson from the Persian meal. His misinterpretation foreshadows not only his own downfall, but also problems in how Sparta exercises power.

Herodotus creates a strong association between food and power in his presentation of the Persians (Munson 2001). When Croesus wants to attack the Persians, his advisor Sandanis warns him against it because the Persians’ “food consists of what they can get, not what they want” (1.71). If Croesus wins, he will gain nothing from it; but if he loses, he will lose everything. His statement is somewhat undercut, however, by his description of how Cyrus incites his Persians to rebel against the Medes, their first step towards empire. As an object lesson on conquest, he sets up two days, one of hard work clearing land and one of feasting, and then goes on to explicitly connect slavery with working the land and freedom with conquest and eating good food (1.127). This connection is reinforced by Cyrus’ advice at the end of the Histories: “it is impossible for one and the same country to produce remarkable crops and good fighting men” (9.122). The Persians associate luxury with conquest.

The relationship between Spartan food and power is not emphasized in the Histories, although he does mention the communal mess as one of Lycurgus’ innovations on the Spartan constitution (1.65). Our picture of Spartan meals comes from later sources. Xenophon plays on the comparative meal scene in Herodotus at the beginning of the Cyropaedia, where he compares Persian and Median meals. Plutarch describes the simple Spartan meal in detail in his Life of Lycurgus. Spartan food is simple and signature. They avoid outside influences in their lives and in their food (Hodkinson 2000). The Spartans associate simplicity with power.

The comparison of the meals after Plataea is paradigmatic for the misunderstanding between the two cultures. Herodotus tells us that the Persians enjoy large meals with many courses—this is analogous to enjoying their large empire with many different subject states. The Persians attack so that they can continue to have big meals. It is not a matter of amassing wealth, but rather maintaining a military society instead of having to shift into an agrarian one (a practice analogous to the Spartan practice of keeping their helots). The Persians will use and enjoy their wealth and they are warlike; their culture values warfare as a means and luxury as the goal. The Spartans value the military life for itself, and put limits on the trapping of wealth in all aspects of their lives. The Persians seek to strengthen their center by bringing more in; the Spartans strengthen their center by protecting it from influence. We can see this in how Sparta interacts with other city states and exerts its hegemonic power. Thus, the meals are emblematic of two kinds of power, rather than an ironic comparison of apparent strength.”

Sydney Roy Food and the Philosophy of Empire: Herodotus 9.82 (abstract)

Source; https://camws.org/meeting/2013/files/abstracts/134.Food%20and%20the%20Philosophy%20of%20Empire.pdf

Sydnor Roy, Ph.D. in Classical Studies, UNC-Chapel Hill, is Assistant Professor at the Texas Tech University, Classical and Modern Languages and Literatures

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the things I tried to subtly place into ch10 of theogony, but probably could have done a much better job at, is James’s post-battle trauma—something that we saw pretty acutely in ch8. this chapter is so internal for him and (at least this is how I hoped it would come across) so entrenched in his mental struggles after returning from Plataea. I don’t mean to explain or rationalize my choices here regarding the various things he did throughout the chapter (some of which I'm sure people weren’t happy with! understandably), because that to me would undermine the writing itself, but it’s just one of those things where writing/publishing a standalone chapter can sometimes feel like a self-defeating project.

as in, I’d love to tell everyone to reread at least the last four chapters before this one to catch details and easter eggs and through-lines, but to do so would be anathema to the format of fic writing which we’ve all more or less subscribed to, lol

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay so after a mental health break I am back to finish the 300 movie and as soon as I get to where I had left off:

leonidas just removed xerxes' face piercings that's so rude

oop stelios is down but he's not dead yet.

awe him and leonidas are holding hands how cute

why is leonidas talking about his wife at this hour like okay this is a writting critique: they haven't established their relationship in some meaningful way so I literally don't care about him and his wife. it's not the tragic heartbreaking moment they're trying to make it out to be.

oh so we're at the battle of plataea now at the end and aristodemus, no sorry, Dilios, is somehow commanding a huge army? ookay. the irl guy was disgraced and thougth a coward and while he did fight at that battle, he fought extremely recklessly and obviously wishing to die and was most certainly not any sort of commander/general/whatever he is in the movie.

"we rescue a world from mysticism and tyranny and usher a future brighter than anything we can imagine" WHAT LOL the writting is cringe nonsense until the very end I see

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Victor of Plataea

Anthologia Palatina 6.197 = Simonides

After I, as commander of the Hellenes,

Destroyed the army of the Medes, I, Pausanias,

Dedicated this monument to Phoebus.

Ἑλλάνων ἀρχαγὸς ἐπεὶ στρατὸν ὤλεσα Μήδων

Παυσανίας Φοίβῳ μνᾶμ᾽ ἀνέθηκα τόδε.

Scene of the Battle of Plataea (illustration from the book The story of the greatest nations, from the dawn of history to the twentieth century), John Steeple Davis, 1900

#classics#tagamemnon#Greek#Greek language#Ancient Greek#Ancient Greek language#translation#Greek translation#Ancient Greek translation#poem#poetry#poetry in translation#epigram#couplet#elegiac couplets#Simonides#Ancient Greece#Classical Greece#Greek history#Ancient Greek history#ancient history#Persian Wars#Greco-Persian Wars#Battle of Plataea#Anthologia Palatina#Palatine Anthology#Anthologia Graeca#Greek Anthology#dedicatory epigram#Greek religion

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay thanks to movies and series many foreigners are aware of the Trojan and the Thermopylae war (with the 300 Spartnas). But i believe not many know other important battles that happened during ancient Greece.

Which ones do you think are also worth mentioning?

Just some clarifications for interested people who might not know:

While the Trojan War (sometime in c. 1299 BCE - c. 1100) did happen, we have no idea how accurate any realistic event in the Iliad is. The only thing we know is that the consequences of the war were terrible for both sides. The aftermath is believed to have led to a period of deep regression even in victorious Greece, which is known as the Dark Ages.

The Battle of Thermopylae (not war) (480 BC) is a very real battle, part of the ongoing Persian Wars, meaning the attempts of the Persian Empire to conquer the Greek city-states. While the battle was a defeat stained by treason, the conscious sacrifice of the tiny Greek army caused an uprise of pride and resistance from the Greek people, who up to that point were torn as to whether they should fight or not risk opposing to the massive empire. This is why this battle is considered so important.

So some other turning points in Ancient Greek war history were:

The Battle of Marathon (490 BC). First victory of the Greeks against the Persian King Darius I, despite his much larger forces. The Athenian general was Miltiades. Darius wouldn't return but his son Xerxes attempted to materialize his father's dream 10 years later. Western scholars deem this one of the most significant battles in world history.

Naval battle of Salamís (480 BC), Battle of Mycale (479 BC) and the Battle of Plataea (479 BC). Greek victories. In the Battle of Plataea, the Greeks finally manage to create a big army (for Greek standards). This was the final battle that ended the Persian ambitions over Greek territory once and for all.

Many important battles took place during the Peloponnesian War (431 - 404 BCE) but since this was just something that we nowadays would call a hell of a civil war, I don't think it matters a lot to analyze it here. Just imagine literally everyone fighting literally everyone.

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC). While this is a battle belonging to the great sphere of the violent infighting started and perpetuated after the Peloponnesian War, I'm gonna mention this one because it did change history forever. King Philip II of Macedon alongside the Epirotes, Thessalians, Aetolians, Phoceans and Locrians defeat the usual elites of the Athenians, Thebans, Corinthians, Achaeans, the Chalcidians of Euboea and the Epidaurians. This begins the Macedonian hegemony over Greece, that will lead towards the dissolution of the Greek city-states, the disempowerment of mighty Athens and Sparta, but also the rise of the Macedonian Empire and a more unified sense of Greek identity, in the grand scheme of things.

We talking great battles, right? Not just “side of the angels”... Greeks have given historically significant battles where they were on the offensive, too.

Battle of Issus (333 BC). The Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great defeats the Persian Empire and acquires Asia Minor.

Battle of Gaugamela (331 BC). Under Alexander, Greeks take full control of the Persian Empire.

Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC). Alexander marches against what is modern-day Pakistan and reaches the outskirts of India.

And we should mention the history-changing defeats:

Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC). The Greek King Pyrrhus of Epirus was asked by the Greeks of South Italy to help them against the rising and expanding Roman Republic. Pyrrhus indeed gave great and demanding fights on their behalf, nearly all of them victories, however these victories were so costly that in the end they turned against the exhausted Greek populations. His victories were soon overturned by the Romans, making famous the phrase “Pyrric victory”, which roughly means “winning the battle and losing the war”.

Battle of Pydna (168 BC). After an initial Greek advantage, Romans eventually defeat the Macedonians and take control of the northern Greek lands.

Battle of Corinth (146 BC). Romans utterly destroy the city of Corinth in the Greek South and assume power over the entirety of Greece, which becomes part of the Roman Empire.

War of Actium (32-30 BC). Long story short, the Romans acquire more and more of the lands once taken by the Greeks. The Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt has been going through civil wars, harbored by the Romans. In the War of Actium taking place in Greece and Egypt, Cleopatra and her Roman ally Mark Anthony are defeated by the Roman Emperor Octavian. This is a defeat of the Egyptian people but also the last nail in the coffin of Greek hegemony in the ancient world.

22 notes

·

View notes