#Simon Stephens

Text

emiliomadrid: Andrew Scott in Vanya on the West End. Directed by @samyates2020 and adapted by @simonwstephens. Now the winner of the Olivier Award for Best Revival of a Play.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

32 minute-long single take of andrew scott delivering one of the most breathtaking and engaging performances ever, where it's literally just him walking around a room rambling and moving his hands. i could look at him and listen to him forever. please watch this it left me with an gaping empty pit in my stomach and im so grateful

#he is the greatest ever he is my favourite ever i dont even know what to say or what to do with myself fucking help meeee#this was so so so so so so beautiful holy fucking shit. the fucking script. amazing. phenomenal. im actually so sick guys#andrew scott#simon stephens#film#archive#ultimate fave#Youtube

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

'On a recent winter day in New York when the sun was shining, Andrew Scott rushed into a coffee shop between recording sessions for an upcoming series.

“I’m scheduled tighter than a teenage pop star,” he said, beaming.

The interview had been postponed once, and the location was switched at the last minute to save Scott some time in traffic. But he sat down fully engaged and eager to start talking. Immediately, though, a passerby tapped on the storefront glass and asked for a photo. Scott, without a grumble, sprinted out to oblige, even though the gesture seemed more like a command (“You’re under arrest,” joked Scott) than a polite request.

Scott, the 47-year-old Irish actor, is in demand like never before. That’s partly due to accrued good will. A regular presence on stage in the West End, Scott is known to many as the “Hot Priest” of “Fleabag” or the cunning Moriarty of “Sherlock.” Soon, he’ll play Tom Ripley in the Netflix series “Ripley,” adapted from the Patricia Highsmith novel.

But the real reason Scott’s time is short right now is Andrew Haigh’s new film, “All of Us Strangers.” In it, Scott plays a screenwriter working on a script about his childhood. The film is gently poised in a metaphysical realm; when Adam (Scott) returns to his childhood home, he finds his parents (Claire Foy, Jamie Bell) as they were before they died many years earlier.

At the same time, the movie, loosely adapted from Taichi Yamada’s 1987 book “Strangers,” balances a budding romance with a neighbor ( Paul Mescal ), a relationship that unfolds with profound reverberations of family, intimacy and queer life. In a dreamy, longing ghost story, Scott is its aching, shimmering soul.

“The challenge of it was to try to go to that place but not gild the lily too much,” Scott says. “As an actor, I have to be in touch with that playful side of myself and that part of you that’s childish. I was actually quite struck by how vulnerable I looked in the film.”

Scott’s acutely tender performance has made him a contender for the Academy Awards. He was named best actor by the National Society of Film Critics. At the Golden Globes on Sunday (Scott wore a white tux and t-shirt), he was nominated for best actor in a drama.

Scott has long admired actors like Anthony Hopkins, Judi Dench and Meryl Streep — performers with a sense of humor who, he says, “are able to understand what you feel and what you present.” Scott, too, is often funny on screen (see Lena Dunham’s medieval romp “Catherine Called Birdy” ). And even in quiet moments, he seems to be buzzing inside at some discreet frequency. Something is always going on under the surface.

He’s been acting since he was young; drama classes were initially a way to get over shyness. Scott’s first film role came at age 17. He has often spoken about seeking to maintain a childlike perspective in acting. In that way, “All of Us Strangers” is particularly fitting. On Adam’s trips home, he sort of morphs back into the child he was. In one scene, he wears his old pajamas and crawls into bed with his parents.

“So many of the things that are required of you as an actor are a sense of humor and some ability to be able to put yourself in a situation. Because it’s all down to imagination,” says Scott. “For me, that’s the thing you need to keep. That’s the thing — because I started out when I was young — I don’t want to move too far away from. Like when kids go, ‘OK, you be this and I’ll be this.’ That ability doesn’t leave us. What does leave us is a lack of self-consciousness. Our job is to hold on to that.”

Haigh, the British filmmaker of “45 Years” and “Weekend,” began thinking of Scott for the role early on. They met and talked through the script for a few hours.

“He’s a similar generation to me. He’s a tiny bit younger than me, but he’s from the same generation,” says Haigh. “He understands that experience.”

Scott came out publicly in 2013, but his natural inclination is to be private. “I feel like I’ve given so much of myself in the film, you think you don’t want to give it all away,” he says. He describes “All of Us Strangers” — which Haigh shot partly in his childhood home — as personal, but not autobiographical in its depiction of the alienation that can linger after coming out.

“Mercifully, I feel very comfortable for the most part. But it stays with you that pain, and it actually makes you more compassionate, I think. Because we shot in Andrew’s childhood home, that sort of threw down the gauntlet in relation to how much of his own personality he was giving,” says Scott. “I wanted it to be sort of unadorned, unarmored and raw. That’s why I think there’s such tenderness in the film.”

Scott has sometimes recoiled from how sexuality is talked about the media and in Hollywood. He recently said the phrase “openly gay” should be done away with. As of late December, Scott hadn’t yet watched “All of Us Strangers” with his parents, though he planned to.

“The best way to express it is to say I’ll be very sensitive to how they watch it and how they feel about it, and how it makes me feel them watching it,” Scott says.

The tenderness in the film is also owed in part to Scott’s chemistry with Mescal. On-screen chemistry is an amorphous quality that the film industry has long tried to turn into a science with camera tests and marketing that flirts with real-life romance.

But for Scott, it’s something different. He and Phoebe Waller-Bridge had chemistry, overwhelmingly, in “Fleabag,” but that didn’t have anything to do with sexual attraction. Pinpointing that quality is something Scott pondered during Simon Stephens and Sam Yates’ recent staging of Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” at the National Theater. Scott played all eight roles, meaning he essentially had to have chemistry with himself.

“Chemistry isn’t just about sexual chemistry. It’s something to do with listening, and I think it’s something to do with playfulness,” Scott says. “Your ability to listen to someone and take note of what someone is doing is chemistry. You have to wait and see what the other actor is doing.”

A few moments later, Scott will have to rush out just as quickly as he arrived. But before that, he leaned back, naturally lit by the winter sun, and pondered whether “All of Us Strangers,” in the nakedness of his performance, had taken him somewhere he hadn’t before been as an actor.

“Yeah, I think so,” said Scott. “Or else to return to something that perhaps I’ve been before.”'

#Andrew Scott#Paul Mescal#Andrew Haigh#All of Us Strangers#Phoebe Waller-Bridge#Fleabag#Ripley#Netflix#Moriarty#Sherlock#Taichi Yamada#Strangers#Patricia Highsmith#Jamie Bell#Claire Foy#Lena Dunham#Catherine Called Birdy#45 Years#Weekend#Simon Stephens#Sam Yates#Vanya#National Theatre

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the curious incident of the dog in the night time#mark haddon#simon stephens#theater#theatre#plays#tumblr polls

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone please get this for us!!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright, almost a week later, here is my review of Vanya and the night I saw it. Autocorrect didn't let me type this on my phone in my grimy bunk bed and that cold got me good, but here are my thoughts! @itsathingialwayssay , @shegottosayit , @illfayted17 this might interest you. Be aware, there are spoilers for the play as well as the production behind the read more.

I saw the play on Monday September 25th, so my opinions are based on that evening, can’t say anything about other nights!

I’ll start with some negatives:

The theatre. Not so much the interior or the personnel, who are absolutely lovely, but why oh why did I have to hear the trains throughout the whole performance?! At first, I thought it was on purpose, with it being the Russian country side, so you might hear some trains here and there, but no, it’s Charing Cross that you hear. Also it’s freaking expensive, but we knew that.

Secondly, I was annoyed by the audience. It was a surprisingly large number of classic elderly theatre goers, who all seemed to enjoy themselves a lot (except for one guy who snored), some teenagers dragged there by their parents (or the promise of seeing Moriarty) and some assholes, like the ladies next to me. One came in after the first act, prosecco in hand, they whispered to each other during weird moments and generally seemed bored and/or disappointed. Which is their prerogative, you don’t have to like everything I do, but with these two it seemed… performative.

Also, about the standing ovations: I get Andrew’s critique, it’s dumb if you feel like you MUST do it, but the fact is, that in a theatre that small, you don’t get to see the person bowing, if you don’t stand up. So yeah, people stood up, I did too (because unlike in Austria where you clap for like 5 minutes if you DIDN’T like it and for like 30 if you did, in the UK they only come out to take a bow once or twice and I wanted to see him), but these two ladies just left with sourpuss faces.

Thirdly the cigarettes. I knew he was going to smoke on stage, what I wasn’t prepared for was them smelling this bad. They’re not normal cigarettes, they’re of the self-rolled, cheap student tobacco kind, that you only really use for blunts. They reeked. If you’re in the first few rows, I’m sorry.

Fourthly, I don’t know if the play really lent itself to a one man show. Don’t get me wrong, I loved what Simon did with it, the way he mostly cut out the love rivalry between Vanya and the doctor, and shifted the focus more on Helena was a great decision. It made the play more cohesive and boiled it down to its message quicker. Loved the modern language and the Britishisms (could have dealt without the name changes, no one is called Vanya in a play named Vanya) and it was truly laugh out loud funny at times, which is great, because I’m depressed enough without listening to depressed Russian people for a full show.

But still, while it all worked in the end, I think there are plays better suited for this treatment. I have spoken to shegottosayit about this, but I also think they kinda expected a familiarity with the play, because it helps you following the plot. I talked to two girls in the queue outside though and they weren’t familiar with the play and understood it well, so what do I know.

Which brings me to the great stuff. The whole thing starts with Andrew just wandering on stage, smiling into the audience, switching off our lights and turning them on on stage. As if to communicate, ok, we’re in the theatre, you’re here to watch a play, I am an actor doing that play, like we’re all in on a joke. He starts with the different characters and they all have an identifier. For example, Vanya has his sunglasses, Helena her chain, Sonya her dishrag and it’s all nice, haha, see the actor is using props, so you know who is who, it’s simple and harmless. That’s how he gets you. Because he doesn’t need them and over the course of the play he starts playing and fucking with them and it’s SO GOOD!

He doesn’t change his voice much between characters, except the two “funny” ones (and maybe Alexander), there he goes a bit into more comical registers, but for the main characters he pretty much uses the same voice. And you still can tell them apart! Because he changes posture, his body language, yes, his tone, but not his voice and the levels of masculinity and femininity (in a traditional sense), yet he never veers into camp or offensive (that aspect really fed into my unpopular opinion on the whole “straight actors in gay roles” discourse, which I will never talk about). It’s incredible to watch how fast and seamlessly he does that and how effortless too. That’s the craziest thing about watching him act, he makes it seem easy, as if it’s nothing to him.

And the faces. The theatre has opera binoculars you can rent for one pound, I forgot my glasses (mild myopia, objects further away get blurry after a long day, especially if they’re an actor I’m watching from the second to last row), so I was super glad to have them and look at his face close up. What did I see? He changes faces. I’ve seen him do it before, but in this it’s instantly and so quickly! I’m not gonna lie, it’s a bit creepy how he can change his facial shape somehow and go from sweet Sonya to hardened Ivan Vanya. It’s not just countenance or expressions, it’s something else and wow is it impressive! But a bit scary too once you think about it. ^^’

Also “zooming in” on him really cleared up something I’ve been wondering about ever since I’ve seen King Lear: One of Andrew’s biggest shortcomings on film can be that he sometimes comes across as too much, as a bit over the top. It is a theatre actor thing and he’s not the only one doing it (especially not in King Lear) and yes, that completely disappears live on stage. He acts for the whole house, but it always feels natural.

The one thing that felt a little bit forced was the singing in the end, he's right, he’s not a good singer (sorry!) and it took me out a little bit. The ending of Vanya is beautiful and heartfelt, I get what they wanted to achieve with him singing “If you go away”, it was a pause, a mood setter, but I think there are better ways to do this than through a musical interlude. That said, I saw A Little Life the other night, which is by the same production company, they made poor James Norton sing too and compared to him Andrew sings like an angel. So maybe I’m just a massive snob (hint: I am).

The other things that took me out a little were the sex scenes. Yeah, sex scenes in a one man play where the original play has none (at least not explicitly so). Damn, it’s been almost a week and my mind is still reeling from them. Did I like them? I have no fucking clue! I seriously need to talk to someone who didn’t have Andrew star in all her lonely sexy fantasies for the past 4 years, because I need to know how they affected someone with a normal, working brain who is not me.

I was torn between “wtf is going on” “JESUS HE TOOK HIS SHIRT OFF” “…you’re watching a dude make out with himself…” “…the sounds…” “don’t look at his naked back while he’s humping the stage, that’s rude, OH GOD YES LOOK AT HIS NAKED BACK, LOOK AT IT MOVE”.

The second scene was even worse, because he’s standing up against a door, entangles his fucking impressive arms and moans as the lady while you see him move as the guy. Which was, yes, hotconfusingweird too, but I could have dealt with it, if he hadn’t mimed the penetration literally two seconds before and my brain just short-circuited and disappeared downstairs.

The third confusingly hot thing happens in the end, when the doctor says his goodbyes. It’s actually a very good and touching scene, it has been set up that he’s falling into alcoholism and now that all his endeavours are nil, he downs more than half a bottle of vodka. We’ve all seen Andrew chug that beer in The Town and he does it here as well, but it takes a while and it’s so quiet in the theatre that you can hear him swallow and cry all the way through. Yeah. Yeah, I know.

Seriously though, there are more than one moment when the whole theatre is just stock-still. I mean, people laughed and reacted, again, one guy snored, I sighed a lot at Sonya (#ohlookitme), but in the important moments the theatre was dead quiet. Except for Charing Cross, of course.

When I left the theatre, my brain was buzzing and I walked out right into the backstage area. I read “backstage to the right” and was ready to walk to the right, even though no one was there. Except that stupid me HAD to ask the security, who I recognised from pics and the Cyrano backstage, if that was the way to the signings. And no, it wasn’t, that’s literally in front of the theatre (and honestly, probably why there are no selfies allowed this time, if they were, people would block that busy street for hours), I was walking towards the actual stage door. If I had had just one ounce of more self-confidence, I just could have kept on walking into the dressing rooms, God damnit!! (I’m kidding, I would never do that, and it would most likely get me banned for life, but still, it was a funny situation and that security was actually really nice and cool).

As for the signing, it’s a straight-forward affair, you line up, you move forwards, he signs your stuff, you move on (except if you’re an old lady, but more of that later). I soaked him in in all my manic brain overloaded happiness while waiting for my turn though, and the first thing I noticed was that he isn’t as short as people pretend he is. Yes, he wore some trainers with a thicker sole, but with them he wasn’t that much shorter than I am. Perfect height, for eye-contact, just saying.

Second thing was that he’s in the shape of his life, dear Lord! I always read him as wiry, which can look buff on screen, but no, he’s genuinely, proper buff. Those are some serious arms and just generally he’s wider than I would have expected. Other than that, he looks pretty much exactly like he does on screen. Some actors don’t, they’re either plainer or prettier (Anne-Marie Duff, she really was fucked over by some cruel form of unphotogenicness) in fact, the second night I went there I saw Sam Yates (he shook my hand :D) and he does not look like he does in pics for example. Andrew does. He has a fascinating and alive face and looks just like he did in that Vanity Fair video, except without the orange goo.

The first night I saw Simon Stephens coming out the stage door too and I literally hopped over to him, beaming like a loon. He and the people he was with were SO nice and so helpful, he signed my version of Vanya (the German edition) and I could actually voice my thoughts (which I couldn’t with Andrew) and tell him how much his interviews have helped me through the lockdowns and how I admire his writing, bla bla bla.

Anyway, I made him laugh, he shook my hand and said “it was a pleasure meeting you [widge’s real name]” in which moment my jaw literally did that looney tunes thing and dropped to my chest. Night was MADE, you don’t understand how much!

[Here I cut out a large chunk of extra thoughts to allow myself to post this in the tags]

Anyway, back to the old lady, she was the one who made Andrew laugh during the signing (LOVE that laugh), I passed her on the way back to the train and had to talk to her. She was a proper lady, dressed elegantly and she was the first damn person outside the theatre who understood my need to DISCUSS the play! Everyone else in the line was talking about other things, I had to PROCESS what had happened. She and her assistant were so cool, and she said she’d absolutely loved it and had a ton of other well thought through opinions on it. Big fan of her, no idea what her name is, but we all should get some cool older ladies to talk about theatre with, when our brains are buzzing with so many new impressions!

I aimlessly wandered on over the Thames after that, sat down in some red paint on the way, which made my jeans look interesting for the rest of the trip and had to just move for a while to cool down. I did go to the queue the next day too, just to be a little less tongue tied around Andrew (it did not work, whatsoever xD), but that was the day Joe Alwyn and a fox made an appearance, so it was totally worth it. As was the whole international camaraderie in the queue. Honestly, I’ve missed that, just people being excited about something together, I got hugged by a tiny Indian (?) girl and a Russian lady, all because we’re a bunch of excited nerds outside of theatre. It felt fucking great.

19 notes

·

View notes

Video

Happy Pi day, Sturridge babies.

(Also, if you know pi up to two-four digits after the decimal point, you’re good to do math with it for life. Anyone who knows more than that is just trying to show off lol)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrew Scott Flies Solo Brilliantly in his One-Man "Vanya" in London's West End

#frontmezzjunkies reviews

#Vanya

after #AntonChekhov

performed by co-creator #AndrewScott

adapted by co-creator #SimonStephens

directed by co-creator #SamYates &

designed by co-creator #RosannaVize

at the @DukeofYorksLDN #WestEnd #London

@vanyaonstage

Andrew Scott in West End’s Vanya, Photo by Marc Brenner.

The London Theatre Review: West End’s One-Man Vanya

By Ross

A quiet flies fast over the excited crowds in the Duke of York’s Theatre in the West End of London, as Andrew Scott (Veracity Digital’s Sea Wall the Film) saunters out, flicking the house lights off with a devilish grin. He’s playing with us, knowing just how thrilled we all are…

View On WordPress

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyone who has watched / Listened to a Sea Wall /A Life by Simon Stephens and who'd be able to explain what Alex said to Arthur and why it was the cruellest thing? I've been trying to figure it out but I don't get it

And then it cuts, tells how Alex and Helen get back to their empty appartment, and the play ends on

Probably has something to do with the existence of god they had been discussing? But not too sure ...

So yea if you have any interpretation

#btw if you like the way tom Sturridge narrates things and his voice I can hoghly recommend the audible version#the emotions in his voice are brilliant#i didn't get much tbh but i truly truly enjoyed the ride#a sea wall / a life#simon stephens#tom sturridge

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teatro: Estreia do espetáculo Wastwater no Teatro Pequeno Ato

Teatro: Estreia do espetáculo Wastwater no Teatro Pequeno Ato

Espetáculo traz três casais que se encontram diante de uma escolha definitiva sobre seus futuros.

Wastwater, espetáculo do autor inglês Simon Stephens, ganhou os palcos em 2011, em Londres, e obteve boa crítica. Agora, a peça estreia no Brasil, com direção de Fernando Vilela, em temporada de 11 de junho a 8 de julho, no Teatro Pequeno Ato, na Vila Buarque, em São Paulo.

O elenco é formado…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

A bunch of sketch requests from Instagram! I'm loving drawing these and seeing them together so I'll probably do more

#oh boy the tags...#scott pilgrim#roxie richter#gideon graves#matthew patel#wallace wells#mr peanutbutter#ice king#jake the dog#stephen stills#ramona flowers#betty grof#simon petrikov#brett hand#and tiny julie diane and daria

704 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before the frenzy of Ripley promo takes over, I wanted to highlight Andrew's beautifully moving acceptance speech and tribute to his mother (who died very recently, March 7th) from the Critics Circle Theater Awards and his Best Actor win for VANYA.

Apologies for any mistakes in the captions (and to the stage crew for not catching their names) I did what I could with the audio and the limitations of the free editing software I was using.

Thanks to Cindy Marcolina for the original video source.

#andrew scott#vanya#the whole vanya crew#simon stephens#sam yates#wessex grove#fight for the arts#my heart 🥺#sending love ❤️

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to acknowledge something. And it’s embarrassing because I know it’s something that you will have noticed. There’s a hole running through the centre of my stomach. You must have all felt a bit awkward because you can probably see it. Even in this light. Mostly people choose not to talk about it. Some people tell me that they’re sorry but that, yes, they can see my hole. “‘What’s that, Alex?’ they say. ‘You appear to have a great big hole running right through the middle of you.’

[...]

I’m holding my entire head together. The skin and the shell of me. I’m falling absolutely inside myself. But you can see that. You can see the — in my —

— Sea Wall, a monologue by Simon Stephens [film version.]

#guys this has completely rocked me to my core im actually in shock#i cant breathe properly this is just hit after hit i feel like i've been bombed#what do i tag this as.#simon stephens#writing#quotes#sea wall#im also tagging it#andrew scott#because its him its just him it was written for him debuted by him and he changed my world yet again cos he loves doing that. fuck my life#hole tag

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Fleabag’s hot priest is about to take on his most liberating role yet: a one-man show of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya in which he will play all nine roles, male and female. He loves taking risks, he says. It seems to be paying off…

I last saw Andrew Scott in the flesh eight years ago. I was sitting in the gloom at the top of what used to be St Martin’s School of Art in the Charing Cross Road – a tiny, temporary theatre had sprung up there – and he was three feet away from me, surrounded by great piles of stuff: newspapers, books, chairs, cupboards… a piano. The occasion was Richard Greenberg’s play The Dazzle, about two compulsive hoarders, the Collyer brothers, and his performance as one of them was mesmerising: in truth, almost too mesmerising. My mind went into overdrive. All that paper and mahogany. What if something toppled, and he was crushed – as the real Langley Collyer was – beneath a chest of drawers?

He wasn’t crushed, of course. But what’s striking and slightly odd is that today I’m seeing Scott in the flesh for the second time, and we’re again at the top of an old building – in this case, a public library – in rooms that feel a bit dilapidated, if not exactly derelict. People imagine the actor’s life to be a glamorous one, particularly if the actor in question has been in a Bond film – and of course it has its enchantments. But then there are the hours spent in spaces like this: long days of sandwiches, bottled water and elusive lines. When we came up in the ancient lift together, I couldn’t decide which of us was the more anxious. He was, I would guess. “MY TWELVE HOURS TRAPPED WITH FLEABAG STAR” ran the ticker tape in my mind as the mechanism creaked and groaned, and we each did our best not to meet the other’s eye.

Scott has spent the past three weeks here, deep in rehearsals for Vanya, a new version by Simon Stephens of Anton Chekhov’s great tragicomedy Uncle Vanya. But there’s new, and then there is… new. This adaptation gives the play, among other things, a contemporary setting. However, when the production opens in the West End, its chief novelty – and its chief draw, given Scott’s huge following – will be the fact that it is a one-man show. He will be playing all nine parts: male and female, young and old, beautiful and not-so-beautiful. It must be hard to learn so many lines, I say, once he’s (semi) comfortable on a battered leather sofa, his old, white T-shirt giving him a slight look of Marlon Brando. Doesn’t he feel like he’s going mad, with all these voices in his head? He laughs – a high-pitched, wicked laugh. “Yeah. I do, and it’s really hard [to learn]. Usually, when you can’t remember a line, another actor will say, ‘What time is it?’ or something, and then it comes to you. But now I’ve no one to cue me.” Alone on stage, he has had to change his mindset completely: “I’ve come to understand that I’m sort of looking after all these characters.”

The idea for a one-man production came about by accident. Scott, Stephens, and Sam Yates, who is directing the play, were workshopping it together (Scott has worked with Stephens twice before, most notably in Birdland at the Royal Court, in which he played a rock star who has made a Faustian pact with fame). “We miscalculated the parts, and I ended up having to act with myself, and it was kind of interesting. It gave birth to the idea that, as much as these characters say they’re different from each other, actually, some of them are very similar. I’m more interested now in those similarities than in, you know, doing a funny voice [for each one]. The production seems to me to be about what the act of creation is. I love the idea that you might be able to represent what a writer experiences on stage, all these characters in his head.”

But how on earth will the audience work out what’s going on? I understand about the funny voices, but won’t Scott have to change his a little bit when he’s acting the part of a woman? He smiles, teasingly. “I don’t think I should tell you that… But you don’t need to worry too much. I feel so liberated! I hope people will start to look at what’s within the performer so that something happens that can only really take place in a theatre – which is that you’re seeing one thing, but imagining something else.” This sounds like reading a novel, visualising scenes and characters for yourself, filling the gaps between words. He nods. “Look, I definitely don’t want to shy away from the ridiculousness of this project, and yeah, I’m nervous, but I’m loving the process. I think it’s a really sexy play. You know, Chekhov was a doctor, and he saw death so much, and I think he was able to understand human beings like no other writer.”

The argument that actors should only play who they are – that a gay character, for instance, may be played only by a gay actor – is made more and more often lately. But this production seems (to me, at least) subtly to resist the notion of identity politics in the theatre; to suggest that such rigidity may sometimes be a cul-de-sac. “It can be a cul-de-sac, certainly,” Scott says. “Of course those arguments have to be heard. The world isn’t a level playing field. But I think transformation is as important as representation. Our first understanding of storytelling happens when we’re young. Our mother or father is pretending to be a wolf. We know we’re safe, but we’re scared, too. Our parent can be a wolf! Human beings can create worlds within themselves. I don’t think we can just slice that out of ourselves.”

He knows some will heartily dislike this Vanya, but the thought seems, if anything, to excite him. “It could go wrong,” he says. “But we need a bit more of people not liking things.” He’s ambivalent, to put it mildly, about standing ovations, which seem to happen in the theatre most evenings nowadays. “My concern is that everything becomes meaningless. I think it’s unfortunate that if someone decides not to stand up, it’s perceived that they hated it. That’s not necessarily true. Maybe I thought it was very good, but I didn’t feel like rising to my feet. My producers are going to hate me for saying this, but I strongly believe that if people don’t feel like standing up, they shouldn’t. People feel lonely, having to stand when they don’t want to. Equally, it’s kind of moving when most people are not standing up, and three people are.”

Does he blame the internet for this? Is it just another form of “liking” something? “I do blame the internet, yes.” But perhaps, too, it has to do with cost. “I was recently on Broadway, and tickets there are astronomically expensive, and I thought: well, these people have to stand up because they’ve spent $390, so it’s got to have been one of the best nights of their lives.” Either way, he doesn’t understand it: the firmness and immediacy of people’s responses. “When you’ve just seen a play, it’s a really sensitive time. It’s weird when people start talking straight away about their new conservatory.” All this may explain why he feels there is more value for him in doing experimental work. “Some people will like it, some people won’t, and that’s great. I feel ferocious about wanting to take risks.”

In the coming months, Scott will be everywhere: a trick of scheduling, rather than by design. Vanya will be followed in January by the release of All of Us Strangers, a film in which he stars with Paul Mescal and Claire Foy (he plays a depressed screenwriter who goes to visit his childhood home, only to find that his parents, far from having died in a car crash when he was 12, are alive and well – though much of the coverage of the movie so far has focused on the fact that his character and Mescal’s are lovers). “It’s a beautiful film,” he says, dreamily. And then there’s Ripley, a Netflix series (its release is expected at the end of this year), based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr Ripley, written and directed by Steven Zaillian, the screenwriter of Schindler’s List and Hannibal.

“It’s a big, big thing,” he says, of his role as Tom Ripley, grifter and serial killer. And yet, Scott said he wouldn’t be doing any more crazed sociopaths, having played Moriarty in Sherlock (he was also a baddie in the Bond film Spectre). “I know, but what I find interesting about him is not the psycho-ness; it’s the otherness. To me, it’s about what it’s like never to be invited to the party. We all know people who don’t make it easy for themselves, who are maybe a bit strange. But if you’re constantly ignored, or sidelined, or don’t fit in, what happens? Is it that something dark emerges? I don’t mind saying that playing him was challenging. It was very lonely. We filmed during Covid, and the five-day isolation requirements that were in place both here and in Italy meant people couldn’t come and visit, and I couldn’t come home. It’s eight hours of television, and he’s a solitary figure in this version, so I was on my own a lot.”

Scott is 46, though you wouldn’t know it; his enthusiasm, like his fidgetiness, belong to a younger man. He grew up in Dublin, with his two sisters – his father worked at an employment agency; his mother was an art teacher – where he was educated at private Jesuit school, attending drama classes on Saturdays. Art was his first plan – painting is still his great love; he can’t wait for the forthcoming Hockney show at the National Portrait Gallery – and he won a bursary to art school at 17. But then he was cast in a film, Korea, about an Irish boy emigrating to America in the 1950s who’s enlisted to fight in the Korean war, so he turned the place down, and once the movie was done, went to Trinity College to study drama instead. After six months, bored by the course, he left to join Dublin’s Abbey theatre.

He seems hardly ever to have been out of work, and his CV is such a mixture: Gethin the tense gay Welshman in Matthew Warchus’s film Pride; eccentric Lord Merlin in the BBC adaptation of The Pursuit of Love; an acclaimed Hamlet in 2017 at the Almeida theatre. By this point, his mantlepiece – he has two, one in London, and one in Dublin – must be quite frantic with statuettes (his most recent win, in 2020, was a Laurence Olivier award for best actor for his performance as Garry Essendine in Noël Coward’s Present Laughter). Does he feel blessed? “Yes, and that’s a really nice way of putting it. I’m grateful.” But perhaps this sounds too… humble: “I’ve never understood why there’s some sort of shame associated with being an artist. I feel able to call myself one.”

His fame is at a level that means he can move around London unnoticed, and he’d like to keep it that way. “I’m suspicious of it. I’ve no real interest in the value of it. The idea of being followed by a photographer seems hellish to me.” Does it affect his relationships? He doesn’t believe that it does, though there are “creepy, unsavoury people” out there who might not “have my best interests at heart”. Is he single? “Yes, I am.” Would he like to meet someone? He would. Surely it’s easy in his world? So many lovely new people entering his orbit all the time – and with his looks… He laughs. “That’s a lot of projection, there,” he says, sounding suddenly more Irish.

I read somewhere that some women in Ireland will always think of him as the guy who turned up to their demonstrations in the run-up to the abortion referendum in 2018, even when it was raining (the vote overturned the ban on abortion in the country, and followed one of 2015, which allowed same sex couples to marry). Isn’t it amazing how much Ireland has changed? When he was 16, it was still illegal to be gay, as he is. “Yes, it’s immense for people of my generation to have been emancipated from the shame of the Catholic church. But it’s interesting. Privacy matters to me, but then I remember Sinéad O’Connor being on The Late, Late Show, talking about human rights, and how important that was. Her kindness… We’re only just finding out about it. She didn’t announce it to the world. Again, it brings us back to social media. Does kindness happen if you don’t tell everybody about it?”

Scott is no longer a practising Catholic. But he can’t be certain this means he won’t call for the priest at the end (this conversation has taken a morbid turn, and it’s my fault). Perhaps it’s in the marrow. “It’s the organisation that’s the problem, not the principles behind it, which are very beautiful for the most part. I remember when Simon and I were doing [the play] Sea Wall. One of the lines in it is: show me God, where is he? And then the next line is: well, show me love, where is that? You can’t get evidence for either of them really. They’re just strong feelings. I believe in the power of love. I feel it’s stronger than anything, because you can’t do anything about it. I’ve so much of it in my life, and one of the things I’m most proud of is how much I’m able, not only to receive it, but to give it – and if somebody thinks that’s sentimental or mawkish, well, to me it’s the opposite.” He talks for a while in this vein. “I want to try to be a good person; not just a nice person, but a good person,” he says, his voice racing on – and it makes me think of him as the Hot Priest in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag, the role for which he may now be best known. If every pulpit came with an Andrew Scott, our churches would be bulging at the seams.

Soon after this, there’s a knock on the door. It’s time to begin rehearsal (in the hall outside, his director stands at a lectern, looking quite priestly himself). He has, he says, another three weeks to go before Vanya opens, and when it does, he’ll be looking out for me; I’d better be sitting down at the curtain call, he jokes. Well, perhaps I’ll have good reason to be sitting down, I joke back. But he’s ever serious: “I always remember what my mum used to say. She’s an art teacher, and she used to tell us that a good drawer never rubs out. So, you draw a line, and then you get it wrong, and then you start a new line. The fact that people can see your old line doesn’t make them appreciate your new line any less. It may even make them appreciate it more.” What he means, I think, is that he believes it’ll be all right on the night.'

#Andrew Scott#Fleabag#Vanya#Ripley#The Dazzle#Anton Chekhov#Uncle Vanya#Simon Stephens#Sam Yates#Birdland#All of Us Strangers#Paul Mescal#Claire Foy#Jamie Bell#The Talented Mr Ripley#Patricia Highsmith#Steven Zaillian#Moriarty#Sherlock#Spectre#Pride#Lord Merlin#The Pursuit of Love#Hamlet#Almeida Theatre#Noel Coward#Present Laughter#Olivier Awards#Sea Wall#Phoebe Waller-Bridge

18 notes

·

View notes

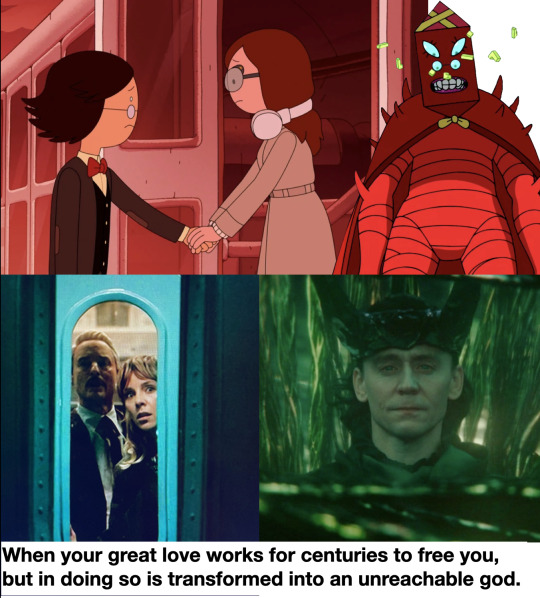

Text

Honourable mention to Strange Supreme, although he failed to save Christine.

#adventure time#fionna and cake#petrigrof#simon petrikov#betty grof#loki series#lokius#sylkie#sylkius#loki#sylvie#mobius#strange supreme#stephen strange#christine palmer#what if series

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, so I just found out that my latest …“crush” Lord Morpheus, Dream of the Endless, Tom Sturridge has pretty recently played Alex / Sea Wall, the role written for and embodied so perfectly by Andrew Scott. I am …shaken? Can this be seen somewhere? Anyone got a link for me? Please, I gotta compare!!

6 notes

·

View notes